Abstract

Research in animal models has demonstrated that electrical stimulation from a cochlear implant (CI) may help prevent degeneration of the cochlear spiral ganglion (SG) neurons after deafness. In cats deafened early in life, effective stimulation of the auditory nerve with complex signals for several months preserved a greater density of SG neurons in the stimulated cochleae as compared to the contralateral deafened ear. However, SG survival was still far from normal even with early intervention with an implant. Thus, pharmacologic agents and neurotrophic factors that might be used in combination with an implant are of great interest. Exogenous administration of GM1 ganglioside significantly reduces SG degeneration in deafened animals studied at 7–8 weeks of age, but after several months of stimulation, GM1-treated animals show only modestly better preservation of SG density compared to age-matched non-treated animals. A significant factor influencing neurotrophic effects in animal models is insertion trauma, which results in significant regional SG degeneration. Thus, an important goal is to further improve human CI electrode designs and insertion techniques to minimize trauma.

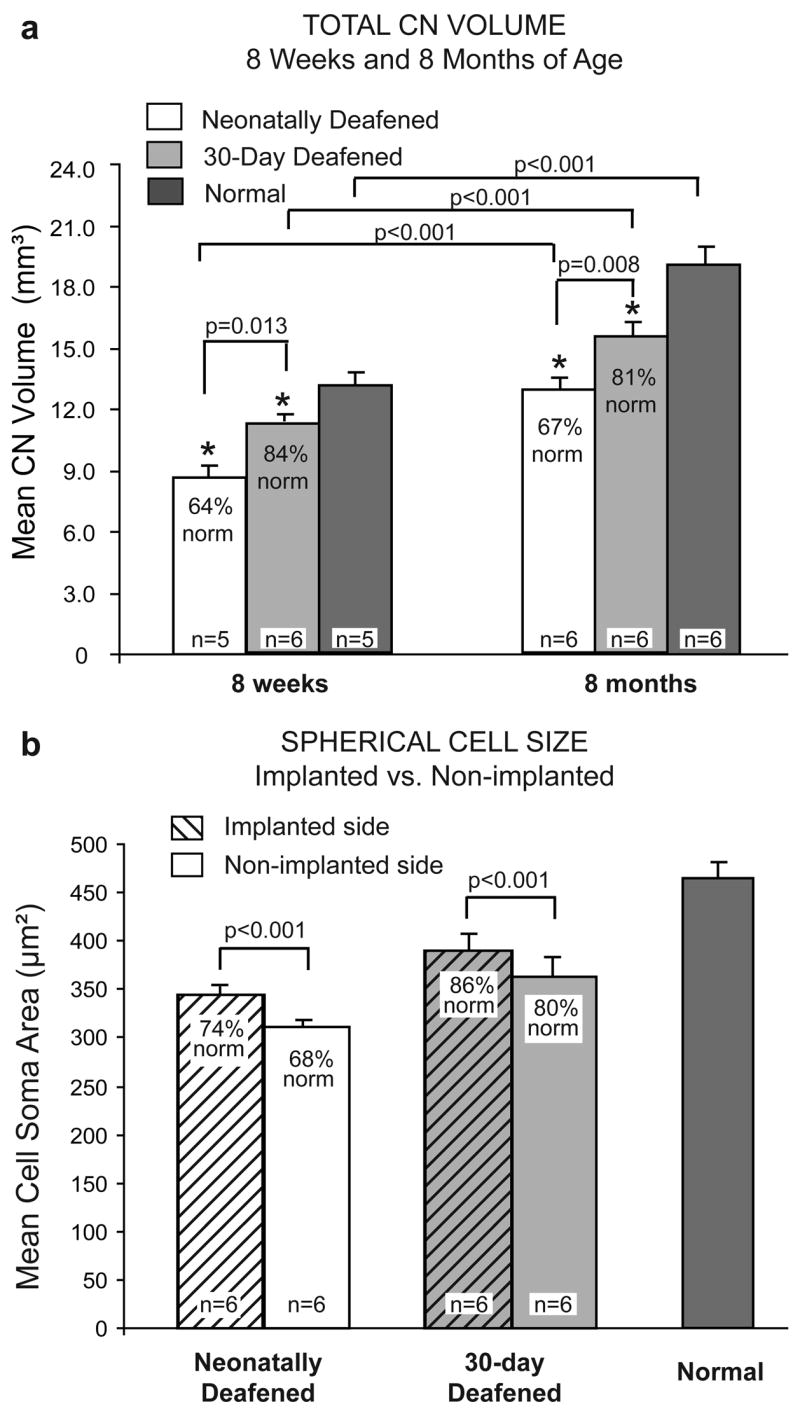

Another important issue for studies of neurotrophic effects in the developing auditory system is the potential role of critical periods. Studies examining animals deafened at 30 days of age (rather than at birth) have explored whether a brief initial period of normal auditory experience affects the vulnerability of the SG or cochlear nucleus (CN) to auditory deprivation. Interestingly, SG survival in animals deafened at 30-days was not significantly different from age-matched neonatally deafened animals, but significant differences were observed in the central auditory system. CN volume was significantly closer to normal in the animals deafened at 30 days as compared to neonatally deafened animals. However, no difference was observed between the stimulated and contralateral CN volumes in either deafened group. Measurements of AVCN spherical cell somata showed that after later onset of deafness in the 30-day deafened group, mean cell size was significantly closer to normal than in the neonatally deafened group. Further, electrical stimulation elicited a significant increase in spherical cell size in the CN ipsilateral to the implant as compared to the contralateral CN in both deafened groups.

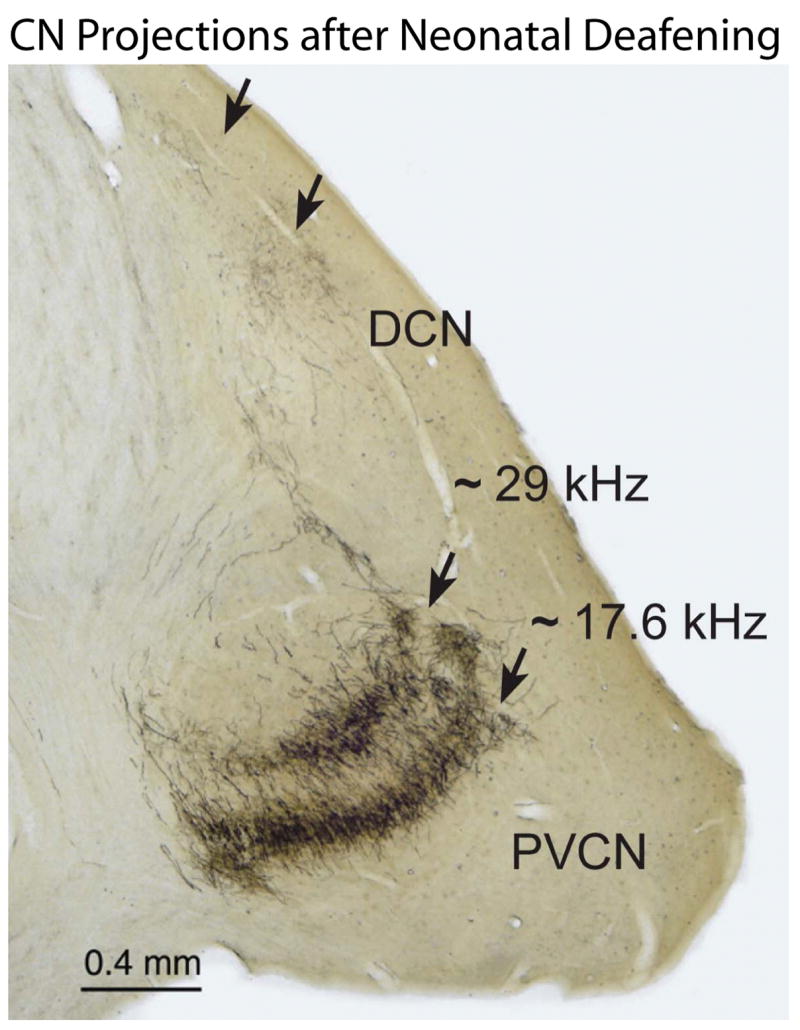

Neuronal tracer studies have examined the primary afferent projections from the SG to the CN in neonatally deafened cats. CN projections exhibit a clear cochleotopic organization despite severe auditory deprivation from birth. However, when normalized for the smaller CN size after deafness, projections were 30–50% broader than normal. After unilateral electrical stimulation there was no difference between projections from the stimulated and non-stimulated ears. These findings suggest that early normal auditory experience may be essential for the normal development (or subsequent maintenance) of the topographic precision of SG-to-CN projections. After early deafness, the CN volume is markedly smaller than normal, and the spatial precision of SG projections that underlie frequency resolution in the central auditory system is reduced. Electrical stimulation over several months did not reduce or exacerbate these degenerative changes. If similar principles pertain in the human auditory system, then findings in animal models suggest that the basic cochleotopic organization of neural projections in the central auditory system is probably intact even in congenitally deaf individuals. However, the reduced spatial resolution of the primary afferent projections in our studies suggests that there may be inherent limitations for CI stimulation in congenitally deaf subjects. Spatial (spectral) selectivity of stimulation delivered on adjacent CI channels may be poorer due to the greater overlap of SG central axons representing nearby frequencies. Such CI users may be more dependent upon temporal features of electrical stimuli, and it may be advantageous to enhance the salience of such cues, for example, by removing some electrodes from the processor “map” to reduce channel interaction.

Keywords: auditory deprivation, auditory nerve, cochlear implant, cochlear nucleus, cochlear spiral ganglion, electrical stimulation, GM1 ganglioside, selegiline, neonatal deafness, primary afferents, neurotrophins

1. Introduction

The majority of adult cochlear implant (CI) recipients using current technology score above 80-percent correct on high-context sentences without visual cues (Zeng, 2004), and the goals for the best performing subjects now include better speech reception in noisy environments and music perception (Rubenstein et al., this issue). Further, CI electrodes are now being implanted and used in combination with hearing aids in individuals with significant residual hearing (Turner et al., this issue). The success of this “electro-acoustic” hearing has re-focused attention on reducing trauma during CI implantation, maintaining residual hearing (Fraysse et al., 2006; James et al., 2006), and on the importance of the condition of the cochlea and auditory nerve in CI function. In fact, intra-scalar delivery of drugs (anti-inflammatory agents or neurotrophins) has been proposed in human CI subjects to promote improved SG survival, and CI electrodes modified for drug delivery already have been developed (Hochmair et al., 2006; Paasche et al., 2003; Shepherd and Xu, 2002). However, animal studies examining the effects of potential neurotrophic agents and exploring alternative, less invasive strategies for promoting SG survival have been relatively limited to date.

Further, thousands of very young deaf children, including congenitally deaf infants, now are receiving CIs (Dettman et al., 2007). Although it is encouraging that many children with CIs eventually can be mainstreamed into public education settings, it is also important to recognize that many pediatric CI users lag far behind in language development (Ponton et al., 1996; Svirsky et al., 2000; Geers, 2004; Nicholas and Geers, 2007), and some children cannot even discriminate between the most basal and most apical electrodes of their implants (Dawson et al., 1997). The rationale for implanting at very young ages is based on the belief that there is a critical period for language acquisition (Eggermont and Bock, 1986; Rubens, 1986; Rubens and Rapin, 1980) as suggested by the profound effects of auditory deprivation in congenitally deaf children and adults and by research demonstrating that implantation before the age of two results in significant advantages in speech perception (Svirsky et al., 2000; Svirsky et al., 2004; Geers, 2004; Nicholas and Geers, 2007). Of course, many studies in animals also have suggested that auditory deprivation during maturation is especially harmful in causing degeneration and/or reorganization in the central auditory system (Blatchley et al., 1983; Eggermont and Bock, 1986; Harris and Rubel, 2006; Kitzes, 1996; Moore and Kitzes, 1985; Moore and Kowalchuk, 1988; Niparko and Finger, 1997; Nordeen et al., 1983; Russell and Moore, 1995).

With pediatric implants, it is generally assumed that restoring input during this critical period will be more effective in preventing the degenerative consequences of deafness and that the immature auditory system will be more plastic, better able to adapt to electrical stimulation. However, the increased plasticity that characterizes critical periods of nervous system development might also have negative consequences. Stimulation delivered in a particular format might entrain the immature auditory system into an aberrant organization that could be ineffective for processing other patterns or formats introduced later in life (Leake et al., 2000a,b; Leake and Rebscher, 2004). Studies in the visual system have shown that early restricted or aberrant inputs can have profound effects on central nervous system development that are irreversible due to developmental critical periods. Broadly distributed, synchronous input to the retina (e.g., electrical stimulation of the optic nerve or stroboscopic illumination) in the immature visual system causes profound changes in central processing that are not reversible if normal visual input is later restored (e.g., Altman et al.,1987; Mower and Cristen, 1985; Stryker and Strickland, 1984; Weiliky and Katz, 1997).

With so many very young, congenitally deaf children now receiving CIs, we suggest that it is important to better understand the effects of electrical stimulation on the deafened, developing auditory system. A major goal of our research has been to examine the factors and mechanisms underlying degeneration of the cochlear SG neurons and the CN after early deafness and the neurotrophic effects elicited by electrical stimulation of the cochlea. Our previous studies have shown that in cats deafened as neonates by ototoxic drugs, intracochlear electrical stimulation (ICES) delivered by a cochlear implant partially prevents the retrograde degeneration, which otherwise is progressive following deafness (Leake et al., 1999; Leake and Rebscher, 2004). Stimulation that is specifically designed to be “temporally challenging” to the central auditory system (see below, section 3) can be effective in maintaining a higher density of SG neurons as compared to the SG in the contralateral, non-stimulated cochlea, when the stimulation is continued over several months (Leake and Rebscher, 2004; Leake et al., 2007). However, although neurotrophic effects elicited by electrical stimulation were highly significant in these studies, neuronal survival was still far from normal. Therefore, it is critical to better understand the factors that determine the efficacy of electrical stimulation in eliciting these effects. Other potential neurotrophic factors that play a role in promoting neural survival and might be used in conjunction with electrical stimulation are also of great interest.

Note that all procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, San Francisco and conformed to all NIH guidelines. All animals included in these studies were bred in a closed colony maintained at the University of California San Francisco.

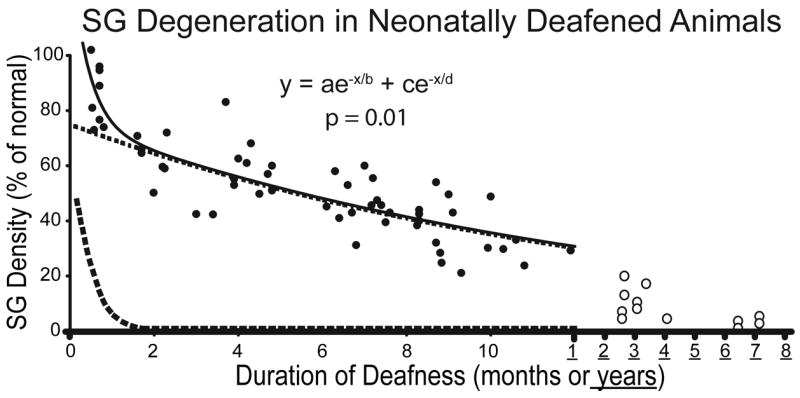

2. Data from animal models suggest two phases in spiral ganglion cell degeneration after deafness induced by ototoxic drugs

We have examined the functional and anatomical effects of auditory deprivation and chronic ICES in several deaf animal models. Many studies have been conducted in cats deafened as neonates by daily injections of the ototoxic aminoglycoside antibiotic, neomycin sulfate (60 mg/kg SQ) for the first 16 to 21 days after birth. Kittens are deaf at birth due to the immaturity of their auditory system (for review see Walsh & Romand, 1992). The neomycin destroys the cochlear hair cells and causes profound hearing loss before adult-like hearing sensitivity would normally develop at about 21 days postnatal (Leake et al., 1997; Walsh and McGee, 1986; Walsh et al., 1982; Walsh and Romand, 1992). Thus, these animals have no normal auditory experience and model congenital bilateral profound hearing loss. Hair cell degeneration in these animals leads to subsequent degeneration of the primary afferent cochlear spiral ganglion (SG) neurons and their central axons that form the auditory nerve, as in virtually all deafness etiologies in humans, (Hawkins et al., 1977; Johnson et al., 1981; Nadol, 1981; Otte et al., 1978; Ylikoski, 1974). Initial SG cell degeneration is evident by 2–3 weeks postnatal (Leake et al., 1997) and is progressive and continues for many months to years (Leake and Hradek, ‘88). Figure 1 illustrates the time course of SG degeneration with data from control (non-implanted) ears of neonatally deafened animals from earlier published reports (Leake et al., 1992; 1995; 1997; 1999). There is substantial individual variability, but decreasing SG survival (expressed as percentage of normal area fraction, a measure of the relative area of Rosenthal’s canal occupied by SG cells) is strongly correlated with duration of deafness. Because cochlear pathology is highly symmetrical in the two ears of individual animals (Leake et al., 1999; 2007), the effects of unilateral ICES can be systematically evaluated using within-animal paired comparisons.

Figure 1.

Data illustrating SG degeneration in control, non-stimulated ears of cats deafened as neonates by daily injections of neomycin sulfate starting the day after birth. Mean SG area fraction (an unbiased measure of cell density, averaged for the entire cochlea) is expressed as percent of normal. Decreasing SG density is correlated with longer duration of deafness, although there is considerable individual variability. The data have been fitted to a two-time constant model, shown by the 2 exponential functions (dashed lines) and a combined function (solid line) as shown on the graph. Reprinted from Leake et al., 2007 (Fig. 11b) with permission from the Journal of Comparative Neurology, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

A recent further analysis of these data, to calculate the rate of decrease in SG area fraction/day (Leake et al., 2007), suggested that there is an initial period of rapid reduction in SG neuronal density followed by a later phase of slower neural degeneration. Thus, the data were fitted to a two-time constant model, shown by the 2 exponential functions (dashed lines) and a combined function (solid line), which suggests an early rapid phase of SG cell degeneration over about the first 2 months of deafness and a slower phase thereafter. An important recent study from investigators at the University of Iowa (Alam and Green, 2005; Alam et al., 2007) demonstrated that there are also 2 phases in the degeneration of SG neurons after ototoxic drug induced deafness in rats, an early phase in which apoptosis is correlated with reduced neurotrophic signaling (reduced CREB phosphorylation) and a later phase (after ~postnatal day 60) when activity in the proapoptotic JNK-Jun signaling pathway is tightly correlated with apoptosis of SG neurons. We hypothesize that the two phases of SG cell degeneration observed in our neonatally deafened cats are correlated with the same mechanisms that underlie the two phases of apoptosis in rats, and further, that these mechanisms may be conserved across species and may be relevant to the human cochlea as well.

Figure 1 also shows SG data from animals studied at very long durations (>2.5 years) after neonatal deafening (open symbols). SG pathology is very severe and residual neural survival averages <10% of normal. We consider these long-deafened animals to comprise a separate and very valuable animal model, in which we have investigated the long-term effects of severe auditory nerve degeneration upon efficacy and selectivity of electrical stimulation delivered by a cochlear implant. Other studies have been conducted in animals deafened at 30 days postnatal rather than neonatally as a model of early acquired hearing loss.

3. Factors influencing neurotrophic effects of electrical stimulation on SG neurons in cats deafened as neonates

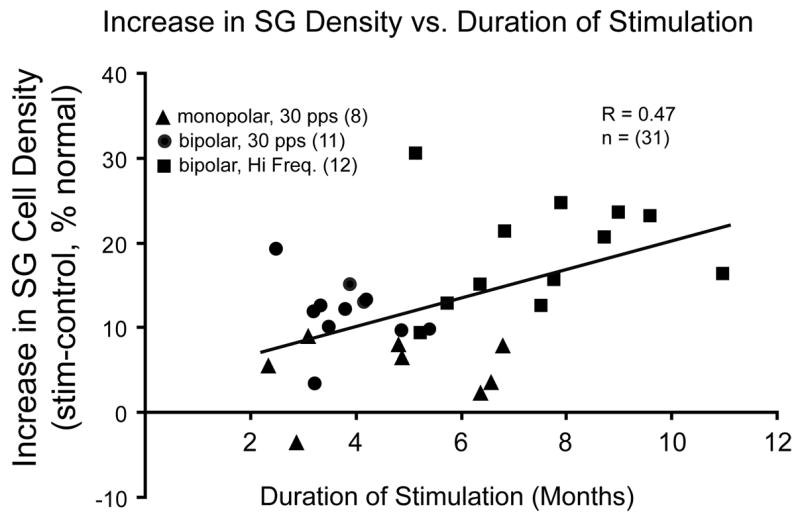

Several of our earlier studies evaluated the histopathological and functional consequences of both intra- and extracochlear electrical stimulation using various electrical signals in neonatally deafened cats (Leake et al., 1991; 1992; 1999; 2000a,b). Recently, we have reported findings from neonatally deafened cats that received a unilateral cochlear implant at ~8 weeks of age and ICES for periods of 8–9 months, using electrical signals explicitly designed to be temporally challenging to the central auditory system (Leake & Rebscher, 2004; Leake et al., 2007). Specifically, these signals were modulated trains of biphasic pulses that had carrier rates of 300 pps (near the upper limit of phase-locking for neurons in the auditory midbrain) and were sinusoidally amplitude modulated at 30 Hz (well above the maximum modulation frequency that cortical neurons normally can follow). Following stimulation, morphometric studies showed a highly significant difference in SG density, with SG area fraction being ~20% higher in the stimulated cochleae than in the non-stimulated contralateral ears in paired comparisons (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Increase in SG density is shown for individual subjects in 3 different experimental groups as a function of duration of electrical stimulation. Stimulation delivered by a monopolar electrode near the round window (triangles) appears to elicit less effect on SG density for a given duration of stimulation. In the remaining groups, greater increase in SG survival is correlated with longer duration of stimulation (R=0.48); data also suggest that higher frequency electrical stimulation (squares), such as 300 pps amplitude modulated pulse trains at 30 Hz, may elicit a greater effect than low frequency stimulation (dots), for similar durations. Reprinted from Leake and Rebscher, 2004 (Fig. 4.5) with permission from Springer-Verlag, New York.

Several other research groups also have reported neurotrophic effects of electrical stimulation in promoting SG survival. Lousteau (1987), Hartshorn et al. (1991), and Miller and Altschuler et al. (1995; 1996) demonstrated increased SG cell survival after chronic ICES in guinea pigs deafened by ototoxic drugs and implanted as young adults. In contrast, other studies have failed to find trophic effects in vivo in guinea pigs (Li et al., 1999), and Shepherd and coworkers (Araki et al., 1998; Shepherd et al., 1994) found no overall difference in SG cell survival after chronic ICES in cats deafened at an early age by ototoxic drugs, although recently they reported a significant regional increase in SG survival in partially deafened cats and a consistent increase in the size of stimulated SG cells (Coco et al., 2007).

Thus, it is important to define the specific factors required to elicit the survival-promoting effects of ICES on SG neurons that we have observed. Figure 2 shows data for a large group of subjects studied in 3 different ICES experiments, comparing the differences in SG density between the two ears in deafened animals as a function of duration of stimulation (Leake and Rebscher, 2004). Animals stimulated using a monopolar electrode at the round window (triangles) clearly comprised a separate group, with little effect of ICES on SG density as compared to other groups stimulated for similar periods. We have suggested that monopolar ICES may directly activate the auditory nerve axons within the modiolus (Leake et al.,’95), which may not be effective in eliciting trophic effects within the parent SG cells. Comparing the other ICES groups in Figure 2, animals stimulated using higher frequency, modulated signals (squares) show greater trophic effects of ICES than those stimulated with simple low frequency (30 pps) pulse trains (circles). However, the higher frequency ICES group also experienced longer periods of ICES. Thus, although these data do not define the relative contributions of duration and stimulus frequency/complexity, they suggest that prolonged, temporally challenging ICES elicits substantial neurotrophic effects, and that both factors may contribute.

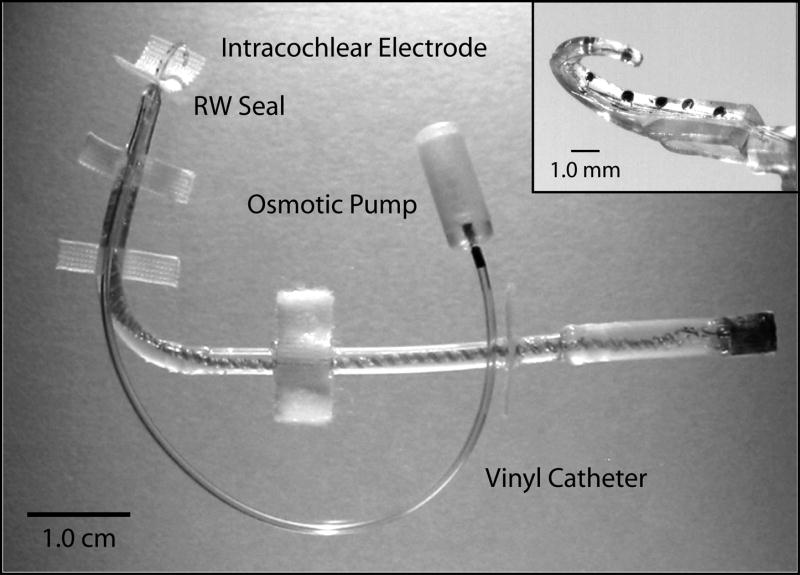

One interesting finding in these experiments was that chronic ICES reduced SG degeneration throughout most of the cochlea (Leake et al., 1999; Leake and Rebscher, 2004; Leake et al, 2007). In recent experiments, ICES intensity was set at relatively low current levels, 2 dB above electrically-evoked auditory brainstem response (EABR) thresholds, and ICES was delivered on 2 bipolar channels. Final electrophysiological experiments conducted in the inferior colliculus (IC) in these subjects indicated that the chronic stimulation excited very broad sectors of the IC, ranging from 62 to 98% of the entire IC frequency gradient (Leake et al., 2007). Because minimum IC thresholds are systematically lower than the EABR thresholds that are used to set stimulation levels (Beitel et al., 2000a, 2000b), the chronically applied levels of just 2 dB above EABR threshold were sufficient to activate the central auditory system (and presumably the auditory nerve) across a broad range of frequencies. Such relatively broad activation of the auditory nerve may be necessary to elicit significant increases in SG survival across a group of deafened subjects, given the inter-subject variability commonly seen after ototoxic drug administration. Thus, we suggest that another important factor for eliciting trophic effects is efficacy or distribution of electrical activation across the auditory nerve, which is largely determined by the specific electrodes used to deliver chronic stimulation. In our cat studies, multichannel cochlear implants were custom fabricated for the feline scala typmani. Specific features of these electrodes such as geometry, size and orientation of the stimulating sites, proximity of the device to the SG neurons, and shape and position of the insulating carrier were systematically optimized to provide selective stimulation on several intracochlear channels, to increase dynamic range for ICES and to limit electrical and neural interaction among channels (Rebscher et al., 2007; See Fig. 6). Due to its coiled shape, formed in a mold that reflects the dimensions and shape of the cat scala tympani, the UCSF feline electrode extends a full coil into the cochlea, surrounding the auditory nerve and stimulating to much lower frequencies than is possible using straight electrodes or shortened human CI electrodes. We believe that, due to these attributes, use of the specialized feline implant is one essential reason that we have demonstrated consistent trophic effects of ICES.

Figure 6.

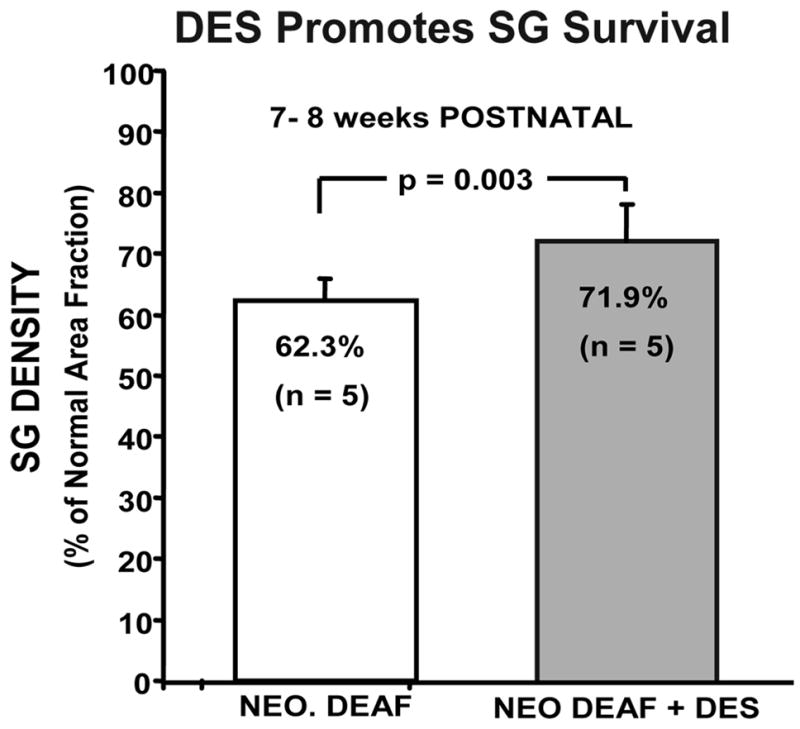

Cats studied at 7–8 wks of age after neonatal deafening (left bar) show significant SG degeneration. The data on the right show a significant increase of about 10% in SG density (% of normal area fraction) in another group of neonatally deafened animals that received injections of the selegiline (−)-desmethyldeprenyl and were studied at the same age. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

Finally, it is also important to note that studies of cochlear pathology in animal models have shown clearly that CI insertion trauma results in regional SG loss beyond that caused by the deafening procedure (Leake et al., 1999; Leake and Rebscher, 2004). Thus, strategies for reducing insertion trauma or ameliorating its effects in clinical CIs could be of great importance to the field.

4. Functional significance of SG neuron survival

Another significant question with respect to SG neural survival is what functional role peripheral nerve survival plays in CI function. Recent studies of individual human temporal bones from deceased CI recipients have reported that there is no correlation between the total residual SG neural population and speech discrimination scores (Fayad and Linthicum, 2006; Khan et al, 2005a; Nadol and Eddington, 2006; Nadol et al., 2001). This work serves to emphasize the point that many different variables likely contribute to the performance variability with clinical CIs. Although the studies reported to date do indicate that performance variability cannot be explained completely by SG survival alone, we suggest that it is inappropriate to conclude from the still relatively limited available data that SG survival is irrelevant to or does not influence CI performance. An alternative explanation of these findings might be that the methods applied were inadequate for elucidating how SG density interacts with other features of the implanted cochlea (e.g. electrode position and geometry, bone growth, etc.) to determine CI performance. In fact, more detailed analyses using 2D reconstructions to evaluate the number of surviving SG cells in the regions near individual electrodes (Khan et al, 2005b) have reported significant correlations between psychophysical measures (last threshold and maximum comfortable loudness levels for individual electrodes) and SG counts in 2 of 5 subjects. These authors suggest that 3D reconstruction techniques will be required to fully assess the impact of peripheral anatomy on patient performance.

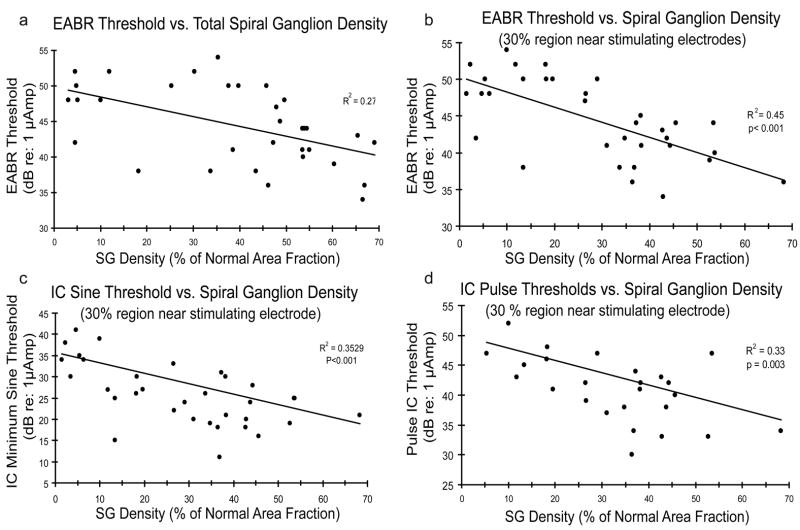

In animal models, some of the potentially important variables can be better controlled across subjects (e.g., the extent and type of initial pathology, design and position of intracochlear electrodes), and it is possible to demonstrate a significant correlation between SG density and electrophysiological thresholds in individual subjects. Figure 3 shows correlations obtained between values for SG density in individual implanted cats and the electrically-evoked auditory brainstem response (EABR) thresholds and minimum neural thresholds recorded in the inferior colliculus in response to ICES in the same animals. It should be noted, however, that these correlations are only significant if we include data for long-deafened animals with very severe cochlear pathology (see Fig. 1), suggesting that relatively large differences in neural survival are required to demonstrate significant correlations to electrophysiological thresholds. It is particularly interesting to note that the correlation between neural density and electrophysiological thresholds is improved if we estimate the SG density in the region near the stimulating electrodes, rather than the overall SG density averaged for the entire cochlea (Fig. 3a,b), similar to the findings by Khan et al (2005b) in human temporal bone studies.

Figure 3.

Electrophysiological thresholds are plotted as a function of SG density for individual neonatally deafened animals examined as adults. a,b. EABR thresholds are correlated with SG density averaged over the entire cochlea (a), and the correlation is improved for the same group of subjects if we use the values for SG density in the 30% sector of the cochlea nearest the stimulating electrode pair, rather than overall SG survival. c, d. Minimum thresholds in the inferior colliculus for a 30 Hz electrical sinusoidal stimulus (c) and for 200 μsec/phase electrical pulses are also better correlated with regional SG survival.

Finally, note that the human temporal bone studies conducted to date seeking to relate peripheral pathology to CI performance have focused on speech perception and relatively basic psychophysical tasks, for which it is possible that a minimal number of residual SG neurons and 4–6 discriminable CI channels may be sufficient. With the continuing increases in CI capabilities over time and as the criteria for selection of CI candidates are relaxed, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that better neural survival may be important for other aspects of auditory perception, such as the ability to differentiate between virtual channel stimuli, to better discriminate speech in noise, or to appreciate music.

5. The role of neurotrophins in survival of SG neurons after neonatal deafness

As noted above, ICES delivered for several months under appropriate conditions can promote significantly higher SG density in stimulated cochleae as compared to the non-implanted ears of deafened animals. However, it is clear from these studies that stimulation only partially prevents SG degeneration after deafness. Thus, much recent work has focused on examining other neurotrophic factors that may be employed in conjunction with ICES to further promote neural survival.

Multiple in vivo studies have reported that certain neurotrophic factors (usually administered via perilymphatic infusion) can promote SG neuronal survival following deafness. The best-characterized neurotrophic factors are members of the nerve growth factor (NGF) family of proteins, and are called neurotrophins. Neurotrophins include NGF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and neurotrophin-4/5, each of which binds to specific high-affinity receptors, the Trk family of receptors. Neurotrophins are particularly relevant to our studies of SG cell survival in neonatally-deafened animals because they regulate neuronal differentiation and survival during development (Korsching, 1993; Gao et al., 1995; Farinas et al., 2001; Fritzsch et al., 1999; Rubel and Fritsch, 2002) and are also involved in the development and maturation of the central auditory system (for review, see Fritzsch et al., 1999; Rubel and Fritzsch, 2002). Within the developing cochlea, neurotrophins are differentially distributed, with NT-3 expressed predominantly in the supporting cells of the organ of Corti, and BDNF expressed only in hair cells (Farinas, et al., 2001). Further, many in vivo studies have reported that exogenous administration of neurotrophins (Ernfors et al., 1996; Kanzake et al., 2002; McGuinnes and Shepherd, 2005; Miller et al., 1997; Schindler et al. 1995; Shepherd et al., 2005; Staecker et al., 1996, 1998; Zheng et al., 1995; Zheng and Gao, 1996) and other neurotrophic factors such as glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) (Ylikoski et al., 1998; Yagi et al., 2000) can protect SG neurons in adult animals from injury and promote improved survival after various insults, including ototoxic drugs.

We recently reported a study of the effects of GM1 ganglioside (Leake et al., 2007), a glycosphingolipid that has been reported to promote neuronal survival after injury (Wu et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Fighera et al., 2006) by potentiating the release of neurotrophins and activating trkB signaling (Bachis et al., 2002; Rabin et al., 2002; Duchemin et al., 2002; Bachis and Mocchetti, 2006). Some clinical trials in humans have reported GM1 to be of benefit in treating stroke, spinal cord injury and Alzheimers disease (Kharlamov et al., 1994; Geisler et al., 1993; Svennerholm, 1994), and in animal studies exogenous administration of GM1 has been reported to reduce SG degeneration after deafness (Parkins et al., 1999; Walsh and Webster, 1994). An important advantage of GM1 is that it can be administered systemically, rather than by cochlear infusion, as required for some other neurotrophins.

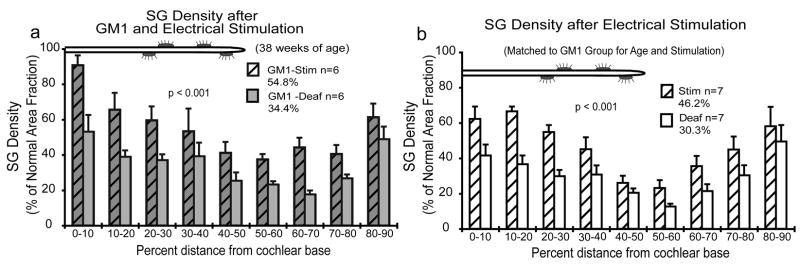

Figures 4a and 5 present data from cats that were deafened as neonates and received daily injections of GM1 beginning either at birth or at the time deafness was confirmed and continuing until 7–8 weeks of age (Leake et al., 2007). Both GM1 and non-GM1 deafened control groups (Fig. 4b) received a CI at 7–8 weeks of age and 6–8 months of unilateral ICES on 2 channels of the implant. ICES elicited a significant trophic effect, reducing the extent of SG degeneration in both the GM1 and non-GM1 groups as compared to the non-implanted ears. Further, statistical comparisons showed significantly higher SG density with GM1 followed by ICES as compared to the effects of ICES alone. An interesting additional finding in this study was that in the deafened non-stimulated ears, SG soma size was severely reduced several months after withdrawal of GM1 without electrical activation.

Figure 4.

a. SG data for 6 neonatally deafened cats treated with GM1 ganglioside for the period of several weeks before receiving a cochlear implant and studied after 6–8 months of chronic ICES. SG density was significantly higher in the stimulated ears than on the opposite side in both GM1 and non GM1 groups. SG survival after GM1 and electrical stimulation was 54% of normal, whereas in the comparison subjects shown in panel b that did not receive GM1 but were matched to the GM1 group for duration of deafness and stimulation, SG area fraction was 46.2%. This difference between the stimulated ears in the GM1 and stimulated ears in the non-GM1group was statistically significant (ANOVA Tukey test P<0.009). Bars indicate standard error of the mean. Figure reprinted from Leake et al., 2007 (Fig. 3) with permission from the Journal of Comparative Neurology, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 5.

Histological sections illustrate the trophic effects of GM1 ganglioside treatment and electrical stimulation in a neonatally deafened cat, studied after about 7 months of unilateral electrical stimulation delivered by a cochlear implant. Mean SG density in the region shown (20–30% from base) was about 80% of normal in the stimulated ear (a,c) vs 44% on the control side (b,d). Images on the left also show better survival of the radial nerve fibers in the stimulated cochlea.

Note that in control animals studied immediately after GM1 treatment (that is, at ~8 weeks of age when the groups shown in Figure 4 were implanted), SG density averaged 74.3% of normal for the GM1 group as compared to 62.3% for the non-GM1 group. Clearly, this initial level of SG survival was not fully maintained over subsequent prolonged periods of ICES. This finding suggests that GM1 might be more effective if treatment were continued for a longer period combined with ICES, or perhaps if GM1 were withdrawn more gradually over the initial period of ICES. These are interesting areas deserving further study in the future. Although our data suggest that GM1 can reduce initial SG degeneration after deafness, it is critical to determine if neurotrophic effects can be maintained over the long-term by CI stimulation. Otherwise, GM1 and other strategies for modulating neurotrophic factors may be of little practical value clinically if “rescued” neurons are not viable over the long term.

We also have conducted a study of a new selegiline compound in collaboration with Dr. William Tatton (Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, NY). The selegiline (−)-deprenyl has been used clinically for many years to treat Parkinson’s disease (Tatton et al., 1999) and Alzheimer’s disease (Tatton and Chalmers-Redman, 1996). Deprenyl has been reported to act as an MAO-B inhibitor, but Tatton et al. suggested that it is actually the drug’s primary metabolite, (−)-desmethyldeprenyl (DES) that reduces neuronal apoptosis by a mechanism that requires gene transcription and involves maintenance of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Tatton et al., 1999). Mediated by GAPDH binding, DES was suggested to increase mitochondrial BCL-2 and BCL-x levels, decrease BAX levels, and thereby prevent the permeability transition pore from opening, thus preventing apoptosis (Carlile et al., 2000; Tatton and Chalmers-Redman, 1996).

In our in vivo study, daily injections of DES (0.1 mg/kg SQ) were administered to kittens after profound hearing loss was confirmed. At 7–8 weeks of age, DES administration resulted in a modest improvement in SG cell density as compared to age-matched deafened subjects that did not receive DES (72% vs. 62% of normal; Fig. 6). However, when deafened animals received DES injections for 6–7 months combined with ICES, results were highly variable, and a few young animals exhibited adverse reactions to the DES. Nonetheless, we suggest that the selegilines may still potentially be useful as an adjunct to cochlear implants, and it would be valuable in future research to evaluate in vivo administration of either the original clinically approved drug, deprenyl, or newer formulations such as rasagiline for potential effects on SG survival. Based on available data, we hypothesize that administration of deprenyl could be effective in ameliorating the initial phase of rapid SG degeneration immediately after deafness occurs, when neurotophic support is critical. The long clinical experience with deprenyl and the fact that it is administered orally are major advantages over other neurotrophins, which must be delivered directly to the inner ear either by osmotic pump, or by cell transplantation or gene-based therapies (e.g., viral vectors).

6. Intracochlear infusion of neurotrophins

It is our view that the key intracellular signaling mechanisms and pathways underlying the survival-promoting effects of ICES and potential neurotrophic agents are most efficiently investigated in cell culture preparations. Studies of cultured SG neurons by Green and coworkers have shown that SG survival is supported both by membrane depolarization and by neurotrophins (Hansen et al., 2001; Hegarty et al., 1997; Zha et al., 2001) and that there are multiple mechanisms underlying the protective effect of depolarization in vitro. Specifically, the survival-promoting effect of depolarization is mediated by L-type voltage gated Ca2+ channels and involves multiple distinct signaling pathways, including an autocrine neurotrophin mechanism, cAMP production and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMk)- mediated phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB. Moreover, the neurotrophins BDNF and NT-3 are expressed by SG neurons and promote survival by an autocrine mechanism that is additive with the effect of depolarization. We hypothesize that the neural activity elicited by electrical stimulation in our neonatally deafened animals is effective in engaging and driving these same mechanisms in vivo, and therefore, exogenous neurotrophins should be additive to the survival-promoting effects of electrical stimulation observed in these animals. In this context, it is worthwhile noting that the capacity of electrical stimulation to promote survival of SG neurons in vivo following deafening has been shown to depend on activation of L-type Ca2+ channels (Miller et al., 2003), similar to observations in vitro.

As mentioned previously, several recent in vivo studies have reported that direct cochlear infusion of neurotrophins (NTs), particularly BDNF, can promote improved SG survival following deafness (Gillespie et al., 2003; Miller et al., 1997; Miller et al., 2007; Shinohara et al., 2002; Staecker et al., 1996). Further, ICES has been reported to be additive to the effects of NTs (Kanzaki et al., 2002; Shepherd et al.,2005; Pettingill et al., 2007) in reducing SG degeneration. Based on these encouraging findings, new human cochlear implant electrodes that incorporate drug delivery systems already have been designed (Hochmair et al., 2006) and tested in animals (Paasche et al., 2003). However, studies to date have been conducted in rodents and are limited to quite short durations (e.g., 30 days). Little is known about the long-term effects of NTs, and one animal study has suggested that accelerated SG degeneration occurs after cochlear infusion of BDNF is terminated (Gillespie et al., 2003). Therefore, we are interested in studying neurotrophic effects over longer durations, and in different animal models that may better represent the slower time course of SG degeneration in the human cochlea. For this work our chronically implantable cat electrodes for multichannel ICES have been modified to incorporate a drug-delivery cannula that attaches to a mini-osmotic pump (Rebscher et al., 2007). An example of one of these electrodes is shown in Figure 7. The most recent generation of these drug-delivery electrodes can be fabricated with multiple drug delivery ports (e.g., one near the base and another at the apical end of the array).

Figure 7.

The current UCSF cat implant consists of the intracochlear electrode, shown here with 8 stimulation sites (inset), a sturdy percutaneous cable ending in a microconnector, and an intracochlear cannula connected to a vinyl catheter that is connected to a miniature osmotic pump. Dacron fabric tabs are attached directly to bone at the round window (RW seal), near the opening created in the bulla and beneath the temporalis muscle using VetBond™ tissue glue to secure the device. A silicon-impregnated subcutaneous cuff is sutured to the underlying neck muscle to further stabilize the percutaneous cable.

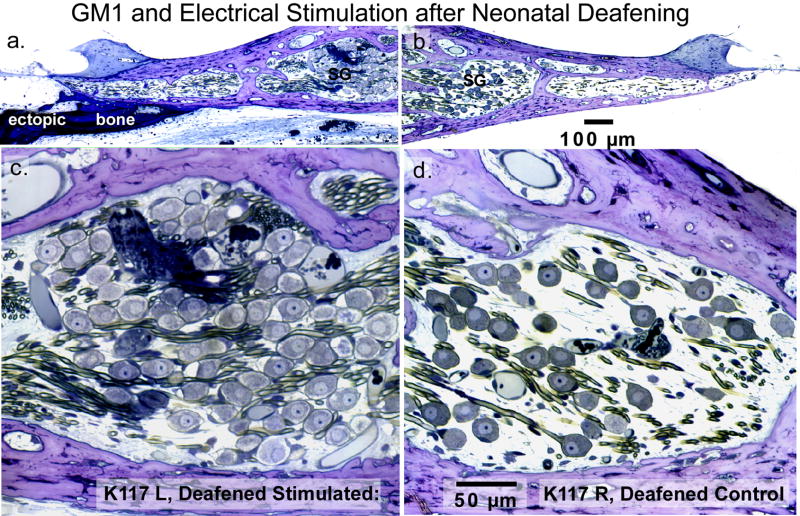

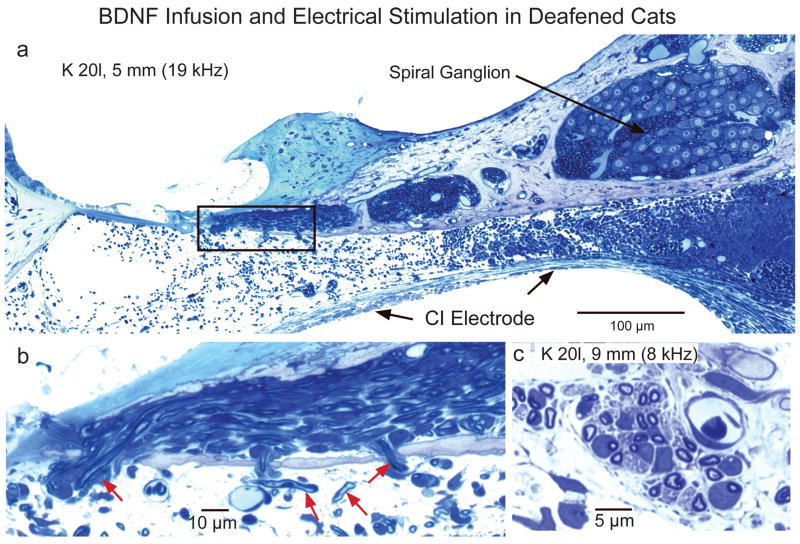

Preliminary data from our initial study with BDNF are shown in Figure 8. The images in Figures 8a and b show cochlear histology from a cat deafened neonatally and implanted one week later. BDNF was infused for 6 weeks, concomitant with 2-channel ICES. SG density, as determined using our standard point counting procedure to assess the area fraction of Rosenthal’s canal occupied by SG cell somata, appeared to be near normal throughout the cochlea (96% of normal overall, with a range of 63 to 122% in different cochlear regions in the BDNF ear; as compared to 71% overall density in the contralateral ear, with values ranging from 55% to 85% of normal). However, at least a large part of this difference was due to the fact that neurons were consistently larger in the BDNF/ICES cochlea, and these area fraction data reflect increase in cell size and cell number. The finding of significantly larger SG cell size also has been reported in previous studies with intracochlear BDNF infusion via osmotic pumps (Shepherd et al., 2005; Pettingill et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2007). Most studies conducted to date have relied on counts of cell nuclei to estimate SG survival, and our data indicate that increases in cell size are associated with parallel increases in nuclear size, which make counts of the nuclei unreliable for estimating the numbers of surviving neurons. Thus, we suggest that it will be important in future studies to implement specific unbiased stereological methods, such as the physical dissector, to provide accurate information on the contributions of increase in neuronal number (survival) as opposed to increase in neuronal size after treatment with neurotrophins.

Figure 8.

a,b. Examples of histological sections from a cat deafened at 30 days of age and studied after 6 weeks of BDNF infusion and ICES. Note normal SG density, dense radial nerve fibers and ectopic myelinated fibers sprouting passing through the osseous spiral lamina and downward into the scala tympani above the CI electrode. Outlined area in a is shown in b at higher magnification. c. In another deafened cat studied after 15 weeks of BDNF and ICES, substantial numbers of sprouted fibers were observed to follow a spiral course for some distance under the degenerated organ of Corti within the scala tympani.

After BDNF infusion via an osmotic pump in developing animals, we have also observed sprouting of myelinated axons into the scala tympani above the implanted electrode (Fig. 8). Sprouting has been reported previously after infusion of BNDF and NT-3 in deafened guinea pigs (Miller et al., 2007; Staecker et al., 1996; Wise et al., 2005), although in the Wise et al. study (with no ICES) the sprouted fibers grew upward into the spiral limbus of the degenerated organ of Corti. Thus, the applied electrical stimulation in our study may have guided or attracted fibers to grow into the region above the electrode within the scala tympani. This potentially could provide closer coupling of the electrode-neural interface and lower thresholds. On the other hand, in the normal cochlea the radial nerve fibers take a straight radial trajectory to synapse on the hair cells. Thus, if sprouting fibers grow in a spiral direction, they could potentially compromise the selectivity of multichannel ICES. It will be important in future studies to examine in detail the conditions that elicit such re-sprouting and the trajectories and targets of such ectopic fibers.

7. The role of age at onset of deafness and electrical stimulation in SG survival after early acquired hearing loss

To investigate the possible role of developmental critical or sensitive periods in degeneration of the SG and in stimulation-induced alterations in the cochlea and central auditory system, we have also examined cats deafened at 30 days of age (rather than at birth). In this experimental model of early-acquired hearing loss, animals were deafened using the same drug treatment as for neonatally deafened animals (daily injections of neomycin), but beginning at 30 days of age rather than at birth. In this group, profound hearing losses occurred by 7 to 8 weeks of age, and electrical stimulation was initiated about 1 week later and again continued over periods of more than 6 months. To determine whether the initial brief period of normal auditory function provided additional benefit for the trophic effects of subsequent ICES from a cochlear implant, data were compared with a group of neonatally deafened animals carefully matched to the 30-day deafened group for age at implantation and duration of ICES.

Control data from animals deafened at 30 days of age and studied at 7–8 weeks age (the time of implantation of other subjects) showed that SG density (70% of normal area fraction) was similar to that in neonatally deafened animals (64% of normal), suggesting the possibility of an accelerated time course of SG degeneration in the 30-day deafened group (Stakhovskaya et al., 2006). Data from implanted and stimulated 30 day-deafened animals showed a significant increase in SG density in the stimulated ears as compared to the deafened control side, indicating that ICES did significantly reduce neural degeneration in this group. However, there was no significant difference in SG density between the 30-day deafened and the neonatally deafened groups (Stakhovskaya et al., 2006). Although the auditory pathways are still immature at 30 days of age, deafening in this older group was initiated after the development of adult-like spontaneous activity in the auditory nerve and adult-like auditory brainstem responses, in contrast to the neonatally deafened group. Interestingly, these results do not provide evidence for a developmental critical period during the first postnatal month with respect to the effects of deafness on SG degeneration. Delaying the onset of deafness by more than 30 days and initiating stimulation immediately thereafter did not provide a significant advantage for SG survival over the long term.

8. Effects of age at onset of deafness and subsequent electrical stimulation on the developing cochlear nucleus

Previous histological studies of the cochlear nuclear complex (CN) in neonatally deafened, chronically stimulated cats have demonstrated profound degenerative changes in the CN that are progressive over many months to years (Lustig et al., 1994). As compared to normal adult cats, the CN of neonatally deafened cats showed marked reduction in the total volume of the CN to 76% of normal and reduction in the mean cross-sectional area of AVCN spherical cells to about 75% of normal (Lustig et al., 1994; Osofsky et al., 2001). These degenerative changes are consistent with many previous studies showing that neonatal auditory deprivation results in profound adverse effects within the cochlear nucleus (Coleman and O’Connor, 1979; Coleman et al., 1982; Rubel et al., 1984; 1990; Rubel and Fritzsch, 2002; Trune, 1982; Webster, 1983; 1988; Webster and Webster, 1977; 1979; for review see Harris and Rubel, 2006).

In a recent study designed to explore possible critical period effects of electrical stimulation in the CN, Stakhovskaya et al. (in press) compared the CN in neonatally deafened animals and in animals deafened at 30 days of age after an initial brief period of normal hearing. CN volume was significantly closer to normal in the 30-day deafened animals, as compared to age-matched neonatally deafened animals. This difference was observed both in younger groups examined at 8 weeks of age (the age at implantation of the older group) and in older animals studied at 8 months of age after more than 6 months of unilateral ICES (Fig. 9a). However, there was no significant difference between the CN volume ipsilateral to the stimulated ear and the contralateral CN in either the 30-day deafened or neonatally deafened group. Thus, an initial brief period of normal hearing had a significant impact in reducing the degenerative changes in the central auditory system following deafness, and this effect was maintained into adulthood; but restoring input through a cochlear implant at 8 weeks of age did not have any apparent significant additional effect in ameliorating this degeneration. These findings provide evidence for a developmental critical period that has a significant impact on both immediate and long-term consequences of deafness occurring at a young age.

Figure 9.

a. Mean total CN volumes in animals deafened as neonates compared to animals deafened at 30 days of age and normal adult cats. Following the brief period of normal auditory experience in the 30-day deafened group studied at 8 weeks of age, CN volume was significantly larger than in the age-matched neonatally deafened group. Similarly, in cats studied at ~8 months of age after several months of chronic ICES, the volume of the CN averaged only 67% of normal in the neonatally deafened group, whereas the CN in the 30-day deafened group was significantly larger and averaged 81% of normal. In both of these groups examined after chronic ICES, there was no difference between the CN on the stimulated side as compared the control deafened side, and the data from both ears are combined here in the groups studied at 8 months. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Figure modified and reprinted from Stakhovskaya et al. (In press; Figs. 2) with permission from Hearing Research, Elsevier. b. Mean cross-sectional areas of AVCN spherical cells are significantly larger on the stimulated side in both the 30-day deafened and neonatally deafened groups. Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean. Figure reprinted from Stakhovskaya et al. (In press; Fig. 4) with permission from Hearing Research, Elsevier.

In contrast to the findings on CN volume, electrical stimulation from the cochlear implant did elicit a modest but statistically significant difference in neuronal cell size (Stakhovskaya et al., in press). Specifically, the cross-sectional areas of spherical cell somata in the rostral AVCN were significantly larger in the CN on the side of the cochlear implant (average difference, 6% of normal) than in the contralateral CN of both neonatally deafened and 30-day deafened groups (Fig. 9b), similar to the previous report of Matsushima et al. (1991). These recent CN data were obtained from cats in recent experiments using temporally-challenging, 2-channel ICES that elicited mean increases in SG neural survival of about 20%. Thus, it is interesting and somewhat surprising that stimulation elicits only such a modest effect in forestalling the pronounced degenerative CN alterations after early deafness. One possible explanation is the delay that occurs before chronic ICES is initiated in our studies. Larsen’s (1984) classic study of CN development in cats showed an early growth phase in the AVCN with rapid increases in nuclear and cytoplasmic cross-sectional areas during the first month postnatal, followed by a longer period of maturation when the neurons gradually reach mature size, by about 12 weeks postnatal. In our neonatally deafened cats, the ototoxic drug injections occur during this early period of rapid development and ICES was initiated at ~7–8 weeks, well after this initial rapid growth phase. One hypothesis from this earlier finding was that intervention with the CI in these animals took place too late in development to prevent or reverse the profound effects of early deafness. However, in the 30-day deafened group in our recent studies, neomycin was administered for 16–21 days after postnatal day 30, and electrical stimulation was again introduced at 7–8 weeks postnatal, which was only ~7–10 days after profound deafness occurred in these animals; yet we still observed only modest differences in cell size and no difference in overall CN size with stimulation. Again, the findings suggest that there is an important sensitive period of development immediately following the onset of hearing and extending for at least 30 days, during which the CN changes induced by deafness are largely irreversible. It is important to note that the evidence available to date on the effects of deafness on CN degeneration in kittens does not distinguish between degeneration due to loss of neural activity and effects due to loss of other potential neurotrophic signals provided by the primary afferent spiral ganglion axons. Perhaps intracochlear electrical stimulation may only prevent or ameliorate degenerative CN changes to the extent that neural activity has the capacity to prevent SG degeneration. Overall, the brief period of normal auditory development and subsequent electrical stimulation in animals deafened at 30 days maintained CN volume at 81% of normal and spherical cell size at 86% of normal ipsilateral to the implant, as compared to 67% and 74% of normal, respectively, in the neonatally deafened group. Given the paucity of data addressing the CNS effects of ICES and critical periods, we suggest that this is clearly an area requiring more study in the future.

9. Topography of auditory nerve projections to the cochlear nucleus in cats after neonatal deafness and electrical stimulation

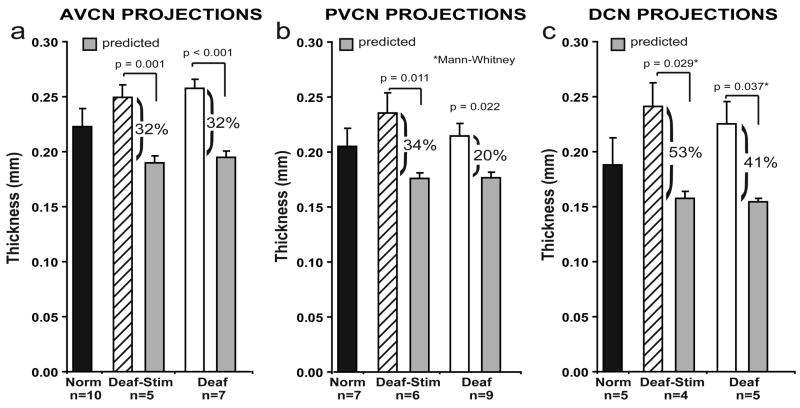

To further examine the consequences of early deafness on the central auditory system, we have also conducted studies using a neuroanatomical tracer to examine the SG projections to the CN in neonatally deafened cats and also in deafened animals after several months of ICES. Direct injections of neurobiotin™ were made into the SG to label small clusters of ganglion cells and their central axons. The CN projections in deafened animals were compared to normal controls. A clear topographic organization of CN projections into frequency-band laminae was evident in all neonatally deafened animals, despite severe auditory deprivation from birth (Fig. 10). However, when CN projections were measured (width of distribution across the CN frequency gradient) and normalized for the substantially smaller size of the CN, the projections in neonatally deafened animals were disproportionately broader than those in normal cats (Leake et al., 2006). Specifically, AVCN, PVCN and DCN projections from the deafened cochleae in this study averaged 39%, 26% and 48% broader, respectively, than the values predicted if they were proportionate to normal controls. Further, a more recent study in which we examined CN projections in neonatally deafened animals after 6 months of unilateral ICES showed very similar findings of projections that were proportionately broader than normal in deafened animals and also showed that there was no difference between projections from the electrically stimulated cochleae and projections from the contralateral non-implanted ears (Fig. 11; Leake et al., In press). These findings suggest that early normal auditory experience is essential for the development (or subsequent maintenance) of the topographic precision of SG-to-CN projections. After neonatal deafness, the cochleotopic specificity or precision of connections that underlie frequency resolution in the normal central auditory system is significantly reduced. Further, several months of ICES from a CI introduced at <8 weeks of age (at least with the stimulation paradigm used in our study) did not lessen or exacerbate these changes.

Figure 10.

Direct injections of the neuronal tracer NB into the SG labeled small clusters of ganglion cells and their central axons projecting to the CN. This image shows a representative coronal section through the CN of an adult cat studied after neonatal deafening and > 8 months of ICES. A clear tonotopic order of NB-labeled projection laminae is evident in the PVCN (lower arrows) and DCN (upper arrows) after 2 injections made in the SG at the frequencies indicated (calculated based upon the positions of the injection sites in the cochlea).

Figure 11.

Absolute CN projection thickness values measured in normal and neonatally deafened cats are similar. However, when projections in deaf animals are normalized for the significantly smaller CN volume after deafening, CN projection widths are proportionately broader than projections in normal adults, and this difference is highly significant in all 3 subdivisions of the cochlear nucleus. Further, there was no difference between projections from stimulated and non-stimulated cochleae, Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Figure reprinted from Leake et al. (In press; Fig. 6) with permission from Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, Springer.

It is interesting to note that in congenitally deaf white cats, degenerative alterations in individual auditory nerve synapses of the AVCN endbulbs of Held observed by Ryugo et al. (1997) were largely reversed by 3 months of electrical stimulation via a cochlear implant (Ryugo et al., 2005). Specifically, in these early deafened animals (suggested to model Scheibe dysplasia), the authors reported reduced terminal branching of the endbulbs of Held, reduction in synaptic vesicle density, striking hypertrophy of the postsynaptic densities and enlargement of synapse size. These changes were interpreted as a compensatory response to diminished transmitter release. Similar alterations were also reported in globular bushy cell terminals (Redd et al., 2000), whereas endings on multipolar cells showed less extensive changes (Redd et al., 2002). Significantly, the endbulbs of Held exhibited recovery of more normal synaptic structure after 3 months of electrical stimulation via a cochlear implant (Ryugo et al., 2005). These findings suggest that degenerative alterations in surviving synaptic terminals may be reversed with appropriate electrical stimulation in the neonatally deafened auditory system. In contrast, our studies indicate that ICES does not prevent the loss of a significant portion of the SG population after early deafness, and the degeneration of their projecting axons and synaptic terminals results in significant degeneration in the CN and reduction in the specificity of the SG-to-CN projections that are not reversed by electrical activation of the remaining afferents.

On the other hand, the classic studies of Moore (1985) and Kitzes (1995, 1996) demonstrated that neonatal ablation of one cochlea resulted in substantial reorganization of the central auditory projections, with the intact CN forming highly ectopic projections to the superior olivary nuclei and the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body and projections to the ipsilateral inferior colliculus more than doubling in size. Our current study provides a somewhat parallel experimental paradigm, in that animals were deafened as neonates, one ear remained deaf throughout life, and the other ear was activated by a cochlear implant beginning at 8 weeks of age and continuing into adulthood. Our findings of equivalent CN frequency band projections on the stimulated and contralateral sides and absolute widths that were only slightly larger than those in normal animals indicate that no major reorganization, ectopic projections or massive expansion in the primary afferent neural pathways occurs that is equivalent to the changes reported by Moore and Kitzes. From this perspective, our data on the specificity of projections in stimulated animals argue strongly for an inherent stability in the organization of the primary afferent neural pathways. In these neonatally deafened animals, the CN fails to grow sufficiently to achieve normal adult size, resulting in normal-sized projection laminae that are more overlapping in the deafened CN. Note that it is also conceivable that the projections from nearest neighbor SG neurons actually maintain relatively precise representations in the deafened CN, and that the proportionately broader projections represent an interdigitation of adjacent frequency band laminae. However, given the severe degeneration in the CN after neonatal deafening, we propose the more conservative interpretation that the proportionately broader projections relative to the cochleotopic gradient represent a degradation in the specificity of the primary afferent cochleotopic map and that the frequency resolution within the CN also may be less precise (e.g., for discrete stimulation by multiple channels of a cochlear implant).

10. Implications of CN findings for clinical cochlear implants

Visual system research has suggested that input activity exerts a powerful organizing influence in the developing nervous system. Specific spatiotemporal patterns of input are essential for the refinement of initial topographically broad or diffuse neuronal projections in the developing visual pathways into their precise adult patterns (Chiu and Weliky, 2003; Constantine-Paton et al.,1990; Feller et al., 1996; Goodman and Shatz,1993; Shatz,1996; Simon and O’leary,1992; Tao and Poo, 2005; Zhou et al., 2003). Normal refinement is prevented by delivering widely distributed, synchronous inputs to the retina (e.g., electrical stimulation of the optic nerve [Stryker and Strickland,1984; Weiliky and Katz,1997] or stroboscopic illumination [Cremieux et al.,1987; Eisele and Schmidt,1988; Schmidt and Tieman, 1989]), and this results in enlarged receptive fields in the IC and cortex. Further, segregation of inputs from the two eyes can be sharpened by exaggerating the temporal anti-correlation of their inputs (e.g., alternating monocular deprivation [Altman et al., 1987; Cynader and Mitchell,1980]). There is a limited “critical period” for these events in the visual system, but it can be extended substantially if experimental animals are profoundly deprived of sensory input as neonates (Cynader and Mitchell,1980, Mower and Cristen, 1985). Initial sensory input then triggers a critical period and reorganization that generally stabilizes over a period of 6–8 weeks in animal models, after which changes driven by aberrant inputs are largely irreversible.

The finding that the basic cochleotopic organization of the SG input to the central auditory system is maintained in deafened animals, despite profound hearing loss occurring at a very young age and before the onset of hearing, may have important implications for pediatric cochlear implants. If similar principles pertain to auditory system development in humans, then these findings suggest that the fundamental organization of the primary afferent neural connections, which underlie the cochleotopic organization of the central auditory system, is fundamentally intact even in congenitally deaf individuals and is not significantly altered by a period of several months of unilateral electrical stimulation delivered by a cochlear implant. This finding may be important for the application of contemporary CIs in congenitally deaf individuals, because these devices utilize the tonotopic organization of the auditory nerve to appropriately encode acoustic information across multiple channels of electrical stimulation. Clinical results with CIs generally tend to be poorer in congenitally deaf subjects than in individuals who have had some prior auditory experience (for reviews see: Geers, 2004; Niparko, 2004; Teoh et al., 2004a,b). Over time, however, many congenitally deaf children enjoy substantial benefit from their devices, and we suggest that the integrity of the basic cochleotopic organization of the auditory nerve projections to the central auditory system must be one of the factors underlying that success.

On the other hand, although the fundamental tonotopic organization of the central auditory pathways seems to be relatively “hardwired” at least within the CN, the precision of that organization may be significantly modified by deafness. If the proportionately broader SG-to-CN projections seen in neonatally deafened animals result in poorer frequency resolution, this would suggest that there may be some inherent limitations in the efficacy of multichannel cochlear implant stimulation in such congenitally deaf subjects. Specifically, the spatial (spectral) selectivity of the stimulation delivered on adjacent CI channels may be poorer in congenitally deaf CI users due to the greater overlap of central axons representing nearby frequencies within the CN. In this context, it is important to note that some congenitally deaf children who receive CIs cannot even discriminate between the most basal and most apical electrodes of their implants (Dawson et al.,1997). Given this limitation, such a CI user may be more dependent upon temporal features of the electrical stimuli delivered by the implant, and it may be advantageous to enhance the salience of such cues. For example, it might be advantageous even to remove some electrodes from the processor “map” or to reduce the pulse rate of electrically coded signals in order to reduce channel interaction.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health, Contract #HHS-N-263-2007-000540C and Grant #R01-DC00160. The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions of Steve Rebscher and Alexander Hetherington who fabricated the cochlear implant devices used in these studies and Elizabeth Dwan who assisted with the surgery, care and chronic stimulation of animals.

Abbreviations

- AVCN

anteroventral cochlear nucleus

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CI

cochlear implant

- CN

cochlear nucleus

- DES

(−)-desmethyldeprenyl

- DCN

dorsal cochlear nucleus

- EABR

electrically-evoked auditory brainstem response

- IC

inferior colliculus

- ICES

intracochlear electrical stimulation

- PVCN

posteroventral cochlear nucleus

- SG

spiral ganglion

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References Cited

- Altman L, Luhmann HJ, Greuel JM, Singer W. Functional and neuronal binocularity in kittens raised with rapidly alternating binocular occlusion. J Neurophysiol. 1987;58:965–980. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.58.5.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SA, Green SH. Inhibition of JNK signaling inhibits rat spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs) death in vitro. Assoc Res Otolaryngol Abs. 2005:25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Alam SA, Robinson BK, Huang J, Green SH. Prosurvival and proapoptotic intracellular signaling in rat spiral ganglion neurons in vivo after the loss of hair cells. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:832–852. doi: 10.1002/cne.21430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki S, Atsushi K, Seldon HL, Shepherd RK, Funasaka S, Clark GM. Effects of chronic electrical stimulation on spiral ganglion neuron survival and size in deafened kittens. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:687–695. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachis A, Rabin SJ, Del Fiacco M, Mocchetti I. Gangliosides prevent excitotoxicity through activation of trkB receptor. Neurotoxicity Res. 2002;4(3):225–134. doi: 10.1080/10298420290015836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachis A, Mocchetti I. Semisynthetic sphingoglycolipid LIGA20 is neuroprotective against human immunodeficiency virus-gp120-mediated apoptosis. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83(5):890–896. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitel RE, Vollmer M, Snyder RL, Schreiner CE, Leake PA. Behavioral and neurophysiological threshold for electrical cochlear stimulation in the deaf cat. Audiology and Neuro-Otology. 2000a;5:31–38. doi: 10.1159/000013863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitel RE, Snyder RL, Schreiner CE, Raggio MW, Leake PA. Electrical cochlear stimulation in the deaf cat: Comparisons between psychophysical and central auditory neuronal thresholds. J Neurophysiol. 2000b;83:2145–2162. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatchley BJ, Williams JE, Coleman JR. Age-dependent effects of acoustic deprivation on spherical cells of the rat anteroventral cochlear nucleus. Exp Neurol. 1983;80:81–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(83)90008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile GW, Chalmers-Redman RME, Tatton NA, Pong A, Borden KE, Tatton WG. Reduced apoptosis after nerve growth factor and serum withdrawal: Conversion of tetrameric glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase to a dimmer. Mol Pharm. 2000;57:2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coco A, Epp SB, Fallon JB, Xu J, Millard RE, Shepherd RK. Does cochlear implantation and electrical stimulation affect residual hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons? Hear Res. 2007;225(1–2):60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C, Weliky M. Synaptic Modification by vision. Science. 2003;300:1890–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.1086934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JR, O’Connor P. Effects of monaural and binaural sound deprivation on cell development in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of rat. Exp Neurol. 1979;64:533–566. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(79)90231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J, Blatchley BJ, Williams JE. Development of the dorsal and ventral cochlear nuclei in rat and effects of acoustic deprivation. Dev Brain Res. 1982;4:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(82)90104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantine-Paton M, Cline HT, Debski E. Patterned activity, synaptic convergence and the NMDA receptor in developing visual pathways. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:129–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremieux JG, Orban A, Duysens J, Amblad B. Response properties of area 17 neurons in cats reared in stroboscopic illumination. J Neurophysiol. 1987;57:1511–1535. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.5.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cynader M, Mitchell DE. Prolonged sensitivity to monocular deprivation in dark-reared cats. J Neurophysiol. 1980;43:1026–1040. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.4.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson PW, Clark GM. Changes in synthetic and natural vowel perception after specific training for congenitally deafened patients using a multichannel cochlear implant. Ear and Hearing. 1997;18:488–501. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199712000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman SJ, Pinder D, Briggs RJ, Dowell RC, Leigh JR. Communication development in children who receive the cochlear implant younger than 12 months: risks versus benefits. Ear Hear. 2007;28(2 Suppl):11S–18S. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31803153f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchemin AM, Ren Q, Mo L, Neff NH, Hadjiconstantinou M. GM1 ganglioside induces phosphorylation and activation of Trk and Erk in brain. J Neurochem. 2002;8:696–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisele LE, Schmidt JT. Activity sharpens the regenerating retinotectal projections in goldfish: Sensitive period for strobe illumination and lack of effect on synaptogenesis and on ganglion cell receptive field properties. J Neurobiology. 1988;19:395–411. doi: 10.1002/neu.480190502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ, Bock GR, editors. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockholm) Suppl. Vol. 429. 1986. Critical periods in auditory development; pp. 1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernfors P, Duan ML, El-Shamy WM, Banlon B. Protection of auditory neurons from aminoglycoside toxicity by neurotrophin-3. Nat Med. 1996;2:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinas I, Jones KR, Tessarollo L, Vigers AJ, Huang E, Kirstein M, de Caprona DC, Coppola V, Backus C, Reichardt LF, Fritzsch B. Spatial shaping of cochlear innervation by temporally regulated neurotrophin expression. J Neurosci. 2001;21(16):6170–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06170.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayad JN, Linthicum FH., Jr Multichannel cochlear implants: relation of histopathology to performance. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1310–1320. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000227176.09500.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller MB, Wellis DP, Stellwagen D, Werblin DFS, Shatz CJ. Requirement for cholinergic synaptic transmission in the propagation of spontaneous retinal waves. Science. 1996;272:1182–1187. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fighera MR, Royes LFF, Furian AF, Olivera MS, Fiorenza NG, Frussa-Filho R, Petry JC, Coelho RC, Mello CF. GM1 gangliosides prevents seizures, Na+, K+-ATPase activity inhibition and oxidative stress induced by glutaric acid and pentylenetetrazole. Neurobio Disease. 2006;22(3):611–623. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraysse B, Macias AR, Sterkers O, Burdo S, Ramsden R, Dequine O, Klenzner T, Lenarz T, Rodriguez MM, Von Wallenberg E, James C. Residual hearing conservation and electroacoustic stimulation with the nucleus 24 contour advance cochlear implant. Otol Neuroto. 2006;27(5):624–633. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000226289.04048.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsch B, Pirvola U, Ylikoski J. Making and breaking the innervation of the ear: Neurotophic support during ear development and its clinical implications. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;295(3):369–82. doi: 10.1007/s004410051244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W-Q, Zheng JL, Karihaloo M. Neurotrophin-4/5 (NT-4/5) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor act at later stages of cerebellar granule cell differentiatiation. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2656–2667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02656.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers AE. Speech, language and relating skills after early cochlear implantation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:634–638. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler FH, Dorsey FC, Coleman WP. GM-1 ganglioside and motor recovery following human spinal cord injury. J Emerg Med. 1993;11(Suppl 1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie LN, Clark GM, Bartlett PF, Marzella PL. BDNF-induced survival of auditory neurons in vivo: Cessation of treatment leads to accelerated loss of survival effects. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71(6):785–90. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CS, Shatz CJ. Developmental mechanisms that generate precise patterns of neuronal connectivity. Cell 72/Neuron. 1993;10:77–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MR, Zha XM, Bok J, Green SH. Multiple distinct signal pathways, including an autocrine neurotrophic mechanism contribute to the survival-promoting effect of depolarization on spiral ganglion neurons in vitro. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2256–2267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02256.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Rubel EW. Afferent regulation of neuron number in the cochlear nucleus: Cellular and molecular analyses of a critical period. Hearing Res. 2006;216–217:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorn DO, Miller JM, Altschuler RA. Protective effect of electrical stimulation in the deafened guinea pig cochlea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:311–319. doi: 10.1177/019459989110400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JE, Jr, Stebbins WC, Johnsson LG, Moody DC, Muraki A. The patas monkey as a model for dihydrostreptomycin ototoxicity. Acta Otolaryngol. 1977;83:123–129. doi: 10.3109/00016487709128821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty JL, Kay AR, Green SH. Trophic support of cultured spiral ganglion neurons by depolarization exceeds and is additive with that by neurotrophins or cAMP and requires elevation of [CA2+]i within a set range. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1959–1970. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-01959.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochmair I, Nopp P, Jolly C, Schmidt M, Schößer H, Garnham C, Anderson I. MED-EL cochlear implants: state of the art and a glimpse into the future. Trends in Amplification. 2006;10(4):201–220. doi: 10.1177/1084713806296720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James CJ, Fraysse B, Deguine O, Lenarz T, Mawman D, Ramos A, Ramsden R, Sterkers O. Combined electroacoustic stimulation in conventional candidates for cochlear implantation. Audiol Neurootol. 2006;11(Suppl 1):57–62. doi: 10.1159/000095615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson LG, Hawkins JE, Jr, Kingsley TC, Black FO, Matz GJ. Aminoglycoside-induced inner ear pathology in man, as seen by microdissection. In: Lerner SA, Matz GJ, Hawkins JE Jr, editors. Aminoglycoside Ototoxicity. Little, Brown and Co; Boston: 1981. pp. 389–408. [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki S, Stover T, Kawamoto K, Priskorn DM, Altschuler RA, Miller JM, Raphael Y. GDNF and chronic electrical stimulation prevent VIII cranial nerve degeneration following denervation. J Comp Neurol. 2002;454:450–360. doi: 10.1002/cne.10480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AM, Handzel O, Burgess BJ, Damian D, Eddington DK, Nadol JB., Jr Is word recognition correlated with the number of surviving spiral ganglion cells and electrode insertion depth in human subjects with cochlear implants? Laryngoscope. 2005a;115:672–677. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000161335.62139.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AM, Whiten DM, Nadol JB, Jr, Eddington DK. Histopathology of human cochlear implants: correlation of psychophysical and anatomical measures. Hear Res. 2005b;205:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharlamov A, Zivkovic I, Polo A, Armstrong DM, Costa E, Guidotti A. 4.LIGA20, a lyso derivative of ganglioside GM1, given orally after cortical thrombosis reduces infarct size and associated cognitive deficits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;91:6303–6307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzes L. Anatomical and physiological changes in the brainstem induced by neonatal ablation of the cochlea. In: Salvi RJ, Henderson D, editors. Auditory System Plasticity and Regeneration. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1996. pp. 256–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzes LM, Kageyama GH, Semple MN, Kil J. Development of ectopic projection s from the ventral cochlear nucleus to th superior olivary complex induced by neonatal ablation of the contralateral cochlea. J Comp Neurol. 1995;353(3):341–63. doi: 10.1002/cne.903530303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsching S. The neurotrophic factor concept: A reexamination. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2739–2748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02739.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen SA. Postnatal maturation of the cat cochlear nuclear complex. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1984;217:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake PA, Hradek GT. Cochlear pathology of long term neomycin induced deafness in cats. Hearing Res. 1988;33:11–34. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake PA, Hradek GT, Snyder RL, Rebscher SJ. Chronic intracochlear electrical stimulation induces selective survival of spiral ganglion cells in neonatally deafened cats. Hearing Res. 1991;54:251–271. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]