Abstract

NR3 subtype glutamate receptors have a unique developmental expression profile, but are the least well-characterized members of the NMDA receptor gene family, which have key roles in synaptic plasticity and brain development. Using ligand binding assays, crystallographic analysis, and all atom MD simulations, we investigate mechanisms underlying the binding by NR3A and NR3B of glycine and D-serine, which are candidate neurotransmitters for NMDA receptors containing NR3 subunits. The ligand binding domains of both NR3 subunits adopt a similar extent of domain closure as found in the corresponding NR1 complexes, but have a unique loop 1 structure distinct from that in all other glutamate receptor ion channels. Within their ligand binding pockets, NR3A and NR3B have strikingly different hydrogen bonding networks and solvent structures from those found in NR1, and fail to undergo a conformational rearrangement observed in NR1 upon binding the partial agonist ACPC. MD simulations revealed numerous interdomain contacts, which stabilize the agonist-bound closed-cleft conformation, and a novel twisting motion for the loop 1 helix that is unique in NR3 subunits.

Keywords: crystallography, D-serine, glutamate receptor, glycine, molecular dynamics, NMDA

Introduction

Glutamate receptor ion channels (iGluRs), which mediate transmission at excitatory synapses in the brain, are encoded by 18 genes. Based on their ligand binding profile and nucleic acid sequence, these genes can be subdivided into seven families with diverse functional properties. The AMPA, kainate, and NMDA receptor NR2 subtypes bind glutamate, whereas NMDA receptor NR1 and NR3 subtypes and delta subunits bind glycine and D-serine. iGluRs are modular proteins with a common design containing a bilobed ligand binding domain, which is split into two segments S1 and S2 by insertion of the ion channel. The unique ligand binding properties of each subtype are determined by amino-acid substitutions in the S1 and S2 segments. The S1S2 ligand binding domain can be genetically excised (Kuusinen et al, 1995), expressed at high levels as a water-soluble protein (Chen and Gouaux, 1997), and crystallized (Armstrong et al, 1998), allowing structural analysis of the mechanisms underlying the diverse functional properties of a neurotransmitter receptor gene family. Crystallographic studies initially targeted the AMPA (Armstrong et al, 1998; Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000), kainate (Mayer, 2005; Nanao et al, 2005; Naur et al, 2005), NR1 (Furukawa and Gouaux, 2003; Inanobe et al, 2005), NR2 (Furukawa et al, 2005), and delta subtypes (Naur et al, 2007). This revealed that ligands bind in solvent-filled cavities of different size, geometry, and side-chain chemistry. At present, there is no structural information on the ligand binding domain of NR3 subtype NMDA receptors.

NMDA receptors have key roles both in the development of neural circuitry and also in the adult brain where they regulate synaptic plasticity. The NR1 subunit is an obligate member of all NMDA receptor subtypes, but the NR2 and NR3 subunit families show complex changes in expression pattern during development. Thus it is important to understand their ligand selectivity and how this contributes to their biological function. We recently characterized the ligand binding properties of the NR3A subtype, and found that it binds glycine and D-serine with higher affinity than NR1 (Yao and Mayer, 2006). Here we analyse the ligand binding profile of NR3B; report crystal structures for the glycine and D-serine complexes of both NR3A and NR3B; and investigate the structural mechanisms for binding of the NR1 subunit partial agonist ACPC.

Results

Preparation and ligand binding activity of NR3B S1S2

The boundaries and linkers for NR3A and NR3B S1S2 were based on the GluR2 S1S2 construct (Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000). Both constructs were expressed as soluble proteins and purified as described previously (Yao and Mayer, 2006). After removal of the His tag, NR3A S1 spans from Asn511 to Arg660 and S2 from Glu776 to Lys915, with a GT dipeptide connecting S1 and S2; for NR3B, S1 spans from Ala413 to Arg560 and S2 from Glu676 to Lys815; the difference in numbering for NR3A and NR3B results from insertions in the amino-terminal domain in NR3A, which precedes the S1S2 construct. The proteins were purified in the presence of either glycine or L-serine, and for binding assays apo protein was prepared by exhaustive dialysis.

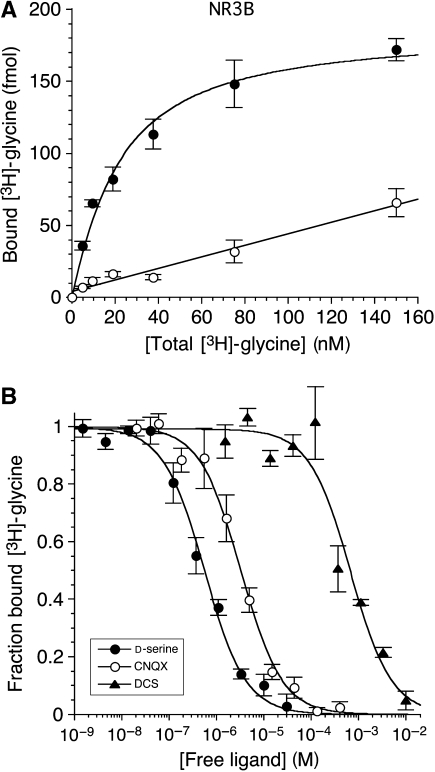

Binding assays for NR3B were performed under identical conditions to those for NR3A (Yao and Mayer, 2006). Glycine binds with high affinity, Kd=16.4±3.6 nM (Figure 1A), 2.5 times lower than the Kd measured for NR3A. Using [3H]glycine displacement assays (Figure 1B), we measured Ki values for the NR3 agonist D-serine, Ki=163±45 nM, and for the NR1 partial agonists D-cycloserine, Ki=176±43 μM, and HA966, Ki=3.54±0.55 mM, all of which bind to NR3A with similar affinity (HA966, Ki=3.50±0.80 mM; for other ligands, see Yao and Mayer, 2006). Thus none of these ligands discriminate between NR3 subtypes. The affinity of NR3B for 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, Ki=0.93±0.09 μM, and 7-chlorokynurenic acid, Ki>100 μM, was nearly identical to values previously measured for NR3A (Yao and Mayer, 2006). This is not surprising, as from crystallographic analysis the ligand binding domains of NR3A and NR3B have almost identical structures.

Figure 1.

Ligand binding properties of NR3B. (A) Saturation assay for [3H]glycine; the open circles indicate nonspecific binding measured in the presence of 100 mM glycine. (B) Displacement assays for D-serine, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), and D-cycloserine (DCS). The measured Kd value for glycine is 16.4 nM; the calculated Kd values for D-serine, CNQX, and DCS are 163±45 nM, 0.93±0.09 μM, and 176±43 μM, respectively; error bars represent mean±s.e.m. from three experiments.

NR3A and NR3B do not assemble as functional dimers

Crystals of NR3A and NR3B complexes with glycine diffract to 1.58 Å resolution (Table I). For both structures, there were two molecules in the asymmetric unit, but in neither case was the packing biologically relevant (Supplementary data). For NR3A, the pair of molecules were packed by means of their back surfaces, but in a head to tail dimer orientation, with a buried surface of 780 Å2 per subunit, whereas for NR3B, a dimer was formed by a face to face assembly in a 69 orientation, with a buried surface of 830 Å2 per subunit. Neither of these arrangements remotely resembles that observed for NR1 homodimers (Inanobe et al, 2005), heterodimer assemblies of NR1 and NR2A (Furukawa et al, 2005), or for AMPA and kainate receptor homodimers trapped in their active conformation by mutations or allosteric modulators (Sun et al, 2002; Jin et al, 2005; Weston et al, 2006b). Although it is premature to speculate that homodimer formation by NR3 subunits does not occur in vivo, the results of functional expression studies indicate that, at a minimum, NR1 must be coexpressed with NR3A or NR3B to generate functional receptors (Chatterton et al, 2002), whereas other studies suggest a requirement for both NR1 and NR2 subunits (Sasaki et al, 2002) or NR1 and both NR3A and NR3B (Smothers and Woodward, 2007). Thus, one interpretation of the crystallographic data, consistent with the results of functional studies and recent biochemical work (Schuler et al, 2008), is that NR3 subunits form heterodimer assemblies with NR1 and possibly with NR2.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data set ligand | NR3A glycine | NR3A D-serine | NR3A ACPC | NR3B glycine | NR3B D-serine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit cell a, b, c (Å) | 49.9, 97.6, 59.9 | 49.8, 97.7, 60 | 49.7, 103.6, 59.8 | 45.9, 83.6, 145.2 | 45.8, 83.5, 145 |

| α, β, γ (deg) | 90, 93.6, 90 | 90, 93.6, 90 | 90, 95, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Number per a.u. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9793 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 30–1.58 (1.64) | 35–1.45 (1.50) | 30–1.96 (2.03) | 40–1.58 (1.64) | 40–1.62 (1.68) |

| Unique observations | 78 213 | 100 689 | 43 239 | 76 724 | 71 657 |

| Mean redundancyb | 3.8 (3.3) | 3.1 (2) | 2.9 (2.7) | 4.5 (4.2) | 4.5 (4.4) |

| Completeness (%)b | 95.9 (75.3) | 96 (72.1) | 97.9 (96.4) | 92.3 (91.4) | 99 (98.5) |

| Rmerge (%)bb,c | 0.054 (0.255) | 0.050 (0.292) | 0.088 (0.362) | 0.048 (0.326) | 0.052 (0.344) |

| I/σ(I)b | 11.7 (5.6) | 14.3 (2.5) | 8.5 (2.6) | 16.6 (3.2) | 14.5 (4) |

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 29.89–1.58 | 34.84–1.45 | 19.91–1.96 | 36.30–1.58 | 35.84–1.62 |

| Protein atoms (alt conf) | 4909 (417) | 4823 (325) | 4663 (139) | 4450 (60) | 4471 (84) |

| Ligand atoms | 10 | 14 | 14 | 10 | 14 |

| Glycerol atoms | 24 | 18 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Cl/Br atoms | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Water atoms | 631 | 633 | 513 | 527 | 475 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%)d | 14.8/17.7 | 15.3/17.8 | 15.6/21.1 | 19.2/23.1 | 19.2/22.8 |

| RMS deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.013 |

| Bond angles (deg) | 1.46 | 1.66 | 1.45 | 1.58 | 1.54 |

| Bonds B-values Mc/Sce | 1.29/1.59 | 1.52/2.01 | 0.86/2.24 | 1.49/1.83 | 1.40/1.74 |

| Angles B-values Mc/Sce | 1.93/2.38 | 2.23/3.02 | 1.38/3.51 | 2.08/2.65 | 1.99/2.47 |

| Mean B-values (Å2) | |||||

| Protein overall | 11.5 | 11.8 | 13.3 | 17.9 | 16.7 |

| Main chain/side chain | 10.4/12.7 | 10.3/13.3 | 12.3/14.3 | 16.6/19.3 | 15.4/18 |

| Ligand | 7.8 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 15.1 | 15.9 |

| Glycerol | 27.3 | 32.1 | — | 29.6 | 29.7 |

| Cl/Br | 25.2 | 32.9 | — | — | — |

| Water | 28 | 30.1 | 28.7 | 33.7 | 33.5 |

| Ramachandran %f | 98.7/0 | 98.7/0 | 98.1/0 | 98.3/0 | 98.3/0 |

| aValues in parentheses indicate the low-resolution limit for the highest resolution shell of data. | |||||

| bValues in parentheses indicate statistics for the highest resolution shell of data. | |||||

| cRmerge= =(Σ∣II−〈II〉∣)/ΣI∣II∣, where 〈II〉 is the mean II over symmetry-equivalent reflections. | |||||

| dRwork=(Σ∣∣Fo∣−∣Fc∣∣)/Σ∣Fo∣, where Fo and Fc denote observed and calculated structure factors, respectively; 5% of the reflections were set aside for the calculation of the Rfree value. | |||||

| eMain chain/side chain. | |||||

| fPreferred/disallowed conformations. | |||||

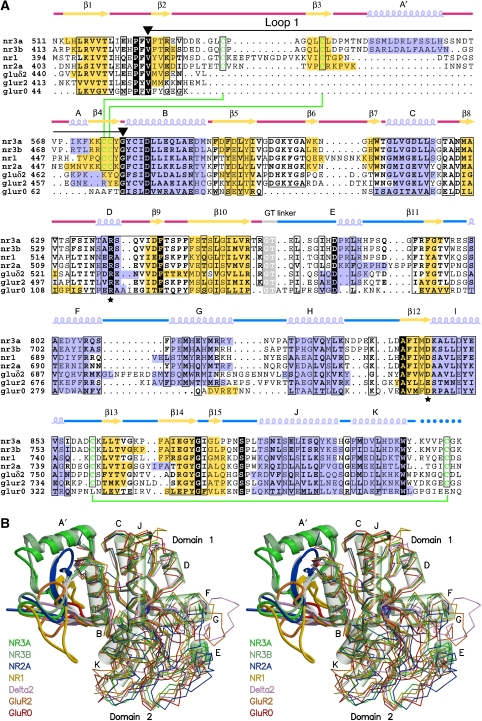

NR3A and NR3B have a unique loop 1 structure

Glutamate receptors share a common fold related to that found in bacterial periplasmic proteins, but emerging from the base of helix B there is an additional substructure, which shows a progressive increase in size and complexity in NMDA receptors. In GluR0, the subdomain is formed by a 13-amino-acid loop that begins and ends in conserved valine and glycine residues (Figure 2A). In the AMPA, kainate and delta receptors loop 1 increases in size, and is formed by a short two-stranded antiparallel β-sheet connected by a loop of 16–18 residues capped by a three-residue helix. In the NMDA receptors, loop 1 increases greatly in size and complexity and reaches its greatest development in NR3A and NR3B.

Figure 2.

NR3A and NR3B share structural homology with other members of the iGluR gene family but have a unique loop 1 structure. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of the S1 and S2 segments for the glycine-bound complexes of NR3A (2RC7), NR3B (2RCA), and NR1 (1PB7), the glutamate-bound complexes of NR2A (2A5S), GluR2 (1FTJ), and GluR0 (1II5), and the D-serine complex of the delta 2 subunit (2V3U), coloured by secondary structure. Drawn above the aligned sequence is the secondary structure of NR3A, with red and blue lines indicating the S1 and S2 peptides; conserved amino acids that interact with the ligand Cα functional groups are indicated by a asterisk; cysteine residues that form disulphide bonds are connected by green lines; a black line flanked by inverted triangles indicates loop 1; dots indicate regions for which no main-chain electron density was observed. (B) Stereo view of the same series of structures superimposed by least squares using domain 1 Cα coordinates. Loop 1 is drawn using a ribbon representation, with the remainder of the structure shown as a Cα trace; for NR3A, α-helices are drawn as transparent cylinders.

The structure of the loop 1 subdomain is distinct in each of the three NMDA receptor gene families (Figure 2B), and is composed of 49 and 42 residues in NR1 and NR2, 53 residues in NR3A, and 51 residues in NR3B. Unique to the loop 1 structure of NR3A and NR3B is a 12- to 13-residue α-helix inserted between β-strands 3 and 4. This A′ helix caps the upper surface of the ligand binding domain in the NR3 subunits. In contrast, in the NR1 and NR2 subunits, the subdomain is composed exclusively of β-strands. When we consider loop 1 as a substructure that has been added to the core present in GluR0, we calculate that it contributes 18% of the total surface area of an NR3 subunit, buries an area of 1600 Å2 on the lateral surface of domain 1, and forms a bisected pyramid of approximate dimensions 21 Å high, 25 Å wide, and 12 Å deep, which projects laterally into the extracellular solution.

In all NMDA receptors, loop 1 contains four Cys residues, which form disulphide bonds linking conserved β-strands 3 and 4. In both the glycine and D-serine complexes, there was clear density for an alternative conformation for the side chain of Cys543 in NR3A, which would preclude formation of a disulphide bridge with Cys576; this was also observed for Cys445 in NR3B, which makes a disulphide bridge with Cys476. In contrast, the density for the adjacent disulphide bond on the opposite side of β-strand 4, formed between Cys537 and Cys575 in NR3A, and the corresponding residues in NR3B, revealed only a single conformation. Similar alternate conformations are observed for Cys454, which forms one of the loop 1 disulphide bonds in the NR1 glycine complex (Furukawa and Gouaux, 2003).

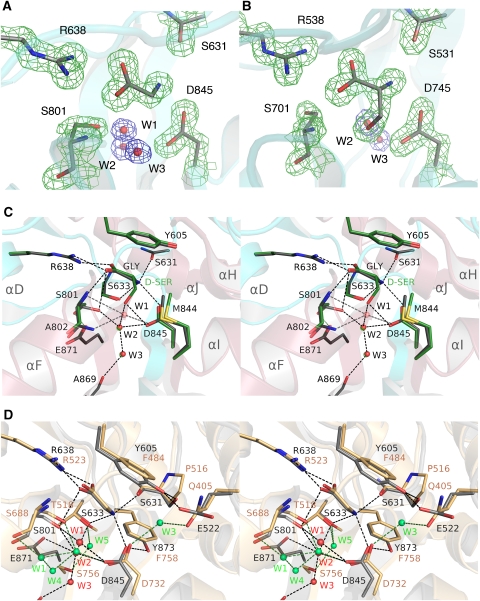

NR3A and NR3B complexes with glycine and D-serine

The NR3A and NR3B ligand binding core crystal structures have the same two-domain Venus fly trap assembly common to other members of the iGluR family (Figure 2B). Glycine and D-serine bind in a cavity formed at the interface of domains 1 and 2. In the glycine complex, the cavity volume is 62 Å3 in NR3A and 63 Å3 in NR3B, comparable with that in the NR1 glycine complex, volume 60 Å3. In the D-serine complexes, there is a small increase in the volume of the ligand binding cavity to 78 Å3 for both NR3A and NR3B; this occurs with a <1° change in domain closure, and results in part from small changes in side-chain dihedral angles.

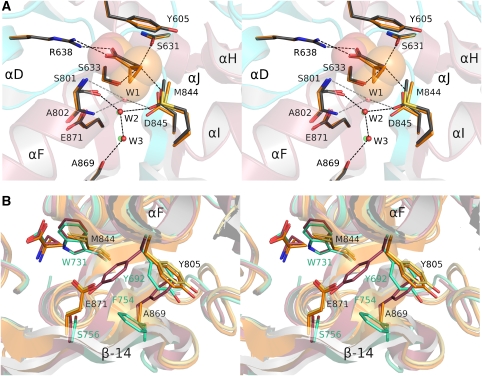

Electron density for glycine, D-serine, solvent atoms, and ligand binding site side chains was unambiguous (Figure 3A and B) and revealed three buried water molecules in the glycine complexes for NR3A and NR3B adjacent to the ligand. These form a hydrogen bond network linking helix F to the interdomain β-strands at the base of the ligand binding cavity. In the NR3A and NR3B D-serine complexes, the ligand OH group displaces W1. Glycine and D-serine stabilize the closed-cleft conformation of the ligand binding domain by forming contacts that link domains 1 and 2. The α-carboxylate makes a salt bridge with helix D in domain 1 by means of the guanidinium group of Arg638 and Arg538 in NR3A and NR3B, respectively. The ligand α-carboxylate group also forms hydrogen bonds with the main-chain amides of Ser633 (Ser533) in domain 1 and Ser801 (Ser701) in domain 2 (Figure 3C). The ligand α-amino group makes a salt bridge with the carboxylate group of Asp845 (745) in domain 2, and forms hydrogen bonds with the main-chain carbonyl oxygen of Ser631 (531) and the side-chain hydroxyl group of Ser633 (533). In the glycine complexes, water molecule W2 links the side chain of Asp845 (745) with the side chain of Ser801 (701), whereas W1 and W3 link the side chain of Asp845 (745) with the main-chain carbonyl oxygen of Ala869 and the side chain of Glu871 (771) in β-strand 14, which connects domain 2 to domain 1. The side chain of Tyr605 caps the binding site and makes important hydrophobic interactions with the ligand C, Cα, and for D-serine Cβ atoms.

Figure 3.

NR3 ligands bind in the cleft between domains 1 and 2. (A) Electron density map (2mFo−DFc contoured at 2σ) for the ligand binding site of the NR3A glycine complex and three water molecules at 1.58 Å resolution. (B) Electron density map (2mFo−DFc contoured at 2σ) for the ligand binding site of the NR3B D-serine complex at 1.62 Å resolution. (C) Stereo view of the NR3A glycine and D-serine complexes superimposed by least squares using domain 1 Cα coordinates; carbon atoms for the ligand and side chains for the glycine and D-serine complexes are shaded grey and green, respectively. (D) Stereo view of the NR3A and NR1 glycine complexes superimposed by least squares using domain 1 Cα coordinates; side chains for NR3A and NR1 are drawn with carbon atoms shaded grey and tan respectively; water molecules in the NR3A and NR1 structures are coloured red and green; dashed lines show hydrogen bonds and are coloured black and green for NR3A and NR1, respectively.

The glycine and D-serine complexes have similar structures, but in the D-serine complex, the ligand OH group forms a direct hydrogen bond contact with the side chain of Asp845 (745) and with W2. In the glycine complex, Ser801 (701) makes hydrogen bond contacts with the ligand α-carboxylate group and with W2, but there is weak electron density for an alternative conformation in which the side chain rotates by 130° (Figure 3A). In the D-serine complex, this alternative conformation is preferred because it relieves a close contact with the ligand, and as a result the D-Ser OH group makes a hydrogen bond contact with the side chain of Glu871. Because the D-serine Cβ atom is in van der Walls contact with Met844 (744), it displaces the side-chain methyl group laterally by 0.6–0.7 Å (Figure 3C); the D-serine OH group also pushes the side-chain carboxyl group of Asp845 (745) downwards by 0.3–0.6 Å. We note that the affinity of D-serine for NR3A and NR3B is 16 and 10 times lower than that for glycine, and thus these small structural changes likely contribute to the 1.5 (1.2) kcal per mole difference in binding energy for glycine and D-serine.

Comparison of glycine binding in the NR3 and NR1 subunits

Using the NR1 complex with the competitive antagonist 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid (5,7-DCKA) as a reference, the extent of domain closure for the glycine-bound complexes of NR3A and NR3B, 22.2° and 23.4° respectively, was similar to the value of 25.4° for the NR1 complex with glycine. Consistent with this, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) for Cα atoms, following least squares superposition on the NR1 glycine complex, excluding loops 1 and 2, was 0.69 Å for NR3A and 0.90 Å for NR3B. When the NR1 glycine complex was used as a reference, the NR3A and NR3B structures were open by only 2 and 3°. Despite the high degree of similarity in their fold, extent of domain closure, and mechanism of ligand binding for the NR3 and NR1 complexes with glycine, the proteins share only 34% amino-acid identity in their ligand binding cores and differ 650-fold in affinity for glycine.

Inspection of the NR3 and NR1 crystal structures reveals numerous differences that contribute to this (Figure 3D). Tyrosine 873 caps the binding site in the NR3 complex and is held in place by hydrogen bonds with the side chains of Ser631 and Glu522. In NR1, all three amino acids differ: Tyr605 is replaced by Phe484, Ser631 by Pro516, and Glu522 by Gln405. As a result, the hydrogen bonds made by these residues are broken in NR1, and associated with this is a 0.9 Å tilt of Phe484 away from the ligand. At the base of the binding site, Glu871 is replaced by Ser756 and Tyr873 by Phe758. As a result of these amino-acid substitutions, there is a substantial change in the network of water molecules that have structural roles in the ligand binding sites. Of five water molecules in the NR1 binding site, only W2 is preserved in the NR3 structures. Loss of hydrogen bonds made by the OH groups of Tyr605 and Tyr873 allows the NR1 Gln405 and Asp732 side chains to rotate by 81 and 43° compared with the corresponding side-chain conformations in the NR3 structures. This rotation creates a binding site for W3 in the NR1 complex. W1, W4, and W5 are also unique to the NR1 complex. Most likely this is in part due to replacement of Glu871 by Ser756 and Ser633 by Thr518, which creates different hydrogen bond networks in the NR3 and NR1 ligand binding sites (Figure 3D). A superposition of NR3A, NR3B, NR1, and delta 2, the four subunits that bind glycine and D-serine, on the ligand binding domain of the NR2A subunit, which binds glutamate, gives an insight into the basis of ligand selectivity in these families (Supplementary data). The binding site Arg and Asp residues are conserved in all five subunits. Selectivity for glycine and D-serine over glutamate occurs as a result of two factors. The first is steric occlusion resulting from replacement of Tyr730 by either a methionine in NR3A and NR3B, or a tryptophan in NR1 and delta 2. The second is loss of a binding site for the glutamate ligand γ-COOH group, owing to replacement of Thr690 by an alanine in NR3 or a valine in NR1 and delta 2. The low affinity of delta 2 for D-serine cannot result from amino-acid substitutions in the ligand binding pocket per se, because all contacts are preserved in this series of structures; as a result, the lower affinity likely reflects differences in interdomain contacts in the active conformations of NR1 and NR3 versus delta 2.

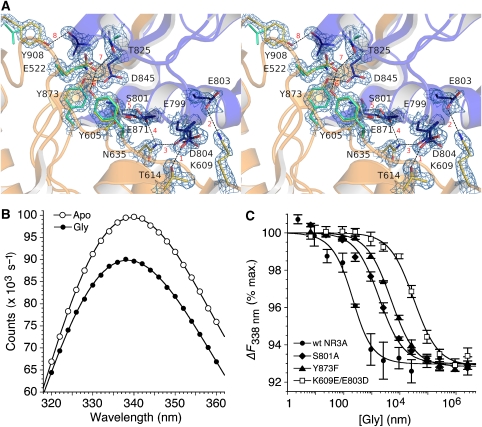

Interdomain interactions regulate affinity for glycine

In glutamate receptors and periplasmic binding proteins, the stability of the ligand-bound closed-cleft conformation is determined by two mechanisms. The first is binding energy contributed by the ligand and the second is formation of interdomain contacts specific to the closed-cleft conformation (Robert et al, 2005; Weston et al, 2006a; Zhang et al, 2008). By comparing the NR3A crystal structures of agonist complexes with a model apo state generated by least squares superpositions of domains 1 and 2 on the NR1 5,7-DCKA complex, we identified eight sites with interdomain contacts specific to the glycine-bound conformation of NR3A (Figure 4A). These are distributed widely over the interfacial surfaces of domains 1 and 2. Because electron density is of good quality for all of the side chains that mediate these contacts, we are confident that they are functionally significant. This was verified both by site-directed mutagenesis and by replica exchange molecular dynamics (MD). The large majority of these contacts are formed by amino acids that do not directly participate in the binding of glycine.

Figure 4.

Interdomain interactions stabilize the closed-cleft conformation of NR3A. (A) Stereo view of the NR3A glycine complex with domains 1 and 2 coloured gold and blue, respectively. The electron density map (2mFo−DFc contoured at 2σ) reveals interdomain hydrogen bonds and salt bridges at eight sites, which are individually numbered in red. Several of these contacts are absent in NR1, owing to replacement of Tyr side chains by Phe and Val; these are coloured pale green for the NR1 glycine crystal structure (1PB7). (B) Quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence for the NR3A Glu871S mutant following the addition of 300 μM glycine (≈100 × Kd). (C) Fluorescence quenching curves measured at 338 nm, with excitation at 282 nm, for wild-type NR3A and the NR3A S801A, Y873F, and K609E/E803D mutants; data points show mean and s.e.m. of three experiments.

Site 1 links helices C and F by means of a hydrogen bond between the hydroxyl group of Thr614 and the carboxylate of Glu799. The mutation T614A produced a >5 × 10−4 reduction in affinity for glycine measured by quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (Figure 4B and Table II), indicating that the N-terminal region of helix F is crucial in stabilizing the closed state of the NR3A ligand binding domain. Site 2 links loop 2 and helix F by a salt bridge between the side chains of Lys609 and Glu803. The side chain of Glu803 has an alternative conformation in which this connection is broken. The weak strength of this contact is indicated by the 2.5-fold increase in Kd for the E803A mutant. There is also an alternative conformation for Asp804, which forms site 3 linking helix F with the N terminus of helix D by a hydrogen bond with the side chain of Asn635. The mutation N635S, which introduces the NR1 side chain at this site, produces a six-fold increase in Kd. Sites 4 and 5 are formed by hydrogen bonds between the OH group of Ser801 and the side-chain amide of Asn635, and the OH groups of Ser801 and Ser633. The S801A mutant produces a 10-fold increase in Kd for glycine (Figure 4C), but because Ser801 also forms hydrogen bond contacts with glycine and with Glu871, interpretation of the origin of this effect is ambiguous. Site 6 is unique to NR3 subunits and is formed by a hydrogen bond between the hydroxyl group of Tyr873 and the carboxylate of Asp845. The Y873F mutation produces a 25-fold increase in Kd (Figure 4C). Site 7 is also unique to NR3 subunits and is formed by a hydrogen bond between the hydroxyl group of Thr825 and the carboxylate group of Glu522; the T825A and Y605F mutants produce >7- and 10-fold increases in Kd for glycine. Site 8 is another NR3-specific contact due to replacement of Tyr908 by valine in NR1, and is formed by a hydrogen bond linking the Tyr908 hydroxyl group at the base of helix K with the main-chain carbonyl oxygen of Ala847 in helix I. We were unable to measure Kd for the Y908F mutant because glycine produced <1% change in tryptophan fluorescence.

Table 2.

Estimated occupancy of interdomain contacts at 310 K based on WHAM analysis of replica exchange MD trajectories

| Residues | Site | Gly frequency | ACPC frequency | Mutant | Kd(mut)/Kd(wt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T614-E799 | (1) | 0.812 | 0.821 | T614A | >5 × 104 |

| K609-E803 | (2) | 0.423 | 0.079 | E803A | 2.5 |

| N635-D804 | (3) | 0.058 | 0.061 | N635S | 5.6 |

| N635-S801 | (4) | 0.833 | 0.661 | N635S | 5.6 |

| S801-E871 | (5a) | 0.012 | 0.011 | S801A | 9.7 |

| S633-S801 | (5b) | 0.005 | 0.038 | S801A | 9.7 |

| D845-Y873 | (6) | 0.944 | 0.998 | Y873F | 25 |

| E522-T825 | (7a) | 0.837 | 0.957 | T825A | 7.3 |

| E522-T825 | (7b) | 0.691 | 0.870 | Y605F | 10.1 |

| A847-Y908 | (8) | 0.570 | 0.655 | ND | ND |

| Numbers in parentheses refer to the labelling in Figure 4. |

Mechanism of binding of ACPC

ACPC is a carbocyclic derivative of glycine that has been used as a probe of gating mechanisms in the NR1 subtype of glutamate receptor (Inanobe et al, 2005). The NR3A ACPC complex was solved at 1.96 Å resolution. The conformations of the NR3A ACPC and glycine complexes are similar with an RMSD for Cα atoms of 0.35 Å, but the binding pocket expands to a volume of 82 Å3 to accommodate the larger ACPC ligand. Expansion of the ligand binding cavity is due, in part, to a small opening of the ligand binding core cleft, by 1.5°, and also because of small shifts in side-chain conformation (Figure 5A). Similar to the NR3A D-serine complex, ACPC displaces water molecule W1, but because the cyclopropyl group is hydrophobic it cannot contribute to the hydrogen bond network formed by the interaction of the D-serine OH group with W2 and the side chain of Asp845. Steric hindrance by the cyclopropyl group causes a 0.9 Å downwards displacement of the side-chain carboxyl group of Asp845 and a 0.4 Å backwards displacement of the side-chain methyl group of Met844 (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Mechanism of binding of ACPC. (A) NR3A complexes with ACPC and glycine superimposed by least squares using domain 1 Cα coordinates; carbon atoms for ligands, and side chains for the ACPC and glycine complexes are shaded orange and grey, respectively; the ACPC ligand is shown as transparent CPK spheres; water molecules for the ACPC and glycine complexes are drawn in green and red, respectively. (B) Superpositions of the NR3A glycine (yellow) and ACPC (orange) and NR1 glycine (green) and ACPC (magenta) complexes reveal that, in contrast to the strikingly different conformations observed in the NR1 complexes, there is no ligand-dependent conformational switch in helix F and β-strand 14 for the NR3A complexes; side-chain labels are coloured black for NR3A and green for NR1.

The similarity in the structures of the NR3A glycine and ACPC complexes is in contrast with the large differences observed in the corresponding NR1 complexes (Figure 5B), for which side chains in β-strand 14 and helix F undergo a concerted transition to accommodate the binding of ACPC (Inanobe et al, 2005). This does not happen in the NR3A ACPC complex as a result of amino-acid substitutions at key positions in β-strand 14. The substitution of Glu871 for Ser756 introduces a steric barrier, which prevents Tyr805 from flipping to the conformation found in the NR1 ACPC complex. In NR1 the side chain of Phe754 also flips position in the ACPC complex, but in NR3A this is replaced by an Ala residue. Linked with these side-chain flips, there is a substantial movement of β-strand 14 in the NR1 complex, which following superposition of domain 1 for the glycine and ACPC complexes has an RMSD for main-chain atoms of 1.9 Å for residues Thr748 to Ser756 in NR1, versus only 0.4 Å for the corresponding residues in NR3A. Thus, despite their similar structures, NR1 and NR3A show different rearrangements in their ACPC complexes compared with the corresponding glycine-bound structures, which might differentially affect their efficacy as agonists.

Binding site interactions in replica exchange MD

To establish dynamic models for the NR3A complexes with glycine and ACPC, we performed a series of 650 ns replica exchange MD simulations. All of the ligand interactions observed in the crystal structures, including salt bridges with Asp845 and Arg638, and hydrogen bonds with residues Ser631, Ser633, and S801, proved to be stable in replica exchange trajectories for both ligands, with the exception of the salt bridge between Asp845 and the amino group of glycine, which forms approximately 78% of the time for the glycine-bound complex but more than 99% of the time for ACPC. When this interaction was not formed, it was replaced by a water-mediated contact. This exchange between a salt bridge and a water-mediated contact indicates that the interaction of Asp845 with glycine is the most transient and presumably weakest of the binding site interactions in the agonist-bound complex.

In close agreement with the crystal structures, the side-chain methyl group of M844 is displaced on average 0.4 Å further from the ligand Cα in the case of ACPC versus glycine. The separation between the aromatic ring of Tyr605 and Cα atom of ACPC also increases, by 0.9 Å; this exceeds the 0.4 Å movement observed in the crystal structures. Surprisingly, the presence of ACPC reduces conformational flexibility of the binding site, as indicated by average root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values of 1.13 Å for glycine and 0.91 Å for ACPC for side chains within 5 Å of the ligand. In the glycine-bound case, the side-chain mobility was 10% higher for residues in D2 compared with residues in D1. In contrast, the average mobilities of binding site side chains were identical between D1 and D2 in the ACPC-bound state. The difference likely indicates a greater loss of conformational entropy upon binding ACPC versus glycine. Consistent with the crystal structures, no major conformational change was observed for Y805 whereas Glu871 was rotated outwards, so that its acid group was exposed to solvent, but the side chain still blocks some of the volume that would be occupied if Y805 were to rotate to an NR1-ACPC-like state.

Three sites around the glycine ligand, occupied by crystallographic water molecules in the glycine-bound crystal structure, are also hydrated in the replica exchange MD simulations. Sites W1, W2, and W3 are occupied by water molecules for >80% of the time for the glycine-bound complex. In contrast, W2 and W3 are occupied only 76 and 60% of the time for the ACPC-bound complex. With the exception of W1, the bound water molecules exchange freely with bulk water during the simulations. One additional water molecule, positioned near the ligand amine and D845, appears only in the glycine trajectories; this site is occupied only 34% of the time, but in many of those time steps mediates the interaction between Asp845 and the ligand amine. The buried water molecules were placed initially using DOWSER (Zhang and Hermans, 1996); it is thus remarkable that water molecules positions close to the crystallographic sites were highly occupied throughout the 650 ns MD trajectories. This agreement is not limited to W1–W3, but also extends to other nearby buried crystal water molecules such as a cluster near Arg638 distal to the ligand.

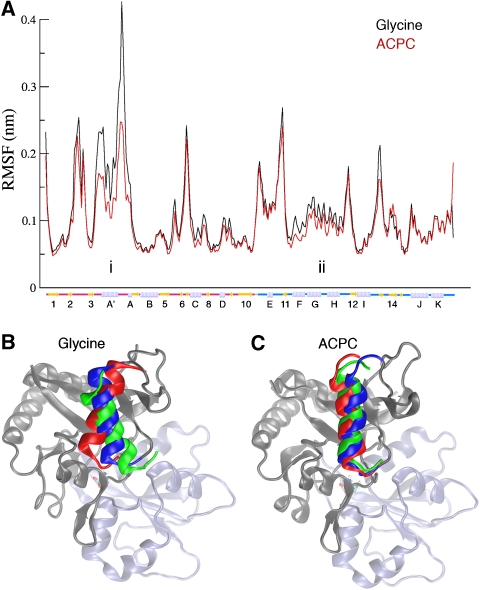

Conformational dynamics of glycine- and ACPC-bound NR3A

The backbone mobilities of residues in the glycine and ACPC complexes are quite similar, as shown in the RMSF plot of Cα atoms (Figure 6A). However, in two regions of the glycine complex, mobility was significantly higher than that in the ACPC complex. Because these RMSFs are calculated from raw replica exchange trajectories, they are not directly comparable with RMSFs from canonical ensemble MD simulations, but still offer insight into the relative mobility of different regions of the protein. The first of these regions involves helix A′. Throughout the 35° range of rotation observed in simulations with glycine, interactions between the hydrophobic face of helix A′ and a neighbouring hydrophobic patch formed by the β1, β3, and β5 strands are maintained; however, the R516–D555 salt bridge must break for the rotation of helix A' to reach its full counterclockwise extent. This salt bridge is also generally less stable in the glycine-bound state, and is formed 59.3% of the time with glycine bound and 78.0% of the time with ACPC bound. It should be noted that the β-sheet interacting with the A' helix also interacts with the ligand through β8 and the β5–β6 loop, suggesting a possible mechanism for small changes in the binding site to propagate to this helix, and vice versa. The second region includes helices F, G, and H in domain 2 near the binding site, which interact with the ligand through backbone hydrogen bonds and which appear to have lower entropy in the ACPC complex.

Figure 6.

Mobility of NR3A glycine and ACPC complexes from replica exchange MD simulations. (A) Plot of the Cα-RMSF by residue for concatenations of all replica exchange trajectories in the glycine-bound (black) and ACPC-bound (red) states. Two regions showing notable differences between the states are labelled. (B) Average conformations for the top three clusters in glycine- (B) and ACPC- (C) bound replica exchange simulations illustrating the range of motion of the A′ helix. Colouring runs from blue to red for clusters 1–3. D1 is shown in grey and D2 in light blue.

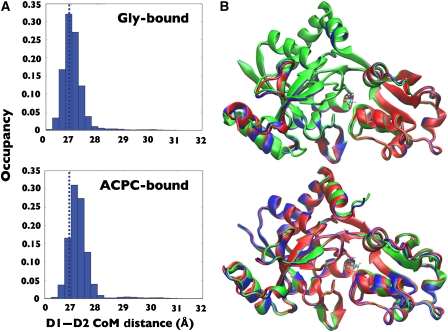

Conformations observed during simulations of both glycine- and ACPC-bound NR3A were clustered using the gromos clustering method. In each case, the peak of the pairwise frame–frame Cα RMSD distribution was used as a clustering cutoff. The three most populated clusters for the glycine- and ACPC-bound complexes, which were observed to readily interconvert, varied in extent of domain opening relative to the glycine complex crystal structure, by 2.3–6.2° for the glycine cluster and by 2.7–7.9° for the ACPC cluster; the top three clusters in each state are shown in Figure 7, along with a histogram of the interdomain distances for the simulation. These clusters account for 90.5 and 93.5% of the total conformations from simulations of the glycine and ACPC complexes, respectively (with cluster 1 itself occupied for 78.5 and 84.2% of time steps). The lower occupancy clusters in both cases are a mixture of states with extent of domain closure similar to the high-occupancy cluster. Only a few rare events were seen where the cleft partially opened, due to loss of the ligand–Asp845 salt bridge.

Figure 7.

Analysis of conformational distributions reveals limited domain opening movements for glycine and ACPC complexes. (A) Histograms of the centre of mass distance between D1 and D2 for the glycine- and ACPC-bound states; data are taken for all saved MD frames. Dashed lines indicate the centre of mass for the crystal structures. (B) Average conformations for the top three clusters (blue, green, and red, respectively) from clustering analysis of the replica exchange trajectories.

The degree of cleft opening is higher in the ACPC-bound state than in the glycine-bound state (Figure 7). Indeed, both the glycine- and ACPC-bound replica exchange structures show slightly more hinge opening than the crystal structures, which exhibit interdomain distances of 26.8 Å in both cases. No significant temperature dependence was observed in either interdomain distance or conformational cluster occupancy. The slightly increased opening in the MD simulations as compared with the crystal structure may be due to lattice packing effects that favour the more closed conformation. However, the ≈0.5 Å difference between the interdomain distances of the crystal structures and the MD simulations is not enough to alter the interdomain contacts that are formed. As shown in Table II, the higher average opening of the ACPC structure may, however, be related to the lower population of some contacts in the ACPC-bound state.

Stability of interdomain contacts in MD trajectories

Interactions between D1 and D2 identified in the crystal structures of the liganded complexes were shown by site-directed mutagenesis to have a key role in stabilizing the closed-cleft state of the receptor. To identify additional interactions that stabilize the closed-cleft state, independently of the model used to design NR3A mutants, replica exchange simulations were performed for a ligand-free state starting from the conformation of the glycine-bound crystal structure. Analysis of interdomain interactions was then performed on all resulting conformations where the centre of mass distance between D1 and D2 was greater than 30 Å. In these ‘open' conformations, all of the interdomain contacts observed in the crystal structures and MD simulations of ligand-bound NR3A S1S2 are broken, except for the Glu522–Tyr605 hydrogen bond, which is formed in 19.2% of the open conformations, the Asp845–Tyr893 hydrogen bond, formed in 13.7% of the open conformations, and the Lys609–Glu803 salt bridge, present in 9.6% of the open conformations.

Analysis of the glycine- and ACPC-bound replica exchange trajectories indicates that most interdomain interactions present in the crystal structure are stable during replica exchange MD; however, a few significant differences merit discussion. Ser801 is observed to deviate from the most populated rotamer found in the glycine complex crystal structure, and in both the glycine- and ACPC-bound MD simulations, the serine side chain rotates to form a hydrogen bond with Asn635. The differing behaviour of Asn635 and Ser801 in MD simulations likely explains why mutations of these residues cause decreases in binding affinity for glycine, even though interactions 3 and 5 (see Table II) are not heavily populated. The system of salt bridges involving Glu799 and Glu803 also differs from the crystal structure. Glu803 interacts with Lys609 42% of the time in the glycine-bound complex, but the frequency of this interaction drops sharply in the ACPC-bound complex to 8%. The interaction between Asn635 and Ser801 is also more stable in the glycine-bound complex, 83.3 versus 66.1%. The partial loss of these interactions for ACPC may stem from the slightly more open conformation, and combined with the loss of W1, and the greater decrease of entropy upon binding, likely contribute to the experimentally observed difference between the two ligands' binding constants. Thus, multiple lines of evidence indicate that multiple interdomain contacts have a role, along with interactions with the ligand, in stabilizing the closed, ligand-bound states of the receptor.

Discussion

NMDA receptors are heteromeric assemblies assembled from NR1, NR2, and NR3 subunits, but with poorly defined stoichiometry. Recent structural work on NR1 and NR2 suggests that the major species of NMDA receptor in the adult CNS is likely to be assembled as a dimer of dimers, in which each dimer contains both NR1 and NR2 subunits. The two NR3 subunits, of which NR3A is expressed widely in the CNS during early development (Wong et al, 2002), whereas NR3B is enriched in motor neuron populations in the adult (Nishi et al, 2001; Fukaya et al, 2005), add to this complexity. At present, there is no consensus whether in vivo there exists NMDA receptors containing only NR1 and NR3 subunits, or whether coexpression with both NR1 and NR2 is required for assembly of functional NMDA receptors containing NR3 subunits. Even experiments with heterologous expression systems give conflicting answers about whether functional NMDA receptors containing NR3 subunits require the presence of both NR3A and NR3B (Smothers and Woodward, 2007), or just a single NR3 subunit species coexpressed with NR1 (Chatterton et al, 2002), and whether NR2 subunits are obligatory (Das et al, 1998; Perez-Otano et al, 2001; Sasaki et al, 2002). Because in heterologous expression systems, NMDA receptors, which lack NR2 subunits, give rise to novel glycine and D-serine activated excitatory ligand gated ion channels (Chatterton et al, 2002; Smothers and Woodward, 2007), this remains an important issue to resolve. By elucidating the binding properties and molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction of glycine and D-serine with NR3A and NR3B, we sought to establish a framework for further structure-based analysis of NR3 subunit function, with the long-term goal of facilitating development of subtype selective ligands, and an understanding of mechanisms that regulate subunit coassembly in native NMDA receptors.

Ligand affinity, selectivity, and interdomain contacts in glutamate receptors

Our binding studies reveal a strikingly different selectivity profile for NR3 subunits versus NR1. The crystal structures we report here give some insight into the underlying mechanisms, but raise many interesting questions. The structures of the NR3A and NR3B glycine and D-serine complexes are identical within the ligand binding site, and for residues within 5 Å, with the exception of the substitution of Ala847 by Ser747 in NR3B, which makes a hydrogen bond with Tyr773 linking helix I with the interdomain β-strand connecting domain 2 with domain 1. As a result, it is not surprising that ligand affinities for NR3A and NR3B differ less than four-fold, and the design of selective antagonists that discriminate between NR3A and NR3B will necessarily require the design of ligands that extend outside of the ligand binding pocket proper.

The replacement of Trp731 in NR1 by a methionine side chain in NR3A and NR3B removes a key interaction with the 5-halogen atom of the competitive antagonist 5,7-DCKA that occurs in the NR1 subunit. The removal of this contact is consistent with the similar affinity of 5-DCKA and 5,7-DCKA for NR3A (Yao and Mayer, 2006). Another crucial NR3A substitution that could explain why the parent compound, kynurenic acid, binds with 280-fold higher affinity to NR1 than NR3A is the replacement of valine by the larger leucine side chain at residue 848, which forms a part of the binding pocket for 5,7-DCKA in NR1. This extension reduces the distance to the 6-position methyl group of 5,7-DCKA from 3.9 to 3.1 Å. In earlier studies, introduction of a Cl atom or an amine group at position 6 for kynurenic acid derivatives led to a reduction in affinity for NR1 (McNamara et al, 1990), indicating limited space between kynurenic acid and the NR1 V735 side chain.

The 650-fold higher affinity of NR3A for glycine measured using radiolabel binding assays cannot be explained by differences in ligand interactions, because glycine binds to identical residues in the NR1 and NR3 subunits. Our analysis of interdomain contacts suggests that high affinity of NR3 for glycine instead arises from stabilization of the closed-cleft conformation by numerous protein–protein contacts between domains 1 and 2. In contrast, for D-serine, there is a 16-fold reduction in affinity for NR3A, whereas for NR1 D-serine binds with approximately four-fold higher affinity than glycine. Crystal structures reveal that for NR3A D-serine makes one additional hydrogen bond contact with the side chain of Asp845, but breaks the solvent-mediated hydrogen bond network made by a structural water molecule (W1), while for NR1 D-serine makes three additional hydrogen bonds with the ligand binding domain. These differences must contribute to the different affinities of NR1 and NR3 for glycine and D-serine.

NR3A stability and dynamics

The MD simulations performed in this study identified structural and dynamic differences between the glycine- and ACPC-bound states. Replica exchange simulations are especially useful for both tasks because the method allows rapid exploration of accessible phase space while accurately predicting thermodynamic quantities. In contrast, alchemical free energy perturbation calculations provide direct estimates of the free energy of binding, but for ligands with nearly identical binding site structures little new information beyond the binding energy is learned. It is notable that in contrast to observations of Biggin and co-workers in the case of NR1, the binding orientation of both glycine and ACPC does not significantly deviate from their initial positions throughout the 650 ns replica exchange simulations. This is interesting, as in the case of NR1, equilibrium simulations appear to suggest substantial mobility of the ligand within the binding site, which could contribute to the low affinity of NR1 for glycine.

In rare open-cleft structures obtained during MD simulations of complexes with ACPC or glycine, the majority of interdomain contacts observed from the analysis of the crystal structures are lost, suggesting that these interactions stabilize the closed-cleft ligand-bound state. Despite the similarity of the ACPC- and glycine-bound NR3A crystal structures, MD simulations revealed three key differences between the protein–ligand complexes in that the ACPC-bound complex is slightly more open, has a more rigid binding site, and has a few weakened interdomain contacts as compared with the glycine-bound complex, all of which likely contribute to its lower binding affinity. The more rigid binding site in the ACPC-bound complex is a novel finding and is in contrast to results of earlier studies on NR1 and GluR2 by Biggin and co-workers (Arinaminpathy et al, 2006; Kaye et al, 2006) and on NR2 (Erreger et al, 2005), who found that the ligand binding domain is more flexible when bound by partial agonists. In contrast, when ACPC binds to NR3A, residues in D2 are forced into less flexible, more sterically constrained interactions, with one less water molecule and its additional degrees of freedom. It is interesting that water molecules in the binding site of the NR3A glycine and ACPC complexes undergo exchange with bulk water molecules; however, no significant difference in the rate of exchange was observed for glycine- and ACPC-bound systems. In contrast, in simulations for NR1, water exchange in the case of ACPC and other partial agonists was more frequent than for glycine. It should be noted that NR1 contains a larger number of water molecules in the binding site, and that these bind to different sites than those in NR3A and NR3B. Not only does this increase in the number of water molecules raise the probability of an exchange event occurring, but more importantly these additional water molecules increase the entropy of the NR1 binding site as compared with that of NR3A. This difference in entropy because of the presence of additional water molecules may also be related to differences observed in the dynamics of bound ligand in NR1 and NR3A where the ligand is observed to sample various binding orientations in NR1.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

Identical to the NR3A S1S2 construct (Yao and Mayer, 2006), NR3B S1S2 was created by inserting a His tag and thrombin cleavage site upstream of the ligand binding domain, with S1 and S2 connected by a GT dipeptide linker; the S1 segment spans from Ala413 to Arg560 and the S2 segment from Glu676 to Lys815. Both NR3A and NR3B were expressed as soluble proteins in OrigamiB (DE3) Escherichia coli (Novagen) using the T7 expression vector pET22b(+) as described previously (Yao and Mayer, 2006). After cleavage of the His tag, the constructs contain a vector-encoded N-terminal Gly–Ser dipeptide. ESI mass spectrum analysis gave molecular weights of 32 895 and 32 135 Da for NR3A and NR3B, consistent with the predicted values of 32 899 and 32 141. The purified NR3A and NR3B S1S2 constructs were monomeric at concentrations of up to 6 mg/ml for NR3A and 1.4 mg/ml for NR3B, as judged by size-exclusion chromatography and by dynamic light scattering.

Fluorescence titration measurements

NR3AS1S2 wild-type and mutant proteins were dialysed at 4°C against ligand binding buffer containing 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 10% glycerol, for a total of five changes, each at a volume ratio of 1:1000. Protein concentrations were determined by UV absorbance at 280 nm. Measurements of Kd values were carried out at 4°C by fluorescence titration spectroscopy (Jobin Yvon-Horiba; Fluoromax-3) using established methods (Abele et al, 2000; Armstrong et al, 2003). For further details, see Supplementary data.

Crystallization of NR3A and NR3B S1S2

For crystallization, ligands were added to 1 mM for glycine, D-serine, and ACPC; numerous attempts were made to obtain crystals with ACBC, but without success. Crystals were grown in hanging drops at 20°C by mixing the protein–ligand complex, at a concentration of 5–10 mg/ml for NR3A and 1–2 mg/ml for NR3B, with reservoir solution at a 1:1 volume ratio, followed by seeding within 1 day after drops were set up. The reservoir solution contained 0.1 M NaBr, 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.2, and 4% PEG4000 for NR3A glycine; 0.12 M NaSCN, 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5.3, 0.01 M EDTA, and 11% PEG3350 for NR3A D-serine; 0.2 M magnesium acetate, 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5.7, and 14% PEG3350 for NR3A ACPC; and 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 6.2, and 17% PEG4000 for NR3B glycine and D-serine.

Crystallographic analysis

X-ray diffraction data sets were collected at beamline ID22 at the Advanced Photon Source and processed using HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). The NR3A glycine complex structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER (McCoy et al, 2007) and the NR1 glycine complex (PDB 1PB7) as a search probe in which the NR1 sequence was replaced by a polyalanine peptide, and loops 1 and 2 were deleted from the model. An initial model containing 267 residues in subunit 1 and 239 residues in subunit 2 was built automatically by ARP/wARP (Morris et al, 2003). The model was rebuilt manually, initially using O (Jones and Kjeldgaard, 1997) and subsequently COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004), coupled with cycles of crystallographic restrained refinement using REFMAC (Winn et al, 2001) with four TLS groups per subunit identified by TLSMD (Painter and Merritt, 2006). The final model was assessed using SFCHECK (Vaguine et al, 1999), tools in COOT, and with MOLPROBITY (Lovell et al, 2003). The NR3A D-serine complex was solved by difference Fourier analysis, using the NR3A model stripped of ligand, solvent, and alternative conformations as a starting model. The NR3A ACPC complex was solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP (Vagin and Isupov, 2001) with chain A of the NR3A glycine complex used as a search probe. The NR3B D-serine complex was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER, with chain A of the NR3A glycine complex used as a search probe, followed by automatic rebuilding using ARP/wARP. The NR3B glycine complex was solved by difference Fourier analysis, using the NR3B D-serine model stripped of ligand, solvent, and alternative conformations as a starting model. Volume calculations were performed with VOIDOO (Kleywegt, 1994); domain closure was calculated with FIT written by Guoguang Lu as described previously (Mayer et al, 2001).

Protein Data Bank accession codes

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the PDB with the following accession codes: NR3A glycine (2RC7), NR3A D-serine (2RC8), NR3A ACPC (2RC9), NR3B glycine (2RCA), and NR3B D-serine (2RCB).

Molecular dynamics

MD simulations were performed with NAMD 2.6 (Phillips et al, 2005). The CHARMM22 forcefield (MacKerell et al, 1998) with CMAP corrections (Mackerell et al, 2004) was used, with parameters for the ACPC cyclopropane ring taken from CHARMM22 stream files. Each system was equilibrated for 100 ps with the protein backbone constrained to its starting coordinates, and 150 ps with no constraints; 1000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization were performed before each equilibration run. Replica exchange simulations (Sugita and Okamoto, 1999) were performed using 65 replicas, with exchanges attempted once per 5 ps. The replicas spanned temperatures ranging from 310 to 400 K and were assigned by performing a cubic fit on the energies of the glycine-bound system in equilibrium simulations at 300, 325, 350, 375, and 400 K, and iteratively assigning temperatures to yield an estimated acceptance ratio of 0.15. Each production run involved 10 ns of simulation per replica, yielding an aggregate trajectory length of 650 ns for each state. For further details, see Supplementary data.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs S Lipton and D Zhang for the gift of NR3A and NR3B cDNAs. Synchrotron diffraction data were collected at Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) 22-ID beamline at APS, Argonne National Laboratory. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. W-31-109-Eng-38. This work was supported by the intramural research programme of NICHD, NIH, DHHS (MLM); the Resource for Macromolecular Modeling and Bioinformatics (NIH P41 RR05969); and Mechanisms of Membrane Biological Systems (NIH 1 R01 GM067887). Computational support was provided by Simulations of Supramolecular Biological Systems (NRAC MCA93S028) and the Turing cluster maintained and operated by the Computational Science and Engineering Program at the University of Illinois.

References

- Abele R, Keinanen K, Madden DR (2000) Agonist-induced isomerization in a glutamate receptor ligand-binding domain. A kinetic and mutagenetic analysis. J Biol Chem 275: 21355–21363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arinaminpathy Y, Sansom MS, Biggin PC (2006) Binding site flexibility: molecular simulation of partial and full agonists with a glutamate receptor. Mol Pharmacol 69: 5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong N, Gouaux E (2000) Mechanisms for activation and antagonism of an AMPA-sensitive glutamate receptor: crystal structures of the GluR2 ligand binding core. Neuron 28: 165–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong N, Mayer M, Gouaux E (2003) Tuning activation of the AMPA-sensitive GluR2 ion channel by genetic adjustment of agonist-induced conformational changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 5736–5741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong N, Sun Y, Chen GQ, Gouaux E (1998) Structure of a glutamate-receptor ligand-binding core in complex with kainate. Nature 395: 913–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterton JE, Awobuluyi M, Premkumar LS, Takahashi H, Talantova M, Shin Y, Cui J, Tu S, Sevarino KA, Nakanishi N, Tong G, Lipton SA, Zhang D (2002) Excitatory glycine receptors containing the NR3 family of NMDA receptor subunits. Nature 415: 793–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GQ, Gouaux E (1997) Overexpression of a glutamate receptor (GluR2) ligand binding domain in Escherichia coli: application of a novel protein folding screen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 13431–13436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Sasaki YF, Rothe T, Premkumar LS, Takasu M, Crandall JE, Dikkes P, Conner DA, Rayudu PV, Cheung W, Chen HS, Lipton SA, Nakanishi N (1998) Increased NMDA current and spine density in mice lacking the NMDA receptor subunit NR3A. Nature 393: 377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60: 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erreger K, Geballe MT, Dravid SM, Snyder JP, Wyllie DJ, Traynelis SF (2005) Mechanism of partial agonism at NMDA receptors for a conformationally restricted glutamate analog. J Neurosci 25: 7858–7866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukaya M, Hayashi Y, Watanabe M (2005) NR2 to NR3B subunit switchover of NMDA receptors in early postnatal motoneurons. Eur J Neurosci 21: 1432–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H, Gouaux E (2003) Mechanisms of activation, inhibition and specificity: crystal structures of NR1 ligand-binding core. EMBO J 22: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H, Singh SK, Mancusso R, Gouaux E (2005) Subunit arrangement and function in NMDA receptors. Nature 438: 185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inanobe A, Furukawa H, Gouaux E (2005) Mechanism of partial agonist action at the NR1 subunit of NMDA receptors. Neuron 47: 71–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, Clark S, Weeks AM, Dudman JT, Gouaux E, Partin KM (2005) Mechanism of positive allosteric modulators acting on AMPA receptors. J Neurosci 25: 9027–9036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Kjeldgaard M (1997) Electron-density map interpretation. Methods Enzymol 277: 173–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye SL, Sansom MS, Biggin PC (2006) Molecular dynamics simulations of the ligand-binding domain of an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem 281: 12736–12742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt GJ (1994) Detection, delineation, measurement and display of cavities in macromolecular structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 50: 178–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuusinen A, Arvola M, Keinanen K (1995) Molecular dissection of the agonist binding site of an AMPA receptor. EMBO J 14: 6327–6332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB III, de Bakker PI, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC (2003) Structure validation by Calpha geometry: phi,psi and Cbeta deviation. Proteins 50: 437–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKerell AD, Brooks B, Brooks CL III, Nilsson L, Roux B, Won Y, Karplus M (1998) CHARMM: the energy function and its parameterization with an overview of the program. In The Encyclopedia of Computational Chemistry, pp 271–277. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons [Google Scholar]

- Mackerell AD Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL III (2004) Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem 25: 1400–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML (2005) Crystal structures of the GluR5 and GluR6 ligand binding cores: molecular mechanisms underlying kainate receptor selectivity. Neuron 45: 539–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Olson R, Gouaux E (2001) Mechanisms for ligand binding to GluR0 ion channels: crystal structures of the glutamate and serine complexes and a closed apo state. J Mol Biol 311: 815–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr 40: 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara D, Smith EC, Calligaro DO, O'Malley PJ, McQuaid LA, Dingledine R (1990) 5,7-Dichlorokynurenic acid, a potent and selective competitive antagonist of the glycine site on NMDA receptors. Neurosci Lett 120: 17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RJ, Perrakis A, Lamzin VS (2003) ARP/wARP and automatic interpretation of protein electron density maps. Methods Enzymol 374: 229–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanao MH, Green T, Stern-Bach Y, Heinemann SF, Choe S (2005) Structure of the kainate receptor subunit GluR6 agonist-binding domain complexed with domoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 1708–1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naur P, Hansen KB, Kristensen AS, Dravid SM, Pickering DS, Olsen L, Vestergaard B, Egebjerg J, Gajhede M, Traynelis SF, Kastrup JS (2007) Ionotropic glutamate-like receptor delta2 binds D-serine and glycine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 14116–14121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naur P, Vestergaard B, Skov LK, Egebjerg J, Gajhede M, Kastrup JS (2005) Crystal structure of the kainate receptor GluR5 ligand-binding core in complex with (S)-glutamate. FEBS Lett 579: 1154–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M, Hinds H, Lu HP, Kawata M, Hayashi Y (2001) Motoneuron-specific expression of NR3B, a novel NMDA-type glutamate receptor subunit that works in a dominant-negative manner. J Neurosci 21: RC185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 277: 307–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter J, Merritt EA (2006) Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62: 439–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Otano I, Schulteis CT, Contractor A, Lipton SA, Trimmer JS, Sucher NJ, Heinemann SF (2001) Assembly with the NR1 subunit is required for surface expression of NR3A-containing NMDA receptors. J Neurosci 21: 1228–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem 26: 1781–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert A, Armstrong N, Gouaux JE, Howe JR (2005) AMPA receptor binding cleft mutations that alter affinity, efficacy, and recovery from desensitization. J Neurosci 25: 3752–3762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki YF, Rothe T, Premkumar LS, Das S, Cui J, Talantova MV, Wong HK, Gong X, Chan SF, Zhang D, Nakanishi N, Sucher NJ, Lipton SA (2002) Characterization and comparison of the NR3A subunit of the NMDA receptor in recombinant systems and primary cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol 87: 2052–2063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler T, Mesic I, Madry C, Bartholomaus I, Laube B (2008) Formation of NR1/NR2 and NR1/NR3 heterodimers constitutes the initial step in N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor assembly. J Biol Chem 283: 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smothers CT, Woodward JJ (2007) Pharmacological characterization of glycine-activated currents in HEK 293 cells expressing N-methyl-D-aspartate NR1 and NR3 subunits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 322: 739–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita Y, Okamoto Y (1999) Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem Phys Lett 314: 141–151 [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Olson R, Horning M, Armstrong N, Mayer M, Gouaux E (2002) Mechanism of glutamate receptor desensitization. Nature 417: 245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin AA, Isupov MN (2001) Spherically averaged phased translation function and its application to the search for molecules and fragments in electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 57: 1451–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaguine AA, Richelle J, Wodak SJ (1999) SFCHECK: a unified set of procedures for evaluating the quality of macromolecular structure-factor data and their agreement with the atomic model. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 55: 191–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston MC, Gertler C, Mayer ML, Rosenmund C (2006a) Interdomain interactions in AMPA and kainate receptors regulate affinity for glutamate. J Neurosci 26: 7650–7658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston MC, Schuck P, Ghosal A, Rosenmund C, Mayer ML (2006b) Conformational restriction blocks glutamate receptor desensitization. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 1120–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN (2001) Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 57: 122–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong HK, Liu XB, Matos MF, Chan SF, Perez-Otano I, Boysen M, Cui J, Nakanishi N, Trimmer JS, Jones EG, Lipton SA, Sucher NJ (2002) Temporal and regional expression of NMDA receptor subunit NR3A in the mammalian brain. J Comp Neurol 450: 303–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Mayer ML (2006) Characterization of a soluble ligand binding domain of the NMDA receptor regulatory subunit NR3A. J Neurosci 26: 4559–4566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Hermans J (1996) Hydrophilicity of cavities in proteins. Proteins 24: 433–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Cho Y, Lolis E, Howe JR (2008) Structural and single-channel results indicate that the rates of ligand binding domain closing and opening directly impact AMPA receptor gating. J Neurosci 28: 932–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data