Abstract

The mechanism behind the apparent lack of effective antiviral immune response in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is poorly understood. Although multiple levels of abnormalities have been identified in innate and adaptive immunity, it remains unclear if any of the subpopulations of T cells with regulatory capacity (Tregs) contribute to the induction and maintenance of HCV persistence. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge about Tregs as they relate to HCV infection.

Keywords: Tr1, Th3, CD8+ Tregs, FoxP3, IL-10, TGF-β, liver

INTRODUCTION

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is successful in establishing chronic persistency in the majority of individuals who encounter the infection, and it is one of the leading known causes of liver disease in the United States [1]. The estimated prevalence of HCV in the United States is at least 1.8% of the population, making HCV the most common chronic blood-borne infection nationally [1]. The main clinical manifestations of HCV infection are related to hepatitis; however, the extrahepatic manifestations and syndromes that are considered to be of immunologic origin are frequent (reviewed in refs. [2,3,4,5,6]). The financial burden of health care for HCV-infected individuals is on the rise, and thus, understanding the pathogenesis of the disease and development of pathogenesis-based, therapeutic approaches is emergent.

IMMUNE RESPONSE TO HCV

Similar to other viruses, eradication of HCV infection requires a complex and coordinated interplay between innate and adaptive immune responses [2]. A strong, multi-specific lymphocyte response, including participation of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, NK cells, and B lymphocytes in complex with equitable dendritic cell (DC) activity, is associated with pathogen clearance and disease resolution. In contrast, a narrowly focused and/or delayed response of T lymphocytes and limited B lymphocyte activation are associated with chronic HCV infection (reviewed in refs. [2,3,4,5,6]). The mechanism of impaired adaptive immune activation in patients who develop chronic HCV infection is not well understood; however, the inefficient and fading CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte activation seems to be a prevalent factor [6]. More recently, immature phenotype, impaired antigen-presenting and stimulatory capacity, imbalanced expression of costimulatory molecules in myeloid DC, low frequency of plasmacytoid DC in peripheral circulation, and a deficit in IFN-α production in HCV-infected patients were reported by some researchers [7,8,9,10,11,12,13] but not the others [14, 15], suggesting an impaired transition from innate to adaptive immunity during chronic HCV infection.

T CELL HETEROGENEITY AND REGULATORY T CELLS (Tregs)

Recent progress in T cell physiology indicated extensive heterogeneity within this immune population [16]. Based on phenotype and functional differences, CD4+ divides into Th1 cells, which produce IL-2 and IFN-γ, and Th2 cells, which secrete IL-4 and IL-5. Similarly, CD8+ cytotoxic type 1 T cell (Tc1) lymphocytes produce IFN-γ and a variety of other cytokines but no IL-4, and CD8+ Tc2 cells are rich in IL-4 but not IFN-γ [17]. The Th and Tc cells are the primary effector cells; if they are polarized (i.e., committed to a subtype) but “resting” (i.e., exhibit a heterogeneic, mostly low level of effector function in the absence of specific antigens), they are considered memory cells; the latter form memory effector cells when reactivated with specific antigens [16, 17].

More recently, it was acknowledged that some T cells exhibit inhibitory properties and suppress the activation of effector T cells [3, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Based on the phenotype and cytokine profile, Tregs are currently identified as naturally arising forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)+CD4+CD25+ Tregs (nTregs) [18], IL-10-producing CD4+ Treg type 1 (Tr1) [19], TGF-β-producing CD4+ Th3 [20], CD4+CD25+ Tregs converted from activated CD4+CD25– T cells [21] and IL-10- or TGF-β-producing CD8+ T cells [22], and a minor subset of CD4+CD25– cells that suppresses reactivity to self and foreign antigens [23, 24].

The signature of the Tregs is their potent ability to suppress the effector cells [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In vivo Tregs were shown to regulate oral tolerance, mucosal inflammation, and infection with nonself pathogens of different origin, including viruses [25], suggesting that Tregs may be intended to maintain a strict control over effector T cells at different stages of the immune defense.

Tregs AND HCV INFECTION

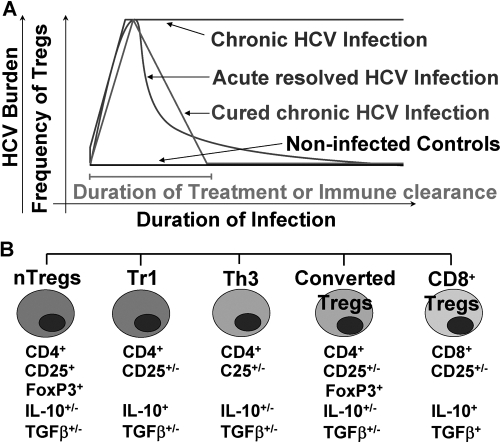

An increased frequency of T cells with regulatory phenotype and functions in human individuals and nonhuman primates with HCV infection was described by several groups of investigators [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] (Fig. 1). In humans, the Tregs are expanded during acute HCV infection [27, 34, 35], maintained during the chronic stage [26, 27, 29, 31, 37, 38], and lowered to the frequency of control individuals upon spontaneous (immune-mediated) recovery or treatment-induced cure from HCV [26, 27]; in chimpanzees, the frequency of Tregs was as high in spontaneously HCV-recovered as in persistently HCV-infected animals [33]. An increased frequency of Tregs at the onset of infection was suggested to predict a chronic outcome of the infection [34]. Further, quantitative CD4+CD25high Treg cell deficiency was observed in individuals with HCV-associated, autoimmune manifestations [36]. Yet, lower Treg frequency neither facilitated the activity of pathogen-specific T effector cells nor protected from the progression of HCV infection to chronic stage [36]. Collectively, these findings suggest an important role for Tregs in the pathogenesis of HCV infection but also imply that a certain balance between the frequency and the function of the Tregs is necessary to achieve an immune response that provides a reasonable outcome for the host by means of HCV clearance.

Fig. 1.

The dynamics (A) and the heterogeneity (B) of the Treg population in the peripheral blood during HCV infection in humans. (A) T cells with regulatory phenotype and functions are expanded during acute infection with HCV, are maintained during the chronic stage, and return to levels comparable with normal human individuals after HCV is resolved. (B) The Treg population expanded during HCV infection is heterogeneous; it includes FoxP3+ nTregs, Tr1, Th3, CD4+CD25+Tregs converted from activated T cells, and CD8+ Tregs. The dynamics of the individual Treg population during HCV infection is currently unknown; the mechanisms inducing/supporting/promoting/and those leading to termination of Treg activation during HCV infection are currently unknown; the depicted may not be exhaustive, as another, yet-undefined Treg population may coexist.

Treg POPULATIONS IN HCV INFECTION

FoxP3+ nTregs

nTregs are CD4+CD25+, express forkhead-winged helix transcription factor FoxP3+, CTLA-4, and a glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-α family-related protein (GITR), and are positive for a variety of adhesion molecules (CD11a, CD44, CD54, CD103) [38]. All nTregs markers, including FoxP3 (see below), are nonspecific and may be identified in the activated T cells in humans; however, the main characteristic of naturally arising T cells is the expression of these markers in the absence of specific antigenic stimulation [39, 40].

FoxP3+ nTregs originate from the common bone marrow progenitor and develop in the thymus [39]. Higher frequency of FoxP3+ Tregs was identified in chimpanzees [33] and in chronic HCV-infected patients compared with normal controls [38]. The functional assessment of FoxP3+ cells is technically challenging as a result of the intracellular nature of the marker [39, 40]. Although in vitro hyporesponsivenes to soluble stimulation via CD3 or IL-2R and suppression of CD4+ and CD8+ effector cells were suggested in nTregs of chimpanzees [33], no such data are available for humans with HCV infection.

Tr1 cells

The CD4+ Tr1 produce IL-10 but little to no IL-2; these cells do not express the Foxp3 and inhibit the in vitro proliferation of CD4+CD25– T cells [41]. Tr1 are distinct from Th2 cells, as they produce low levels of IL-2 and no IL-4, and although they produce IFN-γ, these levels are at least 1 log lower than those produced by Th1 cells [41].

Increased IL-10 production in CD4+CD25+ T cells, suggestive of Tr1, was identified in patients with chronic HCV infection by some investigators [31, 35, 42], however IL-10 neutralization did not augment the CD4+CD25+ T cell-induced suppression of the effector cell in another study [26]. Collectively, these data suggest that a better identification of Tr1 is needed to define their role in HCV infection.

Th3 cells

The signature of Th3 cells is TGF-β production [43]. Th3 cells were suspected to be present among HCV-induced Tregs in several studies [29, 31], however their identification proved technically challenging. The mRNA expression of TGF-β in treatment-naive HCV patients was observed in only a low percentage of PBL samples from patients, similar to controls [44]. Further, IFN-α treatment led to an increased frequency of TGF-β+ Th3 cells, and this correlated with reduction in liver enzymes and serum viral load in ∼30% of patients [44]. The PBMCs of responders to IFN-α therapy produced more TGF-β than nonresponders [45]. A small study from Ulsenheimer et al. [35] reported that ∼30% of HCV-infected patients exhibit CD4+TGF-β+ cells during the chronic stage of infection. More recently, Cabrera et al. [31] provided support for the concept that during HCV infection, Th3 may bear the activation marker CD25 by demonstrating that CD4+CD25+ cells secrete TGF-β protein. Further, an inhibitory role for TGF-β in the suppressive function of CD4+CD25+ cells was confirmed by use of blocking anti-TGF-β antibodies in some studies [40] but not in others [26]. Bolacchi et al. [29] reported that HCV-specific CD4+CD25+high T cells consistently produce TGF-β but only limited amounts of IL-10 and no IL-2 and IFN-γ. The HCV-specific TGF-β response by CD4+CD25+high T cells was significantly greater in patients with normal alanine transaminase (ALT) compared with patients with elevated ALT [29]. In addition, a significant inverse correlation was found between the HCV-specific TGF-β response by CD4+CD25+high T cells and liver inflammation [29]. These observations support the contention that increased Th3 Tregs may represent a defense mechanism to counteract HCV-related activation of the inflammatory cascade.

CD4+CD25+ Tregs converted from activated CD4+CD25– T cells

In humans, some CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells derive from the peripheral pool of CD4+CD45RO+CD25–FoxP3– memory T cells [21, 46, 47]. Further, the effector cell-derived Tregs may account for the dichotomy in the CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg population, consistent with differences in doubling time and in the susceptibility to apoptosis in subsets of nTregs [48].

Based on genetic analysis, Manigold et al. [33] suggested that in chimpanzees, HCV infection induces some CD4+CD25+ Tregs from activated CD4+CD25– T cells; this particular pathway of Treg conversion during HCV infection in humans awaits confirmation. However, this may prove to be a challenging task, as the current literature indicates that in humans, the majority of activated T cell subsets is CD25+ and can at least transiently express FoxP3 [47]. Under such circumstances, the identification of the true origins of Tregs in humans in general and during HCV infection in particular becomes more challenging compared with other species.

IL-10-producing CD8+ T cells

Impaired function of CD8+ T cells in response to HCV-derived antigens was reported previously; however, the mechanisms of such numerical and functional incompetence of this major effector T cell population during HCV infection remain elusive [6, 49]. The finding by Koziel and co-workers [37] of a subset of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells isolated from the liver that produced IL-10 sparked the hypothesis that the existence of MHC class I-restricted antigen specificity of CD8+ cells with regulatory activity may be real [50]. This hypothesis was supported further by the findings of Accapezzato et al. [51], who reported hepatic expansion of virus-specific CD8+ regulatory cells capable of in vitro suppression of proliferative responses of liver-derived lymphocytes in a HCV-specific and IL-10-dependent manner.

During HCV infection, CD8+ cells with regulatory capacity are HCV-specific and produce IL-10 and TGF-β [37]. More recently, Billerbeck et al. [52] reported parallel expansion of human HCV-specific FoxP3–CD8+ effector memory and de novo-generated FoxP3+CD8+ Tregs upon antigen recognition in vitro in an IL-2-dependent manner [52]; it is currently unknown if a similar mechanisms may occur in vivo, and it remains to be determined how CD8+ Tregs may influence the effector T cells during HCV infection.

Given the heterogeneity of the Treg population, it is conceivable to hypothesize coexistence of nTregs, induced/adaptive Tregs, and normal T cells when discussing HCV pathogenesis. For instance, the finding of CD4+CD25+TGF-β+ T cells could be an activated Th2 cell or a Th3 cell, depending on the IL-4 levels; the CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells could be of nTreg origin or derived from activated CD4+CD25+ cells; the CD8+ cells could be a FoxP3+ regulatory or FoxP3– effector cell, and so on. In this context, it is important to emphasize that only collective use of lineage markers (CD4, CD8, CD25, FoxP3), activation markers (CD25), cytokine profile, and yet-to-be discovered population-specific markers, together with the functional assessment, will have value for identification of Tregs at a given stage of HCV-induced disease and for the mechanistic explanations of the Treg origin, function, and fate during HCV infection.

MECHANISMS OF Treg SUPRESSION

In normal humans, the suppressive activity of Tregs is achieved via direct mechanisms, which mainly include direct cell-to-cell contact [39, 46, 48]. The exact cellular proteins responsible for cell-to-cell contact inhibition are of interest, and CTLA-4, GITR, and programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) are among the best candidates [43, 53,54,55,56,57]. Among direct mechanisms of Treg inhibitory potential is also the production of immunoinhibitory cytokines, such as IL-10 or TGF-β [37]. Often, Tregs achieve their suppressive effects via indirect mechanisms, via interaction with other immune cells, or triggering of cell-derived soluble mediators. Induction of IL-10 and TGF-β production in DC, suppression of homeostatic proliferation, cytotoxicity, and IL-12-mediated IFN-γ production in NK cells, and induction of indoleaminem 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) in DC in a CTLA-4-dependent manner are a few to mention [39, 46]. More recently, adenosine and cAMP have been shown to contribute to the suppressive capacity of Tregs [58]; however, the specific Treg origin of those metabolites is yet to be confirmed.

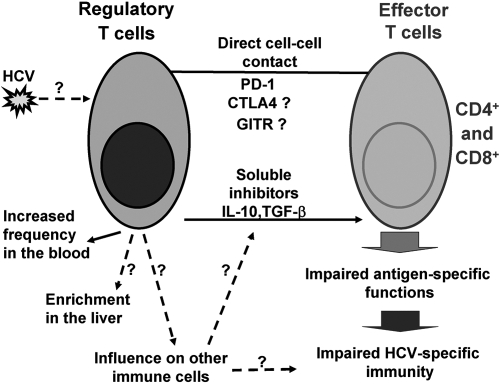

The mechanisms by which Tregs limit the activation of HCV-specific effector cells are under scrutiny. In humans with acute HCV infection, the suppressive capacity of CD4+CD25+ Tregs in vitro was higher [34], and in those with chronic HCV infection, it was not different [27] or enhanced [26, 28] compared with controls or HCV-recovered individuals. Further, the degree of suppression of effector cell reactivity by CD4+CD25+ Tregs is enhanced in HCV patients with normal liver functions compared with those with elevated ALT values [29]. A lack of difference in the strength of the inhibitory capacity of Tregs was seen in chimpanzees with chronic infection compared with HCV naïve animals [33]. More often than not, the inhibitory capacity of different Tregs during HCV infection may depend on TGF-β or IL-10 [31, 37], and cell-to-cell contact is indispensable [26, 27, 29, 31, 34], suggesting that HCV-specific Tregs use direct and indirect mechanisms (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The mechanisms of inhibitory effects of Tregs during chronic HCV infection. Tregs use direct cell–cell contact (via PD-1 and other surface molecules, such as CTLA-4 and GITR) and soluble inhibitory factors (IL-10, TGF-β) to suppress the effector cell functions, thus resulting in impaired anti-HCV immunity. The direct role of HCV or HCV-derived products (proteins, genomic material) in generation and/or expansion of Tregs is yet to be identified. Tregs are enriched in peripheral blood and are detected with increased frequency in the livers of patients with chronic HCV infection. Hypothetically, the enriched Treg population may affect other immune cell populations, which may also produce immunoinhibitory soluble mediators and thus, collectively contribute to impaired, anti-HCV immunity. The known connections are pictured with solid lines; the hypothetical connections are pictured with dashed lines and marked as questionable.

CONTROL OF Treg-MEDIATED SUPRESSION DURING HCV INFECTION

Antigen specificity of Tregs

As all other T cells, Tregs express the TCR complex [25, 59], and there are clear indications that Tregs may be antigen-specific during HCV infection [29, 30, 42]. Li et al. [30] reported that the culture of PBMCs of HCV-positive patients, but not those of controls, with HCV protein-derived peptides rapidly induces CD25+highIFN-γ–FoxP3high Tregs. The target HCV peptide that can stimulate Tregs varied between patients, but within any given subject, only a small number of the peptides were able to stimulate Tregs, suggesting the existence of dominant Treg epitopes [30]. Further, the CD8+ Tregs from livers and blood of HCV-infected individuals are also HCV-specific [37, 50].

More recently, Tuovinen et al. [60] reported that in normal humans, most nTregs present two fully functional TCRs. The expression of two TCRs coincides with higher expression of FoxP3 compared with nTregs with single TCR counterparts [60]. The lack of allelic exclusion of TCR α locus gives rise to two different TCRs in 10–30% of all mature T cells, and dual TCR increases the survival and facilitates the autoreactivity of these T cells [60, 61]. Stimulation via TCR drives antigen-specific proliferation of Tregs and renders them to inherit the suppressive properties of their progenitors [60]. Further, TCR function in Tregs is independent of costimulatory molecules, as antigens alone without aid from APCs are capable of triggering Treg proliferation and their inhibitory activity of effector cells [39, 59]. Given the existence of HCV-specific Tregs during chronic HCV infection, it is plausible to predict that if the presence of Tregs with dual TCR will be confirmed in HCV-infected patients, it may partially encounter for the lack of a differential hierarchy in the capacity of CD4+CD25+ Tregs to suppress CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation in response to distinct pools of HCV-derived peptides [27].

Costimulatory molecules

Costimulatory molecule expression provides a layer of control at the interface between Tregs and other cells, mainly APCs [7,8,9]. Classical costimulatory molecules, such as CD28 and CD40, control thymic development and peripheral homeostasis of nTregs and maintain a stable pool of peripheral Tregs by supporting their survival and promoting their self-renewal [62]. Further, CD28 engagement promotes survival by regulating IL-2 production in conventional T cells and CD25 expression on Tregs [62]. Stimulation via CD40 ligand (CD40L) can induce the expansion of Tregs, and CD40 deficiency renders low frequency of T cells with regulatory capacity in the periphery [63]. Some other membrane molecules of Tregs, such as alternative costimulatory molecules CTLA-4 (CD152), GITR, OX-40 (CD134), ICOS (H4, ILIM), PD-1, linker for activated T cell, and B and T lymphocyte attenuator, are among known modulators of the function of Tregs [23, 25, 28, 38, 39, 43, 46, 53, 55,56,57].

Delineation of the role of each individual, costimulatory molecule in Treg function during HCV infection awaits exploration; however, there are indications that the PD-1 system may be at least in part responsible for the inhibitory functions of Tregs in individuals with chronic HCV infection [56, 57].

TLR

More recently, several studies pointed to the role of TLRs in the maintenance, expansion, and functional potential of mouse Tregs [64, 65]. Mouse and human CD4+CD25+ Tregs express a variety of TLRs, including TLR2 and its coreceptors, TLR1 and TLR6, as well as TLR4, TLR5, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 [66].

To date, there is no convincing evidence that during HCV infection, TLRs would affect Treg function directly: The levels of TLR expression in Tregs of HCV-infected patients are unknown, and the proof that TLR engagement with a HCV-derived component, by analogy with other cell types [67, 68], may affect the status of Tregs is awaited.

MECHANISM OF Treg GENERATION DURING HCV INFECTION

DC-dependent Treg generation

It is well documented that some subsets of DC can trigger proliferation of Tregs in humans [69,70,71]. Plasmacytoid DC directly activate Tregs via IDO [71]. Immature DC phenotype, production of IL-10, low expression of classic costimulatory molecules CD80, CD83, and CD86, expression of alternative, costimulatory molecules, and exposure to excessive amounts of GM-CSF, glucocorticoids, or IFN-λ are among the factors that favor Treg proliferation and/or function upon in vitro coculture with myeloid DCs [8,9,10,11,12,13, 69,70,71], and the contribution of each of those factors in vivo remains to be determined. Proinflammatory cytokines produced by TLR-activated, mature DC are required for reversal of CD4+CD25+ Treg anergy [72, 73]. Concomitantly, cytokines secreted by TLR-stimulated DC are indispensable for CD4+ effector cells to overcome the inhibitory capacity of CD4+CD25+ Tregs [73].

The formal proof that DC are implicated in expansion or function of Tregs during HCV infection is awaited. Such a possibility is conceivable, given the elevated production of IL-10 and immature phenotype of myeloid DC in patients with chronic HCV infection [8,9,10,11], the limited induction of Th1 responses and skewed composition of CD4+ T cell populations in a DC-dependent manner after engagement of DC by the HCV core [8, 74], and the reduced IFN-γ secretion by allogeneic CD4+ T lymphocytes during mixed lymphocyte culture upon use of human monocyte-derived DC stimulated with the HCV core or anti-gC1qR agonist antibody [74]. To date, it is not clear what the minimum requirement is for DC to facilitate proliferation of HCV-specific Tregs, and it is unknown if the DC of HCV-infected patients stimulate the proliferation of existing Tregs or promote their de novo generation.

Other possible mechanisms of Treg expansion and functional enhancement during HCV infection

Several other mechanisms, possibly DC-independent, have been implicated lately in Treg expansion in normal humans.

DC expressing IDO enhance the function of Tregs [71]. It is unclear what the cellular sources and the mechanism of IDO induction are during HCV infection; however, up-regulation of IDO expression in the liver and an increased serum kynurenine:tryptophan ratio (a reflection of IDO activity) were reported in humans with chronic infection, and HCV clearance was associated with normalization of liver IDO levels [75]. Hepatic IDO expression was also normal in HCV-infected chimpanzees that cured the infection, and it remained high in those that progressed to chronicity [75].

The T cells isolated from blood and livers of HCV-infected patients or chimpanzees express high levels of PD-1 compared with healthy donors [56, 76, 77]. In addition, PD-1 and PDL-1 expression is up-regulated on healthy donor T cells exposed to a HCV core, a nucleocapsid protein that is immunosuppressive [78]. Further, up-regulation of PD-1 is mediated through interaction of the HCV core with the complement receptor, gC1qR [78], which was also reported as a receptor for the HCV core protein [74]. Blocking of the costimulatory molecule B7-H1, a ligand of PD-1, significantly enhanced the frequency of IFN-γ-producing, HCV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ effector T cells and the production of Th1 but not Th2 cytokines [79]. Collectively, these data suggest that alternative pathways, including IDO and PD-1, regardless of their origin and specific localization, may have a critical regulatory role in Treg function during HCV infection.

CONSEQUENCES OF INCREASED FREQUENCY OF Tregs DURING HCV INFECTION

Cross-talk between Tregs

The collaboration between different types of Tregs is difficult to prove but easy to envision, mainly because of the antigen specificity but also overlapping, functional outcomes of different Treg populations. During HCV infection, some Treg populations produce IL-10 and TGF-β [29, 37, 42], and neither IL-10 nor TGF-β was always necessary for the inhibitory effects of Tregs [26], thus suggesting that soluble components, including IL-10 and TGF-β, among other yet-to-be-determined factors, may be implicated in the crosstalk of Tregs.

Bystander supression

Once activated, antigen-specific Tregs are capable of bystander suppression, an inhibition of nonrelated immune responses in an antigen-independent manner that requires direct cell-to-cell contact or production of regulatory cytokines [80]. The existence of bystander supression is a key question for the pathogenesis of HCV infection. Although the majority of physicians will agree that patients with acute or chronic HCV infection are not globally immunosuppressed, El-Serag et al. [81] reported that after excluding potentially immunocompromised patients, including those with HIV, organ transplant, and cirrhosis, HCV remained significantly associated with cytomegalovirus, cryptococcus, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted diseases. Recent evidence supports the idea that infection-induced Tregs may have a major implication in the outcome of secondary infections [80]. It remains to be determined if the above-mentioned infectious diseases that are more common among HCV-infected patients compared with controls [81] are a result of behavioral, environmental, or genetic factors or immunosuppression, possibly implicating Tregs.

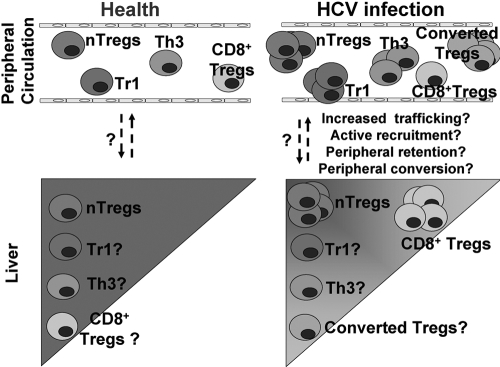

Treg recruitment to the liver

Recruitment of Tregs to the site of infection is a common strategy used by the host [82]. Although the distribution of the Treg populations in the liver may be comparable with peripheral circulation, the exact composition and the mechanisms of Treg recruitment to the liver during HCV infection are yet to be determined (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The hypothetical composition of Tregs in the liver and in peripheral circulation in HCV-infected individuals compared with controls. Treg populations are present in the livers of controls; however, their frequency may not reach those observed in peripheral circulation. HCV infection induces expansion of Tregs in the peripheral blood and leads to enrichment of CD8+ Tregs in the liver; it is hypothesized that other Tregs are enriched in the liver, proportional to their enrichment in the peripheral circulation. The mechanisms of Treg enrichment in the liver may include increased trafficking, active recruitment, peripheral retention, and/or peripheral converson; the exact mechanisms occurring during HCV infection are currently unknown.

A recent report by Ward et al. [83] indicates the presence of strikingly high numbers of CD4+FoxP3+Tregs in the portal tract infiltrates of HCV-infected livers, with a remarkably consistent 2:1 ratio of total CD4+/FoxP3+ cells in the liver across a wide range of disease states compared with PBMC (10:1) [83]. The findings of FoxP3+ cells in the absence of increased IFN-γ expression [83] suggest that these FoxP3+ cells are truly regulatory cells and imply their apartenence to a naturally arising population rather than conversion from activated T lymphocytes.

It is not clear what the roles of Tregs are in the liver during HCV infection. Treg deficiency does not render the host resistant to HCV infection and does not protect against HCV-induced liver injury [36], thus suggesting that accumulation of Tregs in the liver is rather related to the abundance of HCV-derived antigens in the liver as a target organ of infection. Recently, Kobayashi et al. [84] reported that the high prevalence of FoxP3+ Tregs infiltrating hepatocellular carcinoma significantly lowers the survival rate of patients. Although it may not be possible to dissect if Treg enrichment into the liver is a result of HCV infection or cancer development, given their interdependence [2], these findings suggest that Tregs affect the development and progression of hepatocarcinogenesis, including that of HCV etiology [84].

INTERACTIONS OF Tregs WITH OTHER IMMUNE CELLS DURING HCV INFECTION

Tregs and CD8+ T lymphocytes

In vivo depletion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs from peripheral blood in humans increases the frequency of functional, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells [85], and ex vivo CD4+CD25+ Tregs regulate the CD8+ effector T cells numerically and functionally [26,27,28]. Further, CD4+CD25+ Tregs control the CD8+ T cell maturation and their functional potential in an antigen-specific manner [28].

During HCV infection, Treg-mediated suppression of virus-specific CD8+ T cells is present in patients with a chronic course and in those who cleared the infection; however, controversies exist between the studies [26, 27]. Further, although CD4+CD25+ Tregs limit the HCV-induced expansion of CD8+ T cells, their inhibitory capacity was also extended to other viruses, such as influenza, CMV, and EBV, suggesting a pan-suppressive rather than antigen-specific activity of autologouse Tregs [26, 28]. So far, it is clear that during HCV infection, CD4+CD25+ Tregs modulate CD8+ T cells via direct cell-to-cell contact, and cytokine-mediated suppression may play a secondary role [26, 28]; the role of the Treg/CD8+ T cell interaction in the CD8+ T cell functional insufficiency during HCV infection in vivo requires further investigation.

Tregs and CD4+ T lymphocytes

The importance of the understanding the mechanisms of interactions between the Treg and CD4+ effector T lymphocyte populations during HCV infection is highlighted by the findings of a remarkable tenfold difference in CD4+ T cell responses to HCV-derived peptides between the recovered and chronic HCV-infected patients [27]. More recently, Campbell and Ziegler [86] proposed three different models about how nTregs may influence the signaling in conventional effector CD4+ T cells of normal individuals: Engagement of the TCR and CD28 leads to activation of signaling pathways that culminate in the nuclear translocation of NF-AT, NF-κB, and AP-1 and subsequent transcription of the IL-2 gene; direct regulation of TCR-mediated signaling by FoxP3, where FoxP3 blocks TCR signaling through the inhibition of transcriptional activation mediated by NF-AT, NF-κB, and AP-1; and FoxP3 indirectly regulates TCR-mediated signaling through the expression of a factor that can inhibit TCR-induced signals.

Each of these models can be envisioned easily; however, none of them is confirmed in HCV infection. Furthermore, CD4+ effector cells are also inhibited in the presence of Tr1 and Th3 cells [29, 31, 35, 42], and there is no indication that any of the above-mentioned models for nTregs could be extrapolated to Tr1 or Th3 cells during HCV infection. Finally, the working hypothesis that CD25high may suppress T cells via competititon for IL-2 [87] remains to be confirmed in HCV infection.

Tregs and DC

In normal individuals, Tregs may largely influence the DC functions. The Tregs protect the host against overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines, as the absence of CD4 renders the host to overproduce TLR2- and TLR4-induced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [88, 89]. At the early stage of DC/T cell contact, CD4+CD25+ T cells skew DC cytokine production toward low IL-6 and high IL-10 production [88] and inhibit CD4+ T cells/DC contacts in vivo [90]. Further, CD4+CD25+ Tregs strongly suppress TLR-triggered maturation of myeloid but not plasmacytoid DC, manifested as a lack of up-regulation of costimulatory molecules, inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production, enhanced IL-10 production, and poor antigen-presenting function [89].

Although multiple defects of DC were described in patients [7,8,9,10,11,12,13], to date, it is unknown if and if so how Tregs modulate DC functions during HCV infection.

Tregs and monocytes/macrophages

The role of interactions between Tregs and monocytes/macrophages is currently under investigation. Coculture of normal Tregs with monocytes/macrophages leads to moduation of the former, as indicated by the up-regulation expression of CD206 (macrophage mannose receptor) and CD163 (hemoglobin scavenger receptor), increased CCL18 production, and enhanced phagocytic capacity but also, limited up-regulation of HLA class II, CD40, and CD80 and down-regulation of CD86 compared with control-treated cells [91]. At the mechanistic level, studies reveal that CD4+CD25+CD127lowFoxp3+ Tregs produce IL-10, IL-4, and IL-13, and these cytokines suppress the proinflammatory cytokine response in macrophages [92].

In chronic hepatitis C infection, signs of activation of blood and liver monocytes/macrophages, including increased expression of CD163 and IL-10 [8, 12, 93] and increased frequency of Tregs in the livers of HCV-infected individuals, were reported [83]; however, the colocalizations and/or direct interactions between monocytes/macrophages and Tregs in the liver or in other immune organs during HCV infection are currently unknown.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Currently, we know that T cells with regulatory capacity are enriched during HCV infection; this population is heterogeneous and includes HCV-specific cells, and it uses direct and indirect mechanisms to suppress the activity of effector cells.

An in-debt characterization of the Treg populations during acute and chronic HCV infection is emergent. With regards to the implications of different populations of Tregs in the pathogenesis of HCV infection, we still lack knowledge about how the Tregs are induced, how they function, and what the contributions are of each Treg subpopulation to the anti-HCV immunity. These basic questions will better define the interactions between Tregs and other immune cells and possibly identify Treg-associated, therapeutic targets directed to HCV clearance.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from National Institutes of Health for their research (grants AA016571 to A. D. and AA008577 and AA011576 to G. S.).

References

- NIH Consensus Statement on Management of Hepatitis C: 2002 NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002;19:1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler U, Nattermann J. Immunopathogenesis in hepatitis C virus cirrhosis. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112:141–155. doi: 10.1042/CS20060171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K M. Regulatory T cells in hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:S327–S330. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racanelli V, Rehermann B. Hepatitis C virus infection: when silence is deception. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:456–464. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K M. Immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:89–105. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen D G, Walker C M. Adaptive immune responses in acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2005;436:946–952. doi: 10.1038/nature04079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auffermann-Gretzinger S, Keeffe E B, Levy S. Impaired dendritic cell maturation in patients with chronic, but not resolved, hepatitis C virus infection. Blood. 2001;97:3171–3176. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolganiuc A, Kodys K, Kopasz A, Marshall C, Do T, Romics L, Jr, Mandrekar P, Zapp M, Szabo G. Hepatitis C virus core and nonstructural protein 3 proteins induce pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and inhibit dendritic cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2003;170:5615–5624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain C, Fatmi A, Zoulim F, Zarski J P, Trépo C, Inchauspé G. Impaired allostimulatory function of dendritic cells in chronic hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:512–524. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanto T, Hayashi N, Takehara T, Tatsumi T, Kuzushita N, Ito A, Sasaki Y, Kasahara A, Hori M. Impaired allostimulatory capacity of peripheral blood dendritic cells recovered from hepatitis C virus-infected individuals. J Immunol. 1999;162:5584–5591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelderblom H C, Nijhuis L E, de Jong E C, te Velde A A, Pajkrt D, Reesink H W, Beld M G, van Deventer S J, Jansen P L. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells from chronic HCV patients are not infected but show an immature phenotype and aberrant cytokine profile. Liver Int. 2007;27:944–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolganiuc A, Chang S, Kodys K, Mandrekar P, Bakis G, Cormier M, Szabo G. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein-induced, monocyte-mediated mechanisms of reduced IFN-α and plasmacytoid dendritic cell loss in chronic HCV infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:6758–6768. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Bella S, Crosignani A, Riva A, Presicce P, Benetti A, Longhi R, Podda M, Villa M L. Decrease and dysfunction of dendritic cells correlate with impaired hepatitis C virus-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Immunology. 2007;121:283–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M, Babcock E, Grakoui A, Shoukry N, Lauer G, Rice C, Walker C, Bhardwaj N. Lack of phenotypic and functional impairment in dendritic cells from chimpanzees chronically infected with hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2004;78:6151–6161. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6151-6161.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longman R S, Talal A H, Jacobson I M, Albert M L, Rice C M. Presence of functional dendritic cells in patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus. Blood. 2004;103:1026–1029. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodland D L, Dutton R W. Heterogeneity of CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:336–342. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgame P, Abrams J S, Clayberger C. Differing lymphokine profiles of functional subsets of human CD4 and CD8 T cell clones. Science. 1991;254:279–282. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehérvári Z, Sakaguchi S. Control of Foxp3+ CD25+CD4+ regulatory cell activation and function by dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1769–1780. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrat F J, Cua D J, Boonstra A, Richards D F, Crain C, Savelkoul H F, de Waal-Malefyt R, Coffman R L, Hawrylowicz C M, O'Garra A. In vitro generation of interleukin 10-producing regulatory CD4(+) T cells is induced by immunosuppressive drugs and inhibited by T helper type 1 (Th1)- and Th2-inducing cytokines. J Exp Med. 2002;195:603–616. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerwenka A, Swain S L. TGF-β1: immunosuppressant and viability factor for T lymphocytes. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1291–1296. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Zhang Y, Cook J E, Fletcher J M, McQuaid A, Masters J E, Rustin M H, Taams L S, Beverley P C, Macallan D C, Akbar A N. Human CD4+ CD25hi Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are derived by rapid turnover of memory populations in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2423–2433. doi: 10.1172/JCI28941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz D A, Zheng S G, Gray J D. The role of the combination of IL-2 and TGF-β or IL-10 in the generation and function of CD4+ CD25+ and CD8+ regulatory T cell subsets. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:471–478. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0503228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J, Huehn J, de la Rosa M, Maszyna F, Kretschmer U, Krenn V, Brunner M, Scheffold A, Hamann A. Expression of the integrin α Eβ 7 identifies unique subsets of CD25+ as well as CD25– regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13031–13036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192162899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graca L, Thompson S, Lin C Y, Adams E, Cobbold S P, Waldmann H. Both CD4(+)CD25(+) and CD4(+)CD25(–) regulatory cells mediate dominant transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 2002;168:5558–5565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse B T, Sarangi P P, Suvas S. Regulatory T cells in virus infections. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:272–286. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettler T, Spangenberg H C, Neumann-Haefelin C, Panther E, Urbani S, Ferrari C, Blum H E, von Weizsäcker F, Thimme R. T cells with a CD4+CD25+ regulatory phenotype suppress in vitro proliferation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:7860–7867. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7860-7867.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Ikeda F, Stadanlick J, Nunes F A, Alter H J, Chang K M. Suppression of HCV-specific T cells without differential hierarchy demonstrated ex vivo in persistent HCV infection. Hepatology. 2003;38:1437–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushbrook S M, Ward S M, Unitt E, Vowler S L, Lucas M, Klenerman P, Alexander G J. Regulatory T cells suppress in vitro proliferation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during persistent hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:7852–7859. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7852-7859.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolacchi F, Sinistro A, Ciaprini C, Demin F, Capozzi M, Carducci F C, Drapeau C M, Rocchi G, Bergamini A. Increased hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes and reduced HCV-specific CD4+ T cell response in HCV-infected patients with normal versus abnormal alanine aminotransferase levels. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Jones K L, Woollard D J, Dromey J, Paukovics G, Plebanski M, Gowans E J. Defining target antigens for CD25+ FOXP3 + IFN-γ-regulatory T cells in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:197–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera R, Tu Z, Xu Y, Firpi R J, Rosen H R, Liu C, Nelson D R. An immunomodulatory role for CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T lymphocytes in hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2004;40:1062–1071. doi: 10.1002/hep.20454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J H, Zhang Y X, Yu R B, Su C, Sun N X. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress CD4+ T cell responses in patients with persistent hepatitis C virus infection. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2006;45:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manigold T, Shin E C, Mizukoshi E, Mihalik K, Murthy K K, Rice C M, Piccirillo C A, Rehermann B. Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ T cells control virus-specific memory T cells in chimpanzees that recovered from hepatitis C. Blood. 2006;107:4424–4432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrella A, Vitiello L, Atripaldi L, Conti P, Sbreglia C, Altamura S, Patarino T, Vela R, Morelli G, Bellopede P, Alone C, Racioppi L, Perrella O. Elevated CD4+/CD25+ T cell frequency and function during acute hepatitis C presage chronic evolution. Gut. 2006;55:1370–1371. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.099887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulsenheimer A, Gerlach J T, Gruener N H, Jung M C, Schirren C A, Schraut W, Zachoval R, Pape G R, Diepolder H M. Detection of functionally altered hepatitis C virus-specific CD4 T cells in acute and chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;37:1189–1198. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer O, Saadoun D, Abriol J, Dodille M, Piette J C, Cacoub P, Klatzmann D. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell deficiency in patients with hepatitis C-mixed cryoglobulinemia vasculitis. Blood. 2004;103:3428–3430. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alatrakchi N, Graham C S, van der Vliet H J, Sherman K E, Exley M A, Koziel M J. Hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD8+ cells produce transforming growth factor β that can suppress HCV-specific T-cell responses. J Virol. 2007;81:5882–5892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02202-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebinuma H, Nakamoto N, Li Y, Price D A, Gostick E, Levine B L, Tobias J, Kwok W W, Chang K M. Identification and in-vitro expansion of functional antigen-specific CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T-cells in hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2008;82:5043–5053. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01548-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi G, Turner M S, Thomson A W, Morel P A. Naturally occurring regulatory T cells: recent insights in health and disease. Crit Rev Immunol. 2007;27:61–95. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v27.i1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin M A, Torgerson T R, Houston E, DeRoos P, Ho W Y, Stray-Pedersen A, Ocheltree E L, Greenberg P D, Ochs H D, Rudensky A Y. Single-cell analysis of normal and FOXP3-mutant human T cells: FOXP3 expression without regulatory T cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6659–6664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509484103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarolo M G, Gregori S, Battaglia M, Bacchetta R, Fleischhauer K, Levings M K. Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:28–50. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald A J, Duffy M, Brady M T, McKiernan S, Hall W, Hegarty J, Curry M, Mills K H. CD4 T helper type 1 and regulatory T cells induced against the same epitopes on the core protein in hepatitis C virus-infected persons. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:720–727. doi: 10.1086/339340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q, Boden E K, Henriksen K J, Bour-Jordan H, Bi M, Bluestone J A. Distinct roles of CTLA-4 and TGF-β in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell function. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2996–3005. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S, Gershtein V, Elias N, Zuckerman E, Salman N, Lahat N. mRNA cytokine profile in peripheral blood cells from chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients: effects of interferon-α (IFN-α) treatment. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:55–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball P, Elswick R K, Shiffman M. Ethnicity and cytokine production gauge response of patients with hepatitis C to interferon-α therapy. J Med Virol. 2001;65:510–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taams L S, Akbar A N. Peripheral generation and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;293:115–131. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27702-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ioan-Facsinay A, van der Voort E I, Huizinga T W, Toes R E. Transient expression of FOXP3 in human activated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:129–138. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatenoud L, Bach J F. Adaptive human regulatory T cells: myth or reality? J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2325–2327. doi: 10.1172/JCI29748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruener N H, Lechner F, Jung M C, Diepolder H, Gerlach T, Lauer G, Walker B, Sullivan J, Phillips R, Pape G R, Klenerman P. Sustained dysfunction of antiviral CD8+ T lymphocytes after infection with hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2001;75:5550–5558. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5550-5558.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedemeyer H, He X S, Nascimbeni M, Davis A R, Greenberg H B, Hoofnagle J H, Liang T J, Alter H, Rehermann B. Impaired effector function of hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cells in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:3447–3458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accapezzato D, Francavilla V, Paroli M, Casciaro M, Chircu L V, Cividini A, Abrignani S, Mondelli M U, Barnaba V. Hepatic expansion of a virus-specific regulatory CD8(+) T cell population in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:963–972. doi: 10.1172/JCI20515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billerbeck E, Blum H E, Thimme R. Parallel expansion of human virus-specific FoxP3– effector memory and de novo-generated FoxP3+ regulatory CD8+ T cells upon antigen recognition in vitro. J Immunol. 2007;179:1039–1048. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, Ishida Y, Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:135–142. doi: 10.1038/ni759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh R S, Whitters M J, Piccirillo C A, Young D A, Shevach E M, Collins M, Byrne M C. CD4(+)CD25(+) immunoregulatory T cells: gene expression analysis reveals a functional role for the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor. Immunity. 2002;16:311–323. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valzasina B, Guiducci C, Dislich H, Killeen N, Weinberg A D, Colombo M P. Triggering of OX40 (CD134) on CD4(+)CD25+ T cells blocks their inhibitory activity: a novel regulatory role for OX40 and its comparison with GITR. Blood. 2005;105:2845–2851. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radziewicz H, Ibegbu C C, Fernandez M L, Workowski K A, Obideen K, Wehbi M, Hanson H L, Steinberg J P, Masopust D, Wherry E J, Altman J D, Rouse B T, Freeman G J, Ahmed R, Grakoui A. Liver-infiltrating lymphocytes in chronic human hepatitis C virus infection display an exhausted phenotype with high levels of PD-1 and low levels of CD127 expression. J Virol. 2007;81:2545–2553. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02021-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbani S, Amadei B, Tola D, Massari M, Schivazappa S, Missale G, Ferrari C. PD-1 expression in acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with HCV-specific CD8 exhaustion. J Virol. 2006;80:11398–11403. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01177-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp T, Becker C, Klein M, Klein-Hessling S, Palmetshofer A, Serfling E, Heib V, Becker M, Kubach J, Schmitt S, Stoll S, Schild H, Staege M S, Stassen M, Jonuleit H, Schmitt E. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate is a key component of regulatory T cell-mediated suppression. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1303–1310. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picca C C, Larkin J, III, Boesteanu A, Lerman M A, Rankin A L, Caton A J. Role of TCR specificity in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell selection. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:74–85. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuovinen H, Salminen J T, Arstila T P. Most human thymic and peripheral-blood CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells express 2 T-cell receptors. Blood. 2006;108:4063–4070. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J I, Altmann D M. Dual T cell receptor α chain T cells in autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1995;182:953–959. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q, Henriksen K J, Boden E K, Tooley A J, Ye J, Subudhi S K, Zheng X X, Strom T B, Bluestone J A. Cutting edge: CD28 controls peripheral homeostasis of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:3348–3352. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanogoh A, Wang X, Lee I, Watanabe C, Kamanaka M, Shi W, Yoshida K, Sato T, Habu S, Itoh M, Sakaguchi N, Sakaguchi S, Kikutani H. Increased T cell autoreactivity in the absence of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions: a role of CD40 in regulatory T cell development. J Immunol. 2001;166:353–360. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutmuller R P, den Brok M H, Kramer M, Bennink E J, Toonen L W, Kullberg B J, Joosten L A, Akira S, Netea M G, Adema G J. Toll-like receptor 2 controls expansion and function of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:485–494. doi: 10.1172/JCI25439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramalho I, Lopes-Carvalho T, Ostler D, Zelenay S, Haury M, Demengeot J. Regulatory T cells selectively express Toll-like receptors and are activated by lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 2003;197:403–411. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabelitz D. Expression and function of Toll-like receptors in T lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhans B, Braunschweiger I, Nischalke H D, Nattermann J, Sauerbruch T, Spengler U. Presentation of the HCV-derived lipopeptide LP20–44 by dendritic cells enhances function of in vitro-generated CD4+ T cells via up-regulation of TLR2. Vaccine. 2006;24:3066–3075. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolganiuc A, Oak S, Kodys K, Golenbock D T, Finberg R W, Kurt-Jones E, Szabo G. Hepatitis C core and nonstructural 3 proteins trigger Toll-like receptor 2-mediated pathways and inflammatory activation. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1513–1524. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi H, Godot V, Maillot M C, Prejean M V, Cohen N, Krzysiek R, Lemoine F M, Zou W, Emilie D. Induction of antigen-specific regulatory T lymphocytes by human dendritic cells expressing the glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper. Blood. 2007;110:211–219. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennechet F J, Uzé G. Interferon-λ-treated dendritic cells specifically induce proliferation of FOXP3-expressing suppressor T cells. Blood. 2006;107:4417–4423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M D, Baban B, Chandler P, Hou D Y, Singh N, Yagita H, Azuma M, Blazar B R, Mellor A L, Munn D H. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells from mouse tumor-draining lymph nodes directly activate mature Tregs via indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2570–2582. doi: 10.1172/JCI31911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo T, Hatton R D, Oliver J, Liu X, Elson C O, Weaver C T. Regulatory T cell suppression and anergy are differentially regulated by proinflammatory cytokines produced by TLR-activated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:7249–7258. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll pathway-dependent blockade of CD4+CD25+ T cell-mediated suppression by dendritic cells. Science. 2003;299:1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1078231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner S N, Hall C H, Hahn Y S. HCV core protein interaction with gC1q receptor inhibits Th1 differentiation of CD4+ T cells via suppression of dendritic cell IL-12 production. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:1407–1419. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0507268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrea E, Riezu-Boj J I, Gil-Guerrero L, Casares N, Aldabe R, Sarobe P, Civeira M P, Heeney J L, Rollier C, Verstrepen B, Wakita T, Borrás-Cuesta F, Lasarte J J, Prieto J. Upregulation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2007;81:3662–3666. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02248-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbani S, Amadei B, Tola D, Massari M, Schivazappa S, Missale G, Ferrari C. PD-1 expression in acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with HCV-specific CD8 exhaustion. J Virol. 2006;80:11398–11403. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01177-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen D G, Shoukry N H, Grakoui A, Fuller M J, Cawthon A G, Dong C, Hasselschwert D L, Brasky K M, Freeman G J, Seth N P, Wucherpfennig K W, Houghton M, Walker C M. Variable patterns of programmed death-1 (PD-1) expression on fully functional memory T cells following spontaneous resolution of hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2008;82:5109–5114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00060-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z Q, King E, Prayther D, Yin D, Moorman J. T cell dysfunction by hepatitis C virus core protein involves PD-1/PDL-1 signaling. Viral Immunol. 2007;20:276–287. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H Y, Lee Y J, Seo S K, Lee S W, Park S J, Lee J N, Sohn H S, Yao S, Chen L, Choi I. Blocking of monocyte-associated B7–H1 (CD274) enhances HCV-specific T cell immunity in chronic hepatitis C infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:755–764. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y. Regulatory T cells and infection: a dangerous necessity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:875–888. doi: 10.1038/nri2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag H B, Anand B, Richardson P, Rabeneck L. Association between hepatitis C infection and other infectious diseases: a case for targeted screening? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y, Piccirillo C A, Mendez S, Shevach E M, Sacks D L. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature. 2002;420:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nature01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S M, Fox B C, Brown P J, Worthington J, Fox S B, Chapman R W, Fleming K A, Banham A H, Klenerman P. Quantification and localization of FOXP3+ T lymphocytes and relation to hepatic inflammation during chronic HCV infection. J Hepatol. 2007;47:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N, Hiraoka N, Yamagami W, Ojima H, Kanai Y, Kosuge T, Nakajima A, Hirohashi S. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells affect the development and progression of hepatocarcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:902–911. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahnke K, Schönfeld K, Fondel S, Ring S, Karakhanova S, Wiedemeyer K, Bedke T, Johnson T S, Storn V, Schallenberg S, Enk A H. Depletion of CD4+CD25+ human regulatory T cells in vivo: kinetics of Treg depletion and alterations in immune functions in vivo and in vitro. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2723–2733. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D J, Ziegler S F. FOXP3 modifies the phenotypic and functional properties of regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:305–310. doi: 10.1038/nri2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthlott T, Moncrieffe H, Veldhoen M, Atkins C J, Christensen J, O'Garra A, Stockinger B. CD25+ CD4+ T cells compete with naive CD4+ T cells for IL-2 and exploit it for the induction of IL-10 production. Int Immunol. 2005;17:279–288. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen M, Moncrieffe H, Hocking R J, Atkins C J, Stockinger B. Modulation of dendritic cell function by naive and regulatory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:6202–6210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houot R, Perrot I, Garcia E, Durand I, Lebecque S. Human CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells modulate myeloid but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells activation. J Immunol. 2006;176:5293–5298. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro C E, Shakhar G, Shen S, Ding Y, Lino A C, Maraver A, Lafaille J J, Dustin M L. Regulatory T cells inhibit stable contacts between CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2006;203:505–511. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taams L S, van Amelsfort J M, Tiemessen M M, Jacobs K M, de Jong E C, Akbar A N, Bijlsma J W, Lafeber F P. Modulation of monocyte/macrophage function by human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemessen M M, Jagger A L, Evans H G, van Herwijnen M J, John S, Taams L S. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce alternative activation of human monocytes/macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19446–19451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706832104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio V L, Ballardini G, Artini M, Caratozzolo M, Bianchi F B, Levrero M. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules by Kupffer cells in chronic hepatitis of hepatitis C virus etiology. Hepatology. 1998;27:1600–1606. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]