Abstract

The α-amino acid ester prodrugs of the antitumor agent camptothecin and a more potent, lipophilic silatecan analog, DB-67, have been shown by NMR spectroscopy and quantitative kinetic analyses to undergo quantitative conversion to their pharmacologically active lactones via a non-enzymatic mechanism that at pH 7.4 is favored over direct hydrolysis. The alternate pathway involves the reversible intramolecular nucleophilic amine attack at the camptothecin E-ring carbonyl to generate a lactam (I) followed by a second intramolecular reaction to produce a bicyclic hemiorthoester (I′). The intermediates were isolated and shown to exist in an apparent equilibrium dominated by the hemiorthoester in DMSO using NMR spectroscopy. The conversion of prodrugs of camptothecin or DB-67 containing either α-NH2 or α-NHCH3 and their corresponding hemiorthoesters were monitored versus time in aqueous buffer (pH 3.0 and 7.4) at 37°C and the kinetic data were fit to a model based on the proposed mechanism. The results indicated that while the prodrugs are relatively stable at pH 3, facile lactone release occurs from both the prodrugs and their corresponding hemiorthoester intermediates under physiological conditions (pH 7.4). The glycinate esters and their hemiorthoesters were found to be more cytotoxic than the N-methylglycinates or their corresponding hemiorthoester intermediates in vitro using a human breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-435S), consistent with their more rapid conversion to active lactone. The pH dependence of the non-enzymatic pathway for conversion of these α-amino acid ester prodrugs suggests that they may be useful for tumor-targeting via liposomes, as they can be stabilized in an acidic environment in the core of liposomes and readily convert to the active lactone following their intratumoral release.

Introduction

The camptothecins are a class of S-phase specific antitumor agents that bind to the transient topoisomerase I-DNA complex during DNA replication, resulting in double strand breaks and cell death.1,2 Structure-activity relationships have demonstrated that the closed E-ring lactone and the 20-hydroxyl group in camptothecin (CPT, see Fig. 1 and Table 1) are critical for antitumor activity.1,3 However, at physiological pH, the E-ring lactone rapidly hydrolyzes in a reversible reaction to the inactive carboxylate form (Figure 1).4 In human blood and tissues, this equilibrium is shifted further toward the carboxylate form because of preferential binding of the carboxylate species to human serum albumin (HSA).5

Figure 1.

Reversible interconversion of CPT-lactone and carboxylate forms

Table 1.

Selected 13C and 1H NMR chemical shifts (ppm) for various α-amino acid esters of CPT and DB-67 and their corresponding hemiorthoesters (I′).

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

NMR assignment |

|

|

||

| Cmpd | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | C-17 | C-20 | C-22 | C-23 | H-17 | H-23 | OHa |

| 1 | H | H | H | H | 66.3 | 77.4 | 167.0 | 50.2 | 5.56 (s) | 4.08−4.39 (AB) | |

| I′-1 | - | H | H | H | 57.4 | 81.9 | 107.4 | 47.8 | 4.85−5.05 (AB) | 3.33−3.49 (ABX) | 7.93 |

| 2 | H | CH3 | H | H | 66.4 | 77.7 | 166.8 | 47.9 | 5.56 (s) | 4.30−4.47 (AB) | |

| I′-2 | - | CH3 | H | H | 57.4 | 82.0 | 107.1 | 54.8 | 4.83−5.06 (AB) | 3.41−3.72 (AB) | 8.06 |

| 3 | CH3 | CH3 | H | H | 66.4 | 78.0 | - | 50.3 | 5.57 (s) | 4.53−4.63 (AB) | |

| 4 | H | COCH3 | H | H | 67.0 | 77.4 | 167.2 | 41.5 | 5.40−5.70 (AB) | 4.15−4.45 (ABX) | |

| 5 | H | H | TBS | OH | 66.3 | 77.5 | 166.8 | 52.2 | 5.52 (s) | 4.10−4.31 (AB) | |

| I′-5 | - | H | TBS | OH | - | - | - | - | 4.73−5.12 (AB) | 3.28−3.48 (ABX) | 7.88 |

| 6 | H | CH3 | TBS | OH | 67.8 | 80.0 | - | 54.3 | 5.48−5.63 (AB) | 4.30−4.38 (AB) | |

| I′-6 | - | CH3 | TBS | OH | 57.3 | 82.0 | 107.0 | 52.0 | 4.73−5.11 (AB) | 3.41−3.69 (AB) | 7.96 |

22-Ortho hydroxyl group of I′

Recently, the highly lipophilic silatecan, 7-t-butyldimethylsilyl-10-hydroxy-camptothecin (DB-67, Table 1) has been found to display superior lactone stability in human blood when compared with the FDA approved camptothecins (topotecan and CPT-11) as well as several other camptothecins in clinical investigation.6 Due to the presence of the t-butyldimethylsilyl group, the lipophilicity of DB-67 is 250, 25- and 10-fold higher than topotecan, camptothecin and SN-38, respectively. Higher lipophilicity promotes incorporation into cellular and liposomal bilayers, while the 7-alkylsilyl and 10-hydroxy substituents in DB-67 reduce the association of the carboxylate form with the high affinity carboxylate binding site on HSA.7 DB-67 has also been shown to exhibit potent anti-topoisomerase I activity in vitro and antitumor activity in vivo in animal models.8,9

An interest in the use of liposome technology to enhance tumor targeting, prolong release, and thereby further improve the therapeutic index of this new generation of highly lipophilic and more potent camptothecin analogs represented by DB-67 led to the exploration of the prodrugs which are the topic of the present study.10 Liposomal formulations of amine-containing camptothecin analogues currently in preclinical or clinical trials (e.g., lurtotecan,11,12 topotecan,13 and irinotecan14) have been shown to provide significant increases in plasma residence time and plasma areas under the concentration-time curve (AUC) compared to free drug, consistent with a significant restriction in their distribution to normal tissue. These advantages in plasma retention translated into substantial increases in drug accumulation in tumor tissue, enhanced antitumor efficacy, and improved therapeutic index. On the other hand, retention data for liposomal formulations of SN-3815 or DB-67,16 neither of which contain an ionizable moiety, suggested minimal prolongation of drug levels in the circulation due to premature drug leakage from circulating liposomes prior to their localization in tumor tissue.

Certain 20-OR ω-aminoalkanoic acid ester prodrugs appear to exhibit features that make them suitable candidates for liposomal targeting. First, the ionizable amino group provides adequate aqueous solubility at low pH. Second, the basic amino enables efficient liposome loading in response to a transmembrane pH gradient along with liposomal retention at low pH for up to 40h.10 Third, despite the steric hindrance at the 20-position which inhibits enzymatic attack, the glycinate ester was found to undergo rapid decomposition both in pH 7.4 buffer and in human plasma and blood.10,17 A novel activation mechanism involving initial intramolecular nucleophilic attack by the amino group on the carbonyl carbon of the E-ring lactone was proposed to account for this unexpected reactivity.

The rate constants and pH dependence for the various reaction steps were heretofore unknown, so it was unclear whether or not prodrugs could be designed with adequate stability when entrapped in liposomes at low pH while providing adequate levels of the active lactone within a reasonable time frame upon exposure to a higher pH following their release from liposomes. To address these questions, we synthesized six 20(S)-α-amino acid ester prodrugs of CPT or DB-67, conducted detailed kinetic studies in aqueous solution at pH 3 and pH 7.4 on a selected subset of these compounds, and developed a quantitative kinetic model to support the postulated mechanism and to determine the rate constants for the key reaction steps involved. To improve the reliability of our rate constant estimates it was necessary to synthesize the corresponding hemiorthoester intermediates which form during prodrug hydrolysis and examine the reaction kinetics starting from either the prodrug or the hemiorthoester. 13C, 15N, and proton NMR were used to elucidate the structures of the hemiorthoesters and to establish the existence of an apparent equilibrium between the hemiorthoesters and their corresponding lactams formed from intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the amino pro-moiety on the lactone E-ring carbonyl. Finally, the cytotoxic activities of all compounds were determined.

Results

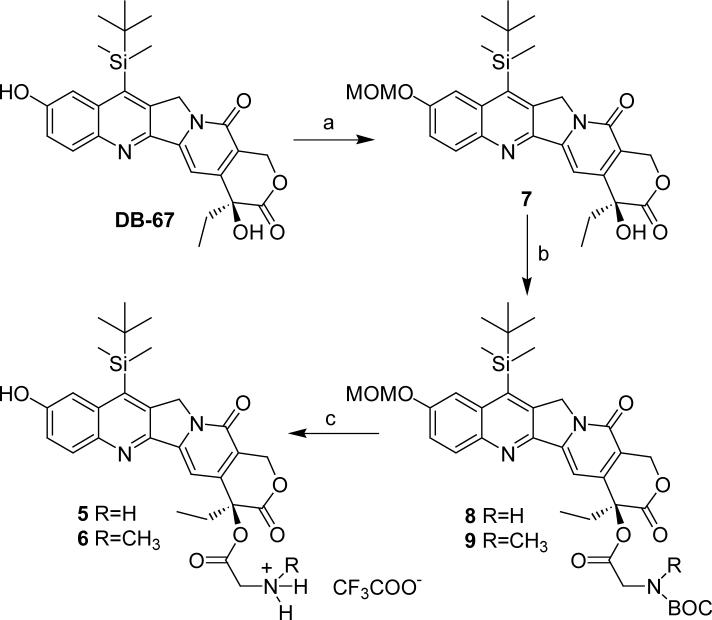

Synthesis

Four α-amino acid esters of CPT (1, 2, 3 and 4, Table 1) were synthesized according to the method reported previously for compound 1.18 The synthetic route for α-amino acid esters of DB-67 (5 and 6, Table 1) is illustrated in Scheme 1. Due to the sensitivity of CPT and DB-67 to alkaline hydrolysis, all synthetic reactions were performed under anhydrous conditions. A key step in the synthesis of DB-67 prodrugs was the selective protection the 10-hydroxyl group. While acetate was employed as the protecting group in the total synthesis of DB-67,6 the acetyl group and BOC protecting group on the amine couldn't be removed together in a single step. The additional reaction step and difficulties in purification arising from the generation of additional reaction products when the acetyl group was removed under basic conditions contributed to a low overall yield, necessitating exploration of alternate protecting groups, including methoxymethyl, 2-methoxyethoxymethyl, trimethylsilyl and t-butydimethylsilyl. Ultimately, the methoxymethyl group (MOM) was used to selectively protect the phenolic-OH in the presence of the hindered 20-OH. A solution of DB-67 in anhydrous dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) was treated with N,N′-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) followed by the addition of chloromethyl methyl ether (MOMCl) at 0 °C to give 10-MOM-DB-67 (7) in a yield of 84%. The acylation of DB-67 to produce compounds 8 and 9 in high yields was performed using 10-MOM protected DB-67 and BOC protected amino acids in the presence of N-ethyl-N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) and dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP). The MOM and BOC protective groups were removed simultaneously by trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in anhydrous dichloromethane to afford the trifluoroacetate salts of the DB-67 prodrugs in high yield.

Scheme 1.

aReagents and conditions: a. MOMCl, CH2Cl2, DIPEA, rt, overnight, 84%; b. BOC protected amino acid, EDCI, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt; c. TFA, CH2Cl2, 0−25 °C.

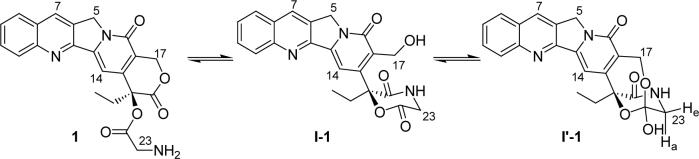

Chromatography and NMR Characterization of Reaction Intermediates I and I′

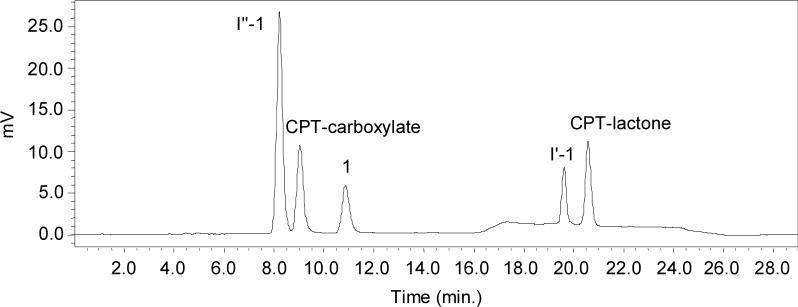

A previously described HPLC method afforded the separation of camptothecin-20(S)-glycinate from its hydrolysis products, but one of the intermediates formed in the reaction co-eluted with CPT-carboxylate.17 A method that resolved all reaction products was therefore developed for the kinetic studies described in this paper. A representative HPLC chromatogram for a partially hydrolyzed sample of 1 stored in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 2.5h is shown in Fig. 2. Intermediate I′ (the hemiorthoester, see structures in Table 1) formed initially, followed by a second intermediate (I″) which ultimately degraded to the CPT-lactone and CPT-carboxylate. These intermediates were not observed in the hydrolysis of camptothecin-20(S)-dimethylaminoacetate (3), which contains a tertiary amino group, or camptothecin-20(S)-N-acetylglycinate (4), in which the amino group is acetylated.

Figure 2.

Representative HPLC chromatogram for the hydrolysis of 1 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 2.5h. A linear gradient was employed as described in the methods section. Refer to Scheme 2 for compound structures.

Quantitative conversion of the prodrugs to intermediates (predominantly I′) was accomplished by adding triethylamine to solutions of each prodrug in anhydrous DMF. The structures of the primary intermediates produced were characterized by their mass spectra and 1H and 13C NMR spectra. Table 1 lists selected carbon and proton NMR signals of prodrugs 1, 2, 5, 6 and their corresponding I′ intermediates (I′-1, I′-2, I′-5, and I′-6, respectively). As shown, there are remarkable similarities among the four intermediates, suggesting that they have similar structures. Based on the similarities of the spectra for I′-1, I′-5, and I′-6 with that for I′-2, which has been previously characterized,10 the structure of the primary intermediate in each case appears to be the hemiorthoester.

In the proton spectra, notable differences are evident in the chemical shifts for peaks representing the H-23 and H-17 protons in the prodrug compared to the corresponding hemiorthoester. The signals for H-23 in 1 (δA 4.10 ppm, δB 4.36 ppm, JAB = 24 Hz) are shifted upfield ( δ 3.33 − 3.49 ppm) due to the conversion of the C-22 carbonyl carbon to a hemiorthoester carbon, while the H-17 singlet in 1 (δ 5.56, s, 2H) is shifted upfield and split to an AB spin system (δA4.85 ppm, δB5.05 ppm, JAB = 16.2 Hz) in the hemiorthoester because the two protons are becoming more magnetically nonequivalent after formation of the bicyclic intermediate.

The signal in the 13C NMR spectrum for C-22 at δ107 ppm in the intermediates I′ versus δ167 ppm in prodrugs is also indicative of a hemiorthoester carbon. This intermediate structure suggests an intramolecular nucleophilic attack by the 17-hydroxyl at the ester carbonyl to form a tetrahedral hemiorthoester intermediate (I′) (Scheme 2, step 2). In order to further provide support for the intramolecular attack at C-22, the 13C labeled hemiorthoester I′-1 was isolated from the reaction of 13C-22 labeled prodrug 1 in organic solvent under basic conditions. The 13C NMR spectrum for this compound indicated that the signal for the 13C-22-labeled carbon in the prodrug moved from †167.0 ppm to †107.4 ppm in I′-1.

Scheme 2.

Pathways for conversion of α-amino acid esters of camptothecins to their parent lactone and carboxylate forms

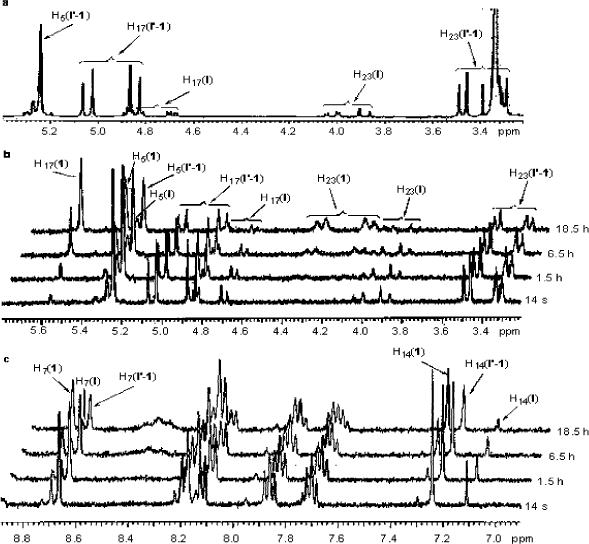

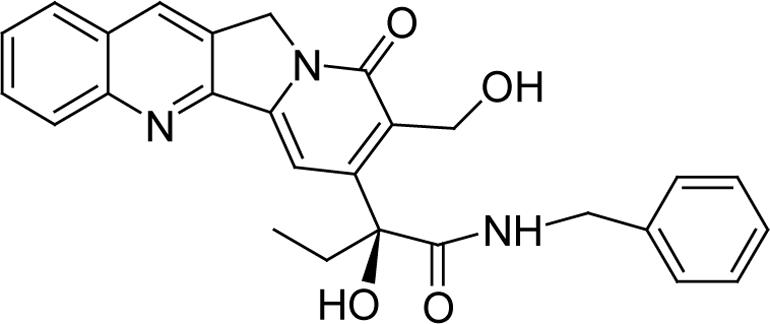

Although the predominant intermediates isolated and characterized by NMR were the hemiorthoesters (I′), an equilibrium appears to exist between I′ and the corresponding lactam (I). In all 1H and 13C NMR spectra of I′-1, I′-2, I′-5 and I′-6, two sets of signals could be detected, with signals for the hemiorthoester I′ predominating (ratio ∼ 4:1 for I′-1, ∼ 8:1 for I′-2), as illustrated in the proton spectrum in Fig. 3a. The H-17 signals (δA4.85 ppm, δB5.05 ppm, JAB = 16.2 Hz) in the hemiorthoester I′-1 are shifted upfield in the lactam intermediate, I-1, becoming an ABX system due to the adjacent hydroxyl. A portion of this ABX system is visible at δ4.67 − 4.71 ppm, changing to an AB system after addition of D2O (not shown) or TFA-d (as shown in Fig. 3b, 14 sec). This observation eliminates the possibility that the minor component in the intermediate mixture is the hemiorthoester formed by attack of the 17-hydroxyl on the 21-carbonyl carbon since then one would expect an AB spin system similar to hemiorthoester I′ in the presence or absence of D2O or TFA-d. In the literature,19 the chemical shift of the C-17 in the ring-opened CPT-benzyl amide (Fig. 4) was reported to be 55.6 ppm, close to the shift of 54.8ppm observed for the C-17 carbon in the lactam intermediate I-1. The complex second-order spin-spin coupling system (δ 3.86 − 4.05 ppm) in Fig. 3a is attributed to H-23 of the lactam I-1. The formation of lactam I-1 as an intermediate was additionally supported by preparing the 15N-labeled intermediates from the prodrug 1 synthesized using 15N-labeled glycine. In amino acids, the chemical shift for nitrogen is typically in the range of 40−50 ppm.20 In the 15N NMR spectrum for the intermediates formed from the 15N-labeled prodrug 1, two signals characteristic of amide nitrogens at about δ 95.9 ppm and δ97.76 ppm were observed at a ratio of 1 to 4. The minor signal at δ95.9 ppm split into two signals (at ∼ 94.75 ppm and 97.04 ppm) in the proton-coupled 15N NMR spectrum, indicating that there is a single proton on the nitrogen. This further supports the existence of an equilibrium between the lactam I and hemiorthoester I′.

Figure 3.

a, 1H NMR spectrum of I′-1 in DMSO-d6 at 25 °C. (Major signals were assigned to I′-1; minor signals were assigned to lactam I-1; δ 3.34 ppm is attributed to H2O in DMSO-d6); b, portion of 1H NMR spectrum showing changes in the H-5, H-17 and H-23 signals versus time after addition of a catalytic amount of TFA-d at 25 °C; c, portion of 1H NMR spectrum showing changes in the aromatic protons in DMSO–d6 after addition of a catalytic amount of TFA-d at 25 °C

Figure 4.

Structure of ring-opened CPT-benzyl amide

Figs. 3b and 3c clearly demonstrate that the hemiorthoester I′ and lactam I convert back to the prodrug after addition of a catalytic amount of TFA-d. The portions of the 1H NMR spectrum showing the H-5, H-17 and H-23 signals (Fig. 3b) and aromatic protons (Fig. 3c) of the hemiorthoester I′-1 and lactam I-1 change after addition of a catalytic amount of TFA-d at 25 °C, to a new spectrum identical to that of prodrug 1 with δ 5.56 ppm (s, H-17, Figure 3, b), δA 4.10 ppm and δB 4.36 ppm (H-23, JAB = 17.2, Figure 3, b), δ 7.30 ppm (s, H-14, Figure 3, c), and δ 8.73 ppm (s, H-12, Figure 3, c). Based on the above results, a modified mechanism for chemical decomposition of α-amino acid esters of camptothecins is presented (Scheme 2).

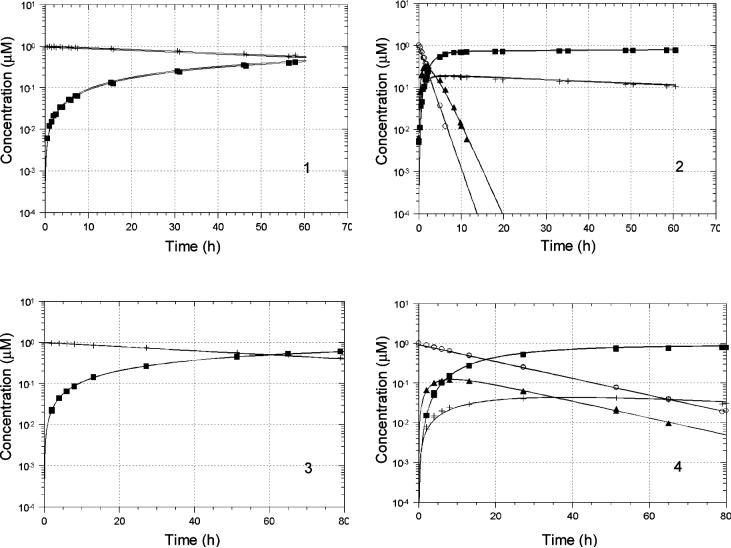

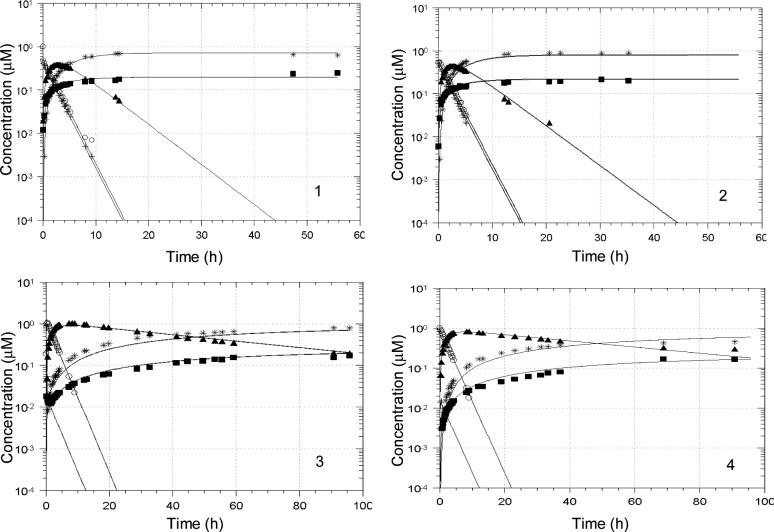

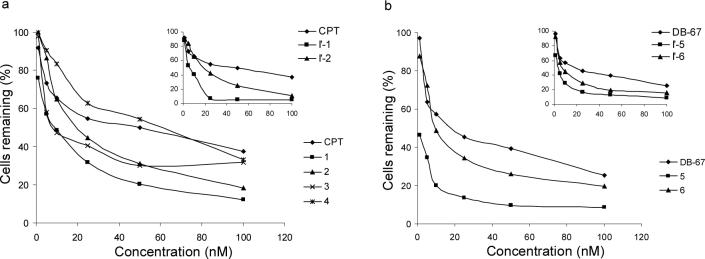

Kinetics of prodrug and hemiorthoester conversion in aqueous solution

The kinetics of conversion of prodrugs 1 and 2 as well as the hemiorthoesters I′-1 and I′-2 to their corresponding parent lactone and carboxylate forms were investigated in aqueous buffers at pH 3.0 and 7.4 and 37 °C . Concentrations of prodrug, hemiorthoester (I′), ring-opened amide (I″) (see Discussion for evidence of this structure), lactone (L) and carboxylate (C) (Scheme 2) were monitored versus time by HPLC starting from either the prodrug or the corresponding hemiorthoester I′. Based on the pathways in Scheme 2, a kinetic model was proposed and used to fit the experimental data (Eq. 1-6):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where CP is prodrug concentration, CTI is the total concentration of I and I′, CI2 is the concentration of the ring-opened amide intermediate I″, CL is the lactone concentration, and CC is the camptothecin carboxylate concentration. RF represents the fitted response factor for the ring-opened amide intermediate, as no reference standards were available for this species.

Since only a single peak was observed initially when the reaction was initiated with the hemiorthoester I′, the lactam I was assumed to be in rapid equilibrium with I′. Therefore, the peak generated from I′ standards in mobile phase was assumed to reflect the total I and I′ concentration (referred to as CTI in the kinetic model above). Two sets of experimental data starting from the prodrug and hemiorthoester I′, respectively, were combined and fit by computer to the model depicted in Scheme 2 (Eqs. 1-6) using nonlinear regression analysis. Concentration versus time profiles obtained at pH 3.0 and 7.4 are shown in Figs. 5 and 6 along with the results of the regression analyses (solid lines). The proposed kinetic model provided excellent fits to the experimental data at both pH values. Rate constants for each reaction step are listed in Table 2. k6 and k-6 were determined separately from kinetic studies of the hydrolysis of CPT-lactone and CPT-carboxylate at each pH. The values obtained are in agreement with literature values.4 The 95% confidence limits indicate that most of the rate constants could be obtained reliably by this procedure.

Figure 5.

Reactant and product concentration vs. time profiles for prodrug (left) or hemiorthoester (right) hydrolysis in PBS (pH 3.0) at 37 °C. Starting reactants were: 1, prodrug 1; 2, hemiorthoester I′-1; 3, prodrug 2; and 4, hemiorthoester I′-2. Solid lines represent the fitted parameters shown in Table 2. Symbols: + (1 or 2), ■ (CPT- lactone), ○ (I′-1 or I′-2), ▲ (I″-1 or I″-2).

Figure 6.

Reactant and product concentration vs. time profiles for prodrug (left) or hemiorthoester (right) hydrolysis in PBS (pH 7.4 at 37 °C. Starting reactants were: 1, prodrug 1; 2, hemiorthoester I′-1; 3, prodrug 2; and 4, hemiorthoester I′-2. Solid lines represent the fitted parameters shown in Table 2. Symbols: + (1 or 2), ■ (lactone), * (carboxylate), ○ (I′-1 or I′-2), ▲ (I″-1 or I″-2).

Table 2.

Calculated parameter values (± 95% confidence limits) for the rate constants and equilibrium constants depicted in Scheme 2 for the reactions of 1, 2, I′-1 and I′-2 at pH 3.0 or 7.4 and 37 °C

| Parameter value | pH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (h−1) | 3.0 | 7.4 | ||

| 1(I′-1) | 2(I′-2) | 1(I′-1) | 2(I′-2) | |

| k1 | 0a | 0a | 61.2 ± 60.2 | 14.5± 4.9 |

| k−1 | 0.2 ± 0.03 | 0.004 ± 0.0003 | 48a | 0.3a |

| Keq | 0 | 0 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 60.7 ± 16.7 |

| k3 | 0.5 ± 0.07 | 0.05 ± 0.002 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.05 |

| k4 | 0b | 0b | 0b | 0b |

| k5 | 0.5 ± 0.08 | 0.2 ± 0.03 | 0.2 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.004 |

| k6c | ∼0c | ∼0c | 1.39 | 1.39 |

| k−6c | NDc | NDc | 0.138 | 0.138 |

| k7 | 0.01 ± 0.002 | 0.01 ± 0.0005 | 0.3 ± 0.06 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| R2 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

Values were obtained from Keq = k1/k−1

k4 was initially included as a fitted parameter but the best fit value was always negligible and not significantly different from zero

k6 and k−6 were determined separately by monitoring the conversion of the lactone and carboxylate (at pH 3 reaction of the carboxylate was too rapid to measure and no conversion of the lactone to carboxylate could be detected)

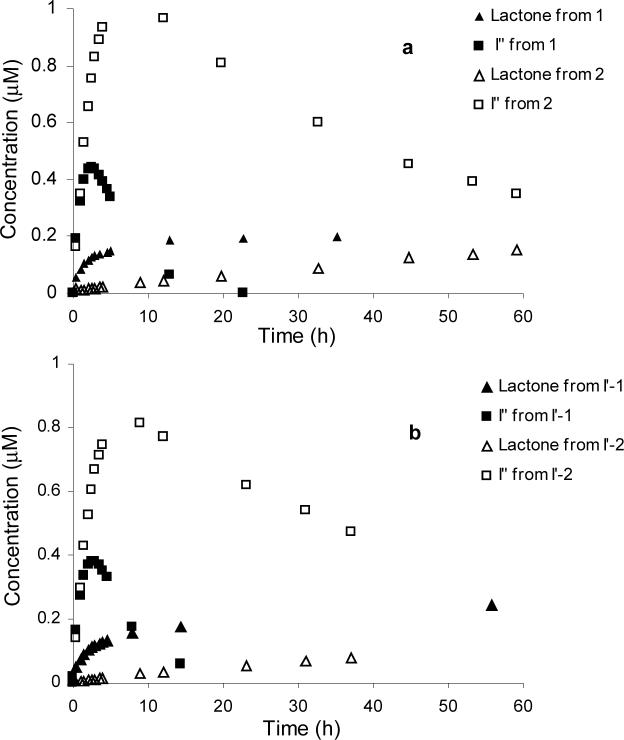

Cytotoxicity of prodrugs and hemiorthoesters (I′)

The apparent in vitro cytotoxicities of prodrugs 1−6, hemiorthoesters I′-1, I′-2, I′-5, and I′-6, and the corresponding parent lactones against MDA-MB-435 human breast cancer cells were compared 72 hours after drug application. Shown in Figure 7a and 7b are the % cells remaining 72 hrs after application versus the initial concentrations of drug or prodrug. Compounds 1, 5, I′-1 and I′-5 exhibited higher cytotoxicity than CPT, DB-67, 2, 6, I′-2 and I′-6 at each concentration. Much lower cytotoxicity was observed for prodrugs 3 and 4 which also undergo very slow hydrolysis.

Figure 7.

Percentage of MDA-MB-435 human breast cancer cells remaining in vitro 72 hours after drug, prodrug, or hemiorthoester application versus the initial concentrations applied. Compounds were: (a) CPT, CPT-prodrugs 1−4, and hemiorthoesters I′-1 and I′-2 (inserts); (b) DB-67, DB-67 prodrugs 5 and 6, and hemiorthoesters I′-5 and I′-6 (inserts)

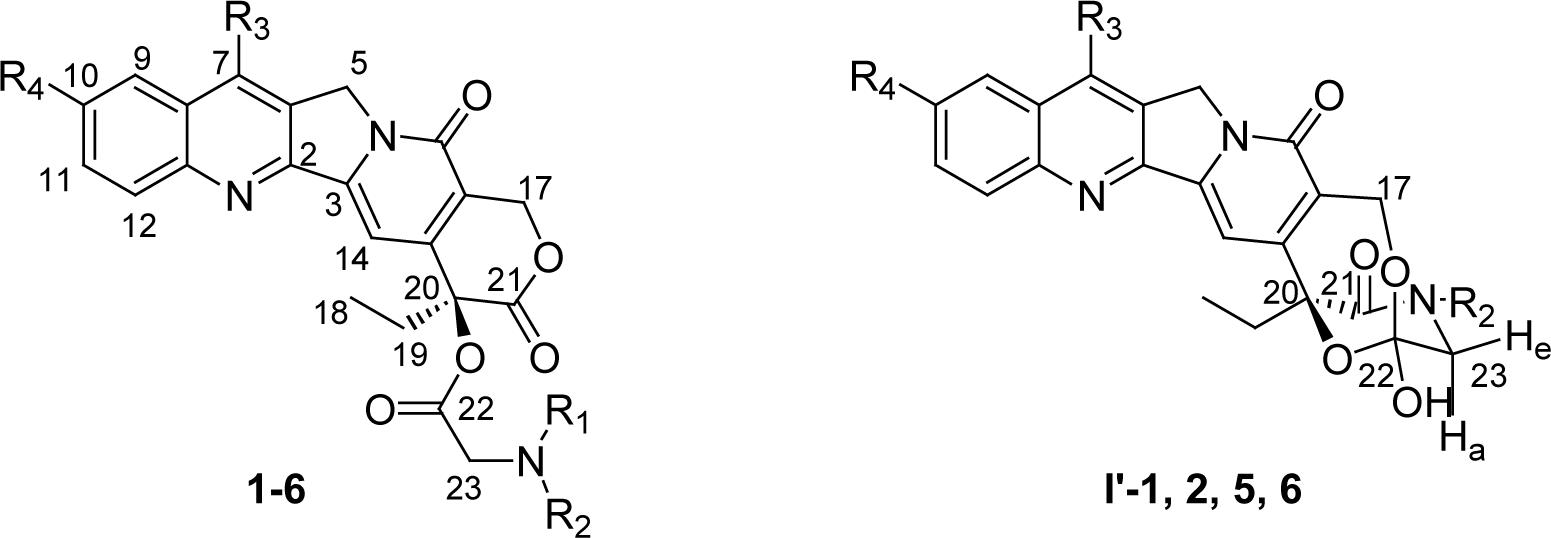

The greater apparent cytotoxicity of the glycinates of both CPT (prodrug 1) and DB-67 (prodrug 5) and their corresponding hemiorthoesters (I′-1 and I′-5) compared to the N-methylglycinate prodrugs (2 and 6) and hemiorthoesters (I′-2 and I′-6) may be accounted for by differences in the rates of conversion of their ring-opened amide intermediates (I″) to the active lactone forms. All of the self-activating α-amino acid ester prodrugs (1, 2, 5, and 6) were found to undergo rapid disappearance at pH 7.4 but the generation of lactone is delayed due to the build-up of an intermediate ring-opened amide (I″) prior to lactone generation. Figure 8a displays the concentration versus time profiles for CPT-lactone and the ring-opened amide intermediates (I″-1, and I″-2) formed after application of prodrugs 1 and 2 while Figure 8b displays the same concentration versus time profiles starting from the hemiorthoesters I′-1 and I′-2 over a 60 hr time frame at 37 °C. The glycinate prodrug and hemiorthoester (1 and I′-1) result in substantially higher lactone concentrations at earlier time points due to the more rapid hydrolysis of the unsubstituted amide (I″-1) in comparison to the N-methyl substituted amide intermediate I″-2.

Figure 8.

Plots of CPT-lactone and ring-opened amide intermediate (I″) concentrations versus incubation time at pH 7.4. Panel (a): CPT-lactone and I″ (I″-1 or I″-2) concentrations generated from prodrugs 1 or 2; Panel (b): CPT-lactone and I″ (I″-1 or I″-2) concentrations generated from the hemiorthoesters I′-1 or I′-2.

Discussion

Products of prodrug and hemiorthoester hydrolysis at pH 3.0 and pH 7.4

Esterification of the 20-hydroxyl group has long been considered as a potential avenue to modify water solubility and other delivery-related properties of the camptothecins.21-26 However, the resulting esters are highly sterically hindered and thus pro-moiety removal by enzymatic attack at the ester linkage is unlikely. Chemical (i.e., non-enzymatic) conversion may also be quite slow. Liu et al.17 reported that CPT-20(S)-acetate was resistant to hydrolysis in aqueous solutions at physiological pH, with negligible hydrolysis for days. On the other hand, Wadkins et al.27 previously observed that the 20(S)-glycinate esters of 10,11-methylenedioxycamptothecins underwent facile chemical hydrolysis at pH 7.5 in the absence of enzymes to produce active drug but the mechanism of this conversion was not addressed. The enhanced reactivity of α-amino acid ester prodrugs can generally be attributed to electronic activation by the positively charged amino terminus at pH values below its pKa.28,29 However, recent studies have provided evidence for an alternative route which may facilitate the generation of the active lactone from amino acid ester prodrugs of CPTs.10, 17

Herein we report the results of detailed kinetic studies of a selected set of 20(S)-α-amino acid ester prodrugs of CPT or DB-67 in aqueous solution at pH 3 and pH 7.4. We developed a quantitative kinetic model to support the postulated mechanism and to determine the rate constants for the key reaction steps involved. The reaction pathways governing the hydrolytic conversion of prodrugs (1, 2, 5, and 6) or their corresponding hemiorthoesters (I′-1, I′-2, I′-5 and I′-6) to their ultimate products (i.e., the lactone and ring-opened carboxylate) are depicted in Scheme 2. At pH 3.0, the favored route for prodrug conversion to CPT- or DB-67-lactone is direct hydrolysis since protonation of the amine precludes intramolecular nucleophilic attack. At physiological pH (pH 7.4), however, the degradation of α-amino acid ester-containing prodrugs is complex, leading to several products that are not detected at pH 3, as shown by the chromatogram obtained during the degradation of the CPT-20(S)-glycinate (Figure 2). In addition to the CPT-lactone and CPT-carboxylate, two additional peaks corresponding to the hemiorthoester (I′) and the ring-opened amide intermediate I″ were observed. As illustrated in Scheme 2, the reaction is initiated by an intramolecular nucleophilic attack by the terminal amino group on the lactone (C-21) carbonyl to form the lactam intermediate (I) which is in apparent equilibrium with the hemiorthoester (I′) formed by a second intramolecular attack of the 17-hydroxyl at the 22-carbonyl carbon in the lactam intermediate (I). Previous evidence supporting the structure of the hemiorthoester (I′) was provided by HPLC with electrospray ionization-mass spectral determination of the protonated molecular ion, which generated an m/z of 406.17 The NMR data generated in the present study were consistent with the identification of I′ as a hemiorthoester and established the reversibility in the reaction between I′ and prodrug. Usually, tetrahedral intermediates containing three heteroatoms are unstable and transient, but the NMR data for the intermediates generated in DMSO indicated a predominance of hemiorthoester (I′) over lactam (I) by a 4:1 ratio. The extended bicyclic framework may act as a thermodynamic trap to enhance stability of this usually very reactive intermediate.30

In a previous investigation of the hydrolysis of the glycinate ester of CPT by LC-MS/MS, a second intermediate having an apparent molecular weight of 423 co-eluted with the CPT-carboxylate.17 As shown in Figure 2, this intermediate (I″-1) was resolved from the CPT-carboxylate using the chromatographic method employed in the present study. Three possible structures are shown for this intermediate in Figure 9 based on commonly accepted mechanisms for hemiorthoester breakdown.31-33 Hemiorthoester I′ can undergo C22–O20 bond cleavage to form the 9-membered E-ring (which would have a molecular weight of 405 rather than 423) or C22–O17 bond cleavage to form the intermediate lactam (I). Intramolecular attack by the 17-OH at the C21-carbonyl of the lactam results in reconversion to prodrug whereas hydrolysis at this position would generate the E-ring opened glycinate. Alternatively, water attack at the C22-carbonyl will generate the E-ring opened glycinamide. The similarity in HPLC retention times of I″ and the CPT-carboxylate (Figure 2), indicated that I″ is a highly polar compound like the CPT-carboxylate, which, along with the molecular weight difference, eliminates the 9-membered E-ring as a plausible structure. Evidently, the breakdown of the hemiorthoester is subject to stereoelectronic control (Deslongchamps effects), which favors C22–O17 bond cleavage because the hydroxyl oxygen and ester oxygen each have an orbital oriented antiperiplanar to this bond.34-36

Figure 9.

Possible structures of I″

The E-ring opened glycinate and E-ring opened glycinamide have the same molecular weight in their neutral forms. Adamovices et al observed that E-ring opened amide derivatives of camptothecin undergo transformation in dilute solution to the parent lactone by 17-hydroxyl attack on the 21-amide bond.37 This is consistent with our observations, but does not eliminate the possible existence of the E-ring opened glycinate, which may undergo ester hydrolysis followed by rapid ring closure to also generate the parent lactone. However, rapid closure of the E-ring in the glycinate would also be expected at low pH even in the absence of ester hydrolysis. To explore this possibility, the prodrugs 1 or 2 were incubated in a buffer (PBS, pH 6.8±0.1) at 37 °C until only I″, CPT-carboxylate and CPT-lactone were detected by HPLC. Then the pH of the mixtures was adjusted to 3.0 at room temperature. Only CPT-lactone was observed (no prodrug), establishing the structure of I″ to be the E-ring opened glycinamide. Moreover, the ∼10-fold slower conversion of the intermediate to CPT-lactone when the amide nitrogen is N-methylated (I″-2 versus I″-1), suggests that the intermediate I″ is the E-ring opened glycinamide since N-methylation would not have been expected to have such a profound effect on the reactivity of the E-ring-opened glycine ester.

Kinetics of various reaction steps in the conversion of prodrugs and hemiorthoesters

Direct ester hydrolysis (k7)

As illustrated in Table 2 and Figs. 5 and 6, both prodrugs 1 and 2 undergo classical conversion to the parent camptothecins via direct ester hydrolysis with no apparent difference in k7 with N-methyl substitution. At pH 3.0 this pathway is dominant (Fig. 5), with no evidence for formation of intermediates I′ or I″ (i.e., k1 = 0), and therefore no need to invoke an intramolecular activation pathway to account for the kinetics of prodrug conversion. Direct hydrolysis of 1 and 2 is, however, quite slow at pH 3.0, with t1/2 = 69 h. Stability at low pH is a desirable feature if the prodrugs are to be encapsulated into liposomes for passive (or active) tumor targeting, which would most likely employ a low intraliposomal pH to ensure prolonged prodrug retention within the liposomes in the circulation after their administration.

The values of k7 for the direct hydrolysis at pH 7.4 are 30−40 times greater than at pH 3.0 consistent with base catalysis of the reaction at pH 7.4, enhanced by electron withdrawal by the protonated terminal amino substituent. In the absence of an alternative intramolecular route for generation of parent lactone from prodrugs 1 and 2, the rate constant for direct hydrolysis would appear to be adequate, with t1/2 ≈ 2 h.

Reversible prodrug and hemiorthoester formation (k1 and k−1)

At pH 7.4 (Table 2 and Fig. 6), intramolecular nucleophilic attack at the E-ring lactone carbonyl carbon by the glycine or N-methyl glycine amino dominates over direct hydrolysis to CPT-lactone (k1 > k7) leading to the diversion of a significant fraction of prodrug to this alternate pathway and resulting in the formation of multiple reaction intermediates prior to the ultimate generation of the parent camptothecin lactone and carboxylate. N-methyl substitution now plays a crucial role in the rate constant for lactone regeneration. Whereas the t1/2 for formation of lactone from 1 (∼ 2 h) is not greatly affected by this alternate route, t1/2 for the production of lactone from 2 is increased substantially (Fig. 6) due to the stability of the N-methylglycine amide intermediate (I″-2). Nearly identical concentration versus time profiles are obtained at pH 7.4 starting from prodrug or hemiorthoester (I′), indicating that equilibrium is rapidly established between the prodrug, hemiorthoester (I′) and lactam (I) intermediates at pH 7.4. As discussed previously, protonation of the glycine or N-methylglycine amino residue effectively prevents the intramolecular attack to form lactam and hemiorthoester intermediates. At pH 3, Keq = k1/k−1 = 0 for both 1 and 2 (Table 2), indicating that formation of prodrug from I′ is essentially irreversible at pH 3.0. When hemiorthoester was the starting reactant at pH 3.0 (Fig. 5, right panels), only a small fraction reverted to prodrug while most of the hemiorthoester was converted to the corresponding E-ring opened glycineamide (I″). N-methyl substitution significantly reduced k−1 at pH 3.0 and pH 7.4, presumably due to steric crowding in the transition state.

E-ring opened glycineamide formation (k3) and conversion to lactone (k5)

Since k3 was found to be similar to or less than k5 at pH 3.0 for both I′-1 and I′-2, I″ did not build-up to high concentrations in either case. N-methyl substitution suppressed both the conversion from I′ to I″ (k3) and lactone generation from the glycineamide intermediate I″ (k5). While reduction of amide hydrolysis upon N-methyl substitution was expected, this suppression was less than the effect of an N-methyl on the lactone hydrolysis involved in I″ formation. This may be related to the finding that the ratio of hemiorthoester I′ to lactam I in the N-methyl substituted intermediates I′-2 and I′-6 was higher than in I′-1 and I′-5 (results not shown).

The rate constant (k3 for conversion of the hemiorthoester (I′)/lactam (I) to the E-ring opened glycineamide intermediate (I″) was increased at pH 7.4 relative to pH 3.0 while the rate constant for hydrolysis of I″ was decreased, particularly with N-methyl substitution (Table 2). Most importantly, k5 is 20-fold less than k3 in 2 (I″-2) and, since Keq heavily favors formation of the hemiorthoester and lactam intermediates over prodrug, I″-2 accumulates. The accumulation of I″-2 impedes rather than facilitates prodrug conversion to CPT-lactone because of the slow k5 step which traps prodrug 2 as I″-2.

Formation of lactone at physiological pH 7.4 and cytotoxic activity

Figure 8 illustrates more clearly the significance of N-methyl substitution in the regeneration of CPT-lactone from prodrugs 1 or 2. Both direct prodrug hydrolysis and glycineamide intermediate (I″) hydrolysis contribute to the generation of CPT-lactone. As seen by the values of k7 (Scheme 2 and Table 2), direct prodrug hydrolysis does not vary substantially with or without N-methyl substitution (k7 = 0.3 h−1 for 1, 0.4 h−1 for 2). Yet, as shown in Fig. 8, prodrug 1 (or hemiorthoester I′-1) provides significantly elevated lactone levels compared to prodrug 2 (or hemiorthoester I′-2), particularly over the first 24 hours. The difference lies in the rates of various steps along the intramolecular nucleophilic pathway, which accelerates prodrug elimination at pH 7.4 but does not necessarily lead to more rapid lactone production. The pathway involving intramolecular attack of the glycinate amino group in prodrug 1 has little influence on the rate of lactone generation because both pathways produce lactone at comparable rates. However, k5 for I″-1 is 10 times higher than that I″-2, resulting in accumulation of I″-2 and slow CPT-lactone formation from prodrug 2. The above results indicate that the CPTs can be released nonenzymatically from both the glycinate and N-methyl glycinate ester prodrugs, albeit at significantly different rates due to the effects of N-methylation on hydrolysis of the last intermediate along the preferred pathway for conversion.

The greater cytotoxicities of the glycinate esters (1 and 5) and their corresponding hemiorthoesters I′-1 and I′-5) in comparison to the N-methyl substituted glycinate esters (2 and 6) and their corresponding hemiorthoesters (I′-2 and I′-6) (Fig. 7) are qualitatively consistent with their relative rates of generation of the active CPT and DB-67 lactones at pH 7.4. The greater cytotoxicities of prodrug compared to the parent CPT or DB67 may reflect differences in the intracellular active lactone concentration versus time course depending on the compound administered. However, cytotoxicity is also likely to depend on the cell uptake of the prodrugs and the various reaction intermediates, some of which may be substrates for carriers or efflux transporters. Moreover, the rates of the various reaction steps may be altered in the presence of cells due to the effects of lipid or protein binding and enzyme catalysis of various reaction steps. Further studies would be necessary to determine the intracellular lactone concentration versus time course which we expect is a key determinant of cytoxicity.

Summary

Through the isolation of the intermediates resulting from intramolecular nucleophilic amine attack on the E-ring lactone carbonyl in α-amino acid esters of CPT and DB-67 and analysis of their NMR spectra, we have characterized their structures as hemiorthoesters (I′) and lactams (I) which appear to exist in equilibrium, with the hemiorthoesters predominating. Quantitative kinetic studies, in which both reactant and product concentrations were monitored versus time, enabled the determination of the rate constants for various reaction steps, and provided an explanation for the significant decreases in the rates of lactone generation upon N-methylation of the glycinate esters. Close agreement between the kinetic model based on the proposed mechanism and the experimental points provides further support for the mechanism as described. Cytotoxicity data suggest that the glycinate esters are more potent in vitro than the N-methyl glycinates, consistent with their more rapid conversion to the active lactone.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

(S)-(+)-Camptothecin (95%) was purchased form Sigma (St. Louis, MO). 20(S)-7-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (DB-67) was obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). Triethylamine and HPLC-grade acetonitrile were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). All other reagents and solvents were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). All purchased reagents were used without further purification. High purity water was provided by a Milli-Q UV Plus purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Flash column chromatography was carried out using ICN SiliTech 32−63, 60Å silica gel (ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Irvine, CA). Preparative TLC was conducted on silica gel GF plates (Analtech, Newark, DE) and TLC analysis was conducted on glass precoated with silica gel 60 F254 (EMD Chemicals Inc., Gibbstown, NJ). Apparent purity was measured by HPLC (Waters Alliance 2690) with a scanning fluorescence detector (Waters 474) and PDA UV detector (Waters 996). 1H and 13CNMR spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6, CDCl3 or CD3OD on a Varian 400 MHz or 300 MHz instrument. 15N NMR spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6 on a Varian 400 MHz instrument. Signals of solvents were used as internal references. Chemical shifts (δ values) and coupling constants (J values) are given in ppm and Hz, respectively. Mass spectra were recorded on a JEOL JMS-700T MStation or on a Bruker Autoflex MALDI-TOF MS. Compound 2, 3, and 4 were synthesized following the method reported for compound 1.18 The same method was employed in the synthesis 13C and 15N-labeled 1, in which commercially available carbonyl carbon 13C-labeled glycine (glycine-1-13C, 99 atom % 13C) and 15N-labeled glycine (98+ atom %) were used.

Camptothecin-20(S)-N-methylglycinate, TFA salt (2)

Purity > 95% (HPLC); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 0.96 (t, J = 7.2, 3H, H-18), 2.10−2.22 (m, 2H, H-19), 2.61 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 4.30 (A of AB system, JAB = 17.6, 1H, H-23A), 4.47 (B of AB system, JAB = 17.6, 1H, H-23B), 5.31 (A of AB system, JAB = 19.8, 1H, H-5A), 5.33 (B of AB system, JAB = 19.8, 1H, H-5B), 5.56 (s, 2H, H-17), 7.27 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.74 (t, J = 7.6, 1H, H-10), 7.88 (t, J = 7.6, 1H, H-11), 8.15 (d, J = 9.6, 2H, H-9, 12), 8.73 (s, 1H, H-7), 9.15 (br s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.56, 30.13, 32.53, 47.88, 50.31, 66.39, 77.71, 95.30, 118.85, 127.84, 128.04, 128.67, 128.78, 129.83, 130.60, 131.75, 144.58, 146.17, 147.90, 152.33, 156.50, 166.10, 166.82; MS (MALDI/LDI) m/z: 533(M+)

Camptothecin-20(S)-N,N-dimethylglycinate, TFA salt (3)

Purity > 95% (HPLC); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 0.97 (t, J = 7.6, 3H, H-18), 2.15−2.25 (m, 2H, H-19), 2.84 (s, 6H, N(CH2)2), 4.53 (A of AB system, JAB = 17.2, 1H, H-23A), 4.63 (B of AB system, JAB = 17.2, 1H, H-23B), 5.27−5.38 (AB system, 2H, H-5), 5.57 (s, 2H, H-17), 7.23 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.74 (t, J = 7.6, 1H, H-10), 7.86−7.90 (m, 1H, H-11), 8.15 (d, J = 9.2, 2H, H-9, 12), 8.72 (s, 1H, H-7); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.56, 30.01, 43.21, 50.33, 55.97, 66.44, 77.97, 95.01, 118.73, 127.84, 128.05, 128.65, 128.79, 129.87, 130.57, 131.71, 144.53, 146.29, 147.91, 152.34, 156.49, 165.54, 166.92; MS (MALDI/LDI) m/z (%): 548 (M++H).

Camptothecin-20(S)-N-acetylglycinate (4)

Purity > 95% (HPLC); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.99 (t, J = 7.6, 3H, H-18), 2.00 (s, 3H, NCO(CH3)), 2.18−2.35 (m, 2H, H-19), 4.15 (A of ABX system, JAB = 19.0, JAX = 6.0, 1H, H-23A), 4.45 (B of ABX system, JAB = 19.0, JBX = 4.0, 1H, H-23B), 5.28 (A of AB system, JAB = 14.8, 1H, H-5A), 5.30 (B of AB system, JAB = 14.8, 1H, H-5B), 5.40 (A of AB system, JAB = 17.2, 1H, H-17A), 5.70 (B of AB system, JAB = 17.2, 1H, H-17B), 7.24 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.68 (t, J = 7.6, 1H, H-10), 7.85 (t, J = 7.6, 1H, H-11), 7.94 (d, J = 8.0, 1H, H-9), 8.25 (d, J = 8.4, 1H, H-12), 8.40 (s, 1H, H-7); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.89, 23.21, 32.08, 41.50, 50.26, 67.41, 96.03, 120.19, 128.27, 128.48, 129.88, 130.85, 131.29, 145.37, 146.69, 148.97, 152.23, 157.35, 167.19, 169.38, 170.11; MS (MALDI/TOF) m/z: 447 (M+)

10-Methoxymethyl-DB-67 (7)

To a solution of DB-67 (100 mg, 0.21 mmol) in 10 mL of CH2Cl2 at room temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere was added DIPEA (0.2 mL, 1.14 mmol). After stirring 10 min., chloromethyl methyl ether (MOMCl) (0.08 mL, 1.05 mmol) was added to the mixture. The mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight, diluted with CH2Cl2, washed with water, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under vacuum. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (CH2Cl2-CH3COCH3, 95:5, v/v) to afford the title compound 7 (92 mg, 84%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.70 (s, 6H, Si(CH3)2), 1.00 (s, 9H, Si[C(CH3)3]), 1.04 (t, J = 7.2, 3H, H-18), 1.90 (m, 2H, H-19), 3.54 (s, 3H, CH3OCH2O), 5.28−5.32 (m, 5H, H-5, H-17A, CH3OCH2O), 5.75 (B of AB system, JAB = 18.4, 1H, H-17B), 7.45−7.48 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.8, 1H, H-9), 7.62 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.91 (d, J = 2.8, 1H, H-11), 8.11 (d, J = 9.2, 1H, H-12); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ −0.75, −0.70, 8.04, 19.64, 27.30, 31.80, 52.66, 56.09, 66.57, 73.02, 95.03, 97.30, 112.11, 117.86, 123.18, 132.04, 134.28, 136.70, 141.63, 144.65, 146.96, 149.19, 150.41, 156.23, 157.70, 174.27; MS (EI) m/z: 523 (M++H).

General procedure for synthesis of DB-67 esters

A solution of 7 (1 eq.), N-tert-butoxycarbonylamino acid (3 eq.) and DMAP (0.6 eq.) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 was cooled to 0°C, followed by the addition of EDCI (3 eq.). The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred overnight. The resulting solution was washed with HCl (0.1 N) and water, then extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under vacuum. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to afford the corresponding protected compound (8 or 9), which was then dissolved in CH2Cl2 and treated with 1 molar equivalent of TFA at room temperature for 0.5−2 h (monitored by TLC). Solvents were removed under vacuum and the title compounds 5 or 6 were recrystallized from MeOH-CH2Cl2.

10-Methoxymethyl-DB-67−20(S)-N-tert-butoxycarbonylglycinate(8)

Yield 90%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.68 (s, 6H, Si(CH3)2), 0.97−1.00 (m, 12H, Si[C(CH3)3], H-18 ), 1.41 (s, 9H, BOC), 2.10−2.34 (m, 2H, H-19), 3.54 (s, 3H, CH3OCH2O), 4.02−4.25 (ABX system, 2H, H-23), 5.22 (m, 4H, H-5, CH3OCH2O), 5.39 (A of AB system, JAB = 17.2, 1H, H-17A), 5.69 (B of AB system, JAB = 17.2, 1H, H-17B), 7.22 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.48−7.51 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.4, 1H, H-9), 7.92 (d, J = 2.4, 1H, H-11), 8.14 (d, J = 9.2, 1H, H-12); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ −0.58, 7.88, 19.72, 27.38, 28.54, 32.04, 42.64, 52.60, 56.15, 67.39, 77.05, 80.34, 95.01, 95.41, 112.05, 119.20, 123.20, 131.81, 134.24, 136.44, 141.66, 144.41, 145.58, 146.78, 148.82, 155.53, 156.12, 157.21, 167.37, 169.52;

DB-67−20(S)-glycinate, TFA salt (5)

Yield 62%; Purity > 95% (HPLC); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 0.66 (s, 6H, Si(CH3)2), 0.92−0.96 (m, 12H, Si[C(CH3)3], H-18), 2.10−2.22 (m, 2H, H-19), 4.10 (A of AB system, JAB = 15.8, 1H, H-23A), 4.31 (B of AB system, JAB = 15.8, 1H, H-23B), 5.22 (A of AB system, JAB = 18.8, 1H, H-5A), 5.26 (B of AB system, JAB = 18.8, 1H, H-5B), 5.52 (s, 2H, H-17), 7.16 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.38−7.41 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.4, 1H, H-9), 7.57 (d, J = 2.4, 1H, H-11), 8.01 (d, 1H, J = 9.2, H-12), 8.36 (br s, 3H, NH3+), 10.49 (s, 1H, 10-OH); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO- d6): δ −0.95, 7.53, 7.71, 18.92, 27.12, 27.30, 30.22, 52.24, 66.31, 77.52, 94.00, 110.67, 117.55, 131.23, 133.84, 136.99, 138.69, 142.08, 144.61, 146.22, 147.48, 156.09, 156.20, 166.69, 166.75; MS (MALDI/LDI) m/z: 536 (M+-CF3COOH).

10-Methoxymethyl-DB-67−20(S)-N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-N-methylglycinate (9)

Yield 90%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.70 (s, 6H, Si(CH3)2 ), 1.01 (m, 12H, Si[C(CH3)3], H-18), 1.45 (d, J = 4.8, 9H, BOC), 2.10−2.34 (m, 2H, H-19), 2.96 (s, 3H, H-24), 3.54 (s, 3H, CH3OCH2O), 4.05−4.31 (ABX system, 2H, H-23), 5.27−5.32 (m, 4H, H-5, CH3OCH2O), 5.40 (A of AB system, JAB = 17.2, 1H, H-17A), 5.70 (B of AB system, JAB = 17.2, 1H, H-17B), 7.22 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.46−7.51 (m, 1H, H-9), 7.91−7.94 (dd, J = 6.4, 2.4, 1H, H-11), 8.06 (d, J = 9.2, 1H, H-12); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ −0.79, 7.74, 19.55, 27.23, 28.43, 31.87, 35.60, 50.38, 50.83, 52.49, 56.08, 67.23, 76.84, 94.91, 95.75, 112.08, 118.96, 119.16, 123.14, 131.69, 131.99, 134.24, 136.48, 141.43, 141.71, 144.49, 145.97, 146.85, 148.86, 149.05, 155.41, 156.21, 157.31, 167.33, 167.66, 169.15, 169.41.

DB-67−20(S)-N-methylglycinate, TFA salt (6)

Yield 90%; Purity > 95% (HPLC); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 0.73 (s, 6H, si(CH3)2 ), 1.02 (s, 9H, si[C(CH3)3]), 1.08 (t, J = 7.2, 3H, H-18), 2.18−2.35 (m, 2H, H-19), 2.75 (S, 3H, H-24), 4.30 (A of AB system, JAB = 17.4, 1H, H-23A), 4.38 (A of AB system, JAB = 17.4, 1H, H-23B), 5.35 (s, 2H, H-5), 5.48 (A of AB system, JAB = 16.8, 1H, H-17A), 5.63 (B of AB system, JAB = 16.8, 1H, H-17B), 7.34 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.42−7.45 (dd, J = 9.2, 1.2, 1H, H-9), 7.67 (d, J = 2.8, 1H, H-11), 8.19 (d, J = 9.2, 1H, H-12); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD3OD): δ −0.42, 8.22, 20.30, 27.91, 31.98, 33.65, 54.30, 67.84, 80.04, 96.59, 112.46, 119.31, 123.90, 132.22, 136.12, 138.29, 142.07, 144.02, 147.50, 148.27, 148.62, 158.20, 158.81; MS (MALDI/LDI) m/z : 551 (M+-CF3COOH).

General procedure for the isolation of intermediates(I and I′)

To a solution of compound 1, 2, 5, or 6 (50mg) in anhydrous DMF (6 mL) was added 1.5 molar equivalents of triethylamine at room temperature. The reaction was monitored by HPLC. After prodrugs completely disappeared, solvents were evaporated under vacuum at room temperature. The residues were washed with diethyl ether to give the expected intermediates (i.e., predominantly I′).

I′-1 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 0.93 (t, J = 7.2, 3H, H-18), 2.02−2.40 (m, 2H, H-19), 3.33−3.49 (m, 2H, H-23), 4.85 (A of AB system, JAB = 16.2, H-17A), 5.05 (B of AB system, JAB = 16.2, H-17B), 5.22 (s, 2H, H-5), 7.23 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.67−7.71 (m, 1H, H-10), 7.83−7.87 (m, 1H, H-11), 7.93 (s, 1H, 22-OH), 8.09−8.20 (m, 2H, H-9, H-12), 8.64 (s, 1H, H-7); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.96, 32.62, 45.72, 47.88, 49.97, 57.35, 81.85, 100.23, 107.44, 127.29, 127.67, 128.08, 128.30, 128.78, 129.60, 130.11, 131.27, 142.38, 147.68, 150.46, 152.52, 158.55, 167.93; MS (FAB) m/z: 406 (M + H).

I′-5: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 0.64 (s, 6H, Si(CH3)2), 0.94−1.02 (m, 12H, Si[C(CH3)3], H-18), 2.00 − 2.38 (m, 2H, H-19), 3.28 − 3.48 (m, 2H, H-23), 4.73 (A of AB system, JAB = 15.8, 1H, H-17A), 5.12 (B of AB system, JAB = 15.8, 1H, H-17B), 5.17 (s, 2H, H-5), 7.13 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.36 − 7.40 (m, 1H, H-9), 7.55−7.56 (m, 1H, H-11), 7.88 (s, 1H, 22-OH), 8.15 (d, J = 4.4, 1H, H-12), 10.31 (s, 1H, 10-OH); MS (MALDI/TOF) m/z : 536 (M+ + H)

I′-6: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 0.64 (s, 6H, Si(CH3)2), 0.90 −0.95 (m, 12H, Si[C(CH3)3, H-18), 2.00−2.40 (m, 2H, H-19), 3.41 (A of AB system, JAB = 12.6, 1H, H-23A), 3.69 (B of AB system, JAB = 12.6, 1H, H-23B), 4.73 (A of AB system, JAB = 16.0, 1H, H-17A), 5.11 (B of AB system, JAB = 16.0, 1H, H-17B), 5.15 (A of AB system, JAB = 19.0, 1H, H-5A), 5.17 (B of AB system, JAB = 19.0, 1H, H-5B), 7.16 (s, 1H, H-14), 7.36−4.39 (dd, J = 9.6, 2.4, 1H, H-9), 7.56 (d, J = 2.8, 1H, H-11), 7.96 (s, 1H, 22-OH), 8.04 (d, J = 8.8, 1H, H-12), 10.31 (s, 1H, 10-OH); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): −1.02, 7.97, 18.90, 27.18, 33.18, 34.07, 52.02, 54.80, 57.32, 82.03, 99.10, 106.96, 110.70, 121.86, 126.82, 131.33, 133.57, 137.06, 138.36, 142.08, 147.90, 150.50, 155.84, 158.30, 166.42; MS (MALDI/TOF) m/z: 552 (M+ + H).

Reconversion of intermediates(I and I′) to prodrug 1

To explore the reversibility of the reaction between prodrugs 1 and 2 and their corresponding intermediates I and I′-1, the intermediate mixture comprised mainly of I′-1 (1 mg, 2.46 μmol) was dissolved in 1 mL of DMSO-d6 in an NMR tube at room temperature. A catalytic amount of deuterated TFA was added to the solution and 1H NMR spectra were recorded (at 25 °C) at regular intervals until I′-1 disappeared completely.

Kinetics

PBS buffers (pH 3.0 and 7.4) having an ionic strength of 0.159 (adjusted with NaCl) were used for the kinetic studies. Low buffer concentrations were used to minimize possible buffer catalysis (H2PO4− concentrations were 9mM and 3mM at pH 3.0 and 7.4, respectively; HPO42- concentrations were 0.001 mM and 6mM at pH 3.0 and 7.4, respectively). pH values were measured with a Beckman Φ 40 pH meter with a Ross semimicro w/BNG glass electrode (Thermo Orion, Beverly, MA) and re-measured before each experiment. The pH meter was calibrated with standard aqueous buffer solutions from Fisher Scientific. All concentrated standard stock solutions (2 × 10−3 M) of 1, 2, I′-1, I′-2, and CPT-lactone were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide and stored in the dark at −20 °C. The stock solution of CPT-carboxylate (4 × 10−4 M) was generated in PBS buffer (∼pH 12).

Kinetic runs were initiated by injecting 10 μL of a stock solution in DMSO (or aqueous buffer at pH 12 in the case of CPT-carboxylate) to the appropriate buffer solution preequilibrated at 37 ± 0.2 °C. The final substrate concentration was 1 × 10 −6 M and the percentage of DMSO in the buffer solution was 0.25% (v/v). The reactions were monitored by following the disappearance of the starting material and the appearance of products.

Reactant and product concentrations were determined by reversed-phase HPLC (Waters 2690 separations module) equipped with a scanning fluorescence detector (Waters 474) and a 150 × 3.9 mm, 5 μm C18 column (Symmetry®, Waters). A flow rate of 1 mL/min was employed with linear mobile phase gradients. Acetonitrile was used as mobile phase A. Mobile phase B was a solution of 5% (v/v) triethylamine in water at pH 5.5 ± 0.5 (pH was adjusted with acetic acid). The total run time was 30 min. In the analysis of CPT related compounds a linear gradient over 22 min (14% A to 21% A for 1 and I′-1 −1; 17% A to 22% A for 2 and I′-2) was followed by 7 min. column equilibration at the original conditions (i.e., 14% A or 17% A). In the analysis of DB-67 related compounds a linear gradient over 20 min (26% A to 35% A for 5 and I′-5; 30% A to 40% A for 6 and I′-6) was followed by 10 min. column equilibration at the original conditions 26% A or 30% A. All compounds related to CPT were detected at an excitation wavelength of 370 nm and an emission wavelength of 440 nm while DB-67 related compounds w[ere detected at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 560 nm. Calibration curves constructed from plots of peak area versus concentration were linear over the range of concentration of substrate of 0.005−5 × 10−6 M for CPT-lactone, CPT-carboxylate and 2, 0.1−10 × 10−6 M for 1, and 0.01−10−6 M for I′-1 and I′-2. The coefficients of variation obtained for standard response factors were 2.4−4.3%. Given that reference standards for the I″ intermediates were not available, peak areas and a fitted response factor (assuming mass balance) were used to process the kinetic data. Concentration versus time profiles for each solution component at each pH were fit simultaneously by non-linear least squares regression analysis using Scientist®, Micromath Inc. (Salt Lake City, UT) to the set of differential equations (Eqs. 1-6) corresponding to Scheme 2 to obtain rate constants, k, for each reaction.

To distinguish between the E-ring opened glycine ester and glycineamide as potential chemical structures for the intermediates I″, the products formed from I″-1 and I″-2 at pH 3.0 were monitored. Prodrug 1 or 2 in buffer (PBS, pH 6.8 ± 0.1) at 1 × 10 −6 M was incubated at 37 °C until only I″, CPT-carboxylate and CPT-lactone were detected by HPLC. The pH of the mixtures was then adjusted to ∼3.0 at room temperature and the resulting solution was monitored versus time at 37 °C.

Cytotoxicity Assay

The human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-435S was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, Virginia and cultured in Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (MEM) (Gibco/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma), 1% MEM non-essential amino acids solution (Gibco/BRL) and 100 U/mL of penicillin G and 100 mg/L of streptomycin sulfate (Gibco/BRL). The MDA-MB-435S cells were plated onto 24 well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and were allowed to grow for 24h at 37 °C/5% CO2/100% humidity.

Cells were treated with CPT, CPT analogs, or prodrugs at varying concentrations (indicated in figure legends) for a total of 72 hours and fixed with 15% trichloroacetic acid. Cells were stained with 0.4% sulforhodamine B (SRB) dye in 1% acetic acid for 30 minutes. Excess dye was washed off the plates with 1% acetic acid. Plates were then allowed to fully dry. 1 mL of 10mM Tris(base) was used to release SRB dye bound to cellular protein under gentle shaking for 5 minutes. 200 uL of each sample were added to a 96 well plate, and absorbance was measured at 490 nm.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants CA63653 and CA87061. The authors thank Dr. Stephen Zimmer, University of Kentucky, for helpful discussions regarding the cytotoxicity data.

References

- 1.Hertzberg RP, Caranfa MJ, Hecht SM. On the mechanism of topoisomerase I inhibition by camptothecin: evidence for binding to an enzyme-DNA complex. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4629–4638. doi: 10.1021/bi00437a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsiang YH, Lihou MG, Liu LF. Arrest of replication forks by drug-stabilized topoisomerase I-DNA cleavable complexes as a mechanism of cell killing by camptothecin. Cancer Res. 1989;49:5077–5082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaxel C, Kohn KW, Wani MC, Wall ME, Pommier Y. Structure-activity study of the actions of camptothecin derivatives on mammalian topoisomerase I: evidence for a specific receptor site and a relation to antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1465–1469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fassberg J, Stella VJ. A kinetic and mechanistic study of the hydrolysis of camptothecin and some analogues. J. Pharm. Sci. 1992;81:676–684. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600810718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mi Z, Burke TG. Differential interactions of camptothecin lactone and carboxylate forms with human blood components. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10325–10336. doi: 10.1021/bi00200a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bom D, Curran DP, Kruszewski S, Zimmer SG, Thompson Strode J, Kohlhagen G, Du W, Chavan AJ, Fraley KA, Bingcang AL, Latus LJ, Pommier Y, Burke TG. The novel silatecan 7-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin displays high lipophilicity, improved human blood stability, and potent anticancer activity. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:3970–3980. doi: 10.1021/jm000144o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bom D;, Curran DP, Chavan AJ, Kruszewski S, Zimmer SG, Fraley KA, Burke TG. Novel A,B,E-Ring-Modified Camptothecins Displaying High Lipophilicity and Markedly Improved Human Blood Stabilities. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:3018–3022. doi: 10.1021/jm9902279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bom D, Curran DP, Zhang J, Zimmer SG, Bevins R, Kruszewski S, Howe JN, Bingcang A, Latus LJ, Burke TG. The highly lipophilic DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor DB-67 displays elevated lactone levels in human blood and potent anticancer activity. J. Control. Rel. 2001;74:325–333. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollack IF, Erff M, Bom D, Burke TG, Strode JT, Curran DP. Potent Topoisomerase I Inhibition by Novel Silatecans Eliminates Glioma Proliferation in Vitro and in Vivo. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4898–4905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Lynn BC, Zhang J, Song L, Bom D, Du W, Curran DP, Burke TG. A versatile prodrug approach for liposomal core-loading of water-insoluble camptothecin anticancer drugs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7650–7651. doi: 10.1021/ja0256212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colbern GT, Dykes DJ, Engbers C, Musterer R, Hiller A, Pegg E, Saville R, Weng S, Luzzio M, Uster P, Amantea M, Working PK. Encapsulation of the topoisomerase I inhibitor GL147211C in pegylated (STEALTH) liposomes: pharmacokinetics and antitumor activity in HT29 colon tumor xenografts. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998;4:3077–3082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emerson DL, Bendele R, Brown E, Chiang S, Desjardins JP, Dihel LC, Gill SC, Hamilton M, LeRay JD, Moon-McDermott L, Moynihan K, Richardson FC, Tomkinson B, Luzzio MJ, Baccanari D. Antitumor efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution of NX-211: A low-clearance liposomal formulation of lurtotecan. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:2903–2912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tardi P, Choice E, Masin D, Redelmeier T, Bally M, Madden TD. Liposomal encapsulation of topotecan enhances anticancer efficacy in murine and human xenograft models. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3389–3393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messerer CL, Ramsay EC, Waterhouse D, Ng R, Simms E-M, Harasym N, Tardi P, Mayer LD, Bally MB. Liposomal irinotecan: formulation development and therapeutic assessment in murine xenograft models of colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:6638–6649. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pal A, Khan S, Wang Y-F, Kamath N, Sarkar AK, Ahmad A, Sheikh S, Ali S, Carbonaro D, Zhang A, Ahmad I. Preclinical safety, pharmacokinetics and antitumor efficacy profile of liposome-entrapped SN-38 formulation. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:331–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zamboni WC, Jung LL, Strychor S, Joseph E, Fetterman SA, Burke TG, Curran DP, Egorin MJ, Eiseman JL. Disposition of non-liposomal DB-67 and bilayer liposomal DB-67 in non tumor bearing C.B.-17 SCID mice. unpublished results. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Liu X, Zhang J, Song L, Lynn BC, Burke TG. Degradation of camptothecin-20(S)-glycinate ester prodrug under physiological conditions. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2004;35:1113–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenwald RB, Pendri A, Conover CD, Lee C, Choe YH, Gilbert C, Martinez A, Xia J, Wu D, Hsue M-M. Camptothecin-20-PEG ester transport forms: the effect of spacer groups on antitumor activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1998;6:551–562. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H, Lee C, Sai P, Choe YH, Boro M, Pendri A, Guan S, Greenwald RB. 20-O-acylcamptothecin derivatives: evidence for lactone stabilization. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:4601–4606. doi: 10.1021/jo000221n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy GC, Lichter RL. Nitrogen-15N nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Wiley Interscience; New York, NY: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao Z, Harris N, Kozielski A, Vardeman D, Stehlin JS, Giovanella B. Alkyl esters of camptothecin and 9-nitrocamptothecin: synthesis, in vitro pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and antitumor activity. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:31–37. doi: 10.1021/jm9607562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Groot FM, Busscher GF, Aben RW, Scheeren HW. Novel 20-carbonate linked prodrugs of camptothecin and 9-aminocamptothecin designed for activation by tumour-associated plasmin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:2371–2376. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lerchen HG, Baumgarten J, von dem Bruch K, Lehmann TE, Sperzel M, Kempka G, Fiebig HH. Design and optimization of 20-O-linked camptothecin glycoconjugates as anticancer agents. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:4186–4195. doi: 10.1021/jm010893l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vishnuvajjala R, Garzon-Aburbey A. Preparation of water-soluble derivatives of camptothecin and their use as prodrugs in cancer therapy. 1990. U.S. Patent No. 4943579.

- 25.Yang LX, Pan X, Wang HJ. Novel camptothecin derivatives. part 1: oxyalkanoic acid esters of camptothecin and their in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:1241–1244. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warnecke A, Kratz F. Maleimide-oligo(ethylene glycol) derivatives of camptothecin as albumin-binding prodrugs: synthesis and antitumor efficacy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2003;14:377–387. doi: 10.1021/bc0256289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wadkins RM, Potter PM, Vladu B, Marty J, Mangold G, Weitman S, Manikumar G, Wani MC, Wall ME, Von Hoff DD. Water soluble 20(S)-glycinate esters of 10,11-methylenedioxycamptothecins are highly active against human breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3424–3428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taft RW. Steric Effects in Organic Chemistry. Wiley; New York: 1956. p Chpt. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson BD, Conradi RA, Knuth KE. Strategies in the design of solution stable, water soluble prodrugs. I. A physical organic approach to pro-moiety selection for 21-esters of corticosteroids. J. Pharm. Sci. 1985;74:365–374. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600740402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirby AJ, Komarov LV, Feeder N. Synthesis, structure and reactions of the most twisted amide. . J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. I. 2001;2:522–529. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cordes EH, Bull HG. Mechanism and catalysis for hydrolysis of acetals, ketals, and ortho esters. Chem. Rev. 1974;74:581–603. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McClelland RA. Rate-limiting deprotonation in tetrahedral intermediate breakdown. J. Am.Chem. Soc. 1984;106:7579–7583. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santry LJ, McClelland RA. Orientation effects on the rate and equilibrium constants for formation and decomposition of tetrahedral intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:6138–6141. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deslongchamps P. Stereoelectronic control in the cleavage of tetrahedral intermediates in the hydrolysis of esters and amides. Tetrahedron. 1975;31:2643–2690. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deslongchamps P. The importance of conformation of the tetrahedral intermediate in the hydrolysis of esters and amides. Pure Appl. Chem. 1975;43:351–378. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deslongchamps P. Stereoelectronic control in hydrolytic reactions. Heterocycles. 1977;7:1271–1317. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adamovics JA, Hutchinson CR. Prodrug analogues of the antitumor alkaloid camptothecin. J. Med. Chem. 1979;22:310–314. doi: 10.1021/jm00189a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]