Abstract

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK), a mediator of β integrin signals, has emerged as a therapeutic target in malignant tumors. Because malignant transformation is accompanied by dedifferentiation, ILK expression was evaluated in diverse normal and tumor tissue samples with regard to tissue differentiation. In single sections and in a tissue microarray (323 tumor tissues, 181 normal tissues), immunohistochemistry was performed [ILK, Akt, phospho-Akt-S473, loricrin, transforming growth factor β2 (TGFβ2)], and staining intensities were semiquantitatively scored. Increased ILK expression was clearly associated with increased differentiation in normal gastrointestinal, neural, bone marrow, renal tissue, and in more differentiated areas of malignant tumors. ILK colocalized with its putative downstream target Akt and with loricrin or TGFβ2. Our findings clearly show that elevated levels of ILK are associated with cellular differentiation in high turnover tissues but not generally with a malignant phenotype. Our study indicates that ILK is not a general molecular target for cancer therapy but rather an indicator of differentiation. This manuscript contains online supplemental material at http://www.jhc.org. Please visit this article online to view these materials. (J Histochem Cytochem 56:819–829, 2008)

Keywords: integrin-linked kinase, differentiation, tumor, normal tissue, tissue microarray

Current conventional anticancer strategies using radio- and chemotherapy are applied without discriminating between tumor and normal cells. Novel molecular therapeutics targeting, for example, cell surface receptors or intracellular signaling proteins have been designed, on the one hand, to specifically eradicate malignant cells when given as monotherapy and, on the other hand, to improve tumor control when given in combination with conventional radio- or chemotherapy (Ragnhammar et al. 2001; Tappenden et al. 2007; Wunder et al. 2007; Murdoch and Sager 2008). Most importantly, the rationale for a useful and safe application of such targeted therapeutics lies in a differential expression or activity of a target molecule between tumor and normal tissue.

Recently, integrin-linked kinase (ILK) has been reported as new potent target molecule in cancer (Hannigan et al. 2005). ILK is a serine/threonine protein kinase that interacts with the cytoplasmic domains of integrin β1, β2, and β3 subunits (Hannigan et al. 1996). Besides a variety of critical functions such as phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β to control the Wnt pathway (Delcommenne et al. 1998; D'Amico et al. 2000) or stimulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α expression to mediate induction of vascular endothelial growth factor–driven tumor angiogenesis (Tan et al. 2004), ILK was under debate as a putative, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)-dependent phosphorylator of Akt at S473 (Delcommenne et al. 1998; Persad et al. 2001). To date, it seems generally accepted that Akt is phosphorylated by the mammalian target of rapamycin at S473 (Sarbassov et al. 2004; Boudeau et al. 2006).

Concerning former histological analysis of ILK expression in cancer, ILK seems to be overexpressed in a number of human cancers (Persad and Dedhar 2003). Comparing normal colon and adenocarcinomas of the colon, ILK expression was elevated in the tumors (Marotta et al. 2001,2003), which was similar to a study on prostate cancers. Here, ILK positivity was greater in malignant than in normal tissue and was increasingly detectable in high-grade tumors (Graff et al. 2001). In primitive neuroectodermal tumors and in medulloblastomas, ILK has been reported to be present in both of these tumor types (Chung et al. 1998). However, two thirds of neuroblastomas analyzed and 100% of other primitive tumors such as retinoblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and lymphoblastic lymphoma lacked ILK expression. Moreover, all mesenchymal chondrosarcomas, osteosarcomas, and osteoblastomas analyzed in this study were also ILK negative (Chung et al. 1998).

In addition to this controversy, the role of ILK in cell survival on exposure to cytotoxic drugs or ionizing radiation also remains to be clarified. On exposure to X-rays, overexpression of wild-type ILK or an ILK mutant with a constitutively active kinase domain significantly reduced clonogenic cell survival of human lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, and leukemia cells (Cordes 2004; Eke et al. 2006,2007; Hehlgans et al. 2007a; Hess et al. 2007). In contrast, analysis of cell viability and apoptosis showed that cells overexpressing ILK survived better on treatment with cytotoxic drugs and that pharmacological ILK inhibitors or ILK small interfering RNA transfection pronouncedly reduced cell viability under treatment (Duxbury et al. 2005; Younes et al. 2005,2007).

Taking these discrepancies in histological examinations and cell survival into account, this study was performed to elucidate whether ILK upregulation correlates with dedifferentiation/loss of differentiation representing a critical characteristic of malignant tumors. Besides ILK, expression of the differentiation markers loricrin and transforming growth factor β2 (TGFβ2) (Mehrel et al. 1990; Nawshad et al. 2004) and the ILK putative downstream target Akt were examined in a large number of human and mouse normal and tumor tissues of diverse origin. From our point of view, this study was needed to support the clarification of ILK's role in cellular differentiation and its potency as a therapeutic cancer target.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Specimens and Tissue Microarray

Human tissues were obtained from pathology archival material in a blinded fashion as approved by the ethics committee of the Dresden University of Technology (Dresden, Germany). The human squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cell lines UT-SCC14 and UT-SCC15 were grown in NMRI nude mice. Animal experiments were approved by the animal committee of the Dresden University of Technology and by the State of Saxony. For the production of tissue microarrays (TMAs), an AlphaMetrix device (AlphaMetrix; Rödermark, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The TMA consisted of 504 tissue samples (323 tumor + 181 normal; ST1) placed on four different tissue blocks.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed in 10 mM citric acid, pH 6.0, at 98C for 15 min. The following antibodies were used for immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence staining: rabbit polyclonal anti-ILK (KAP-ST203, dilution 1:100; Stressgen, Hamburg, Germany) (Marotta et al. 2003), mouse monoclonal anti-ILK (sc-20019, dilution 1:100) (Mills et al. 2006; Sawai et al. 2006), rabbit polyclonal anti-TGF-β2 (dilution 1:100; Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany), rabbit polyclonal anti-Akt (dilution 1:10), mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-Akt-S473 (dilution 1:30; Cell Signaling, Frankfurt, Germany), and rabbit polyclonal anti-loricrin (dilution 1:80; Covance-Hiss, Freiburg, Germany). Biotin-labeled secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories; Grünberg, Germany) were diluted 1:200. Signal amplification and color development were done with the streptavidin-biotin–based VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit (Axxora; Grünberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions using a horseradish peroxidase–catalyzed reaction and DAB as the substrate. For immunofluorescence detection, the TSA-kit (Invitrogen; Karlsruhe, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. This kit is based on tyramide-based signal amplification and includes the fluorochromes Alexa Fluor 488 and 546. Nuclei were counterstained with 4,5-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Negative controls for both immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence stainings were performed by replacing primary antibodies with non-immune serum of the appropriate species. Negative control reactions yielded no staining confirming the specificity of the antibody recognition.

Intensity Evaluation, Scoring, and Statistical Analysis

Stainings were evaluated by a pathologist (MH). The following semiquantitative score was used: 0, no staining; 1, weak staining (just above background); 2, medium intensity staining; 3, strong staining. Differences of the ILK staining intensities between tissue blocks were adjusted with the means of at least three different standard tissue cores placed in each block. Statistical analysis of the staining intensities between different tissue groups was done using the χ2 test.

Western Blotting

Normal human fibroblasts (HSF-2, kindly provided by H.P. Rodemann, University of Tuebingen, Germany) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum. Proteins were extracted as described (Hess et al. 2007). Western blots were done using standard procedures (Sambrook et al. 1989) and were performed as three independent experiments.

Results

Localization of ILK in Normal and Tumor Tissues of the Gastrointestinal Tract

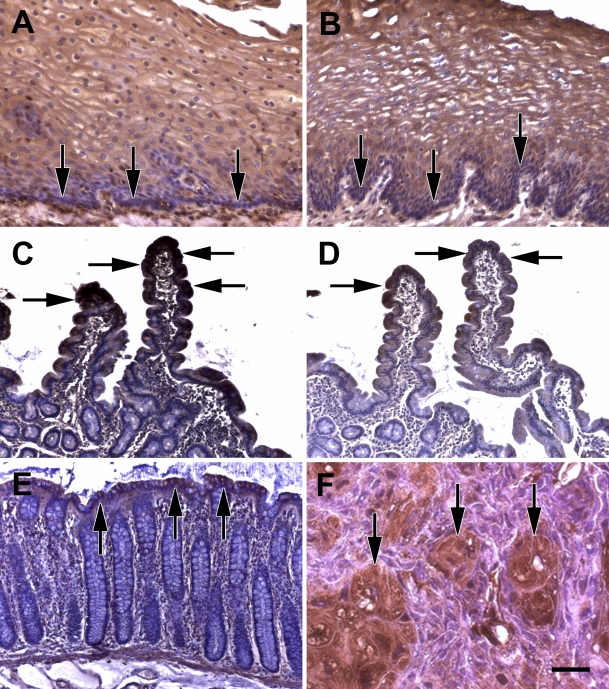

At first, because of its high hierarchic differentiation order, different epithelia of the gastrointestinal tract were examined for ILK expression. In the epithelium of the esophagus, the basal layer (Figures 1A and 1B, arrows) contained less ILK than the layers above. The layers directly above the basal layer showed a diffuse cytoplasmic staining, whereas in the middle layers of the epithelium, ILK was accentuated at the cell membrane. In the small intestine, crypt cells contained much less ILK than the cells of the upper parts of the villi (Figures 1C and 1D, arrow). Similar findings were obtained in the colon (Figure 1E). In particular, the surface epithelium showed an ILK positivity (arrows) comparable to the intensity of the lamina muscularis mucosae (Figure 1E). In a human SCC xenograft model in nude mice, which delineated areas of spontaneous differentiation, ILK expression was intense in these differentiated areas (Figure 1F, arrows) in contrast to surrounding more immature tumor cells.

Figure 1.

Higher integrin-linked kinase (ILK) expression in differentiated areas of normal and tumor tissue. (A,B) Normal human esophagus epithelium (arrows point to basal layer that contains less ILK). (C,D) Normal human small intestine (arrows point to upper part of villi). (E) Normal human colon mucosa (arrows point to surface epithelium). (F) Human UT-SCC14 squamous cell carcinoma xenograft in mouse (arrows point to more differentiated areas of the tumor). Stainings were performed using two different reported anti-ILK antibodies: (A,C,E,F) monoclonal anti-ILK antibody from Santa Cruz and (B,D) rabbit polyclonal anti-ILK antibody from Stressgen. Bar: A,B = 58 μm; C–E = 116 μm; F = 29 μm.

Localization of ILK in Tissues and Tumors Derived From Different Germ Layers

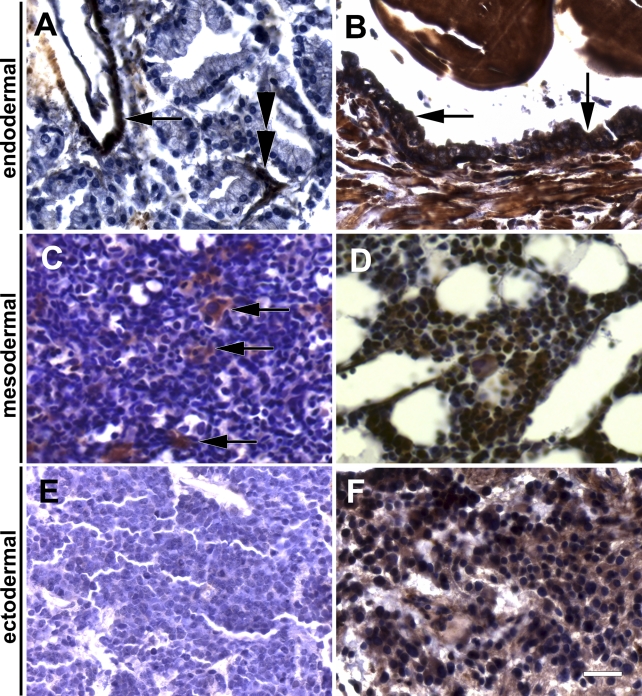

We next sought to study tissues from all three germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm, neuroectoderm) to present further supportive evidence for the observed association of ILK and differentiation. At first, in addition to the endoderm-derived intestinal tissues described above, the endoderm-derived epithelium of the prostate was examined. In general, the epithelial cells of prostate adenocarcinomas contained less ILK [including cases with no ILK expression: Figure 2A) compared with the three ILK-positive tissues, i.e., blood vessels (Figure 2A, arrow), surrounding connective tissue (Figure 2A, double arrowhead) and normal prostate epithelium (Figure 2B, arrows). Second, the mesoderm-derived hematopoietic system (i.e., bone marrow) was evaluated for ILK expression. Tumor tissue of immature hematopoietic cells showed weak ILK staining in cells from human acute myeloblastic leukemia (Figure 2C), whereas mature megakaryocytes in this tissue contained high amounts of ILK (Figure 2C, white arrow). Mature bone marrow was highly positive for ILK including neutrophil granulocytes and megakaryocytes (Figure 2D). Third, the ectoderm-derived neural tissue was explored showing immature neuroectodermal cells from a human neuroblastoma to be marginally positive for ILK (Figure 2E). In contrast, cells from more mature ganglioneuroblastomas contain pronouncedly more ILK (Figure 2F), which was similar in mature ganglions (data not shown). With regard to the intracellular localization of ILK, most cell types showed a cytoplasmic ILK staining. A distinct cell membrane staining of ILK could only be found in squamous epithelial cells of normal tissue (see Figure 1A) and more differentiated cells within a subgroup of SCCs (see Figure 1F) as well as for most clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinomas (see below).

Figure 2.

ILK expression analysis in normal tissues and tumors derived from different germ layers (endodermal, mesodermal, neuroectodermal) using immunohistochemistry. Endodermal: (A) human prostate cancer (arrow points to strongly stained vessel; double arrowhead points to connective tissue between tumor glands, possibly containing capillary endothelial cells) and (B) normal human prostate tissue (arrows point to normal prostate epithelium). Mesodermal: (C) immature hematopoietic cells of an acute myeloblastic leukemia (white arrow points to normal megakaryocytes between the leukemia cells) and (D) normal human bone marrow. Neuroectodermal: (E) human neuroblastoma and (F) human ganglioneuroblastoma. Bar = 29 μm.

ILK Is Coexpressed With Differentiation Markers

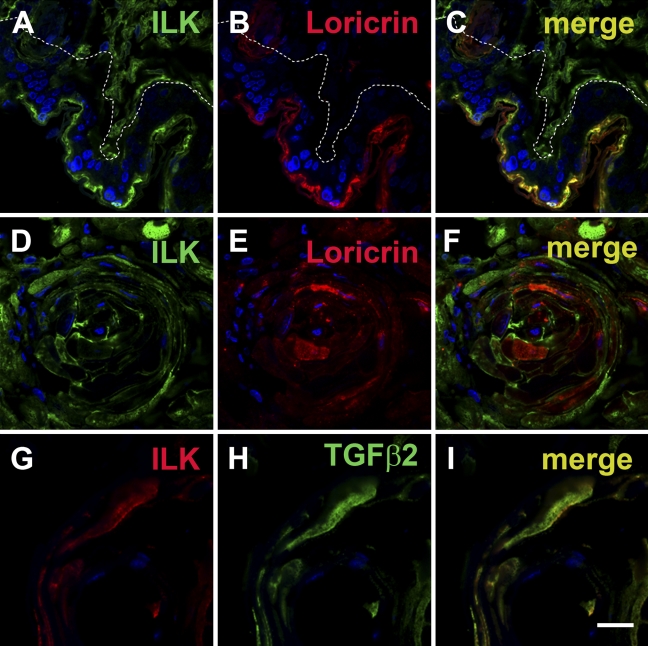

To further assess the association of ILK with differentiation, different tissue samples were double stained with ILK and the differentiation markers loricrin or TGFβ2. In the mouse skin, both ILK (Figure 3A) and loricrin (Figure 3B) were coexpressed and colocalized in the upper layers of the skin. In differentiated areas of the SCC xenografts, ILK (Figure 3D) and loricrin (Figure 3E) were also coexpressed but not colocalized within the cells. Here, loricrin was mainly cytoplasmic and ILK was membranous. Co-staining of ILK with TGFβ2 indicated a similar observation in the more differentiated tumor areas of SCC xenografts (Figures 3G–3I).

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence double labeling of ILK and the differentiation markers loricrin or transforming growth factor β2 (TGFβ2) in squamous epithelium and squamous cell carcinomas. (A-C) Mouse skin. ILK is colocalized with loricrin. White dotted line marks the basal membrane. Tissue in the right top corner is connective tissue, which is positive for ILK but not for loricrin. (D-F) Human UT-SCC15 squamous cell carcinoma xenograft in nude mice. ILK shows a higher expression in the more differentiated areas of the tumor co-stained for loricrin. (G-I) Human UT-SCC15 squamous cell carcinoma xenograft in nude mice. ILK is coexpressed in a cell positive for TGFβ2, indicating differentiation. Bar: A–F = 20 μm; G–I = 10 μm.

ILK Is Colocalized With Phosphorylated Akt-S473

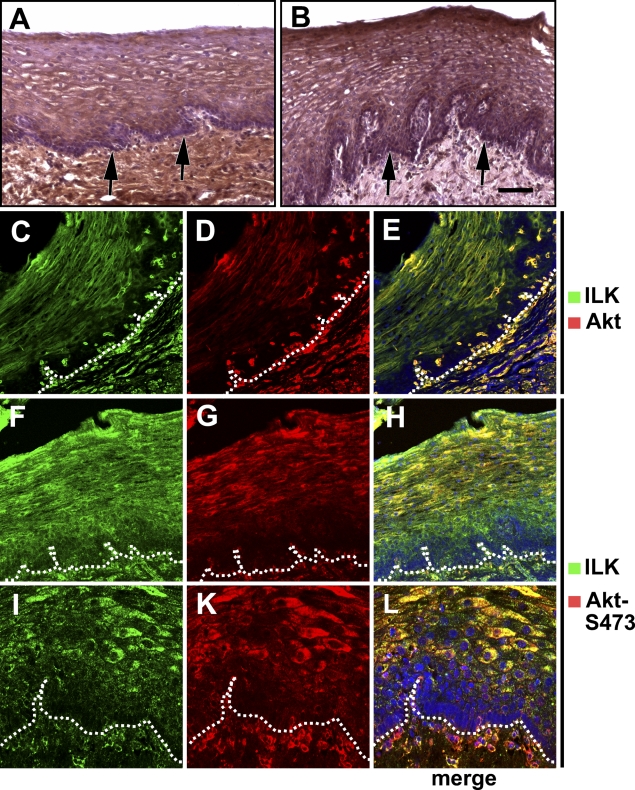

Because ILK is believed to phosphorylate Akt at S473, we next examined the colocalization of ILK with Akt or its S473-phosphorylated form in normal epithelium of the esophagus, representing the strongest differentiation hierarchy. Whereas the basal layer of the epithelium per se showed a low Akt expression (Figure 4A, arrow), Akt expression was higher in more differentiated squamous epithelial cells (Figure 4A). Stromal cells generally showed a high Akt expression (Figure 4A). Both, the staining intensity and localization of phosphorylated Akt-S473 correlated with total Akt (Figure 4B, arrow). These findings were confirmed by immunofluorescence double labeling of ILK plus Akt or phosphorylated Akt-S473 (Figures 4C–4L).

Figure 4.

Colocalization of ILK with Akt or phosphorylated Akt-S473 in normal epithelium of the esophagus. (A) Higher expression of Akt in more differentiated epithelial cells (arrows: basal layer). (B) Phosphorylated Akt-S473 has the same distribution pattern as ILK in squamous epithelium (arrows, basal layer). (C–E) Colocalization of ILK with Akt in epithelium and stroma (dotted line in C–H is drawn under the basal layer of the epithelium). (F–H) ILK is colocalized with phosphorylated Akt-S473. (I–L) Higher magnification of lower layers of squamous epithelium stained for ILK and phosphorylated Akt-S473. Bar: A = 72 μm; B = 93 μm; C–H = 83 μm; I–L = 41 μm.

Comparison of ILK Expression Between Normal and Tumor Tissues and Between Different Tumor Tissues

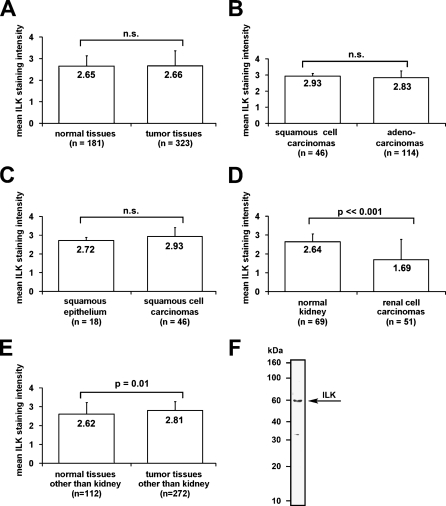

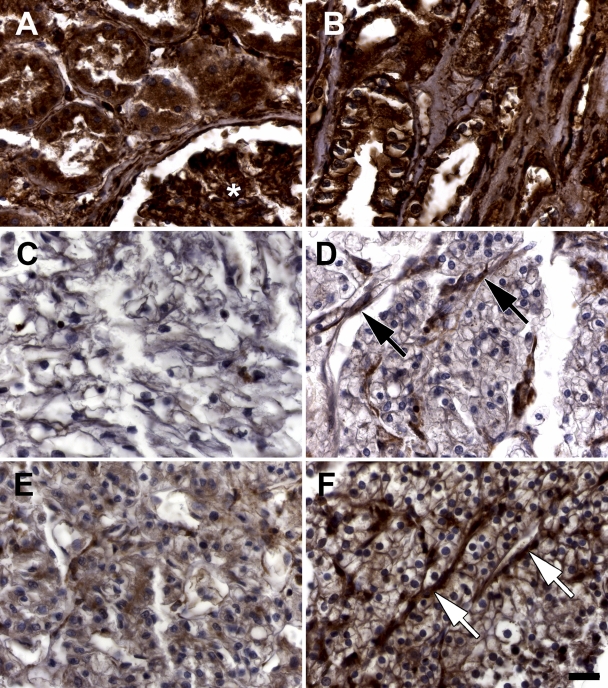

In the following, an immunohistochemistry analysis on ILK was performed using a self-designed TMA (323 tumor, 181 normal; see supplementary information). Overall, we found no significant difference in ILK expression between all normal and tumor tissues implemented in the TMA (see supplementary information; Figure 5A). Adenocarcinomas had a slightly lower ILK expression compared with squamous cell carcinomas, which was not statistically significant (Figure 5B). The mean ILK expression of squamous cell carcinomas is ∼10% higher than in normal squamous epithelium, but this difference is not statistically significant (Figure 5C). In contrast, the mean ILK expression in renal cell carcinomas is reduced by ∼35% compared with normal kidney tissue, which is statistically highly significant (Figure 5D; p<0.001). In consideration of a large number of renal tissues in the TMA, the corrected statistical analysis of ILK expression in normal tissues other than kidney vs tumor tissues other than kidney showed to be significantly increased in the tumor tissues (Figure 5E). In contrast to the majority of renal cell carcinomas showing this strongly reduced ILK expression, a small number indicated a moderate and distinct cell membrane localized ILK staining (Figures 6A–6F). Western blot analysis of human normal fibroblast protein lysates showed the polyclonal anti-ILK antibody (Stressgen) to recognize a major band at ∼60 kDa, which corresponds to ILK. The specificity of the anti-ILK mouse monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz) has been shown in the datasheet of the company.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the tissue microarray (TMA) data of different normal and tumor tissues using semiquantitative scoring and the χ2 test. (A) Comparison of the mean ILK staining intensities of normal (n=181) vs tumor tissues (n=323) without significant difference. (B) Comparison of the mean ILK staining intensities between the major groups of epithelial cancers: squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas. (C) Comparison between benign squamous epithelium and squamous cell carcinomas shows no significant increase in squamous cell carcinomas. (D) Comparison between normal renal tissue and renal cell carcinomas shows a highly significant decrease of ILK staining in renal cell carcinomas. (E) Comparison between normal tissues other than kidney vs tumor tissues other than kidney indicates a significant increase of ILK staining in tumor tissues. (F) The polyclonal anti-ILK antibody (Stessgen) recognizes an ∼60-kDa band in a Western blot from a protein extract of normal human fibroblasts (HSF-2).

Figure 6.

ILK staining in normal and malignant renal TMA samples. A TMA containing 69 normal renal tissue samples and 51 samples of renal cell carcinomas was stained with an anti-ILK antibody (Santa Cruz) and analyzed by a four-tiered semiquantitative staining score. (A) Normal renal tissue containing proximal tubules and a glomerulus (asterisk) is strongly stained (intensity 3). (B) Normal renal tissue from distal tubules and Henle's loop are also strongly stained (intensity 3). (C,D) Renal cell carcinoma samples with no ILK staining (intensity 0, note strongly stained capillaries: arrows in D). (E) Weak staining of a renal cell carcinoma (intensity 1). (F) Moderate staining of a renal cell carcinoma (intensity 2). Arrows point to vessels with strong staining. Bar = 29 μm.

Discussion

ILK is currently under intense investigation with regard to its role as a therapeutic target in anticancer treatment. The findings on ILK's prosurvival effects and on the differential expression of ILK in tumor vs normal tissue are controversial. Because of these facts and the clinical relevance of a differential ILK expression in tumor vs normal tissues, this study was carried out using single tissue sections and a TMA. ILK expression was evaluated in different tumor and normal tissues with special focus on the relationship between ILK and differentiation. Cellular differentiation can be concluded from the localization of a cell in a tissue (i.e., tissue architecture) and the expression of specific differentiation marker proteins such as loricrin and TGFβ2. The hierarchical structures present in the different tissues examined were used for the histological examinations.

The findings of this study clearly indicate that ILK is strongly associated with cellular differentiation and coexpressed/colocalized with loricrin and TGFβ2 in the specific tissues investigated. This was shown with different anti-ILK antibodies. In our study, ILK expression was significantly overexpressed in tumors of diverse origin (difference in statistical analysis between Figures 5A and 5E because of exclusion of kidney tissue), but the biological importance underlying this overexpression is questionable because of its minor extent, which is highly unlikely to affect the therapeutic ratio. In our study, we found no tumor type with exceptionally high expression of ILK, which means that there is no tumor type that would be a candidate for specific targeting of ILK as a therapeutic option. In some cases (e.g., renal cell carcinoma), ILK mean staining intensity is pronouncedly decreased compared with normal tissue and with SCCs or adenocarcinomas. Whether the tumor grade is correlative to ILK positivity should be evaluated in further studies. An important finding, which confirms published data, is the association of ILK with its putative downstream target Akt and the level of Akt-S473 phosphorylation.

A role of ILK in differentiation is known from different studies in hepatocytes, kidney, and brain (Belvindrah et al. 2006; Gkretsi et al. 2007; Li et al. 2007). Our findings corroborate these data and add further supporting information by delineating a coexpression of ILK with both loricrin and TGFβ2. This can particularly be seen in multilayered epithelium of the skin, mouth, and esophagus. In these tissues, the basal cells are more immature and contain stem cells of the squamous epithelium. ILK usually shows a low expression level in these cells. In the epithelium of the esophagus, ILK expression increases immediately above this basal layer. In the small and large intestine, the whole crypts contain low amounts of ILK, whereas the villi of the small intestine or the surface epithelium are strongly positive for ILK. Similar to the gastrointestinal tract, the mature functional cells of the bone marrow present the highest ILK expression.

Using a TMA containing most normal tissues and all major types of malignant tumors, no significant difference between ILK expression in normal and tumor tissues was observed. Our findings partly corroborate the report by Chung et al. (1998) showing low or absent ILK expression in many highly proliferative tumors such as lymphoblastic lymphoma and retinoblastoma and other types of undifferentiated tumor cells. Moreover, linking ILK to more differentiated areas of tumors or to tumors with moderate or slow doubling times, ILK seems to be associated with decreased proliferation. Consequently, ILK expression in tumors may generally reflect partial differentiation of tumor tissue, which is typically associated with decreased proliferation. According to our data, ILK could be a marker of differentiating tumor cells that cease to exist as therapeutic targets. According to this opinion, tumors with areas of high ILK staining would simply contain larger areas of differentiation, whereas the clonogenic, proliferating cells are not stained. In contrast, a study in colon cancer showed that ILK expression was higher in dysplastic lesions than in normal tissue (Marotta et al. 2001). However, in this study, expression in tumors was compared with basal and middle parts of the colon mucosa where ILK expression is low. Obviously, the upper part of the mucosa with its pronounced ILK staining was not evaluated in the study by Marotta et al. (2001). Another study in prostate cancer found that, compared with tissues with benign prostatic hyperplasia, a higher percentage of tumors express ILK and that ILK expression in prostate carcinomas correlates with tumor grade (Graff et al. 2001).

ILK binds to the cytoplasmic tail of β1 integrins, which suggests that the cellular distribution of both proteins should be similar (Hehlgans et al. 2007b). However, β1 integrin expression has been described in the basal layer of the epidermis and to be lower in differentiating cells (Jones and Watt 1993; Brakebusch et al. 2000), which is an inverse pattern compared with ILK. These data suggest that β1 integrin signaling in basal cells of the squamous epithelium cannot be mediated by ILK and that integrin signaling in these cells is mediated by other molecules such as FAK (Wennerberg et al. 2000). We conclude that the interaction between β1 integrin and ILK seems to be dependent on the differentiation status of the cells.

In agreement with published data, ILK and Akt are coexpressed in the examined tissues, resulting in an association of ILK with phosphorylated Akt-S473. Because this coexpression also correlates with the grade of differentiation, our data are consistent with the theory of a relationship between grade of cellular differentiation and radioresistance or chemoresistance (Pirollo et al. 1993; Wang et al. 1999). The predominant underlying mechanism of this resistance phenotype is currently being studied.

In conclusion, this study clearly showed a hierarchical expression of ILK in many tissues and that ILK expression is associated with cellular differentiation. Our findings generated in a large set of tumor and normal tissues may have potential clinical applicability with regard to the use of novel therapeutic targeting strategies against ILK. Unless pathologically evaluated on an individual basis, ILK seems not to represent a reasonable target molecule in most types of tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors and research were supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Science (BMBF-03ZIK041). Tumor samples from UT-SCC 14 and 15 mouse xenografts were kindly provided by Dr. M. Baumann (Dresden University of Technology, Dresden, Germany).

The authors thank Daniela Tschuck for excellent technical assistance and Wolf Dietrich Meyer (Dresden University of Technology, Dresden, Germany) for help with statistical analysis.

References

- Belvindrah R, Nalbant P, Ding S, Wu C, Bokoch GM, Muller U (2006) Integrin-linked kinase regulates Bergmann glial differentiation during cerebellar development. Mol Cell Neurosci 33:109–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudeau J, Miranda-Saavedra D, Barton GJ, Alessi DR (2006) Emerging roles of pseudokinases. Trends Cell Biol 16:443–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakebusch C, Grose R, Quondamatteo F, Ramirez A, Jorcano JL, Pirro A, Svensson M, et al. (2000) Skin and hair follicle integrity is crucially dependent on beta 1 integrin expression on keratinocytes. EMBO J 19:3990–4003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung DH, Lee JI, Kook MC, Kim JR, Kim SH, Choi EY, Park SH, et al. (1998) ILK (beta1-integrin-linked protein kinase): a novel immunohistochemical marker for Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumour. Virchows Arch 433:113–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes N (2004) Overexpression of hyperactive integrin-linked kinase leads to increased cellular radiosensitivity. Cancer Res 64:5683–5692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico M, Hulit J, Amanatullah DF, Zafonte BT, Albanese C, Bouzahzah B, Fu M, et al. (2000) The integrin-linked kinase regulates the cyclin D1 gene through glycogen synthase kinase 3beta and cAMP-responsive element-binding protein-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem 275:32649–32657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcommenne M, Tan C, Gray V, Rue L, Woodgett J, Dedhar S (1998) Phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinase B/AKT by the integrin-linked kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:11211–11216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury MS, Ito H, Benoit E, Waseem T, Ashley SW, Whang EE (2005) RNA interference demonstrates a novel role for integrin-linked kinase as a determinant of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell gemcitabine chemoresistance. Clin Cancer Res 11:3433–3438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke I, Sandfort V, Mischkus A, Baumann M, Cordes N (2006) Antiproliferative effects of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibition and radiation-induced genotoxic injury are attenuated by adhesion to fibronectin. Radiother Oncol 80:178–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke I, Sandfort V, Storch K, Baumann M, Roper B, Cordes N (2007) Pharmacological inhibition of EGFR tyrosine kinase affects ILK-mediated cellular radiosensitization in vitro. Int J Radiat Biol 83:793–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkretsi V, Mars WM, Bowen WC, Barua L, Yang Y, Guo L, St-Arnaud R, et al. (2007) Loss of integrin linked kinase from mouse hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo results in apoptosis and hepatitis. Hepatology 45:1025–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff JR, Deddens JA, Konicek BW, Colligan BM, Hurst BM, Carter HW, Carter JH (2001) Integrin-linked kinase expression increases with prostate tumor grade. Clin Cancer Res 7:1987–1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan G, Troussard AA, Dedhar S (2005) Integrin-linked kinase: a cancer therapeutic target unique among its ILK. Nat Rev Cancer 5:51–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan GE, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Fitz-Gibbon L, Coppolino MG, Radeva G, Filmus J, Bell JC, et al. (1996) Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new beta 1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature 379:91–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehlgans S, Eke I, Cordes N (2007a) An essential role of integrin-linked kinase in the cellular radiosensitivity of normal fibroblasts during the process of cell adhesion and spreading. Int J Radiat Biol 83:769–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehlgans S, Haase M, Cordes N (2007b) Signalling via integrins: implications for cell survival and anticancer strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1775:163–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess F, Estrugo D, Fischer A, Belka C, Cordes N (2007) Integrin-linked kinase interacts with caspase-9 and -8 in an adhesion-dependent manner for promoting radiation-induced apoptosis in human leukemia cells. Oncogene 26:1372–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PH, Watt FM (1993) Separation of human epidermal stem cells from transit amplifying cells on the basis of differences in integrin function and expression. Cell 73:713–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yang J, Luo JH, Dedhar S, Liu Y (2007) Tubular epithelial cell dedifferentiation is driven by the helix-loop-helix transcriptional inhibitor Id1. J Am Soc Nephrol 18:449–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta A, Parhar K, Owen D, Dedhar S, Salh B (2003) Characterisation of integrin-linked kinase signalling in sporadic human colon cancer. Br J Cancer 88:1755–1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta A, Tan C, Gray V, Malik S, Gallinger S, Sanghera J, Dupuis B, et al. (2001) Dysregulation of integrin-linked kinase (ILK) signaling in colonic polyposis. Oncogene 20:6250–6257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrel T, Hohl D, Rothnagel JA, Longley MA, Bundman D, Cheng C, Lichti U, et al. (1990) Identification of a major keratinocyte cell envelope protein, loricrin. Cell 61:1103–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills J, Niewmierzycka A, Oloumi A, Rico B, St-Arnaud R, Mackenzie IR, Mawji NM, et al. (2006) Critical role of integrin-linked kinase in granule cell precursor proliferation and cerebellar development. J Neurosci 26:830–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch D, Sager J (2008) Will targeted therapy hold its promise? An evidence-based review. Curr Opin Oncol 20:104–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawshad A, LaGamba D, Hay ED (2004) Transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta) signalling in palatal growth, apoptosis and epithelial mesenchymal transformation (EMT). Arch Oral Biol 49:675–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persad S, Attwell S, Gray V, Mawji N, Deng JT, Leung D, Yan J, et al. (2001) Regulation of protein kinase B/Akt-serine 473 phosphorylation by integrin-linked kinase: critical roles for kinase activity and amino acids arginine 211 and serine 343. J Biol Chem 276:27462–27469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persad S, Dedhar S (2003) The role of integrin-linked kinase (ILK) in cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev 22:375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirollo KF, Tong YA, Villegas Z, Chen Y, Chang EH (1993) Oncogene- transformed NIH 3T3 cells display radiation resistance levels indicative of a signal transduction pathway leading to the radiation-resistant phenotype. Radiat Res 135:234–243 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragnhammar P, Hafstrom L, Nygren P, Glimelius B (2001) A systematic overview of chemotherapy effects in colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol 40:282–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

- Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, et al. (2004) Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol 14:1296–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai H, Okada Y, Funahashi H, Matsuo Y, Takahashi H, Takeyama H, Manabe T (2006) Integrin-linked kinase activity is associated with interleukin-1 alpha-induced progressive behavior of pancreatic cancer and poor patient survival. Oncogene 25:3237–3246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C, Cruet-Hennequart S, Troussard A, Fazli L, Costello P, Sutton K, Wheeler J, et al. (2004) Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by integrin-linked kinase (ILK). Cancer Cell 5:79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappenden P, Jones R, Paisley S, Carroll C (2007) Systematic review and economic evaluation of bevacizumab and cetuximab for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Health Technol Assess 11:1–128, iii–iv [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Blandino G, Givol D (1999) Induced p21waf expression in H1299 cell line promotes cell senescence and protects against cytotoxic effect of radiation and doxorubicin. Oncogene 18:2643–2649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerberg K, Armulik A, Sakai T, Karlsson M, Fassler R, Schaefer EM, Mosher DF, et al. (2000) The cytoplasmic tyrosines of integrin subunit beta1 are involved in focal adhesion kinase activation. Mol Cell Biol 20:5758–5765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder JS, Nielsen TO, Maki RG, O'Sullivan B, Alman BA (2007) Opportunities for improving the therapeutic ratio for patients with sarcoma. Lancet Oncol 8:513–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younes MN, Kim S, Yigitbasi OG, Mandal M, Jasser SA, Dakak Yazici Y, Schiff BA, et al. (2005) Integrin-linked kinase is a potential therapeutic target for anaplastic thyroid cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 4:1146–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younes MN, Yigitbasi OG, Yazici YD, Jasser SA, Bucana CD, El-Naggar AK, Mills GB, et al. (2007) Effects of the integrin-linked kinase inhibitor QLT0267 on squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133:15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.