Abstract

In the cytoskeleton, unfavorable nucleation steps allow cells to regulate where, when, and how many polymers assemble. Nucleated polymerization is traditionally explained by a model in which multistranded polymers assemble cooperatively, whereas linear, single-stranded polymers do not. Recent data on the assembly of FtsZ, the bacterial homolog of tubulin, do not fit either category. FtsZ can polymerize into single-stranded protofilaments that are stable in the absence of lateral interactions, but that assemble cooperatively. We developed a model for cooperative polymerization that does not require polymers to be multistranded. Instead, a conformational change allows subunits in oligomers to associate with high affinity, whereas a lower-affinity conformation is favored in monomers. We derive equations for calculating polymer concentrations, subunit conformations, and the apparent affinity of subunits for polymer ends. Certain combinations of equilibrium constants produce the sharp critical concentrations characteristic of cooperative polymerization. In these cases, the low-affinity conformation predominates in monomers, whereas virtually all polymers are composed of high-affinity subunits. Our model predicts that the three routes to forming HH dimers all involve unstable intermediates, limiting nucleation. The mathematical framework developed here can represent allosteric assembly systems with a variety of biochemical interpretations, some of which can show cooperativity, and others of which cannot.

INTRODUCTION

Cytoskeletal polymers contribute to cell shape, movement, and force production. In eukaryotes, regulated polymer nucleation dictates where new polymers form in the cell. Both actin and microtubules assemble cooperatively, meaning that the nucleation of new polymers is energetically unfavorable relative to the elongation of preexisting polymers. Nucleation factors help overcome the energetic barrier to de novo polymer formation. Thus, by regulating where nucleation factors are active, cells can restrict polymer formation to appropriate locations.

In recent years, prokaryotes were found to possess cytoskeletal structures composed of actin and tubulin homologs (1–3). FtsZ is the bacterial homolog of tubulin, and uses guanine nucleotides to assemble into polymers resembling microtubule protofilaments. Like tubulin, FtsZ appears to assemble cooperatively (4–10). However, the traditional biochemical model used to explain the cooperative assembly of actin and tubulin cannot be applied to FtsZ, suggesting that a new model for cooperativity is needed.

Traditional polymerization models require nucleated, cooperative polymers to be multistranded, whereas single-stranded, linear polymers were thought in all cases to assemble noncooperatively (11,12). (The term “helical” has also been used to describe multistranded polymerization, whereas linear assembly is also called isodesmic polymerization.) In cooperative polymerization, assembly occurs in two stages: an unfavorable nucleation phase, followed by a more favorable elongation phase. In multistranded polymers, the affinity of a subunit for the end of a polymer is higher than the affinity of two monomers for each other, because when a subunit adds to a polymer, it can interact with several other subunits simultaneously (Fig. 1 B). In contrast, isodesmic polymerization means that the affinity of a subunit for a polymer end is independent of the length of the polymer. Single-stranded polymers were thought to assemble isodesmically, because identical interfaces form between subunits, whether they are assembling into dimers or elongating polymers (Fig. 1 A).

FIGURE 1.

Traditional polymerization models. (A) Isodesmic assembly of single-stranded polymers. A single association constant, KA, describes both dimerization and polymer elongation. (B) Cooperative assembly of multistranded polymers. Cooperativity occurs because nucleation (here, dimer formation) is less favorable than polymer elongation (Kn ≪ Ke). (C) Cooperative assembly has a sharp critical concentration, whereas isodesmic assembly does not. Black lines, cooperative assembly; gray lines, isodesmic assembly. (Solid line) protein in polymer at equilibrium; (dotted line) monomer concentration at equilibrium; (dashed line) maximum possible monomer concentration at equilibrium. Note that in both types of assembly, the monomer concentration approaches a maximum value, but for isodesmic assembly, approaching this limit requires a higher total protein concentration.

In cooperative polymerization, the nucleus can be defined as the smallest species for which elongation is more favorable than disassembly (13). Nucleation is difficult because one or more unstable species must form before the nucleus can form. These unstable species are exceedingly rare, and act as bottlenecks against the formation of new polymers. In multistranded polymerization, these rare species consist of all oligomers smaller than the nucleus. For isodesmic polymers, on the other hand, no bottleneck occurs during assembly. Dimer formation is energetically identical to polymer elongation, and small oligomers are not rare.

Cooperative polymers exhibit several other characteristics that can be readily detected. First, nucleated polymers have a critical concentration for assembly. The critical concentration is a threshold subunit concentration, below which subunits will not assemble into polymers, and above which virtually all additional protein will polymerize (Fig. 1 C, black lines). In contrast, in isodesmic systems, some polymers will assemble even when the monomer concentration is not at its maximum. As total protein concentration is increased, the equilibrium polymer and monomer concentrations can rise simultaneously (Fig. 1 C, gray lines).

Another characteristic of nucleated polymerization is the presence of concentration-dependent lags during initial polymerization kinetics. During the lag-phase, nuclei accumulate. The lag phase is followed by a growth phase, in which the formation of new nuclei is rare, but preexisting polymers continue to elongate. Isodesmic assembly has no lag phase, and new polymer formation is most rapid at the start of assembly, when the greatest concentration of free subunits is available.

FtsZ assembly cannot be fully described by either of the above models. Unlike tubulin, FtsZ can polymerize into linear, single-stranded polymers equivalent to tubulin protofilaments; these protofilaments are stable in the absence of any lateral interactions (14–16). In the presence of GDP, FtsZ assembles into linear polymers with nearly isodesmic properties (15), in keeping with standard polymerization models. However, GTP-containing FtsZ protofilaments were found to assemble cooperatively (4,9,10). Cooperativity was first observed as a sharp critical concentration for assembly and for GTP hydrolysis, which acts as an indirect measure of FtsZ assembly (4–10). More recently, Chen et al. (9) and Chen and Erickson (10) developed the first truly quantitative methods for following FtsZ polymerization kinetics, and found that FtsZ exhibits concentration-dependent lags under conditions in which polymers are single-stranded. The hydrolysis of GTP cannot play an essential role in this behavior, because cooperativity was observed even in the absence of hydrolysis (9).

The assembly kinetics of FtsZ suggest that polymerization involves a dimer nucleus. The concentration-dependent lags of FtsZ could be closely fit by a mechanism first used to model actin assembly (17,18). In the actin model, a first-order monomer activation step is followed by a second-order reaction in which two activated subunits form an unstable dimer. Only after dimerization does subsequent elongation become favorable.

Though the actin mechanism fits FtsZ's assembly kinetics, it is physically insufficient to explain the behavior of single-stranded, linear polymers such as FtsZ (9,10). For trimer interfaces to be more stable than dimer interfaces, a subunit must somehow be affected by the presence of a protein to which it is not primarily bound. This can be readily explained in helical polymers (or in multistranded polymers, which are versions of a tight helix). In helical polymers, subunits farther along the chain can twist around to make direct contacts with a new subunit being added to the end of the polymer (Fig. 1 B). In strictly linear polymers, such communication at a distance is less easy to explain, and any information on the polymerization state would need to be passed directly through nearest-neighbor subunits.

One explanation might be that FtsZ polymers are not truly linear. Gonzalez et al. found evidence that long FtsZ polymers can circularize to produce cooperativity (19). They used analytical ultracentrifugation to monitor the size of FtsZ polymers at various protein concentrations, and found that at high concentrations, smaller structures (<10 Svedbergs) were less prevalent than larger ones (≈12 Svedbergs), and that FtsZ protofilaments appeared by electron microscopy to circularize when they reached lengths of 50-200 subunits. However, this effect cannot explain the cooperativity seen by Chen et al. (9) and Chen and Erickson (10), in which polymers do not circularize, and the apparent nucleus size is two. More recent results confirm that cooperativity persists when protofilaments are not circularized (20).

Another possibility is that within linear FtsZ polymers, a binding event on one side of a subunit can influence the conformation of the binding surface on the opposite side of the protein. Several groups recently proposed such a model, along with a brief thermodynamic analysis (3,20–22). We present a more comprehensive model and analysis for allosteric cooperative polymers in which conformational changes alter the affinity between subunits. We use methods from matrix algebra to analyze the equilibrium behavior of the model. Our mathematical framework can represent allosteric polymerization systems with a variety of biochemical interpretations, some of which can show cooperativity, and others of which cannot.

THEORY

In our model for linear polymerization (Fig. 2 A), subunits convert between two different conformations. Subunits in either conformation can polymerize, but they do so with different affinities: “L” subunits associate with low affinity (Fig. 2 A, circles), whereas “H” subunits associate with high affinity (Fig. 2 A, squares). Note that the L and H conformations do not necessarily represent GDP- and GTP-bound FtsZ; FtsZ can exhibit cooperative polymerization even in the absence of GTP hydrolysis (9). Instead, L and H represent different conformations of a single chemical species, and the two conformations are in equilibrium with each other. We call the equilibrium constant for the conformational change in monomers KC.

FIGURE 2.

Models for allosteric linear polymerization. (A) Generic allosteric model for assembly of single-stranded polymers. Subunits can switch between two conformations that associate with different affinities. The five independent equilibrium constants are shown in black. (B) Monomer activation, followed by isodesmic assembly. In this version of the model, only H monomers are competent for assembly (KLL = KLH = KHL = 0). (C) Only one end of the subunit changes conformation. Here, heterodimers with different polarities have different affinities, such that KHL = KHH whereas KLH = KLL.

The two types of monomer can associate to form four types of dimers (LL, LH, HL, and HH), with four independent association constants (KLL, KLH, KHL, and KHH). We assume that two H monomers have the highest affinity for each other (KHH > KLH, KHL, and KLL). If a polymer is asymmetric or “polar,” the two ends of a subunit will not behave identically. The two ends of cytoskeletal polymers are often called the plus and minus ends; here we arbitrarily define an LH dimer as having the L subunit at its plus end. If an L subunit binds to the plus end of an H subunit with a different affinity than it binds to the minus end, KLH will not equal KHL.

Association constants for polymer elongation are assumed to be identical to those for dimerization. Thus our model differs from multistranded polymerization in that subunit affinity does not depend on the length of the polymer being elongated. Affinities depend only on the conformation of the subunit at the end of a polymer, and on the conformation of the monomer joining the chain.

For polymer assembly to be cooperative, the initial formation of a dimer from two monomers should be unfavorable. Monomer interactions will be weak if the majority of monomers are in the L conformation. Thus, in cooperative polymers, the L conformation must be inherently more stable than the H conformation (KC ≪ 1). However, for polymers to be stable and for elongation to be favorable, subunits in polymers should change from L to H. Changing to the H conformation will occur in polymers if the opportunity for increased interactions with neighboring subunits can compensate for the energetic cost of changing conformations.

Calculations used to detect cooperativity

We wanted to determine whether a polymerization system could exhibit the properties described above and show nucleated assembly. The presence of a sharp critical concentration was used as an indicator of cooperativity. To detect the existence of such a critical concentration, we determined the concentration of subunits in polymers and monomers as a function of total protein concentration. Our calculations parallel those of the classic analysis of isodesmic polymerization by Oosawa and Kasai in 1962 (11). In Table 1, the terms and expressions used for the isodesmic case are shown on the left, with the parallel terms and expressions for our allosteric model shown on the right. (Note that all analyses refer to reactions at equilibrium.) More detailed definitions and derivations appear in the Appendix.

TABLE 1.

Expressions used to determine the presence of a critical concentration

| Isodesmic polymers* | Allosteric linear polymers | |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical reactions | ||

|

||

|

† †

|

|

|

||

| Terms in chemical reactions | ||

| Polymers of length n |  |

|

| Monomers |  |

L |

|

||

| Equilibrium constant(s) for assembly |  |

|

| Concentration calculations | ||

| Polymers of length n |  |

zn = the sum of entries in Zn, where |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Subunits in polymers of length n |  |

|

| Total protein‡ |  |

zo = the sum of the entries in Zo, where |

§ §

|

||

| Subunits in polymers‡ |  |

p = the sum of entries in P, where |

§ §

|

||

| Total monomers‡ | z1 | z1 = L + H = L(1 + KC) |

| Maximum monomers at equilibrium‡ |  |

|

For more detailed definitions and derivations, see Appendix.

Based on Ossawa and Kasai (11).

X represents a subunit whose conformation is unspecified, Xn a chain of such subunits, LXn the class of polymers that have an L subunit at the plus end, and LLXn the class of polymers with two L subunits at the plus end.

Four expressions are used to create critical concentration graphs such as those in Figs. 1, 3, and 5: total protein (zo), subunits in polymer (p), total monomer (z1), and maximum monomer at equilibrium ( ).

).

I is the identity matrix.

In isodesmic polymers, subunits assemble into linear chains with a single association constant KA, no matter the length of the polymer. Table 1 (left) shows how the total protein concentration (zo) and the concentration of subunits in polymers (p) can be calculated from the monomer concentration (z1) and KA. First, the concentration of polymers of any length (zn) can be determined from their equilibrium with polymers one subunit shorter (zn−1). Because the concentration of dimers is related to that of monomers, the concentration of trimers is related to that of dimers, the concentration of tetramers is related to that of trimers, etc., we can bootstrap our way to determining the concentration of polymers of any given length, based only on the monomer concentration and the equilibrium constant KA. Next, to determine the concentration of subunits in such polymers, one needs to multiply the concentration of polymers by their length n. For example, for every 1 μM of trimers, there are 3 μM of subunits in these trimers. Finally, the total protein concentration is the sum of subunits in species of every possible length. The concentration of subunits in polymers is the sum for species the size of a dimer and larger.

Parallel calculations can be performed for our allosteric model (Table 1, right). However, in our model, there are four possible elongation reactions with four different association constants. Matrices provide a convenient way to analyze all four reactions simultaneously. The four association constants are stored in a 2 × 2 matrix KA, whereas Zn represents 2 × 1 vectors that store the concentration of polymers of a particular length, separated into two polymer classes, depending on whether the subunit at the plus end is an L or an H. Using this formulation, we input the five equilibrium constants and a series of L monomer concentrations to determine whether a particular polymerization scheme will have a sharp critical concentration.

The apparent affinity for polymer ends and the maximum monomer concentration at equilibrium

In cooperative polymerization systems, the critical concentration represents not only the minimum protein needed for polymers to form, but also the maximum concentration of monomers that can exist in solution at equilibrium (Fig. 1 C). The value of the critical concentration is determined by the affinity of monomers for polymer ends (12). Although noncooperative systems do not have a sharp threshold for polymerization, they still have a characteristic maximum monomer concentration at equilibrium (Fig. 1 C), and this concentration is similarly determined by the affinity of subunits for polymer ends. We call these values Ke, for the apparent association constant for elongation, and  for the maximum monomer concentration at equilibrium. They are inversely related, such that

for the maximum monomer concentration at equilibrium. They are inversely related, such that

For isodesmic polymers, the maximum monomer concentration at equilibrium is determined solely by KA, the single association constant between subunits. For the allosteric model, the maximum monomer concentration is determined not by a single chemical reaction but by a weighted average of the different reactions that can occur at the end of a polymer. Its value therefore depends on all five equilibrium constants, KLL, KLH, KHL, KHH, and KC. Table 1 shows the expression for  in the allosteric model; this expression was determined based on the fact that the monomer concentration approaches a maximum value as the total protein concentration approaches infinity (see Appendix for the derivation). The expression for

in the allosteric model; this expression was determined based on the fact that the monomer concentration approaches a maximum value as the total protein concentration approaches infinity (see Appendix for the derivation). The expression for  given in Table 1 applies to any version of the allosteric model, whether it is cooperative or not.

given in Table 1 applies to any version of the allosteric model, whether it is cooperative or not.

For cooperative versions of the allosteric model, the apparent association constant for polymer ends is Ke = KCKHH. We will show that polymerization is cooperative only if KC ≪ 1 and KHH ≫ KLL, KLH, and KHL. Under these circumstances and assuming that KCKHH ≫ KLL, the expression for  shown in Table 1 reduces to

shown in Table 1 reduces to

|

(1) |

The critical concentration thus depends only on the energetic cost of a subunit changing conformations (KC) and the energetic benefit of forming a strong interface between H subunits (KHH).

RESULTS

The allosteric polymerization model can exhibit different degrees of cooperativity

We investigated which versions of our allosteric polymerization model could exhibit the sharp critical concentrations that are the distinguishing hallmarks of cooperative polymerization. We varied the five equilibrium constants and used the expressions shown in Table 1 to determine how monomer and polymer concentrations depend on total protein concentration.

To determine which combinations of parameters would produce the most cooperative assembly, the five equilibrium constants were systematically varied. We started with an isodesmic system in which all five equilibrium constants = 1. Each parameter was then increased or decreased by an order of magnitude, both individually and in all combinations. As predicted, the greatest cooperativity resulted when KHH was as large as possible, and KC, KLL, KLH, and KHL were as small as possible (Fig. S1 A in Supplementary Material, Data S1). In a cooperative system, monomers should not associate easily, and thus should primarily be in the low-affinity conformation (KC ≪ 1). In contrast, subunits in polymers should be in the high-affinity conformation, to associate strongly (KHH ≫ KLL). It will be shown that not only KLL but also both KLH and KHL must be small for a system to be cooperative and nucleation to be unfavorable relative to elongation.

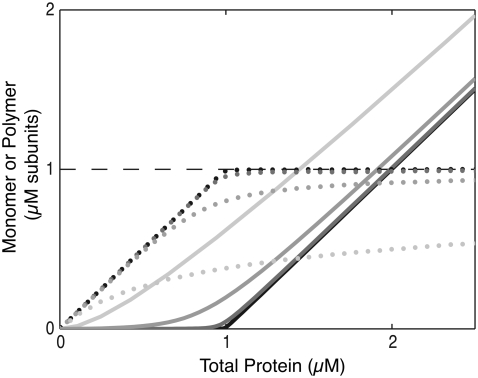

We next varied the equilibrium constants over a wider range. To simplify the analysis, we defined all five variables in terms of a single parameter, ɛ. KC, KLL, KLH, and KHL were set equal to ɛ, whereas KHH was set equal to 1/ɛ. For each parameter combination, the concentrations of subunits in polymers and monomers were plotted relative to the total protein concentration (Fig. 3 and Fig. S1 B in Data S1).

FIGURE 3.

Conformational changes can produce cooperativity in single stranded polymers. (Solid line) p, protein in polymer at equilibrium; (dotted line) z1, the monomer concentration at equilibrium; (dashed line)  the maximum monomer concentration. Lines from lightest gray to darkest black: ɛ = 1, 1 × 10−2, 1 × 10−4, and 1 × 10−6, where KHH = 1/ɛ and KC, KLL, KLH, and KHL = ɛ. When all association constants are identical (ɛ = 1), isodesmic polymerization results. When KHH is greater than all other equilibrium constants (ɛ < 1), a threshold for assembly emerges; the smaller the value of ɛ, the greater the cooperativity.

the maximum monomer concentration. Lines from lightest gray to darkest black: ɛ = 1, 1 × 10−2, 1 × 10−4, and 1 × 10−6, where KHH = 1/ɛ and KC, KLL, KLH, and KHL = ɛ. When all association constants are identical (ɛ = 1), isodesmic polymerization results. When KHH is greater than all other equilibrium constants (ɛ < 1), a threshold for assembly emerges; the smaller the value of ɛ, the greater the cooperativity.

With appropriate parameters, the model can achieve virtually ideal cooperativity. In Fig. 3, the least sharply curved, light gray lines at the center of the plot correspond to isodesmic polymerization, where ɛ = 1. As the value of ɛ approaches zero, the assembly shows increasingly sharp critical concentrations (darker black lines). Note that for all systems, as the total subunit concentration increases, the equilibrium monomer approaches its maximum possible value,

Relative abundance of different polymer species

For a polymerization system to be cooperative, one or more species at the start of the polymerization pathway must be extremely unstable and vanishingly rare, creating a bottleneck en route to the formation of stable nuclei and long polymers. For multistranded polymers such as actin or microtubules, small oligomers such as dimers or trimers are unstable and rare (11,23–25). Only when oligomers reach the size of the nucleus is assembly stabilized by the formation of a high-affinity binding site for subunits (Fig. 1 B). For our allosteric model, we wanted to determine which species are unstable and could act as similar bottlenecks to the formation of more stable polymers.

The abundance of all polymer species of length ≤4 was calculated for several versions of the model with different equilibrium constants. For each polymerization system, we first determined the value of L when total protein zo = 10 μM. We then calculated the concentration of other species from their equilibrium with L subunits. For example, the concentration of LH = KCKLHL2. MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) was used to generate results here and throughout this study.

As predicted, in the cooperative systems analyzed here, most monomers are in the L conformation, whereas subunits in polymers are in the H conformation. Table 2 lists the most abundant species of each length (n ≤ 4); the concentrations of all species of length ≤4 are available in Table S1 in Data S1.

TABLE 2.

Most abundant polymer species in different versions of the model

| Model | Isodesmic assembly | ɛ = 1 × 10−4 | Monomer activation + isodesmic assembly | Segregated assembly of Ln and Hn | Only one end changes conformation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperative? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Equilibrium constants | |||||

| KC | 0 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 |

| KLL (μM−1) | 1 | 1 × 10−4 | 0 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 |

| KLH (μM−1) | 0 | 1 × 10−4 | 0 | 0 | 1 × 10−4 |

| KHH (μM−1) | 0 | 1 × 104 | 1 × 104 | 1 × 104 | 1 × 104 |

| KHL (μM−1) | 0 | 1 × 10−4 | 0 | 0 | 1 × 104 |

| Most abundant species at equilibrium*† (μM) | |||||

| Monomers | L (0.73) | L (1.00) | L (1.00) | L (1.00) | L (0.73) |

| Dimers | LL (0.53) | LL (9.93 × 10−5) | HH (9.93 × 10−5) | LL (9.93 × 10−5) | HL (0.53) |

| HH (9.93 × 10−5) | HH (9.93 × 10−5) | ||||

| Trimers | L3 (0.39) | H3 (9.90 × 10−5) | H3 (9.90 × 10−5) | H3 (9.90 × 10−5) | H2L (0.39) |

| Tetramers | L4 (0.28) | H4 (9.87 × 10−5) | H4 (9.87 × 10−5) | H4 (9.87 × 10−5) | H3L (0.28) |

Results are calculated for 10 μM total protein.

Species not shown are at least 100 times rarer than those of the same length shown above. The total concentration of polymers of each length is thus approximately equal to the concentrations of the listed species. Concentrations of all polymer species length ≤4 are available in Table S1 in Data S1.

Dimers are abundant even in cooperative systems

In contrast to multistranded polymerization, for cooperative linear polymerization, short oligomers can be more abundant than longer ones, such that z1 > z2 > z3 > z4 (Table 2 and Table S1 in Data S1). This result holds for all the cooperative systems modeled here, meaning that the rarity of small oligomers is not a diagnostic characteristic of cooperativity for allosteric linear polymers. However, particular subclasses of both monomers and dimers are in fact quite rare in cooperative systems. In all versions of the model that exhibit a sharp critical concentration, H monomers and heterodimers (LH or HL) are unstable and therefore rare (Table S1 in Data S1). It will be seen that HH dimers form the nuclei in these cooperative systems. To form an HH dimer, H monomers and/or L/H heterodimers must form first, and these unstable intermediates limit the rate of nucleation.

The finding that small oligomers are more abundant than larger ones does not hold for all versions of the model. For instance, one can represent a system in which LH heterodimers assemble isodesmically to form (LH)n polymers (KLL = KHH = 0; KLH ≫ KHL). In this case, z2 > z1, and z4 > z3. Assembly in this system is not cooperative (data not shown).

It should be noted that before the equilibrium polymer length distribution is reached, the most abundant polymers may be of intermediate length. The time to reach the final equilibrium distribution of polymer species can be many orders of magnitude longer than the time for the free monomer concentration to reach its equilibrium value (26).

Cooperative conformational transitions within polymers

In the cooperative systems modeled here, Hn polymers are exceedingly stable relative to polymers containing even a single L subunit. The Ln polymers can be metastable, however, meaning that it is unfavorable for a single subunit within an Ln polymer to change into the H conformation, but once one has done so, it can trigger the rest of the polymer's subunits to follow.

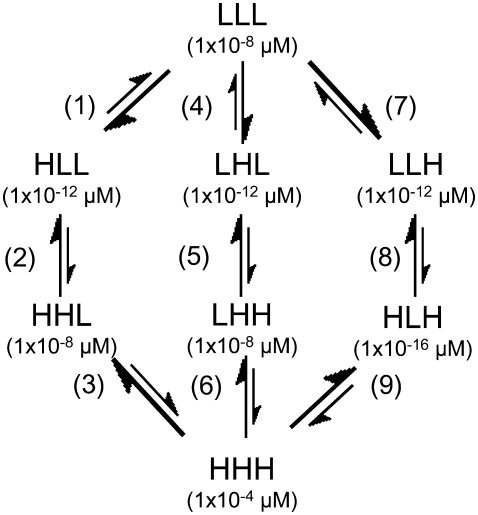

These points are illustrated in Fig. 4 and Table 3, where we examine conformational changes within trimers, using equilibrium constants from the case of ɛ = 10−4 (see Table 2 for individual Keq values). In Fig. 4, all eight possible trimer configurations are shown, along with their equilibrium concentrations at 10 μM total protein. For the parameters selected, H3 trimers are four orders of magnitude more abundant than any other species. Although L3 trimers are much less abundant than H3 trimers, they are more abundant than polymers with only a single H subunit. If a single subunit in an L3 polymer changes into an H, it experiences all the energetic cost of the conformational change, without the compensating benefits of forming strong interfaces.

FIGURE 4.

Conformational changes within trimers. The eight possible trimer configurations are shown, along with their equilibrium concentration when ɛ = 1 × 10−4 and total protein = 10 μM. L3 trimers can convert to H3 trimers via three possible pathways. H3 trimers are the most stable species, but L3 trimers are metastable. See Table 3 for more information.

TABLE 3.

Conformational changes within trimers

|

Keq*†

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Generic model | ɛ = 1 × 10−4* | |

| Net reaction | ||

|

|

1 × 104 |

| Three possible pathways | ||

|

(1) KCKHL/KLL | 1 × 10−4 |

| (2) KCKHH/KLL | 1 × 104 | |

| (3) KCKHH/KHL | 1 × 104 | |

|

(4)

|

1 × 10−4 |

| (5) KCKHH/KHL | 1 × 104 | |

| (6) KCKHH/KLH | 1 × 104 | |

|

(7) KCKLH/KLL | 1 × 10−4 |

| (8) KCKHL/KLL | 1 × 10−4 | |

(9)

|

1 × 1012 | |

Individual equilibrium constants are those given in Table 2.

Equilibrium constants are dimensionless.

Three possible pathways are shown by which an L3 trimer can convert into an H3 trimer (Fig. 4, Table 3). Although it is unfavorable for a single subunit in the trimer to convert to an H (reactions 1, 4, and 7), once the first subunit has done so, conversion of its immediate neighbors also becomes favorable (reactions 2 and 5). In this way, the change of a single subunit to the H conformation might trigger an entire Ln polymer to change conformation and become an Hn polymer.

Nucleation versus elongation: Net energetics

The formation of an HH nucleus is not as energetically favorable as the elongation of an Hn polymer. Because species other than L monomers and Hn polymers are rare (Table 2), we can assume that nucleation and elongation occur predominantly through the net reactions L + L ⇔ HH and L + Hn ⇔ Hn+1, respectively. Both reactions involve reactants that are relatively abundant. However, nucleation is proportional to  whereas elongation is proportional to KCKHH (Table 4). Nucleation is therefore less favorable by a factor of KC, and since in cooperative systems KC ≪ 1, this difference can be quite large.

whereas elongation is proportional to KCKHH (Table 4). Nucleation is therefore less favorable by a factor of KC, and since in cooperative systems KC ≪ 1, this difference can be quite large.

TABLE 4.

Nucleation and elongation pathways for cooperative systems

|

Keq*

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic model | ɛ = 10−4† | Monomer activation + isodesmic assembly† | ||

| Nucleation | ||||

| Net reaction |  |

|

10−4 | 10−4 |

| Pathways‡ | ||||

n1)

|

(a) KC | 10−4 | 10−4 | |

| (b) KC | 10−4 | 10−4 | ||

| (c) KHH | 104 | 104 | ||

n2)

|

(a) KC | 10−4 | 10−4 | |

| (b) KL/H§ | 10−4 | 0 | ||

| (c) KCKHH/KL/H | 104 | |||

n3)

|

(a) KLL | 10−4 | 0 | |

| (b) KCKL/H/KLL | 10−4 | |||

| (c) KCKHH/KL/H | 104 | |||

| Elongation | ||||

| Net reaction | L + Hn ⇔ Hn+1 | KCKHH | 1 | 1 |

| Pathways‡ | ||||

e1)

|

(a) KC | 10−4 | 10−4 | |

| (b) KHH | 104 | 104 | ||

e2)

|

(a) KL/H | 10−4 | 0 | |

| (b) KCKHH/KL/H | 104 | |||

Equilibrium constants for unimolecular reactions are dimensionless; those for bimolecular reactions are μM−1.

Individual equilibrium constants are those given in Table 2.

Underlined intermediates are unstable and rare.

KL/H = KLH + KHL.

It is helpful to think of the equilibrium constants in terms of the chemical reactions they represent: KC is related to the energetic cost for a subunit to change into the H conformation, whereas KHH is related to the energetic benefit of then being able to form more stable polymer interfaces. During nucleation, the energetic cost of converting two L subunits into two H subunits is only compensated for by the formation of a single stable H-H interface. In contrast, during polymer elongation, the formation of an H-H interface requires only a single subunit to convert into the H conformation. Because subunits at the ends of polymers are already held in the H conformation, adding a subunit to a preformed polymer has the same benefit but fewer costs than nucleating a new polymer.

The net elongation reaction shown in Table 4 is consistent with our mathematical analysis of the critical concentration described in Eq. 1. and in the Appendix. The critical concentration will be equal to the apparent dissociation constant for monomers from polymer ends, or 1/KCKHH.

The result is a polymer with extremely strong internal interfaces (Keq = KHH), moderate interactions at polymer ends (Keq = KCKHH), and weak initial interactions between monomers (Keq = KLL). These properties mimic those seen in multistranded polymers such as actin and tubulin. Cooperativity is related to Kn/Ke, with smaller values of Kn/Ke representing greater cooperativity (12,13,27). Here, cooperativity =  The cooperativity of polymerization therefore depends only on the energetic cost of the extra subunit changing conformations. (This is an approximation that applies to the most cooperative systems; see the Appendix for a more general definition of cooperativity.)

The cooperativity of polymerization therefore depends only on the energetic cost of the extra subunit changing conformations. (This is an approximation that applies to the most cooperative systems; see the Appendix for a more general definition of cooperativity.)

Nucleation versus elongation: unstable intermediates

A second way to understand why nucleation is unfavorable relative to elongation is to examine the intermediates that form in the different reaction pathways (Table 4). Several possible pathways can lead to the formation of an HH nucleus or to the elongation of an Hn polymer. Which particular pathway will dominate during polymerization will depend on the specific equilibrium and rate constants chosen. Although both nucleation and elongation require the formation of unstable intermediates, in all cooperative cases, the nucleation pathways include more unfavorable steps than do the elongation pathways.

During nucleation, an HH dimer can be formed from two L monomers via the three possible routes shown in Table 4. The three pathways are: n1), two monomers first simultaneously change into the high-affinity conformation and then collide, n2), only one of the two subunits changes conformation before the dimer forms, and n3), an LL dimer forms before either of the two subunits have converted into the H conformation. In cooperative systems, formation of the intermediates underlined in Table 4 is unfavorable, whereas the last step in the pathway, the formation of an HH dimer from these unstable intermediates, is favorable. Thus although monomers and dimers are abundant as a group, specific subclasses of monomers and dimers that precede the formation of an HH nucleus are unstable and act as bottlenecks to polymerization.

Elongation uses similar pathways as nucleation, requiring an unfavorable step to precede the favorable formation of an Hn+1 polymer (Table 4, e1 and e2). However, because the subunit at the end of the polymer has already changed conformation, one unfavorable step that was necessary for a nucleation pathway is not necessary for the equivalent elongation pathway. As a result, the rate-limiting steps during elongation are less restrictive than those during nucleation.

Can other versions of the model be cooperative?

We next consider whether other parameter combinations can exhibit cooperativity. Up to this point, we have forced the equilibrium constants to be related by the factor ɛ, where KHH = 1/ɛ, and the other four equilibrium constants = ɛ. We now discard this constraint and test several variations of the general model (Table 2 and Fig. 5). We find that a system will be cooperative as long as nucleation requires an unfavorable reaction that is not necessary for elongation. This unfavorable reaction is, in general, an extra conformational change that is necessary for two subunits to form a stable dimer, but unnecessary for a single subunit to add to the end of a polymer.

FIGURE 5.

Determining which versions of the model exhibit cooperativity. (Solid line) p, protein in polymer at equilibrium; (dotted line) z1, the monomer concentration at equilibrium; (dashed line)  the maximum monomer concentration. (A) Isodesmic polymerization is not cooperative. (B) When ɛ = 1 × 10−4, assembly is cooperative. (C) Monomer activation followed by isodesmic assembly is cooperative. (D) When L and H subunits assemble into separate polymers, polymerization is cooperative. (E) When only one end of the subunit changes conformation, assembly is not cooperative. The results were generated with MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA), using the equilibrium constants shown in Table 2.

the maximum monomer concentration. (A) Isodesmic polymerization is not cooperative. (B) When ɛ = 1 × 10−4, assembly is cooperative. (C) Monomer activation followed by isodesmic assembly is cooperative. (D) When L and H subunits assemble into separate polymers, polymerization is cooperative. (E) When only one end of the subunit changes conformation, assembly is not cooperative. The results were generated with MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA), using the equilibrium constants shown in Table 2.

Isodesmic assembly

Our polymerization framework can be used to model simple isodesmic polymerization. Here we set all equilibrium constants other than KLL equal to zero (thus KC, KHH, KLH, and KHL = 0). As expected, because dimer formation is energetically identical to polymer elongation (Fig. 1 A), this system does not show a sharp critical concentration (Fig. 5 A). Isodesmic polymerization can also be realized in other ways, e.g., by setting KLL = KLH = KHL = KHH (Fig. 3).

Monomer activation followed by isodesmic assembly

In contrast, cooperativity can emerge from a variation of isodesmic polymerization in which a monomer activation step must precede polymerization (Fig. 2 B). In this model, L monomers are abundant but are completely incapable of assembly, so that polymerization is only possible after a subunit has changed into the H conformation. This polymerization mechanism was also recently analyzed by Huecas et al. (20).

To prevent L subunits from participating in polymerization, we set KLL, KLH, and KHL = 0 (Table 2). This simplified model now has only two relevant equilibrium constants, KC and KHH. This version of the model produces a sharp critical concentration, as long as KC is very small relative to KHH (Fig. 5 C).

Here again, cooperativity emerges because of the energetic difference between nucleation and elongation. The only routes to forming a dimer nucleus or to elongating a polymer are via n1 and e1 in Table 4. As above, during nucleation, two subunits must change to the H conformation, whereas during elongation, only one subunit must do so. As a consequence, there is a factor of KC difference between the equilibrium constants for the two reactions (20).

Segregated assembly of Ln and Hn polymers

In a related variation of the model, L subunits can associate weakly with other L subunits, but mixed polymers cannot form. (i.e., 0 = KLH = KHL, but 0 < KLL ≪ KHH, Table 2). Here, if a reaction starts with all proteins in the L form, subunits in small Ln oligomers will need to dissociate and change conformation before they can assemble into stable Hn polymers. As long as KC and KLL are small relative to KHH, this system will also exhibit cooperativity (Fig. 5 D).

Conformational changes at only one end of the subunit

Occasionally, allosteric models for cooperativity have been depicted in which only one end of the subunit changes conformation (3). However, we found that if a conformational change affects only one end of a polymer subunit, assembly cannot be cooperative. Using an independent method of analysis, Erickson also achieved this result (H. P. Erickson, Duke Univesity Medical Center, personal communication, 2007). In this version of the model (Fig. 2 C), an H subunit can associate tightly with the plus end of an L subunit, but not with the minus end. Thus KHL = KHH, whereas KLH = KLL (Table 2). Our analysis shows that such a model does not produce sharp critical concentrations (Fig. 5 E).

The lack of cooperativity can be understood by examining the relative abundance of different species at equilibrium (Table 2 and Table S1 in Data S1). The most abundant dimers and polymers contain a single L subunit at their minus end. At this end of the polymer, the energetic advantage to forming a stable interface can be gained without the cost of changing the terminal subunit to the higher-energy H conformation. (At the other end of the polymer, a more stable interface is only achieved when the terminal subunit has changed to an H.)

This system does not show cooperativity because at all steps, nucleation reactions are energetically identical to elongation reactions. These reactions are different from those in Table 4 in that the pathways end with the formation of an HnL polymer. Because KHL = KHH, the following nucleation and elongation pathways are energetically identical:

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

as are a second pair of pathways:

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

In all cases, the net reactions for nucleation and polymerization occur with the same equilibrium constant, Kn = Ke = KCKHL = KCKHH. Similarly, the intermediates that occur during nucleation are exactly as stable as those that occur during elongation (reactants convert into intermediates with a Keq = KLL in Eqs. 2 and 3, and KC in Eqs. 4 and 5).

Stability of mixed L/H interfaces affects the degree of cooperativity

Similar analyses to those above show that if all L/H interfaces have a high affinity regardless of polarity (e.g., KLL ≪ KLH = KHL = KHH), assembly will not be cooperative. Polymers will contain of a mixture of L and H subunits, although no two L subunits will be adjacent to one another (data not shown).

Alternatively, if mixed interfaces have an intermediate affinity (e.g., KLL ≪ KLH = KHL ≈ KCKHH), subunits at the ends of polymers can be a mixture of L and H subunits, whereas internal subunits will remain entirely H. Cooperativity will be reduced in proportion to the appearance of L subunits at polymer ends (data not shown). As described above, if L subunits are stable at the ends of polymers, then L/H heterodimers will also be stable, making dimerization and elongation energetically equivalent. (See the Appendix for the quantitative relationship between cooperativity and L/H heterodimer stability.)

Conformational changes that occur only in longer polymers

In the cooperative systems explored so far, subunits in dimers are likely to change into the H conformation (Table 2). However, polymerization systems can exist in which subunits in dimers remain in the L conformation and only change to the H conformation in trimers or larger polymers. In these cases, the apparent nucleus size will be larger than a dimer (data not shown).

Because the concentration of HH dimers is proportional to  whereas the concentration of LL dimers is proportional to KLL, HH will be more abundant than LL whenever

whereas the concentration of LL dimers is proportional to KLL, HH will be more abundant than LL whenever  as seen for several systems in Table 2). Subunits will change to the H conformation in trimers, but not in dimers, whenever

as seen for several systems in Table 2). Subunits will change to the H conformation in trimers, but not in dimers, whenever  (LL is more abundant than HH) but

(LL is more abundant than HH) but

More generally, subunits in polymers of length n will change into the H conformation only when the total benefit of forming n − 1 polymer interfaces outweighs the cost of n subunits changing conformation (( ). Note that in cooperative cases, subunits will change conformation in a concerted manner, so that individual polymers will tend to have a uniform subunit conformation, either Ln or Hn. Whenever small Ln oligomers are stable, cooperativity will be reduced (see the Appendix). Similarly, polymers with mixed subunit conformations can be produced if L/H interfaces are strengthened, but cooperativity will again be diminished.

). Note that in cooperative cases, subunits will change conformation in a concerted manner, so that individual polymers will tend to have a uniform subunit conformation, either Ln or Hn. Whenever small Ln oligomers are stable, cooperativity will be reduced (see the Appendix). Similarly, polymers with mixed subunit conformations can be produced if L/H interfaces are strengthened, but cooperativity will again be diminished.

DISCUSSION

We have developed an allosteric model for polymerization that can allow linear, single-stranded polymers to assemble cooperatively. In this model, polymer stability is determined not by the size of an oligomer but by the conformation of its subunits. We used matrix algebra methods to calculate the concentrations of different polymer species at equilibrium. This analysis allows us to determine whether there is a sharp critical concentration for assembly, and also which nucleation and elongation pathways might dominate for a particular system.

In cooperative systems, monomers are largely in the low-affinity conformation, whereas subunits in polymers are largely in the high-affinity conformation. During polymerization, the thermodynamic price of changing to the higher-affinity conformation must be paid for by the benefit of forming a more stable interface. Dimers gain this benefit only if both subunits change conformations. Unstable intermediates precede the formation of the first favorable H-H interface, making nucleation kinetically difficult. However, once an HH nucleus has formed, the assembly of additional subunits becomes more favorable, both thermodynamically and kinetically. Subunits in preformed polymers are already in the H conformation, so that polymer elongation requires only a single subunit to undergo an unfavorable conformational change. Thus a smaller price is paid for the benefit of forming a stable interface at the ends of polymers than in dimers. Huecas et al. found similar results for one specific polymerization pathway (20).

Our allosteric model produces many of the characteristics of nucleated, multistranded polymers. It can produce sharp critical concentrations for assembly. Associations between individual monomers are weak, whereas those between subunits and polymer ends are of moderate affinity, and associations at the center of a polymer are quite strong. As a result, dynamics would be predicted to occur primarily at polymer ends, whereas polymer fragmentation should be relatively rare. The existence of unfavorable steps at the start of polymerization suggests that these systems will also show the kinetic lags typical of cooperative assembly. Another traditional characteristic of multistranded cooperative assembly, i.e., that the smallest oligomers are quite rare, appears to be missing from the allosteric model, where even dimers are abundant. However, this discrepancy is deceptive. In the model presented here, there are several types of monomers and of dimers, and subcategories of these species (H, LH, and HL) form the rare and unstable intermediates through which nucleation reactions must pass.

Advantage of the matrix method

The analytic framework developed here represents a general solution for linear allosteric polymerization. It is quite versatile; by changing the relative values of equilibrium constants, we can simulate assembly systems with a variety of biochemical properties. The use of matrices allows us to analyze systems in which several types of elongation reaction can occur simultaneously. We can therefore include the effects of all possible association events without making any a priori assumptions about the nature of the interactions between subunits or the assembly pathways that will dominate polymerization.

This generic approach lets us resolve a seeming contradiction between two recent analyses of linear polymerization. H. P. Erickson conducted an unpublished study of allosteric linear polymers that cannot exhibit cooperativity (H. P. Erickson, Duke University Medical Center, personal communication, 2007). In contrast, Huecas et al. described conformational changes that do produce cooperativity (20). Both previous studies made assumptions about the specific effect that a conformational change will have on subunits' interactions. By limiting assembly to one type of elongation reaction, these authors did not need to use matrix algebra. However, the two studies represent different subcases of our more general model, i.e., monomer activation + isodesmic polymerization, which can produce cooperativity, and allosteric changes at one end of the subunit, which cannot produce cooperativity.

Different biochemical mechanisms that the model can represent

In agreement with the results of H. P. Erickson (Duke University Medical Center, personal communication, 2007), we show that a conformational change must affect both ends of a subunit for assembly to be cooperative. Data for tubulin suggest that conformational changes do affect both ends of each protein, as the angles of both interdimer and intradimer interfaces change between the curved versus the straight polymer conformations (28–31). However, proposals for allosteric cooperativity have not always realized that conformational changes at both ends of a subunit are an essential feature of the model (3).

A variety of different polymerization mechanisms can produce cooperativity. For example, if pathways n1 and e1 dominate, a unimolecular activation step must occur before assembly. This mechanism, which we call monomer activation + isodesmic assembly, is equivalent to that proposed by Huecas et al. (20), and could resemble the salt-induced conformational changes necessary for actin polymerization (17,18). In a related version of the model (segregated assembly of Ln and Hn), the L subunits can associate, but only with each other.

In a third version of cooperative polymerization, induced conformational changes occur after a subunit adds to a polymer. This mechanism resembles that proposed for amyloid fibril growth (32–35). Amyloid subunits were found to associate reversibly with preformed fibrils, and then to change to a “locked” conformation that can no longer readily dissociate. Similarly, in our system, if polymerization occurs through pathways n2 and e2, a subunit changes into the high-affinity conformation only after associating with a preformed Hn polymer. The ability of neighboring subunits to influence each other presents the interesting possibility that polymers may undergo concerted conformational changes. Cooperative conformational changes have long been known to occur in small oligomers such as hemoglobin, but only recently has their propagation through larger protein arrays been considered (36). Here such concerted changes might produce behaviors that resemble the dynamic instability in microtubules. Evidence for such concerted shape changes was seen in taxol-stabilized tubulin protofilaments (37). The cooperative nature of such transitions could delay conformational changes in individual subunits until triggering events such as GTP hydrolysis occur in neighboring subunits, and would make the degree of curvature in a polymer nonlinearly related to the number of GDP-bound subunits.

The method developed here can readily be extended to represent the linear assembly of polymers in which subunits can take on more than two conformations. The number of possible conformations would determine the number of entries in the matrices Zn and KA, with each entry in KA representing equilibrium between a particular type of monomer and polymer ends. The calculation of the maximum monomer concentration at equilibrium (representing the critical concentration for cooperative systems) and of other related properties would proceed in a manner parallel to that presented here.

What might the L and H conformations represent?

Several kinetic experiments found that first-order reactions precede the polymerization of Escherichia coli FtsZ (9,10,14), but the character of these transformations is unclear. Assembly reactions are typically initiated by the addition of excess GTP to GDP-bound FtsZ, and it was proposed that the initial GDP release may cause the unimolecular lag in assembly kinetics (9,10). The rate of GDP release from FtsZ (38) is similar to that of the observed first-order reactions during assembly, but this alone may not be enough to explain cooperativity with a dimer nucleus. Nucleotide exchange will be favorable in the presence of excess GTP, whereas cooperativity requires an unfavorable activation step. Alternatively, the first-order reaction may be caused by the presence of weak GDP-FtsZ complexes or aggregates that form at high protein concentrations and need to disperse before polymerization can begin. When a nucleotide is added to FtsZ, light-scattering signals can drop slightly before rising again during assembly (14,39). This interpretation might be represented by the segregated Ln and Hn version of our model.

An attractive possibility is that the H and L conformations represent the straight and curved conformations favored by polymerized GTP-FtsZ and GDP-FtsZ, respectively. Like tubulin, the structure of FtsZ polymers depends on nucleotides. FtsZ forms relatively straight, stable protofilaments in the presence of GTP, and sharply curved, more labile protofilament rings in the presence of GDP (3). Applying our model, GTP- and GDP-bound FtsZ might access the same two conformations, but to different extents (i.e., KC(GDP) < KC(GTP) ≪ 1). As monomers, both forms of FtsZ would primarily exist in the low-affinity, curved conformation. For GDP-bound FtsZ, KC would be so small that changing conformations would not be favorable even in polymers, and the protein would assemble only in the low-affinity conformation. This would result in weak isodesmic polymerization, similar to what was observed for GDP-FtsZ (15). When unassembled, GTP-FtsZ would take on the same low-affinity conformation as GDP-FtsZ. However, the energetic barrier to conformational change would be lower, so that when GTP-FtsZ polymerized, subunits would change conformations, to be able to form high-affinity interfaces.

Other groups also proposed that the default conformation for FtsZ and tubulin may be the curved subunit structure, and that the main difference between the two nucleotide states may be the energy barrier to changing to the straight conformation (41,42). This idea was prompted by the observation that virtually all crystal structures from the tubulin family (tubulin, FtsZ, γ-tubulin, and the BtuB proteins) show related conformations and angled interfaces between associated subunits, regardless of the wide variety of nucleotides to which they are bound (43–47). For tubulin, straight protofilaments have only been observed in the presence of taxol (37), or when protofilaments are stabilized by the lateral interactions in microtubules and zinc sheets (48,49). The lateral interactions between protofilaments in microtubules are thought to stabilize the change to a straight conformation (42,43,49–51). In the model presented here, improved contacts at the longitudinal interface would also help stabilize the straight conformation (an idea also suggested by Lowe et al. (52)).

Further data confirm that subunits bound to GDP versus GTP can inhabit the same state. Under specific assembly conditions, subunits polymerize isodesmically and with similar low affinities, regardless of the nucleotide present. For Methanococcus jannaschii FtsZ, this occurs at low temperatures (53); for tubulin, it occurs in the absence of magnesium (41). Unlike tubulin, GTP-FtsZ can assemble fairly well in the absence of magnesium, but cooperativity is increased by an order of magnitude (9). This would be expected if the absence of magnesium destabilizes the straight conformation, but not enough to prevent conformational changes from occurring in polymers.

Data on polymer flexibility are also consistent with our model. The curvature of FtsZ protofilaments bound to GTP or its analog GDP- can vary significantly (16), whereas the small GDP-bound FtsZ rings have very defined diameters (54,55). This finding suggests that even in the middle of a polymer, GTP-FtsZ can take on different conformations more readily than can GDP-FtsZ, a situation that would occur if the conformational change were particularly unfavorable for GDP subunits. The opposite result was seen for microtubules: GDP microtubules are more flexible than those polymerized with GTP analogs (56–58). However, the situation in microtubules is different. The lateral interactions in a microtubule force GDP protofilaments to take on a straight conformation, and energetics should allow GDP-tubulin to escape from this state and bend more readily than protofilaments assembled with GTP analogs (49,50).

can vary significantly (16), whereas the small GDP-bound FtsZ rings have very defined diameters (54,55). This finding suggests that even in the middle of a polymer, GTP-FtsZ can take on different conformations more readily than can GDP-FtsZ, a situation that would occur if the conformational change were particularly unfavorable for GDP subunits. The opposite result was seen for microtubules: GDP microtubules are more flexible than those polymerized with GTP analogs (56–58). However, the situation in microtubules is different. The lateral interactions in a microtubule force GDP protofilaments to take on a straight conformation, and energetics should allow GDP-tubulin to escape from this state and bend more readily than protofilaments assembled with GTP analogs (49,50).

The above ideas contrast with the more common assumption that GTP-bound tubulin and FtsZ subunits exist in a straight (or straighter) conformation even when unassembled, and that this conformation differs from that of GDP-bound subunits (37,43,50,51,55). However, the two models are not mutually exclusive, because the barrier to changing conformations is likely to depend on both species-specific amino-acid sequences and assembly conditions (9,39). Because FtsZ assembles readily into protofilaments in the absence of lateral interactions, further studies on the effect of nucleotides on longitudinal bonds may be more straightforward in the bacterial system than for tubulin.

Determining the polymerization mechanism of FtsZ

We have described several mechanisms that can produce cooperativity in single-stranded polymers, but it remains to be determined which mechanism applies to FtsZ. Two pieces of data would confirm that the cooperativity of FtsZ is attributable to a conformational change. First, monomeric GTP-FtsZ should be in a different conformation than polymeric GTP-FtsZ. In addition, the relative stability of the two conformations in monomers should correlate with the degree of cooperativity. The degree of cooperativity for FtsZ can vary by more than two orders of magnitude (9,10). Those buffer conditions that decrease cooperativity should stabilize the active conformation in monomers, with the change in cooperativity proportional to the change in KC.

Whether conformational change precedes or follows assembly could be determined by the concentration dependence of elongation and nucleation reactions. For elongation, if the conformational change occurs before a subunit associates with a polymer (L + Hn ⇔ H + Hn ⇔ Hn+1; e1), then the elongation rate per filament will increase linearly with monomer concentration. If conformational changes are induced by polymer binding (L + Hn ⇔ LHn ⇔ Hn+1; e2), the elongation rate per filament will reach a maximum at very high protein concentrations. Determining the elongation rate per filament will require either single-filament observations or seeded reactions in which de novo polymerization can be ignored. Similarly, the concentration dependence of the lag phase of assembly may indicate which nucleation pathway FtsZ uses. If dimerization precedes the conformational changes (L + L ⇔ LL ⇔ LH ⇔ HH; n3), then at very high protein concentrations, the nucleation rate will be directly proportional to the total protein concentration zo, whereas at lower protein concentrations, it will be proportional to  In contrast, if both subunits change conformation before dimerization (L + L ⇔ H + H ⇔ HH; n1), the nucleation rate will be proportional to

In contrast, if both subunits change conformation before dimerization (L + L ⇔ H + H ⇔ HH; n1), the nucleation rate will be proportional to  regardless of total protein. (Note that even in the latter case, the apparent rate constant for nucleation will vary with protein concentrations as different steps in the nucleation pathway become rate-limiting.) The success of the experiments described above will depend on whether unimolecular reactions become rate-limiting at protein concentrations that are experimentally feasible.

regardless of total protein. (Note that even in the latter case, the apparent rate constant for nucleation will vary with protein concentrations as different steps in the nucleation pathway become rate-limiting.) The success of the experiments described above will depend on whether unimolecular reactions become rate-limiting at protein concentrations that are experimentally feasible.

Other approaches may also help define the assembly pathway of FtsZ. The kinetics of forming different assembly intermediates might be monitored if conformational changes could be detected independently from the association reactions. The value of specific equilibrium or rate constants might be learned from experiments in which only a subset of possible reactions is allowed to occur. For example, if GDP-bound subunits always occupy the low-affinity L conformation, then experiments with GDP-FtsZ should indicate the affinity and rate constants for the L + L ⇔ LL reaction. Other nucleotide analogs or mutant versions of FtsZ may similarly allow individual reactions to be isolated and studied. Finally, a high-resolution structure of FtsZ protofilaments may allow parameters to be estimated from free energy calculations and molecular dynamic simulations, as was done for actin (23).

Relevance for in vivo regulation of Z-ring formation

Unfavorable steps in polymerization allow a cell to regulate where, when, and how many cytoskeletal structures will form. Our knowledge of the structure and formation of filaments in the FtsZ ring in vivo is unfortunately still quite limited. There is evidence that FtsZ assembles in several steps, both in vitro and in vivo. In vitro, the assembly of linear protofilaments precedes the formation of higher-order, multistranded structures (14,16,39). Both circularization and lateral bundling of protofilaments can stabilize polymers and thus enhance cooperativity (15,19,53,59,60), but the relevance of these structures in vivo is unclear. Increased cross-linking might allow single-stranded polymers to coalesce into multistranded Z-rings (22) (Elizabeth Harry, University of Sydney, personal communication, 2008). Alternatively, some data suggest that the Z-ring may be composed of individual protofilaments (62). In this case, Z-ring formation could be controlled in part through the regulated nucleation of single-stranded protofilaments. Before Z-ring formation, rapidly changing helical FtsZ structures appear throughout the cell, and may be precursors to the ring at midcell (63,64). Although the exact makeup of these helices is unclear, initial data suggest that in wild-type cells, they may be connected into a single structure that spans the entire cell. In contrast, in mutant cells that are artificially long, two independent FtsZ structures were observed (64). Any difficulty in nucleating protofilaments would favor new polymerization, primarily at the ends of preexisting structures. Ensuring that all FtsZ polymers in the cell are part of one connected helix might help ensure that only a single Z-ring forms later in the cell cycle.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplementaary files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. P. Erickson for the many discussions that prompted this work, and for sharing his proofs and FtsZ polymerization data, A. Bartholemew and R. Ganetzky for help with preliminary modeling efforts, P. Bressloff, J. Correia, I. Gregoretti, D. Sept, and E. Wilmer for helpful discussion, and J. Correia, I. Gregoretti, and P. Levin for careful reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Mellon Foundation; P.J.T. acknowledges the support of National Science Foundation grant DMS-0720142; and L.R. acknowledges the support of a National Science Foundation Research Opportunity Award supplement for grant 0448186.

APPENDIX

In our model, four different types of elongation reaction can occur. To analyze all possible reactions simultaneously, we use a matrix method analogous to the transfer matrix method used in statistical mechanics to calculate the partition function of the one-dimensional Ising model (e.g., see Chandler (65)). Zimm and Bragg exploited a similar method for studying the distribution of helix and random coil phases within polypeptide chains (66). More recently, Bray et al. used variants of the Ising model to study allosteric changes in chemotaxis receptors (67), flagellar motors (68), and actin (36).

We first define the equilibrium constants, vectors, and matrices used in our analysis. We then show the derivations of the expressions for zo (total protein), p (subunits in polymer), and  (the maximum monomer concentration at equilibrium).

(the maximum monomer concentration at equilibrium).

Chemical reactions and equilibrium constants

In our model for allosteric single-stranded polymers, L and H subunit conformations are in equilibrium with each other, so that

|

(6) |

where KC is the equilibrium constant governing the conformational change in monomers. When KC < 1, monomers predominantly exist in the L conformation.

Four possible polymer elongation reactions can occur at each end of a polymer. We present elongation reactions at one arbitrarily chosen end of the polymer, which we call the plus end:

|

(7) |

KLL, KLH, KHL, and KHH are the equilibrium constants governing association between the different subunit combinations. X denotes a subunit whose conformation is unspecified, and Xn a chain of subunits of length n with arbitrary conformation. We only indicate the conformation of subunits at the plus end of the polymer; the conformation of all other polymer subunits is left unspecified. Thus LXn is the class of all polymers of length n + 1 in which the subunit at the plus end is an L, and LXn is the total concentration of all such polymers. LLXn is the class of polymers of length n + 2 in which both the terminal and penultimate subunit at the plus end are L subunits, LLXn is their concentration, and so on.

The chemical reactions shown in Eq. 7 represent only the addition of individual subunits to the ends of polymers; annealing and fragmentation reactions are not represented. Although such reactions can affect polymerization kinetics and polymer lengths, they do not affect the degree of polymerization at equilibrium (23,69), and it is the latter that is used to detect sharp critical concentrations.

The association constants shown in Eq. 7 are assumed to be independent of polymer length. This is a simplification; monomer-monomer interactions may be somewhat more favorable than the equivalent interactions between a monomer and a long polymer. More entropy may be lost when a monomer associates with a polymer than when it associates with another monomer (70,71). However, the length-dependent decrease in KA because of these entropy effects should be relatively small compared with the large difference in affinity between nucleation and elongation reactions. Length-dependent changes in KA were estimated to be approximately twofold to fivefold, both for theoretical linear protein polymers (71) and in experiments with GDP-FtsZ (15). In contrast, for FtsZ polymerized with GTP, the apparent KA for dimerization can be between two and four orders of magnitude smaller than the KA for elongation, depending on buffer conditions (9,10,39).

Vector representation of polymer concentrations

We use column vectors to represent the concentrations of polymer species that have the same length but different subunit conformations at their plus ends:

|

(8) |

where Zn is a 2 × 1 vector containing the concentrations of all polymers of length n, and zn, the total concentration of all chains of length n, is the sum of the two entries in Zn:

|

(9) |

As examples, we describe LXn−1 and HXn−1 for monomers, dimers, and trimers. For monomers, “X0” is the unique “empty chain” (containing no subunits), so that LX0 is just L, and HX0 is H. Thus we can write

|

(10) |

The total monomer concentration is

|

(11) |

For dimers, n = 2, so that we write

|

(12) |

There are four types of dimers to account for, LL, LH, HL, and HH. LX1 represents the class of the polymers that includes LL and LH, whereas HX1 represents the class of polymers that includes HL and HH. Similarly, there are eight types of trimers: LX2 represents the class that includes LLL, LLH, LHL, and LHH, whereas HX2 represents the class that includes HLL, HLH, HHL, and HH.

It is important to note that we do not determine the concentrations LXn−1 and HXn−1 by separately determining the concentration of each individual member of a class and then adding these concentrations together. Instead, we determine concentrations from the equilibrium between LXn−1 and HXn−1 polymers and the two classes of polymers one subunit shorter (LXn−2 and HXn−2), as described below.

Detecting critical concentrations

To determine whether our polymerization model can exhibit a critical concentration, we need to determine the concentrations of p (subunits in polymer) and z1 (monomers) as a function of zo (total protein concentration). The relationship between these values can be calculated from six parameters: the five equilibrium constants (KLL, KLH, KHL, KHH, and KC) and L, the concentration of low-affinity monomer. The approach is based on that published for isodesmic polymerization (11), except here we use matrix algebra to track four types of elongation reactions. The derivations described below are also summarized in Table 1.

We determine zo and p by summing series comprising the concentrations of subunits in chains of different lengths. For z1, we sum subunit concentrations in species of any length (n = 1 to ∞), whereas for p, we sum over lengths n = 2 to ∞. Each polymer concentration is determined from its equilibrium with species one subunit shorter. This procedure is strictly analogous to the sum used to obtain zo and p in the isodesmic case (Table 1), except that here we use the vectors Zn to represent the concentrations of chains of a given length.

To determine the concentration of polymers of length n from their equilibrium with polymers of length n − 1, we only need to consider monomer addition reactions at one arbitrarily chosen end of the polymer, which we have called the plus end. The total concentration of LXn polymers can be calculated from the two plus-end monomer addition reactions that can produce it from polymers one subunit shorter:

|

|

(13) |

The first reaction results in the formation of one subclass of LXn polymers, whose penultimate subunit is an L. The second reaction forms a second, nonoverlapping subclass of LXn polymers, whose penultimate subunit is instead an H. The total concentration of LXn polymers is the sum of these two subclasses. Applying Eqs. 9 and 13,

|

(14) |

Similarly, HXn can be calculated from the two plus-end monomer additions those reactions that can produce it from polymers one subunit shorter:

|

|

(15) |

Using Eqs. 6, 9, and 15, HXn can be calculated as:

|

(16) |

The same mathematical manipulations shown in Eqs. 13–16 are more conveniently carried out through matrix algebra:

|

(17) |

Therefore,

|

(18) |

where

|

(19) |

and T = KAL. The matrix KA contains the overall equilibrium constants for each of the four possible elongation reactions in which L monomers are reactants:

|

(20) |

The matrix T relates the concentration of polymers of length n to those of length n − 1. The scalar factor KA z1 functions similarly for isodesmic polymerization.

The concentration of polymers then becomes the sums of the entries in the vectors

|

(21) |

The concentration of all species of any length is then the sum of the entries of the infinite series:

|

(22) |

To find zo, the concentration of subunits in all species, it is necessary to multiply each polymer concentration by its length n. Thus zo is thus the sum of the components of the vector Zo, where

|

(23) |

Provided the eigenvalues of the 2 × 2 matrix T have absolute values of less than one, the series converges to give

|

(24) |

where I is the 2 × 2 identity matrix, and (I − T)−2 is the square of the matrix inverse of (I − T). This matrix is invertible except at a singular value of L, which in turn determines the limit of the monomer concentration at equilibrium (see below).

Similarly p, the concentration of subunits in all polymers (n ≥ 2), can be determined from the sum of the components of the vector P, where

|

(25) |

The maximum monomer concentration at equilibrium (z1∞)

The equilibrium monomer concentration approaches an upper limit  as the total protein concentration is increased. Thus

as the total protein concentration is increased. Thus  can be calculated by determining the monomer concentration (z1) as the total protein concentration (zo) approaches infinity. We first develop an expression for the maximum monomer concentration in the isodesmic case before considering

can be calculated by determining the monomer concentration (z1) as the total protein concentration (zo) approaches infinity. We first develop an expression for the maximum monomer concentration in the isodesmic case before considering  for our allosteric polymerization model.

for our allosteric polymerization model.

For isodesmic systems, p was defined in Table 1 as:

|

(26) |

Equation 26 converges to a finite solution only for KA z1 < 1; for KA z1 > 1, p = ∞. Thus, as p → ∞, KA z1 → 1. When KAz1 < 1, z1 < 1/KA. Thus for isodesmic polymerization, the maximum monomer concentration that can exist at equilibrium is equal to 1/KA, the dissociation constant for subunits from polymers.

The maximum monomer concentration for the allosteric polymerization model can be similarly analyzed. From Eq 24, we can write a formula to compute Zo as follows:

|

(27) |

Here, for the series to converge to a finite value, the eigenvalues of T must have absolute value of less than one, i.e., Zo is finite only if Tn−1 → 0 as n → ∞. Thus the maximum monomer concentration is the concentration of monomer for which the largest eigenvalue of T equals unity.

A formula for the maximum monomer concentration can now be derived from an expression for the eigenvalues of the matrix T. Recall that the matrix T has the following form:

|

(28) |

The largest eigenvalue of T, λ+, has the form:

|

(29) |

Substituting λ+ = 1 at the limit of z1, solving for L, and applying the relationship z1 = L(1 + KC) gives

|

(30) |

In the most highly cooperative polymerization systems, the expression in Eq. 30 reduces to  This occurs whenever KLL, KHL, KLH, and KC ≪ 1, and KHHKC ≫ KLL. This last constraint holds as long as it is more favorable for an L monomer to add to a preexisting Hn polymer and change conformations (L + Hn ⇔ Hn+1, Keq = KHHKC) than for two L monomers to dimerize (L + L ⇔ LL, Keq = KLL).

This occurs whenever KLL, KHL, KLH, and KC ≪ 1, and KHHKC ≫ KLL. This last constraint holds as long as it is more favorable for an L monomer to add to a preexisting Hn polymer and change conformations (L + Hn ⇔ Hn+1, Keq = KHHKC) than for two L monomers to dimerize (L + L ⇔ LL, Keq = KLL).

The degree of cooperativity of a polymerization system

The degree of cooperativity for a particular polymerization system is related to the nucleation parameter Kn/Ke (12,13,27). The nucleation parameter describes how favorable nucleation is relative to elongation, with smaller values indicating greater cooperativity. It is equivalent to the cooperativity parameter σ described elsewhere (11,20).

For an allosteric linear polymer with a dimer nucleus, Kn = K2, the effective association constant for dimers, which can be calculated from:

|

(31) |

Because  the nucleation parameter can be defined as

the nucleation parameter can be defined as

|

(32) |

In the most highly cooperative systems, Kn/Ke ≈ KC. This occurs when KC ≪ 1,  and the vast majority of dimers are in the HH conformation (when