Abstract

The mechanosensitive channel of large conductance, MscL, serves as a biological emergency release valve protecting bacteria from acute osmotic downshock and is to date the best characterized mechanosensitive channel. A well-recognized and supported model for Escherichia coli MscL gating proposes that the N-terminal 11 amino acids of this protein form a bundle of amphipathic helices in the closed state that functionally serves as a cytoplasmic second gate. However, a recently reexamined crystal structure of a closed state of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis MscL shows these helices running along the cytoplasmic surface of the membrane. Thus, it is unclear if one structural model is correct or if they both reflect valid closed states. Here, we have systematically reevaluated this region utilizing cysteine-scanning, in vivo functional characterization, in vivo SCAM, electrophysiological studies, and disulfide-trapping experiments. The disulfide-trapping pattern and functional studies do not support the helical bundle and second-gate hypothesis but correlate well with the proposed structure for M. tuberculosis MscL. We propose a functional model that is consistent with the collective data.

INTRODUCTION

Mechanosensation is essential for all forms of life, underlying many vital processes such as osmoregulation, gravitropism, the senses of hearing, balance, and touch as well as heart mechanoelectric feedback and blood pressure regulation (1–3). The transducers involved in these processes are often mechanosensitive channels. The molecular entities of most of the mechano-transducers in higher organisms have not yet been identified; in contrast, several mechanosensitive (MS) channels in bacteria have been cloned, and the structure of one representative for each of the two major families of these microbial channels has been resolved by x-ray crystallography (4,5).

Four MS channel activities have been characterized in Escherichia coli: the mechanosensitive channel of large conductance, MscL; smaller conductance, MscS; miniconductance, MscM; and one that is K+-regulated, MscK (6–9). Both MscL and MscS channels act as coordinated emergency valves allowing rapid solute release and homeostatic adjustment in the event of an osmotic downshock (acute change to a lower-osmolarity environment). Indeed, the double mutant ΔmscL/ΔmscS bacterial strain (but not the single mutants) shows more than a 10-fold increase in cell lyses on osmotic downshock compared with the parental strain (7).

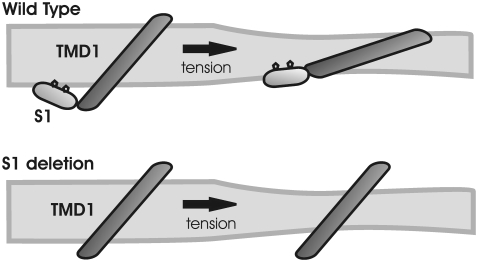

MscL from E. coli was the first cloned (10) and is to date the best understood MS channel from any species (11). It is a relatively small protein of 136 amino acids. The crystal structure of the ortholog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Tb-MscL) was solved to 3.5 Å resolution (5) and showed that the channel is a homopentamer in which each subunit contains two transmembrane domains (TMDs); both the N- and C-terminal regions are cytoplasmic (12). The most N-terminal region of the channel was not resolved in the first published structure for Tb-MscL (5). Subsequently, based on this structure and disulfide-trapping experiments, a detailed model for the gating of E. coli MscL (Eco-MscL) was predicted (13,14). Because the work was performed in the laboratories of Sukharev and Guy, this model has been referred to as the Sukharev-Guy or SG model; for simplicity we use the latter. The SG model proposed that the extreme N-terminal region (named S1) forms a bundled helix when the channel is in a closed state. This bundle serves as a second gate, remaining closed until most of the expansion of the channel has already occurred (Fig. 1) (13,14). However, in a newly revised version of the crystal structure for Tb-MscL, the S1 region was better resolved and modeled, thus showing S1 to have a helical structure running parallel to the cytoplasmic membrane (15) instead of forming the tight bundle proposed by the SG model (Fig. 1).

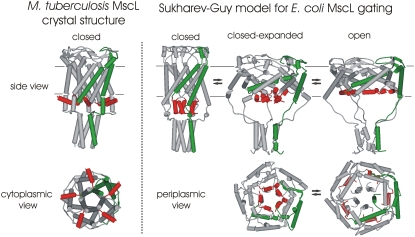

FIGURE 1.

Current models for MscL structure. Schematic representations of M. tuberculosis (left) and E. coli (right) MscL structural models are shown. The most N-terminal region of the channel (amino acids 2 to12) is shown in red, and a single subunit in green for clarity. On the left side of the panel, a model for a closed or nearly closed structure of M. tuberculosis MscL derived from the recently revised crystal structure (15) shows the homopentameric nature of the channel with the N-terminal region positioned at the cytoplasmic interface of the membrane. Side (upper left) and cytoplasmic (lower left) views are shown. The closed, closed-expanded, and open states from the proposed Sukharev-Guy (SG) model for E. coli MscL gating are shown in the three right-most panels (14); side (upper row) and periplasmic (lower row) views are shown. As shown in the middle of these panels (closed-expanded), the model predicts the N-terminal region (called S1) to play the role of a “second gate” that remains closed after most of the expansion of the channel has already occurred. The approximate membrane location is indicated by the parallel gray lines in the side view.

Here we present a systematic study of the S1 domain of E. coli MscL to determine its role in channel gating in light of these two existing models. We have scanned the entire region with cysteines and performed functional assays, an in vivo SCAM, electrophysiological characterization, and in vivo disulfide-trapping assays. Our results correlate well with the predicted structure of the S1 domain by the Tb-MscL crystal, counter predictions made by the SG model, and suggest an alternative role for gating.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and cell growth

The cysteine mutant library was generated using the Mega Primer method as described previously (16). Mutants were inserted within the pB10d expression construct, a modified pB10b plasmid (17–19), in which a methylation site, overlapping with the Xba consensus site, was changed (TCTAGAT to TCTAGAG). E. coli strain PB104 (ΔmscL∷Cm) (17) was used for the in vivo cysteine-trapping experiments and for electrophysiological analysis in which MscS was used as an internal control. The E. coli FRAG-1 derivative strain, MJF455 ΔmscL∷Cm, ΔmscS (7), was used for viability experiments after osmotic downshock and in vivo SCAM experiments. MTSET (2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl methanethiosulfonate bromide) and MTSES (2-sulfonatoethyl methanethiosulfonate sodium salt) were obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON, Canada). Cultures were routinely grown in Lennox Broth medium (LB) (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) or citrate phosphate medium (20) plus ampicillin (100 μg/ml) in a shaker-incubator at 37°C and rotated at 250 cycles/min. Expression was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Anatrace, Maumee, OH).

Western blot analysis

Western blots were performed as described (21). Briefly, colonies were grown to an early log phase (OD600 of 0.2–0.3) and diluted 1:1 in LB medium supplemented with 1 M NaCl and 2 mM IPTG. When grown to an OD600 of 0.3–0.4, the cultures were diluted 20-fold in prewarmed (37°C) distilled water (shock) or 500 mM NaCl LB medium (mock shock) and returned to the shaker-incubator for 20 min. Cells were pelleted in a microfuge and resuspended in nonreducing Laemmli buffer to a final volume normalized by the OD600 before treatment. Samples were resolved in a 4–20% gradient Tris-Cl polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The samples were electrotransferred to Immobilon polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 100 mV for 70 min. Western blot analysis was performed using primary antibodies against the MscL C-terminus as previously described (22) and the Immobilon Detection Reagents kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions. X-ray-sensitive film (Blue Bio Film, Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ) was exposed to the blotted membranes. Quantification was done by measuring the density of the bands using Scion Image software (NIH).

Electrophysiology

E. coli giant spheroplasts were generated and used in patch-clamp experiments as described previously (23). Excised, inside-out patches were examined at room temperature under symmetrical conditions using a buffer composed of 200 mM KCl, 90 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES pH 6 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Recordings were performed at −20 mV (positive pipette). Data were acquired at a sampling rate of 20 kHz with a 5-kHz filter using an AxoPatch 200B amplifier in conjunction with Axoscope software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). A piezoelectric pressure transducer (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) was used to monitor the pressure throughout the experiments. As previously described (19,22,23), MscS was used as an internal standard for determining MscL sensitivity. Measurements were performed using Clampfit9 from Pclamp9 (Axon Instruments).

In vivo functional assays

Colonies were grown overnight at 37°C in citrate phosphate medium plus 1 mM ampicillin. The overnight culture was diluted 1:20 in this defined medium, grown for l h, and then diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in the same medium supplemented with 0.5 M NaCl. After one or two divisions, expression was induced for 30 min with 1 mM IPTG. The induced cultures were diluted 1:20 into 1), citrate-phosphate medium containing 0.5 M NaCl (mock shock) or 2), water (osmotic downshock). The in vivo modified SCAM was performed in the presence of 1 mM MTSET or MTSES in the downshock and mock shock solutions. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 20 min, and then six consecutive 1:10 serial dilutions were made in medium containing either no salt (for the osmotic downshock conditions) or 0.5 M NaCl (for the mock-shock conditions). These diluted cultures were plated and grown overnight, and the colony-forming units were counted and averaged per experiment.

RESULTS

The S1 domain of MscL is critical for function but more tolerant of substitutions than the TMD1 pore domain

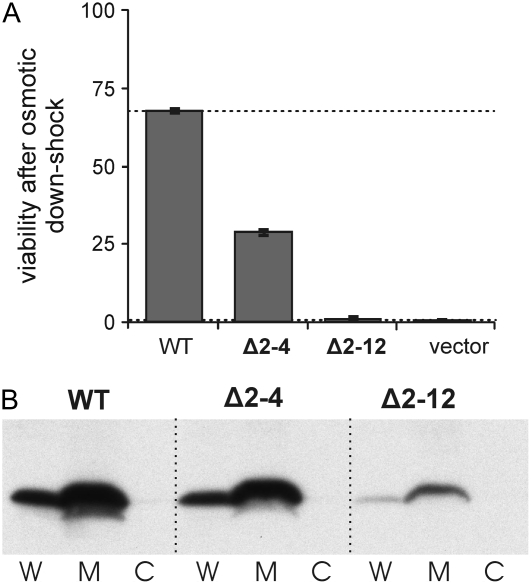

Previous studies (24,25) have demonstrated that deletions in the N-terminal region of MscL are poorly tolerated. Channels with a deletion of three amino acids (Δ2–4) are functional as assayed by patch clamp, but deletion of 11 amino acids (Δ2–12) led to nonfunctional channels (24). Here, we extend these results by assaying for functional channels in a more sensitive in vivo assay. For this functional characterization, we have used the E. coli strain MJF455 (Δmscs/Δmscl), which has a reduced viability after osmotic downshock and can be rescued by the expression in trans of wild-type MscL (18). The ability of the deletion mutants to rescue this osmotically sensitive strain compared with the wild-type channel shows not only that Δ2–12 is nonfunctional but that even Δ2–4 has compromised function (Fig. 2 A). The Δ2–12 mutant shows lower expression as determined by Western blot, which could conceivably lead to its apparent nonfunctional nature. However, even uninduced levels of expression, which amount to only two to six functional channels per cell (23), can save this osmotic-lysis phenotype and can even effect a gain-of-function phenotype for some mutants (20). Given these latter findings, and the fact that no one has yet observed any channel activity by patch clamp for Δ2–12 (24,25), the interpretation of the nonfunctional nature of this mutant is not likely to be simply lower expression. In any case, one cannot deny that the S1 domain is critical for function.

FIGURE 2.

Deletion of the most N-terminal region of E. coli MscL leads to a protein that is still expressed in the membrane but has a compromised function. (A) The ability of the deletion mutants Δ2–4 and Δ2–12, when expressed in trans, to rescue the MJF455 osmotic downshock-sensitive strain in vivo was compared with that of cells expressing wild-type or empty vector. Deletion mutant Δ2–4 partially rescued the osmotic-lyses phenotype, whereas Δ2–12 proved to be a nonfunctional channel. (B) Protein expression of wild type and both deletion mutants was analyzed by Western blot in whole cell (W), cytosol (C), and membrane fractions (M). Samples were obtained from PB104 cells expressing each of the mutants. Most of the protein was found in membrane fractions.

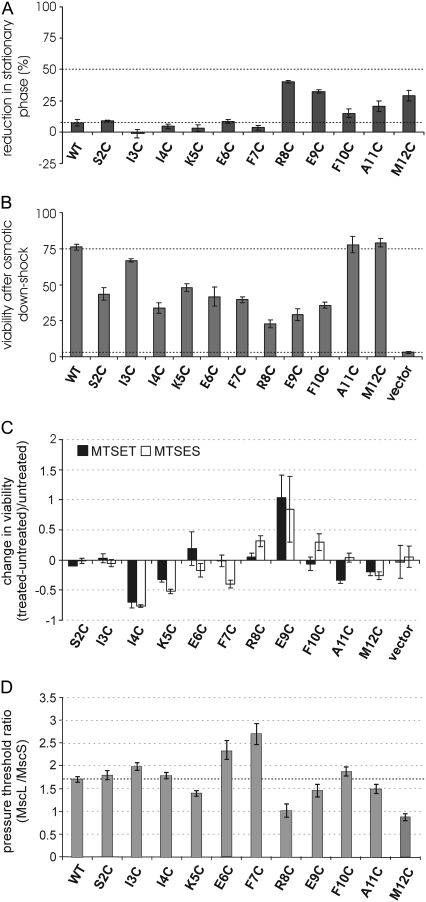

To determine whether a subdomain or single residue within this region is of critical importance, residues 2–12 of E. coli MscL were substituted with cysteines, and the physiological properties of each mutant determined by in vivo and electrophysiological functional assays. A decrease in stationary phase OD600 has previously been shown to be a sensitive assay for channels that appear to gate inappropriately in vivo (16). As shown in Fig. 3 A, of all S1 cysteine-substituted channels, only cells expressing mutants R8C, E9C, A11C, and M12C showed a small but statistically significant decrease in their stationary phase OD600 when compared with wild type (lower dashed line). However, no mutant caused a reduction greater than the 50% (upper dashed line) that was a cutoff value used to designate a significant functional deficit in a previous study of TMD1; cells expressing eight different cysteine substitutions within TMD1 exceeded this 50% reduction is growth (16). In addition, no obvious differences in the growth rates were observed for any of the S1 mutants (data not shown). These data suggest that none of the mutated channels had as high a propensity for gating inappropriately in vivo as has been previously observed for the pore-forming TMD1 region (16).

FIGURE 3.

In vivo and patch-clamp characterization of S1 cysteine mutants demonstrates that substitutions in the region are well tolerated. (A) Little or no reduction in the stationary phase values was observed for mutants when compared with wild-type MscL (lower dashed line). The dashed line designates the 50% cutoff value used in previous studies to designate a significant functional difference; none of the mutants studied here achieved this value. (B) The ability of the S1 cysteine-substituted mutants to rescue an osmotic-lysis phenotype is shown as a percentage of survival. All of the mutated channels are functional when compared with negative controls (vector only, lower dashed line); however, many of the cysteine substitutions in the S1 region effected only a partial suppression of the osmotic-lysis phenotype when compared with the wild type (upper dashed line). (C) An in vivo SCAM study was performed for the S1 cysteine mutants. The change in their ability to rescue an osmotic-lysis phenotype in the presence of MTSET (black bars) and MTSES (white bars) reagents is shown in the graph as the weighted fold difference ((treated − untreated)/untreated). (D) Single-channel activities of each of the S1 mutants were analyzed by patch clamp in giant spheroplasts. A Δmscl bacterial strain (PB104) with an intact MscS was used. The pressure thresholds for the activation of each of the MscL S1 mutants was compared with that of the internal control MscS and expressed as a ratio.

An in vivo functional assay similar to that shown in Fig. 2 A was performed on the S1 cysteine-substituted mutants to assess their ability to rescue the osmotically fragile MJF455 strain. As shown in Fig. 3 B, all of the S1 mutants rescued the lyses phenotype when compared with cells carrying an empty vector (negative control, lower dashed line); however, most mutants showed only a “partial” rescue of the lyses phenotype when compared with the expression in trans of wild-type MscL (upper dashed line), suggesting that the mutated MscL channels required more membrane tension than wild type for gating. It is important to note that a growth phenotype can complicate the interpretation of these data (16); thus, much of the decreased rescue observed for mutants R8C and E9C (Fig. 3 B) could be because the cells are stressed from expressing these mutated proteins (as indicated in Fig. 3 A). In sum, although none of the cysteine mutations in the S1 domain leads to nonfunctional MscL channels in vivo, the integrity of the region is required for entirely normal channel function. Here again, the finding that none of the channels are nonfunctional contrasts similar cysteine-scanning studies of the TMD1, where five mutants have been found to be nonfunctional (16).

Because cysteine is a reactive residue, we can posttranslationally modify the cysteine-substituted amino acids using sulfhydryl reagents. Previous studies have demonstrated that when the MscL channel is gated in vivo, even many cytoplasmic residues are susceptible to modification by the positively charged sulfhydryl reagent MTSET (2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl methanethiosulfonate) as evidenced by a decreased viability; this has been coined as an in vivo substituted cysteine accessibility method (in vivo SCAM) (20,26). The viability of osmotically challenged cells (leading to gated channels) treated with MTSET, or the negatively charged MTSES (2-sulfonatoethyl methanethiosulfonate), is shown in Fig. 3 C, where the heights of the bars reflect the difference in survival compared with the untreated cells. A significant effect of the binding of MTS reagents on channel function was observed only for mutants I4C, K5C, and E9C; no dependence of charge was observed. Assuming the residues are accessible, these data would be consistent with those of the cysteine scan, which shows that no single residue appears critical. Only 27% of the S1 residues are sensitive to these sulfhydryl reagents, which contrasts the finding that 40% (12 of 30) of the residues within and close to the TMD1 domain have been found to be extremely sensitive to MTSET (20,26). Hence, S1 appears to be much more resilient to residue substitution or modification than are the adjacent domains.

Finally, single-channel activities were characterized by patch-clamp experiments in bacterial membranes by utilizing giant spheroplasts. The activation pressure threshold of each mutant was compared with that of MscS; the resulting ratios are shown in Fig. 3 D. All the channels were functional, with most of the mutants showing near-normal activation thresholds when compared with wild-type MscL, confirming the results of the in vivo functional experiments. Substitution mutants E6C and F7C, followed by I3 and F10, showed the most severe phenotypes, requiring the highest tensions to gate. This pattern (residues 3, 6/7, and 10) is consistent with an α-helix, which is at the basis of both models. Overall, both the in vivo and channel phenotypes observed here are subtle when compared with substitutions in the both TMDs from previous studies (16,19,21).

The disulfide bridging pattern and the effect of oxidizing agents on channel function of the cysteine mutants of S1 domain support the Tb-MscL crystal structure

The ability of each of the substituted residues to interact with their counterparts from neighboring subunits and form dimers was analyzed in vivo. These analyses were performed subsequent to osmotic downshock and mock shock conditions (in which MscL had been gated or not gated, respectively). Samples derived from mock or osmotic downshocked bacterial cells expressing each of the S1 cysteine-substituted channels were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot. Representative examples for each of the mutants are shown in Fig. 4 A, in which the bands corresponding to the monomer and dimers are indicated by an arrow. The bar graph in Fig. 4 B shows the average percentage of the total protein that appears as a dimer. Note that there is no significant disulfide bridging observed in this region unless the cells are osmotically shocked. Given this result, it seems unlikely that in vivo disulfide bridging, leading to locked-closed channels, is the reason many of the channels showed only partial rescue of the osmotically sensitive strain, as discussed above and shown in Fig. 3 B. Although the disulfide bridging observed on gating could be a result of structural movements occurring in the gating process, perhaps a more likely explanation is that this is caused by a cellular change in redox: the normally reductive cytoplasmic environment probably becomes more oxidative on channel gating because of the cytoplasmic loss of glutathione and other reducing agents such as thioredoxin (27). Results of identical experiments performed with the adjacent S1-to-TMD1 linker region (21) are also shown in Fig. 4 B for a better interpretation of the data. Note that fewer dimers are observed in the S1 domain than in this adjacent linker region.

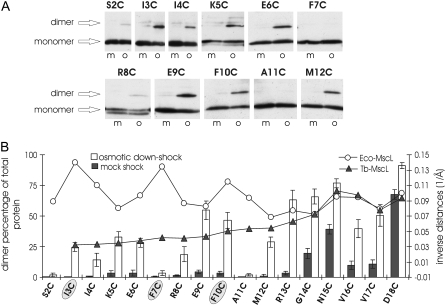

FIGURE 4.

In vivo disulfide-trapping experiments show weak intersubunit interactions in S1 cysteine mutants relative to the adjoining S1-TMD1 linker region. (A) Representative Western blots for each of the cysteine-substituted mutants are shown. Samples derived from bacterial cells diluted in a medium of the same osmolarity (m for mock shock) or in water (o for osmotic downshock) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and MscL detected by Western blot. (B) The bar graph (left y axis) shows the average and standard error of the percentage total protein that is in the form of dimers for mock shock (dark bars) or osmotically challenged (white bars) samples derived from at least five experiments similar to the examples shown in A. The line graph reflects the inverse distances between α-carbons of neighboring subunits for each residue, as predicted by the model of M. tuberculosis (Tb-MscL, solid triangles) or by the SG model for the closed E. coli MscL (Eco-MscL, open circles). Note that smaller values represent longer predicted distances. Results for the adjacent region (S1-TMD1 linker region, residues R13–D18) derived from similar experiments using an identical protocol (21) are also shown to better determine which model best fits the data. Circled residues are those predicted by the SG model to be in close proximity in the closed and closed-expanded conformations and were shown to yield strong disulfide bridging in membrane preparations (13).

Overall, the distances between the α-carbon of the residues of neighboring subunits should be inversely proportional to the observed amount of disulfide bridging. In an attempt to find a correlation between the disulfide bridging pattern and the predicted distances by the two existing models, the inverse distances (1/Å) were plotted in the same figure as line graphs (open circles for SG Eco-MscL model and solid triangles for Tb-MscL crystal structure). Residues predicted to be in the closest proximity by the SG model and previously shown to disulfide bridge (I3C, F7C, and F10C (13,14)) are shaded in the figure; these residues did not show the strongest interactions in the region, and no correlation was found between the disulfide bridging pattern observed and the predicted distances by the SG model. In contrast, there appeared to be a clear correlation between the distances predicted by the Tb-MscL crystal structure (15) and the amount of dimerization observed.

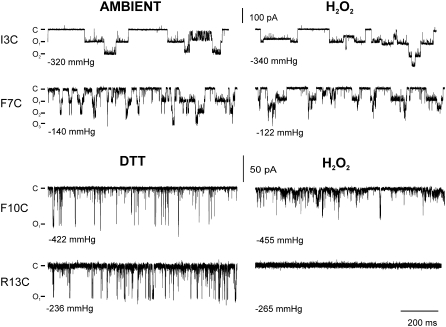

In the original publication, the SG model was supported not only by the ability to disulfide bridge residues I3, F7, and F10 but also by the observation that the functional activities of these channels were apparently sensitive to redox conditions. Given the discrepancy between the disulfide bridging pattern in Fig. 3 B and the predictions of the SG model, we decided to systematically reevaluate these redox data (Fig. 5); R13C, which has previously been demonstrated to be extremely sensitive to disulfide bridging and to achieve a locked-closed conformation with this covalent linkage (16), was used as a control. As expected for the low efficiency of disulfide bridging observed for mutants I3C and F7C, their activities did not show any evident changes between ambient conditions and the presence of an oxidant (H2O2) (Fig. 4) or a reducing agent (DTT) (not shown). In contrast, F10C and R13C, which showed a higher percentage of dimer formation, were influenced by redox. A decrease in the amplitude of single-channel events was observed under oxidizing (and even ambient) conditions for F10C, with full openings observed more consistently in the presence of the reducing agent DTT. However, this mutant was not locked closed under these oxidizing conditions, and no changes in sensitivity were observed among the different redox environments used. As expected from a previous study (16), the most drastic effects of oxidation on channel activity were observed for R13C. Together, these data are not consistent with previous findings or the SG model (13,14). On the other hand, the data are what one would expect if the S1 domain remained along the membrane surface: residues closer to the pore would be more likely to be trapped by disulfide bridging and effect a locked-closed channel phenotype.

FIGURE 5.

Single-channel activity of cysteine mutants under different oxidizing conditions. Representative traces of single-channel activity for mutants I3C, F7C, F10C, and R13C shown under different redox conditions. Recordings were made at −20 mV, and by convention openings are shown as downward. No differences were observed in channel activity for I3C and F7C mutants measured before (ambient, left) and after treatment with the oxidant H2O2 (right). Unlike I3C and F7C, F10C and R13C showed variable activity under ambient conditions and were influenced by DTT. Therefore, these membrane patches were treated with DTT for 5 to 35 min (left) before oxidative treatment (right). Note that a decrease in the amplitude of F10C was observed in presence of H2O2, whereas R13C activity was abolished under identical oxidizing conditions. All H2O2-treated traces reflect activities 5 to 15 min after the addition of oxidant.

DISCUSSION

Both the conservation of the region and functional studies underline the importance of the S1 domain and in part led to the speculation that this domain plays the role of a second gate. This region of E. coli MscL is greatly conserved among other bacterial species. In particular, phenylalanines 7 and 10 are conserved in 97% and 100%, respectively, in an alignment of 232 species (Supplementary Material, Data S1) and are substituted only by leucines. The S1 domain motif of XXYYFYYFXX, with X being hydrophobic and Y polar amino acids, is conserved in 79%, and the outliers had only subtle variations. Interestingly, the XXYYFYYFXX motif is conserved even in species that have as many as 30 additional amino acids at the N-terminal, further emphasizing its importance in channel function. In addition, electrophysiological studies found that even small deletions in this region (3, 8, or 11 amino acids) or substitution of 9 amino acids of the S1 domain with a random sequence lead to channels with either a decreased sensitivity or total loss of activity (24,25). Here we further characterized in vivo two deletion mutants and find that deletion of 11 residues is sufficient to lead to a nonfunctional, but membrane-associated, protein, and the deletion of as few as three residues measurably compromises function (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, this critically important region of the protein was not resolved in the first Tb-MscL crystallographic structure (5), and one could only speculate on its role in channel gating. In studies of the energetics of the channel, it was noted that a large amount of energy was required to effect MscL gating. Because this energy translated into a change in area (ΔA), Sukharev et al. (28) interpreted these data as supporting a model in which the channel expands within the plane of the membrane before ion permeation; the critical yet unresolved N-terminal region of the protein seemed a logical location of a second gate that would allow for this expansion (Fig. 1). The authors performed targeted disulfide-trapping experiments, which seemed to confirm their supposition (13,14).

Although appealing, the SG model did not easily account for some experimental data, thus leading to the proposal of other models with TMD1 serving as the only gate (see Blount et al. (11) for a review). Mutations in TMD1 that were found to increase channel sensitivity also decreased the open dwell time, thus leading to the hypothesis that not only is TMD1 the principal gate but that it is the transient exposure of hydrophobic regions in this domain to the pore lumen that is the primary energy barrier to achieving an open structure; mutation to more hydrophilic residues decreases this energy barrier, leading not only to more sensitive channels but to activities that more easily transition between closed and open states (1,16,29). If S1 truly formed a second gate, one might expect that mutations here would also lead to channels that misfunction. But random mutagenesis combined with in vivo assays showed that there is a great tolerance for mutations in this region (19,30,31). Here we have used a more systematic and sensitive approach and find that substitutions at many sites within this domain do indeed lead to phenotypes, albeit subtle, when compared with those of TMD1 (16), thus supporting the functional importance of the region. Although the subtle nature of the phenotypes is not necessarily inconsistent with the SG model, the locations of some of the phenotype-effecting mutations (e.g., R8C and E9C) do not give strong support for it either. Structurally the S1 domain is predicted by the SG model to be a helical bundle; however, a recent reevaluation of the Tb-MscL crystal structure allowed for the resolution of the S1 domain (15), and the new structure showed the domain along the cytoplasmic membrane interface. Here again, this is not strong evidence against the SG model because, given that there are most likely several closed states of the channel, the SG closed structure could be achieved only under some conditions (e.g., on initial tension in the membrane). Although none of these observations by itself strongly disputes the SG model, the explanations required to accommodate the findings sometimes seem strained; we therefore believed that it was appropriate to directly reevaluate the data underlying the SG model.

The SG model predicted specific protein-protein interactions within the proposed S1 bundle, which were tested in the original publication using targeted disulfide trapping of I3C, F7C, and F10C in isolated membranes (13,14). We have repeated these experiments but have assessed the state of the protein in vivo (cells directly lysed and solubilized with SDS-PAGE loading buffer), thus avoiding any manipulations before Western blot analysis. In addition, we have compared residues within the entire region and even an adjacent region that we characterized using an identical approach (Fig. 4) (21). We found that F7C did not form measurable disulfide bridges, and although residues I3, and F10 do, they were not as reactive as neighboring residues; instead, it appeared that the hydrophilic face of the amphipathic helix was the most reactive (K5 > I3, E6 > F7, and E9 > F10). In addition, the pattern of disulfide bridging across the region is not consistent with that predicted by the SG model but reflects what one might expect for the current Tb-MscL structure: residues more distal to the pore had, in general, a smaller probability of disulfide bridging. Another strong argument supporting the SG model in the original article was the finding that F7C and F10C activity was not observed in patch clamp except when treated with reducing reagents (13). In contrast to this previous report, here we were able to demonstrate channel activities in both cases independent of reducing agents; although F10C activity is clearly modified by redox, H2O2 never completely locked the channel closed, and we saw no effect of redox on F7C. Similarly, the original report for the SG model stated that the I3C channel partially closed when treated with an oxidizing reagent; again, our data do not agree. The most likely reason for this discrepancy is the difference in the experimental conditions used. The original report treated the patch with I2 for 30 min, whereas here we use the less-aggressive oxidant, H2O2, for 5 to 15 min, which appears to be sufficient (see the positive control R13C). From the data presented in Fig. 5, it again becomes apparent that disulfide bridging that affects channel function is greatest when near TMD1 (R13C) and decreases distally. Again, these data support the model in which the S1 domain lies along the cytoplasmic membrane.

Collectively, our data support the newly reevaluated Tb-MscL crystal structure, placing S1 along the cytoplasmic surface of the membrane (15). But what could be the function of such a structure? In determining the function of the S1 domain, it may be important to note that all current models for the gating of MscL predict a significant tilting of the TMD1 membrane on opening (13,14,32). We propose that the S1 domain helps to define this tilt by maintaining its interaction with the membrane by serving as an anchor (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the two most conserved residues within the S1 domain, F7 and F10, represented as diamonds in Fig. 6, are aromatic and hydrophobic; thus, they have a high affinity for the lipid environment. This could also explain why in a few instances these residues are not conserved; the substitution is always the hydrophobic residue leucine. The functional role of G14 as a hinge between TMD1 and S1 domains would still be critical for channel function, as previously shown (13). This hypothesis is consistent with all of the data obtained thus far from several studies, including the apparent inconsistency between deletion and missense mutations. It may be of interest to note that a similar structure is found in the bacterial inward-rectifying K+ channel KirBac, in which a cytoplasmic α-helix running parallel to the membrane (slide-helix) (33,34) was found to interact directly with the phospholipid headgroups to regulate channel gating (35). In another study, the aromatic nature of a residue at the cytoplasmic end of the putative pore-forming TMD6 domain of the MS yeast TRPY1 channel has been shown to be important in gating and has been referred to as a “gate anchor” (36); the region could potentially form an amphipathic α-helix, although the structure of this channel has not yet been determined. Finally, a crystallographic structure of MscS, another bacterial MS channel from an independent channel family, also appears to contain an α-helix along the cytoplasmic/membrane surface just adjacent to the pore (4,15). Similar to MscL, current models of MscS gating predict a tilting of the pore domain (37), and a glycine is also present between these two domains (Gly-113), probably serving as a hinge (4,15). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that this analogous domain within MscS, and perhaps other channels, may serve a similar function as the S1 domain in MscL.

FIGURE 6.

Model for the role of the S1 domain in MscL gating. The scheme shows the S1 and TMD1 domains of a single subunit of MscL before (left) and after (right) applying tension to the membrane. The upper graph shows a wild-type MscL where the S1 domain is intact. The two most conserved residues in this region, F7 and F10, are shown as pentagons along this structure, stabilizing the interactions with the membrane. The region serves as an anchor for TMD1 to the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, facilitating and guiding the tilting of TMD1 on membrane-tension-effected bilayer thinning and channel opening. The lower graph shows an S1 deletion mutant of MscL. The lack of this anchor region impairs the proper tilting of the TMD1 domains needed for channel gating, so the channel remains closed. Tilting angles shown for the TMD1 domains in the closed and open states were derived from the crystal structure for Tb-MscL and the open state of E. coli MscL from the SG model, respectively.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by Grant I-1420 of the Welch Foundation, Grant FA9550-05-1-0073 of the Air Force Office of Scientific Review, Grant 0655012Y of the American Heart Association—Texas Affiliate, and Grant GM61028 from the National Institutes of Health.

Editor: Richard W. Aldrich.

References

- 1.Hamill, O. P., and B. Martinac. 2001. Molecular basis of mechanotransduction in living cells. Physiol. Rev. 81:685–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niu, W., and F. Sachs. 2003. Dynamic properties of strech-activated K+ channels in adult rat atrial myocytes. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 82:121–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sukharev, S., and D. P. Corey. 2004. Mechanosensitive channels: multiplicity of families and gating paradigms. Sci. STKE. 2004:re4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bass, R. B., P. Strop, M. Barclay, and D. C. Rees. 2002. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli MscS, a voltage-modulated and mechanosensitive channel. Science. 298:1582–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, G., R. H. Spencer, A. T. Lee, M. T. Barclay, and D. C. Rees. 1998. Structure of the MscL homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A gated mechanosensitive ion channel. Science. 282:2220–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berrier, C., M. Besnard, B. Ajouz, A. Coulombe, and A. Ghazi. 1996. Multiple mechanosensitive ion channels from Escherichia coli, activated at different thresholds of applied pressure. J. Membr. Biol. 151:175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levina, N., S. Totemeyer, N. R. Stokes, P. Louis, M. A. Jones, and I. R. Booth. 1999. Protection of Escherichia coli cells against extreme turgor by activation of MscS and MscL mechanosensitive channels: identification of genes required for MscS activity. EMBO J. 18:1730–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, Y., P. C. Moe, S. Chandrasekaran, I. R. Booth, and P. Blount. 2002. Ionic regulation of MscK, a mechanosensitive channel from Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 21:5323–5330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLaggan, D., M. A. Jones, G. Gouesbet, N. Levina, S. Lindey, W. Epstein, and I. R. Booth. 2002. Analysis of the kefA2 mutation suggests that KefA is a cation-specific channel involved in osmotic adaptation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 43:521–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sukharev, S. I., P. Blount, B. Martinac, F. R. Blattner, and C. Kung. 1994. A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E. coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature. 368:265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blount, P., I. Iscla, P. C. Moe, and Y. Li. 2007. MscL: The bacterial mechanosensitive channel of large conductance. In Current Topics in Membranes. O. P. Hamill, editor. Academic Press, New York. 201–233.

- 12.Blount, P., S. I. Sukharev, P. C. Moe, M. J. Schroeder, H. R. Guy, and C. Kung. 1996. Membrane topology and multimeric structure of a mechanosensitive channel protein of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 15:4798–4805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukharev, S., M. Betanzos, C. Chiang, and H. Guy. 2001. The gating mechanism of the large mechanosensitive channel MscL. Nature. 409:720–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sukharev, S., S. Durell, and H. Guy. 2001. Structural models of the MscL gating mechanism. Biophys. J. 81:917–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinbacher, S., R. Bass, P. Strop, and D. C. Rees. 2007. Structures of the prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels MscL and MscS. In Current Topics in Membranes. O. P. Hamill, editor. Academic Press, New York. 1–24.

- 16.Levin, G., and P. Blount. 2004. Cysteine scanning of MscL transmembrane domains reveals residues critical for mechanosensitive channel gating. Biophys. J. 86:2862–2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blount, P., S. I. Sukharev, P. C. Moe, M. J. Schroeder, H. R. Guy, and C. Kung. 1996. a. Membrane topology and multimeric structure of a mechanosensitive channel protein of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 15:4798–4805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moe, P. C., G. Levin, and P. Blount. 2000. Correlating a protein structure with function of a bacterial mechanosensitive channel. J. Biol. Chem. 275:31121–31127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ou, X., P. Blount, R. J. Hoffman, and C. Kung. 1998. One face of a transmembrane helix is crucial in mechanosensitive channel gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:11471–11475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartlett, J. L., G. Levin, and P. Blount. 2004. An in vivo assay identifies changes in residue accessibility on mechanosensitive channel gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:10161–10165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iscla, I., G. Levin, R. Wray, and P. Blount. 2007. Disulfide trapping the mechanosensitive channel MscL into a gating-transition state. Biophys. J. 92:1224–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blount, P., S. I. Sukharev, M. J. Schroeder, S. K. Nagle, and C. Kung. 1996. b. Single residue substitutions that change the gating properties of a mechanosensitive channel in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:11652–11657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blount, P., S. I. Sukharev, P. C. Moe, B. Martinac, and C. Kung. 1999. Mechanosensitive channels of bacteria. In Methods in Enzymology. P. M. Conn, editor. Academic Press, New York. 458–482. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Blount, P., S. I. Sukharev, M. J. Schroeder, S. K. Nagle, and C. Kung. 1996. Single residue substitutions that change the gating properties of a mechanosensitive channel in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:11652–11657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Häse, C. C., A. C. Ledain, and B. Martinac. 1997. Molecular dissection of the large mechanosensitive ion channel (Mscl) of E. coli—mutants with altered channel gating and pressure sensitivity. J. Membr. Biol. 157:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batiza, A. F., M. M. Kuo, K. Yoshimura, and C. Kung. 2002. Gating the bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscL invivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:5643–5648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ajouz, B., C. Berrier, A. Garrigues, M. Besnard, and A. Ghazi. 1998. Release of thioredoxin via the mechanosensitive channel MscL during osmotic downshock of Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:26670–26674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sukharev, S. I., W. J. Sigurdson, C. Kung, and F. Sachs. 1999. Energetic and spatial parameters for gating of the bacterial large conductance mechanosensitive channel, MscL. J. Gen. Physiol. 113:525–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blount, P., and P. Moe. 1999. Bacterial mechanosensitive channels: integrating physiology, structure and function. Trends Microbiol. 7:420–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blount, P., S. I. Sukharev, P. C. Moe, S. K. Nagle, and C. Kung. 1996. Towards an understanding of the structural and functional properties of MscL, a mechanosensitive channel in bacteria. Biol. Cell. 87:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maurer, J. A., and D. A. Dougherty. 2003. Generation and evaluation of a large mutational library from the Escherichia coli mechanosensitive channel of large conductance, MscL—implications for channel gating and evolutionary design. J. Biol. Chem. 278:21076–21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perozo, E., D. M. Cortes, P. Sompornpisut, A. Kloda, and B. Martinac. 2002. Open channel structure of MscL and the gating mechanism of mechanosensitive channels. Nature. 418:942–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuo, A., C. Domene, L. N. Johnson, D. A. Doyle, and C. Venien-Bryan. 2005. Two different conformational states of the KirBac3.1 potassium channel revealed by electron crystallography. Structure. 13:1463–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuo, A., J. M. Gulbis, J. F. Antcliff, T. Rahman, E. D. Lowe, J. Zimmer, J. Cuthbertson, F. M. Ashcroft, T. Ezaki, and D. A. Doyle. 2003. Crystal structure of the potassium channel KirBac1.1 in the closed state. Science. 300:1922–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enkvetchakul, D., I. Jeliazkova, J. Bhattacharyya, and C. G. Nichols. 2007. Control of inward rectifier K channel activity by lipid tethering of cytoplasmic domains. J. Gen. Physiol. 130:329–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou, X., Z. Su, A. Anishkin, W. J. Haynes, E. M. Friske, S. H. Loukin, C. Kung, and Y. Saimi. 2007. Yeast screens show aromatic residues at the end of the sixth helix anchor transient receptor potential channel gate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:15555–15559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards, M. D., Y. Li, S. Kim, S. Miller, W. Bartlett, S. Black, S. Dennison, I. Iscla, P. Blount, J. U. Bowie, and I. R. Booth. 2005. Pivotal role of the glycine-rich TM3 helix in gating the MscS mechanosensitive channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.