Summary

Human cystic echinococcosis, caused by infection with the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus, and alveolar echinococcosis, caused by the larval form of E. multilocularis, are known to be important public health problems in western China. Echinococcus shiquicus is a new species of Echinococcus recently described in wildlife hosts from the eastern Tibetan plateau and its infectivity and/or pathogenicity in humans remain unknown. In the current study, parasite tissues from various organs were collected post-operatively from 68 echinococcosis patients from Sichuan and Qinghai provinces in eastern China. The tissues were examined by histopathology and genotyped using DNA sequencing and PCR-RFLP. Histopathologically, 38 human isolates were confirmed as E. granulosus and 30 as E. multilocularis. Mitochondrial cob gene sequencing and PCR-RFLP with rrnL as the target gene confirmed 33 of 53 of the isolates to have the G1 genotype of sheep/dog strain of E. granulosus as the only source of infection, while the remaining 20 isolates were identified as E. multilocularis. No infections were found to be caused by E. shiquicus. Additionally, 5 of 20 alveolar echinococcosis patients were confirmed to have intracranial metastases from primary hepatic alveolar echinococcosis lesions. All these cases originated from four provinces or autonomous regions but most were distributed in Sichuan and Qinghai provinces, where high prevalence rates of human alveolar echinococcosis and cystic echinococcosis were previously documented.

Keywords: Alveolar echinococcosis, Cystic echinococcosis, Echinococcus shiquicus, Histopathology, PCR, Tibet

1. Introduction

Human echinococcosis refers to infection with the larval stages of any of the currently recognized four main species of Echinococcus, namely, E. granulosus, E. multilocularis, E. oligarthrus and E. vogeli (Kumaratilake and Thompson, 1982; Rausch and Bernstein, 1972). The latter two species occur only in Central and South America and may cause polycystic echinococcosis in humans (D’Alessandro, 1997), while E. granulosus and E. multilocularis are the causative agents of cystic echinococcosis (CE) and alveolar echinococcosis (AE), respectively. Echinococcus granulosus has the greatest geographic distribution worldwide (Schantz et al., 1995), whereas E. multilocularis is a rare parasitic disease that is restricted to transmission in the northern hemisphere, with distribution from Alaska, across Canada and north central USA, through northern Europe and Eurasia to Japan (Craig, 2003). In China, both cystic and alveolar echinococcosis are highly endemic over large areas of the northwestern provinces and autonomous regions, mainly distributed in Qinghai, Sichuan, Xinjiang, Gansu and Ningxia (Chai, 1995; Craig et al., 1992; Li et al., 2005; Schantz et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2006). Recently, a new species of Echinococcus, E. shiquicus, was described from the Tibetan plateau. The Tibetan fox (Vulpes ferrilata) has been confirmed as the definitive host and the plateau pika (Ochotona curzoniae) as the intermediate host but its pathogenicity in humans, if any, remains unknown (Li et al., 2005; Xiao et al., 2005).

Substantial genetic diversity of E. granulosus has led to the description of 10 genotypes (G1-10) (Bowles et al., 1992, 1995; Bowles and McManus, 1993; Lavikainen et al., 2003; Nakao et al., 2007; Scott et al., 1997), and the G1 genotype has been proved to be cosmopolitan in its distribution and the major cause of human infection (McManus, 2002; Thompson and McManus, 2001). In China, previous genotypic analysis indicated the pathogenicity of the G6 genotype (dog/camel) in humans in Xinjiang autonomous region (Bart et al., 2006). However, the situation in other endemic regions of China is poorly understood. Furthermore, molecular confirmation of human AE due to E. multilocularis is rare in China.

2. Materials and methods

From 2004 to 2007, parasite tissues were collected post-operatively from patients clinically diagnosed with echinococcosis. Most cases were treated at the Aba Army Hospital (located in Maerkang, the capital of Aba Tibetan autonomous prefecture of Sichuan province), and hospitals in Chengdu (the capital of Sichuan province). General information about these cases including name, age, gender and region of origin was recorded. If possible, image data including ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were reviewed. Part of the parasite biopsy tissue from each patient was stored in 99% ethanol for later DNA analysis, while the remaining part was fixed in 5% formalin and subjected to histopathological analysis. Formalin-fixed parasite tissue was embedded in paraffin wax and 3–5 μm sections were prepared and subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Genomic DNA from parasite tissues was extracted using a DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Extracted DNA was examined by PCR-RFLP as described previously (Xiao et al., 2006). Briefly, the primer pair, Ech-LSU/F (5′-GGTTTATTTGCCTTTTGCATCATGC-3′) and Ech-LSU/R (5′-ATCACGTCAAACCATTCAAACAAGC-3′) was used to amplify a ~570bp DNA fragment of a mitochondrial gene (rrnL, large subunit of rRNA), within which species-specific SspI restriction site existed. A PCR cocktail contained 1 μl of template, 200 μmol/l of each dNTP, 0.2 μmol/l of each primer, 0.5 Unit of the exTaq DNA polymerase Hot Start (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) and the manufacturer-supplied buffer in 25 μl of a mixture reaction. Thermal reactions of PCR were conducted for 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s. Afterwards, the PCR product was cleaved with SspI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) for 2 h at 37 °C. Electrophoresis was then performed on the restriction fragments in 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide, which led to specific restriction patterns for differentiation of E. granulosus, E. multilocularis and E. shiquicus. For further discrimination of the genotypes G1 and G6 of E. granulosus, cleavage of the PCR product with BglII (Takara) was necessary to obtain characteristic restriction maps. PCR was conducted for amplification of a 549 bp DNA fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome b (cob) gene as reported previously (Nakao et al., 2003; Xiao et al., 2005). The primer sequences used were 5′-GTCAGATGTCTTATTGGGCTGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCTGGGTGACACCCACCTAAATA-3′ (reverse). PCR was performed in a final volume of 50 μl containing 1 μl template, 200 μmol/l of each dNTP, 0.2 μmol/l of each primer, 1 Unit of Ex-Taq polymerase and the manufacturer-supplied buffer. The PCR protocol was composed of 35 cycles of denaturation (94 °C for 30 s), annealing (55 °C for 30 s) and extension (72 °C for 60 s). The amplicons were purified using the NucleoSpin ExTract Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) and directly sequenced using the Thermo Sequenase dye terminator cycle sequencing premix kit (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK) and an automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems Model 377, Foster City, CA, USA).

3. Results

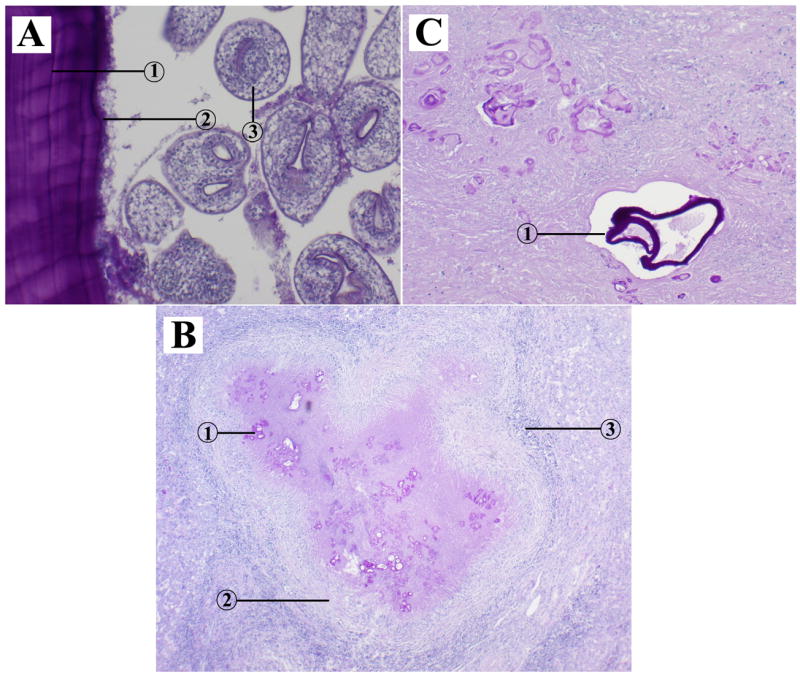

A total of 70 parasite tissue isolates from 68 operated echinococcosis cases were obtained and fixed in 5% formalin, of which 62 were removed from livers, five from brains, one from the abdominal cavity, one from a vertebra and one from the pelvic cavity. In one patient, parasite tissue was obtained not only from the liver but also from the brain. In another patient, parasite samples were obtained from both the brain and bone (vertebra). In 38 cases, the structure of the lesions was characterized by a thick laminated layer and a germinal layer and brood capsules or protoscolices could be observed (Figure 1A), which were identified as E. granulosus, the cause of CE infection. Large numbers of vesicles of different sizes and shapes with a thin laminated layer were observed in 32 lesions from an additional 30 echinococcosis cases but protoscolices could not be confirmed. In these cases distinct hyperplasia of fibro-connective tissue and cellular infiltration of eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells were observed (Figure 1B and Figure 1C), which resulted in a diagnostic confirmation of AE (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Histopathological characteristics of of cystic echinococcosis and alveolar echinococcosis lesions in humans. (A) cystic echinococcal lesion in the liver (HE stain ×100); 1: laminated layer; 2: germinal layer; 3: protoscolex. (B) alveolar echinococcal lesion in the liver (HE stain ×40); 1: vesicles; 2: hyperplasia of fibro-connective tissue; 3: cellular infiltration. (C) alveolar echinococcal lesion in the brain (HE stain ×100); 1: vesicles.

Table 1.

Species confirmation of human echinococcosis by histopathological and molecular methods

| Location | No. of samples

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histopathology | PCR-RFLP and DNA Sequencing | |||

| AE | CE | AE | CE | |

| Liver | 26 | 36 | 16 | 31 |

| Brain | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Vertebra | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Abdominal cavity | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pelvic cavity | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 32 | 38 | 21 | 33 |

AE: Alveolar echinococcosis (Echinococcus multilocularis); CE: cystic echinococcosis (E. granulosus).

Fifty-four parasite tissue samples from 53 of 68 patients were available after storage in 99% ethanol, of which 47 were excised from liver, four from brain, one from the abdominal cavity, one from the pelvic cavity and one from the vertebra. All the 54 isolates were examined by PCR-RFLP, identifying 33 as the sheep/dog strain of E. granulosus (G1 genotype) and 21 as E. multilocularis (Table 1). Furthermore, the amplicons of isolates from 54 parasite tissues were sequenced to identify the species; the results from the cob sequences were identical with PCR-RFLP typing data (Table 1).

In five of 68 patients, parasite lesions were removed from the brain and were subsequently identified to be E. multilocularis by histopathology and/or genotyping. Review of image data from CT or MRI of these cases indicated pathognomonic AE lesions in the liver and confirmation of intracranial metastases of AE was made in these five cases. In addition, one AE patient had metastasis to the vertebrae as well as the brain.

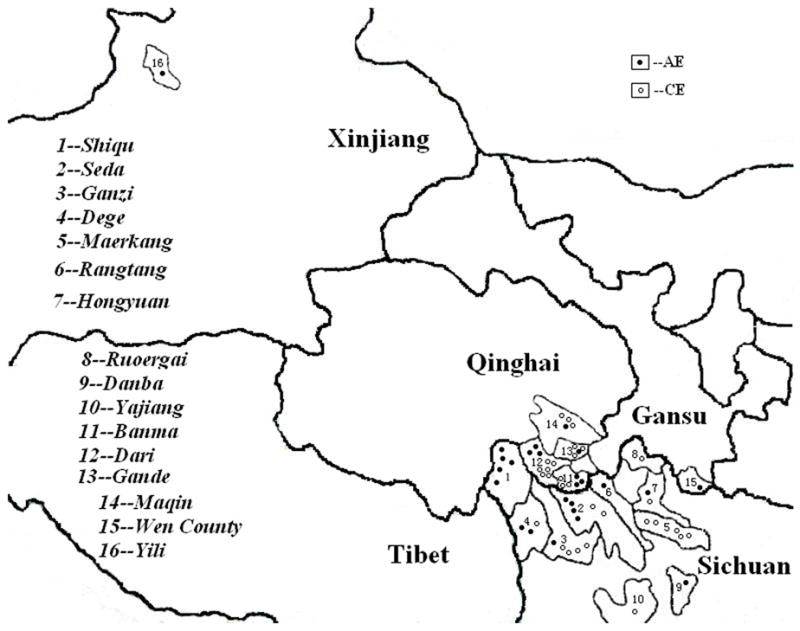

Among the 68 human echinococcosis cases confirmed in our study, 63 were Tibetans and five were Han Chinese, 41 were female and 24 were male (no information available for three cases). The youngest CE case was 7 years old and the youngest AE patient was 14 years old. The average age (n = 59, no information for nine cases) of echinococcosis cases was 33.0 years (35.1 years (n = 31) for CE cases and 30.6 years (n = 28) for AE cases). Information about case origin was obtained from 56 of 68 patient records, which showed a wide distribution in eight counties of Sichuan province including Seda, Yajiang, Ganzi, Shiqu, Maerkang, Dege, Hongyuan, Rangtang, Danba and Ruoergai. In addition, cases also originated from four counties of Qinghai Province, i.e. Banma, Gande, Dari and Maqin, and from Wen County, Gansu Province and Yili Prefecture of Xinjiang autonomous region (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of 56 confirmed human cases of echinococcosis in northwestern China. Locations of cases are not exact within counties.

4. Discussion

In the current study, histopathology and/or genotyping using PCR-RFLP and DNA sequencing were used to confirm the diagnosis of echinococcosis in 68 human cases from hospitals in Sichuan province, China. Of these, 38 cases were confirmed as CE due to E. granulosus and the remaining 30 as AE due to E. multilocularis. No infections with E. shiquicus were detected. Genetic analysis of cystic lesions in 33 of 38 cases revealed that the G1 genotype (sheep/dog strain) was the only source of E. granulosus infection. In addition, five patients with primary hepatic AE were shown also to have distant intracranial metastases; one of these had additional vertebral metastases. The majority of these human infections were ethnic Tibetans, distributed in four adjacent regions of China, i.e. Sichuan, Qinghai, Gansu and Xinjiang. Most of the cases originated from northwest Sichuan and southeast Qinghai, where both human CE and AE has previously been documented to be an important public health problem (Craig, 2006; Li et al., 2005; Schantz et al., 2003).

The sheep/dog strain of E. granulosus (G1) has been proved to be cosmopolitan in its distribution, as the predominant source of infection in both animals and humans (McManus, 2002; Thompson and McManus, 2001). The presence of E. granulosus genotypes G2, G5, G6 and G9 in humans was confirmed in Argentina and Poland (Guarnera et al., 2004; Rosenzvit et al., 1999; Scott et al., 1997), while in China previous studies from different areas revealed that human infections were caused by the G1 genotype (McManus et al., 1994; Yang et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 1998). However, in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region the camel strain (G6) was also recently shown to infect humans (Bart et al., 2006). In our study, the G1 genotype was identified to be the only source of infection in all the 33 CE cases examined, with distribution in Sichuan and Qinghai provinces, where yaks, sheep and goats are used as the primary livestock by semi-nomadic herdsman. In that area of China, high prevalence of the larval stage of E. granulosus has been observed in domestic livestock and the infection source has been confirmed so far to be only the G1 genotype (Heath et al., 2005; Xiao et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2005). Therefore, in these areas humans probably acquire infection mostly through the sheep (yak)/dog cycle. In China, the first human cases of AE were reported from western regions in the 1960s but most hospital records still remain fragmented. From the mid-1990s active mass screening surveys using portable ultrasound led to the discovery of the highest documented prevalence rates of human AE (Craig et al., 1992; Li et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2006). However, the application of molecular genetic analysis to human AE isolates in China is rare. In this study, histopathological examination of 32 parasitic lesions resected from 30 patients clinically diagnosed with AE supported the diagnosis of infection with E. multilocularis. In addition, 21 of the 32 lesions were further analyzed by both PCR-RFLP and DNA sequencing, which unequivocally identified the species as E. multilocularis. Metastases of AE in the brain were also demonstrated to have occurred in five patients, one of which had additional metastasis to the vertebrae. These cases indicate the serious public health problem of human AE in Tibetan communities of China and the need for early detection and treatment.

In addition to E. granulosus and E. multilocularis, a new species, E. shiquicus, was described recently on the eastern Tibetan plateau in Shiqu County, Sichuan, with the Tibetan fox as definitive host and the plateau pika as intermediate host (Xiao et al., 2005). For the first time we have used genotypic analysis to test parasite tissues from humans for the presence of DNA from E. shiquicus. In total, 54 isolates from individual parasite lesions were checked, however no infections were found to be caused by E. shiquicus. Dogs have been shown to play a crucial role in the transmission of E. granulosus and E. multilocularis on the Tibetan plateau (Li et al., 2005). However, no infections with E. shiquicus have been found in dogs (Budke et al., 2005). The existence of large populations of dogs as companion animals facilitates the transmission of E. granulosus and E. multilocularis to humans. By contrast, small populations of foxes and limited contact with foxes may decrease opportunities for humans to be exposed to E. shiquicus. Echinococcus shiquicus has recently been demonstrated to be distributed in Shiqu and Seda counties of Sichuan province and Banma county of Qinghai province (T. Li et al., unpublished data), where human infections only with E. multilocularis and E. granulosus were identified in the present study. Although the three Echinococcus species sympatrically exist in these areas, E. shiquicus may have few chances to infect humans due to the unique relationship between the life cycles of Tibetan foxes and pikas or it may have poor infectivity in humans. This remains to be resolved in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Desheng Liu from the 363 Hospital in Chengdu as well as Dr Shaopeng Ma from the Aba Army Hospital for their contribution in organizing parasite materials from humans.

Funding: The study was supported by grant no. RO1 TW001565 from the Fogarty International Center, USA and supported in part by the international collaboration research projects sponsored by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (14256001, 17256002) and JSPS-Asia/Africa Science Platform Fund (2006–2008) to AI.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: TL, AI, PSC and JQ designed the study protocol and drafted the manuscript; TL, PSC, AI and PG performed the analysis and interpretation of data; TL, MN, NX and XW conducted genetic analysis of all specimens; RZ did surgery; KN and MN did histopathology for morphological and molecular analysis; TL, CX and JQ collected tissue samples in the endemic areas. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. TL is guarantor of the paper.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bart JM, Abdukader M, Zhang YL, Lin RY, Wang YH, Nakao M, Ito A, Craig PS, Piarroux R, Vuitton DA, Wen H. Genotyping of human cystic echinococcosis in Xinjiang, PR China. Parasitology. 2006;133:571–579. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006000734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J, McManus DP. NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene sequences compared for species and strains of the genus Echinococcus. Int J Parasitol. 1993;23:969–972. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(93)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J, Blair D, McManus DP. Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54:165–174. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90109-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J, Blair D, McManus DP. A molecular phylogeny of the genus Echinococcus. Parasitology. 1995;110:317–328. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budke CM, Campos-Ponce M, Wang Q, Torgerson PR. A canine purgation study and risk factor analysis for echinococcosis in a high endemic region of the Tibetan plateau. Vet Parasitol. 2005;127:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai JJ. Epidemiological studies on cystic echinococcosis in China - a review. Biomed Environ Sci. 1995;8:122–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig PS. Echinococcus multilocularis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:437–444. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig PS the Echinococcosis Working Group in China. Epidemiology of human alveolar echinococcosis in China. Parasitol Int. 2006;55(Suppl 1):S221–S225. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig PS, Deshan L, MacPherson CN, Dazhong S, Reynolds D, Barnish G, Gottstein B, Zhirong W. A large focus of alveolar echinococcosis in central China. Lancet. 1992;340:826–831. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92693-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro A. Polycystic echinococcosis in tropical America: Echinococcus vogeli and E. oligarthrus. Acta Trop. 1997;67:43–65. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnera E, Parra A, Kamenetzky L, García G, Gutìérrez A. Cystic echinococcosis in Argentina: evolution of metacestode and clinical expression in various Echinococcus granulosus strains. Acta Trop. 2004;92:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath DD, Zhang LH, McManus DP. Short report: Inadequacy of yaks as hosts for the sheep dog strain of Echinococcus granulosus or for Echinococcus multilocularis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:289–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaratilake LM, Thompson RC. A review of the taxonomy and speciation of the genus Echinococcus Rudolphi 1801. Z Parasitenkd. 1982;68:121–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00935054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavikainen A, Lehtinen MJ, Meri T, Hirvela-Koski V, Meri S. Molecular genetic characterization of the Fennoscandian cervid strain, a new genotypic group (G10) of Echinococcus granulosus. Parasitology. 2003;127:207–215. doi: 10.1017/s0031182003003780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Qiu J, Yang W, Craig PS, Chen X, Xiao N, Ito A, Giraudoux P, Mamuti W, Yu W, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis in Tibetan populations, western Sichuan Province, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;12:1866–1873. doi: 10.3201/eid1112.050079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus DP. The molecular epidemiology of Echinococcus granulosus and cystic hydatid disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96(Suppl 1):S151–S157. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus DP, Ding Z, Bowles J. A molecular genetic survey indicates the presence of a single, homogenous strain of Echinococcus granulosus in north-western China. Acta Trop. 1994;56:7–14. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M, Sako Y, Ito A. Isolation of polymorphic microsatellite loci from the tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis. Infect Genet Evol. 2003;3:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s1567-1348(03)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M, McManus DP, Schantz PM, Craig PS, Ito A. A molecular phylogeny of the genus Echinococcus inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Parasitology. 2007;134:713–722. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch RL, Bernstein JJ. Echinococcus vogeli sp n (Cestoda: Taeniidae) from the bush dog, Speothos venaticus (Lund) Z Prakt Anasth Wiederbeleb Intensivther. 1972;23:25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzvit MC, Zhang LH, Kamenetzky L, Canova SG, Guarnera EA, McManus DP. Genetic variation and epidemiology of Echinococcus granulosus in Argentina. Parasitology. 1999;118:523–530. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099004035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schantz PM, Chai JJ, Craig PS, Eckert J, Jenkins DJ, Macpherson CNL, Thakur A. Epidemiology and control of hydatid disease. In: Thompson RCA, Lymbery AJ, editors. Echinococcus and hydatid disease. CAB International; Wallingford, Oxford: 1995. pp. 233–331. [Google Scholar]

- Schantz PM, Wang H, Qiu J, Liu FJ, Saito E, Emshoff A, Ito A, Roberts JM, Delker C. Echinococcosis on the Tibetan plateau: prevalence and risk factors for cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in Tibetan populations in Qinghai Province, China. Parasitology. 2003;127(Suppl):S109–S120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, Stefaniak J, Pawlowski ZS, McManus DP. Molecular genetic analysis of human cystic hydatid cases from Poland: identification of a new genotypic group (G9) of Echinococcus granulosus. Parasitology. 1997;114:37–43. doi: 10.1017/s0031182096008062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RCA, McManus DP. Aetiology: parasites and life-cycles. In: Eckert J, Gemmell M, Meslin F-X, Pawlowski Z, editors. WHO/OIE manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals: a public health problem of global concern. World Organisation for Animal Health; Paris: 2001. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao N, Qiu J, Nakao M, Nakaya K, Yamasaki H, Sako Y, Mamuti W, Schantz PM, Craig PS, Ito A. Short report: Identification of Echinococcus species from a yak in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau region of China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:445–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao N, Qiu J, Nakao M, Li T, Yang W, Chen X, Schantz PM, Craig PS, Ito A. Echinococcus shiquicus n sp., a taeniid cestode from Tibetan fox and plateau pika in China. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao N, Nakao M, Qiu J, Budke CM, Giraudoux P, Craig PS, Ito A. Short Report: Dual infection of animal hosts with different species of Echinococcus in the eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau region of China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:292–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YR, Rosenzvit MC, Zhang LH, Zhang JZ, McManus DP. Molecular study of Echinococcus in west-central China. Parasitology. 2005;131:547–555. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005007973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YR, Williams GM, Craig PS, Sun T, Yang SK, Cheng L, Vuitton DA, Giraudoux P, Li X, Hu S, Liu X, Pan X, McManus DP. Hospital and community surveys reveal the severe public health problem and socio-economic impact of human echinococcosis in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, China. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:880–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LH, Chai JJ, Jiao W, Osman Y, McManus DP. Mitochondrial genomic markers confirm the presence of the camel strain (G6 genotype) of Echinococcus granulosus in north-western China. Parasitology. 1998;116:29–33. doi: 10.1017/s0031182097001881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]