Abstract

The purpose of this descriptive, correlational study was to examine the prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers during the first 6 months after giving birth, as well as to investigate whether ethnicity has an impact on the occurrence of such symptoms. Twenty-two women completed the Perinatal Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Questionnaire at a community health center. Data analysis included descriptive statistics, correlations, and independent sample t-tests. Higher total Perinatal PTSD Questionnaire scores were related to higher numbers of both perinatal and postpartum complications. In addition, Hispanic women were found to be less likely to experience avoidance than Caucasian women. Although more research is needed, findings from this study demonstrate a preliminary relationship between the two variables, ethnicity and avoidance.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, PTSD, ethnicity, birth trauma, childbirth

INTRODUCTION

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was first listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980 after symptoms of posttraumatic stress were seen as a result of war experiences (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1980). According to the DSM-III, a diagnosis of PTSD requires the occurrence of an event considered beyond the range of usual human experience. Symptoms involve a triad of responses, including active avoidance of reminders of the event, hyperarousal manifested by general edginess or irritability, and intrusive experiences consisting of nightmares or images that occur as if the person relives the triggering event in real time or persistently reexperiences the traumatic event (APA, 1980). In order for a diagnosis of PTSD to be made, these symptoms must last for at least 1 month following the event and must also cause impairment in day-to-day life (APA, 1980).

More recently, the DSM-IV provides an expanded view of what can be considered an extreme traumatic stressor. The revised definition includes “direct personal experience of an event that involves actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others” (APA, 1994, p. 424). According to this definition, although not specifically named, childbirth can qualify as a traumatic event leading to the development of PTSD or posttraumatic stress symptoms (Beck, 2004a).

The recognition that PTSD or posttraumatic stress symptoms can occur after childbirth has led to the understanding that a triggering event does not necessarily need to be beyond the range of usual human experiences (Slade, 2006). Rather, it need only be outside the individual's typical experience. Because laboring and giving birth is an unfamiliar process to most women, happening only once or twice during a woman's lifetime, it can be considered an event outside of one's typical experiences.

In the past, it has been recognized that women who have experienced a difficult or traumatic childbirth can go on to develop some type of psychological problems, yet it has only recently become accepted that these women can actually develop PTSD (Bailham & Joseph, 2003). According to Bailham and Joseph, based upon a review of the literature, PTSD following a traumatic childbirth experience manifests itself in one or more of three ways, including sexual avoidance, fear of childbirth, and mother-infant attachment and parenting problems.

The reported prevalence of diagnosed PTSD after childbirth ranges from 1.5% (Ayers & Pickering, 2001) to 5.6% (Creedy, Shochet, & Horsfall, 2000). However, significantly more women present with symptoms of posttraumatic stress following a traumatic birth experience, but have not been diagnosed with PTSD (Alder, Stadlmayr, Tschudin, & Bitzer, 2006). The reported prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms after childbirth ranges from 1.5% to 32.1%, depending on the methods and instruments employed (Alder et al., 2006; Maggioni, Margola, & Filippi, 2006). In one particular study, only 1.25% of women showed clinically significant levels of PTSD symptoms, while 28.75% reported clinically significant symptoms for at least one subscale (Cigoli, Gilli, & Saita, 2006).

The reported prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms after childbirth ranges from 1.5% to 32.1%, depending on the methods and instruments employed.

Among the studies discussed above, the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms Scale was used by Ayers and Pickering (2001), who studied women at 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum, and by Creedy et al. (2000), who studied women at 4–6 weeks postpartum. The Postttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire was used by Maggioni et al. (2006) and by Cigoli et al. (2006) to study women at 3–6 months postpartum. All studies were longitudinal studies.

Although many aspects regarding the development of PTSD following childbirth have been researched, in reviewing the literature, no research on the possible impact of ethnicity on the occurrence of posttraumatic stress symptoms has been found. As a result, this study sought to attempt to identify any correlation between ethnicity and the occurrence of posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers after childbirth. The purpose of this study was therefore to examine the prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers during the first 6 months after giving birth and to investigate whether ethnicity has an impact on the occurrence of such symptoms.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The theoretical framework for this study was Sichel and Driscoll's (1999) Earthquake Model, developed for the purpose of conceptualizing women's mental health and the treatment of women. This model explains why a woman's unique brain and hormone chemistry can result in her vulnerability to certain mood disorders, including postpartum depression and PTSD, at critical times in her life, such as after childbirth. Sichel and Driscoll suggest that a woman's genetic makeup, hormonal and reproductive history, and life experiences all combine to predict her risk of an “earthquake.” This “earthquake” occurs when her brain cannot stabilize after an event, such as childbirth, whether it is normal or traumatic, and mood problems, such as PTSD, subsequently erupt (Sichel & Driscoll).

Sichel and Driscoll (1999) use the analogy of an earthquake and its tremors to depict the impact of a woman's stress and reproductive hormones on her brain biochemistry, seen as the fault line underneath the earth's surface. Stressful events disrupt the delicate balance of the woman's brain chemistry, first causing small tremors, then a complete emotional earthquake, such as PTSD. Sichel and Driscoll further acknowledge that the postpartum period in a woman's life is an especially high-risk period, during which the emergence of a mood disorder is a very possible occurrence and, so, should be monitored and evaluated for.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Previous quantitative and qualitative studies have identified symptoms of PTSD in mothers after the birth of full-term and premature infants hospitalized in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (Callahan & Hynan, 2002). In studies using the Perinatal Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire, researchers also found that mothers of high-risk infants (premature or term infants hospitalized in a NICU) reported more PTSD symptoms than mothers of full-term, healthy infants (Callahan & Hynan, 2002; DeMier, Hynan, Harris, & Manniello, 1996). All studies using the Perinatal Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire have found that the severity of complications in the infant was the main predictor of PTSD symptoms in the mothers of high-risk infants (Callahan & Hynan, 2002). More recently, several studies have shown the existence of PTSD after both complicated and uncomplicated births of healthy infants (Maggioni et al., 2006).

In Beck's (2004a) descriptive, phenomenologic study investigating birth trauma, the researcher found that births that mothers perceived as traumatic were often viewed as routine by clinicians. Several factors have been found to influence a woman's perception of childbirth, including expectations for labor and birth, pain, sense of control, and social support, which have been divided into prepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum variables (Maggioni et al., 2006).

Prepartum variables include the woman's expectations for her birth, which develop during the pregnancy. Differences between the woman's expectations and the actual experience of her birth have been shown to affect the woman's feelings, producing adverse emotional outcomes including disappointment, guilt, depression, and trauma (Maggioni et al., 2006). These adverse emotions can then develop into PTSD or posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Differences between the woman's expectations and the actual experience of her birth have been shown to affect the woman's feelings, producing adverse emotional outcomes including disappointment, guilt, depression, and trauma.

Like prepartum variables, intrapartum variables have also been associated with dissatisfaction and have been reported as an obstetric predictor for the development of PTSD. Intrapartum variables include emergency cesarean births, induction of labor, prolonged labor, and instrumental vaginal births (Maggioni et al., 2006). In addition, an episiotomy has been reported as an obstetric predictor for PTSD (Alder et al., 2006).

Not all women experiencing what would be considered a more traumatic birth, such as an emergency cesarean birth, develop PTSD. The majority of women who develop PTSD have had a normal vaginal birth, demonstrating the importance of the subjective experience of labor (Alder et al., 2006). The subjective experience of birth trauma is described by Beck (2004a), who concluded that birth trauma lies in the eye of the beholder.

Through an analysis of the stories of 40 women participating in a study and recruited through purposive sampling via the Internet and postal mail, Beck (2004a) revealed the essential components of a traumatic birth as viewed through the mother's eyes. Four themes emerged from the birth trauma stories. The essential components of a traumatic birth were the mother's perceived lack of care and communication from the labor and delivery staff, unsafe care, and an overshadowing of the trauma based upon the birth outcome (Beck, 2004a).

The provision of unsafe care has also been reported as a predictor of PTSD in other studies. Creedy et al. (2000) found that women who perceived their care as unsafe or inadequate and experienced a high level of obstetric intervention were more likely to develop symptoms of PTSD than those who experienced only one of these scenarios. Even if a woman does not develop full-blown PTSD, she can still go on to develop some of the symptoms of posttraumatic stress. In fact, most agree that more women present with only some of the symptoms (Alder et al., 2006).

In their recent study, Maggioni et al. (2006) investigated the prevalence of each of the three PTSD subscale symptoms (intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal). Overall, they found that 32.1% (n = 27) had one or two positive subscales, and that only 2.4% of the study participants had complete PTSD. Using the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire with a sample size of 93 women who were 3–6 months postpartum, Czarnocka and Slade (2000) found that 15.5% (n = 13) had a positive intrusion subscale, 25.0% (n = 21) had a positive arousal subscale, and 3.6% (n = 3) had a positive avoidance subscale.

In a qualitative, phenomenological study, Beck (2004b) investigated the experience of PTSD attributable to childbirth. Stories received via the Internet from 38 mothers recruited through purposive sampling were analyzed, and five themes were developed. The themes that emerged illustrated the symptoms of PTSD attributable to childbirth, including reexperiencing the event, numbing of the self, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with their birth trauma (Beck, 2004b).

More important, Beck's (2004b) study demonstrated the devastating effects of PTSD due to the childbirth, based on the finding that mothers with PTSD struggle to survive day-to-day due to their constant battle with terrifying nightmares and flashbacks, anger, anxiety, depression, and isolation from the normal world of motherhood. Not only do these symptoms affect the mother, but they can also affect the child, because the developing relationship between the mother and her child is hindered, leading to attachment problems (Beck, 2004b).

PTSD following childbirth has been studied by many different researchers, and many different elements have been investigated. However, as previously stated, no previous research studies on the possible impact of ethnicity on PTSD symptoms have been found. For this reason, this study sought to answer the questions of whether ethnicity has any impact on the prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms after childbirth and, if so, what kind of impact it has.

METHODS

Research Design

This study used a descriptive, correlational design to investigate the prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers during the first 6 months after birth to determine which symptoms are more prevalent and to determine which demographic or obstetrical characteristics are significant predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms. The study also explored whether ethnicity has an impact on the amount or type of symptoms experienced.

It had previously been determined, based on a power analysis using Power and Precision (Borenstein, Rothstein, & Cohen, 2001), that a sample size of 34 was needed for the present study. Using a t-test with an alpha coefficient of 0.05, a sample size of 34 women was projected to result in a power of 0.80 to detect significant differences between groups. However, due to time limitations, it was not possible to recruit 34 women for this study.

Instrument

Mothers participating in the study were asked to complete the Perinatal PTSD Questionnaire (PPQ). The PPQ, developed by Michael T. Hynan, PhD, in order to quantify the symptoms of PTSD related to childbirth, is a dichotomously scored questionnaire compoed of 14 “yes” or “no” questions (Quinnell & Hynan, 1999). The PPQ is exclusively designed to examine the prevalence of the three components of PTSD: unwanted intrusions, avoidance, and increased arousal. To do so, the first three questions describe symptoms of unwanted intrusions, such as bad dreams or upsetting memories; the next six describe symptoms of avoidance, such as avoiding thinking about childbirth or avoiding doing things that remind mothers of their experience; and the last five questions describe symptoms of increased arousal, such as being more irritable or having more difficulty concentrating. Scores for the total PPQ can range from 0 to 14, while scores for the subscales can range from 0 to 3 for unwanted intrusions, 0 to 6 for avoidance, and 0 to 5 for increased arousal.

For this particular study, although a cutoff was not established for a positive finding, and women were not diagnosed with PTSD based on the results of the PPQ, clinicians at the local health center were notified if a participant had a significant number of positive answers. The majority of the participants (81.8%, n = 18) had between 0 and 3 positive answers. Of the remaining participants, 1 (4.5%) had four positive answers, 2 (9.1%) had five, and 1 (4.5%) had 12 positives, all of which the clinicians were notified about.

In past studies using the PPQ, with a sample that contained both mothers of high-risk infants and mothers of healthy infants, the PPQ had an alpha coefficient of 0.85 and a test-retest reliability of 0.92 over 2- to 4-week intervals (Quinnell & Hynan, 1999). Quinnell and Hynan also evaluated the validity of the PPQ by conducting a convergent and divergent validity study using the Impact of Event Scale (IES; Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979) and the Penn Inventory (PI), which measures the severity of PTSD (Hammarberg, 1992). Their results revealed substantial correlations between the PPQ and these two measures (IES: r(140) = 0.78, p < 0.001; PI: r(131) = 0.50, p < 0.001), supporting the validity of the PPQ (Quinnell & Hynan). Recently, Callahan, Borja, and Hynan (2006) developed a modified version of the PPQ using a Likert scale. This scale, however, was not available for use at the time the present study was conducted.

Procedure

Before data collection, approval was obtained through the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board, as well as by the local community health center where the research took place. Mothers who had given birth within the past 6 months were recruited at a local community health center while waiting for their 6-week postpartum appointment at the obstetrical center or while waiting for their newborn to be seen by the clinician. If interested, the mothers were brought to a private room, where the study was described in detail and any questions that the mothers had were answered. After answering any questions, informed consent was obtained, and the mothers were asked to complete a brief demographic background sheet and the PPQ. Confidentiality was ensured, because the participant's name was not located on her demographic information sheet or questionnaire, and her informed consent sheet was kept separate from her answers.

At the end of the PPQ, there was also one open-ended question, asking whether the mother wanted to share additional information about the birth of her child, which the participants could answer if they chose to do so. After completion of the PPQ, the number of “yes” answers was tallied to determine whether the mother was experiencing any of the symptoms of PTSD and, if so, to what extent she was experiencing them. If the mother was experiencing a particularly high number of symptoms, the community health center personnel were notified so that she could be monitored or referred to behavioral health professionals for counseling.

Spanish-speaking mothers were given the opportunity to participate through the use of the language line, a telephone interpretation service, where a medical interpreter read the informed consent and questionnaire to the mothers in Spanish. In total, the language line was used with three of the mothers, and was well-accepted by all three, who seemed to appreciate the opportunity to be involved in the study and appeared comfortable conversing with the use of the language line.

Data Analysis

Data were entered, computed, and analyzed using SPSS Version 14. After the data were analyzed and descriptive statistics of the study population were obtained, Pearson Correlations were run, and reliability of the PPQ scale was determined using Cronbach's alpha. Independent Sample Tests (t-tests) were run using SPSS Version 14 and considered significant at <0.05. Pearson Correlations with a two-tailed significance of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS and Microsoft Excel and Word were used to create data tables and graphs.

RESULTS

Sample

The total sample was composed of 22 women who had given birth within the past 6 months. Participating mothers were 18–40 years of age (mean age = 25.55, SD = 5.8) and had given birth 1.28–27.14 weeks prior to the study (mean = 7.51, SD = 6.28). The majority of the mothers were single (63.6%, n = 14), primiparas (54.5%, n = 12), and had experienced vaginal birth (72.7%, n = 16). The ethnicity of the mothers was divided, with 50% (n = 11) Hispanic, 31.8% (n = 7) Caucasian, 4.5% (n = 1) African American, 4.5% (n = 1) Asian, 4.5% (n = 1) Mexican, and 4.5% (n = 1) both Hispanic and Asian. Additional demographic and obstetrical variables are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Obstetrical Characteristics (N = 22)

| Variable | M (SD) | n | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 25.55 (5.81) | — | — |

| Weeks Since Giving Birth | 7.51 (6.28) | — | — |

| Parity | |||

| Primipara | 12 | 54.5 | |

| Multipara | 10 | 45.5 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 5 | 22.7 | |

| Single | 14 | 63.8 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Separated | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Other | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Education Level | |||

| Middle School | 1 | 4.5 | |

| High School | 12 | 54.5 | |

| Some College | 4 | 18.25 | |

| College Degree | 4 | 18.25 | |

| Associate Degree | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 11 | 50 | |

| Caucasian | 7 | 32 | |

| African American | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Asian | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Mexican | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Hispanic and Asian | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Birth | |||

| Vaginal | 16 | 72.7 | |

| Cesarean | 6 | 27.3 | |

| Feeding Method | |||

| Breast | 3 | 13.6 | |

| Bottle | 11 | 50.0 | |

| Both | 8 | 36.4 | |

| Prenatal Complications | |||

| 0 | 15 | 68.2 | |

| 1 | 5 | 22.7 | |

| 2 | 2 | 9.1 | |

| Perinatal Complications | |||

| 0 | 16 | 72.7 | |

| 1 | 5 | 22.7 | |

| 2 | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Postpartum Complications | |||

| 0 | 20 | 90.9 | |

| 1 | 2 | 9.1 | |

| Infant Prematurity | |||

| Yes | 4 | 18.2 | |

| No | 18 | 81.8 | |

| NICU Hospitalization | |||

| Yes | 1 | 4.5 | |

| No | 21 | 95.5 |

Mothers were asked whether they experienced any complications with their pregnancy, labor and birth, or postpartum period. Prenatally, 22.7% (n = 5) of the mothers experienced one complication, while 9.1% (n = 2) experienced two complications. Complications listed by the mothers included gestational diabetes, preterm labor, seizures, and a decreased fetal heart rate.

For perinatal (labor and birth) complications, 22.7% (n = 5) experienced one complication, while only 4.5% (n = 1) experienced two complications. Complications listed by the mothers included an emergency cesarean birth, slow cervical dilation, infection of the amniotic fluid, extreme pain as a result of a failed epidural, and the need for an episiotomy.

During the postpartum period, only 2 of the participants (9.1%) experienced complications. Complications included toxemia and a hypotonic uterus. Four mothers (18.2%) classified their infant as being premature, but only one infant (4.5%) needed hospitalization in a NICU. The characteristics of the sample are outlined in Table 1 and were obtained from the demographic information sheet that the mothers completed prior to completing the PPQ.

Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms

For this study, the alpha coefficient of the entire PPQ scale was found to be acceptable at 0.80. Alpha coefficients were also found for the scale's three subscales. For the first three items, which tested intrusion, the alpha coefficient was 0.80. The next six items, testing avoidance, had an alpha coefficient of 0.84. Both levels were determined to be acceptable. However, the final five questions, which tested increased arousal, had an alpha coefficient of 0.36, which may have been the result of a few unusual responses in a small data set.

In total, 22 mothers answered the 14 questions contained in the PPQ. The minimum number of positive answers was 0, and the maximum was 12 (mean = 2.32, SD = 2.64). For Questions 1, 3, and 5, which asked about bad dreams, flashbacks, and avoiding tasks, respectively, 9.1% (n = 2) of the study population answered positively. For Questions 2, 4, and 6, about upsetting memories, avoiding thoughts, and inability to remember, respectively, only 4.5% (n = 1) of the population answered positively. For Question 7, which asked about a loss of interest in activities, 13.6% (n = 3) answered positively, whereas for Question 8, about feelings of loneliness, 22.7% (n = 5) answered positively.

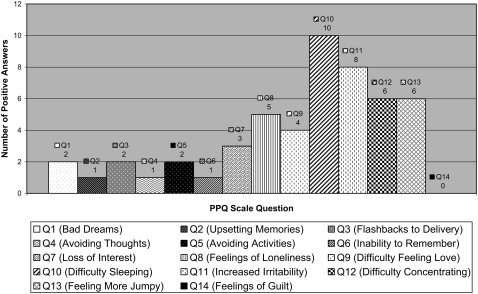

Question 9, which asked about difficulty feeling love or tenderness, recorded 18.2% (n = 4) of the study population as answering positively, while Question 10, about difficulty falling or staying asleep, had the highest number of positive responses, at 45.5% (n = 10). Question 11, which asked about being more irritable or angry than usual, also had a high positive response rate, with 36.4% (n = 8) positive responses. For Question 12, about difficulties concentrating, and Question 13, about feeling more jumpy, 27.3% (n = 6) of the study population answered positively. Question 14, however, which asked about feeling guilty about their child's birth, recorded no positive responses (n = 0). Refer to Table 2 and the Figure for detailed results.

TABLE 2.

The Perinatal Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire Results (N = 22)

| Variable | M (SD) | n | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1 (Bad Dreams) | |||

| No | 20 | 90.9 | |

| Yes | 2 | 9.1 | |

| Question 2 (Upsetting Memories) | |||

| No | 21 | 95.5 | |

| Yes | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Question 3 (Flashbacks to Birth) | |||

| No | 20 | 90.9 | |

| Yes | 2 | 9.1 | |

| Question 4 (Avoiding Thoughts) | |||

| No | 21 | 95.5 | |

| Yes | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Question 5 (Avoiding Activities) | |||

| No | 20 | 90.9 | |

| Yes | 2 | 9.1 | |

| Question 6 (Inability to Remember) | |||

| No | 21 | 95.5 | |

| Yes | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Question 7 (Loss of Interest) | |||

| No | 19 | 86.4 | |

| Yes | 3 | 13.6 | |

| Question 8 (Feelings of Loneliness) | |||

| No | 17 | 77.3 | |

| Yes | 5 | 22.7 | |

| Question 9 (Difficulty Feeling Love) | |||

| No | 18 | 81.8 | |

| Yes | 4 | 18.2 | |

| Question 10 (Difficulty Sleeping) | |||

| No | 12 | 54.5 | |

| Yes | 10 | 45.5 | |

| Question 11 (Increased Irritability) | |||

| No | 14 | 63.6 | |

| Yes | 8 | 36.4 | |

| Question 12 (Difficulty Concentrating) | |||

| No | 16 | 72.7 | |

| Yes | 6 | 27.3 | |

| Question 13 (Feeling More Jumpy) | |||

| No | 16 | 72.7 | |

| Yes | 6 | 27.3 | |

| Question 14 (Feelings of Guilt) | |||

| No | 22 | 100 | |

| Yes | — | — | |

| Entire Perinatal Posttraumatic | 2.32 (2.64) | 14 | — |

| Stress Disorder Questionnaire | |||

| Scale | |||

| Unwanted Intrusions | 0.23 (0.69) | — | — |

| Avoidance | 0.73 (1.45) | — | — |

| Increased Arousal | 1.36 (1.14) | — | — |

Number of Positive Answers per Perinatal PTSD Questionnaire

In addition to looking at each question individually and the scale as a whole, the PPQ was divided into three sections for data analysis purposes. For the first three questions, which measure the experience of unwanted intrusions, the minimum number of positive answers was 0, while the maximum was 3 (mean = 0.23, SD = 0.69). For the next six questions, which measure symptoms of avoidance, the minimum number of positive answers was 0, while the maximum was 6 (mean = 0.73, SD = 1.45). For the final five questions, which measure the level of increased arousal, the minimum number of positive answers was 0, while the maximum was 4 (mean = 1.36, SD = 1.14).

Participants were also given the opportunity to respond to one open-ended question, located at the end of the questionnaire, about the mother's labor and birth experience. Of the participants (N = 22), only 13.6% (n = 3) chose to answer the open-ended question. Of the 3 participants, 2 responded with positive reactions to their birth. Positive responses included, “I just didn't know that I could possibly love a human being so much. I can't imagine life without my son being in it.” Another mother stated:

The most positive [thing about my birth] was since I gave birth without anesthesia, it hurt a lot and gave me more strength to fight for my kids and not let them get taken away for my stupidity and substance abuse. I feel that has changed me because if I went through all that, I should keep on fighting and trying to be a great mother to my kids.

The last of the three responses focused on the negative aspect of the mother's experience:

[The most negative aspect about my birth experience was] the fact that me and the baby almost died, that the baby's father doesn't seem to care. The doctors don't seem to tell new mothers how difficult it is with newborns and that you have to get up every 3 hours to feed them.

The presence or absence of responses to the open-ended question was not found to have any impact on the number of positive responses to the PPQ.

Correlations

Pearson correlations were performed using the overall PPQ scale score, which was determined by the number of positive answers given by each study participant and by using the score for each of the three individual subscales of the PPQ (unwanted intrusions, avoidance, and increased arousal). It was determined that the overall PPQ score was positively correlated with the existence of both perinatal complications (r = 0.72, p = 0.000) and postpartum complications (r = 0.63, p = 0.002). All items were considered to be significant at the 0.05 level.

When Pearson correlations were performed for each of the three individual subscales of the PPQ, unwanted intrusions were significantly correlated with postpartum complications (r = 0.60, p = 0.003). In addition, increased arousal was significantly correlated with perinatal complications (r = 0.48, p = 0.025), while avoidance significantly correlated with both perinatal complications (r = 0.69, p = 0.000) and postpartum complications (r = 0.62, p = 0.002). The avoidance subscale was also significantly correlated with the birth of a premature infant (r = 0.51, p = 0.02).

Unlike its other relationships, avoidance was negatively correlated with Hispanic ethnicity (r = −0.43, p = 0.04). In addition, although it is not statistically significant, Caucasian ethnicity was positively correlated with avoidance (r = 0.41, p = 0.06). Because it is not statistically significant, however, the relationship between avoidance and Caucasian ethnicity can only be viewed as a trend.

The correlations between avoidance and ethnicity were further supported by Independent Sample Tests (t-tests) and Group Statistics. The mean avoidance score for participants in the Hispanic group was only 0.167, while the mean avoidance score for participants in the Caucasian group was 1.571, representing a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.04). This illustrates that the Hispanic women were less likely to experience avoidance than the Caucasian women.

DISCUSSION

Based upon the results from this small study, it appears that both perinatal complications and postpartum complications seem to be the main predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms after childbirth for this sample. In this study, perinatal complications listed by the mothers on the demographic sheet included slow cervical dilation, infection of the amniotic fluid, extreme pain as the result of a failed epidural, performance of an emergency cesarean birth, and the need for an episiotomy. Postpartum complications included toxemia and a hypotonic uterus.

These findings are consistent with previous research findings that emergency cesarean birth, induction of labor, prolonged labor, and instrumental vaginal births affect a woman's satisfaction with her birth experience and, therefore, the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms as a result of the trauma of her “shattered assumptions” (Maggioni et al., 2006, p. 86). Other studies have also supported the conclusion that an episiotomy can be an obstetric predictor of the development of PTSD after childbirth (Alder et al., 2006).

Also consistent with previous research, the birth of a premature infant was also found to be a predictor of the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms. However, in this particular study, it was only found to significantly influence the development of symptoms of avoidance, while previous studies determined that the birth of a premature infant influences all three categories of PTSD symptoms (Holditch-Davis, Bartlett, Blickman, & Miles, 2003). This discrepancy is most likely due to the fact that only one infant classified as premature by the mothers needed hospitalization in a NICU, as well as to the low sample size of the population.

This study, consistent with previous studies such as that by Maggioni et al. (2006), also found increased arousal to be the most commonly reported symptom of posttraumatic stress, with a mean number of positive responses of 1.36, and a standard deviation of 1.14, compared to a mean of 0.23 for unwanted intrusions, and a mean of 0.73 for avoidance. In other studies, hyperarousal has been accountable for up to two thirds of the “partially symptomatic” sample and consistently has the highest reported frequency of PTSD symptoms (Slade, 2006).

Unlike any previous studies, results from this study preliminarily show a relationship between ethnicity and the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms. More specifically, results demonstrate that mothers identifying themselves as Hispanic are less likely to develop symptoms of avoidance. A trend that mothers identifying themselves as Caucasian are more likely to develop such symptoms was also demonstrated, although not statistically significant.

This preliminary relationship demonstrates that the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms may, in fact, be culturally influenced. However, it is important to note that the population treated at the health center where the research was conducted was largely Hispanic. Therefore, those identifying themselves as Hispanic may have simply had a greater support system, which has been shown to be an important protective factor against the development of PTSD. A greater support system has also been shown to be effective in promoting mental health following childbirth (Bailham & Joseph, 2003).

In order to further investigate whether there is, in fact, a correlation between ethnicity and the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms, or lack thereof, more research would need to be conducted with a larger sample size and with a more diverse patient population. Future research studies should seek to determine whether the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms is culturally influenced, and more efforts should be made in local community health clinics to identify PTSD after childbirth.

Based on previous research, up to one third of women have been found to view their labor and birth as traumatic, even though only approximately 2%–6% may go on to experience a total PTSD (Alder et al., 2006; Ayers & Pickering, 2001; Creedy et al., 2000). PTSD after childbirth, and its symptoms, is clearly an issue that needs to be addressed in all obstetrical health-care settings with more vigilance than is currently being used. More important, all efforts to prevent childbirth from being a traumatic experience need to be taken, including, in some cases, better communication with the laboring and birthing mothers.

As Beck (2004a) found, birth trauma lies in the eye of the beholder, and therefore, clinicians should elicit and carefully listen to women's birth stories so that they can detect those at risk for PTSD and provide them with the proper treatment and resources should they require it. More efforts should also be made by childbirth educators to inform pregnant women and their partners about PTSD and its symptoms prior to and after their birth experience to provide for earlier detection should PTSD or its symptoms develop. By detecting symptoms early, better care can be provided to mothers who experience posttraumatic stress symptoms after childbirth, and better outcomes can occur.

Birth trauma lies in the eye of the beholder, and therefore, clinicians should elicit and carefully listen to women's birth stories so that they can detect those at risk for PTSD and provide them with the proper treatment and resources should they require it.

Footnotes

For more information about the Perinatal PTSD Questionnaire, see the 2006 article by Callahan, Borja, and Hynan, “Modification of the Perinatal PTSD Questionnaire to Enhance Clinical Utility,” published in the Journal of Perinatology, 26, 533–539 (available online at http://www.psyc.unt.edu/∼jennifercallahan/EnhancedPPQ.pdf).

For more information about the Perinatal PTSD Questionnaire, see the 2006 article by Callahan, Borja, and Hynan, “Modification of the Perinatal PTSD Questionnaire to Enhance Clinical Utility,” published in the Journal of Perinatology, 26, 533–539 (available online at http://www.psyc.unt.edu/∼jennifercallahan/EnhancedPPQ.pdf).

REFERENCES

- Alder J, Stadlmayr W, Tschudin S, Bitzer J. Post-traumatic symptoms after childbirth: What should we offer? Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;27(2):107–112. doi: 10.1080/01674820600714632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA] 1980. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA] 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers S, Pickering A. Do women get PTSD as a result of childbirth? Birth. 2001;28(2):111–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2001.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailham D, Joseph S. Post-traumatic stress following childbirth: A review of the emerging literature and directions for research and practice. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2003;8(2):159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Beck C. T. Birth trauma: In the eye of the beholder. Nursing Research. 2004a;53(1):28–35. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck C. T. Post-traumatic stress disorder due to childbirth: The aftermath. Nursing Research. 2004b;53(4):216–224. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Rothstein H, Cohen J. 2001. Power and precision. Englewood, NJ: Biostat. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan J, Borja S, Hynan M. Modification of the Perinatal PTSD Questionnaire to enhance clinical utility. Journal of Perinatology. 2006;26:533–539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan J, Hynan M. Identifying mothers at risk for postnatal emotional distress: Further evidence for the validity of the Perinatal Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire. Journal of Perinatology. 2002;22:448–454. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigoli V, Gilli G, Saita E. Relational factors in psychopathological responses to childbirth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;27(2):91–97. doi: 10.1080/01674820600714566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creedy D, Shochet I, Horsfall J. Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: Incidence and contributing factors. Birth. 2000;27(2):104–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnocka J, Slade P. Prevalence and predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;39:35–51. doi: 10.1348/014466500163095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMier R. L, Hynan M. T, Harris H. B, Manniello R. L. Perinatal stressors as predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress in mothers of infants at high risk. Journal of Perinatology. 1996;16(4):276–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarberg M. Penn Inventory for posttraumatic stress disorder: Psychometric properties. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;4:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Holditch-Davis D, Bartlett T. R, Blickman A. L, Miles M. S. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers of premature infants. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2003;32:161–171. doi: 10.1177/0884217503252035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M. J, Wilner N. R, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective distress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;13:139–145. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggioni C, Margola D, Filippi F. PTSD, risk factors, and expectations among women having a baby: A two-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;27(2):81–90. doi: 10.1080/01674820600712875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinnell F, Hynan M. Convergent and discriminant validity of the Perinatal PTSD Questionnaire (PPQ): A preliminary study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12(1):193–199. doi: 10.1023/A:1024714903950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sichel D, Driscoll J. W. 1999. Women's moods: What every woman must know about hormones, the brain, and emotional health. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Slade P. Towards a conceptual framework for understanding post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth and implications for further research. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;27(2):99–105. doi: 10.1080/01674820600714582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]