Abstract

Female gender is a risk factor for drug-induced arrhythmias associated with QT prolongation, which results mostly from blockade of the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) channel. Some clinical evidence suggests that oestrogen is a determinant of the gender-differences in drug-induced QT prolongation and baseline QTC intervals. Although the chronic effects of oestrogen have been studied, it remains unclear whether the gender differences are due entirely to transcriptional regulations through oestrogen receptors. We therefore investigated acute effects of the most bioactive oestrogen, 17β-oestradiol (E2) at its physiological concentrations on cardiac repolarization and drug-sensitivity of the hERG (IKr) channel in Langendorff-perfused guinea pig hearts, patch-clamped guinea pig cardiomyocytes and culture cells over-expressing hERG. We found that physiological concentrations of E2 partially suppressed IKr in a receptor-independent manner. E2-induced modification of voltage-dependence causes partial suppression of hERG currents. Mutagenesis studies showed that a common drug-binding residue at the inner pore cavity was critical for the effects of E2 on the hERG channel. Furthermore, E2 enhanced both hERG suppression and QTC prolongation by its blocker, E4031. The lack of effects of testosterone at its physiological concentrations on both of hERG currents and E4031-sensitivity of the hERG channel implicates the critical role of aromatic centroid present in E2 but not in testosterone. Our data indicate that E2 acutely affects the hERG channel gating and the E4031-induced QTC prolongation, and may provide a novel mechanism for the higher susceptibility to drug-induced arrhythmia in women.

Drug-induced rate-corrected QT (QTC) prolongation leading to torsade de pointes (TdP) results mostly from blockade of the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) channel which conducts the rapid component of the delayed rectifier K+ current (IKr) (Clancy et al. 2003). Female sex is an independent risk factor to develop TdP (Makkar et al. 1993; Lehmann et al. 1996; Drici et al. 1998; James et al. 2007). Such higher susceptibility of females to TdP is associated with prolonged baseline QTC intervals in women (Bazett, 1920). It is likely that sex hormones have some influences on the gender difference in QTC intervals, which reflect sex-related differences in the ionic process underlying cardiac repolarization (Drici et al. 1996; Pham et al. 2001; Hulot et al. 2003; Abi-Gerges et al. 2004; Bai et al. 2005). The susceptibility of drug-induced arrhythmias fluctuates considerably during the menstrual cycle in women: the drug-induced QTC prolongation is exaggerated in the late follicular phase where oestrogen level is the highest (Rodriguez et al. 2001). In addition, a hormone replacement therapy with administration of oestrogen alone prolongs QTC intervals in postmenopausal women (Kadish et al. 2004). These clinical data implies that oestrogen prolongs QTC intervals leading to strengthen drug-induced QTC prolongation in women. Unraveling of the underlying mechanism can be a clue to avoid this potentially lethal side-effect. Although influences of oestrogen in cardiac repolarization have been studied by analysis of properties of cardiac ion channels with long-term treatments of oestrogen concerning genomic responses (Drici et al. 1996; Hara et al. 1998; Pham et al. 2001), it remains unclear whether the gender differences in repolarization and drug-induced TdP are due entirely to transcriptional regulations through oestrogen receptors.

It is now convincing that, in addition to genomic responses, sex-hormones can trigger rapid signalling responses referred to as nongenomic responses (Razandi et al. 1999; Valverde et al. 1999; Bai et al. 2005). Here we focused our experiments on nontranscriptional, ‘acute’, effects of oestrogen on ion channels contributing to cardiac repolarization. We find that the physiological concentrations of 17β-oestradiol (E2) acutely inhibit IKr and hERG currents in a receptor-independent manner and increase sensitivity of IKr channels to their specific blocker, E4031. Thus our study reveals a previously uncharacterized mechanism by which receptor-independent effects of oestrogen alter cardiac repolarization leading to susceptibility of drug-induced arrhythmias.

Methods

Adult guinea pigs (white Hartley; 240–410 g) were fully anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of urethane (1.5 mg g−1), and then killed by cervical dislocation in accordance with regulations on animal experimentation by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Tokyo Medical and Dental University and Chiba University. Numbers of animals used in this study were 4 male and 51 female adult guinea pigs. Hearts were quickly removed, mounted on a Langendorff column, and were used for ECG recordings and isolation of cardiac myocytes as described as follows.

ECG recordings in Langendorff-perfused hearts

ECG of the surface of left ventricle in isolated Langendorff-perfused adult female guinea pig heart was obtained on the epicardium as previously described (Bai et al. 2005). QT intervals were corrected (QTC) for heart rate using the Bazett formula QTC= QT/(RR)1/2.

Patch-clamp

Either cardiomyocyte or culture cell was placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (IMT-2 or IX-71, Olympus, Japan), and cell membranes were clamped with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, USA). Signals were low-pass filtered at 2–5 kHz, sampled at 1–2 kHz, and compensated for cell capacitance. Series resistance was not compensated. No correction for the liquid junction potential was made. Cell capacitances of cardiomyocytes, HEK293 cells and CHO-K1 cells were 80–150 pF, 10–30 pF and 7–20 pF, respectively.

Patch-clamp recordings from cardiac myocytes

Action potentials and membrane currents were recorded at 36 ± 1°C from enzymatically isolated adult female guinea pig ventricular myocytes by using a perforated configuration of patch-clamp technique to minimize the wash-out of cytosolic components (Bai et al. 2005). Control bath solution contained (mm): 135 NaCl, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.53 MgCl2, 5.5 glucose and 5 Hepes, pH 7.4. Drugs were added to the bath solution by using a rapid perfusion system (Kurokawa et al. 2001). Pipette resistances (borosilicate) were 2–3 MΩ when filled with a pipette solution containing (mm): 110 aspartic acid, 30 KCl, 5 Mg-ATP, 5 creatine phosphate dipotassium salt, 5 Hepes, pH 7.4. To achieve patch perforation, Amphotericin B (0.3–0.6 mg ml−1) (Nacalai, Japan) was added in the pipette solution judged by the time course of capacity transients monitored as a function of time after attaining gigaohm seals. Adequate series resistances (less than 5-times of the pipette resistances) were usually attained within 10 min after the gigaohm seal formation.

Action potentials were elicited at 1 Hz by application of a 2 ms current injection of suprathreshold intensity (∼20% over threshold). Action potential durations measured at 90% repolarization (APD90) were averaged from five beats at stimulation frequencies of 1 Hz.

When to record IKr, L-type Ca2+ currents (ICa,L) and slow delayed rectifier K+ currents (IKs) were blocked by adding nisoldipine (5 μm) and chromanol 293B (10 μm), respectively, to the bath solution. The IKr component was determined by subtracting the traces in the presence of E4031 (5 μm), a selective IKr blocker. The IKr tail currents were monitored by analysis of the peak tail currents measured at −40 mV after test pulses to +20 mV from a holding potential (VH) of −50 mV (0.1 Hz). We took the measurements as the data only when fluctuations of the baseline levels were within 10% of the peak IKr tail currents (after +20 mV pulses). Activation (isochronal) of IKr (Fig. 3A) was studied by analysis of the tail currents at −40 mV after a series of 140 ms activating pulses (10 mV increments).

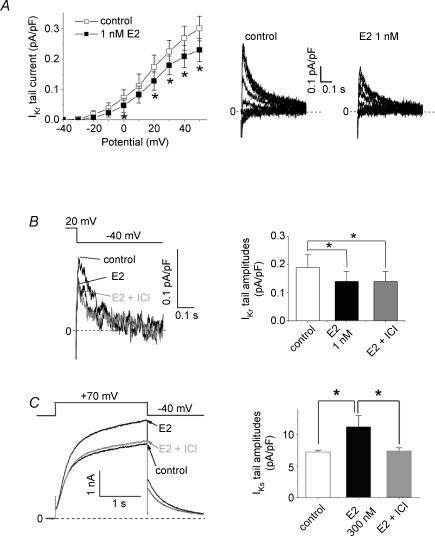

Figure 3. Receptor-independent suppression of cardiac IKr currents by E2.

Membrane currents were recorded from guinea pig ventricular myocytes as described in the Methods. A, effect of E2 at 1 nm on IKr tail currents (10 cells from 8 hearts). IKr tail currents were measured at −40 mV after a series of 140 ms test pulses from −40 mV to +50 mV (10 mV increments, 0.1 Hz; VH, −50 mV). Representative traces (left) are obtained by subtracting the traces in the presence of E4031 (5 μm). Plots (right) are peak amplitudes of tail currents (mean ±s.e.m.) before (control, □) and 10 min after application of drugs (▪). *P < 0.05, paired Student's t test. B, receptor-independent IKr suppression by E2. ICI182,780 was added to the external solution with E2 after testing the effect of E2 alone. Representative traces (left) and plots (right) show that application of an oestrogen receptor antagonist, ICI182,780 (10 μm), did not inhibit the IKr suppression by E2 at 1 nm (8 cells from 7 hearts). IKr tail currents were measured as described in A. *P < 0.05, ANOVA with repeated measures. C, receptor-dependent IKs enhancement by E2. The IKs enhancement by E2 (300 nm) was abolished by addition of ICI182,780 at 10 μm (4 cells from 4 hearts). Representative traces (left) show complete inhibition by the antagonist. Note that the working concentration of E2 is higher than that in B where ICI182,780 showed no effects. IKs were elicited by 2 s test pulses to +70 mV (0.1 Hz, VH−40 mV). *P < 0.05, ANOVA with repeated measures.

When to record IKs, ICa,L and IKr currents were blocked by adding 5 μm nisoldipine and 5 μm E4031, respectively, to the external solution (Bai et al. 2005). IKs currents were elicited by 2 s pulses to +70 mV (VH of −40 mV, 0.1 Hz).

When to record ICa,L, K+ ions both in the internal and external solutions were replaced by Cs+ ion in order to suppress potassium channels (Bai et al. 2005). Conductance through the IKs channel and the IKr channel were blocked by adding choromanol 293B (10 μm) and E4031 (5 μm), respectively, to the bath solution. ICa,L currents were elicited by 100 ms pulses to 0 mV (VH of −80 mV, 0.1 Hz). INa currents were inactivated by applying 50 ms prepulses to −40 mV prior to the test pulses.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells stably expressing hERG (Wu et al. 2003) were cultured in D-MEM (phenol red-free) supplemented with 10% charcoal-treated FBS (to wash off steroids) and 0.8% geneticin. For transient transfection, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells (Riken) were cultured in Ham's F12 medium or F12/D-MEM (phenol red-free) supplemented with charcoal-treated 10% FBS. CHO-K1 cells were transiently transfected with cDNAs for hERG and CD8 (1 and 1 μg each), and were used within 48 h as previously described (Kurokawa et al. 2003). hERG gene and the mutants (kindly gifted from Dr M. Sanguinetti, University of Utah) were subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 + (Invitrogen) at BamHI and HindIII sites. Dynabeads M-450 anti-CD8 beads (1 μg ml−1, Dynal, Oslo, Norway) were used to identify transfected cells by eyes. All cells were kept in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2, and plated into culture dishes the day before electrophysiological experiments.

Patch-clamp recordings from culture cells

hERG channel currents were recorded at room temperature (22 ± 1°C) by using the perforated patch-clamp technique as previously described (Kurokawa et al. 2001; Kurokawa et al. 2003). The control bath solution contained (mm): 132 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 mm glucose, 10 Hepes, pH 7.4. Drugs were added to the bath solution rapidly (> 20 ms) (Kurokawa et al. 2001). Dyna-beads M-450 were added to the bath solution for CHO-K1 cells. Pipettes (2–4 MΩ resistances) were filled with a pipette solution containing (mm): 110 potassium aspartate, 5 K2-ATP, 11 EGTA, 5 Hepes, 1 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2, pH 7.4. Amphotericin B (0.3 mg ml−1) was added in the pipette solution to achieve patch perforation (10–20 MΩ; series resistance).

Unless otherwise noted, hERG channel tail-current amplitude was monitored at 0.1 Hz by analysis of peak deactivating tail current recorded at −40 mV after 2 s depolarizing test pulses to +20 mV from a VH of −80 mV. Current zero level (no activation) was determined by applying 25 ms pulses to −40 mV preceding the test pulses. The hooks of tail currents which are due to recovery from the channel inactivation were compensated by extrapolating tail currents back to the moment of repolarization after test pulses (Sanguinetti & Xu, 1999). In the mutagenesis study of hERG using CHO-K1 cells, tests and negative control without drug application were run on the same day.

The hERG activation was measured from hERG stable-expressing HEK cells elicited by 2 s test pulses to +20 mV in 10 mV increments at 0.1 Hz from a VH of −80 mV, and deactivated by returning to −40 mV. Peaks of tail currents were plotted as function of the hERG activation. Activation curves were drawn with a fit of each data to the Boltzmann equation; I/Imax=G/Gmax={1 + exp[−(Vm−V1/2)/k]}−1. G/Gmax is normalized chord conductance at Vm to the maximum chord conductance. V1/2 is the potential where the conductance is half-maximally activated, and k is the slope factor.

The time course of deactivation was determined from a bi-exponential fit of tail currents recorded at potentials ranging from −120 mV to −40 mV (20 mV increments) after the 1 s prepulses to +40 mV. To assure all channels were at the resting state, the stimulation was applied every 10 s. The hook of the tail current results from recovery of channels from an inactivated state and was not included in the exponential fitting procedure for best fit with the bi-exponential function.

Dose–response curves

As the effects of hormones did not show complete inhibition, curves represent the best fit of data points with Langmuir's isotherm (Ko et al. 1997): Y(ratio of control)=A*Kd/(Kd+[drug]) + 1 −A, where A is the drug-sensitive component (ratio) and [drug] is the concentration of drug (hormone).

In case of the blockade of hERG currents by E4031, dose–response curves were drawn with a fit of each data to Hill equation; Y(ratio of control)= 1/{1 + ([drug]/IC50)p}, where p is the slope factor and [drug] is the concentration of drug (E4031). Either in the absence or the presence of hormones, plots were normalized tail amplitudes relative to the values just before application of E4031. Time control was obtained by the same protocol in the absence of E2 or DHT. Each plot represents mean ±s.e.m. of data from individual cells. Experiments in the absence or the presence of hormones were done in the same day.

Materials

E2 and ICI182,780 were purchased from Sigma (USA) and TOCRIS (USA), respectively. 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT; the active form of testosterone, not metabolized by aromatase) was purchased from WAKO (Japan). E4031 and chromanol 293B were gifts from Esai Co. Ltd (Japan) and Sanofi-Aventis Group (Japan), respectively. All other materials were of reagent grade quality and obtained from standard sources. Stock solutions of E2 at 10 mm (in ethanol), ICI182,780 at 5 mm (in dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO), DHT at 10 mm (DMSO), nisoldipine at 10 mm (methanol), E4031 at 10 mm (H2O) and chromanol 293B at 10 mm (DMSO) were diluted to final concentrations in the external solutions. In cardiac myocytes, final concentrations of solvents were included in the control solutions. Final concentrations of solvents (DMSO or ethanol) for stock solutions were confirmed to have no significant effects on currents in culture cells (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Data analysis

All values are presented as mean ±s.e.m. pCLAMP 9.2 software (Axon Instruments) was used to both acquire and analyse data for the patch-clamp experiments. Graphical and statistical analyses were carried out using Origin 7.0 J software (Microcal), SigmaPlot (Hulinks), and InStat program (GraphPad). Unless otherwise noted, statistical significance was assessed with Student's t test for simple comparisons and ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post test for multiple comparisons. For analysis of action potential raw data, statistical significance was assessed with Wilcoxon test for simple comparisons and Friedman test followed by Dunn's post test for multiple comparisons. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

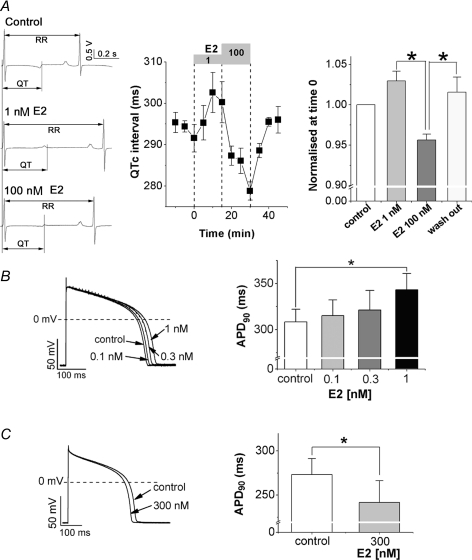

Bi-directional effects of E2 on cardiac repolarization

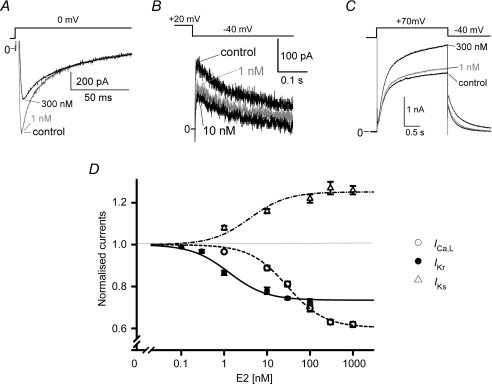

To investigate acute effects of E2 on cardiac repolarization, E2 was applied to isolated Langendorff perfused female guinea pig hearts and perforated patch-clamped female guinea pig ventricular myocytes (Fig. 1). In Fig. 1A, we show that E2 at 1 nm, nearly the highest physiological concentration in adult women (Hulot et al. 2003), prolonged QTC intervals in the surface ECG of Langendorff hearts, whereas E2 at 100 nm, beyond the physiological levels, shortened QTC intervals. The biphasic effects of E2 on QTC intervals were both acute and can be washed off within 10 min (Fig. 1A). To test whether the biphasic effects of E2 can be seen in single cardiomyocytes, we investigated effects of E2 on APD measured from guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Lower concentrations of E2 (0.1–1 nm) prolonged APD in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). E2 (1 nm) significantly prolonged APD90 by 11 ± 1% (n = 6). In contrast, high concentration of E2 (300 nm) significantly shortened APD90 by 14 ± 4% (n = 8, Fig. 1C), which is consistent with the data for QTC intervals and our previous report (Bai et al. 2005) showing that E2 shortens APD by enhancement of IKs and suppression of ICa,L through a nongenomic pathway of hormone receptors (Bai et al. 2005). Although E2 at 300 nm enhanced IKs by 30 ± 4% (n = 5) and suppressed ICa,L by 37 ± 1% (n = 5), E2 at 1 nm showed significant effects on neither IKs nor ICa,L (Fig. 2). The bi-directional effects of E2 on action potentials were seen in male guinea pig myocytes as well as females (Supplemental Fig. 2). To explore a physiological impact of the acute effects of E2, we focused on its effect only at physiological levels in women.

Figure 1. Bi-directional effects of E2 on QTC intervals and APD90 in guinea pig hearts.

A, effects of E2 on QTC intervals measured from surface ECGs of isolated Langendorff-perfused guinea pig hearts (n = 5). Representative ECGs are shown on left. Time course (middle) and summary of data (right) show that low concentration of E2 (1 nm) prolonged QTC intervals, whereas high concentration of E2 (100 nm) shortened QTC intervals. Each concentration of E2 (numbers in nm) was applied as indicated by grey boxes above the panel (middle). The QTC intervals 15 min after application of each E2 concentration or wash-out are summarized as the ratio (mean ±s.e.m.) relative to control QTC interval before E2 application (right). *P < 0.05, Friedman test. B, effects of low concentrations of E2 on action potentials recorded from patch-clamped guinea pig ventricular myocytes (6 cells from 4 hearts). Representative traces (left) and bars (right) show that E2 prolonged APD90. E2 at 0.1, 0.3 and 1 nm were sequentially applied from the external side after ensuring stabilization of AP at each condition (5–15 min). Bars (mean +s.e.m.) represent APD90 obtained as average of 5 traces in the control and each concentration of E2. *P < 0.05, Friedman test. C, effects of a high concentration of E2 on action potentials recorded from cardiomyocytes. APD90 was significantly shortened by E2 at 300 nm (8 cells from 6 hearts). Data were obtained as described in B. Shown are representative action potential traces (left) and bars plotting APD90 (right). *P < 0.05, Wilcoxon test.

Figure 2. Effects of E2 on cardiac ion channels.

Membrane currents are recorded from guinea pig ventricular myocytes as described in the Methods. E2 was applied cumulatively to the bath solution. A, representative ICa,L traces. ICa,L were elicited by 0 mV pulses in the absence (control) and the presence of E2 (1 or 300 nm). E2 at 300 nm suppressed ICa,L. B, representative IKr traces. IKr tail currents were measured at −40 mV after test pulses to +20 mV (0.1 Hz, VH−50 mV) in the absence (control) and the presence of E2 (1 or 10 nm). The tail amplitudes were obtained by subtracting the traces with E4031 at 5 μm. E2 at 1 nm suppressed IKr. C, representative IKs traces. IKs were elicited by +70 mV pulses in the absence (control) and the presence of E2 (1 or 300 nm). E2 at 300 nm enhanced IKs. D, summary of concentration-dependent effects of E2 on ICa,L, IKr and IKs. Curves represent the best fit of data points with Langmuir's isotherm, where Kd is the dissociation equilibrium constant and A is the drug-sensitive component. ICa,L (5 cells from 4 hearts); Kd= 29.5 nm and A= 0.40. IKr (5 cells from 5 hearts); Kd= 1.3 nm and A= 0.27. IKs (5 cells from 3 hearts); Kd= 39.4 nm and A= 0.25.

Receptor-independent suppression of the native IKr currents by E2

We investigated effects of E2 on IKr which is an important contributor to cardiac repolarization in addition to IKs and ICa,L in female guinea pig ventricular myocytes (Fig. 2). Acute external application of E2 partially suppressed activity of native IKr channels in a concentration-dependent manner, and the data were best fitted with Langmuir's isotherm with a Kd value of 1.3 nm and the maximal fractional inhibition (Imax) of 27% (Fig. 2D). The Kd values suggest that physiological levels of E2 suppress IKr currents with a little or no effect on IKs and ICa,L, which can result in the APD prolongation as seen in Fig. 1B. E2 at 1 nm significantly suppressed peaks of tail IKr currents recorded after test pulses at 0, +20, +30, +40 and +50 mV (Fig. 3A, n = 10). The E2-induced IKr suppression (76 ± 5% of control, n = 8) was not recovered by subsequent addition of ICI182,780, an oestrogen receptor antagonist, at 10 μm to the bath solution (77 ± 5% of control, n = 8, Fig. 3B). When ICI182,780 at 10 μm was applied prior to application of E2 at 1 nm, E2 suppressed IKr significantly (before E2; 94 ± 4%, after E2 70 ± 4%, n = 6: Supplemental Fig. 3). In contrast, the E2-induced IKs enhancement was abolished by the same administration of ICI182,780 (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the E2-induced IKr suppression was independent of oestrogen receptors.

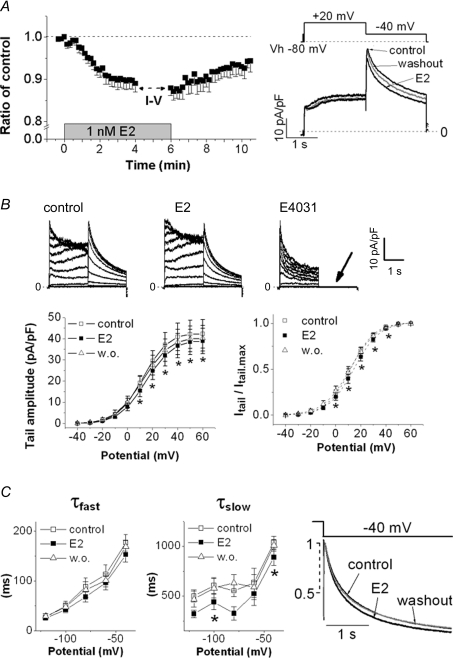

Effects of E2 on voltage-dependence of the hERG channel gating

To dissect the receptor-independent modification of E2 on IKr, we investigated effects of E2 on recombinant IKr recorded from HEK293 cells expressing hERG stably and no intrinsic oestrogen receptors (Finlay et al. 2004). E2 at 1 nm suppressed hERG tail currents by about 10% acutely within 2 min. Then, the wash-out of E2 partially recovered the inhibition, confirming a receptor-independent inhibition of the hERG currents by E2 (Fig. 4A, n = 9). Figure 4Bleft shows that the reduction was significant only when to apply positive test pulses over +10 mV (Fig. 4B, n = 9). The suppression of Imax was not reversible and not concentration-dependent (7.7% suppression at 1 nm, n = 9; 5.7% suppression at 3 nm, n = 8), while the positive shift of activation curve was reversible and concentration-dependent (2.8-mV shift at 1 nm; 4.0-mV shift at 3 nm) (Table 1). Thus, the significant suppression of hERG currents elicited by +20 mV test pulses (Fig. 4A) may result from the positive shift of activation curve by about 3–4 mV. In addition, E2 hastened the rate of slow deactivation significantly, and the effect was recovered 10 min after the wash-out of E2 (Fig. 4C, n = 8). These results indicate that E2 suppresses hERG currents by modulating the gating kinetics rather than by blocking the channel pore.

Figure 4. Effects of E2 on hERG gating recorded from HEK293 cells stably expressing hERG.

A, E2 (1 nm) suppressed tail hERG currents. HERG tail currents were recorded at −40 mV after +20 mV test pulses (VH: −80 mV). Time course of peak tail amplitudes (left) is shown as ratios of the control, the value before the E2 application (n = 9). The break is to measure I–V relationships in B. Representative current traces are shown on right. B, positive shift of voltage-dependent hERG activation by E2. The hERG activation was studied by analysis of deactivating tail currents recorded at −40 mV after a series of 2 s test pulses (10 mV increments, 0.1 Hz). VH was −80 mV. Representative traces from a single cell before (left) and after (middle) application of E2 (1 nm), and after subsequent application of E4031 (5 μm), are shown above the plots. E4031 completely blocked hERG tail currents (arrow in the trace). Peaks of tail currents (lower left) and normalized tail currents (lower right) were plotted as function of the hERG activation (n = 9). Plots (right) were fitted with the Boltzman equation (see Methods). E2 shifted the activation curve to the positive direction. *P < 0.05, ANOVA with repeated measures. C, acceleration of hERG deactivation process by E2. After +40 mV pulses (1 s) were applied, deactivating tail currents were elicited by 3 s test pulses from −120 mV to −40 mV (20 mV increments, 0.1 Hz, VH−80 mV). Fast (τfast, left) and slow (τslow, middle) time constants of deactivation are plotted against the test potentials before (control), 5 min after application of E2, and 5 min after washout (n = 8). Normalized tail currents at −40 mV are averaged in each condition (right). *P < 0.05, ANOVA with repeated measures.

Table 1.

Change in voltage dependence of the hERG activation by E2

| Control | E2 | Washout | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 nm E2 (n = 9) | |||

| V1/2 (mV) | 11.8 ± 1.9 | 14.4 ± 2.3*† | 11.3 ± 2.7 |

| ΔV1/2versus control (mV) | — | 2.8 ± 0.6† | −0.4 ± 0.9 |

| Slope factor (k) | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 10.2 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.2 |

| Imax (pA pF−1) | 42.7 ± 6.4 | 39.4 ± 5.7* | 39.1 ± 5.9* |

| 3 nm E2 (n = 8) | |||

| V1/2 (mV) | 9.3 ± 0.9 | 13.2 ± 1.6*† | 9.4 ± 1.0 |

| ΔV1/2versus control (mV) | — | 4.0 ± 1.4† | 0.1 ± 0.9 |

| Slope factor (k) | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 10.0 ± 0.2* | 9.4 ± 0.2 |

| Imax (pA pF−1) | 45.9 ± 7.8 | 43.3 ± 7.7*† | 45.2 ± 8.8* |

P < 0.05 versus Control;

P < 0.05 versus wash-out, ANOVA with repeated measures.

The concentration-dependent effect of E2 on hERG currents within the physiological range

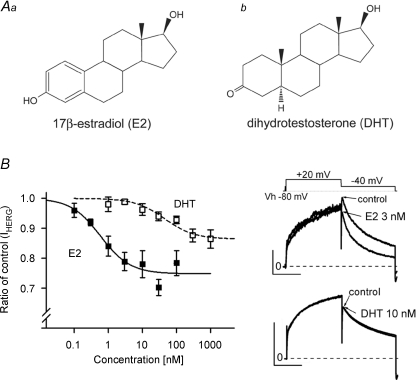

We next investigated the concentration-dependence of E2-induced hERG suppression by recording hERG currents in HEK293 cells as described in Fig. 3A. E2 suppressed hERG tail currents in a concentration-dependent manner, and the data were best fitted with Langmuir's isotherm with a Kd value of 0.6 nm and Imax of 25%. The Kd value indicates that physiological levels of E2 can suppress hERG currents, and such partial suppression of hERG currents is consistent with an idea that E2 works as a gating modifier rather than as a pore blocker. It is intriguing to compare the effects of E2 and DHT on hERG currents, because the chemical structures of E2 and DHT are very similar except for the presence of an aromatic ring in E2 that is converted by the aromatase from androgen (Fig. 5A). As we have previously shown for IKr in cardiac myocytes (Bai et al. 2005), DHT at 10 nm did not show significant effects on recombinant hERG currents (Fig. 5B). Although higher concentrations of DHT than 30 nm reduced hERG currents slightly with the maximal fractional inhibition of 14%, a Kd value of 44.7 nm suggests no significant effect within the physiological range.

Figure 5. Concentration-dependent suppression of hERG currents by E2 and DHT.

A, chemical structures of E2 (a) and DHT (b). Note the presence of an aromatic ring in E2, but not in DHT. B, concentration-dependent curves of hERG inhibition by E2 and DHT. HERG currents recorded from HEK293 cells stably expressing hERG were measured as indicated in Fig. 4A. Plots (mean ±s.e.m., left) are ratios of the control, the tail amplitudes before the drug application. One or two concentrations were tested in single cell. Representative traces are superimposed before (control) and after application of E2 at 3 nm (upper right) or DHT at 10 nm (lower right), showing that only E2 suppresses hERG currents. Scale, 10 pA pF−1, 1 s. Curves represent the best fit of data points with Langmuir's isotherm as in Fig. 2D. E2 (n = 3–9); Kd= 0.6 nm and A= 0.25. DHT (n = 4–7); Kd= 44.7 nm and A= 0.14.

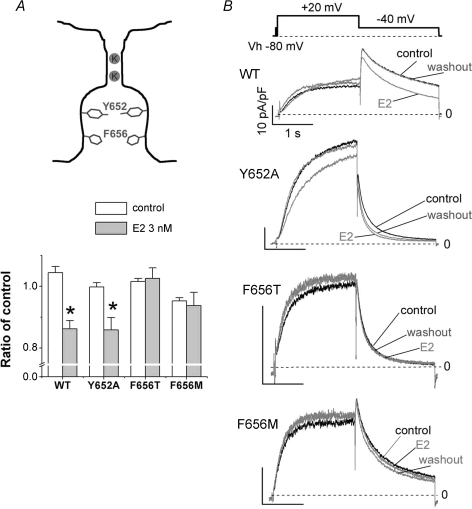

Influence of site-directed mutagenesis of the hERG drug-binding site on the effect of E2

We next explored which amino acid residues of the hERG channel protein are crucial for the E2-induced modulation of the hERG channel. The aromatic residues, Tyr652 and Phe656, that face to the central cavity of the hERG channel pore are important structural determinants of the common drug-binding site that favour to bind to hERG blocking charged amines with a phenyl-ring (Mitcheson et al. 2000; Clancy et al. 2003; Fernandez et al. 2004). As only E2, not DHT, has an aromatic ring in the chemical structure (Fig. 5A), we addressed a question whether the common drug-binding site involves in the hERG modulation induced only by E2 not by DHT. In Fig. 6, we introduced Ala-substitution at Tyr652 (Y652A) and Thr-substitution at Phe656 (F656T) to disrupt the interaction between drugs and the channel, and also employed Met-substitution at Phe656 (F656M), which keeps hydrophobic volume of side chain and has little or no effect on sensitivity of hERG blockers (Fernandez et al. 2004). Because these site-directed mutagenesis markedly reduce the current amplitudes (Fernandez et al. 2004), we used CHO-K1 cells which have smaller background K+ currents compared with HEK293 cells (Kurokawa et al. 2001) and CHO-K1 cells do not express oestrogen receptors (Razandi et al. 1999). Application of E2 suppressed significantly hERG peak tail currents recorded from CHO-K1 cells over-expressing hERG either of wild type or Y652A. E2 modified the gating kinetics in Y652A as seen in the wild type channel (Supplemental Fig. 3A, Supplemental Table 1). In contrast, E2 did not inhibit both F656T and F656M hERG currents and had no effect on their channel gating regardless of their impact on potency of hERG channels blockers (Fernandez et al. 2004), showing that a hERG drug-binding site, Phe656, is crucial for effects of E2 on the hERG channel gating (Fig. 6, Supplemental Fig. 3B and C, Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 6. Importance of a common drug-binding site for the hERG suppression by E2.

HERG currents were recorded from CHO-K1 cells transiently expressing hERG genes as described in the Methods. A, mutagenesis study at two common drug-binding sites located in the S6 domain of the hERG channel. Both Thr-substitution (F656T) and Met-substitution (F656M) at Phe656 abolished the hERG inhibition by E2 (grey bars), which can be seen in wild type (WT) and Ala-substitution at Tyr652 (Y652A). Plots are tail currents normalized to the control currents, the value 10 min before application of E2 (3 nm). Time control values (white bars) were obtained from recordings with the same time protocol in the absence of E2. The numbers of experiments for each construct were as follows: WT, control, n = 4, and E2, n = 10; Y652A, control, n = 5, and E2, n = 10; F656T, control, n = 5, and E2, n = 10; F656M, control, n = 5, and E2, n = 6. *P < 0.05, unpaired t test versus time control. B, representative traces for the wild type, Y652A, F656T and F656M. Traces in the absence (control) or the presence of E2 (E2) are superimposed with traces after the wash-out shown in grey. Scale, 10 pA pF−1, 1 s. The voltage protocol is shown above the traces. Note that application of E2 to WT and Y652A, but not to F656T and F656M, accelerated deactivation.

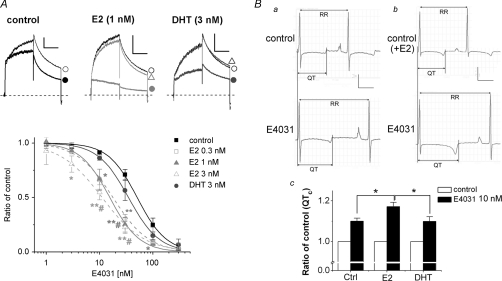

Effects of E2 on sensitivity of a hERG blocker to hERG currents in vitro

As Phe656 in the hERG channel is crucial for the effect of E2, we next tested in HEK293 cells whether E2 modifies the hERG blockade by a selective potent hERG blocker, E4031, whose binding site includes both Tyr652 and Phe656 in the hERG channel (Kamiya et al. 2006). Figure 7A shows that the presence of E2 in the external solution increased significantly the fractional inhibition of hERG currents induced by E4031. The IC50 values in the presence of E2 at 0.3–3 nm show that E2 increased the sensitivity of E4031 by about 3-fold in a moderate dose-dependent manner. However, DHT did not alter the E4031-induced fractional inhibition. Such E2 also enhanced E4031-induced QTC prolongation in Langendorff perfused guinea pig hearts (Fig. 7B, QTC without hormones: control; 275 ± 10 ms, E4031; 302 ± 9 ms, QTC with E2: control; 278 ± 4 ms, E4031; 325 ± 10 ms, QTC with DHT: control; 276 ± 11 ms, E4031; 302 ± 7 ms). These results indicate that E2, but not DHT, enhances the effects of E4031.

Figure 7. Effects of E2 and DHT on sensitivity of E4031 to hERG currents and QTC intervals.

A, inhibition of HERG currents by E4031 (10 nm). HERG currents were recorded from HEK293 cells as described in Fig. 4A. After the current amplitudes were stabilized by application of hormones to the control external solution, E4031 was added in the presence of hormones. Time control was performed with the same protocol, but without including hormones in the external solutions. Representative traces (upper) in the absence (open circles) or in the presence of hormones (E2 or DHT shown in open triangles) are shown by superimposing the traces before (open symbols) and after addition of E4031 (filled circles). Scale, 10 pA pF−1, 1 s. Concentration-dependent curves (lower) were drawn with fits of normalized tail amplitudes relative to the values before application of E4031 for 5 min (see Methods). IC50 values are as follows: time control (filled squares, n = 4–9); 50.6 nm, E2 at 0.3 nm (open squares, n = 3–5); 17.8 nm, E2 at 1 nm (filled triangles, n = 3–7); 15.5 nm, E2 at 3 nm (open triangles, n = 3–5); 11.2 nm, DHT at 3 nm (filled circles, n = 3–6); 34.8 nm*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus time control, #P < 0.05 versus DHT, ANOVA. B, QTC intervals. E2 enhanced the magnitude of E4031 (10 nm) -induced QTC prolongation in Langendorff guinea pig hearts. Shown are representative ECG traces in the absence (a) and the presence (b) of E2 (3 nm). Scale, 0.5 V, 0.2 s. E4031-induced QTC prolongations are summarized in c. QTC intervals of Langendorff guinea pig hearts were obtained as described in Fig. 1A. Control (no hormones); n = 7, E2 at 3 nm; n = 5, DHT at 3 nm; n = 5. *P < 0.05, ANOVA.

Discussion

It is widely accepted that female is more prone to develop drug-induced arrhythmias (TdP) in association with QTC prolongation (Makkar et al. 1993; Lehmann et al. 1996; Drici et al. 1998; James et al. 2007). Even though some clinical reports (Rodriguez et al. 2001; Kadish et al. 2004) and basic investigations concerning genomic actions of sex hormones (Drici et al. 1996; Hara et al. 1998; Pham et al. 2001), the underlying mechanisms for this gender disparity have not been completely clarified. Here it is clear from our experiments that the physiological levels of E2 acutely down-regulates the hERG channel and enhances both the E4031-induced hERG modulation and the E4031-induced QTC prolongation. Such effects of E2 are independent of the oestrogen receptor signalling. Thus, we believe that the receptor-independent effects of E2 provide a novel mechanism for the higher susceptibility to drug-induced arrhythmia in women.

Physiological concentration of E2 varies from 0.1 to 1 nm during the menstrual cycle (< 0.1 nm in men), and E2 rises to as high as several hundred nM during pregnancy (Hulot et al. 2003; Nakagawa et al. 2006; James et al. 2007). Although some previous studies pointed out acute effects of E2 at several micromolar (James et al. 2007), our study firstly described acute effects of physiological concentrations of E2 on cardiac repolarization and cardiac ion channels. E2 truncated cardiac depolarization at several hundreds of nanomolar, which can be observed only at the late phase of pregnancy. Duration of cardiac depolarization was prolonged at 1 nm, which is within the physiological E2 level, and therefore, may have a clinical impact under the basal condition.

The magnitude of the hERG suppression by physiological levels of E2 was relatively small but significant in our experimental condition using charcoal-treated phenol-red free medium and a rapid perfusion system (Kurokawa et al. 2001). Under these strict conditions for experimental methods, we can detect the E2-induced positive shift of the activation which can delay ionic process of cardiac repolarization. Although we showed concentration-dependence of the E2-induced suppression of the hERG currents elicited by +20 mV pulses (Fig. 5B), the change in Imax of the activation was not concentration-dependent suggesting that E2 is not a pore-blocker (Table 1). The hERG suppression at 20 mV calculated from the values of V1/2 and k in Table 1. (1 nm; 10.6%, 3 nm; 13.7% reduction), which accounts for the gating modification, was about 70% of the hERG suppression calculated from the concentration-dependent curve measured by 20 mV pulses in Fig. 5B (1 nm; 15.7%, 3 nm; 20.8% reduction). This comparison suggests that the hERG suppression by E2 is largely due to the slight positive shift of the hERG activation, which is consistent with voltage-dependent suppression of guinea pig IKr tail currents as shown in Fig. 3A. Indeed, the E2-induced subtle hERG suppression appears to be consistent with less clear impact of oestrogen on fluctuation of female baseline QTC intervals during the menstrual cycle (Rodriguez et al. 2001; Hulot et al. 2003; Nakagawa et al. 2006). Actually, our recent publication (Nakamura et al. 2007) suggests that a nongenomic regulation of cardiac ion channels by progesterone has a major impact on fluctuation of female baseline QTC during the menstrual cycle by ∼10 ms, which is consistent with previous clinical reports (Rodriguez et al. 2001; Hulot et al. 2003; Nakagawa et al. 2006). Very slight, but significant, QTC prolongation by a few milliseconds with only oestrogen-replacement menopausal therapy (Kadish et al. 2004) seems to agree with the slight hERG modulation. Further studies such as simulation studies can be a clue to understand the functional consequences of the slight hERG modification. Possibly, the E2-indused sensitization of the hERG channel to E4031 (Figs 6 and 7) could have lager impact on risks of drug-induced TdP in women than the slight modification of hERG itself. Indeed, in consistent with our study, Hara et al. (Hara et al. 1998) found that chronic treatment of E2 emphasized E4031-induced APD prolongation and EAD incidence/magnitude in rabbit papillary muscle, whereas Pham et al. (Pham et al. 2001) showed that serum E2 levels were unrelated to the effects of dofetilide, rather influenced by testosterone, implying that the influence of sex hormones on the hERG blocker-sensitivity may be specific to each drug. In contrast to the dramatic emphasis of E4031-induced APD prolongation with chronic treatment of E2, the chronic treatment of E2 did not affect the baseline electrocardiographic characteristics in rabbits, suggesting that the chronic E2 treatment reduced the repolarization reserve (Hara et al. 1998). These chronic effects of E2 are involved in transcriptional regulation of message levels of some K+ channels but not the hERG channel (Drici et al. 1996). Although it is hard to discuss the relative impact of transcriptional versus acute effects on cardiac repolarization because of not only the different target channels but also wide interspecies variance of transcriptional regulation of cardiac ion channels induced by oestrogen (Drici et al. 1996; Fulop et al. 2006), the clearly significant influence of chronic and/or acute E2 treatment on E4031-induced QTC prolongation indicate that both transcriptional and acute effects of E2 can enhance the sensitivity of E4031 to QTC prolongation, possibly leading to acquired TdP.

A major finding in this paper is that IKr inhibition by E2 is independent of oestrogen receptors in contrast to a receptor-dependent nongenomic regulation of IKs and ICa,L (Bai et al. 2005). The receptor-independent regulation is supported by our results that an oestrogen receptor antagonist, ICI182,780, did not recover E2-induced IKr inhibition and that E2 suppressed the hERG currents in HEK293 or CHO-K1 cells which have no oestrogen receptor. Actually, other receptor-independent effect of oestrogen have been reported including direct binding of E2 to the β-subunit of the BK channel (Valverde et al. 1999), which shows the importance of receptor-independent effects of sex-steroids.

Our site-directed mutagenesis study demonstrated that a common drug-binding site, Phe656, plays a crucial role in the hERG suppression by E2. Although it has been shown that π-stacking between the aromatic side chain of Phe656 and aromatic rings of the hERG blockers is required for high affinity binding and channel block (Mitcheson et al. 2000), the important physicochemical feature of Phe656 for most of hERG blockers seems to be hydrophobic volume, not aromaticity per se (Fernandez et al. 2004). The disruption of the E2 effect by F656M mutation (Fig. 6C) shows that hydrophobic volume is not required for the effect of E2 unlike the hERG blockers, and suggests that aromaticity of Phe656 is important for the hERG suppression by E2. This suggests that the aromatic centroid of E2, which does not exist in DHT, may be responsible for modulating the hERG channel. When we consider that Phe656 is also an E4031-binding site (Kamiya et al. 2006), it is intriguing that E2 augments the hERG blockade by E4031, rather than attenuates by displacement of E4031-binding at Phe656. It may be possible that interaction of E2 with Phe656 does not share the E4031 binding site can allosterically facilitate the E4031 binding, It is also possible that allosteric interactions of E2 with the hERG channel other than Phe656 can modify the functional consequence of the E4031 binding through Phe656. Such increment of the sensitivity of E4031 was not a simple additive effect caused by additional hERG suppression by E2, because E2 significantly enhanced the sensitivity even when the fractional hERG inhibition and QTC prolongation were determined by normalizing them relative to the values before application of E4031 in the presence of E2 (Fig. 7). Although the mechanism has not been clarified, E2 enhances the hERG suppression in line with the greater ibutilide-induced QTC prolongation in the late follicular phase (Rodriguez et al. 2001) which could underlie the enhanced susceptibility of women to acquired long QT syndrome (Makkar et al. 1993; Lehmann et al. 1996; Drici et al. 1998; James et al. 2007).

In summary, we demonstrate that E2 modifies kinetics of the hERG channel gating and enhances drug-induced prolongation of APD and QTC interval. This regulation may play a critical role in the gender-difference in drug-induced QTC prolongation, and dynamic alterations of the risk of drug-induced TdP during the menstrual cycle in females.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr A. Kaihara and Dr T. Sasano for helpful comments, Dr C. E. Clancy (Cornell University) for help with the manuscript, and Ms S. Kakusaka and Ms E. Kurobane for collecting data, and Ms E. Ozaki for her technical assistance. This work was supported in parts by the Grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, Sports and Technology of Japan (19689006 to J.K., 18390231 to T.F.), and Grant-in Aid for scientific Research on Priority Areas (17081007 to T.F.), and research grants (to J.K.) from the Astellas Foundation, the Uehara Memorial Foundation and the Naito Foundation. There is no disclosure on this study.

Supplementary material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at: http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2007.150367/DC1 and http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/suppl/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150367

References

- Abi-Gerges N, Philp K, Pollard C, Wakefield I, Hammond TG, Valentin JP. Sex differences in ventricular repolarization: from cardiac electrophysiology to Torsades de Pointes. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2004;18:139–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai CX, Kurokawa J, Tamagawa M, Nakaya H, Furukawa T. Nontranscriptional regulation of cardiac repolarization currents by testosterone. Circulation. 2005;112:1701–1710. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.523217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazett HC. The time relations of the blood-pressure changes after excision of the adrenal glands, with some observations on blood volume changes. J Physiol. 1920;53:320–339. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1920.sp001881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy CE, Kurokawa J, Tateyama M, Wehrens XH, Kass RS. K+ channel structure-activity relationships and mechanisms of drug-induced QT prolongation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:441–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drici MD, Burklow TR, Haridasse V, Glazer RI, Woosley RL. Sex hormones prolong the QT interval and downregulate potassium channel expression in the rabbit heart. Circulation. 1996;94:1471–1474. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drici MD, Knollmann BC, Wang WX, Woosley RL. Cardiac actions of erythromycin: influence of female sex. JAMA. 1998;280:1774–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez D, Ghanta A, Kauffman GW, Sanguinetti MC. Physicochemical features of the HERG channel drug binding site. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10120–10127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay GA, York B, Karas RH, Fanburg BL, Zhang H, Kwiatkowski DJ, Noonan DJ. Estrogen-induced smooth muscle cell growth is regulated by tuberin and associated with altered activation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β and ERK-1/2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23114–23122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulop L, Banyasz T, Szabo G, Toth IB, Biro T, Lorincz I, Balogh A, Peto K, Miko I, Nanasi PP. Effects of sex hormones on ECG parameters and expression of cardiac ion channels in dogs. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2006;188:163–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M, Danilo P, Jr, Rosen MR. Effects of gonadal steroids on ventricular repolarization and on the response to E4031. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:1068–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulot J-S, Demolis J-L, Riviere R, Strabach S, Christin-Maitre S, Funck-Brentano C. Influence of endogenous oestrogens on QT interval duration. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1663–1667. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AF, Choisy SC, Hancox JC. Recent advances in understanding sex differences in cardiac repolarization. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:265–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadish AH, Greenland P, Limacher MC, Frishman WH, Daugherty SA, Schwartz JB. Estrogen and progestin use and the QT interval in postmenopausal women. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2004;9:366–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2004.94580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya K, Niwa R, Mitcheson JS, Sanguinetti MC. Molecular determinants of hERG channel block. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1709–1716. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.020990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko CM, Ducic I, Fan J, Shuba YM, Morad M. Suppression of mammalian K+ channel family by ebastine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:233–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa J, Chen L, Kass RS. Requirement of subunit expression for cAMP-mediated regulation of a heart potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2122–2127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434935100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa J, Motoike HK, Kass RS. TEA+-sensitive KCNQ1 constructs reveal pore-independent access to KCNE1 in assembled IKs channels. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:43–52. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann MH, Hardy S, Archibald D, Quart B, MacNeil DJ. Sex difference in risk of torsade de pointes with d,1-sotalol. Circulation. 1996;94:2535–2541. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.10.2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makkar RR, Fromm BS, Steinman RT, Meissner MD, Lehmann MH. Female gender as a risk factor for torsades de pointes associated with cardiovascular drugs. JAMA. 1993;270:2590–2597. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.21.2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitcheson JS, Chen J, Lin M, Culberson C, Sanguinetti MC. A structural basis for drug-induced long QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12329–12333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210244497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Ooie T, Takahashi N, Taniguchi Y, Anan F, Yonemochi H, Saikawa T. Influence of menstrual cycle on QT interval dynamics. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:607–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H, Kurokawa J, Bai CX, Asada K, Xu J, Oren RV, Zhu ZI, Clancy CE, Isobe M, Furukawa T. Progesterone regulates cardiac repolarization through a nongenomic pathway: an in vitro patch-clamp and computational modeling study. Circulation. 2007;116:2913–2922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.702407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TV, Sosunov EA, Gainullin RZ, Danilo P, Jr, Rosen MR. Impact of sex and gonadal steroids on prolongation of ventricular repolarization and arrhythmias induced by IK-blocking drugs. Circulation. 2001;103:2207–2212. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.17.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razandi M, Pedram A, Greene GL, Levin ER. Cell membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) originate from a single transcript: studies of ERα and ERβ expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:307–319. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez I, Kilborn MJ, Liu XK, Pezzullo JC, Woosley RL. Drug-induced QT prolongation in women during the menstrual cycle. JAMA. 2001;285:1322–1326. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.10.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Xu QP. Mutations of the S4–S5 linker alter activation properties of HERG potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1999;514:667–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.667ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde MA, Rojas P, Amigo J, Cosmelli D, Orio P, Bahamonde MI, Mann GE, Vergara C, Latorre R. Acute activation of Maxi-K channels (hSlo) by estradiol binding to the β subunit. Science. 1999;285:1929–1931. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LM, Orikabe M, Hirano Y, Kawano S, Hiraoka M. Effects of Na+ channel blocker, pilsicainide, on HERG current expressed in HEK-293 cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;42:410–418. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200309000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.