Abstract

Numerous studies have shown sex and/or estrous cycle differences in the acoustic startle reflex (ASR) and its prepulse inhibition (PPI) in humans and animals. However, few have examined the effects of hormone manipulations on these behaviors. This study paired gonadectomy (GDX) in adult male rats with testing for ASR and PPI at 2, 4, 9, 16, 23, 30 and 37 days after surgery. Initial studies of control, GDX and GDX rats given testosterone propionate revealed no group differences in PPI, but did reveal phasic facilitation of the ASR in GDX rats that was greatest on the first and final testing sessions and that was attenuated by testosterone. A second study addressing roles for estrogen and androgen signaling tested new control and GDX rats along with GDX rats given estradiol or the non-aromatizable androgen, 5-alpha-dihydrotestosterone and revealed no group differences in PPI, and increases in ASR in GDX rats that were largest during the first and final testing sessions and that were attenuated by both hormone replacements. However, while responses in GDX rats given testosterone were similar to those of controls, ASR in estradiol- and to a lesser extent in dihydrotestosterone-treated GDX rats were typically lower than in controls. This may suggest that hormone modulation of the ASR requires synergistic estrogen and androgen actions. In the male brain where this can be achieved by local steroid metabolism, the enzymes responsible, e.g., aromatase, could help identify loci in the startle circuitry that may be especially relevant for the hormone modulation observed.

Keywords: aromatase, prepulse inhibition, sensorimotor gating, estrogen, androgen

Numerous studies that have measured the acoustic startle reflex (ASR) and/or its prepulse inhibition (PPI) in humans, human patient populations and laboratory animals [1,2,3,4] have made clear that the ASR, the short-latency, whole body motor reflex elicited in response to a brief, intense acoustic pulse [5], and its PPI, operationally defined as the decrease in the ASR that occurs when the pulse stimulus is preceded by a weaker tone [6,7,8] reflect elements of behavior that are mediated by different brain regions and circuits [4,5,9 and that are in some cases influenced by different sets of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators [10]. Recent evidence suggests, however, that both may be sensitive to gonadal hormones. For example, in rats both the startle reflex and its PPI have been shown to be larger in males than in females [11, 12. 13. 14. 15], and studies in female rats (but not mice [16] ) have shown that although the ASR is similar at all phases of the estrous cycle, PPI values are significantly lower during proestrus compared to estrus or diestrus [14].

Sex differences and/or differences across the menstrual cycle in ASR and/or PPI have also been identified in healthy human subjects. For example, electromyographic studies have identified decreased probabilities of occurrence and lower magnitudes of ASR in adult males compared to females [17], while studies of prepulse inhibition have shown these responses to be significantly lower in women than in men [18], and decreased in women during luteal compared to follicular phases of the estrous cycle [19, 20]. In addition, deficits in PPI and in some cases ASR have also been shown to occur in disorders including schizophrenia and ADHD in sex specific manners [2, 21, 22]. For example, decreased PPI has been identified in male but not female schizophrenics compared to same sex, healthy subjects [18], while following light exercise, girls with ADHD have been shown to have increased eye blink responses to acoustic startle compared to ADHD boys and control subjects of both sexes [23]. Deficits in PPI have also been observed in autism [24], and in Tourette’s, fragile X and Asperger’s syndromes [4, 21, 25, 26] which are all disorders that disproportionately afflict males.

While sex and/or estrous cycle differences identified for ASR and PPI in animals and in humans provide strong correlative evidence for gonadal hormone modulation of these behaviors, it is difficult to draw a consensus view from this information about precisely how gonadal steroids may be acting on these behaviors. Further, there are surprisingly few studies that have used experimental means to directly examine gonadal hormone impact on ASR and/or PPI. In fact, these are currently limited to two studies in ovariectomized female rats and one study that evaluated gonadectomized male and ovariectomized female rats [27, 28, 29]. Revealing the nature of hormone influence on ASR and PPI is important, however, for further defining the neurobiology of these discrete behavioral processes, for perhaps providing insights into the neuropathology of those disorders where sex-specific failures in ASR and PPI are among key clinical features, and for further defining roles for gonadal steroids in the CNS beyond neuroendocrine and reproductive axes. Accordingly, the studies presented here used gonadectomy and hormone replacement in adult male rats to continue to gather fundamental information about hormone stimulation of ASR and PPI in males, the sex for which epidemiological data suggest that compromise of these behavior measures in human nervous system disorders is especially prevalent. In view of previous evidence from this laboratory showing selective and dynamic effects of gonadectomy in adult male rats on prefrontal DA innervation [30, 31] and the evidence from others showing that changes in this innervation can potently modulate PPI [32, 33, 34, 35, 36], there was also a specific impetus to examine behavior over a timeline when the complex effects of gonadectomy on the prefrontal DA system are known to be taking place. Accordingly, ASR and PPI were measured and re-measured from two days to five weeks after surgery, initially in sham-operated, gonadally intact control animals, gonadectomized rats and gonadectomized rats supplemented with testosterone propionate. As presented below, findings of hormone sensitivity identified in these first analyses prompted a second evaluation in which behavioral testing was repeated in new cohorts of control and gonadectomized rats along side gonadectomized rats supplemented with estradiol or with the non-aromatizable androgen 5α-dihydrotestosterone to identify the hormone or hormones involved in the modulation observed.

METHODS

Subjects

Fifty-six adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were used (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY). All procedures involving animals (below) are approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Stony Brook University and are designed to minimize their discomfort and use. All animals were housed with food and water freely available under a 12 h light/dark cycle.

Rats were divided between two experiments. In the first there were three treatment groups: eight rats that were sham operated (CTRL), eight that were gonadectomized (GDX), and eight that were gonadectomized and supplemented with testosterone propionate (GDX-TP). The second experiment included four treatment groups. In addition to new cohorts of CTRL and GDX animals (n=8 each), there were eight GDX rats that were supplemented with estradiol (GDX-E), and eight GDX rats that were given 5α-dihydrotestosterone (GDX-DHT). All animals weighed between 250 and 270 g at the start of the experiment, and body weight was monitored throughout the course of both studies.

Surgical Procedures

Gonadectomies and sham surgeries were performed under aseptic conditions. Anesthesia consisted of intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). For all surgeries, the sac of the scrotum and underlying tunica were incised, and for GDX the vas deferens was bilaterally ligated and the testes were removed. Prior to suturing (6.0 silk sutures), the GDX-TP, GDX-E and GDX-DHT rats were implanted with 60 day slow-release pellets of TP, E or DHT in a biodegradable matrix (cholesterol, microcrystalline cellulose, alpha-lactose, di- and tri-calcium phosphate, calcium and magnesium stearate and stearic acid; Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL). Previous studies in this laboratory using these same pellets have shown that they release roughly 0.5–10 ng of TP, 10–60 pg E and 0.5–5 ng DHT per milliliter of blood per day, respectively, and that all produce circulating hormone levels that fall within physiological ranges [30, 37, 38, 39].

Note

All of the animal subjects of this study were maintained under surgical anesthesia for comparable periods of time and all showed comparable rates and courses of recovery as evinced by the initiation of head and limb movements and ultimately independent locomotion during the first few hours after surgery and the lack of any obvious signs of discomfort, dehydration or loss of appetite when examined 24 hours after the procedure.

Behavioral Testing

Rats were tested in a cylindrical, perforated Plexiglas chamber (3” diameter, 11.5” long) that was attached to the floor plate of a sound-attenuated, lit, and ventilated Plexiglas testing box. Piezoelectric discs located beneath the floor plate detected and transduced the mechanical force/acceleration produced by the rats’ motor responses to acoustic stimuli (below). Prior to each testing session, a 5 g weight was dropped from a standardized height onto the floor plate to measure the mechanical sensitivity/response of the apparatus to assure consistency from session to session.

Acoustic Stimuli

Auditory stimuli were generated using a precision signal generator (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) interfaced with a Pulsemaster A300 (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) and an amplifier, and were delivered through speakers mounted on one of the testing chamber walls. The stimuli consisted of either a single 100 dB pulse or this same pulse preceded by 100 ms by a 70 dB prepulse (~10 dB above background). Prior to each testing session, the decibel levels of all auditory stimuli and background noise were measured inside the testing box to ensure comparability across testing days.

Testing Paradigm

Testing took place during the animals’ subjective night in the repeated order of a CTRL, a GDX, and a GDX-TP rat in the first experiment, and a CTRL, GDX, GDX-E and GDX-DHT rat in the second experiment. Each testing session consisted of 10 pulse only trials interleaved in random order with 10 prepulse/pulse that were separated by inter-trial intervals that varied randomly between 20 and 40 seconds. For each trial, motor activity was measured for a total of 500 ms (200 ms before, and 300 after the stimulus). For both sets of studies, testing took place 2, 4, 9, 16, 23, 30 and 37 days after surgery.

Quantitative Analyses

Motor responses to each trial were quantified over a 140 ms epoch beginning at stimulus onset; 1 EMG Analysis Software (kindly provided by Dr. L. Craig Evinger, Stony Brook University) was used to measure the animal’s total transduced vertical movement during that time window. Responses made during pulse and prepulse trials were evaluated separately and were also averaged on a subject-by-subject basis to compute values of PPI using the following formula:

In the second experiment, the GDX-E group was found to weigh significantly less than the other three groups. To adjust for this, all of the animals’ body weights in this study were normalized to the mean value of the control group for that day, and all motor responses were multiplied by this correction factor. This elevated the magnitudes of the motor responses recorded for the GDX-E group on all but testing day two by between 22 and 32%, and raised motor response amplitudes in the remaining groups and for the GDX-E group on day 2by 0–5%. Importantly, however, this normalization had no effect on any of the overall or statistical conclusions drawn from the study. There were no significant group differences in body weight among the animals of the first experiment; the motor responses presented for these animals are not corrected.

Euthanasia

Following behavioral testing, rats were deeply anesthetized with an i.p. injection of ketamine (150 mg/kg) and xylazine (50 mg/kg), and were checked for corneal and other deep reflexes. Once these disappeared, the chest cavities were opened, a 2 ml sample of trunk blood was collected, the heart was injected with 0.2ml heparin, and animals were transcardially perfused with a flush of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), followed by 800 ml of 2% paraformaldehyde and 15% picric acid in 0.1 M PB. Following fixation, the medial, ventral, and lateral bulbospongiosus muscle (BSM) were dissected out and weighed.

ELISA Assay of Serum Hormone Levels

Blood samples collected at the time of euthanasia sat in open microcentrifuge tubes for 15–20 minutes at room temperature to allow coagulation. These samples were then centrifuged (6,000rpm, 15 minutes) and the serum was collected and snap frozen in powdered dry ice, and stored at –80 C prior to direct solid phase immunoassay to measure testosterone, 5-α DHT, and estradiol (Testosterone EIA; Dihydrotestosterone EIA; Estradiol EIA, American Laboratory Products Co., Ltd., Windham, NH).

Statistics

Body and BSM weights were compared across treatment groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with hormone treatment as the main factor (Statview 5.0). Data from individual ASR and prepulse trials, as well as mean ASR and prepulse values and derived measures of PPI were also analyzed across all testing days using ANOVAs with repeated measures designs; main effects of hormone treatment, sessions, and sessions by treatment interactions were evaluated. For all analyses, post-hoc testing used the Fisher’s PLSD test, a p < 0.05 level was accepted as significant, and a p < 0.09 level was used as the cut-off to define group differences that approached significance.

Note

On testing day 37 in the first experiment, behavioral responses of all animals during the prepulse trials were inexplicably high and close in magnitude to those recorded during pulse alone trials. The PPI values calculated for that day, and that day only, were all less than 20%, and more than two standard deviations away from mean PPI values measured on all other testing days for both studies. Accordingly, these outlying data were excluded from analysis and are not shown here. In the second experiment, data from one control, one GDX-DHT and two GDX rats were also removed from all analyses based on the criteria that each individual showed little to no response to any acoustic stimuli (pulse and prepulse) presented during three or more of the seven testing sessions.

RESULTS

Efficacy of Hormone Treatments

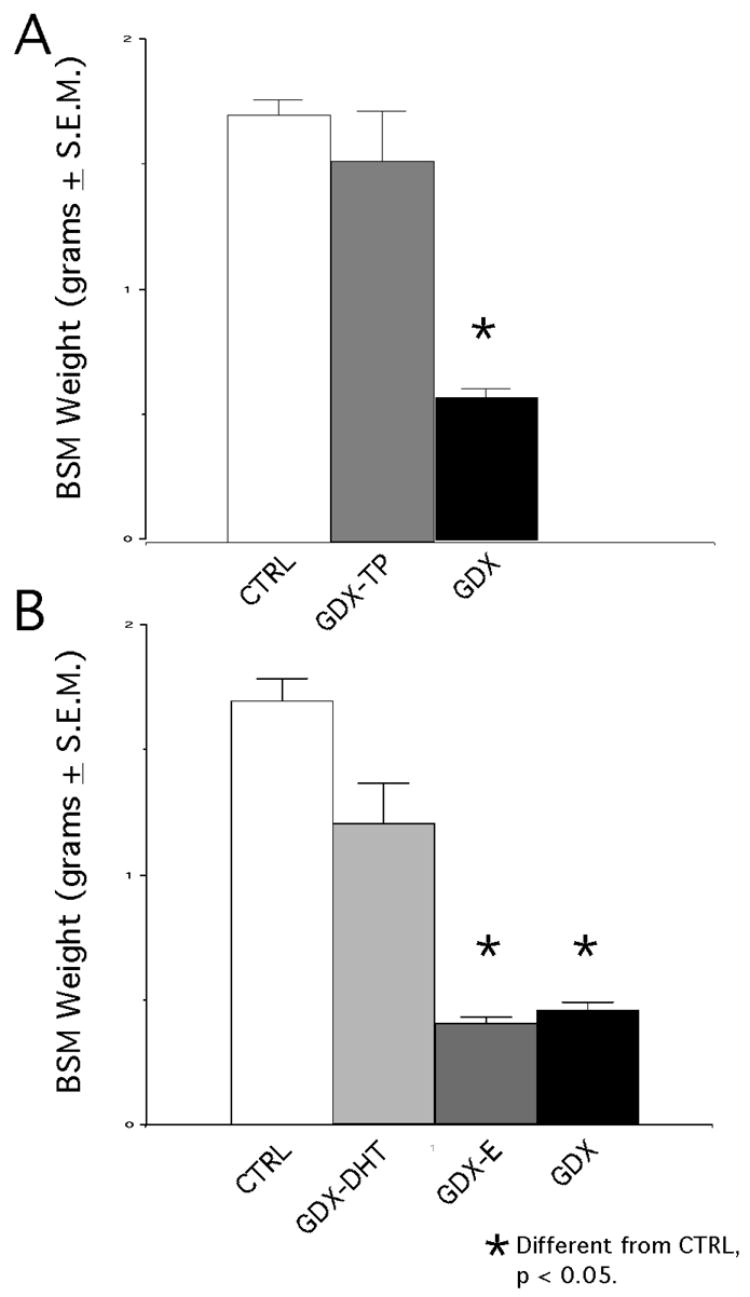

The effectiveness of the hormone manipulations used in this study was assessed by statistically comparing the weights of the animals’ androgen-sensitive bulbospongiosus muscles (BSM, [40]) and by using direct solid phase immunoassays (ELISAs) to measure circulating levels of testosterone, estradiol and/or 5a DHT in serum samples collected from the animal subjects at the time of euthanasia. Separate analyses of variance compared BSM weights across animals in the groups tested in the two studies. Both revealed significant main effects of hormone treatment on BSM weight (Expt. 1, F (2, 21) = 24.04, p<0.0001; Expt. 2, F (3, 21) = 54.02, p < 0.0001), and subsequent post hoc testing revealed that for the first study, average BSM weights were significantly higher in the control and GDX-TP rats compared to the GDX animals (Fig. 1A), and that in the second BSM weights in the control and GDX-DHT cohorts were significantly higher than those of the GDX and GDX-E groups (Fig. 1B). Immunoassays of serum from trunk blood samples further revealed that circulating levels of TP, E and 5-αDHT were all reduced in the GDX compared to control groups, and that levels of estradiol in the GDX-E animals and testosterone (T) in the GDX-TP cohort were similar to hormone levels measured in the gonadally intact animals (Table 1). In the GDX-DHT animals, however, blood levels of DHT were lower than expected (Table 1). In contrast to previous studies in this lab using these same pellets [30, 39] and to what was anticipated based on the sparing of the androgen-sensitive BSM in these animals, DHT levels measured in the GDX-DHT group were closer to values from the GDX rats compared to the controls. The blood samples collected were not of sufficient volume to re-run the assay. Thus, it remains unknown why the measured levels of DHT were at odds with other indicators, e.g., BSM weight, body weight, showing that these animals had experienced substantial androgen exposure.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs showing mean group weights in grams (±SEM) of the bulbospongiosus muscles (BSM) dissected from each animal subject at the time of euthanasia. In A, mean BSM weights from the 8 control (CTRL), 8 gonadectomized (GDX) and 8 gonadectomized rats supplemented with testosterone propionate (GDX-TP) tested in the first series of experiments are shown. Among these groups, BSM weights were significantly lower (asterisk) in GDX rats compared to the CTRL and GDX-TP groups. In B, mean BSM weights in a second group of 8 CTRL and 8 GDX rats appear with weights of 8 gonadectomized rats supplemented with estradiol (GDX-E) and 8 with 5α-dihydrotestosterone (GDX-DHT); among these, weights in the GDX and GDX-E groups were significantly lower (asterisks) than those in the CRTL and GDX-DHT groups.

Table 1.

| EXPERIMENT 1 | TESTOSTERONE | ESTRADIOL | DIHYDROTESTOSERONE |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | 12254.90 ± 3180.56 | 100.18 ± 25.02 | 803.65 ± 429.25 |

| GDX | 3077.72 ± 734.73 | 76.17 ± 15.7 | 20.88 ± 5.52 |

| GDX-TP | 8494.31 ± 1720 | 89.43 ± 12.24 | 13.39 ± 1.84 |

|

| |||

| EXPERIMENT 2 | TESTOSTERONE | ESTRADIOL | DIHYDROTESTOSERONE |

|

| |||

| CTRL | 12151.73 ± 3815.37 | 103.24 ± 25.62 | 876.34 ± 464.23 |

| GDX | 3116.34 ± 758.45 | 79.25 ± 17.01 | 17.63 ± 04.61 |

| GDX-DHT | 4801.07 ± 1754.21 | _ _ _ | 11.35 ± 1.82 |

| GDX-E | _ _ _ | 91.55 ± 12.73 | _ _ _ |

Mean circulating levels of testosterone, estradiol and 5α-dihydrotestosterone measured in ELISA assays from blood samples collected at the time of euthanasia.

Values obtained in the control (CTRL), gonadectomized rats (GDX) and gonadectomized animals supplemented with testosterone propionate (GDX-TP), dihydrotestosterone (GDX-DHT) and estradiol (GDX-E) tested in the two experiments presented here are shown. All values are expressed in nanograms/ml of blood; means ± SEM are shown.

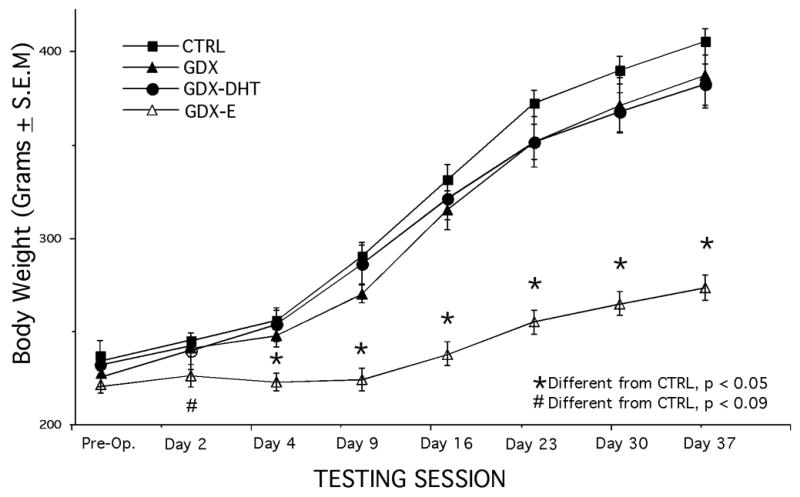

Effects of hormone treatments on body weight

For the CTRL, GDX, and GDX-TP rats from the first experiment, weight measurements that were taken at the beginning of the study, periodically throughout its course, and at its conclusion revealed no group differences, and statistical analyses (ANOVAs) confirmed that among these subjects, there were no significant main effects of hormone treatment on body mass for any of the time points evaluated. For the CTRL, GDX, GDX-DHT, and GDX-E groups from the second experiment, measurements of body weight taken prior to each testing session revealed consistently lighter weights in the GDX-E rats compared to all other groups. Analyses of variance confirmed that there were significant main effects of hormone treatment on body weight (F ( 3, 21) = 29.58, p < 0.0001), and post-hoc testing showed that the weights of the GDX-E rats were significantly or nearly significantly lower than those measured in the control, GDX, and GDX-DHT rats on all testing days (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Line plots showing mean body weights (±SEM) of the control (CTRL), gonadectomized (GDX), and gonadectomized rats supplemented with 5α-dihydrotestosterone (GDX-DHT) or estradiol (GDX-E) measured immediately prior to sham-surgery or gonadectomy (Pre-Op.) and prior to each of the seven testing sessions (X-axis) in the second experiment. Body weights were similar in the CTRL, GDX and GDX-DHT groups on all testing days. However, weights in the GDX-E group were significantly different (asterisks) or nearly significantly different (pound sign) from CTRL on all testing days. The motor responses recorded from all of animal subjects in this experiment were adjusted using a correction factor that normalized each animal’s weight to the mean weight of the CTRL group measured on that day.

Effects of Hormone Treatment on Behavioral Testing

Both experiments involved behavioral testing of animals 2, 4 and 9 days after sham surgery or GDX, and from then on weekly for four additional sessions. Prior to each testing session, the decibel levels of background noise and pulse and prepulse stimuli, and the mechanical sensitivity of the chamber were measured (Methods); each measure was similar on every testing day, and ANOVAs with repeated measures designs found no significant variation among these variables across the testing periods. For the testing itself, animals’ responses to 10 pulse and 10 prepulse/pulse stimuli were evaluated. The effects of hormone treatment on these responses, on mean responses from pulse and from prepulse trials, and on PPI were all statistically compared, first using repeated measures ANOVAs that assessed performance measures across the 5-week testing periods. Findings of significant main effects of hormone treatment were followed by post-hoc assessments that highlighted session-by-session differences in performance among and within the treatment groups.

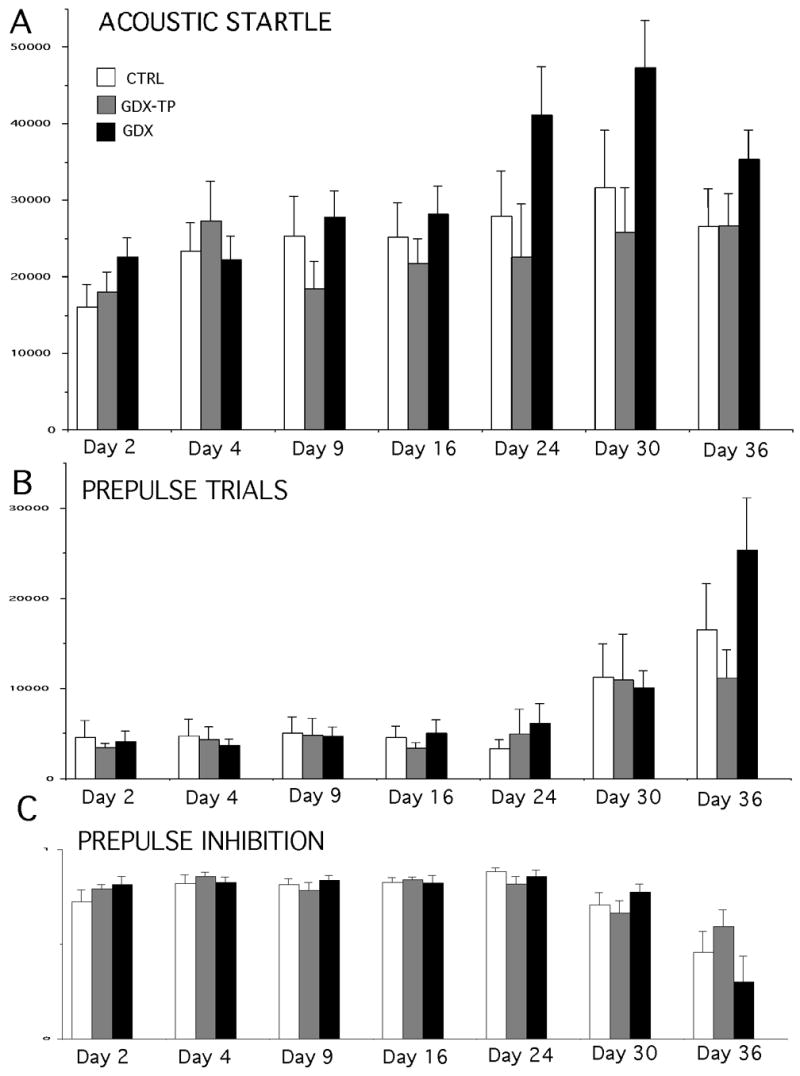

Experiment 1: CTRL vs. GDX vs. GDX-TP Rats

ASR

All treatment groups showed a modest, incremental increase in startle response amplitude over time that was presumed to be a function of increasing body mass. However, the ASR amplitudes of the GDX group were almost always higher than those of the CTRL group, and were most markedly so on the first and final few testing sessions (Fig. 3A). Thus, on the first day of testing (day 2) and over the final three sessions, (days 23, 30, and 37) the responses in the GDX group were 30 to 50% higher than the control and GDX-TP responses, whereas during intervening sessions (testing days 4, 9 and 16) group differences were either absent (day 4) or were comparatively small (on average less than 15%, see Fig. 3A). In contrast, the motor responses made by the CTRL and GDX-TP groups were similar to each other and with few exceptions differed from one another by more than 10% (Fig. 3A). A repeated measures ANOVA that compared mean ASR responses across testing sessions revealed no significant main effects of hormone treatment, but did reveal significant interactions between hormone treatment and testing [F(12, 126) = 2.319, p < 0.013]. Subsequent post hoc comparisons confirmed that there were no significant or near-significant differences between the CTRL and GDX-TP groups on any day and that there were no significant or near significant differences among the responses of the CTRL, GDX and GDX-TP groups on testing days 4, 9 or 16. However, response differences between GDX and CTRL rats approached significance on days 2 (p < 0.09) and 30 (p < 0.08), and differences between GDX and GDX-TP rats were or approached significance on testing days 23 (p < 0.08), 30 (p < 0.04) and 37 (p < 0.09).

Figure 3.

Bar graphs showing group mean (±SEM) responses during acoustic startle trials (A) and mean calculated group mean measures of prepulse inhibition (B) in control (CTRL white bars), gonadectomized (GDX, black bars) and gonadectomized rats given testosterone propionate (GDX-TP, gray bars). Values from testing that took place 2,4, 9, 16, 23, 30 and 37 days after sham surgery or GDX are shown (X-axes). Asterisks identify values that are significantly different from CTRL (p < 0.05), pound signs represent values where differences from the CTRL group approached significance (p < 0.09), ‘1’ marks values that are significantly different from GDX-TP, and ‘2’ represents values where differences from GDX-TP approach significance. Note that prepulse inhibition data from day 37 was aberrantly low (less than 20%) and was removed from the analysis.

PPI

Measures of prepulse inhibition for all animals were consistently between 70 and 80% (Fig. 3B). There was no obvious variation in this parameter across animal groups or testing days. This was supported in a repeated measures ANOVA that identified no significant main effects of hormone treatment and no significant interactions between hormone treatment and testing session on this measure.

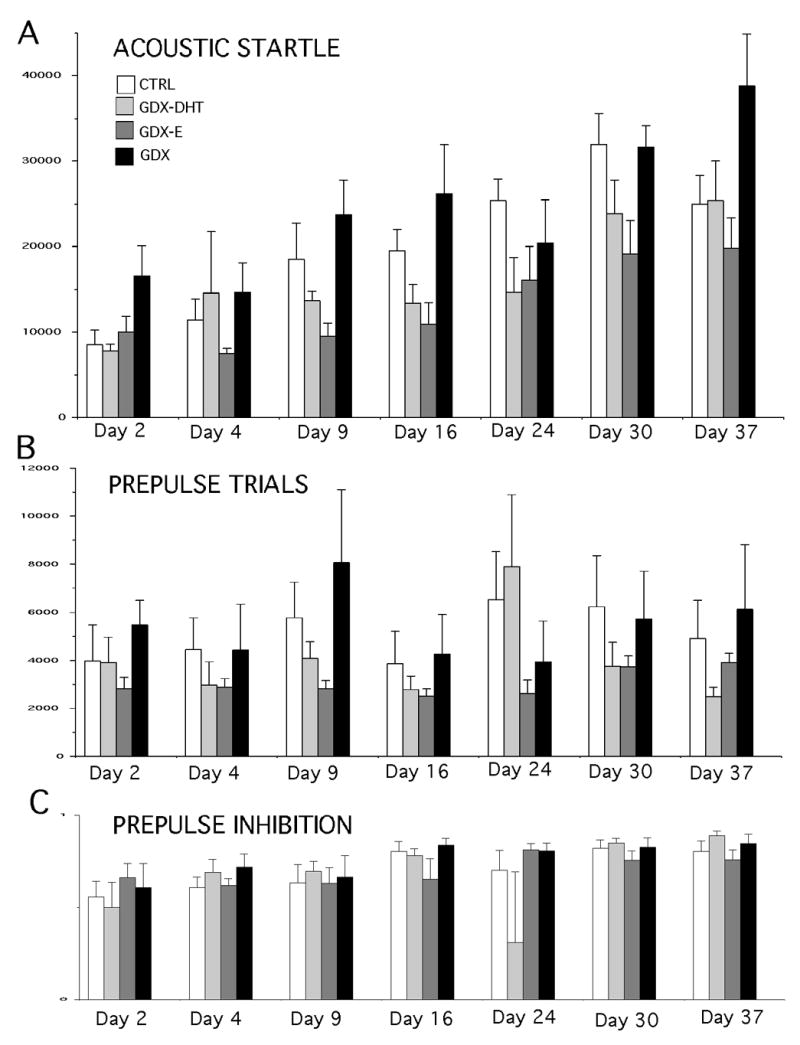

Experiment 2: CTRL vs. GDX vs. GDX-DHT vs. GDX-E Rats

ASR

In the second experiment, behavioral testing was repeated in new groups of control and GDX rats as well as GDX rats in which hormone replacement using E or the non-aromatizable androgen DHT was substituted for TP. Because the GDX-E group weighed significantly less than the other three (Fig. 2), a correction factor that normalized weights across animals was applied to all motor responses recorded from each animal subject. This factor increased the magnitude of the ASR responses in the GDX-E group by between 22 and 32%, but had no significant effect on the responses measured in the other groups, nor in the statistical evaluations on the data.

Similar to what was observed in the first experiment, the ASR in the GDX group was typically higher than controls, especially on the first and final days of testing, when group differences reached 40 to 50% (Fig. 4A). The ASR responses in GDX rats replaced with DHT and especially with E, on the other hand, were similar to controls during some sessions but were lower than the sham-operated control group during others (Fig. 4A). For the GDX-DHT group, ASR values were similar to controls for three of the seven sessions, but were 15–30% lower than controls on testing days 9–30. In contrast, for the GDX-E animals, startle responses were 30 to nearly 50% lower than control on all but the first testing sessions (Fig. 4A). A repeated measures ANOVA that included all of the data from all testing days identified significant main effects of hormone treatment (F (3, 21) =4.37, p < 0.0154) on the ASR, although interactions between hormone treatment and testing session on this measure were not significant. Subsequent post-hoc testing showed that among the hormone replacement groups, differences between the control and GDX-DHT animals approached significance on day 23 (p < 0.085), and that differences between the GDX-E and controls were or approached significance on testing days 9 (p < 0.053), 23 (p < 0.0345) and 30 (p < 0.0201). Analyses of the GDX group revealed differences from the control and GDX-DHT groups that approached or reached significance on both the first and the last day of testing (day 2, p < 0.059 vs. CTRL, p < 0.031 vs. GDX-DHT; day 37, p < 0.070 vs. CTRL, p < 0.09 vs. GDX-DHT), as well as differences between the GDX-E group that were significant on all but days 4 and 23 (day 2 p < 0.039; day 9, p < 0.0071; day 16, p < 0.0119, day 30, p < 0.0141; day 37, p < 0.0076).

Figure 4.

Bar graphs showing group mean (±SEM) responses during acoustic startle trials (A) and calculated group mean measures of prepulse inhibition (B) in control (CTRL white bars), gonadectomized (GDX, black bars), gonadectomized rats given 5α-dihydrotestosterone (GDX-DHT, light gray bars) and gonadectomized rats givenestradiol (GDX-E, dark gray bars). Values from testing that took place 2,4, 9, 16, 23, 30 and 37 days after sham surgery or GDX are shown (X-axes). Asterisks identify values that are significantly different from CTRL (p < 0.05), pound signs represent values where differences from the CTRL group approached significance (p < 0.09), ‘1’ marks values that are significantly different from GDX-DHT , ‘2’ represents values where differences from GDX-DHT approach significance, and ‘3’ identifies values that are significantly different from GDX-E.

PPI

As observed in the previous groups of animals, measures of PPI ranged between 65 and 80%, and were highly consistent from group to group and from day to day (Fig. 4B). The single exception was a decrease in PPI observed in the GDX-DHT group on day 23 that was a consequence of aberrantly strong responses of a single animal subject during the prepulse trials on that day. Regardless of whether this subject was included or removed from the analysis, repeated measures ANOVAs that included all measures of PPI from all testing days identified no significant or near-significant main effects of hormone treatment and no significant or near-significant interactions between hormone treatment and testing session on this measure.

DISCUSSION

The acoustic startle reflex and its prepulse inhibition are naturally occurring behavioral processes that are believed to represent a specialized reflexive defense response on the one hand and an unlearned, unconditioned means of sensorimotor gating that helps identify and enable focus on salient environmental stimuli on the other. Deficits in these processes may also contribute to the intrusive and disorganized thought and exaggerated responses to environmental stimuli that often characterize patients with disorders including schizophrenia, autism and ADHD. The sex and estrous cycle differences that have been noted in ASR and/or PPI in rats and mice [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] and in several patient populations [2, 18, 21, 22, 23] suggest that gonadal hormones contribute to the neurobiology of these processes and perhaps their dysfunction in disease as well. However, to date, there has been little direct investigation of the mechanisms and consequences of hormone action on these behavioral measures. To address these issues, the present study paired gonadectomy and hormone replacement with behavioral testing in adult male rats to isolate and quantify the effects of gonadal steroids on ASR and PPI and to identify the hormone species that may be active in modulating these behaviors. In the sections that follow, the results that were obtained are related to previous experimental studies of gonadal steroid effects on PPI and ASR in rats, and in a final section, the anatomical registry between brain areas involved in startle circuitry and the receptive and enzymatic machinery that governs hormone action in the CNS are discussed in terms of testable hypotheses concerning the neural substrates for hormone modulation of the ASR in adult male rats.

GDX Effects on PPI: Comparison to Previous Studies

Previous studies have shown that PPI can be potently modulated by local infusions of dopamine (DA) agonist and antagonist drugs in the medial prefrontal cortex in rats [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 41, 42]. In view of findings from this laboratory showing that long vs. short term GDX selectively and dynamically regulates anatomical, physiological and behavioral aspects of this mesoprefrontal DA system [30, 31], one objective of this study was to determine whether GDX affected PPI in parallel to its actions on this functionally critical innervation. The approach used was to test animals 2 and 4 days after GDX, when prefrontal DA axon density is strongly depressed; at 9, 16, and 24 days after GDX, when prefrontal DA innervation rises back toward normal levels; and at four and five weeks after surgery, when prefrontal DA innervation has been shown to peak and plateau at densities that are two to three times higher than controls [30, 31]. What was found, however, was that neither GDX nor supplementing GDX rats with E, DHT or TP had any impact on the ability of prepulse stimuli to inhibit startle responses on any of the seven testing days examined. These findings contrast evidence obtained in a previous study in adult male rats that, although like the present study found no effect of GDX on PPI, did observe a potentiation of PPI in GDX adult male rats supplemented with T [29]. In determining what might lead to these differing results, a number of factors can be ruled out. For example, both studies used similar hormone replacement strategies that involved subcutaneous release of physiological levels of T, and both measured PPI between two and three weeks after surgery. However, what may be relevant differences between the two studies were the prepulse stimuli that were used. Not only is the intensity of the prepulse well known to effect the degree to which subsequent responses to startle stimuli are inhibited [43], but there are also studies showing that acute administration of E to OVX female rats has potentiating effects on PPI when inhibition is stimulated by prepulse tones that are 8–16 dB higher than background noise but not when softer prepulses (2–4 dB above background) are used [28]. Although longer term E replacement in OVX females affected PPI in a manner that was independent of prepulse strength [28], and while it is also unknown whether the potentiating effects of supplementing GDX male rats with T showed any similar sort of prepulse stimulus-dependence [29], it still may be critical that the previous study in males used a range of prepulse intensities that bracketed but did not match the single intensity prepulse stimulus used here. The sensitivity of PPI, not only to prepulse intensity, but to other testing parameters as well, e.g., background noise, prepulse duration and interval, has recently been discussed in terms of the challenges this brings to drawing reliable conclusions from cross-study comparisons [43]. That the previous and present studies also differed in background noise levels (60 vs. 70 dB)—a difference that has been shown to significantly affect PPI of eye blink responses in humans to acoustic stimuli [43] suggests that reaching a consensus view of the effects of gonadal steroids on the complex and exquisitely sensitive behavioral measure of PPI in male rats may require additional experiments where testing conditions are more precisely matched.

GDX Effects on the ASR: Comparison to Previous Studies

In investigating gonadal hormone effects on ASR and PPI, essentially the same behavioral experiment was conducted twice using two sets of control and GDX cohorts tested along side GDX rats supplemented with TP in the first experiment and with GDX animals given E or DHT in the second. In both experiments, facilitating effects of GDX on the ASR were seen. These results have precedent in the only previous study examining experimental hormone manipulation on the ASR (and its PPI) in adult male rats that also found that ASR was significantly higher in GDX rats compared to intact controls [29]. However, in the current study, repeated testing also revealed that the enhancing effects of GDX were appreciably larger two days after surgery and during the final few testing sessions one month later compared to the testing sessions carried out in between. Because the previous study in males examined hormone effects in only a single testing session (approximately two weeks after GDX or sham surgery) it cannot speak to a waxing or waning of GDX actions. However, recent studies in ovariectomized (OVX) female rats may show hormone effects on ASR and PPI that vary with treatment duration. Specifically, among the three prior examinations of ASR and PPI in adult female rats, two that studied behavioral effects in OVX rats that were challenged with apomorphine found no group differences between controls and animals that were OVX for one week [28] but a significant apomorphine-induced increase in ASR in rats that were OVX for three months [27]. Together with the results obtained here, these findings suggest that hormone modulation of the ASR in adult rats may vary significantly over time. In females, where hormone effects have been reported on timescales ranging from minutes [28] to weeks and months [27], temporal differences in effects could be related to a differential engagement of rapid actions involving ligand interactions with membrane receptors and slower onset, classical genomic actions mediated by estrogen binding to the multiplicity of its cognate intracellular receptors [44]. In males, the effective timeframes of days to weeks that have been observed all fall within a range that is consistent with genomic, intracellular hormone receptor mediated actions. Accordingly, the on-again, off-again effects observed may be end products different sets of genes and gene products that may differ in their rates of transciption and/or turnover and thus produce the temporally specific changes observed. Accordingly, in attempting to identify these cellular and/or molecular targets, the timing of the behavioral effects observed may provide something of a screen, as relevant changes in gene expression and/or protein levels might be expected to show some relationship to the peaks in the behavioral effects of GDX that ocurred immediately after surgery and then again some weeks later. However, it also possible that the initially observed behavioral effects represent additive or interactive effects between gonadal hormones and a transient stress response, e.g., activation of the hypothalamic pituitary axis, that is likely to occur in all animal subjects soon after surgery; the later occurring effects, on the other hand, may represent the actions of gonadal hormones alone. In either scenario, the relevant biological activity involved in hormone modulation of ASR and/or PPI can be expected to be localized to those brain areas that are active in mediating and/or modulating the ASR. As discussed below, analyses of behavior in GDX animals replaced with TP, E, and DHT may provide information that is useful in further pinpointing potentially important, functionally relevant brain areas.

Attenuation of the Effects of GDX on ASR: Clues from Hormone Replacement about Potential Neural Substrates

The increases in ASR seen in the GDX animals of this study were attenuated by supplementing rats with TP as well as with E and DHT. This was a substantial difference from the previous study in male rats where GDX effects on ASR were attenuated by testosterone (T) but were not appreciably lowered by supplementing GDX rats with E [29]. Both studies used subcutaneous, continuous-release methods of delivery as well as physiological doses of estradiol, thus ruling out perhaps the most obvious causes for such a discrepancy. Nonetheless, this is an important issue to resolve, as the outcomes of the two studies could point to very different hormone signaling pathways as modulating the startle reflex. Thus, from the previous study, findings that T but not E attenuated the effects of GDX suggest that androgen stimulation is principally responsible for modulation of the ASR. In such a scenario, the localization of intracellular androgen receptors (AR) with respect to brain areas mediating and/or modulating the ASR could mark candidate CNS sites where androgen mediated stimulation of the startle reflex may be likely. The ASR is known to be mediated by a small number of sensory and motor brainstem nuclei including the cochlear nucleus and nucleus reticularis pontis caudalis [45], to be attenuated through mechanisms including PPI via structures including the prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, superior and inferior colliculi, substantia nigra and ventral tegemental area, and to be sensitized and/or potentiated through inputs from structures including the periaqueductal grey, hippocampus, locus ceruleus, amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis [4, 5, 9]. Almost without exception each of these areas has been shown to contain substantial concentrations of mRNAs or immunoreactivity for AR [46, 47]. In view of the limited, unidirectional effects of GDX, this broad distribution among brain regions that both increase and decrease ASR suggests that AR alone may not be a suitably discriminating marker for identifying viable candidate brain regions from among the many CNS sites that are known to impact the ASR in rats. However, the presence of the hormone metabolizing enzymes including aromatase, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 3α-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase and 3β-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase could be more useful in this regard. Specifically, in contrast to the previous study in males, findings from this study suggest that not only do both estrogens and androgens modulate the ASR, but they may be most effective when acting together. Thus, while E, DHT and TP all attenuated the effects of GDX, it was also found that the responses of GDX animals given E were almost always lower and were on several occasions significantly lower than controls, whereas the values of ASR in GDX rats given DHT and especially TP more often closely resembled those of the intact animals. Unlike E, both DHT and TP can be locally metabolized in the brain into moieties that are active at estrogen and androgen receptor sites. Thus, findings from across the hormone replacement groups could suggest that ASR is normally modulated by synergistic actions involving both estrogen and androgen signaling pathways. In males where estrogen is not a significant secretory product of the gonads, brain areas where such coordinated stimulation can occur include those that are enriched in the testosterone-metabolizing, estrogen-synthesizing enzyme, aromatase [48]. While brain regions enriched in the enzymes17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 3α-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase and 3β-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase might also be of interest, relevant to this study is the fact that in adult rats, mapping studies have revealed overlap between aromatase activity/immunoreactivity and brain areas that mediate and/or modulate the ASR that involves a highly circumscribed set of structures. In fact, the restricted localization of aromatase activity in the adult rat brain primarily in hypothalamic and limbic brain areas [49, 50, 51] restricts overlap with startle and startle-related circuitry mainly to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, the amygdala and the hippocampus-- three areas that have all been implicated in processes that, like GDX, accentuate the startle reflex in rats. Thus, the bed nucleus of stria terminalis and the hippocampus have been linked to foot-shock and other forms of stress-induced ASR sensitization 5, 52], while lesion and drug infusion studies have identified roles for the amygdala in both sensitization and fear-conditioned potentiation of the ASR [53, 54, 55, 56]. Thus, while the localization of cognate intracellular hormone receptors identifies numerous loci where estrogens and/or androgens could also potentially act to modify ASR, roles for synergistic actions of estrogens and androgens gleaned from this study could more specifically point to the involvement of three principal sites. To test this hypothesis, experimental approaches incorporating selective aromatase inhibitors and behavioral paradigms that differentially assess sensitization versus fear-conditioning of the ASR could be used to confirm roles for local CNS steroid metabolism in the hormone modulation of ASR, and narrow the list of brain areas that could potentially mediate these effects. With this anatomical information in hand, a directed rational search for the cellular and molecular mediators of gonadal hormone modulation of the ASR could be undertaken.

Summary and Conclusions

Even from the very few studies that have begun to use experimental means of hormone manipulation to study the effects of gonadal steroids on ASR and its PPI, evidence for a complex and seemingly sex-specific influence is already emerging. In female rats a consensus view indicates that while changes in circulating gonadal hormones have no effect on baseline measures of ASR or PPI, OVX and hormone replacement can significantly modulate the sensitivity of these behaviors to pharmacologic challenge involving certain receptor agonist and antagonist drugs [27, 28, 29]. In contrast, although not agreeing on all points, evidence from this study and from the only previous investigation in male rats [29] both show significant effects of hormone manipulation (GDX) alone on the ASR. The present study also raised new questions about the mechanisms of hormone action. Specifically, the parallels between brain areas with previously identified roles in potentiating the ASR, the distribution of aromatase in the adult rat brain, and the novel findings from this study suggesting that hormone modulation of the ASR in males may depend on local hormone metabolism leads to testable hypotheses wherein the amygdala, hippocampus and/or bed nucleus of the stria terminalis emerge as candidate neural substrates in the hormone modulation of the ASR in adult male rats. Interestingly, these three areas are also among those that have been repeatedly implicated in the pathohysiology of disorders including schizophrenia—which disproportionately affects males, and in which the ASR and/or PPI are elements of behavior that are at risk. Thus, in continuing to more precisely identify the anatomical loci and ultimately the cellular and molecular targets of gonadal hormone stimulation underlies modulation of the ASR and/or its sensorimotor gating in males, new insights into the neurobiology of these discrete behaviors as well as into the neuropathology associated with their dysfunction in disease may be gained.

Acknowledgments

Mr. Matthew Hernandez, Mr. Alan Meagher and Ms. Aiying Liu are thanked for their expert assisistance in animal surgery and behavioral testing. Dr. L. Craig Evinger (Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Stony Brook University) is thanked for his generous sharing of knowledge and equipment. This work was supported by NS41966 to MFK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Davis M. The mammalian startle response. In: Eaton RC, editor. Neural mechanisms of startle behavior. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. pp. 287–351. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braff DL, Geyer MA, Light GA, Sprock J, Perry W, Cadenhead KS, Swerdlow NR. Impact of prepulse characteristics on the detection of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:171–8. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braff DL, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Human studies of prepulse inhibition of startle: normal subjects, patient groups, and pharmacological studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:234–58. doi: 10.1007/s002130100810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA, Braff DL. Neural circuit regulation of prepulse inhibition of startle in the rat: current knowledge and future challenges. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:194–215. doi: 10.1007/s002130100799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koch M. The neurobiology of startle. Prog In Neurbiol. 1999;59:107–128. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham FK. Presidential Address, 1974. The more or less startling effects of weak prestimulation. Psychophysiology. 1975;12:238–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1975.tb01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman HS, Fleshler M. Startle Reaction: Modification by Background Acoustic Stimulation. Science. 1963;141:928–30. doi: 10.1126/science.141.3584.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman HS, Ison JR. Reflex modification in the domain of startle: I. Some empirical findings and their implications for how the nervous system processes sensory input. Psychol Rev. 1980;87:175–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fendt M, Li L, Yeomans JS. Brain stem circuits mediating prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:216–24. doi: 10.1007/s002130100794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang WN, Bast T, Feldon J. Microinfusion of the non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist MK-801 (dizocilpine) into the dorsal hippocampus of wistar rats does not affect latent inhibition and prepulse inhibition, but increases startle reaction and locomotor activity. Neuroscience. 2000;101(3):589–99. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00418-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aguilar R, Gil L, Gray JA, Driscoll P, Flint J, Dawson GR, Gimenez-Llort L, Escorihuela R. M; Fernandez-Teruel, A., Tobena, A. Fearfulness and sex in F2 Roman rats: males display more fear though both sexes share the same fearfulness traits. Physiol Behav. 2003;78:723–32. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaszczyk J, Tajchert K. Sex and strain differences of acoustic startle reaction development in adolescent albino Wistar and hooded rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 1996;56:919–25. doi: 10.55782/ane-1996-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulinello M, Orman R, Smith SS. Sex differences in anxiety, sensorimotor gating and expression of the alpha4 subunit of the GABAA receptor in the amygdala after progesterone withdrawal. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:641–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch M. Sensorimotor gating changes across the estrous cycle in female rats. Physiol Behav. 1998;64:625–8. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehmann J, Pryce CR, Feldon J. Sex differences in the acoustic startle response and prepulse inhibition in Wistar rats. Behav Brain Res. 1999;104:113–7. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plappert CF, Rodenbucher AM, Pilz PK. Effects of sex and estrous cycle on modulation of the acoustic startle response in mice. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:585–94. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kofler M, Muller J, Reggiani L, Valls-Sole J. Influence of gender on auditory startle responses. Brain Res. 2001;921:206–10. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumari V, Aasen I, Sharma T. Sex differences in prepulse inhibition deficits in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;69:219–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jovanovic T, Szilagyi S, Chakravorty S, Fiallos AM, Lewison BJ, Parwani A, Schwartz MP, Gonzenbach S, Rotrosen JP, Duncan EJ. Menstrual cycle phase effects on prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:401–6. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.2004.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swerdlow NR, Hartman PL, Auerbach PP. Changes in sensorimotor inhibition across the menstrual cycle: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:452–60. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castellanos FX, Fine EJ, Kaysen D, Marsh WL, Rapoport JL, Hallett M. Sensorimotor gating in boys with Tourette's syndrome and ADHD: preliminary results. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grillon C, Ameli R, Charney DS, Krystal J, Braff D. Startle gating deficits occur across prepulse intensities in schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;32:939–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90183-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tantillo M, Kesick CM, Hynd GW, Dishman RK. The effects of exercise on children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:203–12. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200202000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry W, Minassian A, Lopez B, Maron L, Lincoln A. Sensorimotor Gating Deficits in Adults with Autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAlonan GM, Daly E, Kumari V, Critchley HD, van Amelsvoort T, Suckling J, Simmons A, Sigmundsson T, Greenwood K, Russell A, Schmitz N, Happe F, Howlin P, Murphy DGM. Brain anatomy and sensorimotor gating in Asperger’s syndrome. Brain. 2002;127:1594–1606. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frankland PW, Wang Y, Rosner B, Shimizu T, Balleine BW, Dykens EM, Ornitz EM, Silva AJ. Sensorimotor gating abnormalities in young males with fragile X syndrome and Fmr1-knockout mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:417–425. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaillancourt C, Cyr M, Rochford J, Boksa P, Di Paolo T. Effects of ovariectomy and estradiol on acoustic startle responses in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;74:103–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00967-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van den Buuse M, Eikelis N. Estrogen increases prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;425:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gogos A, van den Buuse M. Castration reduces the effect of serotonin-1A receptor stimulation on prepulse inhibition in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1407–15. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adler A, Vescovo P, Robinson JK, Kritzer MF. Gonadectomy in adult life increases tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the prefrontal cortex and decreases open field activity in male rats. Neuroscience. 1999;89:939–54. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kritzer MF. Long-term gonadectomy affects the density of tyrosine hydroxylase- but not dopamine-beta-hydroxylase-, choline acetyltransferase- or serotonin-immunoreactive axons in the medial prefrontal cortices of adult male rats. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:282–96. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broersen LM, Feldon J, Weiner I. Dissociative effects of apomorphine infusions into the medial prefrontal cortex of rats on latent inhibition, prepulse inhibition and amphetamine-induced locomotion. Neuroscience. 1999;94:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellenbroek BA, Budde S, Cools AR. Prepulse inhibition and latent inhibition: the role of dopamine in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1996;75:535–42. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zavitsanou K, Cranney J, Richardson R. Dopamine antagonists in the orbital prefrontal cortex reduce prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;63:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Jong IEM, van den Buuse M. SCH 23390 in the prefrontal cortex enhances the effect of apomorphine on prepulse inhibition of rats. Neuropharmacology. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swerdlow NR, Shoemaker JM, Kuczenski R, Bongiovanni MJ, Neary AC, Tochen LS, Saint Marie RL. Forebrain D1 function and sensorimotor gating in rats: Effecs of D1 blockade, frontal lesions and dopamine denervation. Neurosci Lett. 2006;402:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carmignac DF, Gabrielsson BG, Robinson IC. Growth hormone binding protein in the rat: effects of gonadal steroids. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2445–52. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins WF, 3rd, Seymour AW, Klugewicz SW. Differential effect of castration on the somal size of pudendal motoneurons in the adult male rat. Brain Res. 1992;577:326–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90292-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kritzer MF. Effects of acute and chronic gonadectomy on the catecholamine innervation of the cerebral cortex in adult male rats: insensitivity of axons immunoreactive for dopamine-beta-hydroxylase to gonadal steroids, and differential sensitivity of axons immunoreactive for tyrosine hydroxylase to ovarian and testicular hormones. J Comp Neurol. 2000;427:617–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wainman P, Shipounoff GC. The effects of castration and testosterone propionate on the striated perineal musculature in the rat. Endocrinology. 1941;29:975–978. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koch M, Bubser M. Deficient sensorimotor gating after 6-hydroxydopamine lesion of the rat medial prefrontal cortex is reversed by haloperidol. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:1837–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lacroix L, Broersen LM, Feldon J, Weiner I. Effects of local infusions of dopaminergic drugs into the medial prefrontal cortex of rats on latent inhibition, prepulse inhibition and amphetamine induced activity. Behav Brain Res. 2000;107:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsieh MH, Swerdlow NR, Braff DL. Effects of background and prepulse characteristics on prepulse inhibition and facilitation: Implications for neuropsychiatric research. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:555–559. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toran-Allerand CD. Estrogen and the brain beyond Eralpha, Erbeta and 17-beta estradiol. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1052:136–144. doi: 10.1196/annals.1347.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Y, Lopez DE, Meloni EG, Davis M. A primary acoustic startle pathway: obligatory role of cochlear root neurons and the nucleus reticularis pontis caudalis. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3775–89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-11-03775.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clancy AN, Bonsall RW, Michael RP. Immunohistochemical labeling of androgen receptors in the brain of rat and monkey. Life Sci. 1992;50:409–17. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90375-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simerly RB, Chang C, Muramatsu M, Swanson LW. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA-containing cells in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294:76–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lephart ED. A review of brain aromatase cytochrome P450. Brain Res Rev. 1996;22:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacLusky NJ, Walters MJ, Clark AS, Toran-Allerand CD. Aromatase in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and midbrain: Ontogeny and developmental implications. Mol Cell Neuorsci. 1994;5:691–698. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner CK, Morrell JI. Neuroanatomical distribution of aromatase mRNA in the rat brain: indications of regional regulation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;61:307–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balthazart J, Ball GF. New insights into the regulation and function of brain estrogen synthase (aromatase) TINS. 1998;21:243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee Y, Davis M. Role of the hippocampus, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and the amygdala in the excitatory effect of corticotropin-releasing hormone on the acoustic startle reflex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6434–6446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06434.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koch M. Microinjections of the metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist, trans (+-+-1-amino-cyclopentatne-1,3 dicarboxylate (trans-ACPD) into the amygdala increase the acoustic startle response of rats. Brain Res. 1993;629:176–179. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90500-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yeomans JS, Pollard BA. Amygdala efferents mediating electrically evoked startle-like responses and fear potentiation of acoustic startle. Beha Neurosci. 1993;107:596–610. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.4.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fendt M, Koch M, Schnitzler HU. Amygdaloid noradrenaline is involved in the sensitization of the acoustic startle reflex. Phamacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:307–314. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schanbacher A, Koch M, Pilz PKD, Schniztler HU. Lesions of the amygdala do not affect the enhanvement of the acoustic startle response by background noise. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:1341–1346. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]