Abstract

Recent work on the sea urchin endomesoderm gene regulatory network (GRN) offers many opportunities to study the specification and differentiation of each cell type during early development at a mechanistic level. The mesoderm lineages consist of two cell populations, primary and secondary mesenchyme cells (PMCs and SMCs). The micromere-PMC GRN governs the development of the larval skeleton, which is the exclusive fate of PMCs, and SMCs diverge into four lineages, each with its own GRN state. Here we identify a sea urchin ortholog of the Twist transcription factor, and show that it plays an essential role in the PMC GRN and later is involved in SMC formation. Perturbations of Twist either by morpholino knockdown or by overexpression result in defects in progressive phases of PMC development, including specification, ingression/EMT, differentiation and skeletogenesis. Evidence is presented that Twist expression is required for the maintenance of the PMC specification state, and a reciprocal regulation between Alx1 and Twist offers stability for the subsequent processes, such as PMC differentiation and skeletogenesis. These data illustrate the significance of regulatory state maintenance and continuous progression during cell specification, and the dynamics of the sequential events that depend on those earlier regulatory states.

Keywords: Twist, Mesoderm, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Gene regulatory network, Primary mesenchyme cell, Skeletogenesis

Introduction

In sea urchin embryos, primary mesenchyme cells (PMCs) exclusively form larval skeletons, while secondary mesenchyme cells (SMCs) divide into four subpopulations, i.e. pigment cells, esophageal muscles, blastocoelar cells, and coleomic pouch cells. With the exception of coelomic pouch cells all PMCs and SMCs are specified and then ingress, a transit that transforms them from an epithelial to a mesenchymal phenotype.

Micromeres, the PMC precursors, appear at 16-cell stage as a result of an unequal cleavage in the vegetal hemisphere. During early cleavage, they become autonomously specified (Horstadius, 1973; Okazaki, 1975; Davidson, 1989; Davidson et al., 1998; McClay et al., 1992; Ransick and Davidson, 1993) and are first to penetrate through the basal lamina via ingression, a classic epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process, first carefully described in the sea urchin by (Katow and Solursh, 1980). The micromere-PMC GRN has reached an advanced stage of understanding (Oliveri et al 2003; Revilla-i-Domingo et al., 2007). This advance is based on detailed perturbation analyses of a number of genes involved in the early micromere-PMC specification including pmar1 (Oliveri et al., 2003), alx1 (Ettensohn et al., 2003), ets1 (Kurokawa et al., 1999), hesC (Revilla-i-Domingo et al., 2007), tbr (Fuchikami et al., 2002), dri (Amore et al., 2003), hnf6 (Otim et al., 2004)], and recently, at the EMT/PMC transition [snail; (Wu and McClay, 2007)]. SMCs, the other mesodermal cell type in the early embryo, begin specification as a result of the Delta/Notch signaling pathway, which signals endomesoderm tissue to be subdivided into SMCs and definitive endoderm between about 7th to 9th cleavage (Sherwood and McClay, 1999; Sweet et al., 2002). The earliest known gene in this specification sequence is gcm (Ransick and Davidson, 2006), which is a direct target of the Notch signaling pathway. The SMC regulatory state is less understood and little is known about the subsequent diversification of the SMC lineages. Nevertheless, SMCs of the pigment cell, blastocoelar cell and muscle cell fates eventually undergo EMTs that appear similar to the PMC ingressions, but SMCs separate from the tip of the archenteron during gastrulation. The underlying detailed molecular mechanisms involved in this EMT is also little understood, though recent studies show that snail is necessary for ingression of those lineages as it is for PMC ingression (Wu and McClay, 2007). Given the advanced knowledge of micromere specification, and the shared functional activity of Snail in both PMC and SMC ingression, we decided to examine twist, which, like snail, is well documented for its evolutionarily conserved roles in mesoderm development (see review in Castanon and Baylies, 2002).

The twist gene was first identified in Drosophila as a mutant embryo with a twisted torso (Simpson, 1983; Nusslein-Volhard et al., 1984). Extensive studies in Drosophila have shown that Twist activity is crucial for many aspects of embryogenesis, such as establishment of dorsoventral tissue patterning, specification of mesodermal fate, and myogenesis (Baylies and Bate, 1996; Cripps and Olson, 1998; Leptin, 1991; Thisse et al., 1987). Other studies in vertebrates and C. elegans further support the notion that Twist is generally involved in the patterning of mesodermal tissue fates, especially for compartmentalization of muscle development. For example, the C. elegans Twist homolog, hlh-8, plays a critical role in the formation of non-striated muscles (Corsi et al., 2000). Twist-/- mutant mouse embryos display severe defects in closure of the cephalic neural tube, deficient mesoderm, malformed branchial arches, defective cranial neural crest cell migration, and retarded development of the limb bud (Chen and Behringer, 1995; O'Rourke et al., 2002; Soo et al., 2002; Zuniga et al., 2002). Twist-null heterozygous mice (Twist+/-) exhibit phenotypes similar to the dominantly inherited Saethre-Chotzen syndrome in the human population (Bourgeois et al., 1998), which is possibly due to the haplo-insufficiency of the Twist allele (el Ghouzzi et al., 1997; Howard et al., 1997). The multiple roles for Twist as seen by interference in many morphogenetic roles in the mouse suggest that actually, Twist function occurs well upstream of the morphogenetic events themselves. This is supported in model organisms where earlier events have been studied. For example, during mesoderm specification and differentiation, Twist has been implicated as an EMT regulator (Rosivatz et al., 2002) for its role in activating DN-cadherin during Drosophila embryogenesis (Oda et al., 1998) [note that in mammals E-cadherin is downregulated by Snail (Cano et al., 2000)]. Twist's role in tumor progression notably sustains and enhances this notion (Yang et al., 2004). Forced Twist expression is sufficient to induce phenotypic and molecular hallmarks of an EMT in different cell lines (Yang et al., 2004), suggesting that Twist expression precedes initiation of metastasis. Furthermore, the nuclear translocation of Twist protein also impacts cell migration during tumor metastasis (Alexander et al., 2006).

In sea urchin embryos, the PMCs and SMCs are excellent models for studying specification leading to control of ingression and later morphogenetic events. The detailed knowledge of the sea urchin endomesoderm GRN (Davidson et al., 2002) provides a useful tool to examine how sea urchin Twist participates in the mechanisms of mesoderm formation. The goal of this study therefore was to determine how Twist functions in the context of dynamic gene network states in order to gain insight into its frequent association with morphogenetic processes, such as PMC ingression.

In this study, we report the identification, characterization, and functional analyses of Lvtwist, a member of the Twist family of transcription factors in Lytechinus variegatus. Additionally, we also identify Twist in Strongylocentrotus purpuratus genome. We show that Lvtwist is required in micromeres for proper PMC development, such as migration and fusion. Moreover, Lvtwist positively regulates PMC differentiation and skeletogenesis. We further fit Lvtwist into the micromere-PMC GRN model, and examine its regulatory relationships with many key PMC genes.

Materials and methods

Animals and drug treatments

Lytechinus variegatus adults were obtained from Sea Life (Tavernier, FL), or from the Duke University Marine Laboratory at Beaufort, NC. Gametes were harvested, fertilized, cultured and injected by standard methods.

Cloning of Lvtwist

The coding sequence of Lvtwist was obtained by RT-PCR from a Lytechinus variegatus gastrula cDNA library (GenBank Accession Number EU113053). The PCR products were cloned into a pCS2 vector for mRNA synthesis. Strongylocentrotus purpuratus Twist protein sequence was annotated and deposited on GenBank (Accession Number DAA06084).

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed using standard methods with DIG-labeled RNA probes and BM purple substrate (Roche) for detection (see methods in Wu and McClay, 2007). Hybridizations and subsequent washes were carried out at 60-65°C depending on the probes. Four different Lvtwist probes were tested; the longest probe (which consists of the Lvtwist open reading frame plus both 5′ and 3′UTR sequences) was used in all experiments in this study since it was more sensitive than others, although all probes gave us basically the similar results. Other probes and clones used here (Lvets1, Lvalx1 and Lvsnail) were previously described (Wu and McClay, 2007). For each perturbation, the hybridization conditions and staining times are the same between experimental and control sets.

Morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (MASO) and mRNA injections

Two non-overlapping Lvtwist-specific MASOs were obtained from Gene Tools, and both have the same efficiency at 1 to 1.5 mM (final embryonic concentration, 8.3 pg per embryo). [Oligo1 (-2 bp to +23 bp, relative to the AUG translation start site): 5′-TTCATCTTCGGCGCGTGAACCATTT-3′; Oligo2 [-51 bp to -27 bp): 5′-CGTACTCGTACCCTCCGCAGTAAAC-3′]. Each injected mRNA was transcribed in vitro using the mMessage mMachine Kit (Ambion), and diluted in ddH2O. A final concentration of 2 μg/μL was used for twist mRNA.

Transplantation experiments

Micromere transplantations were performed at 16-cell stage, with L. variegatus embryos. Detailed procedures were followed as previously described (Logan et al., 1999). For the PMC fusion experiments, two micromeres were transplanted inside the blastocoel of the 32- or 60-cell stage, using procedures similar to micromere swapping experiments (Wu and McClay, 2007), and fixable fluorescent dyes, CFDA-SE (Invitrogen) and tetramethylrhodamine dextran (Invitrogen) were used for subsequent immunostaining.

Immunostaining

Embryos were methanol-fixed, stained with 1d5 mAb (1:200), anti-β-catenin pAb (1:50), or anti-myosin pAb (1:750) in 4% normal goat serum/PBS, and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing three times in PBS, samples were incubated with Cy2, Cy3 or Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) for 1-2 hour at room temperature, and then imaged as described (Gross et al., 2003).

Quantitative RT-PCR (QPCR) analysis

Total RNA was prepared from 10-20 embryos using Trizol (Invitrogen) with a glycogen carrier (Ambion). The sample was used for reverse transcriptase (RT) reactions with Taqman RT-PCR kits (Applied Biosystems) after pretreatment with DNase I (DNA-free, Ambion). QPCR was then performed using Roche LightCycler and the FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche). For perturbation, the following equation (adapted from http://sugp.caltech.edu/endomes/qpcr.html) was used for calculating the relative changes of gene expression between samples and controls: ΔCT = [Ub-C]-[Ub-Exp]. Ubiquitin (Ub) mRNA control used for internal standardization; C, sample from control embryo; Exp, sample from perturbed embryos. The number and type of replicates measured for each sample is specified and reported in Tables. The time course of twist expression is constructed according to the methodologies described in Howard-Ashby et al., 2006a, with minor changes in gauging Ubiquitin expression level [we used 50,000 copies/embryo, instead of 87,000 copies/embryo, as determined previously (Nemer et al., 1991)].

Results

Cloning and sequence analysis of Lvtwist

The twist gene belongs to a diverse group of transcription factors that share a common basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) motif. The bHLH domain was first recognized in the murine DNA-binding proteins E12 and E47 (Murre et al., 1989), and subsequently identified in a number of proteins that play important roles in cell specification, tissue differentiation, and growth regulation (Dambly-Chaudiere and Vervoort, 1998; Hjalt, 2004).

Using RT-PCR and RACE, the open reading frame of Lytechinus variegatus twist (Lvtwist) was amplified and cloned from a gastrula stage cDNA pool. Lvtwist encodes a 201 amino-acid polypeptide based on the primary sequence data. Although twist was not annotated in the recently published genome of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (Howard-Ashby et al., 2006b; Sodergren et al., 2006), we identified the Sptwist gene in silico, which encodes a 204 amino acid polypeptide, by blasting the assembly of S. purpuratus genome with the coding sequence of Lvtwist. The ClustalW pairwise alignment between LvTwist and SpTwist shows that two proteins share an overall amino acid identity of 92% (data not shown), despite being separated by 30-40 million years.

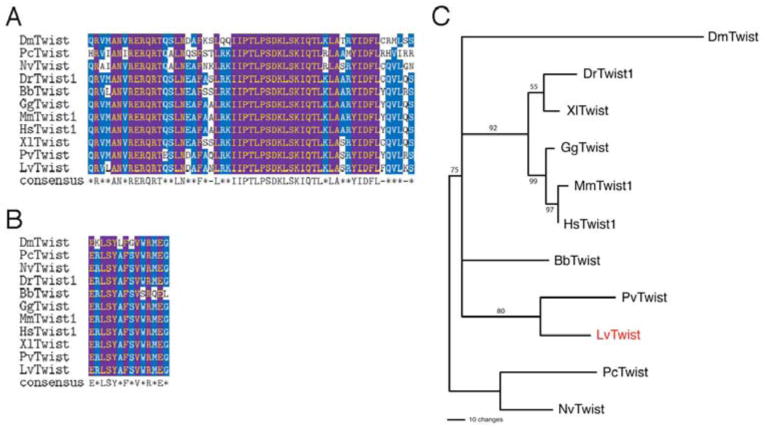

Members of twist gene family have been identified in different species representing broad evolutionary distances, including jellyfish (PcTwist; Spring et al., 2000), sea anemone (NvTwist; Martindale et al., 2004), and C. elegans (CeTwist, hlh-8; selectively excluded from our analysis due to its substantial divergence; (Harfe et al., 1998). Multiple sequence alignment of Twist proteins shows that LvTwist and other Twist family members are highly conserved within the bHLH domain (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, LvTwist is identical to almost all Twist proteins except Drosophila Twist (DmTwist) and amphioxus Twist (BbTwist; Yasui et al., 1998) at all 14 residues of the WR motif (Fig. 1B; ERLSYAFSVWRMEG), which is a C-terminal motif characteristic for the Twist protein family (Spring et al., 2000). Phylogenetic analysis based on Twist protein sequences (Fig. 1C), as well as the strong conservation of distinct protein motifs, strongly supports the orthology of Lvtwist to other twist family genes.

Fig. 1. Sequence comparisons of Lytechinus variegatus Twist and related Twist family proteins.

(A) The bHLH DNA-binding domain of L. variegatus Twist (LvTwist) compared to related proteins in other organisms. Species: Bb, Branchiostoma belcheri; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Dr, Danio rerio; Gg, Gallus gallus; Hs, Homo sapiens; Mm, Mus musculus; Nv, Nematostella vectensis; Pc, Podocoryne carnea; Pv, Patella vulgata; Xl, Xenopus laevis. (B) The WR domain of LvTwist matches the consensus and is identical to those of most twist family members, including Nematostella, mouse and Xenopus Twist. (C) Rooted neighbor-joining tree showing the relationship of LvTwist with other twist family proteins (1000 bootstraps, values indicated on nodes). Nematostella and Podocoryne Twist served as outgroups.

Lvtwist mRNA is expressed predominantly in mesoderm during gastrulation

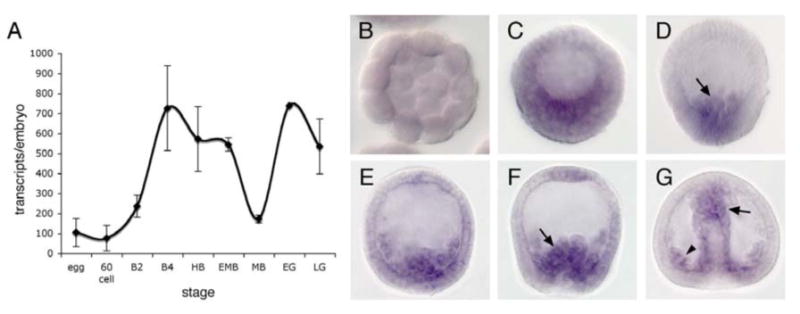

A temporal expression profile of Lvtwist mRNA showed the expression level of Lvtwist remains relatively low during early cleavage stages, and the expression increases starting from blastula stages, then transiently drops at mesenchyme blastula (MB) stage. The transcripts accumulate again later at gastrula stages (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. The spatiotemporal expression patterns of Lvtwist mRNA during sea urchin embryogenesis.

(A) A temporal expression profile by QPCR shows the dynamic expression levels of Lvtwist mRNA between fertilized egg and late gastrula. The error bars represent the s.e.m from two QPCR measurements. (B-G) WMISH shows the expression domains of Lvtwist mRNA. Lvtwist mRNA is detected in the vegetal plate (C), the early ingressing PMCs (arrow in D) and ingressed PMCs (E). (F) Early gastrula stage (EG): Lvtwist mRNA starts to be expressed in SMCs (arrow) and also persists in PMCs. (G) Late gastrula stage (LG): Lvtwist mRNA continues to be expressed in PMCs (arrowhead), the SMC territory (arrow) and the archenteron.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) showed that Lvtwist mRNA is expressed in the mesoderm lineages, PMCs and SMCs (Fig. 2B-G). Embryos at early stages do not show any expression (Fig. 2B). The expression appears after hatching and by late hatched blastula (LHB) stage faint staining can be observed at the vegetal plate of the embryo (Fig. 2C). At early mesenchyme blastula (MB) stage, Lvtwist mRNA is predominantly expressed in ingressing PMCs (Fig. 2D-E). The PMC expression of Lvtwist is maintained after MB stage and throughout the gastrulation (Fig. 2F-G), [unlike snail expression, which disappears from PMCs shortly after ingression (Wu and McClay, 2007)]. Lvtwist expression is observed in the SMC territory from the early gastrula (EG) stage (Fig. 2F), and also the archenteron may express snail at a low level at late gastrula (LG) stage (Fig. 2G).

Functional Knockdown of LvTwist results in various defects in PMC development

To determine the function of LvTwist in sea urchin development, we designed and injected morpholino antisense oligonucleotides specifically against Twist (TwiMASO) into fertilized eggs to interfere with endogenous LvTwist translation. To test the efficiency of the two morpholinos used in this study, co-injection of either TwiMASO or a standard control morpholino (from Gene Tools) and a GFP construct containing the target sequence complementary to the morpholino was performed. The TwiMASO specifically blocked the GFP expression (Fig. 3N), and injecting the control morpholino at the same or higher concentration than the TwiMASO had no effect on development (Fig. 3M); moreover, both Twist-specific morpholinos (see Materials and Methods) caused the same phenotypic and molecular consequences. We therefore were confident that the TwiMASOs specifically targeted Twist and blocked its translation.

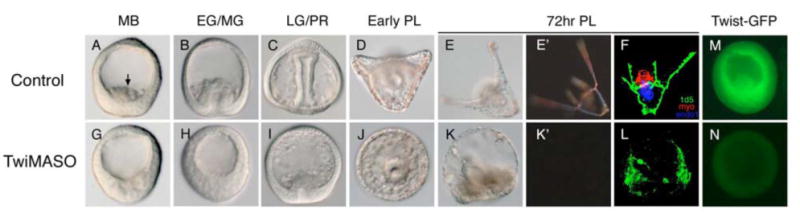

Fig. 3. PMC ingression, skeletogenesis, and SMC formation are impaired by TwiMASO injection.

(A-E′) Control embryos show normal PMC ingression (arrow in A) with elaborate larval skeletons, which are clearly visible under polarized light (E-E′). (G-K′) Embryos injected with TwiMASO. Compared to the control, TwiMASO-injected embryos (Twi morphants) show delayed PMC ingression until LG stage (G-I), and show no skeleton at the PL stage (J). Skeletogenesis is persistently blocked in Twi morphants even at 72-hour post-fertilization (hpf) (K-K′), and the numbers of pigment cells is reduced (K). Note that the archenteron elongation is also defective, although only observed in about 25% of the perturbed embryos. (F,L) Muscle formation is affected in Twi morphants. (F) Control 27hr-hpf pluteus larvae show normal muscle development (shown by myosin antibody in red), normal PMC pattering (1d5) and differentiated archenteron (endo1). (L) The staining of muscle is absent in Twi morphants as well as the staining of the endoderm marker, endo1. The 1d5 staining indicates that PMCs are differentiated, but highly disorganized. (M,N) Testing the specificity of Twist morpholino. Embryos co-injected with Twist-GFP mRNA and control morpholino express GFP in every cell and show normal development (M), while embryos co-injected with Twist morpholino (instead of control) do not show any GFP fluorescence, but do exhibit TwiMASO phenotypes (N). Stages: MB, mesenchyme blastula; EG, early gastrula; MG, mid-gastrula; LG, late gastula; PR, prism; PL, pluteus larvae.

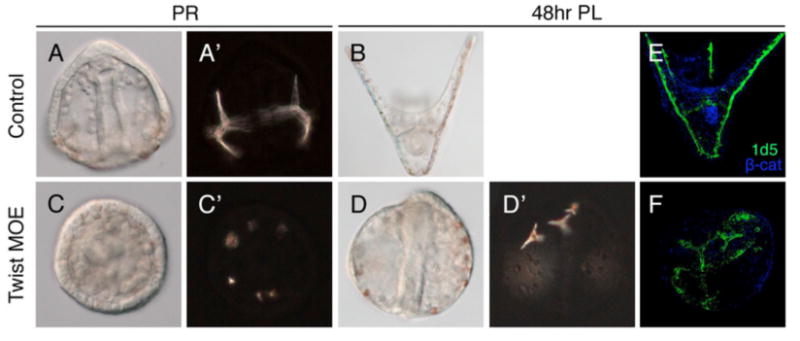

TwiMASO-injected embryos (‘Twi morphants’) developed normally through early cleavage stages, and hatched at the same time as controls. When PMCs of control embryos ingressed into the blastocoel at MB stage (Fig. 3A, arrow), PMCs of Twi morphants failed to ingress (>80%, Fig. 3E) until after a significant delay. When control injected siblings reached mid-gastrula stage (Fig. 3B), Twi morphants showed the first signs of ingression. Twi morphants also delayed invagination of the archenteron (Fig. 3G). Invagination of the archenteron begins with infolding of the SMCs suggesting that specification upstream of invagination in SMCs is an additional role for Twist. The archenteron later invaginated and differentiated with no lasting effects, but, while PMCs eventually formed a ring around the archenteron, Twi morphants failed to form a skeleton (Fig. 3I). Control embryos at the pluteus stage showed normal skeletal patterns (Fig. 3D). To confirm the skeletal phenotypes in Twi morphants, we cultured the embryos for longer periods to see if skeletogenesis ultimately recovers. At 72hrs, control embryos exhibited normal and elaborate skeletal patterns (Fig. 3E-E′), while Twi morphants had no larval skeleton (Fig. 3K-K′). Other SMC-associated phenotypes were also observed to persist including reduction of pigment cells (Fig. 3E,K; Fig. S1) and absence of muscle (as shown by myosin antibody staining in Fig. 3F,L). Moreover, overexpression of twist mRNA results in defects in the PMC organization and skeletogenesis (Fig. 4). Compared to controls (Fig. 4A,B,E), twist mRNA-injected embryos exhibited extra spicules (Fig. 4C-C′), mis-positioned skeletal elements (Fig. 4D-D′), and disorganized skeletal patterning (as shown by the 1d5 monoclonal antibody, which recognizes an oligosaccharide on the MSP130 glycoprotein specifically expressed by PMCs; compare Fig 4E with Fig. 4F). This outcome might be expected if the skeleton regulatory apparatus is mis-controlled. Taken together, these phenotypes of Twi morphants strongly suggest that twist is involved prior to PMC ingression with lasting effects on PMCs, and in the specification and function of SMCs, consistent with the expression patterns of twist. Given these initial findings the next experiments focused more precisely on Twist's role in PMC development since the micromere-PMC GRN currently is better understood than the SMC GRN.

Fig. 4. Overexpression of Lvtwist mRNA perturbs skeletogenesis.

(A-B) Control embryos at the PR stage and the 48hr PL stage show normal skeletal pattering. (C-D′) Embryos injected with twist mRNA (Twist MOE) show supernumerary and random spicules, which can be clearly seen under the polarized light (C′). Triradiate spicules display abnormal positioning in 48hr-Twist MOE embryos (D′). PMCs are also disorganized in Twist MOE embryos (F), compared to controls (E) as shown by 1d5 staining.

LvTwist functions in micromeres and is crucial for migratory behaviors of PMCs

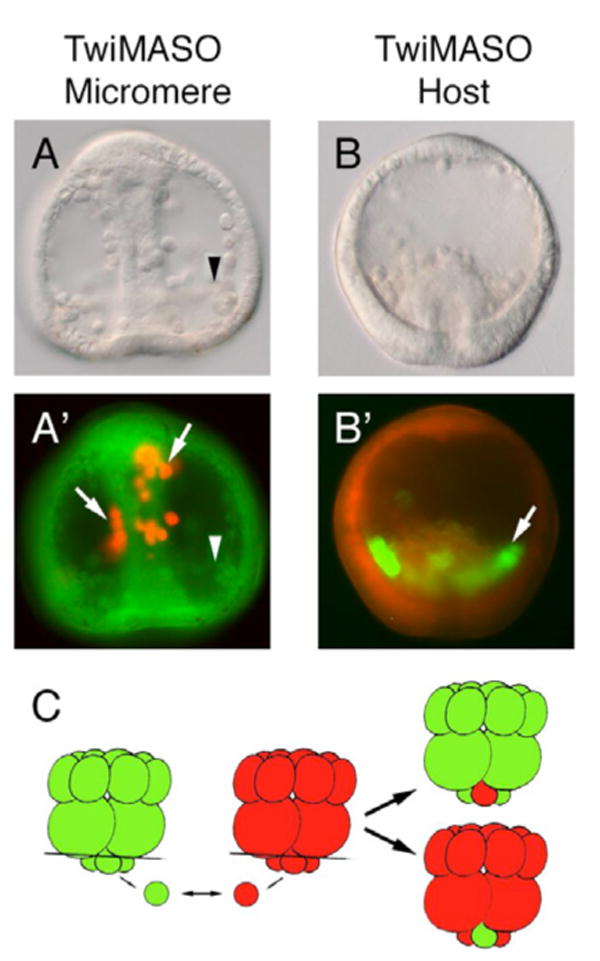

To examine the specific properties of LvTwist on PMC development, chimeric embryos were generated to localize Twist function (Fig. 5C). A single micromere from a control host (stained with FITC, shown in green) was replaced with one TwiMASO-injected micromere (with rhodamine-conjugated dextran, shown in red) (Fig. 5A-A′). The red micromere progeny initiated ingression but failed to migrate properly and remained associated/attached to the archenteron (Fig. 5A′, arrows), while the green micromere progeny (serving as internal controls) ingressed, migrated normally, and settled at the bottom of the blastocoel (Fig. 5A-A′; arrowheads). The reciprocal experiment showed that progeny of a single green control micromere ingressed normally when placed onto a red-dyed TwiMASO-injected host (Fig. 5B-B′; arrow). The chimeras show that Twist is essential in micromeres for these cells to ingress punctually and migrate properly into the blastocoel as PMCs. The TwiMASO-micromeres on control hosts are especially informative since the control embryo gastrulates normally and carries the incompletely ingressed PMCs along with it. The incompletely ingressed PMCs cross the basal lamina but seem to be unable to break their connection with the epithelium until much later, a substantial difference relative to SnaMASO-micromeres which fail completely to initiate ingression (Wu and McClay, 2007).

Fig. 5. Chimeric embryos demonstrate Twist is required in micromeres for PMC migration.

(A-A′) A single TwiMASO-containing micromere (red) was transplanted onto a control host embryo lacking one micromere (green). Progeny of the TwiMASO micromere failed to ingress and migrate properly then spread along the archenteron (arrows in A′), while progeny of endogenous control micromeres ingressed and migrated normally (arrowheads). (B-B′) The reciprocal experiment to that in A. Progeny of one normal micromere (green) ingressed into the blastocoel (arrow in B′) when transplanted to a TwiMASO-injected host embryo lacking one micromere (red). (C) The schematic diagram of the experimental designs of A and B. See text for details.

The role of LvTwist in the micromere-PMC GRN

To achieve a better molecular understanding of the effects of LvTwist on PMC formation, we examined the expression of key genes of the micromere-PMC GRN that might control, or be controlled by twist expression. Three transcription factors are known to be crucial for ingression in the micromere-PMC GRN. Each, when knocked down by morpholinos, causes a failure to ingress; alx1 (Ettensohn et al., 2003) and ets1 (Kurokawa et al., 1999; Rottinger et al., 2004) are part of the early PMC specification network, and Snail is expressed just prior to EMT, and is necessary, shortly after its expression, for PMC ingression (Wu and McClay, 2007). First, we measured mRNA expression of these genes at the three time points at one-hour intervals (LHB, about one hour before PMC ingression; EMB, PMC ingression begins; and MB, PMC ingression nears completion) in the presence of TwiMASO by QPCR to see if LvTwist regulates any of these genes (Table 1). In Twi morphants, Lvalx1 expression level is reduced at MB stage, but not at earlier stages, while Lvets1 expression is unaffected in Twi morphants. WMISH studies on Twi morphants and control siblings corroborated these results at MB stage. In the absence of Twist, the PMCs failed to ingress (Fig. 6B,D,F), Lvalx1 showed a significantly diminished expression when compared to controls (Fig. 6A,B), while Lvets1 continued to be expressed in the PMC precursors (Fig. 6C,D). Lvsnail mRNA expression at MB is slightly decreased by WMISH (Fig. 6E,F), again, in agreement with the QPCR analyses. Collectively, these data suggest that LvTwist plays an important regulatory role in the PMC GRN.

Table 1.

Effects of Twist knockdown on the expression level of different PMC genes measured by QPCR.

| Late HB | Early MB | MB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lvalx1 | NS, NS/ NS, NS/ NS | NS, NS/ NS, NS/ -1.61, NS | NS/ NS/ -1.58†/ -1.98/-2.06 |

| Lvsnail | -4.43, -4.24/ -4.39, -4.51/ -5.57 | NS, NS | NS, NS/ NS/ +2.06/ -2.75/ -2.34/ NS |

| Lvets1 | NS, NS/ NS, NS/ NS | NS, NS/ NS/ NS, NS | NS, NS/ NS, NS/ NS, NS/ NS |

| Lvsm30 | NA | NA | NS/ -1.87/ -5.34 |

| Lvsm50 | -6.26/ -4.08 | NS/ -1.44† | NS/ -3.85/ -2.3 |

| Lvmsp130 | NS/ -1.47† | NS/ NS | -3.53/ -3.16/ -3.88/ NS/ NS |

Data listed are considered significant, whereas non-significant effects (normalized CT difference from control is greater than −1.6 or less than +1.6) are shown as NS.

Commas separate replicate measurements in the same cDNA batch; The solidus separates different batches of cDNA from independent experiments.

Stages: HB (Hatched Blastula); MB (Mesenchyme Blastula).

This measurement, although below the significance, does exhibit the same trend of response to the perturbation as other samples.

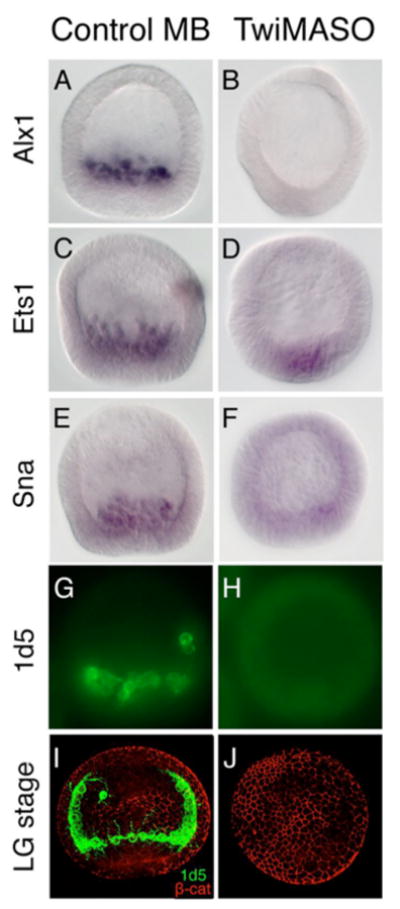

Fig. 6. Effects of TwiMASO in PMC specification and differentiation.

(A-F) In situ hybridizations with Lvalx1, Lvets1 and Lvsnail probes. Control mesenchyme blastula stage embryos show normal expression of these three genes in PMCs (A,C,E). Expression of alx1 is strongly reduced in Twi morphants (B); however, expression of ets1 shows no change (D), while snail retains some expression (F). (G-J) Immunostaining with PMC mAb 1d5 shows the strong presence of 1d5 in controls (G,I), but no expression of 1d5 detectable in Twi morphants (H,J). Anti-β-catenin staining was used to outline the cell boundaries (I,J). MB, mesenchyme blastula stage; LG, late gastrula stage.

Downstream of Twist, the mRNA expression level of Lvmsp130, Lvsm50, and Lvsm30 were examined by QPCR, and were all significantly reduced in Twi morphants when compared to MB controls; Lvsm50, but not Lvmsp130, were strongly downregulated in Twi morphants at LHB stage (Table 1). In addition, Twi morphants failed to stain with 1d5 for an extended period of time (compare Fig. 6H,J to G,I). These data show that Lvtwist functions upstream of the PMC skeletogenic differentiation program.

To identify potential upstream regulators of Lvtwist, we performed QPCR analyses with Alx1, Ets1 and Sna morphants at different stages (Table 2). At LHB and EMB stage, the expression of Lvtwist is reduced in Alx1 morphants, but not in either Ets1 or Sna morphants. At MB stage Lvtwist is downregulated in Sna morphants, but not Alx1 or Ets1 morphants. Note that endogenous twist mRNA expression level is temporarily low after ingression in control embryos which probably accounts for the lack of detection of a significant effect in Alx1 morphant at MB stage; while the downregulation of twist in Sna morphants is likely an indirect effect since snail expression starts to disappear around this time. These data, combined with results from Twist perturbations, suggest a dynamic regulation of Lvtwist as micromeres approach ingression.

Table 2.

Effects of PMC gene knockdown on expression level of Lvtwist measured by QPCR.

| Late HB | Early MB | MB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alx1MASO | -1.89, -2.31, NS | -3.03, -2.56/ -3.29 | NS, NS, NS/ NS/ NS/ -2.39/ -3.12 |

| SnaMASO | -1.57†/ NS, NS, NS | -2.63, -2.03/ NS, NS | NS, -2.53, -1.44†/ -5.06/ NS/ NS/ -3.29 |

| Est1MASO | NA | NS, NS, NS, NS | NA |

Data listed are considered significant, whereas non-significant effects (normalized CT difference from control is greater than −1.6 or less than +1.6) are shown as NS.

Commas separate replicate measurements in the same cDNA batch; The solidus separates different batches of cDNA from independent experiments.

Stages: HB (Hatched Blastula); MB (Mesenchyme Blastula).

This measurement, although below the significance, does exhibit the same trend of response to the perturbation as other samples.

LvTwist is necessary for PMC fusion and skeletogenesis

In Twi morphants, skeletogenesis is severely attenuated and never recovers but ingression eventually occurs and appearance of the 1D5 antigen eventually occurs. Normally, twist continues to be expressed following ingression so it could affect a series of functions leading to skeletogenesis. The next experiments attempted to determine which process(es) leading to skeletogenesis was/were disrupted.

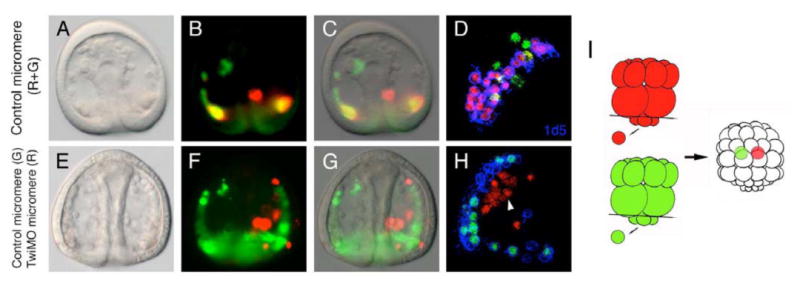

PMC filopodia undergo syncytial fusion to form a cable-like structure within which the spicules are subsequently secreted (Hodor and Ettensohn, 1998). Because PMC fusion and the formation of the filopodial cables are required for normal skeletogenesis, we hypothesized that Twist is required for PMC fusion. When extra PMCs are implanted into the blastocoel, they normally fuse with with endogenous PMCs (Ettensohn, 1990), To determine whether Twist is required for PMC fusion we transplanted two micromeres into the cavity of a 32- (or 60-) cell stage embryo to purposely include these micromeres as “ingressed” in the blastocoel and thereby bypass the PMC ingression process. The resulting chimeras with an “ectopic micromere” were shown in Figure 7. When two control micromeres (one in red, and one in green) were transplanted, progeny of both exhibited normal fusogenic behavior (Fig. 7A-C) and differentiation (as shown in 1d5 staining; Fig. 7D). However, when one TwiMASO-injected micromere (in red) and one control micromere (in green) were transplanted, as expected, the progeny of the normal micromere fused with endogenous PMCs, while most, if not all, the TwiMASO-micromere progeny failed to enter the syncytium with other PMCs (Fig. 7E-G), and did not stain with 1d5 (Fig. 7H). Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that Twist is required for PMC fusion, and therefore for developmental events upstream of skeletogenesis.

Fig. 7. Chimera embryos indicate that Twist activity is crucial in micromeres for proper PMC fusion.

(A-D) Transplanted PMCs derived from two control micromeres (shown in red and green) are equally capable of fusing with endogenous PMCs (no color) and express the MSP130 glycoprotein (D, shown by 1d5 staining in blue). (E-H) PMCs derived from a TwiMASO-injected micromere (red) fail to fuse properly with endogenous PMCs, while control micromere-derived PMCs (green) fuse normally and color the entire syncitium green. The 1d5 staining is absent in the TwiMASO-containing PMCs (H). The schematic diagram of the experimental designs of A to H is shown in I. See text for details.

Discussion

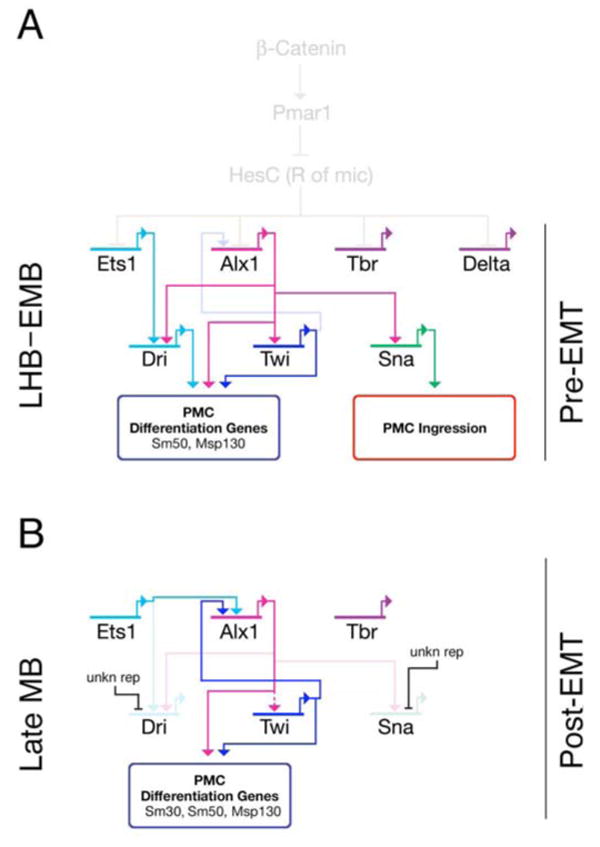

We show here that the twist gene is involved in executing several different functions in endomesoderm development during sea urchin embryogenesis. One of its functions is in sustaining PMC specification, which enables PMCs to undergo a complete EMT process and form the larval skeleton. The PMC phenotypes in Twi morphants occur as a consequence of incomplete specification and a failure of cell fate maintenance as well. Taking advantage of the sea urchin micromere-PMC GRN model, analysis of perturbations reveals a reciprocal relationship between Alx1 and Twist (Fig. 8), which likely accounts for at least part of the failure of PMCs to fully differentiate. Alx1 appears necessary for twist expression, and later Twist appears to feed back to positively regulate alx1 expression (Fig. 8). Alx1 has previously been shown to be an essential transcription factor for micromere-PMC specification (Ettensohn et al., 2003). As a consequence, if Twist is necessary as a positive feedback input to activate Alx1, as the data suggests, that loop then would be necessary to drive the network forward, and the progression of specification events leading to PMC fusion and skeletogenesis would be expected to falter in the Twist's absence which is exactly what is observed. Twist is also involved in SMC development, since in Twi morphants there are many fewer pigment cells, and muscle development is compromised, both of which are under-explored areas in sea urchin development. Taken together, like in other organisms, twist indeed plays a significant role in many aspects of mesoderm development in sea urchin embryos.

Fig. 8. The pre-EMT and post-EMT regulatory states in the PMC GRN.

(A) The PMC GRN before ingression. Alx1, Ets1, Tbr and Delta are all regulated by derepression of Pmar1, which is activated by the nuclear β-catenin. Pmar1 represses HesC allowing activation of the early micromere GRN (shown faded-out as events at earlier stages). Alx1 positively regulates Twi, Dri, and Sna. Ets1 also has a positive input on Dri. Both Twi and Dri activate downstream differentiation batteries (Msp130, Sm50). Snail controls PMC ingression through regulating Cadherin expression. Delta signals to adjacent veg2 cells through Notch to specify SMCs (not shown). (B) After PMC ingression is completed, the expression of Sna and Dri is downregulated from PMCs (by an unknown repression mechanism), while Alx1, Twi and other genes (not shown) continue to maintain the expression of PMC differentiation genes for the skeletogeneis at later stages. Twi feeds back to Alx1 to maintain its expression, and Ets1 also regulates Alx1 at this time. However, it is still uncertain if Alx1 regulates Twi at this stage. The Alx1-Twi reciprocal positive regulation may provide stabilities for the PMC GRN during PMC ingression.

Sea urchin Twist function is necessary for micromeres to undergo a complete EMT

Although the regulation of E-cadherin (loss of adhesion) is a central event during EMT, a complete EMT program also includes the acquisition of mesenchymal property and migratory ability (Boyer et al., 2000; Kang and Massague, 2004; Moustakas and Heldin, 2007). However, the pathways and genes characterize the mesenchymal differentiation emerging from epithelial precursors remain relatively under-explored. Several independent observations support the conclusion that sea urchin Twist may function as such as factor in regulating EMT but is not indispensable for the eventual occurrence of PMC ingression. First, functional knockdown of Twist with TwiMASO significantly delays but does not irreversibly block PMC ingression (Fig. 3). Second, Twist knockdown significantly obstructs the overall expression level of many PMC differentiation markers (Table 1), severely blocking expression of some and delaying expression of others. Third, the micromere-swap chimeric experiments demonstrate that Twist function is required autonomously in micromeres to complete EMT process in a timely and proper fashion (Fig. 5), since the TwiMASO-injected micromeres exhibit delayed ingression and disrupted migratory behaviors. Together, these data suggest that Twist is involved in controlling the specification state necessary for a properly regulated EMT process leading to a correctly migration pattern of PMCs.

In Drosophila mesoderm specification, Twist responds to Dorsal and in turn activates Snail expression, which establishes the molecular cascade leading to ventral furrow formation (Ip et al., 1992; Kosman et al., 1991). In addition, the relationship between Twist and Snail often is addressed in association with EMT events or tumor progressions, although the hierarchy remains uncertain (Kang and Massague, 2004; Peinado et al., 2007). Here, expression of twist and snail both rely on Alx1, but as yet, one cannot conclude on the relationship between these two proteins in the sea urchin embryos. Although a significant downregulation of snail occurs in Twi morphants at LHB stage as observed by QPCR (Table 1), the low prevalence of snail transcripts present at this stage (about 170 transcripts/embryo, or about 10 transcripts per micromere), makes it extremely difficult to distinguish between reliable data and QPCR artifact. Furthermore, in earlier experiments in the sea urchin, overexpression of an early micromere specifier, Pmar1, causes most of the embryo to be specified as PMCs and go through an EMT (Oliveri et al., 2003). Co-injection of the SnaMASO almost completely blocks this Pmar1-induced ectopic ingression (Wu and McClay, 2007). The TwiMASO on the other hand blocks ingression only in a low percentage of the embryos in the same co-injection experiment (data not shown), an outcome that would not be expected if Twist controlled snail expression in this experimental paradigm. Together, these data currently provide little strength for a direct regulatory interaction between Twist and Snail, and perturbation of snail fails to show it affecting expression of twist.

Several studies have shown that N-cadherin (a mesenchymal cell marker) is involved in tumor metastasis, motility and disruption of cell-cell adhesion (Hazan et al., 2000; Islam et al., 1996; Li et al., 2001; Nieman et al., 1999). Given the fact that Twist initiates the DN-cadherin expression during ventral furrow invagination in Drosophila (Oda et al., 1998), as well transcriptionally activating N-cadherin expression during metastasis (Alexander et al., 2006), it is possible that sea urchin Twist may engage a similar mechanism by activating new mesenchymal-specific adhesion molecules to modulate EMT process for acquiring migratory abilities. Indeed, molecules such as L1, as shown in breast carcinoma cells (Shtutman et al., 2006) or Cadherin-11 in Xenopus neural crest cells (Borchers et al., 2001) are activated in the EMT process in other systems. L1 and other cadherins are cloned or annotated in the sea urchin genome (Whittaker et al., 2006), so this hypothesis is testable in the future.

Twist function is required for maintaining the specification and differentiation of PMCs

Observations of PMC differentiation genes following Twist perturbation suggests that Twist is involved both in the activation of those genes and in the maintenance of their expression. PMC morphogenesis is progressively disrupted such that later events are affected more completely and irreversibly when Twist function is blocked. Skeletal rudiments, the endpoint of PMC differentiation, rarely appear in Twi morphants even after a prolonged culture period (Fig. 3E-E′,J-J′); while in those same embryos, TwiMASO delays ingression, compromises motility, and even more severely, impedes PMC fusion. The significant reduction of PMC-specific genes (msp130, sm50, sm30; Table 1) in Twi morphants further supports this function of Twist.

These data represent therefore a common property of gene regulatory networks where a single transcription factor is just one of many factors directed toward a particular sequence of events. In the absence of that factor, development does not halt entirely; instead, downstream events are progressively and increasingly compromised, or in other cases compensated for. Likely a progressive debilitation of early GRN states is why many mesoderm derivative tissues are affected in Twist-/- mutant mouse embryos. This is not always the case since some transcription factors (although not many) operate as a binary switch with devastating consequences when they are removed, such as prospero gene in Drosophila neural stem cells (Choksi et al., 2006). In the case of sea urchin Twist, which is present from pre-ingression to skeletogenesis, its absence leads to progressively accumulated failures during embryogenesis.

Differentiation genes in PMCs are regulated by different subcircuits and activated at different times. Thus, there is no surprise that sm50 and msp130, although both are PMC differentiation genes, are differentially impacted by Twist knockdown. In Twi morphants, sm50 is strongly downregulated at both the LHB and MB stages, while msp130 is only affected at MB stage (Table 1). Similar observations have been reported for the same genes, which respond differently when VEGF signaling is perturbed (Duloquin et al., 2007).

In the micromere-PMC GRN, alx1 and ets1 are transcription factors involved in early specification and activation of many downstream PMC genes. When the regulatory relationships between these two genes and twist were examined by QPCR and WMISH, alx1 mRNA expression was downregulated in Twi morphants, while the expression of ets1 was not affected (Table 1; Fig. 7). Considering that twist mRNA accumulates after the initiation of alx1 expression, which is around the 16- to 32-cell stage, Twist must be involved in the maintenance of alx1 expression rather than its initial activation. Knockdown of Alx1 strongly reduces twist expression (Table 1), suggesting that alx1 functions as a positive regulator upstream of twist. This reciprocal regulatory relationship suggests the existence of the proposed positive-feedback loop involving Alx1 and Twist, in Figure 8. Thus Twist seems to participate in a subcircuit with Alx1 that spans both pre- and post-EMT PMC regulatory network states (Fig. 8). However, whether this mutually positive regulation is due to direct intergenic inputs will requires further examination to confirm the relationship, such as cis-regulatoy analyses. In fact, a positive-feedback loop is a common regulatory strategy utilized in many developmental GRNs (Davidson, 2006) to stabilize and feed forward a particular specification state or cell territory; for example, the conserved Otxβ-GataE positive-feedback loop maintains the expression of key endodermal regulatory genes in both the sea urchin and the starfish (Hinman et al., 2003; Yuh et al., 2004), and several positive-feedback loops have been shown to take place during mesendoderm formation in Xenopus embryos (Loose and Patient, 2004), and elsewhere. These feedback loops keep regulatory states in an “on” position and implement stable phases in gene network states, which, in this case allow cellular differentiation and morphogenesis to occur.

At late MB stage, snail expression disappears from completely ingressed PMCs and it is similar to the expression pattern of dri (Amore et al., 2003). However, what genes are involved in their downregulation still remains unknown. It has been shown that Drosophila WntD is feedback inhibitor of the Dorsal/Twist/Snail network in the gastrulating embryo (Ganguly et al., 2005; Gordon et al., 2005). Thus in the sea urchin embryo, it is possible that a similar inhibiting signal or a transcriptional repressor is activated immediately after PMCs ingress and represses genes, including snail, which are not required in the post-ingression PMC GRN. Answers to these issues will require further investigation, but they are guided by the predictions of the network.

Twist as an evolutionarily conserved modulator for mesoderm development

In this study, Twist clearly is involved in a subcircuit prior to PMC differentiation and its absence progressively affects downstream skeletogenic development. However, our analysis here does not identify additional downstream targets (such as transcription factors) of Twist, other than its regulatory relationship with Alx1. Since sea urchin Twist and other Twist family members in all metazoans examined to date have been demonstrated or implicated to have a common role in mesoderm specification and differentiation implying a deep evolutionary conservation, it is possible that conservation of other downstream targets of Twist also exist. For example, in C. elegans, the promoters of two genes, NK-class homeodomain (ceh-24) and FGFR-like genes (egl-15) contain the Twist E-box consensus sequence (Twist-binding site) and it has been demonstrated in vivo that CeTwist regulates these genes (Harfe and Fire, 1998). In Drosophila, activation of tinman and heartless, the homologues of the ceh-24 and egl-15 genes, respectively, require Twist early in embryogenesis (Beiman et al., 1996; Bodmer, 1993; Gisselbrecht et al., 1996; Shishido et al., 1993; Yin et al., 1997). In sea urchins, an NK-class homeodomain gene, Hex (Howard-Ashby et al., 2006a), and FGFR1 (Lapraz et al., 2006) are both expressed in PMCs and SMCs (among other territories). Given the role of Twist in mesoderm development, it is highly plausible that these two genes (among several others) are regulated by Twist, although detailed investigation is needed and will follow.

Interestingly, recent whole-genome analyses of Twist protein downstream binding targets in Drosophila reveals surprising and major roles for Twist in the regulation of gene batteries involving different hierarchal levels of mesoderm development (Sandmann et al., 2007; Zeitlinger et al., 2007). These studies further suggest that Twist functions as a global competence factor for mesoderm development (Sandmann et al., 2007), which may allow more specialized downstream transcription factors to function. The data in this study shows the possibility of how Twist participates in the temporally dynamic PMC GRN as such a factor during sea urchin embryogenesis.

Supplementary Material

(A) The control embryo at 72 hpf shows normal pigment cell number. (B-C) Two Twi morphants shows no pigment cells in the epithelium.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ho-Kyung Rho for her help in performing QPCR analyses. This work was funded by NIH GM61464 and by HD14483 to DRM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander NR, Tran NL, Rekapally H, Summers CE, Glackin C, Heimark RL. N-cadherin gene expression in prostate carcinoma is modulated by integrin-dependent nuclear translocation of Twist1. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3365–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amore G, Yavrouian RG, Peterson KJ, Ransick A, McClay DR, Davidson EH. Spdeadringer, a sea urchin embryo gene required separately in skeletogenic and oral ectoderm gene regulatory networks. Dev Biol. 2003;261:55–81. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylies MK, Bate M. twist: a myogenic switch in Drosophila. Science. 1996;272:1481–4. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiman M, Shilo BZ, Volk T. Heartless, a Drosophila FGF receptor homolog, is essential for cell migration and establishment of several mesodermal lineages. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2993–3002. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer R. The gene tinman is required for specification of the heart and visceral muscles in Drosophila. Development. 1993;118:719–29. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers A, David R, Wedlich D. Xenopus cadherin-11 restrains cranial neural crest migration and influences neural crest specification. Development. 2001;128:3049–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois P, Bolcato-Bellemin AL, Danse JM, Bloch-Zupan A, Yoshiba K, Stoetzel C, Perrin-Schmitt F. The variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance of the twist-null heterozygous mouse phenotype resemble those of human Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:945–57. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer B, Valles AM, Edme N. Induction and regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1091–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanon I, Baylies MK. A Twist in fate: evolutionary comparison of Twist structure and function. Gene. 2002;287:11–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00893-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZF, Behringer RR. twist is required in head mesenchyme for cranial neural tube morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:686–99. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choksi SP, Southall TD, Bossing T, Edoff K, de Wit E, Fischer BE, van Steensel B, Micklem G, Brand AH. Prospero acts as a binary switch between self-renewal and differentiation in Drosophila neural stem cells. Dev Cell. 2006;11:775–89. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi AK, Kostas SA, Fire A, Krause M. Caenorhabditis elegans twist plays an essential role in non-striated muscle development. Development. 2000;127:2041–51. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.10.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripps RM, Olson EN. Twist is required for muscle template splitting during adult Drosophila myogenesis. Dev Biol. 1998;203:106–15. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambly-Chaudiere C, Vervoort M. The bHLH genes in neural development. Int J Dev Biol. 1998;42:269–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH. Lineage-specific gene expression and the regulative capacities of the sea urchin embryo: a proposed mechanism. Development. 1989;105:421–45. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH. The Regulatory Genome. Academic Press; San Diego: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH, Cameron RA, Ransick A. Specification of cell fate in the sea urchin embryo: summary and some proposed mechanisms. Development. 1998;125:3269–90. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH, Rast JP, Oliveri P, Ransick A, Calestani C, Yuh CH, Minokawa T, Amore G, Hinman V, Arenas-Mena C, Otim O, Brown CT, Livi CB, Lee PY, Revilla R, Rust AG, Pan Z, Schilstra MJ, Clarke PJ, Arnone MI, Rowen L, Cameron RA, McClay DR, Hood L, Bolouri H. A genomic regulatory network for development. Science. 2002;295:1669–78. doi: 10.1126/science.1069883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duloquin L, Lhomond G, Gache C. Localized VEGF signaling from ectoderm to mesenchyme cells controls morphogenesis of the sea urchin embryo skeleton. Development. 2007;134:2293–302. doi: 10.1242/dev.005108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Ghouzzi V, Le Merrer M, Perrin-Schmitt F, Lajeunie E, Benit P, Renier D, Bourgeois P, Bolcato-Bellemin AL, Munnich A, Bonaventure J. Mutations of the TWIST gene in the Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15:42–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettensohn CA. The regulation of primary mesenchyme cell patterning. Dev Biol. 1990;140:261–71. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90076-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettensohn CA, Illies MR, Oliveri P, De Jong DL. Alx1, a member of the Cart1/Alx3/Alx4 subfamily of Paired-class homeodomain proteins, is an essential component of the gene network controlling skeletogenic fate specification in the sea urchin embryo. Development. 2003;130:2917–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.00511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchikami T, Mitsunaga-Nakatsubo K, Amemiya S, Hosomi T, Watanabe T, Kurokawa D, Kataoka M, Harada Y, Satoh N, Kusunoki S, Takata K, Shimotori T, Yamamoto T, Sakamoto N, Shimada H, Akasaka K. T-brain homologue (HpTb) is involved in the archenteron induction signals of micromere descendant cells in the sea urchin embryo. Development. 2002;129:5205–16. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.22.5205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A, Jiang J, Ip YT. Drosophila WntD is a target and an inhibitor of the Dorsal/Twist/Snail network in the gastrulating embryo. Development. 2005;132:3419–29. doi: 10.1242/dev.01903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselbrecht S, Skeath JB, Doe CQ, Michelson AM. heartless encodes a fibroblast growth factor receptor (DFR1/DFGF-R2) involved in the directional migration of early mesodermal cells in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3003–17. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MD, Dionne MS, Schneider DS, Nusse R. WntD is a feedback inhibitor of Dorsal/NF-kappaB in Drosophila development and immunity. Nature. 2005;437:746–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD, Vaz Gomes A, Kenyon C, Liu J, Krause M, Fire A. Analysis of a Caenorhabditis elegans Twist homolog identifies conserved and divergent aspects of mesodermal patterning. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2623–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan RB, Phillips GR, Qiao RF, Norton L, Aaronson SA. Exogenous expression of N-cadherin in breast cancer cells induces cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:779–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman VF, Nguyen AT, Cameron RA, Davidson EH. Developmental gene regulatory network architecture across 500 million years of echinoderm evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13356–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235868100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjalt T. Basic helix-loop-helix proteins expressed during early embryonic organogenesis. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;236:251–80. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)36006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodor PG, Ettensohn CA. The dynamics and regulation of mesenchymal cell fusion in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol. 1998;199:111–24. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard TD, Paznekas WA, Green ED, Chiang LC, Ma N, Ortiz de Luna RI, Garcia Delgado C, Gonzalez-Ramos M, Kline AD, Jabs EW. Mutations in TWIST, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, in Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15:36–41. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Ashby M, Materna SC, Brown CT, Chen L, Cameron RA, Davidson EH. Identification and characterization of homeobox transcription factor genes in Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, and their expression in embryonic development. Dev Biol. 2006a;300:74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Ashby M, Materna SC, Brown CT, Chen L, Cameron RA, Davidson EH. Gene families encoding transcription factors expressed in early development of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Dev Biol. 2006b;300:90–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip YT, Park RE, Kosman D, Yazdanbakhsh K, Levine M. dorsal-twist interactions establish snail expression in the presumptive mesoderm of the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1518–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam S, Carey TE, Wolf GT, Wheelock MJ, Johnson KR. Expression of N-cadherin by human squamous carcinoma cells induces a scattered fibroblastic phenotype with disrupted cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1643–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Massague J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: twist in development and metastasis. Cell. 2004;118:277–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katow H, Solursh M. Ultrastructure of Primary Mesenchyme Cell Ingression in the Sea-Urchin Lytechinus-Pictus. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1980;213:231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Kosman D, Ip YT, Levine M, Arora K. Establishment of the mesoderm-neuroectoderm boundary in the Drosophila embryo. Science. 1991;254:118–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1925551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa D, Kitajima T, Mitsunaga-Nakatsubo K, Amemiya S, Shimada H, Akasaka K. HpEts, an ets-related transcription factor implicated in primary mesenchyme cell differentiation in the sea urchin embryo. Mech Dev. 1999;80:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapraz F, Rottinger E, Duboc V, Range R, Duloquin L, Walton K, Wu SY, Bradham C, Loza MA, Hibino T, Wilson K, Poustka A, McClay D, Angerer L, Gache C, Lepage T. RTK and TGF-beta signaling pathways genes in the sea urchin genome. Dev Biol. 2006;300:132–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leptin M. twist and snail as positive and negative regulators during Drosophila mesoderm development. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1568–76. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Satyamoorthy K, Herlyn M. N-cadherin-mediated intercellular interactions promote survival and migration of melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3819–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loose M, Patient R. A genetic regulatory network for Xenopus mesendoderm formation. Dev Biol. 2004;271:467–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martindale MQ, Pang K, Finnerty JR. Investigating the origins of triploblasty: ‘mesodermal’ gene expression in a diploblastic animal, the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis (phylum, Cnidaria; class, Anthozoa) Development. 2004;131:2463–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.01119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClay DR, Armstrong NA, Hardin J. Pattern formation during gastrulation in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Suppl. 1992:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Signaling networks guiding epithelial-mesenchymal transitions during embryogenesis and cancer progression. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1512–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C, McCaw PS, Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989;56:777–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemer M, Rondinelli E, Infante D, Infante AA. Polyubiquitin RNA characteristics and conditional induction in sea urchin embryos. Dev Biol. 1991;145:255–65. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90124-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman MT, Prudoff RS, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ. N-cadherin promotes motility in human breast cancer cells regardless of their E-cadherin expression. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:631–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke MP, Soo K, Behringer RR, Hui CC, Tam PP. Twist plays an essential role in FGF and SHH signal transduction during mouse limb development. Dev Biol. 2002;248:143–56. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda H, Tsukita S, Takeichi M. Dynamic behavior of the cadherin-based cell-cell adhesion system during Drosophila gastrulation. Dev Biol. 1998;203:435–50. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri P, Carrick DM, Davidson EH. A regulatory gene network that directs micromere specification in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol. 2002;246:209–28. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri P, Davidson EH, McClay DR. Activation of pmar1 controls specification of micromeres in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol. 2003;258:32–43. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otim O, Amore G, Minokawa T, McClay DR, Davidson EH. SpHnf6, a transcription factor that executes multiple functions in sea urchin embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 2004;273:226–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransick A, Davidson EH. A complete second gut induced by transplanted micromeres in the sea urchin embryo. Science. 1993;259:1134–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8438164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransick A, Davidson EH. cis-regulatory processing of Notch signaling input to the sea urchin glial cells missing gene during mesoderm specification. Dev Biol. 2006;297:587–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revilla-i-Domingo R, Oliveri P, Davidson EH. A missing link in the sea urchin embryo gene regulatory network: hesC and the double-negative specification of micromeres. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12383–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705324104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosivatz E, Becker I, Specht K, Fricke E, Luber B, Busch R, Hofler H, Becker KF. Differential expression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulators snail, SIP1, and twist in gastric cancer. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1881–91. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottinger E, Besnardeau L, Lepage T. A Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway is required for development of the sea urchin embryo micromere lineage through phosphorylation of the transcription factor Ets. Development. 2004;131:1075–87. doi: 10.1242/dev.01000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandmann T, Girardot C, Brehme M, Tongprasit W, Stolc V, Furlong EE. A core transcriptional network for early mesoderm development in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 2007;21:436–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.1509007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood DR, McClay DR. LvNotch signaling mediates secondary mesenchyme specification in the sea urchin embryo. Development. 1999;126:1703–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishido E, Higashijima S, Emori Y, Saigo K. Two FGF-receptor homologues of Drosophila: one is expressed in mesodermal primordium in early embryos. Development. 1993;117:751–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtutman M, Levina E, Ohouo P, Baig M, Roninson IB. Cell adhesion molecule L1 disrupts E-cadherin-containing adherens junctions and increases scattering and motility of MCF7 breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11370–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P. Maternal-Zygotic Gene Interactions during Formation of the Dorsoventral Pattern in Drosophila Embryos. Genetics. 1983;105:615–632. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.3.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Davidson EH, Cameron RA, Gibbs RA, Angerer RC, Angerer LM, Arnone MI, Burgess DR, Burke RD, Coffman JA, Dean M, Elphick MR, Ettensohn CA, Foltz KR, Hamdoun A, Hynes RO, Klein WH, Marzluff W, McClay DR, Morris RL, Mushegian A, Rast JP, Smith LC, Thorndyke MC, Vacquier VD, Wessel GM, Wray G, Zhang L, Elsik CG, Ermolaeva O, Hlavina W, Hofmann G, Kitts P, Landrum MJ, Mackey AJ, Maglott D, Panopoulou G, Poustka AJ, Pruitt K, Sapojnikov V, Song X, Souvorov A, Solovyev V, Wei Z, Whittaker CA, Worley K, Durbin KJ, Shen Y, Fedrigo O, Garfield D, Haygood R, Primus A, Satija R, Severson T, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Jackson AR, Milosavljevic A, Tong M, Killian CE, Livingston BT, Wilt FH, Adams N, Belle R, Carbonneau S, Cheung R, Cormier P, Cosson B, Croce J, Fernandez-Guerra A, Geneviere AM, Goel M, Kelkar H, Morales J, Mulner-Lorillon O, Robertson AJ, Goldstone JV, Cole B, Epel D, Gold B, Hahn ME, Howard-Ashby M, Scally M, Stegeman JJ, Allgood EL, Cool J, Judkins KM, McCafferty SS, Musante AM, Obar RA, Rawson AP, Rossetti BJ, Gibbons IR, Hoffman MP, Leone A, Istrail S, Materna SC, Samanta MP, Stolc V, Tongprasit W, et al. The genome of the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Science. 2006;314:941–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1133609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soo K, O'Rourke MP, Khoo PL, Steiner KA, Wong N, Behringer RR, Tam PP. Twist function is required for the morphogenesis of the cephalic neural tube and the differentiation of the cranial neural crest cells in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2002;247:251–70. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring J, Yanze N, Middel AM, Stierwald M, Groger H, Schmid V. The mesoderm specification factor twist in the life cycle of jellyfish. Dev Biol. 2000;228:363–75. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet HC, Gehring M, Ettensohn CA. LvDelta is a mesoderm-inducing signal in the sea urchin embryo and can endow blastomeres with organizer-like properties. Development. 2002;129:1945–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, el Messal M, Perrin-Schmitt F. The twist gene: isolation of a Drosophila zygotic gene necessary for the establishment of dorsoventral pattern. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3439–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.8.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker CA, Bergeron KF, Whittle J, Brandhorst BP, Burke RD, Hynes RO. The echinoderm adhesome. Dev Biol. 2006;300:252–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, McClay DR. The Snail repressor is required for PMC ingression in the sea urchin embryo. Development. 2007;134:1061–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.02805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui K, Zhang SC, Uemura M, Aizawa S, Ueki T. Expression of a twist-related gene, Bbtwist, during the development of a lancelet species and its relation to cephalochordate anterior structures. Dev Biol. 1998;195:49–59. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z, Xu XL, Frasch M. Regulation of the twist target gene tinman by modular cis-regulatory elements during early mesoderm development. Development. 1997;124:4971–82. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuh CH, Dorman ER, Howard ML, Davidson EH. An otx cis-regulatory module: a key node in the sea urchin endomesoderm gene regulatory network. Dev Biol. 2004;269:536–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlinger J, Zinzen RP, Stark A, Kellis M, Zhang H, Young RA, Levine M. Whole-genome ChIP-chip analysis of Dorsal, Twist, and Snail suggests integration of diverse patterning processes in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 2007;21:385–90. doi: 10.1101/gad.1509607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga A, Quillet R, Perrin-Schmitt F, Zeller R. Mouse Twist is required for fibroblast growth factor-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal signalling and cell survival during limb morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2002;114:51–9. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) The control embryo at 72 hpf shows normal pigment cell number. (B-C) Two Twi morphants shows no pigment cells in the epithelium.