Abstract

Ion mobility spectrometry coupled with mass spectrometry (IMS-MS) was utilized to evaluate an ion collision energy ramping technique that simultaneously fragments a variety of species. To evaluate this technique, the fragmentation patterns of a mixture of ions ranging in mass, charge state and drift time were analyzed to determine their optimal fragmentation conditions. The precursor ions were pulsed into the IMS-MS instrument and separated in the IMS drift cell based on mobility differences. Two differentially pumped short quadrupoles were used to focus the ions exiting the drift cell, and fragmentation was induced by collision induced dissociation (CID) between the conductance limiting orifice behind the second short quadrupole and before the first octopole in the mass spectrometer. To explore the fragmentation spectrum of each precursor ion, the bias voltages for the short quadrupoles and conductance limiting orifices were increased from 0 V to 50 V above non-fragmentation voltage settings. An approximately linear correlation was observed between the optimal fragmentation voltage for each ion and its specific drift time, so a linear voltage gradient was employed to supply less collision energy to high mobility ions (e.g., small conformations or higher charge state ions) and more to low mobility ions. Fragmentation efficiencies were found to be similar for different ions when the fragmentation voltage was linearly ramped with drift time, but varied drastically when only a single voltage was used.

Keywords: Ion mobility spectrometry, IMS-MS, IMS-MS fragmentation

Introduction

Analyzing complex biological samples with mass spectrometry (MS) and tandem MS techniques1,2 has aided in the acquisition of important structural information for many different types of ions, including peptides,3,4 proteins,5,6 lipids,7,8 and carbohydrates.9,10 While tandem MS has successfully been applied to a range of difficult sequence and structural problems,11,12 its application to highly complex samples has been limited by the general need for the selection of specific precursor species for each fragmentation experiment. This allows the fragment ions to be correctly assigned to their corresponding precursor ion in a mixture, but creates a severe MS “under sampling” problem in untargeted analyses especially for online liquid chromatography (LC)-MS examinations of small volume samples. Developing methods to simultaneously fragment all ions in a complex sample is very appealing; however, difficulties arise because distinct species generally require differing amounts of collisional excitation depending on their mass,13 charge state,14 and structure.15,16 Typically, if only one collision energy is utilized, both under-fragmentation and over-fragmentation (which corresponds to the sequential dissociation of the initial higher m/z dissociation products to yield often less informative lower m/z products) contribute excessively in the acquired spectrum.

Multiplexed MS/MS approaches, which dissociate multiple ions simultaneously, have been studied to increase the throughput of LC-MS/MS runs. Currently, these approaches either use a single collision energy for fragmentation17,18 or alternate between a low and high collision energy (MSE).19 Since both fragmentation approaches are unable to optimize the collision energy of the different ions in the mixture, under- and over-fragmentation occur in the acquired spectra. Another consequence of fragmenting multiple ions simultaneously with multiplexed MS/MS is that the connectivity information between the parent and fragment ions is lost, and while computational approaches can attempt to determine such relationships, their success is determined by data quality, mixture complexity, and the similarity of the species being dissociated. A different strategy for fragmenting mixtures of ions concurrently, while largely maintaining the connectivity information between the precursor and corresponding fragments, is to couple ion mobility spectrometry with mass spectrometry (IMS-MS).20,21,22 In 2000, Hoaglund-Hyzer et al.23 showed that if ions are fragmented after the IMS drift cell and directly before MS analysis, the precursor ions have the same drift time as their corresponding fragment ions. This event is possible because the precursor ions are first separated in the IMS drift cell based on conformation and charge state, which establishes their drift time. Fragmentation takes place after the IMS drift cell and directly before m/z analysis, allowing the same transient time from the ion fragmentation region to the MS detector for both precursor and fragment ions.24,25 Koeniger et al.26 further extended this approach to obtain multiple stages of IMS and collisional activation. In their IMS-IMS-MS experiments, the precursor ions first disperse through an IMS drift cell, and directly after, an ion of specific mobility was selected for collisional activation. After activation, the fragments formed were separated in a second drift cell before MS analysis, which allowed the acquisition of fragment ion structural information. This method is similar to MS/MS with the exception that the precursor is selected based on its cross section-to-charge (Ω/z) ratio rather than its m/z ratio.27

IMS-MS and IMS-IMS-MS show great potential for analyzing complex samples. However, the complex mixture must initially be correctly dissociated or both over- and under-fragmentation will occur in the spectrum due to the broad range of m/z and collision cross section values. In 2005, Koeniger et al. showed that they could achieve optimum fragmentation conditions for either (M+2H)2+ or (M+3H)3+ ions in their IMS-MS experiments by alternating between two different CID voltages.25 Their method, however, reduces the duty cycle of the fragmentation experiments since two CID spectra (one at a low voltage and one at a high voltage) are required for each sample. In this paper, we introduce a method to increase the duty cycle of IMS-MS fragmentation experiments by optimizing the dissociation energy of all components of a mixture in one CID spectrum. Since different drift times occur for ions with distinct structures in IMS, we monitored a peptide mixture and tryptic digest of bovine serum albumin (BSA) to determine the general relationship between fragmentation voltage and peptide ion drift time. This analysis showed that the optimal fragmentation voltage was approximately proportional to the drift time of each ion. Herein, we linearly ramped the fragmentation voltage as a function of IMS drift time and the IMS-MS nested spectra and fragmentation efficiencies from the linear voltage gradient are presented and compared to a constant fragmentation voltage.

Experimental Methods

Materials

Bradykinin (B3259), angiotensin I (A9650), neurotensin (N6383), fibrinopeptide A (F3254), and BSA (A7638) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) and used without further purification. A 4-peptide mixture was prepared by diluting bradykinin, angiotensin I, neurotensin, and fibrinopeptide A separately to a concentration of 10 μM in a 49.9:49.9:0.2 water/methanol/acetic acid solution. The four peptides were then combined to yield a concentration of 1 μM each. A BSA tryptic digestion was performed following previously reported procedures28 and the sample was then diluted to a final concentration of 0.05 mg/mL in the 49.9:49.9:0.2 water/methanol/acetic acid solution. All samples were ionized in positive electrospray ionization (ESI) mode with a bias voltage of 2.6 kV, and directly infused at a flow rate of 300 nL/min.

Instrumentation

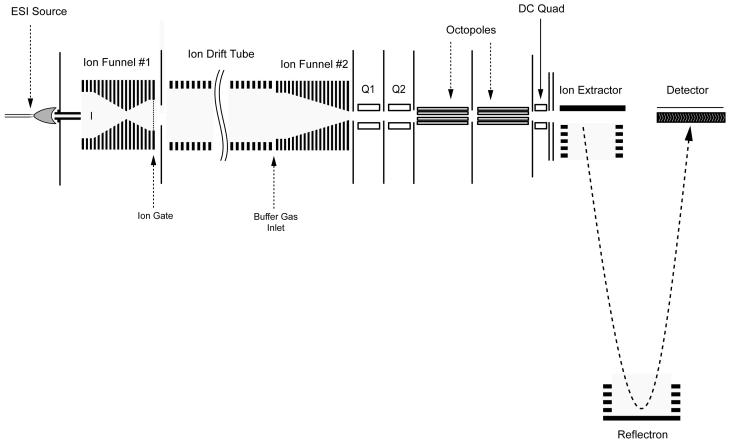

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the ESI-IMS-time-of flight (TOF) MS instrument used for these studies. As a detailed description of this instrument is given elsewhere,29 only a brief discussion follows. The sample solutions were electrosprayed using a chemically etched 20-μm inner diameter fused-silica emitter30 and the plume sampled using a 64-mm long heated capillary inlet.31 Once through the heated capillary, the ions were transmitted into a high pressure hourglass ion funnel,32,33 which focuses the ion bean exiting the capillary and traps the ions, converting the continuous ion beam from the ESI source into a discrete short ion pulse for mobility measurements. Ions were ejected from the ion funnel and passed into the drift cell filled with 4.0 Torr ultra-pure nitrogen buffer gas by pulsing the high-transmission ion gate 2 mm behind the last ion funnel electrode for 100 μs. The time between pulses was 50 ms for all samples analyzed in this paper.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the ESI-IMS-TOF MS. The DC voltages in both Q1 and Q2 are ramped linearly as a function of drift time to create optimum collision energy for each ion.

Once in the 98-cm long drift cell,32 the ions drift through the buffer gas under a weak, uniform electric field (E; ∼16 V/cm). The ions quickly reach equilibrium between the forward acceleration force imposed by the electric field and the frictional drag force from the buffer gas. As a consequence, the ions drift at constant velocity (vd) proportional to the applied field E, 34

| (1) |

where the proportionality constant K is termed the mobility of the ions. As the ions exit the drift cell, they are refocused by the rear ion funnel and transmitted through two differentially pumped short quadrupole chambers (Q1 and Q2 in Figure 1). The lengths of Q1 and Q2 are 3.5 cm and 2.3 cm, respectively. The pressure in Q2’s chamber was maintained at 170 mTorr to minimize the ion transient time between the drift cell and the TOF detector. Two DC-only conductance limit electrodes with 2.5 mm apertures separate Q1, Q2, and the first octopole of the TOF MS. The distance between Q2 and its following conductance limit electrode (Q2 CL) is 1.5 mm. The distance between Q2 CL and the entrance of the 1st octopole is 2 mm. The bias voltages applied to Q1, the Q1 CL, Q2, and the Q2 CL were set at 68 V, 63 V, 48 V and 43 V. These four voltages were linearly ramped as a function of drift time in the fragmentation experiments to cause collision induced dissociation (CID) between the conductance limiting orifice behind the second short quadrupole and before the first octopole, which was at a pressure of ∼4×10-4 Torr. To perform fragmentation experiments, the four voltages were connected to four independent summing amplifiers. Each amplifier summed two voltage inputs on the fly to allow alternating precursor and fragment ion spectra acquisition. The first voltage input for the amplifier was a static voltage used for precursor ion spectra acquisition, while the second voltage input, common to all four amplifiers, was a scan voltage controlled by the data acquisition software. For the acquisition of precursor ion spectra, the scan voltage was set to zero, however, if fragmentation was desired, it could be set to any function (flat, linear, etc) defined by the user. An orthogonal acceleration (oa)-TOF MS (Agilent Technologies) was utilized for accurate m/z measurements of the mobility separated ions and a time-to-digital converter (TDC) recorded the ion counts (Ortec Specifications). A detailed description of the instrumental control software and data acquisition scheme has been previously reported.32

Results and Discussion

A 4-peptide mixture of angiotensin I, bradykinin, fibrinopeptide A, and neurotensin at a concentration of 1 μM each was used to initially investigate the experimental conditions necessary for high efficiency fragmentation of a mixture. However, before fragmenting the mixture, it was important to understand the ions present in the precursor spectrum and the experimental conditions required for its acquisition. To acquire the precursor IMS-MS spectrum for the 4-peptide mixture, the DC voltages for Q1, Q1 CL, Q2, and Q2 CL were set to 68 V, 63 V, 48 V, and 43 V, respectively, for optimum ion transmission (shown in black in Figure 2a). These values were also selected so that the ions did not have enough energy to fragment as they entered octopole 1. When fragmentation was desired, voltages for the quadrupole regions were increased, which raised the collision energy of the ions entering octopole 1. The ions observed in the precursor spectrum are listed in Table 1 along with their corresponding m/z values and average drift times in nitrogen buffer gas. Since these ions are present over a range of masses, charge states, and drift times (between 20-40 ms is typical in complex mixtures), their fragmentation information aids in understanding the conditions necessary for optimal fragmentation of a more complex mixture of ions.

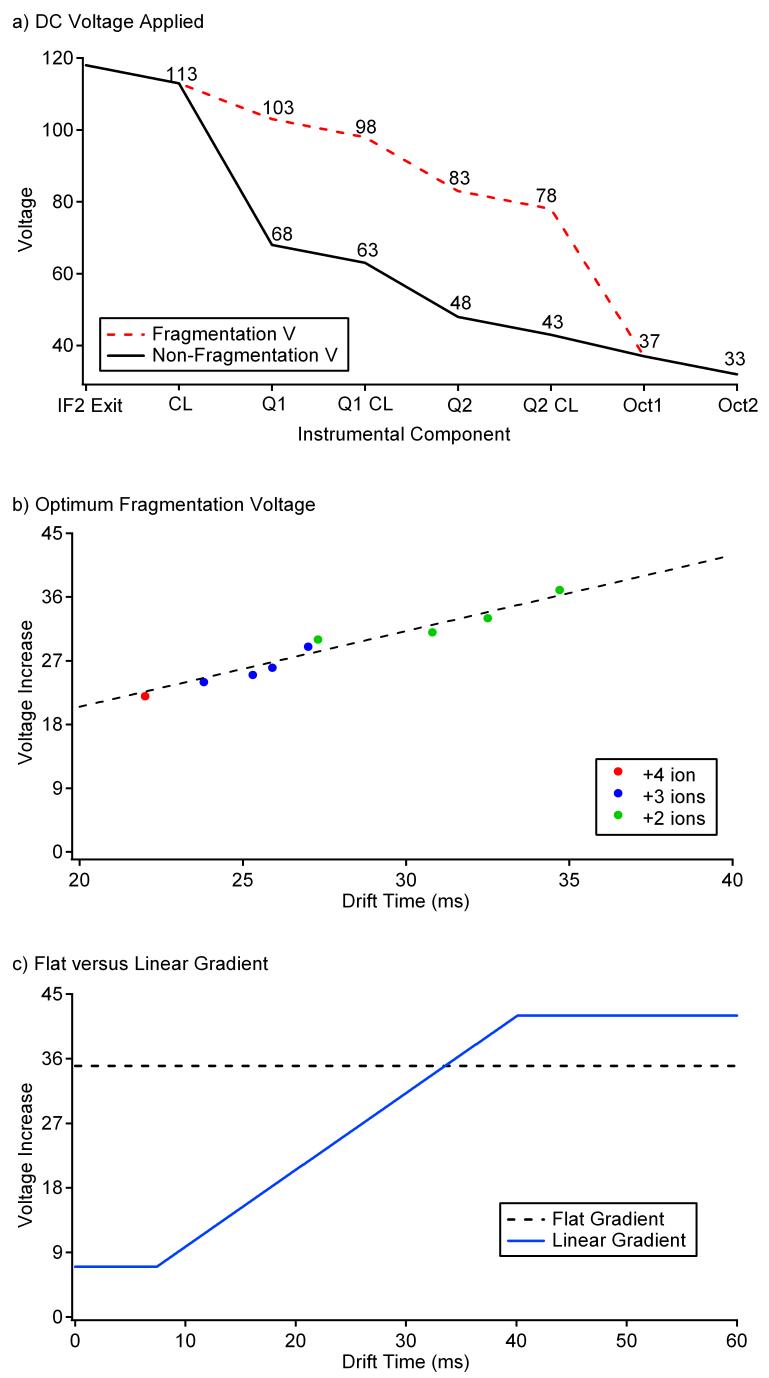

Figure 2.

a) The DC voltage applied to each component after the drift cell during normal operation (solid line) and fragmentation (dotted line) when 35 V is applied. During the linear fragmentation gradient, the fragmentation voltage (in red changes) changes based on drift time. IF2 is the abbreviation for ion funnel 2, CL is conductance limit, Q is for quadrupole and Oct stands for octopole. b) A plot of the optimum fragmentation voltage required for each ion in the 4 peptide mixture. c) The voltage increase as a function of drift time for Q1, Q1 CL, Q2 and Q2 CL when a flat (dotted line) or linear (solid line) fragmentation gradient is applied to the quadrupole regions.

Table 1.

Precursor Ions Present in the 4-Peptide Mixture

| m/za | Drift timeb | |

|---|---|---|

| (Angiotensin I)4+ | 324.927 | 22.0 |

| (Angiotensin I)3+ | 432.900 | 25.3 |

| (Angiotensin I)2+ | 648.847 | 30.8 |

| (Bradykinin)3+ | 354.195 | 23.8 |

| (Bradykinin)2+ | 530.789 | 27.3 |

| (Fibrinopeptide A)3+ | 512.903 | 25.9 |

| (Fibrinopeptide A)2+ | 768.850 | 32.5 |

| (Neurotensin)3+ | 558.311 | 27.0 |

| (Neurotensin)2+ | 836.963 | 34.7 |

Calculated exact mass to three decimal places

Average drift time in milliseconds at 4 Torr, 16 V/cm, and 298 K

The four voltages in the quadrupole regions were raised concurrently from non-fragmentation conditions to 50 V above, and spectra were taken every 2 V to determine the voltage required to fragment components observed from the 4-peptide mixture. Fragmentation settings are shown in red in Figure 2a for a 35 V increase above non-fragmentation conditions. As optimum fragmentation for the 4-peptide mixture was considered to be the preservation of ∼5-10% of the parent ions, the spectra taken every 2 V were analyzed carefully to determine the most favorable fragmentation voltage range for each ion. These spectra revealed that the optimum fragmentation voltage increases with ion drift time (Figure 2b). As a result, short drift time ions reach optimum fragmentation conditions at low fragmentation voltages, while long drift time ions do not start fragmenting until higher fragmentation voltages are applied; however, these higher voltages over-fragment the short drift time ions.25 The optimal fragmentation voltage for each ion was plotted versus its drift time, and the resulting plot shown in Figure 2b illustrates that the fragmentation voltage linearly increased as a function of ion drift time. A linear fragmentation gradient was constructed from this data as shown by the blue line in Figure 2c. Since the maximum voltage necessary to fragment all the ions in the mixture was less than 40 V, the linear gradient was flattened to 42 V for drift times past 40 ms and a flat gradient of 7 V was used initially from 0 to 8 ms (where only very small ions, typically not observed in our application, would be expected).

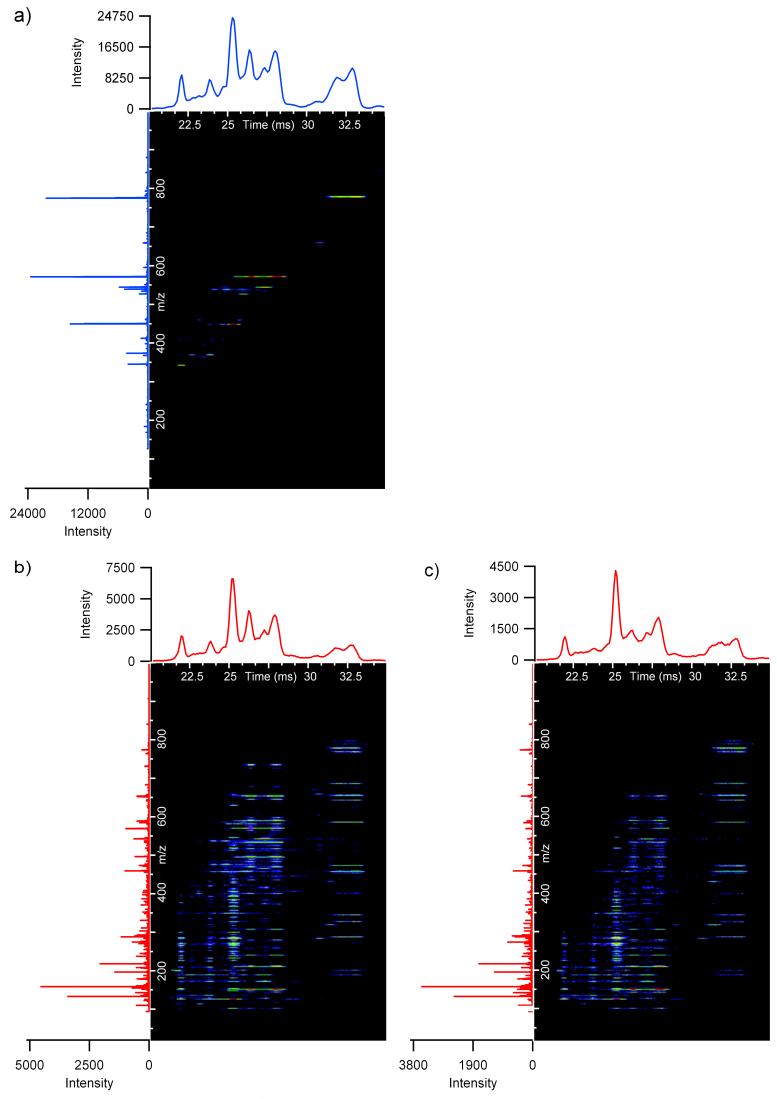

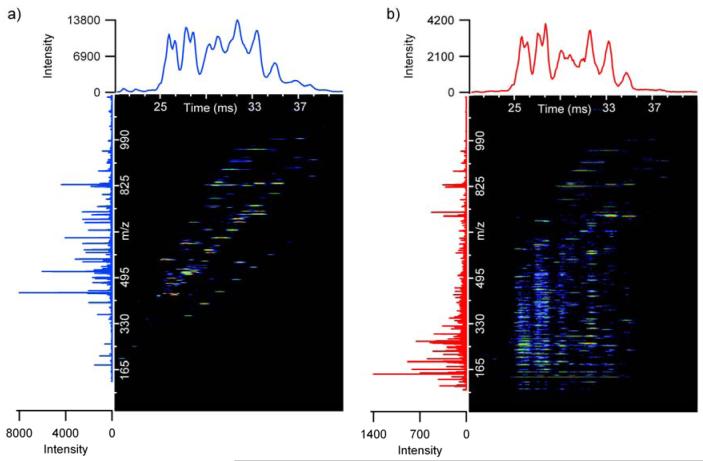

The IMS-MS nested spectra (plotting drift time, m/z, and intensity) for the 4-peptide mixture collected in both non-fragmentation and linear voltage ramping fragmentation conditions are shown in Figure 3a and 3b. The fragmentation spectra obtained using the linear voltage gradient were compared to spectra obtained using a constant (flat) fragmentation voltage at 35 V above non-fragmentation voltage settings (Figure 3c). 35 V was selected for the flat gradient because very little fragmentation occurred for both (fibrinopeptide A)2+ and (neurotensin)2+ at voltages lower than 35 V, since they had the largest m/z ratios and lowest charge states. With the exception of fragmentation voltages, all instrumental parameters were held constant for the three spectra in Figure 3. As expected, the fragment ions all had the same drift time as their corresponding precursor ions. Interestingly, the total ion chromatogram (TIC) profile for the linear fragmentation gradient was similar to the precursor ion TIC profile, while the flat gradient showed different contours at short drift time. The equivalent profiles for Figure 3a and 3b indicate that the abundance ratios of all peptides in the mixture remain similar. Therefore, the experimental conditions of the linear gradient did not cause any bias from the precursor conditions; however, in the flat voltage gradient (35 V), bias did occur for some of the short drift time peptide ions.

Figure 3.

a) The parent nested spectrum of the four peptide mixture of bradykinin, angiotensin I, neurotensin and fibrinopeptide A. The fragmentation spectra for the four peptide mixture is shown in b) for the linear gradient and c) for the flat gradient at 35 V. The total ion chromatograms (TICs) are displayed above the nested spectra and integrated mass spectra are on the left. Higher m/z fragment ions below 30 ms exist only when a linear gradient is applied because the voltage used for the flat gradient over-fragments many of the peptide ions with drift times less than 30 ms.

The linear and flat gradient spectra were further compared to understand why bias occurs in the flat voltage gradient for short drift time ions. The main variation between the nested spectra for these two fragmentation gradients was that many of the high m/z fragment ions at drift times lower than 30 ms in the linear voltage gradient (Figure 3b) were not observed in the flat gradient (Figure 3c). Since the flat gradient of 35 V was optimized for ions with drift times around 32 ms, this voltage was too high for ions with drift times lower than 30 ms. The excessive collision energies for these shorter drift time ions caused high ion scattering losses and over-fragmentation. The flat gradient also had ion intensities that ranged from only 65-80% of those in the linear gradient TIC for ions with drift times below 32 ms. However, the TIC intensities that ranged from 31-34 ms were very similar for both gradients since the flat gradient was optimized for ions around 32 ms, and comparable fragment features were observed in the nested spectra for this drift time range.

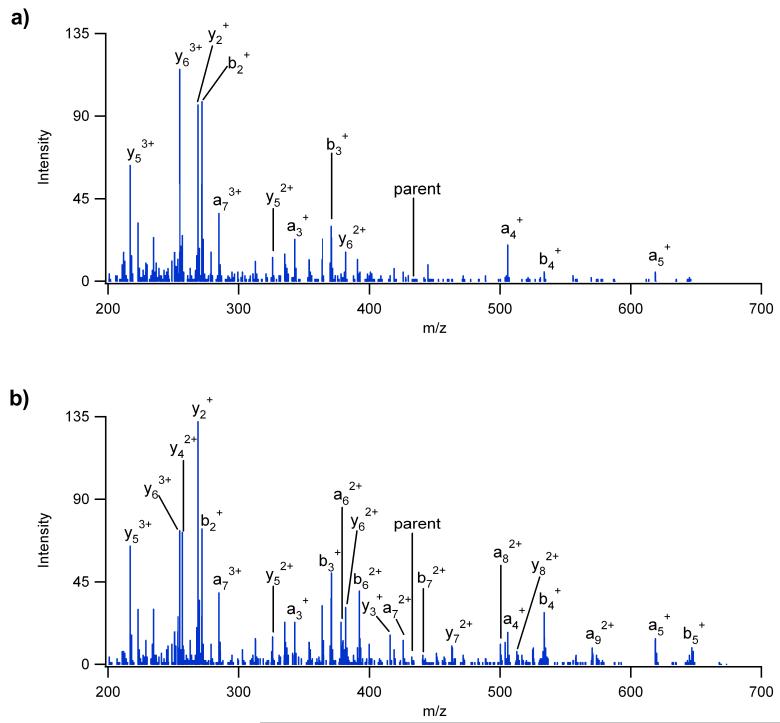

The extracted fragmentation mass spectrum of (angiotensin I)3+ shown in Figure 4 further illustrates the loss of high m/z fragment ions when the flat gradient was applied to the shorter drift time ions. Since (angiotensin I)3+ has an average drift time of 25.3 ms, many of its high m/z fragment ions detected in the linear gradient (Figure 4b) were not observed in the flat gradient (Figure 4a). The intermediate m/z fragment ions for the flat gradient were also either much lower in intensity or not present because of over-fragmentation and increased ion scattering losses. If a voltage less than 35 V was used for the flat gradient, then fragmentation of the lower drift time ions such as (angiotensin I)3+ could be optimized, but the higher drift time ions showed poor dissociation efficiencies. These observations support the expectation that efficient fragmentation for a mixture of different ions is not feasible with a flat gradient unless all precursor ions occur over a minimal drift time range.

Figure 4.

The fragmentation spectra for (angiotensin I)3+ from the 4 peptide mixture in Figure 2 where a) a flat gradient of 35 V was applied and b) a linear gradient was applied. Since (angiotensin I)3+ occurred at a drift time of 25.3 ms, the flat gradient over-fragments the peptide while the higher m/z fragment ions are preserved when a linear gradient is utilized.

The fragmentation efficiency of the linear gradient was evaluated to examine ion losses when the voltage in the quadrupole region was increased. Fragmentation efficiency was calculated as the area under the arrival time distribution (ATD) for all fragment ions at a specific drift time divided by the area under the ATD for the initial precursor ion at the same drift time (measured in the non-fragmentation experiment),

| (2) |

where EF is the fragmentation efficiency, AAF is the area under the ATD of all ions at a specific drift time in the fragmentation experiment, APF is the area under the ATD of the precursor ion (at the same drift time as AAF) in the fragmentation experiment, and APN is the area under the ATD for the precursor ion in the non-fragmentation experiment. The fragmentation and precursor spectra were collected for the same amount of time and repeated five times to make sure ion transmission remained the same between spectra.

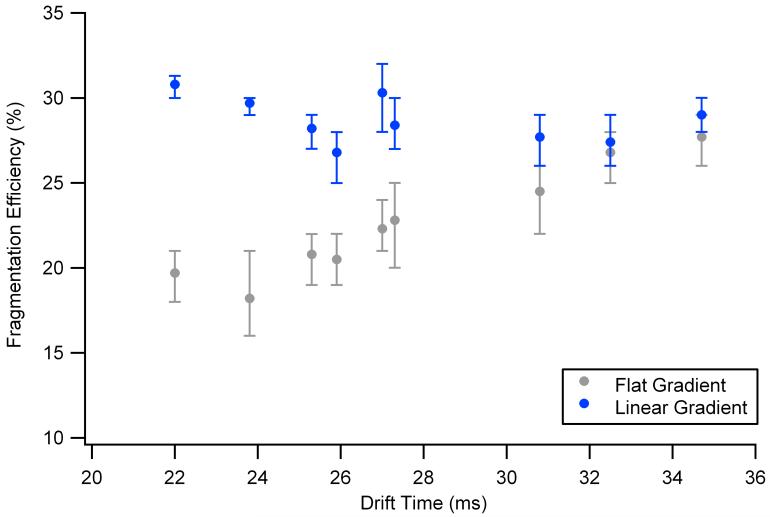

The fragmentation efficiencies for both the linear and flat gradients (at 35 V) are plotted in Figure 5. A maximum fragmentation efficiency of ∼30% was observed for both gradients, which is comparable with the efficiencies observed in triple quadrupole mass spectrometers.35, 36 Comparable efficiencies were retained for most of the ions at different drift times using the linear gradient. However, 30% efficiency was only possible between drift times of 31-34 ms for the flat gradient. At the other drift times, the fragmentation efficiency decreased, emphasizing the importance of using a linear gradient for the fragmentation of a mixture of ions.

Figure 5.

Drift time versus fragmentation efficiency for the flat gradient at 35 V (grey) versus the linear gradient (blue). Maximum, minimum and average fragmentation efficiencies are shown for each ion. The efficiencies for the linear and flat were similar from 31-34 ms since the flat gradient was optimized for this drift time range.

Once the benefit of linearly ramping the fragmentation voltage was demonstrated for the simple 4-peptide mixture, the method was evaluated for more complex samples; in this case, a tryptic digest of BSA at a concentration of 0.05 mg/mL. Figure 6 illustrates both the BSA precursor and linear gradient fragmentation spectra for an m/z range from 0 to 1155. The TIC profiles for the precursor and linear gradient were similar for both experimental conditions, indicating that the linear gradient did not bias any specific drift time regions of the peptide ions in the BSA sample. The fragmentation efficiencies of the ions in the BSA sample were also characterized for the linear gradient, and most of the ions had fragmentation efficiencies of ∼30%. These efficiencies were also observed for the intensities of the precursor and fragment TICs, since the peaks in the fragmentation TIC (Figure 6b) were ∼30% of the corresponding precursor peak intensities (Figure 6a). Fragmentation efficiencies of 30% were also observed for the 4-peptide sample, so even though BSA is a more complex sample, the linear fragmentation gradient still performed effectively, indicating its utility for fragmenting other complex sample mixtures.

Figure 6.

a) The parent and b) fragmentation nested spectra for a tryptic digest of BSA. The fragmentation spectrum shown utilizes the linear voltage gradient.

Conclusions

We have developed a method for increasing the fragmentation voltage after the IMS drift cell as a function of drift time, so that close to optimum collisional excitation occurs for each ion in a peptide mixture. Further characterization of this method illustrated that:

Fragmenting a mixture of peptides with a single fragmentation voltage (collision energy) causes both under- and over-fragmentation to occur in the spectrum.

The voltage required for optimum fragmentation of a peptide mixture is approximately proportional to the ion’s drift time; therefore, higher mobility ions do not need as much collision energy as lower mobility ions.

The implementation of a linear increase in the fragmentation voltage as a function of drift time provides fragmentation efficiencies of approximately 30% for most ions in a mixture.

It is anticipated that the improved dissociation efficiency obtained for complex peptide mixtures (e.g. in proteomics analyses) using IMS-MS approaches has the potential to substantially eliminate the undersampling associated with MS-MS analyses while maintaining broad applicability and thus provide improved proteome coverage.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Alexandre Shvartsburg for insightful discussions about charge state dependent fragmentation. Portions of this work were supported by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, the NIH National Center for Research Resources (RR 18522), and the NIH National Cancer Institute (R21 CA12619-01). Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is operated by the Battelle Memorial Institute for the U.S. Department of Energy through Contract DE-AC05-76RLO1830.

References

- 1.McLuckey SA. Principles of collisional activation in analytical mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1992;3:599–614. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(92)85001-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shukla AK, Futrell JH. Tandem mass spectrometry: dissociation of ions by collisional activation. J. Mass Spectrom. 2000;35:1069–1090. doi: 10.1002/1096-9888(200009)35:9<1069::AID-JMS54>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papayannopoulos IA. The interpretation of collision-induced dissociation tandem mass spectra of peptides. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 1995;14:49–73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin SE, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Marto JA. Subfemtomole MS and MS/MS Peptide Sequence Analysis Using Nano-HPLC Micro-ESI Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:4266–4274. doi: 10.1021/ac000497v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zubarev RA, Horn DM, Fridriksson EK, Kelleher NL, Kruger NA, Lewis MA, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Electron Capture Dissociation for Structural Characterization of Multiply Charged Protein Cations. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:563–573. doi: 10.1021/ac990811p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelleher NL, Lin HY, Valaskovic GA, Aaserud DJ, Fridriksson EK, McLafferty FW. Top Down versus Bottom Up Protein Characterization by Tandem High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:806–812. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneiter R, Brügger B, Sandhoff R, Zellnig G, Leber A, Lampl M, Athenstaedt K, Hrastnik C, Eder S, Daum G, Paltauf F, Wieland FT, Kohlwein SD. Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) Analysis of the Lipid Molecular Species Composition of Yeast Subcellular Membranes Reveals Acyl Chain-based Sorting/Remodeling of Distinct Molecular Species En Route to the Plasma Membrane. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:741–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt H, Schmidt R, Geisslinger G. LC-MS/MS-analysis of sphingosine-1-phosphate and related compounds in plasma samples. Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators. 2006;81:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solouki T, Reinhold BB, Costello CE, O’Malley M, Guan SH, Marshall AG. Electrospray Ionization and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry of Permethylated Oligosaccharides. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:857–864. doi: 10.1021/ac970562+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey DJ. Collision-induced fragmentation of underivatized N-linked carbohydrates ionized by electrospray. J. Mass Spectrom. 2000;35:1178–1190. doi: 10.1002/1096-9888(200010)35:10<1178::AID-JMS46>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burlingame AL, Boyd RK, Gaskell SJ. Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1996;68(12):599–652R. doi: 10.1021/a1960021u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biemann K. Peptides and proteins: Overview and strategy. Methods Enzymol. 1990;193:351–360. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)93426-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haller I, Mirza UA, Chait BT. Collision Induced Decomposition of Peptides. Choice of Collision Parameters. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1996;7:677–681. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(96)85613-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith RD, Loo JA, Edmonds CG, Barinaga CJ, Udseth HR. New developments in biochemical mass spectrometry: electrospray ionization. Anal. Chem. 1990;62:882–899. doi: 10.1021/ac00208a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biemann K. Mass Spectrometry of Peptides and Proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1992;61:977–1010. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.004553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang X-J, Thibault P, Boyd RK. Fragmentation reactions of multiply-protonated peptides and implications for sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry with low-energy collision-induced dissociation. Anal. Chem. 1993;65:2824–2834. doi: 10.1021/ac00068a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masselon C, Anderson GA, Harkewicz R, Bruce JE, Pasa-Tolic L, Smith RD. Accurate Mass Multiplexed Tandem Mass Spectrometry for High-Throughput Polypeptide Identification from Mixtures. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:1918–1924. doi: 10.1021/ac991133+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masselon C, Pasa-Tolic L, Lee S-W, Li L, Anderson GA, Harkewicz R, Smith RD. Identification of tryptic peptides from large databases using multiplexed tandem mass spectrometry: simulations and experimental results. Proteomics. 2003;3:1279–1286. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakraborty AB, Berger SJ, Gebler JC. Use of an integrated MS - multiplexed MS/MS data acquisition strategy for high-coverage peptide mapping studies. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:730–744. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowers MT, Kemper PR, von Helden G, van Koppen PAM. Gas-Phase Ion Chromatography: Transition Metal State Selection and Carbon Cluster Formation. Science. 1993;260:1446–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.260.5113.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clemmer DE, Jarrold MF. Ion Mobility Measurements and their Applications to Clusters and Biomolecules. J. Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:577–592. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wyttenbach T, Bowers MT. Gas-Phase Conformations: The Ion Mobility/Ion Chromatography Method. Top. Curr. Chem. 2003;225:207–232. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoaglund-Hyzer CS, Clemmer DE. Ion Trap/Ion Mobility/Quadrupole/Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry for Peptide Mixture Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:177–184. doi: 10.1021/ac0007783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valentine SJ, Koeniger SL, Clemmer DE. A Split-field Drift Tube for Separation and Efficient Fragmentation of Biomolecular Ions. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:6202–6208. doi: 10.1021/ac030111r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koeniger SL, Valentine SJ, Myung S, Plasencia M, Lee YL, Clemmer DE. Development of Field Modulation in a Split-Field Drift Tube for High-Throughput Multi-dimensional Separations. J. Proteome Res. 2005;4:25–35. doi: 10.1021/pr049877d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koeniger SL, Merenbloom SI, Valentine SJ, Jarrold MF, Udseth HR, Smith RD, Clemmer DE. An IMS-IMS Analogue of MS-MS. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:4161–4174. doi: 10.1021/ac051060w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merenbloom SI, Koeniger SL, Valentine SJ, Plasencia MD, Clemmer DE. IMS-IMS and IMS-IMS-IMS/MS for Separating Peptide and Protein Fragment Ions. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:2802–2809. doi: 10.1021/ac052208e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strittmatter EF, Kangas LJ, Petritis K, Mottaz HM, Anderson GA, Shen Y, Jacobs JM, Camp DG, Smith RD. Application of Peptide LC Retention Time Information in a Discriminant Function for Peptide Identification by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2004;3:760–769. doi: 10.1021/pr049965y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker ES, Clowers BH, Li F, Tang K, Tolmachev AV, Prior DC, Belov ME, Smith RD. Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry Performance Using Electrodynamic Ion Funnels and Elevated Drift Gas Pressures. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:1176–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly RT, Page JS, Luo Q, Moore RJ, Orton DJ, Tang K, Smith RD. Chemically Etched Open Tubular and Monolithic Emitters for Nanoelectrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:7796–7801. doi: 10.1021/ac061133r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim T, Tolmachev AV, Harkewicz R, Prior DC, Anderson GA, Udseth HR, Smith RD, Bailey TH, Rakov S, Futrell JH. Design and Implementation of a New Electrodynamic Ion Funnel. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:2247–2255. doi: 10.1021/ac991412x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang K, Shvartsburg AA, Lee HN, Prior DC, Buschbach MA, Li FM, Tolmachev AV, Anderson GA, Smith RD. High-Sensitivity Ion Mobility Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry Using Electrodynamic Ion Funnel Interfaces. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:3330–3339. doi: 10.1021/ac048315a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibrahim Y, Tang KQ, Tolmachev AV, Shvartsburg AA, Smith RD. Improving Mass Spectrometer Sensitivity Using a High-Pressure Electrodynamic Ion Funnel Interface. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1299–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mason EA, McDaniel EW. Transport Properties of Ions in Gases. Wiley; New York, NY: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomson BA, Douglas DJ, Corr JJ, Hager JW, Jolliffe CL. Improved Collisionally Activated Dissociation Efficiency and Mass Resolution on a Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer System. Anal. Chem. 1995;67:1696–1704. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McFarland MA, Chalmers MJ, Quinn JP, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. Evaluation and Optimization of Electron Capture Dissociation Efficiency in Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:1060–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]