Abstract

Angiogenesis is critical for the growth and metastatic spread of tumours. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is the most potent inducer of neovasculature, and its increased expression has been related to a worse clinical outcome in many diseases. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relation between VEGF, its receptors (VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2) and microvessel density (MVD) in thyroid diseases. Immunostaining for VEGF and VEGF receptors was performed in 66 specimens of thyroid tissue, comprising 17 multinodular goitre (MNG), 14 Graves’ disease, 10 follicular adenoma, 8 Hashimoto's thyroiditis, 7 papillary carcinoma and 10 normal thyroid specimens. Thyrocyte positivity for VEGF and VEGF receptors was scored 0–3. Immunohistochemistry for CD31, and CD34 on the same sections was performed to evaluate MVD. Immunohistochemical staining of VEGF in thyrocytes was positive in 92% of all the thyroid tissues studied. Using an immunostaining intensity cut off of 2, increased thyrocyte staining was seen in follicular adenoma specimens, MNG and normal thyroids compared with Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves’ disease (P < 0.05). Similarly, VEGF thyrocyte expression in Graves’ disease was less than other pathologies (P < 0.05). VEGFR-1 expression and the average MVD score did not differ between the different thyroid pathologies. VEGF expression was lower in autoimmune pathologies compared to autonomous growth processes. Conversely, both VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 were widely expressed in benign and neoplastic thyroid disease, suggesting that the up-regulation of VEGF and not its receptors occurs as tissue becomes autonomous. There was no clear relationship between MVD measurement and thyroid pathology.

Keywords: MVD, thyroid, VEGF, VEGF receptors

Angiogenesis is the development of new blood vessels from pre-existing vessels and whilst being a crucial process in normal physiology (Risau 1997), it is an important pathogenic process in both benign and malignant disease. Microvessel density (MVD) measurement has been shown to be a quantitative method of assessing angiogenesis, and tumour MVD has been shown to correlate with the concentration and expression of proangiogenic growth factors, e.g. VEGF (Toi et al. 1995) and with tumour behaviour. In many human tumours, including breast, bladder, and stomach, increased angiogenesis has been shown to be associated with the development of metastases (Weidner et al. 1991, 1993), poor prognosis (Horak et al. 1992; Weidner et al. 1992), and reduced survival (Bochner et al. 1995; Maeda et al. 1995).

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a 34- to 46-kDa glycoprotein that is a potent stimulator of the endothelial cell growth and can stimulate both the physiological and pathological angiogenesis (Ferrara et al. 1992). VEGF mediates its biological effects by binding two main tyrosine kinase receptors VEGF-1 (Flt-1) and VEGF-2 (Flk-1/KDR), expressed mainly on endothelial cells; VEGFR-2 is responsible for signalling, whereas VEGFR-1 may play a regulatory role (Risau 1997). The binding of VEGF with its receptors regulates angiogenesis through a paracrine effect and haematopoiesis through an autocrine loop (Kliche & Waltenberger 2001; Shibuya 2002; Gerber & Ferrara 2003), and the inhibition of VEGF its receptors or signalling pathways has been shown to suppress angiogenesis and tumour growth (Brekken & Thorpe 2001; Carlomagno et al. 2002; Ye et al. 2004). Increased VEGF expression has been linked with poor outcome and increased risk of metastasis or recurrence in a number of human cancers such as oesophageal cancer (Inoue et al. 1997), breast cancer (Anan et al. 1996; Gasparini et al. 1997; De Jong et al. 1998), colon cancer (Takahashi et al. 1995), lung cancer (Imoto et al. 1998), hepatocellular carcinoma (Poon et al. 2001), gastric cancers (Maeda et al. 1996), head and neck cancers (Eisma et al. 1997), ovarian cancer (Yamamoto et al. 1997), bladder cancer (Crew 1999) and melanoma (Salven et al. 1997).

Several studies have demonstrated the expression of VEGF in normal, benign and malignant thyroid tissues, both in vivo and in vitro (Viglietto et al. 1995; Sato et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1998; Katoh et al. 1999; Klein et al. 1999, 2001; Fenton et al. 2000; Ramsden 2000; Nagura et al. 2001). Angiogenesis plays an important role in goitre development with endothelial cell proliferation occurring before increased proliferation of the thyroid follicular cells (Wollman et al. 1978) and increases in both serum VEGF and the intrathyroidal vascular area have been shown in patients with Graves’ disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis (Iitaka et al. 1998).

The expression of VEGF and its receptors with MVD in normal, benign and malignant thyroid disease has not been fully assessed. Therefore, this study was performed to address this.

Materials and methods

Thyroid tissue

Permission was obtained from the local ethics committee to access material from the pathology archives at Hull and East Yorkshire NHS Trust (Hull, UK). The details of 56 patients with histological proven thyroid disease were retrieved from the thyroid database of the one of the authors (JE). The pathological diagnoses of the specimens included 17 MNG, 14 Graves’ disease, 10 follicular adenomas, 8 Hashimoto's thyroiditis, 7 papillary carcinomas and 10 normal thyroid tissues from laryngectomy specimens.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC Methods for VEGF and receptors VEGFR-1 and 2, and CD34 and CD31

Sections were cut at 5μm and floated onto positively charged slides (SuperFrost Plus, Menzel-Glaser, Germany), from representative formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumour blocks. The slides were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanols. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was carried out by immersing the slides in citrate buffer (pH6) and microwaving at 600 W for 20 min, before cooling and rinsing with phosphate-buffered saline (For microvessel density: 3 min at 900 W in pH 6.0 citrate buffer, then heating for 20 min at 150 W, in two 10 min steps). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the sections in 1% H2O2. Non-specific binding sites were then blocked by preincubating with 20% normal horse serum (Dako Ltd, Ely, UK) and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS/0.3% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature. Sections were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-VEGF antibody at 1:50 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and VEGFR-1 antibody at 1:100 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), as well as monoclonal mouse anti- VEGFR-2 antibody at 1:100 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature (CD34 at a concentration of 1:20 and CD31 at a concentration of 1:50).

After washing with 0.25% BSA and 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS, sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary pan-specific antibody (Dako Ltd) at 1:500 for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were, then, washed in PBS with 0.05% Tween-20, and then incubated with horse radish peroxidase – conjugated Streptavidin biotin complex (HRP-StrepABC) for 45 min (Vectastain Universal Quick Kit PK-7800, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). All sections were again washed, and immunoreactivity was visualised by adding H202 as enzyme substrate, in the presence of 0.05% 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB). Nuclei were then lightly counterstained with Harris Haematoxylin, before rehydrating and mounting with DPX.

VEGF immunostaining score

Each section was scored blindly by two observers according to a semi-quantitative design (Klein et al. 1999, 2001;). Each sample was scored for the percentage of stained thyrocytes (0, absence of staining; 1, <30% of thyrocytes stained; 2, 30–60% of thyrocytes stained; 3, >60% of thyrocytes stained).

Microvessel counting

Most of the examined thyroid sections were heterogeneous with respect to the amount and distribution of microvessels. Areas staining for CD34 or CD31, whether single endothelial cells or clusters of endothelial cells, regardless of the absence/presence of a lumen were counted as individual microvessels. After scanning at low power (40×), three areas with the highest concentration of microvessels (vascular hot spots) were selected, avoiding areas with lymphocytic infiltration or fibrosis. Each area was evaluated with one high power (200×) field in such a way as to include the maximum number of microvessels. The average number of microvessels per high power field was determined and reported as average microvessel count AMC/Field. Stained endothelial cells or endothelial cell clusters that were separate from adjacent vessels, tumour cells, or connective tissue elements were considered to be single countable microvessels, as previously described by Weidner et al., 1992.

Statistical analysis

Results were tabulated and data analysed using the spss statistical package (SPSS Professional Statistics, SPSS Inc., IL, USA). The chi-square test was used for differences in staining between benign and malignant groups and a probability of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The Spearman Rank test was employed to determine correlations coefficients between VEGF, SST and microvessel density.

Results

VEGF

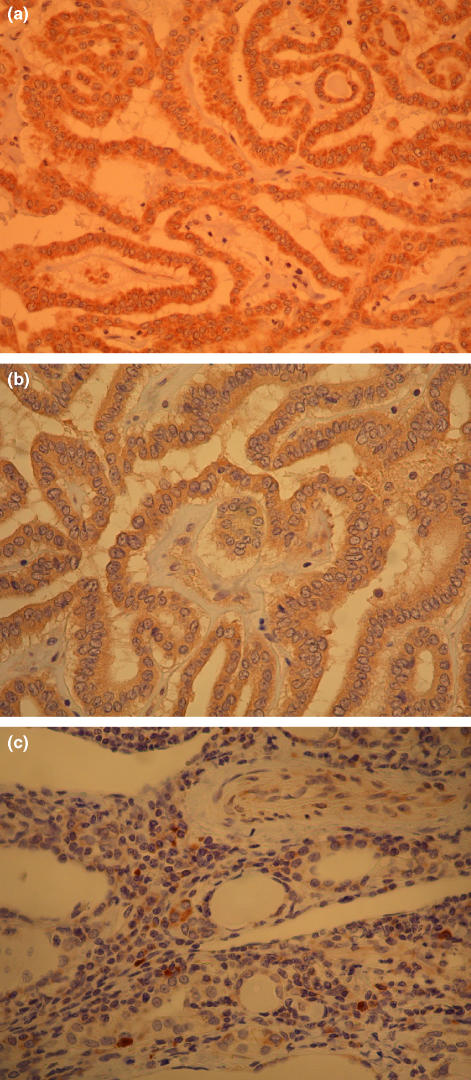

Positive cytoplasmic staining of VEGF was found in both thyrocytes and vascular endothelial cells (Figure 1). The positive staining was focal and cytoplasmic, not diffuse or membranous. Sixty-one of 66 of the samples stained for VEGF in thyrocytes including all of the normal and neoplastic tissues (follicular adenoma and papillary carcinoma). All of the tissues in which no VEGF staining was observed were of the benign thyroid tissue origin (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry for VEGF, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2. (a) The cytoplasm of follicular cells in papillary thyroid cancer is strongly positive for VEGF. (Original magnification ×100). (b) Follicular cells in papillary thyroid cancer showing positive reaction for VEGFR-1. (Original magnification ×100). (c) Follicular cells in papillary thyroid cancer showing positive reaction for VEGFR-2. (Original magnification ×100).

Table 1.

VEGF, VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2 immunostaining for the 66 cases

| Immunostaining | MNG n = 17 | Graves’n = 14 | Hashimoto's n = 8 | Follicular adenoma n = 10 | Papillary carcinoma n = 7 | Normal n = 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thyrocytes (%) | ||||||

| VEGF | 16 (94) | 11 (79) | 7 (88) | 10 (100) | 7 (100) | 10 (100) |

| VEGFR-1 | 16 (94) | 8 (57) | 6 (75) | 9 (90) | 6 (86) | 9 (90) |

| VEGFR-2 | 17 (100) | 14 (100) | 8 (100) | 9 (90) | 7 (100) | 10 (100) |

| Vascular endothelium (%) | ||||||

| VEGF | 11 (65) | 3 (21) | 3 (38) | 8 (80) | 5 (71) | 5 (50) |

| VEGFR-1 | 13 (76) | 2 (14) | 3 (38) | 6 (60) | 5 (71) | 4 (40) |

| VEGFR-2 | 15 (88) | 8 (57) | 5 (62) | 4 (40) | 6 (86) | 5 (50) |

Results given as numbers and percentages.

MNG, multinodular goitre; n, number of cases.

Further analysis of the relative intensity of the positive immunostained tissues was performed. This showed that 8 of 10 follicular adenoma specimens, 12 of 17 MNG, 7 of 10 normal and 4 of 7 papillary cancer specimens scored 2 or more for VEGF in the thyrocytes. Only 2 of 14 Graves’ disease and 2 of 8 Hashimoto's specimens had a score of 2 or more for VEGF in thyrocytes. (Table 2)

Table 2.

VEGF immunostaining score in thyrocytes for the 66 cases

| VEGF thyrocyte immunostaining score | MNG n = 17 | Graves’n = 14 | Hashimoto's n = 8 | Follicular adenoma n = 10 | Papillary carcinoma n = 7 | Normal n = 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

MNG, multinodular goitre; n, number of cases.

VEGF expression in endothelial cells was positive in 8 of 10 follicular adenoma specimens, 5 of 7 papillary cancers and 11 of 17 MNG specimens. Increased thyrocyte staining was seen in follicular adenoma specimens, MNG and normal thyroids compared to Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves’ disease (P < 0.05). Similarly, VEGF thyrocyte expression in Graves’ disease was less than other pathologies (P < 0.05).

VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2

VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) was expressed in more than 50% of the entire studied thyrocytes with a trend to lower expression in autoimmune pathology of Graves’ and Hashimoto's disease (57% and 75% respectively). However, there was no difference in VEGFR-1 or VEGFR-2 (Flk-1/KDR) expression compared with normal, MNG, follicular adenoma and papillary carcinoma (Figure 1, Table 1).

MVD

The basement membranes of microvessels around thyroid follicles were clearly immunostained with anti-CD34 and anti-CD31 antibody and represented vascular loops. The CD31-positive staining was fainter than the CD34-positive reaction for all tissues studied and they are expressed as of average microvessel count AMC/Field (Table 3). The MVD scores using CD34 in papillary carcinoma, Graves’ disease were higher than normal thyroid tissue. The lowest score was recorded in follicular adenoma.

Table 3.

Microvessel density

| MVD CD34 (Mean) | MVD CD31 (Mean) | |

|---|---|---|

| MNG (n = 17) | 34.5 | 17.4 |

| Graves’ (n = 14) | 37.8 | 19.5 |

| Hashimoto's (n = 8) | 33.3 | 22.7 |

| Follicular adenoma (n = 10) | 29.1 | 18.4 |

| Papillary carcinoma (n = 7) | 40.3 | 19.6 |

| Normal (n = 10) | 36.9 | 20.7 |

n, number of cases.

Discussion

In this study, VEGF was co-expressed with its receptors, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, in both benign and malignant thyroid disease. Furthermore, there was an increase in both the distribution and intensity of VEGF immunopositivity in MNG, follicular adenomas and papillary cell carcinoma in comparison with the autoimmune diseases of Graves’ disease and Hashimoto's disease. However, one form or another of medical treatment has been tried in the Graves’ and Hashimoto's cases prior to surgery in this series. This may have some effect on the expression of VEGF and its receptors. A study by Yamada et al. (2006) has demonstrated that iodide at high concentration decreases the expression of VEGF. In addition to that, those cases may not be an accurate representation of Graves’ or Hashimoto's disease in general. Surgery is rarely performed in treating those particular diseases and our findings may be a more true reflection of the cases that require surgical treatment. On the other hand, expression of the receptors VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 showed minimal variation between the differing diseases, other than a reduction of VEGFR-1 immunopositivity in Graves’ disease. This suggests that the up-regulation of VEGF expression rather than its receptors are important in these diseases. Our findings are in accord with several studies that have demonstrated the expression of VEGF in normal, benign and malignant thyroid tissues both in vivo and in vitro (Viglietto et al. 1995; Sato et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1998; Katoh et al. 1999; Klein et al. 1999, 2001; Fenton et al. 2000; Ramsden 2000; Nagura et al. 2001; De la Torre et al. 2006). Our data are in accord with other studies that have also demonstrated more intense VEGF Immunostaining in papillary thyroid carcinoma, follicular thyroid carcinoma, Hürthle cell carcinoma, medullary thyroid cancers, thyroiditis, and Graves’ disease than adjacent normal thyroid tissue (Soh et al. 1997; Klein et al. 2001).

VEGF expression appears to be related to aspects of thyroid tumour behaviour. Reports have correlated the increased expression of VEGF in thyroid neoplasia with a higher risk of recurrence and metastasis using immunohistochemical staining of VEGF proteins and Northern blot analysis of VEGF messenger RNA (m-RNA) (Soh et al. 1997; Bunone et al. 1999; Klein et al. 2001). Viglietto et al. showed that the elevated expression of VEGF m-RNA in thyroid cancers is associated with high tumourigenic potential, and can be an important event in the transition from low to high-grade tumours. Lymph node metastases of thyroid tumours showed increased VEGF expression with respect to the primary tumour (Bunone et al. 1999). Some authors tried to quantify VEGF expression using the percentage of stained thyrocytes and the intensity of immunostaining in papillary thyroid cancer, this has demonstrated higher VEGF expression in metastatic cancer compared with nonmetastatic cancers (Klein et al. 2001). This technique was suggested as a method for distinguishing those thyroid tumours more likely to metastasize. This data is also in accord with the higher VEGF immunostaining seen in MNG, follicular adenomas and papillary carcinomas found here.

In accord with our findings showing the expression of VEGFR-1 in Graves’ disease, Nagura, et al. showed that VEGFR-1 protein and mRNA were observed in endothelial cells of Graves’ disease tissues. However, while all the 19 patients included in that study were mRNA positive for VEGFR-1, our study showed positive endothelial cell immunostaining for VEGFR-1 in only 2 (14%) out of 14 Graves’ disease specimens. This may be a question of differing sensitivities of the methods employed, or that there is reduced translation of protein. However, in an immunohistochemical study, Fenton et al. found similar expression of VEGFR-1 in MNG and papillary thyroid carcinoma.

VEGFR-1 in the endothelial cells of the interfollicular vessels was present in all of the thyroid specimens that we studied in accord with others (Klein et al. 1999) where VEGFR-1 was reported in endothelial cells of normal thyroid tissue, papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. In serial sections, we found co-expression of VEGF and VEGFR-1 in the vascular endothelium that was more evident than the co-expression of VEGF and VEGFR-2. Conversely, the co-expression of VEGF and its two receptors was similar in thyrocytes irrespective of the thyroid pathology. These data are consistent with the concept of VEGF signalling by autocrine or paracrine mechanisms within the thyroid for VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 in the thyrocytes.

An increased MVD in papillary thyroid carcinoma was found when compared with normal thyroid tissues that have been reported by others, though the threefold difference previously reported was not found (Segal et al. 1996; Akslen & Livolsi 2000). An increased risk of recurrence and shorter disease-free survival is reported in the more vascular papillary thyroid tumours (Dhar et al. 1998; Ishiwata et al. 1998). Conversely, others have noted that a lower MVD is associated with a worse prognosis, poor differentiation (Herrmann et al. 1994; Fontanini et al. 1996) and higher mortality (Akslen & Livolsi 2000). A large cohort study of 191 cases of thyroid diseases found that MVD was decreased in proliferative lesions, benign and malignant, compared with normal thyroid tissue (De la Torre et al. 2006). The same study also concluded that despite increased expression of VEGF in thyroid cancers, these markers were not related to poor prognosis. It is important to note that these studies employed different techniques to quantify MVD using F8, CD31 and CD34; some have deliberately assessed vessel counts at hot spots, whereas others did not, explaining the differing results between studies. In our study we made no attempt to make any correlation between MVD and clinicopathological parameters.

In conclusion, VEGF distribution and expression was lower in the autoimmune pathologies of Graves and Hashimoto's than those associated with autonomous growth processes. Conversely, both VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 were widely expressed in the thyrocytes of both benign and neoplastic thyroid disease, suggesting that up-regulation of VEGF and not its receptors occurs as tissue becomes autonomous. There was no clear relationship between MVD measurement and thyroid pathology.

References

- Akslen LA, Livolsi VA. Increased angiogenesis in papillary thyroid carcinoma but lack of prognostic importance. Hum. Pathol. 2000;31:439–442. doi: 10.1053/1-ip.2000.6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anan K, Morisaki T, Katano M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor are potential angiogenic and metastatic factors in human breast cancer. Surgery. 1996;119:333–339. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochner BH, Cote RJ, Weidner N, et al. Angiogenesis in bladder cancer: relationship between microvessel density and tumor prognosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1603–1612. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.21.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekken RA, Thorpe PE. Vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular targeting of solid tumors. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:4221–4229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunone G, Vigneri P, Mariani L, et al. Expression of angiogenesis stimulators and inhibitors in human thyroid tumors and correlation with clinical pathological features. Am. J. Pathol. 1999;155:1967–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65515-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlomagno F, Vitagliano D, Guida T, et al. ZD6474, an orally available inhibitor of KDR tyrosine kinase activity, efficiently blocks oncogenic RET kinases. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7284–7290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crew JP. Vascular endothelial growth factor: an important angiogenic mediator in bladder cancer. Eur. J. Urol. 1999;35:2–8. doi: 10.1159/000019811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong JS, van Diest PJ, van der Valk P, Baak JP. Expression of growth factors, growth-inhibiting factors, and their receptors in invasive breast cancer. II: Correlations with proliferation and angiogenesis. J. Pathol. 1998;184:53–57. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199801)184:1<53::AID-PATH6>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre NG, Buley I, Wass JA, Turner HE. Angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in thyroid proliferative lesions: relationship to type and tumour behaviour. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2006;13:931–944. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar DK, Kubota H, Kotoh T, et al. Tumor vascularity predicts recurrence in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 1998;176:442–447. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma RJ, Spiro JD, Kreutzer DL. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in head and neck Squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 1997;174:513–517. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton C, Patel A, Dinauer C, Robie DK, Tuttle RM, Francis GL. The expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and the type 1 vascular endothelial growth factor receptor correlate with the size of papillary thyroid carcinoma in children and young adults. Thyroid. 2000;10:349–357. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Houck K, Jakeman L, Leung DW. Molecular and biological properties of the vascular endothelial growth factor family of proteins. Endocr. Rev. 1992;13:18–32. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini G, Vignati S, Pacini F, Pollina L, Basolo F. Microvessel count: an indicator of poor outcome in medullary thyroid carcinoma but not in other types of thyroid carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 1996;9:636–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini G, Toi M, Gion M, et al. Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor protein in node-negative breast carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1997;89:139–147. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber HP, Ferrara N. The role of VEGF in normal and neoplastic hematopoiesis. J. Mol. Med. 2003;81:20–31. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann G, Schumm-Draeger PM, Muller C, et al. T lymphocytes, CD68-positive cells and vascularisation in thyroid carcinomas. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1994;120:651–656. doi: 10.1007/BF01245376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak ER, Leek R, Klenk N, et al. Angiogenesis, assessed by platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule antibodies, as indicator of node metastases and survival in breast cancer. Lancet. 1992;340:1120–1124. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93150-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iitaka M, Miura S, Yamanaka K, et al. Increased serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels and intrathyroidal vascular area in patients with Graves’ disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998;83:3908–3912. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.11.5281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imoto H, Osaki T, Taga S, Ohgami A, Ichiyoshi Y, Yasumoto K. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in non-small-cell lung cancer: prognostic significance in squamous cell carcinoma. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1998;115:1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Ozeki Y, Suganuma T, Sugiura Y, Tanaka S. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in primary esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Association with angiogenesis and tumor progression. Cancer. 1997;79:206–213. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970115)79:2<206::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwata T, Iino Y, Takei H, Oyama T, Morishita Y. Tumor angiogenesis as an independent prognostic indicator in human papillary thyroid carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 1998;5:1343–1348. doi: 10.3892/or.5.6.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh R, Miyagi E, Kawaoi A, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in human thyroid neoplasms. Hum. Pathol. 1999;30:891–897. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M, Picard E, Vignaud JM, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene and protein: strong expression in thyroiditis and thyroid carcinoma. J. Endocrinol. 1999;161:41–49. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1610041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M, Vignaud JM, Hennequin V, et al. Increased expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor is a pejorative prognosis marker in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:656–658. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliche S, Waltenberger J. VEGF receptor signalling and endothelial function. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:61–66. doi: 10.1080/15216540252774784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Chung YS, Takatsuka S, et al. Tumor angiogenesis as a predictor of recurrence in gastric carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995;13:477–481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.2.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Chung YS, Ogawa Y, et al. Prognostic value of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;77:858–863. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960301)77:5<858::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagura S, Katoh R, Miyagi E, Shibuya M, Kawaoi A. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptor-1 (Flt-1) in Graves disease possibly correlated with increased vascular density. Hum. Pathol. 2001;32:10–17. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon RT, Ng IO, Lau C, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor predicts venous invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Ann. Surg. 2001;233:227–235. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200102000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden JD. Angiogenesis in the thyroid gland. J. Endocrinol. 2000;166:475–480. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1660475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386:671–674. doi: 10.1038/386671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salven P, Heikkila P, Joensuu H. Enhanced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in metastatic melanoma. Br. J. Cancer. 1997;76:930–934. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Miyakawa M, Onoda N, et al. Increased concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor in cyst fluid of enlarging and recurrent thyroid nodules. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997;82:1968–1973. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.6.3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal K, Shpitzer T, Feinmesser M, Stern Y, Feinmesser R. Angiogenesis in follicular tumors of the thyroid. J. Surg. Oncol. 1996;63:95–98. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199610)63:2<95::AID-JSO5>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor family genes: when did the three genes phylogenetically segregate? Biol. Chem. 2002;383:1573–1579. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh EY, Duh QY, Sobhi SA, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression is higher in differentiated thyroid cancer than in normal or benign thyroid. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997;82:3741–3747. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.11.4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Kitadai Y, Bucana CD, Cleary KR, Ellis LM. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, KDR,correlates with vascularity, metastasis, and proliferation of human colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3964–3968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toi M, Inada K, Suzuki H, Tominaga T. Tumor angiogenesis in breast cancer: its association with vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1995;36:193–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00666040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viglietto G, Maglione D, Rambaldi M, et al. Upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and downregulation of placenta growth factor (PlGF) associated with malignancy in human thyroid tumors and cell lines. Oncogenesis. 1995;11:1569–1579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JF, Milosveski V, Schramek C, Fong GH, Becks GP, Hill DJ. Presence and possible role of vascular endothelial growth factor in thyroid cell growth and function. J. Endocrinol. 1998;157:5–12. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1570005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis: correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;324:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidner N, Folkman J, Pozza F, et al. Tumor angiogenesis: a new significant and independent prognostic indicator in early stage breast carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1992;84:1875–1887. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.24.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidner N, Carrol PR, Flax J, Blumenfeld W, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis correlates with metastasis in invasive prostate carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 1993;143:401–409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollman SH, Herveg JP, Zeligs JD, Ericson LE. Blood capillary enlargement during the development of thyroid hyperplasia in the rat. Endocrinology. 1978;103:2306–2314. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-6-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada E, Yamazaki K, Takano K, Obara T, Sato K. Iodide inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-A expression in cultured human thyroid follicles: a microarray search for effects of thyrotropin and iodide on angiogenesis factors. Thyroid. 2006;16:545–554. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Konishi I, Mandai M, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in epithelial ovarian neoplasms: correlation with clinicopathology and patient survival, and analysis of serum VEGF levels. Br. J. Cancer. 1997;76:1221–1227. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye C, Feng C, Wang S, et al. sFlt-1 gene therapy of follicular thyroid carcinoma. Endocrinology. 2004;145:817–822. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]