Abstract

The thenar flap is a time-tested method of fingertip reconstruction, but functional outcome data are scarce in the literature. The purpose of this study was to analyze the long-term function following fingertip reconstruction with a laterally based thenar flap and to compare these results with other established methods. Nineteen patients underwent a thenar flap between 2001 and 2004. Patients ranged in age from 3 to 48 years. The mean angle of proximal interphalangeal immobilization was 66° (range 30–85°) and was greater for radial digits. Time to division ranged from 11 to 15 days. Seventeen patients underwent follow-up evaluation of range of motion, two-point discrimination, and sensory threshold (Semmes-Weinstein). A questionnaire measured patient satisfaction in three areas: sensibility, function, and appearance. The mean follow-up was 20 months. Reconstructive goals were met in all cases. The mean metacarpalphalangeal and proximal interphalangeal motion in the reconstructed fingers was not significantly reduced, compared to the unaffected side. The distal interphalangeal motion was 42°, compared to 55° in the contralateral side (p < 0.01). The mean static two-point discrimination in the flap was 6.8 mm, compared to 3.8 mm in the contralateral side. Fourteen of 17 patients exhibited monofilament thresholds of 33.1 g/mm2 or less. There were no hypertrophic or tender donor scars. This study does not support the contention that thenar flaps are associated with problematic donor scars and flexion contractures, even for adults or ulnar digits. Sensory recovery compared favorably to published results of cross-finger and homodigital flaps. When sound technical principles are followed, excellent outcomes can be expected.

Keywords: amputation, fingertip reconstruction, thenar flap, sensory recovery

Introduction

The thenar flap, described by Gatewood in 1926 [10, 13], is a reliable and time-tested means of composite fingertip reconstruction. Unlike skin grafts or cross-finger flaps, thenar flaps can provide durable, glabrous skin, as well as sufficient subcutaneous soft tissue to restore the three-dimensional structure of the fingertip. The technique has been criticized in the literature for causing flexion contractures and tender, unsightly donor site scars, and it has even been asserted that the procedure should not be performed in patients older than 30 years [12]. However, a review of the literature reveals almost no objective functional data to justify these assertions. Confusing matters further, the few existing studies vary widely in respect to flap design, the timing of flap division, and rehabilitation [1, 6, 16].

In 1969, Beasley [2] described a laterally based thenar flap, with its distal border positioned in the metacarpalphalangeal (MP) flexion crease of the thumb [2]. In the article he stressed the importance of positioning the thumb as to minimize flexion at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint of the finger to be reconstructed. In 1982, he published a large clinical series of thenar flaps, applying these principles [14]. Excellent subjective data were reported, but the objective functional analysis was not sufficiently rigorous to allow a comparison with other reconstructive techniques, such as cross-finger flaps or reverse digital artery flaps.

The purpose of the present study was to review a single surgeon's experience with the laterally based thenar flap for composite fingertip reconstruction. An objective, long-term assessment of the range of motion and sensory recovery was performed, to compare the results with other established techniques.

Materials and Methods

Institutional Review

The present study received the approval of the institutional review board of the sponsoring institution for research involving human subjects.

Indications

During the study period, the thenar flap was used for acute traumatic fingertip amputations, affecting any digit other than the thumb, with exposed bone or tendon. Amputations were usually transverse or volar oblique, with a paucity of soft tissue, thus precluding a local flap. Simple shortening of the bone and closure was performed when it could be accomplished without sacrifice of functional length or vital structures, such as the fingernail or insertion of the profundus tendon.

Operative Techniques

The first-stage procedure is performed under general anesthesia or regional block. The wound is irrigated and thoroughly debrided. A template is made to estimate the tissue deficit. The thenar flap design follows the recommendations of Beasley et al. [2, 3, 14], with its base along the radial border of the thumb, at the border between glabrous and nonglabrous skin, and with the distal border of the flap lying in the MP flexion crease of the thumb (Fig. 1). The width of the flap is determined by the tissue needs, as measured by the template. A w-plasty can be incorporated in the tip of the flap to reproduce the rounded appearance of the fingertip and to facilitate partial closure of the donor site. The thenar muscle fascia is elevated with the flap, and care is taken to avoid injury to the radial digital nerve of the thumb. The flap is inset into the finger with fine nylon sutures. When the fingernail is present, the distal edge of the flap can be sutured directly to the nail plate.

Figure 1.

(Above, left) Eleven-year-old boy with traumatic amputation of the right middle fingertip in a bicycle accident. (Above, center) Composite loss of skin, pulp, and nail support. (Above, right) Design of laterally based thenar flap with distal border at MP flexion crease and w-plasty at the tip. (Below, left) Flap inset, at the time of division. (Below, center) Result at 3 years postoperatively, volar view. (Below, right) Result at 3 years postoperatively, lateral view, at full extension.

The hand is immobilized with the thumb in palmar abduction and the MP joint of the affected digit flexed, to minimize flexion at the PIP joint. A 2-in. strip of plaster is incorporated in the dressing, running along the dorsal aspect of the finger, to maintain this position (Fig. 2). A standard thumb-spica splint is placed over this to complete the immobilization.

Figure 2.

Splint used for immobilization following first operative stage, with a 2-in. plaster strip incorporated to maintain the position of the affected finger.

Flap division is performed at 10–15 days after elevation. In adults, this can be easily performed in the office with local anesthesia. Minimal insetting is performed at the time of flap division (one or two sutures on each side), and the donor site is only partially closed. An active range of motion program is immediately initiated for the finger and thumb, under the supervision of a hand therapist. Meticulous wound hygiene and dressing changes are performed until the wounds are completely healed.

Chart Review

The records were reviewed of all patients who underwent reconstruction of a fingertip defect with a laterally based thenar flap in our unit between January 2001 and April 2004. Demographic data, mechanism of injury, type of injury, time to flap division, and complications, if any, were recorded.

Functional Assessment

Patients were recalled for sensory and range of motion testing. Testing was performed by an occupational therapist. Sensory examination consisted of Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing, as well as static and moving two-point discrimination tests. For these tests the central portion of the flap was assessed, and tests were repeated until a consistent result was obtained. Filament markings were converted to a threshold pressure by using the method of Dellon et al. [7].

The active range of motion of the MP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints of the reconstructed finger was measured. The active range of motion of the corresponding finger of the contralateral hand was measured as a control. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the differences between the reconstructed and control digits. The threshold value for statistical significance was p < 0.05.

Questionnaire

Patients completed a questionnaire that surveyed their opinion in three areas: sensibility, function, and appearance. They were asked to assign an overall rating in the three areas (poor, fair, good, or excellent). Respondents were asked to plot their satisfaction in each of the three areas on a 7-point scale ranging from “extremely unsatisfied” (1) to “extremely satisfied” (7). Patients were also invited to add specific comments or justifications for their ratings.

Results

Chart review

Nineteen patients were identified who fit the selection criteria. There were 15 males and 4 females, ranging in age from 3 to 48 years, with a median age of 20 years (Table 1). Five patients (26%) were more than 30 years old at the time of operation. The level of injury was the proximal one-third of the distal phalanx in five cases, the middle third in nine cases, and the distal third in five cases. All four fingers were affected, with 14 of 19 cases (79%) involving either the index or long finger (Table 2). The mechanism of injury varied widely (Table 1), with saw injuries being the most commonly observed mechanism in adult patients, and interior doors the most common in children.

Table 1.

Patient data and functional results.

| Pt | Sex | Age | Finger | Mechanism | Days to division | Angle of PIP immobilization (°) | F/U (months) | MP ROM (°) | PIP ROM (°) | DIP ROM (°) | Flap S2PD (mm) | Contralateral S2PD (mm) | Flap M2PD (mm) | Contralateral M2PD (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 35 | L long | Between pipes | 11 | 55 | 18 | 95 | 90 | 55 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| 2 | M | 27 | R long | Table saw | 13 | 60 | 17 | 105 | 95 | 50 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| 3 | M | 37 | L ring | Saw | 14 | 45 | 12 | 95 | 90 | 25 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | F | 22 | R index | Conveyer belt | 11 | Lost to follow-up | ||||||||

| 5 | M | 10 | L long | Bike accident | 15 | 75 | 32 | 100 | 80 | 40 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 2 |

| 6 | F | 5 | L index | Interior door | 12 | Lost to follow-up | ||||||||

| 7 | M | 3 | R ring | Exercise bike | 12 | 80 | 31 | 100 | 90 | 30 | N/A | N/A | NA | N/A |

| 8 | M | 45 | R long | Chain saw | 13 | 75 | 27 | 75 | 90 | 45 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| 9 | M | 6 | R small | Interior door | 14 | 40 | 26 | 105 | 90 | 55 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 10 | M | 7 | R long | Car door | 14 | 70 | 22 | 95 | 90 | 45 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 11 | M | 5 | L small | Interior door | 12 | 60 | 22 | 80 | 85 | 55 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 12 | M | 17 | L long | Metal plate | 13 | 30 | 19 | 95 | 90 | 40 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 3 |

| 13 | M | 48 | L index | Conveyer belt | 11 | 80 | 18 | 105 | 85 | 20 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 |

| 14 | M | 23 | R ring | Machinery | 13 | 75 | 17 | 100 | 90 | 55 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 3 |

| 15 | M | 48 | R long | Flywheel | 12 | 70 | 15 | 85 | 85 | 45 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 16 | M | 19 | L long | Circular saw | 12 | 80 | 14 | 100 | 90 | 45 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 17 | F | 3 | R index | Car door | 12 | 85 | 14 | 100 | 95 | 40 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 18 | F | 20 | L index | Circular saw | 12 | 50 | 13 | 95 | 90 | 30 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 3 |

| 19 | M | 20 | L long | Metal plate | 14 | 65 | 15 | 95 | 90 | 40 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

Table 2.

Distribution of reconstructed fingers and mean angle of PIP immobilization (N = 19).

| Finger | N | Mean angle (°) |

|---|---|---|

| Index | 5 | 80 |

| Middle | 9 | 64 |

| Ring | 3 | 67 |

| Small | 2 | 50 |

Time from injury to reconstruction ranged from 2 to 48 h, with a mean of 12 h. The angle of PIP joint immobilization ranged from 30° to 80° of flexion, with a mean angle of 66°. In general, a less acute angle of immobilization was needed for the ulnar digits than for the radial digits (Table 2). Time to division ranged from 11 to 15 days (mean 12.8 days). The reconstructive goals were met in all cases without revision.

Functional Assessment

Seventeen patients were available for functional testing. Follow-up ranged from 12 to 32 months with a mean follow-up time of 20 months. The results of the Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing are outlined in Table 3. Upon monofilament testing, 14 of 17 flaps (82%) exhibited a threshold pressure of 33.1 g/mm2 or less, implying preservation of protective sensibility [4]. The three patients with the highest threshold forces were all in the >30 years age group.

Table 3.

Results of Semmes-Weinstein monofiliament testing (N = 17).

| Threshold pressure (g/mm2) | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 4.9 | 2 | 12 |

| 17.7 | 2 | 12 |

| 33.1 | 10 | 59 |

| 44.3 | 3 | 18 |

Two-point discrimination (2PD) testing was performed in 15 patients, as interpretable data could not be obtained from the two youngest patients in the series. The static 2PD in the flaps ranged from 3 to 10 mm, with a mean of 5.5 ± 2.5 mm, compared to a mean of 3.8 ± 1.1 mm for the equivalent site on the contralateral hand (Table 1). The moving 2PD in the flap ranged from 3 to 10 mm, with a mean of 6.8 ± 2.0 mm, compared to 3.0 ± 0.6 mm for the unaffected hand (Table 1). There was an observed trend toward higher 2PD values in the older patients. These results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of two-point discrimination testing (N = 15).

| Mean static 2PD (mm) | Mean moving 2PD (mm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Flap | 6.8 ± 2.5 (range 3–10) | 5.5 ± 2.0 (range 3–10) |

| Contralateral | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 0.6 |

There were no functionally significant digital flexion contractures or thumb adduction contractures observed at follow-up. The mean MP joint motion in the reconstructed finger was 96 ± 8.5°, compared to 102 ± 9.8° in the nonaffected side. This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). The mean PIP joint motion was 89 ± 3.6°, compared to 92 ± 5.0° for the contralateral side. Again, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09). There was a statistically significant reduction in mean DIP joint motion observed in the affected digits (42° versus 55°) when compared to controls (p < 0.01) (Table 5). The average calculated total active motion for the reconstructed digits was 215 ± 19°.

Table 5.

Mean postoperative range of motion (N = 17).

| Affected digit | Contalateral digit | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean MP joint motion (degrees ± SD) | 96 ± 8.5 | 102 ± 9.8 | 0.06 |

| Mean PIP joint motion (degrees ± SD) | 89 ± 3.6 | 92 ± 5.0 | 0.09 |

| Mean DIP joint motion (degrees ± SD) | 42 ± 10.8 | 55 ± 5.7 | <0.01 |

aUsing Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Questionnaire

Twelve patients completed the questionnaire. In respect to sensibility, 9 of 12 patients rated their result as good or excellent, and the mean response on the 7-point scale was 4.9. In respect to function, 11 of 12 patients characterized their result as good or excellent, and the mean rating was 6.1 out of 7. Twelve of 12 patients rated the appearance of the reconstructed finger as good or excellent, and the mean rating was 6.3 out of 7 (Table 6). Two patients reported cold intolerance. One patient reported painful hyperesthesia in the fingertip. There were no tender or hypertrophic donor site scars reported.

Table 6.

Questionnaire results (12 respondents).

| Category | Poor | Fair | Good | Excellent | 7-Point scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensibility | 2 (17%) | 1 (8%) | 6 (50%) | 3 (25%) | 4.9 |

| Function | 0 | 1 (8%) | 3 (25%) | 8 (67%) | 6.1 |

| Appearance | 0 | 0 | 3 (25%) | 9 (75%) | 6.3 |

Discussion

The thenar flap was introduced by Gatewood [10, 13], a singly named but multiply talented Chicago surgeon, in 1926. As originally conceived, the flap was placed high on the thenar eminence and based medially [10]. In the 1950s, Flatt [8] strongly endorsed a proximally based thenar flap, but one that encroached significantly upon the palm. He presciently concluded his article with the statement, “Badly done, the operation can cripple a hand.” Many of the criticisms leveled against thenar flaps have arisen from their being confused with palmar flaps, which are associated with a high complication rate. The findings of this study support the caveats of flap design and division advanced by Beasley [2, 3, 14], namely, that the flap should be placed high on the thenar eminence, based laterally, and divided promptly.

Traumatic amputation of the fingertip produces a composite loss of tactile skin, pulp, and nail support. Unlike skin grafts or standard cross finger flaps, the thenar flap can provide a three-dimensional composite reconstruction that is functional, durable, and aesthetically acceptable. This is reflected in the questionnaire results, with 75% of respondents reporting good or excellent results in all three categories (Table 6).

Objective functional data following thenar flaps are not abundant in the literature. In 1983, Dellon [6] reported excellent sensory recovery in a series of five distally based thenar flaps. The mean static 2PD was 5.6 mm, and the moving 2PD was 3.3 mm at a mean follow-up of 32 months. The flaps were raised well onto the palm and divided no earlier than 3 weeks. Objective range of motion data were not reported. In 1996, Barbato et al. [1] reported a series of 20 patients who underwent a distally based thenar flap. Again, excellent sensory recovery was reported, with a mean static 2PD of 6.5 mm at 21 months' follow-up. The objective range of motion was not reported, but there was a 25% rate of PIP flexion contracture requiring extension splinting.

In the present study group there were no significant flexion contractures observed. There was a small measurable reduction in mean MP and PIP joint motion in the reconstructed digits when compared to the contralateral side (Table 5). The difference was 3° for the PIP joint and 6° for the MP joint, and these values may have reached statistical significance had the sample size been larger. There was a measured decrease in DIP joint motion of 13° compared to the contralateral side, and this difference was statistically significant. It is unclear, however, if these differences in motion were caused by the reconstruction or the initial injury, especially in the case of the DIP joint, as several patients had amputations through the proximal one-third of the distal phalanx. Motion was equally well preserved for ulnar-sided digits as for the index and long fingers. In the occasional patient with a very wide hand and short digits, the small finger does not comfortably reach the thenar eminence, but in the absence of this configuration, an ulnar-sided defect should not be considered a contraindication for a thenar flap.

There was no difference in motion observed between patients older than 30 years (N = 5) and younger patients (Fig. 3), and age was not considered a contraindication for thenar flap during the study period. However, the small number of patients in the >30 years age group, a reflection of the demographics of the hand trauma patients at our institution, severely limits our ability to draw meaningful conclusions about the effect of the thenar flap upon range of motion in the older population.

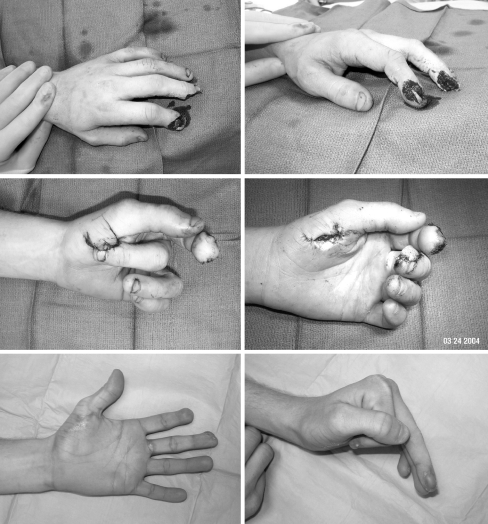

Figure 3.

(Above, left) Thirty-eight-year-old man with a saw injury to the left hand affecting the index and long fingers. (Above, right) There was significant loss to the index finger nail matrix necessitating ablation; the long finger distal phalanx and deep flexor tendon were exposed. (Center, left) After completion of the index finger amputation and thenar flap to the long finger. (Center, right) At the time of flap division with minimal closure of the donor site and flap insetting. (Below, left) At 3 months postoperatively, volar view. (Below, right) At 3 months postoperatively, lateral view at full extension.

The sensory recovery was incomplete in all cases, but protective sensibility was regained in all but three patients, as evidenced by threshold testing (Table 3). Consistent with the observations of other authors, sensory recovery was better in the younger patients. The mean static 2PD in the flaps was 6.8 mm, and the mean moving 2PD was 5.5 mm. These results compare favorably with published values for noninnervated cross-finger flaps [5, 15, 17, 18] (Table 7), and fall within the range of published values for reverse digital artery flaps [9, 11, 19, 20] (Table 8). One patient reported neuromatous-type hypersensitivity at the fingertip. There were no painful or hypertrophic donor site scars observed in the series.

Table 7.

Comparison of thenar flap sensory recovery with historical values for cross-finger flaps.

Table 8.

Comparison of thenar flap sensory recovery with historical values for reverse digital artery flaps.

The thenar flap is an effective and reliable means of composite fingertip reconstruction. The results of this study do not support the contention that thenar flaps are associated with problematic donor scars or postoperative flexion contractures, even in the adult population and ulnar digits. Functional results in this series compare favorably to other reconstructive methods. When sound principles of flap design, timing of division, and early mobilization are followed, excellent outcomes can be expected.

Footnotes

Presented at the 2006 Meeting of the American Association for Hand Surgery, Tuscon, AZ.

References

- 1.Barbato BD, Guelmi K, Romano SJ, et al. Thenar flap rehabilitated: a review of 20 cases. Ann Plast Surg 1996;37:135–139. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Beasley RW. Reconstruction of amputated fingertips. Plast Reconstr Surg 1969;44:349–352. [PubMed]

- 3.Beasley RW. Local flaps for surgery of the hand. Orthop Clin North Am 1970;1:219–225. [PubMed]

- 4.Bell-Krotoski JA, Fess EE, Figarola JH, et al. Threshold detection and Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments. J Hand Ther 1995;8:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cohen BE, Cronin ED. An innervated cross-finger flap for fingertip reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1983;72:688–695. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dellon AL. The proximal inset thenar flap for fingertip reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1983;72:698–704. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE, Brandt KE. The markings of the Semmes–Weinstein nylon monofilaments. J Hand Surg 1993;18:756–757. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Flatt AE. The thenar flap. J Bone Jt Surg 1957;39B:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Foucher G, Smith D, Pempinelo C, et al. Homodigital neurovascular island flaps for digital pulp loss. J Hand Surg (Br) 1989;14:204–208. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gatewood. A plastic repair of finger defects without hospitalization. JAMA 1926;87:1479.

- 11.Lai C-S, Lin S-D, Chou C-K, et al. A versatile method for reconstruction of finger defects: reverse digital artery flap. Br J Plast Surg 1992;45:443–453. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Louis DS, Jebson PJL, Graham TJ. Amputations. In: Green D, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, editors. Green's operative hand surgery, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. pp. 54–55.

- 13.Meals RA, Brody GS. Gatewood and the first thenar pedicle. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984;73:315–319. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Melone CP, Beasley RW, Carstens JH. The thenar flap—an analysis of its use in 150 cases. J Hand Surg 1982;7:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Nishibawa H, Smith PJ. The recovery of sensation and function after cross-finger flaps for fingertip injury. J Hand Surg (Br) 1992;17:102–107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Okazaki M, Hasegawa H, Kano M, et al. A different method of fingertip reconstruction with the thenar flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;115:885–890. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Smith JR, Bom AF. An evaluation of finger-tip reconstruction by cross-finger and palmar pedicle flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 1965;35:409–418. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Thomson HG, Sorokolit WT. The cross-finger flap in children: a follow-up study. Plast Reconstr Surg 1967;39:482–487. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Varitimidis SE, Dailiana ZH, Zibis AH, et al. Restoration of function and sensitivity utilizing a homodigital neurovascular island flap after amputation injuries of the fingertip. J Hand Surg (Br) 2005;30:338–342. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Yildirim S, Avci G, Akan M, et al. Complications of the reverse homodigital island flap in fingertip reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 2002;48:586–592. [DOI] [PubMed]