Abstract

Recent studies on endotoxin/lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute inflammatory response in the lung are reviewed. The acute airway inflammatory response to inhaled endotoxin is mediated through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and CD14 signalling as mice deficient for TLR4 or CD14 are unresponsive to endotoxin. Acute bronchoconstriction, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-12 and keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC) production, protein leak and neutrophil recruitment in the lung are abrogated in mice deficient for the adaptor molecules myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) and Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR)-domain-containing adaptor protein (TIRAP), but independent of TIR-domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-beta (TRIF). In particular, LPS-induced TNF is required for bronchoconstriction, but dispensable for inflammatory cell recruitment. Lipopolysaccharide induces activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Inhibition of pulmonary MAPK activity abrogates LPS-induced TNF production, bronchoconstriction, neutrophil recruitment into the lungs and broncho-alveolar space. In conclusion, TLR4-mediated, bronchoconstriction and acute inflammatory lung pathology to inhaled endotoxin are dependent on TLR4/CD14/MD2 expression using the adapter proteins TIRAP and MyD88, while TRIF, IL-1R1 or IL-18R signalling pathways are dispensable. Further downstream in this axis of signalling, TNF blockade reduces only acute bronchoconstriction, while MAPK inhibition abrogates completely endotoxin-induced inflammation.

Keywords: lung inflammation, MAPK, TNF, Toll-like receptor

Introduction

Lung inflammation due to environmental pollutants, including endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), plays an important role in the development and progression of chronic respiratory diseases including asthma (Kennedy et al. 1987; Donham et al. 1989; Schwartz et al. 1995; Michel et al. 1996; Liu 2004). Endotoxin inhalation causes acute respiratory distress syndrome, neutrophil recruitment, injury of the alveolar epithelium and endothelium with protein leak in the alveolar space (Kline et al. 1999; Arbour et al. 2000).

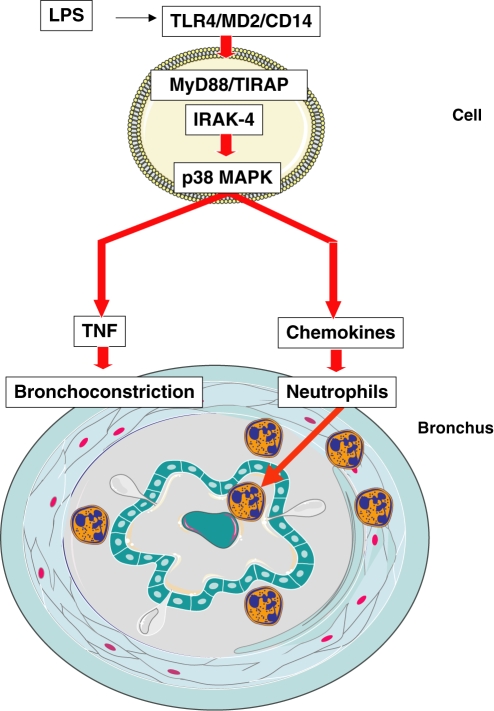

Here we review our recent data from our investigations on endotoxin-induced respiratory inflammation with emphasis on Toll-like receptor (TLR) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF), and discuss the results with data from other literature. Intranasal endotoxin from Gram-negative bacteria provokes acute pulmonary inflammation, local TNF production, alveolar-capillary leak and bronchoconstriction in normal BL/6 mice (Lefort et al. 2001; Schnyder-Candrian et al. 2005). Toll-like receptor 4 and CD14 play a critical role in the pulmonary response to systemic endotoxin administration (Lefort et al. 1998; Andonegui et al. 2002, 2003). Aerogenic endotoxin exposure also induces neutrophil recruitment into the alveolar space (Lefort et al. 2001) with activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and secretion of TNF and other pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Schnyder-Candrian et al. 2005). The cellular events, e.g. endotoxin-sensing epithelial and macrophage/dendritic cell and the inflammatory and bronchoconstrictive response are depicted schematically (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

TLR4-mediated bronchoconstriction and acute inflammatory lung pathology to inhaled endotoxin depend on TLR4/CD14/MD2 cellular sensing and TLR4 signalling. Blockade of MyD88/TIRAP signalling abrogates bronchoconstriction and inflammation, while disruption of TNF signals by MAPK inhibition prevents only bronchoconstriction.

Different combinations of Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain containing adaptor proteins for TLR are used to activate distinct signalling pathways, most prominently MyD88 and TRIF, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons (IFNs) respectively (Akira et al. 2006; Beutler et al. 2006). Absence of MyD88 confers resistance to systemic endotoxin-induced shock (Kawai et al. 1999). TIRAP-deficient mice are also resistant to the toxic effects of LPS (Yamamoto et al. 2002), with defective induction of TNF, IL-6 or IL-12p40, and delayed activation of NF-κB and MAP kinases (Horng et al. 2002; Oshiumi et al. 2003). Indeed, MyD88 and TIRAP are involved in early activation of NF-κB and MAP kinases (Fitzgerald et al. 2001; Horng et al. 2001, 2002; Yamamoto et al. 2002), whereas TRIF and TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM) are critical for late activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) as well as interferon regulatory factor-3 (IRF-3) activation (Yamamoto et al. 2003a,Yamamoto, 2003b).

The lung is continuously exposed to environmental agents, and the inflammatory response is believed to be different from those present in less exposed, accessible sites (Guillot et al. 2004; Piggott et al. 2005). We showed recently that the TLR adaptor MyD88 is critical for the airway inflammatory response to endotoxins (Noulin et al. 2005). MyD88 is at the crossroads of multiple TLR-dependent and TLR-independent signalling pathways, including IL-1R and IL-18R, or the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Zeisel et al. 2005). In some infection models the extreme sensitivity of MyD88-deficient mice may however be ascribed, at least in part, to deficient IL-1R/IL-18R signalling, as shown recently for cutaneous Staphylococcus aureus infection (Gamero & Oppenheim 2006) and as we showed recently on mycobacterial infections (Fremond et al. 2007).

CD14/TLR4/MD2 endotoxin receptor

Using genetically modified mice we review the role of the TLR4 and CD14 receptors on endotoxin-induced lung injury. Inhaled endotoxin induces an acute inflammatory response in the airways, which is mediated through TLR4 and CD14 ligation, as mice deficient for TLR4 or CD14 are unresponsive to endotoxin. Acute respiratory dysfunction was evaluated by whole body plethysmography, and serves as a measure of bronchoconstriction (Penh) upon endotoxin exposure. Endotoxin-induced bronchoconstriction (Penh) and neutrophil recruitment in the lung were abrogated in mice deficient for TLR4 or CD14. Further, TNF, IL-12p40, keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC) production and protein leak are also dramatically reduced (Togbe et al. 2006). MD2-deficient mice have been reported to be resistant to LPS (Kobayashi et al. 2006) and recent evidence suggests that TLR4 expression, TLR4 clustering and LPS responsiveness critically depend on MD2 membrane expression. Further PRAT4A is a novel membrane protein coexpressed with TLR4 and silencing of PRAT4A-reduced TLR4 expression, as well as LPS response (Wakabayashi et al. 2006).

The inflammatory response depends on TLR4 expression level

Since TLR4 is critical for endotoxin recognition and cellular responses, we used Tlr4 transgenic mice to investigate whether Tlr4 gene dosage might affect acute respiratory response to endotoxin (Bihl et al. 2003). We reported that transgenic mice expressing either 6 or 30 copies of Tlr4 display an augmented LPS-induced bronchoconstrictive response (Penh), neutrophil recruitment into the broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and the lung as assessed by myeloperoxidase activity (MPO) (Togbe et al. 2006). Further, TNF and CXCL1 (KC) production, microvascular and alveolar epithelial injury, with protein leak in the airways and damage of the lung microarchitecture were Tlr4 gene dose-dependently increased (Togbe et al. 2006). Therefore, the level of TLR4 expression determines the extent of acute pulmonary response to inhaled endotoxin, and TLR4 may thus be a valuable target for immunointervention in acute lung inflammation due to endotoxins delivered by aerosol.

MyD88- and TIRAP-dependent, but TRIF-independent response to endotoxin

The TLR adaptor molecules include myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), which associates with TIRAP, and TRIF which is associated with TRAM (Kagan & Medzhitov 2006). Both TIRAP and TRAM are constitutively expressed molecules (Fitzgerald et al. 2001, 2003) and may serve as platforms responsible for the recruitment of the TLR adapters MyD88 and TRIF.

We first investigated the role of MyD88 in endotoxin-induced inflammatory response in the lung. Acute bronchoconstriction, TNF, IL-12p40 and KC production, protein leak and neutrophil recruitment in the lung were abrogated in MyD88-deficient mice (Noulin et al. 2005). MyD88 is not only involved in TLR signalling, but also in IRAK1-mediated IL-1 and IL-18 receptor signalling. Our studies excluded a role for IL-1 and IL-18 pathways in this response, as IL-1R1 and caspase-1 (ICE) deficient mice developed normal lung inflammation, as shown by a vigorous neutrophil recruitment in the BAL fluid, and the lung upon endotoxin exposure, as observed in BL6 control mice (Noulin et al. 2005). In addition, cytokine production and microscopic evidence for inflammation and tissue injury are not attenuated in IL-1R1 and caspase-1 (ICE) deficient mice (Noulin et al. 2005).

Then we generated reciprocal bone marrow chimaeras between MyD88-expressing BL6 and MyD88-deficient mice, using lethal total body irradiation and bone marrow reconstitution as described before (Muller et al. 1996). Using bone marrow reconstituted mice we demonstrate that both haematopoietic and resident cells are necessary for a full MyD88-dependent response to inhaled endotoxin, bronchoconstriction depending on resident cells, while cytokine secretion is mediated by haematopoietic cells (Noulin et al. 2005).

The TLR4 adapter protein TIRAP has recently been shown to be essential for LPS-induced lung inflammation (Jeyaseelan et al. 2005). Lipopolysaccharide-induced bronchoconstriction was therefore compared side by side in TIRAP and MyD88-deficient mice (Togbe et al. 2006). Our published data demonstrate that both adaptor proteins are essential and non-redundant for LPS-TLR4-induced acute pulmonary inflammation response (Figure 1). However, other signals contributing to TLR4 or MyD88-dependent pathways such as TRIF, IL1-R and IL-18R signalling are dispensable for LPS-induced bronchoconstriction and pulmonary neutrophil sequestration (Noulin et al. 2005; Togbe et al. 2006).

TNF has no effect on neutrophil recruitment

First, we investigated the role of membrane-bound TNF and demonstrated that membrane TNF – in the absence of soluble TNF – is sufficient to mediate the inflammatory responses to LPS (Togbe et al. 2007). However, ablation of TNF in mice abrogated bronchoconstriction (Penh) upon endotoxin administration, while inflammation was not affected as described (Schnyder-Candrian et al. 2005). Using cell-type specific TNF-deficient mice we showed that TNF derived from either macrophage/neutrophil (M/N) or T lymphocytes have differential effects on LPS-induced respiratory dysfunction (Penh) and pulmonary neutrophil recruitment (Togbe et al. 2007). While bronchoconstriction, vascular leak, neutrophil recruitment, TNF and thymus- and activation-regulated chemokine (CCL17) (TARC) expression in the lung, were reduced in M/N-deficient mice, T cell-specific TNF-deficient mice displayed augmented bronchoconstriction, vascular leak, neutrophil influx, and local expression of TNF, TARC and KC. Therefore, inactivation of TNF in either M/N or T cells has differential effects on LPS-induced lung disease, suggesting that selective deletion of TNF in T-cells may aggravate airway pathology (Togbe et al. 2007).

MAPK inhibition ablates the endotoxin response

We and others demonstrated that p38 MAPK is activated upon endotoxin exposure of the lung (Schnyder-Candrian et al. 2005). Local administration of a specific MAPK inhibitor abrogated LPS-induced TNF production, bronchoconstriction, neutrophil recruitment into the lungs and broncho-alveolar space, in a dose-dependent manner (Schnyder-Candrian et al. 2005). Therefore, endotoxin-induced acute bronchoconstriction is TNF-dependent and p38 MAPK-mediated, while the neutrophil recruitment is independent of TNF but depends on LPS/TLR4-induced signals mediated by p38 MAPK.

In conclusion, TLR4-mediated, bronchoconstriction and acute inflammatory lung pathology to inhaled endotoxin, depend on the expression of TLR4/CD14/MD2 and on both adaptor proteins, TIRAP and MyD88, suggesting cooperative roles, while TRIF, IL-1R1 and IL-18R signalling pathways are dispensable. Further downstream in this axis of signalling, TNF blockade only reduces acute bronchoconstriction, while MAPK inhibition abrogates completely endotoxin-induced pulmonary inflammation.

Acknowledgments

Grant support by ‘Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie’, Fondation de la Recherche and CNRS. The work was also supported by grants from Le Studium (Orleans), Biomedical Research Foundation and Fondation de la Recherche Médicale.

References

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andonegui G, Goyert SM, Kubes P. Lipopolysaccharide-induced leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions: a role for CD14 versus toll-like receptor 4 within microvessels. J. Immunol. 2002;169:2111–2119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andonegui G, Bonder CS, Green F, et al. Endothelium-derived Toll-like receptor-4 is the key molecule in LPS-induced neutrophil sequestration into lungs. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1264. doi: 10.1172/JCI16510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbour NC, Lorenz E, Schutte BC, et al. TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:187–191. doi: 10.1038/76048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B, Jiang Z, Georgel P, et al. Genetic analysis of host resistance: toll-like receptor signaling and immunity at large. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:353–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihl F, Salez L, Beaubier M, et al. Overexpression of toll-like receptor 4 amplifies the host response to lipopolysaccharide and provides a survival advantage in transgenic mice. J. Immunol. 2003;170:6141–6150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donham K, Haglind P, Peterson Y, Rylander R, Belin L. Environmental and health studies of farm workers in Swedish swine confinement buildings. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1989;46:31–37. doi: 10.1136/oem.46.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KA, Palsson-McDermott EM, Bowie AG, et al. Mal (MyD88-adapter-like) is required for Toll-like receptor-4 signal transduction. Nature. 2001;413:78–83. doi: 10.1038/35092578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KA, Rowe DC, Barnes BJ, et al. LPS-TLR4 signaling to IRF-3/7 and NF-kappaB involves the toll adapters TRAM and TRIF. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1043–1055. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremond CM, Togbe D, Doz E, Rose S, Vasseur V, Maillet I, Jacobs M, Ryffel B, Quesniaux VF. IL-1 receptor-mediated signal is an essential component of MyD88-dependent innate response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 2007;179:1178–1189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamero AM, Oppenheim JJ. IL-1 can act as number one. Immunity. 2006;24:16–17. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot L, Medjane S, Le-Barillec K, et al. Response of human pulmonary epithelial cells to lipopolysaccharide involves Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-dependent signaling pathways: evidence for an intracellular compartmentalization of TLR4. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:2712–2718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305790200. Epub 4 November 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng T, Barton GM, Medzhitov R. TIRAP: an adapter molecule in the Toll signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:835–841. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng T, Barton GM, Flavell RA, Medzhitov R. The adaptor molecule TIRAP provides signalling specificity for Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;420:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nature01180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan S, Manzer R, Young SK, et al. Toll-IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein is critical for early lung immune responses against Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide and viable Escherichia coli. J. Immunol. 2005;175:7484–7495. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan JC, Medzhitov R. Phosphoinositide-mediated adaptor recruitment controls Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. 2006;125:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SM, Christiani DC, Eisen EA, et al. Cotton dust and endotoxin exposure-response relationships in cotton textile workers. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1987;135:194–200. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline JN, Cowden JD, Hunninghake GW, et al. Variable airway responsiveness to inhaled lipopolysaccharide. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999;160:297–303. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9808144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Tanimura N, et al. Regulatory roles for MD-2 and TLR4 in ligand-induced receptor clustering. J. Immunol. 2006;176:6211–6218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefort J, Singer M, Leduc D, et al. Systemic administration of endotoxin induces bronchopulmonary hyperreactivity dissociated from TNF-alpha formation and neutrophil sequestration into the murine lungs. J. Immunol. 1998;161:474–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefort J, Motreff L, Vargaftig BB. Airway administration of Escherichia coli endotoxin to mice induces glucocorticosteroid-resistant bronchoconstriction and vasopermeation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2001;24:345–351. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.3.4289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AH. Something old, something new: indoor endotoxin, allergens and asthma. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2004;5(Suppl. A):S65–S71. doi: 10.1016/s1526-0542(04)90013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel O, Kips J, Duchateau J, et al. Severity of asthma is related to endotoxin in house dust. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996;154:1641–1646. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.6.8970348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Eugster HP, Le Hir M, et al. Correction or transfer of immunodeficiency due to TNF-LT alpha deletion by bone marrow transplantation. Mol. Med. 1996;2:247–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noulin N, Quesniaux VF, Schnyder-Candrian S, et al. Both hemopoietic and resident cells are required for MyD88-dependent pulmonary inflammatory response to inhaled endotoxin. J. Immunol. 2005;175:6861–6869. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshiumi H, Sasai M, Shida K, Fujita T, Matsumoto M, Seya T. TIR-containing adapter molecule (TICAM)-2, a bridging adapter recruiting to toll-like receptor 4 TICAM-1 that induces interferon-beta. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:49751–49762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggott DA, Eisenbarth SC, Xu L, et al. MyD88-dependent induction of allergic Th2 responses to intranasal antigen. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:459–467. doi: 10.1172/JCI22462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder-Candrian S, Quesniaux VF, Di Padova F, et al. Dual effects of p38 MAPK on TNF-dependent bronchoconstriction and TNF-independent neutrophil recruitment in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Immunol. 2005;175:262–269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz DA, Thorne PS, Yagla SJ, et al. The role of endotoxin in grain dust-induced lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995;152:603–608. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togbe D, Schnyder-Candrian S, Schnyder B, et al. TLR4 gene dosage contributes to endotoxin-induced acute respiratory inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006;80:451–457. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0206099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togbe D, Grivennikov SI, Noulin N, et al. T cell-derived TNF down-regulates acute airway response to endotoxin. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:768–779. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi Y, Kobayashi M, Akashi-Takamura S, et al. A protein associated with toll-like receptor 4 (PRAT4A) regulates cell surface expression of TLR4. J. Immunol. 2006;177:1772–1779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, et al. Essential role for TIRAP in activation of the signalling cascade shared by TLR2 and TLR4. Nature. 2002;420:324–329. doi: 10.1038/nature01182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, et al. TRAM is specifically involved in the Toll-like receptor 4-mediated MyD88-independent signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2003a;4:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/ni986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003b;301:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel MB, Druet VA, Sibilia J, Klein JP, Quesniaux V, Wachsmann D. Cross talk between MyD88 and focal adhesion kinase pathways. J. Immunol. 2005;174:7393–7397. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]