Abstract

Adherent interactions between integrins and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins play an important role in tumorigenicity and invasiveness. The major component of ECM is collagen that plays a central role in the interaction with integrins. The expression of certain collagenases (gelatinases) by tumour cells is one of the characteristic features of the so-called metastatic phenotype, presumably by breaking down ECM barriers as well by altering the ECM–cell interaction. Although extracellular collagenases initiate the breakdown of collagen, the final step of collagen degradation is catalysed by intracellular prolidase. Collagen deposition, gelatinolytic and prolidase activities, expression of β1-integrin receptor and their possible relationships were studied in seven operable breast cancer cases. In breast cancer tissue, we have found significant decrease in the amount of collagen. The decrease in collagen deposition in breast cancer tissue was accompanied by increase in the tissue gelatinolytic and prolidase activities. Simultaneously, a slight decrease in the expression of β1-integrin receptor in breast cancer tissue was observed. These results suggest that alteration in collagen metabolism in breast cancer tissue may reflect tissue remodelling, characteristic for invasive phenotype of cancer cells. Increased gelatinolytic and prolidase activities in breast cancer tissue may enhance stromal matrix degradation and thus may promote metastatic dissemination. On the basis of the data, it seems that compounds endowed with gelatinolytic and prolidase inhibitory activities may be considered as a potential drug candidates for breast cancer therapy.

Keywords: β1-integrin receptor, breast cancer, collagen metabolism, gelatinolytic activity, prolidase activity

Collagen is the major component of extracellular matrix (ECM). The interaction between cells and ECM proteins, for example collagen, can regulate cellular gene expression, differentiation and growth, and plays an important role in tumorigenicity and invasiveness (Carey 1991; Ruoslahti 1992). Therefore, any alterations in collagen metabolism may potentially influence cell metabolism and motility. Under in vivo conditions, cancer is characterized by invasiveness and the breakdown of tissue organization. In fact, tumour progression is promoted by the breakdown of ECM proteins. Crucial event in the progression and metastasis of cancer is the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are responsible for the degradation of ECM. The expression of certain collagenases (gelatinases) by tumour cells may contribute to metastatic process, presumably by breaking down ECM barriers as well as by altering the ECM–cell interactions (Ruoslahti 1992). Matrix metalloproteinases are involved in remodelling of the ECM and penetration of normal and tumour cells through tissue barriers (Birkedal-Hansen et al. 1993; Behrendtsen & Werb 1997). Although extracellular collagenases initiate the breakdown of collagen, the final step of its degradation is mediated by prolidase.

Prolidase (E.C. 3.4.13.9) is a cytosolic exopeptidase which cleaves imidodipeptides with C-terminal proline or hydroxyproline (Myara et al. 1984; Chamson et al. 1989; Mock et al. 1990). Most of the imidodipeptides are derived from collagen degradation products (Jackson et al. 1975). The enzyme plays an important role in recycling of proline from imidodipeptides for collagen resynthesis and cell growth (Jackson et al. 1975; Emmerson & Phang 1993). It is evident that an absence of prolidase severely impedes the recycling of collagen-derived proline. Some clinical symptoms, related to collagen deficit, can be attributed to prolidase deficiency (Goodman et al. 1968). On the other hand, an increased activity of liver prolidase was found during the fibrotic process (Myara et al. 1987). It suggests that prolidase, providing proline for collagen biosynthesis, may be a rate-limiting factor in the regulation of collagen production. Such a connection between collagen production and prolidase activity has been found in cultured human skin fibroblasts treated with anti-inflammatory drugs (Miltyk et al. 1996), during experimental ageing of these cells (Pałka et al. 1996), fibroblast chemotaxis (Pałka et al. 1997) and cell surface integrin receptor ligation (Pałka & Phang 1998).

Prolidase deficiency is also accompanied by immunodeficiency (Phang & Scriver 1989) that is due to disturbances in biosynthesis of immunoglobulin and C1q. In view of collagen-like amino acid sequence in both substances, possibly immunological deficit in prolidase deficiency results from disturbances in proline recycling which is subsequently used for immunoglobulin and C1q biosynthesis (Reid & Porter 1976).

Studies on the regulation of collagen metabolism have focused recently on the interaction between cell surface and ECM proteins. Collagen is essential for the maintenance of connective tissue, but it also plays a central role in the interaction with integrin receptors on cell surfaces (Akiyama et al. 1990). Interestingly, prolidase activity is stimulated through signal mediated by β1-integrin receptor (Pałka & Phang 1998). These considerations prompted us to investigate collagen content, gelatinolytic activity, prolidase activity and expression of β1-integrin receptor in breast cancer tissue.

Patients and methods

The protocol of this study was accepted by the Committee for Ethics and Supervision on Human and Animal Research of the Medical Academy of Białystok.

Tissue material

Studies were performed on breast cancer tissues collected during surgery from seven previously untreated patients. Tissues (malignant and normal mammary gland) were collected immediately following modified radical mastectomy and cut into two parts. One-half was frozen down and stored at −70 °C. The other half was fixed in buffered 10% formalin and paraffin-embedded for histological examination. Breast cancers were classified as infiltrating ductal carcinoma G2 (seven cases) according to standard histopathological criteria. Tissues obtained from the most distant region of the tumour (at least 5 cm from the tumour border) from the same patients that were macroscopically and histopathologically confirmed to be normal tissue (four cases) and tissues classified as benign mammary dysplasia (three cases) served as controls.

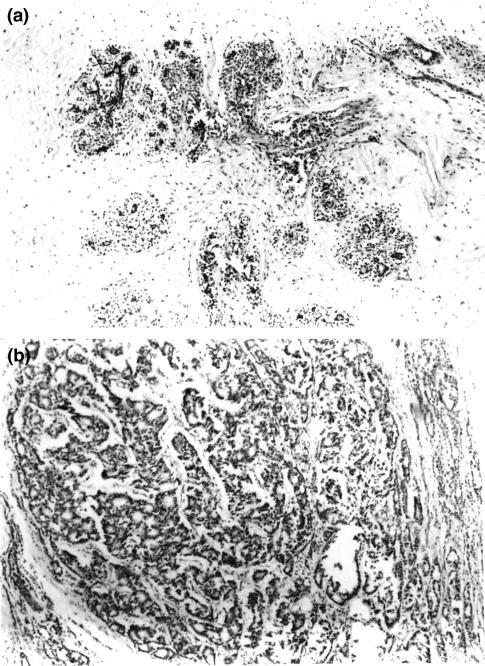

In the so-called ‘normal tissue’, there were neither cellular nor displastic changes observed (Figure 1a). Tumour tissue was infiltrated by lymphocytes and macrophages. Typical histological section of tumour tissue is depicted in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

(a) Typical histological section for control tissue. (b) Typical histological section for breast cancer tissue.

Preparation of tissue extracts

Breast cancer and control tissues were placed in ice-cold 0.05 mol/l Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.6. The tissue homogenates (20% w/v) were prepared in 0.05 mol/l Tris-HCl, pH 7.6 with the use of knife homogenizer (Polytron Bad Wildbad, Germany) and subsequently sonicated at 0 °C. Homogenates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. Supernatant (tissue extract) was used for protein determination and enzyme activity assays.

Reagents

l-proline, l-hydroxy-proline, l-glycyl-proline, bacterial collagenase, gelatin and Sigma-Fast BCIP/NBT reagent were purchased from Sigma Corp., St Louis, MO, as were most other chemicals and buffers used. Monoclonal anti-β1-integrin antibody was obtained from ICN Biomedicals Inc., Irvine, CA. Nitrocellulose membrane (0.2 μm), Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) molecular weight standards and Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 were received from Bio-Rad Laboratories Hercules, CA. Alkaline phosphatase-labelled anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) was obtained from Promega Corp., Madison, WI.

Determination of prolidase activity

The activity of prolidase was determined according to Myara et al. (1982), based on evaluation of proline concentration with Chinard's reagent (Chinard 1952). Activation of prolidase required preincubation with manganese: 100 μl of tissue extract was incubated with 100 μl of 0.05 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.8 containing 20 mm MnCl2 for 1 h at 37 °C. After preincubation, the prolidase reaction was initiated by adding 100 μl of the preincubated mixture to 100 μl of 94 mm glycyl-proline (Gly-Pro) for a final concentration of 47 mm Gly-Pro. After additional incubation for 1 h at 37 °C, the reaction was terminated with 1 ml of 0.45 m trichloroacetic acid. In parallel tubes, reaction was terminated at time ‘zero’ (without incubation). The released proline was determined by adding of 0.5 ml of the trichloroacetic acid supernatant to 2 ml of 1:1 mixture of glacial acetic acid: Chinard's reagent (25 g ninhydrin dissolved at 70 °C in 600 ml of glacial acetic acid and 400 ml of 6 m orthophosphoric acid) and incubated for 10 min at 90 °C. The amount of proline released was determined colorimetrically by absorbance at 515 nm and calculated by using proline standards. Protein concentration was measured by Lowry et al. (1951). Enzyme activity was expressed in nanomoles per minute per milligram of supernatant protein.

Zymography

Gelatinolytic activity was determined according to Woessner (1995). Tissue extract, non-activated or activated with p-aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA), was mixed with Laemmli sample buffer (Laemmli 1970) containing 2.5% SDS (without reducing agent). Equal amounts (about 30 μg) of protein were electrophoresed under non-reducing conditions on 10% polyacrylamide gels impregnated with 1 mg/ml gelatin. After electrophoresis, the gels were incubated in 2% Triton X-100 for 30 min at 37 °C to remove SDS and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in substrate buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8, containing 5 mm CaCl2). After staining with 1% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R 250, gelatin-degrading enzymes present in tissue extract were identified as clear zones in a blue background.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Slab SDS–PAGE was performed according to Laemmli (1970). Samples of 20 μg supernatant protein were subjected to electrophoresis on 0.1% SDS/7.5% polyacrylamide gel. The following Bio-Rad's unstained standards were used: myosin (200 kDa), galactosidase (116.2 kDa), phosphorylase b (97.4 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66.2 kDa), ovalbumin (45 kDa). After electrophoresis, the gels were allowed to equilibrate in a mixture of 0.025 m Tris and 0.2 m glycine in 20% (v/v) methanol for 5 min. The protein was transferred to 0.2 μm pore-sized nitrocellulose, at 100 mA for 1 h using a LKB 2117 Multiphor II electrophoresis unit. Standards on nitrocellulose were stained with 0.2% Panceau S. Positions of standards were marked with S and S NC marker (Schleicher and Schuell, Dassel, Germany) and destained in TBS-T solution (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 150 mm NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20). Nitrocellulose was blocked with 3% IGEPAL CA-630 in TBS for 30 min, then in 1% BSA in TBS for 2 h and finally in 0.1% Tween 20 in TBS for 10 min at room temperature and submitted to western immunoblot.

Western blot analysis

The nitrocellulose was incubated with polyclonal antibody against human prolidase at concentration of 1:3000 and anti-integrin β1-monoclonal antibody at 1:1000 dilution in 5% dried milk in TBS-T for 1 h. Then the alkaline phosphatase conjugated antibody against mouse IgG (whole molecule) was added at concentration 1:7500 in TBS-T. Incubation was continued for 30 min with slow shaking and nitrocellulose was washed with TBS-T (five times for 5 min) and exposed to Sigma-Fast BCIP/NBT reagent.

Determination of protein, proline and hydroxyproline

Protein was determined according to Bradford (1976) method. Hydroxyproline was determined by the method of Prockop and Udenfriend (1960). Proline was assayed with Chinard's reagent (Chinard 1952) as described in methodology for prolidase activity assay.

Statistical analysis

In all experiments, the mean values for seven assays ±standard deviations (SD) were calculated. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's ‘t’-test.

Results

Histologically, in normal tissue there were neither cellular nor displastic changes observed (Figure 1a).

Breast cancers were classified as infiltrating ductal carcinoma G2 according to standard histopathological criteria. Tumour tissue was infiltrated by lymphocytes and macrophages. Typical histological section of tumour tissue is depicted in Figure 1b.

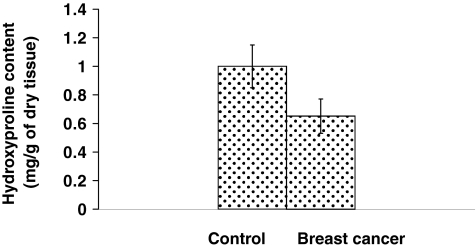

The content of collagen in the breast cancer tissue and respective control tissue obtained from the margin of resected material was determined by means of the hydroxyproline assay. The tissue proteins were hydrolysed with 6 m hydrochloric acid and released hydroxyproline was evaluated. The breast cancer tissue contained about 70% of hydroxyproline compared with control tissue (Figure 2) suggesting a decrease in collagen content in this tissue.

Figure 2.

Hydroxyproline content in the control and breast cancer tissue extract. Mean values from the tissue extract samples of seven patients ± SD are presented. P < 0.001.

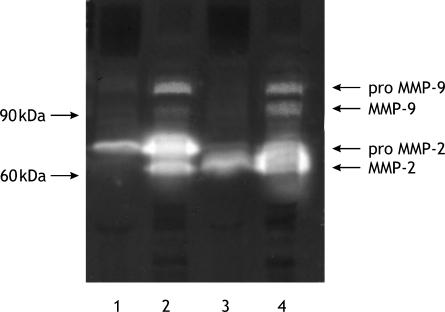

The phenomenon may be due to an increase in the degradation of this protein. Since disturbances in collagen degradation are accompanied by deregulation of tissue gelatinase activity, we determined the tissue gelatinolytic activity by zymography. In fact, increased gelatinolytic activity was found in breast cancer tissue when compared with control one. Control tissue contained only latent form of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) (Figure 3, lane 1). In breast cancer tissue (Figure 3, lane 2), there was an increase in the activity of the latent form of the enzyme, compared with that in control tissue. Additionally, active form of MMP-2 was present. Furthermore, breast cancer tissue contained also latent form of MMP-9. After activation of control tissue with APMA (Figure 3, lane 3) only the active form of MMP-2 was observed. Activation of gelatinases by APMA in breast cancer tissue (Figure 3, lane 4) evoked an increase in activity in both MMP-2 and MMP-9 gelatinases and presence of their active forms.

Figure 3.

Zymography of homogenates from control and breast cancer tissue. Lane 1: control extract (non-activated); lane 2: breast cancer extract (non-activated); lane 3: control extract (activated with APMA); lane 4: breast cancer extract (activated with APMA). The same amounts of pooled tissue extracts (n = 7) were run in each lane. Abbreviation: APMA, p-aminophenylmercuric acetate.

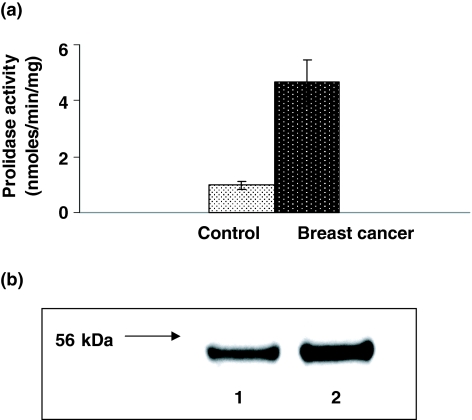

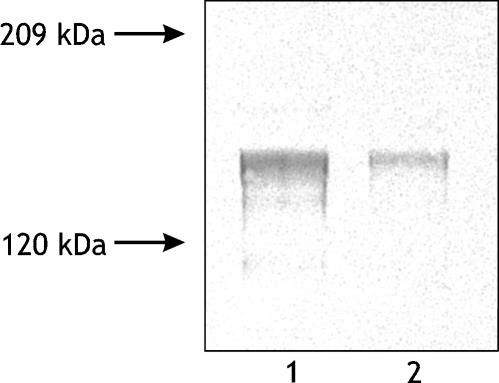

Increased MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities suggest that an enhanced degradation of collagen takes place in breast cancer tissue when compared with control. The disturbances in collagen metabolism in tumour tissue may affect turnover of collagen. Prolidase activity was found to be significantly increased in breast cancer tissue (Figure 4a) suggesting that collagen turnover rate was increased in tumour tissue compared with control. Western blot analysis for prolidase shows twofold increase in the expression of the enzyme in breast cancer tissue, compared with control one (Figure 4b). It suggests that distinct (fivefold) increase in the enzyme activity in breast cancer tissue (Figure 4a) may be due to increase in its phosphorylation.

Figure 4.

(a) Prolidase activity in the control and breast cancer tissue extract. Mean values from the tissue extract samples of seven patients ± SD are presented. P < 0.001. (b) Western immunoblot analysis of prolidase in the control (lane 1) and breast cancer (lane 2) tissue extract. Samples used for electrophoresis consisted of 30 μg of protein of pooled tissue extracts (n = 7).

Since prolidase activity is dependent on the interaction of collagen with the β1-integrin receptor subunit (Pałka & Phang 1997), we compared the expression of the receptor in control and breast cancer tissue extracts. A decrease in the expression of β1-integrins in breast cancer tissue was observed (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Western immunoblot analysis of β1-integrin receptor in the control (lane 1) and breast cancer (lane 2) tissue extract. Samples used for electrophoresis consisted of 30 μg of protein of pooled tissue extracts (n = 7).

Discussion

One of the consequences of neoplastic transformation is an aberration of the metabolism of some proteins of the extracellular matrix, mainly fibronectin and collagen (Hynes 1976; Slack et al. 1992). Collagen is the most abundant extracellular protein of vertebrates, predominantly produced by fibroblasts, but also synthesized and secreted by a variety of differentiated cells (Bornstein & Sage 1989). The interaction between cells and extracellular matrix proteins, e.g. collagen, can regulate cellular gene expression and differentiation, cell growth (Bissel 1981; Carey 1991), and can play an important role in tumorigenicity and invasiveness (Ruoslahti 1992). It has been shown that most normal and neoplastic cells recognize many extracellular proteins by specific cell surface receptors, called integrins. They are thought to be important for tumour cell attachment, migration, proliferation, progression and survival (Albelda & Buck 1990).

The results of this study show that the interaction between collagen and cell surface integrin receptors in breast cancer tissue is disturbed. First of all, there is a decrease in the tissue collagen content, presumably by increased degradation of this protein. In fact, an increased expression of MMP-2 (72 kDa) and MMP-9 (92 kDa) as well as their activity was found. Increased expression of gelatinases, including MMP-2 and MMP-9, during neoplastic transformation has been reported by other investigators (Nakajima & Chop 1991). Activation of gelatinases from zymogene precursors occurs via limited cleavage by other proteases, while suppression of their activity is accomplished by a variety of plasma and tissues inhibitors (Nakajima & Chop 1991). The technique of zymography offers a simple, yet sensitive, means of resolving the activated species from latent proenzyme and thereby provides additional data on the relationship between metalloproteinase activity and possible tumour progression. Since the conversion of the latent MMPs to activated species involves the proteolytic removal of a 10-kDa amino-terminal domain, the latent and activated forms can be resolved on the basis of size. Following separation, both latent and active species are restored to conformations that display gelatinolytic activity (Birkedal-Hansen & Taylor 1982). The latent species displays gelatinolytic activity because of the artificial conditions of the zymographic process. For instance, the 72-kDa species would be inactive under physiological conditions. Using this technique, an increased gelatinolytic activity in breast cancer tissue was found compared with control. Control tissue exhibited mostly the latent gelatinases, while breast cancer tissue contained also active forms of the metalloproteinases.

A decreased expression of β1-integrin receptor was found in breast cancer tissue when compared with control tissue. It is of interest, because β1-subunit is particularly important constituent of collagen-binding integrins, as α2β1 or α3β1 (Akiyama et al. 1990). The receptors bind both ECM proteins and intracellular cytoskeleton-associated proteins and provide means of cell anchorage needed for tissue organization and traction during migration (Ridley et al. 2003).

Deficiency of collagen and β1-integrin receptor in breast cancer tissue found in our study is accompanied by an increase in prolidase activity in this tissue. Western blot analysis for prolidase shows about twofold increase in the expression of the enzyme in breast cancer tissue, while the enzyme activity was increased by about fivefold, compared with the respective controls. It suggests that distinct increase in the enzyme activity in breast cancer tissue may be due to increase in its phosphorylation. At least in fibroblasts the enzyme activity increases upon its phosphorylation (Surażyński et al. 2001). Whether it is the case in breast cancer tissue remains to be elucidated. Our previous study suggested that prolidase activity is upregulated by signal induced by β1-integrin receptor (Pałka & Phang 1997). The decrease in the expression of β1-integrin receptor and increase in the enzyme activity in breast cancer tissue may be partially due to the increase in stromal and inflammatory cells in this tissue, compared with control one. It is known that inflammatory cells contain large amount of prolidase (Phang & Scriver 1989).

Previously, we have suggested that prolidase activity is depressed in MCF-7 cells as a result of disturbances in signalling mediated by β1-integrin–collagen interactions (Pałka & Phang 1998). In present report, we also suggest that there is a defect in β1-integrin–collagen interaction; however, it is not accompanied by a decrease in prolidase activity. The discrepancy between elevated activity of prolidase in breast cancer tissue and decreased activity of this enzyme in MCF-7 cells may be due to several metabolic and systemic processes that occur only in vivo. An example is the role of prolidase on collagen metabolism in wound healing (Senboshi et al. 1996). During wound healing platelets, immune cells (e.g. macrophages), lymphocytes and neurotrophils are exposed to collagen through β1-integrin receptor (Keely & Parise 1996; Hauzenberger et al. 1997; Romanic et al. 1997). A presumed upregulation of prolidase in these cells concomitant with the breakdown of collagen by collagenase released by some of these cells would recycle proline in the area of the wound. The proline would be used for fibroblast proliferation and the production of collagen in granulation tissue as well as for synthesis of immunoglobulins. The local production of immunoglobulins may be critical in immune response against bacterial organism. It is tempting to speculate that the constellation of abnormalities found in prolidase deficiency can be understood based on a defect in tissue microcosm with diverse cells.

It cannot be excluded that insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) may play an important role in regulation of balance between collagen synthesis, its degradation and prolidase activity. IGF-I is known as a potent stimulator of collagen biosynthesis and prolidase activity (Miltyk et al. 1998). Therefore, high increased prolidase activity in breast cancer tissue may occur by different mechanism than β1-integrin receptor signalling, probably by an increase in IGF-I receptor expression (Chen & Wong 2004). Upregulation of IGF-I receptor expression and signalling would also explain reduction in β1-integrin receptor, suggested by Lynch et al. (2005).

These results suggest that alteration in collagen metabolism in breast cancer tissue may reflect tissue remodelling, characteristic for invasive phenotype of cancer cells. Increased gelatinolytic and prolidase activities in breast cancer tissue may enhance stromal matrix degradation by enabling the tumour cells to modulate their own invasive behaviour and suggest that compounds endowed with gelatinolytic and prolidase inhibitory activities may be considered as potential therapeutic options in breast cancer treatment.

References

- Akiyama SK, Nagata K, Yamada KM. Cell surface receptors for extracellular matrix components. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1031:91–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(90)90004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albelda SM, Buck CA. Integrins and other cell adhesion molecules. FASEB J. 1990;4:2868–2880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendtsen O, Werb Z. Metalloproteinases regulate parietal endoderm differentiating and migrating in cultured mouse embryos. Dev. Dyn. 1997;208:255–265. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199702)208:2<255::AID-AJA12>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkedal-Hansen H, Taylor RE. Detergent-activation of latent collagenase and resolution of its component molecules. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1982;107:1173–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(82)80120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkedal-Hansen H, Moore WG, Bodden MK, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases. Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. 1993;4:197–250. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissel M. How does extracellular matrix direct gene expression. J. Theor. Biol. 1981;99:31–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein P, Sage H. Regulation of collagen gene expression. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1989;37:67–106. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey DJ. Control of growth and differentiation of vascular cells by extracellular matrix proteins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1991;53:161–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.001113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamson A, Voigtlander V, Myara I, Frey J. Collagen biosynthetic anomalies in prolidase deficiency: effect of glycyl-l-proline on the degradation of newly synthesized collagen. Clin. Physiol. Biochem. 1989;7:128–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WF, Wong MS. Genistein enhances insulin-like growth factor signaling pathway in human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:2351–2359. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinard FP. Photometric estimation of proline and ornithine. J. Biol. Chem. 1952;199:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerson KS, Phang JM. Hydrolysis of proline dipeptides completely fulfills the proline requirement in a proline-auxotrophic Chinese hamster ovary cell line. J. Nutr. 1993;123:909–914. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.5.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SI, Solomons CC, Muschenheim F, Macintyre CA, Miles B, O'Brien D. A syndrome resembling lathyrism associated with iminodipeptiduria. Am. J. Med. 1968;45:152–159. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(68)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauzenberger D, Klominek J, Holgersson J, Bergstrom SE, Sundqvist KG. Triggering of motile behavior in T lymphocytes via cross-linking of alpha 4 beta 1 and alpha L beta 2. J. Immunol. 1997;158:76–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RD. Cell surface proteins and malignant transformation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1976;458:73–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(76)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SH, Dennis AN, Greenberg M. Iminopeptiduria. A genetic defect in recycling collagen: a method for determining prolidase in red blood cells. Canad. Med. Assoc. J. 1975;113:759–763. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keely PJ, Parise LV. The alpha2beta1 integrin is a necessary co-receptor for collagen-induced activation of Syk and the subsequent phosphorylation of phospholipase Cgamma2 in platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26668–26676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch L, Vodyanik PI, Boettiger D, Guvakova MA. Insulin-like growth factor I controls adhesion strength mediated by α5β1 integrins in motile carcinoma cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:51–63. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltyk W, Karna E, Pałka J. Inhibition of prolidase activity by non-steroid antiinflammatory drugs in cultured human skin fibroblasts. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 1996;48:609–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltyk W, Karna E, Wołczyński S, Pałka J. Insulin-like growth factor I – dependent regulation of prolidase activity in cultured human skin fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1998;189:177–183. doi: 10.1023/a:1006958116586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock WL, Green PC, Boyer KD. Specificity and pH dependence for acrylproline cleavage by prolidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:1960–1965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myara I, Charpentier C, Lemonnier A. Optimal conditions for prolidase assay by proline colorimetric determination: application to imidodipeptiduria. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1982;125:193–205. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(82)90196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myara I, Charpentier C, Lemonnier A. Prolidase and prolidase deficiency. Life Sci. 1984;34:1985–1998. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myara I, Miech G, Fabre M, Mangeot M, Lemonnier A. Changes in prolinase and prolidase activity during CCL4 administration inducing liver cytosolic and fibrosis in rat. Br. J. Exp. Path. 1987;68:7–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Chop AM. Tumor invasion and extracellular matrix degradative enzymes: regulation of activity by organ factors. Cancer Biol. 1991;2:115–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pałka JA, Phang JM. Prolidase activity in fibroblasts is regulated by interaction of extracellular matrix with cell surface integrin receptors. J. Cell. Biochem. 1997;67:166–175. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19971101)67:2<166::aid-jcb2>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pałka JA, Phang JM. Prolidase in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Cancer Lett. 1998;127:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pałka JA, Miltyk W, Karna E, Wołczyński S. Modulation of prolidase activity during in vitro aging of human skin fibroblasts the role of extracellular matrix collagen. Tokai J. Exp. Clin. Med. 1996;21:207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pałka J, Karna E, Miltyk W. Fibroblast chemotaxis and prolidase activity modulation by insulin-like growth factor II and mannose 6-phosphate. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1997;168:177–183. doi: 10.1023/a:1006842315499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phang JM, Scriver CR. Disorders of proline and hydroxyproline metabolism. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw Hill; 1989. pp. 577–597. [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ, Udenfriend S. A specific method for the analysis of hydroxyproline in tissues and urine. Anal. Biochem. 1960;1:228–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(60)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid KBM, Porter RR. A collagen-like amino acid sequence in a polypeptide chain of human C1q (a subcomponent of the first component of complement) Biochem. J. 1976;155:19–23. doi: 10.1042/bj1410189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanic AM, Graesser D, Baron JL, Visintin I, Janeway CA, Jr, Madri JA. T cell adhesion to endothelial cells and extracellular matrix is modulated upon transendothelial cell migration. Lab. Invest. 1997;76:11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E. Control of cell motility and tumor invasion by extracellular matrix interaction. Br. J. Cancer. 1992;66:239–242. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senboshi Y, Oono T, Arata J. Localization of prolidase gene expression in scar tissue using in situ hybridization. J. Dermatol. Sci. 1996;12:163–171. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(95)00505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack JL, Parker MI, Robinson VR, Bornstein P. Regulation of collagen I gene expression by ras. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:4714–4723. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surazyński A, Pałka J, Wołczyński S. Phosphorylation of prolidase increases the enzyme activity. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2001;220:95–101. doi: 10.1023/a:1010849100540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woessner JF., Jr Determination of hydroxyproline in connective tissue. Meth. Enzymol. 1995;248:510–528. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]