Abstract

C-cell tumours of the thyroid gland are among the most common spontaneous neoplasms of the laboratory rat. With the exception of calcitonin, little attention has been paid to the secretory peptides of C cells during the development of neoplasia. Of these peptides, somatostatin (SS) is of particular interest because it has been shown to have a direct anti-secretory effect on both thyroid follicular and C cells in vitro. In the present study, in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry were used to investigate the expression of SS mRNA and SS peptides, in normal C cells and a range of spontaneous proliferative C-cell lesions in the Han Wistar rat. It was confirmed that a small minority of C cells in the normal rat thyroid gland produce and store SS peptides; however, approximately half of all C-cell adenomas and C-cell carcinomas stained positively for SS mRNA and peptides. SS expression was also observed in all metastatic deposits of carcinomas in drainage lymph nodes. From these observations, it appears that C-cell tumours are more likely to develop from SS-expressing stem cells, rather than from non-SS-expressing stem cells. In addition, a lack of differentiation of neoplastic C cells, or reversion to more primitive cell types, could account for increased number of cells expressing SS in C-cell tumours relative to the normal C-cell population. Finally, the mean percentage of cells that stained positively for SS mRNA and peptides appeared to be significantly higher in small C-cell tumours, suggesting that SS may have exerted a growth-controlling influence on these lesions.

Keywords: calcitonin, C-cell tumours, rat, somatostatin, thyroid gland

C-cell tumours of the thyroid gland are among the most common spontaneous neoplasms of the laboratory rat (Delellis 1994). Calcitonin (CT) is the major secretory product of normal C cells (MacIntyre 1989), and the presence of this peptide has been widely reported in C-cell tumours in this species (Triggs et al. 1975; Deftos et al. 1980; Hardisty & Boorman 1990). Other peptides are known to be produced by C cells, including somatostatin (SS), gastrin-releasing peptide and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (Zabel et al. 1987; Delellis 1994), but as yet little attention has been paid to these products and their possible role in the development of C-cell neoplasia. Of these peptides, SS is of particular interest because it has been shown to have a direct anti-secretory effect on both normal thyroid follicular and C cells in vitro (Endo et al. 1988; Sawicki 1995). Additionally, SS analogues are used in the treatment of thyroid tumours in humans and are reported to have beneficial effects in many cases (Robbins 1996).

Thomas et al.(1994) first showed that only a small proportion of normal C cells in the rat are capable of producing and storing SS. It was decided to extend this original work and investigate SS expression in C-cell hyperplasia (CCH) and neoplasia. Accordingly, in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) techniques were used to localize the sites of SS production (mRNA) and storage (peptide) in a range of C-cell proliferative lesions. The aim was to determine the proportion of these lesions that express SS peptides and whether the presence of SS markers are of potential value in the differential diagnosis of C-cell tumours. Also, as the role of SS in growth control is well recognized, at least in vitro (Robbins 1996; Medina et al. 1999), it was decided to carry out an initial investigation of the relationship between the expression of this peptide and the size and metastatic behaviour of the tumours.

Materials and methods

Animals and tissues

All proliferative lesions were taken from a background carcinogenicity study, of 30 months duration, involving untreated Han Wistar rats. In this carcinogenicity study, 280 male and 280 female rats (Small Animal Breeding Unit, Glaxo Group Research, Ware, Hertfordshire, UK), 4–5 weeks old, were housed in groups of four of the same sex, bedded on wood shavings and given food (Rat and Mouse No. 1, SDS Ltd, Witham, Essex, UK) and water ad libitum. A temperature of 22 °C ± 1 °C was maintained, with a relative humidity of 45–70% and a 12 : 12-h light : dark cycle (lights on at 06.00 hours). Animals were observed daily for signs of ill health. Thirty-two percent of the rats survived the 30-month study period with the remainder being killed for humane reasons at ages ranging between 18 and 29 months. Rats, in extremis and those surviving to autopsy, were killed by withdrawal of blood from the abdominal aorta under isoflurane anaesthesia. All animals were subjected to a full postmortem examination. Samples of major organs were retained and immersion fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for varying periods up to 1 month before being dehydrated through graded ethanol and xylene, embedded in paraffin wax and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). All tissues were subjected to a preliminary histological evaluation, and the thyroid glands from 25 male and 25 female rats (together with deep cervical lymph nodes where appropriate) were selected for further investigation. These glands were known to contain a range of C-cell proliferative lesions, and the 50 cases were chosen to provide a full range of lesions from hyperplasia through to metastatic carcinoma. Additionally, thyroid glands were obtained from three male and three female Han Wistar rats between 8 and 10 weeks of age (i.e. young adult animals), to allow the expression of SS and CT peptides to be evaluated in normal C cells. Serial sections, of 3-µm thickness, were cut from each thyroid or lymph node wax block onto precoated silanized slides (Superfrost, Shandon, Runcorn, UK), and numbered for the following staining procedures: (1) IHC for CT peptides, (2) ISH for SS mRNA and (3) IHC for SS peptides.

Probe

A single 42-base cDNA oligonucleotide probe, complementary to rat SS mRNA sequences (Montminy et al. 1984), was synthesized (Oswell DNA Service, Southampton, UK) and purified by high pressure liquid chromatography (Applied Biosystems 1991). The probe was labelled at the 5′- and 3′-end with a molecule of digoxigenin (Boehringer, Bracknell, Berkshire, UK). The sequence was as follows: 5′-ACAGGATGTGAATGTCTTCCAGAAGAAGTTCTTGCAGCCAGC-3′. This probe has been previously shown to demonstrate SS mRNA in normal thyroid C cells and pancreatic islet (D) cells in the rat (Thomas et al. 1994).

In situ hybridization procedure

The protocol used for ISH was based on that described elsewhere (Farquharson et al. 1990; Pilling et al. 1999). After rehydration, sections were pretreated in proteinase K (1 µg/ml for 40 min at 37 °C) and subsequently placed in a nonformamide containing prehybridization buffer [×4 Denhardt's solution, ×4 standard saline citrate (SSC), 83 µg/ml salmon testes DNA, 5 mg/ml sodium dodecyl sulphate, 4 mg/ml sodium pyrophosphate, 0.01 m Tris-HCl] for 1 h at 42 °C. The hybridization was carried out with the probe (0.3 ng/µl) diluted in this buffer overnight in a moist chamber at 42 °C. After washing in graded SSC, bound probe was localized with alkaline phosphatase-linked anti-digoxigenin antibody (Boehringer; 1 : 500 dilution) for 1 h. The final detection step was carried out overnight using nitroblue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK). Levamisole had been incorporated into this detection solution by the manufacturer in order to block any endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity. After dehydration and mounting, slides were examined and photographed using a Zeiss Axioskop microscope. A positive signal was demonstrated by the presence of a dark purple or black diformazan cytoplasmic reaction product. Negative control sections were (1) pretreated with RNAse A (100 µg/ml) before hybridization with labelled probe, (2) hybridized with inappropriate probe of similar length and C : G ratio (Escherichia coli, cytosine deaminase, 40-mer; R & D Ltd, Abingdon, Oxford) or (3) hybridized in the absence of labelled probe.

Antibodies

Both primary antibodies used in the IHC procedures were obtained from commercial suppliers and had been previously shown to work well against SS and CT peptides in the rat (Thomas et al. 1994).

Immunohistochemistry procedure

The protocol used for IHC was based on that described elsewhere (Pilling et al. 2002). The sections were dewaxed and incubated with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to inhibit endogenous peroxidases. Nonspecific protein binding was blocked using normal swine serum diluted 1 : 5 in Tris-buffered saline (0.05 m; pH 7.6). Sections intended for staining for SS peptides were subjected to antigen retrieval using boric acid (Wester et al. 2000). These slides were placed in 0.2 m boric acid (pH 7.0) in an incubator overnight at 60 °C. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against SS (1 : 500; Novocastra, Newcastle, UK) or CT (1 : 200; Novocastra) were applied to the sections overnight at 4 °C in a humidity chamber. After washing in Tris-buffered saline, biotinylated swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Igs) (1 : 100; DakoCytomation, Ely, Cambridgeshire, UK) were applied for 30 min. The slides were then incubated with StreptABComplex/HRP (DakoCytomation) for 30 min and developed using diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) and counterstained with Mayer's haematoxylin. A positive signal was indicated by the presence of a brown reaction product.

Negative control sections comprised: (1) omission of the primary antibody from the procedure and (2) replacement of the primary antibody with an isotype-matched control (normal rabbit Ig fraction; DakoCytomation). Sections of normal rat pancreas, containing islet (D) cells, were used as positive controls in the same way as for the ISH procedure.

Light microscopy

The diagnoses of C-cell lesions were based upon the Society of Toxicologic Pathologists (STP) classification scheme (Botts et al. 1991), the only exception being that the term ‘focal hyperplasia’ was not used. The principal diagnostic criteria were as follows:

(1) Diffuse C-cell hyperplasia (CCH). Increased number of C cells in interfollicular spaces. Minimal compression or distortion of thyroid follicles.

(2) C-cell adenoma. Discrete mass of C cells ranging from the size of one to two average follicular diameters to the occupation of the entire thyroid lobe but without penetration of the capsule (noninvasive).

(3) C-cell carcinoma. Solid sheets or irregular nests of C cells. Penetration of thyroid gland capsule, local invasion of adjacent tissues and/or vessels, and the presence of metastases.

For each ISH- or IHC-staining procedure, an assessment was made of the number of cells in the relevant population that were staining positively on the following five-point scale: grade 1, less than 20% positive cells; grade 2, 20–40% positive cells; grade 3, 40–60% positive cells; grade 4, 60–80% positive cells and grade 5, 80–100% positive cells. An evaluation of the overall staining intensity (weak, moderate or strong) of the cells was also performed. Finally, the greatest diameter of each C-cell adenoma and carcinoma was measured using an eyepiece graticule.

Results

Morphology of C-cell lesions

Diffuse C-cell hyperplasia

This lesion was observed in 49/50 thyroid glands investigated. In the one case where CCH was not recorded, a large C-cell adenoma was present but no normal glandular tissue was identified in the section. C-cell adenomas and carcinomas in the thyroid gland were invariably present in association with CCH. CCH was a diffuse lesion that consisted of cells surrounding the follicles, giving the impression of increased interfollicular tissue (Botts et al. 1991). Usually the accumulation was no more than two cells deep, and so overall, the follicular architecture was retained. The full extent of this lesion varied between animals, but typically it involved the entire central area of the thyroid lobe. CT peptides were identified in 49/49 CCH with almost all of the constituent cells in each lesion staining positively.

C-cell adenoma

This lesion was diagnosed in 14/25 males and 17/25 females (Table 1). C-cell adenoma was a discrete, well-demarcated growth (Botts et al. 1991), usually observed in association with CCH. Considerable size variation occurred with adenomas (diameter range: 0.2–8.7 mm in males and 0.2–4.8 mm in females). Some adenomas were small and equivalent in size to one to two average follicular diameters (focal hyperplasia in the STP nomenclature), with little compression or distortion of the adjacent follicles. Others were so large as to occupy virtually the entire thyroid lobe but without penetration of the capsule. The outline of the lesions was usually spherical but some had a more irregular, nodular appearance. Generally, C-cell adenomas were nonencapsulated and possessed scant stroma, although in a few of the larger lesions collagenous trabeculae were extensive. Additionally, in the larger lesions, there was frequent compression of surrounding follicles but no evidence of invasion. CT peptides were observed in all adenomas (Table 1). In all of these positive cases, the large majority of tumour cells showed strong positive staining for CT peptides.

Table 1.

Staining properties of C-cell adenomas in male and female Han Wistar rats 18–30 months old

| Number of positively stained cells | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | Size (mm) | CT peptides | SS mRNA | SS peptides |

| Males | ||||

| 1 | 7.2 | +++ | – | + |

| 2 | 8.7 | +++ | – | + |

| 3 | 0.3 | +++++ | – | – |

| 4 | 2.2 | +++++ | – | – |

| 5 | 0.4 | +++++ | NA | NA |

| 6 | 2.9 | +++++ | – | – |

| 7 | 0.8 | +++++ | – | – |

| 8 | 0.5 | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ |

| 9 | 1.2 | +++++ | + | + |

| 10 | 0.8 | +++++ | + | + |

| 11 | 1.0 | +++++ | – | – |

| 12 | 0.2 | +++++ | – | + |

| 13 | 0.7 | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ |

| 14 | 0.5 | +++ | ++++ | +++++ |

| Females | ||||

| 15 | 0.2 | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ |

| 16 | 0.4 | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ |

| 17 | 3.3 | +++++ | + | +++ |

| 18 | 1.6 | +++++ | – | – |

| 19 | 0.9 | ++++ | ++++ | +++++ |

| 20 | 4.2 | +++++ | – | + |

| 21 | 0.9 | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ |

| 22 | 0.6 | +++++ | NA | NA |

| 23 | 0.6 | +++++ | + | + |

| 24 | 0.5 | +++++ | – | – |

| 25 | 4.8 | +++++ | + | + |

| 26 | 1.4 | +++++ | – | + |

| 27 | 1.9 | +++++ | – | – |

| 28 | 3.4 | +++++ | ++ | ++ |

| 29 | 3.2 | +++++ | – | + |

| 30 | 1.1 | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ |

| 31 | 1.5 | +++++ | – | + |

CT, calcitonin; SS, somatostatin; –, no staining detected; +, less than 20% positive cells; ++, 20–40% positive cells; +++, 40–60% positive cells; ++++, 60–80% positive cells; +++++, more than 80% positive cells; NA, lesion disappeared from wax block at this level and therefore not available for assessment.

C-cell carcinoma

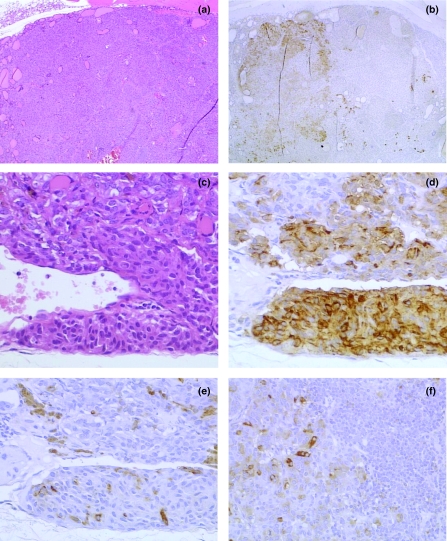

This lesion was recorded in eight out of 25 male rats but not in females (Table 2). In four out of eight cases, a separate C-cell adenoma was also present in the same gland. C-cell carcinoma shared many histological features with adenoma (as specified above), with the addition of several other characteristic findings. The most important of these was the presence of sheets of neoplastic cells exhibiting slight pleomorphism with increased cytoplasmic basophilia, fusiform shapes and many mitotic figures (Botts et al. 1991). Other important characteristics included haemorrhage, necrosis, invasion of the capsule (Figure 1c) and extension into the adjacent musculature. Metastatic deposits were identified in the cervical lymph nodes in association with three out of eight C-cell carcinomas. The morphological appearance of each metastasis was representative of that seen in the primary lesion. CT peptides were observed in all primary and metastatic C-cell carcinomas. In most cases, the majority of carcinoma cells gave strong positive signals for CT peptides (Figure 1d), although weak staining of scattered cells was observed in two such lesions.

Table 2.

Staining properties of C-cell carcinomas and metastases in male and female Han Wistar rats 18–30 months old

| Number of positively stained cells | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | Size (mm) | CT peptides | SS mRNA | SS peptides |

| Primary carcinoma | ||||

| 32 | 3.5 | ++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| 33 | 4.2 | +++++ | +++ | ++++ |

| 34 | 2.5 | +++++ | +++ | ++++ |

| 35 | 0.9 | +++++ | – | – |

| 36 | 4.0 | +++++ | – | + |

| 37 | 4.2 | + | – | – |

| 38 | 3.8 | + | +++ | +++ |

| 39 | 3.3 | +++ | ++++ | +++ |

| Metastasis | ||||

| 32 | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | |

| 33 | +++++ | + | ++ | |

| 34 | +++++ | + | ++ | |

| 35 | NP | |||

| 36 | NP | |||

| 37 | NP | |||

| 38 | NP | |||

| 39 | NP | |||

CT, calcitonin; SS, somatostatin; NP, lesion not present; –, no staining detected; +, less than 20% positive cells; ++, 20–40% positive cells; +++, 40–60% positive cells; ++++, 60–80% positive cells; +++++, more than 80% positive cells.

Figure 1.

C-cell tumours of the thyroid gland in the rat. (a) C-cell adenoma; haematoxylin and eosin-stained; large well-differentiated lesion. (b) Serial section to a; immunohistochemistry (IHC); mixed staining pattern with well-demarcated group of cells staining positively for somatostatin (SS) peptides (*), extending up to half the total area of the lesion. (c) C-cell carcinoma; haematoxylin and eosin-stained; pleomorphic cells invading gland capsule. Lesion contains many fusiform cells and trapped follicles. (d) Close section to c; IHC; most tumour cells staining positively for calcitonin peptides. (e), Serial section to d; IHC; few scattered cells staining positively for SS peptides. (f) Metastasis of C-cell carcinoma within cervical lymph node; IHC; scattered cells expressing SS peptides adjacent to resident lymphoid cells (*). Original magnifications: a and b ×25; c–f ×200.

Somatostatin expression

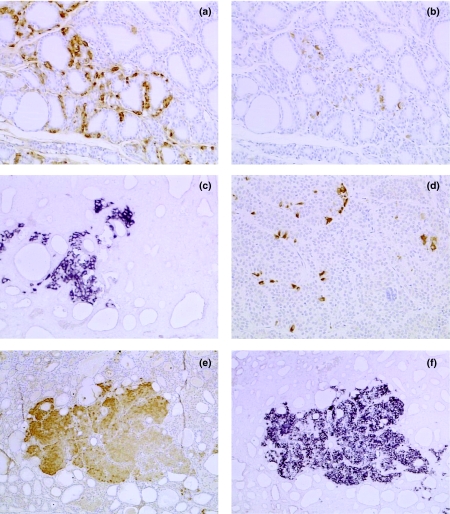

In three male and three female 8–10-week-old rats, SS mRNA and peptides were localized to cells with the morphology of C cells; however, they were present only in a small minority of such cells. All cells positive for SS mRNA, and present in serial sections, were also positive for SS and CT peptides, although not all cells positive for CT peptides were positive for SS. The SS-positive cells were present as strongly stained individual cells, or as small cell clusters (typically three to five cells), confined to a small part of the C-cell area (Figure 2a, b).

Figure 2.

Normal thyroid gland and proliferative C-cell lesions in the rat. (a) Young adult rat; immunohistochemistry (IHC); normal gland contains numerous C cells staining positively for calcitonin peptides. (b) Serial section to a; IHC; small number of C cells staining positively for somatostatin (SS) peptides. (c) C-cell hyperplasia; in situ hybridization (ISH); cluster of C cells expressing SS mRNA. (d) C-cell adenoma; IHC; scattered cells expressing SS peptides. (e) C-cell adenoma; IHC; 100% cells staining positively for SS peptides. (f) Serial section to e; ISH; 100% cells staining positively for SS mRNA. Original magnifications: a–d ×100; e and f ×50.

In the proliferative lesions, expression of SS mRNA was observed in 34/49 (69%) of CCH, 14/29 (48%) of C-cell adenomas and five out of eight (63%) of C-cell carcinomas. Cells positively stained for SS peptides were present in 42/49 (86%) of CCH, 21/29 (72%) of adenomas and six out of eight (75%) of carcinomas (Tables 1 and Tables 2). In all these lesions, cells positive for SS mRNA, and present in serial sections, were also positive for SS and CT peptides. However, as the above figures indicate, those lesions that were positive for both SS mRNA and peptides generally contained a higher number of peptide-positive cells. Additionally, a small number of lesions (eight) contained cells positive for SS peptides but were completely devoid of cells expressing SS mRNA. Generally, SS immunopositivity appeared as strong diffuse cytoplasmic staining, although the staining intensity for SS mRNA was more variable with some positive cells being weakly stained.

In those cases of CCH showing SS expression, the distribution of SS-positive cells was similar to that observed in the three male and three female young adult rats, in that scattered cells and loose cell clusters were present, although many of the latter were considerably larger in the CCH cases than in the six young adult rats (Figure 2c).

In C-cell adenomas, four different staining patterns of SS-positive (mRNA or peptide) cells were observed:

Individual, widely scattered cells and loose cell clusters (Figure 2d): This was the most common pattern, present in 11/29 (38%) cases. This pattern was identical to that seen in the six young adults and CCH.

Hundred percent of cells staining positively for SS peptides (Figure 2e, f): This pattern was seen in eight out of 29 (28%) of C-cell adenomas.

Hundred percent of cells showed no staining for SS peptides: This was observed in eight out of 29 (28%) of adenomas.

Mixed pattern, comprising a well-delineated group of contiguous SS-positive cells, variably occupying between 50 and 75% of the area of the lesion (Figure 1a, b): This was seen in two out of 29 (6%) adenomas.

In five out of eight C-cell carcinomas, large number of cells stained positively for SS peptides. These cells were usually isolated and scattered across the lesion (Figure 1e). The associated lymph node metastases also contained widely scattered SS-positive cells (Figure 1f), but overall, these tended to be fewer in number than at the primary site. Similar patterns of staining were noted for SS mRNA, although in most instances, the number of positive cells was fewer than for peptide. Two out eight carcinomas were completely negative for both SS mRNA and peptides.

Strong signals for SS mRNA and peptides were observed in pancreatic islets used as positive controls, whereas no staining was present in all the negative controls.

Relationship of SS expression with tumour size

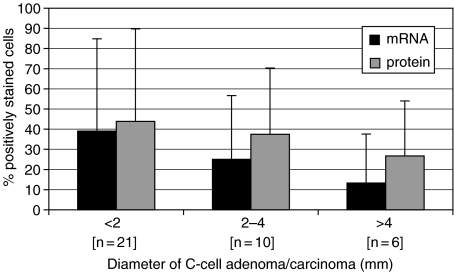

The diameters of C-cell adenomas/carcinomas ranged from 0.2 to 8.7 mm, with the majority being less than 2 mm (the mean midlongitudinal length of the fixed Han Wistar thyroid gland from six young adult rats was 4.5 mm). The mean percentage of cells that stained positively for SS mRNA and peptides in C-cell adenomas and carcinomas showed considerable variation between individual animals, but there was a general trend for a reduction in accordance with increasing size of the lesion (Figure 3). An average of 39% of cells stained positively for SS mRNA in tumours less than 2 mm in diameter, whereas 13.3% of cells showed positive staining in lesions greater than 4 mm. Cells staining positively for SS peptides showed a similar trend, with a mean of 43.8% present in lesions less than 2 mm and 26.7% present in lesions over 4 mm.

Figure 3.

Mean (SD) percentage of cells expressing SS mRNA or somatostatin peptides in C-cell tumours (adenoma and carcinoma) by diameter of lesion. All tumours included.

Discussion

SS has been identified in many tissues and is thought to exert several different biological actions, including the inhibition of hormone secretion and the regulation of cell proliferation (Reichlin 1983; Medina et al. 1999). Immunoreactive SS has been detected in C cells, in the normal thyroid gland of rodents (Thomas et al. 1994), leading to speculation that the peptide could elicit local effects on thyroid hormone release and therefore act in a paracrine fashion (Van Noorden et al. 1977). Furthermore, SS has been shown to have a direct anti-secretory effect on both normal thyroid follicular and C cells in vitro (Endo et al. 1988; Sawicki 1995). However, to date such effects have not been confirmed in vivo. As yet, SS does not appear to have been detected in normal human C cells, although it has been localized in human C-cell tumours (medullary thyroid carcinoma) (Roos et al. 1981; Neonakis et al. 1994). Additionally, the presence of SS receptors has been established in medullary thyroid carcinomas (Reubi et al. 1991; Papotti et al. 2001), but again the precise role of SS has not been confirmed.

In the present study, ISH and IHC were used to determine the (cell specific) sites of SS production (mRNA) and storage (peptide) in a range of C-cell proliferative lesions. For comparative purposes, SS expression was also evaluated in C cells of young adult rats, i.e. C cells in the nonproliferative state. ISH and IHC have been used previously to detect SS expression in murine tumours (Ouazzani et al. 1994), although the present investigation is the first occasion, they have been systematically applied in the rat to a range of tissues from normal, through hyperplasia and adenoma, to malignant lesions with metastatic deposits.

The resident hormonal product, CT, is generally regarded as the most important specific marker of C cells and is considered a prerequisite for the diagnosis of C-cell neoplasia in humans (Delellis et al. 1978; Albores-Saavedra et al. 1985; Ljungberg 1993). Accordingly, the presence of CT peptides was used to confirm that the lesions under investigation were indeed of C-cell origin. Diagnoses of C-cell lesions were based upon STP guidelines (Botts et al. 1991) (nomenclature which is widely used in toxicological pathology), although it was decided not to use the term ‘focal hyperplasia’ but to classify all solid aggregates of cells smaller in size than five average follicular diameters as ‘adenoma’. This was done principally because the distinction between ‘focal hyperplasia’ and ‘adenoma’, in accordance with Botts et al. (1991), is somewhat arbitrary, being based purely on size. No biological differences appear to have been identified between these two states. Furthermore, it is accepted that focal hyperplasia and adenoma (as defined in STP guidelines) are different stages of progression in the course of C-cell proliferation (Delellis et al. 1979). For these reasons, it seemed appropriate to regard these stages as one entity for the purposes of the present investigation.

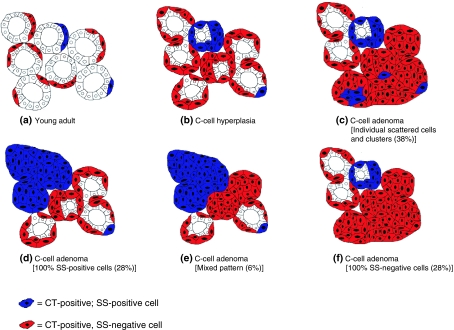

The observation that only a very small proportion of C cells in the young adult rat contain SS mRNA and peptides is consistent with the findings of Thomas et al.(1994), who proposed that C cells in this species differentiate into two subsets, only one of which is able to produce and store SS. In young adult rats in the present study, the SS-positive cells were noted as individual scattered cells, or in small cell clusters, the latter typically in the form of three to five cells encircling a follicle. In CCH, however, these clusters had expanded to approximately 50–100 cells although they still conformed to the definition of hyperplasia, i.e. ‘cells surrounding the follicles, giving the impression of increased interfollicular tissue’.

In C-cell adenomas, the situation became more complex, as four distribution patterns appeared to exist; these are illustrated diagramatically in Figure 4. In descending order of frequency the patterns were: (1) individual scattered SS-positive cells/clusters (38%); (2) 100% SS-positive cells (28%); (3) 100% SS-negative cells (28%) and (4) a mixed pattern of staining for SS-positive and -negative cells (6%). In the most frequent distribution pattern (38% of cases), SS expression was observed in individual, widely scattered cells and cell clusters. All of these cells were positive for SS peptides, although many showed no staining for mRNA.

Figure 4.

Summary of distribution patterns for somatostatin immunopositive cells in young adult rats and C-cell adenomas. Figures in parentheses denote the incidence of each pattern identified in the present investigation.

A possible explanation for this distribution of positive cells is that, although having developed by clonal expansion of an SS-negative stem cell, the expression of SS by tumour cells is taking place as a result of the lack of cellular differentiation. In this way, the failure to differentiate and to express SS peptides will occur sporadically, and the affected cells will be scattered throughout the lesion. A precedent for this occurs in other neuroendocrine cell tumours, e.g. tumours of the human pancreatic islets (Philippe et al. 1988). In normal islets, the majority of cells express insulin, with other peptides (e.g. SS and glucagon), being restricted to a small minority of cells. In islet cell tumours, it has been shown that many cells co-express more than one peptide including SS and glucagon. This has been attributed to the islet cell tumours exhibiting a less differentiated state (de-differentiation) where the neoplastic cells are capable of simultaneously synthesizing multiple peptides (Philippe et al. 1988). Alternatively, the over-expression of SS could represent a reversion to more primitive cell types if SS is consistently produced by immature or fetal C cells, although whether this is true is not known. The latter situation would be analogous to the expression of α-fetoprotein (AFP) by neoplastic hepatocytes. AFP is normally synthesized by fetal hepatocytes but not by fully differentiated adult cells; however, following neoplastic transformation, strong AFP expression is frequently observed (Nayak & Mital 1977).

The presence of 100% SS-positive cells in a C-cell adenoma is consistent with the lesion having developed from the clonal expansion of an SS-expressing stem cell. Likewise, the complete absence of SS expression in such a lesion is consistent with development from an SS-negative stem cell. However, as the ratio of SS-negative : SS-positive cells in the young adult rat thyroid gland is approximately 10 : 1 (Thomas et al. 1994), it is surprising that so many 100% SS-positive tumours were identified in the present investigation. Indeed, the ratio of 100% SS-negative : 100% SS-positive tumours in the present study was approximately 1 : 1. The implication of this observation is that C-cell tumours are more likely to develop from SS-expressing stem cells (i.e. positive) rather than from non-SS-expressing (i.e. negative) stem cells. The reasons why this should be so are unclear and worthy of further investigation.

Finally, a mixed pattern of staining of SS-positive and SS-negative cells was observed in two adenomas (Figure 2a, b). Each of these lesions comprised a large group of contiguous SS immunopositive cells occupying approximately half the area of the lesion, whereas the other half was made up of negative cells. However, many of the SS immunopositive cells stained negatively for SS mRNA. Again, a lack of differentiation, within a single clone of cells, could explain SS expression in half of the lesion. A second explanation might be that the mixed pattern has formed by the merger of two proliferative lesions, each having risen independently from SS-expressing and non-SS-expressing stem C cells. Such a merger has been referred to as the collision effect (Hall & Levison 1989).

The reasons for the significant number of cells within the proliferative lesions which are mRNA negative and peptide positive, in terms of SS expression, are unclear. Firstly, it may be due to the very low rate of production of the SS peptide. Alternatively, a lack of sensitivity of the ISH procedure should be considered, as the ISH technique used for the detection of SS mRNA in the present study involved a single oligonucleotide probe. The latter is relatively insensitive as compared with other probe systems which could have been used, e.g. riboprobes (Leitch et al. 1994; Hougaard et al. 1997). Therefore, the levels of SS mRNA present in the cells in these tumours may have been below the threshold of sensitivity for the ISH technique employed.

The present results indicate the limited usefulness of SS as a diagnostic marker for C-cell neoplasia in the rat. As CT peptides were present in all C-cell tumours under investigation, CT is unlikely to be replaced by SS as the marker of choice. Seeing as SS peptides were present in all C-cell metastases, the presence of SS could be viewed as a useful alternative or complementary marker in such secondary deposits. However, as only three metastases were identified in the present study, further confirmation is needed, ideally from a larger number of cases.

The role of SS as a growth-controlling peptide is well recognized (Medina et al. 1999), and therefore one of our aims was to examine whether SS production by C cells could influence the development of tumours of this type. Although considerable intertumour variation was present in this study (due to the different staining patterns described above), it was apparent (Figure 3) that smaller lesions (<2 mm) appeared to contain significantly more cells staining positively for SS mRNA and peptides than larger lesions (>4 mm). Therefore, it is possible to speculate that SS can inhibit the growth of C-cell tumours, although more work is necessary to substantiate these findings. A growth inhibitory effect of SS is supported by the work of Ouazzani et al.(1994), who demonstrated low proliferative activity in a small number of SS-positive C-cell tumours in the rat, as measured by tritiated thymidine uptake. Unfortunately, these authors did not identify any SS receptors in the tumours and concluded that a direct autocrine or paracrine regulatory effect of the peptide should be ruled out.

In conclusion, in the present study, it has been demonstrated that although a small minority of C cells in the normal rat thyroid gland produce and store SS peptides, approximately half of all primary C-cell tumours, and all metastatic deposits show evidence of SS expression. In many cases, this may be due to the lack of differentiation of the neoplastic cells or the assumption of a more primitive phenotype that is capable of producing alternative peptides. As the degree of SS expression appeared to be considerably higher in small C-cell lesions, it is possible that this peptide was exerting a growth-controlling influence on these lesions.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Helen Endersby-Wood and Nicola McCormack.

References

- Albores-Saavedra J, Livolsi VA, Williams ED. Medullary carcinoma. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 1985;2:137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applied Biosystems. Model 373a User Bulletin. Foster City, California, USA: Applied Biosystems Inc; 1991. Extension primers: recommendations for sequence selection, synthesis, and purification; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Botts S, Jokinen MP, Isaacs KR, Meuten DJ, Tanaka N. Guides for Toxicologic Pathology. Washington, DC: STP/ARP/AFIP; 1991. Proliferative lesions of the thyroid and parathyroid glands; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Deftos LJ, Bone HG, Parthemore JG. Immunohistological studies of medullary thyroid carcinoma and C cell hyperplasia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1980;5:857–862. doi: 10.1210/jcem-51-4-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delellis RA. Changes in structure and function of thyroid C cells. In: Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Capen CC, editors. Pathobiology of the Aging Rat. Vol. I. Washington, DC: ILSI Press; 1994. pp. 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Delellis RA, Nunnemacher G, Bitman WR, et al. C-cell hyperplasia and medullary thyroid carcinoma in the rat. Lab. Invest. 1979;40:140–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delellis RA, Rule AH, Spiler I, Nathanson L, Tashjian AH, Wolfe HJ. Calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen as tumor markers in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1978;70:587–594. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/70.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Saito T, Ushida T, Onaya T. Effects of somatostatin and serotonin on calcitonin secretion from cultured rat parafollicular cells. Acta. Endocrinol. 1988;117:214–218. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1170214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquharson M, Harvie R, McNichol AM. Detection of messenger RNA using a digoxigenin end labelled oligodeoxynucleotide probe. J. Clin. Pathol. 1990;43:424–428. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.5.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall PA, Levison DA. Biphasic tumours: clues to possible histogenesis in developmental processes. J. Pathol. 1989;159:1–2. doi: 10.1002/path.1711590102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardisty JF, Boorman GA. Thyroid Gland. In: Boorman GA, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, editors. Pathology of the Fischer Rat. San Diego: Academic Press Inc; 1990. pp. 519–536. [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard DM, Hansen H, Larsson L-I. Non-radioactive in situ hybridization for mRNA with emphasis on the use of oligodeoxynucleotide probes. Histochem. Cell Biol. 1997;108:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s004180050174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch AR, Schwarzacher T, Jackson D, Leitch IJ. In Situ Hybridization. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publishers; 1994. Denaturation, hybridization and washing; pp. 55–61. Royal Microscopical Society Microscopy Handbooks, No. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ljungberg O. Tumours of the thyroid/parathyroid glands. In: Polak JM, editor. Diagnostic Histopathology of Neuroendocrine Tumours. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. pp. 167–202. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre I. Calcitonin: physiology, biosynthesis, secretion, metabolism and mode of action. In: Degroot LJ, editor. Endocrinology. Vol. II. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1989. pp. 892–901. [Google Scholar]

- Medina DL, Velasco JA, Santisteban P. Somatostatin is expressed in FRTL-5 thyroid cells and prevents thyrotropin mediated down-regulation of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p27kip1. Endocrinology. 1999;140:87–95. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.1.6426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montminy MR, Goodman RH, Horovitch SJ, Habener JF. Primary structure of the gene encoding rat preprosomatostatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:3337–3340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak NC, Mital I. The dynamics of α-fetoprotein and albumin synthesis in human and rat liver during normal ontogeny. Am. J. Pathol. 1977;86:359–370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neonakis E, Thomas GA, Davies HG, Wheeler MH, Williams ED. Expression of calcitonin and somatostatin peptide and mRNA in medullary thyroid carcinoma. World J. Surg. 1994;18:588–593. doi: 10.1007/BF00353772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouazzani L, Reubi JC, Volle GE, et al. Evaluation of somatostatin biosynthesis, somatostatin receptors and tumor growth in murine medullary thyroid carcinoma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1994;131:522–530. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1310522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papotti M, Kumar U, Volante M, Pecchioni C, Patel YC. Immunohistochemical detection of somatostatin receptor types 1–5 in medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. Clin. Endocrinol. 2001;54:641–649. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe J, Powers AC, Mojsov S, Drucker DJ, Comi R, Habener JF. Expression of peptide hormone genes in human islet cell tumors. Diabetes. 1988;37:1647–1651. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilling AM, Harman R, Jones S, McCormack N, Lavender D, Haworth R. The assessment of local tolerance, acute toxicity, and DNA biodistribution following particle-mediated delivery of a DNA vaccine to minipigs. Toxicol. Pathol. 2002;27:678–688. doi: 10.1080/01926230252929864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilling AM, Mifsud NAM, Jones SA, Endersby-Wood HJ, Turton JA. Expression of surfactant protein mRNA in normal and neoplastic lung of B6C3F1 mice as demonstrated by in situ hybridization. Vet. Pathol. 1999;36:57–63. doi: 10.1354/vp.36-1-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichlin S. Somatostatin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983;309:1495–1563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312153092406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Chayvialle A, Franc B, Cohen R, Calmettes C, Modigliani E. Somatostatin receptors and somatostatin content in medullary thyroid carcinomas. Lab. Invest. 1991;64:567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins RJ. Somatostatin and cancer. Metabolism. 1996;45:98–100. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos BA, Lindall AW, Ells J, Elde R, Lambert PW, Binbaum RS. Increased plasma and tumor somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in medullary thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1981;52:187–194. doi: 10.1210/jcem-52-2-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki B. Evaluation of the role of mammalian thyroid parafollicular cells. Acta. Histochem. 1995;97:389–399. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(11)80064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GA, Neonakis E, Davies HG, Wheeler MH, Williams ED. Synthesis and storage in rat thyroid C-cells. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1994;42:1055–1060. doi: 10.1177/42.8.7913105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triggs SM, Hesch RD, Woodhead JS, Williams ED. Calcitonin production by rat thyroid tumours. J. Endocrinol. 1975;66:37–43. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0660037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Noorden S, Polak JM, Pearse AGE. Single cellular origin of somatostatin and calcitonin in the rat thyroid gland. Histochem. 1977;53:243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00511079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wester K, Wahlund E, Sundstrom C, et al. Paraffin section storage and immunohistochemistry. Effects of time, temperature, fixation, and retrieval protocol with emphasis on p53 protein and MIB1 antigen. Appl. Immunohistochem. Molecul. Morph. 2000;8:61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel M, Surdyk J, Biela-Jacek I. Immunocytochemical studies on thyroid parafollicular cells in postnatal development of the rat. Acta Anat. 1987;130:251–256. doi: 10.1159/000146492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]