Abstract

The dogma that adult tissue-specific stem cells remain committed to supporting only their own tissue has been challenged; a new hypothesis, that adult stem cells demonstrate plasticity in their repertoires, is being tested. This is important because it seems possible that haematopoietic stem cells, for example, could be exploited to generate and perhaps deliver cell-based therapies deep within existing nonhaematopoietic organs.

Much of the evidence for plasticity derives from histological studies of tissues from patients or animals that have received grafts of cells or whole organs, from a donor bearing (or lacking) a definitive marker. Detection in the recipient of appropriately differentiated cells bearing the donor marker is indicative of a switch in phenotype of a stem cell or a member of a transit amplifying population or of a differentiated cell. In this review, we discuss evidence for these changes occurring but do not consider the molecular basis of cell commitment.

In general, the extent of engraftment is low but may be increased if tissues are damaged. In model systems of liver regeneration, the repeated application of a selection pressure increases levels of engraftment considerably; how this occurs is unclear. Cell fusion plays a part in regeneration and remodelling of the liver, skeletal muscle and even regions of the brain.

Genetic disease may be amenable to some forms of cell therapy, yet immune rejection will present challenges. Graft-vs.-host disease will continue to present problems, although this may be avoided if the cells were derived from the recipient or they were tolerized. Despite great expectations for cellular therapies, there are indications that attempts to replace missing proteins could be confounded simply by the development of specific immunity that rejects the new phenotype.

Keywords: adult stem cells, cell fusion, cell therapy, immune rejection, plasticity, tissue regeneration

Adult stem cells

Stem cell populations exist in a variety of adult tissues. Haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (Lemischka et al. 1986) are the best characterized; this knowledge has allowed therapeutic grafting to make a tremendous impact on haematological malignancy and offers great promise for haemoglobinopathies and other genetic disease where the phenotype can be corrected in blood or endothelium. Cord blood banking is increasingly commonplace to provide an effective HSC reserve for individual and altruistic purposes, and some consider that graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD) might be avoided if HSCs from the donor were used to establish microchimaerism, because this would allow the transplant to be accepted as self (Down & White-Scharf 2003).

Several other adult stem cell populations are recognized and partially characterized, for example, in the gut (Brittan & Wright 2002), skin (Braun et al. 2003) and hair (Oshima et al. 2001), but little is known of stem cells in the kidney and hair follicle (Al-Awqati & Oliver 2002). These adult stem cells have in common a low rate of cell division, the ability to self-renew and to generate through intermediate transit amplifying populations all specialized differentiated cell types specific to the tissue. They are capable of replenishing these cells in appropriate numbers and proportions in response to ‘wear and tear’ loss and direct organ damage.

For example, stem cells in the crypts of the mucosa of the intestine elaborate Paneth, goblet, enteroendocrine and absorptive epithelial cells, with patterns of gene expression that vary according to their position along the crypt, villus axis and with a cell repertoire that varies with their location along the intestine with Paneth cells normally absent from the large intestine (Brittan & Wright 2002). Control over the rate of production of new cells is exerted by regulating the balance of proliferation and apoptosis of transit-amplifying cells.

Can adult cells be reprogrammed?

In schemes such as that shown in Figure 1, the orderly amplification and differentiation of cells from their precursors is presented as an irreversible process, but this seems not to be the case and there are examples where cells representing different positions in the hierarchy are seen to lose their commitment to a specified purpose. In some instances, the change is small, affecting only one cell, and in others, the switch results in the production of an alternative lineage, or potentially a whole organism.

Figure 1.

Possible routes for cell phenotype switches through the mechanisms of: transdetermination (A), transdifferentiation (B) and dedifferentiation and redifferentiation (C). Transdetermination (A) occurs when a stem/or progenitor cell which is determined to generate cells of a certain lineage switches to another stem/or progenitor cell state and generates descendants of the latter lineage. For example, transdetermination can be seen when cells are transplanted between imaginal discs in Drosophila larvae (Maves & Schubiger 1999). Transdifferentiation (B) occurs when a fully differentiated cell takes on another differentiated phenotype, often without cell division, examples of transdifferentiation can be seen in the conversion of pigment epithelia into lens and neural retina cells (Tsonis 2000; Del Rio-Tsonis & Tsonis 2003) or cultured pancreatic cells to hepatic cells (Shen et al. 2003) Dedifferentiation (C) occurs when a cell switches lineage by first dedifferentiating to a common stem or progenitor cell and redifferentiating along a different tissue lineage, an example of this is seen after limb amputation in amphibians, which leads to dedifferentiation of local myocytes, followed by regeneration of cells of different lineages (Tsonis 2000; Nye et al. 2003). PS, pluripotential stem cell; TA, transit-amplifying cell; TD, terminally differentiated cell; TS, tissue-specific stem cell.

There are three conceptually different methods for a cell to switch lineage in vivo: transdifferentiation, transdetermination and dedifferentiation (Frisen 2002).

Transdifferentiation is the situation where a fully differentiated cell takes on another differentiated phenotype, often without cell division. For example, individual cells in culture can be observed to transdifferentiate from pancreatic to hepatic characteristics in response to changing the composition of the culture medium (Shen et al. 2003); in vivo lens epithelial cells transdifferentiate from retinal pigment cells after eye injury in newts (Tsonis 2000; Del Rio-Tsonis & Tsonis 2003) and transdifferentiation of smooth muscle cells to skeletal myocytes occurs in the oesophagus during normal mammalian development (Patapoutian et al. 1995).

Transdetermination defines the process where a stem or progenitor cell which is determined to generate cells of a certain lineage switches to another stem cell state and generates descendants of the second lineage. An example of this can be seen when cells are transplanted between imaginal discs in Drosophila larvae (Maves & Schubiger 1999). Isolated, cultured neural stem cells are not restricted to neural programs, because when introduced into mouse blastocyts or chick embryos, they can contribute functional progeny to all layers of the embryo (Clarke et al. 2000). Similarly, multipotent adult progenitor cell (MAPC) lines isolated from mouse, rat or human mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) cultures can contribute to most if not all somatic cell types (Jiang et al. 2002).

Dedifferentiation describes the process when a cell switches lineage by first reverting to a common stem or progenitor cell and then redifferentiating along another tissue lineage; for example, after limb amputation in newts, which leads to dedifferentiation of local myocytes, followed by regeneration of cells of other lineages (Tsonis 2000; Nye et al. 2003). Under these circumstances, stem cells, progenitor cells or even more differentiated cells would undergo genetic reprogramming when removed from their usual niche and introduced into a different microenvironmental niche. In mouse hair follicles, a proportion of the transit-amplifying population that migrates out from the niche retains sufficient self-renewing capability to regain function as hair stem cells if it occupies vacated niches; in this system, the niche has a dominant role in determining the fate of its stem cell progeny (Nishimura et al. 2002).

In the Drosophila ovariole, the reprogramming ability of an empty germ-line stem cell niche is again noticeable but seems to have limitations; after being emptied experimentally, the fate of the incoming cells is not changed, and only certain incoming cells are stimulated to divide. Thus, the growth-promoting action of this particular stem cell niche is restricted, requiring a matched companion cell to result in stem cell activity (Kai & Spradling 2003).

Metaplastic and heterotopic changes, from one recognizable tissue phenotype to another, are recognized in pathology and are mostly in tissues with a high turnover of cells (Slack 1985); such changes may result from genetic or epigenetic changes that affect expression of transcription factors (Slack & Tosh 2001). For example, overexpression of the transcription factor cdx2 targeted to gastric epithelium results in islands of intestinal metaplasia (Silberg et al. 2002); conversely, the absence of cdx2 expression in cdx2 null: wild-type chimaeric mice results in patches of cdx2 null gastric phenotype within wild-type colonic mucosa (Beck et al. 2003); importantly, the junctional epithelium had the phenotype of small intestinal mucosa, despite being of wild-type heritage, and hence, their local stem cell units had adopted a specific relevant program of differentiation due to their location.

The ultimate demonstration of reprogramming is that a nucleus from a terminally differentiated adult cell can be reprogrammed within an enucleated oocyte and manipulated to produce a cloned organism, such as Dolly, the sheep (Campbell et al. 1996). The process has been applied to several other mammals (Wilmut & Paterson 2003) including mice, cattle, goats, pigs, cats, rats, mules and horses, although it should be appreciated that the procedures have raised significant ethical concerns (and are banned in humans) and have a high failure rate, and there are uncertainties over the integrity of the genomes in cloned animals (Rhind et al. 2003).

Adult stem cell plasticity

Consideration of the preceding section leads to the hypothesis that stem cell credentials (whether intrinsic to the cell or defined partially by environmental and niche factors) may be acquired or are transferable, and then, it seems unreasonable to exclude the possibility that a transplanted cell could change its phenotype.

Do tissue-specific stem cells change their purpose normally, without intervention? It is very hard to test this because of the need for a marker of cell origin to show that the new lineage is derived from the old. There is much evidence to support the belief that transplanted whole adult bone marrow is capable of contributing significant numbers of differentiated cells to other organs (Poulsom et al. 2002; Korbling & Estrov 2003; Prockop et al. 2003). There is evidence that HSC and MSC have specific potentials, but that MAPC (Jiang et al. 2002) appears to have a greater repertoire. Judged mostly by morphological, immunohistochemical and chromosome detection methods, it is reported that complete or partial haematopoietic engraftment with whole bone marrow or FACS/immunologically sorted HSC-rich populations, or even a single sorted/homed/reselected HSC (Krause et al. 2001), results in the generation of numerous differentiated cell types in diverse tissues. Most studies have focused on epithelia, although whole bone marrow transplants in mice produce a substantial engraftment of myofibroblast and fibroblast populations (Brittan et al. 2002; Direkze et al. 2003). These studies have extended observations made originally by Friedenstein (Friedenstein et al. 1978) who established that bone marrow stromal cells are precursors of fibroblastic cells with multiple potentials (including a contribution to the HSC niche and to bone) and also Bucala (Bucala et al. 1994) who established that circulating fibroblast precursors exist, which are attracted to sites of damage (Abe et al. 2001).

A switch towards blood lineages has been described for cells isolated from muscle (Jackson et al. 1999) and brain (Bjornson et al. 1999). Subsequent studies (Kawada & Ogawa 2001; Issarachai et al. 2002; McKinney-Freeman et al. 2002) suggested that the cells with haematopoietic potential residing in muscle are itinerant bone marrow-derived cells. However, a study describing a similar haematopoietic potential of cells cultured from rodent hair described how no blood-forming cells could be cultured from aorta which is more likely to be exposed to circulating HSC (Lako et al. 2002). The answer may lie in the observation that adult bone marrow-derived cells are capable of engrafting mature muscle via satellite cells (Labarge & Blau 2002). Thus, satellite cells have both muscle and haematopoietic potentials depending on the niche they find themselves in.

Studies of transplanted liver (Alison et al. 2000; Theise et al. 2000), kidney (Poulsom et al. 2001; Gupta et al. 2002a, 2002b; Kale et al. 2003), heart (Muller et al. 2002; Orlic et al. 2001) and lung (Kleeberger et al. 2003) also support the existence of circulating cells, perhaps from the bone marrow of the recipients, acting as precursors for the parenchymal populations of allografts, and also for some renal interstitial and endothelial cells (Williams & Alvarez 1969; Grimm et al. 2001).

In the majority of reports, parenchymal engraftment within intact or minimally damaged tissues is reported to be at a low level (around 1 per million), with donor-derived cells found scattered through the tissues examined. As clusters were not observed, it remains possible, if not likely, that each cell detected had individually experienced a phenotype switch, rather than each being progeny of a new donor-derived tissue-specific stem cell that had become reprogrammed locally (Figure 1). Clonal expansion seems so far to be observed only in the fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (fah)-null mouse (Lagasse et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2002) discussed below.

Is plasticity a response to damage?

Freshwater planarians and some microturbellarians show high powers of regeneration associated with cells called neoblasts. These are label-retaining stem cell candidates whose progeny migrate through the body and differentiate into various somatic cell types and even into germ cells (Ladurner et al. 2000).

Could mammals also have a back-up system to support repair processes when local stem cell populations are failing? Such an axis for repair may account for observations in kidney (Kale et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2003) and liver (Mallet et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2002) that the bone marrow contribution to epithelia is greater when damage is caused or selection pressures are applied. There is some evidence for targeted recruitment involving signalling between stromal-derived factor (SDF)-1-α and CXCR4, a pairing which normally mediates the migration of haematopoiesis from the developing kidney and liver to bone marrow. The receptor CXCR4 is expressed by HSC-derived oval cell liver precursors (Hatch et al. 2002); damage such as ischaemia acts to mobilize HSC into the peripheral circulation that may then become engrafted (Kale et al. 2003). SDF-1 (expressed artificially within cardiac muscle) is sufficient to induce targeting of mobilized CD117-positive stem cells to injured myocardium (Askari et al. 2003).

Marrow-derived smooth muscle cells also are more abundant in damaged than undamaged segments of atherosclerotic vessels (Caplice et al. 2003). Yet, parabiosis experiments designed to look for multi-tissue engraftment from circulating precursors observed that significant chimaerism was present in the bone marrow but not in other organs (Wagers et al. 2002).

Is cell fusion responsible for adult stem cell plasticity?

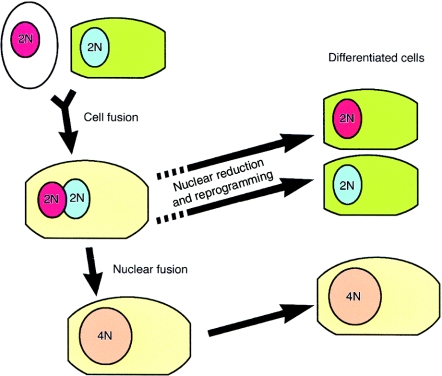

Cell fusion between a marked donor cell and a resident cell could mimic the appearance of adult stem cell plasticity. Through cell fusion, molecules from one fusion partner could reprogramme gene expression in the genome of the other partner. Fusion might occur between a donor cell with stem cell properties and a resident cell or a transdifferentiated cell and a resident cell.

Cell fusion is normal in a limited range of tissues in mammals, for example myotubes, osteoclasts and placenta, although cell fusion is the fate of around one in three cells in Caenorhabditis elegans (Shemer & Podbilewicz 2000). Studies of mammalian cells in vitro have shown that spontaneous cell fusion occurs in cultures of ES cells and neural stem cells, but at low frequency (1 : 1000–1 : 100,000 brains cells or 1 : 100,000–1 : 1,000,000 bone marrow cells) (Terada et al. 2002; Ying et al. 2002). Fusion of MSC with airway epithelial cells has been recorded in time-lapse (Spees et al. 2003), as have rare fusion events during culture of irradiated embryo fibroblast or bladder cells (Forrester et al. 2000) (see also the archives at http://www.ucsf.edu/cvtl/research.html).

The astonishing clusters of wild-type hepatocytes that help normalize the liver of fah null mouse rescued by wild-type bone marrow (Lagasse et al. 2000) appear mostly, if not exclusively, derived from fusion events. Transplantation with as few as 50 sorted HSCs and cycles of selection pressure can rescue the mouse and restore the missing biochemical function of its liver. However, the nodules of therapeutically successful cells are abnormal, expressing genes of both donor and recipient and with cytogenetic evidence indicating a high proportion of fused cells: 80,XXXY (diploid to diploid fusion) and 120,XXXXYY (diploid to tetraploid fusion) (Vassilopoulos et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003). Irregular heterokaryons produced in the liver might subsequently die, shed a nucleus (Figure 2) or proliferate and in mouse liver could be involved in polyploidization that normally results in >80% of hepatocytes being binucleate with nuclei containing substantially more than 2n chromosomes, especially in older mice. An alternative strategy used to create a selective advantage in bone marrow-derived hepatocytes was based on the protective effect of Bcl-2 against Fas-mediated apoptosis to selectively amplify a small number of hepatocytes in vivo, but this study did not look for fusion between donor cells and recipient hepatocytes (Mallet et al. 2002).

Figure 2.

A possible route for tissue-specific stem cells to exhibit stem cell plasticity with lineage transformation via cell fusion. Initially, tissue-specific stem cells or transit-amplifying cells (white cytoplasm) fuse with a terminally differentiated cell of another lineage in specific circumstances. The fusion cell will possess both donor and recipient chromosomes and may be able to express both sets of genes. In the fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase-deficient mouse model, nuclear fusion occurs (Vassilopoulos et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003). The dashed arrows indicate how a heterokaryon or fusion cell might maintain a diploid karyotype, through nuclear reduction.

Cell fusion, as a general mechanism to account for plasticity phenomena, appears to conflict with certain clinical and experimental observations. For example, examination of more than 9700 buccal cells from five female patients who received male bone marrow transplantation 4–6 years previously revealed that they were quite frequently XY cells (0.8–12.7%), with just one XXXY cell (0.01%) and one XXY cell (0.01%) seen (Tran et al. 2003). Similarly, only one X and one Y chromosome was identified in apparently transdifferentiated epidermal, liver and gastric mucosa cells in female patients who received mobilized male peripheral blood HSC (Korbling et al. 2002), and bone marrow-derived smooth muscle cells found in atherosclerotic plaques were XY and not polyploid (Caplice et al. 2003). Cell fusion was also not involved in either remodelling the interior of the renal glomerulus through generation of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) + mesangial cells in male-to-male transplants of HSC (Masuya et al. 2003) or in differentiation of bone marrow-derived cells into pancreatic islet cells expressing markers of β-cell differentiation and insulin secretion in response to glucose (Ianus et al. 2003), even though pancreatic acinar cells seem able to tolerate polyploidy.

Cell fusion followed by nuclear shedding, or deletion (Figure 2), may, however, be required to account for the presence of mononucleate XY Purkinje cells in the brains of female recipients of male bone marrow (Weimann et al. 2003). As these cells have incredibly complex interconnections that seem impossible to be produced de novo in the short interval between grafting and death, these researchers sought evidence for a fusion origin and have recently described the progressive accumulation of heterokaryons with bone marrow-derived nuclei in Purkinje cells in vivo (Weimann et al. 2003). Whether this process is invoked in forming other neural cell types is unknown (Meletis & Frisen 2003). Further support for cell fusion in the generation of bone marrow-derived Purkinje cells and also hepatocytes and cardiomyocytes was presented very recently by Alvarez-Dolado and colleagues (Alvarez-Dolado et al. 2003) who carried out very elegant studies in vivo and in vitro in which a reporter gene was activated only when cells fused, a strategy used also by others (Ianus et al. 2003). Importantly, they considered that after some time either the two nuclei within heterokaryons fused or supernumerary nuclei were eliminated.

In muscle, there is recent evidence for clonal expansion of the progeny of single sorted HSC into muscle cells as well as cells of haematopoietic lineages. Corbel and colleagues (Corbel et al. 2003) found 5% of cells in the thin muscle sheet beneath the skin of mice to be derived from the donor cell and showed that similar results could be obtained in secondary transfer (using bone marrow from the first recipient). Camargo and colleagues (Camargo et al. 2003) also used a single HSC graft and detected haematopoietic progeny and marked muscle cells after damage; importantly, their experimental protocol provided evidence that cell fusion had occurred between circulating myeloid cells and resident muscle cells. Thus, from these studies, it seems that the new muscle cells derive from multiple engraftment events. On the other hand, an earlier study (Labarge & Blau 2002) in which transplantation of GFP + bone marrow resulted in the appearance of GFP + muscle satellite cells (local stem cells), these cells were initially diploid, not fusions, and only later following muscle damage did some of their number fuse appropriately into multinuclear myotubes.

Exogenous cardiac progenitor cells (Sca-1+) are also recently reported to engraft cardiac muscle after ischaemic damage, with fusion and nonfusion pathways appearing equally involved (Oh et al. 2003).

It has been suggested that there may be something exciting about rescuing damaged cells through cell fusion with, for example, bone marrow-derived cells, to provide a healthy and entire genetic complement, perhaps one that has been manipulated for gene therapy (Blau 2002), but low rates of spontaneous fusion and safety concerns may ultimately limit their use (Vassilopoulos & Russell 2003).

If cell fusion occurs naturally and is not a consequence of lethal doses of irradiation and bone marrow transplantation, we have to ask what is the fate of these peculiar fusion cells and their unstable genetic complement? Are they eliminated preferentially or could they be founder cells for neoplastic development?

The therapeutic potential of cell therapies

The possibility that bone marrow grafting could act as a cell therapy for a nonhaematological disease has been tested in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Whole bone marrow transplantation was considered able to improve certain parameters of disease, and cultures from biopsies of recipient bone indicated that donor-derived cells were present. Subsequently, mesenchymal cells expanded in culture from the same donor were administered and some further clinical improvements noted that they were considered due to formation of functional wild-type osteoblasts from the donor MSCs, although gene-marked cells when detectable were <1% of cells in bone cultures (Horwitz et al. 1999a; 1999b; Horwitz et al. 2002). These studies seek to take advantage of the ability of MSCs to migrate through the recipient, home to appropriate sites and only then follow what are normal pathways of differentiation.

Experimental and early clinical studies support the concept that autologous bone marrow infusions are beneficial in ischaemic heart disease (Perin et al. 2003). The benefits appear related to preserving or reestablishing microvessels and limiting the extent and severity of damage (Nishida et al. 2003). Many would argue that these experimental approaches rely simply on dedifferentiation, because endothelial progenitors and haematopoietic stem cells are both present in adult bone marrow and both classes of cell are formed after single-cell HSC transplantation (Grant et al. 2002), and both can be formed from MAPC (Reyes et al. 2002). Endothelial precursors selected using the cell-surface marker AC133 are effective alone (Stamm et al. 2003). In support of broader plasticity, however, is evidence indicating that bone marrow generates new cardiac muscle cells too (Kuramochi et al. 2003). If autologous bone marrow is used, rejection will not be a problem, but what would happen if prospectively prepared cultures were used? Would GVHD develop?

Data from Cornacchia and colleagues (Cornacchia et al. 2001) confirmed that glomerular mesangial cell progenitors are derived from the bone marrow, but their study was the first to show that bone marrow transplantation can deliver a disease phenotype to normal glomeruli. Glomerular lesions may therefore be perpetuated or aggravated, rather than resolved, by newly arriving progenitor cells bearing a disease genotype, and this may act to erode the benefits of a renal allograft. The fact that no engraftment of podocytes was detected in this study is disappointing, as podocyte dysfunction appears central to many causes of renal failure (Koop et al. 2003) and may be particularly susceptible to immune attack (Mathieson 2003).

Are the risks of rejection significant or predictable?

Cellular therapies for immunologically mature patients, whether based on embryonic or adult stem cell cultures, would be susceptible to GVHD, unless the cells were derived from the patient themselves. Some groups feel that organ transplantation is more likely to be tolerated if a degree of haematopoietic chimaerism with donor HSC is induced.

Personal ES cultures are theoretically possible, using a somatic cell nucleus and an enucleated donor oocyte. The cells would be genetic chimaeras with all proteins encoded by mitochondrial DNA being derived exclusively from the donor oocyte (Evans et al. 1999), although this has not been problematic for cloned mammals. Theoretically, donor HSC could be produced from the cell lines used to manufacture the specific cell therapy. Yet, the need for HSC to cograft is not clear; in a recent series using an immunosuppression regime designed to facilitate tolerance mechanisms, donor bone marrow infusion did not confer an advantage and it was considered that the timing and dosage of immunosuppression might be more important than donor cell dose in determining the outcome (Starzl et al. 2003).

Are long-term therapeutic benefits possible from engrafted cells, whether from cultures or produced via stem cell plasticity or transdifferentiation in vivo? There are reasons to be concerned that exposure to a new protein accessible to immune surveillance will be followed by its recognition as nonself and destruction of the expressing cells. In fact, one strategy used to generate an immune response in mice to a highly conserved protein is to knock out the mouse gene, allowing the immunizing peptide to generate a response that can be exploited to generate monoclonal antibodies (Castrop et al. 1995). Therapeutic cells bearing the marker gene neoR are rendered vulnerable to immune attack (Horwitz et al. 2002). Another recent example is found in some patients with congenital nephrotic syndrome of Finnish type affecting the protein nephrin, crucial for maintaining function of filtration slits in glomeruli. Individuals without nephrin (Fin-major/Fin-major) suffer from progressive renal failure that responds to renal allografting but can recur in the graft when the recipient mounts an immune response to nephrin itself (Patrakka et al. 2002).

Such specific responses may render any cell therapy ineffective; yet, if the cells or even the specific therapeutic protein could be made available at a preimmune stage, a second exposure may be tolerated with no requirement for immunosuppression, either before or after the transplantation (Crombleholme et al. 1991; Ek et al. 1994). Transfer of MSC (Liechty et al. 2000) into foetal sheep has exploited this window of opportunity, which may last longer than expected, and results in the presence of several appropriately located human cell types including chondrocytes, adipocytes and cardiomyocytes. Zanjani and colleagues have detected human hepatocytes in the livers of sheep that were grafted with human neuronal stem, cord blood or bone marrow cells in utero[reported by van Bekkum (Van Bekkum 2001)].

Cells can be subjected to genetic manipulation in vitro then used to produce viable animals by nuclear transfer that express and tolerate a transgenic protein (Schnieke et al. 1997); and even direct injection of retroviral vectors into preimmune sheep induces cellular and humoural tolerance to the vector/transgene products; hence, even relatively low levels of gene transfer in utero may render the recipient tolerant to the exogenous gene and thus potentially permit the successful postnatal treatment of the recipient (Tran et al. 2001). Yet, early exposure does not seem to offer the complete answer, transplacental exchange of cells during pregnancy can generate chimaerism of maternal tissue and may contribute to postpartum exacerbation of thyroiditis. Srivatsa and colleagues (Srivatsa et al. 2001) reported that male cells (between 1 and 165 per tissue section) were seen individually or in clusters in a variety of thyroid diseases and not restricted to inflammatory thyroid diseases, suggesting that immunological tolerance does not always occur. The same group found that maternal cell engraftment of foetal tissues can also occur (Srivatsa et al. 2003), and others have described female chimaerism of blood in males with no indication of twinning or of blood transfusion (Maloney et al. 1999). Hence, we may all be chimaeras, and this raises once again concerns that the identification of male cells in female recipients of bone marrow, for example, does not establish their heritage (Alison et al. 2000; Kleeberger et al. 2002).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital, Taiwan, and Cancer Research UK for funding and to our colleagues for support.

References

- Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, et al. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J. Immunol. 2001;166:7556–7562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Awqati Q, Oliver JA. Stem cells in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2002;61:387–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alison MR, Poulsom R, Jeffery R, et al. Hepatocytes from non-hepatic adult stem cells. Nature. 2000;406:257. doi: 10.1038/35018642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425:968–973. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askari AT, Unzek S, Popovic ZB, et al. Effect of stromal-cell-derived factor 1 on stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2003;362:697–703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck F, Chawengsaksophak K, Luckett J, et al. A study of regional gut endoderm potency by analysis of Cdx2 null mutant chimaeric mice. Dev. Biol. 2003;255:399–406. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson C, Rietze R, Reynolds B, et al. Turning brain into blood: a hematopoietic fate adopted by neural stem cells in vivo. Science. 1999;283:534–537. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau HM. A twist of fate. Nature. 2002;419:437. doi: 10.1038/419437a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun KM, Niemann C, Jensen UB, et al. Manipulation of stem cell proliferation and lineage commitment: visualisation of label-retaining cells in wholemounts of mouse epidermis. Development. 2003;130:5241–5255. doi: 10.1242/dev.00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittan M, Hunt T, Jefferey R, et al. Bone marrow derivation of pericryptal myofibroblasts in the mouse and human small intestine and colon. Gut. 2002;50:752–757. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.6.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittan M, Wright NA. Gastrointestinal stem cells. J. Pathol. 2002;197:492–509. doi: 10.1002/path.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, et al. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol. Med. 1994;1:71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo FD, Green R, Capetenaki Y, et al. Single hematopoietic stem cells generate skeletal muscle through myeloid intermediates. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1520–1527. doi: 10.1038/nm963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KH, McWhir J, Ritchie WA, Wilmut I. Sheep cloned by nuclear transfer from a cultured cell line. Nature. 1996;380:64–66. doi: 10.1038/380064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplice NM, Bunch TJ, Stalboerger PG, et al. Smooth muscle cells in human coronary atherosclerosis can originate from cells administered at marrow transplantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:4754–4759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730743100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrop J, Verbeek S, Hofhuis F, Clevers H. Circumvention of tolerance for the nuclear T cell protein TCF-1 by immunization of TCF-1 knock-out mice. Immunobiology. 1995;193:281–287. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D, Johansson C, WilbertZ J, et al. Generalized potential of adult neural stem cells. Science. 2000;288:1660–1663. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5471.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbel SY, Lee A, Yi L, et al. Contribution of hematopoietic stem cells to skeletal muscle. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1528–1532. doi: 10.1038/nm959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornacchia F, Fornoni A, Plati AR, et al. Glomerulosclerosis is transmitted by bone marrow-derived mesangial cell progenitors. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1649–1656. doi: 10.1172/JCI12916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombleholme TM, Langer JC, Harrison MR, Zanjani ED. Transplantation of fetal cells. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991;164:218–230. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90656-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio-Tsonis K, Tsonis PA. Eye regeneration at the molecular age. Dev. Dyn. 2003;226:211–224. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Direkze NC, Forbes SJ, Brittan M, et al. Multiple organ engraftment by bone-marrow-derived myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in bone-marrow-transplanted mice. Stem. Cells. 2003;21:514–520. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-5-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Down JD, White-Scharf ME. Reprogramming immune responses: enabling cellular therapies and regenerative medicine. Stem. Cells. 2003;21:21–32. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek S, Ringden O, Markling L, Westgren M. Immunological capacity of human fetal liver cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;14:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, Gurer C, Loike JD, et al. Mitochondrial DNA genotypes in nuclear transfer-derived cloned sheep. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:90–93. doi: 10.1038/12696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester HB, Albright N, Ling CC, Dewey WC. Computerized video time-lapse analysis of apoptosis of REC: Myc cells X-irradiated in different phases of the cell cycle. Radiat. Res. 2000;154:625–639. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)154[0625:cvtlao]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenstein A, Ivanov-Smolenski A, Chajlakjan R, et al. Origin of bone marrow stromal mechanocytes in radiochimeras and heterotopic transplants. Exp. Hematol. 1978;6:440–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisen J. Stem cell plasticity? Neuron. 2002;35:415–418. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MB, May WS, Caballero S, et al. Adult hematopoietic stem cells provide functional hemangioblast activity during retinal neovascularization. Nat. Med. 2002;8:607–612. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm PC, Nickerson P, Jeffery J, et al. Neointimal and tubulointerstitial infiltration by recipient mesenchymal cells in chronic renal-allograft rejection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:93–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Verfaillie C, Chmielewski D, et al. A role for extrarenal cells in the regeneration following acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002a;62:1285–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Verfaillie C, Chmielewski D, et al. Erratum: a role for extrarenal cells in the regeneration following acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002b;62:2311–2314. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch HM, Zheng D, Jorgensen ML, Petersen BE. SDF-1alpha/CXCR4: a mechanism for hepatic oval cell activation and bone marrow stem cell recruitment to the injured liver of rats. Cloning Stem Cells. 2002;4:339–351. doi: 10.1089/153623002321025014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EM, Gordon PL, Koo WK, et al. Isolated allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells engraft and stimulate growth in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: implications for cell therapy of bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:8932–8937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132252399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz E, Prockop D, Fitzpatrick L, et al. Osteogeneis imperfecta calls for caution. Nat. Med. 1999a;5:466–467. doi: 10.1038/8528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz E, Prockop D, Fitzpatrick L, et al. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat. Med. 1999b;5:309–313. doi: 10.1038/6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianus A, Holz GG, Theise ND, Hussain MA. In vivo derivation of glucose-competent pancreatic endocrine cells from bone marrow without evidence of cell fusion. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:843–850. doi: 10.1172/JCI16502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issarachai S, Priestley GV, Nakamoto B, Papayannopoulou T. Cells with hemopoietic potential residing in muscle are itinerant bone marrow-derived cells. Exp. Hematol. 2002;30:366–373. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00773-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K, Mi T, Goodell M. Hematopoietic potential of stem cells isolated from murine skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14482–14486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai T, Spradling A. An empty Drosophila stem cell niche reactivates the proliferation of ectopic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:4633–4638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830856100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale S, Karihaloo A, Clark PR, et al. Bone marrow stem cells contribute to repair of the ischemically injured renal tubule. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:42–49. doi: 10.1172/JCI17856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada H, Ogawa M. Bone marrow origin of hematopoietic progenitors and stem cells in murine muscle. Blood. 2001;98:2008–2013. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleeberger W, Rothamel T, Glockner S, et al. High frequency of epithelial chimerism in liver transplants demonstrated by microdissection and STR-analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35:110–116. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleeberger W, Versmold A, Rothamel T, et al. Increased chimerism of bronchial and alveolar epithelium in human lung allografts undergoing chronic injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2003;162:1487–1494. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64281-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koop K, Eikmans M, Baelde HJ, et al. Expression of podocyte-associated molecules in acquired human kidney diseases. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14:2063–2071. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000078803.53165.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbling M, Estrov Z. Adult stem cells for tissue repair – a new therapeutic concept? N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:570–582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbling M, Katz RL, Khanna A, et al. Hepatocytes and epithelial cells of donor origin in recipients of peripheral-blood stem cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa3461002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause D, Theise N, Collector M, et al. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi Y, Fukazawa R, Migita M, et al. Cardiomyocyte regeneration from circulating bone marrow cells in mice. Pediatr. Res. 2003;54:319–325. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000078275.14079.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarge MA, Blau HM. Biological progression from adult bone marrow to mononucleate muscle stem cell to multinucleate muscle fiber in response to injury. Cell. 2002;111:589–601. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladurner P, Rieger R, Baguña J. Spatial distribution and differentiation potential of stem cells in hatchlings and adults in the marine platyhelminth Macrostomum sp.: a bromodeoxyuridine analysis. Dev. Biol. 2000;226:231–241. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagasse E, Connors H, Al-Dhalimy M, et al. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. Nat. Med. 2000;6:1229–1234. doi: 10.1038/81326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lako M, Armstrong L, Cairns PM, et al. Hair follicle dermal cells repopulate the mouse haematopoietic system. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:3967–3974. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemischka IR, Raulet DH, Mulligan RC. Developmental potential and dynamic behavior of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 1986;45:917–927. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechty K, MacKenzie T, Shaaban A, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells engraft and demonstrate site-specific differentiation after in utero transplantation in sheep. Nat. Med. 2000;6:1282–1286. doi: 10.1038/81395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F, Cordes K, Li L, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells contribute to the regeneration of renal tubules after renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14:1188–1199. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000061595.28546.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet VO, Mitchell C, Mezey E, et al. Bone marrow transplantation in mice leads to a minor population of hepatocytes that can be selectively amplified in vivo. Hepatology. 2002;35:799–804. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney S, Smith A, Furst D, et al. Microchimerism of maternal origin persists into adult life. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:41–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuya M, Drake CJ, Fleming PA, et al. Hematopoietic origin of glomerular mesangial cells. Blood. 2003;101:2215–2218. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson PW. What has the immune system got against the glomerular podocyte? Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2003;134:1–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maves L, Schubiger G. Cell determination and transdetermination in Drosophila imaginal discs. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 1999;43:115–151. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney-Freeman SL, Jackson KA, Camargo FD, et al. Muscle-derived hematopoietic stem cells are hematopoietic in origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1341–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032438799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meletis K, Frisen J. Blood on the tracks: a simple twist of fate? Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:292–296. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P, Pfeiffer P, Koglin J, et al. Cardiomyocytes of noncardiac origin in myocardial biopsies of human transplanted hearts. Circulation. 2002;106:31–35. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000022405.68464.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M, Li TS, Hirata K, et al. Improvement of cardiac function by bone marrow cell implantation in a rat hypoperfusion heart model. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003;75:768–773. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04388-6. 773 764 (discussion) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura EK, Jordan SA, Oshima H, et al. Dominant role of the niche in melanocyte stem-cell fate determination. Nature. 2002;416:854–860. doi: 10.1038/416854a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye HL, Cameron JA, Chernoff EA, Stocum DL. Regeneration of the urodele limb: a review. Dev. Dyn. 2003;226:280–294. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Bradfute SB, Gallardo TD, et al. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:12313–12318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132126100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima H, Rochat A, Kedzia C, et al. Morphogenesis and renewal of hair follicles from adult multipotent stem cells. Cell. 2001;104:233–245. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patapoutian A, Wold BJ, Wagner RA. Evidence for developmentally programmed transdifferentiation in mouse esophageal muscle. Science. 1995;270:1818–1821. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrakka J, Ruotsalainen V, Reponen P, et al. Recurrence of nephrotic syndrome in kidney grafts of patients with congenital nephrotic syndrome of the Finnish type: role of nephrin. Transplantation. 2002;73:394–403. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200202150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perin EC, Dohmann HF, Borojevic R, et al. Transendocardial, autologous bone marrow cell transplantation for severe, chronic ischemic heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:2294–2302. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070596.30552.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsom R, Alison MR, Forbes SJ, Wright NA. Adult stem cell plasticity. J. Pathol. 2002;197:441–456. doi: 10.1002/path.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsom R, Forbes SJ, Hodivala-Dilke K, et al. Bone marrow contributes to renal parenchymal turnover and regeneration. J. Pathol. 2001;195:229–235. doi: 10.1002/path.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ, Gregory CA, Spees JL. One strategy for cell and gene therapy: harnessing the power of adult stem cells to repair tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11917–11923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834138100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes M, Dudek A, Jahagirdar B, et al. Origin of endothelial progenitors in human postnatal bone marrow. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:337–346. doi: 10.1172/JCI14327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhind SM, Taylor JE, De Sousa PA, et al. Human cloning: can it be made safe? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003;4:855–864. doi: 10.1038/nrg1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnieke AE, Kind AJ, Ritchie WA, et al. Human factor IX transgenic sheep produced by transfer of nuclei from transfected fetal fibroblasts. Science. 1997;278:2130–2133. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemer G, Podbilewicz B. Fusomorphogenesis: cell fusion in organ formation. Dev. Dyn. 2000;218:30–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200005)218:1<30::AID-DVDY4>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen CN, Horb ME, Slack JM, Tosh D. Transdifferentiation of pancreas to liver. Mech. Dev. 2003;120:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg DG, Sullivan J, Kang E, et al. Cdx2 ectopic expression induces gastric intestinal metaplasia in transgenic mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:689–696. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack JM. Homoeotic transformations in man: implications for the mechanism of embryonic development and for the organization of epithelia. J. Theor. Biol. 1985;114:463–490. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(85)80179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack JM, Tosh D. Transdifferentiation and metaplasia – switching cell types. Curr. Opin. Genet.Dev. 2001;11:581–586. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spees JL, Olson SD, Ylostalo J, et al. Differentiation, cell fusion, and nuclear fusion during ex vivo repair of epithelium by human adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2397–2402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437997100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivatsa B, Srivatsa S, Johnson KL, et al. Microchimerism of presumed fetal origin in thyroid specimens from women: a case-control study. Lancet. 2001;358:2034–2038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivatsa B, Srivatsa S, Johnson KL, Bianchi DW. Maternal cell microchimerism in newborn tissues. J. Pediatr. 2003;142:31–35. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.mpd0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamm C, Westphal B, Kleine HD, et al. Autologous bone-marrow stem-cell transplantation for myocardial regeneration. Lancet. 2003;361:45–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starzl TE, Murase N, Abu-Elmagd K, et al. Tolerogenic immunosuppression for organ transplantation. Lancet. 2003;361:1502–1510. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13175-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada N, Hamazaki T, Oka M, et al. Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature. 2002;416:542–545. doi: 10.1038/nature730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theise N, Badve S, Saxena R, et al. Derivation of hepatocytes from bone marrow cells in mice after radiation-induced myeloablation. Hepatology. 2000;31:234–240. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran ND, Porada CD, Almeida-Porada G, et al. Induction of stable prenatal tolerance to beta-galactosidase by in utero gene transfer into preimmune sheep fetuses. Blood. 2001;97:3417–3423. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran SD, Pillemer SR, Dutra A, et al. Differentiation of human bone marrow-derived cells into buccal epithelial cells in vivo: a molecular analytical study. Lancet. 2003;361:1084–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12894-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsonis PA. Regeneration in vertebrates. Dev.Biol. 2000;221:273–284. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bekkum DW. New stem cell workshop. Stem Cells. 2001;19:260–262. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-3-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilopoulos G, Russell DW. Cell fusion: an alternative to stem cell plasticity and its therapeutic implications. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003;13:480–485. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilopoulos G, Wang PR, Russell DW. Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature. 2003;422:901–904. doi: 10.1038/nature01539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagers AJ, Sherwood RI, Christensen JL, Weissman IL. Little evidence for developmental plasticity of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2002;297:2256–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1074807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Montini E, Al-Dhalimy M, et al. Kinetics of liver repopulation after bone marrow transplantation. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;161:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64212-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, et al. Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;422:897–901. doi: 10.1038/nature01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimann JM, Charlton CA, Brazelton TR, et al. Contribution of transplanted bone marrow cells to Purkinje neurons in human adult brains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2088–2093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337659100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimann JM, Johansson CB, Trejo A, Blau HM. Stable reprogrammed heterokaryons form spontaneously in Purkinje neurons after bone marrow transplant. Nat.Cell Biol. 2003;5:959–966. doi: 10.1038/ncb1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G, Alvarez C. Host repopulation of the endothelium in allografts of kidneys and aorta. Surg. Forum. 1969;20:293–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmut I, Paterson L. Somatic cell nuclear transfer. Oncol. Res. 2003;13:303–307. doi: 10.3727/096504003108748492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying QL, Nichols J, Evans EP, Smith AG. Changing potency by spontaneous fusion. Nature. 2002;416:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]