Abstract

Sepsis in patients receiving chemotherapy may result in acute respiratory distress syndrome, despite decreased number of blood neutrophils [polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs)]. In the present study, we investigated the correlation of cyclophosphamide (CY)-induced neutropenia with the destructive potential of lung PMN in respect to formation of septic acute lung injury (ALI). Mice were treated with 250 mg/kg of CY or saline (control) and subjected to cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) or sham operation. ALI was verified by histological examination. Lung PMNs and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) were assessed by flow cytometry and gelatin zymography. CLP in CY-treated mice induced a typical lung injury. Despite profound neutropenia, CY treatment did not attenuate CLP-induced ALI. This might relate to only a partial suppression of PMN: CY has significantly reduced PMN influx into the lungs (P = 0.008) and suppressed their oxidative metabolism, but had no suppressive effect on degranulation (P = 0.227) and even induced MMP-9 activity (P = 0.0003). In CY-untreated animals, peak of CLP-induced ALI coincided with massive PMN influx (P = 0.013), their maximal degranulation (P = 0.014) and activation of lung MMP-9 (P = 0.002). These findings may indicate an important role of the residual lung PMN and activation of MMP-9 in septic lung injury during CY chemotherapy.

Keywords: ARDS, chemotherapy, flow cytometry, immunosuppression, leucocyte-mediated tissue damage, neutropenia

Cyclophosphamide (CY) is an immunosuppressive alkylating agent used for the treatment of a broad spectrum of malignancies. Similar to other immunosuppressive drugs, CY produces a neutropenia in a dose-related fashion (Bosch et al. 2002; Montillo et al. 2003). The reduced count of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) predisposes the host to severe infections, leading to multiple organ dysfunction and failure. Sepsis and sepsis-induced multiple organ failure (MOF) in the immunocompromized patient result in a high rate of mortality and morbidity that has not been significantly influenced by modern therapeutic modalities (Kiehl et al. 1998).

Most frequently, sepsis-associated MOF is manifested by acute lung injury (ALI), which may progress to full-blown acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and involve in damage to other organs (Sachdeva & Guntupalli 1997). Several experimental and clinical investigations have presented evidence implicating PMN in the pathogenesis of ALI. PMN and PMN activation products, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proteolytic enzymes, are abundantly present in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of patients with ARDS as well as in samples obtained from experimental animals with ALI (Lee et al. 1981; Rinaldo & Rogers 1982; Baird et al. 1986; Oldham & Bowen 1998; Metnitz et al. 1999; Haslett et al. 2000). Increased levels of several matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) directly involved in degradation of the extracellular matrix have also been found in BALF during sepsis and ARDS in both experimental and clinical investigations (Ricou et al. 1996; Ferry et al. 1997; Corbel et al. 2000). Although various lung cells may express MMPs, under inflammatory conditions, the MMPs are mainly produced by PMN and macrophages (Corbel et al. 2000). Eventually, it has been shown that manipulations with PMN blood count may influence the extent of septic lung damage (Windsor et al. 1993; Azoulay et al. 2002).

Despite the extensive documentation of the association between PMN and ALI, several clinical and experimental studies have shown that ALI and ARDS can develop in the immunocompromised host, when the number of PMN in peripheral blood is very low (Ognibene et al. 1986; Wickel et al. 1997; Kiehl et al. 1998). Currently, it is not clear which factors play a role in the development of septic ALI in the neutropenic host. In the present study, septic lung injury was induced by the surgical intervention during CY chemotherapy and the related neutropenia. We hypothesized that CY does not reduce PMN count uniformly in blood and in lungs, and the suppression of PMN functions is not proportional to the decrease in cell number. The study was aimed to investigate to what extent CY-induced neutropenia corresponds to the destructive potential of lung PMN and to test how this kind of neutropenia may affect lung injury during experimental sepsis.

Materials and methods

Animals

Sepsis was induced in adult male C57BL/6 mice (Harlan Laboratories Ltd, Jerusalem, Israel) weighing 25–30 g by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), as described by Wichterman et al. (1980). Animal care and all experiments were performed in accordance with the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Technion.

Experimental procedures

Animals were made to fast overnight before experiments but given water ad libitum. The animals were anaesthetized by intramuscular injection of 1.5 mg/kg of dehydro-benzperidol (Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium) and 24 mg/kg of ketamine (Parke-Davis, Pontypool, Gwent, UK). Following anaesthesia, animals were divided randomly into two groups. In group 1 (n = 41), a midline laparotomy was performed, and the caecum was exposed, ligated distal to the ileocecal valve to avoid intestinal blockade, punctured once with 21G needle and then returned into abdomen. The abdominal incision was then closed in layers. Each animal was resuscitated with 2 ml/100 g of warmed normal saline subcutaneously. Mortality within 7 days was 31.7% (13 of 41 mice). In group 2 (n = 28), mice underwent the same operation except for the caecum ligation and puncture (sham operation). No mortality was detected in this group. After full recovery, mice were transferred into their cages and observed for 7 days. Four animals from each group were killed daily (1–7 days after CLP) by overdose of the anaesthetic solution, and lungs were excised for histological examination. Lungs of four healthy animals were examined as a reference.

In separate series of experiments, sepsis was induced by CLP in mice treated by a single intraperitoneal injection of 250 mg/kg of CY (Sigma-Aldrich Israel Ltd, Rehovot, Israel) similar to a high-dose regimen for treatment of solid tumours (Carter & Livingston 1975). The cytotoxic effect of CY was monitored by peripheral blood PMN count. Total of four groups were studied, including control animals treated by normal saline, CY treatment alone, CY treatment followed by sham operation (n = 8 in the first three groups) and CY treatment followed by CLP (n = 17). After 24 h of the injection, randomly selected mice were subjected to sham operation or CLP. The animals were killed after 24 h, and lungs were excised for further examination.

Lung histology

Lungs were immersion fixed with phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Sigma-Aldrich Israel Ltd), dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Series of 5-µm sections, stained with haematoxylin and eosin, were examined in a blind fashion. A scoring system to grade the degree of lung injury was employed, which is based on the following histologic features: hyperaemia and blood congestion, oedema, neutrophil margination and tissue infiltration, intra-alveolar haemorrhage and debris and cellular hyperplasia (Bachofen & Weibel 1982). Each feature was graded as absent, mild, moderate or severe with a score of 0–3, respectively. A total score was calculated for each animal and the mean scores and SE for each group.

Lung PMN isolation

Lung cells were isolated and separated as described by Holt et al. (1985). Briefly, lungs of animals from the various experimental groups (n = 6/group) killed on days 1, 4 and 7 after the operations were thoroughly rinsed via a right atrium with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 1% fetal calf serum (FCS), excised, gently disrupted by teasing and resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 250 U/ml of collagenase, 50 U/ml of DNAse and 10% FCS (all from Sigma-Aldrich Israel Ltd). Lungs were then enzymatically digested for 2 h at 37 °C. Tissue fragments and the majority of dead cells were removed by filtration through a nylon 20 mesh and viable cells (up to 90% by Trypan Blue exclusion test) were collected by centrifugation, counted and processed for further analysis. Mononuclear cells and granulocytes were separated on the appropriate Histopack-1.083 (Sigma-Aldrich Israel Ltd) and Percoll 1.110 gradients (Pharmacia, Fine Chemicals AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Purity of separated populations was 89–94% according to microscopy of Giemsa-stained cell smears, and cell viability was more than 90% in all preparations.

Flow cytometry

Monoclonal antibodies recognizing mouse CD11b and Ly-6G antigens (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) were used to detect PMN. About 106 cells were incubated with 0.5 µg of monoclonal antibodies for 20 min at 4 °C, washed and analysed by FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, NJ, USA) using control of autofluorescence and relative isotypic controls. Double-positive fluorescent cells with the high mean fluorescence intensity for Ly6G (CD11b+Ly6Ghigh) were recognized as PMN (Lagasse & Weissman 1996). PMN count was calculated by multiplying of PMN percentage by total cell count in each cell preparation and expressed as 106 PMN recovered from one whole lung.

Apoptosis

PMN apoptosis in isolated lung cell populations was assessed by a triple staining with Cy-5-labelled Annexin V, FITC-labelled anti-CD11b and R-phycoerythrin-labelled anti-Ly-6G monoclonal antibodies according to the kit manufacturer instruction (Medical and Biological Laboratories, MBL Co. Ltd, Nagoya, Japan). The apoptosis rate was expressed as percentage of Annexin V-positive CD11b+Ly6Ghigh cells. For each analysis, 20,000 events were collected.

Production and release of ROS

ROS production was determined as described previously (Hirsh et al. 2001). Briefly, lung PMNs (1 × 105/0.8 ml) were activated by 200 ng of phorbol-myristate acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich Israel Ltd) or left alone to evaluate the basic (spontaneous) production of ROS. Cells were loaded with 2 µg of dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR, Sigma-Aldrich Israel Ltd) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. At the end of the incubation, cells were pelleted, washed and examined in flow cytometer for determination of intracellular ROS level (ROS production). Cells with no DHR added served as control. All measurements were carried out in duplicates, and results were expressed as a ratio to control.

Aliquots of 0.3 ml of the cell-free supernatant were used for measurement of extracellular ROS level (ROS release) using fluorescence spectrometer LS-5B (PerkinElmer Instruments, Norwalk, CT, USA) at 488 nm excitation and 530 nm emission. Pure PBS served as a blank, and cell supernatant with no DHR added served as control. All measurements were carried out in duplicates, and results were expressed as a ratio to control.

MPO activity measurement

Release of PMN azurophilic granules was determined by myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity measurement in the PMN supernatant. Aliquots of 0.05 ml were placed in a 96-well plate in duplicates, mixed with 0.15 ml TMB liquid substrate system (Sigma-Aldrich Israel Ltd) and immediately examined kinetically in Ceres UV900 ELISA reader at 650 nm. MPO activity was calculated as velocity of the optical density raise, normalized for the reaction volume (ΔA650/ml × min) (Suzuki et al. 1983).

Gelatin zymography of metalloproteinases

MMP activity was determined as described previously (Gepstein et al. 2002). Briefly, small lung specimens were homogenized by using Polytron Pt (Kinematic AC, Basel, Switzerland). Homogenates containing 1 µg of total protein per 10 µl sample buffer were subjected to 10% polyacrylamide gel containing 1 mg/ml type A gelatin from porcine skin (all reagents from Sigma-Aldrich Israel Ltd). Following electrophoresis at 20 mA on ice, gels were washed with 2.5% Triton in TBS buffer to allow protein to renaturate. Following incubation for 40 h at 37 °C in substrate buffer, gels were stained with Coomassie R 250 for 30 min. Gelatin-degrading enzymes were visualized as clear bands, indicating proteolysis of the substrate protein. Gels were analysed by Vilber Lourmat imaging system (Lion, France), and MMP activity was expressed as percentage of healthy control. Human MMP-2 (Chemicon International Ltd, Hofheim, Germany) and MMP-9 (Oncogen Research Products, Boston, MA, USA) were used as zymography standards.

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparison of the differences between groups (independent variables) was performed with one-way anova followed by Student Neuman–Keuls post hoc test (histological scores, PMN counts and functions and densitometry data). A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In vivo CY toxicity

The cytotoxic effect of CY was monitored by peripheral blood PMN counts (Table 1). It has been shown that PMN count decreases 12 h after CY administration, reaches its minimum after 24 h and stays at this level for 5 days after CY injection.

Table 1.

Polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) counts in peripheral blood of cyclophosphamide (CY)-treated mice (n = 8)

| Post-injection days | PMN counts (×106/ml) (mean ± SE)* | P |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (control) | 11.67 ± 0.87 | |

| 12 h | 6.33 ± 0.46 | 0.0056† |

| 1 | 1.63 ± 0.38 | 0.00044† |

| 2 | 2.03 ± 0.29 | 0.00046† |

| 3 | 1.97 ± 0.18 | 0.00039† |

| 4 | 2.13 ± 0.29 | 0.00048† |

| 5 | 2.83 ± 0.49 | 0.00082† |

| 6 | 4.03 ± 0.54 | 0.0073‡ |

| 7 | 4.83 ± 0.33 | 0.0044‡ |

Ten microlitres of blood was daily accepted from a tip of tail and diluted 1 : 20 with 2% acetic acid, and WBCs were counted in a haemocytometre. From another 10 µl, blood smears were prepared, stained with Giemsa's stain and percentage of PMN was determined by cytological examination. PMN counts were calculated as described in Material and methods.

Compared with control.

Compared with day 1.

Mortality rate within the first 24 h after CLP in CY-pretreated animals was 52.9% (nine of 17 mice), while no mortality was in other groups. Preliminary experiments have shown that during the first 36–48 h mortality rates reach 100% of CY-treated mice subjected to CLP (data not shown). Hence, we had to limit the follow-up period in this part of experiments with 1 day after CLP.

Lung histology

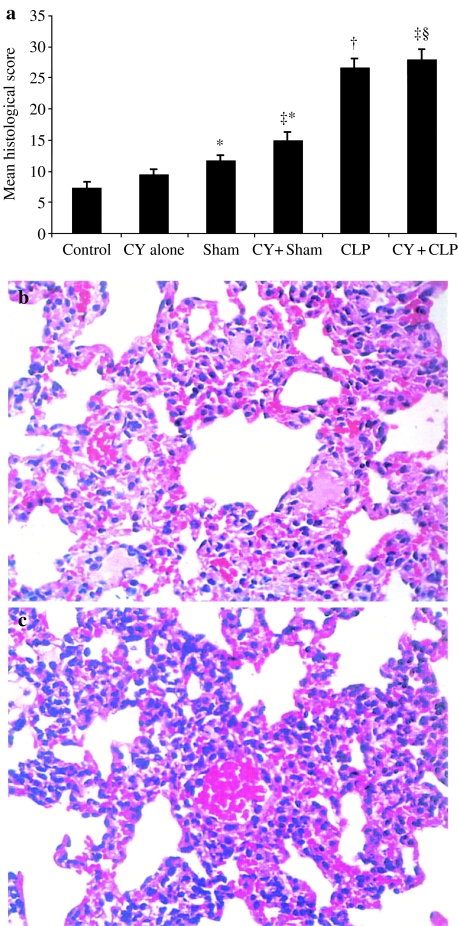

Dynamics of morphological features of the septic ALI is summarized in Table 2. One day after CLP, focal circulatory disorders and atelectasis were observed in lungs. Major hyperaemia was a common finding, and blood congestion was detected in several blood vessels. Blood capillary bed was occupied by erythrocytes. Thickening of alveolar septae was observed, but alveolar spaces were mainly free of fluid, debris or inflammatory cells. On days 2 and 3 after CLP, histological changes have increased due to a combination of circulatory disorders (hyperaemia, blood congestion and oedema) with a prominent interstitial reaction and have reached the peak by day 4 (41.8 ± 2.9 vs. 26.6 ± 1.5 scores at day 1, P = 0.0014). Proliferation of interstitial cells, as well as numerous PMNs and MNCs, was observed within thickened alveolar septae. Fluid, debris and scattered inflammatory cells appeared within several alveolar spaces. No significant change in lung histopathology was observed during the next 2 days. On day 7, hyperaemia and oedema were reduced, but alveolar septae were widened due to a plentiful infiltration with PMN and MNC and interstitial cell proliferation. Alveolar spaces contained some debris and inflammatory cells, and in several alveolar spaces, a solid hyaline-like matter was detected. As the most prominent changes in lung histology were observed on days 1, 4 and 7 after CLP, these days were chosen for lung PMN isolation and functional analysis. The treatment with CY induced only mild focal hyperaemia, which did not increase histological scores compared with control animals (Figure 1a). Sham operation in CY-treated animals enhanced focal hyperaemia and resulted in collapse of several alveoli with no evidence of interstitial inflammatory reaction (14.8 ± 1.5 scores, P = 0.021 vs. CY-treated animals). Diffuse hyperaemia and multiple alveoli collapse as well as moderate, mainly MNC infiltration of alveolar septae were detected following CLP in CY-treated animals (27.8 ± 1.8 scores, p = 0.00013) (Figure 1a). No histological evidence of an attenuated lung injury was observed in CY-treated neutropenic mice subjected to CLP compared with untreated animals subjected to CLP (27.8 ± 1.8 vs. 26.6 ± 1.5 scores in untreated mice, P = 0.54) (Figure 1b, c).

Table 2.

Severity of histological changes in lungs of mice with cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)

| Mean histological score (mean ± SE)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative days | Sham-operated animals | CLP operated animals | P† |

| 0 (control) | 7.2 ± 1.1 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | |

| 1 | 11.6 ± 1.0‡ | 26.6 ± 1.5‡ | 0.000032 |

| 2 | 9.2 ± 0.9 | 34.2 ± 2.6 | 0.000018 |

| 3 | 10.4 ± 0.9‡ | 39.8 ± 2.5 | 0.000004 |

| 4 | 9.6 ± 0.9 | 41.8 ± 2.9§ | 0.000005 |

| 5 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 39.6 ± 3.1 | 0.000008 |

| 6 | 7.0 ± 1.1 | 38.8 ± 2.5 | 0.000002 |

| 7 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 35.6 ± 3.5 | 0.000045 |

Series of 5-µm sections, stained with haematoxylin and eosin, were examined in a blind fashion as described in Material and methods. Four animals were studied every day in each group.

Statistical significance compared with Sham-operated animals.

P < 0.05 compared with control.

P < 0.002 compared with day 1.

Figure 1.

(a)Severity of histological changes in lungs of untreated and cyclophosphamide (CY)-treated animals, 1 day after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Four animals were studied in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. sham; ‡P < 0.05 vs. CY treatment alone; §P < 0.05 vs. CY + sham. Representative microphotographs of lungs of CLP-operated animals treated (b)and untreated (c) with CY. Prominent focal hyperaemia and collapse of several alveoli were equally present in both samples. Inflammatory infiltration of alveolar septae was scant in CY-treated animals as compared with the untreated group [haematoxylin and eosin staining (×400)].

Accumulation of PMN in the lung

One day after CLP, the lung tissue was moderately infiltrated by PMN (CD11b+Ly6Ghigh cells): 5.9 ± 1.1% compared to 3.8 ± 0.4% in sham-operated animals (P = 0.033). The PMN infiltration significantly increased by day 4 after CLP: 17.5 ± 2.2% compared to 10.7 ± 2.1% in the matched sham group (P = 0.014). Absolute amount of PMN fluxed into lungs markedly increased also on day 4: 3.94 ± 0.39 vs. 1.02 ± 0.11 × 106 cells/lung on day 1 (P = 0.0022). The high percentage and absolute count of PMN in the lung tissue was observed also on day 7 (19.9 ± 8.1% and 4.06 ± 0.67 × 106 cells/lung). Six animals were studied on 1, 4 and 7 days in each group.

Treatment with CY diminished PMN count in the lung tissue in 2.4 times compared with control (saline-treated) animals (0.17 ± 0.02 vs. 0.41 ± 0.07 × 106 cells/lung, P = 0.027). Moreover, lung accumulation of PMN following CY treatment and CLP decreased to 0.48 ± 0.03 × 106 cells/lung compared to mice subjected to CLP only (1.02 ± 0.11 × 106 cells/lung, P = 0.0008). Six animals were studied in each group.

Progressive infiltration of lungs with recruited PMN has coincided also with stable decreased rate of PMN apoptosis throughout the entire post-CLP period (P < 0.032 compared with each time-matched sham group). No change in the rate of apoptotic PMN was found after the sham operation. Compared to animals with no CY treatment, the rate of lung PMN apoptosis was significantly increased after CY treatment alone (42.4 ± 1.7 vs. 29.2 ± 2.6%, P = 0.0033), as well as after CY treatment followed by sham (35.9 ± 1.9 vs. 26.2 ± 2.8%, P = 0.023) or CLP operation (25.4 ± 1.9 vs. 14.7 ± 2.1%, P = 0.0052). Six animals were studied in all compared group.

ROS production and release

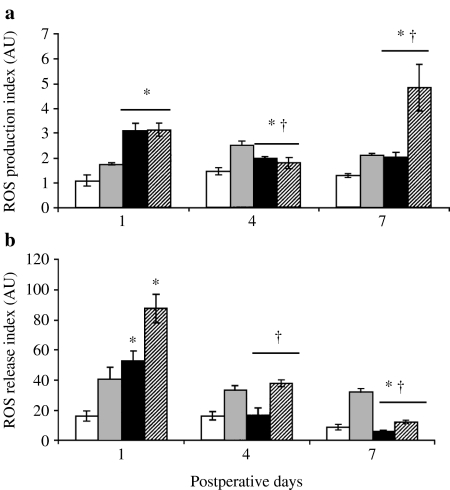

Production of ROS in lung-isolated PMN (n = 6/group) is presented in Figure 2a. Spontaneous ROS production in PMN was highest on day 1 (3.1 ± 0.2 vs. 2.0 ± 0.1 AU on day 4, P = 0.0045). The significant increase was obtained as compared to all time-matched sham groups. Stimulation with PMA did not change the level of intracellular ROS in PMN on day 1 and 4 after CLP but increased it on day 7 as well as in all matched sham groups.

Figure 2.

Spontaneous and stimulated oxidative response of lung polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) to experimental sepsis. Cells isolated from cecal ligation and puncture-operated animals were assessed in the absence (black bars) or presence of phorbol-myristate acetate (PMA) (dashed bars). Unstimulated (white bars) and PMA-treated (grey bars) PMN isolated from sham-operated mice served as a control. ROS production (a) and ROS release (b) were determined on days 1, 4 and 7 after surgery as described in Materials and methods. Six animals were studied every day in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. sham; †P < 0.05 vs. day 1.

Release of ROS from lung-isolated PMN (n = 6/group) is presented in Figure 2b. Spontaneous ROS release from PMN was also highest on day 1 (52.8 ± 6.6 vs. 16.3 ± 4.9 AU on day 4, P = 0.009). The significant increase was obtained and also compared to the time-matched sham group on day 1. Stimulation with PMA significantly increased the level of extracellular ROS at all studied periods after CLP; it was maximal on day 1 and decreased by day 7.

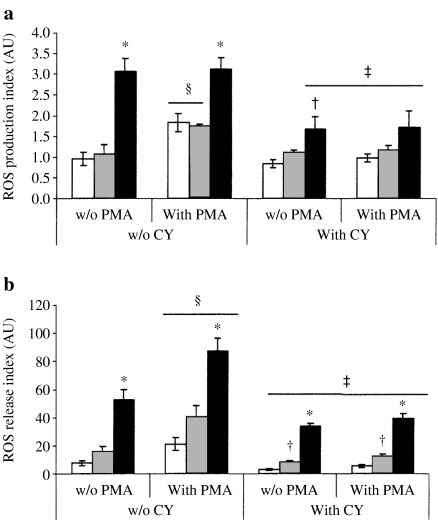

No effect of CY alone or followed by the sham operation has been detected on spontaneous production of ROS in lung PMN. CLP in CY-treated animals has led to significant suppression of this parameter: the spontaneous ROS production dropped to 1.67 ± 0.13 AU compared to 3.07 ± 0.32 AU in the group with no CY treatment (P = 0.029) (Figure 3a). Otherwise, the release of ROS from lung PMN was significantly decreased in all compared groups treated with CY (Figure 3b). Spontaneous ROS release after CLP was decreased to 34.0 ± 1.9 AU compared with 52.8 ± 6.6 AU in animals subjected to CLP alone (P = 0.045). No stimulatory effect of PMA on ROS production and release was found. Moreover, CY significantly decreased PMA-induced ROS responses in all groups treated with CY (Figure 3). Six animals were studied in each group.

Figure 3.

Spontaneous and phorbol-myristate acetate (PMA)-stimulated oxidative response of lung polymorphonuclear neutrophil to experimental sepsis. Cells were isolated from nonoperated (white bars), sham-operated (grey bars) and cecal ligation and puncture-operated animals (black bars) treated with cyclophosphamide (CY) (+CY). ROS production (a) and ROS release (b) were determined as described in Materials and methods. Six animals were studied in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. sham; †P < 0.05 vs. CY treatment alone; ‡CY-untreated mice (–CY); §P < 0.05 vs. spontaneous.

Release of cytoplasmic granules

Data concerning ex vivo assay of lung PMN degranulation (n = 6/group) is presented in Figure 4. Extracellular MPO activity was used as a marker of release of potentially destructive content of PMN azurophilic granules. Spontaneous level of PMN degranulation reached its peak on day 4 after CLP (50.7 ± 3.8 vs. 25.5 ± 1.3 mU/ml × min on day 1, P = 0.0011). The MPO activity after CLP was significantly increased on day 4 and day 7 compared to the matched sham groups (Figure. 4a). Stimulation with PMA significantly increased the level of MPO activity on day 4 and day 7 after CLP, as well as throughout the experimental period after the sham operation. The spontaneous degranulation of lung PMN after CLP was not changed by the CY treatment (21.2 ± 2.9 vs. 25.5 ± 1.3 mU/ml × min). No stimulatory effect of PMA on the degranulation was found. Moreover, CY significantly decreased the capacity to response to PMA in control and sham-operated mice treated with CY (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Spontaneous (spont) and stimulated release of cytoplasmic granules (degranulation) from lung polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) during experimental sepsis. Cells isolated from sham-operated and cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-operated animals were assayed on days 1, 4 and 7 after surgery as described in Materials and methods. (b) Degranulation of lung PMN isolated from nonoperated (control), sham-operated and CLP-operated animals treated with cyclophosphamide (CY) (+CY). Cells isolated from CLP-operated animals were assessed in the absence (black bars) or presence of phorbol-myristate acetate (PMA) (diagonal dashed bars). PMN isolated from sham-operated mice were assessed in the absence (white bars) or presence of PMA (grey bars). Unstimulated (meshed bars) and PMA-treated (horizontal dashed bars) PMN isolated from nonoperated mice served as a control. Six animals were studied every day in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. sham; †P < 0.05 vs. day 1; ‡P < 0.05 vs. CY-untreated mice (–CY); §P < 0.05 vs. spont.

Activity of MMPs in the lung

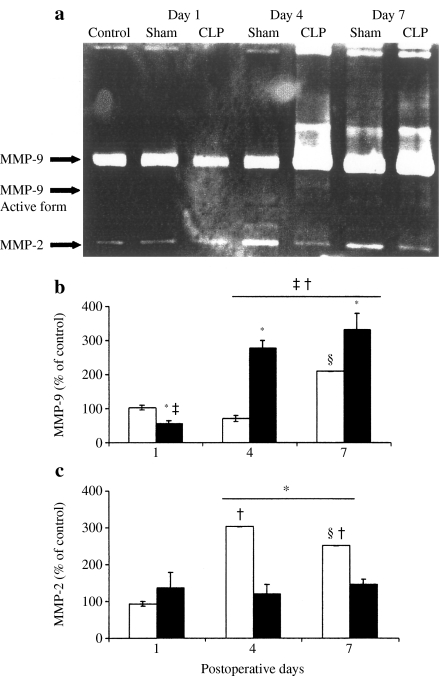

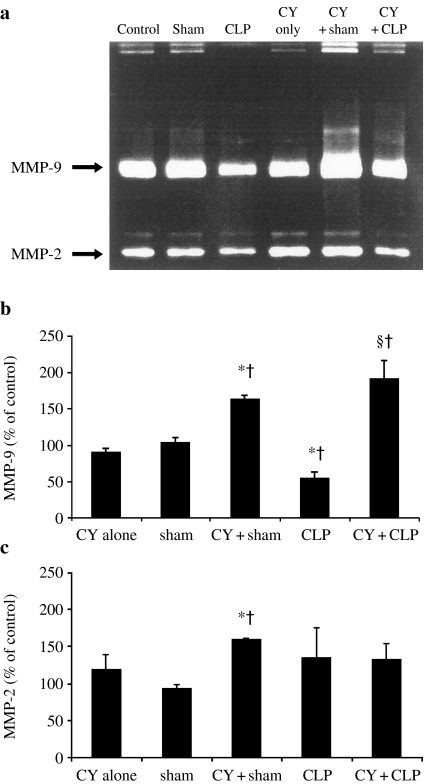

Gelatinase activity of lung MMP-9 (n = 6/group) is presented in Figure 5a, b. It has been reduced on day 1 (56.4 ± 9.4 vs. 103.5 ± 8.4% in sham-operated group, P = 0.019) and increased on day 4 after CLP (277.4 ± 22.9%, P = 0.0039). In sham-operated animals, the same trend was observed, but MMP-9 gelatinase activity decreased on day 4 and increased on day 7 (71.4 ± 9.3 and 210.1 ± 1.3%, respectively, P < 0.0001). The active form of MMP-9 was detected at day 4 and 7 in both CLP- and sham-operated animals (Figure 5a). No change was found in MMP-9 gelatinase activity after CY treatment alone. This parameter was equally increased in both sham- and CLP-operated groups of animals treated with CY: 164.7 ± 5.2 and 194.2 ± 25.8 vs. 89.8 ± 4.8% after CY treatment alone (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.003, respectively) (Figure 6a, b). The active form of MMP-9 was detected also in both sham- and CLP-operated animals treated with CY (Figure 6a). Moreover, this pretreatment prevented a reduction in MMP-9 activity on day 1 after CLP (194.2 ± 25.8 vs. 56.4 ± 9.4%, P = 0.0004).

Figure 5.

(a) Representative gelatin zymogram of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in lungs of nonoperated (control), sham-operated (sham) and cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-operated animals. Densitometric analysis of MMP-9 (b) and MMP-2 (c) activity in lungs from sham (white bars) and CLP (black bars) groups was carried out on days 1, 4 and 7 after surgery, and the parameter was expressed as percentage of control. Six animals were studied every day in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. sham; †P < 0.05 vs. day 1; ‡P < 0.05 vs. control; §P < 0.05 vs. day 4.

Figure 6.

(a) Representative gelatin zymogram of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in lungs of nonoperated (control), sham-operated (sham) and cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-operated animals treated with cyclophosphamide (CY). Results of densitometric analysis of MMP-9 (b) and MMP-2 (c) activity were expressed as percentage of control. Six animals were studied in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. sham; †P < 0.05 vs. control; ‡P < 0.05 vs. CY-untreated mice with CLP.

Gelatinase activity of MMP-2 remained unchanged after CLP throughout the experimental period (Figure 5c). This parameter in sham-operated animals was induced on day 4 (303.8 ± 0.2%) and on day 7 (251.8 ± 0.1%) vs. on day 1 (93.0 ± 7.2%) (P = 0.0002 in both pairs). On days 4 and 7, it was also significantly higher than that in CLP-operated mice. MMP-2 was significantly induced in the CY-treated sham-operated mice: 160.6 ± 0.5% compared to 118.2 ± 21.7% in group of CY treatment alone (P = 0.0065) or to 93.0 ± 7.2% in group of sham operation alone (P < 0.0001) (Figure 6c).

Discussion

In the present study, lung PMN functions were assessed during sepsis and ALI induced by CLP in both CY-treated and normal mice. In immunocompetent animals, peak ALI coincided with massive PMN influx and maximal degranulation and activation of lung MMP-9. CY treatment reduced PMN counts and suppressed the oxidative burst but had no suppressive effect on degranulation and even induced MMP-9 activity. The main finding was the fact that, despite a profound neutropenia, CY treatment did not prevent or attenuate septic lung damage.

In preliminary experiments, we chose a clinically relevant setting of CY treatment (Carter & Livingston 1975), which allows a balance between satisfactory survival with high-power chemotherapeutic activity, manifested by neutropenia. The present study was aimed to investigate the formation of septic ALI in animals with PMN suppression related to the specific kind of CY chemotherapy. Thus, disclosure of general mechanisms of septic lung injury under other neutropenic conditions is beyond the scope of this study.

Despite a profound neutropenia and reduced PMN accumulation in lungs following CLP, no evidence of ALI attenuation in the CY-treated mice with CLP was observed on histological examination. Clinical trials have shown that the use of CY for months and even years may induce pulmonary toxicity (Malik et al. 1996). In the present study, a single dose of CY was used, and only a mild focal hyperaemia was induced. Thus, the direct effect of CY on lung tissue might not be responsible for our histological findings: The prominent hyperaemia and stasis, collapse of several alveoli and moderate inflammatory infiltration of alveolar walls observed following CLP in CY-treated animals were apparently attributed to the septic ALI. Moreover, similar histological changes in the both CLP groups excluded the increase of CY pulmonary toxicity in sepsis.

It is interesting that CY-treated animals revealed the significant lung damage or increased lung MMP-9 release even when subjected to the sham operation (Figures 1a and 6b). Additionally, CY increased the rate of lung PMN apoptosis, which was significantly reduced following CLP. Other investigators have also reported that CY suppresses metabolism and affects life cycle of lung macrophages decreasing their cytotoxicity and ability to mediate tissue damage (Venkatesan et al. 1998; Santosuosso et al. 2002). Taken together, this data suggests that CY decreased threshold of the viability of lung cells and therefore their resistance to damaging factors during systemic inflammation and sepsis.

ROS and hydrolytic enzymes released from activated PMNs are two well-known and extensively investigated major factors mediating organ damage (Lee et al. 1981; Ricou et al. 1996; Metnitz et al. 1999; Corbel et al. 2000; Haslett et al. 2000); therefore, detailed interpretation of the relationship between their spontaneous and PMA-stimulated release in sepsis and ALI is beyond the scope of this study. The present report focused on the finding that these factors respond to the septic insult in a different time.

After first 24 h of CLP, maximal production and release of ROS was observed, which gradually decreased with time. Our results are consistent with data of other investigators, which explained this phenomenon by exhaustion of PMN overexposed to inflammatory mediators (Pascual et al. 1997; Czermak et al. 1999; Metnitz et al. 1999). On days 4–7 after CLP, maximal release of enzyme-containing cytoplasmic granules was detected by MPO assay in vitro and MMP-9 assay in vivo. The different timing of maximal release of the two major damaging factors from lung PMN is consistent with other reports which have shown that early release of ROS leading to inactivation of local proteinase inhibitors enhances proteolytic enzyme-mediated tissue injury after the delayed degranulation (Windsor et al. 1993; Jaeschke & Smith 1997). Biphasic response of PMN to the septic insult is well explained by the paradigm of concentration- and time-dependent PMN activation stating that different PMN responses are induced by different grades of stimulation (van Eeden et al. 1999). It has also been demonstrated that azurophilic granules containing MPO, elastase and most of collagenases require either higher levels or substantially prolonged time of stimulation for extracellular release (Tapper 1996). Moreover, ROS have been shown to be involved in NF-κB activation followed by the induction of proinflammatory genes (Jaeschke & Smith 1997). Thus, early oxidative response in PMN may modulate the following leucocyte degranulation.

Several investigators have indicated a critical role of the proteolytic enzymes in septic ALI (Smedly et al. 1986; Jaeschke & Smith 1997) and suggested that upregulation of MMP-9 is involved in the injury progression (Delclaux et al. 1997; Gibbs et al. 1999; Corbel et al. 2000; Warner et al. 2001). In the present study, induction of MMP-9 coincided with the peak of PMN degranulation and the maximum of histological manifestations of ALI (hyperaemia, atelectasis, alveolar exudation and PMN infiltration). The initially decreased activity of MMP-9 on day 1 after CLP is most probably associated to an inhibitory effect of nitric oxide (Radomski et al. 1998) plentifully produced in lungs with ALI early onset (Sittipunt et al. 2001). This decrease was completely abrogated in CY-treated mice, due to a significant suppressive effect of CY on the production of nitric oxide (Hickman-Davis et al. 2001). Unlike MMP-9, a significant expression of MMP-2 was detected in lung epithelial cells (Corbel et al. 2000; Araya et al. 2001). As CLP results in a minimal alveolar damage, an induction of MMP-2 is not anticipated. Additionally, MMP-2 expression is transcriptionally activated by coupling with an apoptogenic p53 transcription factor (Bian & Sun 1997). The antiapoptotic effect of sepsis in several cell types has been shown in the present study and by others (Liacos et al. 2001; Haerter et al. 2002), and at least in part, this relates to p53 downregulation. Alternatively, the sham operation had no suppressive effect on PMN apoptosis and simultaneously induced lung MMP-2. Thus, p53-mediated antiapoptotic effects of sepsis on lung cells might block the induction of MMP-2 after CLP.

The lack of ALI attenuation in CY-treated neutropenic mice with CLP may have a reason. The drop of PMN count in the blood was not associated with a full depletion of PMN in the lung tissue, and therefore, residual PMN in lungs might still cause ALI. This suggestion may be true if CY-treated lung PMN have preserved their ability to respond to CLP by activation and release of ROS and granules. Despite the clear manifestations of CY myelotoxicity, several doses of CY have been shown to facilitate immune response, including cell-mediated cytotoxicity and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Bass & Mastrangelo 1998). Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that CY can stimulate PMN cell cytotoxicity by an increase in Fc-receptors expression (Palermo et al. 1987), and induce, similar to our finding, the lung MMP-9 release (Venkatesan et al. 1998). The definitive source of the released MMP-9 is still unknown, because both PMN and macrophages are able to express and release large amounts of MMP-9 under inflammatory conditions (Gibbs et al. 1999; Warner et al. 2001). However, as CY has a severe apoptogenic effect on lung macrophages (Venkatesan et al. 1998; Santosuosso et al. 2002), their ability to play a leading role in the tissue damage looks highly questionable. Finally, CY and other chemotherapeutic agents selectively suppress only part of PMN functions (Cairo et al. 1986). This is in accordance with our data showing that CY significantly impaired production and release of ROS by lung PMN but had no suppressive effects on their spontaneous degranulation. This selective impairment of PMN functions may have risen from different susceptibility of the different cell systems to the action of CY and/or its derivatives.

In summary, our results show that CLP induced a similar lung injury in both CY-treated and immunocompetent mice. Despite profound neutropenia, significantly reduced lung influx and partial suppression of PMN functions, CY treatment did not prevent or attenuate CLP-induced ALI. These findings suggest a critical role of the residual lung PMN and activation of MMP-9 in septic lung injury during CY chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Rambam Medical Center and the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Araya J, Maruyama M, Sassa K, et al. Ionizing radiation enhances matrix metalloproteinase-2 production on human lung epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2001;280:L30–L38. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.1.L30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E, Attalah H, Yang K, et al. Exacerbation by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor of prior acute lung injury: implication of neutrophils. Crit. Care Med. 2002;30:2115–2122. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200209000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachofen M, Weibel ER. Structural alterations of lung parenchyma in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Clin. Chest. Med. 1982;3:35–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird BR, Cheronis JC, Sandhaus RA, et al. O2 metabolites and neutrophil elastase synergistically cause edematous injury in isolated rat lungs. J. Appl. Physiol. 1986;61:2224–2229. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.6.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass K, Mastrangelo MJ. Immunopotentiation with low-dose cyclophosphamide in the active specific immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1998;47:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s002620050498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian J, Sun Y. Transcriptional activation by p53 of the human type IV collagenase promoter. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997;17:6330–6338. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch F, Ferrer A, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone in the treatment of resistant or relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2002;119:976–984. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairo MS, Mallett C, VandeVen C, Kempert P, Bennetts GA, Katz J. Impaired in vitro polymorphonuclear function secondary to the chemotherapeutic effects of vincristine, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, and actinomycin D. J. Clin. Oncol. 1986;4:798–804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.5.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SK, Livingston RB. Cyclophosphamide in solid tumors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 1975;2:295–322. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(75)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbel M, Boichot E, Lagente V. Role of gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 in tissue remodeling following acute lung injury. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2000;33:749–754. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2000000700004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czermak BJ, Sarma V, Pierson CL, et al. Protective effects of C5a blockade in sepsis. Nat. Med. 1999;5:788–792. doi: 10.1038/10512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delclaux C, D'Ortho MP, Delacourt C, et al. Gelatinases in epithelial lining fluid of patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:L442–L451. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.3.L442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry G, Lonchampt M, Pennel L, et al. Activation of MMP-9 by neutrophil elastase in an in vivo model of acute lung injury. FEBS Lett. 1997;402:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gepstein A, Shapiro S, Arbel E, Lahat N, Livne E. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases in articular cartilage of temporomandibular and knee joints of mice during growth, maturation, and aging. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3240–3250. doi: 10.1002/art.10690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs DF, Shanley TP, Warner RL, et al. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in models of macrophage-dependent acute lung injury. Evidence for alveolar macrophage as source of proteinases. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1999;20:1145–1154. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.6.3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haerter L, Keel M, Steckholzer U, Ungethuem U, Trentz O, Ertel W. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases during granulocyte apoptosis in patients with severe sepsis. Shock. 2002;18:401–406. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslett C, Donelly S, Hirani N. Neutrophils in acute lung injury. In: Marshall JC, Cohen J, editors. Immune Response in the Critically Ill. New York: Springer; 2000. pp. 210–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman-Davis JM, Lindsey JR, Matalon S. Cyclophosphamide decreases nitrotyrosine formation and inhibits nitric oxide production by alveolar macrophages in mycoplasmosis. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:6401–6410. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6401-6410.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh M, Mahamid E, Bashenko Y, Hirsh I, Krausz MM. Overexpression of the high-affinity Fc-γ receptor CD64 is associated with leukocyte dysfunction in sepsis. Shock. 2001;16:102–108. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt PG, Degebrodt A, Venaille T, et al. Preparation of interstitial lung cells by enzymatic digestion of tissue slices: preliminary characterization by morphology and performance in functional assays. Immunology. 1985;54:139–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Smith CW. Mechanisms of neutrophil-induced parenchymal cell injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1997;61:647–653. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl MG, Ostermann H, Thomas M, et al. Inflammatory mediators in broncho-alveolar lavage fluid and plasma in leukocytopenic patients with septic shock-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 1998;26:1194–1199. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199807000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagasse E, Weissman IL. Flow cytometric identification of murine neutrophils and monocytes. J. Immunol. Methods. 1996;197:139–150. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CT, Fein AM, Lippmann M, et al. Elastolytic activity in pulmonary lavage fluid from patients with adult respiratory-distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1981;304:192–196. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198101223040402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liacos C, Katsaragakis S, Konstadoulakis MM, et al. Apoptosis in cells of broncho-alveolar lavage: a cellular reaction in patients who die with sepsis and respiratory failure. Crit. Care Med. 2001;29:2310–2317. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik SY, Myers JL, DeRemee RA, Specks U. Lung toxicity associated with cyclophosphamide use: two distinct patterns. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996;154:1851–1856. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.6.8970380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metnitz PGH, Bartens C, Fischer M, et al. Antioxidant status in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:180–185. doi: 10.1007/s001340050813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montillo M, Tedeschi A, O'Brien S, et al. Phase II study of cladribine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2003;97:114–120. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ognibene FP, Martin SE, Parker M, et al. Adult respiratory distress syndrome in patients with severe neutropenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986;315:547–551. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608283150904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham KM, Bowen PE. Oxidative stress in critical care: is antioxidant supplementation beneficial? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1998;98:1001–1008. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo MS, Giordano M, Serebrinsky GP, Geffner JR, Ballart I, Isturiz MA. Cyclophosphamide augments ADCC by increasing the expression of Fc-receptors. Immunol. Lett. 1987;15:83–87. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(87)90081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual C, Karzai W, Meier-Hellmann A, Bredle DL, Reinhart K. A controlled study of leukocyte activation in septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:743–748. doi: 10.1007/s001340050403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radomski A, Sawicki G, Olson DM, Radomski MW. The role of nitric oxide and metallo-proteinases in the pathogenesis of hyperoxia-induced lung injury in newborn rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:1455–1462. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricou B, Nicod L, Lacraz S, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases and TIMP in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996;154:346–352. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldo JE, Rogers RM. Adult respiratory-distress syndrome: changing concepts of lung injury and repair. N. Engl. J. Med. 1982;306:900–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204153061504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva RC, Guntupalli KK. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care Clin. 1997;13:503–521. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santosuosso M, Divangahi M, Zganiacz A, Xing Z. Reduced tissue macrophage population in the lung by anticancer agent cyclophosphamide: restoration by local granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor gene transfer. Blood. 2002;99:1246–1252. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sittipunt C, Steinberg KP, Ruzinski JT, et al. Nitric oxide and nitrotyrosine in the lungs of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001;163:503–510. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2004187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedly LA, Tonnesen MG, Sandhaus RA, et al. Neutrophil-mediated injury to endothelial cells. Enhancement by endotoxin and essential role of neutrophil elastase. J. Clin. Invest. 1986;77:1233–1243. doi: 10.1172/JCI112426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Ota H, Sasagawa S, Sakatani T, Fujikura T. Assay method for myeloperoxidase in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Anal. Biochem. 1983;132:345–352. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapper H. The secretion of preformed granules by macrophages and neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1996;59:613–622. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eeden SF, Klut ME, Walker BAM, Hogg JC. The use of flow cytometry to measure neutrophil functions. J. Immunol. Methods. 1999;232:23–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan N, Punithavathi D, Chandrakasan G. Biochemical and connective tissue changes in cyclophosphamide-induced lung fibrosis in rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;56:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner RL, Beltran L, Younkin EM, et al. Role of stromelysin 1 and gelatinase B in experimental acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2001;24:537–544. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.5.4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterman KA, Baue AE, Chaudry IH. Sepsis and septic shock – a review of laboratory models and a proposal. J. Surg. Res. 1980;29:189–201. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(80)90037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickel DJ, Cheadle WG, Mercer-Jones MA, Garrison RN. Poor outcome from peritonitis is caused by disease acuity and organ failure, not recurrent peritoneal infection. Ann. Surg. 1997;225:744–756. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199706000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor ACJ, Mullen PG, Fowler AA, Sugerman HJ. Role of neutrophil in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Br. J. Surg. 1993;80:10–17. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]