Abstract

Haptoglobin is an acute phase protein known to be highly expressed in the liver. Recently, we showed increased local arterial haptoglobin expression after flow-induced arterial remodelling and found that haptoglobin is involved in cell migration and arterial restructuring probably through accumulation of a temporary gelatin matrix. Since cell migration and matrix turnover are important features in the pathology of arthritis and cancer, we hypothesized that haptoglobin is also locally expressed in arthritic and oncological tissues. In this study, we investigated local haptoglobin expression in arthritic rats (n = 12) using semi-quantitative PCR and Western blotting, and we studied haptoglobin mRNA localization in human kidney tumours (n = 3) using in situ hybridization. The arthritic rats demonstrated an increase of haptoglobin mRNA (2.5-fold, P < 0.001) and protein (2.6-fold, P < 0.001) in the arthritic Achilles tendon. Haptoglobin protein was also increased in the arthritic ankle (2.6-fold, P < 0.001) but not in the non-arthritic knee. In human kidney tumours, tumour and stromal cells produced haptoglobin mRNA. This study shows that the liver protein haptoglobin is, in addition to the artery, also expressed in arthritic and oncological tissues that are recognized for enhanced cell migration and matrix turnover.

Keywords: arthritis, cancer, expression, haptoglobin

Introduction

Haptoglobin is mainly produced in the liver, but expression can also be induced in various other tissues (D'Armiento et al. 1997). Recently, we demonstrated that the acute phase protein haptoglobin is a natural inhibitor of collagen degradation and is locally expressed by fibroblasts in the arterial wall (de Kleijn et al. 2002; Smeets et al. 2002). Haptoglobin plays an important role in cell migration and arterial restructuring. Collagen turnover is an important feature in many physiological processes like growth and wound healing. Enhanced collagen degradation is observed and often causally related with severe tissue destruction or malfunction, as can be seen in the pathological processes of arthritis (Jackson et al. 2001) and cancer (Westermarck & Kähäri 1999).

The importance of haptoglobin in cell migration and extracellular matrix degradation suggests a role for haptoglobin in arthritis and cancer. Both disease processes are characterized by increased cell migration and degradation of the extracellular matrix. Invasion of arthritic fibroblast-like synoviocytes rapidly destroys a cartilage matrix (Muller-Ladner et al. 1996). In cancer, the migration of cells plays a role in tumour angiogenesis, progression and metastasis (see Bashyam 2002; for review).

Although sero-epidemiological studies reported increased haptoglobin serum levels during arthritis and carcinogenesis (Thompson et al. 1989, 1991), local expression of haptoglobin in arthritic and oncological tissues has not been studied before. We hypothesized that local expression of haptoglobin will increase in arthritic and oncological tissues in which cell migration and matrix remodelling are important features.

In the present study, we investigated local expression of haptoglobin in arthritis and cancer and show that haptoglobin is locally expressed in arthritic and oncological tissues in which extracellular matrix turnover and cell migration are predominant features.

Methods

Tissue material

Arthritic rats In 6–8 weeks-old inbred male Lewis rats (n = 6), arthritis was induced by one single intradermal injection of 5 mg/mL heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (strain H37Ra, Difco) in Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Difco) in the base of the tail (Cobelens et al. 2000); six additional rats were used as control. The rats were killed after 6 weeks. The arthritic ankle and Achilles tendon as well as the unaffected knee were removed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for RNA and protein extraction.

All investigations conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 85-23, 1985) and were approved by the ethical committee on animal experiments of the University Medical Centre Utrecht.

Human kidney tumours Surgical specimens from human Grawitz kidney tumours were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for in situ hybridization (n = 3).

RNA and protein extraction

The frozen tissue samples were ground in liquid nitrogen, using a pestle and mortar. RNA and protein were extracted using 1 mL Tri-puretm. Isolation Reagent (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Specific sets of primers were constructed using software at CMBI (Nijmegen). Reverse transcription was carried out with 500 ηg total RNA using superscript II (Life) according to the manufacturer's protocol. To confirm the identity of the amplified cDNA products, PCR products were ligated into the pGEM®-T Easy Vector (Promega) and sequenced using the T7 sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (Amersham).

PCR amplification on arthritic rats was performed using 11 µL cDNA, 200 µm dNTP, 1× reaction buffer (BRL), 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (BRL) and 1 µm of each primer. The reaction was run on 8% polyacrylamide gels, stained with ethidium bromide and analysed using the Gel-Doc 1000 system. Control experiments were performed to determine the range of PCR cycles over which amplification efficiency remained constant and to demonstrate that the amount of PCR product was directly proportional to the amount of input cDNA. PCR amplification on total RNA that had not been reversed transcribed showed that no genomic DNA was present (data not shown). Data were corrected for the amount of β-actin mRNA, which was used as an internal standard.

The following oligonucleotides were used as primers: rat haptoglobin (forward primer 5′-TGATCAAGCTCAAACAGAAAGTG-3′, reverse primer 5′-CATAGCAAGTGTCTTCCTCATACTT-3′); rat β-actin (forward primer 5′-TAAGGAACAACCCAGCATCC-3′, reverse primer 5′-TAGAGCCACCAATCCACACA-3′).

In situ hybridization

Human haptoglobin cDNA in pGEM®-T Easy Vector was linearized and used as template to obtain digoxigenin (DIG, Roche) labelled RNA probes, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Tissue segments were cut into 8 µm sections and transferred to Superfrost plus slides (Menzel Glazer) and stored at −80 °C until use.

After defrosting, sections were treated with 0.2 m HCl for 20 min at RT, washed three times with PBS for 5 min and treated with proteinase K (Roche 10 µg/mL) for 10–15 min at 37 °C in PBS. The sections were washed with PBS and fixed at RT for 5 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and treated twice for 5 min with acetic anhydride in triethylacetate (TEA, 185 µL acetyl anhydride in 0.1 m TEA). Sections were subsequently washed twice in 2× SSC for 5 min at RT, followed by 5 min in 2× SSC/50% formamide at 37 °C.

For pre-hybridization, 100 µL hybridization mix (50% formamide, 1 mg/mL tRNA, 1× Denhardt's, 10% dextran sulphate, 4× SSC) was added to the slide and incubated for 1 h at 46 °C. After °/n hybridization at 46 °C, sections were washed with 0.1× SSC at 45 °C for 15 min, followed by RNase treatment (40 µg/mL RNase A, 1 mm EDTA pH 8.2, 2× SSC) for 15 min at RT and washed again with 0.1× SSC at 45 °C for 15 min Before detection with 1/500 sheep-α-DIG AP (Boehringer), sections were rinsed with 2× SSC and 100 mm Tris pH 7.4–150 mm NaCl at RT. Detection with NCBI/NBT (Roche) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Western blotting

Equal amounts of protein (5 µg/lane) were separated on a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto Hybond ECL (Amersham) in blotting buffer (14.4 g/L glycine, 3.03 g/L Tris, 20% methanol). The membrane was blocked °/n in PBS−0.1% Tween−5% non-fat dry milk (PBSTP). The membrane was incubated for 1 h at RT with 1/4000 goat-α-human haptoglobin (ICN), followed by 1/1000 biotinylated rabbit-α-goat and 1/2000 streptavidine-HRPO. All incubation steps were performed in PBSTP and the membrane was subsequently washed three times in PBS−0.1% Tween (PBST). Detection occurred using ECL (NEN Life Science products) and exposure to X-Omat Blue XB-1 film (Kodak).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The data for arthritic rats were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. P-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Local haptoglobin expression in arthritic tissue

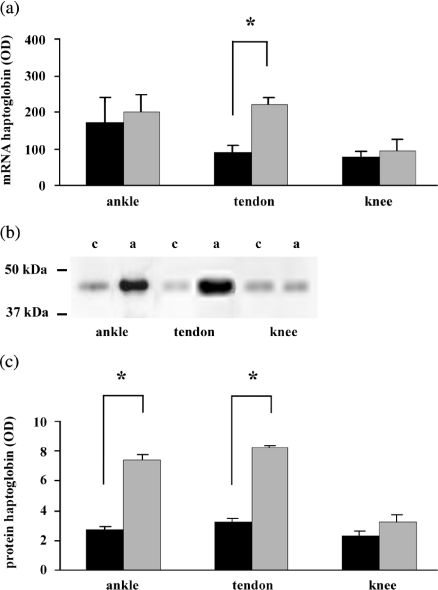

Haptoglobin expression in the arthritic rats (n = 12) was investigated using the affected ankle and Achilles tendon and the unaffected knee. Haptoglobin mRNA expression was 2.5-fold increased in the Achilles tendon in arthritic rats (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1a). Haptoglobin mRNA levels in the ankle revealed large fluctuations within the two groups but showed no significant difference between the arthritic and control rats (P = 0.51) (Fig. 1a). No significant difference was found in haptoglobin mRNA levels in the unaffected knee between arthritic and control rats.

Figure 1.

Haptoglobin mRNA and protein expression in arthritic rats. (a) Haptoglobin mRNA levels in control and arthritic rats; (b) Western blot analysis of haptoglobin protein in ankle, tendon and knee (c = control rats, a = arthritic rats); (c) haptoglobin protein levels in control and arthritic rats. n = 9, *P < 0.001, black bar = control rats, grey bar = arthritic rats.

Western blotting revealed that haptoglobin protein expression was 2.6-fold increased in both the arthritic ankle and the arthritic Achilles tendon (P < 0.001) from arthritic rats (Fig. 1b + c). No difference in haptoglobin protein expression was found in the unaffected knee.

Haptoglobin expression in oncological tissue

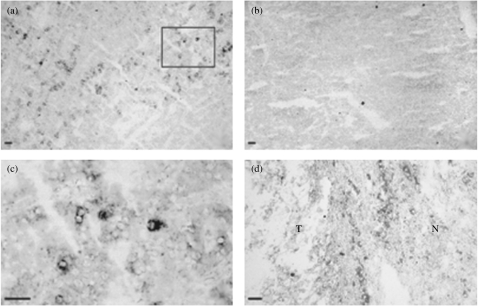

In situ hybridization on human Grawitz tumours (n = 3) demonstrated haptoglobin expression by tumour cells located in invasive parts of the tumour (Fig. 2a + c). Alternate sections hybridized with a control sense probe showed no staining (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, positive staining was also found in surrounding stromal tissue (Fig. 2d) by macrophages and fibroblast-like cells (data not shown).

Figure 2.

In situ hybridization on human kidney tumours using an antisense probe against human haptoglobin mRNA. (a) Haptoglobin mRNA expression by invasive tumour cells (magnification = 100×); (b) in situ hybridization using a sense probe (magnification = 100×); (c) detail of the indicated area in (a) (magnification = 400×); (d) haptoglobin mRNA expression by surrounding stromal cells (magnification = 200×). T = tumour tissue, N = normal kidney tissue, bar = 25 µm.

Discussion

Cell migration and collagen degradation are key events in arthritis (Firestein 1996; Jackson et al. 2001), tumour progression and tumour metastasis (Westermarck & Kähäri 1999; Bashyam 2002). Enhanced degradation of collagen is required for cell migration to occur (Li et al. 2000; Pilcher et al. 1997). Recently, we have identified haptoglobin as an essential factor for cell migration (de Kleijn et al. 2002). Haptoglobin knockout cells demonstrated impaired migration that could be restored by supplementation of exogenous haptoglobin to the cells. Although serum haptoglobin levels have previously been associated with the progression and outcome of arthritis and cancer, local haptoglobin synthesis has not been studied in these pathological tissues before. As cell migration is believed to be a tightly controlled process that depends on matrix degradation in the immediate surrounding of cells (Singer et al. 1995), we investigated in the present study the local expression of haptoglobin in arthritic and oncological tissues.

Previous studies have demonstrated increased haptoglobin levels in the serum during arthritis (Thompson et al. 1989). In arthritic rats, the affected ankle and Achilles tendon showed significantly increased levels of local haptoglobin expression. No difference was found in the unaffected knee, demonstrating that increased haptoglobin protein levels in the affected joints are the result of local haptoglobin expression and not caused by extravasation of haptoglobin from the serum.

Fibroblast-like synoviocytes of human arthritic tissue migrate in vivo into cartilage matrix resulting in a destructive pannus as is found in human arthritic tissue (Muller-Ladner et al. 1996). These fibroblast-like synoviocytes are the main producers of the high local levels of MMPs (Vincenti et al. 1994; Firestein 1996) that correlate with the severity of the lesion and are mainly produced in arthritic tissue (Firestein 1996). We infer that local haptoglobin expression facilitates cell migration in the cartilage and may therefore play a role in the progression of arthritis.

Haptoglobin mRNA was also locally expressed in kidney tumour tissue. Cells staining positive for haptoglobin mRNA were mainly found in the invasive part of the tumour and in the surrounding stroma. Haptoglobin protein levels were not measured in the tumour samples because of contamination with blood residues. The localization of haptoglobin correlated with the earlier described expression pattern of MMP-2, which is mainly synthesized by fibroblasts in the stroma surrounding the tumours, although the active protein can also be found around tumour cells (Davies et al. 1993; Wolf et al. 1993). Furthermore, MMP synthesis by surrounding stromal cells is necessary for tumour metastasis, indicating the important role of stromal-derived MMP activity (Itoh et al. 1999). Increased expression of MMPs has been associated with tumour invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis and the controlled degradation of surrounding stromal matrix appears to be essential for these three processes (Davies et al. 1993; Wolf et al. 1993; Heppner et al. 1996). We suggest that haptoglobin provides tumour cells with an additional level of MMP-2 regulation in addition to the controlled activation via MT1-MMP (Zhou et al. 2000; de Kleijn et al. 2001), thereby facilitating tumour cell invasion and metastasis.

Elevations in serum haptoglobin levels during pathological processes have been demonstrated by various sero-epidemiological studies. However, local expression of haptoglobin in pathological tissues has not been studied. There are two possible explanations for the necessity of increased local haptoglobin synthesis in pathological processes, despite the normal presence of haptoglobin in the serum. First, increased local expression might be the only way to achieve high local concentrations of haptoglobin, which are necessary for the inhibition of local gelatinase activity. Second, local production of haptoglobin might reflect the synthesis of a functionally distinct protein, compared to haptoglobin produced in the liver.

It is known for several proteins like eNOS or Toll-like receptor-4, that changes in the amount and nature of glycosylation can alter protein function drastically (Verbeke et al. 2000; da Silva Correia & Ulevitch 2002). Haptoglobin is a protein with several post-translational glycosylations on the β-chains (Chow et al. 1984), and alterations in the glycosylation pattern of haptoglobin have been described during the development and progression of various pathological processes and even appear to have prognostic values for some diseases (Turner 1995). Increased local haptoglobin expression with other glycosylation patterns might therefore reflect an altered function compared to haptoglobin produced in the liver.

A limitation of this study is that it is purely descriptive and we can only speculate about the exact function of haptoglobin in these tissues. However, haptoglobin is locally produced in both pathological tissues and is reported to be involved in cell migration and matrix degradation. Since cell migration and matrix degradation are important features in arthritis and cancer, this suggests a local role for haptoglobin in these processes and supports a role for haptoglobin in the initial response to tissue injury. This is in accordance with studies in haptoglobin knock-out mice that showed a delayed response to arterial (de Kleijn et al. 2002) or kidney injury (Lim et al. 1998).

In summary, we have investigated local haptoglobin expression in arthritis and cancer, where cell migration and matrix remodelling are important features, and describe an up-regulation of local haptoglobin expression in arthritic and oncological tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elianne Koop for providing tissue samples of human kidney tumours and Roel Goldschmeding for the evaluation of the human kidney tumours. This study was supported by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO 902-16-239 and 902-16-222) and the Netherlands Heart Foundation (99-209).

References

- Bashyam MD. Understanding cancer metastasis: an urgent need for using differential gene expression analysis. Cancer. 2002;94:1821–1829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow V, Kurosky A, Murray RK. Studies on the biosynthesis of rabbit haptoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:6622–6629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobelens PM, Heijnen CJ, Nieuwenhuis EES, et al. Treatment of adjuvant-induced arthritis by oral administration of mycobacterial Hsp65 during disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2694–2702. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2694::AID-ANR9>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Armiento J, Dalal SS, Chada K. Tissue, temporal and inducible expression pattern of haptoglobin in mice. Gene. 1997;195:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies B, Miles DW, Happerfield LC, et al. Activity of type IV collagenases in benign and malignant breast disease. Br. J. Cancer. 1993;67:1126–1131. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein GS. Invasive fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1781–1790. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner KJ, Matrisian LM, Jensen RA, Rodgers WH. Expression of most matrix metalloproteinase family members in breast cancer represents a tumor-induced host response. Am. J. Pathol. 1996;149:273–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Tanioka M, Matsuda H, et al. Experimental metastasis is suppressed in MMP-9-deficient mice. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 1999;17:177–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1006603723759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Nguyen M, Arkell J, Sambrook P. Selective matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) inhibition in rheumatoid arthritis-targeting gelatinase A activation. Inflamm. Res. 2001;50:183–186. doi: 10.1007/s000110050743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kleijn DPV, Sluijter JPG, Smit J, et al. Furin and membrane type-1 metalloproteinase mRNA levels and activation of metalloproteinase-2 are associated with arterial remodeling. FEBS Lett. 2001;501:37–41. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kleijn DP, Smeets MB, Kemmeren PP, et al. Acute-phase protein haptoglobin is a cell migration factor involved in arterial restructuring. FASEB J. 2002;16:1123–1125. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0019fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Chow LH, Pickering JG. Cell surface-bound collagenase-1 and focal substrate degradation stimulate the rear release of motile vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35384–35392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SK, Kim H, Lim SK, et al. Increased susceptibility in Hp knockout mice during acute hemolysis. Blood. 1998;92:1870–1877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Ladner U, Kriegsmann J, Franklin BN, et al. Synovial fibroblasts of patients with rheumatoid arthritis attach to and invade normal human cartilage when engrafted into SCID mice. Am. J. Pathol. 1996;149:1607–1615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher BK, Dumin JA, Sudbeck BD, Krane SM, Welgus HG, Parks WC. The activity of collagenase-1 is required for keratinocyte migration on a type I collagen matrix. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:1445–1457. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Correia J, Ulevitch RJ. MD-2 and TLR4 N-linked glycosylations are important for a functional lipopolysaccharide receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:1845–1854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109910200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer II, Kawka DW, Bayne EK, et al. VDIPEN, a metalloproteinase-generated neoepitope, is induced and immunolocalized in articular cartilage during inflammatory arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:2178–2186. doi: 10.1172/JCI117907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets MB, Pasterkamp G, Lim SK, Velema E, van Middelaar B, De Kleijn DPV. Nitric oxide synthesis is involved in arterial haptoglobin expression after sustained flow changes. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:221–224. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S, Kelly CA, Griffiths ID, Turner GA. Abnormally-fucosylated serum haptoglobin in patients with inflammatory joint disease. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1989;184:251–258. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(89)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S, Cantwell BM, Cornell C, Turner GA. Abnormally-fucosylated haptoglobin: a cancer marker for tumour burden but not gross liver metastasis. Br. J. Cancer. 1991;64:386–390. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner GA. Haptoglobin a potential reporter molecule for glycosylation changes in disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1995;376:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke P, Perichon M, Friguet B, Bakala H. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase activity by early and advanced glycation end products in cultured rabbit proximal tubular epithelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1502:481–494. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincenti MP, Clark IM, Brinckerhoff CE. Using inhibitors of metalloproteinases to treat arthritis. Arthritis Reum. 1994;37:1115–1126. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermarck J, Kähäri V-M. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases expression in tumor invasion. FASEB J. 1999;13:781–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf C, Rouyer N, Lutz Y, et al. Stomelysin 3 belongs to a subgroup of proteinases expressed in breast carcinoma fibroblastic cells and possibly implicated in tumor progression. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:1843–1847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou A, Apte SS, Soininen R, et al. Impaired endochondral ossification and angiogenesis in mice deficient in membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:4052–4057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060037197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]