Abstract

This study utilized both cDNA microarray and two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis technology to investigate the multiple interactions of genes and proteins involved in uterine leiomyoma pathophysiology. Also, the gene ontology analysis was used to systematically characterize the global expression profiles at cellular process levels. We profiled differentially expressed transcriptome and proteome in six-paired leiomyoma and normal myometrium. Screening up to 17 000 genes identified 21 upregulated and 50 downregulated genes. The gene-expression profiles were classified into mutually dependent 420 functional sets, resulting in 611 cellular processes according to the gene ontology. Also, protein analysis using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis identified 33 proteins (17 upregulated and 16 downregulated) of more than 500 total spots, which was classified into 302 cellular processes. Of these functional profilings, downregulations of transcriptomes and proteoms were shown in cell adhesion, cell motility, organogenesis, enzyme regulator, structural molecule activity and response to external stimulus functional activities that are supposed to play important roles in pathophysiology. In contrast, the upregulation was only shown in nucleic acid-binding activity. Taken together, potentially significant pathogenetic cellular processes were identified and showed that the downregulated functional profiling has a significant impact on the discovery of pathogenic pathway in leiomyoma. Also, the gene ontology analysis can overcome the complexity of expression profiles of cDNA microarray and two-dimensional protein analysis via its cellular process-level approach. Therefore, a valuable prognostic candidate gene with relevance to disease-specific pathogenesis can be found at cellular process levels.

Keywords: cDNA microarray, gene ontology, leiomyoma, proteomics, uterine leiomyoma

Uterine leiomyomas are benign neoplasms arising from the myometrial compartment of the uterus and are the most common gynaecological neoplasm in reproductive-age women (Buttram & Reiter 1981). This benign tumour represents significant reproductive health problems such as abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, constipation and reproductive dysfunction. It is intriguing that 60% of leiomyomata do not exhibit a cytogenetic abnormality (Ligon & Morton 2001). Detailed studies of syndromes of leiomyoma development have not elucidated the aetiology of leiomyoma formation in common cases (McKeeby et al. 2001). Recently, cytogenetic, molecular and epidemiologic studies have suggested a strong genetic component to fibroid pathogenesis and pathobiology (Vu et al. 1998; Ligon & Morton 2001). Although a number of leiomyoma-related genes and cellular processes have been studied, many of the molecular events involved in the leiomyoma pathophysiology are still unclear, because a gene can be involved in multiple, independently regulated leiomyoma-specific pathways. Moreover, many studies on leiomyoma pathogenesis lack physiological relevance because they were performed using fewer genes and established in specific cell lines.

Although it is becoming increasingly clear that there are wide variations in the efficiency of tumour therapy among different cell types, little is known about the mechanism by which genes or gene complexes are directly pathogenetic. Here, to quantitatively understand the possible multiple relationships between differentially expressed profiles of a gene and proteins, the annotation project, directed by the Gene Ontology Consortium (http://www.geneontology.org), was used (Ashburner et al. 2000). Despite the significance of functional analysis in tumour research, the gene ontology analysis has not been widely used in tumorigenesis, mainly due to its complexity and rapidly evolving property. With the gene ontology analysis, the regulated expression profiles are organized into three separated ontologies comprised of biological process, cellular component and molecular function and define a set of well-defined terms and relationships by which the role of a particular gene, gene product or gene-product group can be interpreted (Doniger et al. 2003). Thus, an advanced strategy for the identification of preferential tumour-specific pathway would be possible by using the gene ontology analysis.

In this study, both cDNA microarray and two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis technology were used to obtain valuable information about global regulation of leiomyoma and specific pathogenetic cellular processes. The analysed functional profiles were clearly differentiated and disease dependent, which resulted in finding a large subset of cellular functional changes that could be described as tending to increase or decrease. The combination of the genome and proteome technology with the gene ontology analysis was identified as being descriptive of the biology of leiomyomas, which suggests that it is a valuable tool for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in pathogenetic research.

Materials and methods

Samples

Uterine tissues were obtained from involved and uninvolved tissue of six patients according to procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University. Presence or absence of leiomyoma lesion was determined in all cases from the patients' medical history and clinical evaluation. None of the patients received any hormonal medication 3 months before hysterectomy. Preparation of tissue samples and subsequent steps were according to the procedures as described previously (Tsibris et al. 2002). Briefly, all patients were Korean. Tissue samples were taken within 20–30 min of extirpation of the uterus and stored in liquid nitrogen. All leiomyomas were selected from intramural and larger than 3 cm in the shortest dimension. Tumor-free myometrium was removed at a distance (2 cm) from the endometrium, unless it was close to another leiomyoma.

Preparation of cDNA microarray

Each gene on the array GeneTrack Human cDNA Chip HSVC 307 provided by Genomictree, Inc., Seoul, Korea (http://www.genomictree.com) is about 0.5–5 kb cDNA and includes control house-keeping gene such as GAPDH, β-actin and α-tubulin. Preparation of cDNA and subsequent steps leading to hybridization, scanning and data analysis were according to BioRobotics guidelines (BioRobotics, Cambridge, UK). As a common type I experiment, where two samples are directly compared on a single array, a total of 100 µg of total RNA was labelled and hybridized to 17 k human microarrays. In brief, fluorescently labelled cDNA was obtained from a single round of labelling using a kit in the presence of fluorescent dNTP (Cy3-dUTP or Cy5-dUTP, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK). Probes and targets were hybridized together for 16 h in 3× standard saline citrate buffer (SSC) at 65 °C. Hybridized slides were washed at room temperature once in 0.5× SSC, 0.01% SDS for 5 min and again in 0.06× SSC for 5 min. Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence were scanned using a laser confocal microscope, and images were analysed using imagene software (version 5.0; BioDiscovery, Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA) to calibrate relative ratios and confidence intervals used for significance determinations. In a type II experiment (DeRisi et al. 1997; Eisen & Brown 1999), a common reference RNA (Genomictree, Inc.) was employed. Thus, the relative difference of gene expression could be measured to a fixed reference. The two assays have the same hybridization procedure.

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using Tri-reagent and used as templates. Reverse transcription was performed at 22 °C for 10 min and then at 42 °C for 20 min using 1.0 µg of RNA per reaction. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed under 35 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, at 57 °C for 1 min and at 72 °C for 1 min using specific primers to obtain the PCR products. Specific primers (forward: 5′-TGACGGGGTCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTA-3′; reverse: 5′-CTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGACGGATGGAGGG-3′) were used for control gene β-actin. The amplification reaction involved denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s and annealing at 72 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 45 s for 20 cycles.

Analysis

Fluorescence intensity was processed and then the data were imported into an Access database (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), with the corresponding gene names for analysis. For each gene, its relative fold change in expression was the ratio of median expression levels of sample vs. myometrium. Genes were excluded from the analyses if their expression was negative or too smeared. Genes that showed differences in their expression levels of at least 2.0 were selected for functional analysis. Hierarchical clustering (gene cluster v2.11) and display programs (tree view v1.50) were also used for analysis (http://www.rana.stanford. edu/software) (Eisen et al. 1998). To classify the gene-expression profiles, functional analyses were carried out as previously described (Pletcher et al. 2002). Each gene was annotated by integrating the information (as of July 2003) on the Gene Ontology website (http://www.geneontology.org). Next, the gene was queried for available Gene Ontology Code for biological process, cellular component and molecular function.

Two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis

To lyse the tissues, isoelectric focusing (IEF) sample buffer [7 m urea, 2 m thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 100 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) and 40 mm Tris] was added to tissues, followed by thorough mixing. After centrifugation, the supernatants were stored at −70 °C until used for two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis. Protein concentration was determined with protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The first dimension on two-dimensional gel electrophoresis consisted of isoelectrical focusing on an ReadyStrip IPG Strip (17 cm, pH 5–7) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Towards this aim, a solution of 30 µl of total protein was applied to this strip that had been treated with the rehydration buffer [7 m urea, 2 m thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 40 mm Tris, 100 mm DTT, 0.5% (v/v) carrier ampholyte (pH 3–10) and 0.005% bromophenol blue]. The gels were focused for 20 h at 50 V, followed by 5 h at 10 000 V and 20 °C. The strips were placed in equilibration buffer I [6 m urea, 0.375 m Tris (pH 8.8), 2% SDS, 20% (v/v) glycerol and 2% DTT] for 20 min and next in buffer II [6 m urea, 0.375 m Tris (pH 8.8), 2% SDS, 20% (v/v) glycerol and 2.5% (w/v) iodoacetamide] for 20 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the isoelectric focusing gels were placed onto SDS–PAGE sheets (ExcelGel XL SDS 12–14; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and the proteins were then resolved in the second dimension with a constant current of 10 mA at 15 °C until the bromophenol blue marker entered the gel sheets, followed by a second period of 15 mA for 16 h. The gels were fixed in a fixative enhancer solution (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid and 10% fixative enhancer concentration) solution and then silver stained as described in manual (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Silver-stained gels were scanned using a scanner (GS-800, Bio-Rad Laboratories). Gel images were analysed using pdquest 2d software, version 7.1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Mass spectrometric analysis of tryptic peptides

The protein spots of interest were excised, destained in 25 mm NH4HCO3 buffer (pH 8.0, 50% acetonitrile) and cleaned in a 100% acetonitrile solution for 5 min. After complete drying, the samples were digested with 15 µl of digestion solution (10 µg/ml of trypsin in 25 mm NH4HCO3, pH 8.0) at 37 °C for 20 h in 20 ml. The tryptic peptides were extracted with extraction solution [50% acetonitrile and 5% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)] and concentrated by drying under vacuum conditions. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) tandem mass spectrometric analysis was performed in a Voyager DE-STR mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The accurately measured masses of the tryptic peptide and its fragments were used to search for protein candidates in the protein sequence database using the program mascot (http://www.matrixscience.com). To classify the protein-expression profiles, functional analyses were carried out as described above. All of the files including results of the experiment and results of the gene ontology analysis are obtainable from our anonymous FTP site (ftp://160.1.9.32/work/myoma2d).

Results

Microarray analysis of leiomyoma-associated gene expression

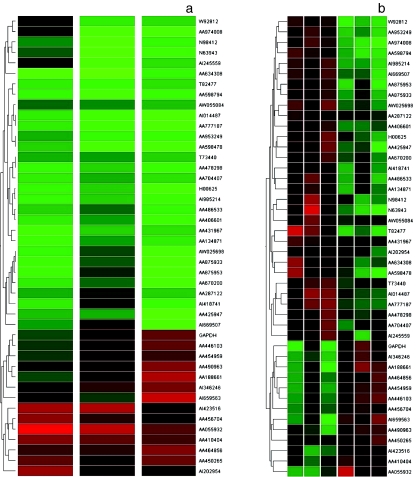

To understand the cellular process changes in the biology of leiomyomas, we profiled differentially expressed genes in three-paired leiomyoma and normal myometrium by type I and type II cDNA microarray assays. After hybridization and scanning steps, poor spots were excluded by image analysis. By the hierarchical clustering, 71 overlapped transcripts were identified at least twofold in three specimens. In contrast, the rest of transcripts within twofold change were not used. As shown in Figure 1, after the cDNA microarray analysis, the consistently expressed 44 transcripts were identified by hierarchical clustering. It shows a good consistency of experimental repeatability. In Table 1, the consistently expressed genes between type I and type II are shown. And, as shown in Figure 2, reverse-transcriptase (RT)-PCR was performed to confirm gene-expression patterns. Several upregulated and downregulated genes confirmed the patterns obtained from the microarray, showing the consistency of experimental repeatability. It is clear that the consistency of experimental repeatability leads to reliable gene-expression patterns in this study. As shown in Table 2, the significantly upregulated and downregulated functional activities were analysed according to the biological processes, cellular components and molecular function ontologies. Of the leiomyoma-associated functional activities, over 50% of the functions were included in the biological processes, with half of these being in the cell growth and maintenance.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of uterine leiomyoma. (a) Type I assay: All the data were median centred and clustered using a hierarchical clustering. Levels of intensity of red squares correlate with the degree of gene expression; conversely, green squares compare the down-expression at a scale relative to the colour intensity. A cluster image representing 44 of the cDNAs is shown. (b) Type II assay (differential expression between uterine leiomyoma and normal myometrium): Type II analysis was used to identify the genes differentially expressed in the uterine leiomyoma by universal control cell lines, selecting 44 genes. Those genes showing statistically significant differences between the two groups are shown as a cluster image. The dendrogram indicates uterine leiomyoma in red and normal myometrium in green. The normal myometrims cluster together, as do the leiomyoma. The column on the left of the two-dimensional view indicates downregulated genes in myometrium in green and upregulated in red; conversely, the column on the right indicates downregulated genes in leiomyoma in green and upregulated in red.

Table 1.

Summary of gene-expression changes in uterine leiomyoma

| Accession number | Description | Gene symbol | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| R77948 | JM27 protein | GAGEC1 | 10.44 |

| N66104 | Kinesin family member 5C | KIF5C | 6.24 |

| AA055932 | PCAF-associated factor 65 beta | TAF5L | 4.56 |

| AA620421 | Double cortex; lissencephaly, X-linked (double cortin) | DCX | 4.26 |

| AI341604 | 37 kDa leucine-rich repeat protein | P37NB | 3.42 |

| AI952615 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21, Cip1) | CDKN1A | 3.24 |

| AI680557 | Collagen, type IV, alpha 6 | COL4A6 | 3.18 |

| AA171613 | Carbonic anhydrase XII | CA12 | 3.06 |

| AA776176 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor, alpha 1 | GABRA1 | 2.99 |

| AA034213 | Integral membrane protein 2C | ITM2C | 2.98 |

| AA670279 | Collapsin response mediator protein 1 | CRMP1 | 2.95 |

| AA430540 | Collagen, type IV, alpha 2 | COL4A2 | 2.83 |

| AA455365 | Phosphodiesterase 8B | PDE8B | 2.77 |

| AA410404 | Damage-specific DNA-binding protein 2 (48 kDa) | DDB2 | 2.53 |

| AA464856 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 4, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein | ID4 | 2.38 |

| T50121 | Kreisler (mouse) maf-related leucine zip | MAFB | 2.26 |

| AA480876 | TATA-binding protein-binding protein | ABT1 | 2.26 |

| AA446017 | Suppression of tumorigenicity 5 | ST5 | 2.17 |

| N54596 | Insulin-like growth factor 2 (somatomedin A) | IGF2 | 2.15 |

| AA913306 | Endometrial bleeding-associated factor (left–right determination, factor A) | EBAF | 1.73 |

| AA504137 | Homeodomain only protein | LAGY | 1.7 |

| W72748 | Guanylate-binding protein 2, interferon-inducible | GBP2 | −1.41 |

| T64192 | T-cell receptor beta locus | TRB@ | −1.58 |

| AA447978 | Retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 | ALDH1A2 | −1.72 |

| AA931725 | Secreted modular calcium-binding protein | SMOC2 | −1.91 |

| AA411380 | Ecotropic viral integration site 2A | EVI2A | −2.24 |

| R40946 | Crystallin, zeta (quinone reductase) | CRYZ | −2.32 |

| AA975768 | Epithelial membrane protein 1 | EMP1 | −2.35 |

| AA055440 | Sprouty (Drosophila) homologue 1 (antagonist of FGF signalling) | SPRY1 | −2.36 |

| AW055084 | MD-2 protein | LY96 | −2.36 |

| AI361583 | Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily, member 1 | KCNF1 | −2.37 |

| T73440 | Alanyl (membrane) aminopeptidase (aminopeptidase N, CD13, p150) | ANPEP | −2.43 |

| AI949576 | Annexin A3 | ANXA3 | −2.62 |

| AA866054 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 9 | BCL9 | −2.73 |

| R39221 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 10 | MAPK10 | −2.76 |

| AA999901 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein 11 | GNG11 | −2.77 |

| W32272 | IQ motif containing GTPase-activating protein 2 | IQGAP2 | −2.83 |

| AA704407 | Lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan | XLKD1 | −2.94 |

| AA149095 | Dual specificity phosphatase 1 | DUSP1 | −2.95 |

| T61428 | Enhancer of filamentation 1 | HEF1 | −3.04 |

| T62627 | Interferon-induced protein 41, 30 kDa | SP110 | −3.07 |

| AA134871 | Fibulin 1 | FBLN1 | −3.13 |

| AA431967 | Thioredoxin | LATS2 | −3.24 |

| AA454868 | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-like | PDGFRL | −3.25 |

| AA478298 | Adipose specific 2 | APM2 | −3.26 |

| AA406601 | Actin-binding LIM protein | ABLIM1 | −3.42 |

| AI869845 | Phosphorylase, glycogen; liver (Hers' disease, glycogen storage disease type VI) | PYGL | −3.43 |

| T82477 | Duffy blood group | FY | −3.45 |

| AA459293 | Mob protein | MOB | −3.46 |

| AI268937 | Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 8 | CCL8 | −3.54 |

| AA427924 | Spondin 1 (f-spondin) extracellular matrix protein | SPON1 | −3.63 |

| AA953249 | H factor 1 (complement) | HF1 | −3.82 |

| AA486275 | Serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin) | SERPINB1 | −3.84 |

| H00625 | GATA-binding protein 2 | MGC2306 | −3.87 |

| AA757351 | Calcitonin receptor-like | CALCRL | −3.88 |

| AI922341 | Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 21 | CCL21 | −3.94 |

| W58032 | Frizzled-related protein | FRZB | −4.16 |

| AA598794 | Connective tissue growth factor | CTGF | −4.24 |

| AA425947 | Dickkopf gene 3 | RIG | −4.27 |

| AI676097 | Fc fragment of IgE, high affinity I, receptor for alpha polypeptide | FCER1A | −4.51 |

| H63077 | Annexin A1 | ANXA1 | −4.82 |

| AA598478 | Complement component 7 | C7 | −4.82 |

| AA777187 | Cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer, 61 | CYR61 | −4.91 |

| W69211 | Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 11 | CCL11 | −5.61 |

| AA481780 | Carbonic anhydrase III, muscle specific | CA3 | −5.87 |

| AA457084 | Apolipoprotein D | APOD | −7.84 |

| N32201 | Osteomodulin | OMD | −8.41 |

| AI420743 | Alcohol dehydrogenase 3 (class I), gamma | ADH1C | −10.03 |

| R48303 | Dermatopontin | DPT | −10.97 |

| AA664101 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1, member A1 | ALDH1A1 | −12.37 |

| N93428 | Alcohol dehydrogenase 2 (class I), beta | ADH1B | −18.57 |

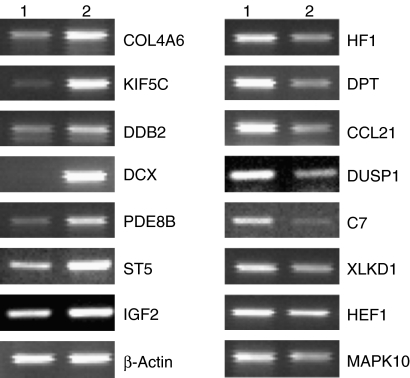

Figure 2.

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of selected genes confirmed differential expression of cDNA microarray. Total RNA obtained from normal myometrium (lane 1) and leiomyoma (lane 2) was subjected to RT-PCR assays as described in Materials and methods.

Table 2.

Summarized gene ontology of cDNA microarray

| Biological process | Molecular function | Cellular component |

|---|---|---|

| Cell communication (6/16)* | Binding activity (13/25) | Cytoskeleton (2/3) |

| Cell adhesion (1/6) | Hormone-binding activity (0/1) | Actin cytoskeleton (0/2) |

| Cell–cell signalling (2/3) crotubule-associated complex (2/0) | Lipid-binding activity (0/3) | |

| Signal transduction (5/12) | Metal ion-binding activity (3/8) | Spindle (0/1) |

| Cell death (1/2) | Calcium ion-binding activity (0/4) | Plasma membrane (0/6) |

| Cytolysis (0/1) | Nucleic acid-binding activity (4/2) | Extracellular matrix (2/4) |

| Induction of apoptosis by intracellular signals (1/0) | DNA-binding activity (2/2) | Basement membrane (2/0) |

| Cell growth and maintenance (4/14) | Nucleotide-binding activity (1/4) | Collagen (2/0) |

| Regulation of cell growth (0/3) | Protein-binding activity (4/7) | Membrane attack complex (0/1) |

| Cell homeostasis (0/1) | Cytoskeletal protein-binding activity (1/0) | |

| Cell organization and biogenesis (2/3) | Insulin-like growth factor-binding activity (0/2) | |

| Cell proliferation (2/5) | Immunoglobulin-binding activity (0/1) | |

| Cell cycle (1/1) | Receptor-binding activity (4/4) | |

| Transport (1/3) | Defence/immunity protein activity (0/3) | |

| Protein transport (0/1) | Enzyme activity (4/15) | |

| Cell motility (0/6) | MAP kinase activity (0/1) | |

| Chemotaxis (0/3) | JUN kinase activity (0/1) | |

| Morphogenesis (5/6) | MAP kinase kinase activity (0/1) | |

| Organogenesis (5/6) | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor activity (0/1) | |

| Epidermal differentiation (0/2) | Oxidoreductase activity (0/5) | |

| Neurogenesis (3/0) | Transferase activity (1/4) | |

| Skeletal development (1/1) | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity (0/2) | |

| Homeostasis (1/2) | Enzyme regulator activity (1/4) | |

| Metabolism (7/17) | Cyclin-dependent protein kinase inhibitor activity (1/0) | |

| Lipid metabolism (0/2) | Serine protease inhibitor activity (0/1) | |

| Nucleobase and nucleic acid metabolism (6/3) | Extracellular matrix structural constituent activity (2/1) | |

| DNA repair (1/0) | ||

| Transcription (2/2) | ||

| Protein metabolism (0/6) | ||

| Proteolysis and peptidolysis (0/1) | ||

| Response to external stimulus (0/14) | ||

| Immune response (0/10) | ||

| Response to oxidative stress (0/1) | ||

| Cellular defence response (0/2) | ||

| Inflammatory response (0/5) |

The number of upregulated genes vs. downregulated genes.

Cell communication

As shown in Table 2, the transcripts involved in the cell communication (6/16, i.e. upregulation of six transcripts or the downregulation of 16 transcripts) were relatively downregulated in the uterine leiomyoma as compared with the myometrium. Cell adhesion function (1/6: COL4A6/DPT, OMD, CCL11, CTGF, HEF1 and XLKD1) was repressed by leiomyoma pathophysiology. For instance, dermatopontin (DPT) and eotaxin (CCL11), cell-to-cell attachment-related components, were highly downregulated, indicating a decrease in the adhesive properties of leiomyoma pathogenesis. Transcripts in signal transduction (5/12: DCX, GABRA1, PDE8B, IGF2, EBAF/CCL11, ANXA1, CCL21, CALCRL, CCL8, FY, HEF1, IQGAP2, GNG11, MAPK10, LY96 and SPRY1) showed relatively repressed expression profiles. Cell–cell signalling function (2/3: GABRA1, EBAF/CCL11, CCL21 and CCL8) was repressed by leiomyoma-associated cellular pathway.

Cell growth and maintenance

Transcripts involved in cell growth and maintenance (4/14) were repressed. Especially, all transcripts in the regulation of cell growth (0/3: CYR61, CTGF and HEF1) were completely downregulated. Transcripts involved in cell proliferation (2/5: IGF2, CDKN1A/CYR61, EMP1, EVI2A, DUSP1 and HEF1) were also repressed in leiomyomas. Transcripts involved in transport (1/3: GABRA1/APOD, KCNF1 and CCL8) and cell organization and biogenesis (2/3: IGF2, KIF5C/CCL11, ABLIM1 and IQGAP2) were relatively downregulated.

Cell motility

All transcripts in cell motility including chemotaxis (0/6: ANXA1, CTGF, XLKD1, CCL11, CCL21 and CCL8) were completely downregulated.

Development

Several transcripts involved in morphogenesis (4/6: IGF2, CRMP1, DCX, MAFB/CCL11, IQGAP2, CTGF, EMP1, SPRY1 and FRZB) were relatively balanced, in which neurogenesis in organogenesis (3/0: CRMP1, DCX and MAFB) was completely upregulated in leiomyoma pathophysiology. In contrast, epidermal differentiation (0/2: CTGF and EMP1) was completely downregulated.

Metabolism

Transcripts in metabolism (7/17) were relatively repressed, such that protein metabolism (0/6: CCL11, LATS2, MAPK10, DUSP1, ANPEP and CCL8) and lipid metabolism (0/2: APOD and ANXA1) were completely repressed. In contrast, transcripts involved in nucleic acid metabolism (6/3: CRMP1, PDE8B, DDB2, ID4, MAFB, IGF2/CTGF, MGC2306 and SP110) were relatively upregulated.

Response to external stimulus

All transcripts in response to external stimulus (0/14) were completely downregulated. Especially, immune response (0/10: CCL11, C7, ANXA1, FCER1A, CCL21, HF1, CCL8, LY96, TRB@and GBP2) including inflammatory response (0/5) was significantly downregulated. In addition, response to oxidative stress (0/1: DUSP1), response to virus (0/2: CCL11 and CCL8) and response to wounding (0/1: CTGF) were completely downregulated.

Binding activity

Transcripts involved in binding activity (13/25) were downregulated. Transcripts in lipid-binding activity (0/3: APOD, ANXA1 and ANXA3), metal ion-binding activity (3/8: PDE8B, CRMP1, CA12/ADH1B, ADH1C, CA3, ANXA1, FBLN1, ANXA3, CRYZ and SMOC2), nucleotide-binding activity (1/4: KIF5C/MAPK10, LATS2, GBP2 and GNG11) and protein-binding activity (4/7: DCX, KIF5C, ABT1, ID4/DPT, KCNF1, IQGAP2, CYR61, CTGF, FCER1A and APOD) were significantly downregulated. In contrast, nucleic acid-binding activity (4/2: DDB2, MAFB, TAF5L, ABT1/MGC2306 and SP110) was only upregulated.

Enzyme activity

Transcripts involved in enzyme activity (4/15), hydrolase activity (2/5: PDE8B, CRMP1/DUSP1, GNG11, ANXA3, ANPEP and GBP2), kinase activity (1/3: CDKN1A/LATS2, PDGFRL and MAPK10), oxidoreductase activity (0/5: ADH1B, ALDH1A1, ADH1C, CRYZ and ALDH1A2), enzyme regulator activity (1/4: CDKN1A/SERPINB1, IQGAP2, ANXA1 and ANXA2) and transferase activity (1/4: CDKN1A/PYGL, MAPK10, LATS2 and PDGFRL) were significantly downregulated in leiomyomas.

Signal transducer activity

Transcripts involved in signal transducer activity (4/18), receptor activity (1/9: GABRA1/FCER1A, FY, ANPEP, PDGFRL, XLKD1, TRB@, LY96, FRZB, EVI2A and CALCRL), receptor-binding activity (2/5: EBAF, IGF2/ANXA1, CCL11, CCL21, CCL8 and CTGF) and receptor signalling protein activity (0/4: FCER1A, MAPK10, IQGAP2 and CTGF) were downregulated.

Structural proteins

Transcripts in cytoskeleton (2/3: KIF5C, DCX/ABLIM1, HEF1 and IQGAP2) and extracellular matrix structural constituent (2/1: COL4A2 and COL4A6/OMD) were differentially expressed. Bone-specific osteomodulin (OMD) involved in biomineralization processes was highly down-regulated.

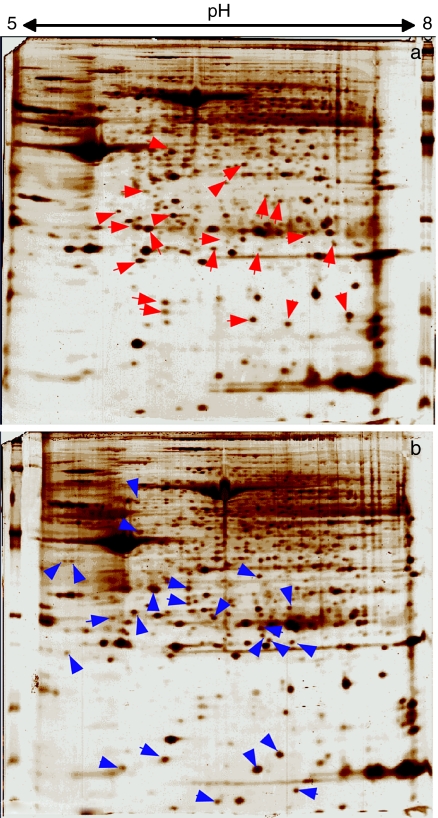

Two-dimensional analysis of leiomyoma-associated protein expression

As shown in Figure 3, lysates prepared from the uterus tissues with and without leiomyoma were subjected to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis to examine the pathogenetic protein expression of uterine leiomyoma. Comparison of the spot patterns of the samples with and without leiomyoma indicated that of more than 500 total spots, the consistently corresponding spots of 33 proteins, were identified: 17 proteins that were upregulated and 16 proteins that were downregulated. These proteins have exhibited detectable quantitative changes. Table 3 summarizes the consistently expressed proteins with their expression profiles. No proteins could be extracted from the corresponding spots on the cDNA microarray due to a small number of the consistently expressed proteins. In order to more systematically study whether the observed protein-expression profilings were leiomyoma specific, the gene ontology analysis was also applied. Table 4 summarizes the functional activities deduced from the gene ontology and the dependency of their expression profiles. The majority of the upregulated functional activities turned out to be nucleic acid-binding activity (3/0: SMARCAL1, PSMB3 and TUFM), signal transducer (3/0: CCL13, IFNA8 and OGN) and transporter activity (3/0: CRABP2, CLIC4 and PRDX5). In contrast, significant downregulation is shown in muscle development (0/5: ACTA1, ACTA2, ACTC, ACTG2 and TAGLN). These proteins were also involved in the downregulation of actin cytoskeleton activity, cytoskeletal protein-binding activity and motor activity. Cell motility activity (0/4: ARPC5, ACTA1, ACTC and CRYAB) was also completely downregulated. Several functional activities such as response to external stimulus (3/4) and extracellular matrix (2/2) remained unchanged, which indicated that these functions were under leiomyoma independent. Further identification of leiomyoma-dependent protein products was found to be difficult, because other candidate spots, containing sufficient amounts of protein for the determination of their masses, could not be separated pure enough from surrounding spots on the two-dimensional gels.

Figure 3.

Uterine leiomyoma protein products on two-dimensional gels. Identification of the proteins in 30 spots, which are indicated by red arrowheads (a, myometrium) and blue arrowheads (b, leiomyoma), is summarized in Table 2. The two-dimensional gel patterns indicated that out of the 30 spots.

Table 3.

Summary of the regulated proteins in uterine leiomyoma

| Accession number | Description | Gene symbol | Sequence coverage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated proteins | |||

| NP_068733 | Cofilin 2 isoform 1 | CFL2 | 27 |

| NP_001606 | Actin, gamma 2 propeptide; actin, alpha-3 | ACTG2 | 18 |

| NP_005150 | Actin, alpha, cardiac muscle precursor | ACTC | 26 |

| NP_001604 | Alpha 2 actin; alpha-cardiac actin | ACTA2 | 23 |

| NP_001091 | Alpha 1 actin precursor; alpha skeletal muscle actin | ACTA1 | 25 |

| AAH12423 | SOD2 protein | SOD2 | 19 |

| NP_001876 | Crystallin, alpha B; heat-shock 20 kDa like-protein | CRYAB | 30 |

| NP_057177 | Ribosomal protein L26-like 1; ribosomal protein L26 homologue | RPL26L1 | 17 |

| NP_004406 | Desmoplakin – DPI and DPII | DSP | 20 |

| AAF64276 | BM-020 | C21orf66 | 18 |

| Q01995 | Transgelin (smooth muscle protein 22-alpha) (SM22-alpha) | TAGLN | 29 |

| NP_005708 | Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 5 | ARPC5 | 27 |

| 1SACA | Chain A, serum amyloid P component (Sap) | APCS | 30 |

| NP_006254 | Proteasome activator subunit 1 isoform 1 | PSME1 | 31 |

| NP_653321 | Hypothetical protein FLJ31564 | FLJ31564 | 15 |

| XP_068995 | Novel protein based on FGENESH similar to ribosomal protein | FAM12A | 16 |

| Upregulated proteins | |||

| NP_002161 | Interferon, alpha 8 | IFNA8 | 11 |

| I51875 | MHC HLA-DRB1 – human (fragment) | HLA-DRB1 | 14 |

| AAH16482 | SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin | SMARCAL1 | 11 |

| AAF04856 | Thioredoxin peroxidase PMP20 | PRDX5 | 21 |

| AAG01157 | CGI-204 | MRPL47 | 13 |

| NP_004823 | Glutathione-S-transferase like | GSTTLp28 | 19 |

| BAB64300 | EREG1 | EREG1 | 14 |

| CAB01111 | C–C chemokine | CCL13 | 19 |

| AAD38446 | H1 chloride channel; p64H1; CLIC4 | CLIC4 | 15 |

| NP_001869 | Cellular retinoic acid-binding protein 2 | CRABP2 | 31 |

| Q9BZE7 | Hypothetical protein EVG1 | C22orf23 | 17 |

| NP_004896 | Peroxiredoxin 6; antioxidant protein 2 | AOP2 | 33 |

| NP_002786 | Proteasome beta 3 subunit; proteasome theta chain | PSMB3 | 17 |

| AAF36151 | HSPC231 | PFDN2 | 18 |

| NP_003312 | Tu translation elongation factor, mitochondrial | TUFM | 32 |

| CAB61417 | Hypothetical protein | OGN | 28 |

| AAH17917 | Triosephosphate isomerase 1 | TPI1 | 31 |

Table 4.

Summarized gene ontology of two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis

| Biological process |

| Cell communication (2/1)* |

| Cell adhesion (0/1) |

| Cell–cell signalling (1/0) |

| Signal transduction (2/0) |

| Cell growth and maintenance (3/0) |

| Cell homeostasis (1/0) |

| Transport (2/0) |

| Cell motility (0/4) |

| Development (1/7) |

| Organogenesis (1/6) |

| Epidermal differentiation (1/1) |

| Muscle development (0/5) |

| Homeostasis (1/0) |

| Metabolism (8/3) |

| Biosynthesis (1/1) |

| Lipid metabolism (2/0) |

| Nucleobase and nucleic acid metabolism (1/1) |

| Oxygen and reactive oxygen species metabolism (3/1) |

| Protein metabolism (3/3) |

| Protein folding (1/2) |

| Pathogenesis (1/1) |

| Response to external stimulus (3/4) |

| Immune response (2/2) |

| Response to oxidative stress (1/1) |

| Molecular function |

| Antioxidant activity (2/0) |

| Binding activity (7/3) |

| Lipid binding activity (1/0) |

| Nucleic acid-binding activity (3/0) |

| DNA-binding activity (1/0) |

| Nucleotide-binding activity (2/0) |

| Protein-binding activity (1/2) |

| Cytoskeletal protein binding activity (0/2) |

| Receptor-binding activity (1/0) |

| Chaperone activity (1/2) |

| Enzyme activity (5/1) |

| Hydrolase activity (3/0) |

| Oxidoreductase activity (2/1) |

| Transferase activity (1/0) |

| Enzyme regulator activity (0/1) |

| Proteasome activator activity (0/1) |

| Motor activity (0/4) |

| Signal transducer activity (3/0) |

| Structural molecule activity (0/8) |

| Structural constituent of cytoskeleton activity (0/6) |

| Structural constituent of muscle activity (0/3) |

| Transporter activity (3/0) |

| Cellular component |

| Cytoskeleton (0/7) |

| Actin cytoskeleton (0/5) |

| Microtubule-associated complex (0/1) |

| Membrane (2/1) |

| Extracellular matrix (2/2) |

The number of upregulated genes vs. downregulated genes.

Discussion

To systematically understand the cellular process changes in leiomyomas, we combined the techniques of cDNA microarray, two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis and the gene ontology analysis. The comparison of cDNA microarray and proteomic analytical results showed large discrepancies between mRNA and protein levels, as discussed previously (Juan et al. 2002). Potential leiomyoma-related genes found through microarray analysis were proven to be relevant at present, because other candidate protein spots, containing higher than 10 or lower than 5 pH values and lower detection limit for the determination of their masses, could be easily excluded in the two-dimensional gel analysis. There is good agreement between our observations and other studies for some of the genes, and this greatly increases the reliability of the results on these genes such as DCX, IGF2, ADH, KIF5C and CDKN1 (Tsibris et al. 2002; Skubitz & Skubitz 2003b). Also, the potentially significant genes of unknown function in bold are summarized in Table 1. Among those genes, upregulated GAGEC1 is a member of the GAGE family. This gene is strongly expressed in prostate and prostate cancer but is also expressed in testicular cancer and uterine cancer (Brinkmann et al. 1998). Also, the protein encoded by LAGY is known to be a lung cancer-associated protein. Future studies should be required to clarify the regulatory mechanism of the genes and their role in uterine leiomyoma development. Closer examination of the transcriptomes and proteoms using the gene ontology resulted in a number of reciprocally dependent cellular processes, which reveals that several corresponding functional activities were found to be pathogenesis related. Especially, several functions that were downregulated in leiomyoma, such as structural molecule and extracellular matrix adhesion molecules, are in agreement with the observations (Chegini et al. 2003). Of the corresponding functions, downregulated functions were more abundant than those in upregulation, indicating that repression of cellular process may have a significant impact on uterine leiomyoma pathogenesis.

The downregulated cell adhesion activity indicates a decrease in the adhesive properties in leiomyoma. For instance, downregulated eotaxin (CCL11), a potent inducer of eosinophil chemotaxis leading to eosinophil migration in vitro and accumulation in vivo, is not able to take part in the fine-tuning of cellular responses occurring at sites of allergic inflammation, where both monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP1) and eotaxin are to be produced (Ogilvie et al. 2001). In transgenic mice that overexpressed CTGF, embryonic and neonatal growth were reported to be occurred normally, which indicates that downregulated CTGF in this study may hinder the embryonic development (Nakanishi et al. 2001). In contrast, overexpressed type IV collagen alpha 6 (COL4A6), the major component of basement membranes, was only used in generating unique basement membrane structures in different tissues (Sugimoto et al. 1994).

Of the completely downregulated cell motility function, ANXA1 was reported to act through the formyl peptide receptor on human neutrophils (Walther et al. 2000). Peptides derived from the unique N-terminal domain of ANXA1 serve as FPR ligands and trigger different signalling pathways. By downregulation of ANXA1, lower peptide concentrations may cause a specific inhibition of the transendothelial migration of neutrophils and desensitization of neutrophils towards a chemoattractant challenge, leading to loss of anti-inflammatory effects. XLKD1 appears to be involved in the sequestration or transport of hyaluronan, an abundant extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycan in skin and mesenchymal tissues, where it facilitates cell migration during wound healing, inflammation and embryonic morphogenesis. In this study, XLKD1 was downregulated, which leads to loss of anti-inflammatory effects (Banerji et al. 1999).

It was reported that gynaecological disease could be induced by abnormal immunogenetic changes of genes involved in tissue regeneration, such as matrix metalloproteinase, cytokines and growth factors (Hill 1992). Of the response to external stimulus function, significantly downregulated transcripts serve as an important hinderer in immune response in the following manner. The eosinophil-specific chemokine (CCL11) and IgE receptor (FCER1A) are known to be involved in eosinophilic inflammatory diseases such as atopic dermatitis, asthma and parasitic infections (Salcedo et al. 2001; Zhu et al. 2002). C7 is a component of the complement system. People with downregulation of C7 are prone to recurrent bacterial infections (Egan et al. 1994). Similar to other chemokines, the protein encoded by CCL21 inhibits haemopoiesis and stimulates chemotaxis. This protein is chemotactic in vitro for thymocytes and activated T cells but not for B cells, macrophages or neutrophils. The cytokines encoded by CCL21 may also play a role in mediating homing of lymphocytes to secondary lymphoid organs (Ploix et al. 2001). CCL8 displays chemotactic activity for monocytes, lymphocytes, basophils and eosinophils. By recruiting leucocytes to sites of inflammation, this cytokine may contribute to tumour-associated leucocyte infiltration (Van et al. 1997).

Transcription is a complex category that can lead to global alterations in the whole network of gene expressions. These transcriptional regulators are expected to be highly relevant to the leiomyoma pathophysiology, and their regulation may affect different cellular functions. For instance, upregulated TAF5L, expressed in most tissues, functions in promoter recognition or modifies general transcription factors to facilitate complex assembly and transcription initiation. And, it inactivates platelet-activating factor by removing the acetyl group at the SN2 position. Its aberrant overexpression may serve to repress other downstream pathways that further contribute to the development of the disease. On the other hand, transcriptional activators MGC2306 and SP110 that regulate endothelin-1 gene expression in endothelial cells were repressed. In this study, no transcripts in protein translation or biosynthesis function were expressed. Thus, it can be suggested that leiomyoma may not increase the turnover of many proteins, which could be due either to the less activity of replacement of damaged molecules or to the nature of benign tumour itself, as compared with leiomyosarcoma (Skubitz & Skubitz 2003a).

Several transcripts coding for cellular structure proteins were changed in their expression in the uterine leiomyoma. Transcripts in this category can be subdivided into two groups: cytoskeletal and nuclear-related genes. It has been known that cytoskeleton integrity plays an important role in cell-cycle progression, cell death and cell differentiation (Liu et al. 2002). Abnormal cytoskeleton function is often observed in cancer cells. Notably, HEF1, highly expressed in normal endometrium in uterus, was downregulated in this study. It is an important component of a cytoskeleton-linked signalling pathway initiated by integrins (Manie et al. 1997). Transformation of cells with the oncogene Abl results in tyrosine phosphorylation of HEF1 that is mediated by a direct association between HEF1 and Abl, speculating that HEF1 may be an important linking element between extracellular signalling and regulation of the cytoskeleton (Law et al. 1996). Also, ABLIM1, highly expressed in ovary bulk tumour, was also downregulated. It plays key roles in the regulation of developmental pathways (Roof et al. 1997).

A literature survey revealed that several transcripts have been reported to be leiomyoma related with regard to the transcripts themselves or the products containing them as constituents. Among them, IGF2 was reported to be overexpressed in leiomyoma development, as consistent with this study (Li & McLachlan 2001; Tsibris et al. 2002). Recurrent hypoglycaemia in a woman with leiomyosarcoma was known to be through the result of overexpression of IGF2 by the tumour (Daughaday et al. 1988). Also, it was reported that CYR61 and CTGF have significant sequence homology to the insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins and contain a von Willebrand factor type C repeat, which is thought to be involved in the deactivation of a genetic programme for wound repair in skin fibroblasts via reduction of CYP61 (Chen et al. 2001).

In conclusion, we identified gene-expression changes and differentially expressed proteins in uterine leiomyoma. Also, potentially significant pathogenetic cellular processes were identified using the gene ontology analysis. Our most interesting finding was that the gene ontology analysis can describe the cellular processes that occur in the biology of uterine leiomyoma and overcome the complexity of expression profiles. Therefore, a valuable prognostic candidate gene with real relevance to disease-specific pathogenesis can be found at cellular process levels. Further systematic approaches, including genome-wide analyses using the gene ontology, can certainly elucidate new connections between transcriptome and proteome expression profiles.

References

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji S, Ni J, Wang SX, et al. LYVE-1, a new homologue of the CD44 glycoprotein, is a lymph-specific receptor for hyaluronan. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:789–801. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann U, Vasmatzis G, Lee B, Yerushalmi N, Essand M, Pastan I. PAGE-1, an X chromosome-linked GAGE-like gene that is expressed in normal and neoplastic prostate, testis, and uterus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:10757–10762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttram VC, Reiter RC. Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertil. Steril. 1981;36:433–445. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)45789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chegini N, Verala J, Luo X, Xu J, Williams RS. Gene expression profile of leiomyoma and myometrium and the effect of gonadotropin releasing hormone analogue therapy. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2003;10:161–171. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(03)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Mo FE, Lau LF. The angiogenic factor Cyr61 activates a genetic program for wound healing in human skin fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47329–47337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughaday WH, Emanuele MA, Brooks MH, Barbato AL, Kapadia M, Rotwein P. Synthesis and secretion of insulin-like growth factor II by a leiomyosarcoma with associated hypoglycemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;319:1434–1440. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812013192202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRisi JL, Iyer VR, Brown PO. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science. 1997;278:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doniger SW, Salomonis N, Dahlquist KD, Vranizan K, Lawlor SC, Conklin BR. MAPPFinder: using gene ontology and GenMAPP to create a global gene-expression profile from microarray data. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R7–R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan LJ, Orren A, Doherty J, Wurzner R, McCarthy CF. Hereditary deficiency of the seventh component of complement and recurrent meningococcal infection: investigations of an Irish family using a novel haemolytic screening assay for complement activity and C7 M/N allotyping. Epidemiol. Infect. 1994;113:275–281. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Brown PO. DNA arrays for analysis of gene expression. Methods Enzymol. 1999;303:179–205. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)03014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JA. Immunology and endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1992;58:262–264. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan HF, Lin JY, Chang WH, et al. Biomic study of human myeloid leukemia cells' differentiation to macrophages using DNA array, proteomic, and bioinformatic analytical methods. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:2490–2504. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200208)23:15<2490::AID-ELPS2490>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law SF, Estojak J, Wang B, Mysliwiec T, Kruh G, Golemis EA. Human enhancer of filamentation 1, a novel p130 (cas)-like docking protein, associates with focal adhesion kinase and induces pseudohyphal growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:3327–3337. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, McLachlan JA. Estrogen-associated genes in uterine leiomyoma. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;D948:112–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon AH, Morton CC. Leiomyomata: heritability and cytogenetic studies. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2001;7:8–14. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YG, Gano J, Huang R, Lin Y, Wang SM, Huang RP. Analysis of gene expression in Egr-1 transfected human fibrosarcoma cells. J. Surg. Oncol. 2002;80:190–196. doi: 10.1002/jso.10126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manie SN, Beck AR, Astier A, et al. Involvement of p130-Cas and p105-HEF1, a novel Cas-like docking protein, in a cytoskeleton-dependent signaling pathway initiated by ligation of integrin or antigen receptor on human B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4230–4236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeeby JL, Li X, Zhuang Z, et al. Multiple leiomyomas of the esophagus, lung, and uterus in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;159:1121–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61788-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi T, Yamaai T, Asano M, et al. Overexpression of connective tissue growth factor/hypertrophic chondrocyte-specific gene product 24 decreases bone density in adult mice and induces dwarfism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;281:678–681. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie P, Bardi G, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Uguccioni M. Eotaxin is a natural antagonist for CCR2 and an agonist for CCR5. Blood. 2001;97:1920–1924. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.7.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher SD, MacDonald SJ, Marguerie R, et al. Genome-wide transcript profiles in aging and calorically restricted Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:712–723. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploix C, Lo D, Carson MJ. A ligand for the chemokine receptor CCR7 can influence the homeostatic proliferation of CD4 T cells and progression of autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2001;167:6724–6730. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roof DJ, Hayes A, Adamian M, Chishti AH, Li T. Molecular characterization of abLIM, a novel actin-binding and double zinc finger protein. J. Cell. Biol. 1997;138:575–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo R, Young HA, Ponce ML, et al. Eotaxin (CCL11) induces in vivo angiogenic responses by human CCR3+ endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 2001;166:7571–7578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skubitz KM, Skubitz AP. Differential gene expression in leiomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2003a;98:1029–1038. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skubitz KM, Skubitz AP. Differential gene expression in uterine leiomyoma. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2003b;141:297–308. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2143(03)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto M, Oohashi T, Ninomiya Y. The genes COL4A5 and COL4A6, coding for basement membrane collagen chains alpha-5(IV) and alpha-6(IV) are located head-to-head in close proximity on human chromosome Xq22 and COL4A6 is transcribed from two alternative promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:11679–11683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsibris JC, Segars J, Coppola D, et al. Insights from gene arrays on the development and growth regulation of uterine leiomyomata. Fertil. Steril. 2002;78:114–121. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Coillie E, Fiten P, Nomiyama H, et al. The human MCP-2 gene (SCYA8): cloning, sequence analysis, tissue expression, and assignment to the CC chemokine gene contig on chromosome 17q11.2. Genomics. 1997;40:323–331. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu K, Greenspan DL, Wu TC, Zacur HA, Kurman RJ. Cellular proliferation, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and bcl-2 expression in GnRH agonist-treated uterine leiomyomas. Hum. Pathol. 1998;29:359–363. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther A, Riehemann K, Gerke V. A novel ligand of the formyl peptide receptor: annexin I regulates neutrophil extravasation by interacting with the FPR. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:831–840. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D, Kepley CL, Zhang M, Zhang K, Saxon A. A novel human immunoglobulin Fc-gamma-Fc-epsilon bifunctional fusion protein inhibits Fc-epsilon-RI-mediated degranulation. Nat. Med. 2002;8:518–521. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]