Abstract

Memory processes can be enhanced by reward, and social signals such a smiling face can be rewarding to humans. Using event-related functional MRI (fMRI), we investigated the rewarding effect of a simple smile during the encoding and retrieval of face-name associations. During encoding, participants viewed smiling or neutral faces, each paired with a name, and during retrieval, only names were presented, and participants retrieved the associated facial expressions. Successful memory activity of face-name associations was identified by comparing remembered vs. forgotten trials during both encoding and retrieval, and the effect of a smile was identified by comparing successful memory trials for smiling vs. neutral faces. The study yielded three main findings. First, behavioral results showed that the retrieval of face-name associations was more accurate and faster for smiling than neutral faces. Second, the orbitofrontal cortex and the hippocampus showed successful encoding and retrieval activations, which were greater for smiling than neutral faces. Third, functional connectivity between the orbitofrontal cortex and the hippocampus during successful encoding and retrieval was stronger for smiling than neutral faces. As a part of reward system, the orbitofrontal cortex may modulate memory processes of face-name associations mediated by the hippocampus. Interestingly, the effect of a smile during retrieval was found even though only names were presented as retrieval cues, suggesting that the effect was mediated by face imagery. Taken together, the results demonstrate how rewarding social signals from a smiling face can enhance relational memory for face-name associations.

Keywords: fMRI, medial temporal lobe, medial prefrontal lobe, associative memory, facial expression, happy

1. Introduction

Memory processes can be enhanced by reward, and social signals such as a smiling face can be rewarding to humans. A smiling face makes people appear more trustworthy (Winston, Strange, O’Doherty, & Dolan, 2002) and familiar (Baudouin, Gilibert, Sansone, & Tiberghien, 2000), as well as more attractive and kind (Otta, Folladore Abrosio, & Hoshino, 1996). Happy expressions are also identified more easily than other expressions (Kaufmann & Schweinberger, 2004; Leppanen & Hietanen, 2004), and smiling faces are remembered better than surprised, angry or fearful faces (Shimamura, Ross, & Bennett, 2006). An intriguing possibility is that the enhancing effect of a smile on memory for faces reflects an effect of brain regions associated with reward, such as the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), on brain regions associated with memory, such as the medial temporal lobes (MTL: hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus). The current functional MRI (fMRI) study investigated this hypothesis.

The important role of OFC in reward processing has been demonstrated by cognitive neuroscience studies with animals and humans (for review, see Martin-Soelch et al., 2001; McClure, York, & Montague, 2004; O’Doherty, 2004; Rolls, 2000). For example, single unit recording studies with non-human primates have shown that OFC contributes to the coding of the reward value of stimuli (Critchley & Rolls, 1996; Rolls, Sienkiewicz, & Yaxley, 1989). In addition, functional neuroimaging studies have shown that OFC activity is associated with coding reward from a variety of sensory modalities, including taste, olfaction, somatosensory, auditory and vision as well as more abstract reward such as money (for review, see O’Doherty, 2004). For example, one study found greater OFC activity when participants viewed beautiful than ugly paintings, regardless of the category of the painting (Kawabata & Zeki, 2004). Thus, these previous studies suggest that the OFC regions are involved in evaluating the reward value of stimuli, and this evaluation may be independent of the stimulus modality or abstractness.

The role of OFC in processing reward may explain why this region is involved in processing happy facial expressions and other social signals conveyed by faces (Aharon et al., 2001; O’Doherty et al., 2003). For example, functional neuroimaging studies have linked OFC activity to the processing of smiling (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2001) and attractive (Ishai, 2007; Kranz & Ishai, 2006; O’Doherty et al., 2003; Winston, O’Doherty, Kilner, Perrett, & Dolan, 2007) faces, and to the processing of face preference decisions (Kim, Adolphs, O’Doherty, & Shimojo, 2007). Neuropsychological studies have reported that patients with OFC lesions are impaired in their ability to process facial expressions (Blair & Cipolotti, 2000; Hornak et al., 2003; Hornak, Rolls, & Wade, 1996). Thus, there is substantial evidence linking OFC to processing reward and, perhaps for this reason, to processing rewarding social signals conveyed by faces, including happy expressions. Although previous functional neuroimaging studies have investigated the role of the amygdala on emotional facial expression (Breiter et al., 1996; Keightley, Chiew, Winocur, & Grady, 2007; Morris et al., 1996; Phillips et al., 1998; Winston, O’Doherty, & Dolan, 2003) or emotional memory (Dolcos, LaBar, & Cabeza, 2004; Dolcos, LaBar, & Cabeza, 2005; Smith, Stephan, Rugg, & Dolan, 2006), no functional neuroimaging study has investigated the role of OFC on enhanced memory for happy faces.

Functional neuroimaging studies have shown that MTL regions are involved in memory encoding and retrieval of a variety of stimuli, including faces (for review, see Cabeza & Nyberg, 2000; Davachi, 2006; Henson, 2005; Rapcsak, 2003). Certain MTL regions, such as the hippocampus, have been associated with the successful encoding and retrieval of associations between different items, or relational memory (Achim & Lepage, 2005; Bunge, Burrows, & Wagner, 2004; Duzel et al., 2003; Giovanello, Schnyer, & Verfaellie, 2004; Jackson & Schacter, 2004; Meltzer & Constable, 2005; Prince, Daselaar, & Cabeza, 2005; Prince, Tsukiura, & Cabeza, 2007; Ranganath, Cohen, Dam, & D’Esposito, 2004; Yonelinas, Hopfinger, Buonocore, Kroll, & Baynes, 2001). Moreover, there is evidence that the hippocampus is involved in encoding (Chua, Schacter, Rand-Giovannetti, & Sperling, 2007; Sperling et al., 2001; Sperling et al., 2003), retrieval (Paller et al., 2003; Tsukiura, Suzuki, Shigemune, & Mochizuki-Kawai, 2007) and both encoding and retrieval (Kirwan & Stark, 2004; Small et al., 2001; Zeineh, Engel, Thompson, & Bookheimer, 2003) of face-name associations. Yet, no functional neuroimaging evidence is available regarding the effects of smiling facial expressions on relational memory for face-name associations.

The foregoing findings suggest that the reason why happy faces are remembered better than neutral faces is because of reward signals processed by OFC influencing successful memory processes in MTL. However, direct evidence for this hypothesis is scarce. Anatomical studies have demonstrated the existence of connection between OFC and MTL (Barbas & Blatt, 1995; Carmichael & Price, 1995; Lavenex, Suzuki, & Amaral, 2002), supporting the idea that the OFC-MTL interaction could contribute to the long-term memory processing in experimental animals (Ramus, Davis, Donahue, Discenza, & Waite, 2007; Vafaei & Rashidy-Pour, 2004). White matter connections between OFC and MTL have also been demonstrated using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) in humans (Powell et al., 2004). Moreover, functional neuroimaging studies have shown that OFC and MTL are functionally connected during successful encoding (Ranganath, Heller, Cohen, Brozinsky, & Rissman, 2005), and are co-activated during the retrieval of positive autobiographical memories (Piefke, Weiss, Zilles, Markowitsch, & Fink, 2003). Yet, there is no direct evidence indicating that enhanced memory for happy faces reflects enhanced OFC and MTL activity and interactions between the two. Finding such evidence was the main goal of the present fMRI study.

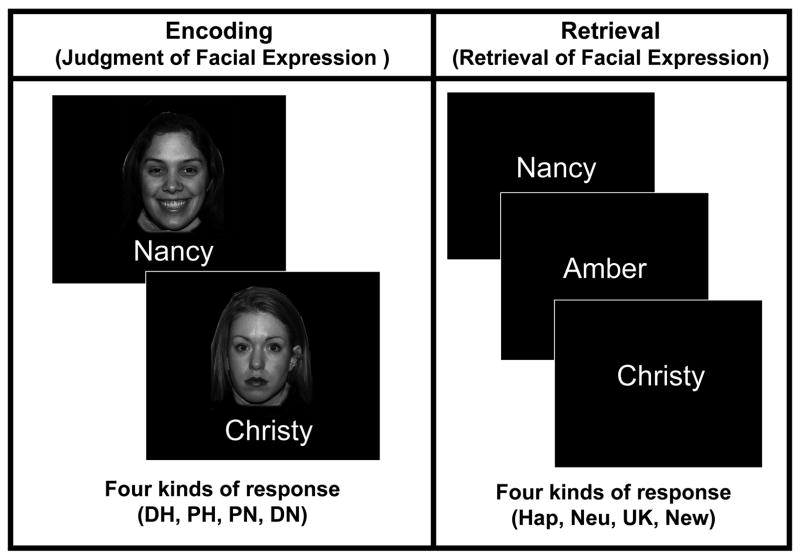

The design of the study is summarized by Fig. 1. During encoding, happy or neutral faces were presented paired with popular first names. Participants were instructed to learn the face-name associations by reading the name silently and rating the expression of the accompanying face (from definitely neutral to definitely happy). During retrieval, only the first names were presented, and for each one, participants indicated whether the name matched 1) a studied happy face, 2) a studied neutral face, 3) a studied face whose expression could not be retrieved, or 4) no studied face (i.e., a new name). The advantage of presenting only names during retrieval is that, with no face being presented, any difference between happy and neutral faces can be attributed to the content of retrieval rather than to the retrieval cues. Only old trials in which the name was correctly recognized as old were included in the analyses. Thus, the analyses focused on the retrieval of facial expressions, and compared trials in which the expression was successfully retrieved (Hit) with trials in which the expression retrieval was failed (Miss), either because the expression could not be retrieved (option 3 above) or because the incorrect expression was retrieved. Hit and Miss trials were further subdivided into happy and neutral conditions, yielding four critical trial types: Hit-Happy, Miss-Happy, Hit-Neutral, and Miss-Neutral. Using the subsequent memory paradigm (Paller & Wagner, 2002), encoding success activity (ESA) of face-name associations was identified by comparing study-phase activity for subsequent hits vs. subsequent misses. Likewise, retrieval success activity (RSA) for face-name associations was identified by comparing test-phase activity for hits vs. misses.

Fig. 1.

Task paradigm. During encoding, subjects were required to learn face-name associations, and to rate facial expressions with four response options (DH: definitely happy, PH: probably happy, PN: probably neutral, DN: definitely neutral). During retrieval, subjects were presented with studied and new names, and were required to retrieve the facial expressions associated with the names. Subjects responded with four response options (Hap: happy face, Neu: neutral face, UK: studied face of unknown expression, New: not studied face (i.e., New Name).

On the basis of the aforementioned research, we made three predictions. First, retrieval of face-name associations would be faster and more accurate for happy than neutral faces. Second, OFC and MTL activity associated with successful encoding and retrieval activity of face-name associations would be greater for happy than neutral faces. Finally, functional connectivity between the OFC and MTL regions during successful encoding and retrieval of face-name associations would also be greater for happy than neutral faces.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Twenty-two right-handed, college-aged participants were recruited from the Duke University community and paid for their participation. The data from 4 subjects were excluded from analyses because of extremely low memory performance (3 subjects) and scanner problems (1 subject). Thus, our analyses included data from 18 subjects (seven females) with an average age of 22.4 years (SD=3.9). All participants gave informed consent to a protocol approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Stimuli

We selected 120 faces with happy (smiling) expressions and 120 faces with neutral expressions from several face databases, including the NimStim Face Stimulus Set (www.macbrain.org/resources.htm), the AR Face Database (cobweb.ecn.purdue.edu/~aleix/aleix_face_DB.html), the CVL Face Database (www.lrv.fri.uni-lj.si/facedb.html), the PICS database (pics.psych.stir.ac.uk), FERET Database (www.itl.nist.gov/iad/humanid/feret/), and the Frontal Face Dataset (www.vision.caltech.edu/archive.html). All stimuli were converted into grayscale images with dimensions of around 218 × 225 pixels on a black background. Additionally, 360 popular first names were selected from an online name database (www.ssa.gov/OACT/babynames/). Two hundred forty names were randomly paired with study faces and 120 names were used as distractors in the test. Using the name frequency values provided by the database (i.e., percentage of babies given the name at birth), we found no significant differences between happy (0.19%, SD=0.25), neutral (0.19%, SD=0.25), and new (0.20%, SD=0.26) conditions [F (2,357)=0.10, p>0.90]. These 240 face-name pairs were divided into 5 lists of 48 pairs, which consisted of 24 happy and 24 neutral faces, and the 120 names used as distractors were also divided into 5 lists of 24 names.

2.3. Experimental task

Encoding and retrieval tasks were alternated across the 10 scans, with each retrieval scan testing memory for items encoded in the previous scan (i.e., 5 encoding-retrieval blocks). Scans were separated by a 1-min interval. In both phases, stimuli were presented for 2500 ms each and separated by a jittered fixation interval (500–5000 ms). The presentation order of experimental stimuli was randomized between subjects. Fig. 1 illustrates encoding and retrieval phases. During the encoding phase of each block, 48 face-name pairs were presented. Subjects were instructed to learn the face-name associations by reading the name silently and rating the facial expressions on a 4-point scale (i.e., definitely happy, probably happy, probably neutral, and definitely neutral). Only faces classified as expected (both levels of confidence) were included in fMRI analyses.

During the retrieval phase of each block, 48 old and 24 new names were presented in random order. For each name, participants indicated, by pressing a key, whether the name matched 1) a studied happy face, 2) a studied neutral face, 3) a studied face whose expression could not be retrieved, or 4) no studied face (i.e., a new name). Only old trials involving correct name recognition were included in the analyses. Thus, fMRI analyses focused on two main kinds of trials: (i) successful retrieval of facial expression (Hit) and (ii) unsuccessful retrieval of facial expression (Miss), in which either the expression could not be retrieved (option 3 above) or the retrieved expression was incorrect. Additionally, Hit and Miss trials were further subdivided into happy and neutral categories according to the subjective rating of facial expressions during encoding (Hit-Happy, Hit-Neutral, Miss-Happy and Miss-Neutral). For example, a Miss-Happy trial corresponds to an encoded happy face whose expression could not be retrieved during retrieval or was erroneously classified as neutral.

2.4. fMRI procedure and data analysis

All MRI data acquisition was conducted with a 4-T GE scanner. Stimuli were presented using liquid crystal display goggles, and behavioral responses were recorded using a 4-button fiber optic response box (Resonance Technology, Northridge, CA). Scanner noise was reduced with earplugs, and head motion was minimized using foam pads and a headband. Anatomical scans began by first acquiring a T1 weighted sagittal localizer series. Second, high-resolution T1-weighted structural images (256 × 256 matrix, TR=12 ms, TE=5 ms, FOV=24 cm, 68 slices, 1.9 mm slice thickness) were collected. Coplanar functional images were subsequently acquired utilizing an inverse spiral sequence (64 × 64 matrix, TR=1500 ms, TE=31 ms, Flip angle=60 degree, FOV=24 cm, 34 slices, 3.8 mm slice thickness).

The preprocessing and statistical analyses for all images were performed using SPM5 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). In the preprocessing analysis, after discarding the first four volumes, images were corrected for slice-timing and motion, then spatially normalized into the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template and spatially smoothed using a Gaussian kernel of 8 mm FWHM.

Statistical fMRI analyses were performed first at the subject level and then at the group level. At the subject level, fixed effect analyses were performed. Stimulus onsets were modeled as delta functions convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF) in the context of the general linear model (GLM). Confounding factors (head motion, magnetic field drift) were also included in the model. Successful and unsuccessful encoding activity for face-name associations was identified in the study-phase activity for subsequent hits and misses for each expression condition, whereas successful and unsuccessful retrieval activity for face-name associations was identified in the test-phase activity for hits and misses for each expression condition. All contrasts yielded a t-statistic in each voxel.

At the group level, random effect analyses were performed. The regions identified fulfilled two criteria. First, they showed significant encoding success activity (ESA: subsequent hits > subsequent misses) or retrieval success activity (RSA: hits > misses) for associations between happy face and name (ESA/RSA-Happy) at a threshold of p<0.001 (uncorrected) with minimum cluster size of 5 voxels outside OFC, MTL and amygdala regions. Within OFC and MTL regions-of-interest (ROI) a more lenient threshold of p<0.01 (uncorrected) with minimum cluster size of 5 voxels was employed, based on the a priori hypothesis. In addition, the same procedures of ROI analysis with OFC and MTL regions were applied to the amygdala region, to examine whether this region was significantly activated. The OFC (orbital part of the superior, middle and inferior frontal gyri), MTL (hippocampus and parahippocampal gyri) and amygdala ROIs were defined using the WFU PickAtlas (http://www.fmri.wfubmc.edu) and the AAL ROI package (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002). Second, in addition to a significant ESA/RSA for happy faces, activations also had to show greater ESA/RSA for happy than for neutral faces at a threshold of p<0.05 (inclusive masking by the contrasts of ESA/RSA-Happy vs. ESA/RSA-Neutral). Although these contrasts are not independent, the joint probability of fulfilling both criteria can be estimated to be around p < 0.0005 within OFC, MTL and amygdala regions, and p < 0.00005 outside these regions. All coordinates of activations were converted from MNI to Talairach space (Talairach & Tournoux, 1988) using MNI2TAL (http://www.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/Imaging/Common/mnispace.shtml).

To investigate the effects of happy expressions on functional connectivity between OFC and MTL regions activated in the previous analysis, we conducted a three-step analysis based on ‘individual trial activity’ (Rissman, Gazzaley, & D’Esposito, 2004), using a procedure that has been successfully applied in previous studies from our laboratory (Daselaar, Fleck, & Cabeza, 2006; Daselaar, Fleck, Dobbins, Madden, & Cabeza, 2006). First, we created a GLM, in which each individual trial was modeled by a separate covariate, yielding different parameter estimates for each individual trial and for each individual subject. Second, for each subject, activations in each individual trial were extracted from OFC and MTL ROIs, which were each defined as a cluster activated in the previous analysis. Pearson correlations between OFC and MTL were computed for individual trial activities of successful encoding and retrieval from all subjects (subsequent Hit-Happy vs. Hit-Neutral and Hit-Happy vs. Hit-Neutral). Finally, these correlation coefficients (r) were converted to z scores using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation, and then the difference of z scores between happy and neutral conditions were analyzed in the successful encoding and retrieval according to the standard normal distribution (one-tailed).

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral data

Mean reaction time for rating happy expressions during encoding was 118.7 ms faster than that for rating neutral expressions. To investigate if this difference interacted with subsequent memory, we conducted a 2 (Happy or Neutral) × 2 (subsequent Hit or Miss) ANOVA. This analysis showed a faster rating time for happy expressions than for neutral expressions [F(1,17)=27.42, p<0.001], but no interaction with subsequent memory. Thus, different subsequent memory effects on brain activity for happy vs. neutral faces cannot be attributed to differences in reaction times during encoding.

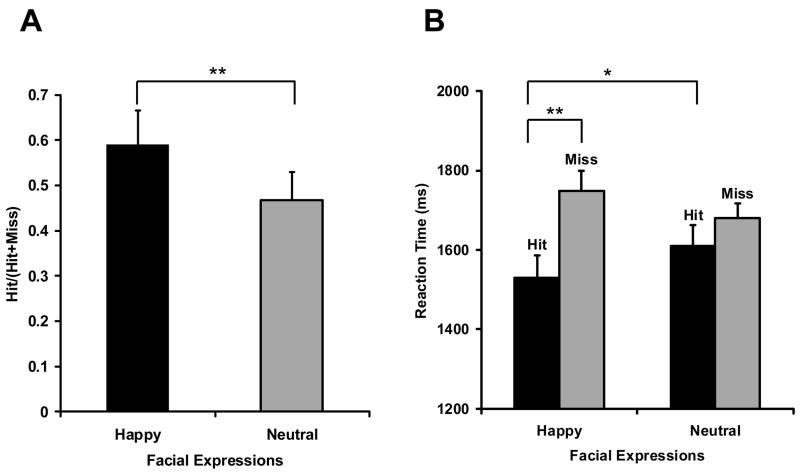

Confirming our first prediction, face-name associations involving happy faces were retrieved more accurately and faster than those involving neutral faces (see Table 1). The rate successfully retrieved facial expressions to successfully recognized names [i.e., Hit/(Hit+Miss)] was 59.0% in the happy condition and 46.8% in the neutral condition (Fig. 2A). This difference was significant [t(17)=3.39, p<0.01]. The findings cannot be attributed to a greater tendency to answer “Happy” than “Neutral” because the proportion of “Happy” (M=8.3%, SD=9.7) and “Neutral” (M=6.9%, SD=6.0) responses to new names (i.e., false alarms) did not differ significantly [t(17)=0.72, n.s.]. Regarding reaction times, successful retrieval of face-name associations in the happy condition was 80.9 ms faster than that in the neutral condition. To investigate latency differences, we conducted a 2 (Happy vs. Neutral) × 2 (Hit vs. Miss) ANOVA on the data (Fig. 2B). This analysis yielded slower responses for misses than for hits [F(1,17)=11.14, p<0.01] and a significant interaction between the two factors [F(1,17)=6.95, p<0.05]. Post-hoc tests showed faster reaction times for Hit-Happy than for Hit-Neutral (p<0.05) or Miss-Happy (p<0.01). In the reaction time data for false alarms, there was no significant difference between “Happy” (M=1551.8 ms, SD=215.9) and “Neutral” (M=1615.7 ms, SD=295.9) responses to new names [t(14)=−1.484, n.s.]. Reaction time data from three subjects were discarded for this analysis, because they showed no “Happy” or “Neutral” response to new names.

Table 1.

Behavioral results

| Happy | Neutral | |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction time (ms) in the encoding | ||

| Overall (HH+HM) | 1490.1 (251.1) | 1608.8 (232.0) |

| HH | 1481.5 (294.6) | 1589.2 (254.1) |

| HM | 1498.6 (207.2) | 1628.5 (213.1) |

| Retrieval accuracy (number of trials) | ||

| Overall (HH+HM) | 89.0 (27.1) | 75.6 (25.4) |

| HH | 55.0 (28.8) | 36.9 (21.4) |

| HM | 34.0 (13.5) | 38.6 (14.0) |

| Retrieval accuracy (%) | ||

| Overall (HH+HM) | 79.1 (14.5) | 76.6 (16.5) |

| HH | 47.9 (21.0) | 36.2 (17.1) |

| HM | 31.2 (13.3) | 40.4 (13.8) |

| Reaction time (ms) in the retrieval | ||

| Overall (HH+HM) | 1596.3 (206.6) | 1635.2 (169.6) |

| HH | 1529.5 (241.1) | 1610.4 (210.4) |

| HM | 1748.6 (218.0) | 1679.5 (162.3) |

( ): SD, Hit: successful retrieval of facial expressions from correctly recognized names, Miss: unsuccessful retrieval of facial expressions from correctly recognized names. Trials of unsuccessful recognition of names are not included in this table.

Fig. 2.

Behavioral data at the retrieval phase. Error bars represent standard error. (A) Hit rate [Hit/(Hit+Miss)]. (B) Reaction time (ms). Hit: successful retrieval of facial expressions and names, Miss: missed retrieval of facial expressions and successful retrieval of names, **: p<0.01, *: p<0.05.

3.2. Activation data in the successful encoding and retrieval

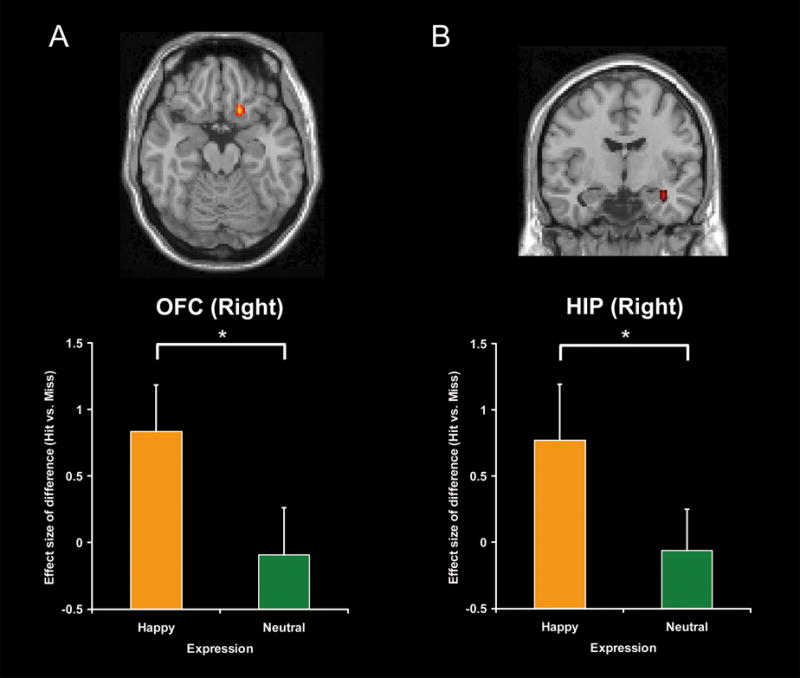

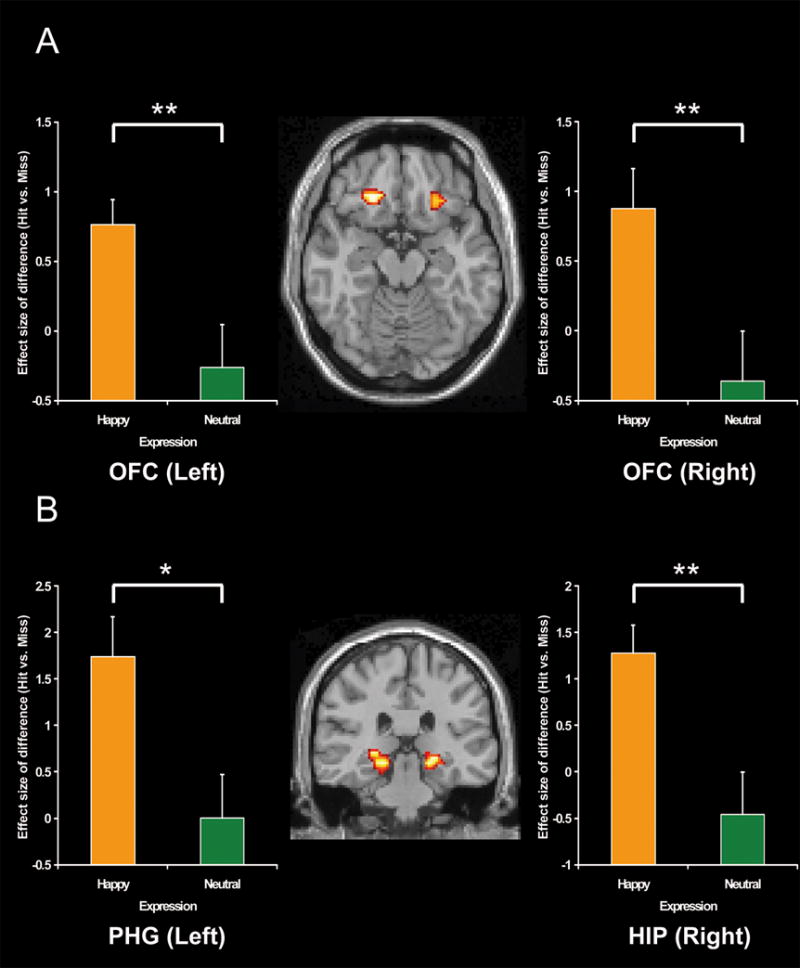

Confirming our second prediction, the presence of a smile enhanced ESA and RSA for face-name associations in OFC and MTL (see Table 2). During encoding, ESA was greater for happy than for neutral faces in the right OFC and in the right hippocampus (see Fig. 3). Other ESA regions showing this effect included bilateral middle temporal, precuneus, left inferior temporal, fusiform, parietal and right insula regions. During retrieval, RSA was greater for happy than for neutral expressions in bilateral OFC, right hippocampal and left parahippocampal regions (see Fig. 4). Another RSA region that showed this effect was the bilateral anterior cingulate gyrus and left hypothalamus.

Table 2.

Regions showing successful encoding and retrieval activity modulated by happy expressions

| Regions | L/R | BA | Coordinates

|

T value | Voxel size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Encoding | |||||||

| Predicted regions | |||||||

| Hippocampus | R | 30 | −5 | −19 | 2.87 | 5 | |

| Orbitofrontal cortex | R | 11 | 15 | 17 | −17 | 3.52 | 6 |

| Other regions | |||||||

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 37 | 45 | −65 | 3 | 3.32 | 6 |

| L | 37 | −52 | −62 | 3 | 3.56 | 11 | |

| Inferior temporal gyrus | L | 20 | −48 | −19 | −18 | 3.53 | 7 |

| fusiform gyrus | L | 37 | −45 | −44 | −14 | 3.44 | 5 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | L | 40 | −45 | −32 | 23 | 3.47 | 8 |

| Precuneus | RL | 31 | 0 | −61 | 24 | 4.15 | 29 |

| Insula | R | 13 | 37 | −25 | 19 | 3.52 | 12 |

| Retrieval | |||||||

| Predicted regions | |||||||

| Hippocampus | R | 22 | −30 | −8 | 3.83 | 21 | |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | L | 35 | −15 | −33 | −8 | 4.03 | 33 |

| Orbitofrontal cortex | R | 11 | 26 | 25 | −20 | 3.72 | 11 |

| L | 11 | −19 | 32 | −14 | 4.00 | 20 | |

| Other regions | |||||||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | RL | 24 | 0 | 40 | −2 | 4.15 | 44 |

| Hypothalamus | L | −7 | 3 | −7 | 4.01 | 9 | |

R: Right, L: Left, RL: Right and Left, BA: Brodmann area, Encoding: ESA-Happy masked inclusively with ESA-Happy vs. ESA-Neutral, Retrieval: RSA-Happy masked inclusively with RSA-Happy vs. RSA-Neutral

Fig. 3.

Activation images and effect sizes of right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and hippocampus (HIP) in the successful encoding of face-name associations for happy relative to neutral expressions. Error bars represent standard error. (A) Activation and effect sizes in the right orbitofrontal cortex. (B) Activation and effect sizes in the right hippocampus. *: p<0.05.

Fig. 4.

Activation images and effect sizes of bilateral orbitofrontal cortices (OFC), right hippocampus (HIP) and left parahippocampal gyrus (PHG) in the successful retrieval of face-name associations for happy relative to neutral expressions. Error bars represent standard error. (A) Activation and effect sizes in the bilateral orbitofrontal cortices. (B) Activation and effect sizes in the right hippocampus and left parahippocampal gyrus. **: p<0.01, *: p<0.05.

3.3. Functional connectivity between the OFC and MTL regions

Confirming our third prediction, functional connectivity between OFC and MTL during successful encoding and retrieval was enhanced by happy expressions (see Table 3). We compared correlations between individual-trial activity for happy and neutral conditions in the successful encoding and retrieval (see Methods). All positive correlations between the OFC and MTL regions were statistically significant for happy (data points: 986) and neutral trials (data points: 662) of successful encoding and retrieval (p<0.001), but the difference between happy and neutral faces was significant for the right OFC-right hippocampus correlation during successful encoding (p<0.05) and for the left OFC-right hippocampus correlation during successful retrieval (p<0.01).

Table 3.

Correlations in successful encoding activity (ESA) or successful retrieval activity (RSA) between orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and MTL (hippocampus: HIP and parahippocampal gyrus: PHG)

| Correlation coefficiant (R)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | Happy (986) | Neutral (662) | z value |

| ESA | |||

| R. OFC-R. HIP | 0.40 | 0.32 | 1.99* |

| RSA | |||

| R. OFC-R. HIP | 0.45 | 0.46 | −0.20 |

| R. OFC-L. PHG | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.99 |

| L. OFC-R. HIP | 0.58 | 0.47 | 2.78** |

| L. OFC-L. PHG | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.60 |

R: Right, L: Left, ( ): data points,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

4. Discussion

Three main findings emerged from the present study. First, face-name associations were remembered more accurately and faster for happy than for neutral faces. Second, successful encoding and retrieval activity in the OFC and MTL regions was greater for happy than for neutral expressions. Third, functional connectivity between the OFC and MTL (hippocampus) memory regions was significantly enhanced by happy expressions both during encoding and during retrieval. These three findings are discussed in separate sections below.

4.1. Effect of happy expressions on retrieval performance

The first main finding was that retrieval of face-name associations was more accurate and faster for happy faces than for neutral faces. This finding is consistent with the results by a previous behavioral study (Shimamura et al., 2006), in which participants encoded faces expressing happiness, surprise, anger, or fear, and were later tested on their memory for these expressions using the corresponding neutral faces as cues. Memory for faces with happy expressions was better than for faces with other expressions. The present study extends this result by showing better memory for happy faces when only names are presented during retrieval and associated facial expressions are only imagined. The enhancing effect of happy expression on memory for face-name associations may reflect a more general advantage for processing happy expressions. For example, there is evidence that happy expressions are identified faster than other expressions (Kaufmann & Schweinberger, 2004; Leppanen & Hietanen, 2004). This advantage of happy faces may reflect an adaptive tendency to approach to people who appear preferred or attractive. Consistent with this idea, a study found that happy faces were rated as more attractive than neutral faces (Otta et al., 1996).

The finding that happy faces enhanced memory performance of face-name associations better than neutral faces is also consistent with evidence that reward can enhance episodic memory processes (Adcock, Thangavel, Whitfield-Gabrieli, Knutson, & Gabrieli, 2006; Nielson & Bryant, 2005; Wittmann et al., 2005). Regarding faces, a previous study found that retrieving the names of celebrities was enhanced when the photos used as cues were displayed with smiling rather than with neutral expressions (Gallegos & Tranel, 2005). Extending this result, the present study suggests that a happy expression may enhance not only semantic memory for known face-name associations but also episodic memory for novel face-name associations. Thus, these findings suggest that socially positive signals conveyed from happy faces may act as a reward and facilitate face-name associations. This finding reflects adaptive sense given that it is advantageous to remember face-name associations for future social interactions.

Previous psychological studies have demonstrated that negative as well as positive material is better remembered by human subjects than neutral material (Bradley, Greenwald, Petry, & Lang, 1992). The experimental paradigm of our fMRI study could not discriminate whether the memory enhancement effect reflected arousal or the rewarding properties of happy faces. However, the results of behavioral study, in which we investigated the almost same paradigm using both happy and negative facial expressions, suggest the effect is specific to happy faces, and hence, it does not reflect arousal. In each block of this study, subjects encoded 30 face-name pairs, 10 with positive, 10 with negative, and 10 with neutral expressions, and then performed a recognition test with Remember/Know judgments. There were 5 study-test blocks (i.e., 150 face-name pairs). The proportion of Remember responses (i.e., recollection) was significantly greater for positive (M=0.32) than negative (M=0.26, p<0.05) and neutral (M=0.25, p<0.05) faces, with no significant difference between negative and neutral. These results suggest that the enhancing effect on memory for face-name associations is related to reward signals elicited by happy faces rather than to arousal signals elicited by emotional faces.

4.2. Orbitofrontal and medial temporal activations

The second main finding of our study was that the right OFC and hippocampus regions were significantly activated in the successful encoding of face-name associations and the bilateral OFC, right hippocampus and left parahippocampal gyrus in the successful retrieval of face-name associations, and that these successful memory activations were greater for happy than for neutral facial expressions. This finding suggests that the OFC and MTL regions contribute to the successful encoding and retrieval of face-name associations, and that their activity is enhanced by happy expressions.

The involvement of OFC in the processing of happy faces associated with names is consistent with functional neuroimaging evidence linking this region to the processing of happy facial expressions (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2001), face preference decision (Kim et al., 2007) and attractive faces (Ishai, 2007; Kranz & Ishai, 2006; O’Doherty et al., 2003; Winston et al., 2007). For example, O’Doherty et al. (2003) found that the OFC region was significantly activated in the processing of attractive faces, and the activity of this region was enhanced by smiling facial expressions. The activation pattern of this region has been supported by neuropsychological studies for patients with OFC lesions, who are impaired in the processing of facial expressions (Blair & Cipolotti, 2000; Hornak et al., 2003; Hornak et al., 1996). Moreover, there is cognitive neuroscience evidence suggesting that the OFC region is involved in a network of reward-related regions (for review, see Martin-Soelch et al., 2001; McClure et al., 2004; O’Doherty, 2004; Rolls, 2000). Thus, happy faces and socially positive signals conveyed by happy faces may engage OFC, which could mediate the rewarding feeling associated with happy faces, and the OFC role may explain why people with happy faces are seen as more approachable.

Moreover, the present data showed that the differential involvement of OFC in processing happy faces interacts with memory performance, as it was greater for remembered than forgotten happy faces both during encoding and during retrieval. The role of OFC in successful face encoding is consistent with the results of a positron emission tomography (PET) study, which found that the OFC activity while participants encoded faces was positively correlated with subsequent memory for the faces (Frey & Petrides, 2003). The present results extend this finding in several ways. First, the contribution of OFC to face memory was found by comparing successful with unsuccessful memory trials within participants, both during encoding and during retrieval. Second, the present study shows that OFC contributes to the encoding of face-name associations and to the retrieval of faces in response to names, suggesting that OFC is involved in face memory even when the faces are only imagined. Finally, and most importantly, the present study demonstrates that the contribution of OFC to memory for faces interacts with its role in processing happy facial expressions: OFC activity was the greatest when the faces were both happy and successfully remembered.

The activation of the right hippocampus in the successful encoding and retrieval of face-name associations is consistent with functional neuroimaging evidence linking this region to relational memory encoding and retrieval (Achim & Lepage, 2005; Bunge et al., 2004; Duzel et al., 2003; Giovanello et al., 2004; Jackson & Schacter, 2004; Meltzer & Constable, 2005; Prince et al., 2005; Prince et al., 2007; Ranganath et al., 2004; Yonelinas et al., 2001), including memory for face-name associations (Chua et al., 2007; Kirwan & Stark, 2004; Paller et al., 2003; Small et al., 2001; Sperling et al., 2001; Sperling et al., 2003; Tsukiura et al., 2007; Zeineh et al., 2003). In addition, there is evidence that reward can enhance memory-related activity in the hippocampus (Adcock et al., 2006; Wittmann et al., 2005). For example, one scene memory study found that monetary reward enhanced hippocampal activity during encoding and subsequent memory for the scenes (Adcock et al., 2006). The present results extend this finding by demonstrating this effect using social rewards from happy faces rather than monetary rewards and by showing the effect both during encoding and during retrieval.

The present data also showed that the parahippocampal gyrus as well as the hippocampus was involved in the successful retrieval of face-name associations. This finding is consistent with the results of functional neuroimaging studies that found the parahippocampal activity in the processing of source or contextual information of episodic memory (Burgess, Maguire, Spiers, & O’Keefe, 2001; Cansino, Maquet, Dolan, & Rugg, 2002; Dobbins, Rice, Wagner, & Schacter, 2003; Dudukovic & Wagner, 2007; Hayes, Nadel, & Ryan, 2007; Kahn, Davachi, & Wagner, 2004; King, Hartley, Spiers, Maguire, & Burgess, 2005; Ranganath, Johnson, & D’Esposito, 2003; Simons, Owen, Fletcher, & Burgess, 2005; Tsukiura et al., 2002). In addition, there is evidence that the parahippocampal activation during remembering negative faces associated with names was greater than that during remembering neutral faces associated with names (Fenker, Schott, Richardson-Klavehn, Heinze, & Duzel, 2005). Thus, the present results extend these findings by demonstrating that the parahippocampal gyrus was significantly activated in the retrieval of facial expressions as contextual information, and this activation was enhanced even by happy facial expressions.

In contrast to our finding for OFC and MTL, successful memory activity in the amygdala was not enhanced by happy expressions. This finding differs from many previous findings linking the amygdala to the processing of negative facial expressions such as fear, anger or disgust (Adolphs, Tranel, Damasio, & Damasio, 1994; Breiter et al., 1996; Broks et al., 1998; Morris et al., 1996; Phillips et al., 1998). Neuropsychological studies have also reported that patients with amygdala lesions are impaired in the judgment of face-based social signals, especially negative social signals related to unapproachable or untrustworthy looking faces (Adolphs, Tranel, & Damasio, 1998). Thus, it is possible that a significant enhancement of facial expression on memory-related activity in the amygdala would have been found using negative rather than positive facial expression. However, a few functional neuroimaging studies have shown the amygdala activity for both negative and positive facial expressions (Keightley et al., 2007; Winston et al., 2003), and in the present study, we found a very weak activity of amygdala when we lowered the threshold to p < 0.05. This issue warrants further research.

4.3. Functional connectivity between the orbitofrontal and medial temporal regions

The third main finding of our study was that functional connectivity between the OFC and MTL activations was significant during the successful encoding and retrieval of face-name associations, and the connectivity between OFC and hippocampus was greater during the successful encoding and retrieval of happy than neutral faces associated with names. These findings suggest that the interaction between these regions contributes to the successful encoding and retrieval of memory for face-name associations, and that the interaction is enhanced when the facial expression is smiling.

The significant interaction between the OFC and MTL regions in the successful encoding and retrieval of face-name associations is consistent with anatomical evidence that the OFC region maintains strong connections with the MTL region (Barbas & Blatt, 1995; Carmichael & Price, 1995; Lavenex et al., 2002), and with cognitive neuroscience evidence that the OFC-MTL interaction contributes to the long-term memory processing in experimental animals (Ramus et al., 2007; Vafaei & Rashidy-Pour, 2004). This finding is also consistent with the results of a previous functional neuroimaging study, in which the MTL activity during successful encoding was functionally connected with the OFC and other cortical activity (Ranganath et al., 2005). Moreover, the OFC-MTL connection has been identified in human subjects using DTI (Powell et al., 2004). In the present study, we found that an interaction between the OFC and MTL regions contributed to both phases of successful encoding and retrieval of association memory. The present results extend previous findings by demonstrating the OFC-MTL interaction in the processing of relational memory such as face-name associations and in both phases of encoding and retrieval.

Moreover, the present data showed that an interaction between OFC and MTL regions in memory for face-name associations was enhanced by happy facial expressions, and the enhancement was limited to the hippocampus but not to the parahippocampal gyrus. Previous neuroimaging studies have reported that the parahippocampal cortex contributes to the processing of contextual information during encoding and retrieval, whereas the hippocampus is involved in the association or relational memory process between item and contextual information (for review, see Diana, Yonelinas, & Ranganath, 2007). The present finding of an enhanced connectivity between OFC and hippocampal regions by happy faces suggests that the OFC response to happy faces modulates the relational memory process of face-name associations by the hippocampus not only during successful encoding but also during successful retrieval, even if in the latter facial expressions are only imagined. The better retrieval performance of face-name associations could be explained by the enhanced connectivity between the OFC and hippocampus regions in happy facial expressions.

4.4. Conclusion

Using event-related fMRI, we investigated the effect of a rewarding smile on successful encoding and retrieval of face-name associations. Consistent with past research, the behavioral results showed that the retrieval of facial expressions associated with names was faster and more accurate for smiling than for neutral faces. fMRI results showed that the OFC and MTL (hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus) activations were greater during successful encoding and retrieval of face-name pairs involving smiling than neutral faces. Finally, during successful encoding and retrieval trials, OFC-hippocampus interactions across individual trials were significantly enhanced by smiling expressions. Taken together, the results suggest that the enhancing effect of smiling expressions on memory for face-name associations reflects a reward mechanism mediated by OFC, which enhances relational memory operations mediated by the hippocampal memory system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Florin Dolcos for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript, Steven Prince for advice on data analysis and interpretation, Amber Baptiste Tarter for participant recruitment and supporting task instruction, Christy Krupa and Matt Lowder for editing this manuscript, and Chih- Chen Wang and James Kragel for technical assistance. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS41328 and AG23770. T.T. was supported by the AIST fellowship program from National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Japan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achim AM, Lepage M. Neural correlates of memory for items and for associations: an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005;17:652–667. doi: 10.1162/0898929053467578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adcock RA, Thangavel A, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Knutson B, Gabrieli JD. Reward-motivated learning: mesolimbic activation precedes memory formation. Neuron. 2006;50:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio AR. The human amygdala in social judgment. Nature. 1998;393:470–474. doi: 10.1038/30982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio A. Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature. 1994;372:669–672. doi: 10.1038/372669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharon I, Etcoff N, Ariely D, Chabris CF, O’Connor E, Breiter HC. Beautiful faces have variable reward value: fMRI and behavioral evidence. Neuron. 2001;32:537–551. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H, Blatt GJ. Topographically specific hippocampal projections target functionally distinct prefrontal areas in the rhesus monkey. Hippocampus. 1995;5:511–533. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450050604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudouin JY, Gilibert D, Sansone S, Tiberghien G. When the smile is a cue to familiarity. Memory. 2000;8:285–292. doi: 10.1080/09658210050117717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Cipolotti L. Impaired social response reversal. A case of ‘acquired sociopathy’. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 6):1122–1141. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Greenwald MK, Petry MC, Lang PJ. Remembering pictures: pleasure and arousal in memory. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1992;18:379–390. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.18.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiter HC, Etcoff NL, Whalen PJ, Kennedy WA, Rauch SL, Buckner RL, et al. Response and habituation of the human amygdala during visual processing of facial expression. Neuron. 1996;17:875–887. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broks P, Young AW, Maratos EJ, Coffey PJ, Calder AJ, Isaac CL, et al. Face processing impairments after encephalitis: amygdala damage and recognition of fear. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge SA, Burrows B, Wagner AD. Prefrontal and hippocampal contributions to visual associative recognition: interactions between cognitive control and episodic retrieval. Brain Cogn. 2004;56:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N, Maguire EA, Spiers HJ, O’Keefe J. A temporoparietal and prefrontal network for retrieving the spatial context of lifelike events. Neuroimage. 2001;14:439–453. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Nyberg L. Imaging cognition II: An empirical review of 275 PET and fMRI studies. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12:1–47. doi: 10.1162/08989290051137585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cansino S, Maquet P, Dolan RJ, Rugg MD. Brain activity underlying encoding and retrieval of source memory. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:1048–1056. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.10.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Price JL. Limbic connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1995;363:615–641. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua EF, Schacter DL, Rand-Giovannetti E, Sperling RA. Evidence for a specific role of the anterior hippocampal region in successful associative encoding. Hippocampus. 2007;17:1071–1080. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Rolls ET. Hunger and satiety modify the responses of olfactory and visual neurons in the primate orbitofrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:1673–1686. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.4.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Cabeza R. Triple dissociation in the medial temporal lobes: recollection, familiarity, and novelty. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:1902–1911. doi: 10.1152/jn.01029.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Dobbins IG, Madden DJ, Cabeza R. Effects of healthy aging on hippocampal and rhinal memory functions: an event-related fMRI study. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:1771–1782. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L. Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana RA, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. Imaging recollection and familiarity in the medial temporal lobe: a three-component model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins IG, Rice HJ, Wagner AD, Schacter DL. Memory orientation and success: separable neurocognitive components underlying episodic recognition. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:318–333. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcos F, LaBar KS, Cabeza R. Interaction between the amygdala and the medial temporal lobe memory system predicts better memory for emotional events. Neuron. 2004;42:855–863. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcos F, LaBar KS, Cabeza R. Remembering one year later: role of the amygdala and the medial temporal lobe memory system in retrieving emotional memories. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2626–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409848102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudukovic NM, Wagner AD. Goal-dependent modulation of declarative memory: neural correlates of temporal recency decisions and novelty detection. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2608–2620. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duzel E, Habib R, Rotte M, Guderian S, Tulving E, Heinze HJ. Human hippocampal and parahippocampal activity during visual associative recognition memory for spatial and nonspatial stimulus configurations. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9439–9444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09439.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenker DB, Schott BH, Richardson-Klavehn A, Heinze HJ, Duzel E. Recapitulating emotional context: activity of amygdala, hippocampus and fusiform cortex during recollection and familiarity. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1993–1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey S, Petrides M. Greater orbitofrontal activity predicts better memory for faces. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2755–2758. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos DR, Tranel D. Positive facial affect facilitates the identification of famous faces. Brain Lang. 2005;93:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanello KS, Schnyer DM, Verfaellie M. A critical role for the anterior hippocampus in relational memory: evidence from an fMRI study comparing associative and item recognition. Hippocampus. 2004;14:5–8. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Pradelli S, Serafini M, Pagnoni G, Baraldi P, Porro C, et al. Explicit and incidental facial expression processing: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2001;14:465–473. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SM, Nadel L, Ryan L. The effect of scene context on episodic object recognition: parahippocampal cortex mediates memory encoding and retrieval success. Hippocampus. 2007;17:873–889. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson R. A mini-review of fMRI studies of human medial temporal lobe activity associated with recognition memory. Q J Exp Psychol B. 2005;58:340–360. doi: 10.1080/02724990444000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornak J, Bramham J, Rolls ET, Morris RG, O’Doherty J, Bullock PR, et al. Changes in emotion after circumscribed surgical lesions of the orbitofrontal and cingulate cortices. Brain. 2003;126:1691–1712. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornak J, Rolls ET, Wade D. Face and voice expression identification in patients with emotional and behavioural changes following ventral frontal lobe damage. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34:247–261. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishai A. Sex, beauty and the orbitofrontal cortex. Int J Psychophysiol. 2007;63:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson O, 3rd, Schacter DL. Encoding activity in anterior medial temporal lobe supports subsequent associative recognition. Neuroimage. 2004;21:456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn I, Davachi L, Wagner AD. Functional-neuroanatomic correlates of recollection: implications for models of recognition memory. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4172–4180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0624-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann JM, Schweinberger SR. Expression influences the recognition of familiar faces. Perception. 2004;33:399–408. doi: 10.1068/p5083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata H, Zeki S. Neural correlates of beauty. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1699–1705. doi: 10.1152/jn.00696.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley ML, Chiew KS, Winocur G, Grady CL. Age-related differences in brain activity underlying identification of emotional expressions in faces. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2:292–302. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Adolphs R, O’Doherty JP, Shimojo S. Temporal isolation of neural processes underlying face preference decisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18253–18258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703101104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JA, Hartley T, Spiers HJ, Maguire EA, Burgess N. Anterior prefrontal involvement in episodic retrieval reflects contextual interference. Neuroimage. 2005;28:256–267. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan CB, Stark CEL. Medial temporal lobe activation during encoding and retrieval of novel face-name pairs. Hippocampus. 2004;14:919–930. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz F, Ishai A. Face perception is modulated by sexual preference. Curr Biol. 2006;16:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavenex P, Suzuki WA, Amaral DG. Perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices of the macaque monkey: projections to the neocortex. J Comp Neurol. 2002;447:394–420. doi: 10.1002/cne.10243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen JM, Hietanen JK. Positive facial expressions are recognized faster than negative facial expressions, but why? Psychol Res. 2004;69:22–29. doi: 10.1007/s00426-003-0157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Soelch C, Leenders KL, Chevalley AF, Missimer J, Kunig G, Magyar S, et al. Reward mechanisms in the brain and their role in dependence: evidence from neurophysiological and neuroimaging studies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;36:139–149. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, York MK, Montague PR. The neural substrates of reward processing in humans: the modern role of FMRI. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:260–268. doi: 10.1177/1073858404263526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer JA, Constable RT. Activation of human hippocampal formation reflects success in both encoding and cued recall of paired associates. Neuroimage. 2005;24:384–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Frith CD, Perrett DI, Rowland D, Young AW, Calder AJ, et al. A differential neural response in the human amygdala to fearful and happy facial expressions. Nature. 1996;383:812–815. doi: 10.1038/383812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielson KA, Bryant T. The effects of non-contingent extrinsic and intrinsic rewards on memory consolidation. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2005;84:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JP. Reward representations and reward-related learning in the human brain: insights from neuroimaging. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JP, Winston J, Critchley H, Perrett D, Burt DM, Dolan RJ. Beauty in a smile: the role of medial orbitofrontal cortex in facial attractiveness. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otta E, Folladore Abrosio F, Hoshino RL. Reading a smiling face: messages conveyed by various forms of smiling. Percept Mot Skills. 1996;82:1111–1121. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.82.3c.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paller KA, Ranganath C, Gonsalves B, LaBar KS, Parrish TB, Gitelman DR, et al. Neural correlates of person recognition. Learn Mem. 2003;10:253–260. doi: 10.1101/lm.57403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paller KA, Wagner AD. Observing the transformation of experience into memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01845-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Young AW, Scott SK, Calder AJ, Andrew C, Giampietro V, et al. Neural responses to facial and vocal expressions of fear and disgust. Proc Biol Sci. 1998;265:1809–1817. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piefke M, Weiss PH, Zilles K, Markowitsch HJ, Fink GR. Differential remoteness and emotional tone modulate the neural correlates of autobiographical memory. Brain. 2003;126:650–668. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell HW, Guye M, Parker GJ, Symms MR, Boulby P, Koepp MJ, et al. Noninvasive in vivo demonstration of the connections of the human parahippocampal gyrus. Neuroimage. 2004;22:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince SE, Daselaar SM, Cabeza R. Neural correlates of relational memory: successful encoding and retrieval of semantic and perceptual associations. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2540-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince SE, Tsukiura T, Cabeza R. Distinguishing the neural correlates of episodic memory encoding and semantic memory retrieval. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:144–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramus SJ, Davis JB, Donahue RJ, Discenza CB, Waite AA. Interactions Between the Orbitofrontal Cortex and Hippocampal Memory System During the Storage of Long-Term Memory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1196/annals.1401.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, Cohen MX, Dam C, D’Esposito M. Inferior temporal, prefrontal, and hippocampal contributions to visual working memory maintenance and associative memory retrieval. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3917–3925. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5053-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, Heller A, Cohen MX, Brozinsky CJ, Rissman J. Functional connectivity with the hippocampus during successful memory formation. Hippocampus. 2005;15:997–1005. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, Johnson MK, D’Esposito M. Prefrontal activity associated with working memory and episodic long-term memory. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:378–389. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapcsak SZ. Face memory and its disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2003;3:494–501. doi: 10.1007/s11910-003-0053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman J, Gazzaley A, D’Esposito M. Measuring functional connectivity during distinct stages of a cognitive task. Neuroimage. 2004;23:752–763. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. The orbitofrontal cortex and reward. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:284–294. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Sienkiewicz ZJ, Yaxley S. Hunger Modulates the Responses to Gustatory Stimuli of Single Neurons in the Caudolateral Orbitofrontal Cortex of the Macaque Monkey. Eur J Neurosci. 1989;1:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1989.tb00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura AP, Ross JG, Bennett HD. Memory for facial expressions: the power of a smile. Psychon Bull Rev. 2006;13:217–222. doi: 10.3758/bf03193833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Owen AM, Fletcher PC, Burgess PW. Anterior prefrontal cortex and the recollection of contextual information. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:1774–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Nava AS, Perera GM, DeLaPaz R, Mayeux R, Stern Y. Circuit mechanisms underlying memory encoding and retrieval in the long axis of the hippocampal formation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:442–449. doi: 10.1038/86115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AP, Stephan KE, Rugg MD, Dolan RJ. Task and content modulate amygdala-hippocampal connectivity in emotional retrieval. Neuron. 2006;49:631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Bates JF, Cocchiarella AJ, Schacter DL, Rosen BR, Albert MS. Encoding novel face-name associations: a functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;14:129–139. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Chua E, Cocchiarella A, Rand-Giovannetti E, Poldrack R, Schacter DL, et al. Putting names to faces: successful encoding of associative memories activates the anterior hippocampal formation. Neuroimage. 2003;20:1400–1410. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00391-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-Planar Stereotactic Atlas of the Human Brain: 3-dimensional Proportional System: An Approach to Cerebral Imaging. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiura T, Fujii T, Takahashi T, Xiao R, Sugiura M, Okuda J, et al. Medial temporal lobe activation during context-dependent relational processes in episodic retrieval: an fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17:203–213. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiura T, Suzuki C, Shigemune Y, Mochizuki-Kawai H. Differential contributions of the anterior temporal and medial temporal lobe to the retrieval of memory for person identity information. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007 doi: 10.1002/hbm.20469. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafaei AA, Rashidy-Pour A. Reversible lesion of the rat’s orbitofrontal cortex interferes with hippocampus-dependent spatial memory. Behav Brain Res. 2004;149:61–68. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JS, O’Doherty J, Dolan RJ. Common and distinct neural responses during direct and incidental processing of multiple facial emotions. Neuroimage. 2003;20:84–97. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JS, O’Doherty JP, Kilner JM, Perrett DI, Dolan RJ. Brain systems for assessing facial attractiveness. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JS, Strange BA, O’Doherty J, Dolan RJ. Automatic and intentional brain responses during evaluation of trustworthiness of faces. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:277–283. doi: 10.1038/nn816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann BC, Schott BH, Guderian S, Frey JU, Heinze HJ, Duzel E. Reward-related FMRI activation of dopaminergic midbrain is associated with enhanced hippocampus-dependent long-term memory formation. Neuron. 2005;45:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonelinas AP, Hopfinger JB, Buonocore MH, Kroll NE, Baynes K. Hippocampal, parahippocampal and occipital-temporal contributions to associative and item recognition memory: an fMRI study. Neuroreport. 2001;12:359–363. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200102120-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeineh MM, Engel SA, Thompson PM, Bookheimer SY. Dynamics of the hippocampus during encoding and retrieval of face-name pairs. Science. 2003;299:577–580. doi: 10.1126/science.1077775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]