The mammalian cell cycle

Eukaryotic cell division is distinguished by four distinct phases of the cell cycle. The G1 phase prepares the cellular machinery for DNA replication, followed by S-phase during which chromosomes are actively replicated. Subsequently the cell enters a further gap period G2 prior to chromosome segregation and cytokinesis in M phase (Mitosis). Factors initiating mitosis are rapidly inactivated thereby completing the cycle and preparing for a further round of cell division and immediate re-entry into G1. Inevitably, conditions may preclude mammalian cell division either physiologically during tissue development, differentiation and senescence or pathologically in a growth factor or nutrient-deprived environment. The cell has adapted to enter a dormant period G0, prior to entry into G1, during which the cell cycle machinery remains inactive. The orderly progression of one phase of the cell cycle to the next is essential to ensure faithful chromosome replication and separation, thereby maintaining genetic stability of daughter cells. A complex network of cellular ‘checkpoints’ is responsible for ensuring that DNA synthesis occurs after G1 at a point after the cellular environment has been monitored and metabolic enzymes have been synthesized. Further checkpoints ensure that mitosis only occurs after chromatids have been replicated and DNA repair completed. Failure of the checkpoints to arrest the cell cycle may result in genetic instability, contributing to uncontrolled proliferation essential for cancer development (Hartwell & Kastan 1994).

The key checkpoint initiating the completion of the cell cycle occurs in mid-G1 phase and is called the ‘Restriction Point’ in mammalian cells and defined as a discrete time point in mid-to-late G1 phase at which cells commit to entering S phase and to completing the round of cell division (Pardee 1974).

Regulation of G1 phase of the mammalian cell cycle

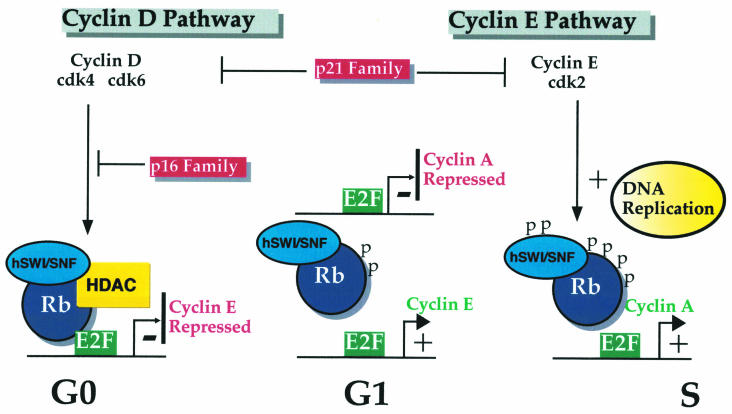

Passage through G1 phase into S phase is regulated by the Retinoblastoma tumour suppressor gene product, pRB, which acts as a suppressor of passage through the G1 phase in its hypophosphorylated state. The retinoblastoma protein in its hypophosphorylated state tethers and represses the E2F transcription factor. pRb-mediated repression is thought to occur in two ways. Firstly, Rb induces modification of the histones in the nucleosome by recruiting the histone de-acetylase, HDAC to E2F sites (Brehm et al. 1998; Luoet al. 1998; Magnaghi-Jaulin et al. 1998). Secondly, recent developments have established that Rb regulates nucleosome structure by recruiting ATP-dependent remodelling complexes to promoters (Zhang et al. 2000). These include components with ATPase activity known as SWI/SNF complexes (human SWI/SNF ATPases are known as BRG1 and hBRM). The phosphorylation state of pRB is critical in controlling its growth suppressive activity. This process is governed by a partnership of proteins, the cyclin dependent kinase (cdk) and its obligate partner, the cyclin (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cell cycle regulation of pRb. In G0 cells, pRb complexed to hSWI/SNF and HDAC bind to E2F leading to repression of E2F target genes such as cyclin E. Progression through G1 is accompanied by sequential activation of cyclin D and cyclin E associated cdk complexes. Cyclin D/cdk4 or cdk6 complexes relieve repression of cyclin E expression through the phosphorylation of pRb and release of HDAC. Further phosphorylation of pRb and hSWI/SNF by cyclin E/cdk2 complex results in derepression of additional target genes including cyclin A.

There are two families of cyclin necessary for the completion of the G1 phase and passage into the S phase: the cyclin D family (comprising cyclins D1, D2 and D3), and the cyclin E family (cyclins E1 and the recently cloned cyclin E2 (Sherr 1996; Lauper et al. 1998). The cyclin D family activate their principal partners, the cyclin-dependent kinases, cdk4 and cdk6. The cyclin E family form complexes with and activates cdk2. It now seems likely that sequential activation of the cyclin D dependent kinases followed by the cyclin E dependent kinases is necessary for the orchestrated phosphorylation of pRb and de-repression of E2F-dependent genes (Lundberg & Weinberg 1998). It is becoming clearer how the cyclin D and cyclin E family conduct progression through G1 into the S phase (Figure 1); cyclin D/cdk4 complexes phosphorylate Rb in early G1 phase leading to release of HDAC and de-repression of the cyclin E gene. The Rb-hSWI/SNF complex remains, maintaining repression of the cyclin A gene, preventing exit from the S phase. Once sufficient cyclin E/cdk2 activity is established, repression by the Rb-hSWI/SNF complex is relieved through phosphorylation of the hSWI/SNF complex and Rb (Shanahan et al. 1999; Zhang et al. 2000). Furthermore, Cyclin E has targets other than pRb and hSWI/SNF necessary for completion of the G1 phase, such as components of the DNA synthesis machinery (Krude et al. 1997).

Regulation of Cdk activity

Cdk regulation occurs predominantly at the post-translational level, as protein levels remain relatively constant throughout the cell cycle (Simanis & Nurse 1986). Inhibitory phosphorylation on N-terminal Threonine and Tyrosine residues maintain kinase complexes in an inactive state (Gould & Nurse 1989; Krek & Nigg 1991). Positive regulation of cdk activity occurs in two steps: dephosphorylation of the Threonine and Tyrosine residues by the cdc25 phosphatase family (Gautier et al. 1991), and phosphorylation of a central Threonine residue by the cdk activating kinase (CAK).

The Cdc25 phosphatase family

Phosphorylation of Threonine 14 and Tyrosine 15 of cdc2, close to the ATP binding site, is inhibitory and prevents immediate activation of newly formed complexes (Gould & Nurse 1989; Krek & Nigg 1991). Phosphorylation at these sites is carried out by the yeast S.pombe homologues of the protein kinases Wee1 and Mik1 (for review see Lew & Kornbluth 1996).

Dephosphorylation of these residues is achieved by homologues of the cdc25 gene product. There are three known human cdk-activating phosphatases, cdc25A, B and C which show temporal expression in the cell cycle (Galaktionov & Beach 1991).

Given the role of these phosphatases in cdk activation, it is not surprising that the G1 phase phosphatases cdc25A and cdc25B are candidate oncogenes and cooperate with the activated Ras mutant, RasG12V, or loss of Rb in oncogenic focus formation (Galaktionov et al. 1995).

The Cdk activating kinase (CAK)

Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of a conserved Threonine residue, corresponding to Threonine 160 of human cdk2, represents another focus of regulation. Structural data indicates that this residue resides in a buried region of the cdk known as the T-loop and becomes accessible to phosphorylation upon cyclin binding. Phosphorylation of this residue is mediated by CAK whereas dephosphorylation, which inactivates the kinase, can be achieved by the cdk-associated phosphatase KAP (Poon & Hunter 1995).

The Cdk inhibitory proteins (CKIs)

Eukaryotic cells have developed ingenious methods to restrict the activities of the cyclin/cdk partnership, thereby arresting Rb hyperphosphorylation and inhibiting progression through the G1 phase. One mechanism of cyclin/cdk regulation occurs through two families of cdk inhibitory proteins (CKI's), the p16 and the p21 families (Hall et al. 1995).

The first family of proteins, typified by the melanoma tumour suppressor protein p16ink4a (inhibitor of cdk4), bind to and inactivate cdk4 and cdk6 independently of the cyclin subunit. There are four members of this family, p15, p16, p18 and p19.

The second family, typified by p21cip1, interact with both the cyclin and the cdk subunits, inhibiting the holoenzyme in a ternary complex. There are three members of this family, p21cip1, p27kip1 and p57kip2.

Targets for viral gene products

The study of DNA viruses has given vast insight into the importance of the cell cycle regulators described above. Although DNA tumour viruses encode many proteins that are directly involved in viral DNA synthesis, they do not encode the enzymatic activities that create the necessary substrates for DNA synthesis. These viruses primarily infect quiescent cells, and since the environment is not conducive to viral DNA synthesis (rate-limiting levels of deoxynucleotides (Thelander & Reichard 1979) it is thought they must induce cells to enter the S phase. The ability of adenovirus, human papilloma virus (HPV) and SV40 to drive quiescent cells through G1 into S is a direct result of expression of the viral proteins, E1A, E7 and Large T, respectively. These gene products all inactivate Rb by binding directly to the pocket region, abrogating the need for phosphorylation by G1 cdk's. Indeed, mutations that abolish the ability of the viral oncoproteins to disrupt the restriction point are also mutations that affect their ability to bind Rb (Helin & Harlow 1993).

Intriguingly, the theme of G1 phase disruption is conserved among several larger DNA viruses. Furthermore, it is a tribute to viral opportunism that Rb is not the only victim of virally mediated cell cycle disruption. This review will illustrate how both the CKI's and cyclins themselves are vulnerable to disruption by diverse viral gene products. Finally, recent data will be highlighted demonstrating that certain viral gene products can induce a cell cycle arrest, which maybe beneficial for the Epstein Barr virus lytic switch and in the case of HIV, in preventing apoptosis or increasing virion production.

The small DNA tumour viruses

Adenovirus E1A

Studies in many cell types have demonstrated that TGFß treatment leads to a G1 cell cycle arrest. This arrest is associated with a decrease in G1 cyclin/cdk complex kinase activity (Koff et al. 1993), hypophosphorylated Rb and an activation of the CKIs p15, p21 and p27 (Hannon & Beach 1994; Polyak et al. 1994a; Polyak et al. 1994b; Datto et al. 1995). Iavarone et al. also showed that TGFß treatment in cells lacking p15 increases the level of inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation on cdk4/6 due to repression of the phosphatase, cdc25A (Iavarone & Massague 1997).

Interestingly, E1A is capable of stimulating the phosphorylation of Rb in TGFß-treated cells and blocks the TGFß-mediated decrease in activity of cyclin-Cdc2 complexes, independently of its ability to bind Rb (Wang et al. 1991; Abraham et al. 1992). This observation suggested that E1A must target other key regulators of the restriction point. Indeed, Mal and colleagues demonstrated that E1A inactivates p27 in TGFß-treated mink lung epithelial cells, by virtue of the interaction of E1A with p27 (Mal et al. 1996). It has been proposed that the interaction of E1A with p27 may regulate the phosphorylation status of E1A (Nomura et al. 1998). Furthermore, the ability of E1A to overcome a TGFß arrest in HaCaT human keratinocyte cells derives in part from its ability to act upstream of Rb by blocking the TGFß induction of p15 and p21 (Datto et al. 1997).

Although direct de-repression of cdc25A in TGFß cells by E1A has not yet been shown, E1A expression in virus-infected human fibroblasts leads to a rapid increase in cdc25A phosphatase activity and to an increase in cdc25A and cyclin E expression (Spitkovsky et al. 1996).

Human papillomavirus

Although the interactions of HPV E7 with Rb, p107 and p130 are well documented, other targets of the cell cycle machinery are appearing. E7 de-stabilizes Rb by inducing its degradation via a ubiquitin–proteosome pathway (Boyer et al. 1996). E7 expression can also rescue a cell cycle arrest induced by p21; two groups have shown that the ability of E7 to overcome a p21 arrest is not associated with an increase in cyclin-dependent kinase activity, implying that E7 does not directly affect p21-mediated cdk inhibitory function (Morozov et al. 1997; Ruesch & Laimins 1997). Reports from the laboratories of Karl Munger and Denize Galloway on the other hand indicate that E7 affects the activity of p21 through direct interaction, leading to an increase in cdk2-associated kinase activity (Funk et al. 1997;Jones et al. 1997). In a similar manner, E7 has been shown to antagonize the ability of p27 to inhibit cyclin E dependent kinase activity in vitro (Zerfass et al. 1996). The authors also report the association of E7 with p27, and suggest that the ability of E7 to overcome a G0/G1 arrest occurs by virtue of the interaction of E7 with the p27 CKI.

Ultimately, E7-induced disruption of Rb and CKI activity may result in de-regulation of cyclin expression, both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally. E7 expression leads to an elevation of cyclin E levels and cyclin E dependent kinase activity throughout the G1 phase correlating with a shortening of the G1 phase (Martin et al. 1998). Furthermore, Zerfass and colleagues demonstrate that E7 expression in NIH 3T3 cells leads to constitutive expression of the cyclin E and cyclin A genes accompanied by elevated cyclin-dependent kinase activity (Zerfass et al. 1995). Finally, E7 may mediate anchorage-independent growth of NIH 3T3 cells in suspension via activation of cyclin A expression and by preventing the inhibition of cyclin E dependent kinase activity (Schulze et al. 1998).

Recently, an important understanding of the mechanism by which E7 inactivates Rb-mediated repression has been revealed. The LXCXE motif (where letters represent the amino acid code and X represents any amino acid) is an Rb binding motif present in many Rb interacting proteins, including the cyclin D family and the small DNA tumour viral oncoproteins, adenovirus E1A, SV40 large T antigen and HPV E7.

Data indicates that the LXCXE motif present in E7 may compete for the LXCXE motif in HDAC for interaction with Rb, thereby displacing de-acetylase activity from Rb (Brehm et al. 1998). Interestingly, an Rb mutant without the LXCXE binding site is resistant to inactivation by E7 but not by cyclin D/cdk4. This Rb mutant still retains its ability to interact with HDAC and E2F and can repress transcription, demonstrating that the viral gene product relies upon this interaction for its activity to a greater extent than cellular proteins containing this motif (Dick et al. 2000).

The interaction of E7 with Rb is not sufficient for E7-induced transformation, since mutations in the zinc finger domain of E7, which is not involved in the Rb interaction, abrogate its transforming ability. E7 has been shown to interact directly with a component of the NURD histone deacetylase complex, Mi2beta via the zinc finger of E7 (Brehm et al. 1999). Mutational analysis of this zinc finger domain has demonstrated that a mutant that is unable to bind Mi2beta but retaining its Rb binding ability, fails to overcome cell cycle arrest.

In vivo, models have demonstrated that the HPV's ability to circumvent CKI's is likely to be important in cervical lesions; a G1 block can be overcome despite high levels of p21 and p27. Indeed, this phenomenon was most marked in lesions with the highest expected viral turnover, condylomata accuminata (Zehbe et al. 1999).

Recently, the importance of cyclin/cdk activity in promoting human papilloma viral replication was emphasized by studies from Ma et al. The group identified an HPV-encoded DNA replication initiation protein E1 that interacts with cyclin E via an RXL motif in E1 (now recognized as the minimal amino acid requirement for a productive interaction with the acidic surface residues of the cyclin subunit) (Ma et al. 1999). E1 acts as a substrate of cyclin E/cdk2, and its productive interaction and subsequent phosphorylation is likely to be necessary for viral DNA synthesis. That cyclin E/cdk 2 activity is important for viral DNA synthesis is clear, but what is fascinating is that the HPV E1 replication protein may interact with the same site on the cyclin subunit used by the p21 family of inhibitors to inactivate the cyclin/cdk holoenzyme. This implies that by competing with the inhibitor for cyclin interaction, the viral protein indirectly activates the cyclin/cdk for its subsequent phosphorylation and activation of viral DNA replication.

Human herpesviruses

Herpes simplex virus-1

HSV-1 Infected Cell Protein 0 is a promiscuous gene transactivator and has been shown to interact with cyclin D3 (Kawaguchi et al. 1997), an interaction which may stabilize cyclin D3 without affecting its ability to activate cdk4. Recombinant virus with a mutation in ICP0 that abrogates binding to cyclin D3 is deficient in replication in contact-inhibited human fibroblasts but not in dividing cells. Interestingly, when inoculated into mice, the mutant virus was significantly less neuroinvasive than wild type virus (Van Sant et al. 1999). This indicates that the virus targets cyclin D3 by stabilizing the protein, leading to enhanced viral replication in resting cells and increased neuroinvasiveness.

Epstein Barr virus

The gamma-1-herpesvirus, EBV has been shown by several groups to corrupt cell cycle regulators. Expression levels of cdc-2, cyclin E and cyclin D2 are increased approximately 100-fold as a result of EBV-mediated immortalization (Hollyoake et al. 1995). Interestingly, the up-regulation of cyclin D2 can occur through expression of three EBV immortalizing proteins, EBNA2 and EBNALP (Sinclair et al. 1994; Arvanitakis, 1995). Furthermore LMP1 is able to disrupt TGF beta signalling and concomitant Rb dephosphorylation (Arvanitakis et al. 1995).

Another transforming protein, EBNA3C, may function in a manner similar to the small DNA tumour viral proteins in binding to the pocket region of Rb, thereby inactivating its cell cycle inhibitory function (Parker et al. 1996). EBNA3C has also been shown to inhibit the accumulation of p27 and trigger nuclear division without cytokinesis leading to multinucleated cells (Parker et al. 2000). The BRLF1 gene product, Rta, is a transactivator. Rta is capable of activating lytic gene expression in epithelial cells. Rta binds an amino-terminal region of Rb, outside the pocket domain, after induction of the lytic switch. This binding correlates with release of E2F-1 from Rb (Zacny et al. 1998). Interestingly, the EBV-encoded DNA polymerase promoter is activated by Rta through transcription factors USF and E2F (Liu et al. 1996). EBNALP is also reported to interact with Rb in vitro and localize with Rb in the cell (Szekely et al. 1993).

Intriguingly, EBV encodes factors capable of arresting the cell cycle as well as precipitating its progression. The lytic switch transactivator Zta (also known as BZLF1) is capable of causing a G0/G1 arrest in several epithelial tumour cell lines (Cayrol & Flemington 1996a). Expression of Zta results in increased levels of p21 and p27 and hypophosphorylated Rb. This growth inhibitory effect of Zta is dependent on a carboxy-terminal region incorporating its bZIP domain (Cayrol & Flemington 1996b). The authors speculate that the Zta growth arrest function may function to redirect epithelial cell physiology to enhance the viral replicative program.

Therefore this herpesvirus has acquired functions that manipulate the cell cycle in an antagonistic fashion. Inactivation of the Rb protein in latent B cells may expand the infected B-cell number. Conversely, it has been proposed that viral replication in a G0 state may alleviate competition from the host cell for precursors of DNA synthesis, since the EBV genome contains many of the genes required for genome replication.

Human cytomegalovirus

The observation that cdk2 activity is necessary to fulfil HCMV DNA replication underscores the importance of subverting cell cycle control mechanisms in initiating viral DNA synthesis (Bresnahan et al. 1997). HCMV encodes many activities known to corrupt the cell cycle machinery. Early after HCMV infection, Rb becomes hyperphosphorylated and cyclin E levels and cyclin E-dependent kinase activity increase (Jault et al. 1995). Interestingly, within 24 h of HCMV infection, cdk2 translocates from the cytoplasm of contact-inhibited or serum-deprived cells into the nucleus correlating with the increase in cyclin E/cdk2 activity (Bresnahan et al. 1997). Indeed the same group report that HCMV infection results in activation of only some of the regulators of G1 phase progression; cyclin A and cyclin D induction does not occur, leading to an arrest in late G1, which the authors speculate allows unrestricted access to the precursors of viral replication whilst avoiding host cell DNA synthesis (Bresnahan et al. 1996).

Recently, two immediate early HCMV proteins IE72 and IE86 have been shown to have significant activities in the G1 phase. IE72 was shown to exhibit kinase activity towards E2F's 1,2 and 3 and pocket proteins, p107 and p130. Phosphorylation of E2F-1 has previously been shown to disrupt the interaction with pocket protein members, releasing E2F from pocket protein mediated repression (Fagan et al. 1994). Moreover, the kinase activity of IE72 was shown to be essential for activation of a DHFR (E2F-1 dependent) promoter (Pajovic et al. 1997). IE72 interacts directly with p107, overcomes transcriptional repression by p107 on an E2F promoter and is capable of circumventing a p107-mediated growth arrest (Poma et al. 1996; Johnson et al. 1999).

IE86 has been shown to interact with nucleotide sequences within the cyclin E promoter, necessary for the induction of cyclin E expression. Mutation of the known E2F sites within the cyclin E promoter does not inhibit the activation of cyclin E by IE86 (Bresnahan et al. 1998). Conversely, McElroy et al. have shown that expression of IE72 or IE86 either alone or together cannot induce cyclin E expression. They conclude that an altered E2F-4-DP-1-p130 complex together with viral early gene expression is necessary for cyclin E transcriptional up-regulation in HCMV infection (McElroy et al. 2000).

Gamma-2 herpesviruses

The gamma herpesviruses, herpesvirus saimiri (HVS), human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8 also known as Kaposi's Sarcoma associated herpesvirus, KSHV), mouse herpesvirus-68 (MHV-68) and herpesvirus ateles (HVA) are all known to encode genes exhibiting closest homology to the d-type cyclins. The first viral cyclin to be identified was found in HVS (Nicholas et al. 1992). Subsequent experiments revealed that V-cyclin was found to associate predominantly with cdk6 in COS-1 cells, and V–cyclin/cdk6 complexes strongly phosphorylated Rb fusion protein and histone H1 substrates in vitro (Jung et al. 1994). The authors concluded that V-cyclin differs from cellular d-type cyclins in at least two respects; firstly V-cyclin was found to associate almost exclusively with cdk6, whereas d-type cyclins have been shown to associate with four different cdks and secondly, the kinase activity of V-cyclin/cdk6 appeared to be much greater than cyclin D1/cdk6. The authors argue that cdk6 activation is physiologically important since HVS is known to transform cells of lymphoid origin in which cyclin D/cdk6 activity predominates over cyclin D/cdk4.

The discovery of a viral cyclin (denoted K-cyclin) encoded in ORF72 of HHV-8 was interesting since genomic sequencing had failed to identify sequence similarity to genes of EBV or HVS known to have important oncogenic functions (Chang et al. 1996). It was demonstrated that K-cyclin is capable of phosphorylating Rb in vitro and in vivo, and is capable of overcoming an Rb-induced arrest in SAOS-2 osteosarcoma cells (Chang et al. 1996). Further studies revealed that K-cyclin resembles V-cyclin in its ability to strongly associate with cdk6 in COS cells and in its ability to activate cdk6 leading to the phosphorylation of Rb and histone H1 substrates (Li et al. 1997). Furthermore, Godden-Kent and colleagues showed that although K-cyclin associates predominantly with cdk6 in COS cells, it is also capable of activating cdk4 in baculovirus-infected Sf9 extracts (Godden-Kent et al. 1997). The authors argued that K-cyclin, like V-cyclin, is capable of phosphorylating both Rb and histone H1 through cdk6 and therefore exhibits broader substrate specificity than cyclin D1/cdk6 complexes which phosphorylate Rb only. This may also indicate that K- and V-cyclin are capable of targeting substrates necessary for progression through later phases of the cell cycle.

The viral cyclin is extraordinary in its ability to evade inhibition by both p21 and p16 family members (Swanton et al. 1997). Evasion of p21 family members results from mutations of surface amino acids of the viral cyclin in the region involved in the interaction with p21 family members as well as conformational changes in the cyclin structure thought to lead to a steric clash with the p27 peptide (Schulze-Gahmen et al. 1999; Swanton et al. 1999; Card et al. 2000).

Recent results also demonstrate that HHV-8 K-cyclin directs the phosphorylation of p27 which leads to the destruction of the inhibitor (Ellis et al. 1999; Mann et al. 1999). This represents a novel feature of the viral cyclin, namely their ability to broaden the substrate specificity of cdk6 leading to phosphorylation of the cell cycle regulators, p27, cdc25A and Id-2 (for reviews see Swanton et al. 1999; Laman et al. 2000).

Circumventing inhibition by p16 by K-cyclin was surprising since this inhibitor interacts with the cdk only and not the cyclin subunit. We and colleagues speculate that K-cyclin induces a conformational change in cdk6 which p16 fails to reverse (Schulze-Gahmen et al. 1999; Swanton et al. 1999).

Other studies of K-cyclin have revealed its ability to activate cyclin A gene expression in quiescent cells, dependent on cdk6 activity and E2F target sequences in the cyclin A promoter (Duro et al. 1999). K-cyclin also induces apoptosis, dependent on cdk6 activity. Apoptosis was inhibited by concomitant expression of the HHV-8 antiapoptotic Bcl2 homologue, but not cellular Bcl2 (Ojala et al. 1999).

Accumulating evidence suggests that K-cyclin is expressed in both the latent and the lytic cycles of the viral life cycle (Davis et al. 1997; Sarid et al. 1998). Furthermore, Sarid and colleagues demonstrate that expression of K-cyclin is cell cycle regulated and mimics cellular D-type cyclin expression (Sarid et al. 1999).

Understanding the function of the virally encoded cyclin has provoked an exciting problem in the biology of the gammaherpesvirus. What is the reason for the expression of such a potent regulator of the cell cycle during viral latency? Although inactivation of Rb or CKI proteins during lytic viral replication is advantageous to viral genome replication, the role of Rb inactivation in latency remains uncertain. In this light, Chang and Moore suggest that cell cycle arrest during virus latency acts as an anti-viral mechanism to limit latent virus replication (Moore & Chang 1998).

An alternative explanation is that expression of K-cyclin in latency serves to uncouple the relationship between cellular differentiation and cell cycle exit. Recently, two virally encoded proteins have been proposed to function in a similar manner. The avian retrovirus encoded protein v-Myb was shown to repress transcription, dependent on the prior association with cyclin D1 or D2 (Ganter et al. 1998). The authors conclude that this interaction represses the monoblast-macrophage differentiation pathway. In addition, E7 has been shown to uncouple cellular differentiation and proliferation in human keratinocytes (Jones et al. 1997). Although keratinocyte differentiation was not substantially altered, DNA synthesis remained elevated upon E7 expression. The authors propose that this may derive, in part, from the interaction of E7 with p21 resulting in the elevation of cdk2-dependent kinase activity.

Although K-cyclin may not be performing an active role in arresting a differentiation pathway, its expression may be capable of uncoupling DNA synthesis from differentiation. A more active role in arresting differentiation should not be excluded, since cyclin D1 expression can inhibit differentiation of immature myoblasts, an effect not seen with cyclins A or E (Skapek et al. 1995). The first clue to a role in disrupting a differentiation pathway is revealed by work that demonstrates that ectopic expression of the MHV 68 encoded M-cyclin in T cells, interferes with the T-cell differentiation pathway leading to an increase in CD4 + CD8 + thymocytes (Vandyk et al. 1999).

It is becoming evident that virally encoded cyclins may not necessarily be performing equivalent roles in the biology of the gamma herpesvirus. In contrast to HHV-8 K-cyclin, the Mouse Herpesvirus 68 encoded cyclin (M-cyclin) is a lytically expressed gene. Despite the difference in their expression, work from our laboratory has demonstrated that both K- and M-cyclins evade p27-mediated inhibition. Studies in transgenic mice engineered to ectopically express M-cyclin in B and T cells have revealed that nearly 50% of mice develop high grade immunoblastic lymphoma, the first study demonstrating the oncogenic role of a virally encoded cyclin (Vandyk et al. 1999).

Human retroviruses

Human T cell leukaemia virus-1

HTLV-1 protein, TAX, has been shown to bind p16 and prevent its inhibition of cyclin D activity, leading to a reversal of a p16-induced G1 phase arrest (Suzuki et al. 1996; Low et al. 1997). Furthermore, TAX can interact with another member of the p16 family, p15, thereby inactivating its function and restoring cdk4 activity (Suzuki et al. 1999). Intriguingly, TAX does not interact with the other two members of the p16 family, p18 and p19; instead, TAX transcriptionally represses p18 (Suzuki et al. 1999).

Recent work indicates that TAX can also promote cell cycle progression independently of its ability to inactivate p16 (Lemasson et al. 1998; Neuveut et al. 1998): TAX activates the E2F promoter partly dependent on ATF sites adjacent to the gene. Reminiscent of the interaction of HSV-1 encoded ICP0 with cyclin D3, TAX also forms a complex with cyclin D3. It is not known whether this interaction is responsible for the associated increase in cyclin D/cdk activity observed in these studies (Neuveut et al. 1998).

Human immunodeficiency virus

The Vpr accessory gene product of HIV types 1 and 2 leads to an arrest at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (Re et al. 1995; Rogel et al. 1995; Bartz et al. 1996). Cyclin B/cdc2 complexes drive the progression from G2 to M phase after dephosphorylation of two regulatory amino acids of cdc2 (Thr-14 and Tyr-15). Vpr has been shown to prevent the activation of the cyclin B/cdc2 complex: Vpr expression in cells maintained cdc2 in the phosphorylated, inactive state (He et al. 1995). The authors speculate that this arrest may delay or prevent apoptosis of infected cells, thereby increasing the amount of virus produced by each infected cell.

Recent data has established a mechanistic principle for understanding the role of Vpr in HIV replication; Vpr co-operates with the transcriptional coactivator p300 to increase HIV gene expression via an interaction mediated by p300 between NF-kappaB and cyclin B1/cdc2 (Felzien et al. 1998). The authors suggest this increases viral replication after growth arrest by enhancing viral transcription. Elaborating on this theme, the expression of the viral genome is optimal in the G2 phase of the cell cycle, and Vpr increases virus production by delaying cells at the point where the long-terminal repeat is most active, thereby maximizing virus production (Goh et al. 1998).

HIV-1 encoded Tat may function to arrest glial cells in the G1 phase. Tat induces a G1 arrest in the human astrocytic line, U-87MG. This correlated with lowered cyclin E/cdk2 activity and phosphorylated Rb (Kundu et al. 1998). The authors also observed that the underphosphorylated Rb present in Tat-treated cells promotes HIV-1 transcription dependent on the NF-kappaB enhancer region. Tat may also interfere with the G1/S checkpoint after gamma radiation of HIV-1 infected cells. This correlates with reduced p21 levels and an increase in cyclin E/cdk2 activity. The authors propose that this phenomenon may in part be due to the ability of Tat to interact with p53 and alter p53-dependent p21 transactivation (Clark et al. 2000).

Conclusions

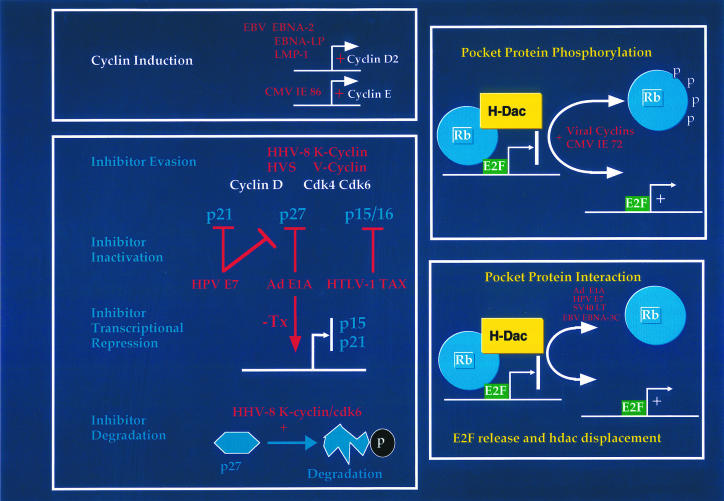

That mammalian cell cycle regulators are such frequent targets of viral disruption is a tribute in itself to the importance of the mammalian proteins in their control of the cell division cycle. Early work investigating the disruption of the pocket protein family by the small DNA tumour viral gene products has opened up an exciting field revealing how vulnerable both negative and positive regulators of the mammalian cell cycle are to disruption, mimicry (in the case of the viral cyclins) and inactivation (Figure 2). It is certain that many intriguing viral strategies have yet to be unravelled as new cell cycle regulators are cloned and viruses sequenced.

Figure 2.

Viral strategies for deregulating the restriction point. A number of different strategies are employed by different DNA tumour viruses to interfere with regulators of the restriction point. Some viral encoded products activate the expression of positive regulators of G1 progression such as cyclin D2 and cyclin E. Other viral products interfere with the normal function of the negative regulator pRb either through promoting phosphorylation of pRb or through direct interaction with pRb. Finally, a number of viral products alter the levels of, or inhibit the activity of, the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors such as p16, p15, p21 and p27.

References

- Abraham SE, Carter MC, Moran E. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF beta 1) reduces cellular levels of p34cdc2, and this effect is abrogated by adenovirus independently of the E1A-associated pRB binding activity. Mol. BiolCell. 1992;3:655–665. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis L, Yaseen N, Sharma S. Latent membrane protein-1 induces cyclin D2 expression, pRb hyperphosphorylation, and loss of TGF-beta 1-mediated growth inhibition in EBV-positive B cells. JImmunol. 1995;155:1047–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartz SR, Rogel ME, Emerman M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cell cycle control: Vpr is cytostatic and mediates G2 accumulation by a mechanism which differs from DNA damage checkpoint control. JVirol. 1996;70:2324–2331. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2324-2331.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer SN, Wazer DE, Band V. E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4620–4624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm A, Miska E, McCance D, Reid J, Bannister A, Kouzarides T. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature. 1998;391:597–601. doi: 10.1038/35404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm A, Nielsen SJ, Miska EA, et al. The E7 oncoprotein associates with Mi2 histone deacetylase activity to promote cell growth. EMBO J. 1999;18:2449–2458. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan WA, Boldogh I, Thompson EA, Albrecht T. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits cellular DNA synthesis and arrests productively infected cells in late G1. Virology. 1996;224:150–160. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan WA, Boldogh I, Chi P, Thompson EA, Albrecht T. Inhibition of cellular Cdk2 activity blocks human cytomegalovirus replication. Virology. 1997a;231:239–247. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan WA, Thompson EA, Albrecht T. J Gen Virol. 1997b. Human cytomegalovirus infection results in altered Cdk2 subcellular localization; pp. 1993–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan WA, Albrecht T, Thompson EA. The Cyclin E Promoter Is Activated by Human Cytomegalovirus 86-Kda Immediate Early Protein. JBiolChem. 1998;273:22075–22082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.22075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card GL, Knowles P, Laman H, Jones N, Mcdonald NQ. Crystal structure of a gamma-herpesvirus cyclin-cdk complex. EMBO J. 2000;19:2877–2888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayrol C, Flemington EK. The Epstein-Barr virus bZIP transcription factor Zta causes G0/G1 cell cycle arrest through induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. EMBO J. 1996a;15:2748–2759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayrol C, Flemington E. G0/G1 growth arrest mediated by a region encompassing the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domain of the Epstein-Barr virus transactivator Zta. JBiolChem. 1996b;271:31799–31802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Moore PS, Talbot SJ, et al. Cyclin encoded by KS herpesvirus. Nature. 1996;382:410. doi: 10.1038/382410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark E, Santiago F, Deng L, et al. Loss of G (1) /S checkpoint in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected cells is associated with a lack of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21/Waf1. JVirol. 2000;74:5040–5052. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5040-5052.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datto MB, Li Y, Panus JF, Howe DJ, Xiong Y, Wang XF. Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 1995;92:5545–5549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datto M, Pei-Chih Hu P, Kowalik T, Yingling J, Wang X-F. The Viral Oncoprotein E1A Blocks Transforming Growth Factor Beta-Mediated Induction of p21/WAF1/Cip1 and p15/INK4B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:2030–2037. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MA, Sturzl MA, Blasig C, et al. Expression of human herpesvirus 8-encoded cyclin D in Kaposi's sarcoma spindle cells [see comments] JNatlCancer Inst. 1997;89:1868–1874. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.24.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick FA, Sailhamer E, Dyson NJ. Mutagenesis of the pRB pocket reveals that cell cycle arrest functions are separable from binding to viral oncoproteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:3715–3727. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3715-3727.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duro D, Schulze A, Vogt B, Bartek J, Mittnacht S, Jansen-Durr P. Activation of cyclin A gene expression by the cyclin encoded by human herpesvirus-8. JGen Virol. 1999;80:549–555. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-3-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis M, Chew YP, Fallis L, et al. Degradation of p27 (Kip) cdk inhibitor triggered by Kaposi's sarcoma virus cyclin-cdk6 complex. EMBO J. 1999;18:644–653. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan R, Flint K, Jones N. Phosphorylation of E2F-1 modulates its interaction with the retinoblastoma gene product and the adenoviral E4 19 kDa protein. Cell. 1994;78:799–811. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felzien LK, Woffendin C, Hottiger MO, Subbramanian RA, Cohen EA, Nabel GJ. HIV transcriptional activation by the accessory protein, VPR, is mediated by the p300 co-activator. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 1998;95:5281–5286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk JO, Waga S, Harry JB, Espling E, Stillman B, Galloway DA. Inhibition of CDK activity and PCNA-dependent DNA replication by p21 is blocked by interaction with the HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2090–2100. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaktionov K, Beach D. Specific activation of cdc25 tyrosine phosphatase by B-type cyclins: evidence for multiple roles of mitotic cyclins. Cell. 1991;67:1181–1194. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaktionov K, Lee AK, Eckstein J, et al. CDC25 phosphatases as potential human oncogenes. Science. 1995;269:1575–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.7667636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganter B, Fu S-L, Lipsick J. d-type cyclins repress transcriptional activation by the V-Myb but not the C-Myb DNA-binding domain. EMBO J. 1998;17:255–268. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier J, Solomon MJ, Booher RN, Bazan JF, Kirschner MW. cdc25 is a specific tyrosine phosphatase that directly activates p34cdc2. Cell. 1991;67:197–211. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90583-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godden-Kent D, Talbot S, Boshoff C, et al. The cyclin encoded by Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus stimulates cdk6 to phosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein and histone H1. JVirol. 1997;71:4193–4198. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4193-4198.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh WC, Rogel ME, Kinsey CM, et al. HIV-1 Vpr increases viral expression by manipulation of the cell cycle: a mechanism for selection of Vpr in vivo. Nature Med. 1998;4:65–71. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould KL, Nurse P. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the fission yeast cdc2+ protein kinase regulates entry into mitosis. Nature. 1989;342:39–45. doi: 10.1038/342039a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Bates S, Peters G. Evidence for different modes of action of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors: p15 and p16 bind to kinases, p21 and p27 bind to cyclins. Oncogene. 1995;11:1581–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon GJ, Beach D. p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGF-beta-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature. 1994;371:257–261. doi: 10.1038/371257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell LH, Kastan MB. Cell Cycle Control and Cancer. Science. 1994;266:1821–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7997877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Choe S, Di Walker RM.P, Morgan DO, Landau NR. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. JVirol. 1995;69:6705–6711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6705-6711.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helin K, Harlow E. The Retinoblastoma Protein as a Transcriptional Repressor. Trends Cellular Biology. 1993;3:43–46. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(93)90150-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollyoake M, Stuhler A, Farrell P, Gordon J, Sinclair A. The normal cell cycle activation program is exploited during the infection of quiescent B lymphocytes by Epstein-Barr virus. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4784–4787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavarone I, Massague J. Repression of the CDK activator Cdc25a and cell-cycle arrest by cytokine TGF-beta in cells lacking the CDK inhibitor p15. Nature. 1997;387:417–422. doi: 10.1038/387417a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jault FM, Jault JM, Ruchti F, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection induces high levels of cyclins, phosphorylated Rb, and p53, leading to cell cycle arrest. JVirol. 1995;69:6697–6704. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6697-6704.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RA, Yurochko AD, Poma EE, Zhu L, Huang ES. Domain mapping of the human cytomegalovirus IE1–72 and cellular p107 protein–protein interaction and the possible functional consequences. J. Gen. Virol. 80:1293–303. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-5-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Alani RM, Munger K. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein can uncouple cellular differentiation and proliferation in human keratinocytes by abrogating p21Cip1-mediated inhibition of cdk2. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2101–2111. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JU, Stager M, Desrosiers RC. Virus-encoded cyclin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:7235–7244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koff A, Ohtsuki M, Polyak K, Roberts JM, Massague J. Negative regulation of G1 in mammalian cells: inhibition of cyclin E-dependent kinase by TGF-beta. Science. 1993;260:536–539. doi: 10.1126/science.8475385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krek W, Nigg EA. Mutations of p34cdc2 phosphorylation sites induce premature mitotic events in HeLa cells: evidence for a double block to p34cdc2 kinase activation in vertebrates. EMBO J. 1991;10:3331–3341. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krude T, Jackman M, Pines J, Laskey R. Cyclin/Cdk-Dependent Initiation of DNA Replication in a Human Cell-Free System. Cell. 1997;88:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu M, De Sharma SL.A, et al. HIV-1 Tat elongates the G1 phase and indirectly promotes HIV-1 gene expression in cells of glial origin. JBiolChem. 1998;273:8130–8136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laman H, Mann DJ, Jones NC. Viral-encoded cyclins. Current Opinion Genet Dev. 2000;10:70–74. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauper N, Beck AR, Cariou S, et al. Cyclin E2: a novel CDK2 partner in the late G1 and S phases of the mammalian cell cycle. Oncogene. 1998;17:2637–2643. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemasson I, Thebault S, Sardet C, Devaux C, Mesnard JM. Activation of E2F-mediated transcription by human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax protein in a p16 (INK4A) -negative T-cell line. JBiolChem. 1998;273:23598–23604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew DJ, Kornbluth S. Regulatory roles of cyclin dependent kinase phosphorylation in cell cycle control. Current Opinion Cell Biol. 1996;8:795–804. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Lee H, Yoon D-W, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes a functional cyclin. JVirol. 1997;71:1984–1991. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1984-1991.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Sista ND, Pagano JS. Activation of the Epstein-Barr virus DNA polymerase promoter by the BRLF1 immediate-early protein is mediated through USF and E2F. JVirol. 1996;70:2545–2555. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2545-2555.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low KG, Dorner LF, Fernando DB, Grossman J, Jeang KT, Comb MJ. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax releases cell cycle arrest induced by p16INK4a. JVirol. 1997;71:1956–1962. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1956-1962.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg AS, Weinberg RA. Functional inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein requires sequential modification by at least two distinct cyclin-cdk complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:753–761. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo RX, Postigo AA, Dean DC. Rb interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Cell. 1998;92:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80940-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Zou N, Lin BY, Chow LT, Harper JW. Interaction between cyclin-dependent kinases and human papillomavirus replication-initiation protein E1 is required for efficient viral replication. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 1999;96:382–387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi-Jaulin L, Groisman R, Naguibneva I, et al. Retinoblastoma protein represses transcription by recruiting a histone deactylase. Nature. 1998;391:601–605. doi: 10.1038/35410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mal A, Poon RY, Howe PH, Toyoshima H, Hunter T, Harter ML. Inactivation of p27Kip1 by the viral E1A oncoprotein in TGFbeta-treated cells. Nature. 1996;380:262–265. doi: 10.1038/380262a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann DJ, Child ES, Swanton C, Laman H, Jones NC. Modulation of p27kip1 levels by the cyclin encoded by Kaposi's Sarcoma associated herpesvirus. EMBO J. 1999;18:654–663. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LG, Demers GW, Galloway DA. Disruption of the G1/S transition in human papillomavirus type 16, E7–expressing human cells is associated with altered regulation of cyclin E. J Virol. 1998;72:975–85. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.975-985.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy AK, Dwarakanath RS, Spector DH. Dysregulation of cyclin E gene expression in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells requies viral early gene expression and is associated with changes in the Rb-related protein p130. JVirol. 2000;74:4192–4206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4192-4206.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PS, Chang Y. Antiviral activity of tumor suppressor pathways: clues from molecular piracy by KSHV. Trends Genet. 1998;14:144–150. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov A, Shiyanov P, Barr E, Leiden J, Raychaudhuri P. Accumulation of human papillomavirus type 16, E7 protein bypasses G1 arrest induced by serum deprivation and by the cell cycle inhibitor p21. J Virol. 1997;71:3451–3457. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3451-3457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuveut C, Low KG, Maldarelli F, et al. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax and cell cycle progression: role of cyclin d-cdk and p110Rb. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:3620–3632. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas J, Cameron KR, Honess RW. Herpesvirus saimiri encodes homologues of G protein-coupled receptors and cyclins. Nature. 1992;355:362–365. doi: 10.1038/355362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura H, Sawada Y, Ohtaki S. Interaction of p27 with E1A and its effect on CDK kinase activity. BiochemBiophysResCommun. 1998;248:228–234. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojala PM, Tiainen M, Salven P, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encoded V-cyclin triggers apoptosis in cells with high levels of cyclin-dependent kinase 6. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4984–4989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajovic S, Wong E, Black A, Azizkhan J. Identification of a viral kinase that phosphorylates specific E2Fs and pocket proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:6459–6464. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee A. A restriction point for control of normal animal cell proliferation. ProcNatAcadSciUSA. 1974;71:1286–1290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker GA, Crook T, Bain M, Sara EA, Farrell PJ, Allday MJ. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA) 3C is an immortalizing oncoprotein with similar properties to adenovirus E1A and papillomavirus E7. Oncogene. 1996;13:2541–2549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker GA, Touitou R, Allday MJ. Epstein-Barr virus EBNA3C can disrupt multiple cell cycle checkpoints and induce nuclear division divorced from cytokinesis. Oncogene. 2000;19:700–709. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, Lee MH, Erdjument‐Bromage H, et al. Cloning of p27Kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and a potential mediator of extracellular antimitogenic signals. Cell. 1994a;78:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, Kato JY, Solomon MJ, et al. p27Kip1, a cyclin-Cdk inhibitor, links transforming growth factor-beta and contact inhibition to cell cycle arrest. Genes Dev. 1994b;8:9–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poma EE, Kowalik TF, Zhu L, Sinclair JH, Hunag ES. The human cytomegalovirus IE1–72 protein interacts with the cellular p107 protein and relieves p107-mediated trasncriptional repression of an E2F-responsive promoter. JVirol. 1996;70:7867–7877. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7867-7877.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon RY, Hunter T. Dephosphorylation of Cdk2 threonine 160 by the cyclin-dependent kinase-interacting phosphatase KAP in the absence of cyclin. Science. 1995;270:90–93. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re F, Braaten D, Franke EK, Luban J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle in G2 by inhibiting the activation of p34cdc2-cyclin B. JVirol. 1995;69:6859–6864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6859-6864.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogel ME, Wu LI, Emerman M. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr gene prevents cell proliferation during chronic infection. JVirol. 1995;69:882–888. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.882-888.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruesch MN, Laimins L. Initiation of DNA synthesis by human papillomavirus E7 oncoproteins is resistant to p21-mediated inhibition of cyclin E-cdk2 activity. JVirol. 1997;71:5570–5578. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5570-5578.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarid R, Flore O, Bohenzky RA, Chang Y, Moore PS. Transcription mapping of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genome in a body cavity-based lymphoma cell line (BC-1) JVirol. 1998;72:1005–1012. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1005-1012.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarid R, Wiezorek JS, Moore PS, Chang Y. Characterization and cell cycle regulation of the major Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) latent genes and their promoter. JVirol. 1999;73:1438–1446. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1438-1446.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze A, Mannhardt B, Zerfass TK, Zwerschke W, Jansen DP. Anchorage-independent transcription of the cyclin A gene induced by the E7 oncoprotein of human papillomavirus type 16. JVirol. 1998;72:2323–2334. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2323-2334.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Gahmen U, Jung JU, Sung-Hou K. Crystal structure of a viral cyclin, a positive regulator of cyclin-dependent kinase 6. Structure. 1999;7:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan F, Seghezzi W, Parry D, Mahony D, Lees E. Cyclin E associates with BAF155 and BRG-1, components of the mammalian SWI-SNF complex, and alters the ability of BRG1 to induce growth arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:1460–1469. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simanis V, Nurse P. The cell cycle control gene cdc2+ of fission yeast encodes a protein kinase potentially regulated by phosphorylation. Cell. 1986;45:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair AJ, Palmero I, Peters G, Farrell PJ. EBNA-2 and EBNA-LP cooperate to cause G0 to G1 transition during immortalization of resting human B lymphocytes by Epstein-Barr virus. EMBO J. 1994;13:3321–3328. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skapek SX, Rhee J, Spicer DB, Lassar AB. Inhibition of myogenic differentiation in proliferating myoblasts by cyclin D1-dependent kinase. Science. 1995;267:1022–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.7863328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitkovsky D, Jansen DP, Karsenti E, Hoffman I. S-phase induction by adenovirus E1A requires activation of cdc25a tyrosine phosphatase. Oncogene. 1996;12:2549–2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Kitao S, Matsushime H, Yoshida M. HTLV-1 Tax protein interacts with cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16ink4a and counteracts its inhibitory activity towards CDK4. EMBO J. 1996;15:1607–1614. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Narita T, Uchida-Toita M, Yoshida M. Down-regulation of the INK4 family of cyclin-dependent kinse inhibitors by tax protein of HTLV-1 through two distinct mechanisms. Virology. 1999;259:384–391. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanton C, Mann DJ, Fleckenstein B, Neipel F, Peters G, Jones NC. Viral cyclin/cdk6 complexes evade inhibition by cdk inhibitory proteins. Nature. 1997;390:184–187. doi: 10.1038/36606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanton C, Card G, Mann D, Mcdonald N, Jones N. Overcoming Inhibitions: HHV-8 encoded cyclin subversion of Cdk Inhibitory proteins. Trends BiochemSciences. 1999;24:116–120. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekely L, Selivanova G, Magnusson KP, Klein G, Wiman KG. EBNA-5, an Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen, binds to the retinoblastoma and p53 proteins. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 1993;90:5455–5459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelander L, Reichard P. Reduction of ribonucleotides. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1979;48:133–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandyk LF, Hess JL, Katz JD, Jacoby M, Speck SH, Virgin HW. The murine gammaherpesvirus 68 V-cyclin gene is an oncogene that promotes cell cycle progression in primary lymphocytes. JVirol. 1999;73:5110–5122. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5110-5122.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kawaguchi YS.C, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 alpha regulatory protein ICP0 interacts with and stabilizes the cell cycle regulator cyclin D3. JVirol. 1997;71:7328–7336. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7328-7336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sant C, Kawaguchi Y, Roizman B. A single amino acid substitution in the cyclin D binding domain of the infected cell protein no. 0 abrogates the neuroinvasiveness of herpes simplex virus without affceting its ability to replicate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:8184–8189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HG, Draetta G, Moran E. E1A induces phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein independently of direct physical association between the E1A and retinoblastoma products. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:4253–4265. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny VL, Wilson J, Pagano JS. The Epstein-Barr virus immediate early gene product, BRLF1, interacts with the retinoblastoma protein during the viral lytic cycle. JVirol. 1998;72:8043–8051. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8043-8051.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehbe I, Ratsch A, Alunni-Fabbroni M, et al. Overriding of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors by high and low risk human papillomavirus types: evidence for an in vivo role in cervical lesions. Oncogene. 1999;13:2201–2211. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerfass K, Schulze A, Spitkovsky D, Friedman V, Henglein B, Jansen DP. Sequential activation of cyclin E and cyclin A gene expression by human papillomavirus type 16, E7 through sequences necessary for transformation. J Virol. 1995;69:6389–99. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6389-6399.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerfass TK, Zwerschke W, Mannhardt B, Tindle R, Botz JW, Jansen DP. Inactivation of the cdk inhibitor p27KIP1 by the human papillomavirus type 16, E7 oncoprotein. Oncogene. 1996;13:2323–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HS, Gavin M, Dahiya A, et al. Exit from G1 and S Phase of the cell cycle is regulated by repressor complexes containing HDAC-Rb-hSWI/SNF and Rb-hSWI/SNF. Cell. 2000;101:79–89. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80625-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]