Abstract

While necrosis is known as a major mechanism for the loss of viability of skeletal muscle following ischaemia and reperfusion, much less is known of the role of apoptosis. In this study rat hind limbs were subjected to 2 h of tourniquet ischaemia, then reperfused for either 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 3, 8, 16 or 24 h (n = 6 per group). Mean viability of muscle, assessed by tetrazolium dye reduction, after 2 h ischaemia and 24 h reperfusion was 17%. Histological examination revealed disrupted, necrotic muscle fibres from 30 min to 24 h reperfusion. Apoptotic nuclei were identified by haematoxylin staining and TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP nick end labelling. No TUNEL-positive cells were observed at the end of the ischaemic period, but a small number of TUNEL-positive endothelial and smooth muscle cells were found at 30 min reperfusion, with a progressive increase in their number up to 24 h reperfusion. Apoptotic neutrophils were detected after 8–24 h reperfusion. At no stage was apoptosis seen in the nuclei of skeletal muscle fibres. It appears that apoptosis plays no role in the death of muscle fibres after ischaemia-reperfusion injury to skeletal muscle.

Keywords: apoptosis, necrosis, skeletal muscle cells, ischaemia-reperfusion, oxidative stress

Death of cells within living tissues may occur by either necrosis or apoptosis. These two processes have been shown to have fundamentally different morphological appearances, mechanisms and significance. For many years it was thought that apoptosis, then termed either karyorhexis or pyknosis, was restricted to the tissue remodelling that occurs during embryonic development and that loss of cells induced by injury, and in particular by ischaemia, invariably occurred by necrosis (Majno & Joris 1995).

However in 1971 it was observed that loss of cells in ischaemic atrophy of the liver occurred not by necrosis but in a manner similar to that seen in embryonic development (Kerr 1971). In later studies Kerr and colleagues showed the presence of this form of cell death in many pathological lesions, including neoplasms, and named the phenomenon apoptosis (Kerr 1971; Kerr et al. 1972). It is now known that apoptosis is an active process requiring RNA and protein synthesis and, while the precise mechanism varies in different tissues, many details of its metabolic process have been elucidated (reviewed in Haslett 1997). It has been shown that in apoptosis cleavage of DNA occurs in a characteristic and regulated manner which can be recognized histologically by the TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUPT nick end labelling) technique or biochemically by formation of a ladder pattern in PAGE (Gavrieli et al. 1992).

Ischaemia, with or without subsequent reperfusion, is a common and clinically important cause of injury in many tissues. Many aspects of its pathophysiological basis and morphology have been established but only recently has it been recognized that apoptosis may play a role in ischaemic injury (Fernandes & Cotter 1994). Apoptosis has been observed in hypoxic endothelial cells (Gobe et al. 1995), in cells subjected to oxidative stress (Buttke & Sandstrom 1994) and following ischaemia-reperfusion injury to the intestine (Horie et al. 1997), liver (Terao et al. 1997) and heart (Bielawska et al. 1997; Yue et al. 1998). At a cellular level, oxidative stress and altered calcium homeostasis are considered to be mediators of apoptosis, synergistically lowering the mitochondrial membrane potential and decreasing cellular ATP levels, thereby causing cell death (Richter et al. 1996). However no evidence is available of the role of apoptosis in ischaemia-reperfusion injury to skeletal muscle.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether apoptotic cells are visible in skeletal muscle during the first 24 h of reperfusion after tourniquet ischaemia of the hind limb of the rat.

Methods

Surgical model of ischaemia-reperfusion in rat gastrocnemius skeletal muscle

With the animal under general anaesthesia induced by sodium pentobarbitone (35 mg/kg), ischaemia was created by the application of a rubber band tourniquet (size 31, 7 turns) as high as possible on one hind limb of Sprague Dawley rats (250–300 g) of either sex. During tourniquet ischaemia, the animal was placed in a covered box and the muscle temperature was maintained at 36°C ± 1°C with the aid of a desk lamp. After 2 h of warm ischaemia, and with the rat still under general anaesthesia, reperfusion was initiated by removal of the rubber band and normal blood flow was allowed to continue for either 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 3, 8, 16 or 24 h. With the animal again under general anaesthesia, the medial gastrocnemius muscle was isolated, weighed and cross-sectioned into approximately eight 5 mm thick slices. For histological staining, each alternate muscle slice was fixed immediately in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate-buffered saline. The remaining muscle slices were weighed, frozen in liquid nitrogen and freeze dried for later biochemical analysis. For muscle viability studies (assessed only after 24 h reperfusion), slices were stained by the NBT technique as described below.

Skeletal muscle viability — histochemical assessment

Serial slices (5 mm thick) of the gastrocnemius muscle were incubated in Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT 0.033%) and NADH (0.133%) in 0.05 m sodium phosphate buffer for 10 min, and then fixed in buffered formol saline. The viable areas staining blue in each slice were measured using a Video Pro image analyser (Video Pro 32, Faulding Imaging, Clayton, Victoria, Australia) and results for all slices were averaged to give a percentage survival of the whole muscle. An appropriate time to assess muscle viability by this method has been shown to be after 24 h reperfusion (Hickey et al. 1992).

Histology

After fixation in buffered 4% paraformaldehyde slices were processed, embedded in paraffin, and 5 μm sections cut and alternate sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H & E) or by the TUNEL technique.

TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUPT nick end labelling) technique

DNA strand breaks in apoptotic cells as a result of endonuclease activity were labelled by the TUNEL technique (Gavrieli et al. 1992) using kits purchased commercially (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) and the label developed with horseradish peroxidase conjugated to streptavidin. Sections were stained lightly with haematoxylin to allow identification of structural features and to localize TUNEL staining to particular cell types such as endothelial cells, leucocytes and muscle fibres.

Biochemical analyses

Weighed segments of tissue were thawed, homogenized in ice-cold buffers, then used to determine each of the following parameters.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels, an estimate of the oxidant protection in the tissue, were measured on tissue homogenates by a spectrophotometric assay after incubation of the deproteinized tissue homogenates with Ellman's reagent (Sedlak & Lindsay 1968). Myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels, a measure of neutrophil infiltration into the tissue, were determined by the H202-dependent oxidation of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Kohout et al. 1995). Oedema was measured as the water content (wet — dry) per unit of dry weight of tissue. Wet tissue was weighed in preweighed tubes and a further weighing was made after 2 days of freeze drying (Hickey et al. 1992).

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean for n observations. Groups of data were analysed by one-way analysis of variance and the significance of individual comparisons was assessed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test (GraphPad Prism software, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). A difference was considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Muscle viability

As assessed by NBT-positive staining, the mean viability of muscle subjected to 2 h ischaemia and 24 h reperfusion was 17 ± 6% (n = 6).

Histological appearance

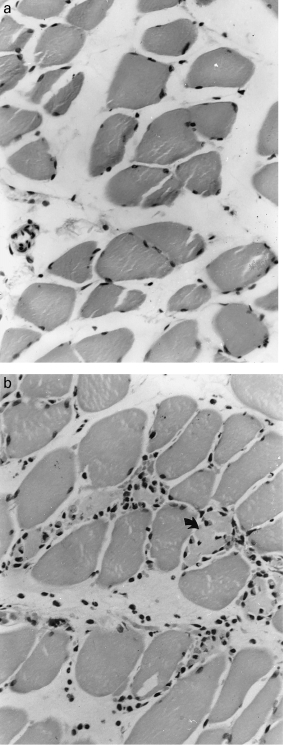

Immediately after 2 h ischaemia no histological abnormality is apparent (Figure 1a). After 30 min reperfusion the tissue is expanded by oedema and there is occasional pavementing of neutrophils in venules and small veins. Neutrophil pavementing increases progressively for the next few hours and by 8 h many neutrophils are present in extravascular tissues. Abnormalities in muscle fibres are clearly apparent at this stage. In the affected fibres the nuclei are unaltered but the cytoplasm appears hyaline, stains deeply with eosin and has few visible striations. These changes progress. After 24 h reperfusion the necrotic fibres are slightly smaller than viable fibres, contain no nuclei and have a somewhat granular cytoplasm with no visible striations. The interstitial tissues are distended by oedema and contain many neutrophils and macrophages. Leucocytes are also visible within the sarcolemma of some necrotic muscle fibres (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Cross sections of skeletal muscle after 2 h ischaemia. a, At the end of the ischaemic period muscle fibres are of normal appearance and contain numerous darkly staining peripheral nuclei. b, After 24 h reperfusion almost all muscle nuclei have disappeared. Numerous neutrophils and polymorphs are present in the interstitial tissues and within the sarcolemma of some necrotic fibres (↑). Haematoxylin and eosin (H & E) × 230.

In 24 h specimens the great majority of muscle fibres are necrotic. The surviving viable fibres are dispersed, apparently at random, between necrotic fibres with no variation in distribution pattern in the several slices examined from an individual muscle.

TUNEL staining

Control sections

Rat ovary was used as a positive control (Palumbo & Yeh 1994) and showed widespread nuclear staining within degenerating follicles. Negative controls of normal nonischaemic muscle and ischaemic-reperfused muscle in which biotinylated dUTP had been omitted from staining, showed no TUNEL positive nuclei.

Ischaemic-reperfused muscle

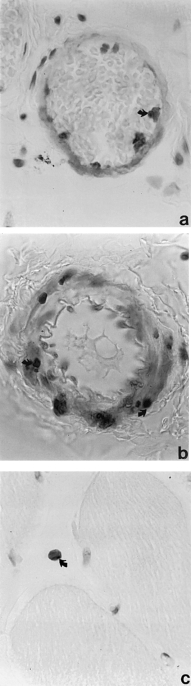

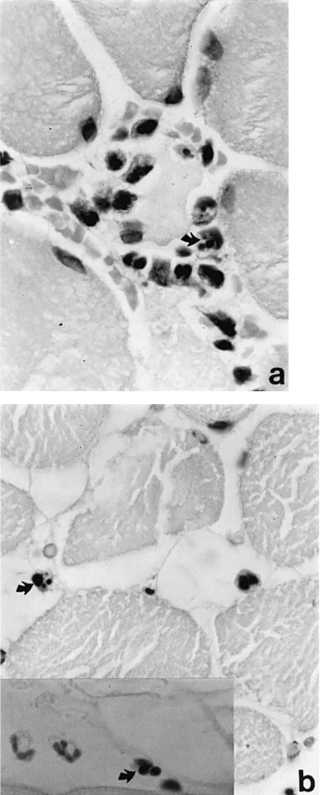

After 2 h ischaemia alone or 2 h ischaemia and 15 min reperfusion there is no positive staining. TUNEL positive cells are first seen within the wall of small blood vessels and in interstitial tissues after 30 min reperfusion and are visible in these situations at all later times examined. Comparison with adjacent sections stained with H & E shows that the TUNEL positive cells have the dark shrunken nuclei characteristic of apoptosis. In small blood vessels TUNEL staining is seen in both endothelial and medial smooth muscle cells (Figure 2a, b). Most positive cells in interstitial tissues, especially after longer periods of reperfusion, are neutrophils or macrophages. Other positive cells cannot be identified with certainty but appear to be capillary endothelial cells (Figures 2c and 3).

Figure 2.

Cross section of skeletal muscle after 2 h ischaemia and increasing periods of reperfusion. a, After 1 h reperfusion, TUNEL positive nuclei (↑) are visible in the endothelium of a small vessel. b and c, After 8 h reperfusion TUNEL positive nuclei are visible in (b) the media of an arteriole and in (c) an isolated cell in the interstitial tissue. TUNEL stained × 900.

Figure 3.

Cross sections of skeletal muscle after 2 h of ischaemia and 24 h reperfusion. a, Apoptotic neutrophils and macrophages are visible around and within a necrotic muscle fibre and b (and insert), in interstitial tissue. a and b stained with H & E; insert stained with TUNEL, ×900.

The number and distribution of TUNEL positive cells varies with the duration of reperfusion. After 30 min there are on average 5 positive cells per cross section of a muscle. By 8 h most small blood vessels contain labelled cells and more apoptotic cells are present interstitial tissues. At 16 h there are on average 16 labelled cells per muscle cross section, mostly situated in interstitial tissues or within the sarcolemma of necrotic muscle fibres. By 24 h the number of labelled cells has decreased greatly and most are leucocytes in and around necrotic muscle fibres.

At all stages earlier than 8 h reperfusion the nuclei of muscle fibres are uniformly TUNEL negative. At 8 h a few muscle nuclei of normal size show faint, uniform TUNEL staining. At 16 h most muscle nuclei stain in this manner but by 24 h no nuclear staining in muscle is visible and most muscle fibres, which can be recognized as necrotic in H & E stained sections, contain no visible nuclei. The nuclei in the minority of viable fibres are of normal appearance and stain TUNEL negative. At no stage examined do muscle fibre nuclei have the dark, shrunken appearance of apoptosis.

Biochemical findings

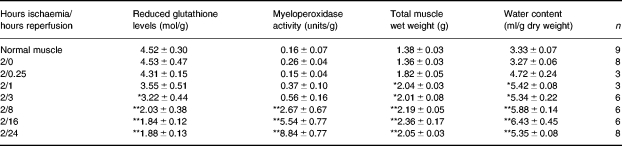

The findings of the several parameters measured are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Tissue levels of reduced glutathione, myeloperoxidase activity and water content, as well as total muscle weight, after 2 h ischaemia and up to 24 h reperfusion

Values are given as mean±SE.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01 (anova/Dunnett's test).

Tissue levels of reduced glutathione are depleted to a minimum of about 50% of normal tissue levels following 8 h reperfusion, and remain at these levels up to 24 h reperfusion. Tissue myeloperoxidase activity does not start to increase significantly until after 3 h reperfusion, but increases steadily thereafter. Tissue water content starts to increase immediately upon reperfusion, reaching plateau levels by 16–24 h reperfusion, in parallel with the total weight of the gastrocnemius muscle.

Discussion

The findings of the present experiments may be summarized as follows. Two hours of tourniquet ischaemia produces extensive but incomplete necrosis of rat skeletal muscle. As measured by NBT staining approximately 80% of muscle fibres are necrotic after 24 h reperfusion. Reperfusion induces an inflammatory reaction with leucocyte infiltration which histological examination and myeloperoxidase levels show begins at about 1 h and is maximal after 8–24 h reperfusion. TUNEL staining reveals the presence of apoptosis in the endothelium of small blood vessels and in extravascular leucocytes. Apoptotic cells are first seen in vascular endothelium after ½ hour reperfusion. The number of affected cells rises with increasing duration of reperfusion and by 8 h apoptotic cells are visible in most blood vessels and many extravascular leucocytes. At no stage examined was apoptosis detected in normal or injured muscle fibres. Several features of these findings merit detailed discussion.

Apoptosis in extravascular leucocytes and endothelial cells

Until recently it was believed that neutrophils in areas of acute inflammation survive only a few hours in tissue before undergoing necrosis with release of their lysomal enzymes into the area of injury. However studies by Haslett and colleagues have shown that in areas of sterile or resolving inflammation most neutrophils and some macrophages end their lives by apoptosis rather than necrosis (Hannah et al. 1995; Haslett 1997). The difference is important because in apoptosis, in contrast to necrosis, the cell membrane remains intact and prevents escape of lysomal enzymes and consequential damage to the inflamed tissues. The findings of the present study extend Haslett's results to another type of injury. As the process of apoptosis lasts only 45–60 min, TUNEL staining at a single time after injury cannot determine what proportion of extravascular neutrophils die by apoptosis. However the large number of TUNEL positive cells present during the later stages of reperfusion suggest that apoptosis plays a major role in the fate of emigrated neutrophils in ischaemia-reperfusion injury.

Apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells has been described in both the development of a lumen in newly formed blood vessels (Gamble et al. 1993; Lang et al. 1994) and in the regression of unwanted vessels in the later stages of wound healing and scar formation (Desmouliere et al. 1995). In the ischaemia-reperfusion model, ischaemia appears to be the stimulus to apoptosis as no angiogenesis occurs during the first 24 h of reperfusion.

Absence of apoptosis in ischaemic skeletal muscle

Apoptosis is known to play a major role during embryogenesis of muscle (Webb 1977; McClearn et al. 1995), in myoblasts during muscle regeneration (Sandri et al. 1996) and in the progression of certain types of muscular dystrophy (Tidball et al. 1995). It has also shown to be important in the death of myocardial fibres after ischaemia-reperfusion injury, for example in isolated perfused rat and human hearts (James et al. 1993; Chakrabarti et al. 1997), in cultured cardiomyocytes (Itoh et al. 1995; Bielawska et al. 1997) and in postmortem studies of the early stages of human myocardial infarcts (Bardales et al. 1996). In skeletal muscle it has been reported that bupivacaine and several other injurious stimuli induce apoptosis in newborn rats up to 5 days after birth, but that the same stimuli at or after 7 days of age cause death of muscle fibres by necrosis (Fidzianska & Kaminska 1991; Kaminska & Fidzianska 1996). There is no published report of cell death by apoptosis following injury to the fully developed myocytes of mature skeletal muscle fibres.

The uniform TUNEL staining of nuclei of histologically normal appearance seen after 8 and 16 h reperfusion in muscle fibres destined to become necrotic is puzzling. When first seen the staining was thought to be artefactual but further study showed it was consistent and reproducible. Dong et al. (1997) and others have reported that necrotic cells may cleave their nuclei in an oligosomic manner and stain TUNEL positive. The present findings suggest that this type of cleavage can occur in the nuclei of dying muscle fibres before histological change is apparent and that the nuclei subsequently disappear by lysis rather than by nuclear fragmentation or pyknosis.

Buttke & Sandstrom (1994) speculated that mild oxidative stress might induce apoptosis whereas a major ischaemic insult leads to necrosis. In the present study both the biochemical findings and the level of necrosis at 24 h indicate a severe level of oxidative stress. However the level of stress will vary within the ischaemic-reperfused tissue being least adjacent to surviving muscle fibres and no apoptosis was seen in these areas. The distribution of muscle fibre type within the rat gastrocnemius was not determined, but a previous study in our laboratory of ischaemia-reperfusion injury to the rabbit rectus femoris showed no correlation between fibre type and the distribution of necrosis within the muscle (Hickey et al. 1996). Some other, as yet undetermined, characteristic of skeletal muscle must be responsible for the absence of apoptosis. Perhaps the very low surface to volume ratio of muscle fibres may explain their unusual behaviour.

In conclusion, skeletal muscle subjected to ischaemia-reperfusion injury appears to die by necrosis, with apoptosis being a major mechanism of cell death in the neutrophils and macrophages that infiltrate the damaged muscle.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rosalind Romeo and Honor Marshall for technical assistance. Financial support from the NHMRC (Australia), the William Buckland Foundation

References

- Bardales RH, Hailey LS, Xie SS, Schaefer RF, Hsu S-M. In situ apoptosis assay for the detection of early acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Pathol. 1996;149:821–829. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielawska AE, Shapiro JP, Jiang L, et al. Ceramide is involved in triggering of cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by ischemia and reperfusion. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;151:1257–1263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttke T, Sandstrom O. Oxidative stress as a mediator of apoptosis. Immunol. Today. 1994;15:7–10. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S, Hoque AN, Karmazyn M. A rapid ischemia-induced apoptosis in isolated rat hearts and its attenuation by the sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibitor HOE 642 (cariporide) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:3169–3174. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmouliere A, Redard M, Darby I, Gabbiani G. Apoptosis mediates the decrease in cellularity during the transition between granulation tissue and scar. Am. J. Pathol. 1995;146:56–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Saikumar P, Weinberg JM, Venkatachalam MA. Internucleosomal DNA cleavage triggered by plasma membrane damage during necrotic cell death. Involvement of serine but not cysteine proteases. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;151:1205–1213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes RS, Cotter TG. Apoptosis or necrosis. Intracellular levels of glutathione influence mode of cell death. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;48:675–681. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidzianska A, Kaminska A. Apoptosis: a basic pathological reaction of injured neonatal muscle. Pediatric Pathol. 1991;11:421–429. doi: 10.3109/15513819109064778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble JR, Matthias LJ, Meyer GT, et al. Regulation of in vitro capillary tube formation by anti-integrin antibodies. J. Cell Biol. 1993;121:931–943. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.4.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA. Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Cell Biol. 1992;119:493–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobe G, Howard T, Browning J, et al. Gene expression associated with apoptosis in hypoxia- or hyperoxia-treated endothelial cells. In: Gavin J, Ormrod DJ, Maxwell L, editors. Progress in Microcirculation Research. Auckland: Uniprint, University of Auckland; 1995. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah S, Mecklenburgh K, Rahman I, et al. Hypoxia prolongs neutrophil survival in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1995;372:233–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00986-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslett C. Granulocyte apoptosis and inflammatory disease. Br. Med. Bull. 1997;53:669–683. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey MJ, Hurley JV, Angel MF, O'Brien B MCc. The response of the rabbit rectus femoris muscle to ischemia and reperfusion. J. Surg. Res. 1992;53:369–377. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(92)90063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey MJ, Hurley JV, Morrison WA. Temporal and spatial relationship between no-reflow phenomenon and postischemic necrosis in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:H1277–H1286. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.4.H1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie Y, Wolf R, Granger DN. Role of nitric oxide in gut ischemia reperfusion-induced hepatic microvascular dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:G1007–G1013. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.5.G1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh G, Tamura J, Suzuki M, et al. DNA fragmentation of human infarcted myocardial cells demonstrated by nick end labeling method and DNA agarose gel electrophoresis. Am. J. Pathol. 1995;146:1325–1331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James TN, Terasaki F, Pavlovich ER, Vikhert AM. Apoptosis and pleomorphic micromitochondriosis in the sinus nodes surgically excised from five patients with long QT syndrome. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1993;122:309–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminska AM, Fidzianska A. Experimental induction of apoptosis and necrosis in neonatal rat skeletal muscle. Basic Appl. Myology. 1996;6:251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JFR. Shrinkage necrosis: a distinct mode of cellular death. J. Pathol. 1971;105:13–29. doi: 10.1002/path.1711050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout M, Lepore DA, Knight KR, et al. Cool preservation solutions for skin flaps: a new mixture of pharmacological agents which improves skin flap viability. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1995;48:132–144. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(95)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, Lustig M, Francois F, Sellinger M, Plesken H. Apoptosis during macrophage-dependent ocular tissue remodelling. Development. 1994;120:3395–3403. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majno G, Joris I. Apoptosis, oncosis and necrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 1995;146:3–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClearn D, Medville R, Noden D. Muscle cell death during the development of head and neck muscles in the chick embryo. Dev Dynamics. 1995;202:365–377. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002020406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo A, Yeh J. In situ localization of apoptosis in the rat ovary during follicular atresia. Biol. Reprod. 1994;51:888–895. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter C, Schweizer M, Cossarizza A, Franceschi C. Control of apoptosis by the cellular ATP level. FEBS Lett. 1996;378:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandri M, Cantini M, Massimino ML, Geromel V, Arslan P. Myoblasts and myotubes in primary cultures deprived of growth factors undergo apoptosis. Basic Appl. Myology. 1996;6:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak J, Lindsay RL. Estimation of total, protein-bound and non-sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman's reagent. Anal. Biochem. 1968;25:192–205. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terao Y, Shikata O, Goto S, et al. Phospholipase A2 is activated in the kidney, but not in the liver during ischemia-reperfusion. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1997;96:277–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidball JG, Albrecht DE, Lokensgard BE, Spencer MJ. Apoptosis precedes necrosis of dystrophin-deficient muscle. J. Cell Sci. 1995;108:2197–2204. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JN. Cell death in developing skeletal muscle: histochemistry and ultrastructure. J. Path. 1977;123:175–180. doi: 10.1002/path.1711230307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue TL, Ma XL, Wang X, et al. Possible involvement of stress-activated protein kinase signaling pathway and Fas receptor expression in prevention of ischemia/ reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by carvedilol. Circ. Res. 1998;82:166–174. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]