Abstract

Long-term intragastric administration of the antiepileptic drug sodium valproate (Vuprol ‘Polfa’) to rats for 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, once daily at the effective dose of 200 mg/kg body weight showed morphological evidence of encephalopathy, manifested by numerous nonspecific changes within Purkinje cell perikarya and their dendritic processes. The first ultrastructural abnormalities appeared after 3 months. They became more severe in animals with longer survival and were most pronounced after 12 months. The changes were maintained both 1 and 3 months after drug withdrawal. Mitochondria of Purkinje cell perikarya were most severely affected. Damage to mitochondria was accompanied by disintegration and fragmentation of granular endoplasmic reticulum, dilation of channels and cisterns of Golgi apparatus, enlargement of smooth endoplasmic reticulum elements including submembranous cisterns, and accumulation of profuse lipofuscin deposits. Frequently, Purkinje cells appeared as ‘dark’ ischemic neurones, with focally damaged cellular membrane and features of disintegration. Swollen Bergmann's astrocytes were seen among damaged Purkinje cells or at the site of their loss. The general pattern of submicroscopic alterations of Purkinje cell perikarya suggested severe disorders in several intercellular biochemical extents, including inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation and abnormal protein synthesis, both of which could lead to lethal damage. Ultrastructural abnormalities within dendrites were characterized by damage to elements of smooth endoplasmic reticulum, which was considerably enlarged, with formation of large vacuolar structures situated deep in the dendroplasm. Mitochondrial lesions and alterations in cytoskeletal elements – disintegration of microtubules or even their complete loss –were also observed. The general pattern of abnormalities within the organelles and cytoskeletal elements of dendritic processes in Purkinje cells in the VPA chronic experimental model imply that there are disturbances in detoxication processes. Furthermore these changes were irreversible, as they were maintained after drug withdrawal.

Keywords: valproate, encephalopathy, Purkinje cell perikarya, dendrites, cerebellar cortex, ultrastructure, rats

Introduction

Clinical and experimental studies have shown that some anatomic structures of the central nervous system (CNS), especially the cerebellum and the hippocampal gyrus, are particularly sensitive to the long-term effects of various antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). These drugs can cause functional disorders and organic lesions in nerve tissue already affected by epilepsy (Schöndienst & Wolf 1992; Ney et al. 1994; Timmings & Richens 1995).

Predilective susceptibility of the cerebellum to the toxic effects of chronic AED therapy may, according to some authors, be explained by a significantly reduced cerebellum/global cerebral metabolism of glucose (CMRGlu) ratio (Seitz et al. 1996; Timmings & Richens 1995).

However, some investigators, e.g. Dam (1970a), Dam et al. (1980), Neilsen & Dam (1970), Nielsen et al. (1971) do not share the opinion concerning the neurotoxic action of antiepileptic drugs.

Sodium valproate (VPA) is one of the most commonly used antiepileptic drugs, defined by Löscher (1992) as a classic modern antiepileptic.

This antiepileptic causes an increased concentration of an inhibitory neurotransmitter – gammaminobutyric acid (GABA) in CNS synapses and of certain similarly acting amino acids, e.g. taurine, glycine, thus leading to a reduced release of stimulatory neurotransmitters, e.g. aspartate, gammahydroxybutyric acid (Chapman et al. 1984; Anyanwu & Harding 1993; Löscher 1993a,1993b; Baf et al. 1994; Voiculescu et al. 1994; Vargas et al. 1998). Acting on the GABA-ergic system, it effectively cures primary generalized seizures (absence attacks) and generalized convulsive myoclonic seizures (Bazil & Pedley 1998; Sharpe & Buchanan 1995; Sobaniec 1991, 1992; Vaquerizo et al. 1998; Wallace 1998). It also plays an important role in the treatment of affective disorders and prophylaxis of migraine (Mathew et al. 1995; Stoll et al. 1994; Brady et al. 1995; Vargas et al. 1998).

However, chronic application of VPA at its therapeutic serum concentration, may induce undesired toxic symptoms from the CNS (especially from the cerebellum and extrapyramidal system), defined as ‘valproate encephalopathy’ (Blindauer et al. 1998; Settle 1995; Guerrini et al. 1998; Oechsner et al. 1998; Gobel et al. 1999). The most significant mechanisms of undesired VPA effect on CNS, especially on the cerebellum, which is manifested mainly in ataxia, include substantial neuronal membrane action disorders, with impulse blocking – the so called membrane effects (Löscher 1993b; Perlman & Goldstein 1984a,b; Tian & Alkadhi 1994). It may be also teratogenic for the organism, particularly for the CNS (Boussemart et al. 1995; Scott et al. 1997; Menegola et al. 1999; Mo & Ladusans 1999).

VPAs have been studied intensively in neuropharmacology, but neuropathologic investigations, like in the case of most AEDs, are scarce. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to perform an ultrastructural analysis of perikarya and dendritic processes of Purkinje cells in the rat cerebellar cortex during the course of chronic application of VPA. The study is a continuation of our investigations of the cerebellar cortex in our model of chronic experimental VPA encephalopathy which is characterized clinically by ataxia, reduced psychomotor and cognitive activity, and somnolence. It was inspired by our preliminary ultrastructural observations of Purkinje cell perikarya and their dendrites which showed substantial degenerative changes, including necrosis in animals with longer survival in the same experimental model (Sobaniec et al. 1989; Sobaniec–Lotowska & Sobaniec 1993a,b, 1996; Sobaniec–Lotowska 1994b, 1995; Sobaniec–Lotowska et al. 1999),and was based on the assumption that any electron microscopic abnormalities found both in the Purkinje cell perikarya and within the protoplasmic processes of these neurones would be significant in both the morphogenesis and pathogenesis of experimental VPA encephalopathy.

Materials and methods

The experiment used 56 three-month-old male Wistar rats of initial body mass 160–180 g, pre-selected according to standard pharmacological screening tests. The animals were kept in a well sunlighted room at 18–20 °C and fed standard granulated rat chow and tap water. All procedures were carried out in strict accordance with the Helsinki Convention guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

The animals were divided into 3 groups: Group I contained 30 rats given sodium valproate (Vupral Polfa), as a 20% solution of sodium salt of valproinian acid dissolved in physiological saline, through an intragastric tube once daily (for fasting). It was administered at the effective dose of 200 mg/kg of body weight for 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months (six animals in each time subgroup).

Group II consisted of 12 rats (2 subgroups), in which VPA administration was terminated after 12 months. The animals were sacrificed after 1 and 3 months of the observation.

The control group (14 control animals) matched the experimental rats in respect of age and body mass. They received the same amount of physiological saline and in the same way as the group I rats treated with the antiepileptic.

All experimental groups were subjected to behavioural examinations using Lat's test to evaluate the psychomotor and cognitive activity of the animals. The results will be described in a separate paper. The animals were weighed every two weeks to verify the amount of drug.

Serum concentration of VPA in group I was measured by gas chromatography and ranged between 60 and 135 µg/mL (mean 111,3333 (g/mL; SD 21,6131).

At the end of the experiment, 24 h after the last VPA dose, the animals were sacrificed under Nembutal anaesthesia using a dose of 25 mg/kg of body weight by intravital intracardiac perfusion with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, at constant pressure of 80 mmHg. Small tissue blocks (1 mm3 volume) cut off the cortex of the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis were routinely embedded in Epon 812. Semithin sections were stained with toluidine blue and examined in the light microscope, while ultrathin sections were contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined using an OPTON 900 transmission electron microscope (Sobaniec–Lotowska & Sobaniec 1996).

The material obtained from the cerebellar cortex in group II and control was processed using the same techniques as for the VPA-receiving rats.

Results

Control group

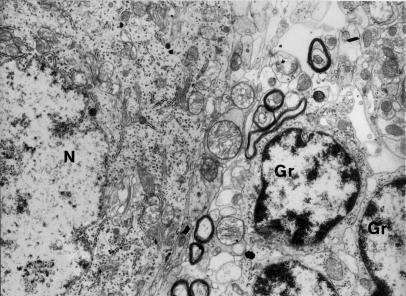

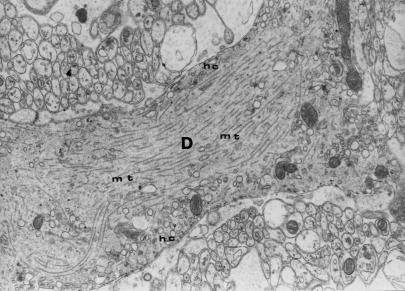

The ultrastructure of perikarya as well as dendrites of Purkinje cells did not demonstrate substantial differences among rats in individual control age subgroups. It was similar to the electron microscopic pictures presented by Palay & Chan–Palay (1974) in the monograph of cerebellar cortex cytology and organization. Two representative microphotographs of the Purkinje cell, one of the perikaryon (Fig. 1) and the other of the dendritic process (Fig. 2), are included in the present study.

Figure 1.

Fragment of Purkinje cell perikaryon contains well-preserved endoplasmic structures. In the vicinity granular cells (Gr) are visible. N-nucleus of Purkinje cell contains electron light, homogenously dispersed euchromatin and small granules of heterochromatin. Control group – 6 months of observations (x 4400).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal cross–section through a fragment of dendritic process (D) of Purkinje cell with unchanged organelles and regular arrangement of microtubules (mt); hc – submembranous cisterns. Control group – 12 months of observations (x 7000).

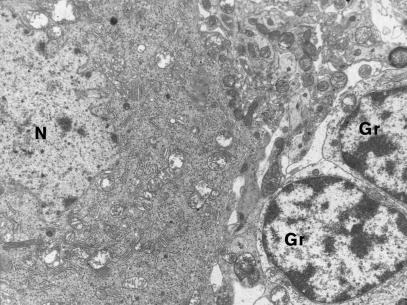

Group I (treated chronically with VPA)

The first ultrastructural changes within Purkinje cell perikarya of the cerebellar cortex and their dendritic processes were detectable after 3 months of VPA administration. Features of slight or moderate swelling were observed. Sometimes the mitochondrial matrix of the perikarya showed focally increased translucence (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Fragment of Purkinje cell perikaryon shows mitochondria with matrix of focally increased translucence; well-preserved small granular cells (Gr) in the vicinity. N-nucleus of Purkinje cell. 3 months of VPA administration (x 3000).

After 6 months, the swelling of Purkinje cell perikarya and dendrites was more pronounced than after 3 months. Structural abnormalities of certain cellular organelles, particularly of mitochondria in the case of perikarya and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) – in the case of dendrites, were moderate. Some mitochondria were enlarged and showed rarefaction or partial emptiness of the matrix, and loss of cristae of varied intensity. Quite frequently the granular endoplasmic reticulum (GER) of the perikarya had irregularly arranged channels, which were dilated, shortened and had sparsely distributed ribosomal granules. The above changes were accompanied by the dilation of channels and cisterns of Golgi apparatus mainly in the perinuclear region. Cytoplasm contained tiny dispersed deposits of lipofuscin with compact, strongly osmophilic granular structure. Some dendrites contained a small number of irregularly arranged microtubules.

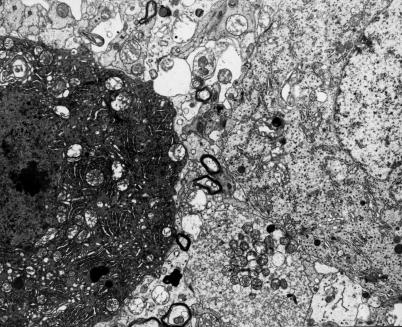

After 9 and 12 months of VPA treatment, perikarya of most Purkinje cells displayed severe degenerative changes, including disintegration. The cells were either enlarged or contracted, with cytoplasm usually showing increased electron density in both cases. Topography of the neuronal changes, sclerosis and losses of Purkinje cells in particular, in association with the proliferation of adjacent Bergmann's glia cells in the molecular layer were visualized similar to our earlier morphological analysis of the same experiment, using low magnification in the light microscope (Sobaniec et al. 1989).

Ultrastructural examinations of Purlinje cells revealed considerable abnormalities within most of the endoplasmic organelles leading, particularly after 12 months, to lethal neurone damage (Figs 4, 7 and 8). In the perikarya, the changes mostly affected mitochondria and GER.

Figure 4.

Adjacent perikarya of two Purkinje cells. One appears as dark neurone and shows marked disintegration of karyoplasm and cytoplasm, the other is quite well-preserved. 9 months of VPA administration (x 3000).

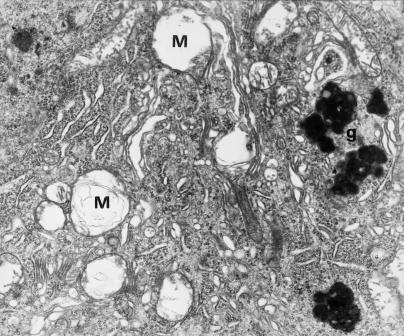

Figure 7.

Fragment of Purkinje cell perikaryon with large lipofuscin granules (g) and advanced degeneration of organelles, particularly mitochondria (M). 12 months of VPA administration (x 7000).

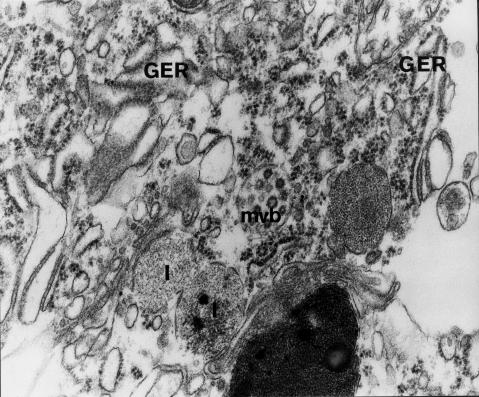

Figure 8.

Fragment of disintegrating Purkinje cell perikaryon. Damaged cellular membrane. Degenerative changes include disintegration of endoplasmic structures – channels of granular endoplasmic reticulum (GER) are shortened, dilated and partially devoid of ribosomal granules; visible are damaged lysosomes (1), increased number of ribosomes, multivesicular body (mvb), lipofuscin granule. 12 months of VPA administration (x 20 000).

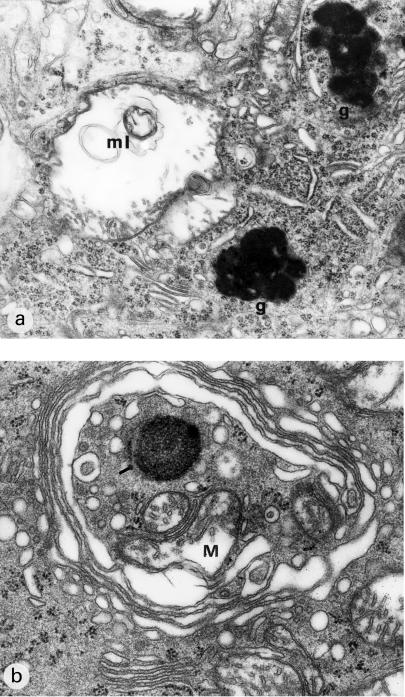

Mitochondria were characterized by considerable polymorphism with pronounced regressive changes, including desintegration (Figs 5,6a and 7). In some regions of cytoplasm, excessive accumulation of these organelles was noted. Frequently they showed marked swelling. Fragments of mitochondrial cristae were usually encountered in the peripheral region (Figs 5, Figs 6a,6b and 7). Some mitochondria resembled double-contoured, balloon-like electron-lucent vacuoles (Figs 5 and 7). Their matrix sometimes contained microfibrillar material or myelinic structures (Figs 6a and 7).

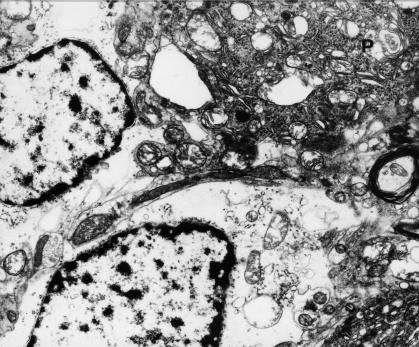

Figure 5.

Fragments of two substantially swollen Bergmann's astrocytes situated in the vicinity of degenerated Purkinje cell (P); the cytoplasm of Purkinje neurone shows markedly damaged mitochondria and dark microgranular material. 9 months of VPA administration (x 4400).

Figure 6.

(a) Fragment of Purkinje cell perykaryon. Markedly swollen deformed mitochondrium contains myelinic structures (ml), fragments of mitochondrial cristae situated on the periphery. In the vicinity, large lipofuscin deposits (g), shortened channels of granular endoplasmic reticulum, the increase in the number of ribosomes and dilated channels of smooth endoplasmic reticulum. (b) Markedly dilated Golgi apparatus surrounds degenerating cellular organelles – mitochondria (M), a lysosome-like dense body and ribosomes. 9 months of VPA administration (x 12 000).

Degenerated perikarya contained dilated and shortened GER channels. They frequently showed segmental degranulation to disintegration (Figs 6a and 8). Subjectively there appeared to be ribosomes in the cytoplasm (Figs 6 and 8), particularly in the perinuclear regions, but this could not be quantified. Elements of smooth endoplasmic reticulum situated deep in the cytoplasm and under the cellular membrane (i.e. submembranous cisterns) showed focal proliferation (Fig. 6a).

The golgi apparatus was frequently enlarged and contained a few rows of dilated channels and cisterns, and an increased number of vacuoles. Fragments of cytoplasm with degenerating organelles (mitochondria, ribosomes, dense bodies resembling lysosomes) were sometimes observed within its zone (Fig. 6b).

The presence of numerous large lipofuscin granules blending with each other and lysosomal bodies within the cytoplasm was a specific feature of most perikarya (Figs 6a, 7 and 8).

Purkinje cells with features of dark ischemic neurones were quite common. Dark, lethally damaged and markedly contracted perikarya showed pronounced disintegration of endoplasmic structures, with microgranular disintegration and profound abnormalities of the cellular nucleus (Figs 4 and 5). Some cytoplasm regions were filled with dark homogenous microgranular material. Also elements of the cytoskeleton – microtubules – frequently were disintegrated. Nuclei of such cells were shrunken and contained condensed granular or amorphous homogenous nucleoplasm (Fig. 4). The cellular membranes of damaged Purkinje neurones were sometimes discontinuous or disintegrated (Fig. 8).

Substantially swollen Bergmann's astrocytes were found among altered perikarya of Purkinje cells or at the site of their loss. They frequently showed definite polarization of the organelles, including extensive swelling of mitochondria, on one side of the nucleus. The nuclei of Bergmann's astrocytes were markedly swollen, with damage to nuclear membranes (Fig. 5). Some cytoplasmic areas of these cells had no organelles but contained flocculent material or electron lucent ‘watery’ cisterns and dense osmophilic bodies, as in the author's previous publications (Sobaniec-Lotowska et al. 1995; Sobaniec-Lotowska & Sobaniec 1996).

After 9 and 12 months severe swelling was observed in most basement dendrites of Purkinje cells seen in neuropil, their ramifications and dendrites of other neurones. Dendroplasm of Purkinje cell processes showed decreased electron density (Fig. 11). Sometimes, however, dendrites were shrunken and had dark cytoplasm (Figs 12a.b).

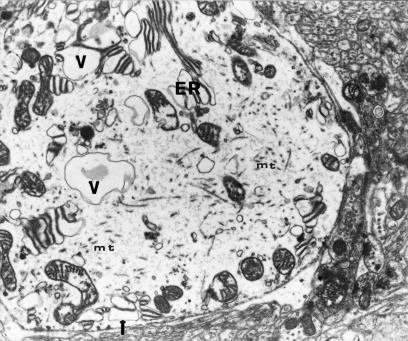

Figure 11.

Transverse cross-section through a swollen dendrite of Purkinje cell shows a reduced number of microtubules (mt), dilated channels both of smooth endoplasmic reticulum (including submembranous channels and granular endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and large vacuolar structures (V) situated deep in dendroplasm, some mitochondria are focally changed. 9 months of VPA application (x 7000).

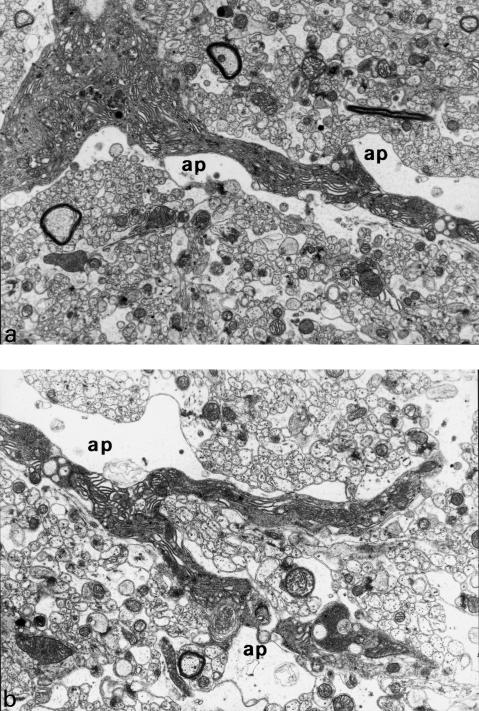

Figure 12.

Longitudinal cross-section through a basement dendrite of Purkinje cell (a) and its ramifications (b). Swollen astrocytic processes (ap) are adjacent to dark, shrunken, dendritic processes. 9 months of VPA application (x 4400).

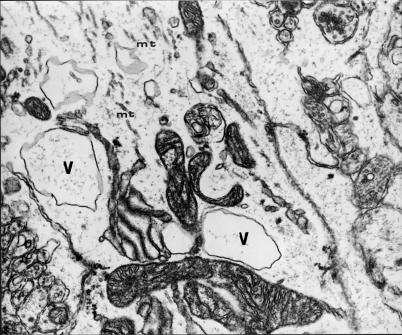

SER elements, particularly cisterns and channels situated deep in dendroplasm of swollen dentritic processes, were frequently enlarged and formed large translucent vacuoles, oval or irregular in shape (Figs 11 and 14). SER channels situated under the cellular membrane, the so called submembranous cisterns, were also dilated (Fig. 11). Some mitochondria within dendrites, like those within perikarya, were markedly swollen, showed increased translucence of matrix and damaged cristae. Sometimes these organelles were filled up with microfibrillar material or myelinic structures. Their cristae were almost lost (Fig. 13).

Figure 14.

Transverse cross-section through a substantially swollen dendrite containing large vacuolar structures (V), profiles of granular endoplasmic reticulum (GER) channels and rare microtubules (mt). 12 months of VPA application (x 12 000).

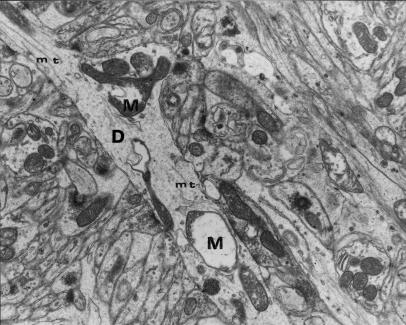

Figure 13.

Longitudinal cross-section through a dendritic process of Purkinje cell containing polymorphic mitochondria – M (one of them is balloon-shaped and filled with microfibrillar material) and very rare microtubular fragments (mt). 12 months of VPA application (x 7000).

Other dendritic changes included damage to cytoskeletal elements. Microtubules were reduced in number and arranged irregularly (Figs 11, 13 and 14). Sometimes only very small fragments of microtubules or their total loss were observed (Fig. 13).

Astrocytic processes adjacent to damaged dendrites frequently showed features of swelling (Figs 12a.b).

Group II (after cessation of VPA administration)

The ultrastructural picture of Purkinje cell perikarya (9, 10) and dendritic processes (Fig 15) 1 and 3 months after cessation of a year-long exposure to VPA was similar to that found in the last phases of VPA application, i.e. after 9 and 12 months. Neurones frequently showed considerable disintegration of cytoplasmic structures, accumulation of large lipofuscin granules and discontinuous cellular membrane (Fig. 9). Lethally damaged cells were still present; they were dark, shrunken, with cytoplasm containing microgranular material of increased electron density (Fig. 10) and nuclei with homogenous nucleoplasm.

Figure 15.

Markedly swollen dendrite with large vacuolar structures (V), dilated channels of granular endoplasmic reticulum (GER) and microtubular fragments (mt). 3 months after the end of chronic VPA application (x 12 000).

Figure 9.

Fragment of disintegrating perikaryon of Purkinje cell. Thick lipofuscin granules, blending with each other, occupy a substantial part of cytoplasm. 1 month after the end of VPA application (x 12 000).

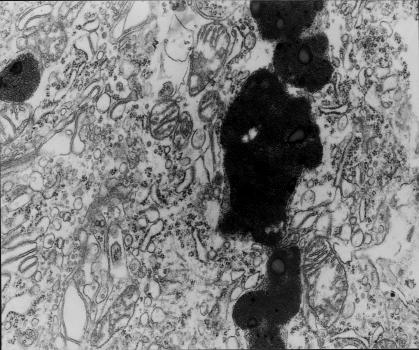

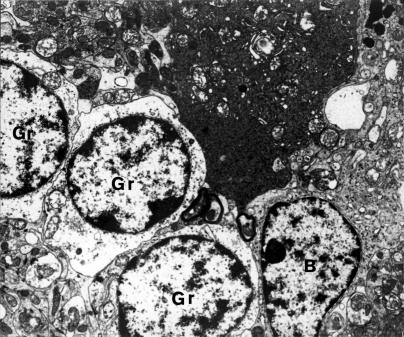

Figure 10.

Fragment of dark, shrunken, lethally damaged Purkinje neurone (P). In the vicinity, swollen small granular cells (Gr) arranged in series. B- Bergmann's astrocyte. 3 months after the end of VPA application (x 3000).

Discussion

The earliest morphological alterations in Purkinje cell perikarya in the rat cerebellar cortex appeared after 3 months of VPA administration, and were more severe in animals the longer they survived, being most pronounced after 12 months of the experiment. The changes were still present 1 and 3 months following the drug withdrawal.

The prolonged persistence of degenerate Purkinje cells could be explained by adaptive response mechanism of nervous tissue, particularly in the cerebellar cortex, to chronic action of VPA and/or its toxic metabolities. Moreover, damage to the liver in the same experimental model, the main organ involved in biotransformation of valproate, can play an additional role (Sobaniec-Lotowska 1994a; Sobaniec–Lotowska et al. 1993; Sobaniec–Lotowska & Sobaniec 1994; Sobaniec-Lotowska 1997).

The major ultrastructural changes seen within the perikarya of Purkinje cells included damage to mitochondria, their polymorphism, swelling, matrix destruction with formation of myelinic structures, loss of cristae. Mitochondrial degeneration was accompanied by irregular arrangement and disintegration of GER channels, dilation of channels and cisterns of Golgi apparatus, enlargment of SER (including submembranous cisterns), accumulation of profuse lipofuscin deposits, and damage to cytoskeletal elements. Frequently, Purkinje cells had features of dark ischemic neurones, with focally damaged cellular membrane and marked disintegration. The main morphologic abnormalities within dendritic processes of Purkinje cells included enlargement of SER forming large vacuolar structures and marked damage to cytoskeletal elements manifested in disintegration of microtubules or even their almost complete loss after 9 and 12 months of VPA administration and after the drug withdrawal. The pattern of Purkinje cell damage observed in the present study is consistent with our earlier preliminary findings (Sobaniec–Lotowska 1995).

The general picture of submicroscopic abnormalities within the neurones in the course of VPA administration and after the drug withdrawal is consistent with profound disorder of intercellular biochemical events, such as inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation, abnormal production of proteins, and the dysfunction of the detoxication and secretory processes, as well as disorders of morphological cell integrity. This would then be the cause of the lethal neuronal damage. It is noteworthy that the plasma concentration of VPA is high relative to therapeutic doses, which may account for the external changes seen.

Electron-microscopic changes in Purkinje cells in the course of chronic VPA treatment in rats are not specific. Similar abnormalities, although of varied intensity, have been observed in other experimental models of cerebellar damage. They were found in chronic intoxication with another basic antiepileptic drug, phenytoin, (Del Cerro & Snider 1967; Dowson et al. 1992), in chronic intoxication with ethanol (Volk et al. 1981; Tavares & Paula–Barbosa 1983a,b; Paula–Barbosa & Tavares 1985; Lewandowska et al. 1994), in hypoxic-ischemic conditions (Kalimo et al. 1979; Pluta 1986), or in organotypical culture of the cerebellum of rat newborns subjected to short-term anoxia (Krasnicka et al. 1976).

The present results are consistent with the hypothesis that chronic administration of VPA first of all significantly inhibits oxidative phosphorylation processes in Purkinje cell mitochondria. This is supported by biochemical studies which have been performed in vitro on isolated mitochondria of the brain, the liver and the kidneys in the course of acute VPA administration (Rumbach et al. 1983, 1989; Hayasaka et al. 1986; Bjorge & Baillie 1991).

Long-term VPA administration also causes considerable damage to the system associated with structural and functional biosynthesis of cell proteins, manifested in substantial destruction of the GER channels and polyribosomal structures of neurones. Fragmentation of GER profiles accompanied by detachment of numerous ribosomes and microgranular disintegration of other organelles led to profound degenerative changes manifested in markedly increased electron density in cytoplasm of Purkinje cell perikarya, seen as ‘dark neurones’. According to some authors (e.g. Iwanowski (1988), Walski et al. (1991), Ratan et al. (1994)) the appearance of dark neurones may reflect a certain phase of apoptosis. However, in the present experiment Purkinje cells, despite having markedly condensed cytoplasm and nucleoplasm, differed significantly from typical apoptotic neurones. They showed more severe mitochondrial damage, compared with that found in apoptosis, had no characteristic changes in cell nucleus (no typical chromatin fragmentation) and no apoptotic bodies. Moreover, the cellular membrane of VPA-changed neurones was discontinuous, which is not observed in the course of controlled cell death (Arends et al. 1990; Zabel 1997).

Some investigators believe that morphogenesis of dark neurones situated in various regions of grey matter of the CNS is usually ischemic (Petito & Pulsinelli 1984; Kirino et al. 1985; Mossakowski et al. 1989; Walski et al. 1991). It should be noted that substantial abnormalities observed in the same experimental model in the capillary wall both of the cerebellar cortex and dentate nucleus indicate disorders in the transportation of sodium VPA and/or its toxic metabolites through structural elements of the blood–brain barrier to neurones and vice versa, i.e. from nerve cells to the blood (Sobaniec–Lotowska 1994a,b; Sobaniec–Lotowska & Sobaniec 1996), which is consistent with the observations of Noara & Shen (1995). The ‘vascular factor’ may thus be one of the main causes of dark Purkinje cell formation in the course of chronic VPA administration.

The characteristic degenerative changes within dendroplasm of Purkinje cells observed in the present experiment, such as SER enlargement and formation of vacuolar structures, might occur due to disintegration of GER channels focally devoid of ribosomes. This is consistent with other reports of similar changes within both types of endoplasmic reticulum of Purkinje cells in the course of chronic experimental intoxication with ethanol (Lewandowska et al. 1994). It is known that SER plays a key role in detoxication processes (Stodolnik–Baranska 1995). Thus, long-term VPA application may impair these processes.

An interesting morphological feature is the severe damage to cytoskeletal elements within the protoplasmic processes of Purkinje cells. Some authors, (Thyberg & Moskalewski 1985, Walski & Borowicz 1988, Duchen 1992, Kawiak 1997) underline an essential role of microtubules in maintenance of morphological integrity of the cell and its processes as a whole, which may condition normal neurone volume. They pay attention to the function of microtubules in ensuring good organization between organelles and stress their contribution to endoplasmic transport. Moreover, they reveal a strong link between microtubules and the morphological and functional condition of the Golgi apparatus of the nerve cell perikaryon whose elements undergo marked disintegration due to a microtubule disorder (Sobaniec–Lotowska et al. 1999).

Certain drugs, particularly alkaloids, such as colchicine, vinblastine, vincristine preclude polymerization of microtubular subunits and their proper organization. This is due to a large number of SH groups found in tubulina, which combine with alkaloids and cause their depolymerization (Groniowski 1981; Thyberg & Moskalewski 1985; Walski & Borowicz 1988; Gelfand & Bershadsky 1991; Mossakowski 1995; Stodolnik–Baranska 1995; Kawiak 1997). As a result, microtubules break into fragments to form smaller protein subunits (Duchen 1992; Thyberg & Moskalewski 1985; Kawiak 1997). Also certain physical factors, including increased concentration of calcium ions and low temperature, cause severe disintegration of microtubules (Groniowski 1981; Gelfand & Bershadsky 1991; Kawiak 1997).

The morphological picture of microtubules within dendroplasm of Purkinje cells, and in particular their marked disintegration, is similar to that observed in the course of chronic application of ethanol in rats (Paula–Barbosa & Tavares 1985; Lewandowska et al. 1994). VPA-induced damage to microtubules of dendritic processes in Purkinje cells could largely affect the volume of the nerve cell and cause endoplasmic transport disorders via this route.

In conclusion, a general pattern of submicroscopic abnormalities within Purkinje cells has been described in animals with longer survival on VPA treatment, suggesting that a combination of disorders in intercellualr biochemical events (particularly oxidative phosphorylation, protein synthesis, detoxication process) as well as disorders in morphological cell integrity and endoplasmic transport, may lead to lethal neuronal damage to these neurones. The ultrastructural changes in Purkinje cells induced by long-term VPA administration seem irreversible, and are maintained after cessation of treatment.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank her brother Professor Wojciech Sobaniec, MD, Head of the Department of Pediatric Neurology, Medical Academy of Bialystok, for inspiration and cooperation.

References

- Anyanwu E, Harding GF. The involvement of taurine in the action mechanism of sodium valproate (VPA) in the treatment of epilepsy. Acta Physiol. Pharmacol. Ther-Latinoam. 1993;43:20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arends MJ, Morris RJ, Wyllie AH. Apoptosis: the role of the endonuclease. Am. J. Pathol. 1990;136:593–608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baf MH, Subhash MN, Lakshmana KM, Rao BS. Sodium valproate induced alterations in monoamine levels in different regions of the rat brain. Neurochem. Int. 1994;24:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazil CW, Pedley TA. Advances in the medical treatment of epilepsy. Annu. Rev. Med. 1998;49:135–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorge SM, Baillie TA. Studies on the beta-oxidation of valproic acid in the rat liver mitochondrial preparations. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 1991;19:823–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blindauer KA, Harrington G, Morris GL, 3rd & Ho KC. Fulminant progression of demyelinating disease after valproate – induced encephalopathy. Neurology. 1998;51:292–295. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussemart T, Bonneau D, Levard G, Berthier M, Oriot D. Omphalocele in a newborn baby exposed to sodium valproate in utero. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1995;154:220–221. doi: 10.1007/BF01954275. 10.1007/s004310050279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Sonne SC, Anton R, Ballenger JC. Valproate in the treatment of acute bipolar effective episodes complicated by subacute abuse: a pilot study. J. Clin. Psych. 1995;56:118–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AG, Croucher MJ, Meldrum BS. Anticonvulsant activity of intracerebroventricularly administered valproate and valproate analogues. A dose-dependent correlation with changes in brain aspartate and GABA levels in DBA /2 mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984;33:1459–1463. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90413-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam M. The number of Purkinje cells after diphenylhydantoin intoxication in monkeys. Epilepsia. 1970a;11:199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1970.tb03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam M, Christensen JM, Brandt J, Hansen BS, Hvidberg EF, Angelo H, Lous P. Antiepileptic drugs: interaction with dextropropoxyphene. In: Johannessen SI, Pippenger CE, Schmidt D, Morselli PL, Richens A, Meinardi H, editors. Antiepileptic Therapy: Advances in Drug Monitoring. New York: Raven Press; 1980. pp. 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Del Cerro MP, Snider RS. Studies on Dilantin intoxication. I. Ultrastructural analogies with the lipoidoses. Neurology. 1967;17:452–466. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowson JH, Wilton-Cox H, James NT. Lipopigment in rat hippocampal and Purkinje neurones after chronic phenytoin administration. J. Neurol. Sci. 1992;107:105–110. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(92)90216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen LW. Adams JH, Duchen LW. Greenfield's Neuropathology. 5. London: Edward Arnold; 1992. General pathology of neurons and neuroglia; pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand VJ, Bershadsky AD. Microtubule dynamics: mechanism, regulation and function. Ann. Rev. Cell. Biol. 1991;7:93–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobel R, Gortzen A, Braunig P. Encephalopathies caused by valproate. Fortschr. Neurol. Psychiatr. 1999;67:7–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groniowski J. Ultrastructural elements of intracellular order. Pat. Pol. 1981;32:449–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Belmonte A, Canapicchi R, Casalini C, Perruca E. Reversible pseudoatrophy of the brain and mental deterioration associated with valproate treatment. Epilepsia. 1998;39:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayasaka K, Takahashi I, Kobayashi Y, Iinuma K, Narisawa K, Tada K. Effects of valproate on biogeneses and function of liver mitochondria. Neurology. 1986;36:351–356. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanowski L. Apoptosis and dark neurons. Neuropat. Pol. 1988;26:574–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalimo H, Paljärvi L, Vapalahti M. The early ultrastructural alterations in the rabbit cerebral and cerebellar cortex after compression ischaemia. Neuropat. Appl. Neurobiol. 1979;5:211–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1979.tb00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawiak J. Cytoskeletal components. In: Kawiak J, Mirecka J, Olszewska M, Warchol J, editors. The Basis of Cytophysiology. Warszawa: PWN; 1997. pp. 294–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kirino T, Tamura A, Sano K. Selective vulnerability of the hippocampus to ischemia-reversible and irreversible types of ischemia cell damage. Prog. Brain Res. 1985;63:39–58. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)61974-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnicka Z, Gajkowska B, Mossakowski MJ. Effect of short-lasting anoxia in vitro culture of cerebellum. Neuropat. Pol. 1976;14:11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska E, Kujawa M, Jedrzejewska A. Ethanol-induced changes in Purkinje cells of the rat cerebellum. I. The ultrastructural changes following chronic ethanol intoxication (quantitative study) Folia Neuropathol. 1994;32:51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W. Valproinsäure: Pharmakodynamische Wirkungen und biochemische Wirkungsmechanismem. In: Krämer & G, Laub M, editors. Valproinsäure. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W. Effects of the entiepileptic drug valproate on metabolism and function of inhibitory and excitatory amino acids in the brain. Neurochem. Res. 1993a;18:485–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00967253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W. In vivo administration of valproate reduces the nerve terminal (synaptosomal) activity of GABA aminotransferase in discrete brain areas of rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1993b;160:177–180. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90407-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew NT, Saper JR, Silberstein SD, et al. Migraine phrophylaxis with divalproex. Arch. Neurol. 1995;52:281–286. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540270077022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menegola E, Broccia ML, Prati M, Giavini E. Morphological alterations induced by sodium valproate on somites and spinal nerves in rat embryos. Teratology. 1999;59:110–119. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199902)59:2<110::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-2. 10.1002/(sici)1096-9926(199902)59:2<110::aid-tera5>3.3.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo CN, Ladusans EJ. Anomalous right pulmonary artery origins in association with the fetal valproate syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 1999;36:83–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski MJ. Nerve tissue and the nervous system. In: Ostrowski K, editor. Histology. Warszawa: PZWL; 1995. pp. 349–442. [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski MJ, Gajkowska B, Tsitsishvili A. Ultrastructure of neurons from the CA1 sector of Ammon's horn in short-term cerebral ischemia in mongolian gerbils. Neuropat. Pol. 1989;27:39–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ney GC, Lantos G, Barr WB, Schaul N. Cerebral atrophy in patients with long-term phenytoin exposure and epilepsy. Arch. Neurol. 1994;51:767–771. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540200043014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MH, Dam M. Purkinje's cell density after diphenylhydantoin intoxication in rats. Arch. Neurol. 1970;23:555–558. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1970.00480300077010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MH, Dam M, Klinken L. The ultrastructure of Purkinje cells in diphenylhydantoin intoxicated rats. Exp. Brain. Res. 1971;12:447–456. doi: 10.1007/BF00234242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noara K, Shen DD. Mechanism of valproate acid uptake by isolated rat brain microvessels. Epilepsy Res. 1995;22:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(95)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oechsner M, Steen C, Sturenburg HJ, Kohlschutter A. Hyperammonaemic encephalopathy after initation of valproate therapy in unrecognised ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1998;64:680–682. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.5.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palay SL, Chan-Palay V. Cerebellar Cortex Cytology and Organization. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Paula-Barbosa MM, Tavares MA. Long term alcohol consumption induces microtubular changes in the adult rat cerebellar cortex. Brain Res. 1985;339:195–199. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90645-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman BJ, Goldstein DB. Membrane-disordering potency and anticonvulsant action of valproic acid and other short-chain acids. Mol. Pharmacol. 1984a;26:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman BJ, Goldstein DB. Genetic influences on the central nervous system depressant and membrane-disordering actions of ethanol and sodium valproate. Mol. Pharmacol. 1984b;26:547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petito CK, Pulsinelli WA. Delayed neuronal recovery and neuronal death in rat hippocampus following severe cerebral ischemia: possible relationship to abnormalities in neuronal process. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metabol. 1984;4:194–205. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1984.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluta R. Early ultrastructural changes in the basal ganglia, cerebellum and medulla oblongata after complete cerebral ischemia lasting 30 minutes. Neuropat. Pol. 1986;24:243–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratan RR, Murphy TH, Baraban JM. Oxidative stress induces apoptosis in embryonic cortial neurons. J. Neurochem. 1994;62:376–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62010376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbach L, Cremel G, Marescaux C, Warter JM, Waksman A. Valproate-induced hyperammonemia of renal origin: Effects of valproate on glutamine transport in rat kidney mitochondria. Biochem. Phramacol. 1989;38:3963–3967. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbach L, Warter JM, Rendon A, Marescaux C, Micheletti G, Waksman A. Inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation in hepatic and cerebral mitochondria of sodium valproate-treated rats. J. Neurol. Sci. 1983;61:417–423. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(83)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott WJ, Jr, Schreiner CM, Nau H, et al. Valproate–induced limb malformations in mice associated with reduction of intracellular pH. Reprod. Toxicol. 1997;11:483–493. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(97)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz RJ, Piel S, Arnold S, et al. Cerebellar hypometabolism in focal epilepsy is related to age of onset and drug intoxication. Epilepsia. 1996;37:1194–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settle EC., Jr Valproic acid- associated encephalopathy with coma (letter) Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152:1237–1238. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1236b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe C, Buchanan N. Juvenile myoclonic epilpesy: diagnosis, management and outcome. Med. J. Aust. 1995;162:133–134. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb138476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec W. Assessment of undesirable action of sodium valproate in children treated chronically due to epilepsy. Neurosciences. 1991;17:281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec W. Lipid peroxidation in experimental and clinical epilepsy and the effects of sodium valproate and vitamin E on these processes. Neurosciences. 1992;18:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec W, Jankowicz E, Sobaniec-Lotowska M. The effect of valproic acid on the morphology of the rat cerebellum and brain stem. Neuropat. Pol. 1989;27:137–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M. Hepatic encephalopathy evoked by long-term administration of sodium valproate (VPA). Ultrastructure of hepatocyte, capillaries and neuroglial cells in dentate nucleus of cerebellum. Falk Symposium No79, Portal Hypertension. 30 (Abstract) 1994a [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M. Ultrastructure of capillaries and neuroglial cells in the cerebellar cortex in rats given chronically sodium valproate. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 1994b;2:164. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M. Ultrastructural study of Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex in prolonged application of the antiepileptic drug-sodium valproate to rats. Pathol. Res. Prac. 1995;191:782–783. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M. Effects of long-term administration of the antiepileptic drug – sodium valproate upon the ultrastructure of hepatocytes in rats. Exp. Toxic. Pathol. 1997;49:225–239. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(97)80015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M, Sobaniec W. Long-term sodium valproate induced encephalopathy. Pathol. Res. Prac. 1993a;189(Suppl.):814. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M, Sobaniec W. Effect of chronic administration of sodium valproate on the morphology of the rat brain hemispheres. Neuropat. Pol. 1993b;31:153–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M, Sobaniec W. Hepatocyte ultrastructure, certain enzyme parameters and blood serum ammonia in rats given chronically and acutely sodium valproate (VPA) Falk Symposium No. 75. Cholestatic Liver Diseases 2. 1994. (Abstract)

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M, Sobaniec W. Morphological features of encephalopathy after chronic administration of the antiepileptic drug valproate to rats. A transmission electron microscopic study of capillaries in the cerebellar cortex. Exp. Toxic. Pathol. 1996;48:65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(96)80094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M, Sobaniec W, Kulak W. Rat liver pathomorphology during prolonged sodium valproate administration. Materia Med. Pol. 1993;25:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M, Sobaniec W, Kulak W. Effect of chronic administration of valproate on the ultrastructure of Bergmann's astrocytes in the cerebellar cortex. Pathol. Res. Prac. 1995;1995:782. [Google Scholar]

- Sobaniec-Lotowska M, Sobaniec H, Sendrowski K. Ultrastructure of astrocytes of the temboral lobe neocortex in the course of experimental valproate encephalopathy. Folia Morphologica. 1999;58(Suppl.):57–57. [Google Scholar]

- Stodolnik-Baranska W. Cytoplasm and cell organelles. In: Ostrowski K, editor. Histology. Warszawa: PZWL; 1995. pp. 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll AL, Banov M, Kolbrener M, et al. Neurologic factors predict a favourable valproate response in bipolar and schizoaffective disorders. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1994;14:311–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares MA, Paula-Barbosa MM. Lipofuscin granules in Purkinje cells after long term alcohol consumption in rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1983a;7:302–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1983.tb05465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares MA, Paula-Barbosa MM. Mitochondrial changes in rat Purkinje cells after prolonged alcohol consumption. A morphologic assessment. J. Submicroscop. Cytol. 1983b;7:713–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyberg J, Moskalewski S. Microtubules and the organization of the Golgi complex. Exp. Cell. Res. 1985;7:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(85)80032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian LM, Alkadhi KA. Valproic acid inhibits the depolarizing rectification in neurons of rat amygdala. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(05)80002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmings PL, Richens A. Neurotoxicology of antyepileptic drugs. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Dewolff FA, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 65. Amsterdam, London, New York: Elsevier;; 1995. pp. 495–525. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquerizo J, Romero-Rodriguez JC, Gonzalez-Roncero A, Gomez-Marcos A. Partial complex status epilepticus: diagnostic difficulties. Rev. Neurol. 1998;26:1011–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas C, Tannhauser M, Barros HM. Dissimilar effects of lithium and valproic acid on GABA and glutamine concentrations in rat cerebrospinal fluid. General Pharmacol. 1998;30:601–604. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(97)00328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voiculescu V, Hategan D, Manole E, Ulmeanu A, Georgescu D. The cerebral content of exicitatory and inhibitory amino acids in rats following withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs. Rom. J. Neurol. Psychiatry. 1994;32:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk B, Maletz J, Tiedemann M, Mall G, Klein C, Berlet C. Impaired maturation of Purkinje cells in the fetal alcohol syndrome of the rat. Light and electron microscopic investigations. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.). 1981;54:19–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00691329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SJ. Myoclonus and epilepsy in childhood: a review of treatment with valproate, ethosuximide, lamotrigine and zonisamide. Epilepsy Res. 1998;29:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(97)00080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walski M, Borowicz J. Electron microscopic investigations of cytoskeletal elements in hypothalamic endocrine neurons. Neuropat. Pol. 1988;26:233–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walski M, Celary-Walska R, Borowicz J. Studies on the hypothalamus and secretory nuclei of rat in the remote period following clinical death. J. Hirnf. 1991;32:687–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel M. Damage and death of the cell. In: Kawiak J, Mirecka J, Olszewska M, Warchol J, editors. The Basis of Cytophysiology. Warszawa: PWN; 1997. pp. 374–391. [Google Scholar]