Abstract

Background

Calls for organizational culture change are audible in many health care discourses today, including those focused on medical education, patient safety, service quality, and translational research. In spite of many efforts, traditional “top–down” approaches to changing culture and relational patterns in organizations often disappoint.

Objective

In an effort to better align our informal curriculum with our formal competency-based curriculum, Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) initiated a school-wide culture change project using an alternative, participatory approach that built on the interests, strengths, and values of IUSM individuals and microsystems.

Approach

Employing a strategy of “emergent design,” we began by gathering and presenting stories of IUSM’s culture at its best to foster mindfulness of positive relational patterns already present in the IUSM environment. We then tracked and supported new initiatives stimulated by dissemination of the stories.

Results

The vision of a new IUSM culture combined with the initial narrative intervention have prompted significant unanticipated shifts in ordinary activities and behavior, including a redesigned admissions process, new relational practices at faculty meetings, student-initiated publications, and modifications of major administrative projects such as department chair performance reviews and mission-based management. Students’ satisfaction with their educational experience rose sharply from historical patterns, and reflective narratives describe significant changes in the work and learning environment.

Conclusions

This case study of emergent change in a medical school’s informal curriculum illustrates the efficacy of novel approaches to organizational development. Large-scale change can be promoted with an emergent, non-prescriptive strategy, an appreciative perspective, and focused and sustained attention to everyday relational patterns.

KEY WORDS: organizational culture change, learning environment, informal curriculum, medical education, professional competence

INTRODUCTION

Calls for organizational culture change are resounding in a growing number of health care discourses. We are urged to improve the “informal curriculum” of medical education,1–3 create cultures of patient safety4 and customer service,5 and change the culture of biomedical research.6 Understanding culture and culture change is becoming a core competency for systems-based management and organizational leadership in health care delivery and education.7

While “culture” in a deep sense may seem unapproachable and intractable, an organization’s culture is actually manifested and sustained as everyday patterns of human interaction, for example, how one behaves in a meeting, what can or cannot be talked about with those in authority, who makes decisions, or how differences are handled.8 These patterns may arise accidentally and later become taken for granted and self-sustaining through repetition. Motivated by the recognition of suboptimal behavior patterns, typical culture change interventions, such as mandatory workshops or the implementation of an organizational “values statement,” are planned and introduced from the “top” down. They are based on a hierarchical model of organization and assumptions about management control that are not well-suited to actual human interaction.9–10

In this report, we present 1 medical school’s experience with a new approach to culture change undertaken to better align the informal and formal curricula at Indiana University School of Medicine. We describe the project’s methodology, illustrate its impact, and briefly explicate the underlying principles and contemporary social science theories on which it was based.

CASE STUDY

The Setting

Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) is the second-largest U.S. allopathic medical school with approximately 1,100 students, 1,200 full-time faculty, 1,000 residents and many hundreds of administrative staff and other personnel. Students matriculate in the basic sciences curriculum for 2 years at 1 of 9 campuses statewide. Their third and fourth-year clinical rotations take place primarily in Indianapolis at a Veterans Health Administration hospital, a public hospital, a children’s hospital, a private voluntary hospital and a university hospital.

The Project Context

In 1999, after 8 years of curricular research and review, IUSM restructured its formal curriculum and graduation requirements around 9 competencies deemed essential to excellent medical care (Table 1).11 Even as the competency curriculum was being developed, its planners recognized that the goal of graduating knowledgeable, compassionate, and respectful physicians would be undermined if the faculty and staff did not consistently embody and reinforce in their everyday conduct the moral, ethical, professional, and humane values articulated in the formal curriculum—i.e., if the informal and formal curricula did not reinforce one another. Distressingly, quantitative and qualitative data from the American Association of Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire (GQ) had been indicating that IUSM students were not experiencing a compassionate, respectful, and responsive learning environment. Many students reported feelings of alienation, disrespect, and a lack of attention to their concerns by the administration.

Table 1.

The Nine Competencies of the Indiana University School of Medicine Curriculum

| Competency | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Effective Communication |

| 2. | Basic Clinical Skills |

| 3. | Using Science to Guide, Diagnosis, Management, Therapeutics, and Prevention |

| 4. | Lifelong Learning |

| 5. | Self-Awareness, Self-Care, and Personal Growth |

| 6. | The Social and Community Contexts of Health Care |

| 7. | Moral Reasoning and Ethical Judgment |

| 8. | Problem Solving |

| 9. | Professionalism & Role Recognition |

Late in calendar year 2002, 2 new faculty with scholarly interests in professionalism and communications (TSI, RMF) received a 3-year grant from the Fetzer Institute to foster a culture of Relationship-Centered Care within the medical school. The term “Relationship-Centered Care” had been introduced by the Pew-Fetzer Task Force to call attention to respectful, collaborative relationships as a critical foundation for humane and effective medical care: relationships between patients and clinicians, among members of interdisciplinary health care teams, between the health care system and the community, and, underlying all these relationships, relationship with self.12 The IUSM project directors convened a Steering Team comprised of themselves, the Associate Dean for Medical Education and Curricular Affairs (DKL), a Project Manager (DLM), and two external consultants (ALS, PRW). The IUSM Relationship-Centered Care Initiative (RCCI) was launched in January, 2003.

RCCI Guiding Principles and Rolling Process

The Steering Team envisioned its goal as fostering a more caring, respectful, and collaborative culture throughout IUSM, enhancing the informal curriculum so it would more consistently embody and reinforce professional values. As we embarked on this initiative, three theoretical principles guided our thinking and actions.

The first principle, employing emergent design, involved pursuing change but letting the specific path of implementation emerge through collaboration between project leaders and members of the organization. From the outset, we recognized that we could not prospectively design a 3-year program to change the culture of IUSM. Rather, each action step would depend on what had happened during the preceding step, who had been engaged and what new ideas and opportunities had emerged, none of which could be known or stipulated in advance. In January of 2003, we planned only an initial step with the intention of discerning subsequent opportunities as we proceeded.

A second guiding principle, choosing to recognize and disseminate success, included the use of Appreciative Inquiry (AI), an organizational change methodology that focuses attention on the root causes of success within an organization rather than on barriers and deficiencies.13,14 AI builds more competence, confidence, and hope and is thus more motivating than traditional problem-focused approaches.

A third principle, adopting the theoretical framework of Complex Responsive Processes of Relating, grounded our work in a complexity-inspired theory of human interaction, which describes how large-scale patterns of interaction can be changed by changing local, small-scale behaviors.8,15 Organizational culture is the aggregate of myriad small patterns, which persist only if they are reenacted in each new moment. The work of culture change is to call individuals’ attention to the relational patterns being enacted in the moment, how they themselves are contributing, and how they might participate differently to give rise to different, more desirable patterns.

We began our change initiative by recruiting a “Discovery Team” (DT) to conduct appreciative interviews throughout IUSM, gathering stories of moments when IUSM’s organizational culture embodied exactly those standards of professionalism that we want our students to learn. The DT, consisting initially of 1 student, 1 resident, and 10 faculty, conducted and analyzed 80 interviews, finding 4 overarching themes: the wonderment of medicine, the importance of connectedness, passion for one’s work, and believing in everyone’s capacity to learn and grow.16 Three months into the project, the DT presented these themes and stories at a public “Open Forum”, mirroring back to the institution its strengths and offering accounts of successful relationships as models for future change. Following this event, the Steering Team reflected on what had happened and identified several next steps, which then led to more next steps, setting in motion an unplanned but hoped-for cascade of events and changes in organizational culture.

Evaluation Methods

We decided a priori to treat our project as an organizational case study, evaluating the effect of our change process with a multi-method qualitative–quantitative design. First, we sought to track events and new processes that emerged with clear and unambiguous ties to the RCCI. Two of us (TSI and DLM) kept a running project journal (“Straws in the Wind”) capturing such activities, whether or not they were sustainable. Next, our primary prospective, non-vested qualitative approach was to engage an independent observer (DWB) who reported not to the project team but to the Board of Directors of the Fetzer Institute. DWB made monthly visits from March 2004 onward to interview students, faculty, and leaders and to observe RCCI activities. After more than 2 years of activity, he prepared a report to the Fetzer Institute based on his IUSM key-informant interviews and his participant-observer field notes. A secondary prospective qualitative strategy was to harvest content from minutes taken at project meetings and from the consultants’ field notes. A fourth strategy that emerged 4 months into the project was to invite participants at each Discovery Team meeting to describe “changes in patterns of relating” they had either observed or attempted. These observations, recorded in the minutes, were later reviewed and categorized by the authors in preparation for this report using an interactive consensus-building content coding process. In this review, we specifically sought to identify all negative comments and outcomes in these sources, reviewing all the above-named sources and content from a 2007 IUSM survey of “faculty vitality”.

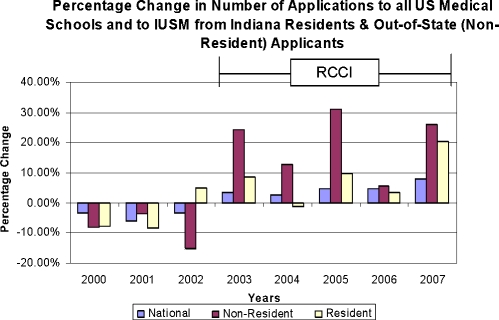

The primary prospective quantitative strategy was to track changes on selected items in students’ responses to the GQ survey. A secondary prospectively identified quantitative evaluation was tracking the number of people engaged in the project and their positions in IUSM as an indicator of the project’s engagement with the academic community. Relatively late in the project, we began to track applications to IUSM when members of the Admissions Committee who had implemented RCCI-inspired changes in committee process noticed changes in the patterns of IUSM applications and brought this indicator measure to the attention of the Steering Team.

Evidence of RCCI Impact

Five lines of evidence demonstrate the still-evolving impact of the RCCI change process. First, following the DT interviews, IUSM community members and project staff initiated a variety of new RCCI activities, none of which could have been anticipated at the outset of the initiative.

Student Appreciative Inquiry Interviews Inspired by the DT Interviews, several IUSM students decided to visit each of our 9 campuses, introducing the theories and goals of the RCCI to more than 130 students. They also interviewed 80 classmates about high-point experiences of professionalism, publishing a pocket-sized volume of narratives17 that was presented to each entering student at the 2004 IUSM White Coat ceremony. Two similar volumes have been created by subsequent cohorts of students, sustaining the flow of IUSM narrative.18,19

Admissions Committee After learning of the RCCI and the DT stories, the Admissions Committee chair recognized the important contribution of the admissions process and criteria to the school’s culture. Her committee subsequently redesigned the entire admissions process to recruit and select students with a strong relational orientation. Committee members designed, learned and practiced new admissions interview techniques that embodied IUSM formally espoused competencies with the help of “standardized applicants.”

Executive Coaching Shortly after the first Open Forum, the Dean and Executive Associate Deans requested monthly meetings with the external consultants to reflect on how their actions affected the organizational culture. Together they devised relationship-centered approaches to such executive actions as department chair evaluations, layoffs, and the implementation of mission-based management.

Other Coaching The external consultants also met with other medical school leaders (including department chairs, committee chairs, and residency directors) and more than 30 groups (including departments, committees, offices, clinical teams, alumni, and community physicians) to apprise them of the RCCI and the DT interview findings and to elicit their suggestions for and participation in further activities. At some committee meetings (e.g., the Curriculum Steering, Academic Standards, and Teacher-Learner Advocacy Committees) they invited committee members to reflect on the relational aspects and consequences of their meeting practices and committee behavior. These conversations often prompted specific new policies and procedures, for instance suspending the use of an impersonal form letter (called the “ding” letter) to inform faculty of poor student ratings of their courses or rotations.

Change-agent Development Immediately after the first Open Forum, a dozen new volunteers joined the Discovery Team, which evolved into a learning community for internal change agents, meeting monthly for coaching and support. When DT members requested additional training, the external consultants organized a year-long program called “The Courage to Lead” consisting of four 1.5-day sessions. Modeled on Parker Palmer’s teacher formation program,20 this program fosters self knowledge, authentic presence, and healthy relationships. It helps participants step outside of usual social patterns at IUSM to, in the words of Mahatma Gandhi, “be the change you want to see in the world.” Two IUSM faculty members (DKL, RMF) assumed facilitation responsibilities after receiving external training and on-site mentoring for this role. Over 50 individuals have participated in the first 3 cycles of this ongoing program. In addition, 30 members of the campus community, nominated for their high-potential as change agents, enrolled in a 5-session, 18-hour Internal Change Agent Program that focused on organizational change theories, facilitation skills, and personal awareness and offered coaching and support for change initiatives in the participants’ local work environments.

Non-starter and Unsustainable Activities As might be expected in any evolving, emergent-design initiative, some new ventures did not spread everywhere, and some interventions were not sustainable. Two attempts to spark academic department-based versions of the larger RCCI did not gather sufficient momentum or commitment to become self-sustaining. Efforts to engage residents and residency programs lagged behind efforts to engage medical students and the undergraduate program. Some initially robust activities ran their course and dissipated over time, including the Discovery Team itself. In their place, other RCCI projects have emerged (e.g., projects on professionalism and fostering humanism in health care) that broadened the scope of the initiative to include more interprofessional health care providers and clinical microsystems.

The second line of evidence for RCCI impact is derived from the June 2006 report of the external evaluator who stated:

Of note...are the many ways in which RCCI has affected the way in which IUSM conducts its daily work. A general acceptance of the value of relationship and of ‘relatedness’ appears to have permeated the administrative infrastructure of the school.21

Baldwin and the external RCCI consultants also cite key informants’ specific observations of culture change at IUSM that illustrate positive elements or trends of organizational transformation (Table 2).

Table 2.

A Sample of Observations on Noteworthy Organizational Change at IUSM Recorded by the External Evaluator and External Consultants, Grouped by Source

| Observations |

|---|

| IUSM Dean and Executive Associate Deans |

| • “RCCI offers a way of engaging people in values-based discussions.” |

| • “Crucial enabler, providing a framework and a methodology for setting up and facilitating the conversations that have had and are having such a broad impact on the school.” |

| • “We are infecting people, one at a time. There’s a significant change from two years ago. People are talking and behaving differently.” |

| • “Values and professionalism are percolating through the institution.” |

| • “I observed an enthusiasm from those involved in RCCI. I wanted to get more involved in this process so I could better understand and would thus be able to articulate what RCCI was doing for the School.” |

| • “The RCCI has helped me to be a more caring and thoughtful individual in the way I deal with other people than I otherwise would have been during this time.” |

| •“Our level of professionalism is substantially higher—what we expect from each other and from ourselves, especially in our relationships with students. I’d like to think that professionalism in our relationships with patients has been there all along, but our relationships with students and with each other have changed. We show more respect for each other; we value each other and are more sensitive to each other’s needs. These newer behaviors are becoming an expected norm.” |

| • “The practice plan is operating more like a group now. People are starting to think about the whole institution, instead of just their part.” |

| •“I think my conversations with faculty are a little bit different. I go into them now having consciously decided not to have preformed opinions. I’m more of an active listener.” |

| • “The previous sense of cynicism towards high-minded ideals is gone. Behaviors that are detrimental to relationships are much less evident than they were before at a faculty level. Expressions of anger and disrespect are less acceptable parts of our culture.” |

| IUSM Committee Members |

| • “We feel we are changing the nature of our conversations.” |

| • “We are asking how we can do this better.” |

| • “We are learning to check in, to learn from each other.” |

| • “Reframe from the usual crime and punishment scene to one of being more present, more respectful.” |

| • “Humanizing the experience...Rules without relationship create resentment.” |

| Faculty at Large |

| • “It’s a wonderful idea and program, taking on organizational and cultural change in such a large and complex organization. Having been at some of the meetings, the thing I’ve been most impressed about is how the initiative has accomplished one of its goals, achieving effects at two levels, from the top down and bottom up. The effect as shown in the students’ stories [in an online journal] has been amazing, and from being at meetings with the Deans, to have gotten their complete buy-in and support is nothing short of a huge success.” |

| Residents |

| • “At the Discovery Team meetings there were...all the “relational tools” people brought in—ways of seeing things, understanding a different point of view, that I learned from. I’m trying to incorporate these into my ways of doing things and it has broadened my skills considerably.” |

| • “I did notice that I said something to a resident recently and they said “Oooh, I like the words you used”, and it was something someone said during the coaching sessions and I thought, “Maybe I AM learning something.” |

| • “Quite a bit of effort was placed in including people from all levels of the school.” |

| Medical Students |

| • “Before becoming aware of the RCCI, I’d look at things in the school and pick out all the bad things. I’d say, ‘I don’t like doing this exercise, I don’t get anything out of it and I don’t understand why I have to do it.’ Now I realize that my complaining does no good. In general, I try to focus on more positive things. For example, I just had very positive autopsy exercise yesterday, so when I go to school today, I’ll tell my friends how great it was—it was not easy and it took a long time, but it’s what medicine is all about. So they’ll go in with a good attitude. That’s part of continuing the dialogue.” |

| • Clinic was “different from usual. The attending is spending more time and being more interested in me and the patient.” |

The third line of evidence for RCCI impact derives from an analysis of participants’ observations during the monthly DT meetings. Table 3 shows representative descriptions of changes attributed to the RCCI. These comments cluster around 3 themes:

New meeting formats and practices. IUSM faculty and staff have introduced new practices into standing meetings, teaching conferences, and other activities to make these events more relational and collaborative. The appreciative practice of sharing success stories has spread widely in both administrative and educational contexts.

New institutional procedures and programs. These range from faculty development programs for new hires to new student leadership positions.

Communication about culture. Faculty, residents and students have created new communications vehicles that raise awareness of the changing IUSM culture, including an RCCI newsletter, monthly informational emails, and others.

Table 3.

Illustrative Examples of Changes at IUSM Observed by Members of the RCCI Steering and Discovery Teams and Attributed (at least in part) to the RCCI

| Observed Changes |

|---|

| New Meeting Formats and Practices |

| • New meeting practices to “humanize” meetings of the standing committees of IUSM (e.g., checking-in, noticing successes and appreciative debriefings) are spreading. |

| • The use of paired interviewing, reflective narratives and appreciative inquiry is spreading (e.g., chief resident orientation, resident workshops on professionalism, and elements of new NIH-funded Behavioral and Social Sciences Integrated Curriculum. |

| • Staff members in the Office of Medical Education and Curricular Affairs created and implemented a plan to be mindful of every personal interaction and to manifest a relationship-centered culture in all of their work. |

| • The competency directors and coordinators transformed themselves into a “relationship-centered learning community” seeking to live the values of the competency curriculum as a way of disseminating them across the school and the state. |

| • Methods from the RCCI are now being adapted to quality and service improvement initiatives in facilities across the health system. |

| New Institutional Procedures and Programs |

| • The Dean includes rigorous data on the work environment in performance reviews for department chairs and conducts these reviews in a relationship-centered manner. |

| • A major school-wide initiative in mission-based management was designed and implemented with the explicit intention of fostering partnership, engagement, shared decision-making and trust. |

| • The Admissions Committee developed new criteria and new interviewing methods to select relationally oriented applicants. |

| • The Academic Standards Committee changed its approach to reporting and addressing poor ratings on student course evaluations from a form letter (known as the “ding letter”) to a more personal and collaborative conversation. |

| • A fifty-hour career development course has been created for newly hired faculty that incorporates relationship-centered principles and emphasizes the importance of mentorship. |

| • Two leadership development programs (a year-long series of quarterly retreats called The Courage to Lead and a 15 hour Internal Change Agent Program) have been added to the roster of faculty development activities. Originally conducted by the external consultants, these are now internally planned and facilitated. |

| • Students requested and received approval for a permanent Dean-appointed student leadership position intended to promote the RCCI and to foster mindfulness of relationship in campus activities. |

| • After protesting reduced library hours, students responded successfully to an invitation to develop an alternative plan that met necessary financial constraints. |

| Communication about Culture |

| • The School’s weekly newsletter, Scope, now includes a column entitled “Mindfulness in Medicine” that uses stories of actual faculty and trainee experiences to focus attention on relationships and professionalism. |

| • Students created a special Bulletin Board in the student center devoted to promoting student interest in the activities and events of the RCCI. |

| • A group of students published a book of students’ stories about professionalism that was presented to incoming students at the White Coat Ceremony. In each of the subsequent two years, students created and published similar books presenting art, stories, and poems by IUSM faculty, residents, and students reflecting humanistic aspects of doctoring. |

It is noteworthy that in all sources of archival information reviewed for this report, negative comments about the RCCI were far fewer in number than positive ones. Rather than cynical or dismissive statements about the RCCI, the available records captured only ‘negative comments’ that seem to represent certain individuals’ initial concerns or healthy skepticism (Table 4):

Initial skepticism regarding the RCCI likelihood of success. An early area of concern regarding the RCCI was whether a culture change strategy focused on improving professional relationships and relying on an emergent process of diffusion, could succeed. Several individuals closely related to the RCCI expressed doubts. However, these doubts were replaced by support for the project as the change process unfolded over time.

Skepticism regarding the personal impact of RCCI activities. Participants in RCCI activities were sometimes uncomfortable initially with the nature of those activities, particularly those involving reflection and self-disclosure. In 3 years of data collection we found only 1 comment from a participant who felt there was no value to an RCCI activity. Most people became comfortable with personal sharing over time, often finding it to be personally transformative.

Skepticism regarding RCCI methods. The nature of the RCCI’s emergent design strategy was unfamiliar and disconcerting to some. People were encouraged to embody and enact a new way of being in their work environments, drawing on their own self-knowledge and vision of an improved, relational organizational culture, but no blueprints for specific action were provided. Over time, as individuals began to request personal coaching, faculty development, and personal formation programs, much of the confusion of the first year of the initiative diminished.

Skepticism regarding the ability of the RCCI to transform all aspects of IUSM culture. As participants embraced a focus on relationship and worked to encourage improved relationships in their professional lives, they noted that some environments seemed less amenable to culture change than others. We attempted to identify and work in areas of readiness, recognizing that if a critical mass emerged in some microsystems, change was likely to diffuse to other areas in time.22

Table 4.

Negative Comments about RCCI Organizational Change at IUSM Taken from Steering and Discovery Team Minutes, Personal Interviews, Formal Reports, and Articles, Grouped By Theme

| Comments |

|---|

| Initial Skepticism Regarding the RCCI Likelihood of Success |

| • “When initially briefed on RCCI, my first reflex was that this was too “warm and fuzzy” and that people would trivialize it no matter how well-intentioned the program. ...To my surprise, we experienced an outpouring of truly remarkable stories that created a groundswell of pride and inspiration among participants.” |

| •IUSM Dean |

| •Academic Medicine, 2007; 82:1094–1097 |

| • “What I honestly thought might be a “noble failure” when I accepted this assignment, has amazed me with its power and, yes, its unique form of rigor. It has truly engendered the hope that this “experiment” might lead to long needed changes in medical education and patient care. |

| •RCCI External Evaluator |

| •2004 Report to the Fetzer Institute |

| • Trusting others did not become my strong suit. At the outset of the Relationship-Centered Care Initiative, I was solidly in this career-long orientation. .... To my surprise, people in high-risk environments were just as likely to take positive steps as others, perhaps because the felt need resided there. |

| In spite of being one of the principal leaders for RCCI, the weight of responsibility for designing project plans and was not upon my shoulders. I would take my initiatives within my own environment but expect that institutional ‘emergence’ would serve as the optimal intelligence for program activities institution-wide. |

| •President and CEO, Regenstrief Institute |

| •Interview with RCCI external consultants, 2006 |

| •Skepticism Regarding the Personal Impact of RCCI Activities |

| •I participated in the RCCI when I could, but got nothing out of it. |

| •IUSM Faculty |

| •Response to RCCI survey on faculty vitality, 2007 |

| • When I was asked to participate in the RCCI Courage to Lead program, I was totally unaware of what the program was about and what it entailed. The first session was very difficult for me to find a comfort level in the group. I had never participated in such a discussion group with people I barely knew and some I didn’t know. As the year progressed, I realized that I was looking forward to the retreats and found it much easier to express myself and join in the group. I found the sessions ... helped me to reflect on my feelings and look at how I was not attending to my own needs. ... I will always remember the sessions and continue to try and incorporate the ideas of the sessions in my life and career. |

| •Clinician, Co-Chair of key IUSM administrative committee |

| •Response to RCCI survey on faculty vitality, 2007 |

| Skepticism Regarding the Methods of the RCCI |

| • At each [Discovery Team] meeting the consultants asked us what changes we were noticing in the IUSM culture, and what we were trying. I wasn’t sure that any positive elements of the IUSM culture that I was noticing were the direct results of the RCCI, or just my decision to consciously attend to the positive. I was also not sure what new “things” I should be trying. I had always tried to be friendly and helpful to my colleagues, but I knew this wasn’t enough. What else was I supposed to be doing? |

| •Medical Education Staff, currently a core member of the RCCI Leadership Team |

| •From written description of experience with the RCCI, 2006 |

| Skepticism Regarding Ability of the RCCI to Transform All Aspects of IUSM Culture |

| • Recorded in the Discovery Team minutes, 2005: |

| •Another DT member expressed appreciation for the DT environment but is feeling unsuccessful helping it to spread elsewhere. There is not a widespread perception that communication and relationship are important. The working environment seems to be better in community hospitals than academic ones, but there’s less teaching taking place in those settings. It’s validating to see others who care about this. |

| • Recorded in the Discovery Team minutes, 2006: |

| •Two DT members shared some frustration with their inability to fully engage physicians (most notably more experienced staff physicians) in their recent departmental and organizational change efforts. Potential reasons for a lack of engagement include time constraints, a lack of highly scientific quantitative evidence regarding potential benefits to patients and a lack of understanding of how this approach might benefit their practice. The group discussed ...potential approaches. |

A fourth convergent line of evidence suggesting that the RCCI has had an impact at IUSM is the growth in participation in RCCI over time. From early 2003 to the end of calendar year 2005, the number of participants in RCCI activities grew from the 6 initial team members to more than 900 faculty, students, residents, staff, allied health professionals and patients. Participation rates have been particularly high among members and leaders of IUSM’s standing committees, involving 33% of all committee members and 52% of the most actively engaged faculty members (those serving on 2 or more committees). For the 10 committees concerned with education and student life, 90% of the chairs and 71% of the members have participated.

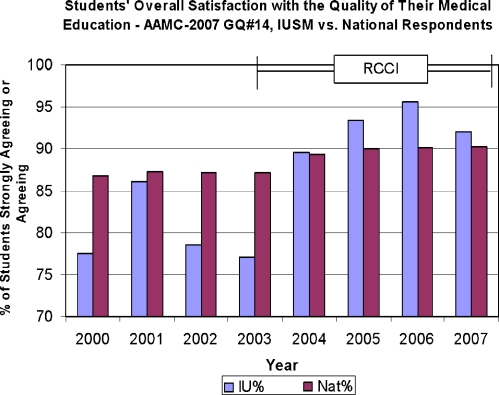

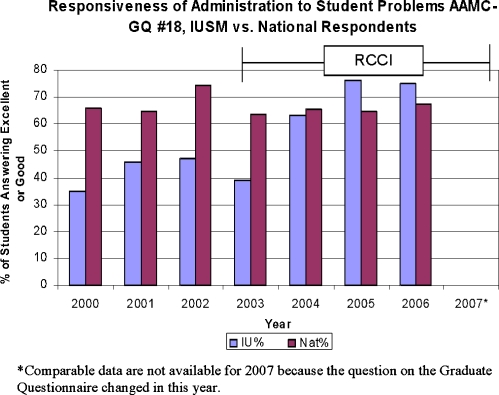

The fifth line of evidence for the RCCI’s impact comes from the IUSM Graduation Questionnaire data. Starting in 2004, responses to the item on the AAMC GQ assessing students’ overall satisfaction with their medical education rose sharply from low baseline annual assessments to annual reports above the national average—a level of performance historically unprecedented at IUSM (Fig. 1). Scores assessing student satisfaction with the administration also rose significantly (Fig. 2). Trends in medical school applications offer additional supporting evidence. Medical school applications generally rose nationally after 2003, but IUSM has seen a more pronounced rise in out-of-state and in-state applications than its peers (Fig. 3). While we would not attribute this overall doubling in applications solely to the RCCI, our Admissions Committee and Executive Associate Dean for Education prominently cited the RCCI and the competency curriculum as the 2 key contributors to this remarkable growth.23,24

Figure 1.

Trends in Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) and national student responses to the American Association of Medical Colleges Graduate Questionnaire item # 14: “Indicate whether you agree or disagree with the following statement: Overall, I am satisfied with the quality of my medical education.” The Relationship-Centered Care Initiative at IUSM began in the middle of the 2002–2003 academic year.

Figure 2.

Trends in Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) and national student responses to the American Association of Medical Colleges Graduate Questionnaire item # 18: “Indicate your level of satisfaction with the following: Responsiveness of administration to student problems.” The Relationship-Centered Care Initiative at IUSM began in the middle of the 2002–2003 academic year.

Figure 3.

Percentage change in Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) applications from Indiana residents and out-of-state applicants compared to all US medical schools. The Relationship-Centered Care Initiative at IUSM began in the middle of the 2002–2003 academic year.

DISCUSSION

This case study demonstrates that culture change is possible in a large public school of medicine. Specifically, it shows how a medical school community fostered a relational environment that more closely reflects the values of its competency-based curriculum. Employing a strategy of “emergent design,” we started with a modest intervention to prompt reflection on everyday interactions, then traced and supported the subsequent “ripples of change” that engaged the interest and energy of individuals throughout the IUSM community.

The RCCI began with an Appreciative Inquiry that called attention to exemplary professional behavior. In response, individuals and committees became more mindful and intentional about their behavior and discovered that sometimes they were unwittingly enacting values and modeling behaviors they did not want to pass on to students. Many new patterns (e.g., “check-in” at the start of meetings or routinely telling success stories) spread rapidly through the organization. These many small changes appear to be contributing to a change in the overall experience of working and learning at IUSM. After 3 years, changes were evident in such core institutional practices and procedures as the conduct of meetings, performance reviews, medical student selection, and staff communications. Students’ overall satisfaction with their educational experience climbed dramatically, and a wide variety of individuals noticed positive changes in their work and learning environments.

The news that the informal curriculum can be intentionally changed will be welcomed by medical educators whose carefully designed programs on professional values are sometimes undermined by unprofessional behavior elsewhere in their organizations. But this case is also of wider interest. It illustrates important, seemingly paradoxical, and non-traditional principles of organizational culture change that could be applied widely.

The emergent design principle acknowledges that it is not possible to predict or control the path by which new patterns of behavior will spread through an organization. An organization is not a machine that can be designed, but rather a dynamic web of conversations within which patterns of meaning (knowledge) and patterns of relating (culture) evolve over time through a non-linear, self-organizing process. These patterns can be influenced, but they cannot be programmed or controlled.8,15

As we began our initiative, we could not know which committees or processes were ripe for change or which people were ready to engage. Rather than targeting specific committees and individuals of our choosing, we created a process by which they could identify themselves. We avoided the ill will and wasted effort engendered by forcing change on people who are not ready for it. Instead, we found people who were attracted to the vision and encouraged their initiatives—activities which then attracted more people, growing a critical mass. Not everything that was ventured prospered. In fostering organizational change, false starts and dead-ends are to be expected, not-knowing is normal (even virtuous), and success depends on persistence and ongoing reflective discernment.

The second principle, grounded in the organizational method of Appreciative Inquiry, is to change what is not working in an organization by paying more attention to what does work.13,14 Conventional problem solving seeks to identify and eliminate the root causes of undesirable outcomes. Its focus on deficiencies often elicits anxiety, shame, and defensiveness, all of which impede behavior change.25 Instead, we called attention to existing competence and capacity at IUSM. This enhanced the organization’s self-image, bolstered confidence, and created a hopeful and self-fulfilling expectation that positive change was indeed possible.

The third principle, approaching large-scale organizational change by focusing on everyday behaviors, expresses the major insights of complexity theory.8,15 A hallmark of non-linear dynamics (complexity) is that small disturbances in patterns—such as small changes in the conduct of a meeting or the sharing of information—can amplify and spread spontaneously and unpredictably, sometimes resulting in transformative change of the kind that seems to have occurred at IUSM.

Like all organizational case studies, this study has a number of limitations. First, because there were many contemporaneous initiatives and changing circumstances at IUSM (e.g., the evolution of leadership, the contributions of the RCCI, maturation of the competency curriculum), it is obviously inappropriate to attribute changes in our culture to any single factor. Instead, like ecologists tracking change in an environmental niche, we sought to use indicator measures and to invoke multiple lines of evidence to describe and triangulate change while remaining cautious about isolated cause-and-effect inferences. Second, participant observation data are subject to the biases (perspectives) of the observers. Some of our key observers were more than just participants in the RCCI process, they were initiative leaders and could have been more likely to notice changes and ascribe them to the initiative. For that reason, in this report we have attempted to use “peer checks” from our external evaluator and tracking measures derived from routinely collected student reports to triangulate and balance participant–observer data. Third, every institution is unique in its history, structure, and the composition of its academic medical center community. The outcomes of a culture-change initiative in our setting are of unknown generalizability.

These cautionary notes not withstanding, we believe that a culture-change initiative at 1 medical school succeeded in engaging many faculty and organizational leaders within the school, stimulated a remarkable efflorescence of activities that enhanced its environment, and exerted a favorable impact on a variety of organizational performance indicators—including admissions, student perceptions of school’s responsiveness, and their perceptions of the overall quality of their education. In our setting, it was reinvigorating to stop “just talking” about the hidden curriculum and, instead, to try to do something to improve it. Like others, we found that culture change is an unpredictable non-linear process that is not amenable to linear, top–down approaches. We were able to foster large-scale organizational change with a flexible, emergent, and non-prescriptive strategy; an appreciative perspective; and focused and sustained attention to everyday relational patterns.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the editors and reviewers of JGIM for helping us improve the clarity of the presentation.

Conflict of Interest Statement The authors have the following relationships with for-profit institutions: Ann H. Cottingham, MAR, none; Anthony L. Suchman, MD, MA, paid consultant to the Relationship-Centered Care Initiative; Debra K. Litzelman, MA, MD, none; Richard M. Frankel, PhD, grant received from the Zimmer Corporation; David L. Mossbarger, MBA, none; Penelope R. Williamson, ScD, paid consultant to the Relationship-Centered Care Initiative; DeWitt C. Baldwin Jr., MD, none; Thomas S. Inui, ScM, MD; grant received from the Zimmer Corporation.

Footnotes

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1577-5

References

- 1.Hafferty F. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73:403–407. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inui TS. A Flag in the Wind: Educating for Professionalism in Medicine. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern DT, Papadakis M. The developing physician—becoming a professional. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1794–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leape LL, Berwick DM. Safe health care: are we up to it? We have to be. BMJ. 2000;320:725–726. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oswald WW. Creating a service culture. Healthc Exec. 1998;13(3):64–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zerhouni EA. Translational and clinical science—time for a new vision. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1621–1623. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff. 2002;21(5):103–111. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suchman AL. A new theoretical foundation for relationship-centered care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S40–S44. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stacey RD. Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics. 3rd edn. Harlow, England: Financial Times Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Streatfield PJ. The Paradox of Control in Organisations. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Indiana initiative: Physicians for the 21st century. Indianapolis: Indiana University School of Medicine; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tresolini CP, Pew-Fetzer Task Force . Health Professions Education and Relationship-centered Care. San Francisco, CA: Pew Health Professions Commission; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins JM, Mohr BJ. Appreciative inquiry: Change at the Speed of Imagination. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooperrider DL, Srivasta S. Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Res Organ Change Dev. 1987;1:129–169. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stacey RD. Complex Responsive Processes in Organizations. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suchman AL, Williamson PR, Litzelman DL, et al. Towards an informal curriculum that teaches professionalism: transforming the social environment of a medical school. J Gen Int Med. 2004;19:501–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taking Root and Growing: Becoming a Physician at Indiana University School of Medicine. Indianapolis: Indiana University School of Medicine; 2004.

- 18.Reflecting Caring Attitudes through Action. Indianapolis: Indiana University School of Medicine; 2006.

- 19.Helping Hands: Reflections on Humanities in Medicine. Indianapolis, Indiana University School of Medicine; 2007.

- 20.Palmer PJ. The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life. 1st. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldwin DC. Evaluation Report to the President and Board of Trustees of the Fetzer Institute. June 30, 2006.

- 22.Rogers E. Diffusion of innovation. Fifth Ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Litzelman DK, Cottingham AH. The new formal competency-based curriculum and informal curriculum at Indiana University School of Medicine: overview and five-year analysis. Acad.Med. 2007;82:410–21. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803327f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brater DC. Infusing professionalism into a school of medicine: perspectives from the Dean. Acad Med. 2007;82:1094–1097. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181575f89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deming WE. Out of the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study; 1986. [Google Scholar]