Summary

Background

Colonoscopy is a screening modality for the early detection of colonic polyps and cancers but is underutilized, particularly among minorities.

Objective

To identify potential barriers to screening colonoscopy among low income Latino and white non-Latino patients in an urban community health center.

Design, participants, and approach

We conducted semistructured interviews with a convenience sample of patients 53 to 70 years old, eligible for colorectal cancer screening that spoke English or Spanish. Open-ended questions explored knowledge, beliefs, and experience with or reasons for not having screening colonoscopy. We performed content analysis of transcripts using established qualitative techniques.

Results

Of 40 participants recruited, 57% were women, 55% Latino, 20% had private health insurance, and 40% had a prior colonoscopy. Participants described a wide range of barriers categorized into 5 major themes: (1) System barriers including scheduling, financial, transportation, and language difficulties; (2) Fear of pain or complications of colonoscopy and fear of diagnosis (cancer); (3) Lack of desire or motivation, including “laziness” and “procrastination”; (4) Dissuasion by others influencing participants’ decision regarding colonoscopy; and (5) Lack of provider recommendation including not hearing about colonoscopy or not understanding the preparation instructions.

Conclusions

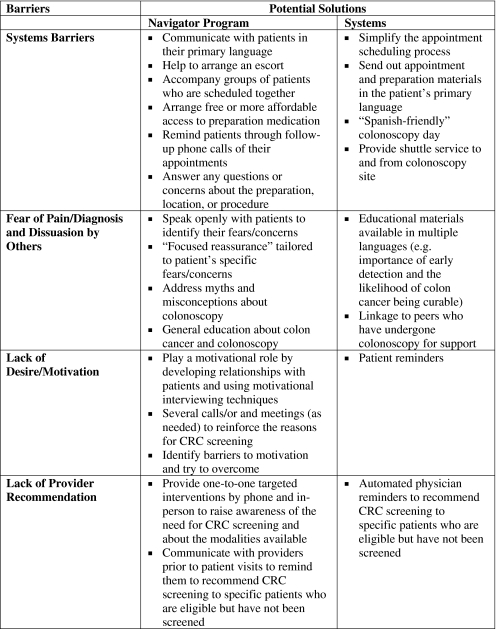

Understanding of the range of barriers to colorectal cancer screening can help develop multimodal interventions to increase colonoscopy rates for all patients including low-income Latinos. Interventions including systems improvements and navigator programs could address barriers by assisting patients with scheduling, insurance issues, and transportation and providing interpretation, education, emotional support, and motivational interviewing.

KEY WORDS: colon cancer, screening, colonoscopy, Latino, barriers, patient navigation, cultural competency, qualitative

BACKGROUND

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States.1–4 Despite evidence that reductions in CRC morbidity and mortality can be achieved through early detection and treatment, over two thirds of patients are not diagnosed until the disease has advanced.5 Whereas CRC screening is recommended to reduce the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer, screening rates are relatively low in general and particularly for racial and ethnic minorities.2 Colonoscopy is an accepted screening modality for detecting and treating premalignant lesions and preventing CRC,6–8 although disparities between racial/ethnic minorities and whites in screening colonoscopy rates are even greater than other CRC-screening modalities.2,3,9 For Latinos, lower CRC-screening rates may be responsible for their later stage of disease at presentation and poorer prognosis than white non-Latinos.10–13

A number of studies have explored potential barriers to CRC screening in the medical and public health literature.1–4,9,14–20 Most of these have focused on combined modalities of CRC screening including fecal occult blood testing in addition to colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy.1–4,9 Among studies exploring barriers for specific ethnic or racial minorities, most have focused on African Americans.1,9,21–26 One study identified focused specifically on colonoscopy as a screening modality but enrolled few minority patients.14 Studies of combined modality CRC screening that included Latinos suggest that they may have some specific barriers such as limited English proficiency.3 However, most of the barriers expressed were similar to those found among other populations.

Prior quality assessment efforts at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have identified lower rates of screening colonoscopy for Latinos compared to non-Latino whites (unpublished data). A large proportion of the Latino patients at MGH are cared for at MGH Chelsea Health Care Center (MGH Chelsea). It is a low-income, heavily immigrant community health center where the CRC-screening rates are significantly lower for all patients (49% compared to 65% at the other MGH practices); therefore, we sought to explore the potential barriers these patients face to obtaining a colonoscopy. We were interested in the perspectives of both Latino and non-Latino white patients who had either had a colonoscopy or were eligible but did not have the procedure. Ultimately, our goal was to use this information to identify a set of potential interventions including system improvements and a patient navigator program that could increase the rate of screening colonoscopy and eliminate the racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in this aspect of primary care.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative, descriptive study of patients who were eligible for colorectal cancer screening to obtain in-depth information about potential barriers to undergoing a screening colonoscopy. The study was approved by the Partners HealthCare System Institutional Review Board. Verbal consent was obtained from participants before commencing the formal interview.

Setting

Interviews were conducted at MGH Chelsea, a large, multispecialty community-based health center that has been part of the MGH network of clinical care sites since 1971. MGH Chelsea serves as the largest source of primary health care for the town of Chelsea, MA. Each year, more than 150,000 visits are made to the health center by nearly 37,000 patients. Chelsea is a multiethnic, low-income community situated 5 mi north of Boston. During recent decades, it has served as a gateway community for many refugees and immigrants from Latin America, Bosnia, Somalia, the Middle East, and Africa. Chelsea, according to the 2000 U.S. census, has the largest percentage of Latinos (50%) of any city in the state.

Interviews

We developed an interview guide (Fig. 1) based on previous studies of CRC screening among racial and ethnic minorities and informal interviews with health care providers at MGH Chelsea.1–4 A research assistant was trained to use this guide to conduct semistructured one-on-one patient interviews of approximately 10–15-minute duration. The interview began by collecting demographic information including age, sex, race/ethnicity, country of origin, primary language, and insurance status. We asked about race and ethnicity (Latino—yes/no) separately; however, all Latino participants self-identified as either “white” or “other,” so for this study, we will refer to them simply as “Latino.” The research assistant then asked participants to describe what they knew about colorectal cancer and CRC-screening methods—particularly colonoscopy. If a participant had no knowledge about colorectal cancer and CRC-screening methods, the interview was ended only after probing to be certain that the patient was not knowledgeable about these topics. Further open-ended questions explored patients perspectives about colonoscopy, experience with the procedure (one’s own or that of others), and reasons for not having one. The full range of topics reviewed are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 1.

Interview guide.

Figure 2.

Barriers to screening colonoscopy and potential solutions.

Sampling/Recruitment and Analysis

A convenience sample of patients in the Adult Medicine Department, both in the urgent care and continuity care waiting rooms, were approached by a bilingual (English- and Spanish-speaking) research assistant (Gamba) with the assistance of medical technicians who were not part of the study. Patients were selected if they were 53–70 years of age. We excluded patients that did not speak either English or Spanish, were too physically or mentally disabled to participate, or were not eligible for colorectal cancer screening because of prior total colectomy. Other non-Latino racial/ethnic groups were not excluded from the study provided they were proficient in English or Spanish. No eligible subjects refused to participate in the interview study. Initially, patients were interviewed regardless of whether or not they had already received a colonoscopy, either for screening or for diagnostic purposes. However, after interviewing 20 patients, the sample was somewhat skewed, and we began to oversample patients that had not had a colonoscopy. The research assistant described the study to patients, provided them with a fact sheet about the study, answered any questions they had, and obtained verbal consent for their participation. Recruitment and interviews were performed during October and November of 2006.

All interviews were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews with Spanish-speaking patients were translated by the research assistant who is also a certified and experienced medical interpreter. We analyzed the transcripts after each set of 5 interviews was completed (i.e., 5, 10, 15, 20, etc.). After analyzing 40 interview transcripts, we determined that saturation had been achieved with no new themes emerging from the last 10 interviews.

We used content analysis to synthesize findings and identify key themes. We analyzed the data manually using the “framework” method as presented by Ritchie and Spencer.27 The framework method includes 5 stages: familiarization, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting, and mapping/interpretation. To become familiar with the data, 2 of the researchers (Peters-Lewis and Percac-Lima) listened to the tapes and corrected the transcripts as necessary. Preliminary themes began to emerge during the familiarization phase. This then led to the development of an initial thematic framework. The analysis team (Green, Peters-Lewis, and Percac-Lima) held weekly meetings where data were reviewed and discussed and new insights were shared that led to revision of existing themes and generation of new ones. Interrater reliability about the themes and supporting data was always greater than 90% among the research team. Disagreements were resolved through discussion until the group achieved mutual consensus. Each of the 3 team members performed theme counts, and at their final meeting, the team achieved consensus on all the themes and supporting data.

RESULTS

Study Participants

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. The age of the participants ranged from 53 to 70 years (mean 60.3). The sample included 40 participants—23 female (57.5%) and 17 male (42.5%). Fifty-five percent of participants self-identified as Latino, predominantly from Puerto Rico, Colombia, Guatemala, Cuba, and Mexico. All Latino patients identified Spanish as their primary language. The majority of participants reported having health insurance (72.5%), whereas 25% were uninsured, and 2.5% had unknown insurance status. Among those with health insurance, 37.9% had Medicaid (Mass Health), 17.2% had Medicare, 17.2% had both, and 27.6% had private insurance. Among uninsured participants (25%), most were enrolled in a Free Care program whereby hospitals in Massachusetts provide free services for eligible uninsured patients including colonoscopy.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic Information

| White (n = 18) | Latino (n = 22) | Total (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years)* | 61.4 | 59.3 | 60.3 |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Male | 50.0 | 36.4 | 42.5 |

| Female | 50.0 | 63.6 | 57.5 |

| Language spoken with navigator (%) | |||

| English | 100.0 | 0.0 | 45.0 |

| Spanish | 0.0 | 100.0 | 55.0 |

| Insurance (%) | |||

| Private/HMO | 27.8 | 13.6 | 20.0 |

| MassHealth | 33.3 | 22.7 | 27.5 |

| Medicare | 11.1 | 13.6 | 12.5 |

| MassHealth/Medicare | 11.1 | 13.6 | 12.5 |

| No insurance/Free Care | 16.6 | 31.8 | 25.0 |

| Other (unknown, refused) | 0.0 | 4.5 | 2.5 |

| Received colonoscopy (%) | 44.4 | 36.4 | 40 |

*Age range 53–70

Most participants who reported having a prior colonoscopy had the procedure to follow-up on specific gastrointestinal complaints such as constipation or bleeding. It is not known if these were actual symptoms or if they were used by providers to ensure that the procedure would meet the criteria for reimbursement. Sixteen of the 40 patients in our study had received a colonoscopy—8 of 18 white patients and 8 of 22 Latino patients. Compared to other participants, Latino men in our sample had less to say overall about the topic of colonoscopy. A review of the interview transcripts showed that Latino men often provided brief yes or no responses to some of the questions, and their mean word count for the entire interview was 77 compared to 175 for all other groups combined.

Findings

Thirty-four of 40 participants (85%) had heard about a colonoscopy, and many were able to verbalize the age (within 5 years) at which their first screening colonoscopy was performed. Five themes emerged from analysis of the interviews representing categories of patients’ barriers to receiving screening colonoscopy. The themes are listed in order of frequency: (1) system barriers, (2) fear of pain or diagnosis, (3) lack of desire or motivation, (4) dissuasion by others, and (5) lack of provider recommendation.

System Barriers

Barriers that we categorized as “System Barriers” represented the most common theme and were mentioned by 10 participants (25% of all patient interviewed and 40% of patients who did not have a colonoscopy). These included scheduling, financial, and transportation difficulties that prevented participants from having a colonoscopy. Scheduling was the most common barrier identified by participants and included several different components. Participants reported that although they had agreed to have a colonoscopy, they did not receive an appointment time. In some cases, appointments times were rescheduled without adequate notice. Therefore, participants were not able to arrange their schedules to accommodate the change. Other participants were managing multiple comorbid conditions and found it difficult to make time for another appointment that required 24 hours of preparation. One white male (WM) participant stated: “Too many appointments…you know they are not good times of day.”

Participants had concerns about both the timeliness with which information describing the logistics of the procedure was available to them and the clarity of the information. A Latino female (LF) participant said: “They told me it is near Charles River Plaza. I’m not sure where it is.” One participant (LF) reported being unable to complete the scheduled colonoscopy because of inadequate information about when to stop eating before the procedure.

Participants reported the cost of the preparation (as much as $46.00) as another barrier. On a limited budget, some were forced to make a choice between a colonoscopy and other necessities such as food or medications. Participants also reported that transportation was challenging. They often had difficulty finding someone who could take time from work and to escort them home after their procedure. One participant (WM) stated: “the doctor last year wanted me to have one. But I didn’t have 1 because it required that I have someone take me home.”

There were times when more than 1 system barrier were reported, as in this example with respect to the preparation for colonoscopy. “The first time because I got no information. Then when I went to get the medication, it was expensive and it was too late, I did not have time to take the medications” (LF).

Fear of Pain or Diagnosis

Fear of pain or the diagnosis of cancer was also a common theme that emerged from the dialogue with participants. Four participants expressed fear that the colonoscopy would be painful. A white female (WF) participant stated: “I don’t want it to hurt.” Another participant (WM) stated: “I am very cowardly. I go to the doctor and after that I get pains everywhere without him doing anything to me.” Other participants expressed a fear of actually being diagnosed with colon cancer and that they would prefer not to know (n = 3). One participant (LF) verbalized fear of pain during the procedure and fear of a cancer diagnosis. This participant’s quote (WF) best illustrates a perspective of denial: “What I don’t know won’t hurt me. No I want nothing to do with cancer. Not even to test or screen for it...nothing. I don’t want to bother. I’m really against it all. If I ever had it, I would never let them cut me or anything like that...nothing.”

Inadequate pain control during the procedure was an issue that 4 of the 16 participants who had a colonoscopy reported. Some of these participants made comments suggesting that their negative experience would influence others in making a decision to have a colonoscopy. For example, 1 participant (LF) stated: “It was done without sedation. It was horrible. I do not recommend it.”

Lack of Desire/Motivation

Some patients reported simply not having the desire or motivation to have a colonoscopy done despite receiving a recommendation from their health care provider. Many of them reported receiving educational information about the procedure and the rationale for having it done but just not getting around to it (n = 5). One participant (WM) stated: “I am still thinking about it.” Other participants cited “laziness” or “procrastination” as barriers to colon cancer screening. “I just haven’t made the appointment...I’m a procrastinator like everyone else” (WM).

Dissuasion by Others

“Dissuasion by others” describes the manner in which perceptions of family and friends influenced the participant’s decision whether or not to have a colonoscopy. Three participants reported that a friend or family member had a colonoscopy and their negative experience with the procedure dissuaded the participant from having it. One participant (WF) stated: “I heard so many people got it done and they ended up with problems. They said they never had problems and all of a sudden they had that done and forget it.” Another participant (LF) stated: “people have told me that it is dangerous and others say something may go wrong.” Of note, an equal number of participants (n = 3) reported that their family member or friend had a positive experience and encouraged them to have the procedure.

Lack of Provider Recommendation

This theme describes participants who reported that they were never informed about colonoscopy by their providers. The following quote (WM) best illustrates this: “I’ve been coming here for thirty years. It’s never been mentioned.” Whereas this theme only emerged during 2 interviews, it is significant because the 2 patients correlated provider recommendation with the importance of the test. One Latino male participant (LM) stated, “Well if the doctor doesn’t mention it, then I guess I don’t need it?” The quote illustrates the importance of physicians’ recommendations (or lack thereof) in influencing patient attitudes toward procedures and illuminates the potential role of health care providers in reducing disparities in procedure utilization.

DISCUSSION

The broad goal of this study was to explore patient-perceived barriers to receiving a screening colonoscopy as identified by low-income Latino and white non-Latino individuals in an urban community health center. More specifically, we hoped to gain a better understanding of these barriers to help us implement systems changes and a bilingual patient navigator program to improve screening colonoscopy rates for all patients at the MGH Chelsea, especially Latinos. It should be noted that we found no clear differences in barriers between Latino and white non-Latino participants except for the obvious language barriers and the fact that Latino men seemed to talk less about these issues overall than other groups.

We were not surprised that system barriers were the most commonly reported problem that patients reported facing in obtaining a colonoscopy. These include barriers such as complicated scheduling processes, financial difficulties, and problems with transportation. These have been reported previously3,14,15,28,29 and were also described by primary care providers at MGH Chelsea in earlier qualitative interviews (unpublished work). However, our study did not highlight “missing work” as a major barrier despite the fact that this has been cited in other studies.30,31 It is possible that most of the patients in our sample were either unemployed or retired.

Fortunately, systems barriers are also probably the most amenable to (and often the primary target of) “patient navigator” programs.32–37 Such programs are designed to help patients navigate complex health care systems. They may have the flexibility to help patients address transportation and financial barriers, for example, by arranging escorts, accompanying groups of patients who can be scheduled together, and arranging free or affordable access to colonoscopy preparation medications kept on site. They can also call patients to remind them of their appointments, answer any questions about the bowel preparation, location, or procedure itself. Other system improvements might include simplifying the scheduling process, developing prep forms in Spanish and other languages, and scheduling “Spanish-friendly” colonoscopy days attended by bilingual nurses and gastroenterologists when possible or involving on-site interpreters.

Fear was another common barrier in our study and can be considered together with “dissuasion by others.” Similar to previous literature among various sociocultural groups, patients described fear of the procedure itself (particularly the pain associated with it) but also concerns about embarrassment, preparation, and potential complications.1–4,9,14,17,18,25,38,39 Fear of the diagnosis of cancer has been reported less often in the literature but was an important theme in our study. Patients may prefer not to look for problems that are not currently bothering them, especially if they think of cancer as an incurable disease, as many patients do.19,38–41 This may be based in part of a fatalistic attitude common among many patient groups1–3,29,42–46 and not specific to Latinos, despite unsubstantiated literature promoting this as a Latino cultural issue. In fact, some literature suggests that fatalism is more an issue of lower socioeconomic status rather than culture.3,15,38 Dissuasion by others often represents fears that are not specifically referred to as such and may represent the way that the patient chose to describe their fears rather than a separate theme. For example, mentioning that others have said colonoscopy is dangerous is another way of stating one’s own fear of the potential dangers.

To address these fears, patients should be provided a safe environment to encourage open discussion about what concerns them. It may be helpful to use “focused reassurance,” a term we have coined that describes a process of reassuring patients with information pertaining to their own specific concerns. This may include clarifying myths or false information about colonoscopy, educating patients about the process itself, and discussing approaches to minimizing the feared outcome. For example, a patient who fears pain because of the procedure can be provided with options for pain management and sedation and could also speak with others who have had a colonoscopy for reassurance. Fear of the diagnosis of cancer may warrant providing patients with focused education about early detection and the likelihood of colon cancer being curable.

The lack of desire or motivation to have a colonoscopy is a particularly challenging barrier. Whereas clinicians provide the initial recommendation for screening, they may or may not have the time to provide ongoing motivation. This is another area where navigator systems have proven useful.32–37 They can play a motivational role by forming relationships with patients, calling and meeting with them, and not allowing the issue of CRC screening to fall off the patient’s “radar.” This can help to overcome the inertia, which keeps many otherwise willing patients from getting screened. Clinicians and navigators alike could benefit from some basic training in motivational interviewing to help them address this challenge.47

Only 2 patients in our study had not heard about colonoscopy, specifically reporting that they had not received a recommendation for one from their primary care provider. Given the relatively low rate of CRC screening in the overall health center population, we had expected this to be more commonly reported. Other studies among diverse populations have shown much greater knowledge deficits about CRC screening.2,4,9,16–18,20,23–25,28 Our study’s high rate of awareness might be related to the fact that we recruited patients in the waiting rooms of the health center, potentially selecting patients who are better connected to the health care system. In addition, we did not characterize the level of knowledge among those who had heard of colonoscopy, which may have uncovered substantial knowledge deficits in this group. Automated provider reminders and clinician education may be useful in assuring that patients who are eligible receive a recommendation for a screening colonoscopy from their primary care provider.

Our study has several limitations. The data that emerged from this qualitative study provide a deeper understanding of the barriers to colon cancer screening that exist within this group of participants but cannot be generalized to the larger population. We used a single interviewer, which could introduce bias based on this individual’s style and emphasis or de-emphasis of particular topics. Of the patients who had received colonoscopies, some were for diagnostic purposes rather than screening. Whereas it is likely that these patients experience similar barriers, it is also possible that this could have affected our results somewhat. Findings from this study should help inform a larger quantitative study stratifying by race/ethnicity and focusing specifically on screening colonoscopy.

To reduce racial and ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening and to improve the rates of screening for all patients, it is important to understand the reasons why some patients are not receiving colonoscopies. Our findings support and add to the literature in this area by focusing on low-income Latino and white patients in an urban community health center and their barriers to receiving colonoscopy specifically. We propose a set of recommendations for intervention based on these barriers, many of which have been reported in other populations. Whereas each population is unique, addressing barriers to screening colonoscopy seems to include common themes that may provide a foundation for more tailored interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Elyse Park for help with the qualitative methodology and Sarah Abernathy-Oo and Joan Quinlan for assisting in the early conceptualization of the study and ongoing support. This paper was presented at the 30th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Medicine in April 2007. This study was funded by Jane’s Trust and the Clinical Innovation Award: Translating Clinical Insights into Improved Patient Care at the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Greiner K, Born W, Nollen N, Ahluwalia J. Knowledge and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among urban African Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):977–983. doi: 10.1007/s11606-005-0244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh J, Kaplan C, Nguyen B, Gildengorin G, McPhee S, Perez-Stable E. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Latino and Vietnamese Americans. Compared with non-Latino white Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):156–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman M, Ogdie A, Kanamori M, Canar J, O’Malley A. Barriers and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening among Mid-Atlantic Latinos: focus group findings. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shokar N, Vernon S, Weller S. Cancer and colorectal cancer: knowledge, beliefs, and screening preferences of a diverse patient population. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Facts and Figures 2006. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieberman DA, Weiss DG. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555–560. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vijan S, Hwang E, Hofer T, Hayward R. Which colon cancer screening test? A comparison of costs, effectiveness, and compliance. Am J Med. 2001;111(8):593–601. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00977-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green P, Kelly B. Colorectal cancer knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(3):206–215. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ries L, Eisner M, Kosary C, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jemal A, Clegg L, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101(1):3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman-Goetz L, Breen N, Meissner H. The impact of social class on the use of cancer screening within three racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Ethn Dis. 1998;8(1):43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilliland F, Hunt W, Key C. Trends in the survival of American Indian, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic white cancer patients in New Mexico and Arizona, 1969–1994. Cancer. 1998;82(9):1769–1783. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980501)82:9<1784::AID-CNCR26>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denberg T, Melhado T, Coombes J, et al. Predictors of nonadherence to screening colonoscopy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):989–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Malley AS, Beaton E, Yabroff KR, Abramson R, Mandelblatt J. Patient and provider barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the primary care safety-net. Am J Prev Med. 2004;39(1):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klabunde C, Schenck A, Davis W. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among Medicare consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(4):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klabunde C, Vernon S, Nadel M, Breen N, Seeff L, Brown M. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Med Care. 2005;43(9):939–944. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173599.67470.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brouse C, Basch C, Wolf R, Shmukler C. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: an educational diagnosis. J Cancer Educ. 2004;19(3):170–173. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce1903_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes-Rovner M, Williams GA, Hoppough S, Quillan L, Butler R, Given CW. Colorectal cancer screening barriers in persons with low income. Cancer Pract. 2002;10(5):240–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.105003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf R, Zybert P, Brouse C, et al. Knowledge, beliefs, and barriers relevant to colorectal cancer screening in an urban population: a pilot study. Fam Commun Health. 2001;24(3):34–47. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawsin C, Duhamel K, Weiss A, Rakowski W, Jandorf L. Colorectal cancer screening among low-income African Americans in East Harlem: a theoretical approach to understanding barriers and promoters to screening. J Urban Health. 2007;84(1):32–44. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipkus I, Rimer B, Lyna P, Pradhan A, Conaway M, Woods-Powell C. Colorectal screening patterns and perceptions of risk among African-American users of a community health center. J Commun Health. 1996;21(6):409–427. doi: 10.1007/BF01702602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz M, James A, Pignone M, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among African American church members: a qualitative and quantitative study of patient-provider communication. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.James A, Campbell M, Hudson M. Perceived barriers and benefits to colon cancer screening among African Americans in North Carolina: how does perception relate to screening behavior? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarker Prev. 2002;11(6):529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agrawal S, Bhupinderjit A, Bhutani M, et al. Colorectal cancer in African Americans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(3):515–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powe B, Finnie R, Ko J. Enhancing knowledge of colorectal cancer among African Americans: why are we waiting until age 50? Gastroenterol Nurs. 2006;29(1):42–49. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. Analysing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge; 1993. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yepes-Rios M, Reimann J, Talavera A, Ruiz de Esparza A, Talavera G. Colorectal cancer screening among Mexican Americans at a community clinic. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(3):204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polite B, Dignam J, Olopade O. Colorectal cancer model of health disparities: understanding mortality differences in minority populations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2179–2187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coronado G, Thompson B. Rural Mexican American men’s attitudes and beliefs about cancer screening. J Cancer Educ. 2000;15(1):41–45. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson B, Coronado G, Neuhouser M, Chen L. Colorectal carcinoma screening among Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites in a rural setting. Cancer. 2005;103(12):2491–2498. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nash D, Azeez S, Vlahov D, Schori M. Evaluation of an intervention to increase screening colonoscopy in an urban public hospital setting. J Urban Health. 2006;83(2):231–243. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9029-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, Freund KM. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population. A patient navigation intervention. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):359–367. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinberg ML, Fremont A, Khan DC, et al. Lay patient navigator program implementation for equal access to cancer care and clinical trials: essential steps and initial challenges. Cancer. 2006;107(11):2669–2677. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(1):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahm AK, Sukhanova A, Ellis J, Mouchawar J. Increasing utilization of cancer genetic counseling services using a patient navigator model. J Genet Couns. 2007;16(2):171–177. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jandorf L, Gutierrez Y, Lopez J, Christie J, Itzkowitz S. Use of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinic. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2):216–224. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beeker C, Kraft J, Southwell B, Jorgensen C. Colorectal cancer screening in older men and women: qualitative research findings and implications for intervention. J Commun Health. 2000;25(3):263–278. doi: 10.1023/A:1005104406934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price JH. Perceptions of colorectal cancer in a socioeconomically disadvantaged population. J Commun Health. 1993;18(6):347–362. doi: 10.1007/BF01323966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong-Kim E, Sun A, DeMattos M. Assessing cancer beliefs in a Chinese immigrant community. Cancer Control. 2003;10(5 Suppl):22–28. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan C, Park E, Cortes D. Beliefs, knowledge, and behavior about cancer among urban Hispanic women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;18:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Powe B, Hamilton J, Brooks P. Perceptions of cancer fatalism and cancer knowledge: a comparison of older and younger African American women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24(4):1–13. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spurlock W, Cullins L. Cancer fatalism and breast cancer screening in African American women. ABNF J. 2006;17(1):38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greiner K, James A, Born W, et al. Predictors of fecal occult blood test (FOBT) completion among low-income adults. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):676–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Powe B, Finnie R. Cancer fatalism: the state of the science. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(6):454–465. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Powe B. Perceptions of cancer fatalism among African Americans: the influence of education, income, and cancer knowledge. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 1994;7(2):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]