Abstract

Objective

To determine whether the integration of an automated electronic clinical portfolio into clinical clerkships can improve the quality of feedback given to students on their patient write-ups and the quality of students’ write-ups.

Design

The authors conducted a single-blinded, randomized controlled study of an electronic clinical portfolio that automatically collects all students’ clinical notes and notifies their teachers (attending and resident physicians) via e-mail. Third-year medical students were randomized to use the electronic portfolio or traditional paper means. Teachers in the portfolio group provided feedback directly on the student’s write-up using a web-based application. Teachers in the control group provided feedback directly on the student’s write-up by writing in the margins of the paper. Outcomes were teacher and student assessment of the frequency and quality of feedback on write-ups, expert assessment of the quality of student write-ups at the end of the clerkship, and participant assessment of the value of the electronic portfolio system.

Results

Teachers reported giving more frequent and detailed feedback using the portfolio system (p = 0.01). Seventy percent of students who used the portfolio system, versus 39% of students in the control group (p = 0.001), reported receiving feedback on more than half of their write-ups. Write-ups of portfolio students were rated of similar quality to write-ups of control students. Teachers and students agreed that the system was a valuable teaching tool and easy to use.

Conclusions

An electronic clinical portfolio that automatically collects students’ clinical notes is associated with improved teacher feedback on write-ups and similar quality of write-ups.

KEY WORDS: portfolio, feedback, medical education

INTRODUCTION

Communication of clinical information in writing is a key learning objective of medical schools.1 Historically, when a patient is admitted, students have provided written patient history and physical exams (write-ups) on clinical clerkships that reflect their ability to collect, organize, analyze, and communicate important patient information.2,3 Faculty members and residents (students’ “teachers”) review the written work and provide students with feedback on their write-ups. Students report that feedback on their write-ups during their clinical clerkships is associated with high-quality teaching but is infrequently done.4 Innovations to help teachers provide more frequent and in-depth feedback are often initially successful but may not be widely adopted and sustained.5–7 Educators have turned to portfolios, consisting of manual logs of student–patient encounters, to monitor student progress. Whereas portfolios show promise to track student experiences and provide opportunities for teacher feedback, students find the manual process of uploading information to the portfolio as “intrusive busywork.”8 Feasible and acceptable means of providing students with effective feedback on their clinical encounters are needed that allow for automated capture of a student’s experiences.

We have developed an electronic portfolio to monitor medical students’ clinical encounters. The system automatically captures every clinical note written by students in the electronic record on their patients, including history and physicals, progress notes, procedure notes, and discharge summaries. We hypothesized that the use of the electronic portfolio can improve the feedback that teachers provide medical students on their initial history and physicals of newly admitted patients (write-ups) and improve the quality of the write-ups. We conducted a randomized controlled trial of students on third-year medicine and pediatric clerkships to compare use of the portfolio system with the usual student practice of printing write-ups for teacher feedback.

METHODS

Setting

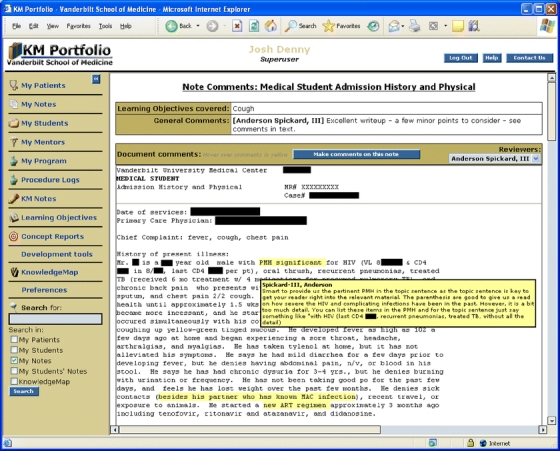

Third-year students on the inpatient portion of their Internal Medicine clerkship (8 weeks) and Pediatric clerkship (6 weeks) at the Vanderbilt School of Medicine are assigned to a medical team composed of a second- or third-year resident, an intern, and one other student (third-year clerk or fourth-year subintern). Students evaluate a new patient and provide a write-up of their evaluation every third to fourth day, giving each student an approximate total of 16 write-ups during the Internal Medicine clerkship and 12 write-ups during the Pediatric clerkship. All students are required to submit a write-up to the medical record on every patient to whom they are assigned. Clerkship goals call for a student to receive feedback from their teachers on at least one third to one half of his or her write-ups. All students, attendings, and residents are informed of this goal before the clerkship. The Clinical Learning Portfolio (“Portfolio”) system was created to facilitate this process. Portfolio is a World Wide Web application that automatically receives all student notes (history and physicals, progress notes, procedure notes, discharge summaries) written on the wards and the clinics in the electronic medical record (EMR). Students can view their notes on a personalized web page. To capture notes from hospitals and clinics not using the EMR, students can create notes in Portfolio via a web-based documentation tool that provides standard templates for common document types (e.g., history and physical or discharge summary). Attendings and residents assigned to students during the clerkship may review these notes to give feedback by writing comments online that are saved to the student’s personal Portfolio page but not to the patient’s medical record (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Screenshot of teacher comments. The yellow texts in the clinical notes are areas in which the mentor has made comments.

Intervention

We conducted a randomized trial over 5 months (August 2005–December 2005) among third-year medical students at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine who were participating in required Internal Medicine or Pediatric clerkships. The Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. Students were block randomized using a random number generator to 2 groups. Students in both groups submitted their write-ups to the EMR, which were captured in their Portfolio. Students in the control group, however, did not have access to Portfolio; they handed printed copies of their patient write-ups to their attendings and residents for feedback. Students in the intervention group received input from attendings and residents who viewed the students’ notes on Portfolio and provided feedback by typing corrections and comments onto the write-up online (Fig. 1). Attendings and residents were not randomized because of logistical difficulties of ensuring both students on 2-student teams were in the same study group assignment. An attending or resident may have worked with students in either or both groups and more than once over the course of the study. Attendings and residents who worked with students in the Portfolio group had the option of e-mail notification when their students created a new history and physical document. Students received automatic e-mail notification when a teacher submitted comments on a write-up on Portfolio. Evaluators and course directors were blinded as to which group each student belonged to.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included a brief teacher survey, student survey, and analysis of the quality of student write-ups. Teachers rated the frequency, quality, and personal satisfaction of the feedback they gave to students on their write-ups as compared to prior rotations when they taught students. Students rated the frequency and quality of feedback received on their write-ups and the ease of use of Portfolio (Appendix). Two clerkship directors (AS and JG), blind to student group assignment, independently rated the quality of 2 write-ups from each student. Write-ups from students in both groups were presented to the raters in identical fashion on paper to mask group assignment. The raters used a previously reported write-up evaluation instrument that consists of a 4-point rating scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 4 (excellent) to evaluate 13 items and to calculate a 13-item mean write-up score derived from the average score of the 13 items.9 We scored 142 notes with 28 overlapping between both reviewers. Finally, we logged all activity by students and teachers on Portfolio, capturing the notes of students from both groups in the study and the comments from teachers of students randomized to the Portfolio group.

Statistical Analysis

We used Fisher’s exact test to compare survey responses between the 2 groups and Student’s t test to compare continuous outcomes. A sample size of 33 teacher–student pairs has 90% power to detect a 20% difference in feedback frequency between the groups on the teacher survey. A sample size of 40 student write-ups provides 90% power to detect a 10% difference in overall quality of the student write-ups assuming similar standard deviations reported in prior uses of this instrument.9 All statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Participants

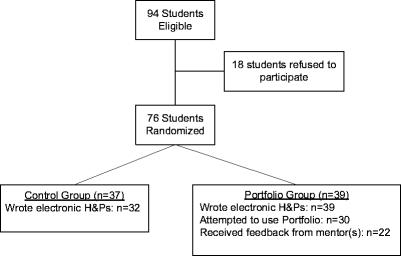

Seventy-six of 94 invited students (81%) at Vanderbilt agreed to participate in the study (Fig. 2). There were no differences in demographic data between study groups (Table 1) or between study participants and students who chose not to be in the study (data not shown). Thirty of 39 students in the Portfolio group accessed Portfolio to review notes and request teacher feedback; 8 of these students never received teacher feedback through the system. Among students in the Portfolio group, there were no differences in the demographic data between students who received feedback (n = 22) and those who did not receive feedback via Portfolio (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Participant flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Student Participants

| Characteristic | Control n = 37 | Portfolio n = 39 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender (no., %) | 17 (46%) | 19 (49%) | 0.82 |

| Age (average, 95% CI) | 25.2 (24.7–25.8) (24.6–25.8) | 26.0 (25.3–26.7) | 0.08 |

| Ethnic group (no., %) | |||

| Arabic | 1 (3%) | 3 (8%) | 0.25 |

| Asian or Asian American | 4 (11%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Black | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| East Indian | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | |

| White | 29 (78%) | 30 (77%) | |

| Prior postgraduate medical training (no., %) | 4 (11%) | 7 (18%) | 0.52 |

| Prior clerkships (no., %) | |||

| 0 | 7 (20%) | 8 (21%) | 0.95 |

| 1 | 19 (54%) | 23 (59%) | |

| 2 | 9 (26%) | 8 (21%) | |

| Residency choice (no., %) | |||

| Primary care* | 13 (35%) | 20 (51%) | 0.75 |

| Surgical fields | 11 (30%) | 9 (23%) | |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 4 (11%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Radiology | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Emergency medicine | 3 (8%) | 3 (8%) | |

| Neurology or Psychiatry | 3 (8%) | 3 (8%) | |

| Other | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

*Primary care is defined as Medicine, Pediatrics, Medicine/Pediatrics combined residency, or Family Medicine.

Teacher Survey

Seventy-seven out of approximately 120 (64%) teachers responded to our survey regarding feedback experiences with students. There were no differences in demographic data between teachers who worked with students in the control group and Portfolio group (Table 2). By intention-to-treat analysis, teachers reported giving more detailed and more frequent feedback using Portfolio than by traditional means (Table 3). Including only teachers who used the system in the analysis yielded even more favorable results: “more frequent feedback” 61% Portfolio versus 12% control (p < 0.01), “more detailed feedback” 61% Portfolio versus 12% control (p < 0.01), and “more satisfied with feedback I provided” 44% versus 10% control (p = 0.01). All teachers who used Portfolio agreed or strongly agreed that the system made it easier for them to view and comment on students’ notes. During the study period, 14 teachers worked with students assigned to both study groups (Portfolio and control) during different times of the study. Nine of these 14 teachers reported they had given more frequent and detailed feedback to the student in the Portfolio group, but only 1 teacher reported more frequent and detailed feedback to the student in the control group. Eight of these 14 teachers were also more satisfied with their feedback via the Portfolio system compared to 1 attending who was more satisfied with her feedback given via the traditional paper means. As 1 attending physician stated, “Portfolio is so much easier that it actually provides an unfair advantage for the students who have it.”

Table 2.

Characteristics of Teachers Responding to Survey

| Characteristic | Control Group (n = 42) | Portfolio Group (n = 35) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender (no., %) | 20 (48%) | 22 (63%) | 0.25 |

| Experience (no., %) | |||

| Intern | 5 (12%) | 4 (9%) | 0.53 |

| R2–R3* | 20 (48%) | 11 (31%) | |

| Clinical instructor | 6 (14%) | 6 (17%) | |

| Assistant professor | 5 (12%) | 3 (9%) | |

| Associate professor | 2 (5%) | 3 (9%) | |

| Professor | 4 (10%) | 8 (23%) |

*R2–R3 indicates a second- or third-year resident in medicine or pediatrics.

Table 3.

Teacher Survey Responses

| “Compared to prior rotations” | Control n = 42 | Portfolio n = 35 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| “I gave more frequent feedback”* | 12% | 41% | 0.014 |

| “I gave more detailed feedback” | 12% | 41% | 0.010 |

| “I was more satisfied with feedback I provided” | 10% | 32% | 0.045 |

*Teachers answered the question, “Compared to prior rotations, I gave less, same, or more frequent feedback.” Similarly, they noted “less,” “same,” or “more” to rate detail of feedback and satisfaction with feedback provided compared to prior rotations.

Student Survey

Sixty-four students (84% response rate; control n = 28/37, Portfolio n = 36/39) completed the survey. As Fig. 1 illustrates, 17 students in the Portfolio group never received the intervention. By intention-to-treat analysis, there were no differences between groups in frequency of feedback and the insightfulness of the feedback. Analysis of the 22 students who received the intervention showed that more students received feedback on more than half of their write-ups (70% Portfolio vs 39% control, p = 0.001). Seventy-five percent of students in the Portfolio group agreed or strongly agreed that the system was a valuable teaching tool and 70% agreed that it increased the amount of feedback that they had received. All but 1 student found Portfolio easy to use. Computer logs confirmed that teachers provided comments on 122 out of a total of 269 (45%) histories and physicals written by students in the Portfolio group.

Analysis of Student Write-Ups

All students in both groups used the standard history and physical template in the EMR. We rated the last 2 write-ups from each student on the rotation (n = 142 write-ups). There were no significant differences between the groups (Table 4). When combining all 3 assessment and plan ratings (prioritizing problems, formulating a differential, and discussing the diagnoses and formulating a plan), students in the Portfolio group did better, with 32% of Portfolio group students receiving the maximum score compared with 8% of control students (p = 0.036). In the set of overlapping notes scored by both reviewers (28 notes representing 364 individual ratings), the exact agreement between the 2 raters over the 13 items for each note was 62%; the agreement between raters within 1 point on the 4-point scale for all items was 97.5%. The unweighted Kappa was 0.38; the weighted Kappa, which takes into account the degree of disagreement between observers, was 0.55.10 Prior studies using this rating instrument has demonstrated an unweighted Kappa of 0.14.9

Table 4.

Student Write-up Score

| Item | Item Means* (CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (32 Students, 64 Write-Ups) | Portfolio (39 Students, 78 Write-Ups) | p | |

| Chief complaint clearly stated | 3.06 (2.89–3.24) | 3.07 (2.91–3.24) | 0.97 |

| History of present illness organized chronologically | 3.27 (3.07–3.45) | 3.39 (3.24–3.54) | 0.30 |

| Symptoms fully characterized and clearly written | 2.98 (2.80–3.16) | 3.19 (3.02–3.36) | 0.10 |

| Pertinent positives and negatives included in history of present illness | 2.87 (2.67–3.07) | 2.93 (2.76–3.09) | 0.64 |

| Sufficiently detailed past medical history with qualifying information | 3.33 (3.17–3.49) | 3.27 (3.14–3.41) | 0.56 |

| Family–social history appropriately documented | 3.41 (3.25–3.56) | 3.51 (3.38–3.63) | 0.33 |

| Organized, complete review of systems | 3.26 (3.04–3.48) | 3.20 (3.04–3.36) | 0.67 |

| General description of patient | 3.14 (2.97–3.32) | 3.16 (2.98–3.34) | 0.87 |

| Detailed physical exam | 3.27 (3.10–3.43) | 3.34 (3.20–3.48) | 0.51 |

| Relevant data presented clearly | 3.09 (2.97–3.21) | 3.14 (3.03–3.26) | 0.52 |

| Prioritized problem list of all issues identified in history, exam, and studies | 3.27 (3.10–3.43) | 3.36 (3.21–3.51) | 0.42 |

| Formulates a complete differential diagnosis for the priority patient problems | 2.73 (2.49–2.98) | 2.92 (2.66–3.18) | 0.31 |

| Discusses the likelihood of diagnosis based on the clinical findings and initiates a therapeutic plan | 2.88 (2.66–3.11) | 3.05 (2.82–3.28) | 0.31 |

| 13-Item mean write-up score† | 3.12 (3.03–3.21) | 3.19 (3.11–3.28) | 0.24 |

*Write-up evaluation instrument used a 4-point scale (1 = poor, 4 = excellent).

†Thirteen-item mean write-up score was calculated as the mean of the 13 items for a given write-up.

DISCUSSION

The Portfolio system automatically collects students’ write-ups from the EMR to allow teachers to provide medical students with feedback comments online anytime, anywhere, which are saved for student review. In this study, teachers and medical students who used the system reported more frequent and detailed feedback on student write-ups. Teachers were more satisfied with the feedback provided, and students thought the system was a valuable learning tool. Nearly everyone thought the system was easy to use. Importantly, for those who used the tool, the Portfolio system improved clerkship goals for the amount of feedback provided to students on patient write-ups, often exceeding the clerkship’s goals for feedback frequency. The quality of write-ups of students who received feedback via Portfolio was similar to write-ups of students who received feedback by traditional means. Subanalysis showed that more students in the Portfolio group achieved a maximal score on the assessment and plan component of the write-ups.

There are few studies on lasting delivery systems for feedback to students on clinical rotations. The use of feedback index note cards to student clerks on medicine and pediatric rotations improves the specificity of feedback given to students about their cases, which satisfies learners, but has not been widely adopted by busy teachers hampered by time constraints.7,11 An electronic portfolio, connected to the EMR, provides a sustainable approach. Notes are automatically captured by the system during clinical workflow. Teachers and students are automatically notified when a note enters the system and when feedback comments are made. Documents are saved so that students may review their work and monitor personal progress.

Limitations caution the interpretation of these results. Many of our measures included student and teacher self reports. We were able to confirm the student self-reported frequency of feedback from attendings and residents by reviewing Portfolio logs to determine that teachers had made comments on nearly half of all notes of students in the Portfolio group. Our work is limited to 1 institution; the impact of Portfolio on student performance at different training sites would be preferable study endpoints. Nevertheless, the Portfolio tool at a single institution allows ratings from numerous examiners simultaneously and on repeated occasions, which is necessary to assess and address precision in the estimates of performance.2,9,12 Indeed, Portfolio can be expanded to other universities. Because Portfolio includes a stand-alone web-based note writer, it does not require a hospital EMR.

This study highlights some of the complexities in conducting medical education research. The clerkship environment contains many different people and unseen, interacting forces. Controlling for potential confounders and overcoming noncompliance with group assignment is difficult, especially when introducing a new workflow while also attempting to study it. Nine students assigned to Portfolio never used the system. Another 8 students never received a feedback comment from teachers to whom they were assigned. We used intention-to-treat analysis to maintain group similarity, preserve balance among prognostic factors, and reflect real-world experience in which not all participants adhere to the intervention. This analysis possibly underestimated the current intervention effect because measures that only included students and teachers who used the system were significantly in favor of Portfolio. A final complexity in medical education concerns outcome measures. We were careful to use measures relevant to the intervention: feedback on write-ups and quality of write-ups. Other important learner outcomes, such as clerkship grades, were not considered to be influenced by the intervention. More studies are needed to determine the key factors that determine student write-up performance and whether these factors affect other important learning outcomes.

Adoption of effective new technology can be slow. Since implementation, we have met with course directors, attendings, residents, and students to address barriers to system adoption. We learned that many teachers and students thought that students’ write-ups should not be posted in the EMR. We pointed out the educational value of Portfolio, the system’s Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant protections, and the newly created institutional policy for students to post their write-ups in the EMR. We learned that teachers were concerned that Portfolio limited their feedback activity to written communication, not personal interaction with students. Portfolio does not replace face-to-face contact; rather, the medium encourages conversations between teachers and learners as they reflected on comments recently posted on the student’s Portfolio. Still, many teachers prefer not to use a computer interface. At the moment, we do not mandate that attendings and residents use Portfolio; rather, we offer it as a suitable alternative to paper methods to fulfill their responsibility to provide feedback to students on their write-ups. Based on this experience, we are building a comprehensive electronic Portfolio that now contains 240,000 student and resident clinical notes. The goal is to allow teachers to efficiently assess learners and monitor progress toward learning goals5,13 as advocated nationally8,14. As a first step, we use a tool that automatically delivers patient write-ups electronically to teachers who can provide feedback online on their own schedule, leading to more frequent and detailed feedback.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by a grant from the National Library of Medicine (LM007450-04).

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Appendix

Teacher questionnaire:

Compared to prior rotations, the number of this student’s written notes (H&P’s, progress notes) I evaluated was more, the same, or less.

Compared to prior rotations, the detail of feedback that I gave on this student’s written notes was more, the same, or less.

Compared to prior rotations, the satisfaction I have in the feedback I provided to this student on his/her notes is more, the same, or less.

- If the Learning Portfolio System was used, the system made it easier for me to view and comment on student’s notes.

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree - If the Learning Portfolio System was used, the system allowed me to provide better feedback on student’s notes.

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree

Student Questionnaire:

- I received feedback on this percentage of my H&P write-ups:

<25% 25–50% 51–75% >75% - I received insightful feedback (in any form) concerning my write-ups:

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree

If you were in the Portfolio Group:

- The system is a valuable teaching tool.

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree - Having my write-ups on Portfolio increased the amount of feedback I received.

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree - The system was easy to use.

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree

References

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges. Learning Objectives for Medical Student Education: Guidelines for Medical Schools (MSOP Report). Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.McLeod PJ. Assessing the value of student case write-ups and write-up evaluations. Acad Med. 1989;64:273–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Woolliscroft JO, Calhoun JG, Beauchamp C, Wolf FM, Maxim BR. Evaluating the medical history: observation versus write-up review. J Med Educ. 1984;59:19–23. [PubMed]

- 4.Torre DM, Simpson D, Sebastian JL, Elnicki DM. Learning/feedback activities and high-quality teaching: perceptions of third-year medical students during an inpatient rotation. Acad Med. 2005;80:950–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Daelmans HE, Overmeer RM, van der Hem-Stokroos HH, Scherpbier AJ, Stehouwer CD, van der Vleuten CP. In-training assessment: qualitative study of effects on supervision and feedback in an undergraduate clinical rotation. Med Educ. 2006;40:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kogan JR, Bellini LM, Shea JA. Have you had your feedback today. Acad Med. 2000;75:1041. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Schum TR, Krippendorf RL, Biernat KA. Simple feedback notes enhance specificity of feedback to learners. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3:9–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bardes CL, Wenderoth S, Lemise R, Ortanez P, Storey-Johnson C. Specifying student–patient encounters, web-based case logs, and meeting standards of the liaison committee on medical education. Acad Med. 2005;80:1127–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kogan JR, Shea JA. Psychometric characteristics of a write-up assessment form in a medicine core clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Brenner H, Kliebsch U. Dependence of weighted Kappa coefficients on the number of categories. Epidemiology. 1996;7:199–202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Paukert JL, Richards ML, Olney C. An encounter card system for increasing feedback to students. Am J Surg. 2002;183:300–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lye PS, Biernat KA, Bragg DS, Simpson DE. A pleasure to work with—an analysis of written comments on student evaluations. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1:128–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Supiano MA, Fantone JC, Grum C. A Web-based geriatrics portfolio to document medical students’ learning outcomes. Acad Med. 2002;77:937–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Corbett EC, Whitcomb M. The AAMC Project on the Clinical Education of Medical Students: Clinical Skills Education. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2004.