Abstract

Objective

Little is known regarding how providers should use information about intimate partner violence (IPV) to care for depressed patients. Our objective was to explore what depressed IPV survivors believe about the relationship between abuse, mental health, and physical symptoms and to elicit their recommendations for addressing depression.

Design

Focus group study.

Patients/Participants

Adult, English-speaking, female, Internal Medicine clinic patients with depressive symptoms and a history of IPV.

Interventions

Thematic analysis using an inductive approach (consistent with grounded theory), at a semantic level, with an essentialist paradigm.

Measurements and Main Results

Twenty three women participated in 5 focus groups. Although selected because of their depression, participants often felt their greatest concerns were physical. They acknowledged that their abuse history, depression, and physical complaints compound each other. They appreciated the need for health care workers to know about their depression and IPV history to get a “full picture” of their health, but they were often hesitant to discuss such issues with providers because of their fear that such information would make providers think their symptoms were “all in their head” or would encourage providers to discount their pain. Participants discussed difficulties related to trust and control in relationships with providers and gave recommendations as to how providers can earn their trust.

Conclusions

Understanding a patient’s IPV history may allow providers to develop a better therapeutic relationship. To treat depression adequately, it is important for providers to reassure patients that they believe their physical symptoms; to communicate respect for patients’ intelligence, experience, and complexity; and to share control.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0606-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: intimate partner violence, depression, pain, physical symptoms, qualitative research, physician–patient relationship

BACKGROUND

There is little doubt that intimate partner violence (IPV) affects the health of a large proportion of women, with lifetime prevalence rates of IPV in clinical settings ranging between 21% and 55%1 and a large literature documenting the association between IPV, negative health outcomes, and increased health costs.2 Studies consistently demonstrate increased rates of depression, suicidality, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse in women who have experienced IPV,3 as well as an association between IPV and poorer overall general health,4–8 greater numbers of physical symptoms,6,9–12 and a wide array of specific physical symptoms.5,6,8,13 Although there are many studies documenting increased overall health care costs in women with IPV histories as compared to nonabused women,14–16 depressed IPV survivors appear to seek less mental health care than depressed women without a history of abuse.17,18 It remains unclear why survivors of IPV hesitate to seek mental health services or how they understand the relationship between physical and mental symptoms. Consequently, it remains unclear how primary care providers might better address mental health issues and physical symptoms among patients with histories of IPV.

There is a large qualitative literature on how women with a history of IPV wish health care providers to inquire about and respond to disclosures of abuse.19 Survivors commonly wish for provider responses that are nonjudgmental, nondirective, and individually tailored, with an appreciation of the complexity of partner violence.19 However, most of that literature focuses on the provider’s response to the abuse, not the provider’s management of the many health issues associated with a history of abuse. The objectives of this analysis are to explore qualitatively what depressed IPV survivors believe about the relationship between abuse, mental health, and physical symptoms and to use this information to develop patient-informed recommendations for primary care providers about addressing depression or physical symptoms in women with a history of IPV.

METHODS

We conducted 5 focus groups with women with current depressive symptoms and a lifetime history of IPV. All protocols and materials were approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment and Screening

This focus group study was conducted in conjunction with a cross-sectional survey that has been described elsewhere.18 Adult, English-speaking women presenting to an academic General Internal Medicine clinic on recruitment days were offered a flyer saying that “we are working to develop a new model of health care to better address the physical and mental symptoms experienced by our women patients.” A research assistant then approached female patients, obtained informed consent to participate in a screening survey, and asked them if they would be willing to be contacted to potentially participate in future phases of the study. All women were encouraged to take the brief survey, regardless of their willingness to be contacted for future studies. To avoid potential selection bias, we did not present the study as focusing on violence or abuse.

The survey consisted of a number of validated instruments, including the depression scale of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-20),20–22 the Patient Health Questionnaire-1523,24 to measure physical symptoms, and a modified version of the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS)25 to measure IPV. We modified the AAS to ask about lifetime events as opposed to the current year and added items about the number of times each form of violence occurred. The survey additionally included items on physical and sexual child abuse, history of schizophrenia or other psychosis, whether or not the participant was seeing a mental health provider, whether or not she was taking an antidepressant, age, race, and ethnicity.18

We were most interested in obtaining qualitative information from women who had experienced significant enough violence that it would be likely to influence their health or health care. As such, we excluded women who had only experienced rare, nonrepetitive, low-level violence. We defined IPV as having experienced 1 or more severe physical assaults from an intimate partner (such as being punched, kicked, beat up, injured, or threatened with a weapon) or having experienced 5 or more slaps or pushes that did not result in lasting pain. Women who met our definition of a lifetime history of physical IPV, who agreed to be further contacted, and whose survey responses indicated they had at least mild current depressive symptoms (as defined by a HSCL-20 score ≥1.0), and no history of psychosis, were eligible to participate in the focus group study. A research assistant called eligible women; further explained the purpose, risks, and benefits of the qualitative portion of the study; and scheduled them for focus groups. A second formal informed consent discussion occurred in person at the time of the focus group.

We used an iterative approach to recruitment. The research assistant would recruit women from the clinic to the survey portion of the study and enter results into a database. When she had at least 10 women who met inclusion criteria for the focus group study, she would stop survey recruitment and would arrange a focus group. Once the focus group was completed, she would resume recruitment for the survey study. This cycle continued until the principal investigator felt theme saturation was met for the focus groups study.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

The principal investigator facilitated the focus groups, with a research assistant present to take notes and offer assistance as needed. One focus group was transcribed in real-time by a court reporter and 4 were transcribed from audio tapes. The facilitator used an interview guide to structure the discussions. The first part of the focus group asked general questions (see Online Appendix) that would allow us to develop theoretical frameworks from our primary data. Questions addressed women’s views on health in general and mental health in particular; their beliefs about the relationship between IPV, physical health, and mental health; their experiences with health care; their recommendations to providers; and their responses to a variety of possible components of a chronic care program for treating depression in IPV survivors. A secondary goal was to gather data that would better inform the development of a multifaceted depression care intervention within our clinic. Thus, the last part of the group consisted of more researcher-driven questions related to the potential intervention components. Focus groups lasted 2 to 2 1/2 hours, with approximately 2/3 of the time spent discussing questions related to our primary goal. This paper does not address results specifically related to the development of the multifaceted intervention.

The same interview guide was used for all 5 focus groups. However, at times, in an effort to clarify participants’ comments, the interviewer made references to emerging themes that she had heard in prior focus groups and asked for feedback regarding how this material might relate to what they were trying to express. This technique allows participants to explain and elaborate on emerging themes or express differing opinions.26 Additional steps were taken at the end of each focus group to improve validity of results.27 First, the principal investigator offered a summary of what she had heard the women say in response to each of the questions on the interview guide and asked participants if she had correctly interpreted their responses. Second, she asked each participant to note the one most important message she should take back to health care providers.

We analyzed our data using the technique of thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a commonly used (though infrequently named) flexible approach to analyzing qualitative data.28 It entails making a number of decisions. We chose an inductive approach (consistent with grounded theory) wherein themes are grounded in the data, as opposed to a theoretical approach where themes are driven by the literature or the researcher’s theories. We analyzed data at a semantic or explicit level, as opposed to a latent level (i.e., we focused on what participants said, not the underlying ideas that are theorized to shape the semantic content of the data), and we used an essentialist/realist as opposed to a constructionist paradigm (i.e., we theorized motivations, experience, and meaning from what participants said rather than theorize the sociocultural contexts and structural conditions that enabled the individual accounts).

Two investigators (CN and JG) read each of the transcripts in their entirety and discussed general impressions and insights they had gained from the focus groups. CN then developed a set of preliminary codes and reviewed the coding scheme with JG. CN coded the transcripts and met with JG to review the coding and to generate themes and subthemes from the preliminary codes. Some original codes formed main themes, others formed subthemes, and others were discarded. Doubts or disagreements were resolved by rereading the original transcripts until both investigators agreed. A third investigator (HG) then re-reviewed transcripts to apply the final coding scheme based on the larger themes. All 3 investigators met to review and refine the final themes to ensure internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity. Again, they resolved disagreement by consensus.

RESULTS

A total of 646 eligible women presented to the clinic on recruitment days, of whom 380 (59%) completed the survey. An additional 307 women presenting to the clinic did not meet eligibility criteria as a result of being under the age of 18 years (N = 1), not speaking English (N = 91), being mentally impaired (N = 21), being physically impaired (N = 37), being clinic employees (N = 8), or having previously been offered participation (N = 149). Fifty women would have been eligible to participate in the focus groups based on a history of IPV and current depressive symptoms. Forty-two (84%) gave permission to be contacted for future studies. Of these 42 potential participants, 10 could not be contacted, 2 refused participation, and 7 agreed to participate but either had scheduling conflicts or did not show up to their scheduled group. We conducted 5 focus groups with 23 women. We intended to have 5–8 participants in each focus group, but because of no-shows, focus groups had 2–7 participants. At the end of the fifth focus group, we felt that theme saturation had been met, so we stopped recruitment to the survey study.

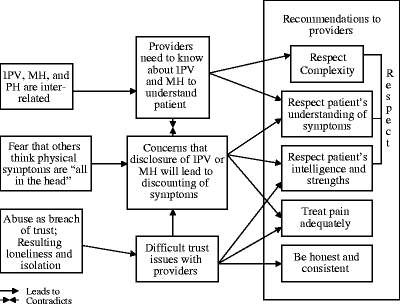

One woman was Native American; the remaining participants were white, non-Hispanic. All but one were no longer involved with their abusive partners. Compared to eligible nonparticipants, focus-group participants were older and more likely to be receiving care from a mental health provider. There were no other statistically significant differences amongst measured characteristics (Table 1). Figure 1 summarizes the common themes identified from the focus group discussions and the relationships between themes.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Total screened N = 380 | Eligible for focus groups N = 50 | Participated in focus groups N = 23 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 51.0 | 47.5 | 51.9* |

| White, non-Hispanic, % | 81% | 83% | 94% |

| Lifetime IPV history, % | 30% | 100% | 100% |

| Physical child abuse, % | 23% | 42% | 52% |

| Sexual child abuse, % | 29% | 60% | 57% |

| Physical symptoms (mean PHQ-15 score) | 10.6 | 15.9 | 16.6 |

| Depressive symptoms (mean HSCL-20 score) | 0.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| At least mild depressive symptoms, % (HCL-20 >= 1.0) | 38% | 100% | 100% |

| Taking antidepressants, % | 44% | 66% | 71% |

| Current care from mental health provider, % | 18% | 22% | 40%* |

IPV intimate partner violence, HSCL-20 depressive symptom scale of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist, PHQ-15 physical symptom scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire-15

PHQ-15 has a potential range of 0–30, with higher scores indicating greater symptoms. HSCL-20 has a potential range of 0–2.0, with higher scores indicating greater symptoms.

*p < 0.05 in comparison to women who were eligible to participate in the focus groups but did not do so

Figure 1.

Common themes. IPV: intimate partner violence. MH: mental health. PH: physical health.

Abuse, Physical Health, and Mental Health are Interrelated

Although women were selected for participation based on their depressive symptoms, they spontaneously focused much of the initial discussion on physical symptoms. Most felt strongly that physical symptoms, mental health, and IPV are all closely interrelated and cannot be considered separately. They explained that “One compounds the other. Always.” Along those lines, women often commented on how their past experiences of abuse affected the present, even decades after the end of the abuse. As one woman said, “It’s just affected everything. And I’m sure if I had a more normal life, I wouldn’t be so sick today.” Or, as another woman explained,

“He would beat me where nobody could see the marks—my back, the side of my head, back of my head, whatever. And I think that’s got a lot to do with my pain problems now. Now that I’m older, it’s caught up with me.”

Need for Providers to Know About IPV and Mental Health

Because they felt that their abuse experiences and their physical and mental health were all interrelated, many women believed that health care providers need to know about past abuse experiences to address their health and health care needs. As one woman said,

“Just add it to the big picture. It’s like getting a 13” T.V. Now you see it. You get a 32” T.V.—there’s more of the picture there. And it clears. You know a little more about what is going on. Maybe that’s why she’s got irritable bowel syndrome. Or whatever. It just seems like a better picture to me. I would want to know. The more you know about it, the better.”

In fact, they often expressed frustration about providers not trying to find out about the complex issues affecting their health, even if they did not spontaneously disclose issues of abuse to providers. For example, one woman described her anger at the emergency department physician she saw after being assaulted by her partner:

“Those Doctors! Now, I had a broken eardrum, and he [her abusive partner] wouldn’t take me unless I promised to say it happened in the car. Now, that doctor knew that was a lie! He didn’t say anything about it. He just let it go. You know, like when you need to wear the Jackie Onasis glasses. They never ask you. They need to look at why.”

Fears that Disclosure will Lead to Discounting of Physical Symptoms

At the same time that they recognized the interrelatedness of their abuse and their physical and mental health, many women voiced strong concerns that if providers knew about their abuse and mental health histories, the providers would consider physical symptoms as existing “all in their head.” This concern often outweighed the idea that providers need to know about abuse, as participants feared that disclosing either abuse or mental health issues would allow providers to discount their symptoms or undertreat their pain. As one woman explained,

“And the last thing I learned is if they think you’ve got any kind of emotional problems, they have this thing about giving you any kind of medication. They’ll say, ‘is this for real, your pain?’ So I’m always shaky. I don’t want where if I am in agony: ‘Oh, it’s probably in your mind. Let’s not give her the medicine she needs.’ And stuff like that. I’m very suspicious and very careful of what I tell my doctor because of that. Because you always end up feeling like you’re some hypochondriac.”

Another described:

“I get scared to tell them because I think they are going to think I am in emotional pain when its really physical pain and they are going to correlate the two and try to treat the emotional pain when I’m having actual physical pain.”

Instead of improving depression care, attempts from providers to attribute pain to depression often led to worsened physician–patient relationships or to avoidance of care. As one woman said, “It’s better to be sick than to be belittled.” Or as another explained:

“There are times that I know depression has nothing to do with it. I went to a doctor – a resident – and I was having this pain and I was having night terrors and she said to me, she said ‘We have to get you involved in some kind of a group. You have to get out of the house more. You have to have a hobby.’ I have so many hobbies you wouldn’t believe it…So when she says this is all from depression I changed doctors.”

Trust

Although we did not specifically ask about trust issues, trust was another prominent theme throughout the focus groups. Women often described the abuse as a breach of trust. Unfortunately, for many, this breach of trust was repeated by many people throughout their lives, including parents and other partners. They often felt the resultant trust problems affected all aspects of their lives, including their relationships with other partners, family, children, and friends. The result was often an extreme sense of loneliness and isolation. These issues became particularly important in their relationships with health care providers. Some felt like providers had repeated the patterns they had experienced from others:

“And that’s what scares me. Like I said, doctors have betrayed me. And it isn’t just men doctors—women doctors.”

Many talked about how difficult it was to trust providers:

“You have to trust these people and—but you don’t trust them, and you’re always afraid that something bad or something worse is going to happen. And you know. So it was a very, very long time before I was able to develop a relationship with any doctor.”

Women were often very introspective about their role in learning to trust providers:

“Am I willing to start learning how to re-trust again?…It doesn’t just affect [the batterer]. It affects all areas. So, do I even trust my health providers even? I mean the trust issues go huge, and deep and long.”

They were especially appreciative of providers who gained their trust. They felt providers did so by being honest, straightforward, and consistent.

“I think it goes back to the whole trust issue because I think the doctor that I had—she was really straightforward with me and she didn’t screw around and I really appreciated that. I don’t know about you guys, but I test people. You know, and so I’ll throw something completely out of left field at them just to see what they’re going to do and she passed the test. And so, she was really consistent so it was a lot easier for me to trust her.”

In fact, providers who were able to display honesty and consistency were then able to better address the connection between physical and mental health. For example, this patient had been very upset when her provider first attributed her physical complaints to mental health issues.

“Well, I hung in there with him and I realized he was so right…He really helped me by just being honest.”

Desire for Respect

Women had considerable advice for providers, but much of it could be distilled down to the concept of respect. Some talked about the need for providers to respect their intelligence, their experiences, or their symptoms:

“I can understand what you tell me. Talk to me intelligently and don’t treat me like a mushroom and answer my questions.”

“Realize the patient knows her own body and take that more seriously. Check it out.”

Others wanted providers to respect the complexity of their health.

“I think that is what doctors need to do is take into account that we have reasons why we are the way we are and don’t just give us a pill to make it all better because that’s not always what it takes.”

“Be aware of the individual. We are a sum total of our experiences.”

As one woman explained:

“Every person is different and—sometime maybe like a gemstone that hasn’t been completely finished yet. We’ve only got so many facets. Some of us have a lot of facets already. Whatever. Some of us have a few sides, some of us have many sides, but we are all complete persons individually…And whether or not they can treat all those things, don’t put part of it down because—don’t treat them like, well, like it’s not important.”

DISCUSSION

IPV survivors were acutely aware of the interconnections between their IPV, depression, and physical symptoms. Women felt providers need to know about each of these aspects to understand them and were frustrated with providers who did not inquire about IPV. However, they were hesitant to discuss mental health or IPV for fear of being thought hypochondriacs or having their pain undertreated. Issues of trust permeated survivors’ lives, leading to social isolation and distrust of providers. They felt providers who could earn their trust by displaying honesty, consistency, and respect were more effective in dealing with the complexity of their health needs.

Our findings are consistent with several key themes previously noted in the literature. Feder et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 29 qualitative studies, synthesizing data about how women with a history of IPV want health care providers to elicit and respond to disclosures of abuse.19 As in our study, many of the key themes revolved around the importance of trust; a nonjudgmental, individual approach; and an appreciation for the complexity of partner violence. Our study adds to the literature by focusing not on how providers should address IPV itself, but on how IPV survivors want providers to address related, chronic medical issues such as depression or chronic pain. Regardless of the ultimate outcome of the debate regarding the effectiveness of IPV screening in reducing injuries related to IPV,29–34 providers will continue to be faced with the daily challenge of treating issues such as depression and chronic pain in women who have a history of IPV.

Our study had several important limitations. We only recruited women from one academic Internal Medicine clinic that serves predominantly low-income, medically complex, white patients. Participants were not a representative sample of all eligible women, being older and more likely to have a mental health provider than nonrespondents. As with most qualitative studies, our objective was to gain deeper understanding from key informants. Thus, there may be limited generalizability, especially to healthier populations; women uninterested in participating in research; or women with diverse geographic, racial, or ethnic backgrounds.

Despite these limitations, our study has several important implications. First, providers should inquire about IPV in women with depression or multiple physical complaints, not only because of the high prevalence of IPV in this scenario but also because respectful inquiry about IPV may help build trust and strengthen the therapeutic relationship. However, one must consider how best to assess IPV in these settings. If a woman presents with pain or other physical symptoms, it is possible that assessments for IPV or mental illness may be interpreted as the provider’s attempts to discount her symptoms or prove that she is imagining them. We would recommend assessing for IPV and mental health issues only after taking a full patient-centered history about the physical symptoms. Providers should make every effort to demonstrate their respect for patients’ intelligence, experiences, and complexity. We would then suggest prefacing questions about IPV or mental illness with a short statement about their interrelationship with physical symptoms and that the patients’ physical symptoms are not imagined or caused by emotional issues. It may be helpful to state specifically that one is interested in these issues because they “compound each other” or may make pain “more severe” or “harder to treat,” thus implying that disclosure will allow the provider to take the patients’ physical concerns more seriously, not less seriously.

Furthermore, information about IPV should alert a provider to be particularly careful in regards to issues of trust and control within the patient–provider relationship. Given the association between IPV, pain, and unexplained physical symptoms,2 providers often find themselves negotiating the use of chronic opioids with IPV survivors. Such interactions may heighten both the provider’s need for control and the patient’s fears about being controlled. Open discussions about a patient’s IPV history and, in particular, the patient’s concerns about control, trust, and blame may allow the provider to ally with the patient. After learning of past abuse, expressing sympathy for what a patient has experienced, and showing respect for the patients’ survival skills, a provider may, for example, comment that other patients in this type of situation have felt that their partners were very controlling. If such a statement is met with strong agreement, the provider can then steer the discussion to ways that the abuse history may be compounding their pain or how the pain is controlling the patient’s life. The provider can then talk about ways they can work together to help the patient get more control of her pain and mental health. Providers should be aware of the need to share control, wherever possible, with IPV survivors. Although such principles may be a part of good patient care under any circumstances, they may potentially have an even greater impact with IPV survivors whose abuse histories may make them particularly sensitive to issues of control, trust, and respect. See Table 2 for examples of communication techniques that providers may use with IPV survivors to address the themes identified in this study. Future research is needed to test whether or not adhering to such recommendations significantly improves the therapeutic relationship with IPV survivors and, ultimately, health outcomes.

Table 2.

Clinical Implications

| Focus-group finding | Examples of communication techniques to address finding |

|---|---|

| Conflict between need for provider to know about IPV/MH to fully understand patient and concern that disclosure will lead to discounting of symptoms | If patient is presenting with physical symptoms, first take appropriate patient-centered symptom history and assure patient that you empathize with impact on life. Then preface questions about IPV or MH with statement such as: |

| “I don’t doubt that your pain is real. But, as you probably know, life experiences and emotions can make pain even more severe and harder to treat. I want to ask you some questions so I can better understand you as a whole person and possibly help you get better control of your pain.” | |

| Need for providers to demonstrate respect for patients’ understanding of symptoms | Provider can make statement such as: |

| “It sounds like you have been dealing with these symptoms for a long time and that you have really thought a lot about what may be causing them.” | |

| “I can see you know your own body really well.” | |

| Need for providers to respect patients’ intelligence and strengths | After learning about a history of abuse, provider can make statements such as: |

| “I am really impressed with the strength it takes to survive a situation like that. I am sorry you had to go through that. But it gives me hope that if you can survive that, you also can find a way to manage your symptoms.” | |

| Need for providers to treat pain adequately | Do not use history of IPV or depression as reason not to treat pain or to withhold opioids. However, opioids may or may not be appropriate or effective in any given situation, and use of opioids may require greater need for control from provider. Use information about IPV history (especially history of partner’s controlling behavior) to ally with patient. Example: |

| “It sounds like he really tried to control your life. And even now, it may be that some of what you went through is still affecting your ability to get control over your pain. Let’s work together to find a way to help you get more control back into your life.” | |

| Offer patient as much control as possible, even when you need to retain some control of prescribing. Example: | |

| “It doesn’t look like the benefit you are getting from your Vicodin is enough to outweigh its risks. I really think we should start slowly tapering down on how many Vicodin tablets you are using. Do you think it would be easier to go down on how many you take at once or on how many times a day you take them?” |

IPV intimate partner violence, MH mental health

Electronic supplementary materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplemenatry materials.

(DOC 35.5 KB)

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Depression in Primary Care Program (#049268). Dr. Nicolaidis’ time is supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH073008-03). We would like to thank Rebecca Ross, MHNP, Kaycee Mutschler, Jeannette Bardsley, and Vassiliki Touhiliotis for their efforts in recruiting and screening patients, cofacilitating focus groups, and transcribing data.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0606-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Nelson HD, et al. Screening women and elderly adults for family and intimate partner violence: a review of the evidence for the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force.. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(5):387–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. J Fam Violence. 1999;14(2):99–132. [DOI]

- 4.Weinbaum Z, et al. Female victims of intimate partner physical domestic violence (IPP-DV), California 1998. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(4):313–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Lown EA, Vega WA. Intimate partner violence and health: self-assessed health, chronic health, and somatic symptoms among Mexican American women. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(3):352–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Campbell J, et al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1157–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Tollestrup K, et al. Health indicators and intimate partner violence among women who are members of a managed care organization. Prev Med. 1999;29(5):431–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Coker AL, et al. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):451–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.McCauley J, et al. Relation of low-severity violence to women’s health. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(10):687–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Nicolaidis C, et al. Violence, mental health, and physical symptoms in an academic internal medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;198(8):19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Follingstad DR, et al. Factors moderating physical and psychological symptoms of battered women. J Fam Violence. 1991;6(1):81–95. [DOI]

- 12.Eby K, Campbell JC, Sullivan C, Davidson W. Health effects of experiences of sexual violence for women with abusive partners. Womens Health Int. 1995;16:563–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.McCauley J, et al. The “battering syndrome”: prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(10):737–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Wisner CL, et al. Intimate partner violence against women: do victims cost health plans more? J Fam Pract. 1999;48(6):439–43. [PubMed]

- 15.Ulrich YC, et al. Medical care utilization patterns in women with diagnosed domestic violence. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sansone RA, Wiederman MW, Sansone LA. Health care utilization and history of trauma among women in a primary care setting. Violence Vict. 1997;12(2):165–72. [PubMed]

- 17.Scholle SH, Rost KM, Golding JM. Physical abuse among depressed women. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(9):607–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Nicolaidis C, et al. Differences in physical and mental health symptoms and mental health utilization associated with intimate partner violence vs. child abuse. Psychosomatics. 2008 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Feder GS, et al. Women exposed to intimate partner violence: expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: a meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):22–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Derogatis LR, et al. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lipman RS, Covi L, Shapiro AK. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL)—factors derived from the HSCL-90. J Affect Disord. 1979;1(1):9–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Derogatis L. SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist -90-R Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, 3rd edn. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1994:123.

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):258–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kroenke K, et al. A symptom checklist to screen for somatoform disorders in primary care. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(3):263–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Soeken S, et al. The abuse assessment screen. In: Campbell J, ed. Empowering Survivors of Abuse; Health Care for Battered Women and Children. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1998:195–203.

- 26.Krueger R. Moderating focus groups. In: Morgan D, Krueger R, eds. The focus group kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998:115.

- 27.Krueger R. Developing questions for focus groups. In: Morgan D, Krueger R, eds. The focus group kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998:107.

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [DOI]

- 29.Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. Interventions for violence against women: scientific review. JAMA. 2003;289(5):589–600. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Ramsay J, et al. Should health professionals screen women for domestic volence? Systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325:314–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.U S Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for family and intimate partner violence: recommendation statement.[see comment]. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(5):382–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Soler E, Campbell J. Screening for family and intimate partner violence.[comment]. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):82. discussion 82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Nelson JC, Johnston C. Screening for family and intimate partner violence.[comment]. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):81. discussion 82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Nicolaidis CA, American Medical Women’s, and M. Physicians Against Violence Interest Group of the Society of General Internal. Screening for family and intimate partner violence.[comment]. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):81–2. discussion 82. 15238384

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplemenatry materials.

(DOC 35.5 KB)