Abstract

Background

Research indicates that successful migraine assessment and treatment depends on information obtained during patient and healthcare professional (HCP) discussions. However, no studies outline how migraine is actually discussed during clinical encounters.

Objective

Record naturally occurring HCP–migraineur interactions, analyzing frequency and impairment assessment, and preventive treatment discussions.

Design

HCPs seeing high volumes of migraineurs were recruited for a communication study. Patients likely to discuss migraine were recruited immediately before their normally scheduled appointment and, once consented, were audio- and video-recorded without a researcher present. Separate post-visit interviews were conducted with patients and HCPs. All interactions were transcribed.

Participants

Sixty patients (83% female; mean age 41.7) were analyzed. Patients were diagnosed with migraine 14 years and experienced 5 per month, on average.

Approach

Transcripts were analyzed using sociolinguistic techniques such as number and type of questions asked and post-visit alignment on migraine frequency and impairment. American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study guidelines were utilized.

Results

Ninety-one percent of HCP-initiated, migraine-specific questions were closed-ended/short answer; assessments focused on frequency and did not focus on attention on impairment. Open-ended questions in patient post-visit interviews yielded robust impairment-related information. Post-visit, 55% of HCP–patient pairs were misaligned regarding frequency; 51% on impairment. Of the 20 (33%) patients who were preventive medication candidates, 80% did not receive it and 50% of their visits lacked discussion of prevention.

Conclusions

Sociolinguistic analysis revealed that HCPs often used narrowly focused, closed-ended questions and were often unaware of how migraine affected patients’ lives as a result. It is recommended that HCPs assess impairment using open-ended questions in combination with the ask-tell-ask technique.

Key words: migraine, communication, prevention, sociolinguistics

INTRODUCTION

Migraine headache is a chronic, often disabling, condition which affects about 21 million females and 7 million males over the age of 12 in the USA1. Although pharmacologic and behavioral interventions can substantially decrease migraine headache frequency, duration, and associated impairment, epidemiological studies have demonstrated that many migraineurs remain undiagnosed, while those with an official diagnosis may not receive appropriate treatment. The majority of migraineurs are less than completely satisfied with the care they receive2 and many of those who have received some medical attention fail to continue treatment3. Identifying barriers to care is an important first step towards improving it. Better understanding of healthcare professional (HCP)–patient communication represents an important potential avenue to achieve optimal care of patients with migraine as well as other disorders4,5.

In many respects, migraine is an ideal condition for studying clinician–patient communication, since identification and treatment largely depend on information obtained in conversation between patient and HCP. The diagnosis of the migraine patient is based solely on the medical history; neuroimaging and laboratory studies serve to exclude other causes but do not provide positive evidence in support of a migraine diagnosis6. Assessment of headache frequency, severity, and associated impairment are major determinants of optimal treatment and can be assessed only through dialogue7–11. The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study (AMPPS) demonstrated that 39% of patients suffering from migraine in the community are prevention candidates based on an algorithm using two headache history–derived parameters: headache days per month and headache-related impairment. This study also demonstrated that only 13% of candidates for prevention had such medication prescribed12.

Communication is a key determinant of treatment outcomes in a range of therapeutic areas13, and many features of effective HCP–patient communication have been identified and studied. Although HCP–patient communication has been identified as an essential aspect of migraine care14–18 and self-report instruments such as MIDAS and HIT-6 have been developed to improve communication19–24, empirical studies of in-office communication between migraineurs and HCPs have not been conducted. Prior studies show that despite the fact that clinicians ask about headache-related impairment infrequently25, this information influences HCPs’ assessment of headache severity and alters prescribing behavior.

To assess current in-office communication patterns and to identify opportunities for improved communication in migraine, an in-office linguistic study was conducted using accepted sociolinguistic methods26–28. The goal of this study was to record and analyze HCP–patient interactions during office visits and evaluate the relationship between communication characteristics and visit outcomes, including choice of treatment and patient–HCP concurrence on treatment plan. The study was designed to provide an evidence base for developing techniques to improve communication and enhance outcomes of care for migraine, and by extension, for other conditions with similar clinical communication challenges. The study employed a unique strategy based on video-recording of actual in-office encounters, followed by separate semi-structured post-visit interviews of both patient and HCP(s), which were also video-recorded.

METHODS

The methods outlined below have been published elsewhere29–32. Prior to study initiation, a steering committee consisting of migraine experts with an interest in communication was convened to discuss study objectives, methodology, and linguistic analyses, with the goal of studying language surrounding migraine in real-world office visits.

The study received Institutional Review Board approval in January 2004 and fieldwork was conducted from January through March 2004. Invitation letters were mailed to community-based primary care physicians (PCPs; n = 1,008) and neurologists (n = 765). Of the 148 practices that responded (86 neurologists; 62 PCPs), 22 met screening criteria (Text Box 1),

Text Box 1: Physician Screening Criteria

| • Medical specialty: internal medicine, family practice, or neurology |

| • Years in practice > 2 and < 30 |

| • Age: ≤ 60 years old |

| • ≥ 80% of time spent in direct patient care |

| • In private (vs. hospital-based or academic) practice |

| • ≥ 70% of patient base age 18 years or older |

| • ≥ 50 (neurologist) or ≥ 100 (PCP) patients treated in office per week |

| • ≥ 20 patients per week treated in-office for migraine |

were available during the data collection phase and agreed to participate. Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) in participating offices were invited to participate if they interacted with migraine patients through assessment, counseling, and/or prescribing medication separately from the physician. These interactions were included because prior research has suggested that NPs and PAs often play a major role in migraine care33. A total of 14 PCPs, 8 neurologists, and 6 NP/PAs participated; physician demographics can be found in Text Box 2.

Text Box 2: Physician Demographics

| • In practice an average of 15.5 years |

| • One PCP and three neurologists defined themselves as “headache specialists,” while the remainder of participating physicians were general practitioners |

| • Practices in California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas |

| • On average, write 11.4 beta blocker, 28.1 antidepressant and 26.6 antiepileptic prescriptions per week specifically for the treatment of migraine |

| • Received an honorarium of $1,000–$1,500 |

Field researchers spent 1–2 days in offices to collect data. Healthcare professionals or their office staff reviewed patient charts to determine which patients with regularly scheduled visits would be likely to discuss migraine during the visit. These patients were approached to participate in the study upon arrival. To increase the likelihood of discussions about preventive treatments, patients with more severe or more frequent migraines were recruited over those with less severe or less frequent migraines.

To minimize any minimal change in behavior that video- and audio-taping might produce34 participants were informed that the study was about communication in migraine but were not informed about the specific focus on assessment of frequency and impairment, its relationship to discussions of migraine prevention, or the study sponsor.

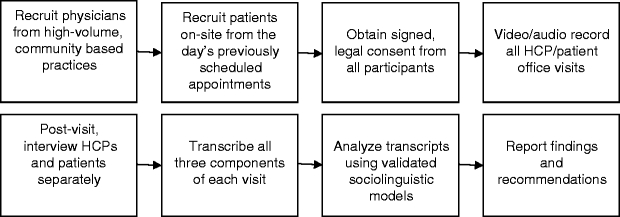

After obtaining written consent from all participants, the office visit was audio- and video-recorded without the researcher present in the exam room (see Fig. 1 for complete study methodology). A total of 78 patients were recorded and the 60 HCP–patient interactions containing a substantial discussion of migraine formed the study sample. Forty patients saw a PCP and 20 saw a neurologist (see Text Box 3 for patient demographics).

Text Box 3: Patient Demographics

| • 10 males, 50 females |

| • Average age of 41.7 |

| • 95% have insurance coverage |

| • 73% have prescription drug coverage |

| • Average of 3.4 comorbid conditions, most frequently: -Anxiety (47%), allergies (43%) and depression (43%) |

| • Patients have been diagnosed an average of 14 years |

| • Patients average 5 migraine episodes per month |

| • Patients average 20 “days” of headache over 3 months |

| • Patients experience 5.7 symptoms with severe headaches on average, most frequently: -Vomiting (87%), unilateral pain (82%), blurred vision (78%), and sensitivity to light (77%) |

| • Received an honorarium of $75 |

Figure 1.

Study design.

Patients participated in individual semi-structured video- and audio-recorded post-visit interviews with the researcher immediately following office visits. To keep disruption to practice patterns at a minimum, HCPs participated in recorded post-visit interviews at the end of office hours. They answered general questions about migraine treatment and, utilizing patient charts as a reference, responded to specific questions about each patient who participated that day. These interviews, which did not include a review of the recorded office visit, addressed the participants’ perceptions of what was discussed during the visit and identified potential sources of HCP–patient miscommunication.

Recordings of the 60 doctor–HCP interactions and post-visit patient and HCP interviews were transcribed and analyzed using validated sociolinguistic techniques as described by Gumperz26,27 and elaborated upon by Hamilton28. Sociolinguistic analysis is based upon identifying and classifying utterances using a variety of parameters. The unit of analysis can range from the frequency of specific individual words to paired statements to the overall architecture of a conversation. The sample size obtained in this study is comparable to other, widely accepted qualitative, social science research35–37. In this study, transcripts were the principal source for analyses, as they allowed for a careful word-by-word examination of each conversation. Specific linguistic analyses included quantification of topics discussed and time spent on each; questions asked and answered; word-level analyses of key lexical items; and “open door/close door” of topics put forth or blocked in conversation. Descriptive statistics, principally frequencies and proportions, were applied to communication parameters of interest.

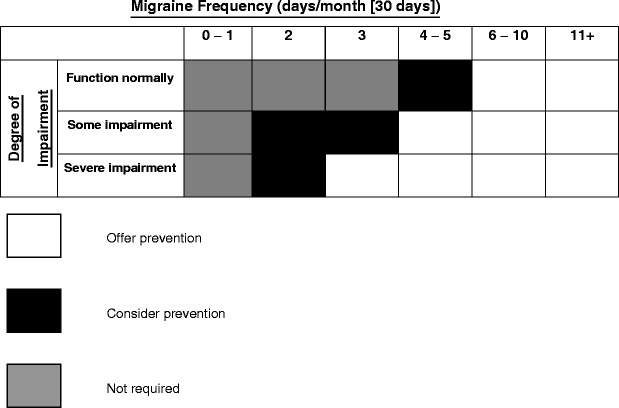

The relationships between preventive treatment initiated and/or discussed in visits and HCP–patient alignment on impairment and severity were examined in detail. Prevention candidacy was determined by applying the AMPPS guidelines38. These guidelines rely upon two parameters:

headache frequency, expressed as headache days per month (30 days), based on an average of headache days over the last 3 months; and

headache-related impairment, rated using the three-category classification of “none”, “some”, or “severe or requiring bed rest”.

Patients were classified into one of three categories (prevention not indicated; consider prevention; and offer prevention) using these parameters (see Table 1 for AMPPS criteria).

Table 1.

American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study (AMPPS) criteria

RESULTS

The average visit was 12 min long (n = 60; standard deviation 5.6 min; median 11.2 min). An average of 13 headache-related questions was asked by HCPs in each visit. As seen in other studies of HCP–patient communication39 and in the following examples, the vast majority (91%) of questions during the migraine evaluation process were closed-ended (yes/no, short answer).

Example 1: Yes/No question; 31-year-old female and PCP

DOCTOR: Still at least a couple of times a month?

PATIENT: Yeah.

DOCTOR: Okay. Any more frequent than that?

PATIENT: No.

Example 2: Short answer question; 48-year-old female and PCP

DOCTOR: And did you have nausea and/or vomiting whenever you had migraines?

PATIENT: Sometimes I’ll have nausea. I’ve had vomiting maybe every 5 or 6 times, not always.

These HCP-initiated questions focused most often on attack frequency, which was asked about in 63% of visits (Table 2). Migraine prevention candidacy was most commonly assessed on the basis of attack frequency alone. By contrast, only 10% of visits addressed the issue of impairment—and those questions were also almost always closed-ended. For example,

Example 3: Question addressing impairment; 40-year-old female and neurologist

DOCTOR: Can you work through it, or you really have to stop?

PATIENT: I have to stop. Yeah.

Table 2.

American Migraine Communication Study (AMCS) Total Questions Asked by Topic

| Question topic | Example | Number of visits in which asked | Percentage of visits in which asked |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headache frequency | About how often do you get the headaches? | 38 | 63 |

| Opening/background | So, how are the headaches? | 38 | 63 |

| Triggers | Do you know of anything that maybe causes your migraines? | 32 | 53 |

| Symptoms and associated features | Any nausea, vomiting? | 29 | 48 |

| Headache severity | Were they disabling or were you still able to function? | 27 | 45 |

| Location of pain | Do you normally have them localized to one side or the other? | 25 | 42 |

| Nature of pain | A pounding sensation or just pain? | 24 | 40 |

| Duration of migraine | How long do they last when you get these headaches? | 22 | 37 |

| Aura | Do you always have visual stuff before the headache? | 21 | 35 |

| History of migraine | You used to get them as a kid? | 19 | 32 |

| Family history | Do you have any history of people in your family having headaches like that? | 13 | 22 |

| Sinus headaches | Have you been getting a stuffy nose or a runny nose with it? | 7 | 12 |

| Migraine-related impairment | Do you ever miss work? | 6 | 10 |

| Total | 57 | 95 |

In contrast, when researchers used open-ended questions during the post-visit interviews, patients often revealed information focused on impairment that was not disclosed during the visit25,40–44. These detailed, emotional responses provided a more complete and compelling picture of how disabling migraines really are for the patient. In the clinical context, such information would allow for a more complete assessment of the patient’s condition. Without the benefit of this additional information and despite having patient chart information as reference, HCPs often underestimated the impairment of migraine on the patient25, as in the following examples:

Example 4a: Post-visit interview with 23-year-old female patient

INT: In your own words how do your migraines affect your daily life?

PATIENT: [laughs] A lot. I can’t do anything and I miss work or I’d miss school and I’m a vegetable. I can’t do anything. I have to stay in bed and then I don’t want anyone to bother me.

Example 4b: Post-visit interview with PCP regarding 23-year-old female

INT: Okay. On a scale of 1 to 10 how would you rate this patient’s migraines where 1 is least severe and 10 is most severe?

DOCTOR: It sounded like it didn’t really affect her. I guess she didn’t go into a dark room and that, so it sounded like maybe like a 3 or 4.

Comparison of HCP and patient assessment of headache frequency (as determined by both parties in post-visit interviews) revealed significant disagreement in 55% of HCP–patient pairs, as illustrated in the following example:

Example 5a: Post-visit interview with 52-year-old female patient

INT: How many times would you say in the last year have you had a migraines? Not even necessarily have you come in here for it, just—

PATIENT: I probably have six to eight a month.

INT: At least eight a month?

PATIENT: At least. At least.

Example 5b: Post-visit interview with PCP (regarding 52-year-old female patient)

INT: Okay, how many migraines on average does she have a month?

DOCTOR: She has four a month.

HCPs also misjudged patients’ level of impairment in 51% of cases. Taking into consideration information about frequency and impairment provided by patients in post-visit interviews makes it clear that many patients not on prevention when their visit was recorded were, in fact, prevention candidates. Specifically, 35 of the 60 patients were not on preventive therapy at the initiation of their visits. Of these 35 patients, 20 (57%) met AMPPS criteria for preventive treatment (Table 3). In half of these visits (10 of 20), migraine preventive therapy was not discussed. Prevention was discussed but not prescribed in 6 of 20 (30%) visits. However, these 6 discussions were minimal and did not include an offer of a new prescription for migraine preventive therapy. In most cases, HCPs confirmed past treatment regimens (“what preventative things have you tried?”) or briefly mentioned preventive therapy without describing it in detail. Only 4 (20%) of the 20 candidates for migraine prevention actually received it.

Table 3.

AMCS Patients Not on Prevention Who Should be Offered per AMPPS Criteria.

| Outcome | Number of visits | Percentage of visits |

|---|---|---|

| No discussion, no Rx | 10 | 50 |

| Discussion, but no Rx | 6 | 30 |

| Discussion and new Rx | 4 | 20 |

| Total | 20 | 100 |

n = 20 patients who were not on prevention at the outset of the visit who would be deemed “offer preventive treatment” according to AMPPS criteria

Since the discrepancy between patients’ candidacy for preventive therapy and the prescriptions they actually received was not known until after the research had been conducted, post-visit interviews did not include questions addressing the issue of why prevention was or was not prescribed.

DISCUSSION

This study, the first to date using techniques of in-office recording and sociolinguistic analysis to study HCP–patient communication about migraine, reveals that HCPs primarily evaluate migraine and migraine prevention candidacy using closed-ended questions focusing on frequency. Relying almost exclusively on closed-ended questions limits patients’ answers to primarily “yes/no” or short answer and does not give them the ability to convey their full experience. In addition, a focus on migraine attacks versus migraine days could cause HCPs to underestimate the number of days per month that a patient suffers from migraine.

Focusing heavily on frequency, with only 10% of questions dedicated to migraine impairment, leaves a crucial aspect of migraine assessment out of the conversation. It is perhaps not surprising then that over half of patients and HCPs were misaligned in post-visit interviews. Previous studies25 have demonstrated that when HCPs received information about headache-related impairment in addition to symptoms, frequency, and pain intensity, their appreciation of the severity of the patient’s migraines increased, as did the likelihood that they would prescribe migraine-specific medication with more aggressive follow-up.

While the degree of misalignment found in this study may seem high, similar findings have been seen in other therapeutic areas45–47 suggesting that narrowly focused questions about frequency may be a poor communication strategy for understanding the impact of symptoms on a patient’s day-to-day experience and functioning.

Similar findings about preventive medication candidacy and discussion suggest that important opportunities for discussion are being missed as a function of HCPs’ communication styles that limit discussion of symptoms to frequency of occurrence. Prior research in headache suggests that physicians’ interpersonal style influences patient outcomes. For example, researchers at the University of Western Ontario found that patients’ belief that they had discussed headache fully with an informed physician at the beginning of the relationship was a strong predictor of resolution at 1 year48. It is clear from this and other studies that communication style and full exploration of headache symptoms positively influence outcomes of care including prevention and medication prescribing.

To improve in-office communication with migraine patients, it is recommended that HCPs integrate two patient-centered communication techniques. First, HCPs should ask migraine patients one open-ended question to assess the level of disability and the impact of migraine on patients’ daily lives, both during and between attacks49. One example is to ask, “How do your migraines affect your daily life?” Other suggested questions can be found in Text Box 4.

Text Box 4: Suggested Open-Ended Questions

| • How do migraines make you feel—even when you aren’t having one? |

| • How does migraine impact your daily life? |

| • Can you describe the impact migraines have on your work, family, and social life? |

| • How does having migraine make you feel? |

| • Describe how your migraines affect you between attacks. |

There is evidence that the use of open-ended questions does not require significant additional time with patients50. In addition, patient-centered interviewing, which includes the use of open-ended questions, has also been linked to higher levels of both patient and HCP satisfaction51–53.

Second, HCPs should also utilize a technique sometimes called “ask-tell-ask”49,54,55 during clinical encounters to assess frequency as migraine days versus migraine attacks. A description of this technique can be found in Text Box 5.

Text Box 5: Example of How to Use “Ask-Tell-Ask” to Assess Migraine Frequency

| • ASK: |

| ○ “How many migraines do you get each month?” and |

| ○ “How long does each attack typically last?” |

| • TELL: Re-phrase what you’ve heard and ask for confirmation from the patient |

| ○ “So, you get 3 attacks that last 2 days each—meaning that you are disabled 6 days a month.” |

| • ASK: |

| ○ “Is that right?” |

Confirming migraine frequency in days rather than attacks can highlight HCP–patient misunderstandings and provide an opportunity to rectify them. These types of communication techniques have been shown to be efficient47 and have been linked to higher levels of both patient and HCP satisfaction50–53.

A phase II study undertaken by our research team to measure the impact of these two communication strategies on outcomes such as visit length, prevention discussions and new prescriptions with appropriate candidates, and HCP/patient satisfaction has shown promising results that have been reported in poster form (unpublished data).

This study has several limitations. The proportion of migraineurs in primary care and neurology settings who are candidates for preventive medication has not been studied directly elsewhere. Patients in this clinical sample suffered from more severe and/or more frequent migraines than migraineurs in the general population. The AMPPS demonstrated that 25.7% of migraineurs in the community are candidates for migraine preventive therapy and an additional 13.1% warranted consideration of prevention12. By contrast, in this sample, 41.7% of subjects were already on preventives, another 33.3% were candidates, and another 11.7% warranted consideration of prevention. The overall proportion of migraineurs in a mix of neurology and primary care settings who are candidates for prescription or consideration of prevention is likely to lie somewhere between the community prevalence documented in AMPPS and that observed in this study because previous studies demonstrate that both headache disability and frequency, the two parameters that determine prevention candidacy, are positively related to seeking care for migraine56.

In addition, future studies could also shed light on how, and if, primary and subspecialty care practitioners differ in their communication patterns or the expectations patients have of their interactions with each type. Additional research should also delve more deeply into differences in communication based on the type of HCP (i.e., physician versus NP or PA). Finally, further research should examine the role of physician and patient age and ethnicity in migraine communication conversations.

CONCLUSION

Current in-office communication about migraine is characterized by closed-ended, HCP-initiated questions and a lack of both open-ended questions and discussion of migraine-related impairment. These characteristics likely contribute to an under-appreciation of the need for preventive medication for more than half of those patients who would likely have benefited from it. This study adds to a growing number of others that link specific elements of communication in the HCP–patient encounter with clinical outcomes57. In particular, the communication deficits observed in the interactions studied can be easily rectified by adopting two patient-centered interviewing techniques:

an open-ended question to assess migraine impairment during and between attacks

the use of ask-tell-ask sequences to assess migraine frequency as days versus attacks

Use of these efficient and effective strategies in migraine visits should result in more appropriate appreciation of both migraine frequency and impairment as well as more successful identification of prevention candidacy. These techniques, while particularly useful in migraine visits, are equally applicable in many other chronic disease states, helping HCPs become more efficient communicators with all patient types.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ortho-McNeil Neurologics and Corey Eagan of MBS/Vox.

Conflict of interest summary Dr. Lipton has received grants from Allergan, Advanced Bionics Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck & Co., Inc., Neuralieve, Ortho-McNeil, Pfizer, Proethics Ltd., and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. He has consulted for Allergan, Ortho-McNeil, and Pfizer.Dr. Hahn has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil, and Pfizer. He has consulted with GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil, and Pfizer.Dr. Cady is the owner of Banyan Group, Inc., a medical clinic, clinical research facility, and meeting planning division that conducts medical education. Banyan Group has received grants from Abbott Laboratories, Advanced Bionics Corporation, Alizyme, Allergan, Alexza Pharmaceuticals, Aradgim Corporation, CAPNIA, Incorporated, Cipher Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Eisai, Inc., Endo Pharmaceuticals, GelStat Corp., GlaxoSmithKline, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, MAP Pharmaceuticals, Matrixx Initiatives, Inc., Merck & Co., Neuralieve, Novartis, Ortho-McNeil, Pfizer, Pozen Pharmaceutical Development Company, SCHWARZ Pharma AG, Torrey Pines, and Vernalis. He has received honoraria from ABT Associates, Allergan, Aradgim Corp., Atrix, Capnia, Endo, GlaxoSmithKline, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, MedPointe Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co., Inc., and Winston Laboratories, Inc. He has consulted for ABT Associates, Allergan, Aradgim Corp., Atrix, CAPNIA Incorporated, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, MedPointe Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co., Inc., and Winston Laboratories, Inc.Dr. Brandes has received clinical or educational support from Advanced Bionics Corporation, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Elan Pharmaceuticals, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis, Ortho-McNeil, Pfizer, Pozen Pharmaceutical Development Company, Sanofi-Aventis, UCB, Vernalis, and Winston Laboratories, Inc. She is on the Speakers’ Bureau/Advisory Board for Allergan, AstraZeneca, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Ortho-McNeil, and Pfizer.Ms. Simons has no conflicts to declare.Dr. Bain has no conflicts to declare.Ms. Nelson has no conflicts to declare.

Footnotes

Study design and subsequent publication were a joint effort by MBS/Vox, academic co-authors, and Ortho-McNeil Neurologics. All data collection and analysis was conducted by MBS/Vox. Funding was provided by Ortho-McNeil Neurologics.

References

- 1.Lipton RB, Diamond S, Reed M, Diamond ML, Stewart WF. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: results from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;4(17)638–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lipton RB, Stewart RF. Acute migraine therapy: do doctors understand what patients with migraine want from therapy? Headache. 1999;39(Suppl 2)S20–6. [DOI]

- 3.Lipton RB, Scher AI, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Steiner TJ, Stewart WF. Migraine in the United States: epidemiology and patterns of health care use. Neurology. 2002;58(6)885–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Barrier PA, Li JT, Jensen NM. Two words to improve physician–patient communication: what else? Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(2)211–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Mueller PS, Barrier PA, Call TG, Duncan AK, Hurley DL, Multari A, Rabatin JT, Li JT. Views of new internal medicine faculty of their preparedness and competence in physician–patient communication. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Silberstein S. Practice parameters: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Taylor F, Hutchinson S, Cady R, Harris L, Graff-Radford S. Diagnosis and management of migraine. Strategies to improve headache diagnosis and treatment in family practice. J Fam Pract. 2004;Suppl:S3–4. [PubMed]

- 8.Cottrell CK, Drew JB, Waller SE, Holroyd KA, Brose JA, O’Donnell FJ. Perceptions and needs of patients with migraines: a focus group study. J Fam Pract. 2002;5(12)142–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Dodick D. Patient perceptions and treatment preferences in migraine management. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(Suppl 1)19–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Levin M. Migraine headache: accurate diagnosis, targeted treatment. Adv Stud Med. 2004;44208–9.

- 11.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Stewart WF. Clinical trials of acute treatments for migraine including multiple attack studies of pain, disability, and health-related quality of life. Neurology. 2005;12Suppl 4S50–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF. Migraine prevalence, disease burden and need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5)343–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Roter D, Hall J. Doctors Talking with Patients/Patients Talking with Doctors: Improving Communication in Medical Visits. Westport: Auburn House; 1992.

- 14.Becker WJ. Communication with the migraine patient. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29(Suppl 2)1–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Edmeads J. Communication issues in migraine diagnosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29(Suppl 2):S8–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Franks P, Jerant AF, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Tancredi DJ, Epstein RM. Studying physician effects on patient outcomes: physician interactional style and performance on quality of care indicators. Soc Sci Med. 2006;6(2):2422–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Robinson G. Effective doctor patient communication: building bridges and bridging barriers. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29(Suppl 2):S30–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Sheftell FD. Communicating the right therapy for the right patient at the right time: acute therapy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29(Suppl 2):S33–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Baos V, Ester F, Castellanos A, Nocea G, Caloto MT, Gerth WC. Use of a structured migraine diary improves patient and physician communication about migraine disability and treatment outcomes. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(3):281–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Cady RK, Borchert LD, Spalding W, Hart CC, Sheftell FD. Simple and efficient recognition of migraine with 3-question headache screen. Headache. 2004;44:323–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Amatniek JC, Stewart WF. Tools for diagnosing migraine and measuring its severity. Headache. 2004;44:387–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Lipton RB, Dodick DD, Sadovsky R, Kolodner K, Endicott J, Hettiarachchi J, et al.. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care. The ID Migraineä validation study. Neurology. 2003;61:375–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Marcus DA, Kapelewski C, Jacob RG, Rudy TE, Furman JM. Validation of a brief nurse-administered migraine assessment tool. Headache. 2004;44:328–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Stewart WF, Lipton RB. Need for care and perceptions of MIDAS among headache sufferers study. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(Suppl 1):S5–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Holmes WF, MacGregor EA, Sawyer JPC, Lipton RB. Information about migraine disability influences physicians’ perception of illness severity and treatment needs. Headache. 2001;41(4):343–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Gumperz JJ. Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982.

- 27.Gumperz JJ. On Interactional Sociolinguistic Method. In: Sarangi S, Roberts C, eds. Talk, work and institutional order. Discourse in medical, mediation and management settings. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; 1999:453–71.

- 28.Hamilton HE. Symptoms and signs in particular. The influence of the medical condition on the shape of physician–patient talk. Commun Med. 2004;1(1):59–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Hamilton HE, Nelson M, Martin P, Cotler SJ. Provider–patient in-office discussions of response to hepatitis C antiviral therapy and impact on patient comprehension. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;44507–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Aranguri C, Davidson B, Ramirez R. Patterns of communication through interpreters: a detailed sociolinguistic analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:623–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Davidson B, Vogel V, Wickerham L. Oncologist–patient discussion of adjuvant hormonal therapy in breast cancer: results of a linguistic study focusing on adherence and persistence to therapy. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:36–40. [PubMed]

- 32.Davidson B, Blum D, Cella D, Hamilton H, Nail L, Waltzman R. Communicating about chemotherapy-induced anemia. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:36–40. 46. [PubMed]

- 33.Blumenfeld A, Tischio M. Center of excellence for headache care: group model at Kaiser Permanente. Headache. 2003;43(5):431–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Speer S, Hutchby I. From ethics to analytics: aspects of participants’ orientations to the presence and relevance of recording devices. Sociology. 2003;37(2):315–37. [DOI]

- 35.Dyche L, Swiderski D. The effects of physician solicitation approaches on ability to identify patient concerns. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(3):267–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Frankel R, Altschuler A, George S, Kinsman J, Jimison H, Robertson NR, Hsu J. Effects of exam-room computing on clinician–patient communication: a longitudinal qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):677–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277(8):678–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Lipton RB, Diamond M, Freitag D, Bigal M, Stewart WF, Reed ML. Migraine prevention patterns in a community sample: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Poster presented at the American Headache Society’s 47th Annual Scientific Meeting. June 2005. Philadelphia, PA.

- 39.Berry DL, Wilkie DJ, Thomas CR, Fortner P. Clinicians communicating with patients experiencing cancer pain. Cancer Invest. 2003;21(3):374–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Braddock CH, Synder L. The doctor will see you shortly. The ethical significance of time for the patient–physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1057–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Dowson AJ. Assessing the impact of migraine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2001;17(4):298–309. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Dueland AN, Leira R, Cabelli S. The impact of migraine on psychological well-being of young women and their communication with physicians about migraine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(8):1297–305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Rush SR, Yenkosky JP, Liberman JN, Bartleson JD, et al.. Migraine practice patterns among neurologists. Neurology. 2004;62:1926–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Robinson JD, Heritage J. Physicians’ opening questions and patients’ satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):279–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Greer J, Halgin R. Predictors of physician–patient agreement on symptom etiology in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(2):277–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Hagihara A, Odamaki M, Nobutomo K, Tarumi K. Physician and patient perceptions of the physician explanations in medical encounters. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(1):91–105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Abdel-Tawab N, Roter D. The relevance of client-centered communication to family planning settings in developing countries: lessons from the Egyptian experience. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(9):1357–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Headache Study Group. Predictors of outcome in headache patients presenting to family physicians—a one year prospective study. Headache. 1986;26:285–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Hahn SR. Communication in the Care of the Headache Patient. In: Silberstein S, Lipton RB, Dodick D, eds. Wolff's Headache and Other Head Pain. Eighth ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007:805–24.

- 50.Frymoyer JW, Frymoyer NP. Physician–patient communication: a lost art? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10(2):95–105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Ishikawa H, Takayama T, Yamazaki Y, Seki Y, Katsumata N. Physician–patient communication and patient satisfaction in Japanese cancer consultations. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(2):301–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Martin LR, Jahng KH, Golin CE, DiMatteo MR. Physician facilitation of patient involvement in care: correspondence between patient and observer reports. Behav Med. 2003;28(4):159–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Roter DL, Larson S, Shinitzky H, Chernoff R, Serwint JR, Adamo G, Wissow L. Use of an innovative video feedback technique to enhance communication skills training. Med Educ. 2004;38(2):145–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Tulsky JA, Fryer-Edwards K. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(3):164–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Boyle D, Dwinnell B, Platt F. Invite, listen, and summarize: a patient-centered communication technique. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):29–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Simon D. Medical consultation for migraine: results from the American Migraine Study. Headache. 1998;38:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS, Frankel RM. Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Medical Care. 2007;45(4):340–9. [DOI] [PubMed]