Abstract

Background

Although experts advocate that physicians should express empathy to support family members faced with difficult end-of-life decisions for incapacitated patients, it is unknown whether and how this occurs in practice.

Objectives

To determine whether clinicians express empathy during deliberations with families about limiting life support, to develop a framework to understand these expressions of empathy, and to determine whether there is an association between more empathic statements by clinicians and family satisfaction with communication.

Design

Multi-center, prospective study of audiotaped physician-family conferences in intensive care units of four hospitals in 2000–2002.

Measurements

We audiotaped 51 clinician-family conferences that addressed end-of-life decisions. We coded the transcripts to identify empathic statements and used constant comparative methods to categorize the types of empathic statements. We used generalized estimating equations to determine the association between empathic statements and family satisfaction with communication.

Main Results

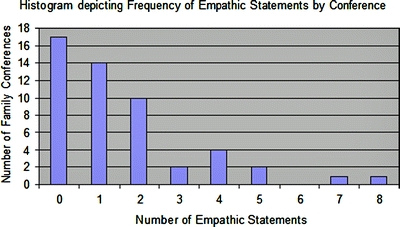

There was at least one empathic statement in 66% (34/51) of conferences with a mean of 1.6 ± 1.6 empathic statements per conference (range 0–8). We identified three main types of empathic statements: statements about the difficulty of having a critically ill loved one (31% of conferences), statements about the difficulty of surrogate decision-making (43% of conferences), and statements about the difficulty of confronting death (27% of conferences). Only 30% of empathic statements were in response to an explicit expression of emotion by family members. There was a significant association between more empathic statements and higher family satisfaction with communication (p = 0.04).

Conclusions

Physicians vary considerably in the extent to which they express empathy to surrogates during deliberations about life support, with no empathic statements in one-third of conferences. There is an association between more empathic statements and higher family satisfaction with communication.

KEY WORDS: surrogate decision-making, empathy, life support, communication

INTRODUCTION

Family members of patients with critical illness frequently receive bad news about a patient’s prognosis and participate in decisions to withhold or withdraw life support.1 Families view the role of surrogate decision-maker as emotionally challenging,2–5 and many subsequently have substantial symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress.6 Experts suggest that explicit statements of empathy by physicians may be an important source of support for family members functioning as surrogate decision-makers.7 Moreover, a growing body of research suggests that empathy can facilitate more accurate interviewing and support individuals in making decisions based on their own values.8,9 There is also evidence that empathy from physicians contributes to better patient outcomes9,10 and higher levels of professional satisfaction among physicians.8,10,11 In primary care settings, physicians’ empathy has been shown to be essential to patient enablement, which contributes to perceived change and well being.12

There is considerable controversy about the appropriate definition of empathy. Some definitions focus on the cognitive aspect of empathy, which is the physicians’ ability to accurately recognize an individual’s emotional state.13 Others focus on the emotive aspect of empathy, which is the ability to imagine how an individual is feeling.14,15 Yet others focus on the behavioral aspect of empathy, which is the physician’s ability to convey an understanding of those emotions back to the patient or surrogate.16–18 Some experts argue that the key aspects of empathy are the cognitive and emotional aspects and place relatively less importance on whether these aspects produce an explicit empathic statement.13–15 Others contend that the phenomenon is too complex to be divided into discrete categories.9 The controversy around defining empathy yields several different approaches to studying empathy in clinical encounters. Some researchers focus on the internal manifestations of empathy, using instruments to measure cognition or emotion.19 Others focus on the external manifestations, using instruments to measure behaviors.16–18 The behavioral aspect of empathy is particularly relevant when studying surrogate decision-making because surrogates experience substantial emotional burdens,2–5 and physicians have an obligation to support surrogates during this process.5,20

Although much has been written about the importance of empathy in the doctor-patient relationship, we are aware of no studies investigating whether and how physicians express empathy to family members functioning as surrogate decision-makers. The absence of these data is problematic because it limits our ability to understand and improve this challenging and important aspect of medicine that is commonly encountered in hospital wards, nursing homes, and intensive care units. We therefore conducted this study to determine how physicians express empathy during discussions with surrogates about major end-of-life treatment decisions, to develop a framework to better understand these expressions of empathy, and to determine whether there is an association between physician empathy and family satisfaction with communication (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of empathic statements by conference.

METHODS

Study Design, Patients and Setting

We conducted a multi-center cross-sectional study from August 2000 to July 2002 in four Seattle-area hospitals, including a county hospital, a university hospital, and two community hospitals. Study procedures were described previously, although no prior report has analyzed the amount or type of empathic communication.21–23 Through daily contact with charge nurses, we identified eligible ICU family conferences meeting all of the following criteria: (1) occurring on weekdays; (2) including family and physicians; (3) all participants spoke English well enough not to require the use of an interpreter. In order to specifically identify conferences in which there would be deliberation about major end-of-life treatment decisions, we asked the patient’s attending physician if he/she anticipated that there would be discussion of withholding or withdrawing treatment or discussing bad news. The conferences represent a consecutive sample of scheduled family conferences that occurred on weekdays. We excluded patients under 18 years old. The attending physician and bedside nurse provided permission to approach each family. If, after talking with investigators, all participants gave informed consent, the conference was audiotaped. The participants were aware that the general purpose of the study was to examine how clinicians and family members communicate, but were not aware of the specific focus on empathic communication. The Institutional Review Board at each hospital approved all procedures.

Qualitative Data Coding

We analyzed transcripts of the audiotaped conferences using constant comparative methods to inductively develop a descriptive framework of the various types of empathic statements that occur.24–26 We defined empathic statements as any statement by a clinician that explicitly acknowledged an emotion or an internal state of a family member.17,18 To develop the preliminary coding scheme, investigators (RBS, DBW,JS) independently performed open coding in which we read and performed line-by-line coding on a subset of the transcripts to identify themes and concepts relating to clinicians’ empathic communication. As concepts accumulated and distinctions between concepts became more refined, similar concepts were grouped into conceptual categories. These categories were developed further by comparing the categories between transcripts. All investigators reviewed this preliminary framework and through multiple investigator meetings arrived at consensus on the coding framework.24,25

To understand the relationship between family expressions of emotion and clinician empathy, we coded each family expression of emotion, defined as an explicit statement referring to any negative emotion such as anger, sadness, frustration, or helplessness. The definition included annotations in the transcripts describing emotional utterances such as crying or sobbing. We quantified the proportion of empathic statements that occurred in direct response to family expressions of emotion, defined as an empathic statement within two speech turns of the family expression of emotion. A speech turn is defined as an uninterrupted verbal expression by a participant in a conversation.

Reliability of the Coding

To test the reliability of the coding procedures, we compared coding performed independently by two investigators on 20% of the conferences. Coders were blinded to the coding of the other investigators, to the characteristics of the conference participants, and to family satisfaction with communication (described below). The kappa statistic for identifying and categorizing empathic statements was 0.93, considered excellent reliability.27

Validity of the Findings

In order to enhance the validity of the coding framework, we drew on the expertise of a multidisciplinary team for its initial development and refinement. Areas of investigator training included critical care medicine, psychology, health services research, doctor-patient communication, and bioethics. A multidisciplinary approach minimizes the chance that individual bias threatens the validity of the findings.28

Assessment of Demographics and Conference Characteristics

After each conference, family members completed a questionnaire reporting their demographic characteristics and answered a question assessing their satisfaction with communication during the conference on a 0–10 scale, as follows: “Overall, how would you rate the doctor’s communication with you during the family conference?” The physician who conducted each conference completed a questionnaire assessing his or her demographic characteristics.

Statistical Analysis

For each conference, we determined the total number of empathic statements by the clinicians. We used linear regression with generalized estimating equations to determine whether there was an association between the number of empathic statements and family satisfaction with communication. Because some physicians conducted more than one family conference, and because family satisfaction in each conference was assessed by multiple family members, we assessed for clustering in family satisfaction scores by physician or by conference. We found no evidence of clustering by physician. However, there was a correlation between the family members’ satisfaction scores when multiple family members assessed the same conference. We therefore present the association between empathy and family satisfaction adjusted for this clustering. No other covariates were included in the final model because there were no significant associations (defined as p < 0.15) between other covariates and the number of empathic statements. Regression assumptions (e.g., influence, outliers and non-constant variance) were verified using graphical techniques. The linearity assumption was also met, as evidenced by the absence of departure from linearity on graphical analysis as well as by statistical testing. All analyses were performed using Stata 8.0 software (StataCorp; College Station, TX), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 111 eligible families were identified. Seventeen were excluded at the request of the physician or nurse, and two more families were excluded for risk management reasons. An additional 24 family members refused to speak with study personnel after reviewing the study pamphlet. Of the 68 families approached by study personnel, 51 agreed to participate. Overall, 46% (51/111) of eligible physician-family pairs agreed to participate in the study.

Demographic characteristics of the patients, physicians, and family members who participated in the conferences are described in Table 1. A total of 27 physicians conducted a single conference, 7 conducted 2 conferences, 2 conducted 3 conferences, and 1 physician conducted 4 conferences. A total of 221 clinicians participated in the conferences. The number of clinicians present ranged from 1 to 12 with a mean of 4.3. A total of 50 nurses participated in 41 of the family conferences, 25 social workers participated in 24 of the family conferences, and 12 chaplains, priests, or nuns participated in 12 of the family conferences. A total of 227 family members participated in the conferences. The number of family members in each conference ranged from 1 to 13, with an average of 4.5. Of these, 169 returned family questionnaires. The in-hospital mortality rate of the patients was 80% (41/51).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients, Family Members, and Clinicians

| Characteristics | Patients N = 51 n (%) | Family members/loved ones N = 169, n (%) | Physicians leading conferences N = 35, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 26 (51) | 101 (60) | 12 (34) |

| Male | 25 (49) | 68 (40) | 23 (66) |

| Race/ethnicity* | |||

| White | 31 (61) | 136 (81) | 30 (86) |

| African American | 7 (14) | 14 (8) | 0 |

| Hispanic | 2 (4) | 6 (4) | 2 (6) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (2) | 5 (3) | 4 (11) |

| Native American | 1 (2) | 10 (6) | 0 |

| Other/undocumented | 9 (18) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Admission diagnosis | |||

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 9 (18) | ||

| End-stage liver disease/gastrointestinal bleed | 8 (16) | ||

| Trauma | 8 (15) | ||

| Sepsis/infection | 7 (14) | ||

| Respiratory failure | 6 (12) | ||

| Cardiac failure/myocardial infarction | 5 (10) | ||

| Other | 8 (15) | ||

| Relationship to patient | |||

| Spouse/partner | 17 (10) | ||

| Child | 35 (21) | ||

| Sibling | 34 (20) | ||

| Parent | 20 (12) | ||

| Friend | 9 (5) | ||

| Other relative | 52 (31) | ||

| Other | 2(1) | ||

| Staff position | |||

| Attending clinician | 20 (56) | ||

| Resident or fellow | 16 (44) | ||

| Medical specialty | |||

| Internal medicine | 26 (74) | ||

| Neurology | 5 (14) | ||

| Surgery | 3 (7) | ||

| Anesthesia | 1 (3) | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 60 (20.3) | 48 (15.8) | 38 (9.5) |

| Years in practice | 12.4 (9.7) |

*Sums are greater than 169 family members and 35 physicians because some individuals identified with more than one race/ethnicity.

In 44 of the 51 (86%) conferences, there was discussion of withdrawing life support. In 19 of 51 (37%) conferences Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders were discussed. The average length of the conferences was 32 ± 14.8 min.

Frequency and Categories of Empathic Statements

In 33% (17/51) of conferences there were no empathic statements. In the remaining 34 conferences, the average number of empathic statements per conference was 2.4 ± 1.7 (range 1–8) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Recommendations for Physicians

| Recommendation | Example |

|---|---|

| Take a moment at the beginning of a family conference to inquire into the families’ emotional state. | “Before we talk about how your father is doing, tell me how you are. How are you holding up?” |

| Acknowledge both verbal and non-verbal expressions of emotion. Use these expressions of emotion as opportunities to support family members. | “I agree..it really is sad. It is one of the toughest things I encounter to see a young person in this situation” |

| Create empathic opportunities by acknowledging that most families face a significant emotional burden when a loved one is critically ill or dying. | “Many families find this to be one of the hardest things they have ever been through. How are you doing?” |

Categories of Empathic Statements

Using the coding methods described above, we identified three main topics about which clinicians’ expressed empathy (Tables 2 and 3): the experience of having a loved one in an ICU, the hardships of surrogate decision-making, and the difficulty of confronting death.

Table 2.

Framework and Examples of Empathic Statements during ICU Family Conferences

| Empathy about surrogate decision-making | Withholding or Withdrawing Life Support: Clinician: “If this feels like it’s really hard, it’s because it is really hard... you’re not missing, you’re not missing the right answer here. It’s not like there is a right answer.” |

| Determining Patient’s Wishes Clinician: “It’s a real hard position to be in, to try to put aside your own personal feelings for what you want for him and obviously we all want him to get better and go out himself, but, you’re in a role where you’re his advocate." | |

| Fear of Making a Mistake Clinician: “Sometimes when bad things happen people have a tendency to look back and try to think- my gosh, was there something we missed or was there something that could’ve been done earlier? I have to say in her case I don’t think that would be true.” | |

| Empathy about critical illness in a loved one | Making Sense of the Disease Process Clinician: "And I know it’s very important to try and understand as best as possible what happened to see if there’s anything that makes sense and, unfortunately, so often it just doesn’t make sense.” |

| Difficulty in Understanding Medical Information Clinician:” I know it’s a lot of information to take in, so I want you guys to feel free to ask questions and, and anything that you don’t understand or have questions about." | |

| Physical Changes of Loved Ones Who are Critically Ill Family: “You keep everything in perspective (laughs), no but just overall, I was scared, I was scared coming in today. She looked like hell. Excuse my language, but...;" Clinician: “Yes, it’s hard to see her like that.” | |

| Receiving Bad News Clinician: “It’s hard to understand why something bad just can happen to anyone, and when it’s someone you love and care for, that’s even more difficult.” | |

| Uncertainty Clinician: “We pretty much have to take it day by day, and I know that it’s so hard for you guys, it’s just the not knowing from day to day.” | |

| Empathy about confronting the death of a family member | Helplessness Family: “...But this just can’t be, I lost my wife, I just... I just feel really bad and I can’t do nothing about it." Clinician: “We know, it’s so frustrating. |

| Dying Clinician: "Letting go is difficult, but I think you’re doing him a great service by honoring his wishes at this time." |

Table 3.

Empathic Statements by Category in the 51 ICU Family Conferences

| Proportion of conferences in which category was addressed no. (%) (N = 51) | Number of empathic statements (N = 81) no. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Content | ||

| Empathy about surrogate decision-making | 22 (43%) | 34 (42%) |

| Empathy about critical illness in a loved one | 16 (31%) | 31 (38%) |

| Empathy about anticipating the death of a family member | 14 (27%) | 16 (20%) |

| Context | ||

| In response to explicit family emotions | 13 (25%) | 24 (30%) |

| Anticipating emotions/in response to implicit emotions | 41 (80%) | 57 (70%) |

Empathy about Critical Illness in a Loved One

In 31% (16/51) of conferences, clinicians expressed empathy about the emotional difficulty of having a critically ill family member. This category of empathic statements related specifically to the family’s experience in dealing with a loved one’s critical illness, including emotions related to disease course, the difficulty of understanding medical information, tolerating the changed physical appearance of critically ill loved ones, and uncertainty in diagnosis and prognosis.

The example below highlights a case in which the patient’s ICU stay was long and difficult, and the clinician directly acknowledges the emotional difficulty this created for the family:

FAMILY: What I’m trying to say (crying), I’m sorry.

CLINICIAN: That’s okay. She’s really sick and she’s been, it’s been a long haul, a rollercoaster ride for you and I understand.

The issue of uncertainty in prognosis or not knowing the cause of critical illness was particularly difficult for family members. The example below takes place after several minutes of discussion about what might have caused a patient’s sudden illness:

CLINCIAN: ...And I, and I appreciate your frustration about not knowing, and you know, it’s so hard when you’re not there, nobody was there to know for sure what happened and I appreciate that frustration and hope that down the line some of those questions will get answered for you...

Empathy about Surrogate Decision-Making

In 43% (22/51) of conferences clinicians expressed empathy to family members about the difficulty of surrogate decision-making. These empathic statements addressed emotions related to determining the patient’s wishes, separating out family members’ own values from those of the patient, and the fear of making a mistake in decision-making. In the example below, the family member is struggling with the decision about whether to withdraw life support in the face of a catastrophic neurologic event. The focus of the conversation has been on determining the patient’s wishes:

FAMILY: It’s not easy, but (sobbing)

CLINICIAN: No, it’s a tough decision, but I really think you know him very well.

Participating in decision-making sometimes created a significant emotional burden for family members. In the example below, the clinician attempts to alleviate that burden with empathy. The family members felt that the patient would not want further life support, but were having difficulty making a decision. The physician acknowledges the family’s internal experience (difficulty making a decision), and also reassures them that the decision is appropriate:

CLINICIAN: It’s important to all of us that you all, a year from now, can look back and say, we with the help of the doctors, we did the right thing. We, and what we’re recommending to you, now, we’re trying to take the weight of the world off your shoulders. To me, she is gone, and I, what I’m advocating is stepping away, getting out of the way at what’s really a natural process that started a couple of days ago and not interfering with somebody’s natural, comfortable end. And I know that’s very hard.

Empathy about Confronting the Death of a Family Member

Clinicians also expressed empathy around the difficulty of watching a loved one die. This type of empathic statement occurred in 28% (14/51) of conferences and included empathic statements related to the process of accepting the impending loss of a loved one, being helpless in face of the disease, coping with the dying process, and general emotional reactions to anticipated loss. In the example below a clinician addresses the emotional difficulty a family experiences in watching their adult daughter deteriorate from substance abuse:

FAMILY:...and you just have to sit there with your own child and see her slowly disintegrate, I mean, because this wasn’t just all of a sudden, this has been happening for some years.

(Pause)

FAMILY: That’s hard to watch.

CLINICIAN: Yeah, it’s hard to watch. As a parent myself, I can’t imagine.

In the example below a clinician responds to the sadness of a family member whose loved one has had a sudden deterioration from a secondary infection and is near death:

CLINICIAN: It’s a common complication and the most common thing that people die from after strokes. If they don’t die from the stroke, they die from infection, or pneumonia or something else.

FAMILY: Sad.

CLINICIAN: It is sad.

Families’ Expressed Emotions and Clinicians’ Empathic Statements

There were 169 expressions of emotion by family members in the 51 conferences. At least one expression of emotion occurred in 78% (40/51) of conferences. Overall, 30% (24/81) of empathic statements were in direct response to an explicitly expressed emotion by the family. The remaining 70% of empathic statements involved the clinicians anticipating the emotional experience of the family or inferring emotion from implicit or non-verbal cues.

For example, clinicians sometimes followed the delivery of bad news with an acknowledgement of the difficulties families face when receiving news of a poor prognosis. The example below illustrates a physician anticipating that news about prognosis will be hard for families to hear:

Clinician: We don’t have the means at this point to permanently make any of the tumors we talked about go away, since it’s in two spots in the brain right now. This is hard to talk about and hard to hear about your wife and your sister, but I want to be very honest with you about where we stand in this situation.

Association between Empathy and Family Satisfaction

On a 10-point scale, the average family satisfaction with communication score was 9.0 ± 1.3; (range 1 – 10). There was no evidence of clustering in family satisfaction scores by physician among physicians who conducted more than one conference. There was a statistically significant association between more empathic statements and higher family satisfaction with communication (p = 0.04). For each increase in the number of empathic statements by one, there was a 0.12 increase in the family satisfaction score (standardized effect size: 0.1). For conferences in which there were no empathic statements, the average family satisfaction score was 8.9 compared to 9.7 in conferences in which there were at least two empathic statements (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Although empathy is widely advocated as an important part of the practice of medicine,29,30 this study provides new information about variability in whether and how clinicians express empathy during end-of-life decision making with surrogate decision-makers. One-third of conferences contained no empathic statements by clinicians. When present, clinicians’ empathic statements addressed the emotional difficulties frequently encountered in intensive care units: having a loved one who is critically ill, shouldering the burden of surrogate decision-making, and confronting death.

Despite high overall satisfaction with communication by surrogates-a finding consistent with a recent multicenter study31-we observed a significant association between more empathic statements and higher family satisfaction with communication. This finding provides a measure of empiric support for expert recommendations advocating more empathic communication when discussing bad news with family members of critically ill patients.7,29 Although this observational association provides important preliminary evidence, a next step in this area of research will be to determine whether interventions to increase empathic communication during end-of-life decision making can improve surrogates’ experiences and the quality of the decision-making process.6

There were no empathic statements from physicians in one third of the conferences. In light of the well-documented emotional distress many family members face when making decisions to limit life support,6 we feel this is an important finding that merits further investigation. Prior reports document that empathy declines during the years of undergraduate medical education13,32 and residency.33,34 These trends highlight the importance of identifying the barriers to empathic communication and developing tailored interventions to improve physicians’ skills in this regard. Although several interventions have documented efficacy in improving medical students’ empathic skills, little is known about strategies to improve this aspect of care among post-graduate trainees and practicing physicians.35

The results of this study provide an empirically derived starting point for physicians interested in increasing their empathic skill (Table 4). Physicians might consider simply asking family members how they are doing and acknowledging the difficulty of having a loved one in the ICU, such as “I imagine it might be hard for you to have your father so sick.” Although this seems simplistic, we observed that such empathic statements were absent from the majority of physician-family conferences. Second, it may be beneficial to remain vigilant for emotions, both explicit and implicit, that arise during discussions and use these expressions of emotion as opportunities to support family members. Lastly, empathic statements need not only come in response to emotions expressed by family members. Some family members may not feel comfortable expressing difficult emotions with physicians, but also may benefit from empathic communication. It therefore may be valuable to “create” empathic opportunities by acknowledging that most families face a significant emotional burden when a loved one is critically ill or dying. These suggestions expand on existing recommendations for surrogate decision-making by providing concrete examples of how physicians can emotionally support family members acting as surrogates.20,36

This study also adds an important methodological dimension to the study of empathy in medicine. Prior studies have looked for empathic statements directly in response to emotion from family members, called “empathic opportunities.”17,18 Our study examined empathic statements by physicians throughout the encounters and revealed that only 30% of empathic statements were in direct response to an explicit expression of emotion by family members. Rather than waiting for empathic opportunities to occur, we observed that physicians actively create empathic opportunities by anticipating and expressing empathy about the common emotional difficulties surrogates face in intensive care units. This approach may yield more complete information about empathic communication when assessing the effectiveness of interventions to improve physicians’ skill at communicating empathy.

This study has several limitations. First, just under 50% of the eligible conferences were audiotaped. Our response rate reflects the well-documented difficulty of conducting clinical research on family members of patients near death.37 Our findings may not generalize to families unwilling to participate in this type of research. Second, it is important to note that there are other approaches to defining and measuring empathy,13,38 each of which has added important insight to the study of empathic communication in medicine. Our definition of empathy and methodology to investigate empathy relied on analysis of clinicians’ statements, not on whether those statements were perceived as empathic by the family. Some family members may not view the acknowledgement of their emotions as empathic.39 The strength of this definition for the current study is that it allows for a grounded description of how clinicians raise and respond to family members’ emotions. The observed association between more empathic statements and higher family satisfaction with communication provides some evidence that this definition of empathy captured an aspect of communication that was viewed favorably by families. Some researchers have also questioned whether the acknowledgement of emotion is sufficient for empathy to have occurred.40 This question is an important area for future research. A further limitation of our data is that it is based on audiotapes and therefore may have missed important elements of non-verbal communication that could be captured with video.41 Finally, our study was designed to provide an in-depth examination of expressions of empathy and was not designed to allow us to determine predictors of expressions of empathy during clinical encounters. This important area of inquiry has been addressed by other investigators.17,42

In conclusion, we found substantial variability in the amount and nature of empathic communication during physician-family conferences in ICUs, with no expressions of empathy in one-third of conferences. We also found an association between more empathic statements and higher family satisfaction with communication. Rigorous research is needed to examine the extent to which empathy is teachable and whether such training improves the quality of medical decisions and the families’ experience of surrogate decision-making.

Acknowledgments

None

Funding Information This project was supported by NIH grants: (1) National Institute of Nursing Research RO1NR005226 (JRC and RAE) and (2) KL2 RR024130 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. (DBW).

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Prendergast TJ, Luce JM. Increasing incidence of withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(1):15–20, Jan. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Braun UK, Beyth RJ, Ford ME, McCullough LB. Voices of African American, Caucasian, and Hispanic surrogates on the burdens of end-of-life decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):267–274, Mar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Garland MJ, Nelson CA. Decisions about life-sustaining treatment. Impact of physicians’ behaviors on the family. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(6):633–638, Mar 27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Nelson CA, Fields J. Family decision-making to withdraw life-sustaining treatments from hospitalized patients. Nurs Res. 2001;50(2):105–115, Mar-Apr. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Surviving surrogate decision-making: what helps and hampers the experience of making medical decisions for others. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1274–1279, Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994, May 1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Tulsky JA, Fryer-Edwards K. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(3):164–177, May-Jun. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Elliot R, Watson JC, Goldman RN, Greenberg LS. Learning emotion-focused therapy: the process experiential approach to change: APA Press; 2003.

- 9.Halpern J. From Detached Concern to Empathy: Humanizing Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford Unversity Press; 2001.

- 10.Larson EB, Yao X. Clinical emapthy as emotional empathy. JAMA. 2005;293(9):1100–1106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Shanafelt TD, West C, Zhao X, et al. Relationship between increased personal well-being and enhanced emapthy amoung internal medicine residents. J Gen Int Med. 2005;20(7):559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Mercer SW, Reilly D, Watt GCM. The importance of empathy in the enablement of patients attending the Glasgow Homeopathic Hospital. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(484):901–905. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, Vergare M, Magee M. Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1563–1569, Sep. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Spiro H. What is empathy and can it be taught? Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(10):843–846, May 15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Zinn W. The empathic physician. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(3):306–312, Feb 8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Bellet PS, Maloney MJ. The importance of empathy as an interviewing skill in medicine. J Am Med Assoc. 1991;266:1831–1832. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Bylund CL, Makoul G. Empathic communication and gender in the physician-patient encounter. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:207–216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277(8):678–682, Feb 26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Bohart A, Greenberg L. Empathy and Psychotherapy: An Introductory Overview. In: Bohart A, Greenberg L, eds. Empathy Reconsidered: New Directions in Psychotherapy. 2Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999:3–25.

- 20.Torke AM, Alexander GC, Lantos J, Siegler M. The physician-surrogate relationship. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(11):1117–1121, Jun 11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Studying communication about end-of-life care during the ICU family conference: development of a framework. J Crit Care. 2002;17(3):147–160, Sep. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1484–1488, Jul. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.West HF, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Curtis JR. Expressions of nonabandonment during the intensive care unit family conference. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(4):797–807, Aug. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Adline Publishing Company; 1967.

- 25.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998.

- 26.Glaser BG. The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative Analysis. In: McCall GJ, Simmons JL, eds. Issues in Participant Observation. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1969.

- 27.Sackett DL, Haynes RBH, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical Epidemiology: A Basic Science for Clinical Medicine. 2Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1991.

- 28.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;345(Pt 2):1189–1208, Dec. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Prendergast TJ, Puntillo K. Withdrawal of life support: intensive caring at the end of life. JAMA. 2002;288(21):2732–2740, Dec 4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Mercer SW, Reynolds W. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52 (Supplement):S9–S12. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, et al. Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: results of a multiple center study. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(7):1413–1418, Jul. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Diseker RA, Michielutte R. An analysis of empathy in medical students before and following clinical experience. J Med Educ. 1981;56(12):1004–1010, Dec. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Bellini LM, Shea JA. Mood change and empathy decline persist during three years of internal medicine training. Acad Med. 2005;80(2):164–167, Feb. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Bellini LM, Baime M, Shea JA. Variation of mood and empathy during internship. Jama. 2002;287(23):3143–3146, Jun 19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Stepien KA, Baernstein A. Educating for empathy. A review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):524–530, May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Proxy decision making for incompetent patients. An ethical and empirical analysis. JAMA. 1992;267(15):2067–2071, Apr 15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Krouse RS, Rosenfeld KE, Grant M, et al. Palliative care research: issues and opportunities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(3):337–339, Mar. [PubMed]

- 38.Mercer SW, McConnachie A, Maxwell M, Heaney DH, Watt GCM. The development and preliminary validation of the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure in general practice. Fam Pract. 2005;21(6):699–703. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Barkham M, Shapiro DA. Counselor Verbal Response Modes and Experienced Empathy. J Couns Psychol. 1986;33(1):3–10. [DOI]

- 40.Halpern J. What is clinical empathy. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:670–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Branch WT, Malik TK. Using windows of opportunities in brief interviews to understand patients’ concerns. JAMA 1993;(169):1667–1668. [PubMed]

- 42.Roter D, Stewart S, Putnam N, Lipkin M. Communication patterns of primary care physicians. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277:350–356. [DOI] [PubMed]