Abstract

Background

Treatment decisions about menopause are predicated on a transient duration of vasomotor symptoms. However, evidence supporting a specific duration is weak.

Objective

To estimate the natural progression of vasomotor symptoms during the menopause transition by systematically compiling available evidence using meta-analytic techniques.

Data Sources

We searched MEDLINE, hand searched secondary references in relevant studies, book chapters, and review papers, and contacted investigators about relevant published research.

Review Methods

English language, population-based studies reporting vasomotor symptom prevalence among women in menopausal transition in time intervals based on years to or from final menstrual period were included. Two reviewers independently assessed eligibility and quality of studies and extracted data for vasomotor symptom prevalence.

Results

The analyses included 10 studies (2 longitudinal, 8 cross sectional) with 35,445 participants. The percentage of women experiencing symptoms increased sharply in the 2 years before final menstrual period, peaked 1 year after final menstrual period, and did not return to premenopausal levels until about 8 years after final menstrual period. Nearly 50% of all women reported vasomotor symptoms 4 years after final menstrual period, and 10% of all women reported symptoms as far as 12 years after final menstrual period. When data were examined according to symptom severity (‘any’ vs. ‘bothersome’), bothersome symptoms peaked about 1 year earlier and declined more rapidly than symptoms of any severity level.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest a median symptom duration of about 4 years among symptomatic women. A longer symptom duration may affect treatment decisions and clinical guidelines. Further prospective, longitudinal studies of menopausal symptoms should be conducted to confirm these results.

BACKGROUND

As many as 15 to 30 percent of women consult physicians annually during the menopause transition1,2, typically for symptom relief from vasomotor symptoms (i.e., hot flashes and night sweats)2. Although some medical education materials and clinical guidelines3–5 report that most women experience vasomotor symptoms for 6 months to 2 years, many research findings report the duration as 4 years or more1,6. Treatment decisions for menopausal symptoms are based on the transitory nature of these symptoms7.

The most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms, menopausal hormone therapy (HT), has a risk:benefit profile that changes according to the duration and timing of treatment8. The risks and benefits of HT depend on duration of exposure to HT, and a woman’s risk for incurring side effects and benefits associated with HT change as she ages. Some risks (i.e., stroke) are only apparent after 1–2 years of treatment, while others [venous thrombotic events (VTE)] appear much sooner9. Some risks (e.g., breast cancer) increase with longer duration of treatment10, while others (VTE and possibly coronary artery disease) appear to decrease over time.

Most clinical guidelines recommend using the lowest dose of HT for the shortest possible amount of time, based on assumptions about symptom duration and the known benefits of HT11,12. Clinicians have advised women to attempt to discontinue HT every 6–12 months to determine if menopausal symptoms persist, as using HT for 1–2 years carries fewer risks than longer-term treatment. Guidelines assert that short-term treatment should be adequate to control symptoms during the menopause transition11,13. However, symptoms may last longer than previously expected. A recent NIH consensus statement noted that there are limited data describing the duration of menopausal symptoms because studies do not often follow women beyond the first 2 years of postmenopause14,15. Because the expected duration of symptoms is a critical factor in determining whether a woman decides to take HT, better evidence about symptom duration is needed.

Although some suggest that vasomotor symptoms may last longer than 1–2 years for a minority of women5, the average duration of symptoms and predictors of the length of symptoms are poorly described. Measuring the duration and natural progression of menopausal symptoms is challenging because of the variable symptoms included and attributed to menopause, the lack of standard definitions of symptoms, differences in recording symptom severity, the need to adjust for the use of any treatments that may relieve symptoms, the self-selection of women according to symptom severity, and recall error. Moreover, the information available is based on studies where the symptoms were artificially truncated at the onset or the end of observation periods; symptoms may have begun before the study began and may have extended beyond the length of the study.

The studies that are frequently referenced (e.g.,16,17) as establishing the duration of menopausal symptoms were not specifically designed to measure the length of time between the onset and cessation of menopausal symptoms. The definition and measurement of vasomotor symptoms, and the populations surveyed, varied considerably across these studies13. One of the most often cited studies reporting primary data about menopausal symptom duration16 relied on symptom recall 5 or more years after a woman’s final menstrual period (FMP) and did not report any numerical data on symptom prevalence. Another frequently cited study17 did not report symptom duration, but instead reported the percent of women who experienced hot flashes in various time intervals after menopause: 1–2 years (35%), 3–5 years (28.6%), 6–10 years (26.2%), and 11+ years (10.3%). Thus, the majority (65%) of women in this study experienced hot flashes that lasted longer than 2 years, and 10.3% were still reporting hot flashes at the conclusion of the study. However, later references to this study6,18 commonly misinterpreted the data and stated that the majority of women experienced hot flashes for 1–2 years. In addition, neither of the aforementioned studies accounted for the use of HT or the potential truncation of symptoms at the beginning or end of the study. Many longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have subsequently been published that can potentially provide more robust data that can be used to address symptom duration.

The purpose of this study was to estimate the natural progression of vasomotor symptoms during the menopause transition by systematically compiling available evidence using meta-analytic techniques.

METHODS

Search Strategy We performed a comprehensive Medline literature review in November 2007 to retrieve all English language studies that contained information on vasomotor symptom prevalence during the menopause transition. MeSH terms included: vasomotor.mp. or exp vasomotor system/(hot flash$ or hot flush$ or night sweat$).mp. body temperature regulation/or sweating/combined with menopause/ OR climacteric/. We also searched the bibliography of relevant articles, relevant clinical manuals14,19, chapters in text books, and review papers. We contacted authors of relevant papers for additional information on their data as needed.

Study Selection To minimize selection and sampling bias, we excluded studies that were clinic-based and those that were randomized trials of menopausal treatment. We included both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies. If two or more studies described the same cohort, the single paper that presented the most complete data was selected. Data were extracted and independently rated by two readers (NC and MP). Final inclusion was decided by consensus. We rated the quality of studies using the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for nonrandomized studies in meta analyses20.We defined vasomotor symptoms as any of the following: hot flushes, hot flashes, night sweats, and cold sweats. We did not attempt to disaggregate specific vasomotor symptoms because few studies reported outcomes separately for isolated symptoms. To account for differences in the severity of vasomotor symptoms reported, we distinguished between two groups of studies: those reporting any level of symptom, regardless of severity (reported as “any symptom”), and those reporting bothersome, or moderate to severe symptoms (reported as “bothersome symptoms”).To compare prevalence rates at various points in time across studies that reported vasomotor symptoms according to years to or from FMP2,21–25, we defined the FMP as our index time point. The number of years to or from FMP comprised the time scale.Four studies26–29 did not report symptoms according to years to or from FMP, but according to menopausal stage. We used criteria developed by the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW)(30) to standardize the definitions of menopausal stages: premenopause (regular menstrual cycles): S−3; early perimenopause (variable cycle length of >7 days different from normal): S−2; late perimenopause (variable cycle length of ≥2 skipped menstrual cycles and an interval of amenorrhea ≥60 days): S−1; early post-menopause (within 4 years of FMP): S1; late post-menopause (>4 years from FMP): S2. In two of these studies26,29 we only included data through perimenopause because the definitions for post-menopause were too broad (e.g., anytime >12 months since FMP).We excluded studies31–34 that reported menopausal symptoms using rating scales (e.g., Greene Climacteric Scale) because the scales measured symptom severity rather than symptom prevalence. Additionally, these scales used different units of measurement that could not be directly compared.

Analysis We pooled vasomotor symptom prevalence from each study at various time intervals in the menopausal transition using MOOSE guidelines for meta-analysis35. Our primary analyses were based on years to or from FMP, which allowed us to determine changes in symptom prevalence in 1-year intervals. Secondary analyses were based on menopausal stage according to STRAW criteria. We used Meta-Analyst36 to pool data based on the random effects model of DerSimonian and Laird37. We assessed for heterogeneity by calculating the Q-statistic for each independent time point and found none.The main analyses included studies that reported symptoms of any level of severity. Some studies also included prevalence points for ‘bothersome’ or ‘moderate to severe’ symptoms. We stratified analyses according to level of symptoms reported (‘any’ versus ‘bothersome’ symptoms) and graphed the pooled symptom prevalence at each point in time. We were not able to stratify results by study design (e.g., longitudinal vs. cross-sectional) or exclusion/inclusion of HT users because there were too few studies in each category.

Role of the Funding Source The AHRQ funded this study, but did not participate in data extraction, analysis, or interpretation of the data, synthesizing of the conclusions, or preparation of the manuscript.

RESULTS

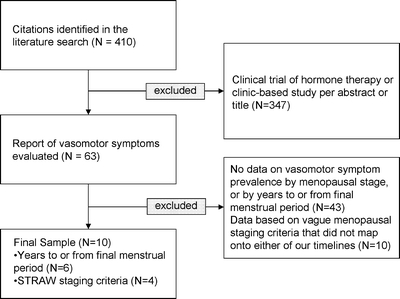

Study Characteristics A total of 410 studies were initially identified by our search strategy; data were formally extracted from 63 studies. Ten studies2,21–29 met inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Of these, six2,21–25 reported vasomotor symptoms by years to or from FMP, and four26–29 reported symptoms based on STRAW stages. Three2,26,27 were longitudinal, 721–25,28,29 were cross-sectional. One longitudinal study also included a cross-sectional survey26; only the cross-sectional survey was used in the meta-analysis because it provided more complete data on symptom prevalence according to menopausal stage. The studies included a total of 35,445 participants whose age ranged from 39–65 at study inception and up to age 75 at the end of study follow-up (Table 1). Only one study26 reported the ethnic or racial background of participants. Seven studies described the time interval for symptom reporting: four2,26,28,29 reported symptoms during the past 2 weeks, two21,27 reported vasomotor symptoms during the past year, and one22 reported symptoms in the previous month. Three2,22,26 reported symptoms based on level of severity. Based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale20, all studies scored highly on sample represenativeness, and both longitudinal studies scored highly on follow-up assessment (Appendix A). Few controlled for the use of HT, but almost all controlled for other biasing factors such as surgical menopause. All assessed vasomotor symptoms by self-report.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included in Meta-analysis

| Year | Country | N at Inception | Age at Study Start | Time Line Useda | Included HT Users? | Assessed Symptom Severity? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thompson23 | 1973 | UK | 269 | 40–60 | Years to/from FMP | Y | N |

| McKinlay21b | 1974 | UK | 638 | 45–54 | Years to/from FMP | Y | N |

| Berg24c | 1988 | Sweden | 1,469 | 60–62 | Years to/from FMP | Y | Y |

| Oldenhave22 | 1993 | The Netherlands | 5,213 | 39–60 | Years to/from FMP | Y | Y |

| Nedstrand25d | 1996 | Czech Republic | 799 | 55–65 | Years to/from FMP | Y (n = 1) | N |

| Guthrie2 | 2003 | Australia | 438 | 45–55 | Years to/from FMP | Y | Y |

| Groeneveld28 | 1996 | The Netherlands | 1,947 | 45–60 | STRAW staging | Not reported | N |

| Brown27 | 2002 | Australia | 8,466e | 45–50 | STRAW staging | N | N |

| Avis53 | 2005 | US | 16,065 | 40–55 | STRAW staging | N | Y |

| Melby29 | 2005 | Japan | 140 | 45–55 | STRAW staging | N | N |

aFMP = final menstrual period; STRAW = Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop

bSeparated hot flashes and night sweats; data on hot flashes is presented because it was more complete (with percentages and duration)

cCombines data from two studies of the same cohort

dReported percentages only; to calculate a total N for each year to/from final menstrual period, we assumed an equal distribution of the total sample for each menopausal group

eTotal N for our analyses based on e-mail correspondence with author and her statistician

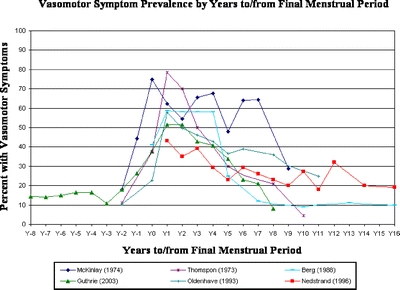

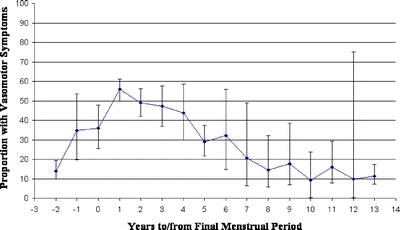

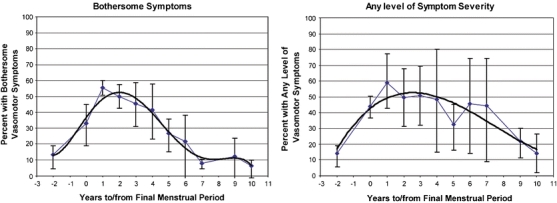

Vasomotor Symptom Prevalence The six individual studies that assessed vasomotor symptom prevalence by years to or from FMP were remarkably consistent with each other in the rise and fall of symptom prevalence according to years from FMP (Fig. 2), with the exception of one study21 that reported erratic peaks and troughs until 6–7 years after FMP. When all studies reporting vasomotor symptom prevalence according to years to or from FMP were combined, a temporal pattern emerged. The percentage of women experiencing symptoms began to increase in the years before menopause, peaked at approximately 1 year after FMP, and did not return to premenopausal levels until about 8 years after FMP (Fig. 3). Symptom prevalence fell to half of its peak prevalence only at 6.5 years after FMP. At 2 years before FMP, the earliest year for which we had more than one study reporting symptom prevalence, vasomotor symptom prevalence was 13.9% (95% CI 9.8–19.3%). At its peak, 1 year after FMP, it was 55.7% (95% CI 50.1–61.3%), dropping to 28.9% (95% CI 21.6%–37.4%) at 5 years after FMP. Symptom prevalence returned to baseline rates 8 years post FMP. Confidence intervals were broad beyond 5 years post FMP due to small sample sizes. When data were stratified according to symptom severity (‘any’ vs. ‘bothersome’; Fig. 4), bothersome symptoms peaked around 1–2 years after FMP, whereas the prevalence of any symptom peaked 2–3 years after FMP. Furthermore, while bothersome symptoms sharply declined 3–7 years after FMP, the presence of any symptom declined at a much slower rate.

Figure 2.

Vasomotor symptom prevalence by years to/from final menstrual period. Six studies [2,17–21] provided data for the main meta-analysis. One [2] was longitudinal, and the others were cross-sectional. The onset of menopause (Y0) coincides with the final menstrual period (FMP). One year after FMP corresponds to Y1, two years after, Y2, etc, whereas Y−1 represents 1 year before FMP.

Figure 3.

Pooled estimates of proportion of vasomotor symptoms by years to/from final menstrual period. Six studies [2,17–21] provided data for the main meta-analysis. One [2] was longitudinal, and the others were cross-sectional.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis stratified by symptom severity. Six studies [2,17–21] provided data for the main meta-analysis. One [2] was longitudinal, and the others were cross-sectional. The fitted trendlines (Fig. 4) were created to represent the pattern of vasomotor symptom prevalence over time, using a third order polynomial function.

Secondary Analyses Using STRAW Criteria Similar patterns emerged when data were pooled according to STRAW menopausal stage. Vasomotor symptom prevalence at premenopause (STRAW stage S−3) was 15.6% (95% CI 12.0–19.9%), similar to the premenopausal rate based on years to or from FMP. Vasomotor symptom prevalence peaked during early post-menopause (defined as up to 4 years after FMP), with a prevalence of 59.8% (95% CI 56.6–63.0%). However, prevalence rates never returned to baseline, with 43.9% (95% CI 34.2–54.1%) still reporting symptoms at late post-menopause, defined as more than 5 years after FMP (STRAW stage S2).

Analysis of Excluded Studies To explore for the presence of bias resulting from our inclusion criteria or definitions, we conducted separate analyses of the ten studies that were excluded1,38–46 because they reported symptom prevalence at time points that could not be mapped to either years to or from FMP or STRAW criteria (Appendix B). A scatter plot of these studies showed a trend consistent with those in the meta-analysis, although the exact timeline could not be determined. Vasomotor symptom prevalence peaked around menopause, declined post menopause, but never returned to premenopausal rates.

DISCUSSION

This creative method of sequentially pooling prevalence across studies provides comprehensive time series data that can accurately portray the natural history of vasomotor symptoms during the menopause transition. Among the women experiencing vasomotor symptoms, our data show a peak vasomotor symptom prevalence at 1 year after FMP, with 50% of women reporting symptoms after 4 years and 10% reporting symptoms as far as 12 years after FMP.

Our findings are consistent with other recent cohort studies that explored symptom prevalence. In one study of older postmenopausal women (mean age, 67 years), over 30% of women experienced vasomotor symptoms more than 3 years after FMP47. Another longitudinal study suggested that women began experiencing vasomotor symptoms approximately 2 years before FMP and that symptoms tended to last for a median of 4 years2. In that cohort, as many as 20% of women reported hot flashes for more than 5 years48.

If the duration of vasomotor symptoms is approximately 4 years, as our findings suggest, the clinical implications are substantial. A longer symptom duration may affect treatment decisions and clinical guidelines. The risks of diseases that are either induced or averted by HT, as well as the continuation of symptoms that can impact women’s quality of life with premature discontinuation of HT49, need to be carefully weighed in determining an individual’s risk:benefit profile from HT or non-hormonal treatments.

There are also implications for research examining vasomotor symptom duration. The studies that laid the foundation for the duration of vasomotor symptoms were not designed to measure symptom duration. Methodologically robust prospective, longitudinal studies that examine symptom duration are needed to better understand the natural history of menopause. Ideally, studies should begin observation before the onset of symptoms, continue until symptoms cease, and account for level of symptom severity and the use of symptom-modifying treatments. Prospective data acquisition is needed to minimize recall error. Moreover, research should also aim to identify risk factors for persistent vasomotor symptoms among menopausal women. Only one longitudinal, epidemiological study to date has investigated risk factors such as socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviors, and physical and psychological health on the presence of vasomotor symptoms26,50,51, and found that menopausal status was the most consistent predictor of the presence of symptoms.

Although the STRAW criteria have helped to standardize nomenclature around the menopause transition, its broad categorization of time intervals, especially for late postmenopause, makes it less useful in determining the duration of symptoms. Further refinement of later postmenopause, using smaller incremental time intervals, would help characterize the duration of menopausal symptoms.

Limitations Our findings should be interpreted with caution because of the difficulties in translating symptom prevalence data into estimates of symptom duration. Symptom prevalence data do not allow us to determine when individual women started experiencing symptoms or when their symptoms abated. Simulation techniques could be used to estimate duration from prevalence data, but such analyses are beyond the scope of the present paper.

Additionally, many of the studies were cross-sectional and may have been subject to sampling variability. Although we excluded studies that were clinic-based to minimize the selection of more symptomatic women (selection bias), longitudinal studies with longer periods of follow-up would provide better estimates of the time course for symptom onset, prevalence, and severity of vasomotor symptoms over time.

Our estimates should be interpreted cautiously because the studies included in our analyses artificially truncated symptoms due to limited follow-up periods; that is, symptoms may have begun before the study began and may have extended beyond the length of the study.

Differences in the minimum level of symptom severity among studies could result in an underestimation of symptom prevalence. However, while studies reporting only women who had moderate, severe, or bothersome symptoms had lower symptom prevalence rates than studies that reported women experiencing any level of symptom severity, the patterns observed were similar across all groups.

Some studies excluded women who were taking HT, which could introduce a selection bias that would underestimate both the duration and severity of symptoms, as HT users likely had more severe baseline symptoms and obtained symptom relief while on HT. We were not able to stratify our analyses according to HT use because there were not enough studies excluding HT users.

Differing selection and retention rates in the studies included in our analysis could have affected our results. Those who participated or remained in a study for longer periods of time might have experienced more severe or longer duration of symptoms. Nonetheless, temporal patterns observed across diverse studies were remarkably consistent, suggesting that this selection and retention bias was either consistent across all studies or relatively insignificant.

Although our analyses included studies conducted in multiple countries, it may not be generalizable to non-white women. Only one study26 in our analyses included ethnically diverse participants. There is some evidence to show that vasomotor symptom reporting differs across ethnic groups52. However, to our knowledge, there is no evidence to show that vasomotor symptom duration differs by ethnicity.

In conclusion, these results suggest that the vasomotor symptoms of menopause may last longer than 2 years, and for a median of about 4 years. The data should lead to reevaluating the course of treatment of menopausal symptoms given the risks and benefits of longer-term use of HT. Further prospective, longitudinal studies of menopausal symptoms that account for the presence of symptoms before and after the observation period, the use of symptom-modulating treatments, such as HT, symptom severity, and ethnicity should be conducted to confirm these results. Studies should also assess potential risk factors for persistent vasomotor symptoms and typical age of onset of these symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare, Research, and Quality (AHRQ) 2R01 HS013329-04A1. An earlier version was presented at the Society for Medical Decision Making Annual Meeting, October 2007. We would like to thank Nancy Avis, Ph.D. (Department of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC), Janet Guthrie, M.Sc., Dip. Ed, Ph.D. (Center for Women’s Health, University of Melbourne, Australia), and Martha Hickey, M.D. (School of Women’s and Infants’ Health, University of Western Australia, Australia) for their thoughtful reviews of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Appendix A

Quality assessment based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale

Table 2.

| Year | Represent-ative cohorta | Symptoms Present at inceptionb | Comparable (controls for HT, or other bias)c | Assessment of outcomed | F/U lengthe | Adequacy of F/Uf | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thompson23 | 1973 | Truly* | N/A | Surgical menopause* | Self-report | N/A | N/A |

| McKinlay21 | 1974 | Somewhat* | N/A | Surgical menopause* | Self-report | N/A | N/A |

| Berg24 | 1988 | Somewhat* | N/A | Reported but not controlled | Self-report | N/A | N/A |

| Oldenhave22 | 1993 | Somewhat* | N/A | Surgical menopause, contraceptives* | Self-report | N/A | N/A |

| Nedstrand25 | 1996 | Somewhat* | N/A | Reported but not controlled | Self-report | N/A | N/A |

| Guthrie2 | 2003 | Truly* | Controlled* | HT, surgical menopause** | Self-report | 8 years* | 88* |

| Groeneveld28 | 1996 | Truly* | N/A | HT, surgical menopause** | Self-report | N/A | N/A |

| Brown27 | 2002 | Somewhat* | Controlled* | Surgical menopause* | Self-report | 2 yrs* | 92* |

| Avis53 | 2005 | Truly* | N/A | HT, Surgical menopause** | Self-report | N/A | N/A |

| Melby29 | 2005 | Truly* | N/A | HT, Surgical menopause, contraceptives** | Self-report | N/A | N/A |

aTruly representative or somewhat representative = * rating

bOutcome of interest not present at start of study = * rating

cControls for HT = * rating; controls for HT AND other bias (e.g., excluding women who experienced surgical menopause) = ** rating

dIndependent blind assessment or record linkage = *

eLong enough follow-up for outcomes to occur = *

fAdequacy of follow-up rate = *

Appendix B

Characteristics of studies with vague menopausal staging criteria

Table 3.

| Year | N at inception | Years of follow-up | Starting age (years) | Definition of menopausal phases* | Measurement of vasomotor symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaufert | 1981 | 148 | N/A | mean 50 | Pre, peri/immediately post, advanced post | % with symptoms |

| McKinlay | 1992 | 2,570 | 5 | 44–55 | Pre, peri, T0, post | % with symptoms in past 2 weeks |

| Hunter | 1992 | 36 | 3 | 47+ | Pre, peri/post | % with symptoms |

| Bardel | 2002 | 2,991 | N/A | 35–64 | Pre, men, post | % with symptoms |

| Overlie | 2002 | 57 | 5 | 47–55 | Pre, <1 year post, 1–4 years post | % with symptoms |

| Keenan | 2003 | 2,602 | N/A | 45+ | Menstruating vs. not | % with symptoms |

| Juang | 2005 | 1,273 | N/A | 40–54 | Pre, peri, post | % with symptoms in past 2 weeks |

| Kumari | 2005 | 2,489 | N/A | Pre, peri, post | % with symptoms | |

| Miller | 2006 | 356 | N/A | 45–54 | Pre, peri | % with symptoms |

| Sievert | 2006 | 293 | N/A | 45–55 | Pre, peri, post | % with symptoms |

*Pre = premenopausal; peri = perimenopausal; T0 = final menstrual period; men = menopausal; post = postmenopausal

References

- 1.McKinlay SM, Brambilla DJ, Posner JG. The normal menopause transition. Maturitas. 1992;14(2):103–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Guthrie J, Dennerstein L, Taffe J, Donnelly V. Health care-seeking for menopausal problems. Climacteric. 2003;6(2):112–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lobo R (ed). Treatment of the postmenopausal woman: Basic and clinical aspects.: Academic Press; 2007.

- 4.Medical Knowledge Self Assessment Program 14. 2007.

- 5.North American Menopause Society. Treatment of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: Position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2004;11:11–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kronenberg F. Hot flashes: epidemiology and physiology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;592:52–86. discussion 123–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Col NF. The impact of risk status, preexisting morbidity, and polypharmacy on treatment decisions concerning menopausal symptoms. Am J Med. 2005;118(12 Suppl 2):155–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA. 2007;297(13):1465–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Women’s Health Initiative. Scientific Resources Website. Vol. 2006.

- 10.Grodstein F, Clarkson TB, Manson JE. Understanding the divergent data on postmenopausal hormone therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(7):645–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Executive Summary. Hormone Therapy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2004;104:1S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Mosca L, Collins P, Herrington DM, et al. Hormone Replacement Therapy and cardiovascular disease: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2001;104:499–503. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Grady D. Management of menopausal symptoms. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(22):2338–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.National Institute of Health. NIH State-of-the-Science conference on management of menopause-related symptoms. Vol. 2005; 2005.

- 15.Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Symptoms during the perimenopause: Prevalence, severity, trajectory, and significance in women’s lives. Am J Med. 2005;118(12B):14S–24S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Medical Women’s Federation. An investigation of the menopause in one thousand women. The Lancet. 1933:106–108.

- 17.Feldman BM, Voda A, Gronseth E. The prevalence of hot flash and associated variables among perimenopausal women. Res Nurs Health. 1985;8(3):261–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kronenberg F. Hot Flashes. New York: Raven Press, Ltd.; 1994:97.

- 19.Association for Healthcare Research and Quality. Evidence report/Technology assessment: Management of menopause-related symptoms. Vol. 2005; 2005.

- 20.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000.

- 21.McKinlay SM, Jefferys M. The menopausal syndrome. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1974;28(2):108–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Oldenhave A, Jaszmann LJ, Haspels AA, Everaerd WT. Impact of climacteric on well-being. A survey based on 5213 women 39 to 60 years old. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(3 Pt 1):772–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Thompson B, Hart SA, Durno D. Menopausal age and symptomatology in a general practice. J Biosoc Sci. 1973;5(1):71–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Berg G, Gottwall T, Hammar M, Lindgren R. Climacteric symptoms among women aged 60–62 in Linkoping, Sweden, in 1986. Maturitas. 1988;10(3):193–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Nedstrand E, Pertl J, Hammar M. Climacteric symptoms in a postmenopausal Czech population. Maturitas. 1996;23(1):85–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Avis NE, Brockwell S, Colvin A. A universal menopausal syndrome? Am J Med. 2005;118(12 Suppl 2):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Brown WJ, Mishra GD, Dobson A. Changes in physical symptoms during the menopause transition. Int J Behav Med. 2002;9(1):53–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Groenveld FPMJ, Bareman FP, Barentsen , Dokter HJ, Drogendijk AC, Hoes AW. Vasomotor symptoms and the well–being in the climacteric years. Maturitas. 1996;23:293–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Melby MK. Vasomotor symptom prevalence and language of menopause in Japan. Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society. 2005;12(3):250–7. [PubMed]

- 30.Soules M, Sherman S, Parrott E, et al. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW). Climacteric. 2001;4(4):267–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Genazzani A, Nicolucci A, Campagnoli C, et al. Validation of Italian version of the Women’s Health Questionnaire: Assessment of quality of life of women from the general population and those attending menopause centers. Climacteric. 2002;5:70–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Binfa L, Castelo-Branco C, Blumel JE, et al. Influence of psychosocial factors on climacteric symptoms. Maturitas. 2004;48:425–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Travers C, O’Neill SM, King , Battistutta D, Khoo SK. Greene Climacteric Scale: Norms in an Australian population in relation to age and menopausal status. Climacteric. 2005;8:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Ford K, Sowers MF, Crutchfield M, Wilson A, Jannausch M. A longitudinal study of the predictors of prevalence and severity of symptoms commonly associated with menopause. Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society. 2005;12(3):308–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–20012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Lau J. Metaanalyst. Boston, MA, US.

- 37.DerSimonian , Laird N. Meta-analysis in Clinical Trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Kaufert P, Syrotuik J. Symptom reporting at the menopause. Soc Sci Med. 1981;15(3):173–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Hunter M. The south-east England longitudinal study of the climacteric and postmenopause. Maturitas. 1992;14(2):117–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Bardel A, Wallander M-A, Svardsudd K. Hormone replacement therapy and symptom reporting in menopausal women. A population-based study of 35–65 year old women in mid-Sweden. Maturitas. 2002;41:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Overlie I, Finset A, Holte A. Gendered personality dispositions, hormone values, and hot flushes during and after menopause. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;23:219–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Keenan NL, Mark S, Fugh-Berman A, Browne D, Kaczmarczyk J, Hunter C. Severity of menopausal symptoms and use of both conventional and complementary/alternative therapies. Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society. 2003;10(6):507–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Juang KD, Wang SJ, Lu S, Lee SJ, Fuh JL. Hot flashes are associated with psychological symptoms of anxiety and depression in peri- and post- but not premenopausal women. Maturitas. 2005;52(2):119–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Kumari M, Stafford M, Marmot M. The menopausal transition was associated in a prospective study with decreased health functioning in women who report menopausal symptoms. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(7):719–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Miller S, Gallicchio LM, Lewis LM, et al. Association between race and hot flashes in midlife women. Maturitas. 2006;54:260–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Sievert LL, Obermeyer CM, Price K. Determinants of hot flashes and night sweats. Ann Hum Biol. 2006;33(1):4–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Huang AJ, Grady DG, Blackwell TL, Bauer DC, Sawaya GF. Persistent hot flashes in older postmenopausal women (abstract). J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(suppl 1):168. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Guthrie J, Dennerstein L, Taffe J, Lehert P, Burger HG. Hot flushes during the menopause transition: a longitudinal study in Australian-born women. Menopause. 2005;12(4):460–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Warren MP. Historical perspectives in postmenopausal hormone therapy: Defining the right dose and duration. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2007;82(2):219–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40–55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(5):463–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Avis NE, Crawford SL, McKinlay SM. Psychosocial, behavioral, and health factors related to menopause symptomatology. Womens Health. 1997;3(2):103–20. [PubMed]

- 52.Avis NE, Stellato , Crawford S, et al. Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic groups. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(3):345–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Avis NE, Zhao X, Johannes CB, Ory M, Brockwell S, Greendale GA. Correlates of sexual function among multi-ethnic middle-aged women: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause. 2005;12(4):385–98. [DOI] [PubMed]