Abstract

Background

Some primary care physicians do not conduct alcohol screening because they assume their patients do not want to discuss alcohol use.

Objectives

To assess whether (1) alcohol counseling can improve patient-perceived quality of primary care, and (2) higher quality of primary care is associated with subsequent decreased alcohol consumption.

Design

A prospective cohort study.

Subjects

Two hundred eighty-eight patients in an academic primary care practice who had unhealthy alcohol use.

Measurements

The primary outcome was quality of care received [measured with the communication, whole-person knowledge, and trust scales of the Primary Care Assessment Survey (PCAS)]. The secondary outcome was drinking risky amounts in the past 30 days (measured with the Timeline Followback method).

Results

Alcohol counseling was significantly associated with higher quality of primary care in the areas of communication (adjusted mean PCAS scale scores: 85 vs. 76) and whole-person knowledge (67 vs. 59). The quality of primary care was not associated with drinking risky amounts 6 months later.

Conclusions

Although quality of primary care may not necessarily affect drinking, brief counseling for unhealthy alcohol use may enhance the quality of primary care.

KEY WORDS: alcohol, counseling, brief intervention, quality of primary care

BACKGROUND

Practice guidelines recommend that clinicians screen and offer brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use (the spectrum from drinking at-risk amounts through dependence) in adults1,2. Despite these guidelines and available efficacious strategies, unhealthy alcohol use among primary care patients is often unrecognized3,4 and treated ineffectively5,6.

Many barriers to addressing unhealthy alcohol use exist, including the assumption held by some physicians that patients do not want to discuss drinking. Physicians who are concerned about alienating their patients or believe their patients lack interest in discussing alcohol use will either avoid raising the subject or may not address it adequately7,8. These doctors may also worry that alcohol counseling will diminish patient-perceived quality of care9.

Most patients, however, are not bothered by alcohol discussions and may welcome them10,11. They often find the discussions useful3 and are more likely to be satisfied with their care than are patients who do not have such discussions12.

Still, whether alcohol counseling is associated with higher quality of care remains unknown. Therefore, we conducted this study of patients with unhealthy alcohol use to determine whether alcohol counseling during a primary care visit influences patient-perceived quality of primary care. Further, we studied whether quality of care is associated with drinking of risky amounts.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were patients in an urban, academic primary care practice who had participated in a randomized trial testing the effects of providing physicians with patients’ alcohol screening results5. In that cluster randomized trial, physicians were randomly assigned to receive or not receive the results of alcohol screening that was done in the waiting room prior to the physician visit. Patients had unhealthy alcohol use and presented for a visit with the physician and were identified in the waiting room by screening. The intervention consisted of a sheet of paper summarizing the results of the CAGE test, recent drinking amounts, and readiness to change. Eligible subjects spoke English or Spanish, drank in the past month, and had either a ≥1 on the CAGE alcohol screening test13 or drank risky amounts (past 30 days; Table 1)14.

Table 1.

Characteristics at Enrollment: 288 Subjects with Unhealthy Alcohol Use

| Counseleda about drinking n = 132 | Not counseled about drinking n = 156 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, no. (%) | 87 (66) | 90 (58) | 0.15 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 45 (13) | 41 (13) | 0.009 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.74 | ||

| African American, no. (%) | 80 (61) | 85 (54) | |

| White, no. (%) | 22 (17) | 32 (21) | |

| Latino, no. (%) | 20 (15) | 25 (16) | |

| High school education, no. (%) | 64 (48) | 115 (74) | <0.001 |

| Medical comorbidity,b ever, no. (%) | 91 (69) | 107 (69) | 0.95 |

| Drinks per drinking day,c past 30 days, mean (SD) | 7 (5) | 5 (4) | 0.002 |

| Alcohol problems,d current, mean score (SD) | 11 (11) | 5 (9) | <0.001 |

| Drank risky amounts,e past 30 days, no. (%) | 108 (82) | 113 (72) | 0.06 |

| Readiness to change,f mean (SD) | 5.8 (3.0) | 4.9 (3.3) | 0.02 |

| Met physician previously, no. (%) | 96 (73) | 109 (70) | 0.59 |

| Wanted the physician they were seeing to provide general information about alcohol use, no. (%) | 78 (59) | 76 (49) | 0.08 |

| Wanted the physician they were seeing to give advice about their drinking habits,g no. (%) | 83 (63) | 82 (53) | 0.09 |

| Had a physician who was randomized to the intervention group in the randomized controlled trial, no. (%) | 72 (55) | 80 (51) | 0.58 |

| Had a physician who was faculty, no. (%) | 106 (80) | 116 (74) | 0.23 |

aBased on patient self-report

bDetermined with the method of Katz et al 16

cDetermined by the Timeline Followback method, which assesses the type and number of standard drinks consumed on each of the previous 30 days 19

dShort Inventory of Problems (SIP 2R) total score 20

e>14 standard drinks per week or >4 drinks per occasion for men; >7 drinks per week or >3 drinks per occasion for women and people ≥66 years 14

fBased on a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 10 15; n = 114 for counseled, 149 for not counseled

gn = 155 for not counseled

Enrolled subjects provided written informed consent and were compensated. The Institutional Review Board at Boston Medical Center approved this study.

Measurements

Research associates (RAs) screened patients waiting to see one of 40 primary care physicians, for eligibility through a self-administered questionnaire (there was no other basis for selection). RAs then interviewed enrolled subjects immediately before and immediately after the physician visits.

During the interview before the visit, RAs assessed readiness to change (visual analogue scale from 0 to 10)15 and medical comorbidity16. Immediately after the visit, RAs asked patients whether they had received alcohol counseling (a referral and/or advice on safe drinking limits, decreasing intake, or abstaining) during the visit and about quality of care based on three (of 11) scales from the Primary Care Assessment Survey (PCAS)17, a validated tool that measures the fundamental characteristics of primary care defined by the Institute of Medicine18. The scales, ranging from 0 to 100 with 100 indicating the highest level of performance, included communication (e.g., attention to what patients say); whole-person knowledge (e.g., physician’s knowledge of a patient’s health concerns, values, and beliefs); and trust (e.g., physicians’ integrity). Lastly, RAs evaluated subjects’ alcohol consumption (past 30 days, Timeline Followback method)19 and current alcohol problems [Short Inventory of Problems (SIP 2R)]20. Six months later, RAs interviewed subjects by telephone.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was patient-perceived primary care quality, measured with the three PCAS scales17 immediately after physician visits. The secondary outcome was drinking risky amounts at the 6-month follow-up.

Statistical Analyses

We performed all analyses using SAS software, version 8.1. (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). We used the chi-square test and t test, as appropriate, for bivariate comparisons. Reported P values are two-tailed; a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We used linear mixed effects models to test the association between alcohol counseling and the three PCAS scales and generalized estimating equations (GEE) logistic regression models to test the associations between the PCAS scales and drinking. These correlated data models were used to adjust for clustering of patients by physician (exchangeable working correlations 0.03 to 0.08 for PCAS scales). The mixed model used an exchangeable working covariance structure and the GEE model used an independence working correlation structure.

RESULTS

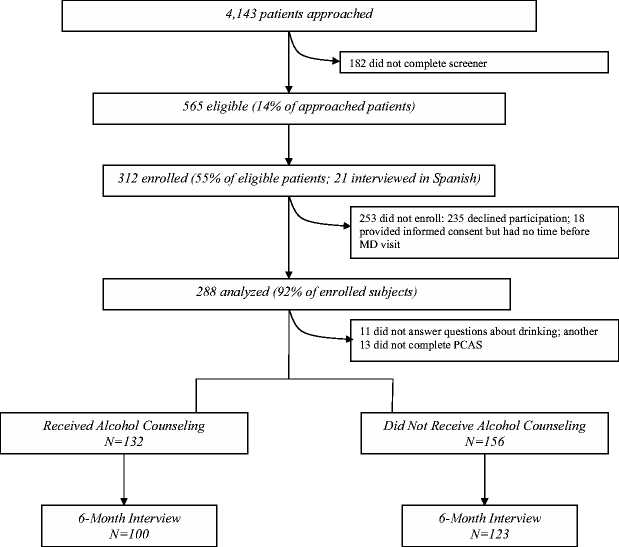

Of eligible patients, 55% enrolled (Fig. 1). Enrolled and eligible but not enrolled subjects were similar on age, sex, race, and CAGE questionnaire responses; however, enrolled subjects had significantly greater alcohol consumption (drinks/drinking day, 4.5 vs. 3.4) and readiness to change their drinking (mean score, 5.5 vs. 4.9).

Fig. 1.

Subject Enrollment and Follow-up.

Of the enrolled sample, 301 (96%) answered questions about alcohol counseling during their primary care visit; 288 (96%) of these completed the PCAS and compose our sample. At 6 months, 223 of the 288 (77%) were assessed. Compared to those lost to follow-up, interviewed subjects were significantly more likely to have a high school education (68% vs. 41%) and to have met their doctor before (74% vs. 60%).

Mean (SD) PCAS scores were communication 81 (SD 16), comprehensiveness 66 (SD 21), and trust 80 (SD 12). Almost half of the sample [132 (46%)] reported receiving alcohol counseling during their primary care visit. Counseled subjects were significantly more likely than subjects who had not been counseled to be older, have no high school education, and have a higher mean number of drinks/drinking day, alcohol problem score, and readiness to change (Table 1).

In unadjusted analyses, counseled subjects reported higher quality of primary care in the areas of communication, whole-person knowledge, and trust, though the latter was not statistically significant (Table 2). These findings persisted in multivariable analyses.

Table 2.

Alcohol Counseling and Quality of Primary Care

| Primary care quality domain | Unadjusted mean scoresa (95% CI) | Adjusted mean scoresb (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counseled n = 132 | Not counseled n = 156 | P value | Counseled n = 132 | Not counseled n = 156 | P value | |

| Communication | 85 (83–87) | 78 (75–80) | <0.001 | 85 (81–88) | 76 (73–79) | <0.001 |

| Whole-person knowledge | 70 (67–74) | 62 (59–65) | 0.001 | 67 (62–71) | 59 (55–63) | 0.005 |

| Trust | 81 (79–83) | 79 (77–80) | 0.08 | 79 (77–82) | 77 (74–79) | 0.06 |

aUnadjusted analyses account for clustering of patients by physician.

bAdjusted for sex, race, education, comorbidity, randomization, level of physician training, having met the physician previously, mean drinks per drinking day, alcohol problem score, and clustering of patients by physician

At 6 months, 121 of 223 subjects (54%) were drinking risky amounts. Quality of primary care did not significantly affect the odds of drinking risky amounts [adjusted odds ratios, 1.0 (95% CI, 0.98–1.02) for communication; 1.00 (95% CI, 0.98–1.01) for whole-person knowledge; and 1.00 (95% CI, 0.98–1.03) for trust].

CONCLUSION

Alcohol counseling by primary care physicians was associated with higher patient-perceived quality of care, specifically better communication, and whole-person knowledge. Higher quality of care, however, was not associated with decreased drinking of risky amounts at 6 months.

This study is novel as it assesses the relationships between (1) alcohol counseling and quality of primary care with a validated measure and (2) quality of primary care and drinking outcomes. Our study supports results from previous research indicating that patients are not bothered by, and often appreciate, being asked during primary care visits about their alcohol use3,10–12. The magnitude of differences in quality we observed was similar to, though generally smaller than, those known to impact clinical outcomes17,21. For example, Kim et al reported that single standard deviation increases in primary care quality were associated with a lower risk of subsequent substance use21. While various studies have reported a link between primary care quality and health outcomes9,21, ours did not. High-quality primary care may be necessary, but not sufficient, to help patients reduce their drinking. The lack of association between quality of primary care and decreased consumption is most likely because specific elements of brief interventions that are essential to change drinking (e.g., targeted advice) were not offered in this study.

Our study has several strengths. We used a standard measure of drinking in a sample with a range of unhealthy alcohol use and a well-validated measure of primary care quality that has been linked to clinical outcomes. The PCAS and its individual subscales have high internal consistency and reliability; each subscale has been validated17. Lastly, we used a prospective design and assessed counseling and quality immediately after a primary care visit.

Several limitations should be considered. First, we could not determine whether alcohol counseling affects quality beyond the self-report measures assessed. However, the measures we chose are among the best ways to assess primary care quality and are particularly relevant to alcohol counseling17. Second, we assessed the drinking outcome at only one timepoint. This method is similar to that used in studies supporting brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use2. Third, because this was an observational study, our ability to determine causality is limited; however, we did adjust analyses for potential confounding factors. Fourth, the initial research assessment may have sensitized subjects and influenced their responses to questions about perceived quality. Fifth, most subjects had visited their physicians and discussed alcohol previously. Therefore, the observed associations between counseling and quality of care may be biased towards the null; nonetheless, we observed some effects. Sixth, intervening influences (e.g., participation in Alcoholics Anonymous) could have affected drinking outcomes. Brief counseling, however, is known to reduce consumption beyond such influences. Lastly, the differences between the enrolled and nonenrolled patients limited generalizability and, along with the differences in those followed and lost to follow-up, may have biased analyses (the latter limited to the drinking analyses). However, the direction of bias resulting from these differences is difficult to predict.

Physicians should conduct alcohol counseling for unhealthy alcohol use for many reasons. Alcohol counseling has proven efficacy in outpatient settings and is recommended in practice guidelines. Furthermore, most patients want to receive advice about their drinking, and as indicated by this study, such a discussion does not diminish quality of care. These findings provide evidence that screening and intervention for unhealthy alcohol use may improve quality of care from the patient’s perspective.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are indebted to Rosanne T. Guerriero, MPH, for her efforts in manuscript writing and editing. This study was funded by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant 031489). Dr. Samet received support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K24-AA015674).

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Footnotes

Results of this study were presented at the following meetings: the annual national meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, Chicago, May 2004 and the annual national meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, Vancouver, Canada, June 2004. This study was funded by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant 031489). Dr. Samet received support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K24-AA015674).

References

- 1.Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):596–607. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):554–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Aalto M, Seppa K. Usefulness, length and content of alcohol-related discussions in primary health care: the exit poll survey. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(6):532–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bradley KA, Curry SJ, Koepsell TD, Larson EB. Primary and secondary prevention of alcohol problems: US internist attitudes and practices. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(2):67–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Saitz R, Horton NJ, Sullivan LM, Moskowitz MA, Samet JH. Addressing alcohol problems in primary care: a cluster randomized, controlled trial of a systems intervention. The screening and intervention in primary care (SIP) study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):372–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.McGlynn E, Asch S, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Friedmann PD, McCullough D, Chin MH, Saitz R. Screening and intervention for alcohol problems: a national survey of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Beich A, Gannik D, Malterud K. Screening and brief intervention for excessive alcohol use: qualitative interview study of the experiences of general practitioners. BMJ. 2002;325(7369):870–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(3):213–20. [PubMed]

- 10.Aalto M, Pekuri P, Seppa K. Primary health care professionals’ activity in intervening in patients’ alcohol drinking: a patient perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66(1):39–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zimmerman M, Farber NJ, Hartung J, Lush DT, Kuzma MA. Screening for psychiatric disorders in medical patients: a feasibility and patient acceptance study. Med Care. 1994;32(6):603–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Steven ID, Thomas SA, Eckerman E, Browning C, Dickens E. The provision of preventive care by general practitioners measured by patient completed questionnaires. J Qual Clin Pract. 1999;19(4):195–201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(10):1121–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Saunders JB, Lee NK. Hazardous alcohol use: its delineation as a subthreshold disorder, and approaches to its diagnosis and management. Compr Psychiatry. 2000;41(2 Suppl 1):95–103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Rollnick S, Heather N, Gold , Hall W. Development of a short ‘readiness to change’ questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers. Br J Addict. 1992;87(5):743–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34(1):73–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov A, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36(5):728–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Institute of Medicine. Primary care: America's health in a new era. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1996.

- 19.Sobell LC, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42(1):49–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Miller W, Tonigan J, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC). An Instrument for Assessing Adverse Consequences of Alcohol Abuse. Test Manual. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995.

- 21.Kim TW, Samet JH, Cheng DM, Winter M, Safran DG, Saitz R. Primary care quality and addiction severity: a prospective cohort study. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):755–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]