Abstract

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis that can be progressive and fatal, and its initial presenting symptom may be leg claudication due to peripheral vascular ischemia. To date, there have been fewer than ten case reports of polyarteritis nodosa presenting as peripheral vascular disease. We report a case of a 38-year-old man initially diagnosed to have premature peripheral vascular disease who presented 1 year later with symptoms consistent with giant cell arteritis and subsequently developed bowel ischemia leading to a fatal outcome. Based on the autopsy and the patient’s clinical course, the final diagnosis was polyarteritis nodosa. This case illustrates the challenges in diagnosing polyarteritis nodosa and the importance of considering vasculitis in young patients presenting with atypical presentations of diseases such as peripheral vascular disease or giant cell arteritis.

KEY WORDS: polyarteritis nodosa, temporal arteritis, premature peripheral vascular disease

INTRODUCTION

Premature peripheral vascular disease (PVD) <60 years of age is an uncommon entity with an unknown etiology. It has been thought to be related to an accelerated atherosclerotic process in patients with family history and risk factors such as smoking, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, renal disease, diabetes and hypercoagulable states. Of them, family history was found to be a major determinant of peripheral atherosclerotic disease, and a high lipoprotein (a) level (>30 mg/dl) was considered an independent major predictor of premature peripheral vascular disease. PVD carries a high morbidity and mortality because of its association with coronary artery disease. However, in young patients without significant family or past medical history who present with severe peripheral artery disease, a vasculitic process should be considered. We report a case of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) with an initial presentation of peripheral vascular disease and later symptoms mimicking giant cell arteritis (GCA). From the literature review, fewer than ten cases have been published of PAN presenting as peripheral vascular disease. Even though PAN is a vasculitis that typically affects small- and middle-sized arteries of almost any organ, there have been reported cases of PAN affecting medium- and large-sized arteries such as the temporal arteries. This case report describes the challenges in diagnosing polyarteritis nodosa, reports its clinical similarity to temporal arteritis, and highlights the importance of a holistic approach when encountering patients with premature peripheral vascular disease.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 38-year-old African-American male presented with 1-week history of subjective fever, chills, left temporal headache, left jaw claudication, and a brief episode of right eye visual loss. He was in his usual health until 1 week prior to the presentation when he noticed a skin rash on his ankles. The rash spread to his hips, but resolved spontaneously after 2 days. At the same time, he developed a left temporal throbbing headache associated with fever and chills and experienced left jaw pain with eating. Two days prior while working, he suddenly lost vision in his right eye, but regained it after a few minutes. On review of systems, he reported having abdominal pain after meals and 10 pounds of unintentional weight loss in the past 1 year. His past medical and surgical history included an aorto-bifemoral bypass 1 year prior due to severe bilateral femoral artery stenosis at an outside hospital. His LDL cholesterol at that time was 150 mg/dl. He had no family history of vascular disease or dyslipidemia. He was not taking any medications and denied any heavy alcohol use or the use of cocaine or intravenous drugs, but had a 10-pack-year tobacco history. He admitted to smoking cannabis weekly since the age of 20. His femoral artery stenosis was initially attributed to premature peripheral vascular disease due to tobacco and hyperlipidemia.

During this admission, he was noted to have a blood pressure of 148/76 mmHg, a temperature of 97.6°F, heart rate of 64/min, and respiratory rate of 16/min. Head and neck exam revealed severe right temple tenderness with a clearly prominent right temporal artery. Visual acuity was 20/20, and fundoscopic exam was unremarkable. Cardiovascular exam was remarkable for left carotid, right renal, and bilateral femoral bruits. Lungs were clear, and abdominal exam was non-tender and soft. His calves were tender to touch. No skin rash was noted. Laboratory studies revealed the following: hemoglobin 12.6 g/dl, WBC 10,500/ul with 84% neutrophils, ESR 61 mm/h (0–15), CRP 15.8 mg/dl (0–1), ANA 1:40 speckled, C3 42 mg/dl (79–152), C4 2 mg/dl (16–38), creatinine 1 mg/dl, BUN 8 mg/dl, and CPK 1,521 u/l (40–250). Liver function test revealed total protein 8 g/dl, albumin 3.8 g/dl, AST 46 U/l, ALT 25 U/l, alkaline phosphatase 60 U/l, total bilirubin 0.3 mg/dl, and direct bilirubin 0.1 mg/dl. Hepatitis panel, including acute and chronic serologies for hepatitis A, B, and C, was negative. Urine toxicology screen was negative for cocaine. Rheumatoid factor and HIV were negative. A perinuclear anti-neutrophil cystoplasmic antibody (P-ANCA) was not obtained.

The patient was immediately started on intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone 125 mg every 6 h. A right temporal artery biopsy was performed showing mild chronic lymphocytic inflammation of the intima, adventitia, and muscularis. There was splitting, degeneration, and focal effacement of the internal elastic lamina; however, no giant cells, microaneurysms, eosinophilic infiltrate, or fibrinoid necrosis were identified (Fig. 1). Due to his abdominal bruits and symptoms of possible mesenteric angina, a MRA/MRI of the abdomen was obtained revealing significant stenoses of the celiac ostium, mid supra-mesenteric, infra-mesenteric, and the right renal arteries. With the presence of severe headache and the left carotid bruit, a cerebral and carotid angiography was pursued showing mild stenosis of the supraclinoid left carotid artery with areas of narrowing and dilatation with a diffuse irregular pattern. There was bilateral 70–80% stenosis of the main branches of both the middle and anterior cerebral artery (Fig. 2). An electromyography of both lower limbs was performed to evaluate for an elevated CPK and calf tenderness found on exam, and findings were consistent with polymyositis. After 6 days of IV methylprednisolone, the patient responded well with almost complete resolution of his symptoms. Intravenous methylprednisolone was then discontinued, and oral prednisone 60 mg PO daily was prescribed. His ESR, CRP, and CPK decreased to 21 mm/h, 0.8 mg/dl, and 507 U/l, respectively. With the diagnosis of vasculitis of an unknown type, he was discharged home on oral prednisone taper from 60 mg to 20 mg daily over a 6-week period.

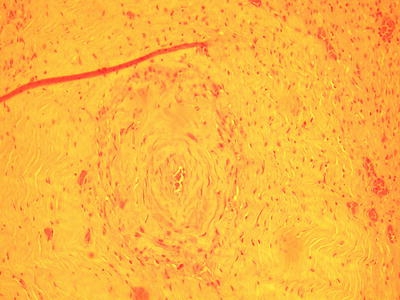

Figure 1.

Right temporal artery biopsy showing mild chronic lymphocytic inflammation of the intima, adventitia, and muscularis. No giant cells, microaneurysms, eosinophilic infiltrate, or fibrinoid necrosis are noted.

Figure 2.

Left carotid magnetic resonance angiography showing 80% stenosis of the M1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery (asterisk) and 70% stenosis of the A1 segment connecting the left middle cerebral artery with the anterior circulation (arrow).

The patient was compliant with his medications, and at a 4-week clinic follow-up, he was asymptomatic. A month later, he complained of recurrent headache, fever, chills, and general malaise with intense abdominal pain. He was readmitted with a systolic blood pressure of 230 mmHg and acute renal failure with a creatinine of 2.3 mg/dl. He also was found to have severe cardiomyopathy with an ejection fraction of 20–25% with worsening of his previous intracranial and intraabdominal stenoses found by repeat MRAs. At this point, the patient was started on IV cyclophosphamide 1.5 mg/kg daily and IV methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg daily. Unfortunately, the patient did not respond to therapy and developed mesenteric ischemia with evolution into sepsis and cardiac arrest on the 7th hospital day.

On autopsy, there were healed and healing vasculitis of large- and medium-size arteries, including multiple intracranial cerebral arteries, bilateral internal carotids, coronary arteries, descending aorta, and celiac, superior mesenteric, bilateral renal, and iliac arteries. No giant cells or active vasculitis was found, although fibrin thrombosis was seen in a few vessels. The small vessels, veins, and pulmonary vasculature were spared. There was small and large bowel necrosis, consistent with acute ischemic enterocolitis.

Given the histopathologic autopsy findings of vasculitis involving large and medium arteries, but sparing pulmonary vasculature, combined with his clinical presentation of mesenteric arteritis, myositis, and hypertensive urgency with renal involvement, the diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa was established.

DISCUSSION

Premature peripheral vascular disease (PVD) <60 years of age is found in 2.1% of the population of this age.1 The early onset of PVD is presumed to be an accelerated atherosclerotic process. The etiology is not well known, but family history and a high lipoprotein (a) level (>30 mg/dl) have been considered to be the predisposing factors. The clinical presentation includes signs and symptoms of limb ischemia, ranging from early skin changes, such as alopecia, to advanced ischemia and dry gangrene. Premature peripheral vascular disease can lead to silent coronary artery disease and death.1–5 Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a necrotizing vasculitis involving medium and small arteries of almost any organ sparing the lungs and the venous system. It is a rare disease that can be progressively fatal, with an incidence of 14 to 30.7 per million, predominantly affecting middle-aged men in a 1.5:1 ratio.6 Although of an unknown etiology, approximately 30–40% cases have been related with hepatitis B virus infection.6–8 Patients usually present with symptoms of tissue ischemia, affecting almost any organ except the lungs. Systemic symptoms, neuropathy, arthralgias, myalgias, orchitis, and cutaneous involvement are common findings.9 To date, there have been fewer than ten case reports of PAN presenting as peripheral vascular disease.10–12 There is no reference standard test to diagnose PAN, but the classic histopathology shows segmental transmural inflammation of muscular arteries with an eosinophilic infiltration called fibrinoid necrosis.13 While the differential diagnosis of PAN is broad, the autoimmune diseases that can resemble PAN include Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg Strauss syndrome, microscopic polyangiitis, giant cell arteritis, and vasculitis secondary to diseases such as lupus.14,15 We found at least 20 case reports of PAN affecting temporal arteries in a similar fashion to giant cell arteritis (GCA).16–19 However, both diseases differ mainly by their histopathology and vessel involvement. In contrast to the fibrinoid necrosis found in PAN, the classic GCA findings are infiltrates of T lymphocytes and macrophages with multinucleated giant cells, occasional plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils. In up to 50% of the patients with GCA, the biopsy may not reveal giant cells or the classic histological findings. Hence, the reported sensitivity is 88% with a negative predictive value of approximately 91%.20 In regards to the vessel involvement, PAN is usually a multisystemic disease affecting small- and medium-sized vessels, while GCA is more frequently limited to the thoracic aorta and main branches.21 Similarly to GCA, PAN laboratory tests can show elevation of sedimentation rate and C reactive protein. P-ANCA is often obtained as part of the workup for PAN, but it is not diagnostic since its sensitivity and specificity are not well studied.22 Imaging studies in PAN include evaluation of vasculature with MRA/MRI and/or angiographies showing tortuous patterns and microaneurysms.23 Based on the American College of Rheumatology 1990 classification criteria (Table 1), the presence of any three or more criteria yields a sensitivity of 82.2% and a specificity of 86.6%.24 Our patient met at least five of those criteria.

Table 1.

American College Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for PAN

| PAN criteria |

|---|

| - Weight loss of at least 4 kg |

| - Livedo reticularis |

| - Testicular pain or tenderness |

| - Myalgias, weakness, or leg tenderness |

| - Mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy |

| - Diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg |

| - Elevated BUN or creatinine |

| - Hepatitis B virus |

| - Arteriographic abnormality |

| - Biopsy of small- or medium-sized artery containing polymorphonuclears |

*The presence of any three or more criteria yields a sensitivity of 82.2% and a specificity of 86.6%

Without treatment, the 3-month survival of PAN is 50%; the majority is a result of renal failure with a 5-year survival of 13%. With optimal therapy, the 5-year survival is approximately 80%.25 Currently, the recommended treatment is prednisone 1 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks with subsequent taper over 9 months. This approach achieves remission in 50% of cases, and the rest requires the addition of oral cyclophosphamide at 1.5 to 2 mg/kg per day for 1 year. The addition of plasma exchange has not been proven to increase remission of disease.26 On the other hand, there is a better outcome with antiviral therapy for those patients carrying active hepatitis B infections.26–29

In summary, we report the case of a 38-year-old male who had been diagnosed with bilateral femoral artery stenosis 1 year prior to presenting with symptoms consistent with diffuse vascular involvement and vasculitis. He eventually developed bowel ischemia and succumbed despite optimal therapy with cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Retrospectively, although the patient had a smoking history and a mildly elevated LDL cholesterol, his initial presentation of severe peripheral vascular disease at an early age and the symptom of post-prandial angina should have alerted the clinicians to pursue other possible etiology, such as vasculitis. This case report thus underscores the importance of broadening our differential diagnosis when a common disease presents with unusual features and illustrates the salience of rehearsing our clinical judgment and adopting a holistic approach to match the clinical course of our patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Alan W. Friedman, Medical Clinics of Houston, for his support and guidance in this article.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Lane JS, et al. Risk factors for premature peripheral vascular disease: results for the National Health and Nutritional Survey, 1999–2002. J Vasc Surg. 2006;442319–24. 2006;44(2):319–24; discussion 324–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Valentine RJ, et al. Family history is a major determinant of subclinical peripheral arterial disease in young adults. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(2):351–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Valentine RJ, et al. The progressive nature of peripheral arterial disease in young adults: a prospective analysis of white men referred to a vascular surgery service. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(3):436–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Valentine RJ, et al. Lipoprotein (a), homocysteine, and hypercoagulable states in young men with premature peripheral atherosclerosis: a prospective, controlled analysis. J Vasc Surg. 1996;23(1):53–61, discussion 61–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Valentine RJ, et al. Premature cardiovascular disease is common in relatives of patients with premature peripheral atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(9):1343–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Watts RA, et al. Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis: a ten-year study in the United Kingdom. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(2):414–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Mohammad AJ, et al. Prevalence of Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa and Churg Strauss syndrome within a defined population in southern Sweden. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(8):1329–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Watts RA, et al. Geoepidemiology of systemic vasculitis: comparison of the incidence in two regions of Europe. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(2):170–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Colmegna I, Maldonado-Cocco JA. Polyarteritis nodosa revisited. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7(4):288–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Fred HL, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Polyarteritis nodosa inducing symmetric peripheral gangrene. Circulation. 2003;107(22):2870. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Ninomiya T, et al. Symmetric peripheral gangrene as an emerging manifestation of polyarteritis nodosa. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(2):440–1. [PubMed]

- 12.Heron E, Fiessinger JN, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis nodosa presenting as acute leg ischemia. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(6):1344–6. [PubMed]

- 13.Jennette JC, Falk RJ. The role of pathology in the diagnosis of systemic vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(1 Suppl 44):S52–6. [PubMed]

- 14.Fries JF, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of vasculitis. Summary. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1135–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hunder GG, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of vasculitis. Introduction. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1065–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Haugeberg G, Bie R, Johnsen V. Vasculitic changes in the temporal artery in polyarteritis nodosa. Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26(5):383–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Hamidou MA, et al. Temporal arteritis associated with systemic necrotizing vasculitis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(10):2165–9. [PubMed]

- 18.Jawad AS. Temporal arteritis associated with systemic necrotizing vasculitis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(6):1173; author reply 1173. [PubMed]

- 19.Liozon E, et al. Disease associations in 250 patients with temporal (giant cell) arteritis. Presse Med. 2004;33(19 Pt 1):1304–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Myklebust G, Gran JT. A prospective study of 287 patients with polymyalgia rheumatica and temporal arteritis: clinical and laboratory manifestations at onset of disease and at the time of diagnosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(11):1161–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lie JT. Aortic and extracranial large vessel giant cell arteritis: a review of 72 cases with histopathologic documentation. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1995;24(6):422–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Puszczewicz M, et al. Prevalence and specificity of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) in connective tissue diseases. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2003;109(1):35–41. [PubMed]

- 23.Schmidt WA, Both M, Reinhold-Keller E. Imaging procedures in rheumatology: imaging in vasculitis. Z Rheumatol. 2006;65(7):652–6, 658–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Lightfoot RW Jr., et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1088–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Gayraud M, et al. Long-term followup of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome: analysis of four prospective trials including 278 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(3):666–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Guillevin L, et al. Corticosteroids plus pulse cyclophosphamide and plasma exchanges versus corticosteroids plus pulse cyclophosphamide alone in the treatment of polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome patients with factors predicting poor prognosis. A prospective, randomized trial in sixty-two patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(11):1638–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Guillevin L, et al. Treatment of polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome. A meta-analysis of 3 prospective controlled trials including 182 patients over 12 years. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1992;143(6):405–16. [PubMed]

- 28.Guillevin L, et al. Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome. A prospective study in 342 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75(1):17–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Guillevin L, et al. Treatment of polyarteritis nodosa and microscopic polyangiitis with poor prognosis factors: a prospective trial comparing glucocorticoids and six or twelve cyclophosphamide pulses in sixty-five patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(1):93–100. [DOI] [PubMed]