ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Minor depression is almost twice as common in primary care (PC) as major depression. Despite the high prevalence, few evidence-based algorithms exist for managing patients with minor depression or patients presenting solely with distress.

OBJECTIVES

The aim of this study was to test the effectiveness of a telephone-based close monitoring program to manage PC patients with minor depression or distress.

DESIGN

Subjects were randomly assigned to either the control arm (usual care; UC) or the intervention arm (close monitoring; CM). We hypothesized that those randomized to CM would exhibit less depression and be less likely to have symptoms progress to the point of meeting diagnostic criteria.

SUBJECTS

Overall, 223 PC subjects with minor depression or distress consented to participation in this trial.

MEASUREMENTS

At baseline, subjects completed a telephone-based evaluation comprised of validated diagnostic assessments of depression and other MH disorders. Outcomes were assessed at six months utilizing this same battery. Chart reviews were conducted to track care received, such as prescribed antidepressants and MH and primary care visits.

RESULTS

Subjects in the CM arm exhibited fewer psychiatric diagnoses than those in the UC arm (χ2 = 4.04, 1 df, = 0.04). In addition, the intervention group showed improved overall physical health (SF-12 PCS scores) (M = 45.1, SD = 11.8 versus M = 41.5, SD = 12.4) (χ2 = 5.90, 1 df, = .02).

CONCLUSIONS

Those randomized to CM exhibited less MH problems at the conclusion of the trial, indicating that the close monitoring program is effective, feasible and valuable. The findings of this study will allow us to enhance clinical care and support the integration of mental health services and primary care.

KEY WORDS: minor depression, close monitoring, telephone care management

INTRODUCTION

While major depression has been widely researched, leading to the establishment of clear treatment guidelines, there has been less consistent research on the treatment of minor and subsyndromal forms of depression. Minor and subsyndromal depression are almost twice as common in primary care (PC) as major depression,1–3 leading to greater health care utilization4 and increased dysfunction and disability,5–7 and putting patients at risk for the development of major depressive disorder.8 Although findings on the morbidity associated with low levels of depression4,5,9,10 suggest the potential value of treatment, no evidence-based guidelines have been established11. Thus, when PC clinicians encounter patients with depression or distress, they perceive themselves as forced to make a series of binary choices, such as whether or not to prescribe antidepressants or make an MH referral. Moreover, given stringent time demands and limited resources, they often perceive themselves as having to make these choices on the basis of inadequate information.11

The challenge facing PC clinicians is made even more difficult by a lack of evidence about the optimal approach to treating patients with milder forms of depression. While some trials have shown pharmacotherapy to be efficacious for improving depressive symptoms,12,13 others have shown no significant differences between response to placebo and active treatment.4 Psychotherapy interventions implemented in primary care, such as problem solving therapy, have received uneven support with substantial variability among studies.13,14

These potentially conflicting findings have led to recommendations for a period of close monitoring (CM) before treatment of minor depression, with the initiation of treatment reserved for individuals who have persistent and/or disabling symptoms. Such a period would avoid exposure to potential side effects and risks of active treatment for patients whose symptoms would remit spontaneously. However, recommendations for close monitoring have been primarily post hoc suggestions, offered in discussions of findings from randomized clinical trials.13 There has been essentially no research designed specifically to evaluate the impact of a period of prospective CM on patients’ depression care.

In response to this inadequacy of knowledge and lack of treatment options, we developed a telephone-based CM and depression care management program as a mechanism for determining which primary care patients with minor depression or distress require and are most likely to respond to specific MH treatments. Previous research, such as the Telephone Disease Management for Depression and At-Risk Drinking15 and the Translating Initiatives for Depression into Effective Solutions16 studies, have demonstrated that telephone-based disease management modules can effectively manage patients with major depression in PC settings. Telephone-based methods have also exhibited success in the clinical setting; the Behavioral Health Laboratory, for example, has proven to be an effective service in the screening, assessment and management of depression for PC patients.17

To test the effectiveness, feasibility, and value of the CM program, we conducted a randomized controlled trial, where subjects were randomly assigned to either the control arm (usual care) or the treatment arm (close monitoring). We hypothesized that those randomized to CM would exhibit less depression and be less likely to have symptoms progress to the point of meeting diagnostic criteria. In testing the CM program, we also intended to improve the specificity for identifying individuals who require treatment for depression.

METHODS

Location

This study was conducted within the Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center at the Philadelphia VA Medical Center (PVAMC) in collaboration with the clinicians from the primary care clinics at PVAMC and its associated community-based outpatient clinics.

Subject Recruitment

Recruitment was conducted through the Behavioral Health Laboratory (BHL). In the VA health care system, patients are screened annually for depression, alcohol misuse and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by their PC clinicians. At the PVAMC, PC clinicians can refer patients with positive screens to the BHL for further evaluation. The BHL is a clinical service for PC that conducts structured assessments, where various domains of symptomology are evaluated to determine clinical status and diagnoses. While the procedures of the BHL are discussed in further detail in prior sources,17,18 we will provide a summary. The BHL staff contacts all patients referred. All older patients are assessed for cognitive deficits using the blessed memory test.19 For those with severe impairment, the full interview is not completed and the PC clinician is notified. The remainder of the measures included are the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) for depression;20 the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview21 modules for mania, psychosis, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), PTSD, and alcohol abuse/dependence; current antidepressant medications; measure of alcohol use using a 7-day timeline follow-back method;22 past and current illicit drug use; the five-item Paykel scale for suicide ideation;23 history of significant episodes of depression; and the Medical Outcomes Study (SF-12).24

Case Identification

Subjects were identified as eligible for the study based on a clinical concern generated by the PC clinician and on the results of the BHL assessment. Subjects were eligible for inclusion if they were referred by their PCC for a behavioral health concern and did not meet for any exclusion criteria. This case finding method generated a group of PC patients with PHQ scores ranging from 0–16 without a diagnosis of major depression or other severe axis 1 disorders. Given the PC clinicians’ clinical concerns and the need to develop interventions with practical utility, we focused the intervention on this broader group rather than the narrowly defined group with minor depression. We consider the study group to include subjects with minor depression (those with 2, 3,or 4 DSM depression criteria) and those with distress or depressive symptoms not meeting minor depression criteria.

Subjects were excluded if they had current PTSD, panic disorder, alcohol dependence, suicidal ideation, illicit drug use (past year), or if they had a history of or current bipolar or psychotic disorder. Subjects were also excluded if they were being followed by a MH clinician or if they were currently taking any antidepressants benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, addiction medications, or mood stabilizers. Of note, having a history of major depression or having been in past treatment for depression were not exclusions to participation. The decision to focus on current symptoms rather than having a lifetime disorder was to mimic clinical practice in which a complete diagnostic evaluation may not be practical. Thus, the design emphasizes generalizability at the expense of specificity.

Consent

Eligible subjects were orally consented by the BHL staff. Due to the low risk nature of this project, waivers of written consent and HIPAA authorization were granted from the PVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Randomization

Consented clinicians were randomly assigned to either usual care (UC) or close monitoring (CM). Randomization was stratified by clinic. The unit of analysis was patient with adjustment for clustering by physician, following previous precedents in the literature.25 This design decision reduced the probability of clinicians changing their practice in the UC arm based on experience with patients assigned to the intervention.

Usual Care

All subjects were assessed by the BHL. The PC clinicians in both arms were given a report of the BHL assessment with suggestions for ongoing monitoring of depressive symptoms and had the option to request referral of patients to a mental health clinic (MHC). In addition, each subject received a letter following their initial assessment that included self-help advice for any significant depression symptoms and encouragement to discuss his or her symptoms with their PC clinician. Significant depression symptoms were defined as any PHQ-9 symptom that the subject reported having either “More Than Half the Days” or “Nearly Every Day.”

Close Monitoring

In the CM arm, the baseline clinical assessment was completed in the same manner as the UC arm. Additionally, these subjects had weekly phone calls for up to 8 weeks to monitor symptoms of depression with the use of the PHQ-9. These weekly calls were conducted by a health technician, taking less than 10 minutes to administer. At each contact, subjects were also asked if they were currently interested in receiving treatment for their depressive symptoms. During this monitoring period, any subjects who indicated they wanted to receive treatment were referred to a behavioral health specialist (BHS) for telephone-based depression care management (TDCM). Subjects were also referred to the BHS based on persistent or worsening depressive symptoms, as defined by the following: two consecutive PHQ scores >9 and meeting criteria for major depression at any point during monitoring; four consecutive PHQ scores >4 and meeting criteria for minor depression; or four consecutive PHQ scores >4 and a past history of depression.

TDCM is a manualized treatment which has proven to have greater efficacy than usual care for depression in primary and medical care settings.26 TDCM was delivered by a registered nurse trained in TDCM under the supervision of a psychiatrist. TDCM for depression included recommending that the PC clinician initiates treatment with an antidepressant (SSRI was preferred as the initial medication) and frequent monitoring of adverse effects, adherence and depressive symptoms by the BHS. In addition, the BHS provided support and education about depressive disorders to the subject. If the subject experienced other MH problems, such as an anxiety disorder, the BHS would formulate an appropriate treatment plan which could include referral to specialty care or care management for anxiety.

Outcome Measures

Outcomes were assessed six months after the baseline assessment in a telephone interview utilizing the same battery of questionnaires as at baseline. Chart reviews were conducted on all subjects for a six-month period from baseline to track the level of care they received, such as prescribed antidepressants, attendance to specialty MHC visits, and attendance to primary care visits over the course of the study.

Statistics and Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package SAS 9.1. Based on preliminary results from an open label study, this trial had a target recruitment goal of 300 which would provide 80% power to test the primary hypotheses assuming a 20% attrition rate. Primary outcomes included PHQ depression score and having a presence of any psychiatric diagnoses at the end of the study. To further explore the primary hypotheses, we examined a number of secondary outcomes including the presence of each individual disorder, presence of symptoms, and level of overall function. Because these individual disorders are components to the primary hypotheses, we corrected for multiple comparisons by the Bonferroni method. We made similar Bonferroni adjustments for the level of care outcomes, given that they represent mechanisms under the primary hypotheses.

Descriptive analyses included means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and frequencies for categorical variables. To adjust for the impact of clinician clustering on variances of treatment effect estimates, we fitted both linear and logistic models for continuous and binary outcomes, respectively, with generalized estimating equations in the SAS PROC GENMOD procedure. Specifically, we used the sandwich variance estimator that adjusts for such clustering and is implemented in by including /subject=clinician/ in the /repeated statement of SAS PROC GENMOD/.. Variables with significant differences (or close to significant differences) between randomization arms in the baseline analysis were used as covariates in the outcome analyses. For the outcomes with continuous measures, the corresponding baseline variable was also used as a covariate.

As an exploratory analysis of baseline factors that were associated with patient referral to the BHS in the CM arm, we performed a series of logistic regressions with the baseline factors as covariates and contact with BHS. Baseline variables of those referred to the BHS were compared to those who did not require referral. The baseline variables that were significant were tested in a series of forward stepwise logistic regressions, setting the rule for inclusion at p = .15. With the resulting prediction models, we then obtained a predicted BHS referred variable for all patients, including the UC arm. The sample was then separated into two groups based on the predicted BHS referral variables (predicted to BHS referral or predicted to no BHS referral). A separate analysis was conducted on each of the groups and looked for significant randomized intervention (CM versus UC) effects to see if patients who were predicted to be referred to the BHS would be more likely to improve under CM than under the control condition.27

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

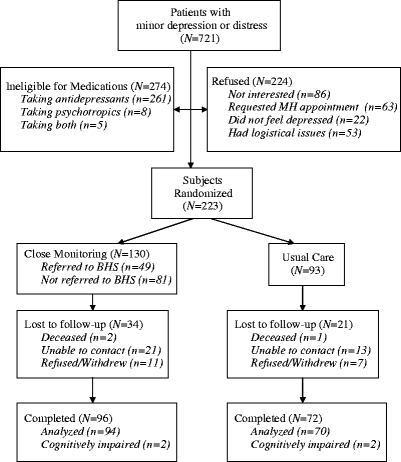

From October 2004 to February 2006, 721 subjects with minor depression or distress were identified as potentially eligible for participation. Figure 1 shows the flow of subjects across the study. Of the 721 subjects, 224 (31.1%) subjects refused, 274 (38.0%) were ineligible for medication, and 223 (30.9%) consented to randomized in the study. Of the 224 subjects who refused, 86 (38.4%) refused because they were not interested, 63 (28.1%) requested an appointment in specialty care, 22 (9.8%) felt that they were not depressed, and 53 (23.7%) refused for logistical reasons: time constraints, moving, lack of a phone, language barriers, and hearing impairment. Of those 274 who were ineligible for medications, 261 (95.3%) were on antidepressants, eight (2.9%) were on psychotropic medications and five (1.8%) were on both.

Figure 1.

Study subject flow diagram.

The sample was demographically similar in terms of gender, where the overall sample was male (93.2%). There were significant differences in age (F = 15.5, 2 df, p < .0001). Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons indicated that there were significant differences between those who refused and those who were ineligible (p < .0001), and between those who consented and those who were ineligible (p < .0001), where those who were ineligible were older (M = 65.4, SD = 14.3) than those who refused (M = 58.5, SD = 16.0) and those who consented (M = 59.2, SD = 15.9). There were also significant differences within the sample in PHQ-9 depression scores (F = 8.8, 2 df, p < .0001). The Bonferroni’s test indicated that there was a significant difference between those who consented and those who refused ( < .007) and those who refused and those who were ineligible (p < .0001), where those who were ineligible (M = 7.1, SD = 4.1), and those who consented (M = 6.8, SD = 3.9) had higher PHQ-9 scores than those who refused (M = 5.6, SD = 4.3).

Baseline Characteristics

Of the 223 that consented to participation, 130 (58.3%) were randomized to the CM arm and 93 (41.7%) were randomized to the UC arm. Randomization was stratified by clinician (n = 54). As shown in Table 1, the randomization arms were demographically similar except for gender, where the subjects in the CM arm were predominantly male (97.7% versus 87.1%) (χ2 = 8.07, 1 df, p = .0012), and financial status, where more subjects in the CM arm reported trouble “making ends meet” (25.4% versus 15.1%) (χ2 = 5.24, 1 df, p = .02). The arms were clinically similar at baseline, except that the CM arm had more subjects reporting trauma exposure (33.9% versus 21.5%) (χ2 = 5.06, 1 df, p = .02), a past history of depression (30.0% versus 19.4%) (χ2 = 3.17, 1 df, p = .08) and a GAD diagnosis (14.6% versus 5.4%) (χ2 = 2.82, 1 df, p = 0.09). In the regression modeling of the intervention effects on outcome, we included each of these variables (gender, financial status, past history of depression, baseline GAD diagnosis, and reporting having PTSD-related symptoms at baseline) as covariates since they were significant or close to significantly related to the randomized intervention assignment and outcome.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Baseline Differences (by Arm)

| Overall N = 223 | Monitoring n = 130 | Usual care n = 93 | Statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic demographics | |||||

| Age | 59.2 (15.9) | 59.8 (14.6) | 58.5 (17.7) | χ2 = 0.17 | 0.54 |

| Sex (% male) | 93.3 | 97.7 | 87.1 | χ2 = 8.07 | 0.0012 |

| Race (% white) | 43.1 | 45.4 | 39.8 | χ2 = 0.66 | 0.42 |

| Finance (% can’t make ends meet) | 21.1 | 25.4 | 15.1 | χ2 = 5.24 | 0.02 |

| Marital status (% married) | 47.1 | 50.0 | 43.0 | χ2 = 1.12 | 0.29 |

| Smoke (% who smoke) | 28.7 | 29.2 | 28.0 | χ2 = 0.04 | 0.84 |

| Depression status | |||||

| Referred for depression | 65.5 | 61.5 | 71.0 | χ2 = 1.51 | 0.23 |

| PHQ total score | 6.8 (3.9) | 7.0 (4.0) | 6.5 (3.7) | χ2 = 0.74 | 0.39 |

| Disability (% have difficulty due to depression) | 45.3 | 44.6 | 46.2 | χ2 = 0.08 | 0.77 |

| Past history of depression | 25.6 | 30.0 | 19.4 | χ2 = 3.17 | 0.08 |

| Would consider treatment now | 17.6 | 17.8 | 17.2 | χ2 = 0.01 | 0.91 |

| Alcohol status | |||||

| Average drinks per week | 2.3 (4.8) | 2.0 (3.6) | 2.7 (6.0) | χ2 = 0.96 | 0.33 |

| General health (SF-12) | |||||

| MCS | 47.7 (10.8) | 47.4 (10.6) | 48.2 (11.0) | χ2 = 0.28 | 0.60 |

| PCS | 41.4 (11.4) | 41.3 (11.1) | 41.6 (11.8) | χ2 = 0.03 | 0.86 |

| Other | |||||

| GAD | 10.7 | 14.6 | 5.4 | χ2 = 2.82 | 0.09 |

| Experienced traumatic event that was disturbing but did not meet criteria for PTSD | 28.7 | 33.9 | 21.5 | χ2 = 5.06 | 0.02 |

| Drug use | 32.3 | 31.5 | 33.3 | χ2 = 0.08 | 0.78 |

Means and standard deviations are reported for continuous variables and percentages are reported for categorical variables

Six-Month Outcomes

Of the 223 randomized subjects, 168 (75.3%) participated in the 6-month follow-up assessment; 96 in the CM arm (73.8%) and 72 in UC (77.4%) (not significant). Of the 168, there were four (2.4%) subjects who showed significant symptoms of cognitive impairment and were not able to complete the rest of the interview (two were in the CM arm and 2 were in UC). Thus, 164 had completed 6-month assessments.

Overall, the subjects in the UC arm exhibited more symptoms and diagnoses than those in the CM arm. Intent-to-treat effects are reported in Table 2, as there were several significant intervention effects across these outcomes. Significantly more subjects in the UC arm had a psychiatric diagnosis compared to subjects in the CM arm. Subjects in the UC arm were more likely to have PTSD symptoms (32.9% versus 21.3%) (χ2 = 5.24, 1 df, p = .02) and to have developed a PTSD diagnosis (15.7% versus 5.3%) (χ2 = 3.84, 1 df, p = .05). Subjects in UC were also more likely to have a GAD diagnosis (14.3% versus 9.6%) (χ2 = 5.29, 1 df, p = .02). Furthermore, subjects in the CM arm had greater improvement in physical functioning (SF-12 PCS scores) than those in the UC arm (M = 45.1, SD = 11.8 versus M = 41.5, SD = 12.4) (χ2 = 5.90, 1 df, p = .02).

Table 2.

Intent to Treat 6-Month Outcome Table*

| Overall (N = 164) | Monitoring (n = 94) | Usual care (n = 70) | Statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression symptoms | |||||

| PHQ total score† | 5.9 (5.0) | 5.7 (4.9) | 6.0 (5.1) | χ2 = 2.37 | 0.12 |

| PTSD factors | |||||

| Experienced traumatic event that was disturbing but did not meet criteria for PTSD | 26.2 | 21.3 | 32.9 | χ2 = 5.24 | 0.02‡ |

| Alcohol | |||||

| Average drinks per week | 2.6 (5.9) | 2.5 (5.6) | 2.8 (6.3) | χ2 = 0.08 | 0.77 |

| General health (SF-12) | |||||

| MCS ( = 156) | 48.1 (10.8) | 48.6 (10.4) | 47.5 (11.3) | χ2 = 1.32 | 0.25 |

| PCS ( = 156) | 43.5 (12.1) | 45.1 (11.8) | 41.5 (12.4) | χ2 = 5.90 | 0.02‡ |

| Individual psychiatric diagnosis | |||||

| Had any psychiatric diagnosis† | 18.9 | 16.0 | 22.9 | χ2 = 4.04 | 0.04 |

| GAD | 11.6 | 9.6 | 14.3 | χ2 = 5.29 | 0.02‡ |

| Current PTSD | 9.8 | 5.3 | 15.7 | χ2 = 3.84 | 0.05‡ |

| Psychosis | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.9 | § | § |

| Panic | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.4 | § | § |

| Illicit drug use | 0 | 0 | 0 | § | § |

| Mania | 1.2 | 0 | 2.9 | § | § |

| Alcohol dependence | 0 | 0 | 0 | § | § |

| Major depression | 7.9 | 7.5 | 8.6 | χ2 = 0.88 | 0.58 |

*The covariates used these outcomes were 1) gender 2) financial status 3) past history of depression 4) Baseline GAD diagnosis and 5) reported having PTSD related symptoms at baseline (adjusted for clinician clustering). For the continuous measures, the corresponding baseline measures were used as a 6th covariate

†Primary outcome measures

‡These were secondary outcomes and were non-significant when adjusting for multiple comparisons

§These variables would not converge with the model used throughout this table (there were not enough subjects who experience the outcome)

Level of Care

Across the six month period from baseline, as demonstrated in Table 3, the CM arm engaged more subjects in MH care than in UC (33.1% versus 6.5%) (χ2 = 16.07, 1 df, p < .0001). Additionally, more subjects in the CM arm were prescribed antidepressants than in UC (16.2% vs. 9.7%). There were no differences in return visits to the PC clinician. Out of the 130 subjects randomized to the CM arm, the mean number of weekly monitoring contacts was 3.5 (SD = 2.5), with 116 subjects (89.2%) completed at least one contact. Throughout the monitoring period, 49 (37.7%) subjects were referred to a behavioral health specialist (BHS). Out of the 49 that were referred to BHS, 30 requested treatment (61.2%) and 19 were referred due to depression symptoms (38.8%).

Table 3.

Summary of Care across Arms*

| Total ( = 223) | Monitoring ( = 130) | Usual care ( = 93) | Statistic | -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average number of Clinical Encounters | |||||

| Primary care | 1.4 (1.9) | 1.5 (1.8) | 1.3 (2.0) | 0.20 | 0.65 |

| Mental health care (including BHS) | 1.1 (2.4) | 1.8 (2.9) | 0.2 (1.0) | 21.90 | <0.0001† |

| All clinical contacts | 2.5 (3.2) | 3.2 (3.6) | 1.5 (2.3) | 10.63 | 0.0011† |

| Proportion of subjects with a clinical encounter | |||||

| Primary care | 69.1 | 70.8 | 66.7 | 0.44 | 0.51 |

| Started an antidepressant | 13.5 | 16.2 | 9.7 | 0.29 | 0.59 |

| Had any MH care (including BHS) | 22.0 | 33.1 | 6.5 | 16.08 | <0.0001† |

*The covariates used these outcomes were 1) gender 2) financial status 3) past history of depression 4) Baseline GAD diagnosis and 5) reported having PTSD related symptoms at baseline (adjusted for clinician clustering). Chi-Squares are reported for generalized estimating equations (GEE)

†These were secondary outcomes and remained significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons

Baseline characteristics were examined as predictors for needing or requesting care in the depression care management component. PHQ score was significantly related to requesting or requiring care, with those referred to the BHS having higher scores than those who were not referred (M = 9.14, SD = 3.37 versus M = 5.72, SD = 3.86) (F = 26.46, 1 df, p < .0001). However, the substantial overlap in range of PHQ scores limits its use as a risk factor. Demographics and a past history of depression or past treatment for depression were not related to needing care. Moreover, the categorization of minor versus distress at baseline was also not associated with outcomes. Although the baseline PHQ score was significantly related to whether patients requested or required care, a ROC analysis failed to define an optimal cut point with a specificity and sensitivity greater than 70%.

DISCUSSION

Overall, those randomized to CM exhibited less MH problems at the conclusion of the trial. We originally hypothesized that those in the CM arm would exhibit less depression at the conclusion of the study. While we did not find significant differences in depressive symptoms, we did find that the CM arm had significantly fewer cases of MH diagnoses, fewer symptoms of PTSD, and improved overall health. Our results indicate that a strategy of close monitoring can identify those who require specialty MH care not only for depression, but across a spectrum of diagnoses, including anxiety disorders. Importantly there were few baseline characteristics that predicted either outcome or request or need for treatment. This underscores the importance of clinician intuition in case identification as well as scores on structured instruments. The lack of an optimal cut point for the PHQ in ROC analysis and the absence of clear baseline predictors further support the value of a prospective monitoring period rather than baseline triage of patients.

Another major goal of this study was to gain a better understanding of minor depression. Our results suggest that there may be subsyndromal forms of MH diagnoses other than depression. For instance, at the 6-month assessment, the UC arm had significantly more subjects with PTSD diagnoses than the CM arm. Because these patients did not meet PTSD criteria six months prior, our findings suggest that patients may have been experiencing a subsyndromal form of the disorder. This points to the need for more research into the possible morbidity that may be associated with subsyndromal PTSD, as well as research into the potential efficacy of CM for this and other anxiety disorders. Future studies will need to focus both on the presence of anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms.

In this study, there was a significant effect in regard to improvement in physical composite scores (PCS) and no effect for mental composite scores (MCS). Since this was a minor depression and distress sample, their mental health functioning would have been expected to be relatively normal at baseline. The PCS scores reflect an older veteran primary care population. Improvement in the PCS scores may have associated with the increased attention received, which may have resulted in increased adherence to treatments that would contribute to improved physical health. Future investigations may incorporate these items to see if these associations exist and are meaningful.

Limitations

It is important to note that there were some limitations in this study. This study was conducted on a VA patient population who were mostly male, and was only conducted in the Philadelphia region. This may limit the generalizability to non-veteran populations, females and regions outside the Philadelphia area. Additionally, a sampling issue occurred as a result of stratifying randomization based on clinician. The women’s care clinicians were all randomized to UC, which does not allow us to infer the impact on the intervention on women. The lack of effect on depression symptoms likely relates to the low level of symptoms that define the issue. Depression symptom reduction may not be the best outcome measure for subsyndromal disorders.

Future Directions

In order to examine the generalizability of the current findings, further investigations need to be conducted that include non-VA populations, higher percentages of women, and subjects from a variety of regions. Future research should be conducted to further investigate subsyndromal PTSD, as it is a new finding and could have significant clinical impact.

In conclusion, these results indicate that the close monitoring program is an effective, feasible and valuable program. The findings of this current study will allow us to enhance the clinical services of the Behavioral Health Laboratory in providing additional monitoring and disease management services to primary care, which will further support the integration of mental health services and primary care. We plan to incorporate CM into the BHL package as a supplementary monitoring service that will be provided to patients with minor depression or distress. We will utilize this experience to further develop the BHL manual set.

Acknowledgements

Supported by Robert Wood Johnson and VISN 4 the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center (PVAMC).

This work was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson foundation and support from the Veterans Integrated Service Network 4 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center. We acknowledge the support and dedication of the Primary Care Clinicians at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the Behavioral Health Laboratory staff.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Financial Support Authors have received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and industry. In addition, Dr. Oslin provides consultation to the Hazelden foundation.

References

- 1.Beck DA, Koenig HG. Minor depression: a review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26:177–209. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Crum RM, Cooper-Patrick L, Ford DE. Depressive symptoms among general medical patients: prevalence and one-year outcome. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:109–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Pincus HA, Davis WW, McQueen LE. ‘Subthreshold’ mental disorders. A review and synthesis of studies on minor depression and other ‘brand names’. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:288–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA. 1992;267:1478–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Judd LL, Paulus MP, Wells KB, et al. Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. Am J Psychiat. 1996;153:1411–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Rapaport MH, Judd LL. Minor depressive disorder and subsyndromal depressive symptoms: functional impairment and response to treatment. J Affect Disord. 1998;48:227–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1989;262:914–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Chopra MP, Zubritsky C, Knott K, et al. Importance of subsyndromal symptoms of depression in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:597–606. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Barrett JE, Barrett JA, OXman TE, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a primary care practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1100–06. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, et al. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264:2524–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Ackermann RT, Williams JW Jr. Rational treatment choices for non-major depressions in primary care: an evidence-based review. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Judd LL, Rapaport MH, Yonkers KA, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine for acute treatment of minor depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1864–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Williams JW Jr, Barrett J, Oxman T, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: A randomized controlled trial in older adults. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:1519–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Katon W, Russo J, Frank E, et al. Predictors of nonresponse to treatment in primary care patients with dysthymia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:20–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Oslin DW, Sayers S, Ross J, et al. Disease management for depression and at-risk drinking via telephone in an older population of veterans. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:931–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Felker BL, Chaney E, Rubenstein LV, et al. Developing effective collaboration between primary care and mental health providers. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8:12–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Oslin DW, Ross J, Sayers S, et al. Screening, assessment, and management of depression in VA primary care clinics, The Behavioral Health Laboratory. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:46–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Oslin DW, Rowland ES, Difilippo S, et al. Behavioral Health Laboratory: Manuals of Operations: Volumes 1-6 (v2).. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center; 2007.

- 19.Kawas C, Karagiozis H, Resau L, et al. Reliability of the blessed telephone information-memory-concentration test. J Geriatr Psychiat Neurol. 1995;8:238–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan K, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed]

- 22.Sobell LC, Brown J, Leo GI, et al. The reliability of the alcohol timeline followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Paykel ES, Myers JK, Lindenthal JJ, et al. Suicidal feelings in the general population: a prevalence study. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;124:460–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-item Short-form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;32:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF 3rd, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;291:1081–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Datto C, Miani M, Disbot M, et al. Preliminary analysis of telephone disease management for depression in primary care in NIMH Mental Health Services Research, Washington, DC; 2000.

- 27.Joffe M, Small D, Hsu C. Defining and estimating intervention effects for groups who will develop an auxiliary outcome. Stat Sci. 2007;22:74–97. [DOI]