Abstract

Background

Long-term oral anticoagulation treatment is associated with potential morbidity. Insufficient patient education is linked to poorly controlled anticoagulation. However the impact of a specific educational program on anticoagulation related morbidity remains unknown.

Objective

To evaluate the effect of an oral anticoagulation patient education program in reducing both hemorrhagic and recurrent thrombotic complications.

Design/Participants

We conducted a prospective, multicenter open randomized study, comparing an interventional group who received a specific oral anticoagulation treatment educational program with a control group. Eligible patients were older than 18 and diagnosed as having deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism requiring therapy with a vitamin K antagonist for 3 months or more. Our primary outcome was the occurrence of hemorrhagic or thromboembolic events.

Results

During the 3-month follow-up the main outcome criteria were observed 20 times (6.6% of patients), 5 (3.1%) in the experimental and 15 (10.6%) in the control group. Consequently, in multivariate analysis, the cumulative risk reduction in the experimental group was statistically significant (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.1 – 0.7, < 0.01).

Conclusions

Patient education using an educational program reduced VKA-related adverse event rates.

KEY WORDS: patient education, vitamin K antagonist

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin K antagonist treatment (VKA) is effective for the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolic diseases (VTE). Notably, VKA allows an 80% risk reduction in the recurrence of thromboembolic events1,2. Therefore, according to guidelines, idiopathic or recurrent VTE needs to be indefinitely treated with oral anticoagulant 3. In contrast, the major hemorrhagic complication rate has been estimated as high as 5% per 100 treated patient-years, especially during the first three months of treatment4–6. This hemorrhagic risk is partially due to the difficulty for both the practitioner and the patient to manage oral anticoagulation.

To answer such health problems, several strategies intended to reduce dosing and/or monitoring errors have been developed. Among these approaches, anticoagulation clinics were an early model for care. In these structures, patients benefit from anticoagulation monitoring and subsequent dose adjustment, especially the use of specific dosing nomograms. Using this approach, patients were within target range about 63.5% of the time7. In terms of INR monitoring, oral anticoagulation self-management has also been described as effective and as safe as management by a specialist anticoagulation clinic, with greater patient-satisfaction8–11. Recently, an education and support program for general practitioners was shown to improve the quality of oral anticoagulation management with regards to the amount of time patients were within 0.5 INR of the target range12. Furthermore, the effects of insufficient understanding of VKA treatment by the patient has already been described13. Moreover, insufficient patient education in oral anticoagulation treatment has been related to poorly controlled anticoagulation2,14. In particular this deficit has been shown to be the major factor predictive of bleeding in the elderly15.

To improve patient education for VKA, we previously described a tailored education intervention16. In this study, we evaluate the effect of this patient education program in reducing VKA-related adverse event rates.

METHODS

Study Design

Educ’AVK (Educational program for VKA) was a prospective, multicenter open randomized study, comparing an interventional group who received a specific education program to a control group who received standard care alone. To avoid contamination between the groups17, we carried out a cluster-randomized study at 15 private practices and 26 hospital departments. As the intervention was dispensed to patients by physicians in private practice and hospital nurses or pharmacists, the unit of randomization was the private practice in the outpatient setting and the hospital department in the hospital setting. Private practice physicians who agreed to participate were recruited among board-certified vascular medicine specialists working in the Grenoble area. Hospital departments were selected from surgical and medical acute care departments at Grenoble University Hospital, a 2200-bed teaching hospital, and at four general hospitals in the district. The Institutional Review Board at Grenoble University Hospital approved the study for both hospital and private practitioners, and all enrolled patients provided written informed consent. The family physicians of all patients were informed about the study, and were not blinded to control or interventional group status.

Patient Eligibility

Physicians at private practices and hospital departments recruited patients from January 2003 through December 2004. Eligible patients were older than 18 and diagnosed as having deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism requiring therapy with a vitamin K antagonist for 3 months or more. Deep vein thrombosis was diagnosed with ultrasonography and categorized as proximal or isolated calf deep vein thrombosis. The diagnosis of pulmonary embolism was based on a high-probability ventilation-perfusion lung scan, a positive spiral computed tomographic scan, or angiography. We excluded patients who had formal contraindication to vitamin K antagonists, did not speak French, or had psychosocial conditions that were incompatible with enrollment, the education process, or follow-up.

Randomization and Study Interventions

Private practices and hospital departments were randomly assigned to the intervention or control group. Randomization was performed by our statistician using a computer-generated sequence with a one-to-one allocation ratio so as to obtain comparable groups of equal sample size. To help ensure comparability of the intervention and control group, randomization was stratified by type of facility (i.e., private practice versus hospital department), annual volume, and surgical versus medical specialty for hospital departments.

Briefly, the tailored educational intervention, lasting 20 to 30 minutes, consisted in one-on-one teaching session (Appendix 1): Identification of the patient’s needs (or educational diagnosis); definition of educational objectives adapted to the patient’s cognitive level and behavior; choice of appropriate teaching contents and methods to reach the objectives16. Moreover, we used and gave the patient a picture book describing the disease and the treatment, and a specific guidance booklet summarizing the information dispensed in the educational program (Appendix 2). In the control group, private practice and hospital physicians provided patients with their usual unstructured information about vitamin K antagonist therapy and a standard booklet published by the French Heart Association.

All patients were advised to see their family physician after hospital discharge or following the ambulatory visit to a vascular medicine specialist. Family physicians managed maintenance dosing, the frequency of international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring, and management of non-therapeutic INR, autonomously. They were recommended to comply with current evidence-based guidelines on vitamin K antagonist therapy9.

Data Collection

Vascular medicine specialists at private practices and nurses in hospital departments collected data on demographics, index venous thromboembolism events, co-morbid conditions, socio-cultural levels (high school graduation grades) and prognostic factors including the Outpatient Bleeding Risk Index rating18. To further characterize thrombotic risk in the control and interventional groups, they also used a baseline thrombotic recurrence risk score based on idiopathic VTE (+1), recurrent VTE (+1) or cancer (+1). A score of one or more defined high thrombotic risk. Research nurses, who were blinded to the study group, conducted structured telephone interviews with the patients or their family 90 days after enrolment to identify episodes of bleeding and symptomatic recurrence of venous thromboembolism. Only episodes of bleeding that required hospital admission or an outpatient visit, with major bleeding as normally defined19, were recorded. Whenever an event was reported, its characteristics were summarized using a structured review chart. No routine tests were performed to detect asymptomatic recurrence of venous thromboembolism. At the end of the 3-month follow up, the research nurses interviewed patients from both the groups and assessed their knowledge using a standardized 18-item questionnaire16 addressing specific features of vitamin K antagonists, optimal therapeutic range, practical management of bleeding or non-therapeutic INR, and management of oral anticoagulation during dental procedures (Appendix 3).

Study Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the occurrence of hemorrhagic or thromboembolic events. All events were reviewed and classified by an adjudication committee whose members were blinded to the study group. Bleeding was defined as major if it was overt and associated with a decrease in hemoglobin level of at least 2 g/dL, needed transfusion of two or more units of red cells, or if it was intracranial or retroperitoneal. Any other episode of bleeding that required hospital admission or an outpatient visit was considered minor. Recurrent thromboembolic events had to be objectively confirmed by the same methods as the index events and located in segments of deep veins or pulmonary arteries that were not previously affected. Our secondary outcome was the number of correct answers to the standardized 18-item questionnaire (range 0 to 20).

Sample Size

Based on the findings of a pilot study16, we assumed a 13% rate of hemorrhagic or thromboembolic events in the control group versus 7% in the intervention group. Under these assumptions, we anticipated a power of 80% to detect a significant difference between the two groups (α = 0.05) with a mean number of 20 patients enrolled per private practice or hospital department and an intracluster correlation of rho = 0.0517.

Statistical Analysis

All patients were analyzed in the group to which they were allocated according to the intention-to-treat principle. Patients’ baseline characteristics were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

Although the unit of randomization was the private practice or hospital department, primary and secondary outcomes were measured at the patient-level and the unit of analysis was the patient. Wherever appropriate we report intracluster correlation coefficients20. We used two-level logistic regression to account for patient clustering within private practices and hospital departments. In multivariable analysis, we estimated the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of the primary outcomes and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) to account for imbalances in patients’ baseline characteristics. Independent variables entered into the model included study intervention arm, stratification variables, and patient characteristics (age, gender, hemorrhagic and thrombotic score, socio-cultural level, VTE characteristics). We tested first-order interactions involving the study intervention arm to determine whether the effect of our intervention differed according to patient characteristics.

values were adjusted for intracluster correlation. Two-sided P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using Stata version 9.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) and MLWin 2.0 (Institute of Education, London, UK).

RESULTS

Patient Population

A total of 302 patients, 135 women (46%) and 167 men (54%), aged 18–91 years (median, 62 years) were entered into the study between January 2002 and December 2004. One hundred and sixty patients enrolled in the hospital, and 142 in the specialist vascular medicine practices. The main characteristics of the patients are described in Table 1. The two groups were comparable with regard to baseline clinical characteristics.

Table 1.

Main Characteristics of Patient Population

| Experimental group ( = 60) | Control group ( = 142) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 58.7 (16.5) | 62 (16) | 0.06 |

| Male | 54.4% | 56.3% | 0.7 |

| Post operative | 9.5% | 14.5% | 0.15 |

| Cancer | 10% | 8.5% | 0.6 |

| Previous VTE | 24.4% | 31% | 0.2 |

| VTE characteristic | 0.65 | ||

| Distal DVT | 16.2% | 14% | |

| Proximal DVT | 37.5% | 33.8% | |

| PE | 46.3% | 51.4% | |

| Percentage of patients with education through high school or further | 52.1% | 46.6% | 0.4 |

| Hemorrhagic risk | 21.2% | 29.6% | 0.1 |

| Thrombotic risk | 21.2% | 16.2% | 0.25 |

Patients were randomized either into the experimental group (which received the educational program) or to the control group

VTE is venous thromboembolic disease; PE is pulmonary embolism

Hemorrhagic risk was defined by the Outpatient Bleeding risk index10. The thrombotic risk was calculated by scoring idiopathic VTE (+1), recurrent VTE (+1) and cancer (+1) and defined as equal to or greater than 1

Efficacy Outcomes of the Educational Program

During the 3-month follow-up, 15 hemorrhagic incidents (5%), including two major bleeding events were recorded. Three (1.9%) hemorrhages occurred in the experimental group (1 major, and 2 non major) versus 12 (8.5%) in the control group (one major, and 11 non major), = 0.01.

During the same period, the incidence of VTE recurrence ( = 7) was similar in the two groups, with = 2 (1.2%) in the experimental group, and = 5 (3.5%) in the control group respectively. Two cases of recurrent pulmonary embolism were observed in the control group.

One of the main outcome criteria was observed 20 times (6.6% of patients), with 5 (3.1%) in the experimental group and 15 (10.6%) in the control group. Consequently, in multivariate analysis, the cumulative risk reduction in the experimental group was statistically significant (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.1 – 0.7, < 0.01).

Although not statistically significant, the mean age was slightly lower in the educational intervention group. Therefore, we tested the efficacy of the educational program according age < or >65 y. The observed benefit was similar whatever the patient age. Similarly, the observed benefit was the same irrespective of whether patients were educated in hospital or in vascular medicine private practices, and whatever the socio-cultural level was (data not shown)

Evaluation of the Patients’ Knowledge

Patients’ knowledge was assessed at 3 months using a standardized 18-item questionnaire and scored from 0 to 20.

The mean knowledge score was higher in the experimental group (13.9 + /−4.5) than in the control group (12.4 +/− 4.9) ( = 0.08). The knowledge score was also higher in younger patients (14.3 + /− 4.6 for patients under 70 years, versus 11.2 + /− 4.4 for the older patients, < 0.01). Also the score was related to the socio-cultural level (15.4 + /− 3.7 versus 11.5 + /− 4.5, < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

VKA treatment is effective for the prevention of venous thromboembolic events. However, the risk of therapy with oral anticoagulants is high because deviation from the target therapeutic range is an important cause of treatment failure, due to both recurrence of thromboembolism and hemorrhagic complications1–6.

To improve both efficacy and safety of oral anticoagulant treatment, several strategies have been developed7–13, including educational intervention. However the exact impact of an oral anticoagulant treatment patient education program remains debatable. Several studies did not report any improvement in control of therapy21,22, although another described an improvement in the quality of anticoagulation23. However these studies only focused on a laboratory evaluation of the intervention, such as the percentage of INR in the therapeutic range and/or the time spent within the therapeutic range.

The major feature of our randomized trial was to test the impact of an educational program on clinical adverse event rates. Also, in this study, we demonstrated that our simple educational program gave patients better knowledge of oral anticoagulant treatment. In our trial, the incidence of thrombotic or hemorrhagic complications was close to that in previous data, but it is important to note that the incidence of adverse events was threefold lower in the educated group compared to the control group. This supports a significant and independent impact of our educational program on the reduction in risk of events (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.1–0.7), whatever the patients’ age or socio-cultural level. This is similar to the results of Beyth et al.24 who developed a multicomponent program for VKA management based not only on education, but also on self monitoring of prothrombin time.

There are several limitations to our trial. First, although family physicians, who monitored VKA, were not specifically informed of the randomization arm, they were not blinded to control or interventional group status. Therefore we cannot exclude that physicians who were able to determine the allocation arm may have been more or less attentive to one or the other group of patients. However, if so, this might also be considered as a beneficial effect of the intensive educational program. Second, we did not control the efficacy of the educational program on the INR-based quality of anticoagulation, because we focused on the reduction in clinical events. This might be a bias because more frequent checks might be associated with fewer adverse events. In contrast, greater awareness to the need for regular INR checks could be considered as beneficial effect of the educational program. Thirdly, educational intervention was not restricted to hospital teams. The study was designed to reflect the French model of care in which private practitioners manage oral anticoagulation. However we demonstrated that the observed benefit was identical whatever the team was. Finally, although we developed, as other teams have done25 a specific questionnaire to test our patients’ knowledge, we were not able to demonstrate a statistical difference between the two groups in their knowledge, probably due to insufficient power of the study.

In conclusion patient education using an educational program reduces VKA-related adverse events.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the vascular medicine physicians participating in the Educ’AVK program: Dr. Antoine, Dr. Baloul, Dr. Brachet, Dr. Belle, Dr. Bucci, Dr. Cumin, Dr. Diamand, Dr. Hugon, Dr. Lebrun, Dr. Martin, Dr. Morzol, Dr. Olive, Dr. Pichot, Dr. Riom, Dr. Roger, Dr. Tanitte, Dr. Toffin, as well as M Proust as clinical research assistant, and A Foote for correcting the English.

Financial support was provided by a grant from The French Agency for Medical Evaluation (ANAES).

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Appendix 1

Details of the Education Session

Euduc’AVK is an education program designed for patients starting an oral anticoagulant treatment following a thromboembolic event.

The sessions of education last 30 to 45 minutes and are led by a pharmacist, a nurse or a doctor trained in therapeutic education. It takes the form of a tutorial that provides information whilst continually ensuring that the patient has understood. The contents are adapted to the needs of the patient, to his lifestyle, to his level of understanding of the illness and to his expectations. Teaching aids, visual supports and booklets, are used to help memorization of the information given orally. Drawings are used illustrate everyday situations.

The intervention consists of a one-to-one teaching session. The organizer introduces himself or herself and explains the aim of the meeting (to provide information and advice on anticoagulation treatment).

The first step consists of an educational diagnosis, including instruction on venous thromboembolic disease (simple diagrams are used to explain the theoretical notions of how a deep vein thrombus forms and how pulmonary embolism occurs), and exploration of the lifestyle of the patient (medical and paramedical environment) and his or her knowledge regarding the disease and the anticoagulant treatment. The information given by the teacher covers: the aims of anticoagulation, the benefits and the risks of the treatment, the surveillance by INR, drug interactions, diet, and what to do in particular situations (forgetting to take a dose, bleeding, medical treatment).

More detailed information is given to particular patients concerning contraception, travel or practicing sport.

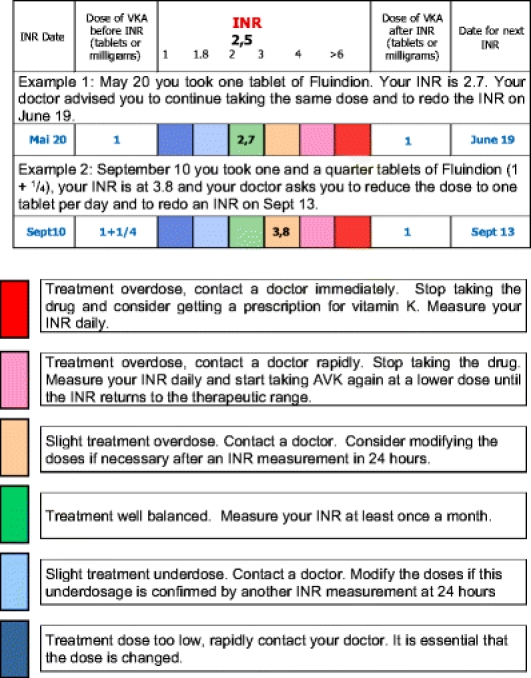

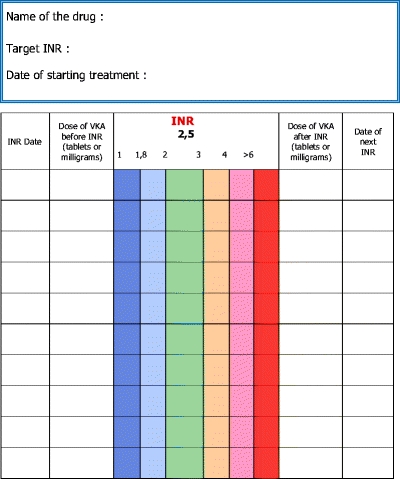

Patients are shown the specific INR guidance and record booklet, shown how to complete it and leave the session with their personal copy. It contains information on venous thromboembolic disease and VKA treatment, a table for recording the results of INR tests with a color code according to the INR value and directions on corresponding action to be taken. The patient is requested to check the box corresponding to the INR value, to interpret the result according to the color and, if necessary, to contact his doctor to modify his anticoagulant doses. The aim is to directly involve the patient in the management of his treatment and encourage him to be an “aware” participant and to provide an example of good practices for the healthcare professionals to whom he will be requested to show his record book.

Appendix 2: Example of the Specific Booklet Used for the Surveillance of INR

Surveillance of VKA Anticoagulant Treatment

EXAMPLE

The dose of the drug is shown in « tablets » for Fluindion, and in « tablets » or in « milligrams » for Warfarin.

After each INR

Interpret your result and contact your doctor.

Appendix 3: the standardized 18-item knowledge questionnaire

| 1. Do you know the name of your oral anticoagulant treatment? | ||

| (Please give the name of the drug.) | Yes | No |

| 2. Do you know why you are on oral anticoagulant treatment? | ||

| (Please give the name of the disease.) | Yes | No |

| 3. Do you know what the effect of you treatment is? | ||

| (Please give details.) | Yes | No |

| 4. How often do you take your treatment? | ||

| 4a) When? | ||

| 4b) What dose? | ||

| 5. Do you know the test used to monitor the treatment? | Yes | No |

| 5a) If yes, please give the name of the test. | ||

| 6. Do you know the target value of the test in the case of VTE? | ||

| •4 – 5 | ||

| •2 – 3 | ||

| •<1 | ||

| •I don’t know. | ||

| 7. What is the major risk in case of overdose? | ||

| 8. What is the major risk in case of underdose? | ||

| 9. Do you know the drugs that interact with your treatment? | ||

| 10. If the INR is above 6, what do you do? | ||

| •I contact my family physician, because I do not understand what happened. | ||

| •I contact my family physician, because of a risk of thrombosis recurrence. | ||

| •I contact my family physician, because of a risk of bleeding. | ||

| •I wait until the next visit to my family practitioner | ||

| 11. Last week, your INR was 1.7. Your practitioner has increased the dosage. Five days later, the INR is 1.5. Are you surprised? | Yes | No |

| (if yes, do you have any explanation.) | ||

| 12. You forgot to take your treatment (1 tablet per day) yesterday evening. What do you do? | ||

| •I take 2 tablets this evening and control the INR. | ||

| •I take 1 tablet this evening and control the INR. | ||

| •I immediately take 1 tablet and control the INR. | ||

| •I phone to practitioner. | ||

| 13. I must have a tooth extraction. What do you do? | ||

| •I stop my treatment 24h before because I risk bleeding. | ||

| •I inform the dentist the day of the extraction. | ||

| •I inform the dentist several days before the extraction. | ||

| •I do not inform the dentist. | ||

| 14. For a few days, you have had bruising. What do you do? | ||

| •I go the an emergency department | ||

| •I wait until the next control of the INR. | ||

| •I control the INR now. | ||

| •I consider there no relationship with my treatment. | ||

| 15. Have you ever forgotten to take your treatment? | ||

| •No, never | ||

| •Yes, one to two times | ||

| •Yes, more than two times | ||

| 16. Do you modify the dose yourself? | ||

| •No, never | ||

| •Yes, sometimes (why) |

REFERENCES

- 1.Kearon C, Hirsh J. Management of anticoagulation before and after elective surgery. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1506–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Palareti G, Legnani C, Guazzaloca G, et al. Risks factors for highly unstable response to oral anticoagulation: a case-control study. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:72–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Büller HR, Agnelli G, Hyers TM, Prins MH, Raskob GE. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease. The seventh ACCP consensus conference on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. Chest. 2004;126:420S–28S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ridker PM, Goldhaber SZ, Danielson E, et al. PREVENT Investigators. Long-term, low-intensity warfarin therapy for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1425–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Kovacs MJ, et al. Extended Low-Intensity Anticoagulation for Thrombo-Embolism Investigators. Comparison of low-intensity warfarin therapy with conventional-intensity warfarin therapy for long-term prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:631–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Linkins LA, Choi PT, Douketis JD. Clinical impact of bleeding in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:893–900. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gadisseur AP, Breukink-Engbers WG, van der Meer FJ, van den Besselaar AM, Sturk A, Rosendaal FR. Comparison of the quality of oral anticoagulant therapy through patient self-management and management by specialized anticoagulation clinics in the Netherlands: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2639–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Menéndez-Jándula B, Souto JC, Oliver A, et al. Comparing self-management of oral anticoagulant therapy with clinic management: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ansell J, Jacobson A, Levy J, Völler H, Hasenkam JM. International Self-Monitoring Association for Oral Anticoagulation. Guidelines for implementation of patient self-testing and patient self-management of oral anticoagulation. International consensus guidelines prepared by International Self-Monitoring Association for Oral Anticoagulation. Int J Cardiol. 2005;99:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gadisseur AP, Kaptein AA, Breukink-Engbers WG, van der Meer FJ, Rosendaal FR. Patient self-management of oral anticoagulant care vs. management by specialized anticoagulation clinics: positive effects on quality of life. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:584–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Cromheecke ME, Levi M, Colly LP, et al. Oral anticoagulation self-management and management by a specialist anticoagulation clinic: a randomised cross-over comparison. Lancet. 2000;356:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Claes N, Buntinx F, Vijgen J, et al. The Belgian Improvement Study on Oral Anticoagulation Therapy: a randomized clinical trial. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2159–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Gras-Champel V, Voyer A, Guillaume N, et al. Quality evaluation of the management of oral anticoagulation therapy: the awareness of treating physicians and the education of patients needs to be improved. Am J Ther. 2006;13:223–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Sawicki PT. A structured teaching and self-management program for patients receiving oral anticoagulation: a randomized controlled trial. Working Group for the Study of Patient Self-Management of Oral Anticoagulation. JAMA. 1999;281:145–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kagansky N, Knobler H, Rimon E, Ozer Z, Levy S. Safety of anticoagulation therapy in well-informed older patients. Arch Int Med. 2004;164:2044–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Leger S, Allenet B, Calop J, Bosson JL. Therapeutic education of patients receiving anticoagulants for thromboembolic venous disease: description of the Educ’AVK program. J Mal Vasc. 2004;29:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Donner A, Shoukri MM, Klar N, Bartfay E. Testing the equality of two dependent kappa statistics. Stat Med. 2000;19:373–87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Beyth RJ, Quinn LM, Landefeld CS. Prospective evaluation of an index for predicting the risk of major bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin. Am J Med. 1998;105:91–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Schulman S, Kearon C. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. Scientific and Standardization Committee Communication. on behalf of the subcommittee on control of anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:692–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Campbell MK, Grimshaw JM, Elbourne DR. Intracluster correlation coefficients in cluster randomized trials: empirical insights into how should they be reported. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Laporte S, Quenet S, Buchmüller-Cordier A, et al. Compliance and stability of INR of two oral anticoagulants with different half-lives: a randomised trial. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:458–67. [PubMed]

- 22.Barcellona D, Contu P, Marongiu F. A “two-step” educational approach for patients taking oral anticoagulants does not improve therapy control. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;22:185–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Khan TI, Kamali F, Kesteven P, Avery P, Wynne H. The value of education and self-monitoring in the management of warfarin therapy in older patients with unstable control of anticoagulation. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:557–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Beyth RJ, Quinn L, Landefeld CS. A multicomponent intervention to prevent major bleeding complications in older patients receiving warfarin. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Int Med. 2000;133:687–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Zeolla MM, Brodeur MR, Dominelli A, Haines ST, Allie ND. Development and validation of an instrument to determine patient knowledge: the oral anticoagulation knowledge test. Ann Pharmather. 2006;40:633–8. [DOI] [PubMed]