Abstract

Human mitochondrial leucyl-tRNA synthetase (hs mt LeuRS) achieves high aminoacylation fidelity without a functional editing active site, representing a rare example of a class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) that does not proofread its products. Previous studies demonstrated that the enzyme achieves high selectivity by using a more specific synthetic active site that is not prone to errors under physiological conditions. Interestingly, the synthetic active site of hs mt LeuRS displays a high degree of homology with prokaryotic, lower eukaryotic and other mitochondrial LeuRSs that are less specific. However, there is one residue that differs between hs mt and Escherichia coli (E. coli) LeuRSs located on a flexible closing loop near the signature KMSKS motif. Here we describe studies indicating that this particular residue (K600 in hs mt LeuRS and L570 in E. coli LeuRS) strongly impacts aminoacylation in two ways – it affects both amino acid discrimination and transfer RNA (tRNA) binding. While this residue may not be in direct contact with the amino acid or tRNA substrate, substitutions of this position in both enzymes leads to altered catalytic efficiency and perturbations to the discrimination of leucine and isoleucine. In addition, tRNA recognition and aminoacylation is affected. These findings indicate that the conformation of the synthetic active site – modulated by this residue - may be coupled to specificity and provide new insights into the origins of selectivity without editing.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs)1 are important translational factors. They catalyze the covalent attachment of amino acids to their cognate tRNAs, an essential step in the translation of the genetic code (1–3). The fidelity of protein synthesis is dependent upon the accuracy with which aaRSs discriminate between cognate and noncognate amino acids and numerous cellular tRNAs.

To explain the high fidelity for cognate amino acids exhibited by aaRSs, a “double sieve” model has been proposed. This model, relevant mainly to class I aaRSs, relies on the use of two functionally independent active sites to achieve amino acid selectivity (4, 5). In the first synthetic active site, amino acids are recognized, activated with ATP, converted to aminoacyl adenylates, and then transferred to tRNA. Amino acids larger than the cognate substrate are excluded from this site by sterics; smaller amino acids present a more significant problem as they can be bound, misactivated, and used erroneously to acylate tRNA. To resolve these errors, some aaRSs utilize a second editing active site that proofreads the products made by the activation site and hydrolytically cleaves substrates containing non-cognate amino acids. Both pre-transfer editing of misactivated aminoacyl adenylates and post-transfer editing of misacylated tRNA can occur at this second active site. Many systems are severely affected by the loss of this editing activity, with translational inaccuracies leading to perturbed cellular function (6–8).

Many previous studies have focused on the editing activities of several bacterial and yeast class Ia aaRSs, such as those from Thermus thermophilus (T. thermophilus), Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. An insertion domain that is located between the two halves of the Rossmann fold and referred to as connective polypeptide 1 (CP1) is known to perform this activity (9). In IleRS, ValRS, and LeuRS, this insertion ranges from 250–275 amino acids in length and is highly conserved for a given enzyme across many species (10). Within these three class Ia enzymes, residues have been identified within CP1 that are critical for editing activity by mutational analysis (6–8, 11–22).

However, there have been significantly fewer biochemical or structural studies directed towards understanding amino acid selectivity at the first synthetic active site for class I synthetases. It has become increasingly apparent that aaRSs achieve remarkable specificity for tRNAs through identity elements (23, 24) and anti-determinants (25, 26). Differentiating between structurally-related amino acids presents an even more significant challenge, as fewer functional groups are available for recognition. One mechanism that aaRSs may use to achieve selectivity in the synthetic active site for amino acids could involve induced-fit conformational changes of the enzyme. For instance, amino acid binding leads to structural changes of varying degrees in class I aaRSs such as E. coli MetRS and CysRS, Saccharomyces cerevisiae ArgRS and T. thermophilus TyrRS (27–30). Likewise, formation of the aminoacyl adenylate in TyrRS, TrpRS and LeuRS also causes conformational reorganization, including positioning of the catalytically critical lysine in the conserved KMSKS motif in class I aaRSs (30–32). These conformational rearrangements, long-range electrostatic interactions (33), and the use of metal ions (34) can aid in the recognition of cognate and noncognate amino acids at the synthetic active site for various aaRSs.

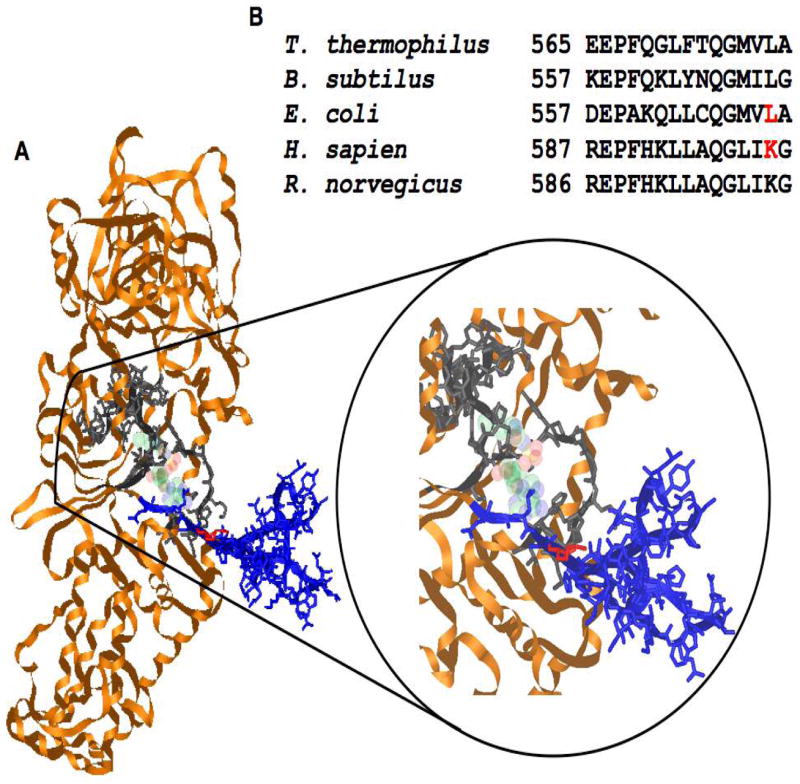

We report here on the unique features of the hs mt LeuRS that allow this enzyme to achieve accurate aminoacylation. The architecture of the synthetic active site within the hs mt LeuRS was investigated by site-directed mutagenesis. In particular, a residue was altered that constitutes an important difference within the highly homologous active sites of hs mt LeuRS and E. coli LeuRS. This position - K600 in the mitochondrial enzyme and L570 in the bacterial enzyme - is located on a flexible loop adjacent to the active site (Figure 1A). When certain mutations were made at these positions, amino acid specificity increased. However, the efficiency of tRNA aminoacylation decreased significantly. It appears that the sequences of the hs mt LeuRS and its bacterial counterpart have finely tuned synthetic active sites that balance the need for amino acid specificity, tRNA binding and aminoacylation.

Figure 1.

(A) Homology model of hs mt LeuRS against T. thermophilus LeuRS (1OBH) with a pre-transfer editing substrate in the Rossmann fold. Domain and motifs are colored as followed: leucyl-specific domain (blue), residues of synthetic active site (gray) and rest of enzyme (orange). Location and positioning of K600 (red). (B) Multiple sequence alignments on the domain containing the residues mutated in E. coli (L570), and human mitochondria (K600) LeuRSs; both residues are highlighted in red. Initial homology models were created with DeepView/Swiss-PdbViewer then visualized with iMol.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and preparation of tRNA constructs

Wild-type (WT) hs mt tRNALeu(UUR) and E. coli tRNALeu(CUN) were prepared as described (35). Plasmids were harvested from XL1-Blue competent cells (Stratagene) and digested with Mva1 (Ambion) to generate the 3′ CCA end. The digested DNA was then phenol/chloroform extracted (pH 8, Sigma), ethanol precipitated and resuspended in distilled H2O. The DNA was furthered purified using G-25 columns (Amersham Pharmacia). Transcription reactions were performed using template DNA (100–200 μg/mL), T7 RNA polymerase (overexpressed in E. coli), RNAsin (0.2 units/μL, Promega), 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM spermidine, 20 mM MgCl2, 4 mM NTPs and 5 mM dithiothreitol. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 6 hours, with the addition of a second aliquot of polymerase after three hours. The DNA template was then digested with DNase I (60 units/mL, Takara) for 30–45 minutes. RNA products were extracted with 5:1 phenol/chloroform (pH 4.7, Sigma) and ethanol precipitated. Transcription products were further purified by 12% denaturing PAGE using 0.5× TBE buffer (45 mM Tris base/45 mM boric acid/1mM EDTA) for 5 hours. Purified transcripts were recovered by electroelution, and were ethanol precipitated. tRNA was resuspended in 0.5× TE (5mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 0.5 mM EDTA). All solutions were prepared with diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) treated water.

Absorbance at 260 nm was used to quantify the concentration of tRNA in solution. Values were obtained by applying an extinction coefficient of 895,000 M−1 (mononucleotide) cm−1 (hs mt tRNALeu(UUR)) and 905,000 M−1 cm−1 (E. coli tRNALeu(CUN)) (http://www.genscript.com/cgi-bin/tools/primer_calculation). tRNA samples were annealed with incubation at 70°C for 5 minutes in distilled water followed by addition of MgCl2 (10 mM) and immediate cooling on ice for at least 20 minutes.

Preparation of LeuRSs

Mutant hs mt and E. coli LeuRS plasmids were generated using the QuikChange multi-site directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Both WT and mutant forms of hs mt LeuRS were expressed and purified as described (35, 36). All E. coli LeuRSs were purified from SG13009 cells carrying the pREP4 repressor plasmid as described (20); WT E.coli LeuRS plasmids were provided by D. Tirrell, Caltech, Pasadena, CA. After cell lysis in a French press, the enzymes were purified using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) then by FPLC (Bio-Rad Duo Flow) using 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7) and elution buffer of 50 mM Tris/1 M NaCl (pH 7). A cation exchange column (HiTrap SP HP, Amersham Biosciences) was used to purify WT and mutant hs mt LeuRSs and an anion exchange column (Bio-Rad UNO™ Q-1) for the E. coli LeuRS enzymes. The purity of the protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Initial enzyme concentrations were determined by Bradford protein assay (Biorad) followed by an active site titration to obtain final enzyme concentrations.

Active site titration of LeuRSs

Active site titration was measured using a charcoal-based method adapted from that described by Hartley and coworkers to obtain a final concentration for enzymes (37). 150 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 5 mM MgCl2, 6 μM ATP, 1mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 10 μg/mL inorganic pyrophosphatase, 10 mCi [γ-32P]-ATP, 1mM leucine, 2.9 mM 2-mercaptoethanol were incubated at 37°C. Triplicate aliquots (45 μL for zero time readings) were separately mixed and quenched with 450 μL of 6% activated charcoal, 0.3% HCl, 3.1% HClO4. The quench solution was then transferred to a screening column (Fisher). The charcoal was washed three times with quench buffer (7% HClO4). The amount of [γ-32P]-ATP dissipated was quantified by scintillation counting of the charcoal. The requisite aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (2 μM) was added to the reaction mixture and aliquots were periodically taken and quenched as above.

Aminoacylation assays

tRNA samples were annealed as described above. Aminoacylation assays were performed at 37°C in reaction mixtures containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 0.2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 25 mM KCl, 100 μM spermine, 7 mM MgCl2, 100 μM leucine, 4 μM [3,4,5-3H] leucine (Perkin Elmer). Kinetic parameters for hs mt tRNALeu(UUR) were determined using 20 nM WT hs mt LeuRS, 40 nM mutant hs mt LeuRS or 300 nM WT and mutant E. coli LeuRS with concentrations of hs mt tRNALeu(UUR) ranging from 3 μM – 60 μM. Kinetic parameters for E. coli tRNALeu(CUN) were determined using 20 nM WT or mutant hs mt LeuRS, and 10 nM WT or mutant E. coli LeuRS with concentrations of E. coli tRNALeu(CUN) ranging from 0.5 μM – 25 μM. Aliquots (2 μL) of the reaction mixture were precipitated on pretreated and dried Whatman circles with 5% TCA, washed three times with 5% TCA for one hour, and then soaked in ethanol before drying. The level of aminoacylation of the tRNA was determined by scintillation counting. The data represents the average of at least three determinations.

ATP-PPi exchange assay

Amino acid activation by hs mt and E.coli LeuRS was analyzed at 37°C in reaction mixtures containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM potassium fluoride (Labchem), 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM ATP, 7 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 6.6 μM [32P]-PPi. Kinetic parameters for leucine activation were determined using 20 nM WT and mutant hs mt or E. coli LeuRS and concentrations of leucine ranged from 10 μM – 10 mM. For isoleucine activation, 200 nM WT and mutant hs mt or E. coli LeuRS were used. The concentrations of isoleucine ranged from 2 mM –140 mM (hs mt LeuRS) and 0.01 mM – 1.5 mM (E. coli LeuRS). Aliquots (45 μL) of the reaction were removed and quenched in 450 μL of 6% activated charcoal, 3.4% HCl, and 0.12 M NaPPi. The quench solution was then transferred to a screening column (Fisher). The charcoal was washed two times with quench buffer (0.2 M NaPPi, and 7% HClO4). The amount of [32P]-PPi converted into [32P]-ATP was quantified by scintillation counting of the charcoal. The data represents the average of at least three determinations.

Results

Amino acid activation by K600 mutants of hs mt LeuRS

The synthetic active sites of bacterial and mitochondrial LeuRSs display a very high degree of similarity. When sequence alignments were analyzed, few differences were detected that were conserved among bacterial versus mitochondrial sequences. One interesting variation, however, was identified at position 600 in the hs mt LeuRS. In mitochondrial LeuRSs, this position is typically occupied by a lysine residue, while bacterial homologues usually contain a leucine (Figure 1B).

To examine the functional role of this amino acid, three mutants of the hs mt LeuRS - K600L, K600R, and K600F - were constructed and analyzed. Cognate amino acid activation, non-cognate amino acid activation, and tRNA aminoacylation efficiency were studied for the mutated enzymes in comparison to the wild-type (WT) enzyme.

Experiments where leucine activation was investigated revealed that this reaction was more efficient for a subset of the mutants (Table 1A). The apparent binding affinity for leucine is 5 and 2 times tighter for K600L and K600R, respectively, in comparison to WT hs mt LeuRS (Table 1A). For the K600F mutant, the Km for leucine is two-fold weaker. The catalytic turnover for K600L is similar to WT, however the K600R and K600F mutants both showed a 3-fold increase.

Table 1.

| Table 1A. Kinetic parameters for the activation of leucine and isoleucine by WT and mutant hs mt LeuRSs. Kinetic parameters were determined at pH 7.5 and 37°C, Data shown represent average values obtained from > 3 trials

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leucine | Isoleucine | ||||||

| Km (mM) | Kcat (s−1) | Kcat/Km(s−1 μM−1) | Km(mM) | Kcat (s−1) | Kcat/Km(s−1 μM−1) | Discrimination Factor | |

| WT hs mt LeuRS:a | 0.15(4) | 7.9 (5) | 0.05 (1) | 11 (1) | 0.44 (1) | 0.00004 (1) | 1300 |

| hs mt K600L: | 0.03(5) | 5.9 (5) | 0.2 (1) | 11 (2) | 0.14 (1) | 0.000013 (3} | 15,000 |

| hs mt K600R: | 0.07(1) | 27 (1) | 0.42 (8) | 1.1 (3) | 0.52 (1) | 0.00049 (4) | 320 |

| hs mt K600F: | 0.33 (3) | 25 (1) | 0.08 (3) | 0.9 (3) | 0.50 (2) | 0.00058 (6) | 140 |

| Table 1B. Kinetic parameters for the activation of leucine and isoleucine by WT and mutant E. coli LeuRSs. Kinetic parameters were determined at pH 7.5 and 37°C, Data shown represent average values obtained from > 3 trials

| |||||||

| Leucine | Isoleucine | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Km(mM) | Kcat(s−1) | Kcat/Km (s−1 μM−1) | Km(mM) | Kcat(s−1) | Kcat/Km (s−1 μM−1) | Discrimination Factor | |

| WT E. coli LeuRS: | 0.013 (2) | 29 (1) | 2.2 (5) | 0.14 (4) | 0.51 (2) | 0.0036 (5) | 600 |

| E. coli L570K: | 0.013 (2) | 37 (1) | 2.8 (5) | 1.5 (2) | 0.76 (3) | 0.0005 (2) | 5600 |

| E. coli 570R: | 0.003 (2) | 43 (1) | 14.3 (5) | 0.09 (2) | 0.23 (1) | 0.0026 (5) | 5500 |

| E. coli L570F: | 0.15 (2) | 35 (1) | 0.23 (5) | 0.05 (1) | 0.55 (1) | 0.0108 (7) | 20 |

For WT hs mt LeuRS, trie Km values for both leucine and isoleucine were the same as those in a prior report (38), However, the Kcat, values increased ~4-fold, which is a result of the more stringent purification process and the active site titration that determines the number of catalytically competent active sites on aaRSs, this is also true for the E. coli enzymes.

A different trend was observed when the non-cognate amino acid, isoleucine, was examined (Table 1A). Catalytic turnover for K600R and K600F was not significantly affected, while interestingly, the K600L mutant showed a 4-fold reduction in isoleucine turnover but the same binding affinity as WT LeuRS. Both K600R and K600F revealed a 10-fold enhancement in binding affinity for isoleucine with Km values of 1.1 mM and 900 μM.

Measuring the efficiency of leucine and isoleucine activation by WT LeuRS and the K600 mutants permitted the calculation of discrimination factors describing the selectivity of the LeuRSs for leucine relative to isoleucine. Within the K600R construct, the conservative change from the original lysine showed a slightly lower discrimination ratio. The K600F mutant demonstrated a 9-fold decrease in its ability to distinguish between leucine and isoleucine effectively. Interestingly, K600L, where leucine is the residue present in E. coli, exhibited an 11-fold enhancement in the discrimination ratio between leucine and isoleucine. This is due to a lower kcat value for isoleucine and a lowered Km for leucine.

L570 mutants of E. coli LeuRS and amino acid activation

As L570 within E. coli. LeuRS occupies the same position as K600 in hs mt LeuRS, we investigated how changes in this residue would affect amino acid selectivity. The kinetic parameters for leucine and isoleucine activation were measured, and it was determined that the kcat for all three mutants were very similar (Table 1B). The only exception was for L570R, where catalytic turnover for isoleucine was decreased by a factor of two. The major difference lies in the binding for both leucine and isoleucine by the mutated LeuRSs. L570R had a 4-fold stronger binding affinity for leucine, whereas L570F had an 11-fold higher Km. The mutant L570K had comparable kinetic parameters for leucine activation as the WT enzyme. Similarly, the catalytic defects for isoleucine are strongly related to Km defects. The Km for L570R is similar to WT, whereas L570F binds isoleucine more tightly by a factor of three. Conversely, the apparent binding affinity for isoleucine is 10 times weaker for the L570K mutant relative to WT.

The discrimination ratios of the mutants were calculated for all three E. coli LeuRS variants (Table 1B). This analysis revealed several key differences in the specificity of these mutant enzymes for leucine versus isoleucine, with L570K and L570R demonstrating enhanced discrimination of leucine versus isoleucine. Both mutants containing amino acids with positively charged side chains exhibited 9-fold increases in discrimination ratio. Similar to the K600F hs mt LeuRS mutant, the E. coli L570F variant displays the lowest discrimination between the two amino acids, recognizing leucine and isoleucine equally.

Aminoacylation efficiencies exhibited by mutant LeuRSs for hs mt tRNALeu(UUR) and E. coli tRNALeu(CUN)

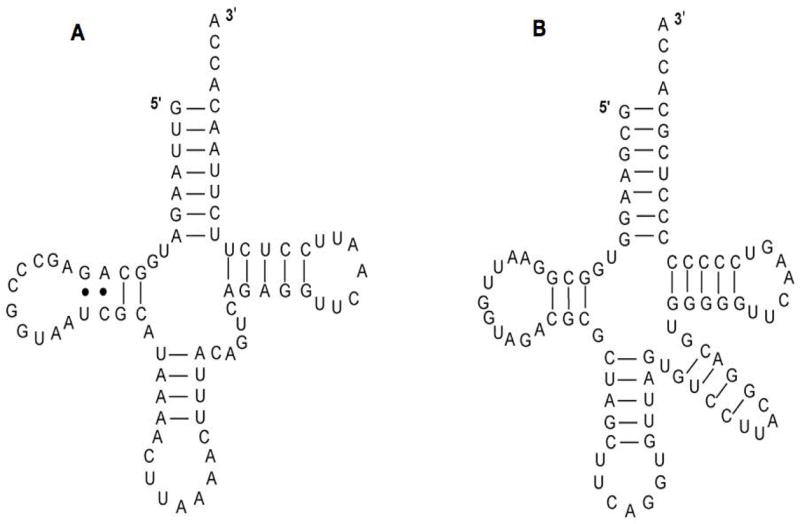

To explore whether K600 was an important residue in tRNA recognition, the kinetic parameters for aminoacylation of the E. coli tRNALeu(CUN) and hs mt tRNALeu(UUR) were determined (Figure 2). The binding affinity for hs mt tRNALeu(UUR) varied significantly between the three hs mt mutants (Table 2A). The mutant with a conservative change from the native sequence, K600R, had the same Km and similar catalytic turnover to WT. For the K600F mutant, a 1.5 fold increase in Km was observed indicating slightly weaker binding to tRNALeu(UUR). However, no apparent difference in kcat was observed. Interestingly, K600L displays increased binding affinity with a lowered Km for tRNALeu(UUR). However, a 30-fold decrease in kcat is observed for K600L. In contrast, the two other mutants showed little to no variation in kcat/Km. (See supporting Information Figure 1A for relative efficiencies for tRNALeu(UUR)).

Figure 2.

tRNALeu cloverleaf structures. (A) hs mt tRNALeu(UUR) (B) E. coli tRNALeu(CUN)

Table 2.

| Table 2A. Kinetic parameters for the aminoacylation of E. coli tRNALEU(cun) and hs mt tRNALEU(UUR) by WT and mutant hs mt LeuRSs. Kinetic parameters were determined at pH 7.0 and 37°C. Data shown represent average values obtained from > 3 trials

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E.coli tRNACUN | hsmttRNAUUR | |||||||

| Km(μM) | Kcat(s−1) | Kcat/Km (s−1 μM−1) | RelativebKcat/Km | Km(μM) | Kcat(s−1) | Kcat/Km (s−1 μM−1) | RelativebKcat/Km | |

| WT hs mt LeuRS: | 0.2 (1) | 0.39 (1) | 2.0 (1) | 0.06 | 4 (2) | 0.09 (1) | 0.024 (4) | 1 |

| hs mt K600L: | 1.8 (4) | 0.35 (2) | 0.19 (5) | 0.005 | 1.5 (9) | 0.0027 (2) | 0.0018 (5) | 0.075 |

| hs mt K600R: | 1.3 (2) | 3.2 (1) | 1.8 (5) | 0.05 | 4 (1) | 0.14 (1) | 0.03 (1) | 1.25 |

| hs mt K600F: | 2.2 (2) | 3.0 (1) | 1.4 (5) | 0.04 | 6 (2) | 0.13 (1) | 0.02 (5) | 0.83 |

| Table 2B. Kinetic parameters for the aminoacylation of E. coli tRNALeu(CUN) and hs mt tRNALeu(UUR) by WT and mutant E. coli LeuRSs. Kinetic parameters were determined at pH 7.0 and 37°C, Data shown represent average values obtained from > 3 trials

| ||||||||

| E.coli tRNACUN | hs mt tRNAUUR | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Km(μM)) | Kcat(s−1) | Kcat/Km (s−1 μM−1) | Relative Kcat/Km | Km(μM) | Kcat(s−1) | Kcat/Km (s−1 μM−1) | Relative Kcat/Km | |

| WT E. coli LeuRS: | 0.4 (1) | 14.5 (7) | 36 (7) | 1 | 25 (12) | 16 × 10−4(1) | 6.4 × 10−6 (1) | 0.0003 |

| E. coli L570K: | 0.9 (2) | 9.8 (5) | 11 (3) | 0.31 | 2 (1) | 1.8× 10−5(2) | 0.9 × 10−5 (2) | 0.0004 |

| E. coli L570R: | 1.5 (3) | 21 (1) | 14 (3) | 0.39 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| E. coli L570F: | 2.9 (5) | 24 (1) | 8 (2) | 0.22 | 1.7 (6) | 2.9 × 1Q−3 (2) | 1.7 × 10−3 (3) | 0.07 |

All hs mt tRNUUR relative Kcat/Km values are with respect to aminoacylation of WT hs mt LeuRS and tRNAUUR; whereas all tRNACUN relative Kcat/Km are with respect to WT E.coli LeuRS and tRNACUN.

N.D. = not detectable

All three mutants demonstrated similar aminoacylation efficiencies for E. coli tRNALeu(CUN), with ~ 10-fold decreases in binding capacity observed (Table 2A) relative to the WT hs mt LeuRS. The catalytic turnover increased 8-fold for the two mutants K600F and K600R. However, the kcat values were similar for K600L and WT. To compare the efficiencies of the enzymes, relative kcat/Km values were determined. After WT, K600R exhibited the most efficient tRNA aminoacylation followed by K600F. Lastly, K600L was the least efficient enzyme, with an extremely attenuated kcat/Km for aminoacylation for tRNALeu(CUN). In general, the human variants have extremely low relative efficiencies for tRNALeu(CUN) in comparison to the E. coli mutants (see supporting Information Figure 1B).

The role of L570 within E. coli LeuRS in tRNA recognition and positioning during aminoacylation was also explored. Mutating L570 to a positively charged amino acid affected the binding to tRNALeu(UUR) dramatically. The L570K mutant shows significantly stronger tRNA binding, but the turnover between this enzyme and tRNA for the process of aminoacylation decreased by a factor of 10 in comparison to WT E. coli LeuRS. L570F exhibits a similar binding affinity as L570K, but has a drastically higher kcat in comparison to all E. coli LeuRSs (Table 2B).

Just like the K600 mutants, the L570 mutants demonstrate weaker tRNALeu(CUN) binding in relation to WT. There was a ~2–4 fold increase in Km for L570K and L570R, while the L570F displayed a Km value elevated by a factor of 7, indicating for all three enzymes a weaker binding affinity for tRNALeu(CUN) (Table 2B). The kcat values did not differ significantly for each mutant in comparison to WT. However, the small increases in Km values coupled with small changes in kcat values produces significant differences in the efficiency of the aminoacylation reaction, with aminoacylation decreased for all mutants by a factor of 3–4 with tRNALeu(CUN). However, the three variants have extremely attenuated relative efficiencies for hs mt tRNALeu(UUR) indicating that E. coli LeuRS and its mutants exhibit better discrimination of the two tRNAs.

Discussion

Identification of an amino acid in the LeuRS active site with dual functionality

The results presented here indicate that a single active site residue can modulate both amino acid discrimination and tRNA binding. A careful balance appears to be maintained by the existence of K600 within the sequence of hs mt LeuRS and L570 within E. coli LeuRS. With the WT residues in place, the enzymes possess sufficient specificity to discriminate cognate versus noncognate amino acids, while still maintaining sufficient tRNA binding affinity. Alterations of these amino acids affect the two enzymes in the same way, in that amino acid discrimination is enhanced, but tRNA binding affinity is attenuated.

Roles of a flexible domain containing a critical residue in amino acid discrimination

The hs mt LeuRS appears to lack editing activity and achieves aminoacylation fidelity solely using its precise synthetic active site, which is not characteristic of other bacterial and eukaryotic LeuRSs studied to date (6–8, 11–22, 38). The hs mt LeuRS must possess special features within its active site that provide the uniquely high levels of amino acid specificity.

Crystallographic structures of the T. thermophilus LeuRS complexed with a small molecule inhibitor bound to the synthetic active site (19) and tRNALeu in the post-transfer editing configuration (39) reveal the existence of a potentially mobile flap that contains the crucial K600 and L570 residue in hs mt and E. coli LeuRS respectively. This flexible closing domain (residues 577–634 in T. thermophilus), also called the leucyl-specific domain, is located just before the catalytically important KMSKS motif (32) (Figure 1). The domain is connected to a β-ribbon and may have significant rotational freedom (32). Another aaRS with a similar active site architecture is the E. coli AspRS that features a flexible closing loop bringing crucial residues into close proximity the substrates in the synthetic active site (33). There are also examples of aaRSs where binding of substrates leads to conformational changes and movement of flexible domains in aaRSs. In many class I aaRSs, the mobile KMSKS loop, in conjunction with the conserved HXGH motif is essential in stabilizing the transition state of the amino acid activation reaction (3, 40). With the movement of flexible domains like the KMSKS loop, these rearrangements may also create a suitable environment for the discrimination of cognate and noncognate amino acids.

The residue under investigation in this study, the K600 in hs mt LeuRS and L570 in E. coli LeuRS, can be visualized within the protein structure using the T. thermophilus LeuRS to gain insight about its function (19, 39) (Figure 1). It is located on the flexible leucyl-specific domain in close proximity to the conserved KMSKS motif. The amino acid binding site is located deeper in the hydrophobic cleft than the ATP binding pocket; this position suggests that cognate leucine or noncognate isoleucine is likely to bind prior to ATP in an ordered mechanism. The binding pocket appears to be large enough to fit either leucine or isoleucine. This suggests that some structural rearrangements must occur in the course of binding of leucine or isoleucine with ATP that allows the LeuRSs to permit aminoacyl-adenylate formation and discriminate between the two amino acids.

Given the results obtained with the hs mt K600 and E. coli L570 mutants described here, it is clear that - although these residues are unlikely to come into direct contact with amino acids within the active site of LeuRS due to the depth at which the amino acids are located in the binding pocket - they do play an important role in controlling specificity. It appears likely that these residues modulate the conformation of the active site, potentially by modulating contacts between the flexible loop and the rest of the enzyme. The fact that this type of distal effect can control amino acid discrimination is interesting, and supports the idea that conformational changes are an important factor in obtaining accurate aminoacylation.

Identification of a residue important in tRNA binding

Comparisons of tRNA-bound and unbound structures of GluRS, ArgRS, TryRS and IleRS reveal induced-fit structural reorganization, including domain rotations, loop ordering and side chain movements (29, 30, 41–43). Surprisingly, despite the conserved Rossmann fold, the conformational changes upon substrate binding are not conserved, but instead appear idiosyncratic among the class I aaRSs. The degree of reorganization in response to tRNA binding varies widely, from small local differences in TyrRS (30) to global movements of domains in IleRS (41) as well as tRNA-dependent active site assembly in GlnRS (44). Binding and recognition to tRNA by synthetases include interactions of amino acid side chains associating with nucleotide bases of the tRNA as well as the backbone functionalities precisely located in distinctive locations of the tRNA (45, 46).

Interestingly, the mutants investigated here show an inverse correlation between amino acid discrimination and aminoacylation efficiency for cognate tRNA. While enhanced amino acid specificity is observed with some mutants, these constructs display lower turnover of tRNA. This correlation may indicate that a specific conformational change is required to achieve both accurate amino acid activation and efficient tRNA aminoacylation. The mutations studied here appear to perturb the optimal balance between the two activities.

Conclusions

The studies reported here indicate that both K600 in hs mt LeuRS and L570 in its bacterial homologue E. coli have, through evolution, been strategically positioned and carefully chosen at these corresponding locations for maximum overall efficiency and balance in both amino acid discrimination and tRNA binding. An analogous situation exists for the discrimination between tyrosine and phenylalanine by tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS) where it is apparent that the WT enzyme has not reached the optimal level of discrimination between the two amino acids (47). In addition, E. coli glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase balances substrate specificity with catalytic efficiency (48), where the overall rate of aminoacylation is optimized by compromising between the various steps in the reaction pathway (48–50). It is clear that these biological catalysts have undergone optimization that values efficient and accurate aminoacylation that can only be achieved in some cases by trading off specificity and efficiency.

Supplementary Material

Includes relative kcat/Km for aminoacylation of tRNALeu(UUR)and tRNALeu(CUN) and relative kcat/Km for leucine and isoleucine as well as relative discrimination ratios for all LeuRSs. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

Acknowledgments

We thank David Tirrell (Caltech) for supplying us with E. coli LeuRS expression vectors. This work was supported by the NIH (R01 GM063890-01A2).

Financial support for this project was provided by the NIH (R01 GM063890-01A2).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: hs mt, human mitochondrial; tRNA, transfer ribonucleic acid; aaRS, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase; LeuRS, leucyl-tRNA synthetase; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; WT, wild type.

References

- 1.Lapointe J, Giegé R. Translation in Eukaryotes. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1991. Transfer RNAs and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribas de Pouplana L, Schimmel P. Formation of two classes of tRNA synthetases in relation to editing functions and genetic code. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quantum Biol. 2001;66:161–166. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2001.66.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibba M, Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fersht AR. Editing mechanisms in protein synthesis. Rejection of valine by isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 1977;16:1025–1030. doi: 10.1021/bi00624a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fersht AR. Sieves in sequence. Science. 1998;280:541. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Döring V, Mootz HD, Nangle LA, Hendrickson TL, de Crecy-Lagard V, Schimmel P, Marliére P. Enlarging the amino acid set of Escherichia coli by infiltration of the valine coding pathway. Science. 2001;292 doi: 10.1126/science.1057718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendrickson TL, Nomanbhoy TK, de Crecy-Lagard V, Fukai S, Nureki O, Schimmel P. Mutational separation of two pathways for editing by a class I tRNA synthetase. Mol Cell. 2002;9 doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu MG, Li J, Du X, Wang ED. Groups on the side of T252 in Escherichia coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase are important for discrimination of amino acids and cell viability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendrickson TL, Schimmel P. Transfer RNA-dependent amino acid discrimination by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. In: Lapointe J, Brakier-Gingras L, editors. Translation Mechanisms. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2003. pp. 34–64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schimmel P, Shepard A, Shiba K. Intron locations and functional deletions in relation to the design and evolution of a subgroup of class I tRNA synthetases. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1387–1391. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendrickson TL, Nomanbhoy TK, Schimmel P. Errors from selective disruption of the editing center in a tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8180–8186. doi: 10.1021/bi0004798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nureki O, Vassylyev DG, Tateno M, Shimada A, Nakama T, Fukai S, Konno M, Hendrickson TL, Schimmel P, Yokoyama S. Enzyme structure with two catalytic sites for double-sieve selection of substrate. Science. 1998;280:578–582. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt E, Schimmel P. Residues in a class I tRNA synthetase which determine selectivity of amino acid recognition in the context of tRNA. Biochemistry. 1995;34:11204–11210. doi: 10.1021/bi00035a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin L, Schimmel P. Mutational analysis suggests the same design for editing activities of two tRNA synthetases. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5596–5601. doi: 10.1021/bi960011y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JF, Guo NN, Li T, Wang ED, Wang YL. CP1 domain in Escherichia coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase is crucial for its editing function. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6726–6731. doi: 10.1021/bi000108r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mursinna RA, Lincecum TLJ, Martinis SA. A conserved threonine within Escherichia coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase prevents hydrolytic editing of leucyl-tRNALeu. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5376–5381. doi: 10.1021/bi002915w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mursinna RA, Martinis SA. Rational design to block amino acid editing of a tRNA synthetase. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7286–7287. doi: 10.1021/ja025879s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mursinna RA, Lee KW, Briggs JM, Martinis SA. Molecular dissection of a critical specificity determinant within the amino acid editing domain leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:155–165. doi: 10.1021/bi034919h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lincecum TL, Jr, Tukalo M, Yaremchuk A, Sproat BS, Eynde WVD, Link A, Calenbergh SV, Grotli M, Martinis SA, Cusack S. Structural and mechanistic basis of pre- and post-transfer editing by a leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:951–963. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang Y, Tirrell DA. Attenuation of editing activity of the Escherichia coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase allows incorporation of novel amino acids into proteins in vivo. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10635–10641. doi: 10.1021/bi026130x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhai Y, Martinis SA. Two conserved threonines collaborate in the Escherichia coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase amino acid editing mechanism. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15437–15443. doi: 10.1021/bi0514461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Liao J, Zhu B, Wang ED, Ding J. Crystal structures of the editing domain of Escherichia coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase and its complexes with Met and Ile reveal a lock-and-key mechanism for amino acid discrimination. Biochem J. 2006;394:399–407. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sohm B, Frugier M, Brulé H, Olszak K, Przykorska A, Florentz C. Towards understanding human mitochondrial leucine aminoacylation identity. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:995–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sampson JR, DiRenzo AB, Behlen LS, Uhlenbeck OC. Nucleotides in yeast tRNAPhe required for the specific recognition by its cognate synthetase. Science. 1989;243:1363–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.2646717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada N, Suzuki T, Wantanabe K. Dual mode recognition of two isoacceptor tRNAs by mammalian mitochondrial seryl-tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46770–46778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fender A, Sissler M, Florentz C, Giegé R. Functional idiosyncrasies of tRNA isoacceptors in cognate and noncognate aminoacylation systems. Biochimie. 2004;86:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serre L, Verndon G, Choinowski T, Hervouet N, Risler JL, Zelwer C. How methionyl-tRNA synthetase creates its amino acid recognition pocket upon L-methionine binding. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:863–876. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newberry K, Hou YM, Perona JJ. Structural origins of amino acid selection without editing by cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase. EMBO J. 2002;21:2778–2787. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delagoutte B, Moras D, Cavarelli J. tRNA aminoacylation by arginyl-tRNA synthetase: induced conformations during substrate binding. EMBO J. 2000;19:5599–5610. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yaremchuk A, Kriklivyi I, Tukalo M, Cusack S. Class I tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase has a class II mode of cognate tRNA recognition. EMBO J. 2002;21:3829–3840. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ilyin VA, Temple B, Hu M, Li G, Yin Y, Vachette P, Carter CWJ. 2.9A crystal structure of ligand-free tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase: domain movements fragment the adenine nucleotide binding site. Protein Sci. 2000;9:218–231. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cusack S, Yaremchuk A, Tukalo M. The 2A crystal structure of leucyl-tRNA synthetase and its complex with a leucyl-adenylate analogue. EMBO J. 2000;19:2351–2361. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson D, Plateau P, Simonson T. Free-energy simulations and experiments reveal long-range electrostatic interactions and substrate-assisted specificity in an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Chem Bio Chem. 2006;7:337–344. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang CM, Perona JJ, Hou YM. Amino acid discrimination by a highly differentiated metal center of an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10931–10937. doi: 10.1021/bi034812u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wittenhagen LW, Kelley SO. Dimerization of a pathogenic human mitochondrial tRNA. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:586–590. doi: 10.1038/nsb820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bullard JM, Cai YC, Spremulli LL. Expression and characterization of the human mitochondrial leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1490:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fersht AR, Ashford JS, Bruton CJ, Jakes R, Koch GLE, Hartley BS. Active site titration and aminoacyl adenylate binding stoichiometry of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Biochemistry. 1975;14:1–4. doi: 10.1021/bi00672a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lue SW, Kelley SO. An aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase with a defunct editing site. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3010–3016. doi: 10.1021/bi047901v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tukalo M, Yaremchuk A, Fukunaga R, Yokoyama S, Cusack S. The crystal structure of leucyl-tRNA synthetase complexed with tRNALeu in the post transfer-editing conformation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;10:923–930. doi: 10.1038/nsmb986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnez JG, Moras D. Structural and functional considerations of the aminoacylation reaction. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:211–216. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silvian LF, Wang J, Steitz TA. Insights into editing from an Ile-tRNA synthetase structure with tRNAIle and mupirocin. Science. 1999;285:1074–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sekine S, Nureki O, Shimada A, Vassylyev DG, Yokoyama S. Structural basis for anticodon recognition by discriminating glutamyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:203–206. doi: 10.1038/84927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uter NT, Perona JJ. Active-site assembly in glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase by tRNA-mediated induced fit. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6858–6865. doi: 10.1021/bi052606b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherlin LD, Perona JJ. tRNA-dependent active site assembly in a class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Structure. 2003;11:591–603. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McClain WH, Schneider J, Bhattacharya S, Gabriel K. The importance of tRNA backbone-mediated interactions with synthetase for aminoacylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:460–465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perona JJ, Rould MA, Steitz TA. Structural basis fro transfer RNA aminoacylation by Escherichia coli glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8758–8771. doi: 10.1021/bi00085a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Prat Gay G, Duckworth HW, Fersht AR. Modification of the amino acid specificity of tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase by protein engineering. FEBS Lett. 1993;318:167–171. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80014-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sherman JM, Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases optimize both cognate tRNA recognition and discrimination against noncognate tRNAs. Biochemistry. 1996;35:601–607. doi: 10.1021/bi951602b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Avis JM, Day AG, Garcia G, Fersht AR. Reaction of modified and unmodified tRNATyr substrates with tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (Bacillus stearothermophilus) Biochemistry. 1993;32:5312–5320. doi: 10.1021/bi00071a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Avis JM, Fersht AR. Use of binding energy in catalysis: Optimization of rate in a multistep reaction. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5321–5326. doi: 10.1021/bi00071a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Includes relative kcat/Km for aminoacylation of tRNALeu(UUR)and tRNALeu(CUN) and relative kcat/Km for leucine and isoleucine as well as relative discrimination ratios for all LeuRSs. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org