Abstract

Cyclin G1 was identified as a transcriptional target of p53 that encodes a protein with strong homology to the cyclin family of cell cycle regulators. We show that either ectopically expressed or endogenous cyclin G1 protein is very unstable, undergoes modification with ubiquitin and is likely degraded by the proteasome. Ectopic cyclin G1 protein stability is increased by cyclin box mutation or by association with inactive cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) subunits, suggesting that a function of cyclin G1 as a CDK regulator may be required for its rapid turnover. Further, cyclin G1 and the cyclin box mutant interact with and are ubiquitinated by MDM2, another transcriptional target of p53, that acts as a negative regulator of p53 stability. These data suggest that the cyclin box has a role in the proteasome-mediated degradation of cyclin G1 and thus suggest a putative role for a CDK in cyclin G1 metabolism and function.

Keywords: cyclin G1, CDK, p53, MDM2, ubiquitination

INTRODUCTION

The importance of the p53 pathway in suppression of tumorigenesis is exemplified by the fact that it is impaired in virtually all human cancers (1). Neoplasias in which p53 itself is not mutated often sustain mutations in genes that regulate p53 accumulation, thus indirectly reducing p53 function (2). p53 is normally expressed at low levels in proliferating cells, but in response to both intrinsic and extrinsic cellular stresses, the half-life of the p53 protein is increased from 6−20 minutes to hours (3). Three ubiquitin ligases are known to regulate the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the p53 protein, MDM2 (HDM2), Pirh-2 and Cop-1 (4). Most of the tumor suppressor functions of p53 lie in its ability to bind DNA and regulate the expression of a set of target genes, some of which are involved in cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, cellular senescence and apoptosis (3). Of these, p21CIP1 is the best characterized regulator of proliferation. The ability of p21CIP1 to inactivate cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) function is clearly important in mediating p53's growth suppressive properties (5). Nevertheless, p21CIP1 cannot totally account for p53's function as a cell cycle regulator, since cells from p21CIP1-null mice retain some ability to arrest in G1 following DNA damage, a trait lost after deletion of p53 (6).

The strict regulation of p53 activity is achieved through a number of positive and negative feedback loops. Another well-characterized p53 target, MDM2, functions as an oncogene when overexpressed, consistent with its role as a negative regulator of p53 (7). MDM2 can bind to p53 and block its ability to activate transcription and can also promote its ubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation (8). MDM2 has a C-terminal RING-finger protein domain that is required for its ability to function directly as an E3 ubiquitin-ligase (9). MDM2 may act to either monoubiquitinate or polyubiquitinate p53 (10). The polyubiquitination of p53 by MDM2 is a signal for degradation of p53 by proteasomes in the nucleus whereas monoubiquitination results in nuclear export and subsequent destruction in the cytoplasm (11). These processes result in a feedback mechanism to limit p53 activity. A further level of regulation is provided by the nucleolar protein p19ARF (ARF; p14 in human), a key mediator of oncogene-activated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (12). ARF physically interacts with MDM2 and antagonizes its ability to negatively regulate p53.

Cyclin G1 is a major transcriptional target of p53 whose role is still not completely understood (13, 14). Cyclin G1 has been categorized as a cyclin because it contains a region of protein sequence homology, the cyclin box, common to all members of the cyclin family of cell cycle regulators (15). Cyclins are dependent on the cyclin box to associate with specific kinase partners CDKs and regulate their kinase activity during the cell cycle (16). The p53-responsiveness of cyclin G1 is well documented. At the transcriptional level, cyclin G1 is one of the most highly induced genes in response to DNA damage (17, 18). However, no functional CDK partner has been identified for cyclin G1 to date.

Cyclin G1 has been found in complex with a number of proteins that are involved in cell cycle regulation. Cyclin G1 has been shown to interact with GAK (cyclin G-associated kinase) and CDK5, although the physiological significance of these interactions remains unclear (19). Interaction of cyclin G1 with tumor suppressor proteins, such as p53, p73 and ARF has been reported, although whether the binding of these proteins is direct is contentious (20, 21). Okamoto et al., demonstrated an association of cyclin G1 with 2 regulatory subunits of protein phosphatase 2A (22). Indeed, cyclin G1, as well as cyclin G2, associates with MDM2 and the active PP2A trimeric complex (21, 23-25). Even though cyclin G2 is not p53-responsive, the fact that cyclin G2 is able to form similar complexes suggests that it may be able to compensate for cyclin G1 loss, perhaps contributing to the minimal phenotype of cyclin G1 knockout animals.

Although mice lacking cyclin G1 protein expression develop normally, cells derived from these mice have proven useful in uncovering the function of cyclin G1 (26, 27). Cyclin G1-null cells exhibit growth retardation after DNA damage, an abnormal G2/M arrest, decreased survival and altered kinetics of p53 accumulation (24, 26, 27). Despite some contradictory findings, the preponderance of evidence seems to support a role for cyclin G1 in growth promotion rather than arrest. Indeed, cyclin G1-deficient mice have decreased tumor incidence, size and malignancy (27). This result is in accordance with reports of cyclin G1 overexpression in cancer (28-30). Ectopic overexpression of cyclin G1 has also been reported to accelerate cell proliferation (31-33).

The observation that cyclin G1 stimulates the dephosphorylation of MDM2 at T216 through its association with enzymatically active PP2A (23) supports a proproliferative role for cyclin G1. Dephosphorylation of MDM2 at T216 results in increased complex formation between MDM2 and p53 and subsequent degradation of p53. Further, it has been shown that cyclin G1-null MEFs have increased p53 levels and an increase in MDM2 phosphorylation at T216 (23, 27). These data suggest that cyclin G1 is yet another component of the feedback regulation of p53 abundance.

Despite the progress in understanding the role of cyclin G1 as a p53 mediator, little is known about the post-transcriptional regulation of this protein, or about the role of cyclin G1's conserved cyclin box domain. Here, we report that cyclin G1 is subject to MDM2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation that can be inhibited by ARF. The cyclin box domain of ectopically expressed cyclin G1 plays an important role in localization and degradation, but not ubiquitination, of cyclin G1, suggesting that functional CDK interaction may regulate this target of p53 in normal and tumor cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and plasmids

U2OS, MRC5, WI38, C2C12 and A1−5 cells were maintained in DMEM (JRH Biosciences), 10% FBS and 100 units/ml pen/strep (Gibco/BRL) at 37°C, 5% CO2. NIH-3T3 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% calf serum with antibiotics, Saos2 cells in DMEM with 15% FBS. U2OS cells were transfected using BBS and calcium chloride. For induction of p53 in A1−5 cells, 500K cells were plated per 10-cm dish and incubated at 37°C for 12 hours. The cells were shifted to 32°C for 36 hours before harvesting.

Human cyclin G1 was a gift from Alan Wahl and was sub-cloned into the CMVNeoBam vector. Murine cyclin G1 was expressed using the pCDNA3 vector (Invitrogen). The K106R and K106D mutants and Flag-tagged versions were generated by PCR and sequenced. The MDM2 expression plasmid was a generous gift of Arnold Levine and the HA-tagged ubiquitin construct and MDM2-ΔRING were kindly provided by Carl Maki. p19ARF was a gift from Karl Munger and p14ARF was kindly provided by Martine Roussel. CDK2 and dnCDK2 were provided by Sander van den Heuvel. CDK5 and dnCDK5 were both generous gifts of Li-Huei Tsai.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Lysis, immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed essentially as described (34). The following primary antibodies were used: Flag (M2, Sigma), cyclin G1 (H-46, Santa Cruz), CDK2 (M2, Santa Cruz), CDK5 (C8, Santa Cruz), tubulin (Ab-1, Oncogene), HA (supernatant from clone12CA5) and MDM2 (smp-14, santa cruz). HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) were diluted 1:10,000 or 1:5000 in TNET and detected by ECL (NEN).

Half-life experiments

Cycloheximide (CHX: Sigma) was prepared in 100% ethanol and used at a final concentration of 50μg/ml. For half-life experiments in transfected U2OS cells, a single transfected 10-cm dish was trypsinized and plated in 5 wells of a 6-well dish. Medium containing CHX was added and incubated for the indicated timepoints before harvest. For 3T3 experiments, cells were grown for 24 hours at 37°C and treated with a final concentration of 0.2 ng/ml doxorubicin (Calbiochem) for 12−24 hours before addition of CHX. MG-132 (Peptides International) and Lactacystin (Calbiochem) were reconstituted in DMSO and added to cell cultures at a final concentration of 25μM and 10μM respectively one hour prior to addition of CHX.

For pulse-chase experiments, cell cultures were washed with PBS and incubated in methionine-free medium supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS for one hour. The medium was removed and 2 mls of fresh methionine-free medium was added containing 250μCi of 35S-methionine (NEN) per ml. Cells were labeled for one hour. After washing with PBS, chase medium was added (DMEM plus 10% FBS supplemented with 15μg/ml cold methionine) and samples were harvested. Lysates were precleared using rabbit immunoglobulin prebound to S. aureus cells for 1 hour at 4°C. IPs were performed as described using an agarose-conjugated Flag antibody (M2, Sigma) and separated by SDS-PAGE. Quantitation of bands was performed using ImageJ.

Indirect immunofluorescence

Cells were plated onto glass coverslips 24 hours following transfection and fixed ∼24 hours later in 4% PFA/PBS and permeabililzed with 0.1% TritonX-100 in PBS. Coverslips were blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBS and incubated with primary antibody for 1 hour at RT. Antibodies used were: CDK5 (J3), cyclin G1 (C-18) and fibrillarin (AFBO1, Cytoskeleton). Coverslips were washed 3 times, immunolabeled with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit, 488 goat anti-mouse; Molecular Probes) and stained with bisbenzimide (Hoechst). Images were collected on a Leica SP2 laser scanning confocal microscope.

Cell synchronization and irradiation

U2OS cells were synchronized by double thymidine block. Briefly, cells were plated at 500K per 10-cm dish and allowed to grow overnight. The cells were treated with excess thymidine (2mM; Sigma) for 17 hours, washed and allowed to recover for 9 hours before readdition of thymidine (2mM). The cells were infected with adenovirus for 10 hours following the second thymidine treatment and released from the thymidine block 4 hours later. The cells were exposed to 6 Gy γ-irradation from a 60Co gamma ray source (U.S. Nuclear) 2 hours after release from thymidine block and harvested for flow cytometry 24 hours later.

Generation of adenovirus

Wild-type cyclin G1 and the KD mutant were cloned into the pAdTrack-CMV shuttle vector and this was cotransformed with an adenoviral backbone plasmid (pAdEasy) by electroporation into electrocompetent BJ5183 E. coli cells. Recombinants were selected using kanamycin and confirmed by restriction digest. Recombinant plasmids were linearized and transfected into the packaging cell line (293) using Fugene (Roche) per manufacturer's instructions.

Flow Cytometry analysis

Medium was collected and cells were washed with PBS followed by PBS+0.1% EDTA. Cells were dislodged from the plate by incubation with PBS+0.1%EDTA. All cells were pooled and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1600rpm. The pellet was resuspended and washed twice in PBS supplemented with 1% calf serum and 0.1% sodium azide. Fixation was achieved by mixing the cell suspension dropwise into 90% ethanol (−20°C) while vortexing. For DNA staining, the cells were pelleted and resuspended in a solution of propidium iodide (20μg/ml) and RNAse A (200μg/ml). DNA content was measured using a Becton-Dickinson FACScan with CellQuest software and analyzed using ModFit.

RESULTS

Cyclin G1 is an unstable protein

The homology between cyclin G1 and known cyclins suggests that cyclin G1 may activate a cyclin dependent kinase (CDK). In effort to uncover a CDK-activating role for cyclin G1, we mutated a conserved lysine residue in murine cyclin G1 (K106) analogous to a residue in cyclin D1 that is necessary for activating, but not binding, a CDK partner ((34) and our unpublished observations). This residue is predicted from the cyclin A/CDK2 structure to form contacts that allow the proper orientation of ATP in the active site of the enzyme complex (35). We created both a non-conservative mutation of lysine to aspartic acid and a conservative mutation to arginine, an amino acid that naturally exists at this position in cyclin F and cyclin G2. Upon transfection of these constructs into U2OS cells, we observed an alteration in the mobility of K106D (KD) as compared to the wild-type or K106R (KR). Additionally, we noted a substantial increase in the steady-state level of the KD mutant, suggesting an increase in protein stability. The instability of cyclin G1 was not predicted by its sequence as it encodes neither a PEST sequence nor a destruction box motif found in mitotic cyclins (36).

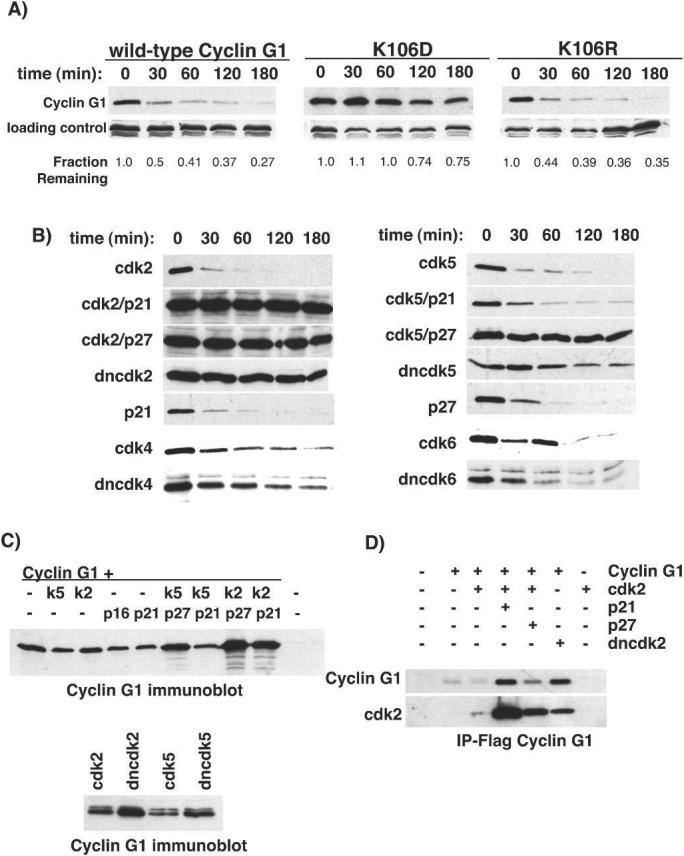

The half-lives of the wild-type and mutant cyclin G1 proteins were determined by treating transfected U2OS cells with cycloheximide (Fig. 1A). Wild-type cyclin G1 and the KR mutant both had half-lives between 15 and 20 minutes, whereas the KD mutant had a half-life 3−4 fold longer. Similar results were obtained by pulse-chase analysis (data not shown). Thus, the instability of cyclin G1 depends at least in part on the integrity of the cyclin box, suggesting that cyclin G1 degradation depends on CDK activation or association as has been seen with other cyclins (37-39). We observed that the half-life of cyclin G1 was also dependent on the functional integrity of cotransfected CDKs (Fig. 1B). Co-expression of dominant-negative CDK2 or CDK5 with cyclin G1 in U2OS cells resulted in a substantial increase in the half-life of cyclin G1, whereas the half-life of cyclin G1 coexpressed with wild-type CDK2 or CDK5 remained short. Neither wild-type nor inactive versions of CDK4 or CDK6 seemed to have a profound effect on cyclin G1 stability. We found that in U2OS cells, the CDK inhibitor p27KIP1 could stabilize cyclin G1 when coexpressed with CDK2 or CDK5, and that p21CIP1 could stabilize cyclin G1 in combination with CDK2 (Figs. 1B,C). The steady state level of cyclin G1 was also increased by dnCDKs in the p53-deficient Saos2 cell line (Fig. 1C). The inhibitors p21CIP1, p27KIP1 or p16INK4a were not able to stabilize cyclin G1 when expressed alone. This suggests that cyclin G1 is stabilized under conditions in which it may be confined in an inactive complex and not as a result of altered cell cycle profile of transfected cells or by cell cycle arrest. Intriguingly, wild-type cyclin G1, but not the KD mutant was found to be phosphorylated in vivo, consistent with a putative autoregulatory function of cyclin G1 (Fig. S1A). Furthermore, using a baculovirus expression system, we detected a CKI-inhibitable kinase activity that coprecipitated with wild-type cyclin G1, but not the KD mutant (Fig. S1B). The nature of this activity remains to be identified.

Figure 1.

Half-life of exogenous cyclin G1 and mutants. A, U2OS cells were transfected with wild-type cyclin G1 or the mutants KD or KR. Cells were treated with cycloheximide (50μg/ml) for the indicated times to determine protein half-life. The images shown are representative examples. The experiments were performed at least three times and quantitated using NIH-image software. B, Wild-type cyclin G1 was cotransfected with either functional or dominant negative (dn) isoforms of CDK2, CDK4, CDK5 or CDK6 and in combination with the CDK inhibitors p21CIP1 and p27KIP1. The transfected cells were treated with cycloheximide and blotted for cyclin G1 to assess half-life. C, top panel: U2OS cells transfected with cyclin G1 and combinations of CDKs and CKIs and blotted for steady state levels. Bottom panel: steady-state levels of cyclin G1 protein in Saos2 cells cotransfected with wt and dn forms of CDK2 or CDK5. D, U2OS cells were transfected with the indicated expression vectors, lysates were immunoprecipitated with Flag antibodies and blots were probed for CDK2 or Flag-cyclin G1.

We next assayed the ability of cyclin G1 to bind CDK 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that cyclin G1 was able to interact with all of the kinases tested, including dominant-negative versions. An example experiment with CDK2 is shown in Figure 1D (others are shown in Figs. S2A, S2B and S2C). The levels of cyclin G1 were increased upon coexpression of dnCDK2 or the CDK inhibitors p21CIP1 or p27KIP1, resulting in increased coimmunoprecipitation of CDK2. However, no activity was detected in in vitro kinase assays using histone H1 and GST-Rb (C-terminus) as substrates (data not shown). We cannot rule out the possibility that cyclin G1 can activate these kinases, but acts on an undetermined substrate.

We next considered the possibility that cyclin G1 may act as a negative regulator of other cyclins. However, overexpression of cyclin G1 does not interfere with the associated kinase activities of either cyclin E or p35 (Figs. S2D and E). Further, we found no cell cycle effect of cyclin G1 overexpression by either transient transfection or adenoviral expression in any normal or tumor cell line as analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. S3A). These data are consistent with reports by others (13, 40). However, we did detect abnormal nuclei in some cyclin G1 overexpressing cells similar to those described for cyclin G2 overexpressing cells (data not shown and (25)). Overall, it seems unlikely that cyclin G1 negatively regulates cyclin-CDK complexes required for cell cycle progression under routine culture conditions. Thus, although a specific CDK partner and activity of cyclin G1 remains to be identified, functional association with such a kinase may contribute to cyclin G1's markedly short half-life.

Endogenous cyclin G1 induced by p53 is also unstable

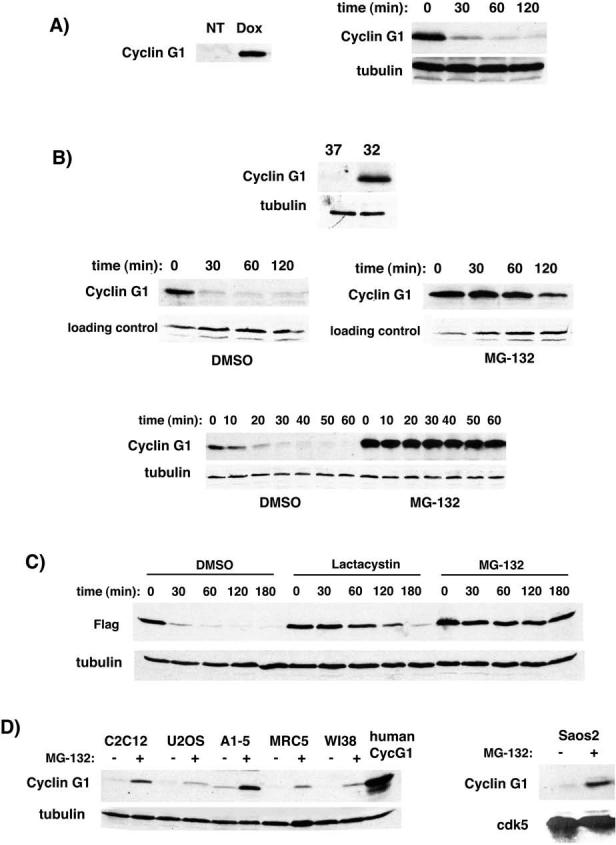

Since exogenous cyclin G1 was unstable in U2OS cells, we asked if the endogenous protein was equally labile. We treated NIH-3T3 cells with doxorubicin to induce p53 and cyclin G1 and the resulting increase in cyclin G1 protein level is apparent (Fig. 2A, left panel). We found that the stability of the endogenous protein was similar to that of the exogenous protein in U2OS cells (Fig. 2A, right panel).

Figure 2.

Stabilization of exogenous and endogenous cyclin G1 protein by proteasome inhibitors. A, Endogenous cyclin G1 in NIH-3T3 cells was induced by treatment with doxorubicin (0.2μg/ml). Determination of induced cyclin G1 half-life in doxorubicin-treated 3T3 cells by cycloheximide as in Figure 1. B, Endogenous cyclin G1 protein is induced in A1−5 cells (ts-p53) at 32°C. A1−5 cells at 32°C were treated with DMSO or the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (25μM) 1 hour prior to addition of cycloheximide and harvested at the indicated timepoints to determine protein half-life. In this experiment the level of cyclin G1 was assayed at both long (middle panels) and short (bottom panel) time-points after addition of cycloheximide. C, U2OS cells were transfected with Flag-tagged cyclin G1 and treated with DMSO, Lactacystin (10μM) or MG-132 (25μM) for 1 hour before addition of cycloheximide. Cells were harvested at the indicated timepoints for half-life determination. Immunoblots were probed with anti-Flag antibodies. Tubulin is shown as a control. D, Various human, rat and mouse cell lines were treated with DMSO or MG-132 (10μM) for 4 hours. Lysates were blotted for cyclin G1 using an N-terminal antibody (santa cruz H-46). Transfected human cyclin G1 was run alongside as a control for blotting and a marker for migration. Rat cyclin G1 was observed to migrate slightly ahead of human and murine. Tubulin is shown as a control. Saos2 cells (p53-negative) were treated as described above. Lysates were blotted for cyclin G1 and CDK5 as a control. (right panel)

We also examined endogenous cyclin G1 protein in the A1−5 rat fibroblast cell line. A1−5 cells express a temperature-sensitive allele of murine p53, val135 (41). In these cells, p53 is inactive at 37°C, but assumes a wild-type conformation at 32°C, activates transcription of target genes and arrests cells in G1 phase. Cyclin G1 protein is barely detectable at the nonpermissive temperature, but is abundant at 32°C (Fig. 2B, top panel). When A1−5 cells maintained at 32°C for 36 hours were treated with cycloheximide, the cyclin G1 protein was short-lived (Fig. 2B: left middle panel, long time course; bottom panel, short time course). Although p53 increases the level of cyclin G1 transcript, it does not appear to create a stabilizing environment for the cyclin G1 protein in either A1−5 or 3T3 cells. Furthermore, cyclin G1 stability does not correlate with proliferative state, since there is no difference in the half-life of cyclin G1 in proliferating transfected U2OS cells compared to that in p53-arrested NIH-3T3 or A1−5 cells.

Inhibitors of the proteasome stabilize exogenous and endogenous cyclin G1 protein

As degradation of numerous proteins is dependent on the activity of proteasomes, we tested whether the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 could prevent the rapid destruction of cyclin G1. Treatment of A1−5 cells at 32°C with MG-132 resulted in a substantial increase in the stability of cyclin G1 in comparison to the DMSO treated control (from ∼20 minutes to ∼2 hours; Fig. 2B). A similar response of cyclin G1 to MG-132 was observed in transfected U2OS cells (Fig. 2C), suggesting cyclin G1's short half-life is proteasome-dependent. However, since MG-132 inhibits thiol proteases in addition to the proteasome complex, we tested whether a specific inhibitor of the proteasome, lactacystin, was also capable of extending the half-life of transfected cyclin G1 in U2OS cells. Comparable with the effect of MG-132, lactacystin also increased the half-life of cyclin G1 from 15−20 minutes to nearly 2 hours (Fig. 2C).

In order to test whether proteasome inhibitors could increase the levels of endogenous cyclin G1 in undamaged cells, we treated a variety of cell lines with MG-132 and observed a consequent increase in cyclin G1 protein (Fig. 2D). The cells used in this study were C2C12 murine myoblasts, U2OS human osteosarcoma cells, A1−5 (ts-p53) rat fibroblasts cultured at the nonpermissive (37°C) temperature and the human diploid fibroblast cells, MRC5 and WI38. All of these cell lines express wild-type p53 protein. As p53 is also stabilized by inhibition of the proteasome, we cannot discount the possibility that stabilization of p53 results in increased transcription of cyclin G1, and hence an increase in protein. However, A1−5 cells produce high levels of dominant-negative mutant p53 at 37°, likely inactivating wild-type p53 through oligomerization, rendering the cells effectively p53-deficient. To test this p53-independent increase more directly, we examined the endogenous cyclin G1 protein in Saos2 cells that lack p53. MG-132 treatment increases cyclin G1 protein in Saos2 cells, supporting a role for proteasome-mediated degradation in controlling steady-state levels of cyclin G1 (Fig. 2D, right panel). We conclude that the short half-life of basal and induced endogenous cyclin G1, as well as that produced ectopically, is dependent on proteasome activity.

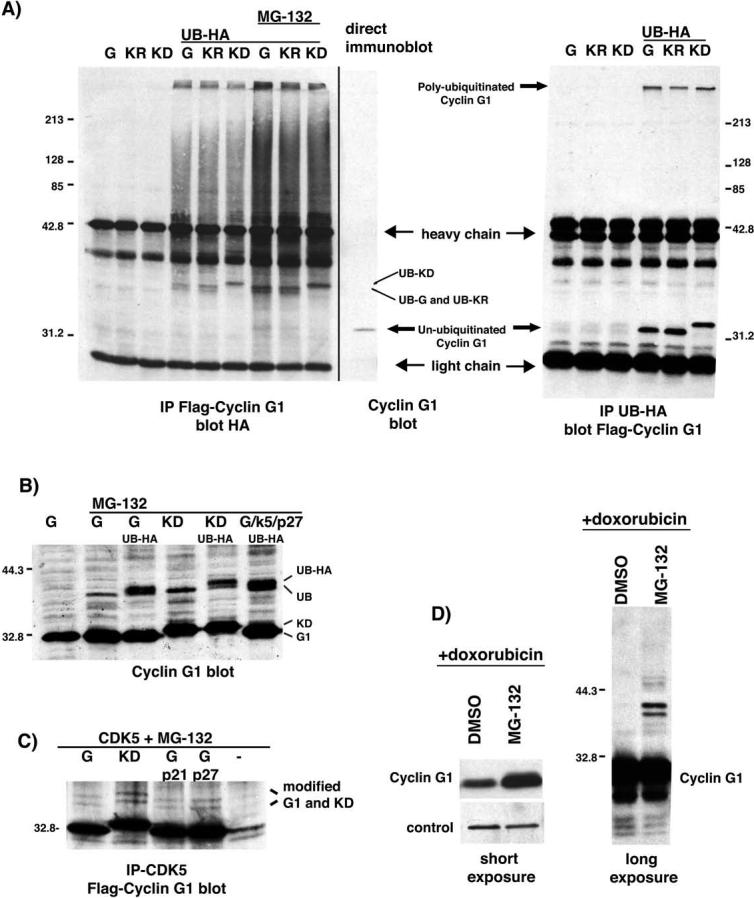

Ubiquitination of cyclin G1 in U2OS cells

The proteasome-dependent degradation of cyclin G1 suggested that it was likely to be a direct target of the ubiquitination machinery. To confirm this, Flag-tagged wild-type cyclin G1, KR and KD were transfected into U2OS cells, both in the presence and absence of HA-tagged ubiquitin. When cyclin G1 was immunoprecipitated, anti-HA reactive bands and smears of high molecular weight material likely to be polyubiquitinated cyclin G1 were detected in the presence, but not the absence, of HA-ubiquitin (Fig. 3A, left panel). Consistent with the degradation of ubiquitinated cyclin G1 by the proteasome, the intensity of these bands was enhanced by treating the cells with MG-132. In a similar experiment, HA antibodies were used to IP the tagged ubiquitin and blots were probed for Flag-cyclin G1 (Fig. 3A, right panel). Flag reactive bands are present at the top of the gel in the presence of HA-tagged ubiquitin, indicating polyubiquitinated cyclin G1 and mutants. Unmodified cyclin G1 is also detected, indicating that it is being immunoprecipitated through interaction with another ubiquitinated protein. We hypothesize that the reason monoubiquitinated and intermediate forms of cyclin G1 are not detected in this blot is likely due to the large number of cellular proteins that are ubiquitinated, such that the HA antibody is limiting.

Figure 3.

Ubiquitination of exogenous and endogenous cyclin G1 and mutants. A, left panel: U2OS cells were transfected with Flag-tagged wild-type cyclin G1, KR and KD with and without HA-tagged ubiquitin (UB-HA) as indicated. Extracts in lanes 1−6 were from cells treated with DMSO and lanes 7−9 from cells treated with MG-132. Cyclin G1 was immunoprecipitated using the Flag antibody and the immunoprecipitates were probed for the presence of UB-HA. Monoubiquitinated forms of wt cyclin G1, R and KD are indicated. The last lane is a direct immunoblot of transfected Flag-tagged wild-type cyclin G1. Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. Right panel: Similar experiment as seen on the left except HA-tagged ubiquitin is immunoprecipitated and the blot is for Flag-tagged cyclin G1. Polyubiquitinated cyclin G1 and un-ubiquitinated cyclin G1 are indicated. B, Direct immunoblot of transfected untagged wt cyclin G1 and KD in the presence and absence of MG-132 and UB-HA in U2OS cells. Wild-type cyclin G1 is also shown in the presence of CDK5 and p27KIP1. C, Immunoprecipitations of CDK5 from MG-132 treated U2OS cells blotted for Flag-cyclin G1. Modified forms of cyclin G1 and KD coimmunoprecipitating with CDK5 in the presence and absence of p21 and p27 are indicated. D, NIH-3T3 cells were treated with doxorubicin to induce endogenous cyclin G1 followed by addition of MG-132 or DMSO for 4 hours. The left panel is a short exposure of a cyclin G1 immunoblot (S.Cruz H-46) demonstrating the increase in cyclin G1 protein with MG-132. The right panel is a long exposure of the same blot, revealing higher molecular weight bands.

In direct immunoblots, a higher molecular weight cyclin G1-reactive band appears when the cells are treated with MG-132 (Fig. 3B), consistent with the addition of a single ubiquitin molecule to cyclin G1. The coexpression of tagged ubiquitin converts this single band to a doublet in cells expressing either cyclin G1 or KD. These experiments have been performed with different antibodies and tags with the same result (data not shown). Modified forms of cyclin G1 and KD are also seen in complex with CDK5 in the presence of MG-132 (Fig. 3C). Coexpression of p21CIP1 or p27KIP1 does not alter this ubiquitination. In fact, the modified forms are increased in the presence of KD or cyclin G1/CDK5/p27KIP1, just as the steady state levels and half-lives of cyclin G1 are increased for these combinations of proteins. Collectively with proteasome-dependent degradation of cyclin G1, these data strongly suggest that transfected cyclin G1 is a direct ubiquitin-dependent substrate of the proteasome. Further, long exposure of DNA-damage induced, MG-132 treated endogenous cyclin G1 shows the presence of slower migrating bands consistent with addition of ubiquitin (Fig. 3D). The stabilized bands that react with the cyclin G1 antibody are present as doublets (Figs. 3C and D), indicating that the cyclin G1 protein probably undergoes other modifications in addition to ubiquitination. The nature of these modifications is currently under investigation. Interestingly, despite profound differences in cyclin G1 half-life, there is no apparent difference in the level of ubiquitination of wild-type cyclin G1 and KD. Hence, mutation of the conserved lysine does not inhibit ubiquitination of cyclin G1.

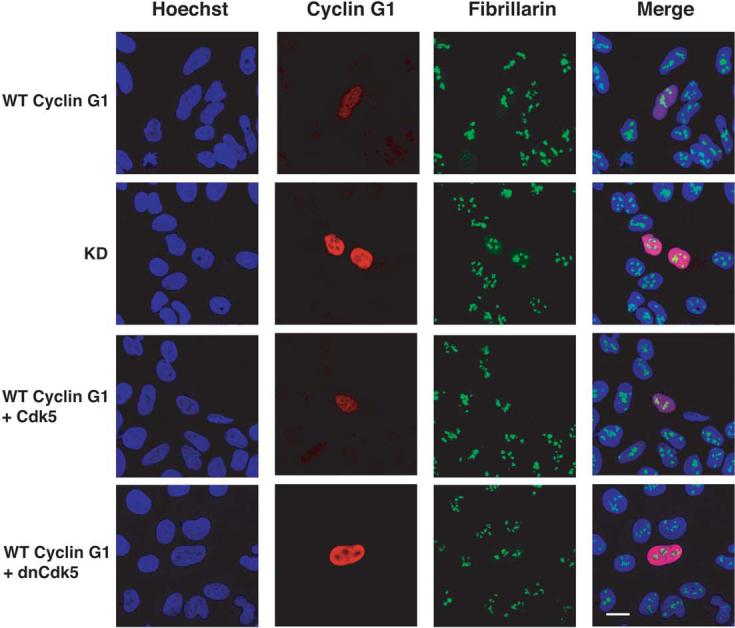

Cyclin G1 cellular localization may regulate its stability

In an attempt to understand why complex formation with inactive CDKs or a nonconservative mutation of lysine 106 altered the half-life, but not the ubiquitination of cyclin G1, we examined the cellular distribution of KD and wild-type cyclin G1 in the presence and absence of excess CDK using confocal microscopy. Wild-type cyclin G1 transfected alone or with active CDK was distributed throughout the nucleus (Fig. 4). The staining appeared largely homogeneous, but was occasionally punctuated with small bright foci. A similar pattern was seen by immunostaining wild-type MEFs cells treated with DNA-damaging agents to induce endogenous cyclin G1 (Fig. S4). The KD mutant also localized to the nucleus, but lacked focal staining and was notably excluded from large subnuclear regions. Immunolabeling of these cells with the fibrillarin antibody indicated that these regions are nucleoli. Interestingly, the cyclin G1 protein stabilized by inactive kinase also appeared to be excluded from these regions of the nucleus (Fig. 4). Cyclin G1 cotransfected with CDK5 and p27KIP1 also showed this phenotype, whereas cyclin G1 cotransfected with CDK5 and p21CIP1, or either inhibitor alone, did not (Fig. S5). Further, the increase in steady state levels of cyclin G1 seen by immunoblot is also evident by immunofluorescence.

Figure 4.

Subcellular localization of transfected wild-type cyclin G1 and KD in U2OS cells. U2OS cells were transfected with wild-type cyclin G1 and KD and immunostained for cyclin G1 and fibrillarin, a marker of the nucleolus. Hoechst was used as a counterstain. Wild-type cyclin G1 was also cotransfected with functional and dominant-negative CDK5. The panels show cells stained for cyclin G1, fibrillarin and a merged image. The expression of CDK5 was confirmed by immunofluorescence. No effect on the localization of either CDK5 isoform was observed in the presence of cyclin G1.

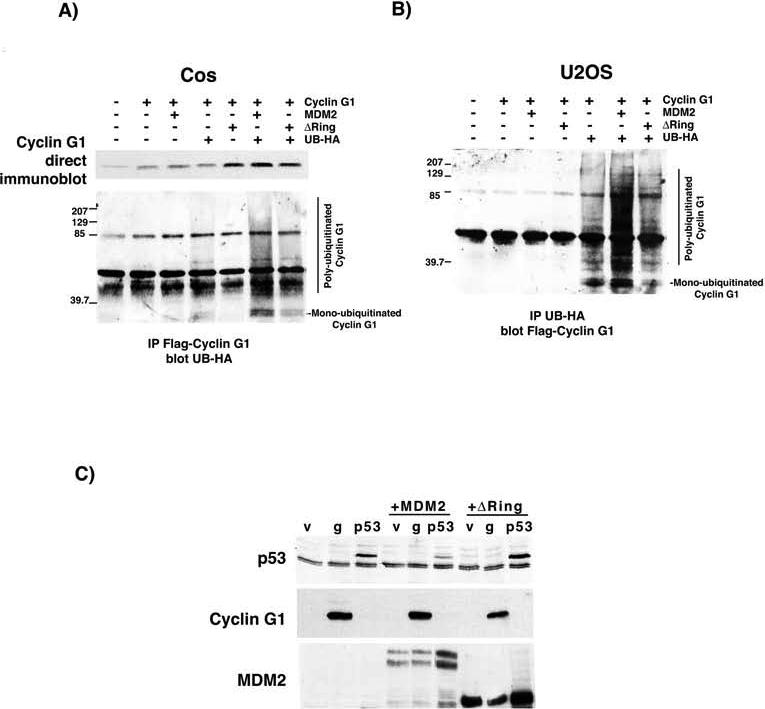

Ubiquitination of cyclin G1 is enhanced by MDM2

A direct physical association between cyclin G1 and the MDM2 ubiquitin ligase has been demonstrated by a number of groups (21, 23, 24). Indeed we were readily able to confirm this observation using extracts of A1−5 cells expressing endogenous cyclin G1 and MDM2 (Fig. S6). To test for an ability of MDM2 or an ubiquitination-deficient version (ΔRing) (9, 42-44) of MDM2 to modify cyclin G1, both Cos and U2OS cells were cotransfected with tagged cyclin G1 and either MDM2 or ΔRing , and modification of cyclin G1 was assessed by immunoblot. Overexpression of MDM2 resulted in the generation of slower migrating species of cyclin G1, consistent with MDM2-mediated ubiquitination of cyclin G1 (Figs. 5A and B). Expression of the ΔRing mutant resulted in a reduced level of both poly- and monoubiquitinated cyclin G1 in both cell lines when compared to wild-type MDM2. Interestingly, in our hands, the expression of MDM2 did not result in diminution of cyclin G1 levels as it does with p53 (Fig. 5C), once again indicating that polyubiquitination of cyclin G1 is not sufficient to increase degradation.

Figure 5.

The enhanced ubiquitination of cyclin G1 by MDM2 is affected by deletion of the Ring domain. A, Cos cells were transfected with Flag-tagged cyclin G1 alone or with MDM2 or an MDM2 mutant lacking the Ring domain (ΔRing), in the presence and absence of HA-tagged ubiquitin. Lysates were blotted directly for cyclin G1 or immunoprecipitated with Flag antibodies and blotted for HA-tagged ubiquitin. High molecular weight HA-reactive bands as well as monoubiquitinated cyclin G1 are seen with cotransfection of MDM2 only in the presence of both HA-ubiquitin and Flag-cyclin G1, and are reduced by deletion of the Ring domain. B, The reverse immunoprecipitation is shown in cell lysates from U2OS cells with a similar result. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies and blotted for Flag-cyclin G1. C, U2OS cells were transfected with p53 or cyclin G1 alone or in combination with MDM2 or ΔRing, and immunoblotted for p53, MDM2 and cyclin G1.

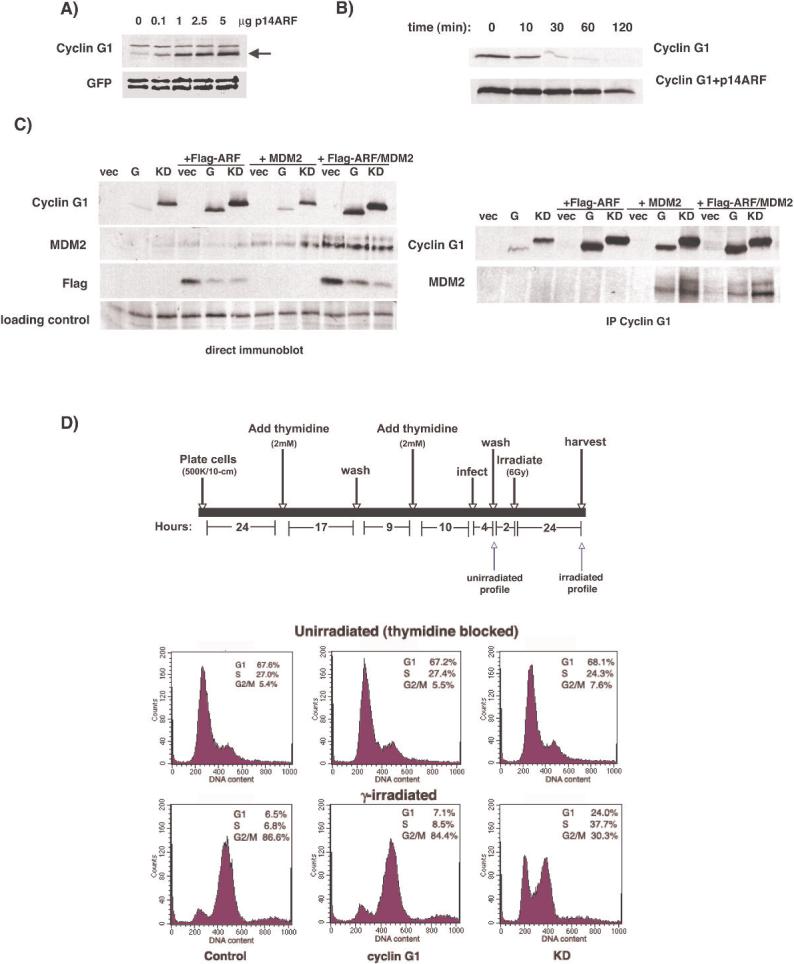

We next examined the effects of ARF overexpression on cyclin G1 abundance. ARF has been shown to interact with cyclin G1 (21), and as a negative regulator of MDM2's ability to act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, might alter cyclin G1 half-life. Indeed, the steady-state level of exogenous cyclin G1 protein increases in the presence of increasing amounts of transfected ARF in U2OS cells, an ARF-negative cell line (Fig. 6A). Pulse-chase experiments in transfected U2OS cells confirmed that coexpression of ARF and cyclin G1 increased the half-life of cyclin G1 to approximately 2 hours (Fig. 6B), further supporting a role for MDM2 in the regulation of cyclin G1 half-life. Interestingly, we found a reciprocal relationship between ARF and wild-type cyclin G1 upon cotransfection (Fig. 6C, left panel and Fig. S7). Wild-type cyclin G1 levels were increased by ARF expression but ARF protein levels were reduced by either cyclin G1 or KD. We do not yet understand how cyclin G1 might regulate ARF, however both cyclin G1 and KD retain the ability to interact with MDM2 (Fig. 6C, right panel) even in the presence of overexpressed ARF. Together, these data imply that polyubiquitination of cyclin G1 stimulated by MDM2 is necessary, but not sufficient, for proteasome-mediated cyclin G1 degradation and that the integrity of the cyclin box is required for cyclin G1's rapid turnover, perhaps as a consequence of specific subnuclear localization.

Figure 6.

Stabilization of cyclin G1 by ARF, interaction with MDM2 and effect on DNA damage response. A, Untagged cyclin G1 was cotransfected into U2OS cells with GFP and increasing amounts of p14ARF. Lysates were immunoblotted for cyclin G1 and GFP as a control. B, U2OS cells were transfected with Flag-tagged cyclin G1 or Flag-cyclin G1 plus p14ARF and labeled with 35S-methionine. Cells were then fed excess cold methionine, lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibody to determine protein half-life. C, left panel: U2OS cells were transfected with HA-tagged cyclin G1 and Flag-tagged p19ARF, MDM2 or both Flag-ARF and MDM2. Lysates were blotted for cyclin G1, MDM2 or Flag. right panel: The lysates from A were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies and blotted for cyclin G1 and MDM2. No interaction between ARF and cyclin G1 was detected by co-IP. D. Top: schematic representation of protocol used to synchronize, infect and irradiate cells. Cells were stained with propidium iodide and the cell cycle profiles of GFP positive cells were determined by flow cytometry. Timepoints corresponding to profiles shown are indicated by arrows. Bottom: Effect of cyclin G1 and KD on the cell cycle profile of synchronized U2OS cells before and after γ-irradiation. No effect is seen with either wild-type cyclin G1 or KD prior to irradiation, but KD alters the cell cycle profile of irradiated cells. Quantitation was performed using ModFit.

In an effort to understand the potential role of cyclin G1 kinase activity in the p53-mediated response to DNA damage we analyzed cell cycle profiles of irradiated cells overexpressing cyclin G1 or KD. U2OS cells were synchronized by a double thymidine block and infected with adenovirus co-expressing GFP marker and cyclin G1 or KD. The cells were then exposed to γ-irradiation and harvested for flow cytometry 24 hours later (Fig. 6D, top panel). As shown in Figure 6D; control, cyclin G1 and KD infected cells demonstrated similar cell cycle profiles following synchronization with thymidine prior to irradiation. However, 24 hours after γ-irradiation, the majority of control and cyclin G1 infected cells were blocked in G2/M, whereas KD infected cells exhibited a decreased G2/M fraction, with a concomitant increase of cells in other phases. This suggests that cyclin G1 is required for the establishment and/or maintenance of the G2/M checkpoint in response to ionizing radiation, and that KD can interfere with this process. Thus, the integrity of the cyclin box of cyclin G1 appears to be important and may play a role in the ability of cyclin G1 to modulate the DNA damage response.

DISCUSSION

Although transcriptional activation of cyclin G1 by p53 is well established, a complete understanding of its function remains elusive. The current study confirms and extends several novel aspects of cyclin G1 regulation. First, in addition to its transcriptional regulation by p53, the stability of the cyclin G1 protein is also regulated (21). This stability is not p53-dependent. Second, a clear relationship exists between the potential CDK-activating functions of cyclin G1 and its stability since mutation of a conserved lysine in the putative cyclin box markedly increases the half-life of exogenous cyclin G1 as does cotransfection of CDKs and p27KIP1 or dominant-negative CDKs. Third, there is an association between the stability of exogenous cyclin G1 and its subcellular localization, both of which depend on the integrity of the cyclin box. Fourth, ARF appears to regulate both the stability and nucleolar localization of ectopically expressed cyclin G1 ((21), and Fig. S8). Fifth, cyclin G1 associates with and its ubiquitination is stimulated by MDM2. Proteasome inhibition results in the accumulation of both exogenous and endogenous cyclin G1 and the appearance of cyclin G1-ubiquitin conjugates. Finally, mutation of the cyclin box of cyclin G1 has an effect on the establishment and/or maintenance of the G2/M arrest following DNA damage of cells overexpressing cyclin G1.

An ability of cyclin G1 to activate a CDK partner may facilitate its proteolysis. The observation that the activity of a cyclin can regulate its own degradation is not novel. For example, it is known that the stability of cyclin E is increased when it is involved in an inactive complex, either with dnCDK2 or when the cyclin E/CDK2 complex is bound and inactivated by inhibitors such as p27KIP1 or p21CIP1 (37, 39, 45). Consistent with this, phosphorylation of Thr380 of cyclin E by CDK2 promotes its degradation by freeing cyclin E from its complex with CDK2. Cellular distribution is also a means of cyclin regulation as the subcellular relocalization of cyclin D1 to the cytoplasm is required for its ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis (46). Here too, CDK association plays a role in stability, but in contrast to cyclin E, association with either functional or nonfunctional CDK subunits stimulates cyclin D1 phosphorylation, translocation, ubiquitination and degradation.

Our data suggest that control of cyclin G1 stability has elements of both cyclin D1 and cyclin E dependence on CDK association. Ectopically expressed, wild-type cyclin G1 bound to dnCDK subunits is stable and excluded from the nucleolus. Similarly, the cyclin box mutant, KD, which may be unable to form active complexes with a CDK, binds MDM2 in the nucleoplasm and is ubiquitinated, but is excluded from the nucleolus and is stable. Thus, whereas kinase activitation by cyclin G1 does not appear to be required for its ubiquitination, it may be necessary for its subsequent delivery to the proteasome for degradation, a process that can be blocked by ARF. It has been shown for G1 cyclins in yeast that polyubiquitination in itself is not sufficient for degradation by the proteasome and the authors speculate that activity may be required for release of polyubiquitinated cyclin from the ubiquitin ligase complex (47). It may be that autophosphorylation of cyclin G1 is required to release it from a CDK partner prior to degradation. However, as we have confirmed no wild-type cyclin G1 kinase activity to date, we can currently only speculate on the possible correlation between a CDK-activating function and stability of cyclin G1.

The stabilization of cyclin G1 by ARF suggests a role for ARF in the regulation of a member of the p53 pathway other than MDM2 and p53 itself. Interesting parallels exist between p53 and cyclin G1. Both are short-lived nuclear proteins, with half-lives less than 30 minutes, both are degraded in an ubiquitin-mediated, proteasome-dependent manner, both bind MDM2 (48, 49) and are stabilized by ARF (12). However, the half-life of cyclin G1 is not increased by DNA damage in NIH-3T3 cells and in contrast to p53, cyclin G1 itself is relocalized to the nucleolus upon overexpression of ARF (21). Whether stabilized cyclin G1 has a role in the nucleolus remains a question for further study.

We did not see any significant effect of cyclin G1 or KD overexpression on unirradiated U2OS cells at 24−48 hours after infection. However, we did detect a defect in the G2/M checkpoint following γ-irradiation in KD expressing cells. It may be the case that cyclin G1 requires other p53-induced genes and/or the environment created by p53 in order for it to function. The defect seen with KD was almost identical to that seen in cyclin G1 knockout MEFs (26), supporting the notion that KD is acting in a dominant-negative fashion. It is not at all surprising that overexpression of cyclin G1 had no effect after DNA damage, as cyclin G1 levels should already be high under these conditions due to activation by p53. The role of cyclin G1 at the G2/M checkpoint requires further study.

The metabolism of cyclin G1 is clearly linked to MDM2 and ARF, suggesting an additional layer of feedback regulation in the p53 pathway (21). Cyclin G1 aids in the degradation of the protein that activates it (p53), and helps to activate the protein that ubiquitinates and degrades it (MDM2) (21, 23). The stringent control of cyclin G1 expression by two known tumor suppressors, both by transcriptional regulation and protein stabilization, suggests that restraining the activity of cyclin G1 is very important. The complex network of interrelationships between p53, MDM2, ARF and cyclin G1 suggested by data presented here predict that successful assays for the function of cyclin G1 as a putative CDK activator may require the integrity of all of these proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank A. Wahl, A. Levine, C. Maki, K. Munger, M. Roussel, S. van den Heuvel and L.-H. Tsai for generously providing reagents. This work was support by NIH grant CA096527 to PWH.

Supported by NIH grant CA096527 to PWH

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–10. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:909–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris SL, Levine AJ. The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene. 2005;24:2899–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corcoran CA, Huang Y, Sheikh MS. The p53 paddy wagon: COP1, Pirh2 and MDM2 are found resisting apoptosis and growth arrest. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:721–5. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.8.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.el-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, et al. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng C, Zhang P, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Leder P. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell. 1995;82:675–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwakuma T, Lozano G. MDM2, an introduction. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:993–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman DA, Wu L, Levine AJ. Functions of the MDM2 oncoprotein. Cellular & Molecular Life Sciences. 1999;55:96–107. doi: 10.1007/s000180050273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honda R, Yasuda H. Activity of MDM2, a ubiquitin ligase, toward p53 or itself is dependent on the RING finger domain of the ligase. Oncogene. 2000;19:1473–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li M, Brooks CL, Wu-Baer F, Chen D, Baer R, Gu W. Mono- versus polyubiquitination: differential control of p53 fate by Mdm2. Science. 2003;302:1972–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1091362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu ZK, Geyer RK, Maki CG. MDM2-dependent ubiquitination of nuclear and cytoplasmic P53. Oncogene. 2000;19:5892–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherr CJ. Divorcing ARF and p53: an unsettled case. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:663–73. doi: 10.1038/nrc1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okamoto K, Beach D. Cyclin G is a transcriptional target of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. EMBO Journal. 1994;13:4816–22. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zauberman A, Lupo A, Oren M. Identification of p53 target genes through immune selection of genomic DNA: the cyclin G gene contains two distinct p53 binding sites. Oncogene. 1995;10:2361–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter T, Pines J. Cyclins and cancer. II: Cyclin D and CDK inhibitors come of age. Cell. 1994;79:573–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90543-6. [see comments]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray AW. Recycling the cell cycle: cyclins revisited. Cell. 2004;116:221–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pastila R, Leszczynski D. Ultraviolet-A radiation induces changes in cyclin G gene expression in mouse melanoma B16-F1 cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2007;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang CM, Park KP, Song JE, et al. Possible biomarkers for ionizing radiation exposure in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Radiat Res. 2003;159:312–9. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0312:pbfire]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanaoka Y, Kimura SH, Okazaki I, Ikeda M, Nojima H. GAK: a cyclin G associated kinase contains a tensin/auxilin-like domain. FEBS Letters. 1997;402:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01484-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohtsuka T, Ryu H, Minamishima YA, Ryo A, Lee SW. Modulation of p53 and p73 levels by cyclin G: implication of a negative feedback regulation. Oncogene. 2003;22:1678–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao L, Samuels T, Winckler S, et al. Cyclin G1 has growth inhibitory activity linked to the ARF-Mdm2-p53 and pRb tumor suppressor pathways. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:195–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto K, Kamibayashi C, Serrano M, Prives C, Mumby MC, Beach D. p53-dependent association between cyclin G and the B' subunit of protein phosphatase 2A. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 1996;16:6593–602. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto K, Li H, Jensen MR, et al. Cyclin G recruits PP2A to dephosphorylate Mdm2. Mol Cell. 2002;9:761–71. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00504-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura SH, Nojima H. Cyclin G1 associates with MDM2 and regulates accumulation and degradation of p53 protein. Genes Cells. 2002;7:869–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennin DA, Don AS, Brake T, et al. Cyclin G2 associates with protein phosphatase 2A catalytic and regulatory B' subunits in active complexes and induces nuclear aberrations and a G1/S phase cell cycle arrest. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27449–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111693200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura SH, Ikawa M, Ito A, Okabe M, Nojima H. Cyclin G1 is involved in G2/M arrest in response to DNA damage and in growth control after damage recovery. Oncogene. 2001;20:3290–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen MR, Factor VM, Fantozzi A, Helin K, Huh CG, Thorgeirsson SS. Reduced hepatic tumor incidence in cyclin G1-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2003;37:862–70. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baek WK, Kim D, Jung N, et al. Increased expression of cyclin G1 in leiomyoma compared with normal myometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:634–9. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez R, Wu N, Klipfel AA, Beart RW., Jr A better cell cycle target for gene therapy of colorectal cancer: cyclin G. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:884–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-003-0034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reimer CL, Borras AM, Kurdistani SK, et al. Altered regulation of cyclin G in human breast cancer and its specific localization at replication foci in response to DNA damage in p53+/+ cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:11022–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu A, Nishida J, Ueoka Y, et al. CyclinG contributes to G2/M arrest of cells in response to DNA damage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:529–33. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skotzko M, Wu L, Anderson WF, Gordon EM, Hall FL. Retroviral vector-mediated gene transfer of antisense cyclin G1 (CYCG1) inhibits proliferation of human osteogenic sarcoma cells. Cancer Research. 1995;55:5493–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith ML, Kontny HU, Bortnick R, Fornace AJ. The p53-regulated cyclin G gene promotes cell growth: p53 downstream effectors cyclin G and Gadd45 exert different effects on cisplatin chemosensitivity. Experimental Cell Research. 1997;230:61–8. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinds PW, Dowdy SF, Eaton EN, Arnold A, Weinberg RA. Function of a human cyclin gene as an oncogene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:709–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeffrey PD, Russo AA, Polyak K, et al. Mechanism of CDK activation revealed by the structure of a cyclinA-CDK2 complex. Nature. 1995;376:313–20. doi: 10.1038/376313a0. [see comments]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamura K, Kanaoka Y, Jinno S, et al. Cyclin G: a new mammalian cyclin with homology to fission yeast Cig1. Oncogene. 1993;8:2113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clurman BE, Sheaff RJ, Thress K, Groudine M, Roberts JM. Turnover of cyclin E by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is regulated by cdk2 binding and cyclin phosphorylation. Genes & Development. 1996;10:1979–90. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diehl JA, Sherr CJ. A dominant-negative cyclin D1 mutant prevents nuclear import of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and its phosphorylation by CDK-activating kinase. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 1997;17:7362–74. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Won KA, Reed SI. Activation of cyclin E/CDK2 is coupled to site-specific autophosphorylation and ubiquitin-dependent degradation of cyclin E. EMBO Journal. 1996;15:4182–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okamoto K, Prives C. A role of cyclin G in the process of apoptosis. Oncogene. 1999;18:4606–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finlay CA, Hinds PW, Tan TH, Eliyahu D, Oren M, Levine AJ. Activating mutations for transformation by p53 produce a gene product that forms an hsc70-p53 complex with an altered half-life. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:531–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.2.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang S, Jensen JP, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH, Weissman AM. Mdm2 is a RING finger-dependent ubiquitin protein ligase for itself and p53. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:8945–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Letters. 1997;420:25–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kubbutat MH, Ludwig RL, Levine AJ, Vousden KH. Analysis of the degradation function of Mdm2. Cell Growth & Differentiation. 1999;10:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winston JT, Chu C, Harper JW. Culprits in the degradation of cyclin E apprehended. Genes & Development. 1999;13:2751–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.21.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diehl JA, Cheng M, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates cyclin D1 proteolysis and subcellular localization. Genes & Development. 1998;12:3499–511. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ceccarelli E, Mann C. A Cdc28 mutant uncouples G1 cyclin phosphorylation and ubiquitination from G1 cyclin proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41725–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hinds PW, Finlay CA, Quartin RS, et al. Mutant p53 DNA clones from human colon carcinomas cooperate with ras in transforming primary rat cells: a comparison of the “hot spot” mutant phenotypes. Cell Growth & Differentiation. 1990;1:571–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Momand J, Zambetti GP, Olson DC, George D, Levine AJ. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69:1237–45. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.