Abstract

One of the major complications of diabetes is the alteration of the blood-retinal barrier, leading to retinal edema and consequent vision loss. The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of the urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA)/uPA receptor (uPAR) system in the regulation of retinal vascular permeability. Biochemical, molecular, and histological techniques were used to examine the role of uPA and uPAR in the regulation of retinal vascular permeability in diabetic rats and cultured retinal endothelial cells. The increased retinal vascular permeability in diabetic rats was associated with a decrease in vascular endothelial (VE) -cadherin expression in retinal vessels. Treatment with the uPA/uPAR-inhibiting peptide (Å6) was shown to reduce diabetes-induced permeability and the loss of VE-cadherin. The increased permeability of cultured cells in response to advanced glycation end products (AGEs) was significantly inhibited with Å6. Treatment of endothelial cells with specific matrix metalloproteinases or AGEs resulted in loss of VE-cadherin from the cell surface, which could be inhibited by Å6. uPA/uPAR physically interacts with AGEs/receptor for advanced glycation end products on the cell surface and regulates its activity. uPA and its receptor uPAR play important roles in the alteration of the blood-retinal barrier through proteolytic degradation of VE-cadherin. The ability of Å6 to block retinal vascular permeability in diabetes suggests a potential therapeutic approach for the treatment of diabetic macular edema.—Navaratna, D., Menicucci, G., Maestas, J., Srinivasan, R., McGuire, P., Das, A. A peptide inhibitor of the urokinase/urokinase receptor system inhibits alteration of the blood-retinal barrier in diabetes.

Keywords: VE-cadherin, extracellular proteinases, vascular permeability

The breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB) with resulting retinal edema is a common vascular abnormality found in patients with diabetic retinopathy (1). The leakage of plasma constituents into retinal tissue contributes to significant vision loss in these patients and creates a molecular environment that favors additional complications including retinal neovascularization. Normal microvascular permeability is partially maintained by the presence of specific junctional proteins present between adjacent capillary endothelial cells. Changes in endothelial permeability are known to be associated with the spatial redistribution of the surface cell junction proteins cadherin and occludin, the stabilization of focal adhesions, and the expression and activity of specific extracellular proteinases (2).

The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) were originally identified as zinc-dependent extracellular proteinases that degrade various components of the extracellular matrix (ECM). The substrate profile of the MMPs has expanded rapidly over the past few years to include not just ECM molecules but also numerous cell surface proteins (3). It is now evident that the MMPs have emerged as regulators of endothelial barrier function in several tissues (4,5,6,7,8,9). Recently, increased proteinase activity has been shown to directly affect endothelial cell junctions by degrading both adherens and tight junction proteins responsible for barrier function (10,11,12,13,14). We and others have previously demonstrated increased expression of MMPs in the retinas of diabetic animals (12, 13, 15). The increase in proteolytic activity and subsequent turnover of junctional proteins may facilitate sustained changes in permeability, requiring increased expression of junctional proteins to restore normal barrier function.

Urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) is a serine proteinase constitutively expressed in endothelial cells and is involved in many physiological and pathological processes involving cell migration, invasion, and tissue remodeling (16,17,18). Urokinase is secreted as a 50-kDa single-chain peptide and is activated after binding to its receptor, uPAR (19, 20). uPAR is associated with the cell surface via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor and is able to bind both the pro- and active forms of uPA. Once activated, the primary function of urokinase is the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, a broad-spectrum enzyme capable of widespread ECM degradation and activation of several pro-MMPs (21). Ultimately this leads to highly localized areas of increased proteinase activity within the close vicinity of the cell.

In addition to proteolysis, other investigators have also demonstrated an important role for uPA and uPAR in the regulation of cell signaling. These signaling events regulate several cellular processes including reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and adhesion of cells to the ECM (22, 23). Despite our growing knowledge of the role of uPA and uPAR in regulating cell behavior, the proteolytic and nonproteolytic roles of the uPA/uPAR system in microvascular permeability remain poorly understood.

In a previous study, we have reported the proteolytic degradation of vascular endothelial (VE) -cadherin from the surface of cultured endothelial cells by MMP-9 (13). An inhibitor of MMPs was able to block diabetes-induced vascular permeability and prevented the loss of VE-cadherin in the retinal vasculature (13). In the present study we have used a peptide derived from the non-receptor-binding region of urokinase (Å6) to evaluate the role of the uPA/uPAR system in the regulation of diabetic retinal vascular permeability. Results from this study extend the model of proteinase-induced alteration of the blood-retinal barrier by demonstrating a role for uPA/uPAR in the regulation of MMP secretion and activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Fibronectin-coated dishes were obtained from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and glycoaldehyde-modified advanced glycation end product (AGE) -BSA was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antibody to VE-cadherin was obtained from Alexis Corporation (Lüufelingen, Switzerland), and purified MMP-2 and -9 were from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis MN, USA). MMP-2/9 inhibitor was obtained from Calbiochem. Å6, an inhibitor of the urokinase system, was kindly provided by Angstrom Pharmaceuticals (Solana Beach, CA, USA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise noted.

Animal model

Brown Norway rats were injected with a single i.p. injection of streptozotocin (60 mg/kg) in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 4.5. Control nondiabetic rats received injections of an equal volume of citrate buffer only. Animals with plasma glucose concentrations greater than 250 mg/dl 24–48 h after streptozotocin injection were considered diabetic and included in these studies. The animals were maintained without additional insulin for a period of 2 wk. Total glycated hemoglobin was measured in each animal at the end of the 2-wk period. All experiments were consistent with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were done in accordance with institutional animal care and use guidelines.

Cell culture

Bovine retinal microvascular endothelial cells were purchased from VEC Technologies (Rensselaer, NY, USA). Human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (ACBRI-181) were obtained from Cell Systems (Kirkland, WA, USA). Bovine retinal microvessel endothelial cells and human retinal microvessel endothelial cells were grown on fibronectin- or gelatin-coated dishes in MCDB-131 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 0.2 mg/ml EndoGro, and 0.09 mg/ml heparin. Passages 3–10 were used for all experiments.

Quantitative assessment of BRB permeability

Vascular permeability in the retina was measured after 2 wk of diabetes using an Evans blue quantitation technique (24). Briefly, each rat was anesthetized and received an i.v. of 45 mg/kg Evans blue dye. Two hours later, the animal was reanesthetized, a 0.3-ml blood sample was obtained, and the animal was perfused via the left ventricle with PBS followed by 1% paraformaldehyde. The retinas were collected in PBS, dried for 2 h, and weighed. The Evans blue dye was extracted from the dried retinas with formamide at 70°C for 18 h, and the solution was centrifuged through a 30,000 MW filter (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, USA). The absorbances of the retinal extract and a 1:1000 dilution of plasma were measured by spectrophotometry at 620 and 740 nm. The concentrations of dye in the extract and plasma were calculated from a standard curve of Evans blue dye. The BRB permeability was calculated as follows, and data were expressed as ml/mg · h/eye:

|

In some experiments, diabetic rats were treated with an i.p. injection of 15 mg/kg of the Å6 peptide immediately after the induction of diabetes and then every day for 14 days, and retinal vascular permeability was analyzed by the Evans blue technique.

Semiquantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The retinal vasculature was selectively isolated from other components of the retina using an osmotic shock procedure as described previously (13, 25). In brief, two retinas from each mouse were incubated in ice-cold sterile water for 1 h at 4°C followed by incubation with RQ DNase (40 μg/ml) for 5 min. The microvascular networks were transferred to ice-cold water and cleaned of debris by pipetting through a wide-bore Pasteur pipette. The purity of the vascular preparations obtained by this procedure was previously determined by analysis of the level of neuron-specific enolase and glial fibrillary acidic protein by Western blotting or reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR of vascular and total retinal lysates. Total mRNA was extracted from the microvascular networks using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and cDNA was synthesized using TaqMan RT reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The following TaqMan assays for real-time RT-PCR were obtained from Applied Biosystems: rat uPA, Rn00695755_m1; rat uPAR, Rn00569290_m1; and eukaryotic 18S RNA, Hs99999901_s1. Amplification and detection were performed using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast system. Data were derived using the comparative CT method for triplicate reactions (26).

Western blot analysis of VE-cadherin shedding

Endothelial cells were incubated in serum-free medium for 24 h with AGE-BSA (50 mg/ml) with or without Å6 (100 μM). Additional cultures were incubated for 2 h in serum-free medium with either purified MMP-2 (0.1 μg/ml), MMP-3 (0.18 ng/ml), or MMP-9 (0.1 μg/ml). The conditioned media from the various treatments were concentrated using Centricon filters (30-kDa cutoff), and total protein was quantitated using the MicroBCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of total protein were loaded onto a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes and probed with an antibody to the VE-cadherin ectodomain (Alexis Biochemicals; San Diego, CA, USA). The bands were visualized using a chemiluminescent detection kit (Pierce Biotechnology) and GNOME-GeneSnap advanced imaging software (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA).

Coimmunoprecipitation assay

Human retinal vascular endothelial cells were lysed in Tris buffered saline-3-[3-cholamidopropyl) diethylammonio]-1 propane sulfonate buffer with 1% BSA for 2 h in the presence of protease inhibitors. After removal of cell debris the cell extract was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with 5 μl/ml of anti-uPAR antibody (a kind gift of Dr. Robert Orlando, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA) and 20 μl of protein A-agarose. The protein A-agarose adsorbed molecules were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions. Proteins were transferred onto PVDF membrane and probed with an antibody to the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The bands were visualized using a chemiluminescent detection kit (Pierce) and a GNOME-GeneSnap advanced image acquisition software machine (Syngene).

Proteinase assays

The levels and degree of activation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were examined in cells by gelatin zymography. Cells were cultured for 48 h in serum-free medium and treated with AGE-BSA (50 mg/ml) in the presence or absence of Å6 (100 μM), anti-uPAR antibody (10 μl/ml), or phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (1 U/ml). After incubation, the conditioned medium was collected, and aliquots were removed for total protein determinations. Conditioned medium was subjected to electrophoresis in 10% polyacrylamide minigels into which gelatin (1 mg/ml) was cross-linked. Zones of clearing corresponding to the presence of proteinases in the samples were quantitated using the Alpha Innotech image analysis system.

In vitro permeability assays

Bovine retinal endothelial cells were seeded onto fibronectin-coated transwell inserts (0.4-μm pore size) and grown in complete medium for 5 days until confluence was reached. The cells were changed to serum-free medium and 5 ml of 40 mg/ml 40,000 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) -dextran was added to the top chamber. Different wells received AGE-BSA (2 μM) with or without Å6 (100 μM). Aliquots of medium (50 μl) were removed from the bottom chamber at 0, 24, and 48 h and analyzed by quantitative fluorimetry at 485 nm (excitation) and 538 nm (emission).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Bovine retinal endothelial cells were passed onto glass coverslips coated with fibronectin and allowed to reach confluence. Cells were stimulated for 48 h with AGE-BSA (50 mg/ml) with or without Å6 (100 μM). The cells were fixed in a 3:1 solution of ice-cold methanol/acetic acid and stained for VE-cadherin (Alexis Biochemicals). The cells were examined using a fluorescence microscope, and images were captured and pseudo-colored using the MetaMorph image analysis program.

Microvessels in the retinas of 2-wk diabetic and control animals were stained for VE-cadherin in retinal whole mounts. Briefly, retinas were isolated and fixed in 100% ethanol, delipidated in 100% ice-cold acetone, and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100. Samples were incubated with an antibody to VE-cadherin (Alexis Biochemicals) at 4°C and washed extensively. VE-cadherin was localized using a FITC-labeled secondary antibody and Z-stack images were obtained using a confocal microscope (LSM 510 META; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Gottingen, Germany) and analyzed qualitatively for differences in VE-cadherin staining. Analysis was limited to the midperipheral region of the retina and up to 12 separate areas per retina were photographed.

Statistical methods

For all quantitative experiments, statistical analyses of data were performed using either an unpaired t test or a one-way ANOVA using Prism4 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA)

RESULTS

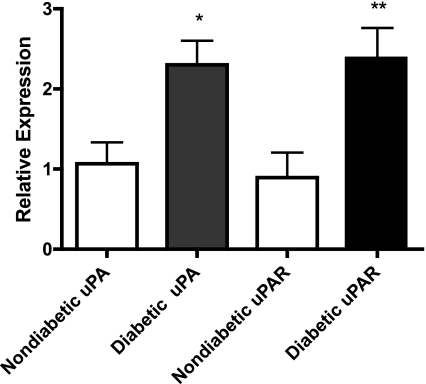

uPA and uPAR expression is upregulated in the retina of diabetic animals

We have previously shown that the expression of specific MMPs is up-regulated in the retinas of animals with diabetes coincident with an increase in retinal vascular permeability and that these proteinases can degrade the cell adhesion molecule VE-cadherin (12, 13). Potential interactions exist between the function of these MMPs and the serine proteinase uPA and its receptor uPAR. Here we have examined the expression of uPA and uPAR in isolated retinal vessels from animals with 2 wk of diabetes. Two weeks after the induction of diabetes, the blood glucose levels of the diabetic animals was >400 mg/dl compared with an average of 167 mg/dl for the control nondiabetic animals. Both uPA and uPAR mRNA levels were significantly increased in isolated retinal vessels from diabetic animals by more than 2-fold compared with levels in nondiabetic controls (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

uPA and uPAR mRNA levels are increased in the retinal vasculature after 2 wk of diabetes. Vascular networks were isolated from whole retinas of diabetic (n=4) and nondiabetic (n=6) animals as described in Materials and Methods. Total RNA was isolated, and semiquantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using the comparative CT method of quantitation. Vessels from diabetic animals demonstrate significantly more uPA and uPAR mRNA than vessels from nondiabetic controls. Data are means ± se; analysis by Student’s t test. *P = 0.0341; **P = 0.0453.

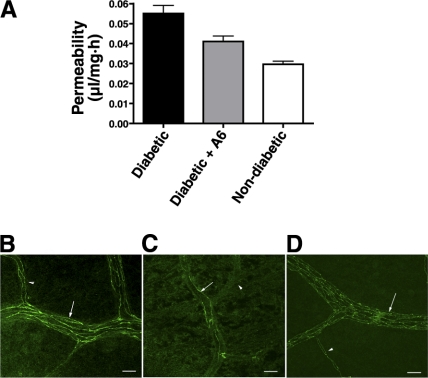

Å6 peptide blocks diabetes-induced retinal vascular permeability and the loss of VE-cadherin

To confirm a role for uPA/uPAR in barrier function, we next assessed the ability of the Å6 peptide to block the increases in retinal vascular permeability seen after 2 wk of diabetes. Å6 has been shown previously to effectively inhibit retinal neovascularization in an animal model of oxygen-induced retinopathy possibly by disrupting uPA and uPAR function (27). Animals treated with Å6 after the induction of diabetes demonstrated a significant decrease in the level of retinal vascular permeability compared with that in diabetic animals receiving a PBS injection only (Fig. 2A). The diabetic animals also demonstrated a loss of VE-cadherin associated with the small retinal vessels as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy. In the control nondiabetic animals, VE-cadherin was evenly distributed along the endothelial intercellular junctions with no obvious areas of discontinuity (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the vessels from the diabetic retinas demonstrated a substantial loss of cell surface-associated VE-cadherin as evidenced by a decrease in the number of fluorescent strands within the vessels. (Fig. 2C). Based on our previous studies we have concluded that this loss of VE-cadherin is due to both down-regulation of the VE-cadherin mRNA and proteolytic degradation of the cadherin ectodomain (13). When diabetic animals were treated daily with the Å6 peptide, the loss of VE-cadherin staining was prevented. In Å6-treated animals, the VE-cadherin was evenly distributed throughout the vessels wall (Fig. 2D) as seen by an increased number of fluorescent strands within the vessel profiles.

Figure 2.

Å6 treatment prevents microvascular permeability and loss of VE-cadherin in the diabetic retina. A) Retinal vascular permeability was assessed using the Evans blue dye technique. The permeability of the retinal vasculature in Å6-injected diabetic rats is comparable to that of noninjected nondiabetic controls. Values are means ± se; n = 6 animals/group; ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Diabetic vs. diabetic + Å6 or nondiabetic, P < 0.001; diabetic + Å6 vs. nondiabetic, P > 0.05. B–D) Retinal whole mounts from control nondiabetic (B), diabetic (C), and diabetic rats injected with Å6 (D), stained with anti-VE-cadherin antibody. In nondiabetic retinas, VE-cadherin expression is present at the interfaces between adjacent endothelial cells of arterioles (arrows) and capillaries (arrowheads), as evidenced by the large number of fluorescently labeled strands. The number of VE-cadherin strands is greatly reduced in the blood vessels of the diabetic retina. The VE-cadherin staining pattern in Å6-injected rats is comparable to that in nondiabetic controls. Images are reconstructions of a series of Z stacks of retinal blood vessel segments. Scale bars = 20 μM.

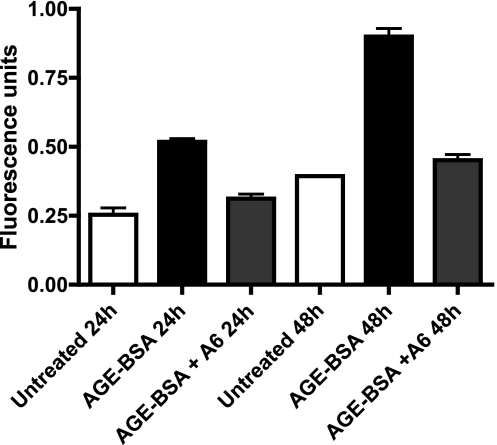

uPA and uPAR mediate AGE-induced changes in endothelial cell barrier function

Hyperglycemia in the diabetic animal creates an environment that leads to changes in microvascular permeability associated with a loss of VE-cadherin. A characteristic of this altered environment seen in the diabetic retina is the formation and activity of AGEs. The role of uPA and uPAR in mediating the effects of AGEs in alteration of endothelial barrier function was assessed using isolated bovine retinal microvascular endothelial cells. Cultured endothelial cells incubated with 50 μg/ml AGE-BSA demonstrated a significant increase in monolayer permeability after 24 or 48 h of stimulation compared with that in untreated cells (Fig. 3). This effect was found to be uPA/uPAR-dependent, as simultaneous treatment of cells with AGE-BSA and the inhibitor Å6 resulted in a reduction of permeability to a level not significantly different than that of control untreated cells. (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

AGE stimulation increases endothelial cell monolayer permeability that is decreased by Å6. The permeability of confluent bovine retinal microvascular endothelial cells was determined using FITC-dextran, as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were incubated with or without 50 mg/ml AGE-BSA for 24 or 48 h in the presence or absence of Å6 (100 μM). Values are means ± se for each group; ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. P < 0.05 was considered significant. AGE-BSA 24 h vs. untreated 24 h or AGE-BSA + Å6 24 h, P < 0.001; untreated 24 h vs. AGE-BSA + Å6 24 h, P < 0.01; AGE-BSA 48 h vs. untreated 48 h or AGE-BSA + Å6 48 h, P < 0.001; untreated 48 h vs. AGE-BSA + Å6 48 h, P < 0.01.

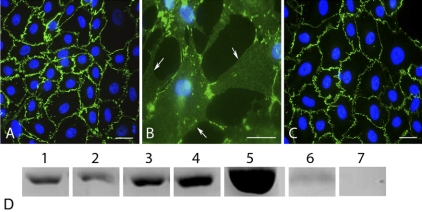

Previously, we have demonstrated that the proteolytic degradation of VE-cadherin by MMPs might be responsible for the increased retinal vascular permeability seen in diabetes (13). Here we examined whether a reduction in AGE-induced permeability by Å6 prevented the proteolytic degradation of VE-cadherin by MMPs. Untreated cultures of confluent bovine retinal endothelial cells displayed a continuous pattern of VE-cadherin staining associated with the lateral cell borders (Fig. 4A). Treatment with AGE-BSA caused a disruption of cell-cell contact and loss of VE-cadherin from the cell surface (Fig. 4B). This loss of VE-cadherin leads to cell-cell separation and the formation of gaps between adjacent cells. Cells treated simultaneously with AGE-BSA and Å6 demonstrated cellular morphology and a VE-cadherin staining pattern similar to that of untreated cells (Fig. 4C). The cell monolayer remained intact, and gaps did not develop between the cells. To confirm that the VE-cadherin molecule was being spared in the presence of Å6, the conditioned medium was probed for the VE-cadherin ectodomain. Cells treated with either purified MMPs or AGE-BSA were found to release an ∼75-kDa proteolytic fragment of the VE-cadherin ectodomain into the conditioned medium. The addition of Å6 (100 μM) simultaneously with AGE-BSA resulted in a significant decrease in the level of VE-cadherin ectodomain shedding into the conditioned medium (Fig. 4D). Treatment with Å6 also prevented VE-cadherin shedding in untreated cells, suggesting that Å6 blocks proteinase activity responsible for the low level of normal VE-cadherin turnover.

Figure 4.

MMP-dependent degradation of VE-cadherin is abolished by Å6. A–C) Bovine retinal microvascular endothelial cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 48 h under various treatment conditions, fixed, and stained for VE-cadherin. Treatment conditions: serum-free medium alone (A), medium plus AGE-BSA (50 μg/ml) (B), and medium plus AGE-BSA (50 μg/ml) with Å6 (100 μM) (C). Loss of VE-cadherin from the cell surface is seen in cells treated with AGE-BSA (arrows in B), creating large retraction gaps between cells. Å6 prevents the loss of VE-cadherin from lateral cell borders in response to AGE-BSA (C) and preserves the integrity of the cell monolayer. D) A proteolytic degradation fragment of VE-cadherin (∼75-kDa ectodomain) was detected by Western blotting of the conditioned medium from untreated cells (lane 1) or cells treated for 2 h with either MMP-2 (0.1 μg/ml) (lane 2), MMP-3 (0.18 ng/ml) (lane 3), or MMP-9 (0.1 μg/ml) (lane 4). The amount of VE-cadherin ectodomain released into the medium was also determined from cells treated for 24 h with AGE-BSA (50 mg/ml) (lane 5), AGE-BSA in the presence of Å6 (100 μM) (lane 6), or cells treated with Å6 only (lane 7). Equal amounts of total protein were loaded in each lane. Representative blot of three replicate experiments.

uPAR interacts with RAGE and mediates the up-regulation of proteinases in AGE-treated cells

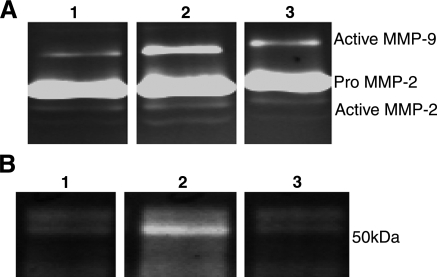

The previous results suggest that the mechanisms of blood-retinal barrier breakdown in diabetes may involve uPA and uPAR-dependent alterations of VE-cadherin. The uPA/uPAR-dependent activation of plasminogen can activate a number of pro-MMPs, which may degrade the adhesion molecules present between adjacent endothelial cells. To better understand this possible mechanism, the conditioned media of bovine retinal endothelial cells treated with AGE-BSA in the presence or absence of Å6 were analyzed by zymography. AGE stimulation of these cells resulted in an increase in both the pro and active forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9 that was blocked by the presence of the Å6 peptide (Fig. 5A). AGE-BSA also increased the expression of uPA in these cells and treatment with Å6 also blocked this response (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Å6 prevents AGE-induced activation and secretion of uPA, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in cultured retinal endothelial cells. A) Representative gelatin zymogram of the conditioned medium collected from untreated cells (lane 1), cells treated with 50 μg/ml AGE-BSA (lane 2), and cells treated with AGE-BSA and Å6 (100 μM) (lane 3). After 48 h of AGE treatment, an increase in production of both the pro and activated forms of the enzymes was seen. B) Representative casein/plasminogen zymogram of the conditioned medium collected from untreated cells (lane 1), cells treated with 50 μg/ml AGE-BSA (lane 2), and cells treated with AGE-BSA and Å6 (100 μM) (lane 3). An increase in uPA secretion was seen in these cells after incubation with AGE-BSA for 48 h, which was inhibited by the presence of Å6.

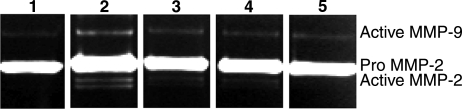

To further confirm a role for uPAR in mediating MMP expression in response to the presence of AGE, cells were incubated with a neutralizing antibody against uPAR or an enzyme that cleaves uPAR and other GPI-anchored proteins from cell surfaces (phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C). Conditioned medium of cells treated with AGE-BSA in the presence of an anti-uPAR antibody or phospholipase C showed reduced secretion of MMP-2 and MMP-9, similar to what was observed with Å6 treatment, further suggesting that uPAR contributed to the AGE-induced induction of these proteinases (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

uPAR is required for AGE-mediated up-regulation of MMPs in bovine retinal microvascular endothelial cells. Representative gelatin zymograms of conditioned medium from untreated cells (lane 1), cells treated with 50 μg/ml AGE-BSA (lane 2), cells treated with AGE-BSA plus anti-uPAR antibody (lane 3), cells treated with AGE-BSA plus phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (lane 4), and cells treated with AGE-BSA plus Å6 peptide (lane 5). A significant reduction in MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion is seen with all treatments.

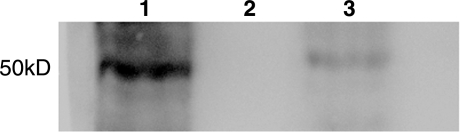

Stimulation of cells by AGE occurs through binding of AGE to RAGE on the cell surface. RAGE is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of proteins and has been shown to mediate numerous signaling pathways within AGE-stimulated cells (28,29,30,31,32). The above results suggest a possible interaction between RAGE and uPAR on the cell surface. To begin to examine the association of uPAR with RAGE, human retinal endothelial cell lysates were incubated with AGE for 24 h and immunoprecipitated with an anti-uPAR antibody and probed for RAGE by Western blotting. A 50-kDa band corresponding to intact RAGE was seen in the anti-uPAR precipitates, suggesting a physical interaction between the two molecules (Fig. 7, lane 1). No band was seen when the anti-uPAR antibody was omitted from the precipitation. In some cases cells were incubated with AGE and 100 mM Å6 peptide. In the presence of Å6, the amount of RAGE associated with uPAR was dramatically reduced (Fig. 7, lane 3).

Figure 7.

uPAR and RAGE interact on the cell surface of endothelial cells. Endothelial cells were incubated with AGE for 24 h in the presence or absence of the Å6 peptide (100 μM) and lysed. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-uPAR antibody and probed for RAGE by Western blotting. A 50-kDa band corresponding to intact RAGE is seen in precipitates of cell lysates (lane 1). Omitting the anti-uPAR antibody during the precipitation results in no RAGE in the precipitate (lane 2). Precipitates of cells incubated with AGE and the Å6 peptide show a dramatic reduction in the amount of RAGE associated with uPAR (lane 3).

DISCUSSION

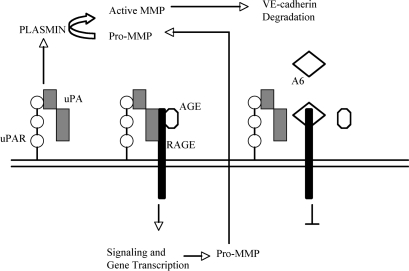

In this study we have investigated the mechanism whereby Å6 inhibits diabetic microvascular permeability in vivo and prevents the loss of VE-cadherin from the surface of retinal endothelial cells. Stimulation of cells with AGE-BSA induced the secretion of uPA, MMP-2, and MMP-9 and also increased the activation of MMP-2. Cells treated with AGE-BSA in the presence of Å6 showed reduced expression and activation of these proteinases, suggesting that uPA/uPAR are important in modulating the activity of the AGE receptor RAGE. A physical interaction between uPA/uPAR and RAGE would support this hypothesis, and this was confirmed by immunoprecipitation of uPAR, which revealed the presence of RAGE. Based on these results, we propose a model in which uPA bound to uPAR facilitates the interaction of uPAR with RAGE to induce the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Fig. 8). The details of this model are currently under investigation.

Figure 8.

Working model of uPA/uPAR regulation of RAGE signaling. Data from the present study suggest that the AGE up-regulation of MMPs, leading to VE-cadherin degradation, may be regulated in part through an interaction with uPA and uPAR. This interaction may be disrupted by the presence of the Å6 peptide, resulting in an inhibition of RAGE signaling.

As early as 2 wk after diabetes induction, uPA and uPAR mRNA levels are significantly increased in the diabetic retina coincident with an increase in retinal vascular permeability. The regulation of uPA and uPAR expression in response to diabetes has not been extensively investigated. A previous study demonstrated increased uPA activity in cultures of mesangial cells exposed to high glucose, which the authors suggest may lead to the glomerular extracellular matrix changes seen in diabetes (33). In addition, El-Remessy et al. (34) reported the up-regulation of uPAR in the retina of the diabetic rat mediated by reactive nitrogen species. Additional factors in the diabetic animal responsible for up-regulation of uPA and uPAR may be the presence of AGEs as suggested by our studies of isolated retinal endothelial cells treated with AGEs.

An important mechanism involved in the diabetes-induced alteration of the BRB appears to be the modification of interendothelial junctions of the retinal microvasculature. We and others have reported on the modification of the endothelial tight junction protein occludin in the retina during diabetes (12, 35, 36). Recently, we have also reported on the important role played by the endothelial adhesion molecule VE-cadherin in maintenance of the BRB. Disruption of VE-cadherin alone results in significant increases in retinal vascular permeability (13). In the diabetic animal, this protein appears to be susceptible to cleavage by specific MMPs, which may open the BRB, and its expression is down-regulated, thus preventing junctional repair. Together these events may lead to persistent vascular leakage in the diabetic retina and the development of significant retinal edema.

The role of the uPA/uPAR system in alteration of endothelial junctions during diabetes was investigated using agents that affect the function of these proteins. Treatment of diabetic animals with the Å6 peptide reduced the level of retinal vascular permeability and prevented the loss of VE-cadherin from interendothelial cell junctions. In addition, increased permeability of isolated endothelial cell monolayers and the release of VE-cadherin fragments in response to AGE treatment could also be prevented by Å6. The Å6 peptide used in this study is an 8-amino acid peptide derived from the connecting peptide region of uPA (residues 136–143), which probably affects the interaction of uPA/uPAR with other cell surface proteins. Numerous studies over the past few years have described alternative nonproteolytic roles for uPA and uPAR, which are important in the regulation of cell behavior (22, 37). In some cases, these functions are dependent on the physical engagement of uPA/uPAR complexes with other cell surface molecules, resulting in specific cell signaling events. Recently the connecting peptide domain of uPA has been shown to be important in mediating the interaction of uPAR with the avb5 integrin and the stimulation of cell migration in a uPAR-independent manner (38).

The molecular mechanisms that mediate changes in the structure and function of the BRB during diabetes are not completely known. The data presented here demonstrate that the serine proteinase uPA, and its receptor uPAR, play important roles in this process and that interfering with the function of these proteins may be a potential novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of early diabetic retinopathy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Angstrom Pharmaceuticals for the kind gift of the Å6 peptide used for these studies. This work was supported by Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International 1-2006-36 and National Institutes of Health grant RO1 EY12604.

References

- Klein R, Klein B E, Moss S E, Cruickshanks K J. The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy: XVII. The 14-year incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy and associated risk factors in type 1 diabetes. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1801–1815. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)91020-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J S, Elrod J W. Extracellular matrix, junctional integrity and matrix metalloproteinase interactions in endothelial permeability regulation. J Anat. 2002;200:561–574. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauwe B, Van den Steen P E, Opdenakker G. The biochemical, biological, and pathological kaleidoscope of cell surface substrates processed by matrix metalloproteinases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42:113–185. doi: 10.1080/10409230701340019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J R, Gabler W L. Effects of doxycycline in two rat models of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 1994;37:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J R, Gabler W L. Doxycycline suppression of ischemia- reperfusion-induced hepatic injury. Inflammation. 1994;18:193–201. doi: 10.1007/BF01534560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen C C, Wiggers H, Andersen H R. Increased amounts of collagenase and gelatinase in porcine myocardium following ischemia and reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1431–1442. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahi M, Wang X, Mori T, Sumii T, Jung J C, Moskowitz M A, Fini M E, Lo E H. Effects of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out on the proteolysis of blood-brain barrier and white matter components after cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7724–7732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07724.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etoh T, Joffs C, Deschamps A M, Davis J, Dowdy K, Hendrick J, Baicu S, Mukherjee R, Manhaini M, Spinale F G. Myocardial and interstitial matrix metallo-proteinase activity after acute myocardial infarction in pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H987–H994. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer W D, Wang O L, Haq A, Miller F N. Bradykinin and α-thrombin increase human umbilical vein endothelial macromolecular permeability by different mechanisms. Inflammation. 2000;24:175–193. doi: 10.1023/a:1007037711339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herren B, Levkau B, Raines E W, Ross R. Cleavage of β-catenin and plakoglobin and shedding of VE-cadherin during endothelial apoptosis: evidence for a role for caspases and metalloproteinases. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1589–1601. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachtel M, Frei K, Ehler E, Fontana A, Winterhalter K, Gloor S M. Occludin proteolysis and increased permeability in endothelial cells through tyrosine phosphatase inhibition. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:4347–4356. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.23.4347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel S J, Menicucci G, McGuire P G, Das A. Matrix metalloproteinases in early diabetic retinopathy and their role in alteration of the blood-retinal barrier. Lab Invest. 2005;85:597–607. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaratna D, McGuire P G, Menicucci G, Das A. Proteolytic degradation of VE-cadherin alters the blood-retinal barrier in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:1–9. doi: 10.2337/db06-1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carden D, Xiao F, Moak C, Willis B H, Robinson-Jackson S, Alexander S. Neutrophil elastase promotes lung microvascular injury and proteolysis of endothelial cadherins. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H385–H392. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzmann J, Limb G, Khaw P, Gregor Z, Webster L, Chignell A, Charteris D. Matrix metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors in fibrovascular membranes of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1091–1096. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.10.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi F, Vassalli J D, Dano K. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator: proenzyme, receptor and inhibitors. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:801–804. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassalli J D, Sappino A P, Belin D. The plasminogen activator/plasmin system. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1067–1072. doi: 10.1172/JCI115405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano D, Franco P, Vocca I, Gambi N, Pisa V, Mancini A, Caputi M, Carriero M V, Iaccarino I, Stoppelli M P. The urokinase plasminogen activator and its receptor: role in cell growth and apoptosis. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:205–211. doi: 10.1160/TH04-09-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estreicher A, Wohlwend A, Belin D, Schleuning W D, Vasalli J D. Characterization of cellular binding site for the urokinase-type plasminogen activator. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1180–1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldan A L, Cubellis M V, Masucci M T, Behrendt N, Lund L R, Dano K, Appella E, Blasi F. Cloning and expression of the receptor for human urokinase plasminogen activator, a central molecule in cell surface plasmin dependent proteolysis. EMBO J. 1990;9:467–474. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowski G S, Ramsby M L. Binding of latent matrix metalloproteinase 9 to fibrin: activation via a plasmin-dependent pathway. Inflammation. 1998;22:287–305. doi: 10.1023/a:1022300216202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder B R, Mihaly J, Prager G W. uPAR-uPA-PAI-l interactions and signaling: a vascular biologist’s view. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo M, Thomas K S, Somlyo A V, Somlyo A P, Steven S L. Cooperativity between the Ras-ERK and Rho-Rho kinase pathways in urokinase-type plasminogen activator-stimulated cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12479–12485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Qaum T, Adamis A P. Sensitive blood-retinal barrier breakdown quantitation using Evans blue. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:789–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagher Z, Park Y S, Asnaghi V, Hoehn T, Gerhardinger C, Lorenzi M. Studies of rat and human retinas predict a role for the polyol pathway in human diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2001;53:2404–2411. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K J, Schmittgen T D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire P G, Jones T R, Talarico N, Warren E, Das The urokinase/urokinase receptor system in retinal neovascularization: inhibition by Å6 suggests a new therapeutic target. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2736–2742. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander H M, Tauras J M, Ogiste J S, Hori O, Moss R A, Schmidt A M. Activation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products triggers a p21ras-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway regulated by oxidant stress. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17810–17814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen H J, Fages C, Rauvala H. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)-mediated neurite outgrowth and activation of NF-κB require the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor but different downstream signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19919–19924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi A, Blood D C, Del Toro G, Canet A, Lee D C, Qu W, Tanji N, Lu Y, Lalla E, Fu C, Hofmann M A, Kislinger T, Ingram M, Lu A, Tanaka H, Hori O, Ogawa S, Stern D M, Schmidt A M. Blockade of RAGE-amphotericin signalling suppresses tumour growth and metastases. Nature. 2000;405:354–360. doi: 10.1038/35012626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S D, Schmidt A M, Anderson G M, Zhang J, Brett J, Zou Pinsky Y S, Stern D. Enhanced cellular oxidant stress by the interaction of advanced glycation end-products with their receptors binding-proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9889–9897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J F, Qu X Q, Schmidt A M. Sp1-binding elements in the promoter of RAGE are essential for amphoterin-mediated gene expression in cultured neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30870–30878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.30870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada H, Tsukamoto M, Ishii H, Isogai S. A high concentration of glucose alters the production of tPA, uPA and PAI-1 antigens from human mesangial cells. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;24:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Remessy A B, Behzadian M A, Abou-Mohamed G, Franklin T, Caldwell R W, Caldwell R B. Experimental diabetes causes breakdown of the blood-retina barrier by a mechanism involving tyrosine nitration and increases in expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1995–2004. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64332-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber A J, Antonetti D A, Gardner T W. Altered expression of retinal occludin and glial fibrillary acidic protein in experimental diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3561–3568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harhaj N S, Felinski E A, Wolpert E B, Sundstrom J M, Gardner T W, Antonetti D A. VEGF activation of protein kinase C stimulates occludin phosphorylation and contributes to endothelial permeability. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5106–5115. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano D, Franco P, Vocca I, Gambi N, Pisa V, Mancini A, Caputi M, Carriero M V, Iaccarino I, Stopelli M P. The urokinase plasminogen activator and its receptor: role in cell growth and apoptosis. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:205–211. doi: 10.1160/TH04-09-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco P, Vocca I, Carriero M V, Alfano D, Cito L, Longanesi-Cattani I, Grieco P, Ossowski L, Stoppelli M P. Activation of urokinase receptor by a novel interaction between the connecting peptide region of urokinase and avb5 integrin. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3424–3434. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]