Abstract

OBJECTIVE—Longer survival of patients with cystic fibrosis has increased the occurrence of cystic fibrosis–related diabetes (CFRD). In this study we documented the incidence of CFRD and evaluated the association between mutations responsible for cystic fibrosis and incident CFRD, while identifying potential risk factors.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS—This was a population-based longitudinal study of 50 cystic fibrosis speciality clinics in the U.K. Subjects included 8,029 individuals aged 0–64 years enrolled in the U.K. Cystic Fibrosis Registry during 1996–2005. Of these, 5,196 with data and without diabetes were included in analyses of incidence, and 3,275 with complete data were included in analyses of risk factors. Diabetes was defined by physician diagnosis, oral glucose tolerance testing, or treatment with hypoglycemic drugs.

RESULTS—A total of 526 individuals developed CFRD over 15,010 person-years. The annual incidence was 3.5%. The incidence was higher in female patients and in patients with mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene in classes I and II. In a multivariate model of 377 cases of 3,275 patients, CFTR class (relative risk 1.70 [95% CI 1.16–2.49], class I or II versus others), increasing age, female sex, worse pulmonary function, liver dysfunction, pancreatic insufficiency, and corticosteroid use were independently associated with incident diabetes.

CONCLUSIONS—The incidence of CFRD is high in Britain. CFTR class I and II mutations increase the risk of diabetes independent of other risk factors including pancreatic exocrine dysfunction.

Considerable improvement in survival of patients with cystic fibrosis has led to the emergence of complications, one being cystic fibrosis–related diabetes (CFRD). Cystic fibrosis, an autosomal recessive disease caused by the presence on each gene of at least one of >1,500 mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), is characterized by chronic pulmonary infections, pancreatic insufficiency, biliary cirrhosis, low BMI, and, increasingly, CFRD. The prevalence of diabetes among European children and adults with cystic fibrosis now approximates 12%, rising to 30% in adults screened for diabetes (1—3).

Unlike those with type 1 diabetes, patients with CFRD rarely develop ketoacidosis, but like those with type 2 diabetes, they have elements of both decreased insulin secretion and sensitivity. Compared with other types of diabetes, the risk factors for CFRD are less well characterized; it is not entirely clear which factors differentiate individuals with cystic fibrosis who do, or do not, develop diabetes. Whereas genetic factors increase the prevalence (4,5) and probably the incidence of CFRD, we do not know whether they do so independent of other identified risk factors.

Most observational studies of CFRD were cross-sectional (3–7) and few prospective studies exist (2,8). Risk factors identified include, among others, female sex, increasing age, pancreatic insufficiency, poor pulmonary function, organ transplantation, elevated plasma fibrinogen, and CFTR genotype. Cross-sectional designs cannot exclude the possibility that diabetes itself modifies some of these factors. The design would also obscure the true association between any risk factors associated with shortened survival and CFRD (9). Likewise, no large longitudinal study has evaluated genetic factors associated with death, and, potentially, incident CFRD (7).

To support research and care in cystic fibrosis, a number of national registries have been established, including one in the U.K. in 1995, which is supported and coordinated by the Cystic Fibrosis Trust. Using data from the U.K. Cystic Fibrosis (UKCF) Registry, in this study we estimated incidence and identified risk factors for CFRD, with specific consideration for CFTR mutations, from a cohort of >5,000 children and adults with cystic fibrosis.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We identified 8,029 individuals aged 0–65 years entered in the registry from 1996 to 2005. Data were routinely collected after patient consent in a standardized fashion from 50 British cystic fibrosis specialist centers. Of 8,029 patients, 6,678 had complete baseline data defined as registration followed within the same calendar year by a visit consisting of an annual review plus a clinic visit. Of these 6,678 patients, 761 (11.4%) with diabetes were excluded. Of the 5,917 individuals without diabetes, 721 lacked further follow-up, leaving 5,196 with at least one annual follow-up visit, and 3,275 patients (aged 2.0–55.3 years) with complete data for all covariates. Patients with complete data (compared with those without) did not differ by sex but were older (median 14.1 vs. 5.2 years, P < 0.0001), due mainly to the difficulty of acquiring pulmonary function testing in babies and young children.

End point and potential risk factors

Diabetes was defined as a physician diagnosis of diabetes, plasma glucose values consistent with diabetes from oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT), or treatment with insulin or oral hypoglycemic drugs. Risk factors examined included age, sex, ethnicity, age of diagnosis of cystic fibrosis, respiratory infections, BMI, and pancreatic, hepatic, or pulmonary dysfunction. They also included supplemental feeding, prior organ transplantation, corticosteroid use, and method of detection (whether cystic fibrosis was detected via screening and CFTR genotype). Ethnicity was determined by the ethnicity of the parents. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. BMI z scores were calculated using a U.K. reference population (10). Pancreatic dysfunction was defined as use of pancreatic enzyme supplementation, and hepatic dysfunction was defined as portal hypertension, abnormal liver function tests, or use of the bile acids (ursodeoxycholic acid or taurine). Pancreatic enzyme supplementation was expressed as total daily dose of the lipase component and as daily dose per kilogram of body weight. Supplemental feeding included oral supplements and feeding via gastrostomy or nasogastric or parenteral routes. An individual was considered infected with bacteria or fungi if these were cultured from sputum at baseline or if a physician had diagnosed chronic infection from at least two isolates in the year before baseline. Organisms included Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Burkholderia cepacia, Haemophilus influenzae, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, and Aspergillus fumigatus. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) was diagnosed clinically. Pulmonary function was measured using forced expiratory volume at 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity expressed as percentage predicted (11).

Genotypes associated with cystic fibrosis were coded into five established classes reflecting CFTR function of defective production, processing, regulation, conductance, and quantity of CFTR protein (12) as follows: I: G542X, R553X, W1282X, R1162X, 621–1G→T, 1717–1G→A, 1078ΔT, and 3659ΔC; II: ΔF508, ΔI507, N1303K, and S549N; III: G551Dand R560T; IV: R117H, R334W, G85E, and R347P; V: 3849+5G→A, and A455E; and unknown: 711+IG→T, 2184DA, and 1898+IG→A. Patients with two alleles within the same class or only one allele typed were assigned that class. Heterozygotes for ΔF508 were assigned the class of the non-ΔF508 allele (13).

Statistics

Incidence rates for CFRD were calculated as the number of new cases divided by follow-up time among the 5,196 patients with baseline and follow-up data and stratified by 10-year age-groups and sex. In this retrospective cohort, follow-up time lasted from registration to the first detection of diabetes or censoring and is expressed in person-years.

Among the 3,275 individuals with complete data, we tested differences between patients who did and did not develop diabetes with χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests for normally or nonnormally distributed continuous variables. Proportional hazards modeling identified potential risk factors. For categorical variables, we evaluated proportional hazards assumptions using Kaplan-Meyer survival curves. We chose variables for multivariate modeling if they were associated with CFRD in univariate analyses at P ≤ 0.05. Age at baseline, BMI, BMI z score, and FEV1 were coded as continuous. Binary variables included sex, ethnicity (at least one nonwhite parent versus two white parents), hepatic dysfunction, supplemental feeding, respiratory infections, ABPA, oral pancreatic enzyme supplementation, and corticosteroid use (oral and/or inhaled) within the year before registration. Age of diagnosis of cystic fibrosis and dose of pancreatic enzyme supplementation were coded as binary variables around the medians. We coded CFTR genotype by class as described and as a binary variable (class I–II vs. III–V). One-way interactions between genotype or sex and other variables were tested. We calculated hazard ratios (expressed as relative risks [RRs]) with 95% CIs. We performed database manipulations using Caché (InterSystems, 2007) and statistical analyses using R (R Development Core Team, 2007).

RESULTS

The median age of the cohort was 12.0 years (interquartile range 6.0–19.8); 54% were male and 96% were white. The characteristics of the study population and of those who did or did not develop CFRD are shown (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients at baseline stratified by development of diabetes

| Parameter | All patients | Did not develop diabetes | Incident diabetes | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 3,275 | 2,898 | 377 | |

| Age (years) | 14.1 (9.2–21.1) | 13.5 (8.9–20.5) | 18.0 (12.4–25.4) | <0.0001 |

| Sex (female) | 1,491 (45.5) | 1,288 (44.4) | 203 (53.8) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (white) | 3,166 (96.7) | 2,797 (96.5) | 369 (97.9) | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.6 (16.4–21.3) | 18.5 (16.3–21.3) | 19.2 (17.3–21.4) | <0.001 |

| BMI z score | −0.15 (−0.86 to 0.56) | −0.10 (−0.81 to 0.59) | −0.49 (−1.23 to 0.22) | <0.0001 |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 72.9 (53.0–91.3) | 75.3 (55.3–92.7) | 57.8 (36.9–74.5) | <0.0001 |

| Forced vital capacity (% predicted) | 82.6 (68.0–94.1) | 83.6 (69.6–95.3) | 73.3 (57.1–86.9) | <0.0001 |

| Any use of pancreatic enzyme | 2,941 (89.8) | 2,579 (89.0) | 362 (96.0) | <0.01 |

| Lipase dose (units/day) | 250,000 (150,000–400,000) | 250,000 (150,000–400,000) | 300,000 (184,000–500,000) | <0.0001 |

| Lipase dose (units · kg body weight−1 · day−1) | 6,829 (3,464–10,200) | 6,828 (3,448–10,150) | 6,865 (3,602–10,560) | NS |

| Supplemental feeding | 1,439 (43.9) | 1,236 (42.7) | 203 (53.8) | <0.0001 |

| Oral corticosteroids | 313 (9.6) | 263 (9.1) | 50 (13.3) | 0.012 |

| Any corticosteroids use | 1,761 (53.8) | 1,526 (52.7) | 235 (62.3) | <0.001 |

| Former organ transplantation | 44 (1.3) | 37 (1.3) | 7 (1.9) | NS |

| Abnormal liver function tests | 406 (12.4) | 342 (11.8) | 64 (16.9) | <0.01 |

| Use of ursodeoxycholic acid or taurine | 534 (16.3) | 455 (15.7) | 79 (21.0) | 0.012 |

| Any hepatic dysfunction | 719 (28.1) | 610 (21.0) | 109 (28.9) | <0.001 |

| P. aeruginosa | 1,925 (58.8) | 1,651 (57.0) | 274 (72.7) | <0.0001 |

| B. cepacia | 151 (4.6) | 129 (4.5) | 22 (5.8) | NS |

| S. aureus | 1,379 (42.1) | 1,223 (42.2) | 156 (41.4) | NS |

| H. influenzae | 668 (20.4) | 605 (20.9) | 63 (16.7) | NS |

| A. fumigatus | 341 (10.2) | 301 (10.2) | 40 (10.6) | NS |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus | 46 (1.4) | 40 (1.4) | 6 (1.6) | NS |

| ABPA | 197 (6.0) | 178 (6.1) | 19 (5.0) | NS |

| CFTR mutation class | <0.01 | |||

| I | 266 (8.1) | 227 (7.8) | 39 (10.3) | |

| II | 2,608 (79.6) | 2,299 (79.3) | 309 (82.0) | |

| III | 256 (78.2) | 231 (8.0) | 25 (6.6) | |

| IV | 125 (3.8) | 121(4.2) | 4 (1.1) | |

| V | 20 (0.6) | 20 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| CFTR mutation class I or II | 2,874 (87.7) | 2,526 (87.2) | 348 (92.3) | <0.01 |

| Age at diagnosis of cystic fibrosis (years) | 0.4 (0.08–2.5) | 0.4 (0.08–2.5) | 0.5 (0.08–2.0) | NS |

| Cystic fibrosis detected by screening | 377 (11.5) | 349 (12.0) | 28 (7.4) | 0.011 |

Data are absolute values (medians) or n (%) for continuous variables with interquartile range and percentages for categorical variables. P values represent difference between groups using Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

Incidence

Of 5,196 patients, 526 developed diabetes during 15,010 person-years of follow-up (median 2.67 years, range 0.08–8.33 years). In 40% (211 patients), diabetes was diagnosed on the basis of insulin use, in 22% (117 patients) from OGTT results, in 4% (20 patients) on the basis of use of oral hypoglycemic drugs, and in 1% (5 patients) by a physician. The remainder met multiple criteria. The incidence of diabetes was 3.5% per year. During follow-up, 202 patients died without having the diagnosis of diabetes.

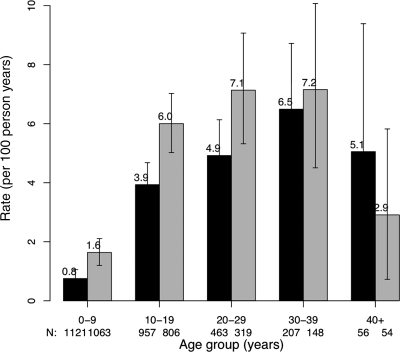

The incidence rose with age, was higher in female patients up to age 40, and declined after age 40 for both men and women. Annual incidence rose from 1 to 2% in the first decade to ∼6 to 7% in the fourth decade (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Incidence of CFRD per 100 person-years by age and sex. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence limits; ▪, male patients; □, female patients.

Risk factors

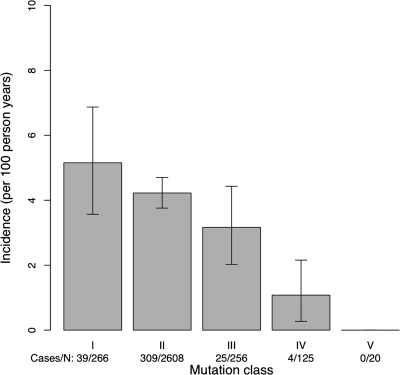

Patients with class I mutations had the highest incidence of CFRD, and those with class V mutations had the lowest incidence (Fig. 2). The incidence was significantly higher in individuals with class I or II relative to III to V mutations (P < 0.01). In univariate analyses, patients with incident CFRD were less likely to have been screened for cystic fibrosis and more likely to have infections, to have liver or pulmonary function abnormalities, and to have used corticosteroids or pancreatic enzyme replacement. The median FEV1 in patients who developed CFRD was 57.8% compared with 75.3% in those who did not (P < 0.0001). Adjusted for age and/or sex, FEV1 remained strongly inversely associated with incident CFRD. BMI was higher and BMI z scores were lower in those who developed diabetes than in those who did not (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Incidence of CFDR per 100 person-years by class of CFTR mutation. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence limits.

In a multivariate model, increasing age, female sex, decreasing FEV1, liver dysfunction, pancreatic enzyme replacement, corticosteroids use, and CFTR genetic class were independently associated with incident diabetes. CFTR class I and II compared with III to IV was associated with a RR of 1.70. Female patients were ∼60% more likely to develop diabetes than male patients, and each year of age or percent decrease in predicted FEV1 was associated with a 2–3% increase in risk (Table 2). Diagnosis of cystic fibrosis by screening, pulmonary infections, supplemental feeding, and BMI or BMI z score was not associated with CFRD in multivariate modeling. There were no significant interactions. After exclusion of 334 individuals not taking pancreatic enzymes, a multivariate model (362 cases among 2,931 patients) showed no association between the dosage of pancreatic enzyme replacement and CFRD.

Table 2.

Multivariate risk factor model and models composed of one independent variable for CFRD

| Risk factor | Reference | RR (95% CI)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate model | Univariate models | ||

| Age | Each year older | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) |

| Female sex | Male | 1.62 (1.32–1.99) | 1.37 (1.15–1.63) |

| FEV1 | Each % worse | 1.018 (1.013–1.023) | 1.022 (1.018–1.026) |

| Liver dysfunction | Versus absent | 1.41 (1.12–1.77) | 1.66 (1.36–2.03) |

| Any pancreatic enzyme use | Versus none | 2.97 (1.73–5.09) | 1.34 (1.1–1.63) |

| Any corticosteroid use | Versus none | 1.24 (1.002–1.53) | 1.65 (1.39–1.97) |

| CFTR class | I/II vs. III/IV/V | 1.70 (1.16–2.49) | 4.58 (1.81–13.0) |

n = 3,275 with 377 cases of incident diabetes.

CONCLUSIONS

This large, longitudinal, registry-based study documents a high incidence of CFRD among individuals with cystic fibrosis in Britain and demonstrates that CFTR mutation class independently increases risk. The study also confirms the fact that female patients are at higher risk for CFRD, which is not accounted for by a higher prevalence of risk factors in female patients. The study also confirms the independent associations of poor hepatic and pulmonary function and of use of pancreatic enzymes or corticosteroids with CFRD.

Few studies of CFRD incidence exist. The annual incidence of 3.5% we report is similar to the 3.8% reported from a Danish study of fewer than 200 patients (2). Based on extremely small numbers (12 and 6 incident cases of CFRD) and derived from cumulative incidence values, Italian (8) and Greek (14) investigators show a CFRD annual incidence of ∼4.0%. The high incidence of CFRD in the first decade in this study suggests that screening for diabetes in this age-group, although not currently recommended in the U.K., may be justified. Whether individuals with screen-detected diabetes fare better has not been determined.

CFTR protein regulates the function of chloride channels on the apical membrane of epithelial cells and helps regulate transepithelial transport of other ions and water. The grouping of mutations into functional categories is as follows: class I, no synthesis of CFTR; class II, degradation of CFTR in the endoplasmic reticulum; class III, transport of CFTR to the cell membrane, but no appropriate response; class IV, diminished action of CFTR in the cell membrane; and class V, normal but inadequate amounts of CFTR (12). Many studies document associations between functional class and complications of cystic fibrosis, including pancreatic dysfunction (13,15). This study shows an association between class and CFRD adjusted for pancreatic exocrine function as measured by pancreatic enzyme replacement. Investigators have previously searched for genes in CFRD, concentrating either on those associated with type 2 diabetes and inflammation or with cystic fibrosis. ΔF508 homozygosity was associated with CFRD in some, but not all, studies (3,16–19). A prospective study comprising few patients with incident diabetes (n = 12) (8) showed that patients homozygous for ΔF508 were more likely to develop diabetes. A large U.S. registry-based cross-sectional study reported an association of ΔF508 homozygosity and CFRD but presented only univariate results (4). A European registry study documented a greater prevalence of diabetes in adults among class II (282 of 1,276, 22.1%) mutations than in class IV mutations (1 of 65, 1.5%); however, no statistical testing was performed, and no incidence rate was calculated (5). The present study included 377 patients with CFRD, controlled for confounding factors, and, being longitudinal, accounted in part for competing risks (13). It could not, however, determine whether the risk factors caused diabetes.

Genotype may predispose to diabetes via pancreatic dysfunction or may play a more direct role. CFRD results more from decreased β-cell function than from decreased insulin sensitivity (19). This finding supports a function for CFTR in pancreatic islets where, in rats, investigators have identified CFTR mRNA (20). In mice made diabetic by streptozotocin, those who were CFTR-null (−/−) had higher blood glucose levels than other mice; the investigators concluded that islet dysfunction is inherent to the CFTR−/− state (21). CFTR has also been identified in the human hypothalamus, (22), where it may play a role in glucose regulation.

Whether pancreatic exocrine dysfunction mirrors pancreatic endocrine dysfunction is not clear. Investigators have found pancreatic exocrine dysfunction in both type 2 and type 1 diabetes. In cystic fibrosis, clinicians adjust doses of pancreatic enzyme to enable patients to eat a diet containing fat and diminish gastrointestinal symptoms. However, studies in cystic fibrosis have shown both under- and overtreatment with pancreatic enzymes relative to native pancreatic function (23). The strong association between pancreatic enzyme use and incident diabetes in this study suggests that enzyme use is likely to be a good marker of pancreatic function but may itself increase risk.

The association between female sex and CFRD is well described (4) and differs from that for type 1 or 2 diabetes. Earlier puberty with glucose intolerance has been proposed as an explanation (24) and may in part account for our findings because incidence in female patients rose between age 5 and 10 (not shown). Yet, the female predominance persists beyond puberty. The absence of a female predominance at age >30 suggests that women susceptible to diabetes will have developed it or may have died.

An association between poor pulmonary function and CFRD has been reported from cross-sectional studies (4–6), and other studies have demonstrated accelerated decline in pulmonary function before diagnosis of CFRD (2,25). In cystic fibrosis, it is possible that pre-diabetic (or prediagnostic) states worsen pulmonary function. In the present study, poor pulmonary function preceded diabetes and was independent of age, sex, genotype, medical interventions, and other cystic fibrosis–related complications. Individuals with diabetes (but without cystic fibrosis) have lung parenchymal histological changes including thickened basement membrane, fibrosis, and septal obliteration (26), suggesting a direct deleterious effect of hyperglycemia.

Other results are notable. Although cystic fibrosis is characterized by a low BMI, this did not itself increase the risk of diabetes. Corticosteroid use was independently associated with diabetes, but ABPA and organ transplantation, both indications for corticosteroids, were not, even in univariate analyses.

This study's strength was the use of longitudinal, national, and systematically collected data. With respect to possible biases related to incidence rates, the true incidence of CFRD in Britain may be higher than we report for three reasons. First, the calculation of time-to-diabetes overestimated true values because patients developed diabetes before their clinic visits. Second, not all individuals were screened for diabetes. The U.K. Cystic Fibrosis Trust recommends annual OGTTs during periods of clinical stability (17), and >85% (20 of 23) of adult centers screen for diabetes. For pediatric centers, screening is recommended at age >12. Last, patients excluded from analysis of incidence were older (∼1 year) and had worse pulmonary function (FEV1 ∼2% lower) and, therefore, were at higher risk for CFRD. Although incidence rates derived from registries may be less reliable than those from cohort studies, frequent follow-up of patients with cystic fibrosis in the U.K. (because of disease severity and free care) diminishes this possibility. Despite a longitudinal design, the RR we report for genotype may underestimate the true value if patients at high risk for diabetes died before registration or were less likely to undergo genotyping. For each of the variables (genotype, corticosteroid use, pancreatic enzyme replacement, poor pulmonary function, and poor hepatic function), ascertainment bias is possible. If sicker patients had more frequent clinical visits, then their physicians may have been more likely to diagnose diabetes, and this would mean that the RRs we report overestimate true values.

In summary, this study documents the high incidence of diabetes in cystic fibrosis and the fact that CFTR mutation class influences the risk of diabetes independent of other risk factors. It suggests that screening for diabetes may be merited across the age spectrum. By establishing age-specific incidence rates, this study provides useful information to health care providers, disease modelers, and clinical trialists. Finally, by identifying risk factors, this study may help us better understand the pathogenesis of CFRD.

Acknowledgments

The U.K. Cystic Fibrosis Trust provided access to the Registry. Elaine Gunn, Papworth Hospital, assisted with the Registry.

Published ahead of print at http://care.diabetesjournals.org on 5 June 2008.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1.Moran A, Doherty L, Wang X, Thomas W: Abnormal glucose metabolism in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 133:10–17, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanng S, Hansen A, Thorsteinsson B, Nerup J, Koch C: Glucose tolerance in patients with cystic fibrosis: five year prospective study. BMJ 311:655–659, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler AI, Gunn E, Haworth C, Bilton D: Characteristics of adults with and without cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Diabet Med 24:1143–1148, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall B, Butler S, Stoddard M, Moran A, Liou T, Morgan W: Epidemiology of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. J Pediatr 146:681–687, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koch C, Rainisio M, Madessani U, Harms HK, Hodson ME, Mastella G, McKenzie SG, Navarro J, Strandvik B: Presence of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes mellitus is tightly linked to poor lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis: data from the European Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic Fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 32:343–350, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sims EJ, Green M, Mehta A: Decreased lung function in female but not male subjects with established cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:1581–1587, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koch C, Cuppens H, Rainisio M, Madessani U, Harms H, Hodson M, Mastella G, Navarro J, Strandvik B, McKenzie S: European Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic Fibrosis (ERCF): comparison of major disease manifestations between patients with different classes of mutations. Pediatr Pulmonol 31:1–12, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cucinotta D, De Luca F, Scoglio R, Lombardo F, Sferlazzas C, Di Benedetto A, Magazzu G, Raimondo G, Arrigo T: Factors affecting diabetes mellitus onset in cystic fibrosis: evidence from a 10-year follow-up study. Acta Paediatr 88:389–393, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenfeld M, Davis R, FitzSimmons S, Pepe M, Ramsey B: Gender gap in cystic fibrosis mortality. Am J Epidemiol 145:794–803, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan H, Cole T: User's Guide to lmsGrowth [article online], 2007. London, Medical Research Council UK. Available from http://www.healthforallchildren.co.uk/pro.epl?DO=USERPAGE&PAGE=Imsdownload. Accessed 30 April 2008

- 11.Hankinson J, Odencrantz J, Fedan K: Spirometric reference values from a sample of the U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159:179–187, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowntree RK, Harris A: The phenotypic consequences of CFTR mutations. Ann Intern Med 67:471–485, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKone EF, Emerson SS, Edwards KL, Aitken ML: Effect of genotype on phenotype and mortality in cystic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 361:1671–1676, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nousia-Arvanitakis S, Galli-Tsinopoulou A, Karamouzis I: Insulin improves clinical status of patients with cystic-fibrosis-related diabetes mellitus. Acta Paediatr 90:515–519, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed N, Corey M, Forstner G, Zielenski J, Tsui LC, Ellis L, Tullis E, Durie P: Molecular consequences of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) gene mutations in the exocrine pancreas. Gut 52:1159–1164, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenecker J, Eichler I, Kuhn L, Harms H, von der Hardt H: Genetic determination of diabetes mellitus in patients with cystic fibrosis: a multicenter study screening fecal elastase 1 concentrations in 1,021 diabetic patients. J Pediatr 127:441–443, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamdi I, Payne SJ, Barton DE, McMahon R, Green M, Shneerson JM, Hales CN: Genotype analysis in cystic fibrosis in relation to the occurrence of diabetes mellitus. Clin Genet 43:186–189, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dominguez-Garcia A, Quinteiro-Gonzalez S, Pena-Quintana L, Ramos-Macias L, Quintana-Martel M, Saavedra-Santana P: Carbohydrate metabolism changes in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 20:621–632, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preumont V, Hermans MP, Lebecque P, Buysschaert M: Glucose homeostasis and genotype-phenotype interplay in cystic fibrosis patients with CFTR gene ΔF508 mutation. Diabetes Care 30:1187–1192, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boom A, Lybaert P, Pollet JF, Jacobs P, Jijakli H, Golstein PE, Sener A, Malaisse WJ, Beauwens R: Expression and localization of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in the rat endocrine pancreas. Endocrine 32:197–205, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stalvey MS, Muller C, Schatz DA, Wasserfall CH, Campbell-Thompson ML, Theriaque DW, Flotte TR, Atkinson MA: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator deficiency exacerbates islet cell dysfunction after β-cell injury. Diabetes 55:1939–1945, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulberg AE, Weyler RF, Altschuler SM, Hyde TM: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression in human hypothalamus. Neuroreport 9:141–144, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Littlewood JM, Wolfe SP, Conway SP: Diagnosis and treatment of intestinal malabsorption in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 41:35–49, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenecker J, Hofler R, Steinkamp G, Eichler I, Smaczny C, Ballmann M, Posselt HG, Bargon J, von der Hardt H: Diabetes mellitus in patients with cystic fibrosis: the impact of diabetes mellitus on pulmonary function and clinical outcome. Eur J Med Res 6:345–350, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milla CE, Billings J, Moran A: Diabetes is associated with dramatically decreased survival in female but not male subjects with cystic fibrosis. Diabetes Care 28:2141–2144, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsia CC, Raskin P: The diabetic lung: relevance of alveolar microangiopathy for the use of inhaled insulin. Am J Med 118:205–211, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]