Abstract

Using novel interferometric quantitative phase microscopy methods, we demonstrate that the surface integral of the optical phase associated with live cells is invariant to cell water content. Thus, we provide an entirely noninvasive method to measure the nonaqueous content or “dry mass” of living cells. Given the extremely high stability of the interferometric microscope and the femtogram sensitivity of the method to changes in cellular dry mass, this new technique is not only ideal for quantifying cell growth but also reveals spatially resolved cellular and subcellular dynamics of living cells over many decades in a temporal scale. Specifically, we present quantitative histograms of individual cell mass characterizing the hypertrophic effect of high glucose in a mesangial cell model. In addition, we show that in an epithelial cell model observed for long periods of time, the mean squared displacement data reveal specific information about cellular and subcellular dynamics at various characteristic length and time scales. Overall, this study shows that interferometeric quantitative phase microscopy represents a noninvasive optical assay for monitoring cell growth, characterizing cellular motility, and investigating the subcellular motions of living cells.

Keywords: phase microscopy, interferometric microscopy, cell growth

phase-contrast (PC) and differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy have been used extensively to study live cells without the need for exogenous contrast agents (32). The tremendous success of these methods is due to the fact that the optical phase shift through a given sample contains information about the refractive index (n) variations that directly result from structural features within the sample. Refractive index n can therefore be regarded as a powerful endogenous contrast agent for cellular structure (6). However, as the relationship between the irradiance and phase of the image field is generally nonlinear (30, 39), both PC and DIC are qualitative in nature and limited to morphological observations without specific structural data.

Quantitative phase microscopy has received substantial interest in recent years, as quantifying optical phase shifts associated with cells provides structural and dynamical information at the nanometer scale without the need for any cell preparation or the use of exogenous contrast or labels. Existing methods for biological quantitative phase measurements can be divided into single-point and full-field techniques. Several point measurement techniques have been used for investigating the local structure and dynamics of live cells (1, 7, 10, 14, 29, 36, 37). In contrast, full-field phase measurement techniques provide simultaneous information from a large region of the sample, which offers the additional benefit of studying both the temporal and spatial behavior of the sample (2, 5, 9, 13, 18–20, 40, 41).

Over the past several years, our laboratory has developed new full-field phase imaging techniques that are suitable for spatially resolved investigation of live cells. Fourier phase microscopy (FPM) combines PC microscopy and phase-shifting interferometry to retrieve quantitative phase images with high-transverse resolution and subnanometer pathlength stability over many hours (23). Because of its high stability due to the common path interferometric geometry, FPM is well suited for studies of cellular dynamics over extended periods of time from minutes to hours. Hilbert phase microscopy (HPM), in contrast, is a single-shot full-field technique that provides spatially resolved quantitative phase information about dynamic systems at the millisecond timescale (12, 24). Diffraction phase microscopy (DPM) combines the advantages of the common path geometry associated with FPM and the single-shot capability of HPM, thus allowing fast and stable quantitative phase imaging (21, 25). These microscopy methods have been established as powerful techniques for quantifying red blood cell (RBC) shapes and dynamics (24, 25). Measuring the spatial and temporal behavior of RBC membrane fluctuations has additionally provided new insights into RBC membrane biophysical properties (26–28).

In this article, we show that FPM and HPM can be applied successfully to study both the static and dynamic properties of nucleated cells that are structurally more complex than RBCs. We demonstrate experimentally that the quantitative phase image of a live cell relates to its “dry mass,” defined as the nonaqueous content of the cell. We additionally provide a theoretical model that describes the results. Using this technique, we obtained insights into complex dynamic phenomena such as cell growth and motility, without exogenous agents, in a completely noninvasive manner.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

FPM and HPM.

FPM combines the principles of PC microscopy and phase-shifting interferometry, and its principle of operation has been described in detail previously (23). Briefly, the FPM setup employs a common path interferometric geometry that is inherently characterized by long-term phase stability, which is a significant technical advantage over existing interferometric phase microscopy techniques (9, 40). To quantify the phase shift associated with individual cells over extended periods of time, the phase imaging was automated by synchronizing the phase shifting provided by a spatial light modulator with the image acquisition. We have previously shown that the FPM instrument is capable of retrieving nanoscale topographic information associated with standard samples, such as phase gratings and polystyrene microspheres (23). Despite the extreme long-term stability (hours to days), the acquisition speed of FPM is limited by the refresh rate of the spatial light modulator, which is typically in the order of several Hertz. For the experiments presented here, the FPM instrument was operated at 4 frames/min.

HPM extends the concept of complex analytic signals to the spatial domain and measures quantitative phase images from only one spatial interferogram recording (12, 24). Due to its single-shot nature, the HPM acquisition time is limited only by the recording device and thus can be used to accurately quantify nanometer-level pathlength shifts at the millisecond timescale or less, where many relevant biological phenomena develop. For the relatively slow cell volume change experiments presented here, however, the HPM instrument was triggered manually at ∼4 frames/min.

Cell culture.

For cell volume and dynamic experiments, HeLa cells (a cervical epithelial cell line) were cultured in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from GIBCO-BRL Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air and passaged every 3–4 days. Experimental measurements were taken when cells were ∼90% confluent in Lab-Tek II chamber slides (Nalge NUNC, Rochester, NY) unless otherwise specified.

For cell growth experiments, murine renal mesangial cells (cell line MES 13)were grown in DMEM with 10% FCS at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air until they reached ∼35% confluence. Cells were then synchronized by an incubation in 0.1% FCS medium for 24 h. The quiescent cultures thus obtained were exposed to either low (5.5 mM) or high (30 mM) d-glucose in DMEM supplemented with 0.1% FCS for an additional 48 h. Mannitol was added to low-glucose cultures to adjust the osmotic difference due to different glucose concentrations. Cells were then trypsinized and transferred to Lab-Tek II chamber slides at a constant cell density. To allow for cell adhesion to the culture substrate, phase microscopy measurements were done after an additional 6 h of incubation in the chamber slides.

Cell osmotic changes.

Cell volume changes were induced in HeLa cells by rapid changes in osmotic pressure of the culture medium. Lab-Tek II chamber slides were modified to allow continuous flow input from a syringe pump (PHD 2000, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Freshly passaged cells were incubated in the modified chamber for 4 h to allow cell attachment to the coverglass substrate. Hypertonic conditions were achieved by perfusing a 25% (wt/wt) solution of NaCl in water (refractive index n = 1.378, osmolarity = 8,600 mosM) at a rate of 0.05 ml/min into a constant culture volume of 2.5 ml. After 2.5–3 min of continuous microscopic imaging, the hypertonic perfusion was reversed, and the tonicity of the surrounding solution was returned to baseline by injecting a 0.1-ml bolus of water into the culture chamber followed by perfusion with standard culture medium. Cell imaging continued for an addition 2–3 min to monitor the cell volume return to baseline. During a typical experiment, the osmotic pressure of the culture chamber changed from a baseline of ∼285 mosM for the physiological culture medium to ∼475 mosM at the peak of hypertonic perfusion.

Optical phase shifts associated with cell volume changes and cell dry mass.

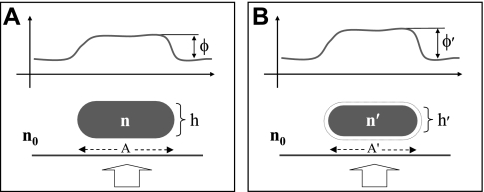

The equations describing average optical phase shifts associated with cell volume changes were derived as follows. Consider a live cell illuminated by a collimated beam of light that produces a certain spatial distribution of optical phase shift φ (Fig. 1A). Under hypertonic conditions, the cell expels water such that its volume (V) decreases and its average n increases (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

A: optical phase shift φ is produced by a cell of refractive index n and thickness h surrounded by a medium of refractive index n0. B: the same cell shrinking in a hypertonic solution assumes a new refractive index n′ and thickness h′, resulting in a new optical phase shift φ′. Thick arrows indicate the direction of the incident light beam. Cell projected areas A and A′ are indicated by dashed arrows on the substrate.

Now let us consider the problem of finding the overall n of the cell, which is the result of mixing a certain quantity of water (initial volume V0 and initial refractive index n0) with nonaqueous cellular material (V′ and n′). Applying the Maxwell Garnett theory for n of a two-substance mixture (11), we find the following:

|

(1) |

where

|

(2a) |

and f is the nonaqueous volume fraction,

|

(2b) |

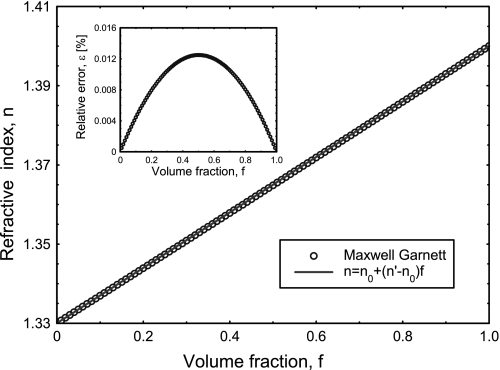

For a typical cell, n varies between 1.38 and 1.41, which is only a small deviation from the refractive index of water (n0 = 1.33). With this observation in mind, Fig. 2 shows the dependence of n on f, as predicted by Eq. 1 and assuming that n′ = 1.4. As shown in Fig. 2, because of the small n difference (n′ − n0), the n versus f dependence can be approximated very well by a linear function, n = n0 + f(n′ − n0). (The inset in Fig. 2 shows that the error of this approximation is below 1% for the entire range of f.) Thus, the equations can be rearranged to give n′ as follows:

|

(3) |

where V0 now represents the volume of water expelled by the cell during hypertonic cell shrinkage and V is the initial volume of the cell. Therefore, assuming isotropic volume change, the cell thickness before and after volume change (h and h′, respectively) can be related to cell volume as follows:

|

(4) |

or

|

(5) |

Furthermore, the average optical phase shifts before and after cell volume change (φ and φ′, respectively) are defined as follows:

|

(6) |

and

|

(7) |

where k0 is the wave vector of the light in vacuum. By combining Eqs. 3, 4 and 7, we find the following:

|

(8) |

or

|

(9) |

Equation 9 predicts φ′ in the hypertonic condition and shows that despite a reduction in cell size with water depletion, there is an increase in φ due to the overall increase in cell n.

Fig. 2.

Refractive index n of mixtures of water (n0 = 1.33) with nonaqueous material (n′ = 1.4) as a function of volume fraction f of the nonaqueous material as predicted by the Maxwell Garnett theory (○) and approximated by a linear function (solid line). Inset: relative error of the linear approximation. As the excellent fit shows, when n0 − n′ is small, the n versus f dependence can be adequately modeled as a straight line.

Next, by evaluating the surface integral (M′) of φ′ as ∫Aφ′(x,y)dxdy (where A is area) and substituting from Eqs. 3–9, we find the following:

|

(10) |

where S is the integration surface. For small changes in cell volume (V0 ≪ V), [(3V − V0)/(V − V0) ≈ 3]. Therefore,

|

(11) |

where M is the surface integral of the optical phase shift through the cell before volume change. Equation 11 indicates that for small volume changes of practical physiological interest, the surface integral of the optical phase shift, or the cell dry mass, is independent of cell volume. In other words, optically measured cell dry mass at any given point in time is essentially a constant, as physiologically expected. Furthermore, by rearranging Eq. 9, relative changes in cell volume can be directly related to experimental data as follows:

|

(12) |

Dynamic analysis of cell dry mass.

Quantitative phase images of HeLa cells as a function of time were recorded for an observation period of 2 h and imaged at the frequency of 4 frames/min. The data set was numerically processed to provide the instanteneous phase displacement at position r with respect to the temporal average, Δφ(r,t) = φ(r,t) − 〈φ(r,t)t〉, where the angular brackets denote time averaging. The displacement map at each moment in time was Fourier transformed spatially to provide Δφ(q,t), which describes the temporal phase fluctuation corresponding to each spatial wave vector (q). The spatiotemporal mean squared displacement (MSD) over time lag τ was then calculated using the following equation:

|

(13) |

where the factor λ/2π was used to transform the phase (in radians) into optical pathlength (in μm).

RESULTS

Quantitative phase imaging of live cells.

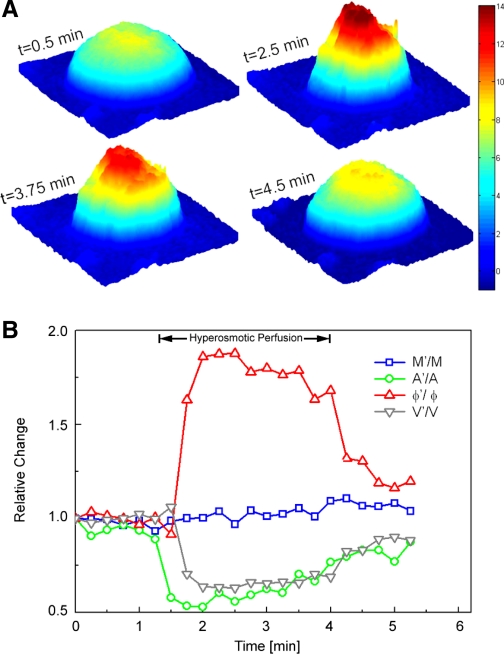

Quantitative phase images of live HeLa cells in normal culture medium were recorded by HPM. After a period of baseline observation, the cell chamber was perfused with a hypertonic solution, resulting in cell shrinkage as a result of osmotic water efflux. After 2.5–3 min of hypertonic perfusion, cells were returned to the isotonic condition and monitored until their volume returned to baseline. An example of a HeLa cell changing its volume in response to this dynamic osmolarity change is shown in Fig. 3A. Figure 3B shows the osmolarity-induced dynamic changes of the same cell in terms of its projected area (A′), φ′, M′, and V′.

Fig. 3.

A: representative snapshots of quantitative phase images of an isolated live HeLa cell at various time points (t) during volume regulation (the color bar indicates the phase in radians). B: for the same cell shown in A, the temporal variations of A′, φ′, calculated cell dry mass (M′), and volume (V′) are shown. Data were normalized to the initial values of A, φ, M, and V, respectively, to emphasize the relative magnitudes of change. As detailed in the text, cell dry mass stayed essentially constant, whereas projected area, optical phase shift, and cell volume changed as physiologically expected.

As expected, A′ and V′ of the cell decreased during exposure to hypertonic solution and increased back to baseline upon reperfusion with isotonic solution. In contrast, the optical phase shift had the opposite dependenc and increased with decreasing cell volume. Importantly, M′ showed negligible variation with the osmotic changes, as predicted by Eq. 11. This experimental finding supports the conclusion reached mathematically that the measured quantity M does indeed represent a physical property of a live cell that is independent of the cell water content.

Quantitative measurement of cell dry mass.

The quantity M shown above is a measure of the nonaqueous content of the cell and can therefore be converted to a measure of the cell dry mass. As shown by Baber (4) and Davies and Wilkins (8), the refractive properties of the cell exhibit a strong dependence on total cell protein concentration, as follows:

|

(14) |

where α is the refraction increment (in ml/g) and C is the concentration of dry protein in the solution (in g/ml). Using this relationship, the dry mass surface density (σ) of the cellular matter can be obtained from the measured phase map, φ, as follows:

|

(15) |

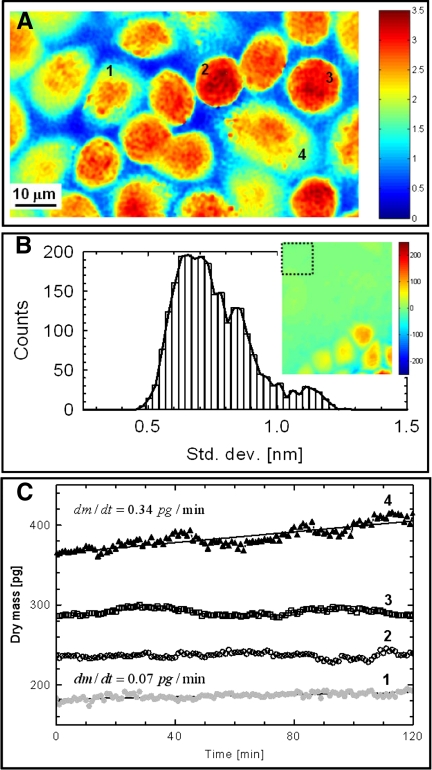

The quantity σ can therefore be used to quantify cell growth noninvasively, using optical images alone. Figure 4A shows an example of dry mass density distribution σ (in pg/μm2) obtained from a typical monolayer of HeLa cells. In applying Eq. 15, we used α = 0.2 ml/g, which corresponds to an average of reported values (4). As shown, in addition to a measure of cell dry mass, the phase image also revealed the overall structure of the cell monolayer as in conventional optical microscopy.

Fig. 4.

A: dry mass density image σ(x,y) of a monolayer of live HeLa cells obtained using Fourier phase microscopy. The color scale bar has units of pg/μm2. 1–4, Cells 1–4. B: nanometer stability of the measurements demonstrated by the histogram of the pathlength SD corresponding to the pixels within a 15 × 15-μm2 acellular area shown in the inset. The color scale bar of the inset indicates optical pathlength in units of nm. C: temporal evolution of the total dry mass content for each of the 4 representative cells shown in A. The solid lines for cells 1 and 4 indicate linear fits. Slopes (m) of the corresponding fits are shown, indicating more rapid growth for cell 4 compared with cell 1. In contrast, cell 2 was essentially static during these measurements, whereas cell 3 showed an oscillatory behavior of unknown origin.

To quantify the sensitivity of the above measurements, we recorded 240 phase images over 2 h from a nearly confluent monolayer of HeLa cells that contained small regions with no cells to be used as an internal reference (Fig. 4B, inset). We measured the pathlength SD of each pixel within a 15 × 15-μm2 region, as indicated by the square box in Fig. 4B, inset. Figure 4B shows the histogram of these SDs. The average SD was 0.75 nm, which demonstrates the subnanometer stability of the instrument and therefore its sensitivity to changes in sample structure as measured by its refractive index n. Using Eq. 15 to translate phase change into dry mass surface density and assuming α = 0.2 ml/g, the 0.75-nm pathlength stability translated into a sensitivity to changes in dry mass surface density of ∼3.75 fg/μm2.

Dynamics of cell growth.

The most direct application of cell dry mass determinations is in the characterization of cell growth. To our knowledge, there are no existing tools for noninvasive measurement and long-term monitoring of cell growth in cultured cell monolayers. To demonstrate this application, data containing time-resolved quantitative phase images of cell monolayers were acquired at a rate of 4 frames/min over periods of up to 12 h. Each cell fully contained in the field of view was segmented using a custom MATLAB program based on iterative image thresholding and binary dilation. We monitored the total dry mass of each cell over a period of 2 h. For example, the total dry mass of the four representative cells (cells 1–4) in Fig. 4A are plotted as a function of time in Fig. 4C. It can be seen that cell 4 exhibited linear growth, as did cell 1, although at a reduced factor of almost 5 (data not shown indicated that cell 4 entered mitosis soon after these measurements). In contrast, cell 2 showed virtually no change in mass, whereas cell 3 appeared to exhibit a slight oscillatory behavior, the origin of which is unclear. These results demonstrate the capability of quantitative phase imaging to measure the dynamics of small changes in cell mass.

To further demonstrate the efficacy of quantitative phase imaging as a high-throughput “optical assay” for the measurement of individual cell growth, we investigated the previously described phenomenon of glucose-induced hypertrophy of kidney mesangial cells in culture (17, 35). Cultured mesangial cells were exposed to different concentrations of glucose to establish differential growth dynamics, as described in experimental procedures. Under each culture condition, 100 individual cells were independently measured by quantitative phase microscopy, and the results were expressed as a distribution of cell dry mass per culture condition (Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5.

Histograms of mesangial cell dry mass for identical cell monolayers grown at two different glucose levels. A: normal glucose levels show cell mass distribution under “physiological” conditions. B: high glucose levels (mimicking diabetes) show cellular hypertrophy as indicated by histogram broadening and shifting to the right.

As expected, the high-glucose culture condition (mimicking the impaired glycemic control condition of diabetes) was associated with prominent mesangial cell hypertrophy, as shown by the widening and shift to the right of the cell mass distribution in Fig. 5B. More than 50% of the cells grown in high glucose had a mass of >400 pg, whereas only 10% of the cells grown in normal glucose had a mass of >400 pg. In addition, none of the cells grown under normal glucose concentrations had dry mass of >600 pg, whereas nearly 10% of cells in the high-glucose condition showed this feature. These results indicate that our optical imaging method can capture the subtle effects of glucose on the overall cell growth behavior of this model system.

Subcellular dynamics of cell mass.

The spatial and temporal distributions of cell mass can provide unique insights into the dynamic properties of subcellular structures. As described in the experimental procedures, we were able to mathematically transform the quantitative phase data to measure the time dependence of MSD associated with various spatial wavelengths (Λ) within the image. This procedure provides insight into the ensemble dynamics of subcellular structures of a given length scale within the imaged cell monolayer. Figure 6 shows the results obtained from a confluent HeLa cell monolayer imaged over a 2-h period at 4 frames/min. We found that over a significant time interval and for all spatial wavelengths studied, the MSD versus time data exhibited power law dependence, as indicated by the straight line behavior in the log-log plot of Fig. 6A. It is well known that when MSD varies linearly with time (MSD ∝ τβ), exponent β = 1 is indicative of diffusive motion, whereas β < 1 and β > 1 define the subdiffusive and superdiffusive regime, respectively (34). When the dependence of exponent β on Λ was studied in the linear regime of 2 < τ < 10 min, two observations became apparent (Fig. 6B). First, β decreased steadily with decreasing Λ over the length scale of 0.05 < Λ < 6 μm (the lower limit of 0.5 μm represents the optical resolution of the instrument), indicating that in the time scale of our experiments, subcellular structures of less than ∼6 μm in length scale are in subdiffusive motion and become increasingly static as Λ approaches 0.5 μm. In contrast, at larger spatial scales (Λ > 6 μm), β approaches 1, indicating that large structures such as nuclei and whole cells are in diffusive motion over the time scale of our experiments. To our knowledge, noncontact, dynamic characterization of large populations of cellular and subcellular structures, such as the results presented here, has never been achieved before.

Fig. 6.

A: mean squared displacements (MSD) versus time lag for cellular dry mass of a live HeLa cell monolayer at various spatial wavelengths (Λ), as indicated on the right. The dotted line indicates a region of linear dependence with exponent β approaching 1 with increasing spatial wavelengths. B: for the linear region highlighted in A, the average exponent of the power law fit β is plotted for various spatial wavelengths (Λ). For size scales of less than ∼6 μm, exponent β is <1, indicating subdiffusive motion. In contrast, β approaches 1 for larger spatial wavelengths, suggesting diffusive motion for larger structures such as whole cells and cell nuclei.

DISCUSSION

Quantitative phase microscopy techniques are rapidly gaining momentum and popularity as new imaging tools in cellular biology. We have previously described the effectiveness of quantitative phase microscopy in characterizing live RBCs (21, 22, 24, 26, 27). Mature RBCs, however, have an optically uniform internal structure, which significantly simplifies mathematical modeling of quantitative phase images. In this report, we present the first demonstration of phase imaging for quantitative characterization of cell mass and growth dynamics in structurally more complex epithelial cells. The tools and experimental methods presented here allow the investigation of cell movement, growth, and subcellular dynamics in essentially any cell type under normal physiological conditions and in a completely noninvasive manner.

The potential of phase microscopy for the determination of cellular dry mass as a fundamental physical property was recognized several decades ago (4, 8). However, practical realization of this potential has remained elusive for lack of appropriate optical methods. Here, we demonstrate how the surface integral of the optical phase shift through a cell layer can be translated into an estimation of the cellular dry mass. Given that quantitative phase microscopy methods can readily generate this surface integral as a function of time, they are ideally suited for the study of time-dependent cell mass changes. In other words, these novel microscopic techniques can noninvasively quantify cell growth, hypertrophy, or atrophy as a function of time in culture. Furthermore, since these methods are truly noninvasive and require no cell preparation of any sort, there is no limitation to the period of observation, which can last from minutes to days. In this report, we demonstrate two potential assays for the analysis of individual cells in culture (Figs. 3 and 4) or for statistical measurement of large populations of cells (Figs. 5 and 6).

In addition to providing expected morphometric information such as shape, volume, and mass, time-dependent evolution of quantitative phase maps are related to spatial and temporal distributions of cell mass as a function of size. Thus, we are able to measure the time dependence of MSD associated with various spatial wavelengths, providing dynamics of cellular and subcellular structures within the imaged cell monolayer (Fig. 6). Similar information about dynamics of individual cells or large cellular components such as cell nuclei can potentially be obtained using conventional microscopy techniques, but essentially all such existing methods require the ability to tag or a priori identify specific components within each image. Furthermore, essentially all traditional methods collect data one or a few targets at a time, often limiting the statistical power of the individual assay. In contrast, quantitative phase imaging requires no exogenous labels or tags, does not rely on the morphometric identification of the components of interest, and collects large sets of data from multiple targets simultaneously. To our knowledge, such high-throughput statistical information about a cell population has not been reported before.

The primary limitation of the technique presented here is that it provides whole cell dynamic data that currently lack specificity for individual subcellular targets. In contrast, existing strategies for study of cell dynamics such as tracking of microbeads targeted to the cell surface integrins have enabled detailed characterization of cytoskeleton-associated cellular dynamics (15, 16, 31, 33), and a similar experimental approach may conceivable be used to target other cell surface regions or intracellular organelles. This experimental difference (whole cell vs/ subcellular regions) likely explains the difference between our MSD data (Fig. 6) and those previously reported for subcellular components such as cytoplasmic granules (38) or cytoskeleton-associated dynamics (16, 33). We are currently working to better understand the physical basis and biological significance of whole cell dynamic data. In addition, we have shown that a combination of quantitative phase techniques and microbead targeting may provide an alternative method for high-throughput analysis of specific cell surface dynamics (3).

In summary, we have presented novel microscopic methodology for noninvasive imaging and characterization of cellular mass and growth dynamics. This approach is based on interferometric quantitative phase microscopy techniques that have been recently developed in our laboratory and are completely noninvasive as they use the cellular refractive index as the source of microscopic contrast. Although cellular dry mass has long been considered an important physical property, biological applications of the cell dry mass as an experimental tool have been limited due to the lack of readily accessible methods. With the tools and methods presented here, the quantitative measurement of cellular dry mass and its spatial and temporal dynamics are placed on a solid physical background and made available as a practical microscopic assay. As such, the experiments presented in this report demonstrate that quantitative phase microscopy is an valuable optical assay for dynamic studies of cell growth and for the physical characterization of cellular motions under normal physiological conditions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Center for Research Resources Research Grant P41-RR-02594 and by Hamamatsu Photonics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark Lessard and Joerg Bewersorf for measuring the refractive index of the NaCl solution. This work was conducted at the George R. Harrison Spectroscopy Laboratory.

Present address of G. Popescu: Quantitative Light Imaging Laboratory, Dept. of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801.

Present address of C. Best-Popescu: Depts. of Basic and Clinical Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akkin T, Dave DP, Milner TE, Rylander HG. Detection of neural activity using phase-sensitive optical low-coherence reflectometry. Opt Express 12: 2377–2386, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allman BE, McMahon PJ, Tiller JB, Nugent KA, Paganin D, Barty A, McNulty I, Frigo SP, Wang YX, Retsch CC. Noninterferometric quantitative phase imaging with soft x rays. J Opt Soc Am A 17: 1732–1743, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amin MS, Park Y, Lue N, Dasari RR, Badizadegan K, Feld MS, Popescu G. Microrheology of red blood cell membranes using dynamic scattering microscopy. Opt Express 15: 17001–17009, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baber R Interference microscopy and mass determination. Nature 169: 366–367, 1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajt S, Barty A, Nugent KA, McCartney M, Wall M, Paganin D. Quantitative phase-sensitive imaging in a transmission electron microscope. Ultramicroscopy 83: 67–73, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi W, Fang-Yen C, Badizadegan K, Oh S, Lue N, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Tomographic phase microscopy. Nat Med 4: 717–719, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choma MA, Ellerbee AK, Yang CH, Creazzo TL, Izatt JA. Spectral-domain phase microscopy. Opt Lett 30: 1162–1164, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies HG, Wilkins MHF. Interference microscopy and mass determination. Nature 161: 541, 1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn GA, Zicha D. Phase-shifting interference microscopy applied to the analysis of cell behaviour. Symp Soc Exp Biol 47: 91–106, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang-Yen C, Chu MC, Seung HS, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Noncontact measurement of nerve displacement during action potential with a dual-beam low-coherence interferometer. Opt Lett 29: 2028–2030, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garnett MJC Colours in metal glasses and in metallic films. Philo Trans Roy Soc Lond Series A 203: 385–420, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeda T, Popescu G, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Hilbert phase microscopy for investigating fast dynamics in transparent systems. Opt Lett 30: 1165–1168, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwai H, Fang-Yen C, Popescu G, Wax A, Badizadegan K, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Quantitative phase imaging using actively stabilized phase-shifting low-coherence interferometry. Opt Lett 29: 2399–2401, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joo C, Akkin T, Cense B, Park BH, de Boer JE. Spectral-domain optical coherence phase microscopy for quantitative phase-contrast imaging. Opt Lett 30: 2131–2133, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenormand G, Bursac P, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Out-of-equilibrium dynamics in the cytoskeleton of the living cell. Phys Rev 76: 041901, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenormand G, Chopin J, Bursac P, Fredberg JJ, Butler JP. Directional memory and caged dynamics in cytoskeletal remodelling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 360: 797–801, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahimainathan L, Das F, Venkatesan B, Choudhury GG. Mesangial cell hypertrophy by high glucose is mediated by downregulation of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Diabetes 55: 2115–2125, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann CJ, Yu LF, Lo CM, Kim MK. High-resolution quantitative phase-contrast microscopy by digital holography. Opt Express 13: 8693–8698, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marquet P, Rappaz B, Magistretti PJ, Cuche E, Emery Y, Colomb T, Depeursinge C. Digital holographic microscopy: a noninvasive contrast imaging technique allowing quantitative visualization of living cells with subwavelength axial accuracy. Opt Lett 30: 468–470, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paganin D, Nugent KA. Noninterferometric phase imaging with partially coherent light. Phys Rev Lett 80: 2586–2589, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park YK, Popescu G, Badizadegan K, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Diffraction phase and fluorescence microscopy. Opt Exp 14: 8263, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popescu G, Badizadegan K, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Observation of dynamic subdomains in red blood cells. J Biomed Opt Lett 11: 040503, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popescu G, Deflores LP, Vaughan JC, Badizadegan K, Iwai H, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Fourier phase microscopy for investigation of biological structures and dynamics. Opt Lett 29: 2503–2505, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popescu G, Ikeda T, Best CA, Badizadegan K, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Erythrocyte structure and dynamics quantified by Hilbert phase microscopy. J Biomed Opt Lett 10: 060503, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popescu G, Ikeda T, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Diffraction phase microscopy for quantifying cell structure and dynamics. Opt Lett 31: 775–777, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popescu G, Ikeda T, Goda K, Best-Popescu CA, Laposata M, Manley S, Dasari RR, Badizadegan K, Feld MS. Optical measurement of cell membrane tension. Phys Rev Lett 97: 218101, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popescu G, Park Y, Choi W, Dasari RR, Feld MS, Badizadegan K. Imaging red blood cell dynamics by quantitative phase microscopy. Blood Cells Mol Dis 41: 10–16, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popescu G, Park YK, Dasari RR, Badizadegan K, Feld MS. Coherence properties of red blood cell membrane motions. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 76: 031902, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rylander CG, Dave DP, Akkin T, Milner TE, Diller KR, Welch AJ. Quantitative phase-contrast imaging of cells with phase-sensitive optical coherence microscopy. Opt Lett 29: 1509–1511, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith FH Microscopic interferometry. Research (Lond) 8: 385, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stamenovic D, Rosenblatt N, Montoya-Zavala M, Matthews BD, Hu S, Suki B, Wang N, Ingber DE. Rheological behavior of living cells is timescale-dependent. Biophys J 93: L39–41, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens DJ, Allan VJ. Light microscopy techniques for live cell imaging. Science 300: 82–86, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trepat X, Deng L, An SS, Navajas D, Tschumperlin DJ, Gerthoffer WT, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell. Nature 447: 592–595, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waigh TA Microrheology of complex fluids. Rep Prog Phys 68: 685–742, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolf G, Schroeder R, Zahner G, Stahl RA, Shankland SJ. High glucose-induced hypertrophy of mesangial cells requires p27(Kip1), an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. Am J Pathol 158: 1091–1100, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang C, Wax A, Hahn MS, Badizadegan K, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Phase-referenced interferometer with subwavelength and subhertz sensitivity applied to the study of cell membrane dynamics. Opt Lett 26: 1271–1273, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang CH, Wax A, Georgakoudi I, Hanlon EB, Badizadegan K, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Interferometric phase-dispersion microscopy. Opt Lett 25: 1526–1528, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yap B, Kamm RD. Mechanical deformation of neutrophils into narrow channels induces pseudopod projection and changes in biomechanical properties. J Appl Physiol 98: 1930–1939, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zernike F How I discovered phase contrast. Science 121: 345, 1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zicha D, Dunn GA. An image-processing system for cell behavior studies in subconfluent cultures. J Microsc 179: 11–21, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zicha D, Genot E, Dunn GA, Kramer IM. TGF beta 1 induces a cell-cycle-dependent increase in motility of epithelial cells. J Cell Sci 112: 447–454, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]