Abstract

Induction of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is associated with potential antifibrogenic effects. The effects of HO-1 expression on epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which plays a critical role in the development of renal fibrosis, are unknown. In this study, HO-1−/− mice demonstrated significantly more fibrosis after 7 d of unilateral ureteral obstruction compared with wild-type mice, despite similar degrees of hydronephrosis. The obstructed kidneys of HO-1−/− mice also had greater macrophage infiltration and renal tubular TGF-β1 expression than wild-type mice. In addition, the degree of EMT was more extensive in obstructed HO-1−/− kidneys, as assessed by α-smooth muscle actin and expression of S100A4 in proximal tubular epithelial cells. In vitro studies using proximal tubular cells isolated from HO-1−/− and wild-type kidneys confirmed these observations. In conclusion, HO-1 deficiency is associated with increased fibrosis, tubular TGF-β1 expression, inflammation, and enhanced EMT in obstructive kidney disease. Modulation of the HO-1 pathway may provide a new therapeutic approach to progressive renal diseases.

Unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) is a well-characterized experimental model of renal injury leading to tubulointerstitial fibrosis (reviewed in references1, 2). Numerous factors, including proteins involved in apoptosis, chemoattractants, growth factors, adhesion proteins, and matrix/basement membrane proteins, are increased in obstructed kidneys.1 Among the various factors associated with this model, TGF-β (including TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3) is regarded as critical in leading to fibrosis and recruitment of inflammatory cells, especially macrophages. TGF-β is a crucial mediator of epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), a key process in the generation of interstitial fibroblasts.3–5 EMT is recognized as a loss of epithelial cell phenotype, involving, among others, decrease of intercellular epithelial adhesion molecules, such as E-cadherin, with a concomitant development of mesenchymal phenotype, including expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), vimentin, and S100A4, also known as fibroblast-specific protein-1 (FSP-1).4–8 Mesenchymal markers are induced by several growth factors, including TGF-β.7, 9–11

TGF-β1, an isoform of TGF-β, also induces a cytoprotective enzyme, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), in renal proximal tubular cells.12, 13 HO-1 is the rate-limiting enzyme in the degradation of heme and results in the release of equimolar quantities of biliverdin, iron, and carbon monoxide (CO).14 The physiologic importance of HO-1 and its products as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective agents has been demonstrated in many studies and reviewed.15–18 HO-1 is upregulated in several disease models, including UUO.19–21 The effects of HO-1 expression on EMT are unknown.

Recently, it was shown that preinducing HO-1 in the rat, by administration of hemin, decreased renal levels of TGF-β (TGF-β1 plus TGF-β2) and suppressed UUO-mediated tubulointerstitial fibrosis in the obstructed kidney through an antiapoptotic pathway involving Bcl-2.22 The protective effect of hemin was partially blocked by the addition of zinc protoporphyrin, an HO activity inhibitor.22 EMT was not examined in this study. It is widely recognized that chemical modulators of HO-1 have several nonspecific effects beyond altering HO enzyme activity, including activating/inhibiting the nitric oxide synthase pathway.23–25 Thus, to evaluate the role of HO-1 in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis, we studied the effects of HO-1 deficiency using HO-1-knockout (HO-1−/−) mice on the progression of renal fibrosis in association with macrophage recruitment, TGF-β1 expression, and EMT after UUO. Furthermore, primary renal proximal tubular epithelial cell cultures generated from HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice were analyzed for TGF-β1–mediated EMT.

RESULTS

Lack of HO-1 Augments the Development of Renal Fibrosis after UUO

Hydronephrosis was assessed semiquantitatively on the basis of a scoring system described by Vora et al.26 As expected, the degree of hydronephrosis was increased in the obstructed kidneys of both the HO-1−/− and HO-1+/+ mice (1.75 ± 0.19 and 1.75 ± 0.11, respectively) compared with sham-operated HO-1−/− and HO-1+/+ mice (0.66 ± 0.33 and 0.50 ± 0.22, respectively; P < 0.01 obstructed versus CL; Supplemental Figure 1); however, there was no difference in the degree of hydronephrosis between the two HO-1 genotypes (NS). Immunohistochemical staining and immunoblot analysis were performed and confirmed that HO-1 was upregulated in renal tubules of the obstructed kidneys of the HO-1+/+ mice, as reported previously,19–21 and confirmed the lack of HO-1 expression in the HO-1−/− mice (Supplemental Figure 2). An approximately two-fold increase in HO-1 protein was noted at day 7 after UUO in the HO-1+/+ mouse kidney lysates compared with sham-operated control and contralateral (CL) kidneys (Supplemental Figure 2B).

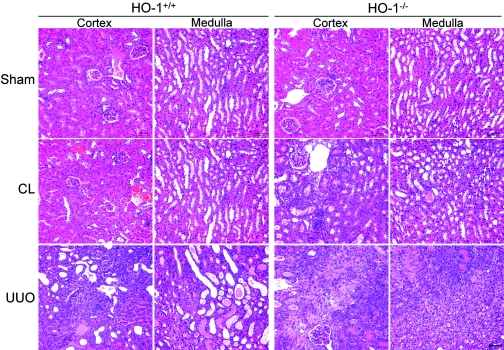

Figure 1.

Histologic changes of cortex and medulla in the kidneys of HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice. Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of renal cortex and medulla sections from sham-operated (Sham) mice, as well as sections from obstructed (UUO) and CL kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (left) and HO-1−/− (right) mice on day 7. The CL kidney of HO-1−/− mouse, one of three cases showing histologic changes (shown), has increased interstitial fibrosis compared with normal appearances of sham-operated kidneys of both groups and the CL kidney of HO-1+/+ mouse. HO-1+/+ sham (n = 3), HO-1−/− sham (n = 3), HO-1+/+ CL and UUO (n = 9), and HO-1−/− CL and UUO kidneys (n = 7). Bar = 100 μm.

Figure 2.

Higher magnification showing the degree of fibrosis in the obstructed kidneys of HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice. (A) Wedge-shaped area selected for analysis is shown. The green box represents the ×100 light microscopic field used to cover most of the wedge-shaped area including cortex and partial medulla along the papillary axis. (B) Representative Masson's trichrome stained sections of the renal cortex and partial medulla from sham-operated (Sham; top) mice, as well as sections from obstructed (UUO; bottom) and CL (middle) kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (left) and HO-1−/− (right) mice on day 7. Bar = 100 μm. CMJ, corticomedullary junction. (C) Graph of fibrotic area identified by color image analyzer. HO-1+/+ sham (n = 3); HO-1−/− sham (n = 3); HO-1+/+ CL and UUO (n = 9); HO-1−/− CL and UUO kidneys (n = 7). *P < 0.05 versus all other groups. (D) Representative western blot analysis (top) for Fn protein of kidney lysates was performed as described in the Concise Methods section. HO-1+/+ sham (n = 3); HO-1−/− sham (n = 3); HO-1+/+ CL and UUO (n = 7); HO-1−/− CL and UUO kidneys (n = 4). The densitometry of Fn was normalized to β-actin and graphed (bottom). *P < 0.05 versus all other groups. Magnification, ×100.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed marked tubular dilation and atrophy associated with interstitial fibrosis and inflammatory cell infiltration in the obstructed kidneys from both HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice (Figure 1). The degree of these changes was more severe in HO-1−/− mice. Interestingly, three of seven CL kidneys from HO-1−/− mice also had interstitial fibrosis and inflammatory cell infiltration, although less severe than that observed in obstructed kidneys. No pathologic changes were noted in the kidneys from sham-operated mice.

The analysis of Masson trichrome staining (Figure 2) in the wedge-shaped area along the papillary axis (Figure 2A) revealed that the fibrosis in the obstructed kidneys was more severe in HO-1−/− than in HO-1+/+ mice (2.13-fold; P < 0.05; Figure 2, B and C). Although mild, the fibrosis affecting the CL kidneys was more pronounced in HO-1−/− mice; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.07; Figure 2, B and C). Western blot analysis demonstrated a significantly higher expression of fibronectin (Fn) in the obstructed kidneys from the HO-1−/− mice as compared with the other experimental groups (2.59-fold; P < 0.01; Figure 2D).

HO-1 Deficiency in Obstructed Kidneys Promotes Recruitment of Macrophages

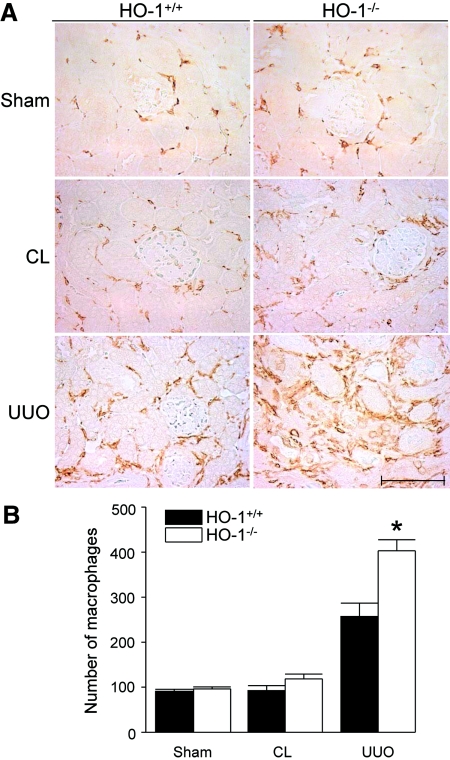

A few F4/80-positive cells were observed in the interstitium of sham-operated kidneys of both HO-1−/− and HO-1+/+ mice without statistical numerical difference between them (Figure 3). The numbers of F4/80-positive cells in the CL kidneys from HO-1−/− and HO-1+/+ mice were not significantly different (118.6 ± 10.6 versus 92.4 ± 11.3, respectively; NS). In the obstructed kidneys from both HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice, the numbers of macrophages were markedly increased, mainly in the periglomerular and peritubular areas. The numbers of F4/80-positive cells in the obstructed HO-1−/− kidneys were significantly higher as compared with obstructed kidneys from HO-1+/+ mice (402.9 ± 24.8 versus 257.3 ± 29.7, respectively; P < 0.05; Figure 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

F4/80+ cells in HO-1+/+ compared with HO-1−/− mice. (A) Representative F4/80-stained sections from sham-operated (Sham) mice, as well as sections from obstructed (UUO) and CL kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (left) and HO-1−/− (right) mice on day 7. A CL kidney of HO-1−/− showing higher numbers of recruited macrophages compared with the CL kidney of HO-1+/+ mouse is shown. Bar = 100 μm. (B) The graph represents the total F4/80-positive cells counted from five contiguous HPF (×400) per kidney section as described in the Concise Methods section. HO-1+/+ sham (n = 3); HO-1−/− sham (n = 3); HO-1+/+ CL and UUO (n = 9); HO-1−/− CL and UUO kidneys (n = 7). *P < 0.05 versus all other groups.

TGF-β1 Expression Correlates with the Degree of Renal Fibrosis in the UUO Model and Is Augmented by the Lack of HO-1

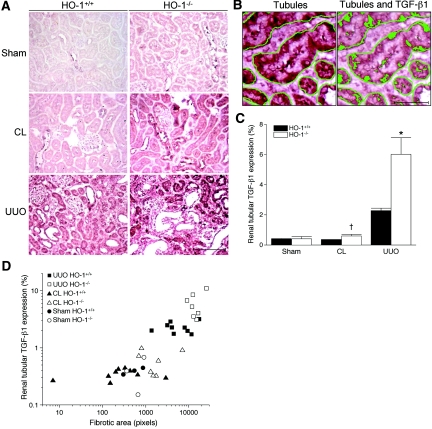

TGF-β1 in the kidney lysates was quantified by ELISA (Table 1) and showed that TGF-β1 was higher in the obstructed kidneys of the HO-1 knockout mice compared with all other groups (P < 0.01). As measured by immunohistochemistry, the expression of TGF-β1 in renal tubules in the sham-operated kidneys and in the CL kidneys was negligible (Figure 4A); however, the obstructed kidneys from both HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice had increased expression of TGF-β1 (Figure 4A). Immunostaining for TGF-β1, lotus lectin (proximal tubule marker), and peanut agglutinin (distal tubule marker) on serial sections of obstructed kidneys of HO-1 knockout mice demonstrated that TGF-β1 staining occurs predominantly in both proximal and distal tubules (Supplemental Figure 3). Occasional interstitial infiltrating cells were also positive. The TGF-β1 expression in the renal tubules was significantly higher in the obstructed kidneys from HO-1−/− mice as compared with those from HO-1+/+ mice (2.64-fold; P < 0.001; Figure 4C). Similarly, the CL kidney from HO-1−/− mice showed significantly higher TGF-β1 expression in renal tubules as compared with CL kidney from HO-1+/+ mice (P < 0.05; Figure 4C). Importantly, the increased tubular expression of TGF-β1 correlated with the increased fibrosis among the groups (Pearson's correlation coefficient [r] = 0.8265; coefficient of determination [r2] = 0.6831, r is significantly different from zero with the two-tailed P < 0.0001; Figure 4D).

Table 1.

TGF-β1 levels quantified by ELISAa

| Condition | HO-1+/+ | HO-1−/− |

|---|---|---|

| Sham | 627.650 ± 107.100 | 1086.600 ± 210.630 |

| Contralateral | 1529.100 ± 402.550 | 1087.700 ± 75.201 |

| UUO | 2130.100 ± 914.340 | 5737.900 ± 767.550b |

pg TGF-β1/mg total protein ± SEM; n = 2 to 3 mice per group.

P < 0.01 versus all other groups

Figure 4.

Comparison of TGF-β1 expression in the kidneys of HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice. (A) Representative immunohistochemical staining for TGF-β1 from sham-operated (Sham) mice, as well as sections from obstructed (UUO) and CL kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (left) and HO-1−/− (right) mice on day 7. The representative CL kidney of HO-1−/− mouse (one of three cases showing histologic changes and increased TGF-β1 expression, compared with the sham kidney) is shown. Bar = 100 μm. (B) TGF-β1–expressing areas were counted by a color image analyzer as a proportion of positively stained area to the total cross-sectional area of renal tubules selected along the basement membrane in each HPF. First, renal tubules are identified by color image analyzer (left) followed by identification of TGF-β1–expressing areas within the tubules (right). Bar = 20 μm. (C) Graphic representation of mean proportion (%) of TGF-β1–expressing area in the renal tubule of five HPF (×400) per kidney section. *P < 0.05 versus obstructed kidney of HO-1+/+ mice; †P < 0.005 versus the CL kidney of HO-1+/+ mice. (D) Correlation graphs of renal tubular–TGF-β1 expression versus the degree of the fibrosis in renal sections from sham-operated (Sham; circles) mice, as well as sections from obstructed (UUO; squares) and CL (triangles) kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (closed symbols) and HO-1−/− (open symbols) mice on day 7. r = 0.8265, r2 = 0.6831; r is significantly different from zero with the two-tailed P < 0.0001. HO-1+/+ sham (n = 3); HO-1−/− sham (n = 3); HO-1+/+ CL and UUO (n = 9); HO-1−/− CL and UUO kidneys (n = 7).

Expression of EMT Markers Is Higher in HO-1–Deficient Kidneys after UUO

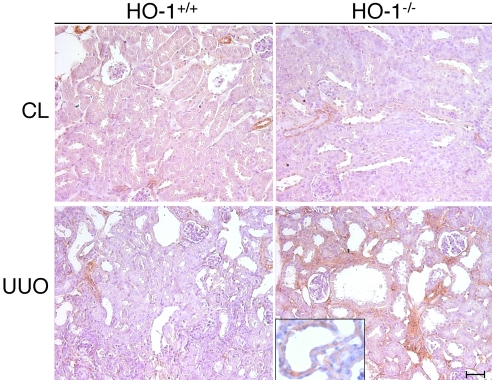

The expression of α-SMA, a mesenchymal marker, was more pronounced in the obstructed kidneys of HO-1−/− compared with HO-1+/+ mice and was detected in both the tubular epithelial cells and interstitial cells (Figure 5). A higher magnification image of an α-SMA–stained renal tubule shows increased α-SMA in the HO-1−/− kidney after UUO (Figure 5, inset). α-SMA expression was not observed in tubular or interstitial cells in the sham-operated mice (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Comparison of α-SMA expression in the kidneys of HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice. Representative immunohistochemical staining for α-SMA from obstructed (UUO) and CL kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (left) and HO-1−/− (right) mice on day 7. Bar = 100 μm. HO-1+/+ CL and UUO (n = 3); HO-1−/− CL and UUO kidneys (n = 3). (Inset) Higher magnification image of a renal tubule with positive staining for α-SMA in an obstructed HO-1−/− kidney.

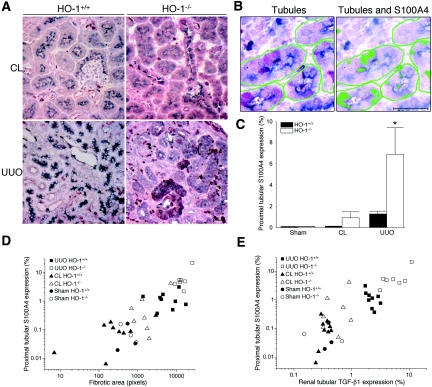

The proximal tubular epithelial cells, identified by lotus lectin, in kidneys from sham-operated HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice (data not shown) as well as CL kidneys from HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice showed very scarce S100A4 expression (Figure 6A). Although the S100A4 expression was increased in a few of the CL kidneys from HO-1−/− mice, there was no significant difference between the two HO-1 genotypes. The obstructed kidneys demonstrated a marked increase in proximal tubular S100A4 expression, and this increase was significantly higher in the HO-1−/− group (5.43-fold; P < 0.05; Figure 6, A and C). The increased proximal tubular S100A4 expression correlated with both the degree of the fibrosis among the groups (r = 0.7761 [95% confidence interval 0.6070 to 0.8780], r2 = 0.6024; r is significantly different from zero with the two-tailed P < 0.0001; Figure 6D) and TGF-β1 expression (r = 0.8308 [95% confidence interval 0.6959 to 0.9091], r2 = 0.6902; r is significantly different from zero with the two-tailed P < 0.0001; Figure 7E) in the tubules among the groups.

Figure 6.

EMT in obstructed kidneys of HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice. (A) Representative double immunohistochemical staining using S100A4 (purple) and lotus lectin (gray blue) from obstructed (UUO) and CL kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (left) and HO-1−/− (right) mice on day 7. Bar = 20 μm. (B) S100A4-expressing proximal tubules are counted by identifying renal tubules (lotus lectin) by color image analyzer (left) followed by identification of S100A4-expressing areas within the tubules (right). Bar = 20 μm. (C) Graph of proximal tubules expressing S100A4 in five HPF (×400) per kidney section from sham-operated (Sham) mice, as well as from obstructed (UUO) and CL kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (left) and HO-1−/− (right) mice. *P < 0.05 versus all other groups. (D) Correlation graph of proximal tubular expression of S100A4 (EMT) versus the degree of the fibrosis in kidneys from sham-operated (Sham; circles) mice, as well as sections from obstructed (UUO; squares) and CL (triangles) kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (closed symbols) and HO-1−/− (open symbols) mice on day 7. r = 0.7761, (95% confidence interval 0.6070 to 0.8780), r2 = 0.6024; r is significantly different from zero with the two-tailed P < 0.0001. (E) Correlation graph of proximal tubular expression of S100A4 (EMT) versus the renal tubular expression of TGF-β1 in kidneys from sham-operated (Sham; circles) mice, as well as sections from obstructed (UUO; squares) and CL (triangles) kidneys of both HO-1+/+ (closed symbols) and HO-1−/− (open symbols) mice on day 7. r = 0.8308 (95% confidence interval 0.6959 to 0.9091), r2 = 0.6902; r is significantly different from zero with the two-tailed P < 0.0001. HO-1+/+ sham (n = 3); HO-1−/− sham (n = 3); HO-1+/+ CL and UUO (n = 9); HO-1−/− CL and UUO kidneys (n = 7).

Figure 7.

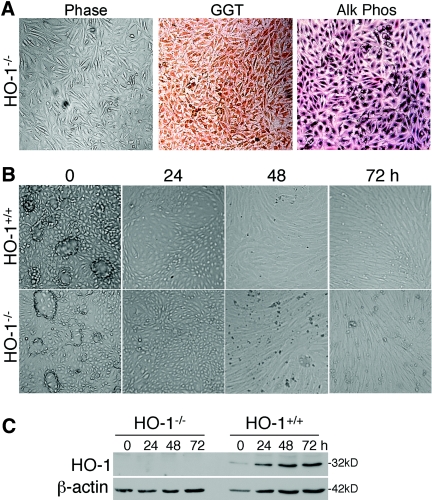

Characterization of primary proximal tubular epithelial cell cultures derived from HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice. (A) Staining of HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− primary proximal tubular epithelial cell cultures demonstrating expression of proximal tubular epithelial cell markers, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (Alk Phos). (B) Phase-contrast images of HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− proximal tubular epithelial cell cultures showing domes in confluent cells (0 h, vehicle treated) of each genotype and phenotypic changes in response to TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) with time, as indicated. (C) Immunoblot from cell lysates from HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− proximal tubular epithelial cell cultures treated with vehicle (0 h) or TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for the times indicated. Blots were stripped and reprobed for β-actin to confirm loading and transfer. Representative of n = 4 independent cell cultures from separate mice/genotype.

Repeated measures ANOVA indicated that there were significant effects for both kidney type (UUO versus CL) and knockout status for all three dependent variables (fibrosis, TGF-β, and S100A4). The obstructed kidney was always more impaired than the CL kidney (averaged across knockout status), and the HO-1−/− was always worse than the HO-1+/+ (averaged across kidney type: UUO or CL; all P ≤ 0.05). The interaction between HO-1−/− and kidney type was significant at P < 0.05 for TGF-β but only marginally significant (P < 0.06) for fibrosis and S100A4. The interaction suggests that the impact of kidney obstruction varies across HO-1−/− versus HO-1+/+ mice. Difference scores for each variable (UUO and CL) were computed, and a t test on the difference was performed. The obstruction produced greater impairment in the HO-1−/− than the HO-1+/+ kidney, and the P values were the same as for the interaction in the repeated measures ANOVA (P < 0.05 for TGF-β1 and <0.06 for fibrosis and S100A4).

TGF-β1–Mediated EMT Is Increased in Primary Mouse HO-1–Deficient Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells

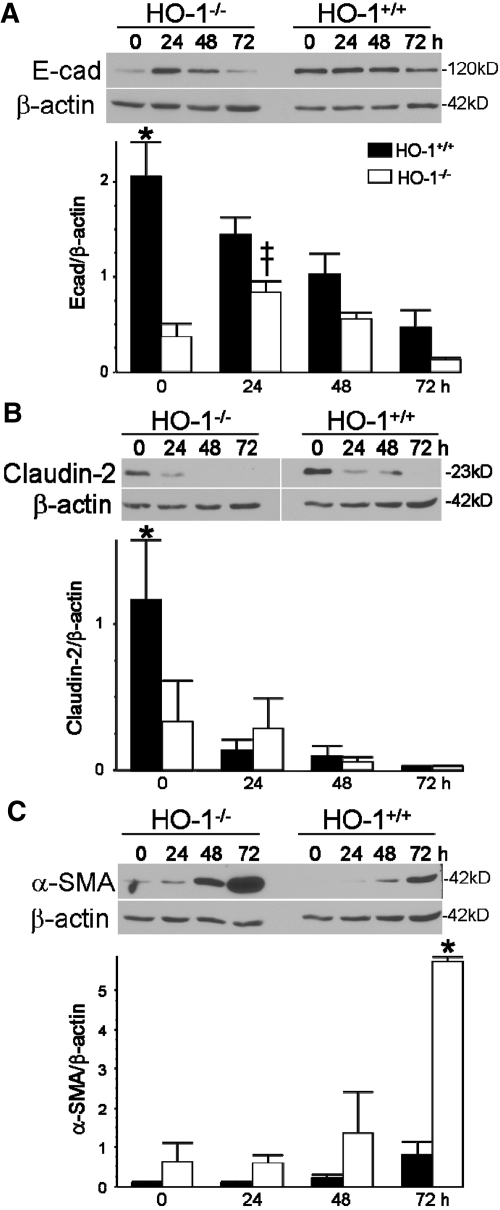

For determination of whether TGF-β1 mediates EMT in proximal tubules, primary proximal tubular epithelial cells from HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice were generated. The primary cells stained positive for the proximal tubular epithelial cell markers γ-glutamyltranspeptidase and alkaline phosphatase (Figure 7A).27 Cells from both genotypes seemed morphologically similar and when confluent formed multicellular domes (Figure 7B).27 TGF-β1 induced HO-1 in the HO-1+/+ cells but not the HO-1−/− cells (Figure 7C). Both HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− cells responded to exogenous TGF-β1 by increased EMT (Figure 8). In response to TGF-β1, E-cadherin and claudin-2 decreased in both genotypes (Figure 8, A and B), which paralleled the disorganization of the domes seen on phase contrast (Figure 7B). α-SMA increased in both genotypes in response to TGF-β1 but was more pronounced in the knockout cell cultures (Figure 8C). We observed that primary cells derived from HO-1−/− mice have more EMT (decreased E-cadherin and claudin-2 and increased α-SMA) compared with cells derived from wild-type mice (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

EMT in HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− primary proximal tubular epithelial cell cultures. Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates from HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− primary proximal tubular epithelial cell cultures treated with vehicle (0 h) or TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for the times indicated. The blots were stripped and reprobed for β-actin to confirm loading and transfer. (A) E-cadherin (E-cad) immunoblot (top) and densitometry of E-cad/β-actin (arbitrary units; bottom). (B) Claudin-2 (top) and densitometry of claudin-2/β-actin (arbitrary units; bottom). (C) α-SMA (top) and densitometry of α-SMA/β-actin (arbitrary units; bottom). *P < 0.05 versus all other groups; ‡P < 0.05 versus HO-1+/+. Densitometry derived from n = 4 independent experiments from cell cultures from separate mice/genotype.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that renal fibrosis, inflammation, and EMT are exaggerated in HO-1–deficient mice in a UUO model of fibrosis. Tubular TGF-β1 expression and macrophage numbers were higher in the obstructed kidneys of the HO-1−/− mice compared with the wild-type mice. Concomitantly, EMT was higher in the HO-1–deficient mice. Notably, the expression of tubular S100A4 (FSP-1) was significantly higher (5.43-fold) in the obstructed kidneys from HO-1−/− mice compared with the HO-1+/+ group. In vitro studies demonstrated that TGF-β1 increased EMT in primary proximal tubular epithelial cell cultures from both genotypes, with HO-1–deficient cells exhibiting increased EMT (using claudin-2, E-cadherin, and α-SMA as markers) compared with wild-type cells. This is the first demonstration that the expression of HO-1 modulates EMT.

The accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) is a final common pathway of most forms of kidney disease, including obstruction. A significant proportion of matrix is derived through the process of EMT. The progression of EMT to tubulointerstitial fibrosis has been succinctly described in a recent review by Burns et al.28 Cells undergoing EMT exhibit loss of polarity, decreased cell–cell contacts, and adhesion, leading to increased cell migration and increased ECM production.28 A major phenotypic change toward EMT begins when cells express a combination of epithelial and mesenchymal markers, including FSP-1 and α-SMA, associated with reorganization of the cytoskeletal proteins, disruption of the tubular basement membrane, and upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and metalloproteinase-9.28 It was recently shown that fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and macrophages (by measuring FSP-1, α-SMA, and F4/80, respectively) are increased in mouse kidneys 7 d after UUO, indicating the activation of EMT.29, 30

Numerous factors are upregulated after ureteral obstruction, including macrophages, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), and TGF-β (reviewed in references1, 2, 31, 32). Macrophages are regarded as a key source of cytokines associated with fibrosis.1, 33, 34 TGF-β, expressed by both tubular epithelial cells and macrophages as a consequence of macrophage–tubular cell interactions, is regarded as an important growth factor in the development of interstitial fibrosis.35 TGF-β increases the expression of metalloproteinase inhibitors with concomitant downregulation of metalloproteinases and enhances the formation of ECM proteins, such as collagen and Fn.1, 36, 37 Through this pathway, proximal tubular epithelial cells collaborate with macrophages, leading to interstitial fibrosis in the injured kidney.

Macrophage infiltration is preceded by local expression of chemokines, such as the proinflammatory cytokine MCP-1, chemokine receptors, and adhesion molecules.2 Whereas HO-1 downregulates the inflammatory response in both renal and nonrenal tissues,18, 38 repeated exposure of HO-1−/− mice to heme proteins leads to intense interstitial cellular inflammation with significant increase in the expression of MCP-1.39 Proximal tubular cells overexpressing HO-1 had lower MCP-1 mRNA and protein expression in response to albumin, compared with similarly treated control cells.40 In addition, it was demonstrated that whereas basal MCP-1 expression in some tissues, such as heart and bone marrow, was comparable in both HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice, renal and plasma MCP-1 were elevated in unstressed and stressed HO-1−/− mice.41 In this study, the number of macrophages in the kidneys from the sham-operated group and the CL (right) kidneys did not differ between the two HO-1 genotypes but was significantly higher in the obstructed kidneys of HO-1−/− mice. Interestingly, the amount of fibrosis seemed to affect the CL kidneys from HO-1−/− mice more than in the respective kidneys from HO-1+/+ mice, with a trend toward statistical significance (P = 0.07), suggesting a systemic effect of the inflammatory process, perhaps caused by differences in resident and circulating cytokines.

Several factors are involved in EMT and fibrosis after UUO. However, TGF-β has been shown to be a key mediator in EMT through its affects on markers, such as decreased expression of E-cadherin and claudins, as well as increased α-SMA and S100A4.7, 10, 42 S100A4 is a member of the S100 family of Ca2+-binding proteins and the human homologue of mouse FSP-1.43, 44 TGF-β is regarded as one of the major contributors to the transition of renal tubular epithelial cells to ECM-producing myofibroblasts.5, 8, 45 For example, treatment with bone morphogenic protein-1, which counteracts the downstream mediators of TGF-β signaling (Smad proteins), restores the initial phenotypic changes induced by TGF-β.46 Smad3-deficient mice are protected against UUO-mediated tubulointerstitial fibrosis because of the inability of TGF-β to recruit monocytes (including F4/80-positive interstitial macrophages), induce EMT, and accumulate collagen.47

It has been suggested that TGF-β–induced EMT is mediated, at least in part, through reactive oxygen species.48, 49 Thus, HO-1 activity, through its antioxidant properties, may impair oxidant formation and, hence, reduce EMT. HO-1 protein is upregulated in the obstructed kidney as early as 6 h after UUO and persists up to at least 7 d.20, 21 In this study, HO-1 was expressed in the renal tubules in the sham and CL kidneys of HO-1+/+ mice and was markedly increased in the obstructed kidneys. HO-1 induction has been previously shown to have antifibrotic effects. We and others have demonstrated that collagen I and Fn production inversely correlates with HO-1 expression.50, 51 Products of HO-1 reaction, CO, and/or bilirubin (converted from biliverdin by biliverdin reductase) have been shown to possess antifibrogenic properties.51–57 For example, CO and bilirubin were protective in a model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis.56, 57 In the case of bilirubin, reduced fibrosis was attributed, in part, to inhibition of both inflammation and TGF-β production.56, 57 Interestingly, it was also demonstrated that HO-1 overexpression, using retroviral gene transfer, markedly inhibited TGF-β mRNA and protein expression in a rat lung microvessel endothelial cell line.58 In these studies, the obstructed kidneys of HO-1–deficient mice have higher levels of TGF-β1 expression, F4/80-positive cells, fibrosis, and EMT compared with that of the wild-type mice. For further clarification of the effects of HO-1 deficiency on TGF-β1–mediated EMT in proximal tubules, in vitro studies were performed to eliminate the confounding effects of infiltrating cells. These in vitro studies, using primary cells derived from HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice, indicated that HO-1–deficient proximal tubular epithelial cells have increased TGF-β1–mediated EMT than wild-type cells.

Taken together, our results suggest that HO-1 has a critical role in the modulation of renal fibrosis, macrophage infiltration, and, more important, the suppression of EMT. Modulation of EMT, a major contributor to tubulointerstitial fibrosis, through the HO-1 pathway may provide a means for novel therapeutic interventions aimed at progressive renal diseases.

CONCISE METHODS

Animals, Surgery, and Tissue Preparation

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Ten HO-1−/− mice (6 to 8 wk of age, C57BL/6xFVB) were used for UUO (n = 7) or sham (n = 3) operation. Twelve age-matched HO-1+/+ littermates were used for comparison. At the age of 6 to 8 wk, HO-1−/− and HO-1+/+ mice have similar phenotypes,59 and renal Fn levels, as measured by Western blot analysis, are the same (unpublished observations).

UUO surgery was performed as described by Pat et al.21 Mice were anesthetized with inhalation of isoflurane (2.5%). In the UUO group, the left ureter was exposed through a mid-abdominal incision and ligated twice, approximately 1 cm below the renal hilum, using a 4-0 silk suture. Sham operation was done in a similar manner, without ureteral ligation. After 7 d, all mice were killed. The time point was chosen on the basis of previous studies demonstrating that at 7 d, cellular recruitment and growth factor–dependent matrix accumulation have begun and HO-1 is induced.20, 21, 60 At the time of killing, both kidneys were removed and cut transversely, and sections were fixed (10% buffered formaldehyde solution) for histopathologic studies or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for Western analysis.

Histologic Examination

The formalin-fixed kidney slices were embedded in paraffin, sectioned (4 μm), and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Masson's trichrome. Hydronephrosis was assessed semiquantitatively by two independent investigators in a blinded manner using photographs of Masson's trichrome–stained kidney sections, at low magnification (×10). A scoring system was used as described by Vora et al.26: 0, normal (finger-in-glove configuration of the papilla and calyx); 1, minimal (a narrow definable fluid-filled calyceal space with normal papillary shape); 2, moderate (obvious calyx dilation with compression of the papilla but with preservation of its conical shape); and 3, marked (unmistakable distension of the calyx, increased overall kidney volume resulting in severe compression of the lateral cortex and distortion of the papilla). Scores were averaged. For analysis of fibrosis, a ×100 light microscopic field covering most of the wedge-shaped area including cortex and partial medulla along the papillary axis was assessed (Figure 2A). The area of fibrosis, stained blue by Masson's trichrome staining, was measured by color image analysis software (Image-Pro Plus, Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD).

Immunohistochemical Studies

For macrophage recruitment, a rat mAb to mouse F4/80 (catalog no. MF48000; Caltag Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) and for α-SMA, a mouse mAb (catalog no. A5228; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used. For HO-1, anti–HO-1 antibody (SPA-895 or SPA-896; Stressgen, Vancouver, BC, Canada) was used. Mouse kidneys were embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm sections were cut and the paraffin was removed with xylene and ethanol and then rinsed in distilled water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation of the sections in 3% H2O2 for 10 min. Immunohistochemical studies were semiquantitatively or quantitatively assessed by two independent investigators in a blinded manner.

For F4/80, the sections were rinsed in distilled water, and then antigen retrieval was performed by incubation of the sections in Trilogy (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA) in 95°C water bath for 25 min. The sections were washed in TBS, blocked by Sniper (catalog no. BS966H; Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) for 15 min, then incubated with F4/80 diluted 1:200 in antibody diluents (catalog no. 00-3218; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were washed in TBS and then were incubated for 30 min with nonbiotinylated rabbit anti-rat secondary antibody diluted 1:200 in TBS. The sections were washed again in TBS, then were treated with Mach2 goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) polymer (catalog no. RALP525L; Biocare Medical) and again washed in TBS, and then exposed to diaminobenzidine (catalog no. DB801L; Biocare Medical). The sections were washed in distilled water, dehydrated with xylene and ethanol, mounted with cytoseal (catalog no. 8312-4; Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) and observed by light microscopy. F4/80-positive cells were counted in five high-powered fields (HPF; ×400) in the cortex of the same wedge-shaped area along the papillary axis as for fibrosis assessment.

For α-SMA, the sections were blocked with 5% goat serum in 0.1% Tween 20/PBS for 1 h followed by incubation with α-SMA antibody (1:500 dilution) in 0.1% Tween 20/PBS overnight at 4°C and washed with 0.1% Tween 20/PBS. The sections were then incubated with goat anti-mouse HRP–conjugated antibody (1:2500 dilution) in 0.1% Tween 20/PBS and washed with 0.1% Tween 20/PBS. For staining, DAB Chromagen Mix (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, and sections were dehydrated as already described and observed by light microscopy.

For TGF-β1, S100A4, lotus lectin, peanut agglutinin, and HO-1 analyses, the following protocol was used. Briefly, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were treated by immersion in Declere (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA) for 20 min. The endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2, and then sections were exposed to normal serum to prevent nonspecific antibody binding. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The sections were then exposed to peroxidase-conjugated ImmPRESS anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min, and VectorVIP substrate was added for signal detection. For double immunohistochemical staining, before the incubation with anti-S100A4 antibody, sections were incubated with biotinylated lotus lectin (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature after blocking of endogenous biotin activity with streptavidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories). Thereafter, sections were treated with VectorSG substrate for signal detection of lotus lectin.

Rabbit anti–TGF-β1 antibody (MBL Int., Woburn, MA) was used for determination of TGF-β1. Immunohistochemical staining of TGF-β1, lotus lectin, and peanut agglutinin (Vector Laboratories) was also performed on serial sections from obstructed kidneys of HO-1−/− mice. VectorSG substrate was used for signal detection of lotus lectin, and DAB (Vector Laboratories) was used for detection of peanut agglutinin. For measurement of the TGF-β1 expression in the renal tubule, five cortical HPF (×400) were analyzed. In each HPF, the total area of 20 tubular cross-sections including proximal and distal tubules was first calculated using the Image-Pro Plus software. Next, the area of TGF-β1–positive staining was determined within the total tubular area. TGF-β1 staining was expressed as a mean ratio of TGF-β1–positive area to total tubular area from five HPF.

For determination of EMT, double immunohistochemical staining was performed using rabbit anti-human S100A4 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) as a mesenchymal cell marker and biotinylated lotus lectin (Vector Laboratories) as a proximal tubule marker. Nine HPF within each cortex were analyzed. In each HPF area, 10 proximal tubules were selected and analyzed for S100A4 as described for TGF-β1.

ELISA for TGF-β1 Levels

Kidney tissue levels of TGF-β1 were determined using the commercial Ready-Set-Go! Human/mouse TGF-β1 sandwich ELISA kit in accordance with the protocol specified by the manufacturer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The samples were acidified to measure total TGF-β1 and are expressed as pg TGF-β1/mg total protein (measured by the BCA assay).

Western Blot Analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously.51 Briefly, harvested kidney tissue slices or cell cultures were lysed in RIPA buffer and electrophoresed in a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a Hybond C Extra membrane. Membranes were incubated with anti-Fn (Sigma), anti–HO-1, anti–α-SMA, anti–claudin-2 (Zymed Laboratories), or anti–E-cadherin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) antibodies, using manufacturer-recommended dilutions, followed by a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (or mouse) IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). HRP activity was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence. The membrane was stripped and probed with anti–β-actin antibody (Sigma) to confirm loading and transfer.

Generation of Proximal Tubule Epithelial Cells from HO-1−/− and HO-1+/+ Mice

Primary proximal tubular epithelial cell cultures were generated from the kidneys of HO-1−/− mice and their wild-type littermates using a previously described procedure with minor modifications.27, 61 Kidney cortices from mice (<6 to 8 wk of age) were dissected from the medulla, sliced, minced, and filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer over a 50-ml conical tube by washing with media (REBM bullet kit; Cambrex BioScience) and using the rubber end of a syringe plunger to manipulate the tissue. The samples were centrifuged (800 rpm for 5 min) to pellet the tubules, washed with 5 to 10 ml of medium, centrifuged, and washed twice more. The final pellet was resuspended in media, and the tubules were placed in a collagen-coated dish and incubated overnight at 37°C, in a humidified incubator with 95% air and 5% CO2. The cellular debris plated on the dish and the medium containing the tubules were collected and centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min. The tubules were resuspended, plated in new collagen-coated culture plates, and incubated without disturbing for 72 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The medium was then changed every 2 to 3 d until confluent. Primary cultures were grown in renal epithelial growth medium (REBM bullet kit) containing 130 mg/dl d-glucose, 0.5% FCS, human EGF, insulin, hydrocortisone, amphotericin B, epinephrine, triiodothyronine, transferrin (REGM Bullet Kit), and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cell lines were checked for expression of γ-glutamyltranspeptidase and alkaline phosphatase, markers for proximal tubule cells,27 using protocols provided by Cambrex.

TGF-β1 Treatment of Primary Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cell Cultures

Confluent cells (with dome formation) were treated with 5 ng/ml recombinant human TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 0 (vehicle for TGF-β1), 24, 48, and 72 h. Cell lysates all were collected at the same time. Immunoblot analysis was performed as described above. Within a given experiment, HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− treated cell lysates were run on the same gel so that the transfer and exposure of the samples would be the same.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Two-tailed t test and repeated measure ANOVA were used for analyses, with statistical significance considered at P < 0.05.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R01 Grants HL061857 and DK59600 to A.A. and DK071875 and American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 0555230B to N.H.-K.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

J.-H.K.'s current address is Department of Pathology, National Health Insurance Corporation Ilsan Hospital, Koyang, Korea.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klahr S, Morrissey J: Obstructive nephropathy and renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F861–F875, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bascands JL, Schanstra JP: Obstructive nephropathy: Insights from genetically engineered animals. Kidney Int 68: 925–937, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang SP, Woolf AS, Quinn F, Winyard PJ: Deregulation of renal transforming growth factor-beta1 after experimental short-term ureteric obstruction in fetal sheep. Am J Pathol 159: 109–117, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Docherty NG, O’Sullivan OE, Healy DA, Murphy M, O’Neill AJ, Fitzpatrick JM, Watson RW: TGF-β1 induced EMT can occur independently of its pro-apoptotic effects and is aided by EGF receptor activation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1202–F1212, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Liu Y: Dissection of key events in tubular epithelial to myofibroblast transition and its implications in renal interstitial fibrosis. Am J Pathol 159: 1465–1475, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay ED: An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat (Basel) 154: 8–20, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada H, Danoff TM, Kalluri R, Neilson EG: Early role of Fsp1 in epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Am J Physiol 273: F563–F574, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeisberg M, Bonner G, Maeshima Y, Colorado P, Muller GA, Strutz F, Kalluri R: Renal fibrosis: Collagen composition and assembly regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation. Am J Pathol 159: 1313–1321, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan JM, Huang XR, Ng YY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Mu W, Atkins RC, Lan HY: Interleukin-1 induces tubular epithelial-myofibroblast transdifferentiation through a transforming growth factor-beta1-dependent mechanism in vitro. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 820–831, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strutz F, Zeisberg M, Ziyadeh FN, Yang CQ, Kalluri R, Muller GA, Neilson EG: Role of basic fibroblast growth factor-2 in epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Kidney Int 61: 1714–1728, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SH, Choi MJ, Song IK, Choi SY, Nam JO, Kim CD, Lee BH, Park RW, Park KM, Kim YJ, Kim IS, Kwon TH, Kim YL: Erythropoietin decreases renal fibrosis in mice with ureteral obstruction: Role of inhibiting TGF-beta-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1497–1507, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traylor A, Hock T, Hill-Kapturczak N: Specificity protein 1 and Smad-dependent regulation of human heme oxygenase-1 gene by transforming growth factor-beta1 in renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F885–F894, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill-Kapturczak N, Truong L, Thamilselvan V, Visner GA, Nick HS, Agarwal A: Smad7-dependent regulation of heme oxygenase-1 by transforming growth factor-beta in human renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 275: 40904–40909, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maines MD: The heme oxygenase system: A regulator of second messenger gases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 37: 517–554, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill-Kapturczak N, Chang SH, Agarwal A: Heme oxygenase and the kidney. DNA Cell Biol 21: 307–321, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morimoto K, Ohta K, Yachie A, Yang Y, Shimizu M, Goto C, Toma T, Kasahara Y, Yokoyama H, Miyata T, Seki H, Koizumi S: Cytoprotective role of heme oxygenase (HO)-1 in human kidney with various renal diseases. Kidney Int 60: 1858–1866, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nath KA: Heme oxygenase-1: A provenance for cytoprotective pathways in the kidney and other tissues. Kidney Int 70: 432–443, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willis D, Moore AR, Frederick R, Willoughby DA: Heme oxygenase: A novel target for the modulation of the inflammatory response. Nat Med 2: 87–90, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones EA, Shahed A, Shoskes DA: Modulation of apoptotic and inflammatory genes by bioflavonoids and angiotensin II inhibition in ureteral obstruction. Urology 56: 346–351, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawada N, Moriyama T, Ando A, Fukunaga M, Miyata T, Kurokawa K, Imai E, Hori M: Increased oxidative stress in mouse kidneys with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int 56: 1004–1013, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pat B, Yang T, Kong C, Watters D, Johnson DW, Gobe G: Activation of ERK in renal fibrosis after unilateral ureteral obstruction: Modulation by antioxidants. Kidney Int 67: 931–943, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JH, Yang JI, Jung MH, Hwa JS, Kang KR, Park DJ, Roh GS, Cho GJ, Choi WS, Chang SH: Heme oxygenase-1 protects rat kidney from ureteral obstruction via an antiapoptotic pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1373–1381, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakder S, Rathi S, Ma XL, Rattan S: Heme oxygenase inhibitor zinc protoporphyrin IX causes an activation of nitric oxide synthase in the rabbit internal anal sphincter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277: 1376–1382, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jozkowicz A, Dulak J: Effects of protoporphyrins on production of nitric oxide and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in vascular smooth muscle cells and macrophages. Acta Biochim Pol 50: 69–79, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff DJ, Naddelman RA, Lubeskie A, Saks DA: Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase isoforms by porphyrins. Arch Biochem Biophys 333: 27–34, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vora JP, Zimsen SM, Houghton DC, Anderson S: Evolution of metabolic and renal changes in the ZDF/Drt-fa rat model of type II diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 113–117, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taub M, Sato G: Growth of functional primary cultures of kidney epithelial cells in defined medium. J Cell Physiol 105: 369–378, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burns WC, Kantharidis P, Thomas MC: The role of tubular epithelial-mesenchymal transition in progressive kidney disease. Cells Tissues Organs 185: 222–231, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoo KH, Thornhill BA, Forbes MS, Coleman CM, Marcinko ES, Liaw L, Chevalier RL: Osteopontin regulates renal apoptosis and interstitial fibrosis in neonatal chronic unilateral ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int 70: 1735–1741, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kida Y, Asahina K, Teraoka H, Gitelman I, Sato T: Twist relates to tubular epithelial-mesenchymal transition and interstitial fibrogenesis in the obstructed kidney. J Histochem Cytochem 55: 661–673, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klahr S: Obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int 54: 286–300, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klahr S, Morrissey J: Obstructive nephropathy and renal fibrosis: The role of bone morphogenic protein-7 and hepatocyte growth factor. Kidney Int Suppl S105–S112, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Diamond JR, Kees-Folts D, Ding G, Frye JE, Restrepo NC: Macrophages, monocyte chemoattractant peptide-1, and TGF-beta 1 in experimental hydronephrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 266: F926–F933, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diamond JR, van Goor H, Ding G, Engelmyer E: Myofibroblasts in experimental hydronephrosis. Am J Pathol 146: 121–129, 1995 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diamond JR: Macrophages and progressive renal disease in experimental hydronephrosis. Am J Kidney Dis 26: 133–140, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diamond JR, Kees-Folts D, Ding G, Frye JE, Restrepo NC: Macrophages, monocyte chemoattractant peptide-1, and TGF-beta 1 in experimental hydronephrosis. Am J Physiol 266: F926–F933, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamate J, Okado A, Kuwamura M, Tsukamoto Y, Ohashi F, Kiso Y, Nakatsuji S, Kotani T, Sakuma S, Lamarre J: Immunohistochemical analysis of macrophages, myofibroblasts, and transforming growth factor-beta localization during rat renal interstitial fibrosis following long-term unilateral ureteral obstruction. Toxicol Pathol 26: 793–801, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogt BA, Shanley TP, Croatt A, Alam J, Johnson KJ, Nath KA: Glomerular inflammation induces resistance to tubular injury in the rat: A novel form of acquired, heme oxygenase-dependent resistance to renal injury. J Clin Invest 98: 2139–2145, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nath KA, Vercellotti GM, Grande JP, Miyoshi H, Paya CV, Manivel JC, Haggard JJ, Croatt AJ, Payne WD, Alam J: Heme protein-induced chronic renal inflammation: Suppressive effect of induced heme oxygenase-1. Kidney Int 59: 106–117, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murali NS, Ackerman AW, Croatt AJ, Cheng J, Grande JP, Sutor SL, Bram RJ, Bren GD, Badley AD, Alam J, Nath KA: Renal upregulation of HO-1 reduces albumin-driven MCP-1 production: Implications for chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F837–F844, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pittock ST, Norby SM, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, Bren GD, Badley AD, Caplice NM, Griffin MD, Nath KA: MCP-1 is up-regulated in unstressed and stressed HO-1 knockout mice: Pathophysiologic correlates. Kidney Int 68: 611–622, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medici D, Hay ED, Goodenough DA: Cooperation between snail and LEF-1 transcription factors is essential for TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Biol Cell 17: 1871–1879, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vongwiwatana A, Tasanarong A, Rayner DC, Melk A, Halloran PF: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition during late deterioration of human kidney transplants: The role of tubular cells in fibrogenesis. Am J Transplant 5: 1367–1374, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donato R: Intracellular and extracellular roles of S100 proteins. Microsc Res Tech 60: 540–551, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG: Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest 110: 341–350, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeisberg M, Hanai J, Sugimoto H, Mammoto T, Charytan D, Strutz F, Kalluri R: BMP-7 counteracts TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat Med 9: 964–968, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sato M, Muragaki Y, Saika S, Roberts AB, Ooshima A: Targeted disruption of TGF-beta1/Smad3 signaling protects against renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Clin Invest 112: 1486–1494, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rhyu DY, Yang Y, Ha H, Lee GT, Song JS, Uh S-t, Lee HB: Role of reactive oxygen species in TGF-β1-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal tubular epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 667–675, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Radisky DC, Kenny PA, Bissell MJ: Fibrosis and cancer: Do myofibroblasts come also from epithelial cells via EMT? J Cell Biochem 101: 830–839, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsui TY, Wu X, Lau CK, Ho DW, Xu T, Siu YT, Fan ST: Prevention of chronic deterioration of heart allograft by recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated heme oxygenase-1 gene transfer. Circulation 107: 2623–2629, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mark A, Hock T, Kapturczak MH, Agarwal A, Hill-Kapturczak N: Induction of heme oxygenase-1 modulates the profibrotic effects of transforming growth factor-beta in human renal tubular epithelial cells. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 51: 357–362, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujita T, Toda K, Karimova A, Yan SF, Naka Y, Yet SF, Pinsky DJ: Paradoxical rescue from ischemic lung injury by inhaled carbon monoxide driven by derepression of fibrinolysis. Nat Med 7: 598–604, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gong LM, Du JB, Shi L, Shi Y, Tang CS: Effects of endogenous carbon monoxide on collagen synthesis in pulmonary artery in rats under hypoxia. Life Sci 74: 1225–1241, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morse D, Choi AM: Heme oxygenase-1: The “emerging molecule” has arrived. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 27: 8–16, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li L, Grenard P, Nhieu JT, Julien B, Mallat A, Habib A, Lotersztajn S: Heme oxygenase-1 is an antifibrogenic protein in human hepatic myofibroblasts. Gastroenterology 125: 460–469, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang HD, Yamaya M, Okinaga S, Jia YX, Kamanaka M, Takahashi H, Guo LY, Ohrui T, Sasaki H: Bilirubin ameliorates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 406–411, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou Z, Song R, Fattman CL, Greenhill S, Alber S, Oury TD, Choi AM, Morse D: Carbon monoxide suppresses bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Pathol 166: 27–37, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abdel-Aziz MT, el-Asmar MF, el-Miligy D, Atta H, Shaker O, Ghattas MH, Hosni H, Kamal N: Retrovirus-mediated human heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) gene transfer into rat endothelial cells: The effect of HO-1 inducers on the expression of cytokines. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 35: 324–332, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kapturczak MH, Wasserfall C, Brusko T, Campbell-Thompson M, Ellis TM, Atkinson MA, Agarwal A: Heme oxygenase-1 modulates early inflammatory responses: Evidence from the heme oxygenase-1-deficient mouse. Am J Pathol 165: 1045–1053, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matsuo S, Lopez-Guisa JM, Cai X, Okamura DM, Alpers CE, Bumgarner RE, Peters MA, Zhang G, Eddy AA: Multifunctionality of PAI-1 in fibrogenesis: Evidence from obstructive nephropathy in PAI-1-overexpressing mice. Kidney Int 67: 2221–2238, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen S, Hoffman BB, Lee JS, Kasama Y, Jim B, Kopp JB, Ziyadeh FN: Cultured tubule cells from TGF-beta1 null mice exhibit impaired hypertrophy and Fn expression in high glucose. Kidney Int 65: 1191–1204, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]