Abstract

Immigrant community institutions are strategically positioned to facilitate or impede public health efforts in their neighborhoods and communities because of their influence over discourse regarding values and tradition. Their authority may be particularly relevant when stigmatized or sensitive issues, such as HIV or reproductive health, are addressed. Using qualitative and quantitative methods to analyze data collected from 22 Chinese and South Asian immigrant institutions in New York City, we examine attitudes about HIV, social change and tradition to delineate the different structural roles that Asian immigrant community institutions play in relation to the preservation of traditional values and culture in their neighborhoods and communities. Implications are explored for working with immigrant community institutions to conduct HIV-related work and other stigmatized public health initiatives in immigrant neighborhoods.

Keywords: immigrants, institutions, place, HIV, Asians, stigma

Introduction

It has long been recognized that immigrants commonly form voluntary associations or community institutions soon after their arrival (Moya, 2005). Faced with language and cultural barriers, discrimination, disrupted familial and social arrangements, and economic hardship, immigrants turn to their community institutions for practical, social and emotional support (Loue et al., 1999; Basch et al., 1994; Zhou, 1992; Guest, 2003). In this way, immigrant community institutions play an important role in creating places where immigrants can find resources to help them adjust to life in their new country and to reproduce many aspects of the culture and lifestyle they experienced in their countries of origin. These places, often immigrant enclaves in urban areas, serve not only immigrant residents in the immediate area but also those in outlying suburbs, who come to the immigrant neighborhood for ethnic resources, including places to worship, shop and participate in cultural activities (Khandelwal, 2002).

Because of their wide reach, respected role, and influence over discourse regarding morals, values and tradition, many immigrant community institutions are strategically positioned to facilitate or impede public health efforts among their constituents, especially in areas that may be stigmatized or sensitive, such as HIV or reproductive health. Our previous research, in which we developed a comprehensive database on Chinese and South Asian immigrant community institutions in New York City (NYC), suggests that these institutions are strategically positioned not only socially, but also in their physical location. Of the 529 institutions that we were able to identify and map, most were located in census tracts with high concentrations of Asian immigrants or in census tracts adjacent to those [placholder for citation of authors’ paper]. Recognizing the potential influence and reach of immigrant and ethnic community institutions, researchers and policy makers have called for their inclusion in public health initiatives. Achieving inclusion and cultural relevance have been key objectives of health-related community-based participatory research (Cornwall and Jewkes, 1995; Israel et al., 1998) and of standards for cultural competence and linguistic appropriateness in health care settings (Office of Minority Health, 2001). Involving key community institutions capitalizes on their influence in the community and can mitigate barriers they might pose for public health efforts.

While there has been a substantial amount of research on health interventions implemented by service-based or client-based community organizations (e.g., nonprofit social service organizations, etc.) in immigrant communities, there has been little research on the role of membership-based organizations (e.g., religious organizations, professional associations, etc.). While client-based social service organizations have an impact on community social norms, their direct reach may not extend far beyond their clients and the clients’ families. Educational or awareness-raising campaigns led by social service agencies may be seen as efforts by relative “outsiders” or as efforts by people with a particular agenda. Membership-based organizations, in contrast, may be more likely to have “insider” status and to have a broader community reach. Our research, for example, indicates that almost 80% of Chinese and South Asian community immigrant institutions in New York City are membership-based institutions. The largest ones fulfill diverse community-wide functions, including the organization of large, highly visible festivals and parades. One such organization in NYC’s Chinatown has been commonly referred to as the “Mayor” of Chinatown.

Neglect of membership-based organizations has meant that the role of community institutions in facilitating or impeding public health efforts through their impact on community norms and values, especially in areas that are stigmatized or sensitive, has been under-studied, although there are some notable exceptions (see for example Cohen [1999] and Agadjanian [2005]). Even fewer studies of this type have looked at community institutions in immigrant communities in the US. An exception is a study by Takahashi (1997), which explored community social norms through interviews with informal opinion leaders, many of whom were “highly respected religious or civic leaders” (p, 191).

To address these research gaps, our study examines both client- and membership-based Asian immigrant community institutions in New York City (NYC) and the various roles they play in upholding or challenging traditions and taboos that may impede open discussion about HIV and contribute to HIV stigma in the neighborhoods they serve. We conclude by exploring implications for the potential roles that different types of immigrant institutions can play in HIV-related work and other public health efforts related to stigmatized issues or health conditions. Because community institutions may have similar functional roles across a range of immigrant communities and other communities that are marginalized for reasons of race, religion or class, the lessons learned from this analysis may have applications in other immigrant and non-immigrant neighborhoods and populations.

Before presenting the study’s methods and data, we further describe the relationships among community institutions, place and HIV in immigrant communities to provide a theoretical foundation for our analysis.

Shaping Places for Support or for Exploitation

Understanding how immigrant places are shaped, and the social and physical landscape that immigrants navigate within their own communities, helps to pinpoint some fundamental barriers to immigrant community institution involvement in HIV-related and other similarly stigmatized or taboo-confronting efforts. We deliberately invoke the term “landscape” here to suggest that we are interested in studying immigrant places not just to understand the details of specific localities but also more generally to understand how immigrant places are products “of the intersection of the cultural and politico-economic” (Kearns and Moon, 2002, p, 610). Within immigrant communities, this intersection is partly, perhaps even largely, mediated through immigrant community institutions, both as actors and more passively as gathering places. Similar to what Sibley (1995) describes in Geographies of Exclusion, we are interested in “…foreground[ing] the more opaque instances of exclusion, opaque, that is, from a mainstream or majority perspective, the ones which do not make the news or are taken for granted as part of the routine of daily life. These exclusionary practices are important because they are less noticed and so the ways in which control is exercised in society are concealed” (p, ix). In studying responses to HIV within immigrant communities, we are attempting to understand both the subtle and more openly expressed forms of marginalization of sub-groups within immigrant communities that are already marginalized.

Much of the immigration literature paints immigrant communities as supportive places where immigrants can be buffered from discrimination in the larger society and gain an economic foothold and aim for the mobility of their children if not for themselves (see Zhou [1992], for example, on Chinatown). Others see the immigrant community as designed to solidify the power of some sub-groups within the community over other sub-groups in an exploitative ethnic economy that benefits immigrant business owners but not their co-ethnic immigrant workers (see Kwong [1987], for example). Both functions of the immigrant community respond to and rely on the physical or social separation of immigrants from the larger society.

According to Kwong (1987), physical and social isolation were crucial elements in forming a system of co-ethnic exploitation in New York City’s Chinatown that still operates today. This system began with members of ethnic and village-based associations in Chinatown who owned shops or other businesses and who became association leaders because of their ability to provide jobs and other favors. Kwong contends that, in order to maintain social control today, the Chintaown elite uses its leadership in important community institutions to perpetuate notions of ethnic solidarity, such as “‘we are all Chinese and we should not fight among ourselves,’” that tend to minimize the significance of class differences and overlook the needs of Chinatown’s working people (Kwong, 1987, p, 94). The well-defined physical community boundaries supported by the hegemonic discourse within Chinatown of a static, nationalistic notion of Chineseness, makes social control possible, Kwong argues, which facilitates the exploitation of Chinese workers by other Chinese who own restaurants, garment factories and other businesses.1

Although in a globalized, transnational age, the bounded space of any particular immigrant community is decreasingly defined by a single physical place, it is still intensely “local.” This is illustrated by Sassen’s (1995) characterization of immigrant “local labor markets,” in which job networks that span two or more countries often focus on specific locations, for example, linking a small town in Southern China to a specific garment factory in New York City’s Chinatown. These local labor market spaces gain solidity and order from the “weight of social ties that bind people into relations of trust and mutual obligation” (Sassen, 1995, p, 67) that are facilitated in part by community institutions.

The maintenance of power differentials within immigrant communities can also be viewed through a feminist lens, focusing on power imbalances fundamentally based on gender even if they have economic implications. Abraham’s (2000) study of domestic violence in South Asian immigrant communities in the US specifically pointed to the role of key community institutions in supporting traditional gender role norms. Abraham contends that religious institutions’ role as protectors of the ethnic community inhibits their response to instances of domestic violence in the community. According to Abraham, “… religious institutions are not places of prayer alone but, more important, are the arena for the construction and maintenance of values, beliefs, and customs of the immigrant community. … These centers of worship become the caretakers of tradition in an alien, modernistic society. The moral solidarity of the collective becomes of vital importance” (p, 120). In her view, religious institutions’ failure to support or defend women who are targets of domestic violence is “largely a function of perceiving religion as the last bastion for the collective maintenance of traditional South Asian values” (p, 121).

In thinking about the roles of community institutions in HIV prevention and support activities, it is important to understand not only the dominant community institutions, but also the role of progressive or marginalized community institutions that might challenge prevailing social and economic structures. These challenges are inevitable because of both internal and external changes (Kibria, 1993; Gans, 1992; Ablemann and Lie, 1995; Basch, 1994; Kwong, 1987; Kasinitz, 1992; Portes and Stepick, 1993). For example, children of immigrants who have greater social and economic options may move more freely outside of their ethnic “places” and bring new ideas back in. Evolving norms and opportunities in the larger society and in the group’s country of origin also affect the norms of Asian communities in NYC. Competing community institutions or sub-groups – especially those whose members suffer disproportionately under prevailing social and economic systems –may embrace these changes, thereby challenging the legitimacy of the status quo.

Immigrant Community Institutions, Social Norms and HIV

Leaders and members of community institutions may not explicitly link the enforcement of social norms to the support of a particular social, gender, or economic structure; rather, the discourse around social norms revolves around protecting cherished and “unchanging” traditions of a definable ethnic group or to moral positions (Ong, 1993; Ang, 1993; Kwong, 1987). For example, the Korean church has assumed the “unintended function” of supporting Korean immigrant small-business success in the economic realm by reinforcing “members’ values of self-control and hard work by constantly emphasizing self-abnegation, endurance, hardship, and frugality” in religious teachings (Kim, 1987, p, 235). The linking of social norms to moral or religious positions, rather than to situational and changing gender roles and economic circumstances, creates an environment where the enforcement of social norms is seen as an important goal in itself. The functional, worldly role of social norms in maintaining a system of power relations need never be acknowledged.

In her classic work Purity and Danger, anthropologist Mary Douglas (2002) suggests that cultural norms and taboos are ever-changing, yet are often promoted as static and primordial by members of that culture in order to support a certain community structure. She writes that “taboo protects the local consensus on how the world is organized” (p, xi) and that challenges to this consensus are inhibited by promoting fear of harm that may result from not adhering to norms. Change in this situation may come slowly and with difficulty since consistency protects groups that enjoy disproportionate benefits. According to Kwong (1987), Chinatown elites are so invested in the current system that some, in the extreme, have resorted to violence through organized crime to discipline those who openly challenge the ideals that support it.

Because addressing HIV constructively would mean re-evaluating core social norms around gender and sexuality, community institutions have been reluctant to become involved in HIV prevention and support, despite their potential to play a key role. If those core social norms are perceived by community members as crucial for maintaining community structures, engaging HIV constructively may be seen as a threat to the very survival of the community. Even members of sub-groups that might gain power from a change in social structure might be reluctant to pursue it in order to preserve order. Kibria’s (1993) research on Vietnamese immigrants in Philadelphia, for instance, showed how Vietnamese women had to carefully balance two roles in their new environment: their increasingly important position as the family’s primary interface with mainstream society and their subordinate role in relation to their husbands within the traditional family structure. She found that the women were reluctant to elevate their status in the family to correspond to their greater access to resources, relative to that of men, because of their orientation to collectivism and cooperation, which they felt were threatened by change.

Engaging HIV can also be threatening because it confronts fundamental norms related to discouraging difference itself. A greater acceptance of heterogeneity in the ethnic group allows for more “porous ethnic boundaries and greater variation in identities within a given ethnic group” (Sanders and Nee, 1996, p, 233), which makes it more difficult to enforce the ethnic solidarity that is crucial to the success of many immigrant social and economic structures (Light et al., 1995; Nee et al., 1994). In the case of HIV, because “difference” relates to disease, the threat to the community may be perceived as even more alarming. As Sibley (1995) writes, “disease in general threatens the boundaries of personal, local and national space, it engenders a fear of dissolution…; …thus the ‘diseased other’ has an important role in defining normality and stability” (p, 24).

Of course, leaders and members of immigrant community institutions are quite unlikely to articulate their reluctance to become involved in HIV as related to preventing community dissolution and preserving economic systems. Rather, they are more likely to articulate their reluctance as being rooted in fear and stigma or the inappropriateness of the topic. Numerous studies have documented fear and stigma associated with HIV, and some have indicated that HIV-related stigma may be particularly intense in Asian immigrant communities (Yoshikawa et al., 2001; Yoshioka and Schustack, 2001; Eckholdt et al., 1997; Sy et al., 1998; Chin and Kroesen, 1999; Kang et al., 2003). The fear and stigma associated with HIV are related not only to the fear of being infected, but also to HIV’s association with stigmatized behaviors, such as drug use, non-marital sex, and homosexuality, both in the larger society (Sibley, 1995; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2002) and in Asian immigrant communities (Takahashi, 1997; Choi et al., 1995).

The impact of stigma on the lives of Asian immigrants infected or affected by HIV should not be under-estimated. This stigmatization has numerous consequences, including delays in HIV testing and care (Bhattacharya, 2004; Eckholdt et al., 1997), particularly among undocumented (Kang et al., 2003) and other foreign-born (Hu et al., 1995) APIs. Stigmatization results in marginalization and isolation of individuals living with HIV, poor mental health [placeholder for authors’ paper citation #2], and lost opportunities for education and discussion regarding prevention and care (Kang et al., 2003). Stigma can even affect the physical location and appearance of HIV-related programs. For example, one AIDS-specific community-based organization in New York City whose primary target population is Asian immigrants has avoided store-front locations to promote the privacy of clients. This same organization underwent a contentious debate with its HIV-positive Asian immigrant client population regarding having the word “AIDS,” which is part of its name, on the second-floor door. The conflict escalated to the point where a client scratched the word “AIDS” from the professionally-lettered sign on the door.2

The discussion above suggests the potentially powerful role of immigrant community institutions, and the norms and values they promote, in facilitating or impeding public health initiatives related to taboo or stigmatized issues. It also suggests that different types of immigrant community institutions are likely to take different postures toward the preservation of tradition, taboos and prevailing social norms. In this analysis, we begin to identify and analyze these postures by comparing various Asian immigrant community institutions in terms of the HIV-related attitudes of their members and leaders, using the framework outlined in the previous discussion as a guide for our analysis. Because HIV is highly stigmatized in Asian immigrant communities (Kang et al., 2003) [placeholder for authors’ paper citation #2]), focusing on institutional differences in HIV-related attitudes can bring into sharp relief the different types of roles that immigrant institutions might play in relation to taboo and tradition. While some institutions may want to challenge tradition in their communities, other institutions may favor the preservation of tradition and negative consequences for violating traditional taboos, even as they choose, consciously or unconsciously, which traditions to preserve in adjusting to the host country.

Methods

Data for this article come from an NIH-funded study on the potential role of Asian immigrant community institutions in HIV-related prevention and care. We focused on Chinese and South Asian communities, the two largest Asian populations in NYC.3 China and parts of South Asia have some of the most alarming emergent HIV epidemics globally. Because a detailed description of the study’s recruitment approach, selection criteria, instrument development, and translation and back-translation of instruments have been published elsewhere ([placeholder for authors’ paper citation]), we provide only a summary of those areas in this paper.

Procedures

Recruitment of Institutions

Using Internet listings and ethnic service directories, we generated a comprehensive database of 213 South Asian and 316 Chinese community-based immigrant institutions in NYC. These institutions were classified into ten categories according to their primary purpose. To reduce bias, a stratified random sampling approach was used to select institutions from each of the ten categories for each of the two population groups, resulting in 22 institutions (10 Chinese and 12 South Asian) selected for in-depth study.

Recruitment of Individual Participants within Institutions

Within each of the 22 institutions, two to five persons, recruited with assistance from the institutions’ leaders or more active members, were interviewed between 2003 and 2006. Although this selection process created a bias toward institution leaders and more active members, this was not considered problematic since such individuals are most likely to have the greatest understanding of and impact on their institutions’ stance on important issues. Within these selection constraints, we sought to obtain diversity in participants’ gender, age, and institutional role.

Interview Protocol

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted by two multi-lingual interviewers. The 90-minute interviews were followed by a structured 18-item knowledge and attitudes questionnaire, which was developed for this study to detect variation in a population that was expected to have a low HIV knowledge level. Qualitative interview questions covered organizational characteristics and reputation; participant’s level of involvement in the organization; attitudes and beliefs about social issues, such as gender roles; HIV-related attitudes; barriers to and facilitators of the organization’s involvement in HIV-related activities; and participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. The study was approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board.

All of the South Asian institution interviews were conducted in English, except one in Urdu and one in Tamil. Interviews with the Chinese institutions were conducted primarily in Mandarin; some were conducted in English and Cantonese. Because of the large number of Chinese-speaking participants, both the in-depth interview guide and the HIV knowledge and attitudes questionnaire were translated into Chinese.

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 provides a description of the 10 organization types and the number of organizations and interviews within each type, by ethnicity. As the study was intended to be exploratory, we opted for a small number of organizations within each organization type in order to cover all of the main categories. Except for religious institutions, we aimed for one institution of each organization type per ethnicity, although in some cases, no appropriate organization could be identified (e.g., we were unable to identify a South Asian arts organization comparable to the Chinese one). For institutions that had better coverage in the literature (e.g., healthcare agencies), we opted for fewer interviews. Since religious institutions constituted the largest group of institutions (accounting for 42% [n=132] of Chinese institutions and 47% [n=100] of South Asian institutions in our database), we included two religious institutions per ethnic group, thereby covering each ethnic group’s two major religions (assessed in terms of number of organizations and members, as indicated by our database of organizations).

Table 1.

Number of Organizations and Interviews by Organization Type and Ethnicity

| Number of Organizations | Number of Interviews | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | S. Asian | Chinese | S. Asian | |

|

Arts Organizations

Promote both contemporary and traditional artists working in a variety of forms through organizing gallery shows and performances. |

1 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

|

Business Associations

Provide networking and community service opportunities for individuals in small businesses or corporate business environments. These associations often act as spokespersons for the ethnic community in the larger society. |

1 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

|

Charitable Organizations

Raise funds primarily for anti-poverty and education projects in the country of origin. |

0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

|

Healthcare Agencies

Community clinics based in hospitals and health care centers targeting the ethnic community specifically. |

1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

|

Media Organizations

Prominent ethnic newspapers (one daily, one weekly) with wide circulation in the community. |

1 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

|

Professional Associations

Physician associations catering to the ethnic group. |

1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

|

Religious Institutions

One Chinese Buddhist temple, one Chinese Christian church, one South Asian Hindu temple, one South Asian mosque. |

2 | 2 | 10 | 11 |

|

Sub-Ethnic/Clan Associations

Associations for individuals from the same town, state, province, or with the same language, dialect or surname. These organizations serve a social function and also aim to preserve the sub-ethnic group’s language and culture. |

1 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

|

Umbrella Organizations

Federations of and spokespersons for local ethnic organizations. |

1 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

|

Workers’ Rights Organizations

Advocate for workers’ rights in blue collar industries where the ethnic group is highly represented. |

1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 10 | 12 | 37 | 42 |

The organization type labels in Table 1 are intended to denote the general conceptual categories that emerged from the database and which were also used for stratified sampling. The descriptions following each conceptual label provide information on the specific organizations in the study. Where possible, selected institutions within each organization type were limited to a specific sub-type of organization so that it would be possible to compare similar organizations across ethnic groups. For example, the professional associations included in the study were limited to physicians’ associations, one South Asian and one Chinese.

Table 2 shows that there was a slight overrepresentation of male (58%) and South Asian (53%) participants. Although most participants (96%) were born outside of the US, many had lived here for some time (mean years in US = 21.7). A fairly substantial portion (20%) worked in healthcare or social services, where they may have had more encounters with HIV information and HIV-positive individuals.

TABLE 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

| Percentages and Means (n = 79) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 58% |

| Female | 42% | |

| Ethnicity/Nationality | Chinese | 47% |

| South Asian | 53% | |

| Primary Language | Asian Language | 68% |

| English | 32% | |

| Country of Birth | Not in US | 96% |

| US | 4% | |

| Occupation | Not in Healthcare/Social Services | 80% |

| In Healthcare/Social Services | 20% | |

| Mean Age (SD) | 47.8 (13.0) | |

| Mean Years in the US (SD) | 21.7 (12.6) |

Data Analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative data from this mixed methods study were used in the analysis, providing a form of data triangulation in an iterative process. Previous qualitative analyses ([placeholder for authors’ paper citation]) informed the quantitative modeling reported here, which in turn informed additional qualitative analyses. Using both forms of data was especially critical in this study because of the relatively small sample size.

Quantitative Analysis

Using SAS, descriptive, bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted. Analyses focused on the association between organization type and HIV attitudes, with the aim of suggesting, in conjunction with the qualitative data, the various roles that different organization types might play in maintaining and challenging traditions and taboos in communities, especially those traditions and taboos that might foster or counteract HIV stigma and discussion of HIV. To accommodate both continuous and categorical explanatory variables and to correct for heteroskedasticity, PROC GLIMMIX in SAS was used for bivariate and multivariate regression analyses. A variable that identified the specific organization of the respondent (OrgID) was included in each model to correct for intra-organizational correlation. The dependent and explanatory/control variables used are described below.

Dependent variable

The score from an HIV-related attitudes index, constructed from four relevant items in the structured questionnaire, was used as the dependent variable. The index captures a range of distinct attitudinal dimensions relevant to this inquiry, including attitudes related to personal responsibility, morality, community responsibility, and compassion for and social acceptance of people living with HIV. The four items were: (a) “Most people with AIDS deserve to get it because of their lifestyle;” (b) “It’s important to be able to talk about AIDS in the community;” (c) “If my friend had AIDS, I would try to help him or her;” and (d) “People with AIDS should limit their contact with family and community members.” Participants indicated their agreement with each of the four items using a 5-point Likert scale. Values were recoded so that a higher value corresponded to a more supportive and less judgmental view. The responses to the items constituting this multi-dimensional index were then summed to create the HIV-related attitudes score, which was converted to a 0 to 100 scale for ease of interpretation.

Explanatory/Control variables

Organization type was the primary explanatory variable of interest. Based on their organizational affiliation, participants were assigned to one of the 10 organization type categories shown in Table 1. Several other variables were included to control for individual-level demographic factors, and in effect isolate what might be closer to true organizational differences. These control variables include: ethnicity (Chinese or South Asian); gender (female or male); age; years in the US (there were 3 US-born persons in the sample for whom years in the US was equal to their age); primary language (English or not English); and occupation (whether or not the person was working in health care or social services, as individuals in these professions tended to have more encounters with HIV-positive individuals and HIV information, according to the qualitative interviews). Finally, HIV knowledge (the number of items answered correctly of nine true-false HIV knowledge items) was also included as a control variable.

Qualitative Analysis

Codebook development and coding procedures were based on techniques described by MacQueen (1998) and Corbin (1986). A preliminary codebook was developed after careful review of four interview transcripts. Subsequently, five members of the research team independently coded the same two interviews and then met to discuss the coding process and finalize the codebook. All interview transcripts were then coded either in full or selectively for the themes relevant to the analysis presented here (e.g., HIV-related attitudes and reasons for favoring or disfavoring organizational involvement in HIV-related activities). Additional codes that emerged through the coding process were added to the codebook and then applied to interview transcripts that had already been coded. Research team members also prepared interview summaries using a standardized format, met to discuss coding disagreements, and drafted analytic memos throughout the coding process.

Results and Discussion

HIV-Related Attitudes among Organization Leaders and Members: Quantitative Analysis Results

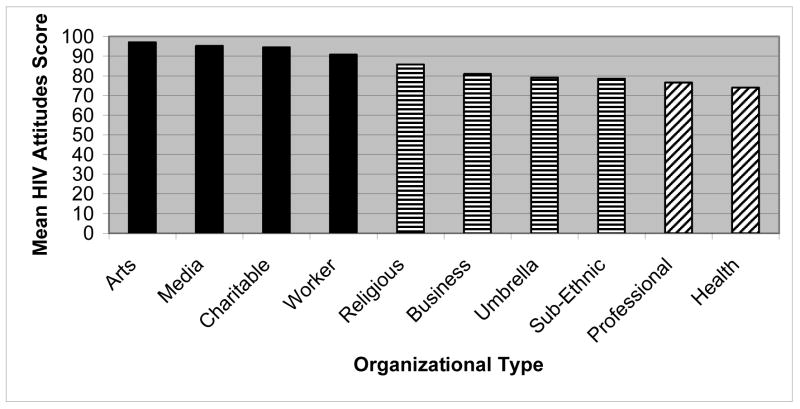

Of the 79 participants, six were excluded because of missing data, yielding an analytic sample of 73. Among these 73 participants, the mean HIV knowledge score was 5.7 (SD = 2.0) out of a maximum score of nine. The overall mean score on the HIV attitudes index (range of 0 to 100) was 80.1 (SD = 16.6), with higher scores indicating more supportive, less judgmental HIV attitudes. First, to examine HIV attitudes means by organization type without controlling for demographic factors, a bivariate model was used with the HIV attitudes score as the dependent variable and organization type as the independent variable, with OrgID introduced as noted above to correct for intra-organizational correlation. Through this procedure, least squares means were produced for each organization type, allowing us to rank the ten types from highest to lowest HIV attitudes scores (most supportive attitudes to least supportive): the charitable organization type had the highest mean score followed by the media, workers’ rights, healthcare, professional, arts, religious, umbrella, sub-ethnic and business organization types. Further bivariate analysis of HIV-related attitudes (details of analysis not included here) suggested that the ten organization types could be divided into two groups, a higher-scoring group and a lower-scoring groups, with the divide occurring between the arts and the religious organization types.

We then ran a multivariate multi-level model using the variables outlined in the methods section to control for clustering of responses within organizations and for individual-level demographic and other characteristics, in order to isolate the association between organization type and HIV-related attitudes, or in other words, to isolate organizational differences unrelated to the demographic composition of the members and leaders.4 The multivariate analysis showed that our explanatory variable of primary interest, organization type, was a significant predictor of HIV attitudes, even after accounting for differences in HIV attitudes attributed to individual-level factors (ethnicity, gender, occupation, age, years in the US, primary language and HIV knowledge). Because organization type is a categorical variable, PROC GLIMMIX creates a coefficient for each category using one category as a contrast for calculating a t-value and its significance level. The coefficient for a category represents the category’s mean deviation on the HIV attitudes index from the adjusted mean for the category designated as the contrast group. The umbrella organization type was selected as the contrast group (M[adjusted] = 79.1) as it was considered the least specialized organization type and therefore the most suitable for comparison. Given the rankings in the bivariate analysis, it was not surprising that the coefficients for the arts (B=17.92, t[45]=4.72, p<0.0001), media (B=16.08, t[45]=5.30, p<0.0001), charitable (B=15.47, t[45]=3.00, p=.0043), and workers’ rights (B=11.66, t[45]=5.25, p<0.0001) organization types were positive and statistically significant when using the umbrella organization type as the contrast category, indicating that being from these organizations is related to more supportive HIV attitudes (i.e., higher scores). However, the professional association (B= −2.53) and healthcare (B= −5.14) organization types, whose HIV attitude means were in the top half in bivariate analysis, had coefficients that are negative and not statistically significant in the multivariate model (p’s > .60), indicating that they join the lower-scoring category after controlling for demographic characteristics and HIV knowledge.5 The religious (B=6.64), business association (B=1.84), and sub-ethnic (B= −0.58) organization types also have coefficients that are not statistically significant, keeping them in the lower-scoring category.

Using the least squares means for each organization type from the multivariate analysis, Figure 1 shows the three different categories of organization types that emerge from examining the bivariate and multivariate analyses together. Moving from left to right in Figure 1, organization types with solid dark bars (arts, media, charitable, workers’ rights organization types) scored notably higher on the HIV attitudes index in bivariate analysis and remain in the higher-scoring category in the multivariate model, which controlled for differences in demographic characteristics and HIV knowledge among study participants. Organization types with the diagonal stripes (professional and health organization types) scored notably higher on the HIV attitudes index in bivariate analysis but join the low-scoring group in the multivariate analysis. Organization types with horizontal stripes (religious, business, umbrella, and sub-ethnic organization types) scored low on the HIV attitudes index in bivariate analysis and are still low-scorers in the multivariate model. Based on their HIV-related attitudes scores, one might interpret these three groupings as moving from most progressive on HIV issues to most conservative, an interpretation that will be explored further below using the qualitative data.

Figure 1.

Multivariate Analysis: HIV-Related Attitudes Score Least Squares Means by Organization Type

Paradigm Shifters, Professionals and Community Sentinels: Qualitative Analysis Results and Discussion

The qualitative data were examined using the three groupings of organization types suggested by the quantitative analysis (see Figure 1). Because the qualitative analysis presented here was intended to aid in interpreting, corroborating and extending the quantitative results, the analysis focused specifically on study participants’ perceptions regarding their own or their organizations’ roles in upholding or questioning community values and tradition, and particularly how involvement in HIV-related activities might be congruent with or conflict with these roles.

Drawing on the conceptual framework presented at the beginning of this article, we hypothesize that the differences in HIV-related attitudes found among the three groupings of organization types are related to their structural roles in maintaining or challenging traditional social norms and taboos in the immigrant neighborhood and the larger immigrant community, where tradition, culture and values are continually contested and renegotiated. As will be illustrated in the discussion below, participants’ own understanding of their organizations’ roles in the community, as reflected in the qualitative data, support the validity of the quantitative distinctions between the three categories, while also revealing nuances that point toward strategies for increasing these organizations’ involvement in HIV-related activities. With the understanding that immigrant community institutions are neither simple nor monolithic and with the intention to construct analytic categories that might provide insights into working with these organizations on HIV and other sensitive public health issues, we drew on the quantitative and qualitative analyses to craft preliminary labels for the three groups of organization types: “Paradigm Shifters,” “Professionals,” and “Community Sentinels.” Not surprisingly the “Paradigm Shifters” are the youngest organizations (Mean date of establishment=1978),6 the “Professionals” are older (M=1982), and the “Community Sentinels” are oldest on average (M=1967). These three categories are further explored below.

The Paradigm Shifters

The qualitative analysis suggests that the “Paradigm Shifters” – the arts, media, charitable, and workers’ rights organizations in the study – seek to shift worldview paradigms of community members and move them out of their complacency, either as ends in themselves (as in the case of the media and arts organizations) or as means to other objectives, such as building community support for fair treatment of workers (workers’ rights organizations) or convincing community members to donate money to support work in their country of origin (the charitable organization). All of the “Paradigm Shifter” organizations tended to be more progressive in their views on issues of social justice. They appear to have the potential to be natural collaborators on HIV/AIDS initiatives and outspoken advocates because of their experiences challenging the status quo.

Consistent with the more progressive HIV-related attitudes found among these organizations in the quantitative analysis, the qualitative analysis showed that participants from all of these organizations described organizational activities that in some way challenged tradition, encouraged social change, or broached taboo topics. Of the four organization types within this category, the arts organization had the most direct engagement with HIV. The director of the arts organization described his AIDS-related work as including singing Chinese opera for people with AIDS in NYC hospitals and donating the proceeds from the sale of his CD to an AIDS foundation. Although the arts organization promotes traditional Chinese music and dance through performances and workshops, which suggests that it would be likely to espouse traditional attitudes, it also promotes contemporary Asian American artists by creating venues for them to display or perform their work.

The frequent role of creative artists as social observers and critics (David and McCaughan, 2006) may help to explain the arts organization’s supportive HIV-related attitudes. More supportive attitudes may also be the result of a more visible presence of homosexuality in the art world (Whitam and Dizon, 1979), which may increase the likelihood of encountering or hearing about HIV because of the relatively high HIV prevalence among gay men in the US, both Asian and non-Asian (Zaidi et al., 2005; MMWR, 2005). This may desensitize organization members to certain taboos and promote proactive responses.

In the media organizations – which produce newspapers that are widely read by the mainstream of the respective ethnic communities they target – a “Paradigm Shifter” attitude was expressed by several participants who saw themselves as upholding journalistic traditions of raising awareness about issues that are poorly understood, especially those affecting marginalized groups. One reporter mentioned that his newspaper had “done a lot of reporting on gay subjects … and gay organizations. … A lot. In a very supportive way.” He further explained that he was finishing an article “on a gay, lesbian, transgender coalition that they say is the first in history to have South Asians, Asian Americans and Caucasians.” In many mainstream American contexts, particularly in New York City, these stories might not be considered radical, but they do push boundaries when they appear in newspapers that Asian immigrants read largely to remain current with events in the ethnic community and in their home countries.

In the charitable organization, which focuses on seeking donations from South Asian Indians in the US to support educational and social service programs in India, participants saw themselves as attempting to move community members out of complacency to address fundamental questions of equity. For example, a study participant from the charitable organization envisioned “a society where we can actually help the homeless or help people who need it” and felt that her organization “encourages people to give back to their community, to do things that … they’re not expected to do … It encourages people to think about problems facing the community and somehow attempt to solve them.” But sometimes she felt isolated by the level of complacency among others in her community: “I’m like the Lone Ranger out there doing this stuff. [People] … will … once in a while ask, well, how’s [your organization] going? Okay. Great. And that’s it.” She explained that other young professional South Asians she knows are more interested in their careers and material comfort than in addressing poverty in India. By juxtaposing their lack of interest in her work with her vision for a more equitable, compassionate society, she evokes an iconic image of a paradigm shifter: an innovator with important but generally unpopular ideas.

The Professionals

The “Professionals” category is made up of the healthcare and professional association organization types, which include a community health center targeting the Chinese community, a community health clinic targeting South Asians, and two ethnic physicians associations, one serving Chinese physicians and the other Indian physicians. The fact that all of the participants in this category are health care professionals makes the quantitative findings more surprising since we might expect that they would have the most supportive HIV attitudes. While they had relatively high scores on the HIV attitudes index in the bivariate analysis, they had negative (but not statistically significant) coefficients in the multivariate model, making the Professionals the most paradoxical group.

This paradox might be partly understood by examining the functional role of healthcare professionals, even those based in community-oriented health centers aimed toward remedying healthcare barriers and inequities experienced by a linguistically isolated ethnic minority. Generally, their functional role is to provide treatment and care without judgment. Study participants working in both private practices and community health centers characterized themselves as relatively neutral around politically charged and socially sensitive issues, at least in their professional capacities. In describing the reputation of his organization, one participant from a community health center said, “I think it’s known for excellent, high standards of health care, giving good health care. Number two is that its mission is to help the community.” This suggests that “professionals” focus on providing high-quality services to individuals; their work is framed in terms of helping individuals rather than systemic change.

Accordingly, community health centers may calibrate their approach to HIV to match the sensibilities of their patients, many of whom may be uncomfortable receiving services where HIV is prominently addressed. One study participant from a community health center described limiting his discussions about HIV to those who appear to be at highest risk:

“I think [accepting HIV education] would be hard for the adults. I mean, you’re not going to [provide HIV education] … with a 60-year-old woman. You have to pick … your target group. … If [I treat] a 40-year-old woman who’s been married for 20 years and they don’t have any marital issues, then I’m not going to mention about HIV. But if it’s a 40-year-old single woman, I will mention about HIV.”

In this participant’s narrative, risk is defined narrowly, without an analysis of the various social issues that might discourage a patient from frankly discussing her sexual activities with a physician. The participant seems guided more by the desire to avoid potential resistance to an uncomfortable message than by the need to uncover current risk factors and provide education that might provide protection in the future. In doing so, this participant may be reinforcing social norms of non-discussion of HIV and a stigmatizing distinction between “high-risk” and “low-risk” individuals.

In a similar vein with regard to playing a limited role in systemic change, the qualitative data regarding the physicians associations suggest that their objectives may include broader social change goals, but with a seeming focus on advancing the status of their ethnic group within their field or protecting their professional turf. For example, one organization held a symposium to bring media attention to the fact that many unlicensed physicians were advertising and practicing in the ethnic community and possibly causing harm to their patients. Curbing the work of unlicensed physicians protects community members from potentially dangerous practices but also ensures the integrity of the medical profession.

The multivariate analysis and the qualitative data indicate that the “Professionals” may not necessarily be expected to lead efforts to change fundamental beliefs or social systems that underlie HIV stigma. Nevertheless, their high scores on the HIV attitudes index in the bivariate analysis indicate that they remain natural allies in community HIV/AIDS work, even if more in the realm of service than in systemic change.

The Community Sentinels

The religious, business, umbrella, and sub-ethnic association organizations that make up the “Community Sentinels” category are arguably the most influential of all the organization types. The sheer number and proportion of organizations in this category (making up more than 65% of the 529 organizations in our database) indicate this category’s significance. Moreover, many of the organizations in this category tend to interact closely with local government officials and also organize large public events, including major parades and street festivals, that are well attended and highly visible in both the ethnic and wider communities.

The influence of “Community Sentinel” organizations in the lives of immigrants is due in part to language and cultural barriers, which isolate immigrants from the wider society. One study of religious organizations in New York City’s Chinatown, for example, found that members relied on their churches and temples for everyday emotional and practical support, ranging from counseling to financial assistance, and also for helping them to “make sense of their new and often hostile environment” (Guest, 2003, p, 131). One Buddhist temple in that study “serve[d] as a site for the exchange of information … regarding jobs, housing, health care, and coping mechanisms for dealing with any of the struggles of daily life” (Guest, 2003, p, 131).

The “Community Sentinels” are the least natural allies in HIV/AIDS work because of their tendency to favor preserving “traditional” values and norms, some of which may promote HIV-related stigma and discourage open discussion of the subjects that need to be covered to engage in effective HIV prevention work. The qualitative data collected in this study indicate that some study participants believe that preserving tradition is a way of “protecting” community members from the undesirable influences of the wider society. This dynamic is paralleled in Abraham’s (2000) study of South Asian immigrant communities and domestic violence, another sensitive issue that, like HIV, requires an examination of and possibly change in traditional norms to address effectively. Both intervening in domestic violence situations and promoting condom use to prevent HIV transmission, for example, require challenges to traditional gender-role norms that subordinate women.

Consistent with what might be expected in light of the more conservative HIV-related attitudes found among these organizations in the quantitative analysis, the qualitative analysis shows that all of the organizations in the “Community Sentinels” category play highly visible leadership roles in the mainstream ethnic community and that many of the organizations seek to advance the standing of the ethnic group in the larger society, acting as the “face” of the community to outsiders. For example, a study participant from a business association said:

“A lot of events, we will invite [City Council members] to join us, so they will have … more knowledge about Chinese community. And then in return, they will do things for our community, and that’s why … the city mainstream society, they show respect to [our organization].

These organizations also seek – to various degrees – to promote “traditional” values and morals and preserve culture and tradition. For example, a study participant from one of the sub-ethnic associations said:

“I think for me the high level idea of going to [the association] is to keep that link [to] being [from our sub-ethnic group], … so my kids know what it is to be [from our sub-ethnic group], and we make sure very specifically that they speak [our language].

We’re very strict on that. And when they are [at the organization’s community center], they’re not to run around. They’re to sit and actually listen, and we explain. … [This organization is] a place to really make people understand what being a [person from our sub-ethnic group] is.”

Participants from these organizations expressed a strong sense of community stewardship, often in terms of a “love” for or desire to promote or maintain important aspects of the culture. One participant from another sub-ethnic association said:

“[Playing a leadership role in my organization] is an obligation because I love my language and my organization, and people have taken … a lot of pains to establish an organization, and I think I’m obligated to make sure things do go well in the organization.”

Some participants expressed their efforts to preserve culture and tradition as a counter-balance to outside influences that might “dilute” their culture, particularly among their children. For example, a study participant explained her motivation for being so active in an umbrella organization:

“I’m creating a role model for my children so they see their mom grew up here [but still] maintained her … culture and value and tradition and language. … Because if parents don’t do it, everything gets diluted as we go down into the generations. So I probably have 50 percent of what my parents had. My son is going to have 50 percent of what I have. Which is okay, but at least it’s there. It’s our job as [people of our ancestry], as parents, to continue carrying that torch.”

Efforts at preserving tradition and its corresponding values may sometimes have the unfortunate effect of discouraging open discussion about HIV and fueling stigma. Although this was evident in many of the interviews in the “Community Sentinels” organizations, it came through especially strongly with the religious organizations.7 For example, a participant from one religious organization said:

“I mean, in promoting [HIV] education we don’t have any problem, but on certain issues we may say no. … Our slogan will be no … I mean we will say that [sex] only is allowed [within] the family structure, with a husband and wife; otherwise it’s no. … We will educate that if you go [the] other way, then you may have these problems and … then your health is at risk. … Yes we can [discuss homosexuality] and we can tell them that this is ‘no’ as a religious [matter]. It is totally forbidden. … That this is wrong.”

Taking the idea of traditional values as protection even further, some religious leaders suggested that HIV education was not necessary because religious teachings on appropriate behavior were more than sufficient to protect people from HIV infection.

“… Teaching [about HIV] should … go to the root. The problem of the root is morality. It’s not teaching them how to avoid it, how to prevent it, or how to get the best doctor, where can you get the best medicine. It’s not like that. It’s teaching from the beginning, from the root. It’s the morality of sex.”

Although the “Community Sentinels” are the least progressive among the three groups of organizations, their influence combined with their focus on behaviors that may be protective (Gray, 2004; Hodge, 2004) and their access to charitable resources and volunteers (Ross-Sheriff, 2001) uniquely position them to confront the challenges of HIV/AIDS among their members and in their neighborhoods and less directly in the wider ethnic community. Constructive engagement with these institutions can foster this role or at least neutralize any negative impact they may have in shaping places with regard to HIV-related taboos and stigma.

The sense of stewardship regarding their communities, expressed by all the Community Sentinel organizations, may be a bridge between them and AIDS service or government organizations interested in partnering with them in HIV/AIDS work. If HIV education and support is presented primarily as an aspect of responsiveness to one’s community, rather than a challenge to what is perceived by them as an already delicate landscape of traditional norms and values, involvement in this work may be seen as more acceptable, or even desirable.

For Community Sentinel organizations that are interested in involvement in HIV-related work, another challenge will be to help them work through their concerns that HIV involvement will tarnish their image and threaten their standing among constituents, possibly by helping them to identify activities that are more consistent with their core missions. Such activities might include charitable contributions to families affected by HIV or sponsorship of health fairs that include HIV information. Although Community Sentinel organizations are seen as authorities in the community, they are dependent on members and thus constrained by the sensibilities of their constituents (Rogers, 2003). They are aware that organizational survival relies on community support and that HIV involvement could alienate their members. As one participant from an umbrella organization put it: “ … We are not that advanced … that liberal, to bring up the subject … they’ll be, oh, [we] must be crazy, you know.”

Conclusion

This exploratory study was designed to begin mapping the various roles that community institutions play in shaping the social landscape in which dialogue about and engagement with taboo or stigmatized public health issues takes place. The data presented in this article were intended as a first step to describe a relatively unknown area. Because this study includes only 22 of the many Chinese and South Asian institutions in NYC, and generally only one of each type of organization within each ethnicity, its findings are not necessarily generalizable to other Chinese and South Asian immigrant institutions in NYC and the US. Moreover, we studied a small sample of mostly leaders and active members within each institution, so their views are more likely to be typical of the leadership rather than the general membership, as noted earlier.

Our preliminary data lay the foundation for further exploration of the role that community institutions can play in stigmatized public health initiatives in Asian immigrant and other communities. An important next step will be to test the framework described here with both larger and different samples, especially in places in which community institutions are likely to be influential. These would include other immigrant communities; communities marginalized because of race, religion or social class; and other small or tightly-knit neighborhoods and communities – in the US and elsewhere. Community institutions’ responses to other stigmatized issues, such as domestic violence, reproductive health or substance use might also be compared to their responses to HIV.

Another key next step will be to develop organization-level interventions that seek to increase involvement of these institutions in stigmatized public health efforts or at least to neutralize any negative impact they may have. Some institutions might be better suited to activities that focus on increasing basic HIV awareness through charitable or other projects that are more consistent with, rather than challenging to, their institutional values. Social norms concerning appropriate behaviors and topics of discussion, overall and in particular venues, may be particularly potent as barriers to effective public health efforts related to stigmatized issues. Thus, community institutions’ involvement in raising general awareness about stigmatized health issues and changing norms about the appropriateness of discussing them may be a vitally important first step that will allow subsequent direct interventions in these neighborhoods to be more effective.

The tension between organization leaders’ mandate to protect tradition and their wish to be relevant to their members, especially among the “Community Sentinel” organizations, represents an opening for organizational change. Because of the social nature of stigma, increasing involvement of “Community Sentinel” organizations in stigmatized public health efforts may require a better understanding of the role of social networks and innovators, within and between organizations, in either impeding or promoting the adoption of new organizational activities or norms. Even in our small sample, views varied within organizations, sometimes widely, suggesting routes through which change may be encouraged. Understanding how organizational change builds on or threatens organizations’ structural roles as “Paradigm Shifters,” “Professionals,” and “Community Sentinels” may help to refine strategies for increasing their involvement and identifying their potential strengths and weaknesses in HIV-related work, as well as in other stigmatized or sensitive public health initiatives.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant Number R21HD43012). The authors would also like to thank anonymous reviewers, research staff members Mamatha Bhagavan and Xiaoting Luo, and the participating leaders and members of community institutions who generously shared their time and stories.

Footnotes

Sanders and Nee (1987) reasoned that if the ethnic enclave is beneficial for immigrants, then immigrants connected with enclave economies should show greater returns to their human capital (education and work experience). Sanders and Nee found that entrepreneurs among immigrants in ethnic enclaves showed positive returns to human capital both in the enclave and outside. Workers, on the other hand, only showed a significant positive return to human capital outside the enclave economy. Sanders and Nee suggested that instead of being beneficial to workers, enclave economies allow entrepreneurs to exploit workers heavily.

This agency was not included in the study as the study deliberately focused on non-AIDS organizations to understand their views. This example is drawn from personal communication between the author and the executive director and program director of the organization.

By South Asian, we mean individuals from countries such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Although the study intended to focus on Chinese and Indian immigrant organizations specifically, it was expanded to include pan-ethnic South Asian organizations, which are prevalent in NYC. Organizations that focused exclusively on a specific South Asian ethnicity other than Indian were not included in the study.

Proc GLIMMIX in SAS also generates more accurate standard errors when the residuals exhibit non-constant variance across levels of the predicted values (heteroskedasticity), which was the case with our data.

It should be noted that interpreting the change of position of the healthcare organization type is made difficult by the small number of participants in the category (n=3).

This excludes a founding year of 1900 for one of the workers’ rights organizations. This is because the organization did not start as an Asian immigrant organization but evolved into one as the labor force in the area in that industry changed over the years.

It should be noted, however, that the religious organizations in our study distinguished themselves from the other organizations in the Professional and Community Sentinel categories by having the highest positive (but not statistically significant) coefficient in the multivariate analysis, indicating the most supportive attitudes in these two groupings after controlling for a range of demographic factors and HIV knowledge. This may be a reflection of the religious organizations’ imperative to show compassion, a theme that emerged most strongly in the religious organization interviews, despite significant misconceptions about HIV transmission and harsh judgments of people living with HIV (described in a related paper by the authors [placeholder for authors’ paper citation]). Our finding of a co-existence of both judgmental and compassionate attitudes among religious leaders is consistent with findings in a study by Takahashi (1997).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

John J. Chin, Department of Urban Affairs and Planning, Hunter College of the City University of New York, 695 Park Avenue, West Building, Room 1612A, New York, NY 10065, USA

Torsten B. Neilands, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, Box 0886, 50 Beale Street, Suite 1300, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94105, USA

Linda Weiss, The New York Academy of Medicine, Center for Urban Epidemiologic Studies, 1216 5th Avenue, New York, NY 10029, USA.

Joanne E. Mantell, HIV Center for Clinical & Behavioral Studies at the NYS Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Drive, Unit 15, New York, NY 10032, USA

References

- Abelmann N, Lie J. Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham M. Speaking the unspeakable: Marital violence among South Asian immigrants in the United States. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V. Gender, religious involvement, and HIV/AIDS prevention in Mozambique. Soc Sci Med. 2005;6(17):1529–39. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang I. To be or not to be Chinese: diaspora, culture and postmodern ethnicity. Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science. 1993;2(11):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Basch L, Glick Schiller N, Szanton Blanc C. Nations unbound: transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments, and deterritorialized nation-states. Gordon and Breach; Langhorne, PA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya G. Health Care Seeking for HIV/AIDS among South Asians in the United States. Health and Social Work. 2004;2(92):106–115. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin D, Kroesen KW. Disclosure of HIV infection among Asian/Pacific Islander American women: Cultural stigma and social support. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 1999;5(3):222–35. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Coates TJ, Catania JA, Lew S, Chow P. High HIV risk among gay Asian and Pacific Islander men in San Francisco. AIDS. 1995;9(3):306–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CJ. The Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS and the breakdown of Black politics. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. Coding, writing memos, and diagramming. In: Chenitz WC, Swanson JM, editors. From Practice to Grounded Theory: Qualitative Research in Nursing. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co; Reading, MA: 1986. pp. 102–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall A, Jewkes R. What is Participatory Research? Social Science & Medicine. 1995;4(112):1667–76. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David EA, McCaughan EJ. Editors’ introduction: Art, power, and social change. Social Justice. 2006;33(2):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas M. Purity and Danger. Routledge; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Eckholdt HM, Chin JJ, Manzon-Santos JA, Kim DD. The needs of Asians and Pacific Islanders living with HIV in New York City. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1997;9(6):493–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans H. Second Generation Decline: Scenarios for the Economic and Ethnic Futures of the Post-1965 American Immigrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1992;15(2):173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Gray PB. HIV and Islam: Is HIV Prevalence Lower among Muslims, Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:1751–6. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest KJ. God in Chinatown: Religion and Survival in New York’s Evolving Immigrant Community. New York University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge DR. Working with Hindu Clients in a Spiritually Sensitive Manner. Social Work. 2004;49(1):27–38. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu DJ, Fleming PL, Castro KG, et al. How important is race/ethnicity as an indicator of risk for specific AIDS-defining conditions? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10(3):374–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Policy brief: Critical policy challenges in the third decade of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Menlo Park, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kang E, Rapkin BD, Springer C, Kim JH. The “Demon Plague” and Access to Care among Asian Undocumented Immigrants Living with HIV Disease in New York City. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5(2):49–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1022999507903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz P. Caribbean New York: Black Immigrants and the Politics of Race. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns R, Moon G. From medical to health geography: novelty, place and theory after a decade of change. Progress in Human Geography. 2002;26(5):605–25. [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal MS. Becoming American, Being Indian: An Immigrant Community in New York City. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kibria N. Family tightrope: The changing lives of Vietnamese Americans. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kim I. The Koreans: Small Business in an Urban Frontier. In: Foner N, editor. New Immigrants in New York. Columbia University Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kwong P. The New Chinatown. The Noonday Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Light I, Sabagh G, Bozorgmehr M, Der-Martirosian C. Internal ethnicity in the ethnic economy. Ethnic and racial studies. 1995;16:581–97. [Google Scholar]

- Loue S, Lane SD, Lloyd LS, Loh L. Integrating Buddhism and HIV Prevention in U.S. Southeast Asian Communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1999;10(1):100–21. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 1998;10(2):31–6. [Google Scholar]

- MMWR. HIV prevalence, unrecognized infection, and HIV testing among men who have sex with men--five U.S. cities, June 2004–April 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(24):597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya JC. Immigrants and associations: A global and historical perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2005;31(5):833–64. [Google Scholar]

- Nee V, Sanders J, Sernau S. Job transitions in an immigrant metropolis: Ethnic boundaries and the mixed economy. American sociological review. 1994;59:849–72. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Minority Health. US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ong A. On the edge of empires: flexible citizenship among Chinese in diaspora. Positions. 1993;1(3):745–778. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Stepick A. City on the Edge: the Transformation of Miami. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J, Nee V. Limits of Ethnic Solidarity in the Ethnic Enclave. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:745–67. plus Portes and Jenson critique and rejoinder by Sanders and Nee. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JM, Nee V. Immigrant self-employment: the family as social capital and the value of human capital. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:231–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Sheriff F. Immigrant Muslim Women in the United States: Adaptation to American Society. Journal of Social Work Research. 2001;2(2):283–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen S. Immigration and local labor markets. In: Portes A, editor. The economic sociology of immigration. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1995. pp. 87–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley D. Geographies of exclusion: society and difference in the West. Routledge; London and New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sy FS, Chng CL, Choi ST, Wong FY. Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS among Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1998;10(3 Suppl):4–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi LM. Stigmatization, HIV/AIDS, and communities of color: exploring response to human service facilities. Health Place. 1997;3(3):187–99. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(97)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitam FL, Dizon MJ. Occupational choice and sexual orientation in cross-cultural perspective. International Review of Modern Sociology. 1979;9(2):137–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Wilson P, Hsueh J, Rosman EA, Chin J, Kim JH. What front-line NGO staff can tell us about culturally anchored theories of change in HIV prevention for Asian/Pacific Islanders in the U.S. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;32(1–2):143–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1025611327030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka MR, Schustack A. Disclosure of HIV status: cultural issues of Asian patients. AIDS Patient Care & Stds. 2001;15(2):77–82. doi: 10.1089/108729101300003672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi IF, Crepaz N, Song R, Wan CK, Lin LS, Hu DJ, Sy FS. Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS among Asians and Pacific Islanders in the United States. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(5):405–17. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.5.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Chinatown: the socioeconomic potential of an urban enclave. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1992. [Google Scholar]