Abstract

OBJECTIVE—The G-protein–coupled receptor Gpr40 is expressed in β-cells where it contributes to free fatty acid (FFA) enhancement of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (1–4). However, other sites of Gpr40 expression, including the intestine, have been suggested. The transcription factor IPF1/PDX1 was recently shown to bind to an enhancer element within the 5′-flanking region of Gpr40 (5), implying that IPF1/PDX1 might regulate Gpr40 expression. Here, we addressed whether 1) Gpr40 is expressed in the intestine and 2) Ipf1/Pdx1 function is required for Gpr40 expression.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS—In the present study, Gpr40 expression was monitored by X-gal staining using Gpr40 reporter mice and by in situ hybridization. Ipf1/Pdx1-null and β-cell specific mutants were used to investigate whether Ipf1/Pdx1 controls Gpr40 expression. Plasma insulin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), and glucose levels in response to acute oral fat diet were determined in Gpr40 mutant and control mice.

RESULTS—Here, we show that Gpr40 is expressed in endocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract, including cells expressing the incretin hormones GLP-1 and GIP, and that Gpr40 mediates FFA-stimulated incretin secretion. We also show that Ipf1/Pdx1 is required for expression of Gpr40 in β-cells and endocrine cells of the anterior gastrointestinal tract.

CONCLUSIONS—Together, our data provide evidence that Gpr40 modulates FFA-stimulated insulin secretion from β-cells not only directly but also indirectly via regulation of incretin secretion. Moreover, our data suggest a conserved role for Ipf1/Pdx1 and Gpr40 in FFA-mediated secretion of hormones that regulate glucose and overall energy homeostasis.

Mature β-cells respond to elevated glucose levels by secreting insulin in a tightly controlled manner. The physiological response of the β-cell to elevated blood glucose levels is critical for maintenance of normoglycemia, and impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) is a prominent feature of overt type 2 diabetes. Although glucose is recognized as the major stimulator of insulin secretion from β-cells, other stimuli, such as amino acids, hormones, and free fatty acids (FFAs), also influence insulin secretion (6,7). Thus, under normal settings, insulin secretion from β-cells in response to food intake is evoked by the collective stimuli of nutrients, such as glucose, amino acids, and FFAs, and hormones like the incretins glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) (6,7).

FFAs are known to influence insulin secretion from β-cells primarily by enhancing GSIS. The FFA receptor Gpr40 is preferentially expressed in β-cells and is activated by medium- to long-chain FFAs, thereby triggering a signaling cascade that results in increased levels of [Ca2+]i in β-cell lines and subsequent stimulation of insulin secretion (1,3,8). Gpr40-deficient β-cells secrete less insulin in response to FFAs, providing evidence that Gpr40 mediates part of the FFA stimulatory effect on insulin secretion (2,4). However, loss of Gpr40 protects mice from obesity-induced hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinemia, fatty liver development, increased hepatic glucose output, and hypertriglyceridemia (2). These data provide evidence that FFA stimulation of insulin secretion via Gpr40 contributes to obesity-induced hyperinsulinemia, which in turn is linked to fatty liver development and hepatic insulin resistance.

Lipids and FFAs also stimulate the secretion of several gut “satiety” hormones, including cholocystokinine (CCK), GLP1, and peptide YY (PYY), and the related FFA receptor Gpr120 has been suggested to mediate FFA-stimulated secretion of GLP-1 from L-cells (9). In addition, stimulation of the G-protein–coupled receptor Gpr119, the ligands of which are phospholipids and fatty acid amides, have also been shown to result in increased GLP-1 and GIP secretion (10). RT-PCR analyses have suggested that Gpr40 is expressed in the intestine, leaving open a potential role also for Gpr40 in FFA stimulation of gut hormones (1,11).

The transcription factor IPF1/PDX1 is highly expressed in β-cells and controls key aspects of β-cell function by regulating the expression of genes involved in glucose sensing, insulin gene expression, and insulin secretion (12–14). Loss or perturbation of Ipf1/Pdx1 function in β-cells leads to impaired GSIS and consequently diabetes or glucose intolerance in both mice and humans (12,15), highlighting the central role for Ipf1/Pdx1 in ensuring β-cell function. Recently, IPF1/PDX1 has been shown to bind to an enhancer element within the 5′-flanking region of Gpr40 (5), implying that Ipf1/Pdx1 might regulate Gpr40 expression in β-cells and thus FFA-mediated stimulation of insulin secretion.

To determine whether Gpr40 is expressed in the intestine and whether Ipf1/Pdx1 function is required for Gpr40 expression, we investigated the expression of Gpr40 in wild-type and Ipf1/Pdx1 mutant mice. Here, we show that Gpr40 is expressed in endocrine cells of gastrointestinal tract, including cells expressing the incretin hormones GLP-1 and GIP. We also show that Ipf1/Pdx1 is required for Gpr40 expression in β-cells and endocrine cells of the anterior gastrointestinal tract. Moreover, we show that secretion of GLP-1 and GIP is diminished in Gpr40-null mutant mice. Together, these data raise the possibility that Gpr40 modulates FFA-stimulated insulin secretion from β-cells not only directly but also indirectly via regulation of incretin secretion.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

The animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Umeå University and conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The generation of Gpr40+/lacZ, Ipf1/Pdx1−/−, and Rip1/Ipf1Δ have been previously described (2,12,16). Briefly, Gpr40+/lacZ mice were generated by replacing the Gpr40 open reading frame with the lacZ gene encoding β-galactosidase (β-gal). In Ipf1/Pdx1−/−-null mice, exon 2, encoding the DNA-binding homeodomain, was deleted. The Rip1/Ipf1Δ mice are generated by breeding mice in which exon 2 of the Ipf1/Pdx1 gene is flanked by two loxP sites with mice where the Cre-recombinase is under the control of Rat insulin 1 (Rip1) promoter. In the resulting Rip1/Ipf1Δ mice, exon 2 of Ipf1/Pdx1 becomes out-recombined specifically in β-cells as a consequence of Cre-recombinase expression and activity.

Glucose, insulin, GIP, GLP-1, glucagon, FFA, and triglyceride measurements.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests were performed on overnight-fasted, sedated mice essentially as previously described (2). For oral glucose tolerance test, 300 μl 20% glucose solution was administered to overnight-fasted, sedated mice. For the acute, high-fat diet experiments, a paste was generated by mixing 7.5 g diet D12309 (58% kcal fat content; Research Diets) with 3 ml tap water, and 300 mg paste was then administered by oral gavage to overnight-fasted, sedated mice. Blood glucose levels were measured using a Glucometer Elite (Bayer), serum insulin levels were measured using ELISA (Mercodia), and total plasma GIP and GLP-1 concentrations were determined according to the manufacturer's instructions for the GIP-ELISA (EZRMGIP-55K; Linco Research) and the GLP-1-RIA (GLP1T-36HK; Linco Research) kit. Plasma glucagon levels were determined using the Glucagon RIA kit (GL-32K; Linco Research). FFA and triglyceride measurements were done according to the manufacturer's instructions using FFAs, Half-micro test (Roche), and Accutrend GCT Triglycerides (Roche).

In situ hybridizations, X-gal staining, and immunohistochemistry.

In situ hybridization using DIG-labeled probes specific for the mouse Gpr40 transcript was carried out on embryonic day (e) 17 embryos as previously described (2). Immunohistochemical localization of antigens, double-label immunohistochemistry, and X-gal staining on tissues and confocal microscopy were carried out as previously described (2). Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti–β-gal (Cappel), chicken anti–β-gal (AbCam), rabbit anti-GIP (Peninsula), rabbit anti–GLP-1 (Peninsula), guinea pig anti-gastrin (Euro Diagnostics), goat anti-ghrelin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-CCK (Chemicon), rabbit anti-secretin, rabbit anti-substance P, rabbit anti-PYY, rabbit anti-neuropeptide 4 (NPY), rabbit anti-serotonin (Euro-Diagnostica), rabbit anti-somatostatin (Dako), and rabbit anti-Ipf1 (17). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa 488 anti-goat, Alexa 488 anti–guinea pig, Alexa 594 anti–guinea pig, Alexa 594 anti-rabbit, Alexa 594 anti-goat (all from Molecular Probe), Cy3 anti-rabbit, and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-chicken (The Jackson Laboratories). The gut hormone and Gpr40 expression analyses were performed on 2- to 3-month-old mice. For the antibody cocktail experiment, we made a two-step staining procedure: The tissue sections was first incubated with a mixture of antibodies directed against GIP, GLP-1, ghrelin, CCK, and gastrin, and for these, the corresponding Alexa 594-fluorochrome secondary antibodies were used. Next, the tissue sections were incubated with antibodies directed against β-gal for which a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody was used.

Cell counting.

Pylorus and the three proximal centimetres of small intestine corresponding to the duodenum and part of the jejunum were isolated from wild-type, Gpr40+/lacZ, and Gpr40lacZ/lacZ (n = 3) nonfasted mice, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 1–2 h, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose at 4°C overnight, frozen in Tissue-Tek (Sakura), and kept at −80°C. Three 8-μm-thick sections where collected on every slide with ∼160 μm between sections. The sections of pylorus/duodenum were stained with antibodies against GIP, GLP-1, ghrelin, CCK, gastrin, PYY, secretin, serotonin, substance P, and β-gal and manually analyzed for distribution and colocalization of the different markers. Colocalization between β-gal and GLP-1 was also determined in the distal 3 cm of the ileum, i.e., close to the appendix, in Gpr40+/lacZ mice.

Quantification of mRNA expression levels.

cDNA was prepared from total RNA isolated from islets (18) and from e16 pylorus/duodenum and the distal part of the ileum using NucleoSpin RNAII-kit (635990; Machery-Nagel) and Super SMART PCR (635000; Clontech). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed using the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ABI) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Expression of the β-2-microglobulin (β2M), TATA-box–binding protein (TBP), β-actin, and glyceraldhyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) genes was used to normalize expression levels. Primer sequences were as follows: β-actin, 5′-GCTCTGGCTCCTAGCACCAT-3′ and 5′-GCCACCGATCCACACAGAGT-3′; Gapdh, 5′-CGTGTTCCTACCCCCAATGT-3′ and 5′-TGTCATCATACTTGGCAGGTTTCT-3′; β2M, 5′-GCTATCCAGAAAACCCCTCAAA-3′ and 5′-CTGTGTTACGTAGCAGTTCAGTATGTTC-3′; TBP, 5′-GAATTGTACCGCAGCTTCAAAA-3′ and 5′-AGTGCAATGGTCTTTAGGTCAAGTT; Ipf1/Pdx1, 5′-TAGGACTCTTTCCTGGGACCAA-3′ and 5′-AATAAAAAGGGTACAAACTTGAGCGT-3′; and Gpr40, 5′-TTTCATAAACCCGGACCTAGGA-3′ and 5′-CCAGTGACCAGTGGGTTGAGT-3′.

Statistical analyses were performed by an unpaired Student's t test.

RESULTS

Gpr40 is expressed in cells of the gastrointestinal tract.

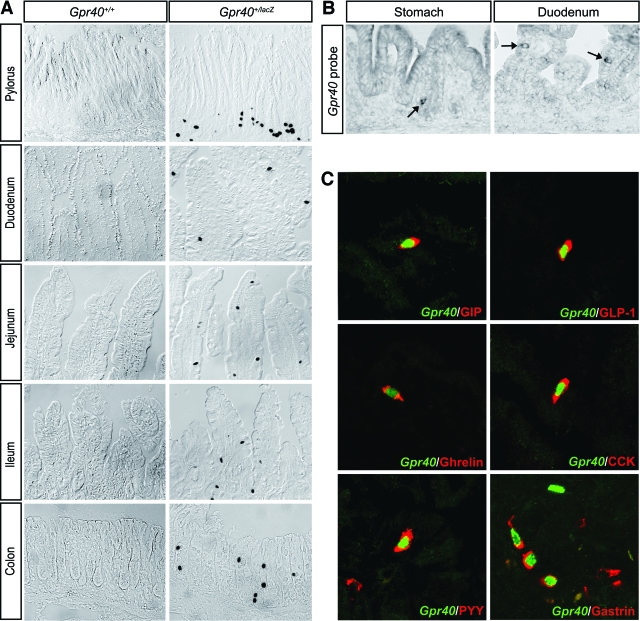

Gpr40 has been suggested to be expressed at other sites than β-cells, including in the intestine (1,11). However, these Gpr40 expression studies build on RT-PCR analyses, and because the coding region of Gpr40 lacks an intron, contaminating genomic DNA might give false positives in PCR analyses. To avoid such problems, we previously made use of the lacZ reporter gene insertion into the Gpr40 locus of targeted Gpr40+/lacZ mice and showed that Gpr40 is not expressed in brain, liver, muscle, or adipose tissue (2). We therefore extended our analyses of Gpr40 expression using the Gpr40+/lacZ mice to elucidate whether Gpr40 is expressed in the gastrointestinal tract. Distinct X-gal staining was evident in scattered epithelial cells of the gastric pylorus, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon (Fig. 1A). The expression of Gpr40 in the epithelium of the stomach and intestine was evident from e14.5–e15 (data not shown), i.e., coincident with the appearance of differentiated endocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract. The expression of Gpr40 in pylorus and duodenum was confirmed by in situ hybridization analyses using a Gpr40 riboprobe (Fig. 1B). Together, these data demonstrate that Gpr40 is expressed in scattered cells distributed throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

FIG. 1.

Gpr40 is expressed in gut enteroendocrine cells. A: X-gal staining of sections of pylorus, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon in 2-month-old Gpr40+/+ and Gpr40+/lacZ mice. B: In situ hybridization using Gpr40-specific probes on sections of neonatal epithelium in stomach and duodenum. Arrows indicate cells expressing Gpr40 mRNA. C: Confocal sections of 2- to 3-month-old adult Gpr40+/lacZ pylorus and duodenum stained with anti–β-gal antibodies (green) to indicate Gpr40 expression and antibodies specific for the indicated enteroendocrine hormones (red). (Please see http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db08-0307 for a high-quality digital representation of this figure.)

The Gpr40+ cells of the gastrointestinal tract represent enteroendocrine cells.

To determine the identity of the gastrointestinal cells expressing Gpr40, we next performed double immunohistochemical analyses of the epithelium of the gastric pylorus, duodenum, and ileum in 2- to 3-month-old mice using anti–β-gal antibodies and antibodies specific for different gastrointestinal hormones. The β-gal+, i.e., Gpr40+, cells were shown to express a wide variety of endocrine hormones. In the pylorus and duodenum, β-gal/Gpr40 expression colocalized with gastrin, GIP, GLP-1, ghrelin, CCK, PYY, secretin, serotonin, and substance P expression; and in the ileum, β-gal/Gpr40 expression colocalized predominantly with that of GLP-1 (Fig. 1C; data not shown). In contrast, no coexpression of β-gal/Gpr40 and somatostatin or NPY was observed (data not shown). The degree of β-gal/Gpr40 expression varied between ∼20 and 55% for the different gastrin, GIP, GLP-1, ghrelin, CCK, PYY, secretin, and serotonin hormone-expressing cells (Table 1), and <1% of the substance P+ cells expressed β-gal/Gpr40 (data not shown). However, immunohistochemical analyses using a cocktail of gut hormone antibodies, including GIP, GLP-1, ghrelin, CCK, and gastrin and β-gal antibodies, revealed that virtually all β-gal/Gpr40-expressing cells were hormone positive (data not shown). The distribution and number of enteroendocrine cells were normal in Gpr40lacZ/lacZ mice (Table 2; data not shown). Thus, Gpr40 is expressed both in insulin-producing β-cells and hormone-producing cells of the gastrointestinal tract.

TABLE 1.

Coexpression of gut hormones and Gpr40

| Gastrin | GIP | GLP-1 | Ghrelin | CCK | PYY | Secretin | Serotonin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52 ± 0.6 | 50 ± 5 | 55 ± 5 | 34 ± 3 | 50 ± 1 | 21 ± 2 | 30 ± 4 | 19 ± 3 |

Data are percentage of hormone-expressing cells coexpressing β-gal/Gpr40. Sections of pylorus (gastrin) and duodenum (GIP, GLP-1, ghrelin, CCK, PYY, secretin, and serotonin) from 2- to 3-month-old Gpr40+/lacZ mice (n = 3) were double stained for gut hormones and β-gal.

TABLE 2.

Gut hormone-expressing cells in Gpr40lacZ/lacZ mice

| GIP | GLP-1 | Ghrelin | CCK | Gastrin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gpr40+/+ | 490 ± 113 | 279 ± 38 | 1,114 ± 249 | 492 ± 40 | 689 ± 20 |

| Gpr40lacZ/lacZ | 530 ± 45 | 246 ± 36 | 1,040 ± 171 | 383 ± 81 | 754 ± 52 |

| t test | 0.63 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.87 | 0.46 |

Data are n. Hormone-expressing cells were counted on sections from pylorus (gastrin) and duodenum (GIP, GLP-1, ghrelin, and CCK) in 2- to 3-month-old Gpr40+/+ (n = 3) and Gpr40lacZ/lacZ (n = 3) mice.

Impaired secretion of GIP and GLP-1 in Gpr40-null mutants.

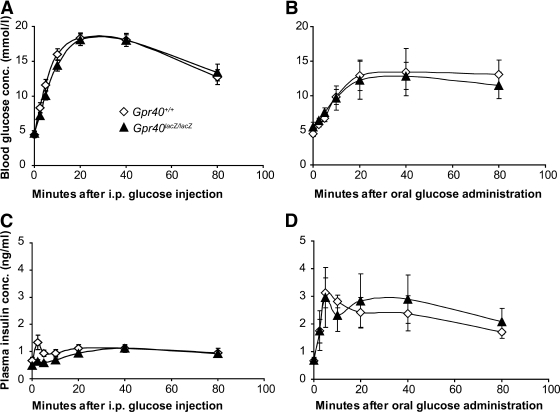

GIP and GLP-1 hormones are secreted from the intestinal K- and L-cells, respectively (19), and the secretion of GIP and GLP-1 hormones can be stimulated both by glucose and FFAs (20,21). The secretion of GLP-1 and GIP hormones into the circulation positively influences insulin secretion. This so-called incretin effect is evident when comparing oral and intravenous or intraperitoneal administration of glucose; oral glucose administration triggers a more robust insulin secretory response (19). The expression of Gpr40 in both GIP-and GLP-1–expressing cells leaves open the possibility that Gpr40 may affect insulin secretion not only directly by virtue of its expression in β-cells, but also indirectly via regulation of incretin secretion. Consistent with the FFA but not glucose responsiveness of Gpr40, no difference in glucose clearance rates or insulin secretion was observed between Gpr40lacZ/lacZ and wild-type mice, regardless of whether glucose was administered orally or injected in the peritoneum (Fig. 2A–D).

FIG. 2.

Oral glucose tolerance is normal in Gpr40lacZ/lacZ mice. Blood glucose (A and B) and plasma insulin (C and D) levels in 2- to 3-month-old Gpr40+/+ (⋄) and Gpr40lacZ/lacZ (▴) mice after intraperitoneal glucose injections (A and C) and oral glucose administration (B and D). Gpr40+/+ (n = 16) and Gpr40lacZ/lacZ (n = 16) for the intraperitoneal glucose injections. Gpr40+/+ (n = 6) and Gpr40lacZ/lacZ (n = 5) for the oral glucose administration test.

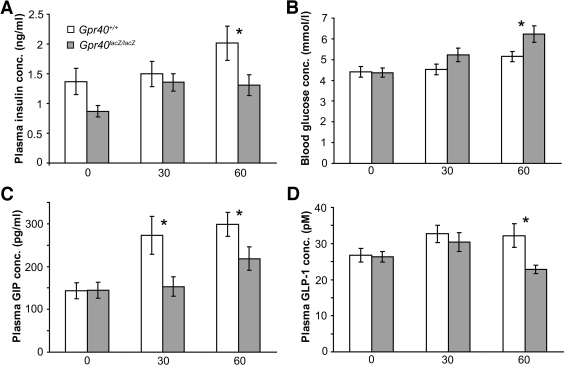

We next explored the glucose and insulin response to acute, oral administration of high-fat diet in Gpr40lacZ/lacZ and wild-type mice. Plasma levels of FFAs, triglycerides, and glucagon were similar in oral high-fat diet–treated Gpr40lacZ/lacZ and wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 1 available in an online appendix at http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db08-0307). In contrast, plasma insulin levels were reduced and blood glucose levels were increased at 60 min in Gpr40lacZ/lacZ compared with that of wild-type mice in response to oral high-fat diet (Fig. 3A and B), suggesting that incretin secretion in response to fat might be impaired in Gpr40lacZ/lacZ mice. Analyses of incretin levels after oral high-fat diet showed that total plasma GIP levels were reduced at 30 and 60 min and total plasma GLP-1 levels were reduced at 60 min compared with that of wild types (Fig. 3C and D). In contrast, no difference in total GIP or GLP-1 levels were observed at 30 or 60 min after oral glucose administration (Supplementary Fig. 2). Taken together, these data provide evidence for a role for Gpr40 in FFA-mediated secretion of the incretins GIP and GLP-1.

FIG. 3.

Reduced plasma levels of GIP and GLP-1 in Gpr40lacZ/lacZ mice in response to fat diet. Plasma insulin, GIP (total), GLP-1 (total), and blood glucose levels (A–D) were determined in 2- to 3-month-old Gpr40+/+ (n = 10–16, □) and Gpr40lacZ/lacZ (n = 8–20,

) mice after oral high-fat diet administration. x-axis indicates minutes after oral gavage. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 for Gpr40+/+ vs. Gpr40lacZ/lacZ.

) mice after oral high-fat diet administration. x-axis indicates minutes after oral gavage. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 for Gpr40+/+ vs. Gpr40lacZ/lacZ.

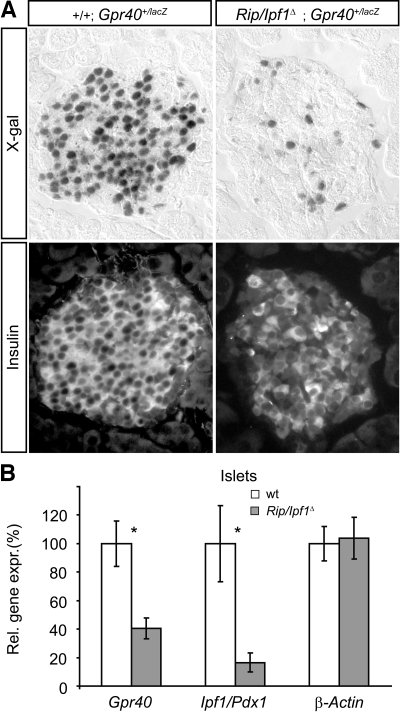

Ipf1/Pdx1 is required for the expression of Gpr40 in β-cells.

Recent data show that the transcription factor IPF1/PDX1 can bind to an enhancer element within the Gpr40 5′-flanking region (5), leaving open the possibility that IPF1/PDX1 might regulate Gpr40 expression. Ipf1/Pdx1-null mutant mice fail to form a pancreas and thus die at the neonatal stage (16), precluding any analyses of a role for IPF1/PDX1 in the regulation of Gpr40 expression in β-cells. We have, however, previously generated β-cell–specific Ipf1/Pdx1 mutants, denoted RIP/Ipf1Δ mice, using the Cre-LoxP system (12). The conditional inactivation of Ipf1/Pdx1 in β-cells of RIP/Ipf1Δ mice results in β-cell dysfunction due to reduced expression of key β-cell components, including insulin, glucose transporter type 2, and PC1/3, and the mice consequently show severely impaired insulin secretion and develop diabetes (12). To elucidate whether Gpr40 expression was regulated by Ipf1/Pdx1 in adult β-cells, we bred the Gpr40+/lacZ allele into the RIP/Ipf1Δ background. The Gpr40+/lacZ mice carry the lacZ gene targeted into the Gpr40 locus, thus allowing monitoring of Gpr40 expression by X-gal staining. In RIP/Ipf1Δ mice, the conditional inactivation of the Ipf1/Pdx1 gene in β-cells occurs progressively after birth, and the mice develop overt diabetes when Ipf1/Pdx1 has been inactivated in ∼80% of the β-cells (12).

In 5-week-old Ipf1/Pdx1+/+;Gpr40+/lacZ control mice, strong, uniform X-gal staining was observed in the β-cells (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the majority of the β-cells in islets of age-matched, glucose-intolerant but not overt diabetic RIP/Ipf1Δ;Gpr40+/lacZ mice were X-gal−, providing evidence that conditional inactivation of Ipf1/Pdx1 in β-cells results in a loss of Gpr40 expression (Fig. 4A). Quantitative RT-PCR of cDNA prepared from islets confirmed the decreased expression of Gpr40 in β-cells of RIP/Ipf1Δ mice and showed that Gpr40 expression was reduced to a similar extent to that of Ipf1/Pdx1 in isolated islets (Fig. 4B). Together, these data provide evidence that Ipf1/Pdx1 (directly or indirectly) is required for Gpr40 expression in β-cells.

FIG. 4.

Gpr40 expression in β-cells cells requires Ipf1/Pdx1. A: X-gal–stained sections (top panel) of 5-week-old adult islets from Ipf1/Pdx1+/+;Gpr40+/lacZ and RIP/Ipf1Δ;Gpr40+/lacZ mice counterstained with anti-insulin antibodies (bottom panel). B: Quantitative real-time RT-PCR expression analyses of islet cDNA from Ipf1/Pdx1+/+ (□, n = 4) and RIP/Ipf1Δ (□, n = 6) mice. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 for Ipf1/Pdx1+/+ vs. RIP/Ipf1Δ islets.

Gpr40 expression in endocrine cells of the anterior gastrointestinal tract requires Ipf1/Pdx1.

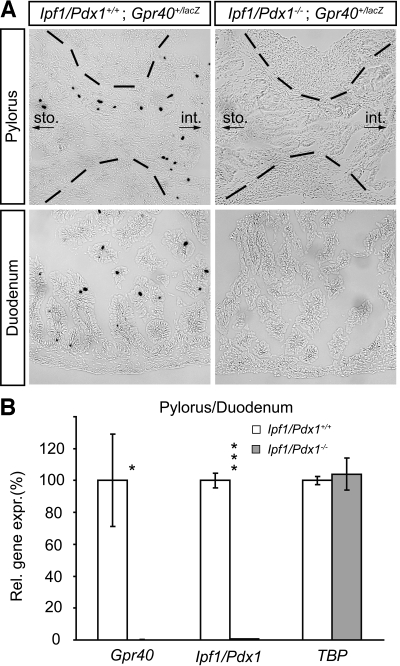

Apart from β-cells, IPF1/PDX1 is expressed also in hormone-producing cells of the gastric pylorus and duodenum, where it has been shown to be required for the expression of several hormones (22). The similar expression profiles observed for IPF1/PDX1 and Gpr40 raised the possibility that the expression of Gpr40 in endocrine cells of the anterior gastrointestinal tract, like that in β-cells, is dependent on Ipf1/Pdx1. To explore a potential role for IPF1/PDX1 in regulating Gpr40 expression, we bred the Gpr40+/lacZ allele into the Ipf1/Pdx1-null mutant (16) background and analyzed the intestinal expression of Gpr40 by X-gal staining. Because Ipf1/Pdx1-null mutants die at the neonatal stage, Gpr40 expression analyses were performed on late-stage, embryonic gastrointestinal tissue. In contrast to control Ipf1/Pdx1+/+;Gpr40+/lacz mice, no X-gal+, i.e., Gpr40-expressing, cells were observed in the gastric pylorus and duodenum of Ipf1/Pdx1−/−;Gpr40+/lacz embryos (Fig. 5A). Quantitative RT-PCR on cDNA isolated from the gastric pylorus and duodenum of wild-type and Ipf1/Pdx1−/− embryos confirmed that expression of Gpr40 in these regions of the gastrointestinal tract is dependent on Ipf1/Pdx1 (Fig. 5B). In the more distal regions of gastrointestinal tract, including the ileum, where IPF1/PDX1 is not expressed, β-gal/Gpr40 expression was unaffected in Ipf1/Pdx1-null mice (data not shown). Together, these data provide evidence for a conserved role for Ipf1/Pdx1 in regulating Gpr40 expression in pancreatic β-cells and endocrine cells of the gastric pylorus and duodenum.

FIG. 5.

Gpr40 expression in enteroendocrine cells requires Ipf1/Pdx1. A: X-gal–stained sections of the pyloric sphincter and in duodenum of e17 Ipf1/Pdx1+/+;Gpr40+/lacZ and Ipf1/Pdx1−/−;Gpr40+/lacZ embryos. B: Quantitative real-time RT-PCR expression analysis of cDNA isolated from pylorus/duodenum of Ipf1/Pdx1+/+ (□, n = 3) and Ipf1/Pdx1−/− embryos (

, n = 3). Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 for Ipf1/Pdx1+/+ vs. Ipf1/Pdx1−/−. Brackets in A indicate the border of the smooth muscle layer surrounding the lumen of the gut tube. sto., stomach; int., intestine.

, n = 3). Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 for Ipf1/Pdx1+/+ vs. Ipf1/Pdx1−/−. Brackets in A indicate the border of the smooth muscle layer surrounding the lumen of the gut tube. sto., stomach; int., intestine.

DISCUSSION

The FFA-responsive G-protein–coupled receptor Gpr40 is expressed in pancreatic β-cells where it contributes to FFA-mediated enhancement of glucose-induced insulin secretion (1–4), and Gpr40 mutant mice do not develop hyperinsulinemia on a high-fat diet (2). Here, we show that Gpr40 is expressed also in hormone-producing cells of the gastrointestinal tract, including GIP+ and GLP-1+ cells. FFAs are known to stimulate the secretion of both GIP and GLP-1 incretin hormones (20,21), and other G-protein–coupled receptors, such as Gpr120 and Gpr119, have been implicated in the secretion of incretin hormones (9,10). Activation of Gpr120 by α-linolenic acid, docosahexaoienic, or palmitoleic acid in STC-1 cells promoted GLP-1 secretion (9), and upon an oral load of the Gpr119 agonist AR231453, plasma concentrations of GLP-1 and GIP increased in control animals but not in Gpr119-deficient mice (10). In this study, we found that Gpr40-null mice show impaired secretion of both GIP and GLP-1 in response to acute, oral fat diet administration with a concomitant reduction in insulin secretion and glucose clearance. Together, these findings provide evidence for a role for Gpr40 in FFA stimulation of incretin secretion. The expression of Gpr40 in endocrine cells of gastrointestinal tract leaves open the possibility that Gpr40, as a component of the entero-insular axis, may regulate insulin secretion in response to fatty acids at several levels. Thus, apart from directly influencing insulin secretion from β-cells via circulating FFAs, Gpr40 may indirectly stimulate GSIS from β-cells by modulating the secretion of the incretin hormones GIP and GLP-1 in response to FFAs present in the gastrointestinal lumen (23,24).

The gut hormones ghrelin and CCK play important and opposing roles in regulating food intake; ghrelin is considered to be an appetite hormone, and CCK a satiety hormone. The release of these two hormones is regulated by food intake, especially fat. Ghrelin levels in blood circulation are reduced by long-chain fatty acids (25), whereas CCK levels are increased by medium- to long-chain fatty acids (26). However, Gpr40 mutant mice show a normal growth rate on both control and high-fat diet and do not present with any apparent signs of perturbed food intake patterns (2,4). Ghrelin has also been suggested to influence insulin secretion, but the data are conflicting; both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on insulin secretion have been reported (27–31). The role, if any, for Gpr40 in mediating secretion of ghrelin and CCK in response to FFAs will have to await future analyses.

In β-cells, IPF1/PDX1 regulates the expression of several genes that ultimately ensure proper GSIS and thus β-cell function (12–14,17). Relatively little is known about the regulation of Gpr40 expression in β-cells. A recent study suggests, however, that IPF1/PDX1 and the basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factor NeuroD/β2, which also is expressed in β-cells, bind to an enhancer element within the 5′-flanking region of Gpr40 (5). Here, we show in vivo that loss of Ipf1/Pdx1 in β-cells impairs Gpr40 expression, providing evidence not only that IPF1/PDX1 can bind to the Gpr40 5′-flanking region (5) but that IPF1/PDX1 is required for Gpr40 expression in β-cells. IPF1/PDX1 is expressed also in endocrine cells of the gastric pyloric antrum and duodenum (22,32). In Ipf1/Pdx1-null mutant mice, the expression profile of several gut hormones is changed; fewer gastrin+ but more serotonin+ cells were, for example, observed in the antrum of these mice (22). In this study, we show that the expression of Gpr40 in endocrine cells of the anterior gastrointestinal tract is lost in Ipf1/Pdx1−/− mice. Thus, like Ipf1/Pdx1, Gpr40 is expressed in both β-cells and endocrine cells of the anterior gastrointestinal tract, and Ipf1/Pdx1 function is essential for Gpr40 expression in both of these cell types. Taken together, these data suggest a conserved role for Ipf1/Pdx1 in cells that secrete hormones in response to food intake. However, IPF1/PDX1 is not expressed in the more distal part of the gastrointestinal tract, and Gpr40 expression at these sites is not affected in Ipf1/Pdx1-null mice. Thus, Gpr40 expression in posterior enteroendocrine cells is Ipf1/Pdx1 independent. However, the identity of transcription factors regulating Gpr40 expression in endocrine cells of the posterior gastrointestinal tract remains unknown.

Like other cells of the gastrointestinal epithelium, enteroendocrine cells undergo constant renewal involving stem cell division, differentiation, and cell death. Gpr40+ cells are more abundant in the gastric pyloric antrum and duodenum than in the more posterior ileum and colon. In the gastric pyloric antrum, Gpr40 is predominantly expressed in gastrin+ cells close to the crypts of pyloric pits. In the intestine, Gpr40 expression was evident in endocrine cells expressing ghrelin, GIP, GLP-1, CCK, PYY, substance P, serotonin, and secretin. Although virtually all Gpr40-expressing cells were hormone positive, only ∼20–55% of the individual hormone expressing cells also expressed Gpr40. Whether this reflects the maturation process of the cycling enteroendocrine cells, i.e., that Gpr40 is expressed only at a specific stage of differentiation or that only a subpopulation of the individual enteroendocrine cells expresses Gpr40, which in turn would indicate functional differences, remains an open question.

By virtue of its contribution to FFA-enhanced insulin secretion from β-cells, GPR40 is a link between obesity and type 2 diabetes. FFA stimulation of insulin secretion from β-cells is reduced in Gpr40 mutant mice, and these mice do not develop hyperinsulinemia on a high-fat diet (2). The expression of Gpr40 in GLP-1+ and GIP+ cells and the impaired secretion of these hormones in Gpr40-null mice in response to acute, oral fat diet leaves open the possibility that the difference in insulin levels in control and Gpr40-null mice on high-fat diet results from combined direct, i.e., β-cells, and indirect, i.e., incretin cells, effects of FFA on insulin secretion. The expression of Gpr40 in endocrine cells expressing hormones that control food intake is suggestive of a role for Gpr40 in the secretion of also these hormones. Increased knowledge of the role for Gpr40 in β-cells and endocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract may therefore be of great therapeutic relevance not only for obesity-associated diabetes but also for obesity itself but will have to await the generation of β-cell–and enteroendocrine cell–specific Gpr40 mutant mice.

Acknowledgments

H.E. has received grants from the Swedish Research Council, the European Union (Integrated Project EuroDia LSHM-CT-2006-518153 in the Framework Program 6 of the European Community), the Kempe Foundations, and the Swedish Diabetes Association.

We thank members of our laboratory for technical instructions, suggestions, and helpful discussions; Dr. Michael Walker for helpful discussions and valuable advice; and Drs. Kelly Loffler and Thomas Edlund for critical reading and helpful discussions.

Published ahead of print at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org on 2 June 2008.

P.S. and H.E. are joint senior authors of this work.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Itoh Y, Kawamata Y, Harada M, Kobayashi M, Fujii R, Fukusumi S, Ogi K, Hosoya M, Tanaka Y, Uejima H, Tanaka H, Maruyama M, Satoh R, Okubo S, Kizawa H, Komatsu H, Matsumura F, Noguchi Y, Shinohara T, Hinuma S, Fujisawa Y, Fujino M: Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40. Nature 422 :173 –176,2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steneberg P, Rubins N, Bartoov-Shifman R, Walker MD, Edlund H: The FFA receptor GPR40 links hyperinsulinemia, hepatic steatosis, and impaired glucose homeostasis in mouse. Cell Metab 1 :245 –258,2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro H, Shachar S, Sekler I, Hershfinkel M, Walker MD: Role of GPR40 in fatty acid action on the beta cell line INS-1E. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 335 :97 –104,2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latour MG, Alquier T, Oseid E, Tremblay C, Jetton TL, Luo J, Lin DC, Poitout V: GPR40 is necessary but not sufficient for fatty acid stimulation of insulin secretion in vivo. Diabetes 56 :1087 –1094,2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartoov-Shifman R, Ridner G, Bahar K, Rubins N, Walker MD: Regulation of the gene encoding GPR40, a fatty acid receptor expressed selectively in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem 282 :23561 –23571,2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Easom RA: Beta-granule transport and exocytosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 11 :253 –266,2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutter GA: Nutrient-secretion coupling in the pancreatic islet beta-cell: recent advances. Mol Aspects Med 22 :247 –284,2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnell S, Schaefer M, Schofl C: Free fatty acids increase cytosolic free calcium and stimulate insulin secretion from beta-cells through activation of GPR40. Mol Cell Endocrinol 263 :173 –180,2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirasawa A, Tsumaya K, Awaji T, Katsuma S, Adachi T, Yamada M, Sugimoto Y, Miyazaki S, Tsujimoto G: Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat Med 11 :90 –94,2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu ZL, Carroll C, Alfonso J, Gutierrez V, He H, Lucman A, Pedraza M, Mondala H, Gao H, Bagnol D, Chen R, Jones RM, Behan DP, Leonard J: A role for intestinal endocrine cell-expressed GPR119 in glycemic control by enhancing GLP-1 and GIP release. Endocrinology 149 :2038 –2047,2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briscoe CP, Tadayyon M, Andrews JL, Benson WG, Chambers JK, Eilert MM, Ellis C, Elshourbagy NA, Goetz AS, Minnick DT, Murdock PR, Sauls HR Jr, Shabon U, Spinage LD, Strum JC, Szekeres PG, Tan KB, Way JM, Ignar DM, Wilson S, Muir AI: The orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR40 is activated by medium and long chain fatty acids. J Biol Chem 278 :11303 –11311,2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahlgren U, Jonsson J, Jonsson L, Simu K, Edlund H: Beta-cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the beta-cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev 12 :1763 –1768,1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart AW, Baeza N, Apelqvist A, Edlund H: Attenuation of FGF signalling in mouse beta-cells leads to diabetes. Nature 408 :864 –868,2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Cao X, Li LX, Brubaker PL, Edlund H, Drucker DJ: β-Cell Pdx1 expression is essential for the glucoregulatory, proliferative, and cytoprotective actions of glucagon-like peptide-1. Diabetes 54 :482 –491,2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoffers DA, Ferrer J, Clarke WL, Habener JF: Early-onset type-II diabetes mellitus (MODY4) linked to IPF1. Nat Genet 17 :138 –139,1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonsson J, Carlsson L, Edlund T, Edlund H: Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature 371 :606 –609,1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohlsson H, Karlsson K, Edlund T: IPF1, a homeodomain-containing transactivator of the insulin gene. EMBO J 12 :4251 –4259,1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahren B, Simonsson E, Scheurink AJ, Mulder H, Myrsen U, Sundler F: Dissociated insulinotropic sensitivity to glucose and carbachol in high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance in C57BL/6J mice. Metabolism 46 :97 –106,1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holst JJ, Orskov C: Incretin hormones: an update. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 234 :75 –85,2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adachi T, Tanaka T, Takemoto K, Koshimizu TA, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G: Free fatty acids administered into the colon promote the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 and insulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 340 :332 –337,2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yip RG, Wolfe MM: GIP biology and fat metabolism. Life Sci 66 :91 –103,2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson LI, Madsen OD, Serup P, Jonsson J, Edlund H: Pancreatic-duodenal homeobox 1: role in gastric endocrine patterning. Mech Dev 60 :175 –184,1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacDonald PE, El-Kholy W, Riedel MJ, Salapatek AM, Light PE, Wheeler MB: The multiple actions of GLP-1 on the process of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 51 (Suppl. 3):S434 –S442,2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada Y, Miyawaki K, Tsukiyama K, Harada N, Yamada C, Seino Y: Pancreatic and extrapancreatic effects of gastric inhibitory polypeptide. Diabetes 55 (Suppl. 2):S86 –S91,2006 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feinle-Bisset C, Patterson M, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, Horowitz M: Fat digestion is required for suppression of ghrelin and stimulation of peptide YY and pancreatic polypeptide secretion by intraduodenal lipid. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 289 :E948 –E953,2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liddle RA, Goldfine ID, Rosen MS, Taplitz RA, Williams JA: Cholecystokinin bioactivity in human plasma: molecular forms, responses to feeding, and relationship to gallbladder contraction. J Clin Invest 75 :1144 –1152,1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broglio F, Arvat E, Benso A, Gottero C, Muccioli G, Papotti M, van der Lely AJ, Deghenghi R, Ghigo E: Ghrelin, a natural GH secretagogue produced by the stomach, induces hyperglycemia and reduces insulin secretion in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86 :5083 –5086,2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Date Y, Nakazato M, Hashiguchi S, Dezaki K, Mondal MS, Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Arima T, Matsuo H, Yada T, Matsukura S: Ghrelin is present in pancreatic α-cells of humans and rats and stimulates insulin secretion. Diabetes 51 :124 –129,2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee HM, Wang G, Englander EW, Kojima M, Greeley GH Jr: Ghrelin, a new gastrointestinal endocrine peptide that stimulates insulin secretion: enteric distribution, ontogeny, influence of endocrine, and dietary manipulations. Endocrinology 143 :185 –190,2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reimer MK, Pacini G, Ahren B: Dose-dependent inhibition by ghrelin of insulin secretion in the mouse. Endocrinology 144 :916 –921,2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dezaki K, Sone H, Koizumi M, Nakata M, Kakei M, Nagai H, Hosoda H, Kangawa K, Yada T: Blockade of pancreatic islet-derived ghrelin enhances insulin secretion to prevent high-fat diet–induced glucose intolerance. Diabetes 55 :3486 –3493,2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, Ray M, Stein RW, Magnuson MA, Hogan BL, Wright CV: PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development 122 :983 –995,1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]