Abstract

The present study predicts cigarette and alcohol use in adolescence from the development of children’s cognitions in the elementary years, beginning in the second through the fifth grade. Using Latent Growth Modeling, we examined a model using data from 712 participants in the Oregon Youth Substance Use Project, who were in the second through fifth grade at the first assessment and followed for six annual or semi-annual assessments over seven years. Growth in children’s prototypes and subjective norms in the elementary years (T1 through T4) were related to their substance use in adolescence (T6) through their willingness and intentions (T5) to smoke and drink. Across the sample, for both substances, the intercept and slope of prototypes were either indirectly related to use through willingness or directly related to use. Both the intercept and slope of subjective norms were indirectly related to use of both substances through both willingness and intentions, and directly related to cigarette use. Results suggest that elementary children have measurable cognitions regarding substance use, which develop during the elementary years, and predict use later in adolescence. These findings emphasize the need for prevention programs targeting changing children’s social images of substance users and encouraging more accurate perceptions of peers’ use.

Keywords: alcohol, smoking, children, adolescence, cognitions

As Steinberg & Morris (2001, p. 87) note, “Development during adolescence cannot be considered without understanding development prior to adolescence”. While researchers have long recognized the temporal relation between early risk factors in childhood, and subsequent adolescent behaviors, with few exceptions (e.g., Kellam, Ling, Merisca, Brown & Ialong, 1998; Kellam, Simon & Ensminger, 1983), studies have not systematically linked risk factors identified in childhood to use of substances in adolescence. Potential early predictors of adolescent substance use are the cognitions young children have about substance use and substance users. The present study is the first longitudinal study to assess children’s cognitions across the elementary years and to predict cigarette and alcohol use in adolescence from the development of these cognitions.

The prediction of adolescent alcohol and cigarette use is of public health concern for two reasons. First, there are the negative health effects associated with use of cigarettes and alcohol in adolescence (Burr, Anderson, Austin, Harkins, Kaur & Strachan, et al., 1999), which may not occur until adulthood (Brick, 2004; Brook, Brook, Zhang & Cohen, 2004). Second, early use of a substance in adolescence is related to substance abuse or dependence in adulthood (Chassin, Presson, Sherman & Edwards, 1990; Gruber, DiClemente, Anderson & Lodico, 1996). Hence, the identification of early risk factors associated with adolescent substance use is essential to prevent or postpone use in adolescence and improve the health of youth.

Two theories of health behavior that examine cognitive factors are prominent in the field. Within the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) and its extension, The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1988; 1991), attitudes and normative beliefs influence behavioral intentions to engage in a behavior, and intentions, in turn, predict subsequent behavior (Armitage & Conner, 2001). In both the TRA and TPB, intentions are the result of reasoning and planning, and are the only proximal antecedent of action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Attitudes are affective and instrumental evaluations of performing the behavior. As defined by Ajzen and Fishbein (1973), normative beliefs (prescriptive norms) are the belief about the likelihood that members of a given reference group expect the person to perform the behavior in question. To examine the influence of subjective norms on substance use among children and adolescents, descriptive rather than prescriptive norms have often been used. Descriptive norms are defined as the extent to which children and adolescents believe their peers have tried the behavior.

More recently, behavior has been conceptualized as the result of dual processes: one reasoned and planned (i.e., intentions) and the other less deliberate and more reactive. These processes have been brought together in the Prototype/Willingness (prototype) model of adolescent health behavior (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1995; Gibbons, Gerrard, & Lane, 2003; Gibbons, Gerrard, Blanton, & Russell, 1998). This model includes both the reasoned and planned path to behavior, through intentions, as outlined in the TRA and TPB, and a second less planful path to behavior through behavioral willingness. Willingness is reactive, rather than planful, and is defined as an openness to a risk opportunity. Although intentions and willingness are correlated, they uniquely predict behavior (Gerrard, Gibbons, Brody, Murray, & Wills, 2006; Gibbons et al., 1998; Gibbons, Gerrard, Lane, Wills, Brody, & Conger, 2004).

Another key concept in the Gibbons and Gerrard model is that of prototypes, i.e., social images of the typical individual who engages in a behavior. They are more narrow than the attitudes as defined in the Ajzen and Fishbein theories, but similar to the affective, evaluative component of attitudes. However, in contrast to TRA and TBP, the prototype model suggests that prototypes associated with risky behaviors are not goal states, and hence do not influence behavior through planful intentions (Gerrard, Gibbons, Reis-Bergan, Trudeau, Vande Lune & Buunk, 2002; Gibbons, et al., 2003), but rather through willingness to engage in risky behavior in risk-conducive circumstances. Thus, one of the tenets of the prototype model is that children and adolescents have images of what smokers and drinkers are like (Andrews & Peterson, 2006; Snortum, Kremer & Berger, 1987) and these images influence their subsequent willingness to engage in the behavior (Gerrard et al., 2002; Gerrard, et al., 2006; Gibbons et al., 2003). For example, if an individual perceives the type of person who smokes as exciting or cool, then they are more willing to smoke themselves. Although the prototype model (like the TRA and TPB) includes subjective norms as antecedents to behavior, this model suggests that the influence of subjective norms is mediated by willingness rather than intentions.

There is extensive empirical support for the roles of prototypes and subjective norms in the direct and indirect prediction of adolescent substance use. Gibbons, Gerrard and others have shown that adolescents with more favorable images of smokers report more willingness to smoke (Blanton, Gibbons, Gerrard, Conger, & Smith, 1997; Gerrard, Gibbons, Stock, Vande-Lune, & Cleveland, 2005) and favorable images of non-drinkers are associated with abstinence from alcohol (Gerrard, et al., 2002). A number of studies examining the influence of prototypes that have not included willingness in the model have shown that that social images influence intentions. For example, adolescents with more favorable images of smokers were more likely than those with less favorable images to intend to smoke (Andrews & Peterson, 2006; Chassin, Corty, Presson, et al., 1981; Spijkerman, van den Eijnden, Vitale & Engels, 2002). Perceived norms have been related to smoking (e.g., Gritz et al., 2003; Norman & Tedeschi, 1989; Simons-Norton, 2002) and intention to use alcohol and cigarettes (Hampson, Andrews, Barckley & Severson, 2006; Hampson, Andrews & Barckley, in press) and peer influence has been a consistent predictor of adolescent substance use (e.g., Chuang, Ennett, Bauman & Foshee, 2005; Urberg, Luo, Pilgrim & Degirmencioglu, 2003; Urberg, Degirmencioglu, & Pilgrim, 1997).

The purpose of the present study is to draw from these theoretical frameworks and to examine a model relating the development of children’s prototypes and subjective norms in the elementary years to their subsequent substance use in adolescence. Our previous work, and that of others, suggests that young children’s cognitions are reliable and valid predictors of intentions and behavior. Studies indicate that children as early as first grade recognize alcohol and cigarettes (Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, Duncan, and Severson, 2003) and by second grade have reliable prototypes (i.e., social images) of smokers and alcohol users (Andrews & Peterson, 2006). Second to eighth grade children’s prototypes and their subjective norms (i.e., beliefs about the prevalence of peers’ cigarette and alcohol use) are concurrently associated with intentions to use that substance when they are older (Hampson, Andrews, Barckley, & Severson, 2006; Hampson, Andrews, & Barckley, in press) and children’s social images of smokers in fifth grade predicted their cigarette use in seventh grade (Dinh, Sarason, Peterson, & Onstad; 1995).

Although cigarette and alcohol use are both considered problem behaviors (Jessor & Jessor, 1977) and hence are often combined into a single construct for the purpose of analyses, they also have unique etiological factors associated with each of them (e.g., Andrews, Hops, Ary, Tildesley, & Harris, 1993; Andrews, Hops & Duncan, 1997) and differ as to their prevalence and acceptability by society. Alcohol use is more normative than is cigarette use, and young children are more likely to try alcohol (Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, Duncan & Severson, 2003). Therefore, we tested separate models for cigarette and alcohol use.

Based on the prototype model, we hypothesized a dual process, that both intentions and willingness would independently predict behavior and that prototypes would be related to use through willingness, for both substances. Based on both the TRA and TPB, and the prototype model, we hypothesized that subjective norms would be related to use through both intentions and willingness to use alcohol. The lower prevalence of cigarette use among youth suggests restricted variability in subjective norms, particularly for the younger sample. Therefore, we hypothesized that only prototypes would be directly and indirectly related to cigarette use, particularly for the younger samples.

We tested these models on a community sample of young children participating in an ongoing longitudinal study, the Oregon Youth Substance Use Project (OYSUP; Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, Duncan, & Severson, 2003; Severson, Andrews, & Walker, 2003; Hampson et al, 2006; Andrews & Peterson, 2006)1. Model testing included an assessment of gender and grade differences. Popularity is particularly important for adolescent girls (Rutter, 1979) and this need for popularity may guide their ultimate behavior, suggesting that social images may be a stronger predictor of willingness for girls than boys. Although subjective norms are perceptions of peers’ use, they are considered a form of peer influence. While results of studies investigating gender differences on the effects of peer influence have been mixed, when gender differences were found, the effect was stronger for girls than boys (Billy & Udry, 1985; Berndt & Keefe, 1995; Duncan, Duncan & Hops, 1994; Kandel, 1978). Therefore, we hypothesized a stronger relation between for prototypes and subjective norms and subsequent willingness and intentions, and ultimate use, for girls than boys.

We also examined each model as a function of grade (age) by splitting the sample into younger and older groups, those who were in the 2nd and 3rd grade at the first assessment and those who were in 4th and 5th grade at the first assessment. In addition to differences in prevalence of substance use as a function of the grade of the child (Andrews, et al., 2003), children are more likely to intend to use substances, are more willing to use, and have more positive prototypes of substances users as they get older (Andrews & Peterson, 2006). According to Elkind (1967), as youths age they become more egocentric and are more likely to believe that they are central to other’s thoughts. Thus, we predict that the influence of prototypes of substance users on willingness will be stronger for the older group. In addition, since peer influence increases as the child ages (Steinberg & Silverburg, 1986), the influence of subjective norms on both willingness and intentions is expected to be stronger for the older group.

Method

Overview of Design

OYSUP is an ongoing cohort-sequential longitudinal project (Schaie, 1965; 1970) wherein five grade cohorts, defined by grade at T1, have been or will be assessed annually or semiannually across nine years, beginning when they are in the 1st through the 5th grade. This paper is based on data from the first six assessments, which spanned seven years, and from four grade cohorts, who were in the 2nd through 5th grade at the first assessment. At the sixth assessment, the sample was in the 8th through the 11th grade.

Participants

Of the 1075 T1 students for whom we obtained parental consent, 1070 children completed the first assessment. The remaining five students were absent on the assessment day. An average of 215 students per grade (1st through 5th) participated in the study at T1 with an even distribution by gender (50.3% female, N = 538). With minor exceptions, the children in the T1 sample were representative of elementary students in the district, specifically, and in Oregon, in general. (The reader is referred to Andrews, et al. 2003, for more details regarding the design of the study and the characteristics of the sample).

Since the measure of a key variable, prototypes, was not reliable for the first grade cohort, this cohort was eliminated from the analyses. We included data from those participants for whom we had data from both the T5 and T6 assessments, and at least one of the T1 through T4 assessments. Missing data for the T1 through T4 assessment was estimated using maximum likelihood procedures. The resulting sample size was 703 for the prediction of alcohol use and 712 for smoking.

At the time of the 1st assessment (T1), participants in this study were an average of 9.47 years old (SD = 1.15), 74.2% of mothers and 68.0% of fathers had more than a high school education and 5.8% of mothers and 10.0% of fathers had not graduated from high school and did not have a GED. The sample was primarily Caucasian (86.7%), with 6.2% Hispanic, .8% African-American, 2.2% Asian, 2.3% American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 1.6% other or of mixed race/ethnicity. Thirty-nine percent of the sample was eligible for a free or reduced lunch under Title 1, an indicator of low family income. This is comparable to the proportion of students eligible for free or reduced lunch in Oregon (40.8%) and across the United States (36%).

Attrition

Of the 848 second through fifth grade children who participated in the T1 assessment, 127 did not participate in both the T5 and T6 assessments (15% of the T1 participants). Children who participated in the study at T5 and T6 were similar to those in the T1 sample who did not participate on most demographic variables, including grade, gender, race/ethnicity, father’s education, and income (as measured by eligibility for free lunch). However, those who left the study had mothers who were less likely to graduate from high school than those who stayed in the study (16.3% versus 5.8%; X2 (2, n = 745) = 15.09, p < .001). Those who left the study were similar to those who stayed in the study on all hypothesized risk factors assessed at T1, including prototypes, subjective norms, and intentions.

Assessment Procedures

At T1, all consenting students were assessed at school during their class time on one of two assessment days. At T2 through T6, if children attended school in the study school district, they were assessed at school. If they lived outside of the district but within driving range of the Oregon Research Institute, they were assessed at the institute. If they did not live within driving range, second and third graders were not assessed, fourth through eighth graders were assessed via the telephone and ninth through eleventh graders completed mailed questionnaires.

The second and third grade assessment was an individual interactive structured interview. Therefore those who could not be assessed in person, did not complete the interview. This interview used a procedure similar to that used by Blinn-Pike, Tittsworth, Bell, Von Bargen, Devereaux, & Doyle (1993) and Jahoda & Cramond (1972), wherein children put pictures of each substance in one of three labeled boxes which represented their answers. For in-school assessments, fourth through eleventh grade children answered questions in group sessions using written questionnaires. In a separate study, we showed that responses did not vary as a function of the assessment method (interview vs. questionnaire; Andrews et al., 2003).

For fourth and fifth graders, a trained monitor read the questions aloud to the group and another monitor answered questions on an individual basis; for sixth through eleventh graders, children read the questions to themselves and trained monitors were available to answer questions. If children in the sixth through eleventh grade could not read the questionnaire to themselves, a monitor read it to them. At the institute, assessments were done either in groups or individually, depending on the circumstances of the participants. Items asked were similar across grades.

Measures

Second and third graders were shown a series of pictures depicting cigarettes and alcohol (wine, beer, hard liquor) and asked if they identified the item in each picture using the question, “Do you know what this is?” The child was scored as identifying the substance if they could name it or describe its effects. If the child indicated that they could not identify a specific drug, prototypes and subjective norms were not assessed, and were recorded as missing. At T1 3% of second and third graders could not identify cigarettes and 8% could not identify alcohol; At T2, 3% could not identify cigarettes and 6% could not identify alcohol.

Prototypes (social images)

Characteristics of substance users for the assessment of prototypes were selected from a list of attributes of smokers examined by Dinh and colleagues (1995) in a prospective study of fifth and seventh graders. Attributes selected for the present study were “exciting”, “cool or neat”, and “popular” (See Andrews & Peterson (2006), for more details regarding attribute selection). To assess prototypes, all children were asked if they thought that “kids who smoke cigarettes (drink alcohol)” were each of these attributes. A three-point response format was used for each question, with “Yes” coded as 2, “No” as 0, and “Maybe” as 1. The measure was created by averaging the three items. As shown in Andrews and Peterson (2006), the Guttman properties of these items were excellent, for all but 1st graders’ prototypes of alcohol users, implying a unidimensional scale, with children initially endorsing “popular”, followed by “popular” and “exciting” and finally “popular”, “exciting” and “cool or neat”.2 The three items were summed to measure prototypes for each substance. In earlier studies (Andrews & Peterson, 2006; Andrews et al., 2003) the intraclass correlation of these variables within school were examined and found to be small, ranging from .001 to .018, allowing us to collapse across school for these analyses.

Subjective norms

To assess peer-based descriptive norms, second and third graders were shown a picture of alcoholic beverages and a picture of cigarettes and asked “Do any kids in your neighborhood or at school (smoke; drink) this?” and “Do your friends ever (smoke, drink) this?” (“No” or “Don’t know” = 0, “Yes” = 1). Fourth through 8th graders were asked “How many of the kids at school or in the neighborhood have tried (a drink of alcohol (beer, wine, or hard liquor)/a cigarette)?”) (“None” = 0, “Some”, “Most” or “All” = 1), and “Do you have any friends who (drink alcohol/smoke cigarettes)?” (“Yes” = 1, “No” = 0). Responses were summed across the two items (second and third graders: r = .093 and .47, for cigarettes and alcohol respectively; fourth through eighth graders: r = .44 and .57, for cigarettes and alcohol, respectively. Hampson et al. (2006), examined the convergent and discriminate correlations among the two items assessing norms and the three items assessing prototypes and found that the items assessing the same construct were consistently higher (mean convergent r for prototype items = .40, mean convergent r for norm items = .34) than the correlations between items assessing divergent constructs (mean divergent r = .14).

Behavioral intentions

To assess intentions, all children were asked the following two items, “Do you think you would (smoke, drink alcohol, etc.) when you are an adult?” and “when you are (in high school, for middle school participants; out of high school, for high school participants)?”4 Responses to each items were “no” (coded as 0), “maybe” (coded as 1) and “yes” (coded as 2). At T5, the correlation between the two items was .84 for cigarettes, and .74 for alcohol.

Behavioral willingness

To assess willingness, children in the sixth through tenth grade at T5 were given the following scenario, “Suppose you were with one of your friends and one of them offered you a (cigarette/ drink of alcohol). How willing you would be to…”. Four items assessing willingness followed this statement. Items ranged from experimenting with the substance (e.g., “try a few puffs”) to more extensive use (e.g., “Smoke more than one cigarette” and “take one to smoke later”). Children indicated their willingness to engage in each behavior on a 5-point likert type scale, ranging from “very unwilling” (1) to “very willing” (5). At T5, internal consistency across the four items, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, for willingness was .84 for cigarettes and .86 for alcohol.

Use in the last 12 months

Use in the last 12 months was assessed with the following question, “During the last 12 months, how many times did you (drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes or cigars)?” The six response options ranged from never (0) to some each day (5). The stability of responses to this item between T5 and T6 was .69 for cigarettes and .67 for alcohol.

Overview of Analyses

We used the M-Plus program, version 3.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 1994) to test the fit of the model to the data. Development in both prototypes and subjective norms across the first four assessments was modeled using latent growth models (LGM). Within LGM, measures of variables across time (assessments) were used to estimate the intercept (initial level at T1) and the slope (rate of change over time). Within this program, missing data within the first four assessments were estimated using maximum likelihood. We first examined the fit of an associative growth model of the concurrent growth of prototypes and subjective norms over time. We then fit a model wherein the intercept and slope of prototypes and subjective norms were both directly related to substance use at T6 and indirectly related to substance use through intentions at T5 and willingness at T5. Non-significant paths were eliminated from the final model. Within the final model, the significance of the indirect paths was tested using the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982).

To test for gender differences in the cigarette and alcohol models, we used multiple sample analysis to evaluate the significance of the difference in fit of each parameter between the two models, one with the respective parameter fixed between genders and the other with the parameter freed. To test for grade differences in the cigarette and alcohol models, we used multiple sample analysis to compare the 2nd and 3rd graders at T1 with the 4th and 5th graders at T1.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Intentions, willingness and use

Intentions, willingness and use were less prevalent for cigarette use than for alcohol use. At T5, 20.1% expressed some intention to smoke cigarettes in the future (a score on the intention scale greater to or equal to 1.0) and 47.1% expressed some willingness to smoke cigarettes in the future (a score on the willingness scale greater than or equal to 1.0). At T5, 71% expressed some intention to drink alcohol in the future and 58.9% expressed some willingness. At T6, 24.1% reported smoking in the last year, with 13.5% reporting smoking at least some each month (5.3% report smoking daily). At T6, more than half (53.4%) reported drinking in the last year and 38.8% reporting drinking at least some each month.

Prototypes and subjective norms

The means and standard deviations of prototypes and subjective norms are shown in Table 1. For both substances, the means were consistently less than 1.0, for both measures, across assessments. Both prototypes and subjective norms increased over time. Across the entire sample, prototypes of alcohol users did not differ from prototypes of cigarette users across the first three assessments, but were significantly more favorable than those of cigarette users at the fourth assessment (p < .05). Subjective norms regarding cigarette use exceeded those of alcohol use in the first assessment (p < .05), but were less than those of alcohol use for the third and fourth assessment (p < .05).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Prototypes and Subjective Norms across Assessments

| Cigarettes | Alcohol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prototypes (Favorability) | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. |

| T1 | .39 | .78 | .41 | .82 |

| T2 | .38 | .74 | .40 | .85 |

| T3 | .47 | .88 | .45 | .89 |

| T4 | .52 | .95 | .61 | 1.14 |

| Subjective Norms | ||||

| T1 | .36 | .57 | .28 | .53 |

| T2 | .41 | .61 | .44 | .68 |

| T3 | .61 | .69 | .69 | .80 |

| T4 | .68 | .71 | .92 | .85 |

Gender differences

Using multiple sample analysis, we examined the intercepts and slopes of prototypes and subjective norms for each substance as a function of gender and found no differences. There were also no gender differences in willingness or intention to use any substance at T5. However, girls smoked more cigarettes in the last 12 months than boys at T6, t(710) = 2.53, p < .05, but use of alcohol did not vary by gender.

Prediction of Cigarette Use

Associative model of prototypes and subjective norms

An associative growth model of both prototypes and subjective norms fit the data well, X2 (21, n = 712) = 35.36, p = .03; CFI = .981, RMSEA = .031, 90% CI = .011, .018. The intercept and slope of both prototypes (intercept mean = .37, p < .001; slope mean = .045, p < .01) and subjective norms (intercept mean = .34, p < .001; slope mean = .115, p < .001) differed significantly from zero. Variances of these parameter estimates were all significant (p < .001, for all). As expected, the intercepts of prototypes and subjective norms were negatively correlated with their respective slopes (r = −.41, p < .01 and r = −.22, p < .05, respectively). Thus, less favorable initial prototypes and lower subjective norms were related to a faster increase in prototypes and norms, respectively, across assessments. The slope of prototypes was significantly correlated with the slope of subjective norms (r = .33, p < .01), suggesting an association between the rate of change in these two cognitions over time. Although the intercept of subjective norms was correlated with the slope of prototypes (r = .25, p < .05), the intercept of prototypes was not significantly correlated with either the intercept (r = .02) or the slope of subjective norms (r = −.12).

Full model

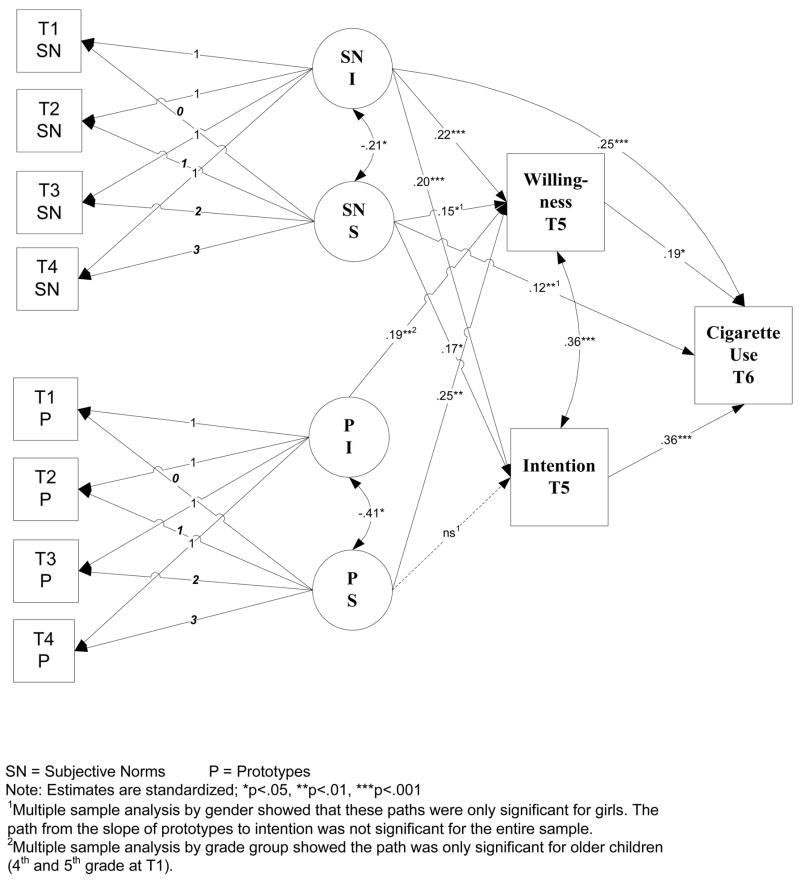

The model predicting cigarette use in the last 12 months at T6 from the development of prototypes and subjective norms through willingness and intentions fit the data well, X2 (36, n = 712) = 46.09, p = .12; CFI = .993, RMSEA = .020, 90% CI = .000, .035. As shown in Figure 1, the effect of the intercept and slope of prototypes on cigarette use at T6 was indirect, through willingness (intercept, Sobel test = 2.83, p < .01; slope, Sobel test = 2.63, p < .01). However, the intercept and slope of subjective norms were indirectly related to cigarette use through both willingness (intercept, Sobel test = 3.14, p < .01; slope, Sobel test = 2.19, p < .05) and intentions (intercept, Sobel test = 3.44, p < .001; slope, Sobel test = 2.48, p < .05). These variables were also directly related to use.

Figure 1.

The indirect and direct effects of initial level and growth of subjective norms and prototypes on smoking at T6. Estimates are for the entire sample.

Gender differences

Multiple sample analysis by gender showed differences on four parameter estimates, with stronger effects for girls than boys. These are summarized in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 1. The paths from the slope of subjective norms to willingness at T5 and to cigarette use at T6, and from the slope of prototypes to intentions at T5 were significant for girls but not boys. In addition, the path from intentions at T5 to cigarette smoking at T6 was significant for both genders, but stronger for girls.

Grade differences

Multiple sample analysis by grade showed differences on two parameter estimates with stronger effects for older youth than younger youth. First, the path from the intercept of prototypes to willingness at T5 was only significant for older participants, those who were in the 4th and 5th graders at T1. Second, the path from willingness at T5 and cigarette use at T6 was stronger for older than younger students, but significant for both.

Prediction of Alcohol Use

Associative model

An associative growth model of prototypes and subjective norms fit the data well, X2 (21, n = 703) = 54.38, p < .001; CFI = .967, RMSEA = .048, 90% CI = .032, .063. The intercept and slope of both prototypes (intercept mean = .80, p < .001; slope mean = .22, p < .001) and subjective norms (intercept mean = .79, p < .001; slope mean = 1.19, p < .001) differed significantly from zero. Variances of these parameter estimates were all significant (p < .001, for all). As expected, the intercept of prototypes was negatively correlated with the slope (r = −.36, p < .05), suggesting that those who have the less favorable initial prototypes, tend to increase the favorability of prototypes faster. However, the intercept of subjective norms was not significantly correlated with the slope (r = .20). The slope of prototypes was significantly correlated with the slope (r = .69, p < .011) of subjective norms, suggesting that these two cognitions are associated across time. However, the intercept of prototypes was not significantly correlated with the intercept of subjective norms (r = .03), but was significantly, and negatively, correlated with the slope of subjective norms (r = −.20, p < .01). The intercept of subjective norms was significantly correlated with the slope of prototypes (r = .31, p < .01).

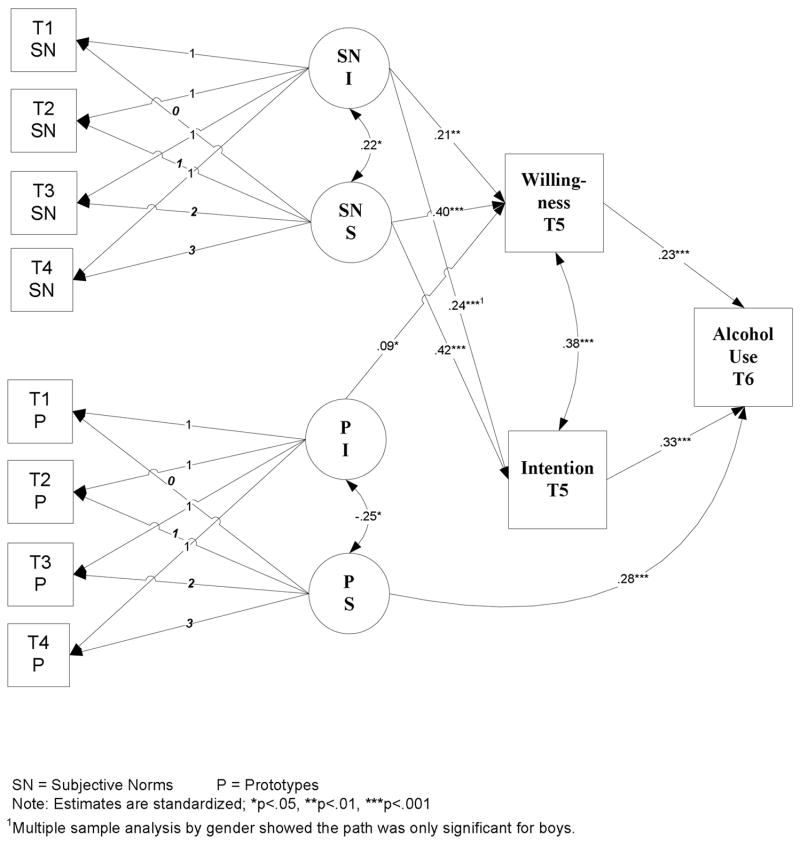

Full model

The model predicting alcohol use in the last 12 months at T6 from the development of prototypes and subjective norms through willingness and intentions fit the data well, X2 (39, n =703) = 64.14, p < .01; CFI = .987; RMSEA = .030, 90% CI = .016, .043. Similar to cigarettes, the intercept of prototypes was indirectly related to alcohol use through willingness (Sobel test = 1.97, p < .05); however, in contrast to cigarettes, the slope of prototypes was directly, rather than indirectly, related to alcohol use. Similar to cigarettes, the intercept and slope of subjective norms were indirectly related to alcohol use, through both willingness (intercept, Sobel test = 2.88, p < .01; slope, Sobel test = 4.18, p < .001) and intentions (intercept, Sobel test = 3.41, p < .001; slope, Sobel test = 4.97, p < .001). However, in contrast to cigarettes, there was not a direct effect of either the intercept or slope of subjective norms on alcohol use at T6.

Gender and grade differences

Multiple sample analysis by gender showed only one difference. The path between the intercept of subjective norms and intention to use alcohol at T5 was only significant for boys, but not for girls. Multiple sample analysis did not suggest grade differences in parameter estimates.

Discussion

The findings from this study support a dual process model, wherein risky behavior is influenced by two pathways, one that is reasoned and the other that is reactive (Reyna & Farley, 2006). Both cigarette and alcohol use in adolescence were influenced by both intention to engage in the behavior, and willingness to do so. In support of the Prototype/Willingness model (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1995; Gibbons, et al., 2003; Gibbons, et al., 1998), both the intercept and slope of prototypes (social images of substance users) predicted cigarette use through willingness to smoke, and the intercept of prototypes predicted alcohol use through willingness to drink alcohol. In support of both the cognitive theories of Ajzen and Fishbein and of Gibbons and Gerrard, both the intercept and slope of subjective norms, or perceptions of friends’ and classmates use, predicted use of both alcohol and cigarettes through both intentions and willingness.

Reflective of the acceptability of alcohol use versus cigarette use among adults in today’s society, a large proportion of adolescents intended to use alcohol when they were older, and relatively few intended to smoke cigarettes. In addition, more adolescents used alcohol than smoked cigarettes. More adolescents intended to use alcohol when older than were willing to do so. In contrast, fewer adolescents intended to smoke cigarettes than were willing to do so. These inconsistent results for alcohol versus cigarettes are most likely due to the time frame of willingness (now) versus intentions (later) and the perceived risk associated with using the substance. Smoking is considered a risky behavior by most adolescents and adolescents are willing to do riskier things than they intend to do (Gibbons, et al., 2003).

The results emphasize the importance of children’s cognitions about substance use throughout the elementary years in the prediction of substance use three years later, in adolescence. In general, both initial level, when they were in the 2nd through the 5th grade, and growth, until the 5th through 8th grade, of these cognitions either indirectly or directly predicted frequency of use of that substance. Children who initially had more favorable prototypes of kids their age who use cigarettes or alcohol and believed that more of their peers used the substance were more willing to use these substances, and subsequently used that substance more in adolescence. Children who initially believed that more of their peers smoked had greater intention to smoke in the future and subsequently used cigarettes more frequently in adolescence. This effect was replicated for boys in the prediction of alcohol use. Moreover, those children whose prototypes of cigarette users became increasing more favorable across the early years were more willing to smoke and subsequently used cigarettes more frequently in adolescence; and those children whose perceptions of the number of peers who use alcohol and cigarettes increased over the elementary years were more willing to use and more likely to intend to use in the future, and subsequently use the respective substance more frequently in adolescence.

For all children, for both cigarettes and alcohol, the intercept and slope of prototypes were directly related to the use of that substance or were indirectly related through willingness. The indirect effect of the initial level of prototypes on alcohol and cigarette use and the slope of prototypes on cigarette use through willingness supports Gibbon’s and Gerrard’s Prototype/Willingness model (Gibbons & Gerrard, 1997). Prototypes, or social images of other kids who use a substance, are evaluative and affect-laden (i.e., associated with good or bad qualities). According to Gibbons’ and Gerrard’s Prototype/Willingness model, willingness is more reactive than is intention, which is conceptualized by Ajzen and Fishbein (1973) as more planful. Similarly, according to Slovic (2001), the decision to engage in risky behavior such as substance use is based on two distinct cognitive systems, an experiential system, which is intuitive and automatic and the other that is deliberative and reason-based. The experiential system is based on imagery and affect. Our findings are consistent with these theoretical orientations. They suggest that more affect-laden cognitions (i.e., prototypes) are more highly related to teens’ acknowledgements of their willingness to engage in an activity than their more reasoned intentions to do so.

Subjective norms influenced both alcohol use and cigarette use through both a reasoned pathway, intentions, and a social reaction pathway, willingness. As noted earlier, subjective norms are the teen’s perceptions of their peers’ use of a substance, and most likely consist of a veridical report of actual peer use and an overestimate of actual peer use, but both social influence variables uniquely affect adolescent substance use (Graham, Marks & Hansen, 1991). Perhaps actual use impacts the more deliberative aspects of use (i.e., intentions) and overestimations are more affect laden, affecting willingness. Additional research is necessary using the framework proposed by Graham and colleagues (1991) which separates these two facets of subjective norms to investigate their unique relation to willingness and intentions.

The direct path from the slope of prototypes to alcohol use in a sample of this age who are in general inexperienced was surprising and is not easily explained. While others have found a direct path from prototypes to the behavior (Rivis & Sheeran, 2003), they did not include willingness in the model or studies were based on an older, more experienced sample. There is no clear reason why children’s social images of kids who use alcohol should influence alcohol use in adolescence directly, rather than indirectly through willingness.

Gender Differences

The paths of influence of both prototypes and subjective norms on cigarette use and of subjective norms on alcohol use varied by gender. However, for both genders, both prototypes and subjective norms ultimately predicted both alcohol and cigarette use. Based on previous research on gender differences in peer influence (e.g., Berndt & Keefe, 1995; Duncan, Duncan & Hops, 1994) we expected stronger relations between the initial level and growth of subjective norms and intentions and willingness for girls than boys. As expected, in contrast to boys, girls’ increase in perception across the elementary years of the number of peers who smoked was related to a higher intention to smoke in the future and more willingness to smoke. For girls, the effect of the slope of prototypes on cigarette use was through both willingness and intentions, whereas, for boys, the effect was only through willingness. Girls have a greater concern about rejection from friends (Berndt, 1982) and have a greater need to be popular (Rutter, 1979). These concerns may guide girls to be more planful as a result of their social images of smokers than boys, leading to intention, as well as willingness.

Since the frequency of girl’s cigarette use at T6 was greater than that of boys, the finding of more significant pathways to use is meaningful. All paths must be targeted in smoking prevention programs, with a particular emphasis on both the affective and reasoned pathways for girls.

Only one gender differences was found in the model predicting alcohol use, and this effect was in the opposite direction to that hypothesized. The initial level of perception of peer alcohol use was significantly related to intentions, only for boys. There is really no obvious explanation for this finding, which is not supported by previous research. The stronger effects for girls than boys found only for cigarette use could be due to the relative acceptability and prevalence of alcohol use as compared to cigarette use.

Grade Differences

Effects of grade were tested in both the cigarette and alcohol models. In contrast to predictions, for the most part, the final model was generalizable across all grade groups for both substances. This finding is particularly important suggesting that prototypes and subjective norms, with one exception, are as important for 2nd and 3rd graders as for older children. Analyses suggested only one grade difference in a parameter estimate, the effect of the initial favorability of prototypes at T1 on cigarette use was only significant for the older cohorts. This finding suggests implementing prevention programs for cigarette use in the later elementary years to 4th and 5th grade.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has both strengths and limitations. The strengths of this study include the large longitudinal data set, including measures of cognitions in the early elementary years, and the method of analysis, allowing for the prediction of substance use in adolescence from the initial level and growth of these early cognitions. However, although the sample is representative of students in the geographical region, findings are generalizeable to a limited proportion of adolescents: those who live in working class communities in the Western United States who are primarily Caucasian. Moreover, the analysis limits the potential of examining the interaction of gender and grade in the prediction of use. While it is possible to test for interaction effects using latent growth modeling (Li, Duncan & Acock, 2000), the models are exceedingly complex, requiring many additional parameter estimates. Hence, we limited our analyses to that of main effects. Further, data on peer use were collected only from the participant, limiting the ability to separate the unique variance of both perceived and actual use in the prediction of subsequent substance use.

Implications for Prevention

The findings in this paper have important implications for the design of prevention programs and the timing of these programs. They suggest that both prototypes and subjective norms are important targets for elementary school prevention programs designed to prevent or postpone cigarette and alcohol use. Thus these programs need to focus on reinforcing unfavorable prototypes among children to prevent them from becoming more favorable as they develop and on encouraging more accurate perceptions of peer use, since perception of peers’ use is often overestimated (Agostinelli & Grube, 2005; Graham et al., 1991). Other foci for programs are the reinforcement of low intentions, targeting elementary school children prior to the increase in intentions which occur in middle school, and an emphasis on parental monitoring targeting parents of middle school children. Parental monitoring can remove opportunities for substance use, if children are willing to engage in that behavior.

The finding that initial levels of both prototypes and subjective norms are related to subsequent cigarette and alcohol use suggests designing programs for elementary students, beginning as early as 2nd grade for alcohol use and 4th grade for cigarette use. Moreover, the finding that the slope or rate of growth of both prototypes and norms are related to subsequent cigarette and alcohol use suggests that annual booster sessions are needed to prevent the normative developmental increase of these cognitions.

Most prevention programs for children, are school-based, are designed for students in the seventh and eighth grade, and target social influence factors (c.f., Sussman, Dent, Burton, Stacy, & Flay, 1995). For example, Gerrard, Gibbons and colleagues have developed and tested an alcohol prevention program for early adolescents targeting prototypes (Gerrard, et al., 2006) and Sussman’s program (Sussman et al., 1995) targets subjective norms, as well as other social influence factors. More recently, Andrews and colleagues (Andrews, Gordon, Hampson, Christianson, Slovic & Severson, 2007) have developed a computer-based tobacco prevention program for fifth graders, with targeted components reinforcing children’s unfavorable prototypes of tobacco users and correcting perceptions of peer use. This program is engaging for elementary students and suggests the feasibility of using the computer as an instructional modality to deliver similar substance use prevention programs. Educational software is a common instructional tool for children as young as pre-school. Therefore, a computer-based substance use prevention program would be appropriate for children in early elementary school, as well as for children in the later grades.

Figure 2.

The indirect and direct effects of initial level and growth of subjective norms and prototypes on alcohol at T6.

Table 2.

Gender and Grade Group Differences in Standardized Path Coefficients

| Path | χ2 Difference Test | β | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette Use | |||

| Grouping Factor

|

|||

| Males | Females | ||

|

|

|||

| Slope of subjective norms to willingness | 7.112* | −.019 | .30*** |

| Slope of subjective norms to cigarette use | 3.916* | −.12 | .17** |

| Slope of Prototypes to Intentions | 6.452** | −.05 | .36** |

| Intentions to cigarette use use | 25.181** | .27*** | .47*** |

| Younger | Older | ||

|

|

|||

| Intercept of prototypes to willingness | 4.77*** | .06 | .32*** |

| Willingness to cigarette use | 7.47*** | .14** | .26*** |

|

| |||

| Alcohol Use | |||

| Males | Females | ||

|

|

|||

| Intercept of subjective norms to intentions | 8.25*** | .37*** | .10 |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant DA10767 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Martha Hardwick and Niraja Lorenz and the assessment staff, for helping with data collection, and Christine Lorenz for manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Previous papers using the OYSUP data set were based on data collected in earlier assessments. Since children were younger, and the prevalence of use was low, previous papers predicted intention. The focus of additional papers based on the data from this sample was on the evaluation of the psychometric properties of variables.

The coefficient of reproducibility (CR) which has a minimum acceptable value of .90, ranged from .92 to .1.00, across the 2nd through 8th grade and substances. The minimum marginal reproducibility (MMR), was lower than the CR, in all cases, meeting criteria for acceptability, and the coefficient of scalability, which interprets the difference between the CR and the MMR ranged from .60 to .96, meeting or exceeding the minimum of .60.

The relatively low coefficient for cigarettes was due to the low variability in these two items.

In the majority of studies, behavioral intentions and behavioral expectations are used interchangeably (Armitage & Conner, 2001). However, these two variables differ as to the time frame. Behavioral intentions typically refer to a more recent time frame than expectations (Warshaw & Davis, 1985). Since the measure in this study refers to several years in the future, behavioral expectations is a more accurate name for this variable, although it is not as widely used. Behavioral expectations generally have higher means, are more stable, are more internally consistent and are more predictive of behavior than are behavioral intentions (Gibbons, et al., 2004; Parker, Manstead, Stradling, Reason & Baxter, 1992).

Judy A. Andrews, Oregon Research Institute, Eugene, Oregon; Sarah E. Hampson, University of Surrey and Oregon Research Institute; Maureen Barckley, Oregon Research Institute; Meg Gerrard, Iowa State University; Frederick X. Gibbons, Iowa State University.

Contributor Information

Judy A. Andrews, Oregon Research Institute

Sarah E. Hampson, University of Surrey and Oregon Research Institute

Maureen Barckley, Oregon Research Institute.

Meg Gerrard, Iowa State University.

Frederick X. Gibbons, Iowa State University

References

- Agostinelli G, Grube J. Effects of presenting heavy drinking norms on adolescents’ prevalence estimates, evaluative judgments, and perceived standards. Prevention Science. 2005;6:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-3408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality and behavior. New York: Open University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitudinal and normative variables as predictors of specific behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973:41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA. Substance abuse in girls. In: Bell-Dolan D, Foster S, Mash E, editors. Handbook of Behavioral and Emotional Problems in Girls. New York: Kluwer Academic Press/Plenum Publishers; 2005. pp. 181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Gordon J, Hampson SE, Christiansen S, Severson HH, Slovic P. Click City: An intranet-based tobacco prevention program for 5thgrade students. Presented at the 13thAnnual meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; Austin. Feb, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Ary D, Tildesley E, Harris J. Parental influence on early adolescent substance use: Specific and nonspecific effects. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1993;13:285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Duncan SC. Adolescent modeling of parent substance use: The moderating effect of the relationship with the parent. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:259–270. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Tildesley E, Li F. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychology. 2002;21:349–357. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Peterson M. The development of social images of substance users in children: A Guttman unidimensional scaling approach. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2006;11(5):305 –321. doi: 10.1080/14659890500419774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Duncan SC, Severson HH. Elementary school age children's future intentions and use of substances. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(4):556–567. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. The features and effects of friendship in early adolescence. Child Development. 1982;53(6):1447–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Keefe K. Friends' influence on adolescents' adjustment to school. Child-Development. 1995;66(5):1312–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billy JO, Udry JR. The influence of male and female best friends on adolescent sexual behavior. Adolescence. 1985;20:21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton H, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Conger KJ, Smith GE. Role of family and peers in the development of prototypes associated with substance use. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Blinn-Pike LM, Tittsworth S, Bell T, Von Bargen J, Devereaux M, Doyle H. Assessing what high risk young children know about drugs: Verbal versus pictorial methods. Journal of Drug Education. 1993;23:151–169. doi: 10.2190/4WTP-1GNU-DF90-QUNM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brick J. Medical consequences of alcohol abuse. In: Brick J, editor. Handbook of the medical consequences of alcohol and drug abuse. New York: Haworth Press; 2004. pp. 7–47. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Zhang C, Cohen P. Tobacco use and health in young adulthood. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2004;165:310–323. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.165.3.310-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr ML, Anderson HR, Austin JB, Harkins LS, Kaur B, Strachan DP, et al. Respiratory symptoms and home environment in children: A national survey. Thorax. 1999;54:27–32. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin LA, Corty E, Presson CC, Olshavsky RW, Bensenberg M, Sherman SL. Predicting adolescents’ initiation to smoke cigarettes. Journal of Health and Social Behaviors. 1981;22:445–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Edwards DA. The natural history of cigarette smoking: Predicting young-adult outcomes from adolescent smoking patterns. Health Psychology. 1990;9(6):701–716. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YC, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Foshee VA. Neighborhood influences on adolescent cigarette and alcohol use: Mediating effects through parent and peer behavior. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:187–204. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RY, Brownell KD, Felix MRJ. Age and sex differences in health habits and beliefs of school children. Health Psychology. 1990;9(2):208–224. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh KT, Sarason IG, Peterson AV, Onstad LE. Children’s perceptions of smokers and nonsmokers: A longitudinal study. Health Psychology. 1995;14(1):32–30. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H. The effect of family cohesiveness and peer encouragement on the development of adolescent alcohol use: A cohort-sequential approach to the analysis of longitudinal data. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:588–599. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkind D. Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development. 1967;38(4):1025–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intentions, and behavior. New York: Wiley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Brody GH, Murry VM, Wills TA. A theory-based dual focus alcohol intervention for pre-adolescents: Social cognitions in The Strong African American Families Program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:185–195. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M, Trudeau L, Vande-Lune LS, Buunk B. Inhibitory effects of drinker and nondrinker prototypes on adolescent alcohol consumption. Health Psychology. 2002;2:601–609. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Stock ML, Vande-Lune LS, Cleveland MJ. Images of smokers and willingness to smoke among African American pre-adolescents: An application of the prototype/willingness model of adolescent health risk behavior to smoking initiation. Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:305–318. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Predicting young adults’ health-risk behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:505–517. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Health images and their effects on health behavior. In: Buunk BP, Gibbons FX, editors. Health, coping, and well-being: Perspectives from social comparison theory. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1997. pp. 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Blanton H, Russell DW. Reasoned action and social reaction: Willingness and intention as independent predictors of health risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1164–1181. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane DJ. A social reaction model of adolescent health risk. In: Suls JM, Wallston KA, editors. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane LS, Wills TA, Brody G, Conger RD. Context and cognitions: Environmental risk, social influence and adolescent substance use. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1048–1061. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Marks G, Hansen WB. Social influence processes affecting adolescent substance use. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1991;76:29 –298. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz ER, Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, Jones MM, Rosenblum C, Chang CC, Chamberlain RM, Taylor WC, Johnston D, de-Moor C. Predictors of susceptibility to smoking and ever smoking: A longitudinal study in a triethnic sample of adolescents. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2003;5:493–506. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000118568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber E, DiClemente RJ, Anderson MM, Lodico M. Early drinking onset and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in late adolescence. Preventive Medicine. 1996;25:293–300. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M, Severson HH. Personality predictors of the development of elementary-school children’s intentions to drink alcohol: The mediating effects of attitudes and subjective norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:288–297. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M. Predictors of the Development of Elementary-School Children=s Intentions to Smoke Cigarettes: Hostility, Prototypes, and Subjective Norms. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. doi: 10.1080/14622200701397908. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda G, Cramond J. Children and alcohol: A developmental study in Glasgow, Vol. 1. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. National survey results on drug use from the Monitoring the Future study 1975–1999: Vol. 1 Secondary Students. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Homophily, selection, and socialization in adolescent friendships. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84(2):427–436. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Ling X, Merisca R, Brown CH, Ialongo N. The effect of the level of aggression in the first grade classroom on the course and malleability of aggressive behavior into middle school. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:165–185. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Simon MB, Ensminger ME. Antecedents in first grade of teenage substance use and psychological well-being: A ten-year community-wide prospective study. In: Ricks DF, Dohrenwend BS, editors. Origins of Psychopathology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Duncan TE, Acock A. Modeling interaction effects in latent growth curve models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2000;7:497–533. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus Users Guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Norman NM, Tedeschi JT. Self-presentation, reasoned action, and adolescents; decisions to smoke cigarettes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1989;19:543–558. [Google Scholar]

- Parker D, Manstead ASR, Stradling SG, Reason JT, Baxter JS. Intention to commit driving violations: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1992;77:94 –101. [Google Scholar]

- Reyna VF, Farley F. Risk and rationality in adolescent decision making: Implications for theory, practice, and public policy. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2006;7:1–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivis A, Sheeran P. Social influences and the theory of planned behavior: Evidence for a direct relationship between prototypes and young people’s exercise behavior. Psychology and Health. 2003;18:567–583. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Maternal deprivation, 1972–1978: New findings, new concepts, new approaches. Child Development. 1979;50:283–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. A general model for the study of developmental problems. Psychological Bulletin. 1965;64:92–107. doi: 10.1037/h0022371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. A re-interpretation of age-related changes in cognitive structure and functioning. In: Goulet LR, Baltes PB, editors. Life-Span developmental psychology: Research and theory. San Diego: Academic Press; 1970. pp. 485–507. [Google Scholar]

- Severson HH, Andrews JA, Walker HM. Screening and early intervention for antisocial youth within school settings as a strategy for reducing substance use. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG. Prospective analysis of peer and parent influences on smoking initiation among early adolescents. Prevention Science. 2002;3(4):275–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1020876625045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P. Cigarette smoking: Rational actors or rational fools? In: Slovic P, editor. Smoking: Risk, perception, and policy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. pp. 97–124. [Google Scholar]

- Snortum JR, Kremer LK, Berger DE. Alcoholic beverage preferences as a public statement: Self concept and social image of college drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1987;48:243–251. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology 1982. Washington DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerman R, van den Eijnden RJJM, Vitale S, Engles RCME. Explaining adolescent’s smoking and drinking behavior: The concept of smoker and drinker prototypes in relation to variables of the theory of planned behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;20:1615–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent Development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:83–1001. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Silverburg S. The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence. Child Development. 1986;57:841–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW, Burton D, Stacy AW, Flay BR. Developing school-based tobacco use prevention and cessation programs. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:834–844. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Luo Q, Pilgrim C, Degirmencioglu SM. A two-stage model of peer influence in adolescent substance use: Individual and relationship-specific differences in susceptibility to influence. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28(7):1243–1256. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw PR, Davis FD. The accuracy of behavioral intention versus behavioral expectation for predicting behavioral goals. Journal of Psychology—Interdisciplinary and Applied. 1985;119:599–602. [Google Scholar]