Abstract

This communication presents a solid-state NMR 15N-13C polarization transfer scheme applicable at high B0 and high MAS frequencies, requiring moderate r.f. powers (~50 kHz 13C/15N) and mixing time (1–6 ms). The sequence, PAIN-CP, involves the abundant nearby protons in the heteronuclear recoupling dynamics, and provides a new tool for obtaining long distance 15N-13C contacts. It should be of major interest for biomolecular structural studies.

Polarization transfer1–15 between different nuclear species mediated by dipolar couplings is used extensively in magic angle spinning (MAS)16 experiments to perform chemical shift assignments, and to measure distances5–7, 11, 17–21 and torsion angles.22–25 Heteronuclear dipolar recoupling sequences can be classified into two categories depending on their behavior with respect to dipolar truncation. The first group includes the double CP sequence (DCP26) and its variants (SPICP27, RFDRCP4, iDCP9) which lead to non-commuting terms in the effective Hamiltonian, and thus are mainly used to perform one-bond transfers (NCO, NCA) sometimes followed by a homonuclear 13C-13C recoupling period for obtaining 15N-13C multiple-bond contacts.28, 29 The second group of sequences (REDOR5, TEDOR1/REPT19, GATE17) yields a longitudinal effective Hamiltonian and enables measurement of long distances (< 4 Å).20, 21

High magnetic fields (>600 MHz) are an important experimental component for improving sensitivity and resolution in biomolecular MAS experiments involving 15N-13C magnetization transfer, provided that experiments can be performed at high MAS frequencies (>15 kHz) to compensate for increases in chemical shift anisotropies (CSA). Unfortunately, the application of the sequences mentioned above becomes problematic in this regime as the applied high r.f. powers lead to increased sample heating, jeopardize the integrity of the probe, but often do not provide sufficient 1H decoupling.

Here we present an efficient 15N-13C heteronuclear recoupling technique that involves nearby protons in the transfer and is applicable at high MAS frequency (ωr/2π>20 kHz). This new scheme, Proton Assisted Insensitive Nuclei Cross Polarization (PAIN-CP), reduces dipolar truncation and therefore is particularly well suited for obtaining long distance contacts. PAIN-CP demonstrates that the involvement of protons in the polarization transfer between low-γ nuclei does not have to be deleterious in nature; on the contrary 1H’s can be used to enhance the rate and efficiency of the transfer. The PAIN-CP experiment utilizes a mechanism which we refer to as Third Spin Assisted Recoupling (TSAR). Its extension to the homonuclear case is straightforward and will be discussed elsewhere. Note that the use of 1H irradiation has been reported previously for 13C-13C recoupling experiments,30–32 but that the underlying mechanism is different.

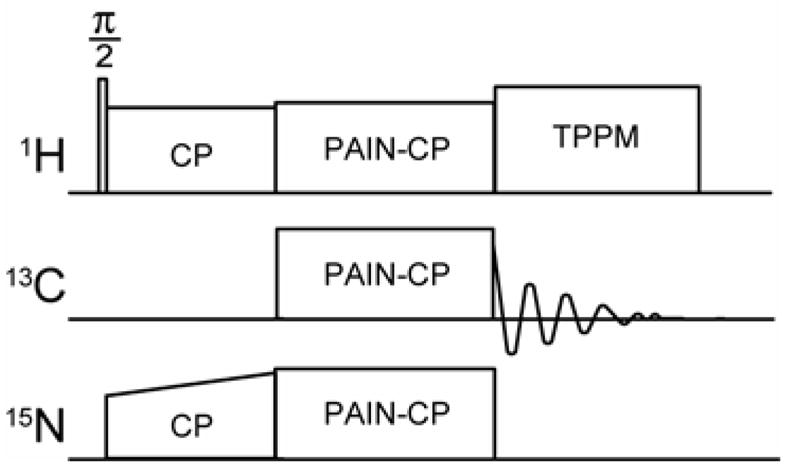

Even though PAIN-CP and DCP26 have similar pulse sequences (see Figure 1 and Supporting Information Section 7–8 (S.I.-7, 8)), they rely on very different mechanisms. The PAIN-CP mechanism corresponds to a second order recoupling in an interaction frame defined by the three C.W. r.f. fields involving cross terms between heteronuclear N-H and C-H dipolar couplings (see S.I.-2). In this process, nearby 1H’s are used to create trilinear (N, C, H) terms in the effective Hamiltonian that can lead to ZQ and DQ 15N-13C polarization transfer. In this publication we explore only the ZQ transfer.

Figure 1.

PAIN-CP 15N-13C correlation pulse sequence. The proper combination of 15N, 13C and 1H r.f. power results in enhanced rates and efficiency of 1H mediated 15N-13C polarization transfer.

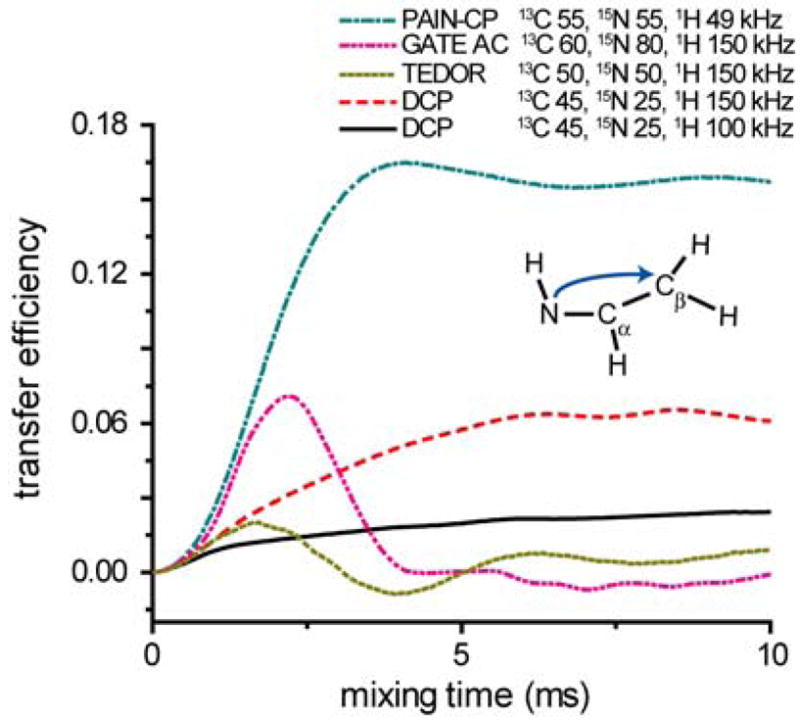

Figure 2 shows simulations comparing 15N-13C polarization transfer for the PAIN-CP, DCP, TEDOR and GATE sequences at ω1H/2π=750 MHz and ωr/2π=20 kHz. The model spin system consists of seven spins (15N, 13Cα, 13Cβ, 4 1H’s). Simulations were performed with SPINEVOLUTION33 (see S.I.-1 for details).

Figure 2.

Comparison of 15N-13C two-bond polarization transfer for PAIN-CP, DCP, TEDOR, GATE AC sequences at ωr/2π=20 kHz. Note that variants of DCP such as RFDRCP, SPICP, and iDCP are not considered here as they mainly improve the recoupling bandwidth, which is not the major concern in this simulation.

DCP simulations utilized typical r.f. field strengths -- (ω1C/2π)=45 kHz, (ω1N/2π)=25 kHz, (ω1H/2π)=100 and 150 kHz of 1H C.W. decoupling respectively, illustrating that r.f. power levels should satisfy the condition (ω1H/ω1C)≥3 to ensure correct 1H decoupling.34 However, even for 150 kHz of 1H decoupling, a challenge for most triple resonance probes, the two-bond transfer from 15N to Cβ reaches only about 6.5% efficiency in 6.5 ms, a result of the dipolar truncation effect (see S.I.-4). Longitudinal recoupling sequences such as TEDOR or GATE, where there is no dipolar truncation, do not provide efficient two-bond transfer in the presence of strong one-bond coupling. For example, GATE reaches about 7% transfer in 2.3 ms for extremely demanding experimental settings. On the other hand, the PAIN-CP buildup obtained with a 13C and 15N fields set to the same value (n=0 Hartmann-Hahn)35, 36 reaches 16.5% transfer efficiency in 4 ms, an improvement of 3 to 8 times when compared to DCP with high power 1H decoupling. In addition, contrary to TEDOR and GATE results, the transferred magnetization achieves an equilibrium value simplifying the choice of the mixing time in a correlation experiment.

In practice, it is possible to utilize the PAIN-CP mechanism provided that 1H-15N and 1H-13C Hartmann-Hahn (H.H.) as well as rotary resonance3 (R.R.) conditions are avoided. The 15N and 13C r.f. fields do not necessarily have to match n=0 H.H. condition (see S.I.-2, 6). Optimal PAIN-CP settings are a compromise between avoiding destructive H.H. or R.R. recoupling conditions and retaining significant second order scaling to ensure efficient polarization transfer. Accordingly, there are usually a few different 1H r.f. levels that lead to an appreciable PAIN-CP effect (see S.I.-6).

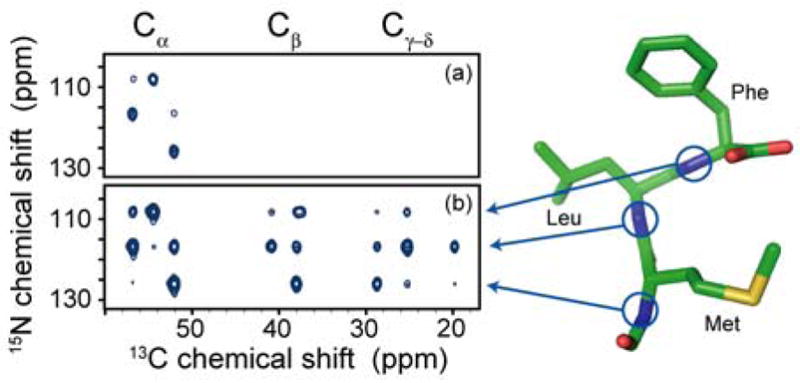

Figure 3 is an experimental demonstration that PAIN-CP is an efficient technique for heteronuclear 15N-13C correlation experiments. The spectra were obtained with [U-13C, 15N] N-f-MLF-OH using ωr/2π=20 kHz, ω1H/2π= 750 MHz, and a 2.5 mm, triple-channel Bruker probe. Figure 3(a) shows a NCA DCP spectrum with 3 ms mixing (optimum for one-bond transfer) and 112 kHz 1H decoupling. Long range cross peaks (more than 2 bonds) are completely absent from the spectrum at this mixing time and do not appear at longer mixing times (data not shown). Figure 3(b) depicts an n=0 H.H. PAIN-CP spectrum with 4 ms mixing, using r.f. fields of ~50 kHz for 13C, 15N and (a) 112 kHz and (b) 62 kHz respectively for 1H. We observe cross peaks for 15N-13C pairs separated by up to 6 Å in a uniformly 13C, 15N labeled compound. Note that part of the long range transfer also involves a 13C homonuclear TSAR effect (see S.I.-2). In addition, in spite of distributing the initial 15N magnetization over a larger number of 13C sites, the one-bond cross peaks are much more intense than in the DCP case. This fact indicates that for this system a ~2.5 ratio for (ω1H/ω13C,15N) is not sufficient to provide efficient 1H decoupling in the DCP case.

Figure 3.

Aliphatic region of 2D 15N-13C correlation spectra obtained at 750 MHz with 20 kHz MAS: (a) DCP with 3 ms mixing, (b) PAIN-CP with 4 ms mixing. The 1H r.f. field strength was 112 and 62 kHz for (a) and (b) respectively. In (a) the n=1 ZQ Hartmann-Hahn condition was matched with 45 kHz 13C r.f. and 25 kHz 15N r.f.. In (b) ω1/2π = 50 kHz for both 13C and 15N. All spectra were acquired and processed in exactly the same manner. The contour levels are set to the same value.

In summary, we present a new heteronuclear 15N-13C correlation mechanism, applicable at high ωr/2π, leading, in this regime, to superior recoupling performance compared to alternative techniques. PAIN-CP can provide long 15N-13C contacts, circumventing the usual dipolar truncation encountered with DCP-type sequences. The method provides a highly efficient alternative to NCX and NCXCY experiments, extends the range of applicability of heteronuclear recoupling techniques to high B0 and ωr/2π, and should thus be of major interest for structure determination of biomolecules.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information Available: Experimental and simulation details. Discussion of PAIN-CP mechanism with additional SPINEVOLUTION simulations. Quantitative comparison between DCP and PAIN-CP. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EB-001960 and EB-002026. We would like to thank Dr Patrick van der Wel for stimulating discussions and to the reviewers for their constructive comments.

References

- 1.Hing AW, Vega S, Schaefer J. J Magn Reson. 1992;96(1):205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldus M, Petkova AT, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. Mol Phys. 1998;95(6):1197–1207. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oas TG, Griffin RG, Levitt MH. J Chem Phys. 1988;89(2):692–695. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun BQ, Costa PR, Griffin RG. J Magn Reson A. 1995;112(2):191–198. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gullion T, Schaefer J. J Magn Reson. 1989;81(1):196–200. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao X, Hoffbauer W, auf der Gunne JS, Levitt MH. Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 2004;26(2):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Rossum BJ, de Groot CP, Ladizhansky V, Vega S, de Groot HJM. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122(14):3465–3472. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ladizhansky V, Vinogradov E, van Rossum BJ, de Groot HJM, Vega S. J Chem Phys. 2003;118(12):5547–5557. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjerring M, Nielsen NC. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;382(5–6):671–678. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dvinskikh S, Chizhik V. J Exp Theor Phys. 2006;102(1):91–101. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertani P, Raya K, Hirschinger K. Comptes Rendus Chimie. 2004;7(3–4):363–369. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray S, Ladizhansky V, Vega S. J Magn Reson. 1998;135(2):427–434. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan JCC. Chem Phys Lett. 2001;335(3–4):289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pines A, Gibby MG, Waugh JS. J Chem Phys. 1973;59(2):569–590. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldus M, Geurts DG, Hediger S, Meier BH. J Magn Reson A. 1996;118(1):140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowe IJ. Phys Rev Lett. 1959;2:285. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bjerring M, Rasmussen JT, Krogshave RS, Nielsen NC. J Chem Phys. 2003;119(17):8916–8926. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hing AW, Vega S, Schaefer J. J Magn Reson A. 1993;103(2):151–162. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saalwachter K, Graf R, Spiess HW. J Magn Reson. 2001;148(2):398–418. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaroniec CP, Filip C, Griffin RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124(36):10728–10742. doi: 10.1021/ja026385y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaroniec CP, Tounge BA, Rienstra CM, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121(43):10237–10238. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong M, Gross JD, Hu W, Griffin RG. J Magn Reson. 1998;135(1):169–177. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong M, Gross JD, Rienstra CM, Griffin RG, Kumashiro KK, Schmidt-Rohr K. J Magn Reson. 1997;129(1):85–92. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong M, Gross JD, Griffin RG. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101(30):5869–5874. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sack I, Balazs YS, Rahimipour S, Vega S. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122(49):12263–12269. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer J, Mckay RA, Stejskal EO. J Magn Reson. 1979;34(2):443–447. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu XL, Zilm KW. J Magn Reson A. 1993;104(2):154–165. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pauli J, Baldus M, van Rossum B, de Groot H, Oschkinat H. Chembiochem. 2001;2(4):272–281. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010401)2:4<272::AID-CBIC272>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egorova-Zachernyuk TA, Hollander J, Fraser N, Gast P, Hoff AJ, Cogdell R, de Groot HJM, Baldus M. J Biomol Nmr. 2001;19(3):243–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1011235417465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morcombe CR, Gaponenko V, Byrd RA, Zilm KW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(23):7196–7197. doi: 10.1021/ja047919t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takegoshi K, Nakamura S, Terao T. 2001;344(5–6):631–637. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takegoshi K, Nakamura S, Terao T. J Chem Phys. 2003;118(5):2325–2341. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veshtort M, Griffin RG. J Magn Reson. 2006;178(2):248–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishii Y, Ashida J, Terao T. Chem Phys Lett. 1995;246(4–5):439–445. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartmann SR, Hahn EL. Phys Rev. 1962;128(5):2042–2053. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stejskal EO, Schaefer J, Waugh JS. J Magn Reson. 1977;28(1):105–112. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Available: Experimental and simulation details. Discussion of PAIN-CP mechanism with additional SPINEVOLUTION simulations. Quantitative comparison between DCP and PAIN-CP. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.