Abstract

The regulation of M-type (KCNQ [Kv7]) K+ channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) has perhaps the best correspondence to physiological signaling, but the site of action and structural motif of PIP2 on these channels have not been established. Using single-channel recordings of chimeras of Kv7.3 and 7.4 channels with highly differential PIP2 sensitivities, we localized a carboxy-terminal inter-helix linker as the primary site of PIP2 action. Point mutants within this linker in Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 identified a conserved cluster of basic residues that interact with the lipid using electrostatic and hydrogen bonds. Homology modeling of this putative PIP2-binding linker in Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 using the solved structure of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 channels as templates predicts a structure of Kv7.2 and 7.3 very similar to the Kir channels, and to the seven-β-sheet barrel motif common to other PIP2-binding domains. Phosphoinositide-docking simulations predict affinities and interaction energies in accord with the experimental data, and furthermore indicate that the precise identity of residues in the interacting pocket alter channel–PIP2 interactions not only by altering electrostatic energies, but also by allosterically shifting the structure of the lipid-binding surface. The results are likely to shed light on the general structural mechanisms of phosphoinositide regulation of ion channels.

INTRODUCTION

Members of the KCNQ (Kv7) family of voltage-gated K+ channels underlie “M-type” K+ currents in many different types of neurons, delayed-rectifier currents of the heart, and K+ transport channels of the inner ear and epithelia (Jentsch, 2000; Robbins, 2001). Neuronal M currents play strong roles in regulating excitability and neuronal discharge, and their modulation by several receptors linked to the Gq/11 class of G proteins endows them with powerful effects on the function of excitable cells (Delmas and Brown, 2005). As for a plethora of other channels and transporters (Gamper and Shapiro, 2007), M-type channels are very sensitive to the abundance of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) in the membrane, and PIP2 depletion is widely accepted as the mechanism of M current suppression by muscarinic receptor stimulation in sympathetic neurons (Delmas and Brown, 2005; Suh et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2007; Suh and Hille, 2007).

We have examined the activity of Kv7.2–7.4 channels at the single-channel level and found these voltage-gated channels to have strikingly differential saturating open probabilities (Po) in cell-attached patches (Li et al., 2004). In accord with the role of PIP2 in regulating gating, channel activity rapidly runs down upon excision as inside-out patches, but activity can be fully restored by adding PIP2 or an analogue to the cytoplasmically facing bath solution (Zhang et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005). For all the channels studied, the Po is a function of the concentration of supplied PIP2, but with very different apparent affinities among the channels. Thus, Kv7.3 homomultimers display a very high apparent affinity, Kv7.2 and Kv7.4 homomultimers display apparent affinities some one to two orders of magnitude lower, and Kv7.2/7.3 heteromultimers display an intermediate value, as expected for channels composed of both high- and low-affinity PIP2-binding subunits (Li et al., 2005). Such differential PIP2 affinities among the channels are also supported by whole cell experiments in which PIP2 abundance was either tonically (Li et al., 2005) or suddenly (Suh et al., 2006) increased by expression/activation of PI(4)P 5-kinase.

Much work has investigated the locations of presumed PIP2-binding sites to channels and transporters, and the characteristics of their motifs. In contrast with the more specific binding sites typical of phosphoinositide binding to PH, ENTH, etc., motifs, those of PIP2-regulated ion channels have been generally only described by clusters of basic residues with positively charged side chains, usually interspersed with hydrophobic and/or aromatic residues (Lemmon, 2003; Gamper and Shapiro, 2007; Rosenhouse-Dantsker and Logothetis, 2007). Almost all such sites are on the N or C termini of the channels, where residues might be expected to localize near the inner leaflet of the membrane (Logothetis et al., 2007; Rosenhouse-Dantsker and Logothetis, 2007). For Kv7 channels, there is evidence for PIP2 interactions within the C termini. They include a decrease in the apparent affinity for PIP2 by the H328C mutation just after S6 in Kv7.2 (Zhang et al., 2003) and by the R539W and R555C long-QT mutations in the C terminus of Kv7.1 (Park et al., 2005). Thus, we focused on the carboxy termini of the channels in our elucidation of the site of PIP2 on the channels. In this paper, we examine the apparent affinities for PIP2 of pairs of chimeras between Kv7.3 and Kv7.4 at the single-channel and whole cell levels. We further evaluate the effects of charge reversals, neutralizations or residue swaps in an identified inter-helical linker region in Kv7.2 and 7.3, and identify a cluster of basic residues critical for PIP2 interactions. Finally, homology modeling is performed using crystal structures of Kir channels as templates to construct a model for PIP2 interactions with M-type channels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA Constructs

Plasmids encoding human Kv7.2, rat Kv7.3, and human Kv7.4 (GenBank accession nos. AF110020, AF091247, and AF105202, respectively) were provided by D. McKinnon (State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY; Kv7.2 and Kv7.3) and T. Jentsch (Zentrum für Molekulare Neurobiologie, Hamburg, Germany; Kv7.4). Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 were subcloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) as described previously (Shapiro et al., 2000). Kv7.4 was subcloned into pcDNA3.1zeo+ (Invitrogen) using XhoI/HindIII. Mouse-type 1α PI(4)P5-kinase (PI(4)5-kinase) was provided by L. Pott (Ruhr-University, Bochum, Germany) (Bender et al., 2002). Mutations were made by PCR using the QuikChange method (Stratagene) and verified by sequencing.

Cell Culture and Transfections

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were used for electrophysiological analysis as described (Gamper et al., 2005). Cells were grown in 100-mm tissue culture dishes (Falcon; Becton Dickinson) in DMEM with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 0.1% penicillin and streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37°C (5% CO2) and passaged every 3–4 d. Cells were discarded after ∼30 passages. For transfection, cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine–coated coverslip chips and transfected 24 h later with Polyfect reagent (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For electrophysiological experiments, cells were used 48–96 h after transfection. As a marker for successfully transfected cells, cDNA encoding green fluorescent protein was cotransfected together with the cDNAs coding for the channel subunits.

Cell-attached/Inside-Out Patch/Single-Channel Electrophysiology

The methods of recording and analysis were similar to those used previously for studying unitary Kv7 channels (Li et al., 2004). Channel activity was recorded 48–72 h after transfection in the cell-attached configuration. Pipettes had resistances of 7–15 MΩ when filled with a solution of the following composition (mM): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, with NaOH. Cells were bath-perfused with a solution of the following composition (mM): 175 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, with KOH. In inside-out configuration, the patch was perfused with a solution of the following composition (mM): 175 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, with KOH. The resting membrane voltage was assumed to be 0 mV. Currents were recorded using an Axopatch 1-D amplifier (MDS Analytical Technologies), sampled at 5 kHz, and filtered at 200–500 Hz (Kv7.4) or at 0.5–1 kHz (all others). The short-chain water-soluble PIP2 analogue diC8-PIP2 (Echelon Biosciences) was dissolved in an aqueous stock solution at 10 mM and sonicated immediately before each use.

Single-channel data were analyzed using PulseFit and TAC (Bruxton) software. Open and closed events were analyzed by using the “50% threshold criterion.” All events were carefully checked visually before being accepted. Po histograms were generated using TACFit (Bruxton). The presence of only one channel in a patch was assumed if Po was >0.25 for >1 min without superimposed openings, especially at strongly depolarized potentials where Po is highest. At a given potential, the single-channel amplitude (i) was calculated by fitting all-point histograms with single or multi-Gaussian curves. The difference between the fitted “closed” and “open” peaks was taken as i. When superimposed openings were observed, the number of channels in the patch was estimated from the maximal number of superimposed openings. The apparent NPo was estimated as:

|

where tj is the time spent at each current level corresponding to j = 0, 1, 2…N; T is the duration of the recording and N is the number of current levels (minimum number of active channels).

Dose–response curves of channel Po versus [diC8-PIP2] were fit using GraphPad Prism version 5.01 for Windows (GraphPad Software) by a Hill equation of the form:

|

where Po,max was set to one, x is [diC8-PIP2], xhalf is the [diC8-PIP2] at which Po = 0.5, and n is the Hill coefficient.

Perforated-Patch Electrophysiology

Perforated-patch experiments were performed as described previously (Gamper et al., 2003). To evaluate the amplitude of macroscopic Kv7 currents, CHO cells were held at 0 mV, and 800-ms hyperpolarizing steps to −60 mV, followed by 1-s pulses back to 0 mV, were applied. The amplitude of the current was usually defined as the difference between the holding current at 0 mV and the current at the beginning (after any capacity current as subsided) of the 1-s pulse back to 0 mV. In some cells, a more precise measurement was the XE991- or linopirdine-sensitive current at the holding potential of 0 mV. CHO cells have negligible endogenous macroscopic K+ currents under our experimental conditions, and 50 μM XE991 or linopirdine completely blocked the K+ current in Kv7-transfected CHO cells, but had no effect on currents in nontransfected cells (Gamper et al., 2005). All results are reported as mean ± SEM.

Homology Modeling and GPMI-P2 Docking

Three-dimensional models of the Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 C terminus tails were generated using the crystal structure of cytoplasmic domains of IRK1 (Kir2.1) and GIRK1 (Kir3.1) channels (Pegan et al., 2005) as templates (Protein Database accession nos. 1u4f and 1u4e, respectively) using the program SWISS-MODEL (Schwede et al., 2003). The initial sequence alignments between wild-type (wt) Kv7.2 and Kir2.1 and wt Kv7.3 and Kir3.1 were generated with full-length multiple alignments using ClustalW. The alignment of a 57-residue core (residues 428–484) of our putative PIP2-binding domain of Kv7.2 with residues 186–245 of Kir2.1 was submitted for automated comparative protein modeling implemented in the program suite incorporated in SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/SWISS-MODEL.html) using the Kv7.2 sequence as a target protein and the Kir2.1 sequence as a template structure. The alignment of a 54-residue core (residues 398–451) of our putative PIP2-binding domain of Kv7.3 with residues 185–238 of Kir3.1 was submitted using the Kv7.3 sequence as a target protein and the Kir3.1 sequence as a template structure. The carbon α root mean squared (CαRMS) between the Kv7.2 structural model and the template (Kir2.1) was 0.55 Å for 57 carbon atoms of the aligned amino acids (0.67 Å for 228 backbone atoms), and between the Kv7.3 structural model and the template (Kir3.1), it was 0.49 Å for 54 carbon atoms of the aligned amino acids (0.50 Å for 216 backbone atoms). Mutant structural models were individually made by selecting the mutations desired using the program DeepView, the Swiss-PdbViewer, and the structural models of the mutants generated using SWISS-MODEL as an iterative process. The CαRMS differences between the wt Kv7.2 structural homology model and those of Kv7.2 (KRR-EEE), Kv7.2 (R463Q), Kv7.2 (R463E), Kv7.2 (R467Q), and Kv7.2 (R467E) were 2.26, 1.96, 2.20, 1.69, and 2.19 Å, respectively; between the wt Kv7.3 structural homology model and Kv7.3 (KKR-EEE), it was 1.34 Å.

The homology models of wt Kv7.2, Kv7.2 (KRR-EEE), Kv7.2 (R463E), Kv7.2 (R463Q), Kv7.2(R467E), Kv7.2 (R467Q), wt Kv7.3, and Kv7.3 (KKR-EEE) were used to dock l-α-glycero-phospho-d-myo-inositol 4,5-bisphosphate (GPMI-P2), an analogue of the head group of PI(4,5)P2. Docking was performed using MolDock (Thomsen and Christensen, 2006). First, the proteins and the ligand were automatically prepared (charges and protonation states were assigned), and the automatic prediction of cavities was applied to the protein models to constrain predicted conformations (complexes) during the search process. If no cavities were reported, the search procedure was not constrained for conformation solutions. Before the docking, side chain flexibility for the protein was assigned for residues that were found to have functional effects on the PIP2 apparent affinity, based upon the known torsional degrees of freedom for each type of residue. A maximum of 35 torsional degrees of freedom were marked to be flexible during docking. The receptor (protein) minimization for each found conformation (complex) was restrained to a grid resolution of 0.30 Å around the central searching region. The best predicted conformations (the lowest energy complexes) between GPMI-P2 and the channel proteins were searched by sampling positions, orientations, and torsion angles of the ligand as well as torsion angles of the protein side chains. Finally, a total of 150 docking runs for each homology model conformation were performed with 2,000 interactions per run applying the MolDock Optimizer algorithm, and the affinities, hydrogen bonds, and electrostatic energies were calculated and ranked to get the top solution with a root mean square distance (RMSD) from a reference ligand (GPMI-P2) <2 Å.

Online Supplemental Material

We include as supplemental material three tables summarizing the hydrogen bonds predicted between GPMI-P2 and the helix A-B linkers of wt and mutant Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 channels. Also included are four supplemental figures. Fig. S1 shows the efficacy and apparent affinity of phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate for wt Kv7.2 and the KRR-EEE mutant. Fig. S2 shows the voltage dependence of activation of wt Kv7.2 and the KRR-EEE mutant. Fig. S3 displays the Po at 0 mV and PIP2 apparent affinity for the K449E, K469E, and D458N Kv7.2 mutants, and the E423V and N431D Kv7.3 mutants that did not alter those parameters from their respective wt channels. Fig. S4 shows the results of overexpression of PI(4)5-kinase in CHO cells on whole cell currents from wt Kv7.2, KRR-EEE, and K449E mutants, and wt Kv7.3 and the K406Q mutant. The online supplemental material is available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200810007/DC1.

RESULTS

Our primary examination of the apparent affinity of Kv7 channels for PIP2 was by recording single-channel currents in patches from CHO cells transiently transfected with the appropriate cDNA. Recordings were first made in cell-attached mode, where we assume the Po at saturating voltages to be governed by the tonic abundance of PIP2 in the membrane. Experiments were performed with a high [K+] Ringer's in the bath to “zero” the resting potential of the cells (refer to Materials and methods). As before, Kv7 channels were identified by their unitary conductance and appropriate voltage dependence (Li et al., 2004, 2005). Only patches with seals >10 GΩ were used for recording, and data were collected for >5 min to verify the total number of channels in the patch. The Po was evaluated at 0 mV, which is nearly a saturating voltage for these channels (Shapiro et al., 2000; Selyanko et al., 2001). We will call this value Po, 0 mV. Satisfactory patches were then excised into inside-out mode, where the responses to bath application of the short-chain, water-soluble PIP2 analogue dioctanoyl-PIP2 (diC8-PIP2) were assayed (Zhang et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005).

The Carboxy Terminus Determines Po, 0 mV and PIP2 Apparent Affinity

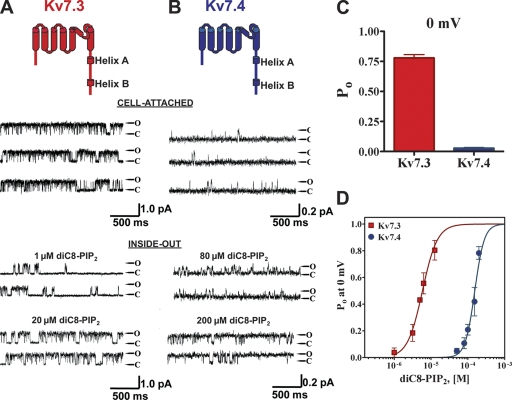

We began by confirming our earlier work indicating the large divergence in the apparent affinity of PIP2 for Kv7.3 and Kv7.4 (Li et al., 2005), and to establish a baseline for our subsequent mutagenesis. In cell-attached patches containing a single Kv7.3 channel, the unitary current at 0 mV was 0.84 ± 0.09 pA and the Po, 0 mV was 0.78 ± 0.06 (n = 5) (Fig. 1, A and C). For those containing a single Kv7.4 channel, however, the unitary current was 0.19 ± 0.04 pA and the Po, 0 mV was only 0.03 ± 0.02 (n = 9) (Fig. 1, B and C). Upon excision of patches into inside-out mode, the activity of both types of channel ran down, but was restored upon the addition of diC8-PIP2 to the bathing solution. Upon patch excision, the run down of Kv7.3 channels was slow (1–2 min), and restoration of activity by diC8-PIP2 addition was very rapid. On the other hand, the run down of Kv7.4 channels upon excision was complete within 30 s, and the addition of diC8-PIP2 restored activity only after several minutes. The concentration of diC8-PIP2 required to restore activity was very divergent for the two types of channels. For Kv7.3, diC8-PIP2 at 1 μM produced substantial activation and at 20 μM, the Po, 0 mV was high (Fig. 1 A). On the other hand, for Kv7.4, diC8-PIP2 at 80 μM enabled only modest channel opening, and 200 μM was required for high Po, 0 mV of Kv7.4 channels (Fig. 1 B). For both channels, Po, 0 mV was measured over a range of diC8-PIP2 concentrations in the bath, and the summarized results plotted as a dose–response relation of Po at 0 mV versus [diC8-PIP2] (Fig. 1 D). These data were fit by Hill equations in which the minimum and maximum were constrained to be zero and unity, respectively. Good fits were obtained for both Kv7.3 and Kv7.4 datasets, but with highly differential values for EC50. For Kv7.3, the EC50 was 6 ± 1 μM and the Hill coefficient (nH) was 2.2 ± 0.4 (n = 2–4 patches). For Kv7.4, the EC50 was 154 ± 1 μM and nH was 2.3 ± 0.5 (n = 2–7 patches). These results are wholly consistent with PIP2 regulating the activity of both Kv7.3 and Kv7.4 channels, but with efficacies dramatically differing by 26-fold.

Figure 1.

Kv7.3 and 7.4 display highly differential Po, 0 mV values and PIP2-apparent affinities. Shown are single-channel patch-clamp recordings from a unitary Kv7.3 (A) or Kv7.4 (B) channel obtained in the cell-attached (top) or excised inside-out (bottom) configurations at 0 mV. The indicated concentrations of diC8-PIP2 were perfused over the inside-out patches. The insets above the current records show the topography of a channel subunit, with the A and B helices indicated. Here and throughout, Kv7.3 and Kv7.4 are indicated as red or blue, respectively. (C) Bars summarize the Po at 0 mV in cell-attached patches for Kv7.3 and Kv7.4. (D) Plotted are the summarized Po values at 0 mV for the channels in inside-out configuration, obtained over a range of diC8-PIP2 concentrations. The data were fit by a Hill equation of the form and parameters given in the text.

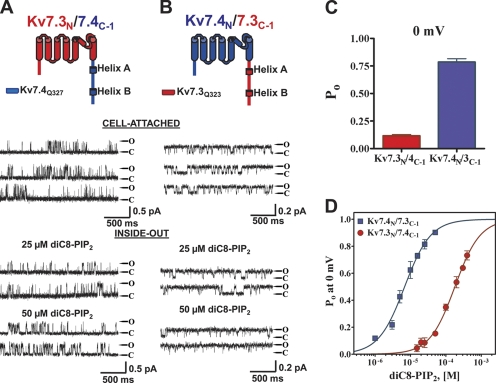

We tested the assumption that the domain responsible for PIP2 apparent affinity lies within the carboxy terminus by constructing chimeras in which the part of the channels after S6 was swapped (junction point Q323 in Kv7.3 and Q327 in Kv7.4), and its Po, 0 mV and PIP2 apparent affinity was tested as described above. The first chimera, Kv7.3N/7.4C−1, exhibited unitary current amplitudes more similar to wt Kv7.3, but the Po, 0 mV similar to wt Kv7.4. Thus, at 0 mV, the unitary current amplitude was 0.50 ± 0.14 pA and the Po, 0 mV was 0.12 ± 0.03 (n = 12) (Fig. 2 A). The converse chimera Kv7.4N/7.3C−1 exhibited the unitary current similar to wt Kv7.4, but the PIP2 apparent affinity similar to wt Kv7.3. Its unitary current amplitude was 0.23 ± 0.05 pA and the Po, 0 mV was 0.79 ± 0.09 (n = 9) (Fig. 2 B). The PIP2 apparent affinity was also found to be conferred by the identity of the carboxy terminus. Thus, in inside-out mode, diC8-PIP2 at 25 μM supported only low opening of the Kv7.3N/7.4C−1 chimera, but supported robust opening of the Kv7.4N/7.3C−1 chimera, whereas at 50 μM, the former exhibited still only modest opening, whereas the Po, 0 mV of the latter was near unity (Fig. 2, A and B). These inside-out data were again summarized as a dose–response relation of Po at 0 mV and fit by Hill equations (Fig. 2 D). For Kv7.3N/7.4C−1, the EC50 and nH were 180 ± 1 μM and 1.2 ± 0.1 (n = 2–10 patches), and for Kv7.4N/7.3C−1, they were 7 ± 1 μM and 1.2 ± 0.1 (n = 2–8 patches). Thus, the PIP2 apparent affinities differ, inversely, by the same 26-fold as for the wt channels, suggesting that the domains conferring PIP2 apparent affinity are wholly contained within the carboxy terminus of the channels. Although the Hill coefficients were significantly reduced compared with the parent channels, we also saw variable nH values in our previous inside-out patch work (Li et al., 2005), and those reported in this paper are within the range of that proposed for PIP2 interactions with Kv7 channels (Zhang et al., 2003; Suh and Hille, 2005). However, the possibility exists that the stoichiometry of PIP2 molecules to channel subunits, or the co-cooperativity of binding between the two, is reduced in the chimeras relative to the parent channels.

Figure 2.

The exchange of carboxy termini between Kv7.3 and Kv7.4 wholly inverts their differential Po and PIP2-apparent affinities. The first chimera pair between Kv7.3 and Kv7.4 was created by exchange of the entire carboxy termini. Shown are single-channel patch-clamp recordings from the Kv7.3/7.4C-1 (A) or Kv7.4/7.3C-1 (B) chimeras obtained in the cell-attached (top) or excised inside-out (bottom) configurations at 0 mV. The indicated concentrations of diC8-PIP2 were perfused over the inside-out patches. The insets above the current records show the topography and chimera junctions of the channel subunits. (C) Bars summarize the Po at 0 mV in cell-attached patches for these chimeras. (D) Plotted are the summarized Po values at 0 mV for the chimeras in inside-out configuration obtained over a range of diC8-PIP2 concentrations. The data were fit by a Hill equation of the form and parameters given in the text.

The Linker between the Two Calmodulin (CaM) Binding Sites in the Carboxy Terminus Is the Site of PIP2 Action

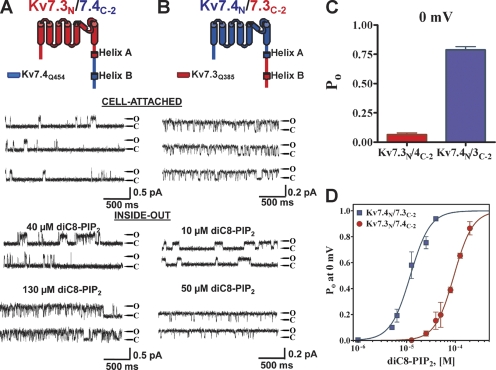

The carboxy terminus of Kv7 channels contains four highly conserved domains thought very likely to be helices, named A–D starting from the end of S6 (Yus-Najera et al., 2002). Helices A and B each contain sites of CaM binding (Wen and Levitan, 2002; Yus-Najera et al., 2002; Gamper and Shapiro, 2003; Shamgar et al., 2006). Helices C and D comprise the “A domain,” thought to be responsible for tetrameric assembly and subunit-specific heteromer formation (Maljevic et al., 2003; Schwake et al., 2003, 2006). Structural determination of helix D, the A domain “tail,” has shown it to be a coiled-coiled formation indispensable for assembly of functional channels (Howard et al., 2007). Given the evidence presented above indicating the C terminus to confer PIP2-apparent affinity, we generated additional Kv7.3/7.4 chimeras to further localize the critical domain. The next chimera set has a junction point immediately at the end of helix A (Q385 in Kv7.3 and Q454 in Kv7.4). The Kv7.3N/7.4C-2 chimera was also more similar to wt Kv7.3 in permeation properties, but to Kv7.4 in Po, 0 mV values and PIP2 apparent affinity (Fig. 3, A and C). Thus, in cell-attached patches at 0 mV, the unitary current was 0.49 ± 0.09 pA and the Po was 0.06 ± 0.03 (n = 5), and upon excision into inside-out patches, channel activity ran down rapidly. The addition of diC8-PIP2 at 40 μM restored only modest activity, and at 130 μM, Po was high. On the other hand, the converse Kv7.4N/7.3C-2 chimera was more similar to wt Kv7.4 in permeation properties, but to Kv7.3 in maximal Po and PIP2 apparent affinity (Fig. 3, A and C). Thus, in cell-attached patches at 0 mV, the unitary current was 0.26 ± 0.07 pA and the Po was 0.79 ± 0.06 (n = 5), and upon excision into inside-out patches, channel activity ran down more slowly. The addition of diC8-PIP2 at only 10 μM restored significant activity, and by 50 μM, Po was near unity. The inside-out patch data are summarized in Fig. 3 D and fit by Hill equations, showing the apparent affinities of the channels for diC8-PIP2 differing by approximately eightfold. For the Kv7.3N/7.4C-2 chimera, the EC50 was 94 ± 1 μM and nH was 2.2 ± 0.2 (n = 2–4 patches), whereas for the Kv7.4N/7.3C-2 chimera, the EC50 was 12 ± 1 μM and nH was 2.1 ± 0.3 (n = 2–5 patches).

Figure 3.

Exchange of the carboxy termini downstream of helix A mostly inverts the differential Po values and PIP2-apparent affinities. The second chimera pair between Kv7.3 and Kv7.4 was created by exchange of the carboxy termini downstream of the end of helix A. Shown are single-channel patch-clamp recordings from the Kv7.3/7.4C-2 (A) or Kv7.4/7.3C-2 (B) chimeras obtained in the cell-attached (top) or excised inside-out (bottom) configurations at 0 mV. The indicated concentrations of diC8-PIP2 were perfused over the inside-out patches. The insets above the current records show the topography and chimera junctions of the channel subunits. (C) Bars summarize the Po at 0 mV in cell-attached patches for these chimeras. (D) Plotted are the summarized Po values at 0 mV for the chimeras in inside-out configuration obtained over a range of diC8-PIP2 concentrations. The data were fit by a Hill equation of the form and parameters given in the text.

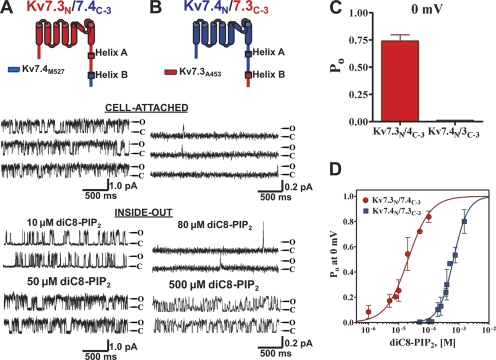

The third chimera pair was very similar to the second, but it does not include the 71-residue linker between the A and B helices (junction point at A453 for Kv7.3 and M527 for Kv7.4). In contrast to the first two chimera pairs, all three properties of permeation, Po, 0 mV, and PIP2 apparent affinity of these chimeras resembled the identity of the parent backbone channels, suggesting little effect on these properties of the C termini distal to the junction point. Thus, at 0 mV, the Kv7.3N/7.4C-3 chimera displayed a unitary current amplitude of 0.82 ± 0.13 and a Po of 0.74 ± 0.12 (n = 5) (Fig. 4 A), similar to the values of wt Kv7.3. Upon excision, channel activity ran down relatively slowly. The addition of diC8-PIP2 at only 10 μM restored significant activity, and by 50 μM, the Po was high (Fig. 4 A). On the other hand, the Kv7.4N/7.3C-3 chimera displayed a unitary current of 0.12 ± 0.02 and a Po, 0 mV of only 0.015 ± 0.003 (n = 6), and upon excision, channel activity ran down rapidly. The addition of diC8-PIP2 at 80 μM produced only rare openings, and 500 μM was required to generate high activity (Fig. 4 B). Again, we evaluated the Po, 0 mV for these chimeras over a range of diC8-PIP2 concentrations and fit the data by Hill equation curves (Fig. 4 D). For the Kv7.3N/7.4C-3 chimera, the EC50 was 21 ± 1 μM, with an nH of 1.2 ± 0.2 (n = 2–5 patches), whereas the inverse Kv7.4N/7.3C-3 chimera displayed a 30-fold lower apparent affinity for diC8-PIP2, with an EC50 of 660 ± 1 μM and an nH of 1.8 ± 0.2 (n = 2–5 patches).

Figure 4.

Exchange of the carboxy termini downstream of the linker between helices A and B retains the differential Po values and PIP2-apparent affinities of the wt channels. The third chimera pair between Kv7.3 and Kv7.4 was created by exchange of the carboxy termini downstream of the end of the linker between helices A and B. Shown are single-channel patch-clamp recordings from the Kv7.3/7.4C-3 (A) or Kv7.4/7.3C-3 (B) chimeras obtained in the cell-attached (top) or excised inside-out (bottom) configurations at 0 mV. The indicated concentrations of diC8-PIP2 were perfused over the inside-out patches. The insets above the current records show the topography and chimera junctions of the channel subunits. (C) Bars summarize the Po at 0 mV in cell-attached patches for these chimeras. (D) Plotted are the summarized Po values at 0 mV for the chimeras in inside-out configuration obtained over a range of diC8-PIP2 concentrations. The data were fit by a Hill equation of the form and parameters given in the text.

The single-channel data from the chimeras between high PIP2 affinity Kv7.3 and low PIP2 affinity Kv7.4 are summarized in Table I. Those data delineate a primary domain conferring high or low PIP2 apparent affinity. In accord with the assumption putting the locus of PIP2 action within the C terminus, exchange of the entire C terminus (set 1) completely inverted the large differences in Po, 0 mV and PIP2 apparent affinity of the channels. However, exchange of the C terminus from the start of the B helix, which contains the second CaM binding site, (set 3) retained the wt differences, suggesting that the C terminus distal to that point is not important for PIP2 interactions. Of particular interest is chimera set 2, in which the junction point is just after helix A, but before the linker between helices A and B. This chimera pair showed a relationship in Po, 0 mV and PIP2 apparent affinity that mostly (eightfold) inverted that between wt Kv7.3 and Kv7.4, with another threefold coming from another part of the C terminus, probably the A helix. These data suggest that the ∼70-residue A-B linker contains the primary domain determining apparent affinity for PIP2, and likely a major site of actual PIP2 binding.

TABLE I.

Single-Channel Properties and PIP2-apparent Affinities of Kv7.3/7.4 Chimeras at 0 mV

| Cell-attached | Inside-out + 25 μM diC8-PIP2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unitary current (pA) | Po | n | EC50 (μM) | nH | |

| Kv7.3 wt | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 5 | 6 ± 1 | 2.2 ± 0.4 |

| Kv7.4 wt | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 9 | 154 ± 1 | 2.3 ± 0.5 |

| Kv7.3N/ Kv7.4C-1 | 0.50 ± 0.14 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 12 | 180 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| Kv7.4N/ Kv7.3C-1 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 0.79 ± 0.09 | 9 | 7 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| Kv7.3N/ Kv7.4C-2 | 0.49 ± 0.09 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 5 | 94 ± 1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 |

| Kv7.4N/ Kv7.3C-2 | 0.26 ± 0.07 | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 5 | 12 ± 1 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| Kv7.3N/ Kv7.4C-3 | 0.82 ± 0.13 | 0.74 ± 0.12 | 5 | 21 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| Kv7.4N/ Kv7.3C-3 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.015 ± 0.003 | 6 | 660 ± 1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

Given on the left are the values of the unitary current and Po of the indicated wt or chimeric channels in cell-attached patches at 0 mV. Given on the right are the results of Boltmann equation fits of dose–response data of single-channel Po at 0 mV vs. [diC8-PIP2] obtained in inside-out patches. EC50 and nH refer to the [diC8-PIP2] that yield half-maximal Po and the Hill equation coefficient, respectively.

Identification of Putative PIP2-interacting Residues within the A-B Linker

There are eight positively charged residues in the A-B linker that are conserved among Kv7.2-7.4. Fig. 5 shows an alignment of the 57-residue core of the A-B linker that contains several conserved, positively charged residues of Kv7 channels that could interact with the negatively charged phosphates in the head group of PIP2. Given the accepted electrostatic nature of the binding of anionic PIP2 to cationic domains of many proteins (McLaughlin and Murray, 2005; Rosenhouse-Dantsker and Logothetis, 2007) and the clear importance of basic residues in PIP2 interactions (Zhang et al., 1999; Shyng et al., 2000b; Soom et al., 2001; Dong et al., 2002; Lopes et al., 2002; Hardie, 2007), we focused on these conserved residues by evaluating the effects on Po and apparent PIP2 affinity of their charge reversal or neutralization. We chose to make these mutations in Kv7.2 because its relatively low apparent affinity for PIP2, similar to Kv7.4 (Li et al., 2005), should make it most sensitive to altering the strength of interaction with the lipids (Gamper and Shapiro, 2007) and because of its larger unitary conductance that facilitated such measurements. Critical residues thus identified in Kv7.2 were then tested by mutagenesis of the corresponding residues in Kv7.3. We also made residue swaps that differ between Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 in this region. As before, the Po values of the mutants were tested at 0 mV initially in cell-attached mode, and then in inside-out patches in the presence of 25 μM diC8-PIP2. This concentration was judged to most nearly correlate with the tonic PIP2 levels seen by the channels in intact cells, as evidenced from the similar maximal Po values in cell-attached mode and in inside-out configuration at this concentration (this study and Li et al., 2005).

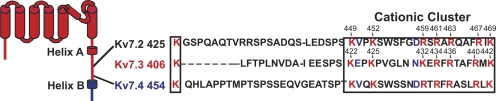

Figure 5.

Alignment of the helix A-B linker in Kv7.2-7.4 channels implicated in PIP2 interactions by this study. Shown is the alignment of the 57-residue core of the linker between helices A and B. The Kv7.3/7.4C-2 chimera is shown schematically on the left. Conserved basic residues tested in this study by mutagenesis of Kv7.2 or Kv7.3 are indicated in red; nonconserved residues tested by swapping them between Kv7.2 and 7.3 are indicated in blue. The large and small boxes enclose a cluster of positively charged residues and a critical conserved basic residue, respectively.

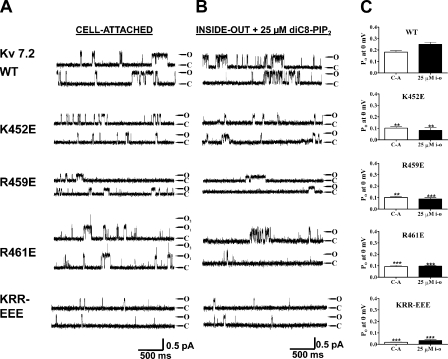

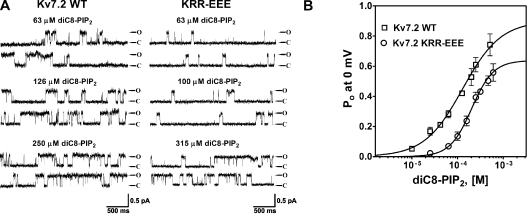

Seven conserved basic residues comprise a cationic cluster in the middle of the helix A-B linker (Fig. 5, large box). For three of them, K452, R459, and R461, mutation to a negatively charged glutamate resulted in an ∼50% decrease of Po, 0 mV values, both in cell-attached mode and as a response to 25 μM diC8-PIP2 in inside-out mode (Fig. 6). Thus, for wt Kv7.2, K452E, R459E, and R461E, the Po at 0 mV in cell-attached mode were 0.18 ± 0.04 (n = 9), 0.10 ± 0.02 (n = 3; P < 0.05), 0.10 ± 0.02 (n = 5; P < 0.05), and 0.093 ± 0.025 (n = 6; P < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 6, A and C). In inside-out mode with 25 μM diC8-PIP2 added to the bath, the Po values at 0 mV were 0.25 ± 0.04 (n = 5), 0.081 ± 0.031 (n = 3; P < 0.05), 0.088 ± 0.019 (n = 4; P < 0.01), and 0.096 ± 0.008 (n = 3; P < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 6, B and C, and Table II). These results suggest that these three conserved positive residues are involved in PIP2 interactions. When these mutations were combined as a triple KRR-EEE Kv7.2 mutant, there was a dramatic decrease in Po, 0 mV by ∼95%. Thus, the Po, 0 mV of this triple mutant in cell-attached patches was only 0.017 ± 0.005 (n = 10; P < 0.001), and in inside-out patches, it was only 0.032 ± 0.020 (n = 8; P < 0.001) in the presence of 25 μM diC8-PIP2. To investigate the altered apparent affinity of diC8-PIP2 for the KRR-EEE triple mutant over a larger range of concentrations, we obtained single-channel Po, 0 mV values for both wt Kv7.2 and the KRR-EEE mutant as a function of diC8-PIP2 concentration added to the bath. Fig. 7 A shows representative recordings at different diC8-PIP2 concentrations, with the corresponding summarized Po values at 0 mV plotted versus [diC8-PIP2] for the wt and mutant channels superimposed in Fig. 7 B, with the data fit by Hill equations. For wt Kv7.2, the EC50 was 111 ± 1 μM with an nH of 1.2 ± 0.1 (n = 2–6 patches), whereas for the KRR-EEE mutant, the EC50 was 204 ± 1 μM with an nH of 1.8 ± 0.1 (n = 2–6 patches). Significantly, the Hill fits suggest the efficacy of diC8-PIP2, defined as the maximum Po elicited by a saturating concentration of diC8-PIP2, to be significantly different between the two, with the fitted Po,max for wt Kv7.2 of 0.84 ± 0.05 falling to 0.64 ± 0.02 for the triple mutant. These data suggest that the ability of PIP2 to activate Kv7.2 channels is much reduced by the KRR-EEE triple-charge reversal.

Figure 6.

A conserved triplet of basic residues in the helix A-B linker is critical for PIP2 interactions with Kv7.2, as shown by charge-reversal substitutions. Shown are single-channel records in the cell-attached (A) or inside-out patch (B) configurations of the indicated Kv7.2 wt or mutant channel at a membrane potential of 0 mV. The inside-out patches were perfused with diC8-PIP2 at 25 μM, which mostly closely corresponds to the activity seen in the cell-attached patch (see Results). The traces labeled KRR-EEE are from a triple mutant consisting of K452E/K459E/R461E. (C) Bars indicate the summarized Po values at 0 mV for the cell-attached (C-A) or inside-out patch (25 μM i-o) data for the indicated channel type. Asterisks above each bar indicate the level of significance compared with the corresponding values for wt Kv7.2. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

TABLE II.

Po of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 WT and Mutant Channels at 0 mV

| Cell-attached | n | Inside-out + 25 μM diC8-PIP2 | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kv7.2 wt | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 9 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 5 |

| K452E | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 3 | 0.081 ± 0.031 | 3 |

| R459E | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 5 | 0.088 ± 0.019 | 4 |

| R461E | 0.093 ± 0.025 | 6 | 0.096 ± 0.008 | 3 |

| KRR-EEE | 0.017 ± 0.005 | 10 | 0.032 ± 0.020 | 8 |

| K425Q | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 4 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 5 |

| K452Q | 0.086 ± 0.006 | 6 | 0.093 ± 0.014 | 5 |

| R459Q | 0.075 ± 0.007 | 4 | 0.061 ± 0.012 | 4 |

| R461Q | 0.076 ± 0.008 | 4 | 0.087 ± 0.015 | 4 |

| KRR-QQQ | 0.059 ± 0.013 | 6 | 0.055 ± 0.006 | 7 |

| R463Q | 0.045 ± 0.022 | 7 | 0.042 ± 0.019 | 8 |

| R467Q | 0.071 ± 0.033 | 10 | 0.079 ± 0.025 | 7 |

| R463E | 0.42 ± 0.20 | 10 | 0.46 ± 0.12 | 3 |

| R467E | 0.45 ± 0.19 | 8 | 0.52 ± 0.11 | 4 |

| K449E | 0.195 ± 0.07 | 8 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 5 |

| K469E | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 4 | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 4 |

| D458N | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 4 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 3 |

| Kv7.3 wt | 0.75 ± 0.09 | 4 | 0.72 ± 0.16 | 4 |

| K406Q | 0.26 ± 0.10 | 4 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 4 |

| KKR-EEE | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 5 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 5 |

| E423V | 0.65 ± 0.19 | 5 | 0.67 ± 0.17 | 5 |

| N431D | 0.73 ± 0.10 | 5 | 0.66 ± 0.16 | 4 |

Given on the left are the values of the unitary current and Po of the indicated wt or mutant channels at 0 mV in cell-attached patches or in inside-out patches in the presence of 25 μM diC8-PIP2. n refers to the number of patches in each case. For Kv7.2, KRR-EEE and KRR-QQQ refer to the triple mutant of K452, R459, and R461. For Kv7.3, KKR-EEE refers to the triple mutant of K425, K432, and R434.

Figure 7.

The Kv7.2 KRR-EEE mutant displays reduced apparent affinity and efficacy of diC8-PIP2 for channel opening. (A) Shown are single-channel records at 0 mV from wt (left) and KRR-EEE (right) Kv7.2 channels in inside-out patches under the indicated concentrations of diC8-PIP2. (B) Plotted are the summarized values of the Po at 0 mV for the two channels versus diC8-PIP2 concentration. The data were fit by Hill equations of the form and parameters given in the text.

Previous work indicates that in addition to PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate (PI(3,4)P2) can also activate Kv7.2/7.3 (Li et al., 2005) and some types of Kir (Rohacs et al., 1999) channels. We therefore determined if the apparent affinity of PI(3,4)P2 was also reduced by the KRR-EEE mutant. In these experiments, channel Po at 0 mV was assayed in cell-attached conformation as before, and in inside-out mode under a range of diC8-PI(3,4)P2 concentrations added to the bath. As for diC8-PIP2, the Po, 0 mV induced by the lipid at 25 μM was sharply reduced in the KRR-EEE mutant (WT 0.09 ± 0.02 vs. KRR-EEE 0.009 ± 0.005; n = 4), although at higher concentrations, the differences were increasingly less severe (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200810007/DC1). Finally, to make sure that the changes in Po at 0 mV seen in the charge-reversal mutants are not due to changes in the voltage dependence of activation, we obtained activation curves for wt Kv7.2 and the KRR-EEE mutant. Normalized tail current amplitudes were plotted as a function of prepulse potential over a wide range of potentials and the data fit by Boltzmann relations (Fig. S2). For the KRR-EEE mutant, the value of V1/2 was slightly shifted to depolarized voltages (−15.3 ± 0.6 mV; n = 7) compared with wt Kv7.2 (−22.2 ± 0.9 mV; n = 9), but the shift was much less than what would be required for the dramatic changes in Po at 0 mV that we observed. Thus, at 0 mV, the fractional activation of wt Kv7.2 and of the KRR-EEE mutant was 0.82 ± 0.04 (n = 9) and 0.80 ± 0.05 (n = 7), respectively, which are not significantly different.

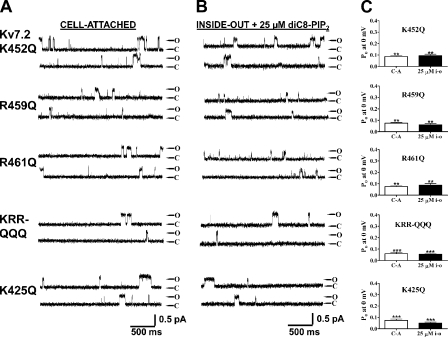

We then investigated the effect of charge neutralization of the K452, R459, and R461 residues identified above by mutation to glutamines. As for the charge-reversal mutations, each of the K452Q, R459Q, and R461Q mutants exhibited a significantly lower Po, 0 mV in both cell-attached patches and in inside-out mode in the presence of 25 μM diC8-PIP2 (Fig. 8). Thus, for K452Q, R459Q, and R461Q, the Po at 0 mV in cell-attached patches were 0.09 ± 0.01 (n = 6), 0.08 ± 0.01 (n = 4), and 0.08 ± 0.01 (n = 4), respectively, and in inside-out patches in the presence of 25 μM diC8-PIP2, they were 0.09 ± 0.01 (n = 5), 0.06 ± 0.01 (n = 4), and 0.09 ± 0.02 (n = 4), respectively (Table II). When the charge neutralizations were combined together, the resulting KRR-QQQ triple mutant displayed an even lower Po, 0 mV, to 0.06 ± 0.01 (n = 6) and 0.06 ± 0.01 (n = 7) in cell-attached and inside-out modes, respectively. Thus, both charge-reversal and charge-neutralization mutations suggest that the KRR triplet is critical for phosphoinositide interactions with Kv7.2 channels (Table II). We also found a strong effect of mutating another basic residue still within the helix A-B linker, but some 25 residues further upstream of the “cationic cluster” thus far identified. Indeed, when the positive charge of a conserved lysine at position 425 in Kv7.2 was neutralized by mutation to glutamine, the Po, 0 mV was substantially lowered. The Po values at 0 mV were 0.07 ± 0.01 (n = 4; P < 0.01) and 0.05 ± 0.01 (n = 5; P < 0.01) in cell-attached and inside-out modes, respectively.

Figure 8.

A conserved cluster of basic residues in the helix A-B linker is critical for PIP2 interactions with Kv7.2, as shown by charge-neutralization substitutions. Shown are single-channel records in the cell-attached (A) or inside-out patch (B) configurations of the indicated Kv7.2 wt or mutant channel at a membrane potential of 0 mV. The inside-out patches were perfused with diC8-PIP2 at 25 μM, which most closely corresponds to the activity seen in the cell-attached patch (see Results). The traces labeled KRR-QQQ are from a triple mutant consisting of K452Q/R459Q/R461Q. (C) Bars indicate the summarized Po values at 0 mV for the cell-attached (C-A) or inside-out patch (25 μM i-o) data for the indicated channel type. Asterisks above each bar indicate the level of significance compared with the corresponding values for wt Kv7.2. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

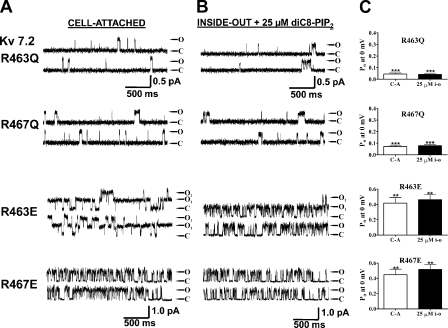

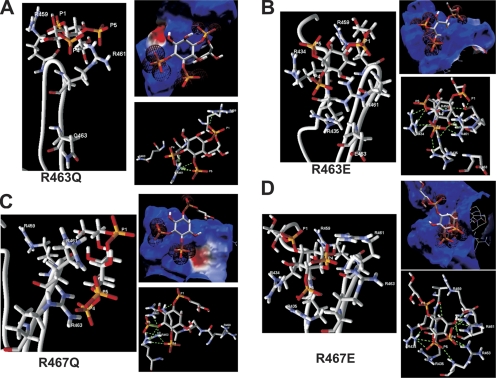

Another pair of basic residues in the distal part of this cationic cluster displayed a more complex response to mutations. Indeed, mutation of the conserved R463 and R467 in Kv7.2, which are located just downstream of the basic residues discussed above, had effects that depended on the nature (charged vs. noncharged) of the substituted residue. Mutation of R463 or R467 to the noncharged glutamine decreased the apparent PIP2 apparent affinity as manifested by a reduction in Po at 0 mV by ∼70% both in cell-attached mode or in inside-out patches in the presence of 25 μM diC8-PIP2. For R463Q, the Po, 0 mV was reduced to 0.045 ± 0.022 (n = 7; P < 0.001) and 0.042 ± 0.019 (n = 8; P < 0.001), and for R467Q, the Po, 0 mV was reduced to 0.071 ± 0.033 (n = 10; P < 0.01) and 0.079 ± 0.025 (n = 7; P < 0.01) in cell-attached and inside-out modes, respectively (Fig. 9, A and C, and Table II). Unexpectedly, however, when the R463 and R467 residues were mutated to glutamates, the Po, 0 mV values increased over those of wt Kv7.2 in both cell-attached and inside-out modes. For R463E, the Po values at 0 mV were 0.42 ± 0.20 (n = 10; P < 0.05) and 0.46 ± 0.12 (n = 3; P < 0.05), and for R467E, they were 0.45 ± 0.19 (n = 8; P < 0.05) and 0.52 ± 0.11 (n = 4; P < 0.05) in cell-attached and inside-out modes, respectively (Fig. 9, B and C, and Table II). The mechanism explaining these seemingly counterintuitive results is suggested by the homology modeling performed below in this paper.

Figure 9.

Charge neutralization or reversal of two other basic residues in the helix A-B linker produces highly divergent effects. Shown are single-channel records at 0 mV from Kv7.2 R463Q and R467Q (A), or R463E and R467E (B), in the cell-attached (left) or inside-out configuration in the presence of 25 μM diC8-PIP2 (right). (C) Bars show summarized Po values at 0 mV for both configurations for the indicated mutant. Asterisks above each bar indicate the level of significance compared with the corresponding values for Kv7.2 wt. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

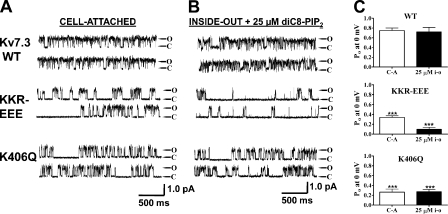

Given the identification of critical PIP2 interaction residues in Kv7.2, we asked if the corresponding locus in Kv7.3 is similarly implicated in PIP2 action. In Kv7.3, the corresponding residues of the KRR triplet in Kv7.2 are K425, K432, and R434. When the triple Kv7.3 KKR-EEE triple mutant was tested in single-channel patches, the Po at 0 mV was sharply reduced from the wt in both cell-attached and inside-out modes. For wt Kv7.3 and KKR-EEE (these patches were studied during the same days), the Po at 0 mV were 0.75 ± 0.09 (n = 4) and 0.34 ± 0.03 (n = 5; P < 0.01) in cell-attached mode, respectively, and 0.72 ± 0.16 (n = 4) and 0.10 ± 0.04 (n = 5; P < 0.01) in inside-out mode with 25 μM diC8-PIP2, respectively (Fig. 10 and Table II). Thus, this locus is critical for PIP2 interactions with Kv7.3 as well. We also investigated K406, which is the corresponding residue to K425 in Kv7.2. The Kv7.3 K406Q neutralization similarly strongly lowered the channel Po at 0 mV to 0.26 ± 0.10 (n = 4; P < 0.01) in cell-attached mode and 0.27 ± 0.07 (n = 4; P < 0.01) in inside-out mode with 25 μM diC8-PIP2 (Fig. 10 and Table II). We conclude that this PIP2 interaction site is conserved between Kv7.2 and Kv7.3.

Figure 10.

Four basic residues shown to be critical for PIP2 interactions in Kv7.2 are also critical for the corresponding residues of Kv7.3. Shown are single-channel records in the cell-attached (A) or inside-out patch (B) configurations of the indicated Kv7.3 wt or mutant channel at a membrane potential of 0 mV. The inside-out patch records are in the presence of 25 μM diC8-PIP2. The traces labeled KKR-EEE are from a triple mutant consisting of K425E, K432E, and R434E. (C) Bars show summarized Po values at 0 mV for both configurations for the indicated channel. Asterisks above each bar indicate the level of significance compared with the values for the corresponding wt channel. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Another pair of conserved basic residues in the cationic cluster seems not to be critical for PIP2 interactions. Thus, charge neutralizations of K449E and K469E did not show differences in Po values compared with wt Kv7.2, either in cell-attached or inside-out modes (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200810007/DC1). For K449E, the Po, 0 mV were 0.195 ± 0.07 (n = 8) and 0.191 ± 0.05 (n = 5), respectively, and for K469E, they were 0.20 ± 0.06 (n = 4) and 0.21 ± 0.09 (n = 4), respectively (Fig. S3, top two panels, and Table II). Besides positively charged amino acids, other nonbasic residues have been identified as putative PIP2-interacting residues in the proximal C termini of Kir channels. In particular, the activation of Kir3 channels by Na+ ions has been attributed to an increase in the strength of PIP2 interactions (Sui et al., 1996, 1998) via charge screening of negative residues (D223 in Kir3.4 and D226 in Kir3.2) by Na+ ions (Ho and Murrell-Lagnado, 1999; Zhang et al., 1999). By analogy, we noticed residue D458 in Kv7.2 adjacent to R459 identified to affect PIP2 apparent affinity, whereas Kv7.3 has the uncharged N431 in that position. Thus, we evaluated the D458N mutation in Kv7.2 but did not find any effect on Po, 0 mV values, which were 0.20 ± 0.04 (n = 4) and 0.21 ± 0.03 (n = 3) in cell-attached and inside-out modes, respectively (Fig. S3, middle panel, and Table II). We also tested the effect on maximal Po of the inverse N431D mutation in Kv7.3 but also saw no effect of this mutation. For N431D, the cell-attached Po at 0 mV was 0.73 ± 0.10 (n = 5), and in inside-out mode in the presence of 25 μM diC8-PIP2, the Po, 0 mV was 0.66 ± 0.16 (n = 4) (Fig. S3, bottom, and Table II). Thus, although we did not systematically explore any Na+ dependence on the Po of Kv7 channels, we consider the aspartate in that position not to play a significant role in PIP2 interactions. We tested another negatively charged residue in Kv7.3 within this domain, E423, which in Kv7.2 is V450 at this position. However, the E423V mutation also did not display any differences in Po, 0 mV or PIP2-apparent affinity compared with wt Kv7.3. For Kv7.3 E423V, the Po at 0 mV was 0.65 ± 0.19 (n = 5) and 0.67 ± 0.17 (n = 5) in cell-attached and inside-out modes, respectively (Fig. S3, bottom, and Table II).

Overexpression of PI(4)5-Kinase Affects Whole Cell Current Amplitudes in Accord with Single-Channel Po Values

In intact cells, the activity of a given PIP2-regulated channel should be governed by the tonic level of plasmalemmal PIP2. The tonic PIP2 levels are determined by the balance between sequential phosphorylations of phosphatidylinositide by PI(4)-kinase and PI4(5)-kinase, dephosphorylation of PIP2 by 5-phosphatases, and basal PLC activity (Xu et al., 2003; Suh et al., 2004). Tonic PIP2 levels have been experimentally increased by overexpression of PI(4)5-kinase (Shyng et al., 2000a; Li et al., 2005; Winks et al., 2005; Suh et al., 2006). For Kv7 channels, the effects were a decrease in receptor-mediated suppression and an increase in the Po, 0 mV values and whole cell current of Kv7.2, but not Kv7.3. The latter is consistent with the differential apparent affinity for PIP2 between the channels (because the normal maximal Po of Kv7.3 is near unity, it cannot be increased further by greater PIP2 abundance). Thus, we used the PI(4)5-kinase–mediated increase in whole cell currents as another test of apparent PIP2 affinity: low-affinity channels should display a significantly greater current increase than high-affinity ones.

The results of this approach for the channels with the most intriguing changes in apparent PIP2 affinity as evidenced from the single-channel recordings are shown in Fig. S4, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200810007/DC1. Because we have no information as to the altered expression of channels in the membrane caused by the mutations, we summarized the data as normalized current density, which is most pertinent. For wt Kv7.2, overexpression of PI(4)5-kinase increased current densities by 2.9 ± 0.3-fold (n = 3), whereas for the Kv7.2 KRR-EEE triple mutant, the increase was 4.3 ± 0.7-fold (n = 11; P < 0.01; Fig. S4 A), consistent with the lowered apparent affinity of the triple mutant seen in the single-channel patches. On the other hand, the Kv7.2 K449E mutation that did not produce noticeably different PIP2 sensitivities in the single-channel experiments displayed increased current densities by overexpression of PI(4)5-kinase, 2.4 ± 0.6-fold (n = 6) that was not larger than that of wt Kv7.2 (Fig. S4 A). For the Kv7.3 K406Q mutant, which displayed a substantial lowered apparent affinity for PIP2 in the single-channel data, there was an increase of current density by PI(4)5-kinase overexpression of 2.1 ± 0.5-fold (n = 3; P < 0.01), significantly greater than that for wt Kv7.3, which was 1.1 ± 0.2-fold (n = 9; Fig. S4 B). Thus, the PI4(5)-kinase assay corroborates the importance of a triad of basic residues that form a cationic cluster in PIP2 interactions, and a secondary interaction site adjacent that likely works in concert to bind to the regulatory PIP2 molecules.

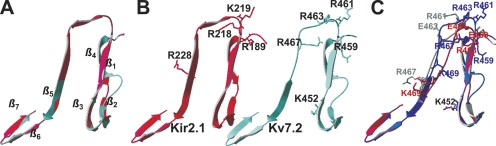

Homology Modeling Suggests a PIP2-binding Pocket in the A-B Helix Linker

In an attempt to gain mechanistic and/or structural understanding of the effect of the Kv7.2 mutations studied here on PIP2 interactions, we performed homology modeling to try to understand the nature of PIP2 binding to this domain. Perhaps the closest analogy to the differential PIP2 sensitivities among Kv7.2-7.4 channels is that of Kir2 (IRK) and Kir3 (GIRK) channels, for which PIP2 has a very high or low apparent affinity, respectively, underlying the constitutive activity of the former but the G-protein activation of the latter (Zhang et al., 1999). The attainment of crystal structures of the regulatory domains of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 channels (Pegan et al., 2005) provides an opportunity for homology modeling of other PIP2-regulated channels using the solved structures as templates. Residues 428–484 of Kv7.2 were aligned against residues 186–245 of Kir2.1, which contain the primary domains conferring PIP2 apparent affinity of both channels (this study; Zhang et al., 1999; Pegan et al., 2005). There is a 31% degree of identical and a 45% degree of conserved residues between these domains. The crystal structure of the Kir2.1 domain shows a loop-like structure, with several residues shown important for PIP2 interactions at the top of the loop (Pegan et al., 2005), where they could make interactions with PIP2 moieties in the membrane (Logothetis et al., 2007; Rosenhouse-Dantsker and Logothetis, 2007). The homology model of the Kv7.2 domain predicts a structure very similar to that of the Kir2.1 domain, comprising seven β-sheets with a loop at the top of the domain. The CαRMS difference between the Kir2.1 and Kv7.2 structures is predicted to be only 0.55 Å. Shown in Fig. 11 (A–C) are superimposed and individual structures of the two domains, with the residues shown in this study to be important for Kv7.2–PIP2 interactions and the corresponding conserved residues of Kir2.1 channels indicated in stick rendering. The model predicts R459 and R461 in Kv7.2, whose charge reversal lowered the apparent affinity of the channel for PIP2, to also be located at the top of the loop, where they could hypothetically be able to interact with membrane PIP2.

Figure 11.

Homology modeling of the helix A-B linker of Kv7.2 based on a domain of Kir2.1 as a template predicts a similar structure. Residues 428–484 of Kv7.2 were modeled using the program Swiss-Model using residues 186–245 of the solved crystal structure of Kir2.1 (Pegan et al., 2005) as a template (see Materials and methods). (A) Shown superimposed are the structure of the Kir2.1 domain (red) with that predicted for Kv7.2 (blue). The seven predicted β-sheets in the Kv7.2 domain are indicated. (B) The two structures are shown individually, with the basic residues identified in this study as being critical for PIP2 interactions with Kv7.2, and the corresponding residues by sequence alignment in Kir2.1 displayed in stick rendering. (C) Shown superimposed are the predicted structures of the wt Kv7.2 linker (blue), the Kv7.2 KRR-EEE triple mutant (red), and the Kv7.2 R463E mutant (gray), with the critical residues displayed in stick rendering. Note the alteration in predicted structure at the top of the linker induced by the mutations.

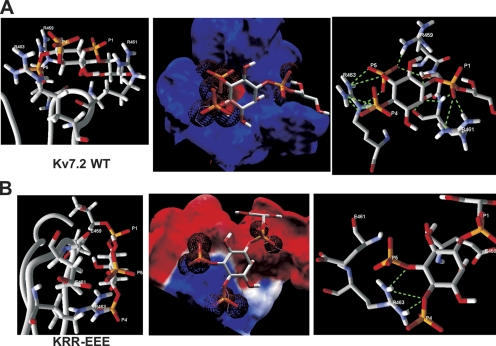

We then used molecule docking and energy minimization modeling to predict the affinities and hydrogen bonds between the head group of PIP2 molecules interacting with the top of the Kv7.2 domain (refer to Materials and methods). Because the extreme flexibility and hydrophobic nature of the full PIP2 acyl chains would preclude meaningful analysis, we used l-α-glycerophospho-d-myo-inositol 4,5-bisphosphate (GPMI-P2) as a docking partner, a PIP2 analogue used in the solved crystal structure of the PIP2-binding transcription factor, tubby (Santagata et al., 2001). Our docking analysis calculates individual hydrogen bond energies, and an overall affinity that takes into account the energy of the electrostatic interaction as well. Although hydrogen bonds can exist between phosphoinositide atoms and those of negatively charged residues (Essen et al., 1997; Thomas et al., 2002), they are outweighed by the repulsive electrostatic force between such molecules, and are not included in depictions of hydrogen bonds (although they are incorporated into the affinity and total hydrogen bond energy calculations). We assumed that the IP3 head group of the GPMI-P2 was flexible and could assume conformations from those parallel to those perpendicular to the membrane (Haider et al., 2007). Fig. 12 A shows a GPMI-P2 molecule docked to the top of the Kv7.2 linker, with the predicted electrostatic profile and the hydrogen bonds predicted shown expanded in the panels. The interaction surface in the Kv7.2 domain is predicted to be mostly electropositive and thus energetically favorable for interaction with the anionic PIP2. The average predicted RMSD between the GPMI-P2 molecule and the channels was 0.77 Å. A total of 14 favorable hydrogen bonds (shown as dotted green lines) are predicted between the GPMI-P2 and the channel residues within range (Table S1, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200810007/DC1). All three negative phosphates are predicted to make intimate contact with positively charged residue atoms. Three bonds are between the P1 phosphate of GPMI-P2 and R461 on the channel. Three are between the P4 phosphate and R463, and three more are between the P5 phosphate and R463 and one more with R459. S460 is also involved, as there is one predicted hydrogen bond between P5 and its hydroxyl group. Interestingly, not only the phosphates, but also the carbons in the inositol ring of the GPMI-P2 head group also participate, with two hydrogen bonds from the C2 carbon to R461 and one to S460. After energy minimization (2,000 iterations), the summed hydrogen bond energy was calculated to be −25.2 kJ/mol and the overall affinity was predicted to be −11.9 kJ/mol. Our next step was to use the same paradigm to predict the effects of mutations that had functional effects on PIP2 apparent affinity. The mutant with the largest reduction in PIP2 apparent affinity was the triple KRR-EEE mutation, and its predicted structure, electrostatic profile, and GPMI-P2 interaction are shown in Fig. 12 B. The structure of the top of the loop of the KRR-EEE mutant is predicted to be altered with less of it in possible apposition to the membrane, including the nonmutated R463, which is predicted to point its two amides not toward the membrane as in the wt, but to the side (Fig. 12 B, left). The average predicted RMSD between the GPMI-P2 molecule and the mutant is increased to 1.31 Å. The negative electrostatic profile keeps the GPMI-P2 from penetrating into the pocket. As a result, the P1 phosphate of the GPMI-P2 has no hydrogen-bonding partners, and the P4 and P5 phosphates are able to make a total of three favorable hydrogen bonds only with R463 (Table S1). Consequently, the overall affinity is predicted to be sharply reduced to −0.71 kJ/mol and the summed hydrogen bond energy to only −1.9 kJ/mol. Thus, the interaction between the KRR-EEE mutant and PIP2 is predicted to be much less energetically favorable in accord with the sharp reduction in maximal Po and in PIP2 apparent affinity for this channel seen in the experimental data.

Figure 12.

Docking simulation of a PIP2 analogue with the helix A-B linker of Kv7.2 predicts an interaction that is strongly weakened by charge-reversal mutations. (A) Left: Shown is an expanded view of the results of the docking simulation of the short-chain PIP2 analogue, GPMI-P2, docked to the top of the wt Kv7.2 helix A-B linker, with the residues with which it is predicted to make interactions indicated. Center: Superimposed are the electrostatic profile of the putative PIP2-interacting surface of the wt Kv7.2 helix A-B linker with GPMI-P2. Blue and red are positive and negative electrostatic surface potentials of more than ±15kT/e, respectively, and the electron density maps of the oxygens of each phosphate group of the GPMI-P2 are shown as red wire spheres. Right: Shown are interactions between GPMI-P2 and the top of the modeled wt linker predicted by the docking simulation. Superimposed are the GPMI-P2 molecule with the residues of the linker with which it makes hydrogen bonds, indicated by dotted green lines. (B) Shown are (left) an expanded view of the results of the docking simulation of GPMI-P2 docked to the top of the KRR-EEE mutant Kv7.2 helix A-B linker, (center) the electrostatic profile of the putative PIP2-interacting surface of the KRR-EEE mutant Kv7.2 helix A-B linker superimposed with GPMI-P2, and (right) interactions between GPMI-P2 and the top of the modeled KRR-EEE mutant linker predicted by the docking simulation. The interacting channel residues and the P1, P4, and P5 phosphates of GPMI-P2 are labeled. Orange, phosphorus; red, oxygen; purple, nitrogen, white, carbon or hydrogen.

Perhaps the most unexpected result from the patch data were the highly differential effects of charge neutralization versus charge reversal of R463 and R467, with the former reducing maximal Po and PIP2 apparent affinity, but the latter increasing it. Indeed, the latter result seems quite unintuitive, given that an acidic residue at this position should make an interaction with anionic PIP2 molecules less favorable. However, the homology modeling and docking analysis provides a satisfying molecular mechanism to explain these results. Fig. 13 A shows the predicted structure of the R463Q mutant, its electrostatic surface, and interaction with GPMI-P2. Its electrostatic surface is only slightly less positive than the wt, and the RMSD is nearly unchanged at 0.68 Å. But due to the more constricted conformation of the top of the channel loop, there are only five predicted favorable hydrogen bonds (Table S2, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200810007/DC1). R461 can make one with the P4 and three with the P5 phosphates, and R459 can make one with the P1 phosphate. Thus, the overall affinity is predicted to be reduced to −6.2 kJ/mol and the summed hydrogen bond energy reduced to −12.6 kJ/mol in accord with the moderate, but significant, reduction in maximal Po and PIP2 apparent affinity observed for this mutant. However, the modeling predicts the R463E mutant to have an interaction with PIP2 that is actually more energetically favorable. Fig. 13 B shows the predicted structure of the R463E mutant, its electrostatic surface, and interaction with GPMI-P2. Due to the altered conformation (more open) of the top of the linker of R463E versus that of the wt, the negatively charged side chain of R463E points away for the GPMI-P2, and so makes a minimal electrostatic contribution. In addition, R434 and R435 are now brought in proximity to the GPMI-P2, where they contribute many favorable interactions. Consequently, the overall electrostatic profile is even more positive than the wt. There are 11 predicted favorable hydrogen bonds (Table S2), one between the P1 phosphate and S460 and two between the P4 and R461. R434 now makes one hydrogen bond with P4 and two with P5, and R435 makes an additional one with P4. As before, the inositol ring carbons can act as hydrogen bond donors, with a bond each between C2 and oxygens in V433 and S460, and a bond each between C3 and a nitrogen in R435 and an oxygen in R461. The overall affinity is predicted to be increased to −15.7 kJ/mol, the summed hydrogen bond energy robustly increased to −32.7 kJ/mol and the RMSD low at 0.84 Å. The predicted increase in the favorability of the interaction is in satisfying agreement with the increased Po, 0 mV and increased PIP2 apparent affinity of this mutant.

Figure 13.

Charge neutralization of R463 and R467 is predicted to weaken channel–PIP2 interactions, but charge reversal is predicted to strengthen them. Shown for (A) R463Q, (B) R463E, (C) R467Q, and (D) R467E are an expanded view of the results of the docking simulation of GPMI-P2 docked to the top of the corresponding helix A-B linker, the electrostatic profile of the putative PIP2-interacting surface of the corresponding helix A-B linker superimposed with GPMI-P2, and interactions between GPMI-P2 and the top of the modeled corresponding mutant linker predicted by the docking simulation. Predicted favorable hydrogen bonds are indicated by dotted green lines. The interacting channel residues and the P1, P4, and P5 phosphates of GPMI-P2 are labeled. All colors and symbols are as in Fig. 11.

The modeling with the R467 mutants resulted in nearly the same picture, with the charge neutralization R467Q predicted to have a weakened interaction with GPMI-P2, but the charge reversal R467E predicted to have a strengthened one. Fig. 13 C shows the predicted structure of the R467Q mutant, its electrostatic surface, and interaction with GPMI-P2. As for R463Q, its electrostatic surface is only slightly less positive than the wt, and the RMSD is nearly unchanged at 0.84 Å, but due to the altered conformation of the top of the channel loop, there are only eight predicted favorable hydrogen bonds (Table S2). R461 can make one each with the P1 and P5 phosphates, and R463 can make two with the P4 and three with the P5 phosphates. The C3 inositol carbon makes one hydrogen bond with the S460 hydroxyl. The overall affinity is predicted to be reduced to −7.2 kJ/mol and the summed hydrogen bond energy reduced to −14.0 kJ/mol in accord with the clear reduction in Po, 0 mV and PIP2 apparent affinity observed for this mutant as well. Again, the modeling predicts the R467E mutant to have an interaction with PIP2 that is more energetically favorable. Fig. 13 D shows the predicted structure of the R467E mutant, its electrostatic surface, and interaction with GPMI-P2. As for the negative charge in R463E, that of R467E is predicted to be buried away from the GPMI-P2 with little impact on the electrostatic surface, which, due now to the proximity of R434 and R435, is again more electropositive than for the wt. The conformation of the top of the loop favors deep penetration of the P4 and P5 phosphates, where they are surrounded by positively charged amino groups. There are 14 predicted favorable hydrogen bonds (Table S2). Two each are between the P4 phosphate and R461 and R463, and two are between the P5 phosphate and R434, with another one each between P5 and R463 and R435. The inositol carbons participate very heavily in the interactions, with C2 predicted to have a hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl of V433, and C6 one with R434. The C3 carbon is predicted to make an astounding four hydrogen bonds, one with S460 and three with R461. The overall affinity is predicted to be increased to −13.4 kJ/mol and the summed hydrogen bond energy increased to −28.5 kJ/mol. Interestingly, the RMSD is increased to 1.45 Å, which may be sufficiently close for a strong interaction, given the high number of predicted bonds. Again, the predicted increase in the favorability of the interaction is in accord with the increased Po, 0 mV and increased PIP2 apparent affinity of this mutant.

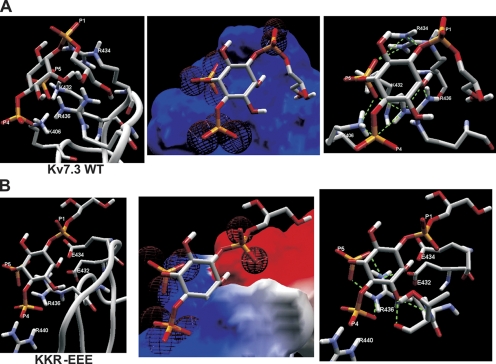

Given that the conserved nature of the residues of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 were identified in the single-channel experiments to be critical for PIP2 interactions, we performed parallel homology modeling with the helix A-B linker of 7.3 and docking simulations with GPMI-P2. When we performed the alignment of the 54-residue core (residues 398–451) of the helix A-B linker of Kv7.3, we found that its sequence was more similar to residues 185–238 of Kir3.1 than to the corresponding domain of Kir2.1 used for the Kv7.2 model. Thus, we used the Kir3.1 domain as a template structure. The CαRMS between the Kv7.3 structural model and the template (Kir3.1) was 0.49 Å for 54 carbon atoms of the aligned amino acids (0.50 Å for 216 backbone atoms). Fig. 14 A shows a GPMI-P2 molecule docked to the top of the Kv7.3 linker, with the predicted electrostatic profile and the hydrogen bonds predicted shown expanded in the panels. The interaction surface in the Kv7.3 domain is predicted to be very highly electropositive and thus energetically very favorable for interaction with the anionic PIP2. The average predicted RMSD between the GPMI-P2 molecule and the channels was only 0.39 Å. A total of 10 favorable hydrogen bonds are predicted between the GPMI-P2 and the channel residues within range (Table S3, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200810007/DC1). As for the wt Kv7.2 docking, all three negative phosphates are predicted to make intimate contact with positively charged residue atoms in the Kv7.3 linker. One bond is between the P1 phosphate of GPMI-P2 and R434 on the channel. The P4 phosphate makes one each with K406 and R436, and the P5 phosphate makes five hydrogen bonds with four different residues. The C2 inositol carbon makes two additional favorable interactions. The summed hydrogen bond energy was calculated to be −30.5 kJ/mol, and the overall affinity was predicted to be −14.1 kJ/mol, which are both more favorable than for wt Kv7.2 in accord with the higher Po, 0 mV of Kv7.3 versus Kv7.2.

Figure 14.

Docking simulation of a PIP2 analogue with the helix A-B linker of Kv7.3 predicts an interaction that is strongly weakened by charge-reversal mutations. (A) Left: Shown is an expanded view of the results of the docking simulation of the short-chain PIP2 analogue, GPMI-P2, docked to the top of the wt Kv7.3 helix A-B linker, with the residues with which it is predicted to make interactions indicated. Center: Superimposed are the electrostatic profile of the putative PIP2-interacting surface of the wt Kv7.3 helix A-B linker with GPMI-P2. Blue and red are positive and negative electrostatic surface potentials of more than ±15kT/e, respectively, and the electron density maps of the oxygens of each phosphate group of the GPMI-P2 are shown as red wire spheres. Right: Shown are interactions between GPMI-P2 and the top of the modeled wt linker predicted by the docking simulation. Superimposed is the GPMI-P2 molecule with the residues of the linker with which it makes hydrogen bonds, indicated by dotted green lines. (B) Shown are (left) an expanded view of the results of the docking simulation of GPMI-P2 docked to the top of the KKR-EEE mutant Kv7.3 helix A-B linker, (center) the electrostatic profile of the putative PIP2-interacting surface of the KKR-EEE mutant Kv7.3 helix A-B linker superimposed with GPMI-P2, and (right) interactions between GPMI-P2 and the top of the modeled KKR-EEE mutant linker predicted by the docking simulation. The interacting channel residues and the P1, P4, and P5 phosphates of GPMI-P2 are labeled. Orange, phosphorus; red, oxygen; purple, nitrogen, white, carbon or hydrogen.

We then performed the docking simulation of the Kv7.3 KKR-EEE triple mutant that displayed sharply lowered Po, 0 mV values (Fig. 14 B). The glutamates at the 432 and 434 positions now present a sharply electronegative profile to the GPMI-P2 molecule, and as a consequence, the P1 phosphate is predicted to make no favorable interactions at all with the channel, and the P5 phosphate is tilted away for any potential interaction partner. The average predicted RMSD between the GPMI-P2 molecule and the KKR-EEE mutant is increased to 0.79 Å. There are a total of seven predicted favorable interactions, of which only three involve the GPMI-P2 phosphates (Table S3). Consequently, the summed hydrogen bond energy is predicted to be reduced to −13.7 kJ/mol, and the overall affinity is predicted to be reduced to −6.3 kJ/mol. Thus, as seen in the KRR-EEE Kv7.2 triple mutant, the interaction between the Kv7.3 KKR-EEE mutant and PIP2 is predicted to be much less energetically favorable than for the wt in accord with the large reduction in Po, 0 mV and in PIP2 apparent affinity for this channel displayed in the experimental data.

Thus, the homology modeling and phosphoinositide docking simulations provide structural hypotheses to explain the mutagenesis results. The results are consistent both for Kv7.2 and Kv7.3, consistent with the conserved cluster of basic residues in the helix A-B linker of both channels being critically implicated in PIP2 interactions. A major finding from the Kv7.2 docking simulations is that the change in the charge of the channel residues in the putative binding pocket does not have results as one might expect simply from the altered charge, but of high importance is the altered configuration of the pocket that alters the specific types and number of residues that can make energetically favorable interactions with the GPMI-P2 molecule. The modeling is nicely in accord with the experimental data.

DISCUSSION

This work deals with the elucidation of the molecular mechanism of PIP2 regulation of membrane transport proteins, a paradigm of signal transduction that grows increasingly widespread in scope (Gamper and Shapiro, 2007). Much effort has gone into determining the site of action of phosphoinositides on channels and transporters, and the molecular determinants conferring favorable interactions. What has emerged is a rather general requirement for a cluster of basic residues interspersed with hydrophobic, aromatic, or even acidic ones (Zhang et al., 1999; Shyng et al., 2000b; Lopes et al., 2002; Prescott and Julius, 2003; Brauchi et al., 2007; Rohacs, 2007). The functional data and accompanying structural models presented here provide mechanistic insights into the unique features of Kv7 channel–PIP2 interactions. Given the nearly widespread localization of phosphoinositide sites of action on many channels within their intracellular C termini, and the C-terminal site of action on M channels of other regulatory molecules, such as Ca2+/CaM, PKC, and Src kinase (Delmas and Brown, 2005), it has been assumed that the site of PIP2 action on M channels would be at the C terminus. This work confirms that assumption. We were able to exploit the highly divergent PIP2-apparent affinities of closely related Kv7 channels by using the chimera approach, much as for the Kir channel family (Zhang et al., 1999). Because exchange of the entire C terminus wholly inverted the divergence among Kv7 isoforms, and exchange of that distal to the start of the B helix inverted none of it, we could focus on the region between the two. Exchange of the C terminus downstream of the beginning of the helix A-B linker inverted most of the divergence, telling us that the prime site of PIP2 action is on the linker, although a more minor part (approximately threefold apparent affinity) remained. This remaining part could arise either from a secondary PIP2 binding site in the A helix (or the A helix may act in concert with the linker domain), or due to differences in coupling efficiency between the PIP2 binding site and the channel gate. In support of the former, a palmitoylated peptide taken from the A helix and introduced into neurons was shown to compete with M channels for PIP2 binding and to depress M current (Robbins et al., 2006), and mutation of a histidine in the A helix of Kv7.2, H328, to a cysteine was shown to result in heteromeric Kv7.2 (H328C)/7.3 channels with a PIP2-apparent affinity reduced by 2.5-fold (Zhang et al., 2003). However, when the above palmitoylated peptide contained the same H328C mutation, the effect on M-current depression was unaltered, arguing against the critical nature of this residue (Robbins et al., 2006). That a major site of PIP2 binding is in the helix A-B linker is strongly corroborated by the severe changes in Po- and PIP2-apparent affinity of the point mutants examined in this study.

The structural motifs of phosphoinositide-binding domains from a variety of proteins, such as the C-terminal domain of the transcription factor tubby, the PTB domain of Dab, the N-terminal domain of CALM, and the PH domain of PLC-δ1, have been analyzed, as have the PIP2-binding domains of ion channels of the Kir, ENaC, TRPM, and TRPV classes (Rosenhouse-Dantsker and Logothetis, 2007). Although a comparison of all of these protein domains reveal relatively poor sequence identities (10–30%), they share a critical structural requirement: a cluster of basic residues facing toward the inner membrane surface producing an electrostatically polarized protein structure that contributes to energetically favorable interactions with phosphoinositides. The analysis reveals a conserved sequence motif for PIP2 binding to PH domains, which is [R/K]–X3-11–[R/K]–X–[R/K]–[R/K], where X is any amino acid (Harlan et al., 1994). The helix A-B linker of Kv7 channels also presents a similar motif, [K452]-[S/P]-X4-[D/N]-[R459/K]-X-[R461]-[F/A]-[R463] (the basic residues of Kv7.2 are numbered), suggesting conserved structural mechanisms. In support of this conclusion, the solved structures of the phosphoinositide-binding modules share the motif of a seven-stranded β-barrel structure, closed off by an α-helix (Ferguson et al., 2000; Lemmon, 2003), with the “lip” of the barrel interacting with the lipid. In the predicted Kv7.2 structure, the PIP2-binding domain is also a seven-stranded β-barrel, bounded by the A and B helices, with the proposed PIP2-binding lip on the loop connecting strands β4 and β5. A core of three basic residues (R459, R461, and R463) on that loop is predicted to form hydrogen bonds mostly with the phosphates of the PIP2 head group. The model predicts mutations of these residues to strikingly affect the structural conformation of the loop and the GPMI-P2 binding, in accordance with the functional data showing profoundly altered PIP2-apparent affinity. The data and modeling suggest a similar structural mechanism to also underlie PIP2 interactions with Kv7.3, and perhaps for the other M-type channels as well.