Abstract

High-resolution structures of bacterial 70S ribosomes have provided atomic details about mRNA and tRNA binding to the decoding center during elongation, but such information is lacking for preinitiation complexes (PICs). We identified residues in yeast 18S rRNA critical in vivo for recruiting methionyl tRNAiMet to 40S subunits during initiation by isolating mutations that derepress GCN4 mRNA translation. Several such Gcd− mutations alter the A928:U1389 base pair in helix 28 (h28) and allow PICs to scan through the start codons of upstream ORFs that normally repress GCN4 translation. The A928U substitution also impairs TC binding to PICs in a reconstituted system in vitro. Mutation of the bulge G926 in h28 and certain other residues corresponding to direct contacts with the P-site codon or tRNA in bacterial 70S complexes confer Gcd− phenotypes that (like A928 substitutions) are suppressed by overexpressing tRNAiMet. Hence, the nonconserved 928:1389 base pair in h28, plus conserved 18S rRNA residues corresponding to P-site contacts in bacterial ribosomes, are critical for efficient Met-tRNAiMet binding and AUG selection in eukaryotes.

Keywords: GCN4 translational control, rRNA, ribosome, scanning, translation initiation

In protein synthesis, each nucleotide triplet in mRNA is decoded by the cognate aminoacyl-tRNA in the aminoacyl (A) site of the ribosome, while peptidyl-tRNA containing the growing polypeptide chain base-pairs with the preceding triplet in the peptidyl (P) site. During initiation, in contrast, the AUG start codon is decoded in the P-site by Met-tRNAiMet. In bacteria, the Shine-Dalgarno sequence in mRNA base-pairs with 16S rRNA to help position the AUG start codon in the P-site. Accurate start codon selection also depends on translation initiation factors IF1, IF2, and IF3, of which IF1 and IF3 stimulate binding of Met-tRNAiMet to the preinitiation complex (PIC) in preference to elongator tRNA species (Antoun et al. 2006). The ribosomal determinants of tRNA binding to the P-site in bacteria are being illuminated by high-resolution crystal structures of 70S ribosomes bound to mRNA with cognate tRNA in the P-site. On the small (30S) subunit, 11 residues of 16S rRNA directly contact the P-site codon, the P-tRNA anticodon, or the P-tRNA anticodon stem–loop (ASL) (Berk et al. 2006; Korostelev et al. 2006; Selmer et al. 2006). In particular, G1338 and A1339 interact with G-C base pairs in the ASL of tRNAiMet, and functional studies have implicated these 16S residues in promoting recruitment of initiator versus elongator tRNA and accurate selection of AUG as start codon (Lancaster and Noller 2005; Qin et al. 2007).

Initiation in eukaryotes is more complex, with 13 different initiation factors (eIFs) participating in a multistep pathway. The eIF2, in its GTP-bound state, forms a ternary complex (TC) with Met-tRNAiMet and binds to the 40S subunit to form the 43S PIC in a manner stimulated by eIF1, eIF1A, eIF5, and eIF3. The 43S PIC then binds to the 5′ end of mRNA, preactivated by eIF4F bound to the cap. The AUG codon is selected as the 43S PIC scans the leader, with the anticodon of Met-tRNAiMet inspecting successive triplets, presumably, as they enter the P-site. eIF1 and eIF1A promote the scanning process at least partly by stabilizing an open conformation of the 40S subunit when non-AUGs occupy the P-site. The GTP bound to eIF2 is hydrolyzed in the scanning complex, dependent on eIF5, but Pi is not released from eIF2-GDP-Pi until AUG occupies the P-site. Base-pairing of Met-tRNAiMet with AUG triggers dissociation of eIF1 from its 40S-binding site, with attendant release of Pi from eIF2-GDP-Pi, to finalize selection of the start codon (Algire and Lorsch 2006; Hinnebusch et al. 2007; Passmore et al. 2007; Pestova et al. 2007).

Although no crystal structures of eukaryotic ribosomes exist, the 3D structure of the eukaryotic 80S ribosome appears to be quite similar to that of bacterial 70S ribosomes. Secondary structure diagrams of eukaryotic 18S and 25S rRNAs differ from their bacterial counterparts primarily in containing expansion segments appended to the conserved core, and most bacterial ribosomal proteins have eukaryotic homologs (Taylor et al. 2007). A molecular model of the evolutionarily conserved 80S core was constructed by docking homologous regions of bacterial rRNA and ribosomal proteins into a cryo-EM density map of an 80S ribosome. The 80S model reveals strong similarities to 70S ribosomes in overall structure, including the inter-subunit space containing the mRNA-binding cleft and decoding sites (Spahn et al. 2004a). In particular, tRNA bound to the 80S P-site appears to interact with certain rRNA helices that contact the P-tRNA anticodon or ASL in bacterial 70S crystals (Spahn et al. 2001a). Hence, good predictions can be made about the locations of specific residues in yeast 18S rRNA that reside in the conserved core of the 40S subunit.

The crystal structures of bacterial 70S ribosomes with tRNAs occupying the decoding sites are thought to provide detailed models of ribosomes in the elongation phase of protein synthesis. High-resolution structures of bacterial PICs or 70S initiation complexes (ICs) are not available, although a cryo-EM reconstruction of a 70S IC suggests a novel orientation for Met-tRNAiMet in the P-site (Allen et al. 2005). In addition, it is reasonable to suppose that initiator binding requires a degree of flexibility to allow inspection of the mRNA and that its orientation could change on start codon recognition or subunit joining (Marintchev and Wagner 2004). Thus, the complete ensemble of 16S rRNA residues required for PIC assembly and accurate AUG recognition is unknown. Moreover, there is almost no information available about the importance of particular residues in 18S rRNA for efficient P-site binding of tRNAiMet and AUG selection during initiation in eukaryotes.

Translation of GCN4 mRNA is a sensitive indicator of the recruitment of eIF2–GTP–Met-tRNAiMet TCs to 40S subunits in yeast cells, and this has been exploited to identify mutations in eIFs that reduce TC assembly or impair TC recruitment in vivo. GCN4 is repressed in amino acid-replete cells by upstream ORFs (uORFs) in the mRNA leader. After translating uORF1, many post-termination 40S subunits can resume scanning and reinitiate translation downstream at uORFs 2, 3, or 4, after which they dissociate from the mRNA and leave the GCN4 ORF untranslated (Fig. 1A). GCN4 translation is derepressed in amino acid-starved cells by phosphorylation of the α-subunit of eIF2 by the kinase GCN2, which inhibits recycling of eIF2-GDP to eIF2-GTP by its GEF, eIF2B. The ensuing reduction in TC concentration allows a fraction of the 40S subunits that have resumed scanning after terminating at uORF1 to ignore the AUGs at uORFs 2–4, continue scanning and reinitiate downstream at GCN4 instead. The GCN4 protein thus produced activates transcription of nearly all amino acid biosynthetic genes to replenish amino acid pools (Hinnebusch 2005b).

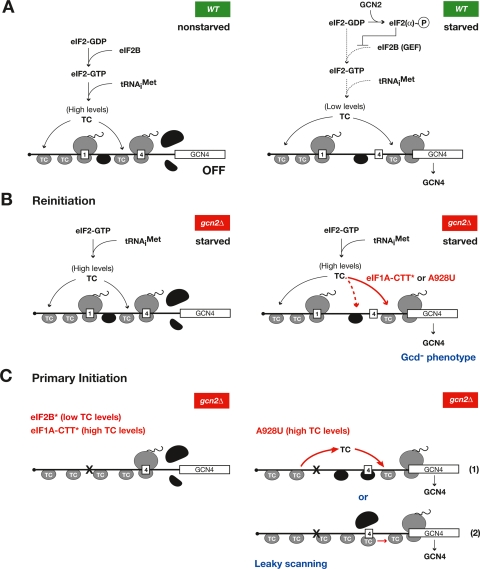

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanisms for derepression of GCN4 translation by mutations affecting eIF1A, eIF2B, or 18S rRNA. (A, left) In wild-type (WT) nonstarved cells, 40S subunits containing TC scan from the 5′ cap and translate uORF1, and post-termination 40S subunits (shaded black) resume scanning and rebind TC (shaded gray) before reaching uORF4. Ribosomes dissociate from the mRNA after terminating at uORF4, leaving the GCN4 ORF untranslated. (Right) In starved cells, phosphorylation of eIF2 reduces TC concentration, so that ≈50% of the post-termination 40S rebind TC after bypassing uORF4 and, hence, reinitiate at GCN4. (B, left) In gcn2Δ cells, GCN4 translation remains repressed in starvation conditions because of high TC levels. (Right) Substitutions in the eIF1A CTT (*) or the rRNA substitution A928U allow post-termination 40S to rebind TC after bypassing uORF4 even at high TC levels by decreasing the on-rate of TC binding, derepressing GCN4 translation. (C, left) eIF2B or eIF1A-CTT mutations that decrease TC abundance or on-rate, respectively, do not allow leaky scanning of uORF4 during primary initiation in constructs lacking uORF1 owing to mutation of its start codon (“x”). (Right) A928U could allow leaky scanning at high TC levels by allowing dissociation and reassociation of TC to 40S subunits as they scan from the cap (1), or perturbing codon–anticodon pairing in the P-site, thus blocking AUG recognition and allowing scanning to resume downstream (2).

Mutations in eIF2B reverse the nonderepressible (Gcn−) phenotype of gcn2Δ cells and permit constitutive derepression of GCN4 translation (Gcd− phenotype) by reducing TC levels, mimicking the effect of eIF2α phosphorylation (Hinnebusch 2005a). The Gcd− phenotype has also been used to identify mutations in eIF1A and eIF1 that impair TC recruitment at the high TC levels present in gcn2Δ cells, including mutations in the C-terminal tail of eIF1A (Fig. 1B, right), which reduce the rate constant for TC loading in vitro (Fekete et al. 2005, 2007; Cheung et al. 2007).

Here we used the Gcd− selection to obtain the first functional evidence for specific residues in 18S rRNA required for efficient TC binding and AUG selection by 40S subunits in vivo. By random mutagenesis of rDNA, we obtained mutations in the residue corresponding to bacterial A928 in conserved helix 28 (h28) that appear to derepress GCN4 translation by reducing the rate of TC loading on post-termination 40S subunits scanning downstream from uORF1 (Fig. 1B, right). Interestingly, such mutations can be distinguished from existing Gcd− mutations in various eIFs because they also greatly increase the bypass, or “leaky scanning,” of AUG codons at uORFs during primary initiation events. The A928 substitutions could allow TC to dissociate from the PIC, or disturb the orientation of Met-tRNAiMet in the P-site in a way that allows AUG to be ignored during the scanning process (Fig. 1C, right). Indeed, our biochemical studies reveal defects in both the association rate and stability of TC binding to 40S subunits conferred by the nonlethal A928U substitution.

The A928:U1389 base pair in helix 28 is not conserved in bacteria (replaced by G928:C1389) and was not previously implicated in P-site binding of tRNA; however, h28 contains a “bulge” residue, G926, which directly contacts the P-site codon in the crystal structures of bacterial 70S elongation complexes. Hence, we went on to mutate G926 and other residues that contact the P-site tRNA anticodon (C1400) or ASL (G1338, A1339) in the bacterial 70S crystal structures and found that many such mutations also confer Gcd− phenotypes and increased leaky scanning. Together, our results implicate a novel residue of h28 and a subset of residues making direct contacts with P-site tRNA in bacterial 70S elongation complexes in the stable anchoring of Met-tRNAiMet to the P-site and efficient AUG recognition during scanning by eukaryotic PICs. They also provide the first in vivo evidence that start codon selection by the scanning eukaryotic PIC occurs in the 40S P-site.

Results

Selection of h28 mutations that derepress GCN4 translation by increasing leaky scanning of the uORFs

To identify mutations in 18S rRNA that impair TC binding to 40S subunits in vivo, we used error-prone PCR to mutagenize the 18S rRNA coding sequences of an rDNA repeat expressed from its native promoter (RDN) on a high-copy LEU2 plasmid. Mutagenized libraries were introduced into the rdnΔ gcn2Δ strain HD2004 lacking chromosomal RDN repeats and harboring a high-copy URA3 plasmid with an RDN allele driven by the galactose-inducible GAL7 promoter (pGAL7-RDN+). Transformants were plated on glucose medium (to repress pGAL7-RDN+) supplemented with sulfometuron methyl (SM), an inhibitor of Ile/Val biosynthesis, to select for RDN mutations on the LEU2 plasmid with Gcd− phenotypes. gcn2Δ cells cannot grow on SM medium owing to the inability to derepress GCN4 translation and increase transcription of Ile/Val biosynthetic genes. Gcd− mutations in the RDN LEU2 plasmid should allow gcn2Δ cells to grow on SM medium by constitutively derepressing GCN4 translation (Fig. 1B, right).

After selecting SMR (resistant to SM) transformants, rescuing the LEU2 RDN plasmids, and retransforming strain HD2004 with purified plasmids, we identified 10 different plasmid-borne Gcd− RDN alleles. Remarkably, sequence analysis revealed mutations within, or close to, h28 in all 10 alleles. Seven contained mutations A1151C, A1152T, or A1152C at two adjacent residues in the top strand of h28, while the eighth contained T1627C on the bottom strand, disrupting the same base pair disrupted by A1151C (Fig. 2A, middle panel). The remaining two plasmids contained the mutation A1143T or C1158T, only 6–8 nucleotides (nt) from the residues mutated in the top strand of h28. Because h28 is largely conserved between eukaryotic 18S and bacterial 16S rRNA (http://www.ma.icmb.utexas.edu), we included the residue numbers for Escherichia coli 16S rRNA in Figure 2A [e.g., 1152(928)], and henceforth identify the mutations using bacterial numbering alone [e.g., A928T in DNA or A928U in rRNA for the A1152(928)T mutation]. Because the SMR RDN alleles with A927C or A928T contained additional mutations, we used site-directed mutagenesis to create RDN LEU2 plasmids bearing only these single mutations and found that they conferred SMR phenotypes indistinguishable from the original alleles (data not shown). The SMR phenotypes conferred by single mutations at each residue, after evicting the pGAL7-RDN+ URA3 plasmid by growth on 5-fluoroorotic acid (plasmid-shuffling), are shown in the right-hand panel of Figure 2A, and subsequent experiments involved these mutant strains.

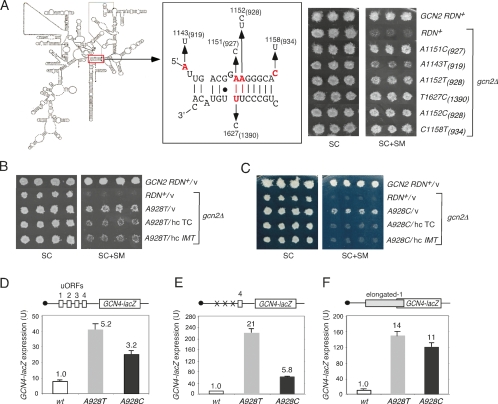

Figure 2.

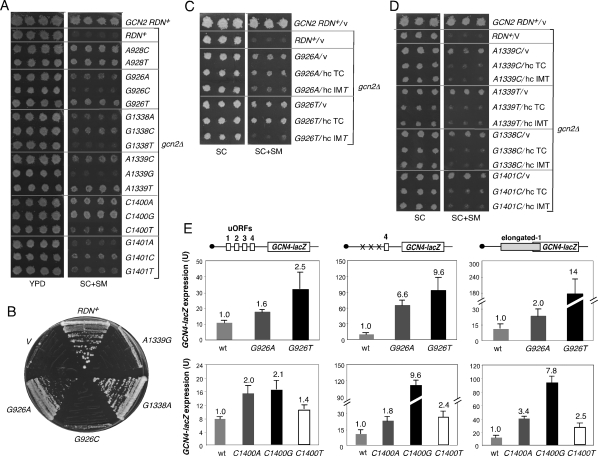

Gcd− mutations affecting h28 derepress GCN4 translation and confer leaky scanning of single uORFs. (A, left) Secondary structure of yeast 18S rRNA with h28 boxed. (Middle) h28 showing Gcd− substitutions at the indicated residues. (Right) Parental GCN2+ strain NOY908 (top row) and derivatives of gcn2Δ strain HD2004 (row 2) with the indicated RDN alleles on LEU2 plasmids after eviction of the pGAL7-RDN+ URA3 plasmid—namely, HD949, HD797, HD930, HD878, HD891, and HD800 (rows 3–8)—were replica-printed to synthetic complete medium lacking Leu (SC) or SC lacking Leu, Ile, and Val and containing 0.3 μg/mL SM (SC + SM) and incubated for 3 d. Residues are designated by positions in both yeast 18S and (in parentheses) E. coli 16S rRNAs. Only E. coli numbering is used in all subsequent figures. (B,C) Wild-type or A928T/C mutants from A harboring empty vector (v), hc TC plasmid p3000, or hc IMT4 plasmid p2996 were analyzed for SM resistance as in A. (D–F) Three or more independent transformants of wild-type or A928T/C mutants from A harboring the GCN4-lacZ reporters (shown schematically) on plasmids p180 (D), p226 (E), or p4164 (F) were cultured for 14–20 h in SC to an OD600 of 1.0–1.2, and β-galactosidase activities were measured in cell extracts as nanomoles of o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside cleaved per minute per milligram (min−1 mg−1). Averages and standard errors are plotted.

If the SM resistance of these mutants results from constitutive derepression of GCN4 translation (the Gcd− phenotype), they should exhibit two key properties. Their SMR phenotypes should be diminished by overexpressing tRNAiMet from a high-copy plasmid (hc IMT), or by co-overexpressing tRNAiMet together with the three subunits of eIF2 from the same plasmid (hc TC), as a means of increasing the cellular concentration of TC (Fekete et al. 2007). Second, the mutations should derepress expression of a GCN4-lacZ fusion containing the four uORFs in the gcn2Δ background under nonstarvation conditions, where the normal derepression mechanism involving eIF2α phosphorylation is absent. Both criteria were met for the A928T and A928C mutations, whose SMR phenotypes were partially suppressed by hc IMT and hc TC (Fig. 2B,C), and which increased GCN4-lacZ expression in nonstarved gcn2Δ cells by threefold to fivefold (Fig. 2D). (The SMR phenotype of A919T was suppressed by hc IMT; however, we did not analyze this mutant further because of its weaker phenotype.) The A927C, T1390C, and C934T mutations also derepressed GCN4-lacZ expression (Supplemental Fig. S1A); however, their SMR phenotypes were not suppressed by hc IMT or hc TC (data not shown). This suggests that these mutations allow reinitiating ribosomes to bypass the uORF4 AUG in a manner not rectified by increasing TC levels in the cell. For example, they might impede the recognition of codon–anticodon pairing in the P-site and prevent the cessation of scanning that normally occurs at AUG start codons. In this study, we focused our attention on the A928T and A928C mutations, which likely produce Gcd− phenotypes by reducing the rate of TC loading on 40S subunits.

We asked next whether the derepression of GCN4-lacZ expression by the A928T and A928C mutations requires multiple uORFs in the mRNA leader. We showed previously that the reduction in TC levels evoked by eIF2α phosphorylation in wild-type cells, or by Gcd− mutations in eIF2B in gcn2Δ cells, only weakly derepresses GCN4-lacZ expression when uORF4 is present alone in the leader, as uORF1 is also required upstream for strong derepression under these conditions (Fig. 1C, left). This was the key evidence that a decrease in the rate of TC loading allows a substantial fraction of 40S subunits to bypass uORF4 only during reinitiation after completing translation of uORF1. Such 40S subunits reacquire TC after bypassing the uORF4 AUG and reinitiate at GCN4 instead (Fig. 1A). The uORF4 AUG is skipped infrequently during primary initiation events—i.e., when present as the first AUG from the 5′ end in constructs lacking uORFs 1–3—presumably because 40S subunits bind TC before the resulting 43S PIC begins scanning from the cap, and TC does not dissociate from scanning PICs, even at low TC levels (Fig. 1C, left; Hinnebusch 2005a).

In contrast to these previous observations, the A928C and A928T mutations produce sixfold to 21-fold higher GCN4-lacZ expression from a construct containing uORF4 alone (Fig. 2E). Importantly, these mutations have little effect (less than twofold) on expression of a GCN4-lacZ construct lacking all four uORFs (data not shown), ruling out the possibility that the A928U substitution increases GCN4 expression at the transcriptional level (Abastado et al. 1991). These findings suggest that the A928 substitutions impair recognition of the uORF4 AUG—i.e., permit leaky scanning—even during primary initiation events (Fig. 1C, right).

In wild-type cells, there is almost no reinitiation after uORF4 translation, accounting for the fact that the presence of uORF4 alone reduces GCN4-lacZ expression by ∼99% compared with that seen with no uORFs present (Abastado et al. 1991). However, it was possible that the A928 substitutions permit ribosomes to reinitiate more efficiently after translation of uORF4 rather than allowing leaky scanning past the uORF4 AUG. To rule this out, we examined a GCN4-lacZ construct containing an elongated version of uORF1 that was moved into the position of uORF4 so that it terminates 130 nt downstream from the GCN4 AUG. Reinitiation after elongated uORF1 is prevented by its extended length and because ribosomes would have to scan backward past four AUGs to reach the GCN4 start codon after terminating at the elongated uORF1 stop codon (Abastado et al. 1991). The A928 substitutions conferred ≈10-fold higher GCN4 expression from the elongated uORF1 construct (Fig. 2F), providing strong evidence that they increase leaky scanning during primary initiation events rather than enhancing reinitiation after uORF termination events. The A927C and T1390C mutations, which disrupt the A927:U1390 base pair in h28, and the C934T mutation likewise increase expression from the GCN4-lacZ constructs with single uORFs (Supplemental Fig. S1B,C), suggesting that they too allow leaky scanning during primary initiation.

Disrupting the 928:1389 base pair in particular ways confers leaky scanning of the GCN4 uORFs

We sought next to determine whether the Gcd-/SMR phenotypes of the A928 substitutions result from substitution of A928, disruption of the A928–U1389 base pair, or both alterations. We used site-directed mutagenesis to introduce the T1389A mutation on the bottom strand of h28 in the wild-type RDN allele to disrupt the A928–U1389 base pair in a different way, and also in the A928T allele to restore base-pairing at this position (Fig. 3A). The T1389A single mutation produced a weak SMR/Gcd− phenotype (Fig. 3A) that was partially suppressed by hc IMT (data not shown). It also resembled the A928 mutations by increasing the leaky scanning past uORF4 and elongated uORF1, although the latter defects were less pronounced than for A928T on the upper strand of h28 (Fig. 3C). Importantly, the double mutant showed wild-type sensitivity to SM (Fig. 3A) and lower levels of GCN4-lacZ expression from both single-uORF reporters compared with the cognate single mutants (Fig. 3C). Thus, restoring the 928–1389 base pair fully suppressed the pronounced Gcd− and leaky-scanning phenotypes of the A928T mutation.

Figure 3.

Compensatory mutations that restore the 928:1389 base pair suppress the Gcd− phenotypes of A928T/C mutations. (A,B) Compensatory mutations affecting h28 are depicted schematically; the gcn2Δ strains HD2006, HD930, HD886, and HD792 were analyzed for SM resistance. (C,D) Expression of the indicated reporters was measured in strains from A and B as in Figure 2. (E) Transformants of strain JD1314 harboring the indicated pTET-RDN alleles or empty vector YEp24 (v) were streaked on rich glucose medium (YPD) lacking tetracycline, to repress the resident pGAL7-RDN+ allele. All strains grew as the pTET-RDN+ strain on YP-galactose medium (not shown). (F,G) Purified 80S ribosomes from the gcn2Δ strains from A were subjected to primer extension analysis using primers 5′-GCAGGCTCCACTCCTGGTGGTG-3′ (F) and 5′-ACTAGCGACGGGCGGTGTGTAC-3′ (G) and the indicated combinations of deoxy- and dideoxyribonucleotides. The predicted extension products for wild-type (wt) and mutant (m) 18S rRNAs are depicted schematically, terminating at the blue dots. (p) Primer.

We obtained similar results from analysis of the A928C mutation and the compensatory mutation on the lower strand, T1389G, which restores base-pairing at this position in h28. Thus, whereas T1389G alone elicits a Gcd− phenotype that is partially suppressed by hc IMT and increases leaky-scanning, this mutation suppresses the corresponding, stronger phenotypes conferred by A928C in the double mutant (Fig. 3B,D; data not shown). The results in Figure 3, A–D show that the Gcd− and leaky-scanning defects conferred by A928T and A928C result from disrupting the A928–U1389 base pair, as changing the identity of residue 928 has little effect when the 928:1389 base pair is reconstituted in the double mutants. However, the A928T and A928C mutations, which disrupt the base pair and leave unpaired pyrimidines on both strands, provoke stronger Gcd− phenotypes than do T1389A and T1389G, which leave unpaired purines at the same position of h28 (Fig. 3A,B).

In the course of this work, we discovered that the A928C single mutant contains a mixture of A928C and (wild-type) RDN+ LEU2 plasmids (data not shown), indicating that its SMR/Gcd− phenotype is dominant. The RDN+ LEU2 recombinant plasmids we recover from the A928C mutant were likely produced by gene conversion of the RDN-A928C allele by pGAL7-RDN+ before the pGAL7-RDN+ URA3 plasmid was evicted by plasmid shuffling. There is strong selection for such recombinants to reduce the proportion of mutant ribosomes in strains harboring highly deleterious RDN mutations. Dinman and colleagues have devised a method to minimize recombination by silencing transcription of the mutant RDN allele, by expressing it from a tetracycline-repressible promoter and growing cells with tetracycline. The function of the mutant allele is then tested on glucose medium lacking tetracycline to shut off the resident pGAL7-RDN+ wild-type allele and derepress the mutant pTET-RDN allele (Rakauskaite and Dinman 2006). Below, we refer to this genetic assay as the pTET-RDN system.

Analysis of the A928 mutations in the pTET-RDN system confirmed that A928C is lethal, as the relevant mutant does not grow on rich glucose medium lacking tetracycline but grows like wild type on rich galactose medium. In contrast, the A928C-T1389G double mutant, containing the compensatory mutation that restores base-pairing, grows like wild type on both media (Fig. 3E). Thus, restoring the 928-1389 base pair suppresses the recessive-lethal phenotype, as well as the dominant SMR/Gcd− and leaky-scanning phenotypes (detected in the gcn2Δ strain) of A928C. The A928T mutation, in contrast, is not lethal in the pTET-RDN system, but confers a slow-growth (Slg−) phenotype that is fully suppressed by the T1389A mutation that restores the 928-1389 base pair (Fig. 3E). Supporting our conclusion that A928T is not lethal, we never recovered an RDN+ LEU2 recombinant plasmid from the A928T mutant.

We wished to address biochemically the prediction that the A928T mutant contains primarily, if not entirely, mutant 40S subunits. Hence, we purified 80S ribosomes from the gcn2Δ strains described above (Fig. 3A) containing A928T, T1389A, or the double mutation A928T-T1389A that restores base-pairing at this position in h28. Extracted rRNAs were subjected to primer extension analysis in reactions containing one of four dideoxyribonucleotides (ddN) designed to produce extension products of different lengths from mutant versus wild-type rRNA. Reactions templated by the upper strand of h28 in reactions with ddATP produced the product of predicted length (37-mer) using ribosomes from the wild type or the T1389A single mutant, which lacks a mutation in this strand. In contrast, ribosomes from the A928T mutant and A928T-T1389A double mutant gave almost exclusively the shorter (30-mer) product predicted for the A928T mutation on the upper strand (Fig. 3F). Analogous results were obtained from reactions templated by the bottom strand of h28 for the same four ribosome preparations (Fig. 3G). Quantification of the extension products by PhosphorImaging indicates that the proportion of wild-type 18S rRNA in ribosomes from the A928T and A928T-T1389A mutants is ≤0.05. Thus, while a small fraction of 40S subunits may contain the A928U substitution, these mutants clearly survive with most 40S subunits harboring mutant 18S rRNA. Using the same techniques, we found that ribosomes from the A928C-T1389G double mutant (Fig. 3B) do not contain detectable 18S rRNA containing the wild-type residue U1389 on the bottom strand (data not shown), consistent with our conclusion that this double mutation also is viable.

It may seem puzzling that the Gcd− mutations A927C, T1390C, and C934T generally produced smaller increases in GCN4-lacZ expression (Supplemental Fig. S1A–C) but had stronger SMR/Gcd- phenotypes, compared with the A928T mutation (Fig. 2A). This might reflect the fact that the former mutations are lethal, and we found that >50% of the LEU2 plasmids rescued from the mutant strains contain the wild-type RDN allele (data not shown). The presence of wild-type 40S subunits in these strains should dampen the induction of GCN4-lacZ expression. Their stronger SMR phenotypes could be explained by proposing that cells with a higher proportion of mutant RDN plasmids outgrow other cells with a lower proportion of mutant plasmids, yielding an apparent level of SM resistance greater than exists in the starting population. This phenomenon would not occur for the A928T strain because it contains almost exclusively mutant plasmids.

The A928U substitution specifically impairs TC binding to 43S and 48S PICs in a purified system

Having shown that the A928T mutant contains largely mutant 18S rRNA, we examined the ability of the mutant 40S subunits to load TC in vitro. The 40S subunits were purified in parallel from wild-type and A928T cells and analyzed by primer extension to verify the presence of A928U in the mutant subunits (Fig. 4E), as described above. (In the course of this experiment, we also noted that A928T cells contain essentially wild-type levels of 40S subunits, as judged by sedimentation of the ribosomal species in cell extracts through sucrose gradients [data not shown]—ruling out a significant effect of the mutation on 40S biogenesis or stability.) The dissociation constant (Kd) for TC in 43S⋅mRNA complexes was then determined by equilibrium binding of preassembled TC at different concentrations of the 40S subunits in the presence of saturating amounts of purified eIF1, eIF1A, and mRNA containing an AUG codon. We observed that the Kd for TC is >10-fold higher for the A928U mutant compared with wild-type 40S subunits (Fig. 4A,F, second column). A similar decrease in the affinity of TC for the mutant subunits was observed in complexes containing UUG as the start codon (data not shown). Previously, we showed that the Kd is >100-fold higher for wild-type 40S subunits in assays conducted without mRNA, owing to loss of thermodynamic coupling between the AUG and anticodon of tRNAiMet (Kapp et al. 2006). In the absence of mRNA, the A928U substitution increases the Kd for TC by only approximately threefold (Fig. 4C,F, fourth column). Thus, A928U reduces the affinity of TC both in the presence and absence of mRNA, but the mutation has a more pronounced effect with mRNA present.

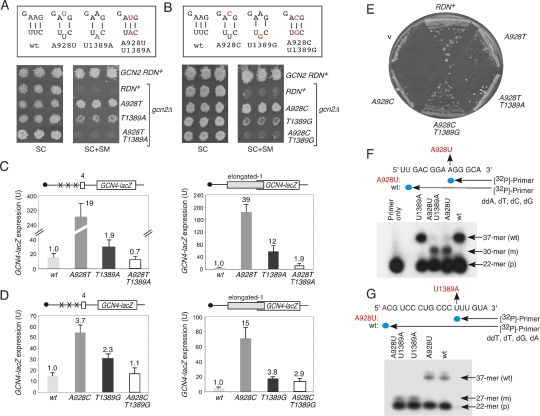

Figure 4.

The A928U substitution in 18S rRNA reduces the rate of TC loading and the affinity of TC for 40S subunits in reconstituted PICs. (A) Preformed TC containing [35S]-Met-tRNAiMet was incubated with wild-type or A928U purified 40S subunits, eIF1A, eIF1, with or without a model mRNA (as indicated in each panel), and the fraction of labeled [35S]-Met-tRNAiMet bound to 40S subunits was measured using a native gel assay. (A,C) Reactions were carried out for 90 min at different 40S subunit concentrations. (B,D) Reactions were carried out with 20 or 750 nM 40S subunits (with and without mRNA, respectively) for varying times. (E) Primer extension analysis of purified 40S subunits as in Figure 3F. (F) Kd values and rate constants (kobs) for TC binding to 40S subunits calculated from data in A and B and C and D, respectively.

We also compared the kinetics of TC loading on 43S⋅mRNA complexes containing A928U mutant versus wild-type 40S subunits. In the presence of mRNA, the rate constant (kobs) was reduced by a factor of ≈5 for the mutant versus wild-type subunits (Fig. 4B,F, third column). In PICs lacking mRNA, the rate constant is ≈20-fold lower for wild-type subunits compared with PICs containing mRNA, as observed previously. In this situation, the A928U substitution reduces the kobs relative to wild-type subunits only by a factor of ≈2 (Fig. 4D,F, fifth column). Thus, A928U lowers the rate of TC loading on 40S subunits in the presence or absence of mRNA, but the effect is greater with mRNA present.

Because TC loading on the 40S is stimulated by eIF1 (Algire et al. 2002), which binds near the P-site (Lomakin et al. 2003), it was important to determine whether A928U reduces the affinity of this initiation factor for the 40S subunit. At odds with this possibility, we found that A928U mutant subunits bind eIF1 with nearly the same affinity as do wild-type subunits. The A928U subunits also support efficient thermodynamic coupling between eIF1 and eIF1A, as eIF1A increases the affinity of eIF1 for 40S subunits equally well for mutant and wild-type subunits (Supplemental Fig. S2A,B). These findings indicate that A928U does not have a significant effect on eIF1 binding during PIC assembly, consistent with the notion that the mutation alters the P-site in a manner that specifically impairs interaction with TC.

Mutations in 18S rRNA residues corresponding to bacterial P-site contacts also derepress GCN4 and confer leaky scanning

High-resolution crystal structures of Thermus thermophilus 70S ribosomes complexed with mRNA and tRNAs have provided atomic details of interactions made by 16S rRNA residues in the P-site with the codon, anticodon, or ASL of tRNA (Korostelev et al. 2006; Selmer et al. 2006). Although these 70S structures are regarded as models of elongation complexes, we used them to consider how mutations in h28 might affect P-site binding of tRNAiMet in yeast PICs. h28 constitutes the neck connecting the head and body of the 30S subunit (Fig. 5A, left) and is the pivot point for rotation of the 30S head relative to the body that is thought to accompany tRNA binding (Schuwirth et al. 2005; Korostelev et al. 2006). Furthermore, h28 is very close to the P-site, and the “bulge” nucleotide in h28, G926, contacts the P-site codon (Fig. 5A, right). The N1 and N2 positions of the guanine ring of G926 form H-bonds with phosphate 1 of the P-codon (Korostelev et al. 2006). The Gcd− mutations we isolated at positions 927, 928, and 1390 alter the two base pairs immediately adjacent to G926 (Figs. 2A, 5A,B) and, hence, might impair the ability of G926 to H-bond with the AUG codon in 48S PICs. Alternatively, substituting these h28 base pairs could indirectly perturb one or more additional contacts made by other rRNA residues with the AUG or tRNAiMet, some of which are depicted in Figure 5, B and C.

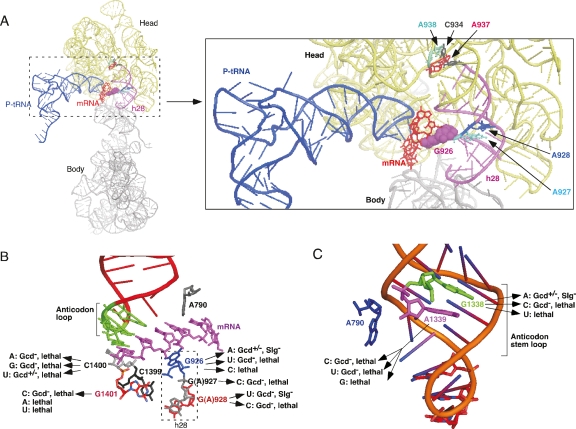

Figure 5.

Substituting residues predicted to contact the P-site tRNA or P-codon confers Gcd− phenotypes in yeast. (A–C) Contacts between G926 of h28 (A,B) and certain other rRNA residues in the P-site (B,C) with the P-site codon or tRNA as visualized in the crystal structure of the T. thermophilus 70S ribosome containing a model mRNA and tRNAs bound to the P- and E-sites (Korostelev et al. 2006). The schematics were constructed using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org) and pdb file 2ow8. The phenotypes of selected mutations in yeast are summarized in B and C. Lethal mutations without dominant Gcd− phenotypes were not designated Gcd+ because the mutant 40S subunits may not occur at sufficient levels to affect GCN4 translation. See text for other details.

To pursue these possibilities, we tested site-directed mutations of G926 for Gcd− phenotypes in the gcn2Δ strain, and also for lethality in the pTET-RDN system, as described above for the random mutations. Replacing G926 with either pyrimidine is lethal (Fig. 6B; data not shown), and G926T confers a strong dominant SMR/Gcd− phenotype (Fig. 6A), comparable with that of the A928 substitutions discussed above. Although the lethal G926C mutation does not confer a dominant SMR/Gcd− phenotype, the proportion of mutant ribosomes might be too low to affect GCN4 translation in the gcn2Δ strain harboring this allele. The G926A mutation, in contrast, is viable and confers Slg− (Fig. 6B) and modest SMR/Gcd− phenotypes (Fig. 6A). These findings fit with the possibility that H-bonding of G926 to the P-site codon is conserved in eukaryotes, as both H-bonds would be lost with U or C replacements, but only the H-bond at N2 would be eliminated by the A substitution (Korostelev et al. 2006). The SMR/Gcd− phenotypes of both G926A and G926T are suppressed by hc IMT (Fig. 6C), consistent with weakened tRNAiMet binding to the P-site, but, interestingly, neither mutation is suppressed by hc TC. We discuss below a possible explanation for this unique phenotype. The G926A and G926T mutations also resemble the A928 mutations by increasing leaky scanning of uORF4 and elongated uORF1, with the lethal G926T substitution showing the stronger effect of the two (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

Substituting predicted P-site residues confers Gcd- and leaky scanning phenotypes. (A) gcn2Δ strains with the indicated RDN alleles, after eviction of the pGAL7-RDN+ URA3 plasmid, were analyzed for SM resistance as in Figure 2. (B) Strains harboring the indicated pTET-RDN alleles or empty vector were streaked on YPD lacking tetracycline; all strains grew as the pTET-RDN+ strain on YP-galactose (not shown). (C,D) strains from A with empty vector (v), p3000 (hc TC), or p2996 (hc IMT) were analyzed for SM resistance. (E) Expression of the indicated reporters was measured in strains from A as in Figure 2.

We proceeded to examine substitutions at residues corresponding to C1400 and G1401, because in bacterial 70S crystals the (methylated) base m5C1400 stacks on the P-tRNA wobble base, while G1401 interacts with the P-codon via a metal ion (Fig. 5B; Korostelev et al. 2006; Selmer et al. 2006). We observed SMR/Gcd− phenotypes for all three mutations at C1400 and for G1401C (Fig. 6A), which were judged to be dominant because all four mutations are lethal in the pTET-RDN system. G1401C resembles A928 mutations in that its SMR/Gcd− phenotype is suppressed by hc IMT and hc TC (Fig. 6D) and, thus, most likely impairs tRNAiMet binding to the P-site. The three C1400 mutations, in contrast, resemble the A927 and U1390 mutations in showing little or no suppression by hc IMT or hc TC (data not shown). Because they increase leaky scanning of uORF4 and elongated uORF1 (Fig. 6E), however, the C1400 mutations also impair start codon recognition during scanning.

Residues G1338/A1339 and A790 interact with different sides of the ASL of the P-tRNA in the 70S crystal structures (Fig. 5C) and appear to comprise a “gate” separating the P-site from the E-site (Korostelev et al. 2006; Selmer et al. 2006). G1338/A1339 exhibit A-minor interactions with base pairs G29:C41 and G30-C40 in the minor groove of the ASL. Together with G31-C39, the latter comprise three consecutive G-C base pairs unique to the initiator. There is evidence that the A-minor interactions of G1338/A1339 with the ASL promote the efficiency of initiation and fidelity of AUG start codon selection in E. coli (Lancaster and Noller 2005; Qin et al. 2007). We found that substituting G1338 with C or T is lethal, and that the C substitution confers a dominant SMR/Gcd− phenotype (Fig. 6A) that is suppressible by hc IMT and hc TC (Fig. 6D). In contrast, the G1338A mutation produces only a weak SMR/Gcd− phenotype (Fig. 6A), and this mutant grows nearly like wild type in the pTET-RDN system (Fig. 6B). In contrast, all three substitutions at A1339 are lethal (Fig. 6B; data not shown), and the C and T mutations produce dominant SMR/Gcd− phenotypes (Fig. 6A) suppressible by hc IMT and hc TC (Fig. 6D). (Again, the fact that lethal mutations A1339G and G1338T do not produce SMR/Gcd− phenotypes could arise from a low proportion of wild-type ribosomes in these strains.) The three SMR/Gcd− mutations at residues 1338 and 1339 increase leaky scanning of both uORF4 and elongated uORF1 (Supplemental Fig. S3). Our finding that multiple mutations at G1338 and A1339 confer Gcd− phenotypes suppressible by hc TC support the idea that interactions of these two 18S residues with the ASL of tRNAiMet promotes initiator binding and AUG recognition in yeast.

In bacterial 70S ribosomes, G1338 and A1339 participate, respectively, in type II and type I A-minor interactions with G29:C41 and G30-C40 in the ASL of P-site tRNA. Our finding that all three substitutions at A1339 are lethal fits with the known requirement for adenine in type I A-minor interactions, as even the G substitution nearly abolishes translation in E. coli cells (Abdi and Fredrick 2005; Lancaster and Noller 2005). In contrast, A can substitute for G at 1338 in E. coli with little impairment of ribosome function (and A is capable of type II interactions), whereas both pyrimidine substitutions are highly detrimental. Thus, our findings on G1338 are concordant with the results from E. coli, as both pyrimidine substitutions are lethal in yeast cells, whereas the A substitution is viable and produces only a weak Gcd− phenotype.

Discussion

By isolating Gcd− mutations affecting 18S rRNA, we obtained the first functional evidence for specific nucleotides that participate in recruitment of TC or in AUG recognition by eukaryotic PICs in vivo. Selection of Gcd− alleles from randomly mutagenized 18S rDNA identified mutations in h28, most of which affect the base pairs corresponding to A927:U1390 and A928:U1389 in bacterial 30S subunits. The SMR/Gcd− phenotypes conferred by the A928U and A928C substitutions were suppressed by overexpressing tRNAiMet (or co-overexpressing all components of TC), a hallmark of Gcd− mutations that reduce the rate of TC loading on 40S subunits (Fekete et al. 2005, 2007; Cheung et al. 2007). Consistent with this, 40S subunits purified from the A928U mutant exhibit a fivefold reduced rate constant (kobs) for TC loading in reactions containing mRNA, eIF1A, and eIF1. Accordingly, we propose that the A928 mutations (and probably other site-directed P-site mutations with Gcd− phenotypes suppressed by hc IMT) derepress GCN4 translation at least partly by decreasing the rate of TC loading on reinitiating 40S subunits scanning downstream from uORF1 (Fig. 1B, right).

Using the pTET-RDN genetic system developed by Dinman et al. we found that the A928C mutation is lethal. Consistent with this, the A928C mutants isolated in our original strain contain a mixture of LEU2 plasmids with wild-type or mutant RDN alleles, presumably generated by recombination with the pGAL7-RDN+ URA3 plasmid prior to its eviction. This implies that the Gcd− phenotype of A928C (and all other lethal Gcd− alleles we uncovered) is dominant. Although we did not quantify the mutant:wild-type ratio of 40S subunits in the lethal mutants, the dominance of their Gcd− phenotypes implies that the mutant subunits are capable of competing with wild-type 40S subunits for PIC assembly and scanning on GCN4 mRNA. Dominance can be readily understood by noting that the increased ability of mutant 40S subunits to bypass uORFs 2–4 and reinitiate at GCN4 should be unaffected by the presence of wild-type 40S subunits on the same transcript, as the latter will simply reinitiate at uORFs 2–4 and then dissociate from the mRNA.

It is striking that the A928 substitutions evoke a strong increase in leaky scanning of both uORF4 and elongated uORF1 in GCN4-lacZ constructs containing these solitary uORFs; i.e., during primary initiation events. This was not seen previously for Gcd− mutations in eIF2B subunits, or in response to eIF2α phosphorylation in wild-type cells, all of which lower the concentration of TC. The latter Gcd− mutations derepress the wild-type GCN4-lacZ fusion containing all four uORFs by fivefold to 10-fold greater amounts than they derepress the construct with uORF4 alone (Mueller et al. 1987; Williams et al. 1989). This shows that a decrease in TC levels evokes frequent bypass of the uORF4 AUG only during reinitiation events, when post-termination 40S subunits must rebind TC in the time it takes to scan from the uORF1 stop codon to uORF4. Presumably, merely reducing TC levels does not elicit leaky scanning during primary initiation because TC binds to the 40S before the resulting 43S PIC interacts with the 5′ end of the mRNA (albeit more slowly), and TC rarely dissociates as the PIC scans the leader. In contrast, the A928 Gcd− mutations increase GCN4-lacZ expression by a greater amount from the solitary-uORF constructs than from that containing all four uORFs. This implies that the A928 mutations don’t simply reduce the rate of TC reloading on scanning 43S PICs during reinitiation in the manner described previously for other Gcd− mutations.

The novel leaky-scanning phenotype of A928 mutations might be explained by our finding that A928U substantially decreases the affinity of TC for 48S PICs (>10-fold higher KD) (Fig. 4F). This defect could allow TC to dissociate from 48S PICs while scanning from the 5′-end during primary initiation, yielding a fraction of PICs that reach the uORF AUG without TC and thus continue scanning downstream. Subsequent reassociation of TC with a proportion of these scanning 40S subunits before they reach the GCN4 AUG would allow them to translate GCN4 instead (Fig. 1C, right, mechanism [1]). If this explanation is correct, it should be possible to suppress leaky scanning of solitary uORFs during primary initiation by TC overexpression, increasing the occupancy of TC on scanning PICs. Indeed, as shown by results presented in Supplemental Figure S4, we found that hc TC does partially suppress the leaky-scanning phenotype of the A928T mutant.

Considering that leaky scanning of solitary uORFs in the A928T mutant was not completely eliminated by hc TC (Supplemental Fig. S4), it is possible that the A928 substitutions also provoke incorrect binding of tRNAiMet and failure to achieve precise codon–anticodon pairing in the P-site, defects that cannot be corrected by increased TC levels. In this view, the PIC arrives at the AUG loaded with TC but, with an appreciable frequency, fails to arrest scanning or complete GTP hydrolysis by TC and continues scanning downstream to the next AUG (Fig. 1C, right, mechanism [2]). This alternative mechanism might also account for our finding that the Gcd− phenotypes of the A927C, T1390C, and C934T mutations in h28 and the three mutations at residue C1400 were not suppressed by hc IMT or hc TC, even though they confer increased leaky scanning of the solitary uORFs. Consistent with this idea, C1400 interacts with the wobble base of the P-tRNA anticodon in bacterial 70S complexes (Korostelev et al. 2006; Selmer et al. 2006) and could be critical for precise codon–anticodon pairing.

The leaky scanning of uORF1 conferred by the A928 substitutions can probably account for the unique ability of these mutations to derepress the GCN4-lacZ fusion containing all four uORFs by a smaller amount than they derepress single-uORF constructs. This follows from the fact that translation of uORF1 is essential for efficient reinitiation at GCN4. Thus, any PICs that leaky-scan past uORF1 and initiate first at uORFs 2, 3, or 4 cannot reinitiate at GCN4, owing to the inability of post-termination 40S subunits to resume scanning after terminating at the latter uORFs (Hinnebusch 2005a). Hence, while leaky scanning in the A928 mutants should derepress GCN4 translation by increasing the bypass of uORFs 2–4, it will have an offsetting effect and reduce GCN4 expression when the leaky scanning occurs at uORF1. Indeed, the derepression of wild-type GCN4-lacZ with all four uORFs by the A928 mutations is moderate (approximately fourfold) compared with that of eIF2B mutations (≈20-fold), most likely because the latter mutations don’t allow leaky scanning of uORF1 during primary initiation events.

By analyzing compensatory mutations that restore the 928:1389 base pair in the A928T and A928C mutants, we found that strong Gcd− and leaky-scanning phenotypes occurred only when the base pair was disrupted in a manner that left unpaired pyrimidines at this position in h28 (Fig. 3A,B). Hence, the identity of the base pair itself is not critical, and the functional impairment results from the presence of particular unpaired bases. We performed a similar analysis of the adjacent base pair (927:1390) and obtained quite similar results, which are presented in Supplemental Figure S5A–D. These last data show that the identity of the 927:1390 base pair is not critical and only certain combinations of unpaired bases at this position produce recessive lethality and dominant Gcd− phenotypes. It is possible that particular unpaired bases at positions 927/1390 and 928/1389 lead to novel interactions with surrounding rRNA residues that disrupt the orientation of h28 or the function of bulge nucleotide G926 in a way that impairs TC recruitment and AUG recognition. Another intriguing mechanism is suggested by our realization that all of the strong Gcd− substitutions in these two base pairs allow for alternative base-pairing that restores the wild-type number of base pairs but alters the position and identity of the bulge nucleotide in h28. These isomerizations entail base-pairing of bulge G926 with the pyrimidine at position 1390 and, for mutations A927C and T1390C, converting C927 or A927, respectively, to the bulge nucleotide, and, for mutations A928T and A928C, making U928 or C928 the bulge nucleotide. The compensatory mutations would suppress this deleterious change in h28 structure by restoring the wild-type number of base pairs without having to shift the bulge nucleotide.

In bacterial 70S ribosomes, h28 is very close to the P-site, and G926 directly contacts the +1 phosphate of the P-site codon (Korostelev et al. 2006; Selmer et al. 2006). Hence, the Gcd− mutations affecting the two adjacent base pairs might alter the orientation of G926 and disturb codon–anticodon pairing in the P-site. This could reduce the affinity of tRNAiMet for the 40S subunit in the case of A928 mutations (which are suppressed by hc IMT), or block a conformational change required for AUG recognition in the case of A927 and C1390 mutations (which are not suppressed by hc IMT). Supporting this idea, substituting G926 with C or U, which should eliminate both H-bonds with the P-site codon (Korostelev et al. 2006), is lethal, and the U substitution provokes a dominant Gcd− phenotype and elevated leaky scanning during primary initiation. The G926A substitution should retain one of the two H-bonds and, consistently, is nonlethal and confers less severe Gcd− and leaky-scanning phenotypes compared with G926U. Also supporting the notion that A928U perturbs a P-codon contact in eukaryotes is our finding that it confers significantly greater defects in the rate and stability of TC binding to (48S) PICs containing mRNA versus (43S) PICs lacking mRNA.

On the other hand, two observations suggest that A928 substitutions do not impair initiation simply by perturbing contact of G926 with AUG. First, A928U moderately reduces the affinity for TC and rate of TC loading in PICs lacking mRNA and, hence, must impair tRNAiMet binding at least partly by a mechanism independent of AUG. Interestingly, as shown in Supplemental Figure S6, A–C, we found that G926A mutant 40S subunits also exhibit modest defects in TC loading in the absence of mRNA, comparable with those described above for A928U subunits under the same circumstances (Fig. 4). Perhaps G926 forms H-bonds with the phosphate backbone of an rRNA residue near the P-site to stabilize tRNAiMet binding in the 43S PIC prior to association with mRNA. In fact, it has been suggested that interaction of G926 with the 3′ tail of 16S rRNA could be instrumental in initiator recruitment to bacterial 30S subunits in the absence of mRNA (Yusupova et al. 2001).

A second difficulty with the idea that A928 substitutions merely perturb G926 function is our finding that the Gcd− phenotypes of both G926 mutations are suppressed by hc IMT but not by hc TC and, thus, seem to differ mechanistically from the A928 mutations. A possible explanation for this last distinction is that G926 mutations might reduce tRNAiMet binding to the P-site of 48S PICs only after GTP hydrolysis and subsequent release of eIF2-GDP. Consequently, if tRNAiMet dissociates prior to 60S subunit joining at uORF4, this would allow scanning to resume and permit reinitiation downstream at GCN4. Increasing the concentration of tRNAiMet could then prevent its dissociation prior to subunit joining by mass action and thereby suppress leaky scanning. Perhaps overexpressing eIF2 together with tRNAiMet does not reduce leaky scanning because a fraction of the excess eIF2 titrates tRNAiMet from the defective P-site, increasing the rate of tRNAiMet dissociation by mass action. This would exacerbate rather than suppress leaky scanning. A related phenomenon was described previously wherein the initiation defect associated with deletion of the subunit joining factor eIF5B was suppressed by hc IMT but exacerbated by overexpressing eIF2 (Choi et al. 1998). We observed only a small defect in TC loading on G926A mutant subunits in PICs containing mRNA (Supplemental Fig. S6C). While this could merely reflect the weak Gcd− phenotype of G926A, it would also fit with a Gcd−/leaky scanning mechanism involving tRNAiMet dissociation only after GTP hydrolysis and release of eIF2-GDP.

For the reasons just described, therefore, we consider it likely that the A928 mutations in h28 perturb another contact between the rRNA and tRNAiMet or mRNA that cannot be predicted from bacterial 70S crystal structures. Indeed, recent UV cross-linking analysis of the position of mRNA in reconstituted mammalian 48S PICs indicates that h28 is located at a different location, closer to the A-site, than observed in bacterial 70S complexes, and that G926 would be too distant to interact with AUG in the P-site (Pisarev et al. 2008). We should also consider the possibility that A928 mutations affect the rotation of the head, centered on h28, which seems to be required for unobstructed tRNAiMet binding to the P-site of bacterial 70S ribosomes (Korostelev et al. 2006). Rotation of the head was also observed in cryo-EM reconstructions of eukaryotic 40S subunits on binding to internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs) of viral mRNAs (Spahn et al. 2001b, 2004b) or to the multifactor complex of yeast, comprised of eIF3, eIF1, eIF5 and TC, and eIF1A (Gilbert et al. 2007). It is intriguing that the C934T Gcd− mutation we obtained alters the unpaired residue at the base of h28 that serves as the pivot point for head rotation in 70S complexes (Schuwirth et al. 2005). C934 intercalates between C1344 and C1345 via long-range tertiary interactions that stabilize the neck. C934 also H bonds to A937 and A938 (Fig. 5A, right). The U934 substitution would eliminate the H bonds to A937 and A938, altering the position of residue 934 and perturbing the neck conformation (Selmer et al. 2006). Accordingly, the extent of head rotation could be reduced by the C934U substitution in a way that destabilizes tRNAiMet binding to the P-site and elevates leaky scanning.

Finally, we found that mutations of several other 18S rRNA residues corresponding to direct contacts with the P-codon (G1401) or ASL (G1338, A1339) in 70S complexes are lethal, confer dominant Gcd− phenotypes suppressible by hc IMT and hc TC, and increase leaky scanning of solitary uORFs in yeast cells. These findings indicate that at least some of the contacts with P-site ligands in the structural models of bacterial 70S elongation complexes are physiologically relevant to eukaryotic ICs in vivo. The fact that mutating these 18S rRNA residues confers Gcd− phenotypes and increased leaky scanning provides the first in vivo evidence that inspection of successive triplets by tRNAiMet in the scanning PIC occurs in the 40S P-site. The G1338 and A1339 mutations are of particular interest because, through minor groove interactions with the ASL of tRNAiMet, they likely facilitate selection of initiator versus elongator tRNAs during initiation in E. coli (Lancaster and Noller 2005). Our findings that all three substitutions at A1339 are lethal and that pyrimidine replacements are lethal but A is functional at 1338, are concordant with the importance of A-minor interactions of G1338/A1339 with the ASL of tRNAiMet in eukaryotes. Also consistent is our previous finding that the relevant G-C base pairs in the ASL of yeast tRNAiMet increase affinity of tRNAiMet for the 48S PIC (Kapp et al. 2006). It will be interesting to determine whether substitutions at G1338 or A1339 affect the accuracy, as well as the efficiency, of AUG recognition in yeast.

Materials and methods

The plasmids and yeast strains used in this study are listed in Supplemental Tables S1 and S3, along with details of their construction. Random PCR mutagenesis was conducted using the GeneMorph PCR Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene), and site-directed mutagenesis was conducted using the QuickChange XL kit (Stratagene) and the primers in Supplemental Table S2. Analysis of SM sensitivity and assays of GCN4-lacZ expression were conducted as described previously (Fekete et al. 2005). Purification of ribosomes (Algire et al. 2002), primer extensions on extracted 18S rRNA (Sigmund et al. 1988), and measurements of TC and eIF1 binding to 40S subunits in the reconstituted yeast system (Maag and Lorsch 2003) were carried out as reported previously, with the minor modifications described in the Supplemental Material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Masayasu Nomura and Jon Dinman for strains, plasmids, and advice Venki Ramakrishnan for helpful discussion regarding C934, Christian Spahn for valuable advice, and Tom Dever for critical comments. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIH and by NIH grant GM62128 to J.R.L.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1696608.

References

- Abastado J.P., Miller P.F., Jackson B.M., Hinnebusch A.G. Suppression of ribosomal reinitiation at upstream open reading frames in amino acid-starved cells forms the basis for GCN4 translational control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:486–496. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.1.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdi N.M., Fredrick K. Contribution of 16S rRNA nucleotides forming the 30S subunit A and P sites to translation in Escherichia coli. RNA. 2005;11:1624–1632. doi: 10.1261/rna.2118105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algire M.A., Lorsch J.R. Where to begin? The mechanism of translation initiation codon selection in eukaryotes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algire M.A., Maag D., Savio P., Acker M.G., Tarun S.Z., Sachs A.B., Asano K., Nielsen K.H., Olsen D.S., Phan L., et al. Development and characterization of a reconstituted yeast translation initiation system. RNA. 2002;8:382–397. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202029527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen G.S., Zavialov A., Gursky R., Ehrenberg M., Frank J. The cryo-EM structure of a translation initiation complex from Escherichia coli. Cell. 2005;121:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoun A., Pavlov M.Y., Lovmar M., Ehrenberg M. How initiation factors maximize the accuracy of tRNA selection in initiation of bacterial protein synthesis. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk V., Zhang W., Pai R.D., Cate J.H. Structural basis for mRNA and tRNA positioning on the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:15830–15834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607541103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung Y.N., Maag D., Mitchell S.F., Fekete C.A., Algire M.A., Takacs J.E., Shirokikh N., Pestova T., Lorsch J.R., Hinnebusch A.G. Dissociation of eIF1 from the 40S ribosomal subunit is a key step in start codon selection in vivo. Genes & Dev. 2007;21:1217–1230. doi: 10.1101/gad.1528307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.K., Lee J.H., Zoll W.L., Merrick W.C., Dever T.E. Promotion of Met-tRNAiMet binding to ribosomes by yIF2, a bacterial IF2 homolog in yeast. Science. 1998;280:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete C.A., Applefield D.J., Blakely S.A., Shirokikh N., Pestova T., Lorsch J.R., Hinnebusch A.G. The eIF1A C-terminal domain promotes initiation complex assembly, scanning and AUG selection in vivo. EMBO J. 2005;24:3588–3601. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete C.A., Mitchell S.F., Cherkasova V.A., Applefield D., Algire M.A., Maag D., Saini A., Lorsch J.R., Hinnebusch A.G. N- and C-terminal residues of eIF1A have opposing effects on the fidelity of start codon selection. EMBO J. 2007;26:1602–1614. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R.J., Gordiyenko Y., von der Haar T., Sonnen A.F., Hofmann G., Nardelli M., Stuart D.I., McCarthy J.E. Reconfiguration of yeast 40S ribosomal subunit domains by the translation initiation multifactor complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:5788–5793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606880104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch A.G. Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005a;59:407–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.031805.133833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch A.G. Translational regulation of gcn4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005b;59:407–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.031805.133833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch A.G., Dever T.E., Asano K. Mechanism of translation initiation in the yeastSaccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Mathews N.S., Hershey John W.B., editors. Translational control in biology and medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2007. pp. 225–268. [Google Scholar]

- Kapp L.D., Kolitz S.E., Lorsch J.R. Yeast initiator tRNA identity elements cooperate to influence multiple steps of translation initiation. RNA. 2006;12:751–764. doi: 10.1261/rna.2263906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korostelev A., Trakhanov S., Laurberg M., Noller H.F. Crystal structure of a 70S ribosome–tRNA complex reveals functional interactions and rearrangements. Cell. 2006;126:1065–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster L., Noller H.F. Involvement of 16S rRNA nucleotides G1338 and A1339 in discrimination of initiator tRNA. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomakin I.B., Kolupaeva V.G., Marintchev A., Wagner G., Pestova T.V. Position of eukaryotic initiation factor eIF1 on the 40S ribosomal subunit determined by directed hydroxyl radical probing. Genes & Dev. 2003;17:2786–2797. doi: 10.1101/gad.1141803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag D., Lorsch J.R. Communication between eukaryotic translation initiation factors 1 and 1A on the yeast small ribosomal subunit. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;330:917–924. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00665-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marintchev A., Wagner G. Translation initiation: Structures, mechanisms and evolution. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2004;37:197–284. doi: 10.1017/S0033583505004026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller P.P., Harashima S., Hinnebusch A.G. A segment of GCN4 mRNA containing the upstream AUG codons confers translational control upon a heterologous yeast transcript. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987;84:2863–2867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore L.A., Schmeing T.M., Maag D., Applefield D.J., Acker M.G., Algire M.A., Lorsch J.R., Ramakrishnan V. The eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF1 and eIF1A induce an open conformation of the 40S ribosome. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova T.V., Lorsch J.R., Hellen C.U.T. The mechanism of translation initiation in eukaryotes. In: Mathews N.S., Hershey John W.B., editors. Translational control in biology and medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2007. pp. 87–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pisarev A.V., Kolupaeva V.G., Yusupov M.M., Hellen C.U., Pestova T.V.2008Ribosomal position and contacts of mRNA in eukaryotic translation initiation complexes EMBO J. 27 :1609–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin D., Abdi N.M., Fredrick K. Characterization of 16S rRNA mutations that decrease the fidelity of translation initiation. RNA. 2007;13:2348–2355. doi: 10.1261/rna.715307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakauskaite R., Dinman J.D. An arc of unpaired “hinge bases” facilitates information exchange among functional centers of the ribosome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:8992–9002. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01311-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuwirth B.S., Borovinskaya M.A., Hau C.W., Zhang W., Vila-Sanjurjo A., Holton J.M., Cate J.H. Structures of the bacterial ribosome at 3.5 Å resolution. Science. 2005;310:827–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1117230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmer M., Dunham C.M., Murphy F.V.T., Weixlbaumer A., Petry S., Kelley A.C., Weir J.R., Ramakrishnan V. Structure of the 70S ribosome complexed with mRNA and tRNA. Science. 2006;313:1935–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.1131127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmund C.D., Ettayebi M., Borden A., Morgan E.A. Antibiotic resistance mutations in ribosomal RNA genes of Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1988;164:673–690. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(88)64077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spahn C.M., Beckmann R., Eswar N., Penczek P.A., Sali A., Blobel G., Frank J. Structure of the 80S ribosome from Saccharomyces cerevisiae—tRNA–ribosome and subunit–subunit interactions. Cell. 2001a;107:373–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00539-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spahn C.M., Kieft J.S., Grassucci R.A., Penczek P.A., Zhou K., Doudna J.A., Frank J. Hepatitis C virus IRES RNA-induced changes in the conformation of the 40S ribosomal subunit. Science. 2001b;291:1959–1962. doi: 10.1126/science.1058409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spahn C.M., Gomez-Lorenzo M.G., Grassucci R.A., Jorgensen R., Andersen G.R., Beckmann R., Penczek P.A., Ballesta J.P., Frank J. Domain movements of elongation factor eEF2 and the eukaryotic 80S ribosome facilitate tRNA translocation. EMBO J. 2004a;23:1008–1019. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spahn C.M., Jan E., Mulder A., Grassucci R.A., Sarnow P., Frank J. Cryo-EM visualization of a viral internal ribosome entry site bound to human ribosomes: The IRES functions as an RNA-based translation factor. Cell. 2004b;118:465–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.J., Frank J., Kinzy T.G. Structure and function of the eukaryotic ribosome and elongation factors. In: Mathews N.S., Hershey John W.B., editors. Translational control in biology and medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2007. pp. 59–85. [Google Scholar]

- Williams N.P., Hinnebusch A.G., Donahue T.F. Mutations in the structural genes for eukaryotic initiation factors 2α and 2β of Saccharomyces cerevisiae disrupt translational control of GCN4 mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1989;86:7515–7519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusupova G.Z., Yusupov M.M., Cate J.H., Noller H.F. The path of messenger RNA through the ribosome. Cell. 2001;106:233–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]