Abstract

Influenza virus infection of the respiratory tract is characterized by a neutrophil infiltrate accompanied by inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production. We and others have reported that Toll-like receptor (TLR) proteins are present on human neutrophils and that granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) treatment enhances IL-8 (CXCL8) secretion in response to stimulation with TLR ligands. We demonstrate that influenza virus can induce IL-8 and other inflammatory cytokines from GM-CSF–primed human neutrophils. Using heat inactivation of influenza virus, we show that viral entry but not replication is required for cytokine induction. Furthermore, endosomal acidification and viral uncoating are necessary. Finally, using single-cell analysis of intracellular cytokine accumulation in neutrophils from knockout mice, we prove that TLR7 is essential for influenza viral recognition and inflammatory cytokine production by murine neutrophils. These studies demonstrate neutrophil activation by influenza virus and highlight the importance of TLR7 and TLR8 in that response.

Introduction

Neutrophils are highly recruited to sites of infection and are a significant source of tissue injury during the innate immune response to viral infection, including that by influenza A virus. Influenza A virus is a negative stranded RNA virus that infects epithelial cells of the upper respiratory tract and bronchi. Infection usually is limited to trachea and bronchi but may extend to bronchioles and alveoli, resulting in an interstitial pneumonia. During respiratory infection, cellular infiltrates develop in the alveoli that consist of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.1 In an animal model of infection with influenza virus, bronchoalveolar lavage samples showed a predominance of neutrophils over monocytes and macrophages.2 Neutrophil activation may contribute to the pathogenesis of severe or fatal viral infection. The marked diminution in neutrophil survival upon incubation with influenza virus in the presence of Streptococcus pneumoniae may contribute to the risk of severe or fatal pneumonia associated with influenza in both its sporadic and pandemic forms.3 Notably, infection of macaque monkeys with the 1918 influenza virus produced a pathological immune response characterized by uncontrolled and aberrant activation of the innate immune system.4,5 However, it was unclear from these studies whether neutrophils were among the virus-responsive instigators or only the final effectors of the immune response and tissue pathology. Recovery from infection depends on the recruitment of proinflammatory leukocytes to the site of infection. Multiple chemokines are induced in lungs from animals infected with influenza A virus, including MIP-1α (CCL3), MIP-1β (CCL4), MIP-3α (CCL20), RANTES (CCL5), MIP-2 (CXCL2), and IP-10 (CXCL10).6 Notably, fatal outcome following human infection with avian influenza A virus (H5N1) is associated with high levels of inflammatory cytokines in the peripheral blood including IP-10, MCP-1 (CCL2), MIG (CXCL9), and IL-8 (CXCL8).7 Thus, understanding the mechanisms of chemokine and cytokine responses to influenza virus is of high priority, as excessive cytokine production may contribute to viral pathogenesis.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a key role in the innate immune recognition of many viral pathogens, including influenza virus.8,9 TLR7 and TLR8 are closely related endosomal receptors that recognize single-stranded RNA (ssRNA).8,10 Cytokine responses to synthetic TLR7/8 agonists require endosomal acidification.11,12 Similarly, the induction of interferon-α (IFN-α) by influenza virus in murine plasmacytoid dendritic cells is dependent on the presence TLR7 and endosomal acidification.8 The potential contribution of TLR7 and TLR8 to inflammatory cytokine production by neutrophils in response to viral pathogens such as influenza virus has not been explored. Human neutrophils express most TLRs, with the exception of TLR3, as measured by quantitative reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).13 Significant levels of TLR7 mRNA have also been detected in plasmacytoid dendritic cells and B cells.14

In prior studies, we demonstrated that human neutrophils functionally respond to TLR ligands.15 In addition, we showed that influenza A virus (H3N2) can induce cytokines in a manner dependent on TLR7 and that influenza viral RNA is a potent inducer of TLR7 in several cell systems.16 Thus, our goal was to determine whether TLR7 and TLR8 contribute to inflammatory cytokine responses to influenza virus by neutrophils. Here, we demonstrate that human peripheral blood neutrophils produce inflammatory cytokines following stimulation with influenza virus. We also examine murine peripheral blood neutrophils, directly evaluating the role of TLR7 using TLR7 knockout mice. Our data together highlight the importance of TLR7 and TLR8 in inflammatory cytokine production by neutrophils to influenza virus.

Methods

Human neutrophil preparation

Neutrophils were isolated from normal human peripheral blood by dextran sedimentation and centrifugation through Ficoll-Hypaque as previously described.15 Neutrophils were preincubated with or without recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF, sargramostim; Immunex, Seattle, WA) for 30 minutes at 106 cells/mL in 24-well plates. For some experiments, GM-CSF–treated neutrophils were incubated in the presence of bafilomycin A1 from Streptomyces griseus (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for 30 minutes. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects in Research and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Mice

TLR7−/− mice backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for more than 6 generations were obtained from S. Akira, Osaka University (Osaka, Japan). Age-matched, WT control C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were bred and housed in the animal facility at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Mice were injected subcutaneously with GM-CSF–secreting B16-F10 melanoma cells17 (2.5 × 106 per mouse), a gift from G. Dranoff, Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). Blood was collected by cardiac puncture after 14 days. Experimental protocols involving animals were approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Mouse cell preparation

Peripheral blood leukocytes were prepared from heparinized blood treated with Gentra red blood cell (RBC) lysis solution (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at a ratio of 3:1 by volume for 10 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed twice, then seeded at 2 × 105 cells/well in a 96-well plate in DMEM/10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Hyclone, Logan, UT) with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) to prevent premature apoptosis and GM-CSF (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) for priming immediately prior to stimulation with TLR ligands or virus. Peritoneal exudate cells and murine embryonic fibroblasts were prepared as previously described.18,19

Cytokine measurement

IL-8, MIP-1β, and MIP-1α were measured from cell supernatants using R&D Systems DuoSet enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs; Minneapolis, MN). For intracellular cytokine staining, leukocytes were incubated with both G-CSF and GM-CSF, stimulated with either virus or TLR ligands, and then 10 minutes later were treated with GolgiPlug, a protein transport inhibitor containing brefeldin A (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). After 20 hours, human neutrophils were stained with anti-human CD16 Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated antibody (BD Biosciences), anti–human CD3 FITC-conjugated antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), anti–human CD19 PE-conjugated antibody, and anti–human HLA-DR antibody (BD Biosciences). Following treatment with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences), the cells were stained for human IL-8 using phycoerythrin-conjugated mouse anti–human IL-8 monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences). Murine leukocytes were stained using Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated rat anti–mouse 7/4 monoclonal antibody (Serotec, Raleigh, NC) and F4/80-FITC (eBioscience). After treatment with Cytofix/Cytoperm, phycoerythrin-conjugated rat anti–mouse TNF monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences) was used for intracellular staining. For some experiments, cells were stained with anti–influenza A NP antibody-FITC (Virostat, Portland, ME).

Flow cytometry

The cells were acquired using BD FacsDiva software on a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Debris and dead cells were excluded by gating. For murine cells, those positive for 7/4 were gated, and the percentage positive for TNF was calculated using FlowJo v8.1 (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

HEK cells

HEK/TLR8 cells were purchased from InvivoGen and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and blasticidin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA). HEK/TLR7 cells were a gift from the Eisai Research Institute (Andover, MA). Cells were grown to about 80% confluence in a 96-well plate and in some cases transfected with 80 ng NF-κB luciferase reporter gene and 20 ng of control Renilla luciferase reporter gene. Sixteen hours later, cells were treated with bafilomycin A1 for 30 minutes, and then stimulated with various agents. Luminescence was read 8 hours later using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) and a fluorometer. In other experiments, cells were grown in a 96-well plate and stimulated with various agents, and IL-8 in supernatants was measured 14 hours later by ELISA.

Cell stimulants

LPS from Escherichia coli serotype O11:B4 (Sigma-Aldrich) was phenol re-extracted to remove contaminating lipopeptides.20 Pam2CSK4 was purchased from EMC Microcollections (Tuebingen, Germany). Poly (I:C) was purchased from Axxora (San Diego, CA). R-848 was a gift from D. Golenbock (University of Massachusetts). CpG ODN 2006 was purchased from Coley Pharmaceutical (Kanata, ON). IL-1β was purchased from R&D Systems.

Virus

Influenza A Hong Kong/8/68 (H3N2) and influenza A X31 Aichi/68 (H3N2) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). These strains gave similar results and were selected based on availability of high-titer stocks. Viral RNA was prepared using the QIAAmp Viral Nucleic Acid extraction kit (Qiagen), followed by DNase treatment, phenol/chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 in serum-free OptiMem per the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Results

Human neutrophil cytokine responses to influenza virus and TLR ligands

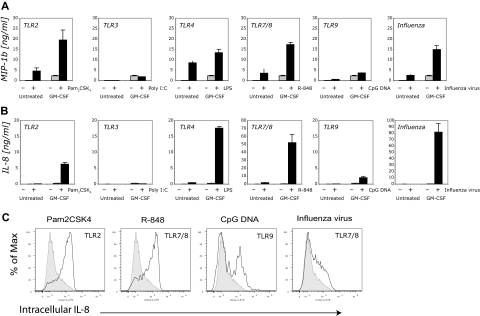

We found that specific cytokines are induced in GM-CSF–primed neutrophils in response to influenza virus. Using purified human neutrophils and ELISA analysis of culture supernatants, we noted that several inflammatory cytokines are induced within 24 hours following challenge with influenza virus, including MIP-1β (Figure 1A) and IL-8 (Figure 1B). Similarly, TLR ligands induced cytokine secretion under these conditions. Ligands included activators of cell surface TLRs, including the TLR2/6 agonist Pam2CSK4 and the TLR4 agonist LPS. Furthermore, activators of intracellular TLRs, namely the TLR9 agonist CpG 2006, and the TLR7/8 agonist R-848, led to production of inflammatory cytokines. The TLR3 ligand poly (I:C) did not induce cytokines above medium control in GM-CSF–primed neutrophils, consistent with previously published data.13 IL-1β and MIP-1α were present in significant amounts, but human TNF, IP-10, and IFN-α were all undetected by ELISA from these same supernatants (data not shown).

Figure 1.

GM-CSF enhances neutrophil cytokine responses to influenza virus and specific TLR ligands. (A) MIP-1β was measured from supernatants of human neutrophils (106 cells) incubated with or without GM-CSF (100 U/mL) for 30 minutes, then stimulated with Pam2CSK4 (10 ng/mL), poly (I:C) (50 μg/mL), LPS (10 ng/mL), R-848 (3 μM), CpG (6 μg/mL), or influenza virus (X31, 100 000 HA). Error bars here and elsewhere represent standard deviation (SD) of triplicates. Data shown are from 1 representative experiment; similar results were obtained in 6 independent experiments using different donors. (B) IL-8 was measured in the same cell supernatants as in panel A. (C) Intracellular cytokine staining for IL-8 was performed on human neutrophils treated with G-CSF (100 U/mL) and GM-CSF (100 U/mL). Cells were stimulated with Pam2CSK4 (100 ng/mL), CpG (10 μg/mL), R-848 (10 μM), or influenza virus (X31, 100 000 HA), treated with brefeldin A, and stained with antibodies to CD16, CD3, CD19, and HLA-DR. Cells were permeabilized then stained with antibody to IL-8 (solid line) or isotype control (gray histogram). Gates were set for CD16+, CD3−, CD19−, and HLA-DR− cells.

To confirm that neutrophils, rather than other peripheral blood cells, were the cells responsible for the production of cytokines in response to stimuli including influenza virus, we performed single-cell analysis of neutrophils (Figure 1C). The cells were greater than 95% pure as determined by the cell profile: CD16+, HLA-DR−, CD19−, and CD3−. Neutrophil cultures were stimulated with influenza virus in the presence of brefeldin A to allow for intracellular accumulation of cytokines. The cells were subsequently fixed, permeabilized, and stained for IL-8. The majority of the neutrophil population shifted to the right, indicating that intracellular IL-8 accumulated following stimulation with virus compared with unstimulated control cells (Figure 1C). Similarly, both Pam2CSK4 and R-848 led to the production of IL-8 in the majority of neutrophils. Interestingly, CpG DNA activated a subset of neutrophils (∼ 50%) to express IL-8, suggesting heterogeneity within the neutrophil population.

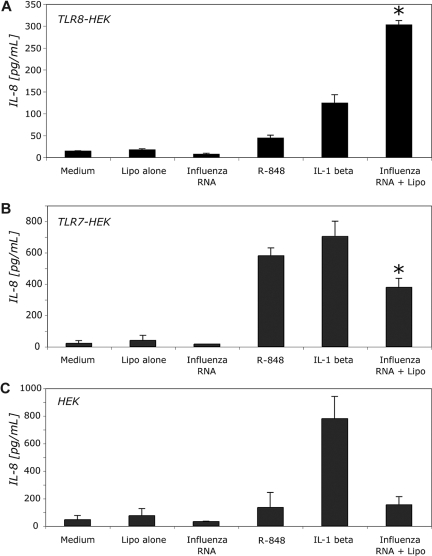

Influenza viral RNA activates both human TLR7 and TLR8

We next determined whether influenza viral RNA could interact with human TLR8 to induce inflammatory cytokine production. Using HEK cells stably expressing human TLR8, we found that TLR8 expression was sufficient to allow for IL-8 production in response to influenza viral RNA complexed with lipofectamine (Figure 2A). This was particularly important to establish, given that human neutrophils contain high levels of mRNA for TLR8 and relatively low levels of TLR7 by quantitative RT-PCR.13 A recent study also confirmed the expression of TLR8 in human neutrophils by flow cytometry.21

Figure 2.

Influenza viral RNA is a ligand for both human TLR7 and TLR8. (A) HEK/TLR8 cells (5 × 104 cells) were stimulated with R-848 (3 μM), influenza virus RNA (X31, 0.2 nM) with or without lipofectamine transfection, or IL-1β (100 ng/mL). Supernatants were collected at 14 hours and IL-8 was measured by ELISA. (B) HEK/TLR7 cells were stimulated as in panel A. (C) HEK cells were also stimulated under these same conditions. Data shown are from one experiment. Two other experiments yielded similar results. Error bars represent the SD of triplicate samples. *P < .01 for influenza RNA compared with medium control by the 2-tailed paired t test.

HEK cells expressing a human TLR7 plasmid also produce IL-8 in response to influenza viral RNA (Figure 2B), whereas HEK cells alone do not respond to influenza viral RNA (Figure 2C).

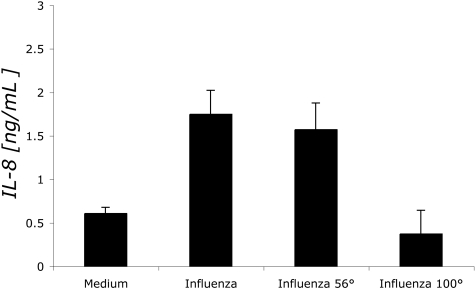

Viral entry, but not replication, is required for the cytokine response of neutrophils to influenza virus

To prove that influenza virus can infect human neutrophils, we demonstrated that influenza nucleoprotein (NP) is expressed in neutrophils by intracellular staining and flow cytometric analysis (data not shown). This is consistent with other investigators' observations that influenza virus can bind to human neutrophils, leading to the expression of newly synthesized viral antigens including NP, hemagglutinin (HA), and nonstructural proteins.22,23 We subsequently sought to determine whether viral entry is a required step for the induction of cytokines by influenza virus in human neutrophils using heat-inactivated influenza virus. Attachment and fusion of influenza virus occurs when the virion's HA binds to sialic acid of the target host cell. Treatment of influenza virus at 56°C inactivates the viral polymerase and prevents viral replication. On the other hand, treatment at 100°C denatures HA, thereby abrogating virus binding.24 We compared IL-8 production between human neutrophils challenged with active influenza virus, virus treated at 56°C, and virus treated at 100°C (Figure 3). We found that virus treated at 56°C behaved similarly to active virus in that both virus preparations induced cytokines. However, treatment of virus at 100°C abrogated its ability to induce cytokines from neutrophils. These results suggest that influenza virus entry, but not replication, is required for inflammatory cytokine production by human neutrophils.

Figure 3.

56°C-inactivated influenza virus induces cytokines in human neutrophils. Human neutrophils (106 cells) were incubated with GM-CSF (100 U/mL) for 30 minutes, then stimulated with influenza virus (Hong Kong, 500 000 HA), influenza virus treated at 56°C for 30 minutes, or influenza virus treated at 100°C for 30 minutes. Supernatants were collected at 24 hours and IL-8 was measured by ELISA. Error bars represent the SD of triplicate samples. Data shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

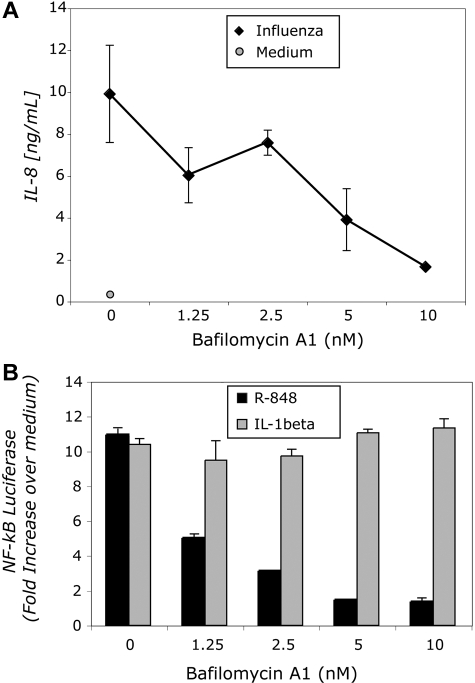

Neutrophil cytokine responses to influenza require endosomal acidification

We next determined whether influenza-mediated cytokine induction in neutrophils was sensitive to bafilomycin A1 (Baf-A1), a specific inhibitor of the vacuolar-type proton pump. Following cell entry, the virion is endocytosed into an acidified compartment in which the low pH triggers a conformation change in HA, allowing viral fusion and the release of the nucleocapsid into the cytosol.25 Release of the virion from the cell requires neuraminidase, which cleaves sialic acid. Baf-A1 has been shown to inhibit the growth of influenza virus in cell culture.26,27 Thus, we treated neutrophils with several doses of Baf-A1 prior to stimulation. At high doses of Baf-A1, cytokine production by neutrophils in response to influenza virus was significantly reduced (Figure 4A). Cytokine production in response to LPS was unaffected by Baf-A1 at these same concentrations, confirming that TLR4-mediated signaling is not dependent on endosomal acidification and that the Baf-A1 inhibition of influenza-mediated neutrophil activation was specific (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Bafilomycin A1 inhibits both R-848– and influenza-mediated signaling. (A) Human neutrophils (106 cells) were incubated with GM-CSF (100 U/mL) for 30 minutes, with the indicated concentrations of bafilomycin A1 for 30 minutes, and then stimulated with influenza virus (X31, 100 000 HA). Supernatants were collected at 24 hours and cytokines measured by ELISA. (B) HEK/TLR8 cells (5 × 104 cells) were transfected with reporter plasmids, incubated with the indicated concentration of bafilomycin A1 for 30 minutes, and then stimulated with either R-848 (10 μM) or IL-1β (100 ng/mL). Cells were lysed 8 hours later. The readout is the fold increase of firefly luciferase/Renilla luciferase ratio over the unstimulated control. Error bars represent SD of triplicate samples.

Since human neutrophils express high levels of TLR8, we also confirmed that recognition of R-848 by human TLR8 was sensitive to Baf-A1. Induction of NF-κB by R-848 in HEK293 cells stably expressing human TLR8 was reduced in the presence of increasing amounts of Baf-A1, whereas induction by IL-1β, a TLR-independent activator, was completely unaffected (Figure 4B).

Murine neutrophil cytokine responses to influenza virus require TLR7

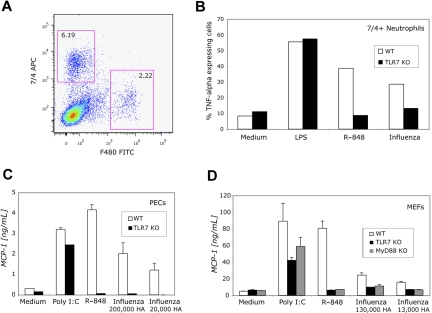

We defined a subset of peripheral blood neutrophils in C57BL/6 mice that had a robust cytokine response in response to stimulation with TLR ligands. These cells were positive for the surface marker 7/4 and negative for F480. To increase total numbers of peripheral blood neutrophils per mouse, we injected mice with a B16 melanoma cell line engineered to produce high levels of soluble murine GM-CSF17 and harvested whole blood 14 days later. Leukocytes were cultured in the presence of G-CSF to prevent premature apoptosis and GM-CSF for priming and were stimulated with either TLR ligands or influenza virus. We analyzed the peripheral blood neutrophils at the single-cell level by assessing intracellular cytokine accumulation in cells gated on 7/4+/F480− neutrophils (Figure 5A). This population of cells includes GR1+ cells, which are myeloid. The 7/4+ population specifically represents mature neutrophils and excludes natural killer (NK) cells (data not shown), and we were able to measure intracellular TNF in these cells. A high percentage of the defined murine peripheral blood neutrophils produced TNF in response to R-848 and influenza virus (Figure 5B). By examining neutrophils from TLR7 knockout mice, we determined that the cytokine response to influenza virus was dependent on TLR7 (Figure 5B). We also confirmed that inflammatory cytokine responses to influenza virus were dependent on TLR7 in murine peritoneal exudate cells (Figure 5C) and embryonic fibroblasts (Figure 5D). These cells express multiple TLRs and are responsive to many other TLR ligands including LPS. Thus, these data also demonstrate that the influenza virus preparation was free of contamination with other TLR agonists, such as endotoxin.

Figure 5.

Murine cells make inflammatory cytokines in response to influenza virus in a TLR7-dependent manner. (A) Peripheral blood leukocytes (106 cells) from either wild-type or TLR7 knockout mice were treated with G-CSF (100 U/mL) and GM-CSF (100 U/mL) and then were stained with antibodies specific for 7/4 and F480. (B) Cells were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL), R-848 (10 μM), or influenza virus (Hong Kong, 500 000 HA), permeabilized, and stained for TNF. Results shown are for 7/4+/F480− cells. (C) Peritoneal exudates cells (106 cells) were stimulated with poly (I:C) (50 μg/mL), R-848 (3 μM), or the indicated amount of influenza virus (Hong Kong). Supernatants were collected at 24 hours and cytokines measured by ELISA. P ≤ .01 comparing R-848 or influenza in WT versus TLR7 KO or MyD88 KO by the 2-tailed paired t test. Data are means (± SD) of a representative experiment performed in single wells. Two other experiments yielded similar results. (D) Murine embryonic fibroblasts (5 × 104 cells) were stimulated with poly (I:C) (50 μg/mL), R-848 (10 μM), or the indicated amount of influenza virus (Hong Kong), and supernatants were collected at 24 hours and cytokines measured by ELISA. P ≤ .01 comparing R-848 or influenza in WT versus TLR7 KO or MyD88 KO by the 2-tailed paired t test. Data are means (± SD) of a representative experiment performed in single wells. Two other experiments yielded similar results.

Discussion

Neutrophils have been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of severe or fatal infection by a number of viral pathogens, including not only current human and avian influenza strains, but also the 1918 pandemic influenza strain. The current studies provide insight into a pathobiologic mechanism that is relevant to pressing problems in world health. We present a series of unique data on primary neutrophil responses to influenza virus measured as inflammatory cytokine production. We have found that influenza virus entry is necessary for inflammatory cytokine production by human neutrophils. As for the TLR7/8 agonist R-848, cytokine production in neutrophils following influenza virus challenge requires endosomal acidification. Furthermore, inflammatory cytokine production in response to influenza depends largely on TLR7 in murine peripheral blood neutrophils.

Several lines of evidence suggest that interactions of influenza viral RNA with TLR7 and TLR8 are key elements for inflammatory cytokine production by neutrophils. First, robust cytokine production by neutrophils in response to both influenza and the imidazoquinoline R-848 is enhanced after GM-CSF priming. GM-CSF is produced by virtually all inflammatory, stromal, and parenchymal cells in the airways during infection. Second, viral entry, viral uncoating, and endosomal acidification appear to be required for cytokine induction. Given that influenza RNA is a TLR7/8 ligand and that TLR7/8 is localized in the endosome, these data strongly suggest that TLR7/8 are components in the recognition of influenza. We did not use RNA interference to knock down TLR7/8 in primary human neutrophils since primary neutrophils have a relatively short life span and are difficult to transfect, although successful transfection has been reported.28,29 Nevertheless, we were able to demonstrate that TLR7 plays an essential role in inflammatory cytokine activation in murine neutrophils in response to influenza and the R-848 using TLR7 knockout mice. Murine TLR7−/− neutrophils had poor responses to both R-848 and influenza virus in comparison with wild-type cells. Whether TLR8 is functional in mice remains controversial,30 but TLR8 knockout mice are not currently available. We found that TLR7 significantly contributes to the cytokine response to R-848 and influenza in 3 murine cell populations that we studied—peripheral blood neutrophils, peritoneal exudates cells, and murine embryonic fibroblasts. Murine TLR7 and TLR8 are closely related, but TLR7 knockout mice are unresponsive to imidazoquinolines or viral ssRNA. Since functional differences between mouse TLR7 and TLR8 have not been described, it remains possible that TLR8 contributes to the cytokine response to influenza virus in mice in vivo.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of single-cell intracellular cytokine staining of neutrophils from the peripheral blood of mice. This approach provides a particularly valuable tool given limited numbers of cells that can be obtained from mice and restricted numbers of knockout animals. In theory, cytokine production from multiple populations of cells could be characterized from a single drop of blood.

Previous studies of innate immunity, TLR7, and influenza virus have focused largely on the activation of type I interferons in plasmacytoid dendritic cells.8,9,31 Whereas type I interferon activation via TLR7 may be an essential host antiviral response, concurrent activation of TLR7-mediated inflammatory pathways could be potentially detrimental to the host. In extreme cases of influenza virus infection, an overabundance of inflammatory cytokines can be measured in blood and a pronounced neutrophilic infiltrate seen in the lungs.2,7 We anticipate that the importance of activation of the inflammatory pathway through TLR7 and TLR8 by influenza virus will be further elucidated from murine in vivo pulmonary infections. Neutrophilic infiltration, cytokine and chemokine production, and viral clearance may all be greatly influenced by the presence or absence of TLR7/8.

Finally, recent studies have demonstrated the importance of the RNA helicase retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I) in the activation of type I interferon production in other cell types and the in vivo response to influenza virus.32,33 RIG-I and its adaptor molecule, interferon-β promoter stimulator-1 (IPS-1), could potentially contribute to the inflammatory cytokine response in neutrophils. Characterization of the expression of RIG-I and IPS-1 in human and murine neutrophils will be useful, as will the study of inflammatory cytokine production from innate immune cells from IPS-1–deficient mice or RIG-I–deficient mice following challenge with influenza virus. Future studies will delineate how the balance of inflammatory cytokine production versus type I interferon production in the face of influenza viral infection is mediated in critical cells of the innate immune response, including neutrophils.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD): AI053542 to J.P.W.; AI057784, AI049309, and AI064349 to R.W.F.; DK54369 to P.E.N.; and AI051405 to E.A.K.-J.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.P.W., G.N.B., C.P., and A.C. performed experiments; J.P.W. analyzed results and wrote the paper; and R.W.F., P.E.N., and E.A.K.-J. planned and supervised the experiments and interpreted the data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jennifer Wang, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA 01605; e-mail: jennifer.wang@umassmed.edu.

References

- 1.Bender BS, Small PA., Jr Influenza: pathogenesis and host defense. Semin Respir Infect. 1992;7:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Van Amerongen G, Osterhaus AD. Pathology of human influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Vet Pathol. 2003;40:304–310. doi: 10.1354/vp.40-3-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engelich G, White M, Hartshorn KL. Neutrophil survival is markedly reduced by incubation with influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae: role of respiratory burst. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:50–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, et al. Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2007;445:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nature05495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hampton T. Virulence of 1918 influenza virus linked to inflammatory innate immune response. JAMA. 2007;297:580. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.6.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wareing MD, Lyon AB, Lu B, Gerard C, Sarawar SR. Chemokine expression during the development and resolution of a pulmonary leukocyte response to influenza A virus infection in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:886–895. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1203644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jong MD, Simmons CP, Thanh TT, et al. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat Med. 2006;12:1203–1207. doi: 10.1038/nm1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5598–5603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heil F, Ahmad-Nejad P, Hemmi H, et al. The Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)-specific stimulus loxoribine uncovers a strong relationship within the TLR7, 8 and 9 subfamily. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2987–2997. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J, Chuang TH, Redecke V, et al. Molecular basis for the immunostimulatory activity of guanine nucleoside analogs: activation of Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6646–6651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631696100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi F, Means TK, Luster AD. Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood. 2003;102:2660–2669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, et al. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1-10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurt-Jones EA, Mandell L, Whitney C, et al. Role of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in neutrophil activation: GM-CSF enhances TLR2 expression and TLR2-mediated interleukin 8 responses in neutrophils. Blood. 2002;100:1860–1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JP, Liu P, Latz E, Golenbock DT, Finberg RW, Libraty DH. Flavivirus activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells delineates key elements of TLR7 signaling beyond endosomal recognition. J Immunol. 2006;177:7114–7121. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mach N, Gillessen S, Wilson SB, Sheehan C, Mihm M, Dranoff G. Differences in dendritic cells stimulated in vivo by tumors engineered to secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor or Flt3-ligand. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3239–3246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurt-Jones EA, Sandor F, Ortiz Y, et al. Use of murine embryonic fibroblasts to define Toll-like receptor activation and specificity. J Endotoxin Res. 2004;10:419–424. doi: 10.1179/096805104225006516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandell L, Moran AP, Cocchiarella A, et al. Intact gram-negative Helicobacter pylori, Helicobacter felis, and Helicobacter hepaticus bacteria activate innate immunity via toll-like receptor 2 but not toll-like receptor 4. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6446–6454. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6446-6454.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, Weis JH, Vogel SN, Weis JJ. Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 2000;165:618–622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hattermann K, Picard S, Borgeat M, Leclerc P, Pouliot M, Borgeat P. The Toll-like receptor 7/8-ligand resiquimod (R-848) primes human neutrophils for leukotriene B4, prostaglandin E2 and platelet-activating factor biosynthesis. FASEB J. 2007;21:1575–1585. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7457com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartshorn KL, White MR, Shepherd V, Reid K, Jensenius JC, Crouch EC. Mechanisms of anti-influenza activity of surfactant proteins A and D: comparison with serum collectins. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L1156–L1166. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.6.L1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassidy LF, Lyles DS, Abramson JS. Synthesis of viral proteins in polymorphonuclear leukocytes infected with influenza A virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1267–1270. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.7.1267-1270.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geiss GK, An MC, Bumgarner RE, Hammersmark E, Cunningham D, Katze MG. Global impact of influenza virus on cellular pathways is mediated by both replication-dependent and -independent events. J Virol. 2001;75:4321–4331. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4321-4331.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skehel JJ, Bayley PM, Brown EB, et al. Changes in the conformation of influenza virus hemagglutinin at the pH optimum of virus-mediated membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:968–972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.4.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochiai H, Sakai S, Hirabayashi T, Shimizu Y, Terasawa K. Inhibitory effect of bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type proton pump, on the growth of influenza A and B viruses in MDCK cells. Antiviral Res. 1995;27:425–430. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00040-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guinea R, Carrasco L. Requirement for vacuolar proton-ATPase activity during entry of influenza virus into cells. J Virol. 1995;69:2306–2312. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2306-2312.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardiner EM, Pestonjamasp KN, Bohl BP, Chamberlain C, Hahn KM, Bokoch GM. Spatial and temporal analysis of Rac activation during live neutrophil chemotaxis. Curr Biol. 2002;12:2029–2034. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JL, Ellis BA, Munafo DB, Brzezinska AA, Catz SD. Gene transfer and expression in human neutrophils: the phox homology domain of p47phox translocates to the plasma membrane but not to the membrane of mature phagosomes. BMC Immunol. 2006;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-7-28. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2172/7/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorden KK, Qiu XX, Binsfeld CC, Vasilakos JP, Alkan SS. Cutting edge: activation of murine TLR8 by a combination of imidazoquinoline immune response modifiers and polyT oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2006;177:6584–6587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barchet W, Krug A, Cella M, et al. Dendritic cells respond to influenza virus through TLR7- and PKR-independent pathways. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:236–242. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koyama S, Ishii KJ, Kumar H, et al. Differential role of TLR- and RLR-signaling in the immune responses to influenza A virus infection and vaccination. J Immunol. 2007;179:4711–4720. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]